How It Feels to Be Colored Me, by Zora Neale Hurston

"I remember the very day that I became colored"

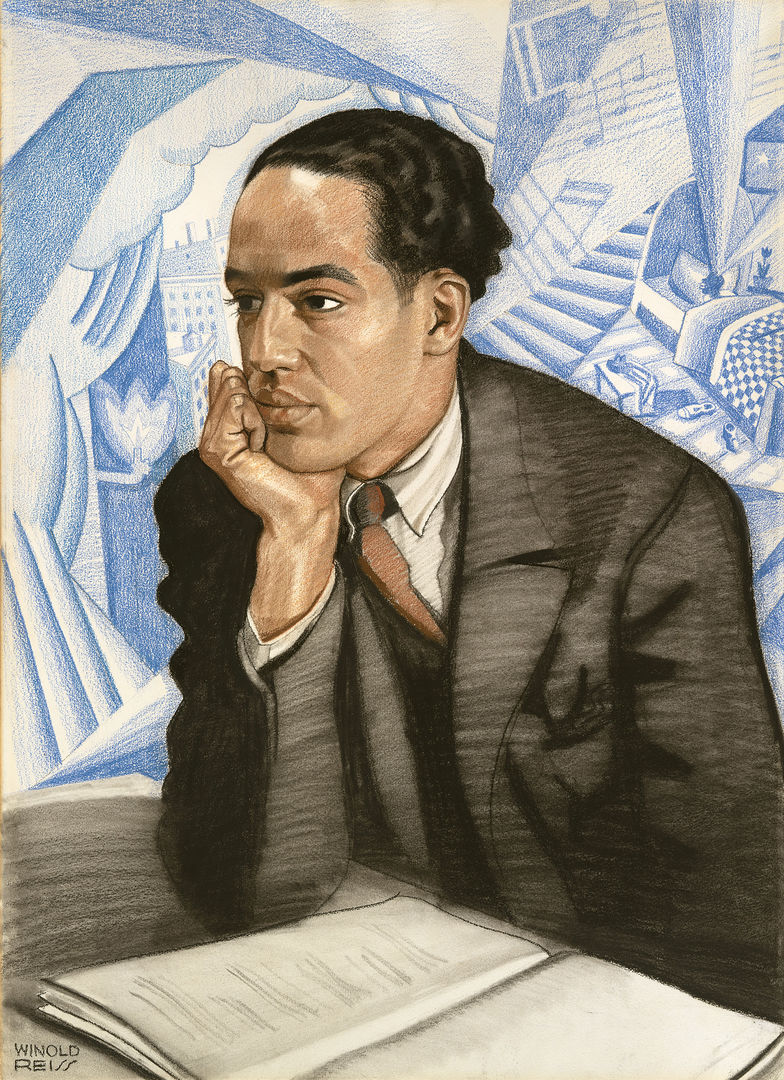

PhotoQuest/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Zora Neal Hurston was a widely-acclaimed Black author of the early 1900s.

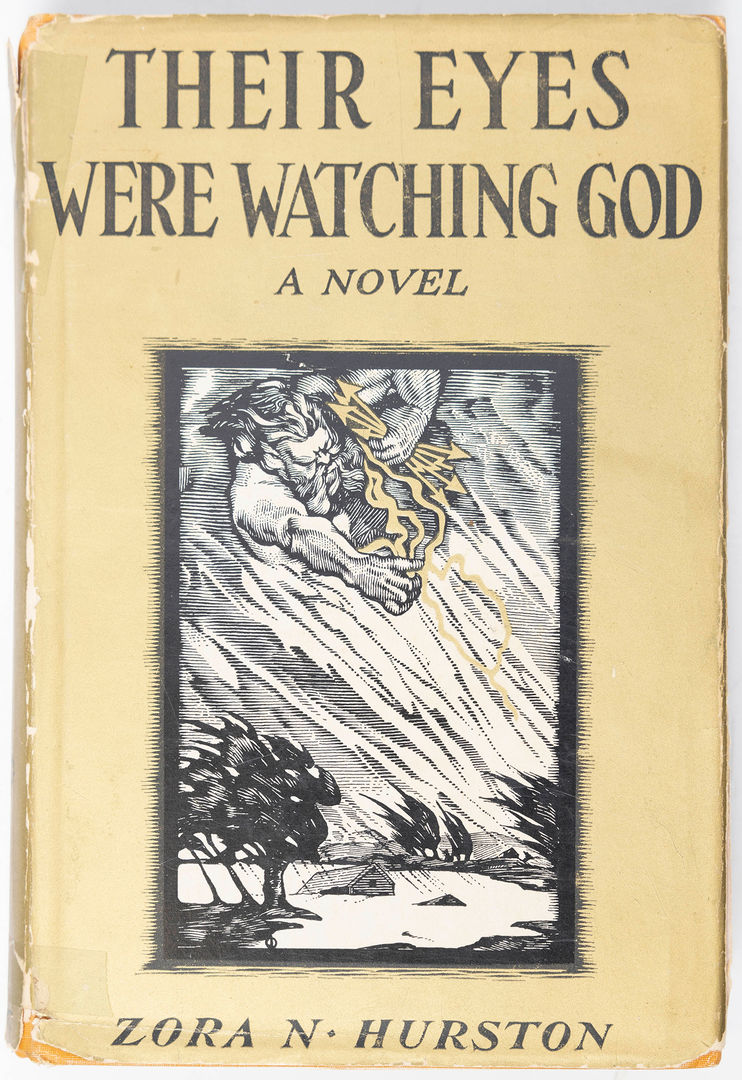

"A genius of the South, novelist, folklorist, anthropologist"—those are the words that Alice Walker had inscribed on the tombstone of Zora Neale Hurston. In this personal essay (first published in The World Tomorrow , May 1928), the acclaimed author of Their Eyes Were Watching God explores her own sense of identity through a series of memorable examples and striking metaphors . As Sharon L. Jones has observed, "Hurston's essay challenges the reader to consider race and ethnicity as fluid, evolving, and dynamic rather than static and unchanging"

- Critical Companion to Zora Neale Hurston , 2009

How It Feels to Be Colored Me

by Zora Neale Hurston

1 I am colored but I offer nothing in the way of extenuating circumstances except the fact that I am the only Negro in the United States whose grandfather on the mother's side was not an Indian chief.

2 I remember the very day that I became colored. Up to my thirteenth year I lived in the little Negro town of Eatonville, Florida. It is exclusively a colored town. The only white people I knew passed through the town going to or coming from Orlando. The native whites rode dusty horses, the Northern tourists chugged down the sandy village road in automobiles. The town knew the Southerners and never stopped cane chewing when they passed. But the Northerners were something else again. They were peered at cautiously from behind curtains by the timid. The more venturesome would come out on the porch to watch them go past and got just as much pleasure out of the tourists as the tourists got out of the village.

3 The front porch might seem a daring place for the rest of the town, but it was a gallery seat for me. My favorite place was atop the gatepost. Proscenium box for a born first-nighter. Not only did I enjoy the show, but I didn't mind the actors knowing that I liked it. I usually spoke to them in passing. I'd wave at them and when they returned my salute, I would say something like this: "Howdy-do-well-I-thank-you-where-you-goin'?" Usually, automobile or the horse paused at this, and after a queer exchange of compliments, I would probably "go a piece of the way" with them, as we say in farthest Florida. If one of my family happened to come to the front in time to see me, of course, negotiations would be rudely broken off. But even so, it is clear that I was the first "welcome-to-our-state" Floridian, and I hope the Miami Chamber of Commerce will please take notice.

4 During this period, white people differed from colored to me only in that they rode through town and never lived there. They liked to hear me "speak pieces" and sing and wanted to see me dance the parse-me-la, and gave me generously of their small silver for doing these things, which seemed strange to me for I wanted to do them so much that I needed bribing to stop, only they didn't know it. The colored people gave no dimes. They deplored any joyful tendencies in me, but I was their Zora nevertheless. I belonged to them, to the nearby hotels, to the county—everybody's Zora.

5 But changes came in the family when I was thirteen, and I was sent to school in Jacksonville. I left Eatonville, the town of the oleanders, a Zora. When I disembarked from the riverboat at Jacksonville, she was no more. It seemed that I had suffered a sea change. I was not Zora of Orange County anymore, I was now a little colored girl. I found it out in certain ways. In my heart as well as in the mirror, I became a fast brown—warranted not to rub nor run.

6 But I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not mind at all. I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all but about it. Even in the helter-skelter skirmish that is my life, I have seen that the world is to the strong regardless of a little pigmentation more of less. No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.

7 Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the granddaughter of slaves. It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you. The terrible struggle that made me an American out of a potential slave said "On the line!" The Reconstruction said "Get set!" and the generation before said "Go!" I am off to a flying start and I must not halt in the stretch to look behind and weep. Slavery is the price I paid for civilization, and the choice was not with me. It is a bully adventure and worth all that I have paid through my ancestors for it. No one on earth ever had a greater chance for glory. The world to be won and nothing to be lost. It is thrilling to think—to know that for any act of mine, I shall get twice as much praise or twice as much blame. It is quite exciting to hold the center of the national stage, with the spectators not knowing whether to laugh or to weep.

8 The position of my white neighbor is much more difficult. No brown specter pulls up a chair beside me when I sit down to eat. No dark ghost thrusts its leg against mine in bed. The game of keeping what one has is never so exciting as the game of getting.

9 I do not always feel colored. Even now I often achieve the unconscious Zora of Eatonville before the Hegira. I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.

10 For instance at Barnard. "Beside the waters of the Hudson" I feel my race. Among the thousand white persons, I am a dark rock surged upon, and overswept, but through it all, I remain myself. When covered by the waters, I am; and the ebb but reveals me again.

11 Sometimes it is the other way around. A white person is set down in our midst, but the contrast is just as sharp for me. For instance, when I sit in the drafty basement that is The New World Cabaret with a white person, my color comes. We enter chatting about any little nothing that we have in common and are seated by the jazz waiters. In the abrupt way that jazz orchestras have, this one plunges into a number. It loses no time in circumlocutions , but gets right down to business. It constricts the thorax and splits the heart with its tempo and narcotic harmonies. This orchestra grows rambunctious, rears on its hind legs and attacks the tonal veil with primitive fury, rending it, clawing it until it breaks through to the jungle beyond. I follow those heathen—follow them exultingly. I dance wildly inside myself; I yell within, I whoop; I shake my assegai above my head, I hurl it true to the mark yeeeeooww! I am in the jungle and living in the jungle way. My face is painted red and yellow and my body is painted blue. My pulse is throbbing like a war drum. I want to slaughter something—give pain, give death to what, I do not know. But the piece ends. The men of the orchestra wipe their lips and rest their fingers. I creep back slowly to the veneer we call civilization with the last tone and find the white friend sitting motionless in his seat, smoking calmly.

12 "Good music they have here," he remarks, drumming the table with his fingertips.

13 Music. The great blobs of purple and red emotion have not touched him. He has only heard what I felt. He is far away and I see him but dimly across the ocean and the continent that have fallen between us. He is so pale with his whiteness then and I am so colored.

14 At certain times I have no race, I am me. When I set my hat at a certain angle and saunter down Seventh Avenue, Harlem City, feeling as snooty as the lions in front of the Forty-Second Street Library, for instance. So far as my feelings are concerned, Peggy Hopkins Joyce on the Boule Mich with her gorgeous raiment, stately carriage, knees knocking together in a most aristocratic manner, has nothing on me. The cosmic Zora emerges. I belong to no race nor time. I am the eternal feminine with its string of beads.

15 I have no separate feeling about being an American citizen and colored. I am merely a fragment of the Great Soul that surges within the boundaries. My country, right or wrong.

16 Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It's beyond me.

17 But in the main, I feel like a brown bag of miscellany propped against a wall. Against a wall in company with other bags, white, red and yellow. Pour out the contents, and there is discovered a jumble of small things priceless and worthless. A first-water diamond, an empty spool, bits of broken glass, lengths of string, a key to a door long since crumbled away, a rusty knife-blade, old shoes saved for a road that never was and never will be, a nail bent under the weight of things too heavy for any nail, a dried flower or two still a little fragrant. In your hand is the brown bag. On the ground before you is the jumble it held—so much like the jumble in the bags, could they be emptied, that all might be dumped in a single heap and the bags refilled without altering the content of any greatly. A bit of colored glass more or less would not matter. Perhaps that is how the Great Stuffer of Bags filled them in the first place—who knows?

- 35 Zora Neale Hurston Quotes

- Zora Neale Hurston

- Definition and Examples of Transitional Paragraphs

- How to Apologize: Say "I'm Sorry" With Quotes

- Harlem Renaissance Women

- How to Define Autobiography

- Men of the Harlem Renaissance

- Five African American Women Writers

- Twelve Reasons I Love and Hate Being a Principal of a School

- 'Much Ado About Nothing' Quotes

- Audre Lorde Quotes

- Frozen Vegetables Spark in the Microwave

- The ABCs of Teaching: Affirmations for Teachers

- 6 Revealing Autobiographies by African American Thinkers

- Cicely Tyson Quotes

- 5 Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

(92) 336 3216666

- How It Feels To Be Colored Me

Background of the Essay

The essay ‘How It Feels To Be Colored Me’ was written in 1928 by an American writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston. It aims at highlighting the life of Afro-American black women in the 1920s. The skopos of the essay is not merely a black audience but also white men living in America. This way she shares her experience of being black and treated prejudice.

Financially Hurston was quite wealthy and lived a prosperous life because of her father’s high rank in the society. Most of her years were spent with Black people where she was treated respectfully because of her socially elite status.

After her mother’s death, she was forced to live in the White community. Here she received some cultural, emotional and racial shocks. She was not welcomed here and this motivated her to write the essay ‘How it feels to be colored me’. She has expressed her experiences, emotions and viewpoints in the form of metaphoric or literary language. She has used anecdotes, imagery and other figurative devices. As an anthropologist, she has shown grip on societal trends, norms and discourse. As an active supporter of the Black community, she also participated in Harlem Renaissance.

How It Feels To Be Colored Me Summary

The essay opens by explaining the word ‘colored’ or Afro-American. The author calls herself unique among others and makes no excuse to hide her racial identity. She is determined not to exchange her black identity with Native American whiteness just like other people of her race. She reminds the day of her life when she is made to feel colored. Before then she grew within a black community in a village of Eatonville, Florida.

Everyone around her was black like her and only white people she had encountered were those passersby to Orlando. Local townspeople usually rode horses and tourists from the Northern area used cars very often. And the residents of Eatonville did not bother white people who came from the Southern area and they kept on doing whatever they were i.e. chewing cane. But they were very much concerned with people coming from the North. They came out on the porch of their houses to watch them.

It was Hurston who boldly went farther and sat outside the house near the gatepost to speak with passers-by. She usually used to say “Howdy-do-well-I-thank-you-where-you-goin’?” If any of them stopped, she walked with him a bit farther in the street. Here Hurston writes, if any of her family members noticed what she was doing, she would surely be stopped from doing that. But she couldn’t stop greeting white tourists and being the first to welcome them.

Hurston mentioned in the essay, at that time, she was aware of the only difference between white and black and that was white people do not live in their town and they paid her for singing, dancing and reciting. It was an amazing thing for her because she was not paid for these activities in her town. Only white people used to do it to her. Even her family disliked her performances yet they proclaimed her as “their Zora … everybody’s Zora.”

Life was plain until she reached the age of 13. Due to family issues, she was sent to a boarding school in Jacksonville, Florida. As she left the town, she was no more Zora but a little colored girl.

From this point forward, Hurston describes the present view where she is being discriminated against because of her skin color. But she rejects this negativity that nature has made a dirty deal with negroes. Though she has to face hard times but her determination regardless of any race and color lets her not get upset. Instead, she spends her time sharpening knives for oyster.

She protests why everyone reminds her of servitude which is a past event. Both white and black are trying to heal from that incident. It is like feeling a medical patient and recovering gradually from surgery. She wishes to run ahead instead of clinging to the past. Being enslaved was not her choice and she has a world open to gain. Bullying adventures of white people gain her a lot of attention. For her, it was not the black people but the white who are to sympathize. They are trying to get hold of things they already have. It is less fun and adventure than having them in the first place.

Hurston often recalls her time in Eatonville. However, she sometimes finds herself in the backdrop due to her color especially when there is a white person. When she attends college at Barnard, she notices that she is like a rock among the white sea foam covered with sea surge. She is there until the water retreats the surge and lets her visible again.

Hurston also feels her social superiority when a white person leads her to a black people community. She gives an example of her social importance when she went to a music club in Harlem accompanied by her white friend. She describes when the jazz music was played, it affected her whole body and she started swaying and dancing like an animal. Music awakened wilderness in her and she felt like holding a spear and wearing tribal paints. She was joyfully crazy and terribly wished to kill someone.

But the song ended and bewildered feelings left slowly. She then turns towards her white friend who only praises the music without being touched with the emotions that she was gripped in a moment earlier. She realizes a gap between them and “He is so pale with his whiteness then and I am so colored.”

Hurston does not find conflict between her Americanness and Darkness. She considers herself as part of the country. She sees discrimination with surprise and not with rancor.

Besides everything, Hurston compares herself with a sack filled with bits and bobs and that she is just a sack among sacks of various colors. Each sack contains both marvelous and ordinary things from diamond to broken glass pieces. If someone dumps her out in a big pile, there would be many priceless bags. They can be exchanged but stuffing will remain similar. She muses rhetorically that the Great Stuffer (God) might have stuffed them at first place just like that.

How It Feels To Be Colored Me Characters Analysis

Zora hurston.

The author paints herself in the essay as a character and gives an account of different shades of her life. Hurston is proud of her color and race. She feels free to acclaim her Negrotudness. She wears blackness as a badge and analyzes her views. She sets the tone for other Black people to feel proud of themselves.

Enlightened Zora

Zora sprites in a new purified form when she realizes her identity is acceptable in her community and she is treated like a celebrity and worthy of praise. She feels all her pains are being rewarded now. She feels beautiful and ‘Colored’ among white pale people.

Floridian white folks

These are the people of Jacksonville, Florida. When Hurston moved into this place, her neighborhood houses were inhabited with white folk. They did watch her as a scornful object. The environment was filled with tension and hatred. She felt being treated like an animal in a circus who is an object of amusement and to whom they treat down to earth.

Black people

Two groups of the Black community are described in this essay. First one is a socially and financially powerful group that is proud of their tradition and race. She met them in Harlem where best African music sprites up representing Black people emotions. Then there is another sort of black person who wants to adjust himself in the wave of the White folk cultural stream. Hurston criticizes them for hiding their identity and ethnicity. in with the mainstream culture that the White folks create.

Themes in How It Feels To Be Colored Me

Pride in african-american heritage.

Hurston, the anthropologist, opens up her essay, “How It Feels To Be Colored me” with the clear acknowledgement that She is an African American by race. She admits and feels proud to be black and an African American. She says that it does not bother her all. She feels OK with it.

As the essay proceeds, she elaborates, those ways of racism that have informed her erroneously about her identity. In her surroundings, she is called a little Colored girl instead of being a little lass. In her teenage, she does not know that race is such a thing, people care about it. When she moves to Jacksonville, she encounters the harsh truth. As they began to grow in Jacksonville, she was made to feel abashed for her culture, race and heritage. Through her essay, she attempts to overthrow the feelings of guilt and shame that emerge because of blackness.

Judgement and Prejudice

Judgement and prejudice are one of the central thoughts in Hurston’s essay. The strange conflicting energy, present in the essay, defines it. She informs her readers that in her essay she is answering to the unuttered prejudice. She has not written this essay to express her feelings or what her life is like.

Though she, more or less, gives her thoughts to these two subjects, what she actually does, in the essay, is to drag back her readers into the belief system. She made her readers witness that the prejudice against black people emerges from their belief system. She grieves over the fact that white people do not celebrate the white culture. She speaks for the beauty of her culture and heritage. She argues that still white people still despise the black culture. Even today, white people scorn black culture and heritage.

Identity and Race

The author foretells that the white think that black people are preoccupied with the thought they are black and it makes them feel that they are inferior and they are ashamed of their culture and heritage. Being an African American writer, she says that case is not so. The white people have access to power relations and they set everything in society. Through religion, education, morality, economic system and laws, they oppress the black race.

When the missionaries came to their land, they had religion and the native people had wealth. Missionaries taught them how to pray with closed eyes. When they opened their eyes, missionaries got hold of their wealth and the natives had religion. This is how the system of beliefs works. Religion is a tool to use to get targeted goals. The author does not even think about race in her daydreams. She dreams of getting famous. She makes it clear that race is not a significant thing about a person. Those who think it’s an important thing, they are requested to reevaluate their relationship to racism.

Abandonment of Racism

Abandonment of racism is another important theme of Zora’s essay. She emphatically writes in her essay that she does not have any negative feelings about racism. She feels perfectly fine with it. She clearly and simply writes that she doesn’t mind it at all. She rejects negativity with stress because she thinks people believe it exists. It can be her attempt to keep herself positive when the whole world is on the negative side.

Nora’s idea of rejecting racism stretches out to her owl black people. In the very beginning of her essay, she makes fun of those African American who claim that they belong to Indian chiefs. She rather believes that we should feel proud of what we are in fact.

Later on, in her essay, she pokes fun on the sobbing schools of Negrohood who make them feel inferior. Such schools make them able to look down to themselves. In this regard, African Americans need to unlearn what they have been taught at schools. Such statements show that including her own black people, she condemns all those who believe that the African blood can make the people inferior and lowly. Nora Hurston rejects this idea of racism and she believes that Africans are as good as the people of other races.

Denial of Pain

Denial of pain is another significant theme of Hurston’s essay “How it Feels to be Colored me.” She writes down painful historical and personal events in her essay but her focus is on being positive and happy. She does not permit negativity to overcome her. She tells her childhood details in full three passages. In an only paragraph, she talks about her transformation into the little colored girl. She spends more time describing her childhood happiness.

In the passage, where she gives her transformational details, she does not tell exactly what had happened to her. She says that she had found it out in certain ways. Her pains are unexpressed. She permits her readers to imagine the pain she had endured. She delicately passes through and does not pay any heed to those racists who have hurt her. She has had harsh experiences in her life, but she neither names nor describes those racists. Hurston loves to turn the spotlight on herself. She keeps herself in the story and refuses to accept negativity for her.

With great displeasure and annoyance, Hurston discusses slavery. She says, such people are in abundance around her, who continuously reminds her that she is the granddaughter of slaves. But this fails to get her depressed.

Perhaps, she willingly refuses to feel the pangs of slavery because she does not want history to do this to her. Her focus is on life that moves forward. She does not want to rub salt over injuries by peeping back into the harsh past. Again, she keeps her focus on herself. For the sake of civilization, she paid the price of slavery. In this adventure, she paid a huge price for her ancestors. Again the wrongdoers and those who enslaved others are completely absent from her essay.

Celebration of the (black) Self (Negritude)

Celebration of the self is another important theme in Hurston’s essay. Throughout her essay, she has been seen celebrating her black self. She accepts herself as she is in fact. While describing herself, she brings those qualities out, which are considered as flaws by other people.

For example, when she was talking about her childhood, she wanted other’s attention very much, she needed bribing to stop that performance. Her depiction of her childhood age suggests that she was arrogant and attention seeker. She embraces the aspects that other people criticize. She has learnt the art of celebrating herself. She used the word snooty for herself, which has negative associations. She accepts herself with all her flaws.

History and Opportunity

Nora Hurston wrote this essay in the 1920s. At that time, the United States of America was only sixty years away from the Civil War. The age of slavery was going to be ended. This account of experience is no doubt a legacy for African American culture. Hurston does this in her peculiar way.

In her essay, she acknowledges the racial discrimination against African-Americans. By this, she lessens the impact of slavery. Hurston is encouraged by the basic rights of the black race, which they sought by the 1920s. True equality was yet to be won. But whatever African-Americans have gained, was encouraging and strengthening. The way to attain equality is an opportunity for the African-Americans to end their unearned sufferings.

She considers her own time as an epoch of high adventure and celebrated endeavor. She, herself is the central character of all this.

Performance

In her essay, Hurston’s thoughts on race are tied up with creative performance. In her early age, she interacted with white people through singing and dancing. This was the time when she became the little colored girl. This interaction permits her to develop her creative performance. In this respect, her essay can be regarded as a story of an artist and it is also an essay about race. She had many shows in different places, which let her polish her performance.

How It Feels To Be Colored Me Literary Analysis

Nora Neale Hurston’s essay, “How It Feels to Be Colored me” is about race. She remains positive throughout her essay when she talks about her African-American identity and heritage. Some of the assumptions about race are unstated as well. These unstated assumptions complicate her claims about her experience as an African-American identity.

Interpretation of Title

Hurston’s essay innately has an unclear title. It is very significant but can easily be overlooked. The use of ‘colored’ in the essay’s title can possibly be interpreted in two different ways. In a first way, if it means how a person feels to be colored, then the readers can take it as a straightforward discussion about the author’s life. In which she is trying to discuss her African-American background. In another way, if the readers take this ‘colored’ as a part of a passive verb phrase, then it is about the views of others about the colored one being.

The second way of interpretation gives the authored image, which is dyed or painted by others. She herself does not have control over it because these are people’s perceptions and views about her. The title is ambiguous and throughout the essay, tension remains. On one side, the author presents herself strong, exuberant and an individual, who stays positive and happy and feels proud about her race, identity and heritage. She also faced racial discrimination and stereotypes but does not reveal.

Acceptance of Racial Identity

In the very first sentence of her essay, she has been seen accepting her racial status. In plain and simple language, she writes that she is a colored girl. It gives a gesture about her race which was thought to be well- mannered about her time. Apart from this clause of three simple words, the remaining sentence is very much complicated. The author denies providing extenuating circumstances. She uses strange and odd diction, which suggest that she might be expecting to apologize for her race and heritage. This strange diction tells other people to think that Hurston takes the race as something bad.

In the very start of her essay, Hurston writes that African- Americans claim that they are the descendants of Native Americans. But the author does not think that way. Even she has been seen making fun of all those African- Americans who think Native Americans as their ancestors. In her view, they attempt to make their connection to America in contrast to those white Americans, who landed there as colonists. According to her, some of the African-Americans have the blood of Native Americans but this is not so for all. She made a bold and unconventional comment. It shows her sharp wit and she seems perfectly OK to criticize her own race.

Biblical Allusion and Cultural & Historical Associations

Hurston calls her Eatonville, Florida a biblical Eden, where an African American child is brought up without the burdens of racism. She uses the metaphor of an audience who is there to see theatrical performances. She describes herself that she is in a proscenium box, which means she is close to the stage in contrast to Eatonville’s simple and timid people who hardly dare to speak to the white people who pass by them.

She witnesses the people there, who were chewing sugarcanes. Chewing sugarcane was a common activity in those days. And those people were found chewing sugarcane, where sugarcane grows in abundance. Moreover, white Americans have an association with those who chew sugarcane. They thought them the uneducated ones. She runs down to such ways of portraying African-Americans in her writings. Her contemporaries were of the view that she is enforcing stereotypes rather to challenge them.

She is willing to displease her reader, in the passages where she writes about slavery. She writes down that she always finds someone who reminds her that she is the granddaughter of slaves. She writes this as this unease is prejudiced and full of annoyance. She does not get bothered by slavery and its history. History does not bother her. Scars of her ancestor do not hurt her. Terrifying past events do not bring sadness to her. She does not allow history to make her feel worried.

Her focus is on herself. Her focus is on the present and future. Her focus is on staying positive. She shrugs off the sufferings and pains of other people and keeps herself focused on herself and her desires. When she writes about slavery, she cites reference to civilization. She allies this to the new American society. Then she compares this to the primitive culture. She also compares it to the imaginative African culture.

Childhood as a True Color

In the days of her childhood, Nora Hurston could not realize that she belongs to the black community. After her childhood, she came to know this when she saw white people looking at them like they were glancing at a zoo. This revealed to her that she is black. Her identity changed when she moved to Jacksonville, where white people were in abundance. At Jacksonville, they called her a little ‘colored’ girl. For this, the little ‘colored’ girl was treated badly harshly.

Before leaving Eatonville, Hurston suggests that she was what she meant to be. In the paragraph about her childhood, she describes herself as a lively, impudent girl with tons of curiosity. She summons herself ‘the first welcome to our state, Floridian. It suggests that it was she who developed the custom of being friendly to all out of state visitors. This statement suggests that Hurston is still lively, witty, impudent, a woman of charming personality, as she used to be in her childhood.

She finds her true self in her childhood self. She finds the real Hurston is her childhood. She feels proud to cherish those childhood days when she stepped outside to meet other people when people were afraid to approach them. She was very friendly to them now she appreciates her boldness. She feels eager to perform before the audience. She was so eager that she needed bribing to stop. She accepts herself with all her ebb and flows. She loves herself.

Hurston’s depiction of her childhood suggests that she was unperturbed by racism. The place, Eatonville, Florida, where she spent her childhood was not free from racial influences. Perhaps, she was too innocent to witness the racial signs before the age of 13. She was unable to recognize the signs. The town of Eatonville was founded by the formerly enslaved people who were suspicious of white visitors. Hurston was untouched by these harsh experiences. It shows that the people of Eatonville had protected their children from the mistreatment and racial abuse at the hands of white men. Hurston skillfully conveys her thoughts that her family members ‘of course’ stopped her from associating herself with the white people, if they ever caught her doing this.

Journey from Nora to a Colored Girl

The word ‘colored’ is central in the text. The title of the essay also carries the same word as it reminds that if Hurston is called the ‘colored’ girl then her own color is very important and is her identity in itself. That’s the reason, it is called, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” rather than “How It Feels to Be Colored. Hurston, again and again, gives her response to racism. She does not feel angered. She is confused about it. She is at sea to understand why people cannot highly think of racial and ethnic differences for the sake of beauty and heritage.

The author, Hurston, belongs to the African American race. In her essay, she asserts that she was not always “colored.” While discussing her childhood, she let us know that she remembers the day she became “colored.” This declaration suggests, being colored is not to have black skin. It is something different, which comes after social training. So that she was not “colored” when she was born. From the beginning of her essay, she confesses that she became “colored” eventually and she suggests that something bad is going to happen to the innocent, lively girls. This tension stays in the passage of her childhood.

It takes hardly a passage to become “a little colored girl” from Nora Hurston. Hurston was only thirteen when her mother left this world. She does not go into detail. She writes that she was sent away because of some changes in the family. She spells on the tale of her transformation into “a little colored girl.” She describes that she herself got into the riverboat. When she got off from that riverboat, she was someone else. It suggests that she become “colored” in the riverboat. She was someone who could understand that she belonged to the second class of citizens because of their race.

Racial Bullying during Childhood

Hurston does not give details about the happening in the riverboat when she was on her way to Jacksonville. One thing that she made clear was that change or transformation was heartfelt and intense. Now it’s up to her readers to imagine what had happened to her in the boat. She might have experienced something harsh in the riverboat. She might have had molestation, physical attack, sexual assault or racial slurs in the boat. She leaves it to the reader’s imagination to guess what had happened in the riverboat. Very skillfully she moves ahead by saying that, thousands of horrors an African American girl can face while travelling alone.

Nonetheless, her pains of transformation are very much obvious. The harsh experience of becoming “colored” was dehumanizing as well as unmooring. After her transformation, she says, she is no more the Zora of Orange County, now she is the little colored girl. In fact, racism has murdered her identity.

Vernacular Jazz Dance: A Key to Self Realization

Hurston performed dance for others. The people of Eatonville do not approve of her this performing tendency. They refused to pay for her dance performances. But the white men paid for her performances. The people of Eatonville regret her such tendencies. She does not say this at once. They perhaps disapproved of her performing tendencies for a reason. In the past, slaves were forced to perform for their masters.

When Hurston grows up, she dances for white people. She goes to a concert in Harlem. In that concert, she witnessed that African beats were used in rhythmic ways. Later on, these beats provided the foundations to the genres; rap, funk and hip-hop. She is fascinated by these rhythms. Hurston understands those beats wholeheartedly because they were the beats of her heritage. But Hurston’s white friends were unable to see this beauty. They could not appreciate it or were not willing to appreciate it. Her white friends merely get entertained by it as it was something manmade to get amused or pleased. But music and its rhythms symbolize human pains and pangs.

In this section, she uses the final metaphor, in which her skin of the body is equated with the dyed fabric. About her color she writes, in her own heart and mirror, she is fast brown, which means her color is fixed and stable. It cannot be changed. This dyed-fabric skin is so fixed that it cannot be rubbed off or run out of the wash.

Transformation from Zora to Cosmic Zora

In her adulthood, she loves her colored self. She, again and again, expresses her thought that she does not see this blackness of the skin like a bad thing. She writes that she is not tragically colored which suggests her acceptance for herself. She neither minds it nor permits it, making her soul gloomy. From a different angle, she conveys this thought. Perhaps society wants her to take it as something negative but she does not.

Hurston disdains the members of the sobbing schools of Negrohood who believed that nature has given this lowdown and they are meant to be inferiors. It is not without interest, many African Americans blame nature instead of society. She is not prepared to blame nature in that way. Even, she makes association with primitive culture, she does not disdain it. She accepts it and writes, primitive culture is desirable.

Hurston writes those who succeed in this world, they do regardless of their race and the color of their skins. They are made to succeed. She makes it clear that she considers herself as a strong one. She does not cry at the world but keeps herself busy at sharpening her oyster knife. This vigorous image of the author suggests that she is dangerous as well as ready for action. By using this knife metaphor, she shows herself ready to do good for the world.

Hurston comes to know that race affects her life. She concludes her essay on the point that there exists Zora but without race. Now she has become a cosmic Zora who is eager to see what the world has stored for her. She does not have separate feelings for being an American and colored girl. She considers herself a petty part of the Great Soul.

In the end, she described herself as a brown bag of miscellany. She is brown and there are many other color bags. The color cannot be ignored in this special metaphor. The content remains the same in all these bags of different color. She concludes that God randomly stuffed people in this world from the very start. This suggests that everyone in this is essentially the same and the differences among people are nor important at all.

More From Zora Neale Hurston

How It Feels To Be Colored Me

25 pages • 50 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “how it feels to be colored me”.

This guide is based on the electronic version of Zora Neale Hurston’s “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” available at the University of Virginia’s Mules and Men website. The original essay was published in the May 1928 edition of The World Tomorrow. Hurston’s essay is her explanation of how she experiences being African-American.

Hurston opens the essay with the comment that she is “a Negro” and unlike many African-Americans claims no Native American ancestry. Prior to the age of thirteen, Hurston lived in the all-black town of Eatonville, Florida, where her only contacts with nonblacks were with the Southern and Northern tourists who drove through the town. No one was curious about the familiar Southerners, but most people were so fascinated by the Northerners that they watched them from their porches.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,350+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Hurston, not content with the porch, would sit on a gatepost at the entrance of town to greet the tourists, ask them questions, ask for rides out of town, or even perform for them, only to be surprised when they gave her money for doing what she loved. At this point in her life, Hurston’s only perception of differences between whites and blacks was that whites did not live in her town and paid her for performing.

This attitude changed when Hurston was sent to Jacksonville by riverboat to attend school at thirteen. Hurston notes that for the first time, she was a “little colored girl” instead of simply being herself (par. 5, line 5). Despite this change, Hurston says she is not “tragically colored” and has no feeling that being black is a curse (par. 6, line 1).Hurston’s perspective on her place in the world is that she is instead “too busy sharpening her oyster knife,” eager to take in what the world has to offer (par. 6, line 6).

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

When people insist on reminding Hurston that she is descended from slaves, she feels no sadness about it because slavery is “sixty years in the past” and simply the price of belonging to Western civilization (par. 7, line 3). Being the descendent of slaves means for Hurston that she has even more opportunities for achievement and glory because she is starting from nothing and the nation, fixated on race, is focused on people like her. By contrast , Hurston pities whites, who are weighed down by their ancestors and stuck with maintaining their privilege.

In her present life, Hurston has moments when she only feels black if she is in an all-white setting , such as when she attends classes at Barnard College, an institution attended by few people of color. In other moments, the presence of a white person in an all-black setting also makes Hurston feel conscious of her racial identity. She describes sitting in a Harlem cabaret and being swept away by the rhythms of the music, which connect her to her African ancestry, only to be surprised by a white friend’s more casual enjoyment of the music.

Sometimes, Hurston feels no sense of racial identity. When she promenades down a main thoroughfare in Harlem, she is the “cosmic Zora”and feels more potently feminine that Peggy Hopkins Joyce, the 1920s equivalent of a Kardashian (par. 14, line 4). Hurston experiences her American identity as being indistinguishable from her racial identity. When someone discriminates against her, she is surprised, rather than angry, because it puzzles her that anyone would deprive him- or herself of the pleasure of knowing her.

Hurston closes the essay with the image of each human being asa “bag of miscellany” (par. 17, line 1),filled with a mix of worthless and precious things, distinguishable only by the color of the bags. Shespeculates that switching the contents of bags would reveal how similar they are inside and that perhaps this is exactly as God intended.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Ready to dive in?

Get unlimited access to SuperSummary for only $ 0.70 /week

Related Titles

By Zora Neale Hurston

Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo"

Zora Neale Hurston

Drenched in Light

Dust Tracks on a Road

Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick

Jonah's Gourd Vine

Moses, Man of the Mountain

Mule Bone: A Comedy of Negro Life

Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston

Mules and Men

Seraph on the Suwanee

Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica

The Eatonville Anthology

The Gilded Six-Bits

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Featured Collections

Creative nonfiction.

View Collection

Essays & Speeches

Harlem renaissance.

Issue 16.2 | 2020 — Undiminished Blackness: Zora Neale Hurston as Theory and Practice

Staging Black Affects: Hurston’s “How It Feels to Be Colored Me”

By mariel rodney.

My country needs me and if I were not here I would have to be invented. –Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book”

I belonged to them, to the nearby hotels, to the county, everybody’s Zora. –Zora Neale Hurston, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me”

“I remember the very day I became colored,” writes Zora Neale Hurston in her 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.” 1 To “become colored” conjures scenes of racial difference and geographic, socioeconomic mobility across the essay as Hurston narrates a series of physical and psychic transitions. Opposed to conventional narratives of racial belonging and exclusion, Hurston’s ribald play with “color” revises the conceptual limits of race as a stable category of identity formation. Instead, as she “remembers” color across the essay, “color comes” in different ways, alerting us to the elasticity of color in cross- and intra-racial encounters in spite of hierarchal supremacist regimes. Hurston’s turn to “color” thus stages the surplus meanings of the historically Black(ened) body for twentieth-century audiences.

One particular scene has become iconic for its invocation of the historically Black(ened) body: “I do not always feel colored. Even now I often achieve the unconscious Zora of Eatonville before the Hegira. I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background” (154). Here, color acts in excess of the embodied Black subject and, in turn, enacts the instability of racial categorization. Scenes like this illustrate Hurston’s negotiation of value and resilience across the essay. By invoking both publicity and performance repeatedly across the essay, I argue that Hurston’s staging of race invites, only to ultimately refuse, representational stability. In other words, instead of describing “race”, Hurston’s use of “colored” across the essay amplifies and obscures. In doing so she illustrates the performative and affective economies of race and language to her will. Read closely, these stagings centralize color and estrangement as tools for interrogating consciousness beyond “the color line.”

Hurston’s essay makes repeated and continued reference to various kinds of performances and stages. Early in the essay, she teases yet another depiction of the historically Black(ened) body with critical difference: “[White Northerners] liked to hear me ‘speak pieces’ and sing and wanted to see me dance the parse-me-la, and gave me generously of their small silver for doing these things, which seemed strange to me for I wanted to do them so much that I needed bribing to stop. Only they didn’t know it” (153). The familiar dancing Black figure at the center of this scene dips in and out of view here. Singing and dancing for Northern audiences, we may have seen glimpses of her atop the ship deck, the coffle, or on the plantation before considering her fleeting resemblance to Black women’s cunning performances of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Topsy. 2 Such resemblances perhaps drew scenes of subjection far closer than twentieth century Black and white audiences expected by exposing competing public desires for Black containment, albeit in the seemingly alternating extremes of racial uplift or racist caricature. 3

Instead, Hurston revises this common trope. The voyeuristic gaze of white Northerners is somewhat curtailed by the performer’s awareness to her own “joyful tendencies,” which she leverages for silver. The dancing body of the scene is “Blackened” through a performance that reifies her own capacity for agency and pleasure. In Babylon Girls , Jayna Brown describes the distinctive ways Black women wield performances of Topsy as forms of corporeal capital and resilience. 4 By extension, in this essay I explore Hurston’s appropriation of corporeal and affective capital in “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.” I also examine her appropriation of “color” – an assertion of Blackened knowledge(s) and resilience gleaned from the Black theatre – to interrogate the Black imago in public spaces.

Furthermore, I examine Hurston’s invocation of the Black(ened) body for its generative and disruptive potential. As Daphne Brooks and others show, opacity was readily used by Black performers on nineteenth and early twentieth century stages to articulate the dissonant multivocality of Black identity in public and performance spaces. 5 By signifying upon the “the metaphorical utility of blackness,” Black performers enacted insurgent forms of contestation, self-invention, and mobility.

Despite racial uplift’s growing desire to police associations with racist minstrel acts and the Black stage, Black performers actively revised Black performance methods by improvising Black-authored minstrel gestures for an emergent Black stage. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries produced a wellspring of Black stage pioneers and performers who wielded new corporeal vocabularies for interrogating Jim Crow segregation and disenfranchisement. Two pioneers of the Black stage, Bert Williams and George Walker, signified on white audiences’ expectations of “authenticity” in the 1890s by using burnt cork and billing themselves as “Two Real Coons.” Louis Chude-Sokei and W.T. Lhamon argue that their skillful corporeal performances and aesthetic innovations on stage and in song represented far more than just fame; they were forms of Black diasporic modernism that negotiated rituals of cross-cultural signification. 6

Building on this work of the emergent Black theater, it becomes clear that Hurston uses a performative and syntactical economy of “color” to stage the vibrancy and the opacity of Blackness in ways that depart from her contemporaries. Although a cursory glance at those contemporaries reveals that a lexicon around race, racial hue, passing, and colorism dominated their turn-of-the-century conversations around national identity, sexuality, and class, each deployed the illustration of race to different ends. For example, Nella Larsen in her novels Passing and Quicksand and James Weldon Johnson in Autobiography of an Ex-colored Man each deploy the trope of the tragic mulatto/a figure as a commentary and condemnation of racial hierarchy. Though Johnson’s novel signifies on “color” explicitly in the title, its eponymous character feigns a lack of awareness of “color” distinct from Hurston’s narrator in “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.” Hurston distinguishes her essay from these modes in structure and form, too, driving her use of color toward a surreal experience of “red” “yellow” and “blue” alongside Black and brown.

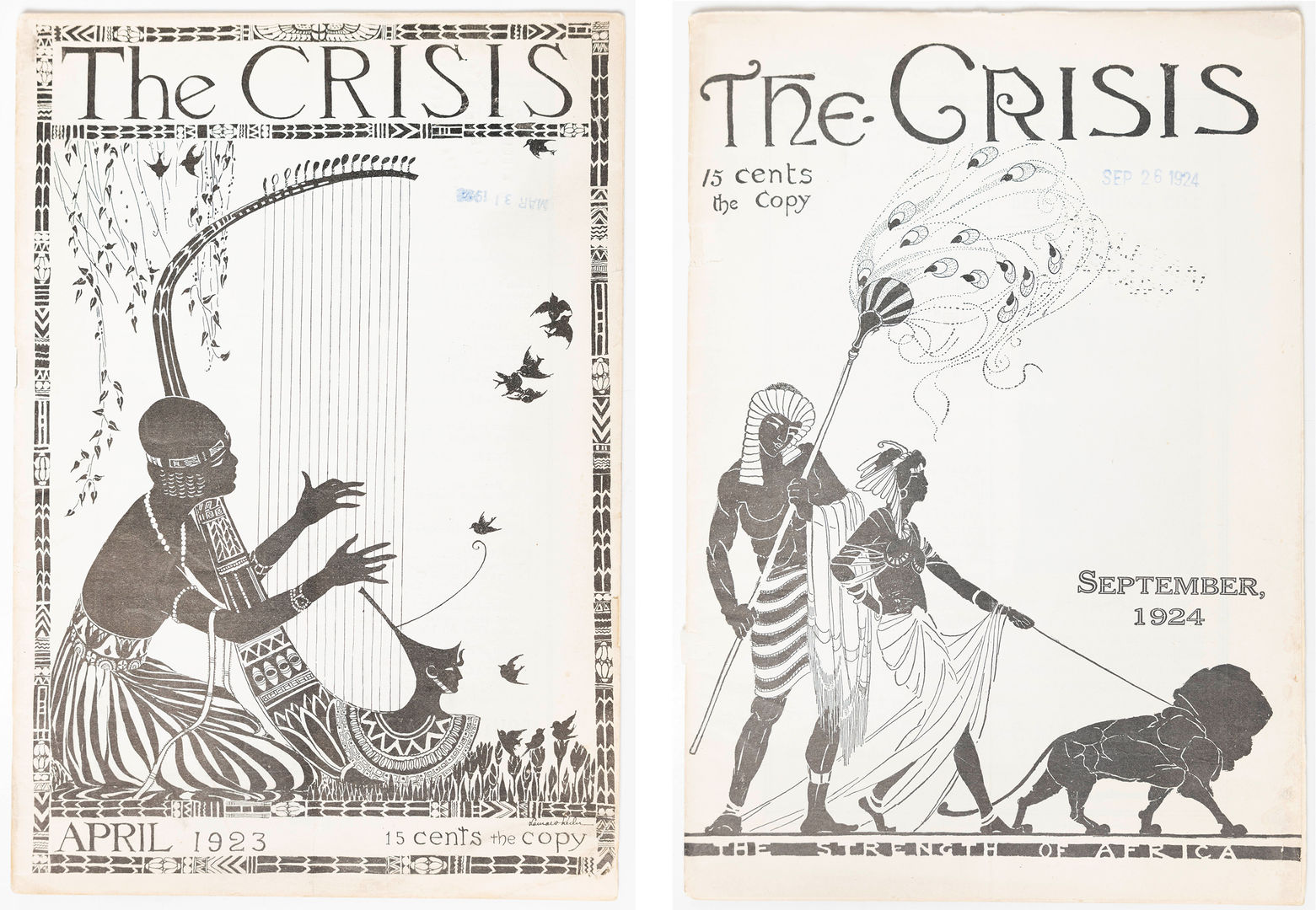

Published during the peak of the Harlem Renaissance, it is no surprise that an awareness to race informs Hurston’s iconic essay. The visual primacy of skin color and its psychosocial hierarchies are reflected across some of the most canonical texts of the period. Even as Wallace Thurman in The Blacker the Berry and Hurston in Color Struck further extend the apparent ways in which color appears in Black modern literature as an index of racialization, no other writer explores its “metaphorical utility” so richly as does Hurston in her essay. Even in the midst of such an intense flurry of material on “color,” Hurston stands apart. In “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” Hurston outlines “color” as a shifting category of performance rooted in genealogies of violence, appropriation, and affirmation. As we read, we begin to see how Hurston makes visible a range of Black performance affects.

After a spectacular debut on the Harlem literary scene barely three years prior, Hurston’s 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” dramatized an unexpected portrait of the racial artist for the unwitting readers of the World Tomorrow , an American political magazine that catered to a white readership composed mostly of women. The essay positioned Hurston as a new kind of public intellectual and an artist keen on articulating the intersecting stakes of publicity and spectacle, on the one hand, and quotidian performances of interiority, race, and racialization, on the other hand.

Despite the tendency to read the essay in the autobiographical tone its title suggests, Hurston’s mastery wields interiority as a tool that becomes central to her critical deconstruction of race. Predating “Characteristics of Negro Expression” – her now-canonical treatise on Black drama – by six years, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” is Hurston’s earliest theoretical statement on Black performance. In it, she leverages “color” to narrate, agitate, and refract contemporary sensibilities of race and culture and expertly engages and revises genealogies of performance history. Like early pioneers of the twentieth-century stage who claimed authenticity as a staging device, Hurston signifies upon the autobiographical mode in her essay.

Hurston’s seemingly simple aims in her essay promise the veneer of a compressed personal prose: short but honest glimpses into the lived experience of a Black woman writer. It is perhaps this seeming authenticity and the charged depictions of the Black(ened) body that prompted Alain Locke to write Hurston and dub her essay “a mistake.” In a letter to Hurston just days after the publication of “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” Locke explains his concern for the way in which the essay oversteps the boundaries of propriety and conjures the very images of antiquated minstrel performance that his New Negro anthology was meant to combat. 7 Locke’s palpable concern for Hurston’s essay highlights his and other racial uplift intellectuals’ desire for a stricter New Negro image to effectively police forms of Black representation to white audiences. His letter highlights his fear that Hurston had committed an irreparable act of revelation of Black interior life to outsiders, while also anticipating a range of perplexed, if not displeased, responses from Black audiences. Taking Locke’s remarks against Hurston as a critical point of departure, I would like to sit with this notion of Hurston’s “mistake” as one that is a productive and deliberate staging of opacity. Hurston’s deployment of the singing and dancing Black figure cites the divergent desires of early twentieth century Black artists, activists, and audiences by harnessing an economy of affective and corporeal strategies gleaned from the Black stage.

In his letter, Locke’s chastising of what he deems as Hurston’s professional misstep is later tempered with caution and concern: “I realize that you had opened up too soon. I had that feeling because I had myself several times made the same mistake. The only hope is in the absolute blindness of the Caucasian mind. To the things that are really revolutionary in Negro thought and feeling they are blind.” 8 Here Locke identifies what he perceives as the inability of white audiences to fully interpret the nuances of Black thought and feeling. His statement “to things that are really revolutionary … they are blind” implores Hurston to consider the ramifications of publishing an essay that perhaps was too radical for its white audiences. While Locke does not elaborate on this point further, the immediate attention to Hurston’s perceived trespass indicates a much more complex set of motives and pathways aimed towards Black creative and political liberation.

I turn to Hurston’s use of the essay’s short form and autobiographical mode of address to instigate the production of an alternative form of literary modernism that extends – even while it disrupts – the models of the New Negro movement that shaped the Harlem Renaissance. What becomes Locke’s harshest critique of this moment, its “opening up too soon” and the unyielding dizzying divulgence of an “authentic” persona, is indeed one of Hurston’s earliest and most deliberate stagings of a subversive modernism that responds to color as a formative site of political and aesthetic maneuvering and negotiation.

If we are to fully comprehend Hurston’s iconoclastic performance of color, it is useful to understand how its larger context contributed to an act of transgression within a New Negro sensibility. By the time Hurston published her essay in 1928, Locke’s The New Negro anthology had already codified the image of the New Negro that would frame the politics of respectability and cultural aspiration of the Harlem Renaissance. The battle for legitimized forms of racial uplift was one that would be fought over decidedly “new” representations of the Black cultural life – a stylized vision that mobilized collective aspirations and group fashioning towards a modern Black aesthetic. Even as Hurston contributed to Locke’s anthology and studied for a time under his mentorship and tutelage, she enacted a mode of trespass in her later essay that threatened the clean-cut separations between public/private, spectator/spectacle, and old/new modes of Blackness.

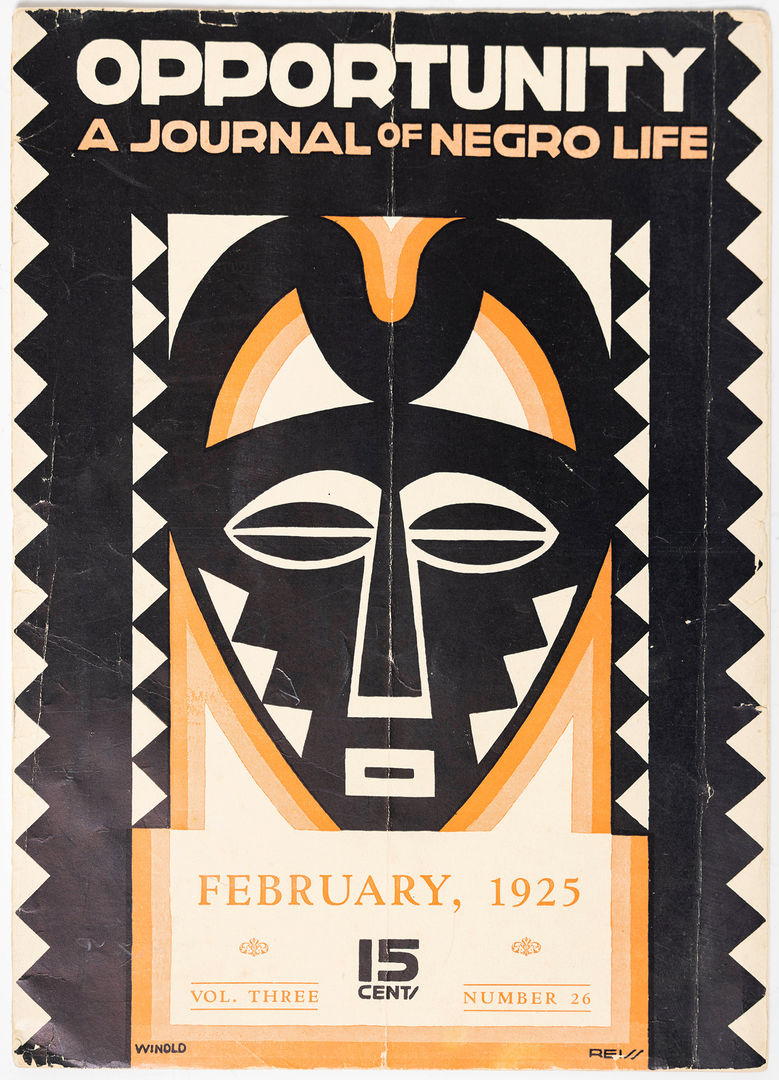

By 1925, the year Hurston first submitted her first performance piece, “Color Struck,” to Opportunity magazine, the vogue of the New Negro was in full swing. As early as March of that year, Alain Locke’s “New Negro” essay in Survey Graphic re-established the currency of a New Negro lexicon that sought to give name and purpose to the “metamorphosis” he dubbed as currently seizing hold of Black life. 9 As an expansion of that essay, Locke’s now-canonical The New Negro anthology would codify the phrase into a popular model of Black “reconstructive” thought that in many ways would provide a vocabulary for understanding the creation of a modern Black sensibility represented through artistic creation and bourgeois values.

Locke’s The New Negro collectively showcases a willful representation of Black life creatively reimagined across fiction, poetry, drama, and prose essays organized around the nature of Black art and a progressive American identity. Locke’s project effectively situated itself alongside a growing number of works that were tailored for various strands of racial uplift and that sought to reposition the sociopolitical landscape of Blackness in the twentieth century. As such, Locke’s project functions within this larger scope of racial uplift and New Negro ideology, one which gained broader currency once Locke’s anthology was published.

With respect to the anthology, Locke’s essay “The New Negro” remains one of the most important contributions to the concept of a creative Harlem Renaissance. Heralding the very transformation he describes, Locke frames a “new dynamic phase” of Black life by consistently referencing a vocabulary of newness, buoyancy, and urbanity. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Locke uses this language of newness and vibrant feeling to lay claim to the “new psychology” and “new spirit” “suddenly” seizing hold of the Black “masses.” 10

It seems just as crucial to note, however, that while Locke’s The New Negro depends upon conceptually reidentifying Blackness as a newly unified racial spirit endeared to progress and self-determination. The language of newness necessitates its stark distinction from an “old” Negro characterized by “mammy” figures and caricature. As scholars note, Locke’s language of vitality and willed revision continuously stages the key tropes of a Black reconstruction heavily laden with antinomies. 11 For Locke, “a new spirit” had been conjured, one stirred to life by the desire to break from a distorted, sentimentalized figure of Black types. Locke’s careful scripting of a new New Negro sensibility in this way is crucial for our considerations of Hurston’s project as one that carefully imagines itself within this larger conversation of racial uplift and Black social reconstruction. Even as Hurston contributed to Locke’s anthology and studied for a time under his mentorship and tutelage, she would inevitably and figuratively break with his literal attempt to contain and organize what a “new” Negro could and should look like.

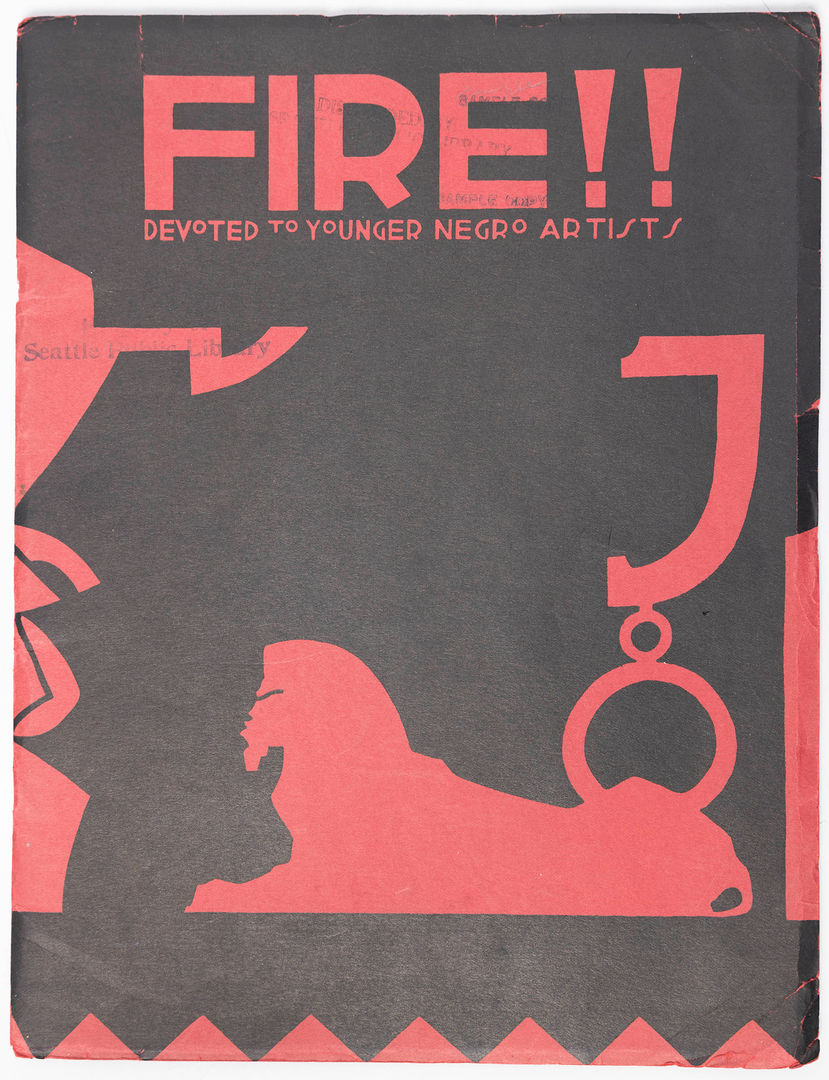

Hurston’s role within the New Negro movement is an interesting one. Realizing her participation as the youthful arm of a burgeoning movement, she fostered close collaborations with a group of artists who would eventually transform the scene of the Harlem Renaissance. Dubbed the Niggerati and intended as a subversive swipe at the propriety and class tension amidst the aesthetic arbiters of the period, they gathered over the summer of 1926 to bring to life what would become Fire!!!: A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists . Along with Wallace Thurman, Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglass, Gwendolyn Bennet, Richard Nugent, and Countee Cullen, Hurston published “Color Struck ” in Fire!!! with the intention of supporting its happily defiant theme. As Hughes describes, the journal was meant “to burn up a lot of the old, dead conventional Negro-white ideas of the past … into a realization of the existence of the younger Negro writers and artists, and provide us with an outlet for publication not available in the limited pages of the small Negro magazines then existing.” 12 From its inception, Fire!!! was meant to offend and shock, subverting the stiff values of an “old[er]” generation. 8 It seems useful, then, to consider this moment as formative within Hurston’s crafting of a subversive aesthetic that actively theorizes the aesthetic possibilities of race alongside the performance of color.

Thus, Hurston’s early portraits of Black life teetered on the edge of a hardly won fight over representation and collective posturing. My attention to the slippage afforded by Hurston’s “mistake” turns to the ways in which she stages the production of new meaning through the refracted lens of color. Simply put, I am most interested in Hurston’s transformative subversion of a voyeuristic white gaze for a larger performance of agency and pleasure. How might we read Hurston’s essay as its own “speak piece”? What is a “speak piece” in Hurston’s hands, if not a series of performative re-enactments of Blackness that deconstruct and re-negotiate the artist’s “place” as a racialized public figure? Hurston’s turn to the autobiographical representational “I” affirms this strategy and the nature of its constructedness.

Into the Gallery

Returning to Hurston’s pivotal line “I remember the very day that I became colored” is instructive. Capturing her audience with the promise of divulging how it feels to be colored, Hurston’s essay is staged from its very opening. The title creates the expectation that the author will provide some racially authentic personal insight on race relations. We should consider, however, how Hurston’s title ruptures the very expectations into which it seeks to play. Its awkward syntax highlights this interpretive break and calls attention to how we read the emphasis on Hurston’s “colored.” Is it “how it feels to be colored me” or “how it feels to be a colored me”? Is “colored” the stable description of the author’s condition or are there other possibilities for reading color within the text? Anticipating her later claim that drama is elemental to Black life, Hurston in her essay revises the implicit fixit of colored as a noun and recasts its potential to act and enact through performance. Through this frame we can understand color as a verb that describes the author as an actor, an agent of action and motion, who demands that we continue to hold the following questions in tow: who is color acting upon, and who is enacting/exacting it?

Across the essay, Hurston plays with the slippage that these questions of meaning and positionality afford. The succinct and irrefutable fact of Blackness that launches the essay: “I am colored” is thrown into tension with the “day that [she] becomes colored.” These “shifts,” which persist across the essay in alternately playful and discomforting ways, construct a narrative around the speaker’s unmoored positionality of color as the site of performance and racial meaning. Revealing, for example, her dizzying kaleidoscopic play with color, Hurston’s descriptions fluctuate dependent upon the context of each racial encounter. As we read, we are reminded that Hurston’s speaker does not always feel colored. Affectively, Hurston works to create distinction and distance in the text between a “self” that physically and psychically negotiates public spaces. That she feels “most colored when … thrown against a sharp white background” produces disorienting results. Indeed, Hurston’s rhetorical gallery reveals itself to be a site of contradiction and paradox.

It is in these moments that Hurston’s reaffirms her rhetorical mastery: “For instance at Barnard, ‘beside the waters of the Hudson,’ I feel my race. Among the thousand white persons, I am a dark rock surged upon, and overswept, but through it all I remain myself. When covered by the waters, I am; and the ebb but reveals me again” (154). Hurston’s metaphor re-casts darkness as resilience, rooting the speaker in an interstitial space of kinship and individualism. Though “surged upon” by “a thousand white persons,” Hurston writes, “I am.” Such epistemic defiance and certitude in the face of obliteration signifies upon histories of enslavement and minstrelsy. Paradoxically, Hurston affirms selfhood at precisely the moment of obscurity and erasure.

Color Capital

My attention to Hurston’s subtle turn of tricks here calls for a reading of her colorful (or coloring) practice as one that takes on further layers of meaning when read as an interrogation of how we read Black performance and its legacies of appropriation and celebration. When Hurston marks color as an active site of epistemic production across the essay, she invokes the specter of minstrelsy and actively relishes in her own appropriation of its calcified layers. It is here that her construction of the gallery – a living archive for quotidian and spectacular experiences of color – becomes realized. It is in this light that Hurston enables additional readings of her text, taunting misapprehension and daring her audience to challenge what they presume to know about racial difference. Hurston coyly describes the following scene: “The front porch might seem a daring place for the rest of the town, but it was a gallery seat for me. My favorite place was atop the gate post. Proscenium box for a born first nighter. Not only did I enjoy the show but I didn’t mind the actors knowing that I liked it” (152). Claiming the best seats in the house for herself, Hurston transforms the space of the Southern front porch into a space of interregional performance exchange. She marks out the domestic space of the porch as a site of great potential. It is here that she will practice negotiating a gendered, racial gaze, while leveraging that space as one of pleasure and power. In choosing to speak and enjoy her own “joyful tendencies” for herself, Hurston seizes the proscenium box for self-pleasure and so appropriates the gaze traditionally marked by legacies of minstrel caricature for herself.

Hurston marks these transgressions across the essay with sheer delight. She dissembles and disassembles, marking the interstitial space for radical critique, departure, and pleasure between literary form and performative production. In this lack of resolution, she performs a pleasure that carries across the breadth of the essay, at once feigning ignorance at the limits of a provocative persona and welcoming the refractions that come with holding up a mirror to an American subjectivity.

If we return to Hurston’s description of singing and dancing for Northern audiences, we see the ways in which this performative exchange is full of shifts and masked negotiations: “The [white people] liked to hear me ‘speak pieces’ and sing and wanted to see me dance the parse-me-la, and gave me generously of their silver for doing these things, which seemed strange to me for I wanted to do them so much that I needed bribing to stop. Only they didn’t know it” (152). Hurston envisions herself as an actor, performing speak pieces and pas ma las. 13 Unabashedly, Hurston’s description signifies upon performance histories of minstrelsy, vaudeville, and caricatured dance – the very forms of representation against which Locke and others so carefully constructed their New Negro respectability. Hurston’s willingness and delight in performing the pas ma la immediately references the popular caricatured dance of the nineteenth century, along with the racial tensions that accompanied such performances. That Hurston figures her own performance within a performance here, is crucial for how she manipulates the personal essay as both a site of disclosure and stylized display. The pas ma la symbolizes Hurston’s desire to break antinomies of new/old, serious/comic, past/present.

Created by Ernest Hogan, the pas ma las was a comic dance often performed in blackface that consisted of a walk forward with three steps backward. The dance gained increasing popularity when Hogan published his 1895 hit “La Pas Ma Las.” The chorus is as follows:

Hand upon yp’ head, let your mind roll back, Back, back back and look at the stars Stand up rightly, dance it brightly That’s the Pas Ma La.

Aware of her complicity in invoking the minstrel type of the “happy darky” who dances brightly for white amusement, Hurston invokes multiple layers of performative subversion here. On one level we should read Hurston as deploying a form of ironic reversal; one where voyeuristic desire shifts in the service of the performer herself. Here Hurston seems to recast caricatured performance with an assumed agency fueled by her own desire for pleasure. Head back, and eyes looking upward “at the stars,” Hurston’s layered performance codes ambition and upward mobility by co-opting the pleasure politics of the scene.

Audiences are often struck both by Hurston’s invocation of the minstrel show and by her willful revision of its affectations. These affectations – referenced by her turn to affect, scripted language, gesture, and stage positionality – lie simultaneously within and beyond the scope of a capital economy of minstrel gesture. Hurston performs a particular kind of Southern vernacular utterance here, one that professes her familiarity with both the area and the expectations of Northern white travelers. She thus stages a theatre of her own making, deploying familiar scripts of Black and white exchange to achieve unfamiliar ends. By staging a series of roles with white Northerners, Hurston emphasizes her ability to glean profit and pleasure from “negotiations” with white Northerners and readers. In Hurston’s essay, pleasure and reversal (or the pleasure of reversal) may be reward enough.

Yet this depiction of pleasure is short-lived. Hurston’s essay brilliantly anticipates that her valuation of these subversive scenes will be misinterpreted. Across the essay, we see these moments frequently. They appear most tellingly as Hurston describes “rudely ending negotiations” if her family sees her with white Northerners, and in the New World Cabaret scene, where she realizes that her white friend cannot participate in her indulgence of a “primal” color performance. Notably, Hurston stages these moments as interpretive gaps of knowledge and experience. Put differently, white and Black actors perceive color and value across an immutable line of difference.

While Black minstrelsy offers Hurston a vehicle through which self-possession and pleasure might be discernable, it also lets her mimic the forms that dispossession and estrangement can take. Hurston uses possession to narrate her whimsical and often-striking performance acts in the essay, turning later to dispossession as an analog that plots a Black historical trajectory. When she decides to claim the “gate-post” as a pivotal site of pleasure, performance, and youthful exchange, it is her dancing for outsiders that places her beyond the space of permissible Black social interaction and outside one circle of kinship. Despite this displacement, Hurston insists on claiming those who would reject her and declares, “I was their Zora nevertheless.” In another scene that narrates (dis)possession and “color,” Hurston describes:

Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the granddaughter of slaves. It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you. The terrible struggle that made me an American out of a potential slave said “On the line!” The Reconstruction said “Get set!” and the generation before said “Go!” I am off to a flying start and I must not halt in the stretch to look behind and weep. Slavery is the price I paid for civilization, and the choice was not with me. It is a bully adventure and worth all that I have paid through my ancestors for it. No one on earth ever had a greater chance for glory.

In this puzzling scene, Hurston employs a retelling of enslavement cast as the “price … paid for civilization.” By toggling between possession and dispossession, Hurston marks the critical ways in which the legacies of slavery rehearse and give rise to new and violent regimes of power and progress in the modern era. Her parody of neocolonialist forms of thought draws on the color line and reifies the imagery of the line in the form of two compelling images: a race and the national stage. This repeated invocation of the stage punctures the fourth wall of the parodic farce. She again places herself at the proscenium (another formative line of sorts) and, this time, reveals her winking eye as she explains, “It is quite exciting to hold the center of the national stage, with the spectators not knowing whether to laugh or to weep” (153). By embedding such scripted moments of dance, gesture, and mimicry into the essay, Hurston reimagines the chilling and capacious strategies of the Blackened body in performance.

Everybody’s Zora

Nearly one hundred years since its first publication, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” has staying power. It is Hurston’s most quoted essay. Generations of everyday readers, scholars, poets, and conceptual artists have drawn from her meditations on race and American society. In her vignettes, we see glimpses of a Zora who appears equal parts charming, endearing, challenging, and provocative. Everybody’s Zora indeed.

Yet Hurston’s kaleidoscopic treatise on and of color refuses static interpretation. She may be everyone’s Zora, but she is possessed by no one. To “feel” colored is to activate the simultaneity of being fixed and mutable across racial encounters. Becoming colored, uncolored, recolored, and “so colored,” Hurston’s performance sweeps between moments when the “color comes” and those when the color is fixed, “warranted not to rub or run.” She appears to fit simultaneously into various versions of her that we have encountered over time. 14 We know her as a bold Harlem Renaissance icon, passionate literary maestra, fearless researcher, and committed anthropologist-archivist. Her literary and popular range and influence is both materially real and of mythic proportions (Spillers). 15 I expect that we will continue to see more versions of Hurston emerge over time, as many versions of her as there are of ourselves. Unsurprisingly, Hurston’s essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” insists that we push against the still-life portrait of the artist by attending to her strategies of performance.

Of the many titles we might attribute to Hurston’s accolades we might add performance artist to the list. The artist’s body is center stage in her 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.” As a writer, scholar, and performance artist extraordinaire, Hurston turns to the elasticity of color and its conceptual range in her essay. Hurston’s understanding of color is performative; it enlivens the essay while displaying the gendered, epistemic, sociopolitical work that color enacts. Here, color vis-a-vie the body takes center stage and backstage. Elsewhere in the essay, color is context and background; color is mutable, irremovable. Everywhere, color is live.

It is precisely Hurston’s publicity then and now that contribute to a multitiered reading of her text as performance. Hurston’s production of intimacy and belonging across the essay is inherently tied to her ability to deliver a persona that delights in simultaneity. Hers is a persona idealized: desiring and desirable, specific and yet unfixed. In the essay, she is both local – the Zora of Eatonville – and the cosmic Zora.

- Zora Neale Hurston, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” in I Love Myself When I Am Laughing: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader ( Feminist Press, 1979), 152–5. [ ↩ ]

- Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997); and Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Black Women and the Making of the Modern (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 57–8. [ ↩ ]

- Kevin K. Gaines, Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture in the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996). [ ↩ ]

- Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Black Women and the Making of the Modern (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 56–91. [ ↩ ]

- Daphne A. Brooks, Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom 1850–1910 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006). [ ↩ ]

- Louis Chude-Sokei, The Last “Darky”: Bert Williams, Black-on-Black Minstrelsy, and the African Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); and W.T. Lhamon, Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998). [ ↩ ]

- Alain Locke letter to Zora Neale Hurston, 2 June 1928, quoted in Eric Watts, Hearing the Hurt: Rhetoric, Aesthetics, and the Politics of the New Negro Movement (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 2012). See also Alain Locke, The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925; repr., New York: Arno Press, 1968). [ ↩ ]

- Ibid. [ ↩ ] [ ↩ ]

- Alain Locke, “The New Negro,” Survey Graphic, March1925. [ ↩ ]

- Locke, The New Negro, 3. [ ↩ ]

- Soyica Diggs Colbert, The African American Theatrical Body: Reception, Performance, and the Stage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 97. [ ↩ ]