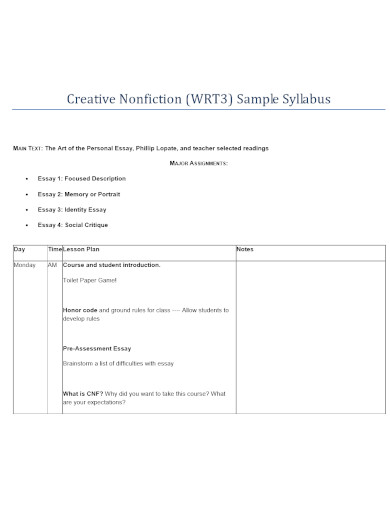

A Guide to Writing Creative Nonfiction

by Melissa Donovan | Mar 4, 2021 | Creative Writing | 12 comments

Try your hand at writing creative nonfiction.

Here at Writing Forward, we’re primarily interested in three types of creative writing: poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction.

With poetry and fiction, there are techniques and best practices that we can use to inform and shape our writing, but there aren’t many rules beyond the standards of style, grammar, and good writing . We can let our imaginations run wild; everything from nonsense to outrageous fantasy is fair game for bringing our ideas to life when we’re writing fiction and poetry.

However, when writing creative nonfiction, there are some guidelines that we need to follow. These guidelines aren’t set in stone; however, if you violate them, you might find yourself in trouble with your readers as well as the critics.

What is Creative Nonfiction?

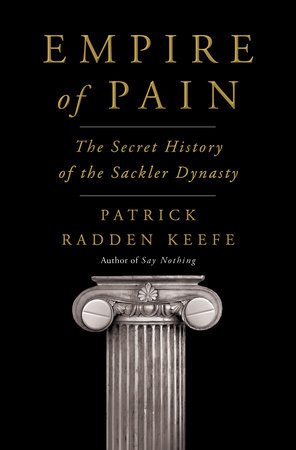

Telling True Stories (aff link).

What sets creative nonfiction apart from fiction or poetry?

For starters, creative nonfiction is factual. A memoir is not just any story; it’s a true story. A biography is the real account of someone’s life. There is no room in creative nonfiction for fabrication or manipulation of the facts.

So what makes creative nonfiction writing different from something like textbook writing or technical writing? What makes it creative?

Nonfiction writing that isn’t considered creative usually has business or academic applications. Such writing isn’t designed for entertainment or enjoyment. Its sole purpose is to convey information, usually in a dry, straightforward manner.

Creative nonfiction, on the other hand, pays credence to the craft of writing, often through literary devices and storytelling techniques, which make the prose aesthetically pleasing and bring layers of meaning to the context. It’s pleasurable to read.

According to Wikipedia:

Creative nonfiction (also known as literary or narrative nonfiction) is a genre of writing truth which uses literary styles and techniques to create factually accurate narratives. Creative nonfiction contrasts with other nonfiction, such as technical writing or journalism, which is also rooted in accurate fact, but is not primarily written in service to its craft.

Like other forms of nonfiction, creative nonfiction relies on research, facts, and credibility. While opinions may be interjected, and often the work depends on the author’s own memories (as is the case with memoirs and autobiographies), the material must be verifiable and accurately reported.

Creative Nonfiction Genres and Forms

There are many forms and genres within creative nonfiction:

- Autobiography and biography

- Personal essays

- Literary journalism

- Any topical material, such as food or travel writing, self-development, art, or history, can be creatively written with a literary angle

Let’s look more closely at a few of these nonfiction forms and genres:

Memoirs: A memoir is a long-form (book-length) written work. It is a firsthand, personal account that focuses on a specific experience or situation. One might write a memoir about serving in the military or struggling with loss. Memoirs are not life stories, but they do examine life through a particular lens. For example, a memoir about being a writer might begin in childhood, when the author first learned to write. However, the focus of the book would be on writing, so other aspects of the author’s life would be left out, for the most part.

Biographies and autobiographies: A biography is the true story of someone’s life. If an author composes their own biography, then it’s called an autobiography. These works tend to cover the entirety of a person’s life, albeit selectively.

Literary journalism: Journalism sticks with the facts while exploring the who, what, where, when, why, and how of a particular person, topic, or event. Biographies, for example, are a genre of literary journalism, which is a form of nonfiction writing. Traditional journalism is a method of information collection and organization. Literary journalism also conveys facts and information, but it honors the craft of writing by incorporating storytelling techniques and literary devices. Opinions are supposed to be absent in traditional journalism, but they are often found in literary journalism, which can be written in long or short formats.

Personal essays are a short form of creative nonfiction that can cover a wide range of styles, from writing about one’s experiences to expressing one’s personal opinions. They can address any topic imaginable. Personal essays can be found in many places, from magazines and literary journals to blogs and newspapers. They are often a short form of memoir writing.

Speeches can cover a range of genres, from political to motivational to educational. A tributary speech honors someone whereas a roast ridicules them (in good humor). Unlike most other forms of writing, speeches are written to be performed rather than read.

Journaling: A common, accessible, and often personal form of creative nonfiction writing is journaling. A journal can also contain fiction and poetry, but most journals would be considered nonfiction. Some common types of written journals are diaries, gratitude journals, and career journals (or logs), but this is just a small sampling of journaling options.

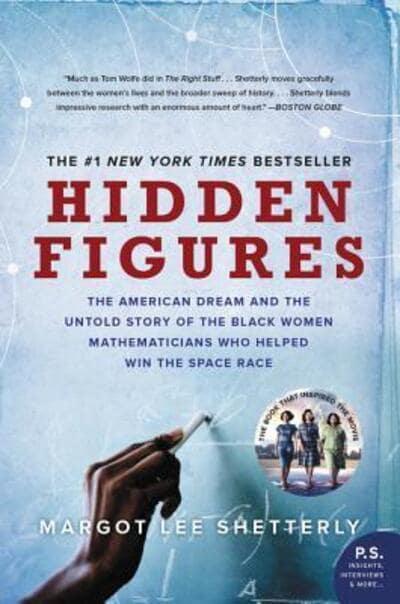

Writing Creative Nonfiction (aff link).

Any topic or subject matter is fair game in the realm of creative nonfiction. Some nonfiction genres and topics that offer opportunities for creative nonfiction writing include food and travel writing, self-development, art and history, and health and fitness. It’s not so much the topic or subject matter that renders a written work as creative; it’s how it’s written — with due diligence to the craft of writing through application of language and literary devices.

Guidelines for Writing Creative Nonfiction

Here are six simple guidelines to follow when writing creative nonfiction:

- Get your facts straight. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing your own story or someone else’s. If readers, publishers, and the media find out you’ve taken liberties with the truth of what happened, you and your work will be scrutinized. Negative publicity might boost sales, but it will tarnish your reputation; you’ll lose credibility. If you can’t refrain from fabrication, then think about writing fiction instead of creative nonfiction.

- Issue a disclaimer. A lot of nonfiction is written from memory, and we all know that human memory is deeply flawed. It’s almost impossible to recall a conversation word for word. You might forget minor details, like the color of a dress or the make and model of a car. If you aren’t sure about the details but are determined to include them, be upfront and include a disclaimer that clarifies the creative liberties you’ve taken.

- Consider the repercussions. If you’re writing about other people (even if they are secondary figures), you might want to check with them before you publish your nonfiction. Some people are extremely private and don’t want any details of their lives published. Others might request that you leave certain things out, which they want to keep private. Otherwise, make sure you’ve weighed the repercussions of revealing other people’s lives to the world. Relationships have been both strengthened and destroyed as a result of authors publishing the details of other people’s lives.

- Be objective. You don’t need to be overly objective if you’re telling your own, personal story. However, nobody wants to read a highly biased biography. Book reviews for biographies are packed with harsh criticism for authors who didn’t fact-check or provide references and for those who leave out important information or pick and choose which details to include to make the subject look good or bad.

- Pay attention to language. You’re not writing a textbook, so make full use of language, literary devices, and storytelling techniques.

- Know your audience. Creative nonfiction sells, but you must have an interested audience. A memoir about an ordinary person’s first year of college isn’t especially interesting. Who’s going to read it? However, a memoir about someone with a learning disability navigating the first year of college is quite compelling, and there’s an identifiable audience for it. When writing creative nonfiction, a clearly defined audience is essential.

Are you looking for inspiration? Check out these creative nonfiction writing ideas.

Ten creative nonfiction writing prompts and projects.

The prompts below are excerpted from my book, 1200 Creative Writing Prompts , which contains fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction writing prompts. Use these prompts to spark a creative nonfiction writing session.

1200 Creative Writing Prompts (aff link).

- What is your favorite season? What do you like about it? Write a descriptive essay about it.

- What do you think the world of technology will look like in ten years? Twenty? What kind of computers, phones, and other devices will we use? Will technology improve travel? Health care? What do you expect will happen and what would you like to happen?

- Have you ever fixed something that was broken? Ever solved a computer problem on your own? Write an article about how to fix something or solve some problem.

- Have you ever had a run-in with the police? What happened?

- Have you ever traveled alone? Tell your story. Where did you go? Why? What happened?

- Let’s say you write a weekly advice column. Choose the topic you’d offer advice on, and then write one week’s column.

- Think of a major worldwide problem: for example, hunger, climate change, or political corruption. Write an article outlining a solution (or steps toward a solution).

- Choose a cause that you feel is worthy and write an article persuading others to join that cause.

- Someone you barely know asks you to recommend a book. What do you recommend and why?

- Hard skills are abilities you have acquired, such as using software, analyzing numbers, and cooking. Choose a hard skill you’ve mastered and write an article about how this skill is beneficial using your own life experiences as examples.

Do You Write Creative Nonfiction?

Have you ever written creative nonfiction? How often do you read it? Can you think of any nonfiction forms and genres that aren’t included here? Do you have any guidelines to add to this list? Are there any situations in which it would be acceptable to ignore these guidelines? Got any tips to add? Do you feel that nonfiction should focus on content and not on craft? Leave a comment to share your thoughts, and keep writing.

12 Comments

Shouldn’t ALL non-fiction be creative to some extent? I am a former business journalist, and won awards for the imaginative approach I took to writing about even the driest of business topics: pensions, venture capital, tax, employment law and other potentially dusty subjects. The drier and more complicated the topic, the more creative the approach must be, otherwise no-one with anything else to do will bother to wade through it. [to be honest, taking the fictional approach to these ghastly tortuous topics was the only way I could face writing about them.] I used all the techniques that fiction writers have to play with, and used some poetic techniques, too, to make the prose more readable. What won the first award was a little serial about two businesses run and owned by a large family at war with itself. Every episode centred on one or two common and crucial business issues, wrapped up in a comedy-drama, and it won a lot of fans (happily for me) because it was so much easier to read and understand than the dry technical writing they were used to. Life’s too short for dusty writing!

I believe most journalism is creative and would therefore fall under creative nonfiction. However, there is a lot of legal, technical, medical, science, and textbook writing in which there is no room for creativity (or creativity has not made its way into these genres yet). With some forms, it makes sense. I don’t think it would be appropriate for legal briefings to use story or literary devices just to add a little flair. On the other hand, it would be a good thing if textbooks were a little more readable.

I think Abbs is right – even in academic papers, an example or story helps the reader visualize the problem or explanation more easily. I scan business books to see if there are stories or examples, if not, then I don’t pick up the book. That’s where the creativity comes in – how to create examples, what to conflate, what to emphasis as we create our fictional people to illustrate important, real points.

Thanks for the post. Very helpful. I’d never thought about writing creative nonfiction before.

You’re welcome 🙂

Hi Melissa!

Love your website. You always give a fun and frank assessment of all things pertaining to writing. It is a pleasure to read. I have even bought several of the reference and writing books you recommended. Keep up the great work.

Top 10 Reasons Why Creative Nonfiction Is A Questionable Category

10. When you look up “Creative Nonfiction” in the dictionary it reads: See Fiction

9. The first creative nonfiction example was a Schwinn Bicycle Assembly Guide that had printed in its instructions: Can easily be assembled by one person with a Phillips head screw driver, Allen keys, adjustable wrench and cable cutters in less than an hour.

8. Creative Nonfiction; Based on actual events; Suggested by a true event; Based on a true story. It’s a slippery slope.

7. The Creative Nonfiction Quarterly is only read by eleven people. Five have the same last name.

6. Creative Nonfiction settings may only include: hospitals, concentration camps, prisons and cemeteries. Exceptions may be made for asylums, rehab centers and Capitol Hill.

5. The writers who create Sterile Nonfiction or Unimaginative Nonfiction now want their category recognized.

4. Creative; Poetic License; Embellishment; Puffery. See where this is leading?

3. Creative Nonfiction is to Nonfiction as Reality TV is to Documentaries.

2. My attorney has advised that I exercise my 5th Amendment Rights or that I be allowed to give written testimony in a creative nonfiction way.

1. People believe it is a film with Will Ferrell, Emma Thompson and Queen Latifa.

Hi Steve. I’m not sure if your comment is meant to be taken tongue-in-cheek, but I found it humorous.

My publisher is releasing my Creative Nonfiction book based on my grandmother’s life this May 2019 in Waikiki. I’ll give you an update soon about sales. I was fortunate enough to get some of the original and current Hawaii 5-0 members to show up for the book signing.

Hi, when writing creative nonfiction- is it appropriate to write from someone else’s point of view when you don’t know them? I was thinking of writing about Greta Thungbrurg for creative nonfiction competition – but I can directly ask her questions so I’m unsure as to whether it’s accurate enough to be classified as creative non-fiction. Thank you!

Hi Madeleine. I’m not aware of creative nonfiction being written in first person from someone else’s point of view. The fact of the matter is that it wouldn’t be creative nonfiction because a person cannot truly show events from another person’s perspective. So I wouldn’t consider something like that nonfiction. It would usually be a biography written in third person, and that is common. You can certainly use quotes and other indicators to represent someone else’s views and experiences. I could probably be more specific if I knew what kind of work it is (memoir, biography, self-development, etc.).

Dear Melissa: I am trying to market a book in the metaphysical genre about an experience I had, receiving the voice of a Civil War spirit who tells his story (not channeling). Part is my reaction and discussion with a close friend so it is not just memoir. I referred to it as ‘literary non-fiction’ but an agent put this down by saying it is NOT literary non-fiction. Looking at your post, could I say that my book is ‘creative non-fiction’? (agents can sometimes be so nit-picky)

Hi Liz. You opened your comment by classifying the book as metaphysical but later referred to it as literary nonfiction. The premise definitely sounds like a better fit in the metaphysical category. Creative nonfiction is not a genre; it’s a broader category or description. Basically, all literature is either fiction or nonfiction (poetry would be separate from these). Describing nonfiction as creative only indicates that it’s not something like a user guide. I think you were heading in the right direction with the metaphysical classification.

The goal of marketing and labeling books with genres is to find a readership that will be interested in the work. This is an agent’s area of expertise, so assuming you’re speaking with a competent agent, I’d suggest taking their advice in this matter. It indicates that the audience perusing the literary nonfiction aisles is simply not a match for this book.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Top Picks Thursday! For Writers & Readers 03-11-2021 | The Author Chronicles - […] If your interests leans toward nonfiction, Melissa Donovan presents a guide to writing creative nonfiction. […]

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe and get The Writer’s Creed graphic e-booklet, plus a weekly digest with the latest articles on writing, as well as special offers and exclusive content.

Recent Posts

- Consuming Art to Fuel Your Writing

- How to Improve Your Writing

- Writing Tips: Be Yourself

- A Must-Read for Storytellers: Save the Cat

- Poetry Prompts for Language Lovers

Write on, shine on!

Pin It on Pinterest

- All Editing

- Manuscript Assessment

- Developmental editing: use our editors to perfect your book

- Copy Editing

- Agent Submission Pack: perfect your query letter & synopsis

- Our Editors

- All Courses

- Ultimate Novel Writing Course

- Simply Self-Publish: The Ultimate Self-Pub Course for Indies

- Self-Edit Your Novel: Edit Your Own Manuscript

- Jumpstart Your Novel: How To Start Writing A Book

- Creativity For Writers: How To Find Inspiration

- Edit Your Novel the Professional Way

- All Mentoring

- Agent One-to-Ones

- London Festival of Writing

- Pitch Jericho Competition

- Online Events

- Getting Published Month

- Build Your Book Month

- Meet the Team

- Work with us

- Success Stories

- Novel writing

- Publishing industry

- Self-publishing

- Success stories

- Writing Tips

- Featured Posts

- Get started for free

- About Membership

- Upcoming Events

- Video Courses

Non-fiction/Poetry ,

How to write creative nonfiction that engages your readers.

By Sonia Grant

When I read Dancing in the Dark by Caryl Philips, I wasn’t quite sure what I was reading, as it was unlike any novel I’d read previously. But I was curious how the author crafted the “voices” or dialogue , which were so finely tuned and authentic it made me feel as though I was in the thick of the plot as it unfolded. Eventually, it dawned on me that the book couldn’t solely be classified as a novel per se, as the story was based on “real life”; because of its biographical and historical context it sat comfortably within the genre of creative nonfiction.

What Is Creative Nonfiction ?

The term creative nonfiction has been credited to American writer Lee Gutkin, who first coined the phrase in the journal he founded in 1993: Creative Nonfiction . When asked to define what creative nonfiction is Gutkin says simply “true stories well told.”

Expanding on Gutkin’s definition I would add that the main difference between creative nonfiction – also known as narrative nonfiction – and other genres is that in creative nonfiction the focus is on literary style, and it is very much like reading a novel, with the important exception that everything in the story has actually happened.

Essentially, creative nonfiction incorporates techniques from literature, including fiction and poetry, in order to present a narrative that flows more like story than, say, a journalistic article or a report. In short, then, it is a form of storytelling that employs creative writing techniques including literature to retell a true story, which is why emphasis is placed on the word creative . I would underscore that it is this aspect which distinguishes the genre from other nonfiction books; for instance, textbooks which are, as implied, recounting solely of facts – without any frills.

Types Of Creative Nonfiction

The good news is that the expanse of creative nonfiction as a genre is considerable and there is ample scope for writers of every persuasion, in terms of categorisation and personal creative preference. Some terms you may be familiar with, and some are essentially the same, as far as content is concerned – only the phrasing may be interchangeable.

Memoirs are the most commonly used form of creative nonfiction. It is a writer’s personal, first-hand experiences, or events spanning a specific time frame or period. In it you are essentially trying to evoke the past… and by the end you will, no doubt, hope to have successfully conveyed the moral of your story. Not in a preachy kind of way but in a manner which is engaging, informative or entertaining.

You should note that there are important differences between a biography and a memoir: in writing a biography you need to maintain a record of your sources – primary or secondary – that will stand the rigours of being fact-checked.

A memoir, by contrast, is your recollection or memory of a past event or experience. While they do not necessarily have to be underpinned with verifiable facts in the same way as a biography, there’s more scope for your creative or imaginary interpretation of an event or experience.

Literary Journalism

In the early days of the genre literary journalism hogged the headlines; it was, according to The Herald Tribune , “a hotbed of so-called New Journalism, in which writers like Tom Wolfe used the tools of novelists — characters, dialogue and scene-setting — to create compelling narratives.” The way this fits into the creative nonfiction genre is that it uses the style and devices of literary fiction in fact-based journalism. Norman Mailer and Gail Sheehy were exceptionally skilled exponents, though, arguably, critics contended that both could, on occasion, be so immersed that some of their writing was tantamount to an actor who inhabited their character via method acting.

Reportage And Reporting

Ultimately, the primary goal of the creative nonfiction writer is to communicate information, just like a reporter. If you choose to pursue reportage it is imperative that you pay close attention to notes and record-keeping as reporting is not – as with other elements of creative nonfiction – based on your personal experiences or opinions and, therefore, has to be scrupulously accurate and verifiable.

Personal Essays

Other types of creative nonfiction include personal essays whereby the writer crafts an essay that’s based on a personal experience or single event, which results in significant personal resonance, or a lesson learned. This element of creative nonfiction is very broad in scope and includes travel writing , food writing, nature writing, science writing, sports writing, and magazine articles.

Personal essays, therefore, encompass just about any kind of writing. They can also include audio creativity and opinion pieces, through podcasts and radio plays.

The Five R’s Of Creative Nonfiction

In Lee Gutkind’s essay, The Five R’s of Creative Nonfiction , he summarised the salient points of successfully writing creative nonfiction and, if you followed these instructions, you’d be hard-pressed to go wrong:

1. Real Life

I daresay this is self-explanatory although as a storyteller, instead of letting your imagination run riot you must use it as the foundation. Your story must be based in reality – be that subject matter, people, situations or experiences.

2. Research

I can’t emphasise strongly enough that conducting extensive, thorough research is of paramount importance and, not to put too fine a point on it, this is not an area you can gloss over – you will be “found out” and your credibility is at stake. And, no, Wikipedia doesn’t count – other than perhaps as a starting point. Interestingly, by the company’s own admission: “Wikipedia is not a reliable source for citations elsewhere on Wikipedia. Because it can be edited by anyone at any time, any information it contains at a particular time could be vandalism , a work in progress, or just plain wrong.”

Not technically an “R” but we get his point… Put succinctly by William Faulkner: “Get it down. Take chances. It may be bad, but it’s the only way you can do anything good.”

4. Reflection

No-one can negate your personal reflections, but you should be aware, given that what you’re writing is based on “fact” that someone mentioned in your article or book may not necessarily agree with your perspective. The fallout can be devastating and damage irreparable. A case in point was the debacle following publication of Ugly: The True Story of a Loveless Childhood by Constance Briscoe. In the best-selling “misery memoir” the author accused her mother of childhood cruelty and neglect; her mother rejected the claims and said the allegations were “a piece of fiction” and sued both her daughter and publisher for libel , and lost.

It goes without saying that when writing about people who are still alive you need to be especially cautious. Of course, you’re entitled to your own unique perspective but, as Buckingham Palace responded to the Oprah Winfrey interview with Meghan Markle and Prince Harry – which may yet find its way in book form – “some recollections may vary”.

It’s often said that the best writers are also voracious readers. Not only does it broaden your horizons but it’s a perfect way to see what works and what doesn’t. And, as William Faulkner admonished: “Read, read, read. Read everything –trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it. Then write. If it’s good, you’ll find out. If it’s not, throw it out of the window.”

How To Write Creative Nonfiction

We now know what kind of creative nonfiction exists, and what to bear in mind before writing, but when it comes to starting your story…where do you begin?

While it may be tempting to jump straight in and start writing, you will save yourself a headache if you begin by deciding upon the structure or form you want your work to be based on. This doesn’t need big whistles and bells, you just need an outline to begin with, something to shape your thinking and trajectory. It’s always worthwhile to know what direction you’re headed in. Nothing is set in stone – you can always add to it or amend accordingly.

For planning there are different models you can employ but I find it easiest to think along the lines of a three-part play: act one, I open by establishing the fundamentals of what I am going to present; act two, allows me to build upon the opening by increasing the dramatic effect of what’s unfolding; and act three, I bring my thesis together by pulling together different strands of the story to a logical, coherent narrative and, even better in some circumstances, a cliff-hanger.

In your outline you should bear in mind the main elements of creative nonfiction and the fact that there are some universal literary techniques you can use:

Plot And Setting

There are many things from your past that may trigger your imagination. It could be writing about an area you grew up in, neighbours you had – anything which can be descriptive and used as a building block but will be the foundation upon which you set the tone or introduction to your piece.

Artefacts

Using what may seem like mundane artefacts can be used effectively. For instance, old photographs, school reports, records and letters etc. can evoke memories.

Descriptive Imagery

The most effective way to ensure your characters are relatable is to work on creating a plausible narrative. You must also have at the forefront of your mind “Facts. Facts. Facts.” I can’t stress enough how your work must be based on fact and not fiction.

Dialogue

Also referred to as figurative language, when using one of the most effective ways to set the tone of your work, the language used in dialogue must be plausible. You simply need to step back and ask yourself, “Does this sound like something my character would say?” There’s no greater turnoff for a reader than dialogue which is stilted.

Characters

If you want your readers to be engaged, they have to “buy what you’re selling” i.e. believe in your characters.

Top Creative Nonfiction Writing Tips

Stick to the facts .

Even a mere whiff of fiction in your writing will automatically disqualify it as creative nonfiction. To make sure you haven’t transgressed it’s easier to avoid doing so altogether. Although it’s fine to incorporate literary techniques which include extended metaphor, allegory, and imagery, among others.

You will also need to make note of the references you have relied upon. Not only is this good housekeeping it is also what’s expected of a professional writer. There are a multitude of places you can begin your research: family recollections/oral history; my local library serves aspiring writers well with both a respectable catalogue of physical books and online resources such as the British Newspaper Archives; Ancestry; and FindMyPast, among them. These are invaluable tools at your disposal and the list is by no means exhaustive.

Checklist

So, to conclude, what are the takeaways from this guide?

Firstly, methodically work your way through the checklist contained within the 5 R’s. Also, remember, whatever your interest, the extent of creative nonfiction dictates that there’s likely to be a market for your writing.

But, at all costs, avoid falling into the cardinal sin of making things up! It may be tempting to get carried away with being creative and miss that the finished product absolutely must be anchored in facts – from which, no deviation is acceptable.

Indeed, please ensure everything you’ve written is verifiable. You never know when someone is going to fact-check your thesis or challenge an assertion you’ve made.

Best Of Both Worlds

All in all, creative nonfiction is a wondrous way of telling an important and real story. Never forget that even though you are writing about factual stories and scenarios, you can still do so in an imaginative and creative way guaranteed to bring your readers on a journey of exploration with you.

About the author

Sonia Grant is a writer (primarily of nonfiction) and author; she is currently working on two historical creative nonfiction books. In addition to Jericho Writers, her other writing has been published by BBC History Revealed and Huffington Post. For more on Sonia, see her website or her Twitter .

Most popular posts in...

Advice on getting an agent.

- How to get a literary agent

- Literary Agent Fees

- How To Meet Literary Agents

- Tips To Find A Literary Agent

- Literary agent etiquette

- UK Literary Agents

- US Literary Agents

Help with getting published

- How to get a book published

- How long does it take to sell a book?

- Tips to meet publishers

- What authors really think of publishers

- Getting the book deal you really want

- 7 Years to Publication

Get to know us for free

- Join our bustling online writing community

- Make writing friends and find beta readers

- Take part in exclusive community events

- Get our super useful newsletters with the latest writing and publishing insights

Or select from our premium membership deals:

Premium annual – most popular.

per month, minimum 12-month term

Or pay up front, total cost £150

Premium Flex

Cancel anytime

Paid monthly

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cfduid | 1 month | The cookie is used by cdn services like CloudFare to identify individual clients behind a shared IP address and apply security settings on a per-client basis. It does not correspond to any user ID in the web application and does not store any personally identifiable information. |

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| JSESSIONID | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. | |

| PHPSESSID | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. | |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by CloudFare. The cookie is used to support Cloudfare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _gat | 1 minute | This cookies is installed by Google Universal Analytics to throttle the request rate to limit the colllection of data on high traffic sites. |

| GCLB | 12 hours | This cookie is known as Google Cloud Load Balancer set by the provider Google. This cookie is used for external HTTPS load balancing of the cloud infrastructure with Google. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assign a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gid | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the website is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages visted in an anonymous form. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | This cookie is used to a profile based on user's interest and display personalized ads to the users. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description |

| _hjid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Hotjar. This cookie is set when the customer first lands on a page with the Hotjar script. It is used to persist the random user ID, unique to that site on the browser. This ensures that behavior in subsequent visits to the same site will be attributed to the same user ID. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_cookie_expiry | 3 months | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_sess_landing | 3 months | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_sess_visit | 3 months | No description |

| CONSENT | 16 years 8 months 4 days 9 hours | No description |

| InfusionsoftTrackingCookie | 1 year | No description |

| m | 2 years | No description |

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Creative Nonfiction in Writing Courses

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Introduction

Creative nonfiction is a broad term and encompasses many different forms of writing. This resource focuses on the three basic forms of creative nonfiction: the personal essay, the memoir essay, and the literary journalism essay. A short section on the lyric essay is also discussed.

The Personal Essay

The personal essay is commonly taught in first-year composition courses because students find it relatively easy to pick a topic that interests them, and to follow their associative train of thoughts, with the freedom to digress and circle back.

The point to having students write personal essays is to help them become better writers, since part of becoming a better writer is the ability to express personal experiences, thoughts and opinions. Since academic writing may not allow for personal experiences and opinions, writing the personal essay is a good way to allow students further practice in writing.

The goal of the personal essay is to convey personal experiences in a convincing way to the reader, and in this way is related to rhetoric and composition, which is also persuasive. A good way to explain a personal essay assignment to a more goal-oriented student is simply to ask them to try to persuade the reader about the significance of a particular event.

Most high-school and first-year college students have plenty of experiences to draw from, and they are convinced about the importance of certain events over others in their lives. Often, students find their strongest conviction in the process of writing, and the personal essay is a good way to get students to start exploring these possibilities in writing.

A personal essay assignment can work well as a prelude to a research paper, because personal essays will help students understand their own convictions better, and will help prepare them to choose research topics that interest them.

An Example and Discussion of a Personal Essay

The following excerpt from Wole Soyinka's (Nigerian Nobel Laureate) Why Do I Fast? is an example of a personal essay. What follows is a short discussion of Soyinka's essay.

Soyinka begins with a question that fascinates him. He doesn’t feel required to immediately answer the question in the second paragraph. Rather, he takes time to consider his own inclination to believe that there is a connection between fasting and sensuality.

Soyinka follows the flowing associative arc of his thoughts, and he goes on to write about sunsets, and quotes from a poem that he wrote in his cell. The essay ends, not on a restatement of his thesis, but on yet another question that arises:

This question remains unanswered. Soyinka is not interested in even attempting to answer it. The personal essay doesn’t necessarily seek to make sense out of life experiences; rather, personal essays tend to let go of that sense-making impulse to do something else, like nose around a bit in the wondering, uncertain space that lies between experience and the need to organize it in a logical manner.

However informal the personal essay may seem, it’s important to keep in mind that, as Dinty W. Moore says in The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction , “the essay should always be motivated by the author’s genuine interest in wrestling with complex questions.”

Generating Ideas for Personal Essays

In The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction , Moore goes on to explain an effective way to help students generate ideas for personal essays:

“Think about ten things you care about deeply: the environment, children in poverty, Alzheimer’s research (because your grandfather is a victim), hip-hop music, Saturday afternoon football games. Make your own list of ten important subjects, and then narrow the larger subject down to specific subjects you might write about. The environment? How about that bird sanctuary out on Township Line Road that might be torn down to make room for a megastore?..."

"...What is it like to be the food service worker who puts mustard on two thousand hot dogs every Saturday afternoon? Don’t just wonder about it - talk to the mustard spreader, spend an afternoon hanging out behind the counter, spread some mustard yourself. Transform your list of ten things into a longer list of possible story ideas. Don’t worry for now about whether these ideas would take a great amount of research, or might require special permission or access. Just write down a master list of possible stories related to your ideas and passions. Keep the list. You may use it later.”

It is this flexibility of form in the personal essay that makes it easy for students who are majoring in engineering, nutrition, graphic design, finance, management, etc. to adapt, learn and practice. The essay can be a more worldly form of writing than poetry or fiction, so students from various backgrounds, majors, jobs and cultures can express interesting and powerful thoughts and feelings in them.

The essay is more worldly than poetry and fiction in another sense: it allows for more of the world and its languages, its arts and food, its sport and business, its travel and politics, its sciences and entertainment, to be present, valid and important.

6 Best Practices for Writing Creative Nonfiction

People browsing books usually scan the cover for the title, author, and whoever wrote the foreword. Then they glance at the back cover.

If intrigued, they’ll turn to the first chapter.

Your first paragraph—from the first sentence—must compel your reader to continue.

The power of creative nonfiction comes from using a technique common in fiction—rendering a visual to trigger the theater of the readers’ minds.

Certain stories should be told exactly as they happened. Take it from a novelist who also writes nonfiction: You don’t have to resort to fiction to captivate readers. Creative nonfiction is often the best way to go.

- What is Creative Nonfiction?

Also referred to as literary or narrative nonfiction (and sometimes literary journalism), the term can be confusing. “Creative” is usually associated with make-believe. So can nonfiction be creative?

It not only can, but should be to gain the attention of an agent or publisher—and ultimately your readership.

Unlike academic and technical writing (and even objective journalism), creative nonfiction uses many of the techniques and devices employed in fiction to tell a compelling true story. The goal is the same as in fiction: a story well told.

Some nonfiction narratives carry a literary flair every bit as beautiful as classic novels.

My very favorite book ever, Rick Bragg’s memoir All Over but the Shoutin’ , won rave reviews all over the country. Bragg’s haunting, poetic prose was a byproduct of the point of his book, not the reason for it.

The Best Creative Nonfiction Writers Are…

1. avid readers..

Writers are readers. Good writers are good readers . Great writers are great readers.

Read everything you can find in your genre before trying to write in it.

You’ll quickly learn the conventions and expectations, what works and what doesn’t.

2. Focused on the heart, but not preachy.

Creative nonfiction consists of an emotionally powerful message that moves readers, potentially changing their lives. But don’t preach. True art gives your reader credit for getting the point.

Readers love to be educated and entertained, but move them emotionally and they’ll never forget it.

3. Precise.

Employing fictional literary tools doesn’t mean being loose with the facts. Become an avid researcher.

Your story should be:

- Interesting

Are you being objective or spinning your own angle?

Your research should contribute to real stories well told.

Remember to use your research to season your main course—the point of your book. Resist the urge to show off all you learned with an information dump.

4. Rule followers.

Writing a story is like building a house—if the foundation’s not solid, even the most beautiful structure won’t stand.

Experts agree that these 7 elements must exist in a story (follow the links to study further).

- Point of View

5. Not afraid to get personal.

Include your unique voice and perspective, even if the book or story is not about you.

6. Creative (pun intended).

Readers bore quickly, so don’t just review a Chinese restaurant—explain how they get that fortune inside the cookie without getting it soggy.

Don’t just write a standard business piece on a store. Profile one of its most loyal customers.

Autobiography: First We Have Coffee by Margaret Jensen, Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain, The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank, The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Biography: A Passion for the Impossible by Miriam Huffman Rockness, Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, John Adams by David McCullough, Churchill: A Life by Martin Gilbert, Son of the Wilderness: The Life of John Muir by Linnie Marsh Wolfe

Memoir: All Over but the Shoutin’ by Rick Bragg, Cultivate by Lara Casey, A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway, Out of Africa by Karen Blixen, Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

How-to: Reconcilable Differences by Jim Talley, the … For Dummies guides, The Magical Power of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo, Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott, The 4-Hour Work Week by Tim Ferris

Motivational: The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey, The War of Art by Steven Pressfield, Think and Grow Rich by Napoleon Hill, The Seven Decisions by Andy Andrews, Intentional Living by John Maxwell

Christian Living: Chasing God by Angie Smith, The Search for Significance by Robert McGee, The 5 Love Languages: The Secret to Love That Lasts by Gary Chapman, Boundaries by John Townsend, Love Does by Bob Goff

Children’s Books: Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson, The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus by Jen Bryant, My Brother’s Book by Maurice Sendak

Inspirational: Joni by Joni Eareckson Tada with Joe Musser, Wild by Cheryl Strayed, The Hiding Place by Corrie ten Boom with John and Elizabeth Sherrill, Undone: A Story of Making Peace with an Unexpected Life by Michele Cushatt, You’ve Gotta Keep Dancin’ by Tim Hansel

Expository: Mere Christianity by C. S. Lewis, Desiring God by John Piper, Breaker Boys: How a Photograph Helped End Child Labor by Michael Burgan, Who Was First? Discovering the Americas by Russell Freedman, The Pursuit of God by A.W. Tozer

- Time to Get to Work

Few pleasures in life compare to getting lost in a great story . The stories we tell can live for years in the hearts of readers.

Do you have an idea, an insight, a challenge, or an experience you long to share?

Don’t let it rest just because of all the work it takes. If it was easy, anybody could do it.

Master the best practices I’ve shared above so you can do justice to the important stories you have to tell.

For additional help writing creative nonfiction:

- How to Write Your Memoir: A 5-Step Guide and How to Start Writing Your Memoir

- How to Write an Anecdote and Why Stories Bring Your Nonfiction to Life

- How to Write a Devotional: The Definitive Guide

- How to Edit a Book: 7 Steps for Becoming a Ferocious Self Editor

- The Best Creative Nonfiction Writers Are...

Are You Making This #1 Amateur Writing Mistake?

Faith-Based Words and Phrases

What You and I Can Learn From Patricia Raybon

Before you go, be sure to grab my FREE guide:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

Just tell me where to send it:

Literary Nonfiction | Definition, Examples & Essays

Bethany is a certified Special Education and Elementary teacher with 11 years experience teaching Special Education from grades PK through 5. She has a Bachelor's degree in Special Education, Elementary Education, and English from Gordon College and a Master's degree in Special Education from Salem State University.

Angela has taught middle and high school English, Business English and Speech for nine years. She has a bachelor's degree in psychology and has earned her teaching license.

What are some examples of literary nonfiction?

Examples of literary nonfiction include:

- Biographies such as Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

- Autobiographies such as Clapton The Autobiography by Eric Clapton

- Memoirs like I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Science writing like The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson

What does literary nonfiction mean?

Literary nonfiction is writing based on facts or realistic events and presented using writing styles and techniques most commonly associated with fiction (such as plot, characterization, setting, and figurative language).

What are the elements of literary nonfiction?

Literary nonfiction is fact-based writing characterized by fictional writing techniques such as:

- descriptive imagery

- figurative language

Table of Contents

What is literary nonfiction, types of literary nonfiction, lesson summary.

Written material can be divided into two basic categories: fiction, which is writing that reflects the author's inventions, and nonfiction, which is writing rooted in fact and real events. The field of nonfiction can be further broken down into two categories, informational and literary. Informational nonfiction is written to convey facts to readers, such as textbooks and instructional brochures. What is literary nonfiction? The literary nonfiction definition encompasses writing that is structured using literary styles and techniques while being rooted in reality, such as actual events, people, and facts. Creative nonfiction is another term that describes literary nonfiction.

Features of Literary Nonfiction

The literary nonfiction definition suggests that writing tactics more commonly associated with fictional storytelling are applied to true texts. The following table captures some features and story elements common to literary nonfiction.

| Feature | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Plot | The term plot refers to the shape of the story. A common plot structure is an introduction, conflict, rising action, climax, and falling action. Much literary nonfiction follows a classic plot structure. |

| Setting | The setting is where and when the story takes place. Literary nonfiction includes information and descriptions of the text's setting. |

| Characters | In literary nonfiction, characters play an important part in conveying the factual information and giving the text personality and relatability. |

| Descriptive Imagery | Descriptive imagery is used to paint a picture with words. Authors often rely on words that appeal to the five senses to create vivid word images. Descriptive imagery often adds depth and immediacy to literary nonfiction. |

| Figurative Language | Figurative language is any language that is not strictly literal, such as metaphor and symbolism. These techniques add flair and interest to literary nonfiction. |

| Tone | Rather than the factual, no-nonsense tone of informational nonfiction, literary nonfiction may employ a tone that is more creative or personal. |

The use of these writing features in literary nonfiction can make the text more appealing to a broader reader base.

Literary Nonfiction Examples

Literary nonfiction examples represent a wide variety of titles. Here are just a few texts that fit the literary nonfiction category.

- The Glorious American Essay: One Hundred Essays from Colonial Times to the Present by Phillip Lopate: This collection contains essays on a variety of topics from famous American figures. The essay format presents personal opinions and values.

- A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier by Ishmael Beah: In this memoir, the author recounts his personal experience as a child soldier. A memoir is a real event written in story format.

- The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson: This text takes a scientific topic, the human body, and explores factual information in a narrative format.

- Robin Williams: The Life of a Comedian, a Biography by Justin Kirby: In this biography, the author tells the life story of a well-known actor and comedian.

These examples represent the fields of memoir, biography, science writing, and essay, four branches of the literary nonfiction genre.

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member. Create your account

An error occurred trying to load this video.

Try refreshing the page, or contact customer support.

You must c C reate an account to continue watching

Register to view this lesson.

As a member, you'll also get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons in math, English, science, history, and more. Plus, get practice tests, quizzes, and personalized coaching to help you succeed.

Get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons.

Already registered? Log in here for access

Resources created by teachers for teachers.

I would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline.

You're on a roll. Keep up the good work!

Just checking in. are you still watching.

- 0:01 What Is Literary Nonfiction?

- 0:52 Autobiographical Nonfiction

- 4:15 The Essay

- 5:34 Lesson Summary

There are several general types of literary nonfiction: Nonfiction essays, personal narratives, science writing, narrative journalism, and narrative history. Examples of these types can be found in both adult and children's literature.

Nonfiction Essay

A nonfiction essay is a short text dealing with a single topic. A classic essay format includes:

- An introductory paragraph, ending in a statement of thesis (that is, the purpose of the essay).

- Body paragraphs that provide proof, details, and development for the thesis.

- A conclusion paragraph that wraps up the essay's information and restates the thesis.

Nonfiction essays serve three basic purposes:

- Expository essays provide an explanation, such as of an idea or process. Expository essays are generally formal in tone and structure.

- Personal essays are used to give the author's viewpoint and feelings, and may tell personal stories or experiences. Personal essays may be informal and have a flexible structure.

- Persuasive essays argue a point with the intent to persuade the audience to adopt a position or action.

Because these essays deal with factual content, they are considered nonfiction. The inclusion of elements such as plot, figurative language, and descriptive imagery puts these essays into the category of literary nonfiction.

Personal Narrative Nonfiction

A large sub-genre of literary nonfiction is that of personal narrative . Personal narratives relate true experiences and thoughts of the author or subject. Included in personal narrative nonfiction are:

- Autobiographies : In an autobiography, the author relates the story of their own life in narrative format. Autobiographies are generally meant to cover a large portion of a person's life. One example is Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela by Nelson Mandela.

- Memoirs : A memoir is the author's recount of an important event or segment of their life. Memoirs differ from autobiographies in that the focus is on a theme or message and the life story is not comprehensive. A memoir example is Riding the Bus With My Sister by Rachel Simon.

- Diaries : Diaries are daily personal records of thoughts and feelings. Often not meant to be shared with the public, diaries represent snapshots of the author's personal impressions rather than a focused attempt to convey a message to an audience. The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank is an example of a diary that was found and published.

- Journals : Personal journals are daily accounts of a person's activities, experiences, and observations. Personal journals may be published to inform readers about an event, mission, experiment, or journey. Journals may also be kept for only an individual or a few friends or colleagues. A published journal example is My Arctic Journal: A Year among Ice-Fields and Eskimos by Josephine Peary.

- Letters : Letters are a personal narrative written by one person to another. Letters reflect the thoughts, opinions, or needs of the author, but are usually not intended to be shared broadly. Sometimes letters are recovered and used in historical research, and a few may be published for a wider audience. An example of published letters is Posterity: Letters of Great Americans to Their Children collected by Dorie McCullough Lawson.

Each of these personal narrative examples are autobiographical in style; that is, the author is telling their own story, opinions, or experiences. Biography , the story of someone's life told by another author, is also included under the general umbrella of personal narrative nonfiction. For example, George Washington: A Biography written by Washington Irving.

Science Writing

Imaginative science writing is crafted to convey scientific principles and knowledge through creative, relatable writing with an emphasis on non-technical language. The target audience for science writing is not trained scientists, but people with an average education who may or may not have a prior interest in the topic of the text. For example, in The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer , author Siddhartha Mukherjee relays the history of cancer using both scientific fact and detail and storytelling tactics, such as compelling characters.

Children's literature produces a variety of science writing in a creative style. In The Magic Schoolbus series, a teacher and her class take their school bus on unlikely field trips to learn factual science in a child-friendly fashion. Judy Allen's series of bug books, such as Are You a Spider? , contain true facts about insects presented in a conversational narrative format with bright illustrations on every page. These are just two of many examples available.

Narrative Journalism

Narrative journalism is the reporting of news and other current events using well-researched data and narrative techniques (such as plot, characterization, setting, etc.). Narrative journalism generally requires the reporter to use a less formal or less omniscient tone. Popular topics for narrative journalism include travel, food, and sports; however, narrative journalism can be used for other events as well.

Narrative History

In narrative history the author relates historical facts without invention, but in a story-telling style. Narrative history differs in style from analytical history writing, which seeks to determine the causes of and relationships between events. Narrative history also differs from expositional history writing, which adopts a more formal and factual tone.

Literary nonfiction , also called creative nonfiction , is writing rooted in fact but adopting writing tactics commonly associated with fiction such as plot, setting, characters, descriptive imagery, figurative language, and tone. Types of literary nonfiction include:

- Nonfiction essays : includes expository (explaining a topic), personal (sharing experiences or feelings), and persuasive (convincing the reader of a point); usually a brief text addressing a single topic

- Personal narrative nonfiction : written about an author's experiences; includes autobiographies (the author's life story), memoirs (highlights one theme/era/experience), diaries (daily record of personal thoughts/feelings not intended for publication), journals (daily record of experiences), letters (messages to a specific person), biographies (the only personal narrative written by a third party)

- Science writing : conveying scientific facts and principles through creative narrative writing

- Narrative journalism : factual data on current events, travel, sports, or food written using informal tone and narrative techniques

- Narrative history : factual historical events presented in story-telling style.

Literary nonfiction examples are found in both adult's and children's literature.

Video Transcript

What is literary nonfiction.

Nonfiction , which includes any writing based on real life events, encompasses a vast variety of writing. Two subcategories for nonfiction are informational and literary. Informational nonfiction includes writing with the purpose to describe or express facts. Literary nonfiction also contains facts, but is meant to entertain the reader. In this way, literary nonfiction reads like fiction and has story elements, like character, setting and plot.

Some examples of literary nonfiction include personal journals, diaries, memoirs, letters, and essays. Let's look at the characteristics of each of these.

Autobiographical Nonfiction

Much of literary nonfiction can be described as autobiographical , which is writing from the author's perspective. This type of writing is usually in first person point of view , which means the narrator is a character in the story. Since the author is the narrator, this means the author is the main character in the story. Most autobiographies are novel-length since they cover the subject's entire life. However, there are many shorter works that are still considered autobiographical.

The first such work is a personal journal , which is a daily written record of personal experiences and observations. This usually consists of short pieces of writing each day. For example, if you were assigned to design an experiment for a science project, you might keep a journal to describe what you did for that experiment every day until the project was due. A journal could be kept for a few weeks or even several years but always has a factual account of experiences of the author.

Another related autobiographical work is the diary . Similar to journals, diaries contain a daily account of experiences. The difference is diaries include personal thoughts and feelings. While a journal is more based on facts, a diary can have a person's deepest secrets and desires; as such, it is usually not meant to be shared with anyone. A great example is the book The Diary of Anne Frank . Anne Frank was a real Jewish girl who kept a diary while hiding from the Germans during World War II. She wrote about her personal thoughts and feelings about what was happening to her family. Years later, her diary was found and published by Anne's descendants to showcase the terrors of Nazi Germany.

A third type of autobiographical work is the memoir . Memoirs are extremely similar to journals and diaries in that memoirs relate the author's personal experiences. Like diaries, memoirs can also reveal the narrator's personal feelings. Memoirs are different because they are not written daily, are meant to be published and shared, and usually focus on one specific event or theme. A well-known memoir is Tuesdays with Morrie . In this book, the author, Mitch Albom, recounts his time spent with his aging sociology professor who is dying from ALS. This memoir is limited to that period of Albom's life. Other events of his life are not shown.

A final example of an autobiographical work of literary nonfiction is a letter . A letter is a written message addressed to a person or organization. Letters often contain personal thoughts and opinions, but they are directed at just one person. Letters are never really meant to be published and are usually discarded once the message is received. Emails can be considered a more advanced type of letter.

Journals, diaries, memoirs and letters are all examples of autobiographical nonfiction. One type of literary nonfiction that is not autobiographical is the essay . An essay is a short work of nonfiction that deals with a single subject. Essays can describe, inform, persuade, express or accomplish a number of other purposes. The key idea is to keep to one area of focus.

There are three types of essays. The first is an expository essay , which includes formal writing with a strict structure. Expository essays usually aim to explain information or an idea. The topics are serious subjects with an impersonal tone. An essay explaining the definition of global warming is an example of an expository essay.

The second type is the personal essay. These essays are informal and have a looser structure. The purpose is to express the thoughts, feelings and observations of the writer. You would be writing a personal essay if your essay expressed your thoughts on the existence of global warming.

The last type of essay is persuasive . These essays develop arguments and try to convince the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. If your essay urges others to recycle in order to cut down on global warming, then you are trying to persuade.

Overall, nonfiction includes a wide variety of writing. Two subcategories are informational and literary nonfiction. Literary nonfiction is related to fiction in that it includes story elements.

Personal journals, diaries, memoirs and letters are all examples of autobiographical literary nonfiction. These are told in first person point of view, which means the author is the main character. Journals and diaries are both daily written accounts of personal experiences. Diaries, however, are not meant to be shared, since they contain very personal thoughts. On the other hand, memoirs are intended to be published and have one specific theme. Finally, letters are written messages meant to convey information. These may contain personal thoughts and opinions, but are discarded once the message is received.

A final example of literary nonfiction is the essay. An essay is a short written work on a single subject. There are three types of essays. Expository essays are formal and focus on providing information. Personal essays are informal and express thoughts, feelings or observations. Persuasive essays develop an argument and try to convince the reader to believe a certain idea. All of these types of literary nonfiction can help you to accomplish a variety of goals in your writing.

Learning Outcomes

After you have reviewed this lesson you should be able to:

- Name two subcategories of nonfiction

- Compare the different types of autobiographical nonfiction

- Discuss the three types of essays

Unlock Your Education

See for yourself why 30 million people use study.com, become a study.com member and start learning now..

Already a member? Log In

Recommended Lessons and Courses for You

Related lessons, related courses, recommended lessons for you.

Literary Nonfiction | Definition, Examples & Essays Related Study Materials

- Related Topics

Browse by Courses

- LSAT Test: Online Prep & Review

- CSET English Subtests I & III (105 & 107): Practice & Study Guide

- NYSTCE English Language Arts (003): Practice and Study Guide

- CSET English Subtest IV (108) Prep

- 11th Grade English: Help and Review

- 11th Grade English: Tutoring Solution

- 9th Grade English: Homework Help Resource

- 9th Grade English: Tutoring Solution

- Comprehensive English: Overview & Practice

- Common Core ELA Grade 8 - Writing: Standards

- Common Core ELA Grade 8 - Literature: Standards

- SAT Subject Test Literature: Practice and Study Guide

- CAHSEE English Exam: Test Prep & Study Guide

- Common Core ELA Grade 8 - Language: Standards

- 11th Grade English: High School

Browse by Lessons

- Nonfiction Biography & Autobiography | Types & Differences

- Non-Fiction as Literary Form: Definition and Examples

- Narrative Nonfiction | Definition & Examples

- Literary Device Types, Use & Examples

- Nonfiction Short Stories | Overview, Format & Examples

- Communicating Ideas in Nonfiction

- The Iliad by Homer: Book 3 | Summary, Analysis & Themes

- The Iliad Book 4 Summary

- The Iliad by Homer: Book 6 | Summary, Characters & Analysis

- The Iliad Book 8 Summary

- The Iliad Book 10 Summary

- The Iliad Book 11 Summary

- The Iliad by Homer: Book 13 | Summary, Characters & Quotes

- The Iliad Book 15 Summary

- The Iliad Book 17 Summary

Create an account to start this course today Used by over 30 million students worldwide Create an account

Explore our library of over 88,000 lessons

- Foreign Language

- Social Science

- See All College Courses

- Common Core

- High School

- See All High School Courses

- College & Career Guidance Courses

- College Placement Exams

- Entrance Exams

- General Test Prep

- K-8 Courses

- Skills Courses

- Teacher Certification Exams

- See All Other Courses

- Create a Goal

- Create custom courses

- Get your questions answered

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Writing Tips Oasis - A website dedicated to helping writers to write and publish books.

How to Write Literary Nonfiction

By CS Rajan

Literary nonfiction is a little difficult to define. Also called creative nonfiction, narrative nonfiction and literary journalism, this genre is essentially about describing the real world in a compelling and interesting manner.

It is a broad and expansive genre that encompasses different types of writing such as memoirs, personal essays, lyric essays, literary journalism, articles, and even research papers. The purpose of literary nonfiction is to make true stories and nonfiction content as interesting and engaging as possible by using literary devices. Settings, character development, tone and voice are all essential tools that are common in both literary nonfiction and fiction. However, in literary nonfiction, these tools are used to enhance the real world instead of a fantasy world.

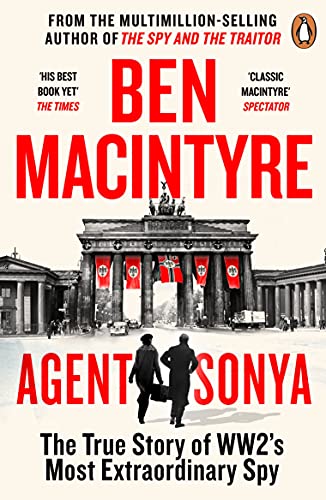

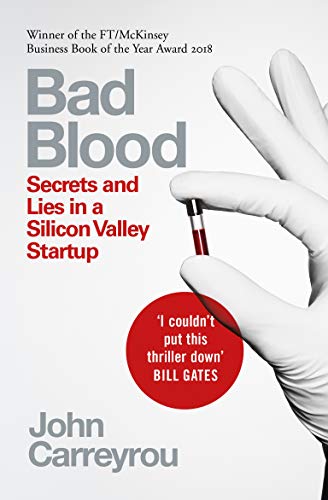

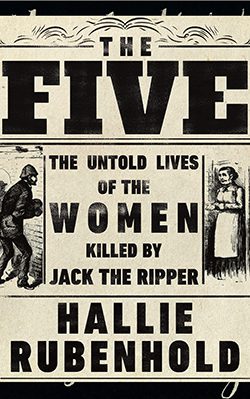

Literary or creative nonfiction has recently gained in popularity among magazine and book publishers due several highly popular literary nonfictions books released

Some of the ways you can begin your literary nonfiction adventure are:

1. Read literary nonfiction

The best way to understand the unique world of literary nonfiction books is to read as many of them as possible. Blending creative writing with real facts is an art which needs some perfecting. Reading some of the greats in this area can help you to achieve this fine balance. There are many wonderful nonfiction books which are a far cry from the typical dull, dry, and fact-based nonfiction books. Some examples of popular literary nonfiction books are: The Glass Castle, Unbroken, The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, The Botany of Desire, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, and Eat, Pray, Love.

2. Writing memoirs

Memoir writing is a great way to learn to use the creative tools to enhance a real story. Not to be confused with autobiographies , memoirs are lively and interesting stories of certain personal experiences, events, phases or stages in your life. A memoir can even be about people or pets who have made a difference in your life. For example, the wildly popular Marley and Me: Life with the world’s craziest dog is a moving true story of a journalist and his crazy but adorable Labrador. The story revolves around the author’s personal life, but the theme of the book is the pet and his influence on the author’s household.

3. Personal essays

A personal essay is similar to a memoir in some ways; however it focuses more on you, your experiences and thoughts, and your opinions. A single topic in your life (an event, an opinion, a viewpoint) is usually the theme of the personal essay. Also, while the memoir style is often narrative, the personal essay is usually non-narrative and takes on a more flowing and descriptive style.

4. Literary journalism

If looking within and writing about yourself makes you uncomfortable, there is a wealth of other topics to write about. Literary journalism involves writing about any actual public event, a person, or even an interview in a creative and narrative or descriptive manner. It essentially means that this is a form of journalism where you are not required to be objective or restrain yourself to reporting the facts. You can include your opinions, use personal examples to illustrate a point and employ any other tools you can think of to make the article engaging and interesting.

Image credit: Ken Hawkins on flickr and reproduced under Creative Commons 2.0

CS Rajan is a freelance writer who loves to write on various topics, and is currently working on her first novel.

Novlr is now writer-owned! Join us and shape the future of creative writing.

8 January 2024

How to Write Amazing Narrative Non-Fiction

Narrative non-fiction brings to life true stories like historic events and personal experiences. It uses the techniques usually associated with fiction writing, such as plot , character , and detailed scene-setting .

This very popular genre informs the reader with facts and detailed accounts of real-life events, but is written in an engaging and dramatic way designed to grip the reader’s attention and make the reading experience enjoyable. Narrative non-fiction is sometimes referred to as literary non-fiction or creative non-fiction.

Why should you write narrative non-fiction?

What is interesting and exciting about narrative non-fiction is that it can cover just about any topic. You might see it shelved in almost any section of physical and online bookstores. For example, narrative non-fiction can explore an unknown perspective on a historical event based on research that’s only just been discovered. It can tell the story of an individual or a company’s dramatic demise or it can paint an eye-opening picture of a particular political or social current affair.

What makes good narrative non-fiction?

Often written by investigative journalists, historians, and sometimes biographers, works of narrative non-fiction are informative but they are also entertaining to read because the storytelling element is so important.

Conducting original and thorough research is a cornerstone of good narrative non-fiction writing. When researching their subjects, writers will often conduct interviews with key people, obtain access to private diaries, read old newspaper articles, and search historical records in order to get the most accurate information about a series of events.

High-quality narrative

Another cornerstone of great narrative non-fiction is the quality of the writing. Just like in fiction books, writers use dialogue and characterization to reveal character relationships and story development. Choosing to tell the story through specific scenes instead of simply summarizing the events that took place is what separates this form of writing from other types of non-fiction like history, reports, news stories, and biographies.

The structure a writer chooses to tell the story in goes a long way to creating drama and suspense for readers. While straight histories or news reporting tend to tell events in chronological order, with narrative non-fiction you can be more playful. You can switch perspectives and timelines meaning that the story can be told in a more exciting and intriguing way.

For example, a lot of books open with a scene set in the present day to show the reader where the story is now, and then they will go back in time to show where the story began. Other books may start with a scene in the middle of all the action and then go back in time to tell the story from the beginning, catching up with the events the opening started with before going beyond them to finish the story.

The right balance between fact and fiction