- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

21 Problem Solving

Miriam Bassok, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Laura R. Novick, Department of Psychology and Human Development, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

- Published: 21 November 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter follows the historical development of research on problem solving. It begins with a description of two research traditions that addressed different aspects of the problem-solving process: ( 1 ) research on problem representation (the Gestalt legacy) that examined how people understand the problem at hand, and ( 2 ) research on search in a problem space (the legacy of Newell and Simon) that examined how people generate the problem's solution. It then describes some developments in the field that fueled the integration of these two lines of research: work on problem isomorphs, on expertise in specific knowledge domains (e.g., chess, mathematics), and on insight solutions. Next, it presents examples of recent work on problem solving in science and mathematics that highlight the impact of visual perception and background knowledge on how people represent problems and search for problem solutions. The final section considers possible directions for future research.

People are confronted with problems on a daily basis, be it trying to extract a broken light bulb from a socket, finding a detour when the regular route is blocked, fixing dinner for unexpected guests, dealing with a medical emergency, or deciding what house to buy. Obviously, the problems people encounter differ in many ways, and their solutions require different types of knowledge and skills. Yet we have a sense that all the situations we classify as problems share a common core. Karl Duncker defined this core as follows: “A problem arises when a living creature has a goal but does not know how this goal is to be reached. Whenever one cannot go from the given situation to the desired situation simply by action [i.e., by the performance of obvious operations], then there has to be recourse to thinking” (Duncker, 1945 , p. 1). Consider the broken light bulb. The obvious operation—holding the glass part of the bulb with one's fingers while unscrewing the base from the socket—is prevented by the fact that the glass is broken. Thus, there must be “recourse to thinking” about possible ways to solve the problem. For example, one might try mounting half a potato on the broken bulb (we do not know the source of this creative solution, which is described on many “how to” Web sites).

The above definition and examples make it clear that what constitutes a problem for one person may not be a problem for another person, or for that same person at another point in time. For example, the second time one has to remove a broken light bulb from a socket, the solution likely can be retrieved from memory; there is no problem. Similarly, tying shoes may be considered a problem for 5-year-olds but not for readers of this chapter. And, of course, people may change their goal and either no longer have a problem (e.g., take the guests to a restaurant instead of fixing dinner) or attempt to solve a different problem (e.g., decide what restaurant to go to). Given the highly subjective nature of what constitutes a problem, researchers who study problem solving have often presented people with novel problems that they should be capable of solving and attempted to find regularities in the resulting problem-solving behavior. Despite the variety of possible problem situations, researchers have identified important regularities in the thinking processes by which people (a) represent , or understand, problem situations and (b) search for possible ways to get to their goal.

A problem representation is a model constructed by the solver that summarizes his or her understanding of the problem components—the initial state (e.g., a broken light bulb in a socket), the goal state (the light bulb extracted), and the set of possible operators one may apply to get from the initial state to the goal state (e.g., use pliers). According to Reitman ( 1965 ), problem components differ in the extent to which they are well defined . Some components leave little room for interpretation (e.g., the initial state in the broken light bulb example is relatively well defined), whereas other components may be ill defined and have to be defined by the solver (e.g., the possible actions one may take to extract the broken bulb). The solver's representation of the problem guides the search for a possible solution (e.g., possible attempts at extracting the light bulb). This search may, in turn, change the representation of the problem (e.g., finding that the goal cannot be achieved using pliers) and lead to a new search. Such a recursive process of representation and search continues until the problem is solved or until the solver decides to abort the goal.

Duncker ( 1945 , pp. 28–37) documented the interplay between representation and search based on his careful analysis of one person's solution to the “Radiation Problem” (later to be used extensively in research analogy, see Holyoak, Chapter 13 ). This problem requires using some rays to destroy a patient's stomach tumor without harming the patient. At sufficiently high intensity, the rays will destroy the tumor. However, at that intensity, they will also destroy the healthy tissue surrounding the tumor. At lower intensity, the rays will not harm the healthy tissue, but they also will not destroy the tumor. Duncker's analysis revealed that the solver's solution attempts were guided by three distinct problem representations. He depicted these solution attempts as an inverted search tree in which the three main branches correspond to the three general problem representations (Duncker, 1945 , p. 32). We reproduce this diagram in Figure 21.1 . The desired solution appears on the rightmost branch of the tree, within the general problem representation in which the solver aims to “lower the intensity of the rays on their way through healthy tissue.” The actual solution is to project multiple low-intensity rays at the tumor from several points around the patient “by use of lens.” The low-intensity rays will converge on the tumor, where their individual intensities will sum to a level sufficient to destroy the tumor.

A search-tree representation of one subject's solution to the radiation problem, reproduced from Duncker ( 1945 , p. 32).

Although there are inherent interactions between representation and search, some researchers focus their efforts on understanding the factors that affect how solvers represent problems, whereas others look for regularities in how they search for a solution within a particular representation. Based on their main focus of interest, researchers devise or select problems with solutions that mainly require either constructing a particular representation or finding the appropriate sequence of steps leading from the initial state to the goal state. In most cases, researchers who are interested in problem representation select problems in which one or more of the components are ill defined, whereas those who are interested in search select problems in which the components are well defined. The following examples illustrate, respectively, these two problem types.

The Bird-and-Trains problem (Posner, 1973 , pp. 150–151) is a mathematical word problem that tends to elicit two distinct problem representations (see Fig. 21.2a and b ):

Two train stations are 50 miles apart. At 2 p.m. one Saturday afternoon two trains start toward each other, one from each station. Just as the trains pull out of the stations, a bird springs into the air in front of the first train and flies ahead to the front of the second train. When the bird reaches the second train, it turns back and flies toward the first train. The bird continues to do this until the trains meet. If both trains travel at the rate of 25 miles per hour and the bird flies at 100 miles per hour, how many miles will the bird have flown before the trains meet? Fig. 21.2 Open in new tab Download slide Alternative representations of Posner's ( 1973 ) trains-and-bird problem. Adapted from Novick and Hmelo ( 1994 ).

Some solvers focus on the back-and-forth path of the bird (Fig. 21.2a ). This representation yields a problem that would be difficult for most people to solve (e.g., a series of differential equations). Other solvers focus on the paths of the trains (Fig. 21.2b ), a representation that yields a relatively easy distance-rate-time problem.

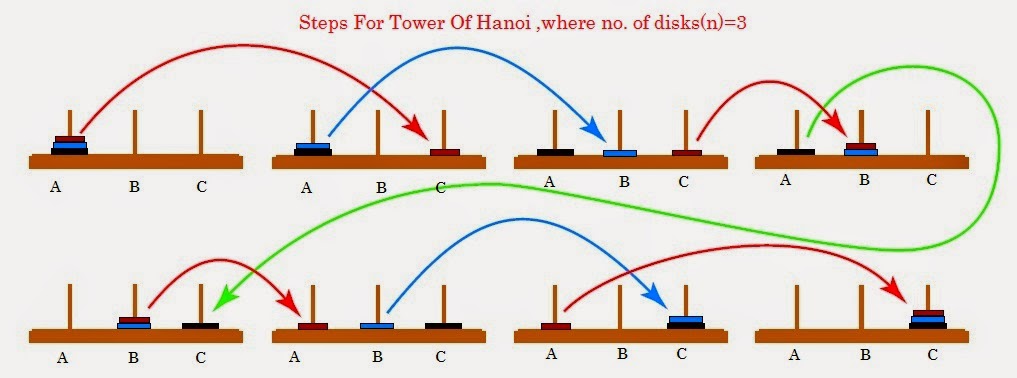

The Tower of Hanoi problem falls on the other end of the representation-search continuum. It leaves little room for differences in problem representations, and the primary work is to discover a solution path (or the best solution path) from the initial state to the goal state .

There are three pegs mounted on a base. On the leftmost peg, there are three disks of differing sizes. The disks are arranged in order of size with the largest disk on the bottom and the smallest disk on the top. The disks may be moved one at a time, but only the top disk on a peg may be moved, and at no time may a larger disk be placed on a smaller disk. The goal is to move the three-disk tower from the leftmost peg to the rightmost peg.

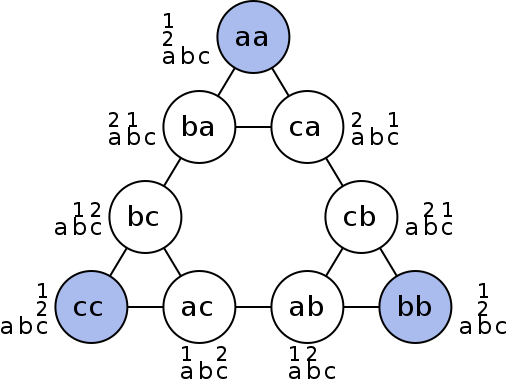

Figure 21.3 shows all the possible legal arrangements of disks on pegs. The arrows indicate transitions between states that result from moving a single disk, with the thicker gray arrows indicating the shortest path that connects the initial state to the goal state.

The division of labor between research on representation versus search has distinct historical antecedents and research traditions. In the next two sections, we review the main findings from these two historical traditions. Then, we describe some developments in the field that fueled the integration of these lines of research—work on problem isomorphs, on expertise in specific knowledge domains (e.g., chess, mathematics), and on insight solutions. In the fifth section, we present some examples of recent work on problem solving in science and mathematics. This work highlights the role of visual perception and background knowledge in the way people represent problems and search for problem solutions. In the final section, we consider possible directions for future research.

Our review is by no means an exhaustive one. It follows the historical development of the field and highlights findings that pertain to a wide variety of problems. Research pertaining to specific types of problems (e.g., medical problems), specific processes that are involved in problem solving (e.g., analogical inferences), and developmental changes in problem solving due to learning and maturation may be found elsewhere in this volume (e.g., Holyoak, Chapter 13 ; Smith & Ward, Chapter 23 ; van Steenburgh et al., Chapter 24 ; Simonton, Chapter 25 ; Opfer & Siegler, Chapter 30 ; Hegarty & Stull, Chapter 31 ; Dunbar & Klahr, Chapter 35 ; Patel et al., Chapter 37 ; Lowenstein, Chapter 38 ; Koedinger & Roll, Chapter 40 ).

All possible problem states for the three-disk Tower of Hanoi problem. The thicker gray arrows show the optimum solution path connecting the initial state (State #1) to the goal state (State #27).

Problem Representation: The Gestalt Legacy

Research on problem representation has its origins in Gestalt psychology, an influential approach in European psychology during the first half of the 20th century. (Behaviorism was the dominant perspective in American psychology at this time.) Karl Duncker published a book on the topic in his native German in 1935, which was translated into English and published 10 years later as the monograph On Problem-Solving (Duncker, 1945 ). Max Wertheimer also published a book on the topic in 1945, titled Productive Thinking . An enlarged edition published posthumously includes previously unpublished material (Wertheimer, 1959 ). Interestingly, 1945 seems to have been a watershed year for problem solving, as mathematician George Polya's book, How to Solve It , also appeared then (a second edition was published 12 years later; Polya, 1957 ).

The Gestalt psychologists extended the organizational principles of visual perception to the domain of problem solving. They showed that various visual aspects of the problem, as well the solver's prior knowledge, affect how people understand problems and, therefore, generate problem solutions. The principles of visual perception (e.g., proximity, closure, grouping, good continuation) are directly relevant to problem solving when the physical layout of the problem, or a diagram that accompanies the problem description, elicits inferences that solvers include in their problem representations. Such effects are nicely illustrated by Maier's ( 1930 ) nine-dot problem: Nine dots are arrayed in a 3x3 grid, and the task is to connect all the dots by drawing four straight lines without lifting one's pencil from the paper. People have difficulty solving this problem because their initial representations generally include a constraint, inferred from the configuration of the dots, that the lines should not go outside the boundary of the imaginary square formed by the outer dots. With this constraint, the problem cannot be solved (but see Adams, 1979 ). Without this constraint, the problem may be solved as shown in Figure 21.4 (though the problem is still difficult for many people; see Weisberg & Alba, 1981 ).

The nine-dot problem is a classic insight problem (see van Steenburgh et al., Chapter 24 ). According to the Gestalt view (e.g., Duncker, 1945 ; Kohler, 1925 ; Maier, 1931 ; see Ohlsson, 1984 , for a review), the solution to an insight problem appears suddenly, accompanied by an “aha!” sensation, immediately following the sudden “restructuring” of one's understanding of the problem (i.e., a change in the problem representation): “The decisive points in thought-processes, the moments of sudden comprehension, of the ‘Aha!,’ of the new, are always at the same time moments in which such a sudden restructuring of the thought-material takes place” (Duncker, 1945 , p. 29). For the nine-dot problem, one view of the required restructuring is that the solver relaxes the constraint implied by the perceptual form of the problem and realizes that the lines may, in fact, extend past the boundary of the imaginary square. Later in the chapter, we present more recent accounts of insight.

The entities that appear in a problem also tend to evoke various inferences that people incorporate into their problem representations. A classic demonstration of this is the phenomenon of functional fixedness , introduced by Duncker ( 1945 ): If an object is habitually used for a certain purpose (e.g., a box serves as a container), it is difficult to see

A solution to the nine-dot problem.

that object as having properties that would enable it to be used for a dissimilar purpose. Duncker's basic experimental paradigm involved two conditions that varied in terms of whether the object that was crucial for solution was initially used for a function other than that required for solution.

Consider the candles problem—the best known of the five “practical problems” Duncker ( 1945 ) investigated. Three candles are to be mounted at eye height on a door. On the table, for use in completing this task, are some tacks and three boxes. The solution is to tack the three boxes to the door to serve as platforms for the candles. In the control condition, the three boxes were presented to subjects empty. In the functional-fixedness condition, they were filled with candles, tacks, and matches. Thus, in the latter condition, the boxes initially served the function of container, whereas the solution requires that they serve the function of platform. The results showed that 100% of the subjects who received empty boxes solved the candles problem, compared with only 43% of subjects who received filled boxes. Every one of the five problems in this study showed a difference favoring the control condition over the functional-fixedness condition, with average solution rates across the five problems of 97% and 58%, respectively.

The function of the objects in a problem can be also “fixed” by their most recent use. For example, Birch and Rabinowitz ( 1951 ) had subjects perform two consecutive tasks. In the first task, people had to use either a switch or a relay to form an electric circuit. After completing this task, both groups of subjects were asked to solve Maier's ( 1931 ) two-ropes problem. The solution to this problem requires tying an object to one of the ropes and making the rope swing as a pendulum. Subjects could create the pendulum using either the object from the electric-circuit task or the other object. Birch and Rabinowitz found that subjects avoided using the same object for two unrelated functions. That is, those who used the switch in the first task made the pendulum using the relay, and vice versa. The explanations subjects subsequently gave for their object choices revealed that they were unaware of the functional-fixedness constraint they imposed on themselves.

In addition to investigating people's solutions to such practical problems as irradiating a tumor, mounting candles on the wall, or tying ropes, the Gestalt psychologists examined how people understand and solve mathematical problems that require domain-specific knowledge. For example, Wertheimer ( 1959 ) observed individual differences in students' learning and subsequent application of the formula for finding the area of a parallelogram (see Fig. 21.5a ). Some students understood the logic underlying the learned formula (i.e., the fact that a parallelogram can be transformed into a rectangle by cutting off a triangle from one side and pasting it onto the other side) and exhibited “productive thinking”—using the same logic to find the area of the quadrilateral in Figure 21.5b and the irregularly shaped geometric figure in Figure 21.5c . Other students memorized the formula and exhibited “reproductive thinking”—reproducing the learned solution only to novel parallelograms that were highly similar to the original one.

The psychological study of human problem solving faded into the background after the demise of the Gestalt tradition (during World War II), and problem solving was investigated only sporadically until Allen Newell and Herbert Simon's ( 1972 ) landmark book Human Problem Solving sparked a flurry of research on this topic. Newell and Simon adopted and refined Duncker's ( 1945 ) methodology of collecting and analyzing the think-aloud protocols that accompany problem solutions and extended Duncker's conceptualization of a problem solution as a search tree. However, their initial work did not aim to extend the Gestalt findings

Finding the area of ( a ) a parallelogram, ( b ) a quadrilateral, and ( c ) an irregularly shaped geometric figure. The solid lines indicate the geometric figures whose areas are desired. The dashed lines show how to convert the given figures into rectangles (i.e., they show solutions with understanding).

pertaining to problem representation. Instead, as we explain in the next section, their objective was to identify the general-purpose strategies people use in searching for a problem solution.

Search in a Problem Space: The Legacy of Newell and Simon

Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) wrote a magnum opus detailing their theory of problem solving and the supporting research they conducted with various collaborators. This theory was grounded in the information-processing approach to cognitive psychology and guided by an analogy between human and artificial intelligence (i.e., both people and computers being “Physical Symbol Systems,” Newell & Simon, 1976 ; see Doumas & Hummel, Chapter 5 ). They conceptualized problem solving as a process of search through a problem space for a path that connects the initial state to the goal state—a metaphor that alludes to the visual or spatial nature of problem solving (Simon, 1990 ). The term problem space refers to the solver's representation of the task as presented (Simon, 1978 ). It consists of ( 1 ) a set of knowledge states (the initial state, the goal state, and all possible intermediate states), ( 2 ) a set of operators that allow movement from one knowledge state to another, ( 3 ) a set of constraints, and ( 4 ) local information about the path one is taking through the space (e.g., the current knowledge state and how one got there).

We illustrate the components of a problem space for the three-disk Tower of Hanoi problem, as depicted in Figure 21.3 . The initial state appears at the top (State #1) and the goal state at the bottom right (State #27). The remaining knowledge states in the figure are possible intermediate states. The current knowledge state is the one at which the solver is located at any given point in the solution process. For example, the current state for a solver who has made three moves along the optimum solution path would be State #9. The solver presumably would know that he or she arrived at this state from State #5. This knowledge allows the solver to recognize a move that involves backtracking. The three operators in this problem are moving each of the three disks from one peg to another. These operators are subject to the constraint that a larger disk may not be placed on a smaller disk.

Newell and Simon ( 1972 ), as well as other contemporaneous researchers (e.g., Atwood & Polson, 1976 ; Greeno, 1974 ; Thomas, 1974 ), examined how people traverse the spaces of various well-defined problems (e.g., the Tower of Hanoi, Hobbits and Orcs). They discovered that solvers' search is guided by a number of shortcut strategies, or heuristics , which are likely to get the solver to the goal state without an extensive amount of search. Heuristics are often contrasted with algorithms —methods that are guaranteed to yield the correct solution. For example, one could try every possible move in the three-disk Tower of Hanoi problem and, eventually, find the correct solution. Although such an exhaustive search is a valid algorithm for this problem, for many problems its application is very time consuming and impractical (e.g., consider the game of chess).

In their attempts to identify people's search heuristics, Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) relied on two primary methodologies: think-aloud protocols and computer simulations. Their use of think-aloud protocols brought a high degree of scientific rigor to the methodology used by Duncker ( 1945 ; see Ericsson & Simon, 1980 ). Solvers were required to say out loud everything they were thinking as they solved the problem, that is, everything that went through their verbal working memory. Subjects' verbalizations—their think-aloud protocols—were tape-recorded and then transcribed verbatim for analysis. This method is extremely time consuming (e.g., a transcript of one person's solution to the cryptarithmetic problem DONALD + GERALD = ROBERT, with D = 5, generated a 17-page transcript), but it provides a detailed record of the solver's ongoing solution process.

An important caveat to keep in mind while interpreting a subject's verbalizations is that “a protocol is relatively reliable only for what it positively contains, but not for that which it omits” (Duncker, 1945 , p. 11). Ericsson and Simon ( 1980 ) provided an in-depth discussion of the conditions under which this method is valid (but see Russo, Johnson, & Stephens, 1989 , for an alternative perspective). To test their interpretation of a subject's problem solution, inferred from the subject's verbal protocol, Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) created a computer simulation program and examined whether it solved the problem the same way the subject did. To the extent that the computer simulation provided a close approximation of the solver's step-by-step solution process, it lent credence to the researcher's interpretation of the verbal protocol.

Newell and Simon's ( 1972 ) most famous simulation was the General Problem Solver or GPS (Ernst & Newell, 1969 ). GPS successfully modeled human solutions to problems as different as the Tower of Hanoi and the construction of logic proofs using a single general-purpose heuristic: means-ends analysis . This heuristic captures people's tendency to devise a solution plan by setting subgoals that could help them achieve their final goal. It consists of the following steps: ( 1 ) Identify a difference between the current state and the goal (or subgoal ) state; ( 2 ) Find an operator that will remove (or reduce) the difference; (3a) If the operator can be directly applied, do so, or (3b) If the operator cannot be directly applied, set a subgoal to remove the obstacle that is preventing execution of the desired operator; ( 4 ) Repeat steps 1–3 until the problem is solved. Next, we illustrate the implementation of this heuristic for the Tower of Hanoi problem, using the problem space in Figure 21.3 .

As can be seen in Figure 21.3 , a key difference between the initial state and the goal state is that the large disk is on the wrong peg (step 1). To remove this difference (step 2), one needs to apply the operator “move-large-disk.” However, this operator cannot be applied because of the presence of the medium and small disks on top of the large disk. Therefore, the solver may set a subgoal to move that two-disk tower to the middle peg (step 3b), leaving the rightmost peg free for the large disk. A key difference between the initial state and this new subgoal state is that the medium disk is on the wrong peg. Because application of the move-medium-disk operator is blocked, the solver sets another subgoal to move the small disk to the right peg. This subgoal can be satisfied immediately by applying the move-small-disk operator (step 3a), generating State #3. The solver then returns to the previous subgoal—moving the tower consisting of the small and medium disks to the middle peg. The differences between the current state (#3) and the subgoal state (#9) can be removed by first applying the move-medium-disk operator (yielding State #5) and then the move-small-disk operator (yielding State #9). Finally, the move-large-disk operator is no longer blocked. Hence, the solver moves the large disk to the right peg, yielding State #11.

Notice that the subgoals are stacked up in the order in which they are generated, so that they pop up in the order of last in first out. Given the first subgoal in our example, repeated application of the means-ends analysis heuristic will yield the shortest-path solution, indicated by the large gray arrows. In general, subgoals provide direction to the search and allow solvers to plan several moves ahead. By assessing progress toward a required subgoal rather than the final goal, solvers may be able to make moves that otherwise seem unwise. To take a concrete example, consider the transition from State #1 to State #3 in Figure 21.3 . Comparing the initial state to the goal state, this move seems unwise because it places the small disk on the bottom of the right peg, whereas it ultimately needs to be at the top of the tower on that peg. But comparing the initial state to the solver-generated subgoal state of having the medium disk on the middle peg, this is exactly where the small disk needs to go.

Means-ends analysis and various other heuristics (e.g., the hill-climbing heuristic that exploits the similarity, or distance, between the state generated by the next operator and the goal state; working backward from the goal state to the initial state) are flexible strategies that people often use to successfully solve a large variety of problems. However, the generality of these heuristics comes at a cost: They are relatively weak and fallible (e.g., in the means-ends solution to the problem of fixing a hole in a bucket, “Dear Liza” leads “Dear Henry” in a loop that ends back at the initial state; the lyrics of this famous song can be readily found on the Web). Hence, although people use general-purpose heuristics when they encounter novel problems, they replace them as soon as they acquire experience with and sufficient knowledge about the particular problem space (e.g., Anzai & Simon, 1979 ).

Despite the fruitfulness of this research agenda, it soon became evident that a fundamental weakness was that it minimized the importance of people's background knowledge. Of course, Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) were aware that problem solutions require relevant knowledge (e.g., the rules of logical proofs, or rules for stacking disks). Hence, in programming GPS, they supplemented every problem they modeled with the necessary background knowledge. This practice highlighted the generality and flexibility of means-ends analysis but failed to capture how people's background knowledge affects their solutions. As we discussed in the previous section, domain knowledge is likely to affect how people represent problems and, therefore, how they generate problem solutions. Moreover, as people gain experience solving problems in a particular knowledge domain (e.g., math, physics), they change their representations of these problems (e.g., Chi, Feltovich, & Glaser, 1981 ; Haverty, Koedinger, Klahr, & Alibali, 2000 ; Schoenfeld & Herrmann, 1982 ) and learn domain-specific heuristics (e.g., Polya, 1957 ; Schoenfeld, 1979 ) that trump the general-purpose strategies.

It is perhaps inevitable that the two traditions in problem-solving research—one emphasizing representation and the other emphasizing search strategies—would eventually come together. In the next section we review developments that led to this integration.

The Two Legacies Converge

Because Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) aimed to discover the strategies people use in searching for a solution, they investigated problems that minimized the impact of factors that tend to evoke differences in problem representations, of the sort documented by the Gestalt psychologists. In subsequent work, however, Simon and his collaborators showed that such factors are highly relevant to people's solutions of well-defined problems, and Simon ( 1986 ) incorporated these findings into the theoretical framework that views problem solving as search in a problem space.

In this section, we first describe illustrative examples of this work. We then describe research on insight solutions that incorporates ideas from the two legacies described in the previous sections.

Relevance of the Gestalt Ideas to the Solution of Search Problems

In this subsection we describe two lines of research by Simon and his colleagues, and by other researchers, that document the importance of perception and of background knowledge to the way people search for a problem solution. The first line of research used variants of relatively well-defined riddle problems that had the same structure (i.e., “problem isomorphs”) and, therefore, supposedly the same problem space. It documented that people's search depended on various perceptual and conceptual inferences they tended to draw from a specific instantiation of the problem's structure. The second line of research documented that people's search strategies crucially depend on their domain knowledge and on their prior experience with related problems.

Problem Isomorphs

Hayes and Simon ( 1977 ) used two variants of the Tower of Hanoi problem that, instead of disks and pegs, involved monsters and globes that differed in size (small, medium, and large). In both variants, the initial state had the small monster holding the large globe, the medium-sized monster holding the small globe, and the large monster holding the medium-sized globe. Moreover, in both variants the goal was for each monster to hold a globe proportionate to its own size. The only difference between the problems concerned the description of the operators. In one variant (“transfer”), subjects were told that the monsters could transfer the globes from one to another as long as they followed a set of rules, adapted from the rules in the original Tower of Hanoi problem (e.g., only one globe may be transferred at a time). In the other variant (“change”), subjects were told that the monsters could shrink and expand themselves according to a set of rules, which corresponded to the rules in the transfer version of the problem (e.g., only one monster may change its size at a time). Despite the isomorphism of the two variants, subjects conducted their search in two qualitatively different problem spaces, which led to solution times for the change variant being almost twice as long as those for the transfer variant. This difference arose because subjects could more readily envision and track an object that was changing its location with every move than one that was changing its size.

Recent work by Patsenko and Altmann ( 2010 ) found that, even in the standard Tower of Hanoi problem, people's solutions involve object-bound routines that depend on perception and selective attention. The subjects in their study solved various Tower of Hanoi problems on a computer. During the solution of a particular “critical” problem, the computer screen changed at various points without subjects' awareness (e.g., a disk was added, such that a subject who started with a five-disc tower ended with a six-disc tower). Patsenko and Altmann found that subjects' moves were guided by the configurations of the objects on the screen rather than by solution plans they had stored in memory (e.g., the next subgoal).

The Gestalt psychologists highlighted the role of perceptual factors in the formation of problem representations (e.g., Maier's, 1930 , nine-dot problem) but were generally silent about the corresponding implications for how the problem was solved (although they did note effects on solution accuracy). An important contribution of the work on people's solutions of the Tower of Hanoi problem and its variants was to show the relevance of perceptual factors to the application of various operators during search for a problem solution—that is, to the how of problem solving. In the next section, we describe recent work that documents the involvement of perceptual factors in how people understand and use equations and diagrams in the context of solving math and science problems.

Kotovsky, Hayes, and Simon ( 1985 ) further investigated factors that affect people's representation and search in isomorphs of the Tower of Hanoi problem. In one of their isomorphs, three disks were stacked on top of each other to form an inverted pyramid, with the smallest disc on the bottom and the largest on top. Subjects' solutions of the inverted pyramid version were similar to their solutions of the standard version that has the largest disc on the bottom and the smallest on top. However, the two versions were solved very differently when subjects were told that the discs represent acrobats. Subjects readily solved the version in which they had to place a small acrobat on the shoulders of a large one, but they refrained from letting a large acrobat stand on the shoulders of a small one. In other words, object-based inferences that draw on people's semantic knowledge affected the solution of search problems, much as they affect the solution of the ill-defined problems investigated by the Gestalt psychologists (e.g., Duncker's, 1945 , candles problem). In the next section, we describe more recent work that shows similar effects in people's solutions to mathematical word problems.

The work on differences in the representation and solution of problem isomorphs is highly relevant to research on analogical problem solving (or analogical transfer), which examines when and how people realize that two problems that differ in their cover stories have a similar structure (or a similar problem space) and, therefore, can be solved in a similar way. This research shows that minor differences between example problems, such as the use of X-rays versus ultrasound waves to fuse a broken filament of a light bulb, can elicit different problem representations that significantly affect the likelihood of subsequent transfer to novel problem analogs (Holyoak & Koh, 1987 ). Analogical transfer has played a central role in research on human problem solving, in part because it can shed light on people's understanding of a given problem and its solution and in part because it is believed to provide a window onto understanding and investigating creativity (see Smith & Ward, Chapter 23 ). We briefly mention some findings from the analogy literature in the next subsection on expertise, but we do not discuss analogical transfer in detail because this topic is covered elsewhere in this volume (Holyoak, Chapter 13 ).

Expertise and Its Development

In another line of research, Simon and his colleagues examined how people solve ecologically valid problems from various rule-governed and knowledge-rich domains. They found that people's level of expertise in such domains, be it in chess (Chase & Simon, 1973 ; Gobet & Simon, 1996 ), mathematics (Hinsley, Hayes, & Simon, 1977 ; Paige & Simon, 1966 ), or physics (Larkin, McDermott, Simon, & Simon, 1980 ; Simon & Simon, 1978 ), plays a crucial role in how they represent problems and search for solutions. This work, and the work of numerous other researchers, led to the discovery (and rediscovery, see Duncker, 1945 ) of important differences between experts and novices, and between “good” and “poor” students.

One difference between experts and novices pertains to pattern recognition. Experts' attention is quickly captured by familiar configurations within a problem situation (e.g., a familiar configuration of pieces in a chess game). In contrast, novices' attention is focused on isolated components of the problem (e.g., individual chess pieces). This difference, which has been found in numerous domains, indicates that experts have stored in memory many meaningful groups (chunks) of information: for example, chess (Chase & Simon, 1973 ), circuit diagrams (Egan & Schwartz, 1979 ), computer programs (McKeithen, Reitman, Rueter, & Hirtle, 1981 ), medicine (Coughlin & Patel, 1987 ; Myles-Worsley, Johnston, & Simons, 1988 ), basketball and field hockey (Allard & Starkes, 1991 ), and figure skating (Deakin & Allard, 1991 ).

The perceptual configurations that domain experts readily recognize are associated with stored solution plans and/or compiled procedures (Anderson, 1982 ). As a result, experts' solutions are much faster than, and often qualitatively different from, the piecemeal solutions that novice solvers tend to construct (e.g., Larkin et al., 1980 ). In effect, experts often see the solutions that novices have yet to compute (e.g., Chase & Simon, 1973 ; Novick & Sherman, 2003 , 2008 ). These findings have led to the design of various successful instructional interventions (e.g., Catrambone, 1998 ; Kellman et al., 2008 ). For example, Catrambone ( 1998 ) perceptually isolated the subgoals of a statistics problem. This perceptual chunking of meaningful components of the problem prompted novice students to self-explain the meaning of the chunks, leading to a conceptual understanding of the learned solution. In the next section, we describe some recent work that shows the beneficial effects of perceptual pattern recognition on the solution of familiar mathematics problems, as well as the potentially detrimental effects of familiar perceptual chunks to understanding and reasoning with diagrams depicting evolutionary relationships among taxa.

Another difference between experts and novices pertains to their understanding of the solution-relevant problem structure. Experts' knowledge is highly organized around domain principles, and their problem representations tend to reflect this principled understanding. In particular, they can extract the solution-relevant structure of the problems they encounter (e.g., meaningful causal relations among the objects in the problem; see Cheng & Buehner, Chapter 12 ). In contrast, novices' representations tend to be bound to surface features of the problems that may be irrelevant to solution (e.g., the particular objects in a problem). For example, Chi, Feltovich, and Glaser ( 1981 ) examined how students with different levels of physics expertise group mechanics word problems. They found that advanced graduate students grouped the problems based on the physics principles relevant to the problems' solutions (e.g., conservation of energy, Newton's second law). In contrast, undergraduates who had successfully completed an introductory course in mechanics grouped the problems based on the specific objects involved (e.g., pulley problems, inclined plane problems). Other researchers have found similar results in the domains of biology, chemistry, computer programming, and math (Adelson, 1981 ; Kindfield, 1993 / 1994 ; Kozma & Russell, 1997 ; McKeithen et al., 1981 ; Silver, 1979 , 1981 ; Weiser & Shertz, 1983 ).

The level of domain expertise and the corresponding representational differences are, of course, a matter of degree. With increasing expertise, there is a gradual change in people's focus of attention from aspects that are not relevant to solution to those that are (e.g., Deakin & Allard, 1991 ; Hardiman, Dufresne, & Mestre, 1989 ; McKeithen et al., 1981 ; Myles-Worsley et al., 1988 ; Schoenfeld & Herrmann, 1982 ; Silver, 1981 ). Interestingly, Chi, Bassok, Lewis, Reimann, and Glaser ( 1989 ) found similar differences in focus on structural versus surface features among a group of novices who studied worked-out examples of mechanics problems. These differences, which echo Wertheimer's ( 1959 ) observations of individual differences in students' learning about the area of parallelograms, suggest that individual differences in people's interests and natural abilities may affect whether, or how quickly, they acquire domain expertise.

An important benefit of experts' ability to focus their attention on solution-relevant aspects of problems is that they are more likely than novices to recognize analogous problems that involve different objects and cover stories (e.g., Chi et al., 1989 ; Novick, 1988 ; Novick & Holyoak, 1991 ; Wertheimer, 1959 ) or that come from other knowledge domains (e.g., Bassok & Holyoak, 1989 ; Dunbar, 2001 ; Goldstone & Sakamoto, 2003 ). For example, Bassok and Holyoak ( 1989 ) found that, after learning to solve arithmetic-progression problems in algebra, subjects spontaneously applied these algebraic solutions to analogous physics problems that dealt with constantly accelerated motion. Note, however, that experts and good students do not simply ignore the surface features of problems. Rather, as was the case in the problem isomorphs we described earlier (Kotovsky et al., 1985 ), they tend to use such features to infer what the problem's structure could be (e.g., Alibali, Bassok, Solomon, Syc, & Goldin-Meadow, 1999 ; Blessing & Ross, 1996 ). For example, Hinsley et al. ( 1977 ) found that, after reading no more than the first few words of an algebra word problem, expert solvers classified the problem into a likely problem category (e.g., a work problem, a distance problem) and could predict what questions they might be asked and the equations they likely would need to use.

Surface-based problem categorization has a heuristic value (Medin & Ross, 1989 ): It does not ensure a correct categorization (Blessing & Ross, 1996 ), but it does allow solvers to retrieve potentially appropriate solutions from memory and to use them, possibly with some adaptation, to solve a variety of novel problems. Indeed, although experts exploit surface-structure correlations to save cognitive effort, they have the capability to realize that a particular surface cue is misleading (Hegarty, Mayer, & Green, 1992 ; Lewis & Mayer, 1987 ; Martin & Bassok, 2005 ; Novick 1988 , 1995 ; Novick & Holyoak, 1991 ). It is not surprising, therefore, that experts may revert to novice-like heuristic methods when solving problems under pressure (e.g., Beilock, 2008 ) or in subdomains in which they have general but not specific expertise (e.g., Patel, Groen, & Arocha, 1990 ).

Relevance of Search to Insight Solutions

We introduced the notion of insight in our discussion of the nine-dot problem in the section on the Gestalt tradition. The Gestalt view (e.g., Duncker, 1945 ; Maier, 1931 ; see Ohlsson, 1984 , for a review) was that insight problem solving is characterized by an initial work period during which no progress toward solution is made (i.e., an impasse), a sudden restructuring of one's problem representation to a more suitable form, followed immediately by the sudden appearance of the solution. Thus, solving problems by insight was believed to be all about representation, with essentially no role for a step-by-step solution process (i.e., search). Subsequent and contemporary researchers have generally concurred with the Gestalt view that getting the right representation is crucial. However, research has shown that insight solutions do not necessarily arise suddenly or full blown after restructuring (e.g., Weisberg & Alba, 1981 ); and even when they do, the underlying solution process (in this case outside of awareness) may reflect incremental progress toward the goal (Bowden & Jung-Beeman, 2003 ; Durso, Rea, & Dayton, 1994 ; Novick & Sherman, 2003 ).

“Demystifying insight,” to borrow a phrase from Bowden, Jung-Beeman, Fleck, and Kounios ( 2005 ), requires explaining ( 1 ) why solvers initially reach an impasse in solving a problem for which they have the necessary knowledge to generate the solution, ( 2 ) how the restructuring occurred, and ( 3 ) how it led to the solution. A detailed discussion of these topics appears elsewhere in this volume (van Steenburgh et al., Chapter 24 ). Here, we describe briefly three recent theories that have attempted to account for various aspects of these phenomena: Knoblich, Ohlsson, Haider, and Rhenius's ( 1999 ) representational change theory, MacGregor, Ormerod, and Chronicle's ( 2001 ) progress monitoring theory, and Bowden et al.'s ( 2005 ) neurological model. We then propose the need for an integrated approach to demystifying insight that considers both representation and search.

According to Knoblich et al.'s ( 1999 ) representational change theory, problems that are solved with insight are highly likely to evoke initial representations in which solvers place inappropriate constraints on their solution attempts, leading to an impasse. An impasse can be resolved by revising one's representation of the problem. Knoblich and his colleagues tested this theory using Roman numeral matchstick arithmetic problems in which solvers must move one stick to a new location to change a false numerical statement (e.g., I = II + II ) into a statement that is true. According to representational change theory, re-representation may occur through either constraint relaxation or chunk decomposition. (The solution to the example problem is to change II + to III – , which requires both methods of re-representation, yielding I = III – II ). Good support for this theory has been found based on measures of solution rate, solution time, and eye fixation (Knoblich et al., 1999 ; Knoblich, Ohlsson, & Raney, 2001 ; Öllinger, Jones, & Knoblich, 2008 ).

Progress monitoring theory (MacGregor et al., 2001 ) was proposed to account for subjects' difficulty in solving the nine-dot problem, which has traditionally been classified as an insight problem. According to this theory, solvers use the hill-climbing search heuristic to solve this problem, just as they do for traditional search problems (e.g., Hobbits and Orcs). In particular, solvers are hypothesized to monitor their progress toward solution using a criterion generated from the problem's current state. If solvers reach criterion failure, they seek alternative solutions by trying to relax one or more problem constraints. MacGregor et al. found support for this theory using several variants of the nine-dot problem (also see Ormerod, MacGregor, & Chronicle, 2002 ). Jones ( 2003 ) suggested that progress monitoring theory provides an account of the solution process up to the point an impasse is reached and representational change is sought, at which point representational change theory picks up and explains how insight may be achieved. Hence, it appears that a complete account of insight may require an integration of concepts from the Gestalt (representation) and Newell and Simon's (search) legacies.

Bowden et al.'s ( 2005 ) neurological model emphasizes the overlap between problem solving and language comprehension, and it hinges on differential processing in the right and left hemispheres. They proposed that an impasse is reached because initial processing of the problem produces strong activation of information irrelevant to solution in the left hemisphere. At the same time, weak semantic activation of alternative semantic interpretations, critical for solution, occurs in the right hemisphere. Insight arises when the weakly activated concepts reinforce each other, eventually rising above the threshold required for conscious awareness. Several studies of problem solving using compound remote associates problems, involving both behavioral and neuroimaging data, have found support for this model (Bowden & Jung-Beeman, 1998 , 2003 ; Jung-Beeman & Bowden, 2000 ; Jung-Beeman et al., 2004 ; also see Moss, Kotovsky, & Cagan, 2011 ).

Note that these three views of insight have received support using three quite distinct types of problems (Roman numeral matchstick arithmetic problems, the nine-dot problem, and compound remote associates problems, respectively). It remains to be established, therefore, whether these accounts can be generalized across problems. Kershaw and Ohlsson ( 2004 ) argued that insight problems are difficult because the key behavior required for solution may be hindered by perceptual factors (the Gestalt view), background knowledge (so expertise may be important; e.g., see Novick & Sherman, 2003 , 2008 ), and/or process factors (e.g., those affecting search). From this perspective, solving visual problems (e.g., the nine-dot problem) with insight may call upon more general visual processes, whereas solving verbal problems (e.g., anagrams, compound remote associates) with insight may call upon general verbal/semantic processes.

The work we reviewed in this section shows the relevance of problem representation (the Gestalt legacy) to the way people search the problem space (the legacy of Newell and Simon), and the relevance of search to the solution of insight problems that require a representational change. In addition to this inevitable integration of the two legacies, the work we described here underscores the fact that problem solving crucially depends on perceptual factors and on the solvers' background knowledge. In the next section, we describe some recent work that shows the involvement of these factors in the solution of problems in math and science.

Effects of Perception and Knowledge in Problem Solving in Academic Disciplines

Although the use of puzzle problems continues in research on problem solving, especially in investigations of insight, many contemporary researchers tackle problem solving in knowledge-rich domains, often in academic disciplines (e.g., mathematics, biology, physics, chemistry, meteorology). In this section, we provide a sampling of this research that highlights the importance of visual perception and background knowledge for successful problem solving.

The Role of Visual Perception

We stated at the outset that a problem representation (e.g., the problem space) is a model of the problem constructed by solvers to summarize their understanding of the problem's essential nature. This informal definition refers to the internal representations people construct and hold in working memory. Of course, people may also construct various external representations (Markman, 1999 ) and even manipulate those representations to aid in solution (see Hegarty & Stull, Chapter 31 ). For example, solvers often use paper and pencil to write notes or draw diagrams, especially when solving problems from formal domains (e.g., Cox, 1999 ; Kindfield, 1993 / 1994 ; S. Schwartz, 1971 ). In problems that provide solvers with external representation, such as the Tower of Hanoi problem, people's planning and memory of the current state is guided by the actual configurations of disks on pegs (Garber & Goldin-Meadow, 2002 ) or by the displays they see on a computer screen (Chen & Holyoak, 2010 ; Patsenko & Altmann, 2010 ).

In STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) disciplines, it is common for problems to be accompanied by diagrams or other external representations (e.g., equations) to be used in determining the solution. Larkin and Simon ( 1987 ) examined whether isomorphic sentential and diagrammatic representations are interchangeable in terms of facilitating solution. They argued that although the two formats may be equivalent in the sense that all of the information in each format can be inferred from the other format (informational equivalence), the ease or speed of making inferences from the two formats might differ (lack of computational equivalence). Based on their analysis of several problems in physics and math, Larkin and Simon further argued for the general superiority of diagrammatic representations (but see Mayer & Gallini, 1990 , for constraints on this general conclusion).

Novick and Hurley ( 2001 , p. 221) succinctly summarized the reasons for the general superiority of diagrams (especially abstract or schematic diagrams) over verbal representations: They “(a) simplify complex situations by discarding unnecessary details (e.g., Lynch, 1990 ; Winn, 1989 ), (b) make abstract concepts more concrete by mapping them onto spatial layouts with familiar interpretational conventions (e.g., Winn, 1989 ), and (c) substitute easier perceptual inferences for more computationally intensive search processes and sentential deductive inferences (Barwise & Etchemendy, 1991 ; Larkin & Simon, 1987 ).” Despite these benefits of diagrammatic representations, there is an important caveat, noted by Larkin and Simon ( 1987 , p. 99) at the very end of their paper: “Although every diagram supports some easy perceptual inferences, nothing ensures that these inferences must be useful in the problem-solving process.” We will see evidence of this in several of the studies reviewed in this section.

Next we describe recent work on perceptual factors that are involved in people's use of two types of external representations that are provided as part of the problem in two STEM disciplines: equations in algebra and diagrams in evolutionary biology. Although we focus here on effects of perceptual factors per se, it is important to note that such factors only influence performance when subjects have background knowledge that supports differential interpretation of the alternative diagrammatic depictions presented (Hegarty, Canham, & Fabricant, 2010 ).