An Empirical Study of Emotional Intelligence and Stress in College Students

Business Education & Accreditation, v . 7 (1) pp. 1-11, 2015

12 Pages Posted: 8 Feb 2016

Scott Bryant

Montana State University - Bozeman - College of Business

Timothy I Malone

BNSF Railway Company

Date Written: 2015

A growing body of research indicates that emotional intelligence is an important factor for student success. In this paper, we examine the relationship between emotional intelligence and stress. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found a significant relationship between one dimension of emotional intelligence (use of emotions) and stress. We also found that age and gender impacted emotional intelligence and stress. Findings from this study have implications for students and universities.

Keywords: Emotional Intelligence, Stress, College Students

JEL Classification: M50

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Scott Bryant (Contact Author)

Montana state university - bozeman - college of business ( email ).

446 Reid Hall Bozeman, MT 59715 United States

BNSF Railway Company ( email )

Fort Worth,, TX 76131 United States

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, human cognition in evolution & development ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Social & Personality Psychology eJournal

Clinical & counseling psychology ejournal.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Does emotional intelligence buffer the effects of acute stress a systematic review.

- 1 School of Psychology, College of Business, Psychology and Sport, University of Worcester, Worcester, United Kingdom

- 2 School of Environment, Education and Development, Institute of Education, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

People with higher levels of emotional intelligence (EI: adaptive emotional traits, skills, and abilities) typically achieve more positive life outcomes, such as psychological wellbeing, educational attainment, and job-related success. Although the underpinning mechanisms linking EI with those outcomes are largely unknown, it has been suggested that EI may work as a “stress buffer.” Theoretically, when faced with a stressful situation, emotionally intelligent individuals should show a more adaptive response than those with low EI, such as reduced reactivity (less mood deterioration, less physiological arousal), and faster recovery once the threat has passed. A growing number of studies have begun to investigate that hypothesis in respect to EI measured as both an ability (AEI) and trait (TEI), but results are unclear. To test the “stress-buffering” function of EI, we systematically reviewed experimental studies that explored the relationship between both types of EI and acute stress reactivity or recovery. By searching four databases, we identified 45 eligible studies. Results indicated that EI was only adaptive in certain contexts, and that findings differed according to stressor type, and how EI was measured. In terms of stress reactivity, TEI related to less mood deterioration during sports-based stressors (e.g., competitions), physical discomfort (e.g., dental procedure), and cognitive stressors (e.g., memory tasks), but did not appear as helpful in other contexts (e.g., public speaking). Furthermore, effects of TEI on physiological stress responses, such as heart rate, were inconsistent. Effects of AEI on subjective and objective stress reactivity were often non-significant, with high levels detrimental in some cases. However, data suggest that both higher AEI and TEI relate to faster recovery from acute stress. In conclusion, results provide mixed support for the stress-buffering effect of EI. Limitations and quality of studies are also discussed. Findings could have implications for EI training programmes.

Introduction

The concept of emotional intelligence (EI) has generated a high level of public and scientific interest, and controversy, ever since its inception ( Salovey and Mayer, 1990 ). EI is an umbrella term that captures how we perceive, regulate, use, and understand our own emotions and the emotions of others ( Zeidner et al., 2009 ). Two competing conceptualisations of EI exist: trait EI (TEI) and ability EI (AEI). TEI refers to a collection of emotional perceptions and dispositions assessed through self-report questionnaires ( Petrides et al., 2007 ). In contrast, AEI is concerned with emotion-related cognitive abilities, measured using maximum performance tests in a similar manner to IQ ( Mayer et al., 2008 ). Because both TEI and AEI predict good health, successful relationships, educational attainment, and work-related success, among other positive life outcomes ( Brackett et al., 2011 ; Petrides et al., 2016 ), higher levels are generally regarded as beneficial. However, key questions remain unanswered. We do not fully understand the mechanisms linking EI to those positive outcomes— how and when is EI useful? While cross-sectional studies are useful for indicating potential relationships between EI and outcomes, they do not explain how EI might help us handle everyday challenges. Furthermore, while the incremental validity of EI is promising in some cases ( Andrei et al., 2016 ; Miao et al., 2018 ), there are concerns that EI may not predict other outcomes any better than related constructs, such as personality and cognitive ability ( Schulte et al., 2004 ). Moreover, a growing literature also warns that EI may have an unhelpful “dark side” ( Davis and Nichols, 2018 ). Given the substantial interest in training EI across the lifespan (e.g., Nelis et al., 2011 ; Ruiz-Aranda et al., 2012 ), it is imperative that we understand more about how EI works, and why it leads to its beneficial effects. To develop the “science” of EI, robust methodology is needed to assess how EI relates to automatic, unconscious emotional processing ( Fiori, 2009 ).

Significance of Acute Stress Reactivity and Recovery

One mechanism through which EI may lead to positive effects is by acting as a “stress buffer” ( Mikolajczak et al., 2009 ). EI may minimize the (acute) stress experienced in demanding situations, or situations perceived as demanding. That hypothesis has been used to explain a wealth of adaptive findings across educational (e.g., transition to secondary school), clinical (e.g., suicidal behaviors), and occupational domains (e.g., burnout) ( Day et al., 2005 ; Cha and Nock, 2009 ; Williams et al., 2009 ). When confronted with a stressor, individuals need to initiate a “fight or flight” response, and then shut off the response once the stressor ceases ( McEwen, 2006 ). The extent to which an individual responds to the stressor—stress reactivity—is an important indicator of physiological and psychological functioning ( Henze et al., 2017 ). However, stress researchers disagree on whether hypo (reduced) or hyper (elevated) reactivity is most adaptive in stressful situations (e.g., Phillips et al., 2013 ; Hu et al., 2016 ). Clearly, some reactivity (i.e., not entirely blunted) is necessary for survival. For non-clinical populations, however, hyperreactivity to acute stress is detrimental in most cases. In the short term, high levels of acute stress can impair clinical decision-making in health professionals ( LeBlanc, 2009 ; Arora et al., 2010 ), and the performance of sports players ( Van der Does et al., 2015 ; Rano et al., 2018 ). Hyperreactivity can also adversely impact memory task performance in controlled experimental settings (e.g., Kuhlmann et al., 2005 ; Tollenaar et al., 2009 ), though not always ( Nater et al., 2006 ).

In the long term, dysregulated responses to everyday stressors can accumulate and cause “wear and tear” on the body ( Chida and Hamer, 2008 ), which can sometimes manifest into psychosomatic pathology. For example, individuals can develop hypertension and atherosclerosis ( Matthews et al., 2004 ; Heopniemi et al., 2007 ; Chida and Steptoe, 2010 ). How quickly people recover, or “bounce back,” from acute stress is another revealing aspect of the stress response ( Linden et al., 1997 ). It is well-established that recovering faster from stressful experiences is more adaptive in most contexts (e.g., Burke et al., 2005 ; Geurts and Sonnentag, 2006 ), as this limits unnecessary exposure to the detrimental downstream effects of the “fight or flight” response (i.e., cortisol, cardiac activity, neural activation; McEwen, 2017 ). Taken together, evidence suggests that reduced reactivity, and faster recovery, can be thought of as the “adaptive” pattern of responding to an acutely stressful stimulus.

Because the stress pathway is complex, acute stress can be generated experimentally in many different ways. Common methods include the Velten technique (where participants read self-evaluative statements, such as “I'm discouraged and unhappy about myself”; Velten, 1968 ), or presenting participants with emotive video clips (e.g., Ramos et al., 2007 ). Other methods are more performance-based. Participants can be instructed to prepare and deliver an impromptu speech (e.g., the “gold standard” Trier Social Stress Test; TSST; Kirschbaum et al., 1993 ). While the above procedures typically take place in the laboratory, some experiments use naturalistic stressors, such as an examination, or a competition (e.g., Lane et al., 2009 ). The specific emotions and physiological outcomes that emerge in a challenging situation are highly idiosyncratic, and depend on many stressor characteristics (i.e., levels of social evaluative threat, cognitive effort required; Denson et al., 2009 ). This makes synthesizing findings from studies that have induced stress differently is challenging.

In addition to acute stress induction, researchers also disagree on how best to measure our responses to acute stressors. The full body response to stress involves both arousal of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and the somewhat faster HPA axis, in addition to the subjective experience (e.g., Baumann and Turpin, 2010 ). Measurements can be broadly considered as either (1) “physiological”; endocrine (e.g., cortisol) and ANS activity (e.g., heart rate, electrodermal activity, EEG), or (2) “psychological”; individual's perceptions of their mental state, assessed via self-report questionnaire. While the former, objective measures are free from self-report biases, the latter, subjective measures are also needed for context. For example, an increase in heart rate can result from both negative (e.g., fear) and positive (e.g., excitement) mental states ( Lane et al., 2009 ). Largely due to practicality, however, many studies focus only one aspect of the stress response (i.e., objective or subjective stress), and rarely consider more than one neuroendocrine system (i.e., ANS or HPA-axis reactivity) ( Campbell and Ehlert, 2012 ).

Acute Stress Responding: A Role for EI?

Researchers are increasingly turning to EI in the search for individual differences that influence stress responding ( Matthews et al., 2017 ). If EI is adaptive in stressful situations, high EI scorers should resond more in line with the adaptive profile (reduced reactivity, faster recovery), compared to low EI scorers. Much research so far has been correlational and/or cross-sectional, often restricted to questionnaire-based studies that test for associations between EI and dispositional stress. In most instances, higher levels of EI, especially TEI, correspond with lower levels of perceived occupational or life stress (e.g., Mikolajczak et al., 2006 ; Extremera et al., 2007 ). However, to substantiate claims of EI as a stress buffer, the process needs to be demonstrated “in action,” using controlled, experimental stress paradigms. While responses to laboratory-induced stress are not of clinical importance on their own, they represent the way that individuals ordinarily respond to everyday challenges, which has implications for adaptation ( Henze et al., 2017 ). Identifying the types of stressful situations in which EI relates to stress responding is the next step in helping us to understand how EI works.

TEI and AEI are conceptually distinct ( Pérez et al., 2005 ), supported by the weak correlations between self-report questionnaires and objective testing for EI (e.g., Brackett et al., 2006 ; Brannick et al., 2009 ). Generally, TEI is more strongly linked to adaptive outcomes than AEI ( Harms and Credé, 2010 ; Martins et al., 2010 ). However, one school of thought suggests that TEI and AEI may work together to achieve positive life outcomes (e.g., Davis and Humphrey, 2012 ). Emotional skills (AEI) may be insufficient on their own. Individuals must also feel confident in those skills (TEI) for them to translate into behavior ( Keefer et al., 2018 ). TEI and AEI may therefore influence stress-related processes differently, or be useful in different contexts. We might expect TEI to be especially useful for buffering reactivity in cognitive or psychosocial stress tasks, based on findings from experimental stress studies concerning self-efficacy, self-esteem, and happiness- positive traits that TEI maps onto (e.g., O'Donnell et al., 2008 ; Panagi et al., 2018 ). Research on AEI and stressor-activated processes is comparably scarce. However, links between AEI and selection of adaptive coping strategies ( Davis and Humphrey, 2012 ) could suggest a role for AEI in stress reactivity and recovery. Constructs allied to AEI, such as emotion regulation ability, have also been linked to more adaptive affective responses to acute stress (e.g., Krkovic et al., 2018 ), but the role of other AEI competencies, as measured according to the AEI model (e.g., emotion perception; emotion understanding), are relatively unexplored. Besides EI conceptualization, other methodological factors are important to consider when determining the role of EI in stress processes. It is necessary to consider how studies induce stress, and how they measure stress reactivity and recovery.

The Current Review

To test the hypothesis that EI buffers the effects of acute stress, all relevant experimental studies need to be systematically sourced and evaluated. The primary aim of the present systematic review, is, therefore, to identify emerging patterns regarding EI and stress reactivity and recovery in experimental studies. In particular, we aim to highlight types of stressful situation in which EI might be especially pertinent. Second, the review aims to examine aspects of methodological variation upon which the relationship between EI and reactivity may depend: EI measurement (TEI; AEI), stress induction paradigms, and stress measurement. Study quality will also be assessed to identify any common methodological study limitations.

Search Strategy

This review followed the PRISMA protocol ( Moher et al., 2009 ). PsycInfo, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Search Complete were searched exhaustively for studies investigating EI and stress reactivity. The term emotional intelligence was used, combined with any of the following keywords: stress, mood, affect, emotion * state, emotion regulat * , coping, heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure, cortisol, skin conductance, electrodermal activity, EEG, reactivity , or recovery . Reference lists of full text articles were also manually searched. Searches focused on studies published between 1990 and the present day, to correspond with the advent of Salovey and Mayer's paper where the EI concept was first introduced into the scientific psychological literature ( Salovey and Mayer, 1990 ). Database searching took place during July 2018.

Eligibility Criteria

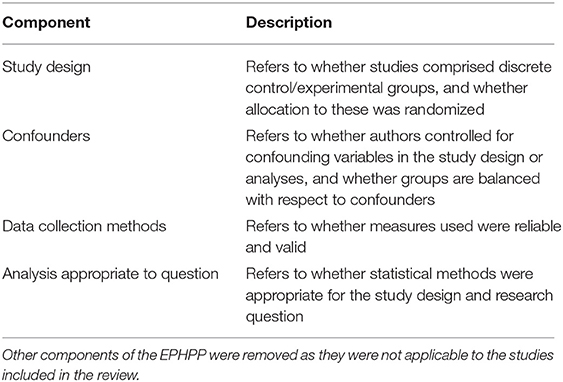

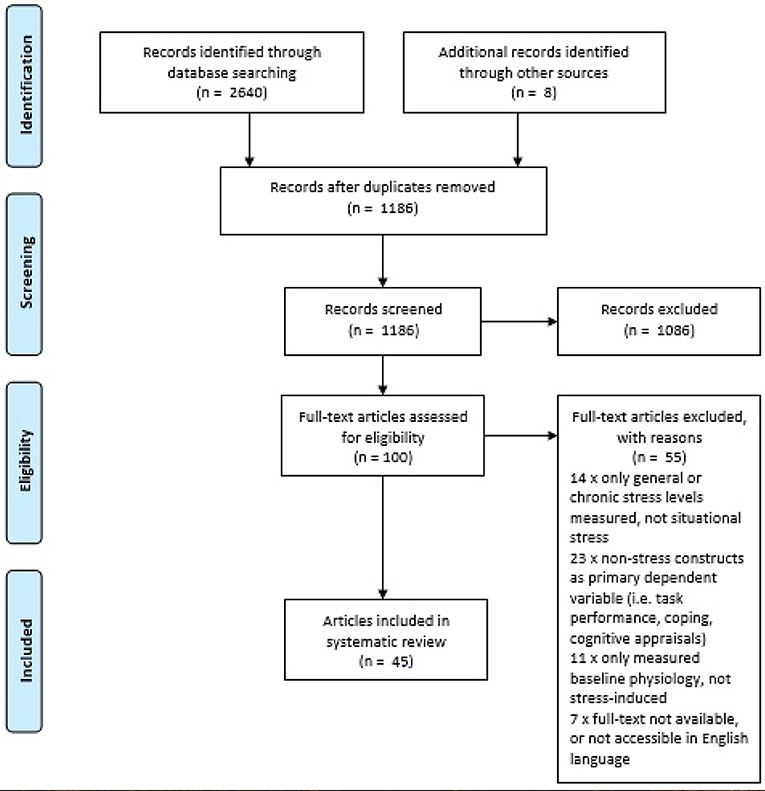

Studies were included in the review if they met four inclusion criteria. First, only primary empirical quantitative research was included (i.e., not reviews, theoretical papers, or meta-analyses). Second, articles were required to define and measure EI explicitly using established models of EI, rather than just a single related facet (e.g., emotion regulation). We focused on overall EI to represent how EI is typically conceptualized with relation to life outcomes ( Brackett et al., 2011 ), and within training programmes (e.g., Nelis et al., 2011 ). Examples of commonly used, acceptable TEI measures include the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue; Petrides, 2009 ), comprised of emotionality, sociability, self-control, and wellbeing subscales, and the Trait Meta Mood Scale (TMMS; Salovey et al., 1995 ), formed of clarity, repair, and attention subscales. Fewer AEI measures are available, the most popular tool being the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Mayer et al., 2002 ), which provides a four-branch assessment: perceiving emotions, using emotions to facilitate thought, understanding emotions, and managing emotions. Third, the outcome of interest was restricted to acute stress reactivity (i.e., a response to a situational stressor or mood induction). Outcomes could be either psychological (e.g., self-reported negative affect, or perceived stress), or physiological (e.g., cortisol, HR, EDA), or a combination. Fourth, participants were limited to non-clinical populations, to counteract the confounding influence that clinical symptomology can have on the stress response ( Burke et al., 2005 ; De Rooij et al., 2010 ), but the participant sample could be of any age. Articles were also required to be available in full, and in the English language. If articles were unavailable, authors were contacted to request access. Studies were excluded if they did not meet all criteria. Many studies were excluded because they only included a measure of general perceived stress (e.g., work stress, life stress), rather than stress levels following a stress manipulation, or because they measured outcomes other than stress reactivity or recovery (e.g., task performance, coping). The first and second author independently screened the abstracts for suitability, and no inclusion discrepancies were identified. For details of the screening and selection process, see the PRISMA flow chart ( Figure 1 ). Individual studies were appraised using an adapted version of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies ( Table 1 ; Effective Public Health Practice Project, 1998 ), owing to its excellent psychometric properties (e.g., Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012 ).

Table 1 . Adapted EPHPP tool for methodological quality of studies (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 1998 ).

Figure 1 . PRISMA 2009 flow diagram of search results ( Moher et al., 2009 ).

Study Characteristics

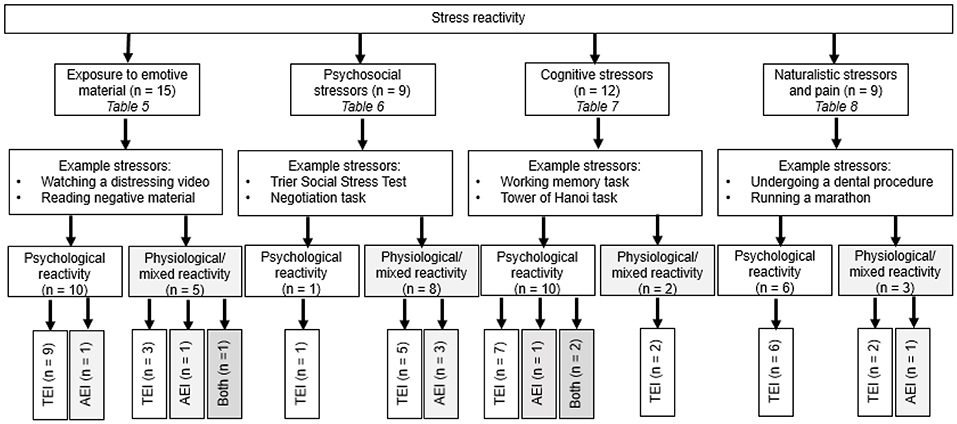

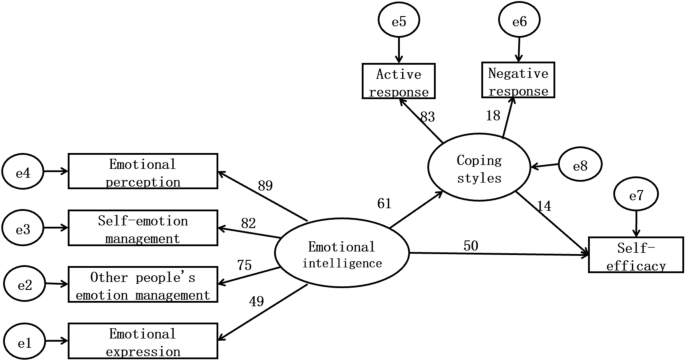

The search identified 40 papers (45 studies) for inclusion in the review. Publication location spanned 14 countries. Of the included studies, 42 used an adult sample, most of which consisted of university undergraduate students. Only three studies conducted research with younger populations: one with adolescents ages 13–15 years, and two with children ages 7–12 years. Studies varied in terms of EI instrumentation, stress induction procedure, and stress measurement. Figure 2 provides an overview of the stress reactivity studies identified.

Figure 2 . Overview of stress reactivity studies included in the review. AEI, ability emotional intelligence; TEI, trait emotional intelligence; both, measurement of both TEI and AEI; psychological stress reactivity, subjective measurements of reactivity (e.g., affect, mood, self-reported stress); physiological/mixed stress reactivity, objective measurements of stress reactivity (e.g., heart rate, cortisol, electrodermal activity), either alone or used alongside a psychological measure.

EI Instruments

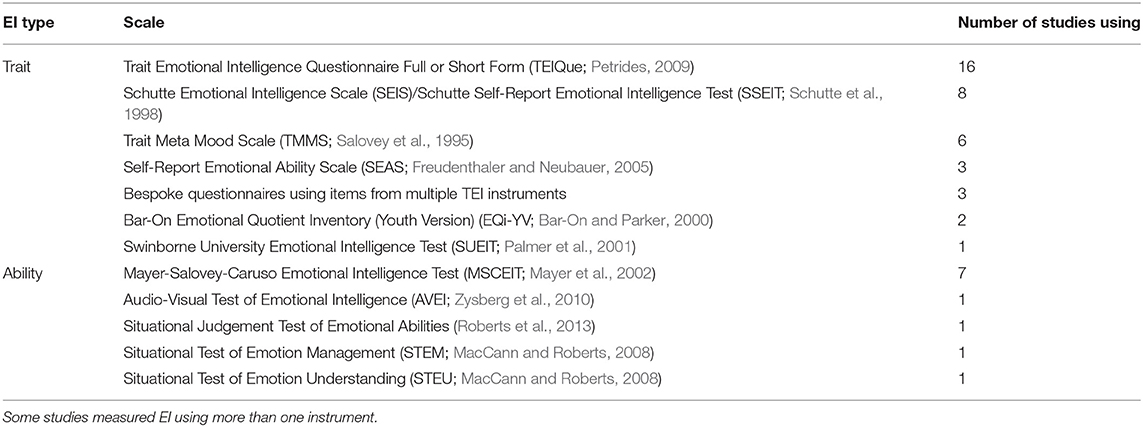

Thirty-four studies (78%) measured TEI, seven (16%) measured AEI, but only three (7%) measured both TEI and AEI. The TEIQue and MSCEIT were the most common tools for assessing TEI, and AEI, respectively. Half of the studies explored contributions from EI from a subscale level, in addition to the global score. Three studies by Papousek et al. (2008 , samples 1 and 2; 2011) used only select subscales from a TEI measure (Self Report Emotional Ability Scale; SEAS: “perception of the emotions of others” and “regulation of one's emotions”). Table 2 details the breadth of tools utilized to measure EI across the review.

Table 2 . EI measurement tools used in the review.

Types of Stressors Used

As expected, methods of stress induction varied between studies (see Figure 2 for examples of stressors used). Fifteen (33%) of the 45 studies in the review used passive methods of mood induction, in which participants viewed, read, or listened to, emotive material, but were not required to actively perform a task. The remaining 30 (67%) studies used either cognitive tasks (12 studies), psychosocial stress (9 studies), or more naturalistic stressors, such as a sporting task (6 studies) or physical discomfort (3 studies).

Stress Measurement

Twenty-nine studies (64%) examined subjective (self-reported) reactivity, eleven examined objective (physiological) reactivity (24%), and six examined both types of reactivity within the same experiment (12%). Generally, participants' acute psychological stress was conceptualized as the change in negative affect (NA) from baseline, for which the most popular mood assessment tool was the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) , selected by 11 studies. Physiological stress was measured in a number of ways, including: cardiac measures (10 studies), cortisol secretion (6 studies), electro-dermal activity (EDA) (4 studies), or EEG (1 study). Depending on whether EI was conceptualized as a categorical or continuous variable, the principal measure was either the difference in mean reactivity/recovery between high-EI and low-EI individuals, or the relationship between EI and reactivity/recovery.

Synthesized Findings

Studies in the review were principally classified according to the stressor context. Studies were further evaluated according to the type of EI model employed, and the type of stress reactivity assessment. Thus, the results section consists of: (1) Exposure to emotive material, (2) Psychosocial stress, (3) Cognitive tasks, and (4) Naturalistic stress and pain. Study findings relating to recovery from acute stress are considered separately (5). Because some studies explored multiple stress contexts, studies may appear under more than one heading. Where sufficient studies allowed, sections were further divided into subheadings: psychological reactivity, and physiological or mixed reactivity. Here, “mixed” refers to studies that included assessment of both psychological and physiological reactivity.

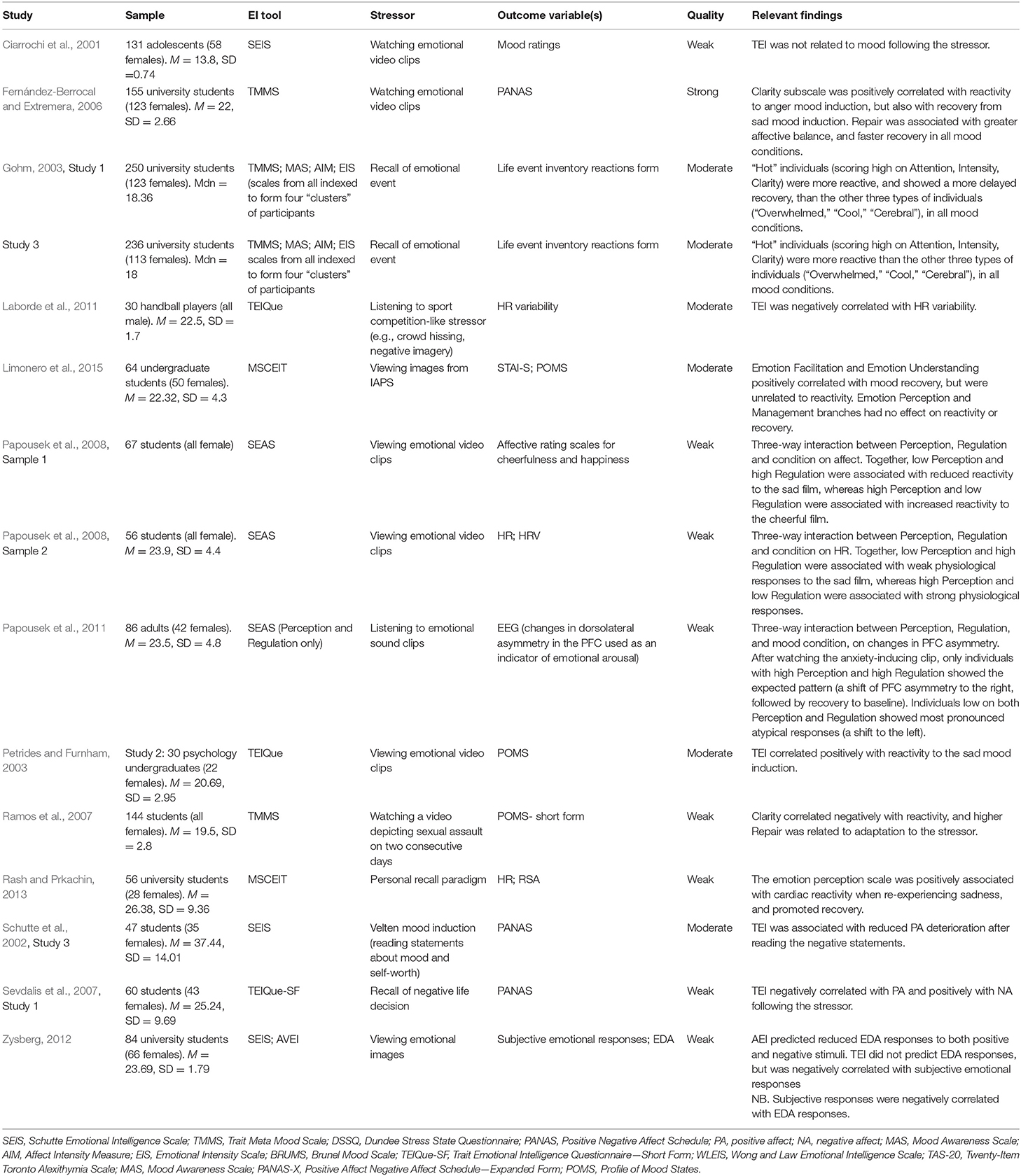

1. Exposure to Emotive Material (Table 3)

Neither TEI nor AEI robustly predicted reactivity when exposed to visual, mentally recalled, or written emotive material. Some TEI studies indicated that TEI increased reactivity, but others found a negative relationship. AEI did not significantly predict reactivity in either direction.

Table 3 . Studies that measured EI and reactivity during exposure to emotive material.

Psychological reactivity

The relationship between TEI and psychological stress was assessed in many studies. TEI increased reactivity when watching a holocaust documentary ( Petrides and Furnham, 2003 ), and an apartheid clip ( Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera, 2006 ). However, only the clarity subscale of the TMMS (which represents a perceived ability to discriminate clearly between emotions) was significant. Similarly, when participants were asked to recall a regrettable life decision, high TEI individuals presented a stronger emotional reaction ( Sevdalis et al., 2007 , Study 1). TEI also decreased reactivity in some cases, however. Ramos et al. (2007) , Zysberg (2012) , and Schutte et al. (2002 , study 3) showed that high TEI scorers were less reactive to emotive video, images, and negative written statements, respectively. The only study to use an adolescent sample in the review ( Ciarrochi et al., 2001) found no relationship between TEI and mood changes while watching a negative film.

Findings were more complicated when studies considered TEI “profiles”- differing levels of multiple subscales, rather than global TEI or single subscales. Papousek et al. (2008 , sample 1) found that individuals scoring low on emotion perception, but high on emotion regulation, showed reduced psychological reactivity after viewing a sad emotional video clip. The reverse pattern was found for high perception but low on regulation. In essence, individuals who could perceive their emotions accurately, but not regulate them, were affected by the sad film to a greater extent. Gohm (2003, study 1) took a different approach, combining items from several TEI scales to form four “clusters” of participants (“hot,” “overwhelmed,” “cool,” “cerebral”). Of those clusters, “Hot” individuals (scoring high on attention, intensity, and clarity) were more reactive than the three other types when recalling an emotional event. That finding was replicated in a subsequent study ( Gohm, 2003 , study 3).

Two studies examined links between AEI and psychological reactivity to emotional images. In both cases, AEI had no effect on responses ( Zysberg, 2012 ; Limonero et al., 2015) .

Physiological or mixed reactivity

As before, findings were complex when TEI profiles were considered. When viewing sadness-inducing video clips, individuals scoring high on emotion perception, but low on emotion regulation subscales, showed increased cardiac reactivity ( Papousek et al., 2008 , sample 2). In contrast, low perception and high regulation scorers showed reduced reactivity. The same research group ( Papousek et al., 2011 ) also found a relationship between subscales of the TEI and EEG outputs. After watching an anxiety-inducing clip, only those with both high emotion perception and high emotion regulation showed the expected EEG pattern (a shift of PFC asymmetry to the right). Individuals with low scores on these branches showed the most pronounced atypical response (a shift to the left), suggesting greater emotional arousal and poorer emotional regulation. Rash and Prkachin (2013) instead focused on AEI and physiological reactivity to recalling a sad memory. During the recall, individuals scoring highly on the perceiving emotion branch of AEI showed more extreme increases in HR than their low scoring counterparts.

Only one study ( Zysberg, 2012 ) examined the role of both TEI and AEI in the context of both psychological and physiological reactivity. Findings identified different roles for TEI and AEI. When viewing negatively-valenced images, AEI (but not TEI) buffered EDA reactivity, whereas TEI (but not AEI) buffered emotional responses.

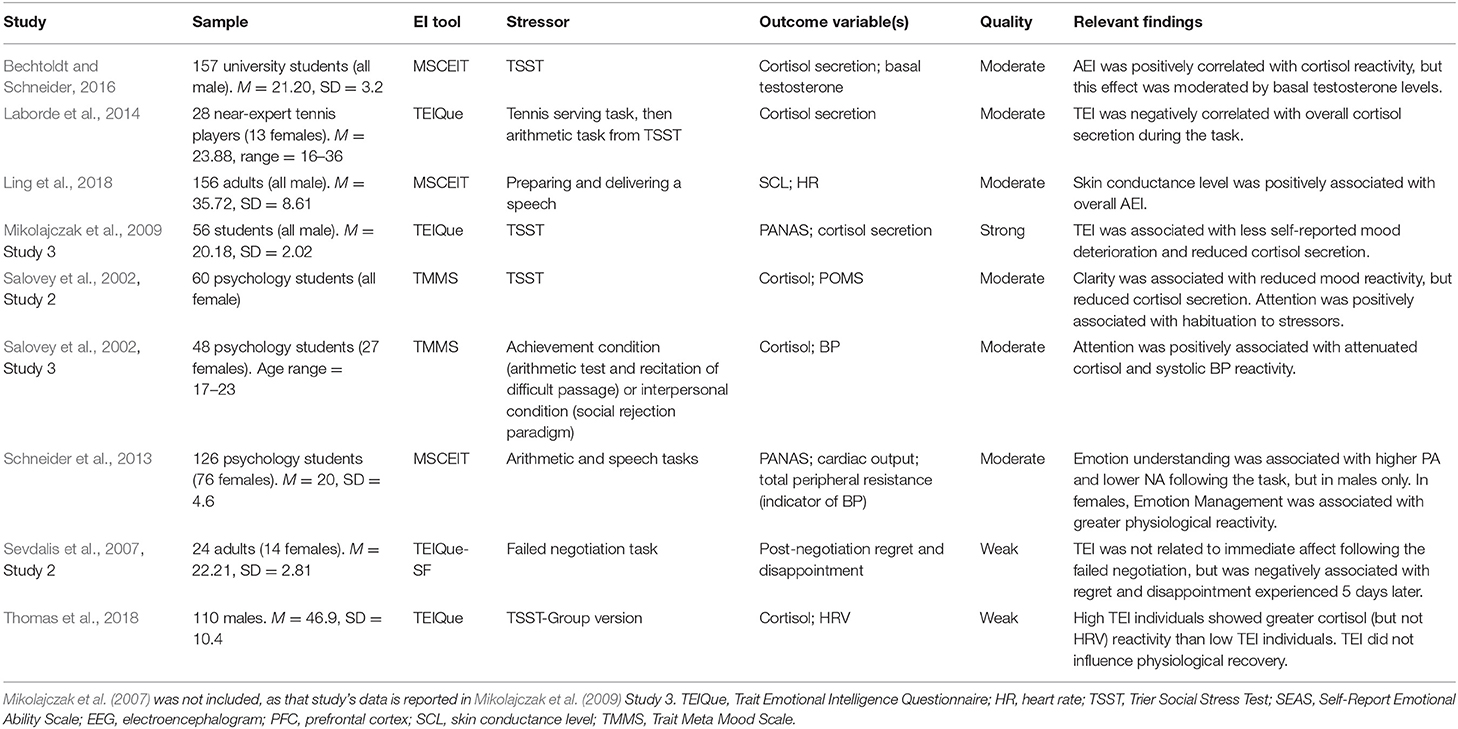

2. Psychosocial Stress (Table 4)

Studies in this section induced stress through social evaluation. Most stressors were based on the highly standardized TSST protocol, where participants perform public speaking and mental arithmetic tasks in front of an audience ( Kirschbaum et al., 1993 ). No clear pattern emerged concerning TEI and reactivity to psychosocial stressors. Though studies were limited in number, physiological reactivity appeared to increase as a function of overall AEI.

Table 4 . Studies that measured EI and reactivity to psychosocial stress.

In a small-sample study by Sevdalis et al. (2007 , study 2, n = 24), participants took part in a negotiation task, where all failed by default. TEI failed to predict feelings of regret and disappointment, as assessed via two 5-point rating scales.

Findings were inconsistent with regard to TEI and physiological reactivity. Mikolajczak et al. ( 2009 , study 3) 1 showed that TEI attenuated both cortisol reactivity and mood reactivity to the TSST. However, in a group version of the same task, Thomas et al. (2018) found the opposite: TEI predicted increased cortisol reactivity, but had no impact on HR. Another study showed that the TEI attention to emotion subscale (with items including, “I pay a lot of attention to how I feel”) exacerbated both cortisol and HR reactivity ( Salovey et al., 2002 , Study 3). With regards to AEI, higher levels represented greater cortisol secretion ( Bechtoldt and Schneider, 2016 ) and EDA reactivity ( Ling et al., 2018 ) to speech performances. Schneider et al. (2013) also focused on AEI, but with a particular emphasis on sex differences. Emotional understanding was associated with less mood deterioration in males, whereas emotion management was associated with greater cardiac reactivity in females.

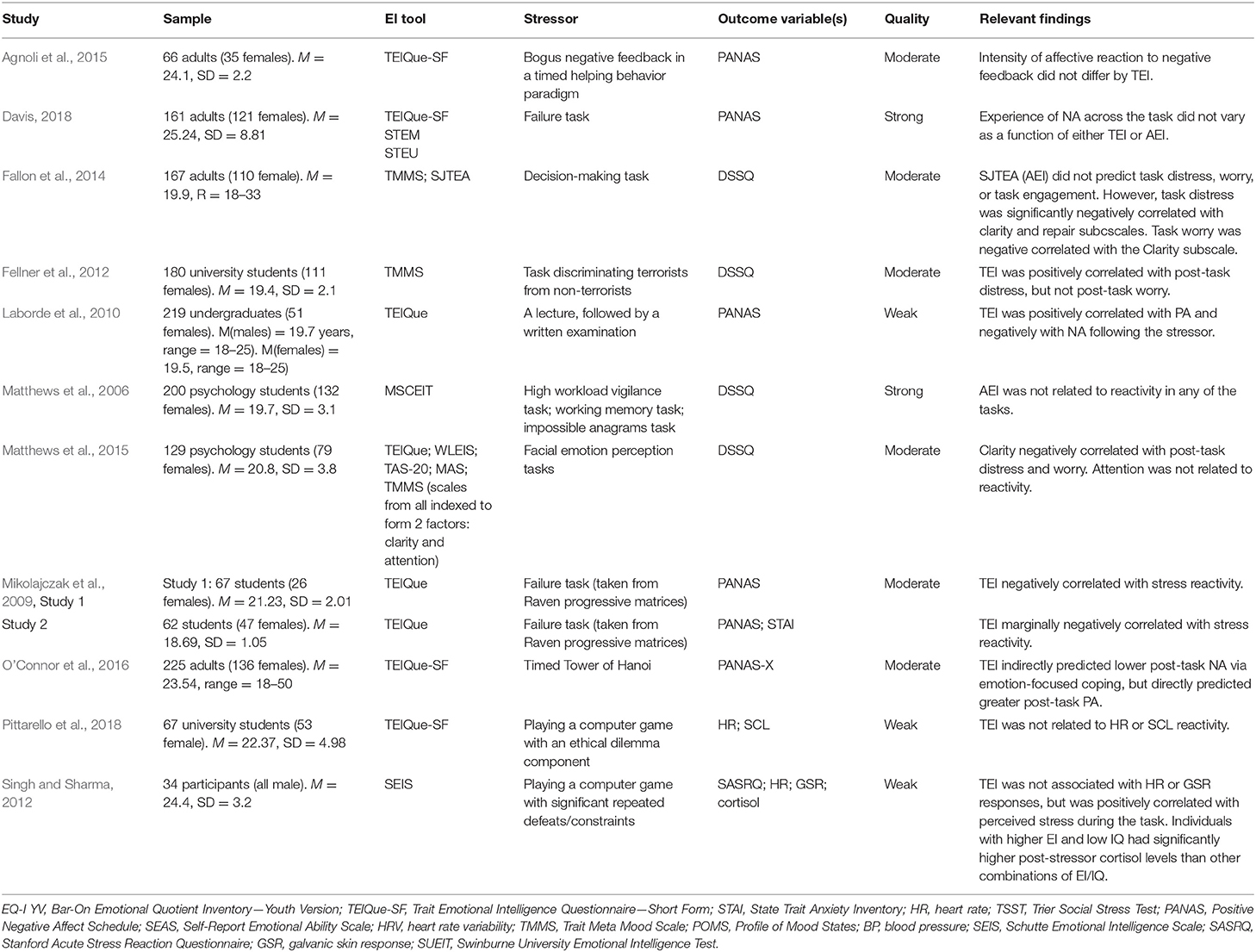

3. Cognitive Tasks (Table 5)

Stressors were classified as cognitive if they primarily assessed a mental process (e.g., attention, memory). Stress was typically induced from the difficulty of the task, and in some cases, it was impossible for the participant to perform well due to unrealistic time restraints, for example. The vast majority of these studies assessed the role of TEI, with most of those limited to psychological reactivity. While TEI buffered psychological reactivity in some computerized tasks, AEI was unrelated to reactivity.

Table 5 . Studies that measured EI and reactivity to cognitive tasks.

TEI buffered the effects of psychological stress in some cases. For example, global TEI score dampened the psychological stress induced by written examinations ( Laborde et al., 2010 ). A similar pattern of findings also applied to multiple laboratory tasks. TEI predicted less mood deterioration following a facial perception task ( Matthews et al., 2015 ), a mathematical puzzle ( O'Connor et al., 2016 ), and a difficult IQ test ( Mikolajczak et al., 2009 , studies 1 and 2). In contrast, TEI was associated with increased distress during a terrorism-themed discrimination task ( Fellner et al., 2012 ). In a computer game where participants received bogus negative feedback on a computerized task, TEI was unrelated to self-reported stress ( Agnoli et al., 2015 ).

AEI was not significantly associated with psychological reactivity to a range of cognitive stressors, including tasks of working memory, vigilance, and impossible anagrams ( Matthews et al., 2006 ). Two studies explored the role of both TEI and AEI in responding to cognitive stressors. The failure task paradigm employed by Davis (2018) indicated non-significant effects for both TEI and AEI on mood changes. However, Fallon et al. (2014) identified that effects of EI on reactivity to a decision-making task were dependent on EI type. While the clarity (e.g., “I am rarely confused about how I feel”) and repair (e.g., “I try to think good thoughts no matter how badly I feel”) subscales of the TMMS TEI measure predicted less psychological stress, AEI was unrelated to reactivity.

TEI did not predict physiological reactivity in two studies that used a computer game to induce stress. On both occasions, EDA and HR reactivity was unrelated to TEI ( Singh and Sharma, 2012 ; Pittarello et al., 2018 ). However, the latter study also considered TEI/IQ combinations, and found that a high TEI/low IQ combination was the most detrimental to cortisol reactivity. In that same study, TEI was associated with lower levels of perceived stress. Thus, while high TEI levels were protective on their own, they became harmful when paired with low IQ.

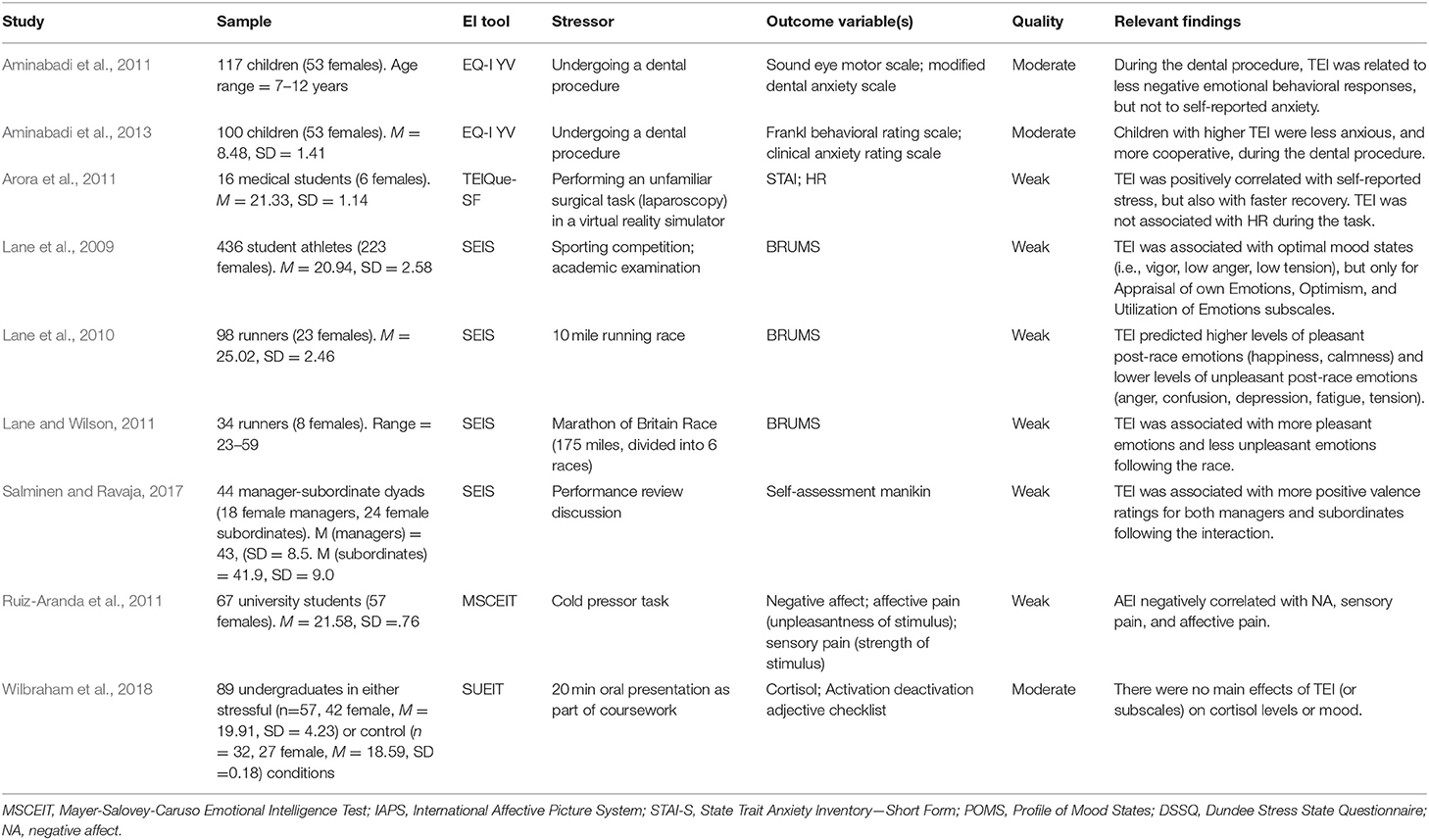

4. Naturalistic Stress and Pain (Table 6)

Naturalistic stressors were defined as challenges that occurred naturally in the participants' everyday life (e.g., a sporting competition), or challenges that were generated to closely resemble such as situation. Evidence supported a protective role for TEI and AEI in stressful sports and pain-related contexts.

Table 6 . Studies that measured EI and reactivity to naturalistic stressors.

Higher TEI levels were strongly linked to more positive affect (and less negative affect) in sport-based stressors. A series of studies by Lane et al. showed that TEI promoted positive mood states during sports events, including a competition ( Lane et al., 2009 ), a 10-mile running race ( Lane et al., 2010 ), and a 175-mile marathon ( Lane and Wilson, 2011 ). In each case, the high TEI participants had lower levels of negative emotions (e.g., anger, tension), and higher levels of positive emotions (e.g., happiness, calmness), a pattern associated with optimum performance ( Lane et al., 2009 ). Higher employee TEI was also associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing positive emotions following a performance review discussion with a manager ( Salminen and Ravaja, 2017 ).

Three studies examined the role of EI when responding to a painful stimulus. Two of those examined reactivity within a dental setting. During a dental procedure, children with higher TEI were less likely to display negative behavioral responses (e.g., crying, sudden body movements), than low TEI children ( Aminabadi et al., 2011 , 2013 ). The other study found that higher levels of AEI predicted less self-reported negative affect and pain during a cold pressor task, where the participant immerses their hand in freezing cold water ( Ruiz-Aranda et al., 2011 ).

As with psychological reactivity, findings were promising regarding TEI and physiological reactivity in a sporting context. During a pressurized sports activity, near-professional tennis players secreted less cortisol if they had higher TEI ( Laborde et al., 2014 ). The same research group found similar findings with a different approach. Handball players were exposed to an auditory stressor that included negative sports-related sounds, such as crowds hissing ( Laborde et al., 2011 ). When listening, the high TEI athletes experienced less cardiac reactivity compared to their low TEI counterparts.

TEI was less effective in other naturalistic settings. During an assessed presentation as part of an undergraduate psychology course, TEI neither increased nor decreased participants' cortisol levels ( Wilbraham et al., 2018 ). Arora et al. (2011) focused on the capacity of TEI to buffer situational stress for medical students performing unfamiliar surgical tasks. While TEI was unrelated to HR reactivity, higher TEI was associated with increased psychological stress.

5. Stress Recovery

A small number of studies ( n = 6) included some assessment of stress recovery. In four of those cases, high EI individuals recovered faster than low EI individuals. For example, despite showing greater reactivity initially, high TEI individuals showed faster psychological recovery 15 min after watching an anger-provoking video ( Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera, 2006 ), and after completing an unfamiliar task ( Arora et al., 2011 ). However, Thomas et al. (2018) found no link between TEI and recovery 7 min after the group version of the TSST. TEI was related to stronger feelings of regret and disappointment 5 days after a failed negotiation ( Sevdalis et al., 2007 ), a recovery period considerably longer than that used in the other studies. TEI was associated with stressor habituation (reduced reactivity upon extended/repeated exposure). Female university students that scored high on the emotional regulation TEI scale were less reactive when re-watching a distressing video depicting sexual assault that they had seen 2 days previously ( Ramos et al., 2007 ). Another TEI scale—attention to emotions—also promoted habituation to the TSST ( Salovey et al., 2002 , Study 2).

AEI facilitated stress recovery in two studies. Limonero et al. (2015) , assessed mood 15 min after exposure to emotional images. Mood returned to baseline faster for participants with higher scores on facilitation and understanding branches. Similarly, after recalling a sad memory, mood repair was faster when individuals had higher scores on the perception branch ( Rash and Prkachin, 2013 ).

The final review identified 45 studies from 14 countries, from diverse settings including healthcare (e.g., Arora et al., 2011 ), sport (e.g., Lane and Wilson, 2011 ), organizational psychology (e.g., Salminen and Ravaja, 2017 ), and education (e.g., Wilbraham et al., 2018 ). This highlights that EI has cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary pertinence. The discussion section will (1) summarize the main findings, (2) discuss the measurement of EI across the studies reviewed, (3) identify study limitations, (4) discuss the limitations of this review, and, (5) suggest implications for EI in terms of adaptation, and propose future research directions.

Summary of Main Findings

The first aim of the review was to examine the relationship between TEI, AEI, and stress reactivity and recovery. If EI is truly adaptive in acutely stressful conditions, high EI scorers should show the adaptive stress responding profile (i.e., reduced reactivity, faster recovery; Keefer et al., 2018 ). As expected, findings differed according to the EI type and stressor used.

Stress Reactivity: The Role of TEI

Overall, evidence concerning the role of TEI in psychological or physiological reactivity was mixed. Depending on the context, TEI increased reactivity, decreased reactivity, or had no significant effects. TEI appeared especially useful in sport. High TEI buffered reactivity to both passive (e.g., crowd hissing) and active (e.g., competition) sports-based stressors, a finding that was applicable to both psychological (e.g., Lane et al., 2010 ) and physiological stress ( Laborde et al., 2014 ). The pertinence of TEI to sports-based stressors may reside in the structural basis of the construct. TEI can be conceptualized as “emotional self-efficacy”: one's self-confidence and belief in their emotional abilities ( Petrides et al., 2007 ). Self-efficacy is one of the most influential determinants of sport performance, ( Feltz et al., 2008 ), a phenomena that could be attributable to the many “rewards” available for performing well in sports contexts (e.g., winning a competition, beating a personal best, etc.). Incentives are deemed necessary for the “activation” of self-efficacy ( Bandura, 1977 ). One could speculate that, as a related construct, TEI could work similarly by actively dampening the stress response in situations where “doing well” greatly benefits the individual (e.g., a marathon). Similarly, high TEI buffered affective responses in other “at risk” naturalistic settings where the individual was at risk of pain or physical discomfort.

TEI was unrelated to physiological responding when completing cognitive tasks under controlled conditions. However, the intensity of affective responses was buffered by TEI in most cases. Perhaps, during times of cognitive challenge, TEI facilitates deployment of adaptive cognitive mechanisms to regulate emotional responses. There has been relatively little evidence in the context of state coping (i.e., coping during the stressor). However, the limited body of work suggests that TEI facilitates coping strategy selection under acute stress ( Salovey et al., 2002 ; Matthews et al., 2006 ; O'Connor et al., 2016 ). High TEI individuals typically select more adaptive, active methods of coping (e.g., problem-solving) over maladaptive, passive methods (e.g., avoidance coping; Austin et al., 2010 ). Furthermore, high TEI individuals appraise tasks as a challenge, rather than a threat ( Mikolajczak and Luminet, 2008 ). This cognitive appraisal pattern fosters adaptive levels of reactivity, and enhances task performance ( Maier et al., 2003 ). TEI is also associated with an attentional bias for positive emotions ( Szczygieł and Mikolajczak, 2017 ; Lea et al., 2018 ), which could be helpful during demanding situations. For example: during a written exam, a student with greater TEI may experience less negative affect, allowing them to invest more mental resources in answering the exam questions, thus potentially resulting in greater academic achievement than a student with low TEI. What is less clear, is why high TEI did not protect individuals from socially evaluative stressors. TEI only reduced cortisol and mood reactivity in one study ( Mikolajczak et al., 2009 , study 3). In other studies, TEI or its component subscales either had no effect, or increased reactivity. Notably, when students delivered a presentation as part of their coursework (i.e., in a naturalistic setting), TEI failed to produce any effects on mood or cortisol reactivity ( Wilbraham et al., 2018 ). Considering that enhanced emotional and social functioning should constitute a core hallmark of TEI ( Fiori, 2009 ), findings challenge the claim that TEI buffers stress in all social contexts.

Many studies showed that TEI intensified emotional reactivity to material designed to evoke negative emotion (e.g., Petrides and Furnham, 2003 , study 2). This could suggest that compared to their low TEI peers, high TEI individuals are more likely to notice their negative emotions and pay attention to them. Alternatively, rather than being the result of maladaptive psychological processing of the stressor, it could be that on those occasions, high TEI individuals believed they should be impacted negatively by negatively valenced material. They could have then over-reported this via subjective reports of mood change. Evidence exploring TEI and physiological reactions (free from demand bias) supports that hypothesis, since high TEI individuals did not necessarily show adaptive physiological responses to emotive material. However, the balance between TEI facets appeared important. For maximum benefit, individuals needed to score highly on their perceived ability to both perceive and regulate emotion.

Stress Reactivity: The Role of AEI

A dearth of AEI studies was apparent across all stressor types. However, based on the pool of evidence available within the review, findings were much less supportive of a role for AEI than TEI. AEI was either non-significant or detrimental in most cases. Notably, AEI was related to maladaptive physiological responses in intra-personal settings (e.g., Bechtoldt and Schneider, 2016 ). This contradicts suggestions that AEI should strongly predict adaptive criteria in such environments ( Matthews et al., 2017 ). AEI also failed to predict reactivity to cognitive tasks (e.g., Matthews et al., 2006 ), and when confronted with emotive stimuli, findings were conflicted. In general, explanatory pathways with regard to AEI are less straight-forward, and it is difficult to speculate how and why AEI might implicate (or not implicate) the stress response pathway. It has been suggested by Ciarrochi et al. (2002) that maladaptive effects of AEI could stem from one of two possible accounts, where emotion perception skill plays a key role. First, emotionally perceptive people might be hypersensitive to emotion, and therefore less likely to try and repress the mental and physical sensations associated with negative experiences. Second, highly perceptive individuals might be less confused about what they are feeling, and are thus more aware of the meaning of such sensations. Taken together, findings align with contemporary concerns that high levels of AEI may not always be optimal for adaptation ( Davis and Nichols, 2018 ).

The roles of both TEI and AEI in facilitating outcomes (i.e., stress reactivity) need to be understood ( Davis and Humphrey, 2012 ). However, the vast majority of studies in the review explored the effects of TEI only, and only three studies examined both TEI and AEI simultaneously. Zysberg (2012) identified different roles for TEI and AEI (TEI; buffers psychological reactivity; AEI buffers physiological reactivity). The other two studies only examined effects on psychological reactivity. While both identified no benefit for high AEI ( Fallon et al., 2014 ; Davis, 2018 ), TEI helped maintain positive mood in one case ( Fallon et al., 2014 ). Even when studies used the same stress induction paradigm (TSST), and measurement (cortisol secretion), divergent findings were identified for TEI (less reactive; Mikolajczak et al., 2009 ) and AEI (more reactive; Bechtoldt and Schneider, 2016 ). This suggests that TEI and AEI may operate differently in stressor-activated processes. However, more studies evaluating respective roles of both TEI and AEI in stressful situations are clearly needed. Considering TEI/AEI “profiles” (high TEI/low AEI, high AEI/low TEI etc.), could prove a fruitful approach for future studies to take. It could be that the effects of AEI on stress reactivity (which were often negative or non-significant in the present review) depend on the level of TEI. For example, having high levels of emotional skill (AEI) can be deleterious for psychological adaptation if the individual does not possess a sufficient level of emotional self-confidence (TEI) ( Davis and Humphrey, 2014 ).

Stress Recovery: The Roles of TEI and AEI

Recovery from acute stress is sometimes viewed an empirically neglected “conceptual sibling” of reactivity ( Linden et al., 1997 ). A capacity to recover quickly from stress generally affords long term health benefits, by preventing exaggerated or prolonged activation of the sympathetic and HPA axis response systems (e.g., Burke et al., 2005 ; Geurts and Sonnentag, 2006 ). Few studies examined the role of EI in the stress recovery process. However, both TEI and AEI generally conveyed advantages for a range of stressful experiences. The mechanisms linking TEI and AEI to enhanced recovery are unknown, but the wider literature provides nascent support for the role of two related cognitive processes: post-stressor rumination (dwelling on the negative experience of the stressor after its end), and post-stressor intrusive thoughts (involuntary, unwelcome thoughts or images about the stressful experience). Lanciano et al. (2010) found that individuals that scored highly on the emotion management branch of AEI ruminated less about their stressful experiences. Similarly, people with high TEI (clarity of emotions subscale) experienced less intrusive thoughts (e.g., “I thought about [the stressor] when I didn't mean to”) post-stressor ( Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera, 2006 ). Since rumination and intrusive thoughts can hinder the stress recovery process ( LeMoult et al., 2013 ), it could follow that TEI and/or AEI might inhibit the focus on one's distress after the immediate threat has passed. Perhaps, via increased attendance to positive emotions ( Szczygieł and Mikolajczak, 2017 ; Lea et al., 2018 ). More studies examining both TEI and AEI, using shared methodology, are required before conclusions about their roles with respect to acute stress recovery can be confidently drawn.

Measurement of TEI and AEI

A second aim of the review concerned the typical methodology (e.g., EI instrumentation) used when exploring the effects of EI on acute stress responding. A considerable problem in the field of EI is that there is no clear definition or “gold standard” measures. This has resulted in a plethora of measures, particularly for TEI, which differ in their theoretical assumptions and factor structures ( Zeidner and Matthews, 2018 ). For example, unlike other popular TEI measures such as the TEIQue, the TMMS does not yield a global score, and lacks many core facets of the TEI construct, such as sociability ( Pérez et al., 2005 ). Thus, synthesizing findings that relate to different TEI conceptualisations may not be valid. Eventually, with more studies, and replication of methods, a meta-analysis could determine strength of effects according to EI instrumentation and stressor type. Studies also differed in their analytic strategy. Heterogeneity of methodology means that at present, testing for a “common effect” in this way would not be possible. While half of the studies only performed analyses at the global level (i.e., total score), the rest followed a promising line of enquiry by performing sub-analyses with EI components, which helps to pinpoint effects at the sub-facet level. In those studies, significant effects were often restricted to certain subscales (e.g., clarity scale of the TMMS; Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera, 2006 ), supporting that strategy. In addition, subscale analysis would help address the extent to which certain EI subscales (e.g., the wellbeing scale of the TEIQue) confound with stress outcomes. What is problematic, however, is when studies only measured/reported select subscales from a broader measure (e.g., Papousek et al., 2008 , 2011 ), as this makes it more difficult to elucidate EI's role.

A large number of studies examined the relationship between TEI (i.e., self-reported EI) and psychological reactivity (i.e., self-reported stress). When both predictors and criterion measures are self-reported, there is the risk that findings may have arisen due to shared measurement error, rather than true associations (“contamination”; Keefer et al., 2018 ). Thus, the effects of TEI on health indices tend to be weaker when outcomes are measured objectively, as shown in the present review. In addition, self-report behavioral trait questionnaires assume individuals have sufficient insight into their own emotional functioning, and are thus susceptible to socially desirable responding ( Day and Carroll, 2008 ; Tett et al., 2012 ). It is therefore important to consider TEI findings alongside those for AEI, a more objective index of emotional skills and abilities. However, as discussed, few studies examined AEI. In those few studies, a narrow breadth were used, with the majority of studies using the MSCEIT. Commentators argue that implementation of alternative measurement tools is required to fully differentiate test effects from construct effects and avoid “mono-method bias” ( Matthews et al., 2007 ). In other words, researchers should use a range of AEI tools to demonstrate that effects are not merely a product of the way in which the MSCEIT measures emotional skills. Non-commercial alternatives have since been developed to address this need (e.g., STEM and STEU; MacCann and Roberts, 2008 ), though these are not often used, as reflected by present review (see Table 2 ).

Study Limitations

The quality appraisal process showed that of the 45 studies, most conferred a weak ( n = 18) or moderate ( n = 21) rating. A strong rating was only received by four studies (see Tables 3 – 6 ). The main issues—the dearth of evidence for physiological reactivity studies, stress induction robustness, and, lack of consideration for confounding influences—will now be discussed.

Only a third of studies assessed physiological stress. This is congruent with the findings relating to EI measurement: researchers in the review tended to select subjective measures (i.e., TEI) over objective measures (i.e., AEI). Assessment of physiology in reactivity experiments could prove particularly insightful, given that the physiological aspects of reactivity are strongly associated with adverse health outcomes (e.g., Lopez-Duran et al., 2015 ). Using physiological measures also reduces the risk of methodological “contamination” occurring from an overreliance on self-report (described above). Furthermore, we cannot assume that perceived stress adequately represents physiology, since the literature often indicates negligible associations ( Oldehinkel et al., 2011 ). Indeed, one meta-analysis concluded that significant correlations between perceived stress and physiological stress are only found in approximately 25% of cases ( Campbell and Ehlert, 2012 ). Of the few studies in the review that captured both types of stress measurement, effects were rarely consistent across both. The degree and strength of concordance can depend on many factors, such as age, gender, and body composition ( Föhr et al., 2015 ). For those reasons, multi-method approaches (i.e., using physiological methods alongside questionnaires) are preferred ( Andrews et al., 2013 ). Some also argue that to truly understand the full body response, both ANS (e.g., HR) and HPA-axis (e.g., cortisol) markers should be measured, since these systems are highly coordinated and interconnected ( Rotenberg and McGrath, 2016 ). Future work should continue to evaluate the respective roles of TEI and AEI in stressful situations using both psychological and physiological measurements.

Another key issue relates to the robustness of stress induction paradigms used. A broad range of stress induction procedures were identified in the review (see Figure 2 ). Only 10 studies (22%) included an explicit control group (i.e., high stress vs. low stress conditions). The remaining 34 studies had either no control group at all ( n = 25), used intrasubject control (e.g., consecutive conditions; n = 5), or had multiple conditions (e.g., happy mood; sad mood) without a neutral condition ( n = 5). Experimental control is a crucial component of the scientific method ( Bowling, 2009 ) that reduces the risk of bias arising from environmental influences. Moreover, two thirds of the studies did not control for any additional variables that might have confounded with EI to influence reactivity or recovery variables, such as personality, cognitive ability, or mental health. Considering TEI is widely acknowledged as a lower order personality trait ( Petrides et al., 2007 ), it is concerning that TEI studies do not routinely account for personality. Similarly, only two AEI studies controlled for cognitive ability, a closely linked construct to AEI ( Mayer et al., 2008 ). Acute stress responding can also be influenced by clinical symptomology. For example, individuals with depression ( Burke et al., 2005 ) or anxiety ( De Rooij et al., 2010 ), often show blunted stress reactivity, and impaired stress recovery, compared to controls. Levels of trait anxiety and depression were only accounted for in one study ( Mikolajczak et al., 2009 , study 2). It is difficult to clearly define the relationship between EI and stress responding when the effects of confounding influences are not controlled for. Although the incremental validity of EI in a wide range of criteria is promising ( Andrei et al., 2016 ; Miao et al., 2018 ), to further establish the contribution of EI toward outcomes, researchers should aim to include measurement of emotion-related constructs in EI studies. Differences in methodological robustness could help to explain conflicting findings identified in the review. For example, Mikolajczak et al. (2009 , study 3, which identified decreased reactivity) and Thomas et al. ( 2018 , which identified increased reactivity), used variants of the same stressful task (TSST), the same TEI measure (TEIQue), and stress measurement (cortisol secretion). However, unlike the latter study, the former employed a control group, and controlled for confounding variables.

Limitations of the Review

At the review level, publication bias emerged. Two unpublished theses of potential relevance could not be obtained despite attempts to contact the authors.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Over the last two decades, EI has been claimed to hold a pivotal role with regards to many intrapersonal and interpersonal adaptive life outcomes. A key hypothesis suggests that EI leads to those positive outcomes by acting as an acute stress buffer. The present systematic review provides a timely overview of the experimental literature concerning EI and acute stress reactivity and recovery, bringing together relevant work from a vast array of disciplines. The hypothesis was only partially supported by the results of the present review. Findings suggested that whether EI is useful under acute stress is highly dependent on the stress context, and how EI is measured. TEI was significantly associated with reduced stress reactivity in two contexts: sports-based stressors (e.g., a sports competition), and cognitive stressors (e.g., a memory task), but not others (psychosocial stress; emotive stimuli). Furthermore, relationships between EI and self-reported stress generally occurred more often than with physiological stress (a more reliable index of reactivity). It was also unclear whether AEI, a more objective index of emotional skill, was adaptive, since relatively few studies measured this construct, and some indicated a deleterious effect of AEI. However, while emotionally intelligent individuals may or may not react more strongly to a stressor, they do seem to recover more quickly from the ordeal, regardless of how EI or stress is measured.

The review also identified some core limitations, which researchers should attempt to address in future studies. First, research concerning EI and reactivity should strive for experimental rigor. While some high quality studies (e.g., Mikolajczak et al., 2009 , study 3) used effective stress manipulations (with appropriate controls), controlled for confounding constructs, and considered multiple indices of reactivity, these were scarce. Second, it would be beneficial for the field for more studies to examine the contribution of both actual emotional skills (AEI) in addition to trait emotional self-efficacy (TEI). Importantly, it is also not possible to generalize findings to other populations (e.g., adolescents), given that most study samples were restricted to University students. Considering the drive to train or improve EI in children and young people, a third recommendation would be for future studies to examine the relationship between EI and stress reactivity in those populations. Alternatively, a novel approach would be to utilize virtual reality technology, exploring the role of EI when responding to a wide range of naturalistic stimuli and scenarios, without the practical restraints of current laboratory-based research. Overall, the findings of the review call into question some central assumptions about the stress-buffering effect of EI, and suggest that EI may only be useful in certain circumstances.

Author Contributions

RL was the primary researcher of this study, responsible for collecting and analyzing the data, and writing the first draft of the paper. SD was responsible for analyzing data and editing the paper. BM and PQ were also responsible for editing the paper. All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the review.

The research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^ Database searching revealed another paper of interest ( Mikolajczak et al., 2007) . However, the data from that paper was also reported in Mikolajczak et al. (2009) Study 3. Thus, the latter paper was included in lieu.

* Agnoli, S., Pittarello, A., Hysenbelli, D., and Rubaltelli, E. (2015). “Give, but Give until it Hurts”: The modulatory role of trait emotional intelligence on the motivation to help. PLoS ONE 10:e0130704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130704

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

* Aminabadi, N., Adhami, Z., Oskouei, S. G., Najafpour, E., and Jamali, Z. (2013). Emotional intelligence subscales: are they correlated with child anxiety and behavior in the dental setting? J. Clin. Pediatr. Dentistr. 38, 61–66. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.38.1.k754h164m3210764

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

* Aminabadi, N., Erfanparast, L., Adhami, Z. E., Maljaii, E., Ranjbar, F., and Jamali, Z. (2011). The impact of emotional intelligence and intelligence quotient (IQ) on child anxiety and behaviour in the dental setting. Acta Odontol. Scand. 69, 292–298. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2011.568959

Andrei, F., Siegling, A. B., Aloe, A. M., Baldaro, B., and Petrides, K. V. (2016). The incremental validity of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pers. Assess. 98, 261–276. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2015.1084630

Andrews, J., Ali, N., and Pruessner, J. C. (2013). Reflections on the interaction of psychogenic stress systems in humans: the stress coherence/compensation model. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 947–961. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.02.010

Armijo-Olivo, S., Stiles, C. R., Hagen, N. A., Biondo, P. D., and Cummings, G. G. (2012). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 18, 12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text

* Arora, S., Russ, S., Petrides, K. V., Sirimanna, P., Aggarwal, R., and Sevdalis, N. (2011). Emotional intelligence and stress in medical students performing surgical tasks. Acad. Med. 86, 1311–1317. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822bd7aa

Arora, S., Sevdalis, N., Nestel, D., Woloshynowych, M., Darzi, A., and Kneebone, R. (2010). The impact of stress on surgical performance: a systematic review of the literature. Surgery 147, 318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.007

Austin, E. J., Saklofske, D. H., and Mastoras, S. M. (2010). Emotional intelligence, coping and exam-related stress in Canadian undergraduate students. Aust. J. Psychol. 62, 42–50. doi: 10.1080/00049530903312899

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-effiacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bar-On, R., and Parker, J. D. A. (2000). The Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version (EQ-i:YV) Technical Manual . Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.

Baumann, N., and Turpin, J. C. (2010). Neurochemistry of stress. an overview. Neurochem. Res. 35, 1875–1879. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0298-9

* Bechtoldt, M. N., and Schneider, V. K. (2016). Predicting stress from the ability to eavesdrop on feelings: emotional intelligence and testosterone jointly predict cortisol reactivity. Emotion 16, 815–825. doi: 10.1037/emo0000134

Bowling, A. (2009). Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and Health Services . Berkshire: Open University Press.

Google Scholar

Brackett, M., Rivers, M., and Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 5, 88–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00334.x

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., and Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: a comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 780–795. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

Brannick, M. T., Wahi, M. M., Arce, M., Johnson, H. A., Nazian, S., and Goldin, S. B. (2009). Comparison of trait and ability measures of emotional intelligence in medical students. Med. Educ. 43, 1062–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03430.x

Burke, H. M., Davis, M. C., Otte, C., and Mohr, D. C. (2005). Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30, 846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.010

Campbell, J., and Ehlert, U. (2012). Acute psychosocial stress: Does the emotional stress response correspond with physiological responses? Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 1111–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.010

Cha, C., and Nock, M. (2009). Emotional intelligence is a protective factor for suicidal behaviour. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 48, 422–430. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f44

Chida, Y., and Hamer, M. (2008). Chronic psychosocial factors and acute physiological responses to laboratory-induced stress in healthy populations: a quantitative review of 30 years of investigations. Psychol. Bull. 134, 829–885. doi: 10.1037/a0013342

Chida, Y., and Steptoe, A. (2010). Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status: a meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Hypertension 55, 1026–1032. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146621

Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. P., and Anderson, S. (2002). Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Pers. Individ. Dif. 32, 197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00012-5

* Ciarrochi, J. V., Chan, A. Y. C., and Bajgar, J. (2001). Measuring emotional intelligence in adolescents. Pers. Individ. Dif. 31, 1105–1119. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00207-5

* Davis, S. K. (2018). Emotional intelligence and attentional bias for threat-related emotion under stress. Scand. J. Psychol. 59, 328–339. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12439

Davis, S. K., and Humphrey, N. (2012). The influence of emotional intelligence (EI) on coping and mental health in adolescence: divergent roles for trait and ability EI. J. Adolesc. 35, 1369–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.05.007

Davis, S. K., and Humphrey, N. (2014). Ability versus trait emotional intelligence. J. Indiv. Dif. 35, 54–62. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000127

Davis, S. K., and Nichols, R. (2018). Does emotional intelligence have a “dark” side? A review of the literature. Front. Psychol. 7:1316. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01316

Day, A. L., and Carroll, S. A. (2008). Faking emotional intelligence (EI): comparing response distortion on ability and trait-based EI measures. J. Organ. Behav. 29, 761–784. doi: 10.1002/job.485

Day, A. L., Therrien, D. L., and Carroll, S. A. (2005). Predicting psychological health: assessing the incremental validity of emotional intelligence beyond personality, type a behaviour, and daily hassles. Eur. J. Pers. 19, 519–536. doi: 10.1002/per.552

De Rooij, S. R., Schene, A. H., Phillips, D. I., and Roseboom, T. J. (2010). Depression and anxiety: associations with biological and perceived stress reactivity to a psychosocial stress protocol in a middle-aged population. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 866–877. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.011

Denson, T. F., Spanovic, M., and Miller, N. (2009). Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: a meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions. Psychol. Bull. 135, 823–853. doi: 10.1037/a0016909

Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) (1998). Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies . Available online at: https://merst.ca/ephpp/ (accessed December 1, 2018).

Extremera, N., Durán, A., and Rey, L. (2007). Perceived emotional intelligence and dispositional optimism-pessimism: analyzing their role in predicting psychological adjustment among adolescents. Pers. Individ. Dif. 42, 1069–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.014

* Fallon, C. K., Panganiban, A. R., Wohleber, R., Matthews, G., Kustubayeva, A. M., and Roberts, R. (2014). Emotional intelligence, cognitive ability and information search in tactical decision making. Pers. Individ. Dif. 65, 24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.029

* Fellner, A. N., Matthews, G., Shockley, K. D., Warm, J. S., Zeidner, M., Karlov, L., et al. (2012). Using emotional cues in a discrimination learning task: effects of trait emotional intelligence and affective state. J. Res. Pers. 46, 239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.004

Feltz, D. L., Short, S. E., and Sullivan, P. J. (2008). Self-Efficacy in Sport . Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

* Fernández-Berrocal, P., and Extremera, N. (2006). Emotional intelligence and emotional reactivity and recovery in laboratory context. Psiotherma 18, 72–78.

PubMed Abstract

Fiori, M. (2009). A new look at emotional intelligence: a dual-process framework. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 13, 21–44. doi: 10.1177/1088868308326909

Föhr, T., Talvonen, A., Myllymäki, T., Järvelä-Reijonen, E., Rantala, S., Korpela, R., et al. (2015). Subjective stress, objective heart rate variability-based stress, and recovery on workdays among overweight and psychologically distressed individuals: a cross-sectional study. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 10:39. doi: 10.1186/s12995-015-0081-6

Freudenthaler, H. H., and Neubauer, A. C. (2005). Emotional intelligence: the convergent and discriminant validities of intra- and interpersonal emotional abilities. Pers. Individ. Dif. 39, 569–579. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.004

Geurts, S. A., and Sonnentag, S. (2006). Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 32, 482–492. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1053

* Gohm, C. L. (2003). Mood regulation and emotional intelligence: individual differences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 594–607. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.594

Harms, P. D., and Credé, M. (2010). Emotional intelligence and transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analysis. J. Leadership Organ. Stud. 17, 5–17. doi: 10.1177/1548051809350894

Henze, G. I., Zänkert, S., Urschler, D. F., Hiltl, T. J., Kudielka, B. M., Pruessner, J. C., et al. (2017). Testing the ecological validity of the Trier Social Stress Test: association with real-life exam stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 75, 52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.002

Heopniemi, T., Elovainio, M., Pulkki, L., Puttonen, S., Raitakari, O., and Keltikangas-Jarvinen, L. (2007). Cardiac autonomic reactivity and recovery in predicting carotid atherosclerosis: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Health Psychol. 26, 13–21. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.13

CrossRef Full Text

Hu, M., Lamers, F., de Geus, E., and Penninx, B. (2016). Differential autonomic nervous system reactivity in depression and anxiety during stress depending on type of stressor. Psychosom. Med. 78, 562–572. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000313

Keefer, K. V., Saklofske, D. H., and Parker, J. D. A. (2018). “Emotional intelligence, stress, and health: when the going gets tough, the tough turns to emotions,” in An Introduction to Emotional Intelligence. eds L. Dacre Pool, and P. Qualter (Sussex: Wiley), 161–184. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-90633-1

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M., and Hellhammer, D. H. (1993). The ‘Trier Social Stress Test': a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28, 76–81.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Krkovic, K., Clamor, A., and Lincoln, T. M. (2018). Emotion regulation as a predictor of the endocrine, autonomic, affective, and symptomatic stress response and recovery. Psychoneuroendocrinology 94, 112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.028

Kuhlmann, S., Piel, M., and Wolf, O. T. (2005). Impaired memory retrieval after psychosocial stress in healthy young men. J. Neurosci. 25, 2977–2982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5139-04.2005

* Laborde, S., Brüll, A., Weber, J., and Anders, L. S. (2011). Trait emotional intelligence in sports: a protective role against stress through heart rate variability? Pers. Individ. Dif. 51, 23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.003

* Laborde, S., Dosseville, F., and Scelles, N. (2010). Trait emotional intelligence and preference for intuition and deliberation: respective influence on academic performance. Pers. Individ. Dif. 49, 784–788. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.031

* Laborde, S., Lautenbach, F., Allen, M. S., Herbert, C., and Achtzehn, S. (2014). The role of trait emotional intelligence in emotion regulation and performance under pressure. Pers. Individ. Dif. 57, 43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.013

Lanciano, T., Curci, A., and Zatton, E. (2010). Why do some people ruminate more or less than others? The role of emotional intelligence ability. Eur. J. Psychol. 6, 65–84. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v6i2.185

* Lane, A. M., Devonport, T. J., Soos, I., Karsai, I., Leibinger, E., and Hamar, P. (2010). Emotional intelligence and emotions associated with optimal and dysfunctional athletic performance. J. Sports Sci. Med. 9, 388–392.

* Lane, A. M., Thelwell, R., and Devonport, T. J. (2009). Emotional intelligence and mood states associated with optimal performance. E J. Appl. Psychol. 5, 67–73. doi: 10.7790/ejap.v5i1.123

* Lane, A. M., and Wilson, M. (2011). Emotions and trait emotional intelligence among ulta-endurance runners. J. Sci. Med. Sport 14, 358–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.03.001

Lea, R. G., Qualter, P., Davis, S., Pérez-González, J. C., and Bangee, M. (2018). Trait emotional intelligence and attentional bias for positive emotion: an eye-tracking study. Pers. Individ. Dif. 128, 88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.017

LeBlanc, V. R. (2009). The effects of acute stress on performance: Implications for health professions education. Acad. Med. 84, 25–33. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b37b8f

LeMoult, J., Arditte, K. A., D'Avanzato, C., and Joorman, J. (2013). State rumination: associations with emotional stress reactivity and attention biases. J. Exp. Psychopathol. 4, 471–484. doi: 10.5127/jep.029112

* Limonero, J. T., Fernández-Castro, J., Soler-Oritja, J., and Álvarez-Moleiro, M. (2015). Emotional intelligence and recovering from induced negative emotional state. Front. Psychol. 6:816. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00816

Linden, W., Earle, T. L., Gerin, W., and Christenfeld, N. (1997). Physiological stress reactivity and recovery: conceptual siblings separated at birth? J. Psychosom. Res. 42, 117–135. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00240-1

* Ling, S., Raine, A., Gao, Y., and Schug, R. (2018). The mediating role of emotional intelligence on the autonomic functioning - psychopathy relationship. Biol. Psychol. 136, 136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.05.012

Lopez-Duran, N. L., McGinnis, E., Kuhlman, K., Geiss, E., Vargas, I., and Mayer, S. (2015). HPA-axis stress reactivity in youth depression: evidence of impaired regulatory processes in depressed boys. Stress 15, 545–553. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2015.1053455

MacCann, C., and Roberts, R. D. (2008). New paradigms for assessing emotional intelligence: theory and data. Emotion 8, 540–551. doi: 10.1037/a0012746

Maier, K. J., Waldstein, S. R., and Synowski, S. J. (2003). Relation of cognitive appraisal to cardiovascular reactivity, affect, and task engagement. Ann. Behav. Med. 26, 32–41. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_05

Martins, A., Ramalho, N. C., and Morin, E. M. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Pers. Individ. Dif. 49, 554–564. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.029

* Matthews, G., Emo, A. K., Funke, G., Zeidner, M., Roberts, R., Costa, P. T., et al. (2006). Emotional intelligence, personality and task-induced stress. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 12, 96–107. doi: 10.1037/1076-898X.12.2.96

* Matthews, G., Pérez-González, J. C., Fellner, A. N., Funke, G., Emo, A. K., Zeidner, M., et al. (2015). Individual differences in facial emotion processing: trait emotional intelligence, cognitive ability, or transient stress? J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 33, 68–82. doi: 10.1177/0734282914550386

Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., and Roberts, R. (2017). “Emotional intelligence, health, and stress,” in The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice. eds C. L. Cooper and J. C. Quick (Sussex: Wiley), 312–326. doi: 10.1002/9781118993811.ch18

Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., and Roberts, R. D. (2007). “Measuring emotional intelligence: promises, pitfalls, solutions?,” in Handbook of Methods in Positive Psychology. eds A. D. Ong and M. Van Dulmen (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 189–204.

Matthews, K. A., Katholi, C. R., McCreath, H., Whooley, M. A., Williams, D. R., Zhu, S., et al. (2004). Blood pressure reactivity to psychological stress predicts hypertension in the CARDIA study. Circulation 110, 74–78. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133415.37578.E4

Mayer, J., Roberts, R., and Barsade, S. (2008). Human abilities: emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59, 507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., and Caruso, D. R. (2002). Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) User's Manual . Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems.

McEwen, B. S. (2006). Stress, adaptation and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 840, 33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05830.x

McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic Stress 1. doi: 10.1177/2470547017692328

Miao, C., Humphrey, R., and Shanshan, Q. (2018). A cross-cultural meta-analysis of how leader emotional intelligence influences subordinate task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. J. World Business 53, 463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2018.01.003

Mikolajczak, M., and Luminet, O. (2008). Trait emotional intelligence and the cognitive appraisal of stressful events: an exploratory study. Pers. Individ. Dif. 44, 1445–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.12.012

Mikolajczak, M., Luminet, O., and Menil, C. (2006). Predicting resistance to stress: incremental validity of trait emotional intelligence over alexithymia and optimism. Psiotherma 18, 79–88.

* Mikolajczak, M., Petrides, K. V., Coumans, N., and Luminet, O. (2009). The moderating effect of trait emotional intelligence on mood deterioration following laboratory-induced stress. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 9, 455–477. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-16945-007

Mikolajczak, M., Roy, E., Luminet, O., Fillée, C., and de Timary, P. (2007). The moderating impact of emotional intelligence on free cortisol responses to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, 1000–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.009

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Inter. Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Nater, U. M., Okere, U., Stallkamp, R., Moor, C., Ehlert, U., and Kliegel, M. (2006). Psychosocial stress enhances time-based prospective memory in healthy young men. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 86, 344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.04.006

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., Dupuis, P., et al. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion 11, 354–366. doi: 10.1037/a0021554

* O'Connor, P., Nguyen, J., and Anglim, J. (2016). Effectively coping with task stress: a study of the validity of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire- short form (TEIQue-SF). J. Pers. Assess. 99, 304–314. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2016.1226175

O'Donnell, K., Brydon, L., Wright, C. E., and Steptoe, A. (2008). Self-esteem levels and cardiovascular and inflammatory responses to acute stress. Brain Behav. Immun. 22, 1241–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.012

Oldehinkel, A. J., Ormel, J., Bosch, N. M., Bouma, E. M. C., Van Roon, A. M., Rosmalen, J. G. M., et al. (2011). Stressed out? Associations between perceived and physiological stress responses in adolescents: the TRAILS study. Psychophysiology 48, 441–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01118.x

Palmer, B., Walls, M., Burgess, Z., and Stough, C. (2001). Emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Leadership Organ. Dev. J. 22, 5–10. doi: 10.1108/01437730110380174