- Contact sales (+234) 08132546417

- Have a questions? [email protected]

- Latest Projects

Project Materials

How to write a good chapter two: literature review.

Click Here to Download Now.

Do You Have New or Fresh Topic? Send Us Your Topic

How to write chapter two of a research pape r.

As is known, within a research paper, there are several types of research and methodologies. One of the most common types used by students is the literature review. In this article, we will be dealing how to write the literature review (Chapter Two) of your research paper.

Although when writing a project, literature review (Chapter Two) seems more straightforward than carrying out experiments or field research, the literature review involves a lot of research and a lot of reading. Also, utmost attention is essential when it comes to developing and referencing the content so that nothing is pointed out as plagiarism.

However, unlike other steps in project writing, it is not necessary to perform the separate theoretical reference part in the review. After all, the work itself will be a theoretical reference, filled with relevant information and views of several authors on the same subject over time.

As it technically has fewer steps and does not need to go to the field or build appraisal projects, the research paper literature review is a great choice for those who have the tightest deadline for delivering the work. But make no mistake, the level of seriousness in research and development itself is as difficult as any other step.

To further facilitate your understanding, we have divided this research methodology into some essential steps and will explain how to do each of them clearly and objectively. Want to know more about it? Read on and check it out!

What is the literature review in a research paper?

To develop a project in any discipline, it is necessary, first, to study everything that other authors have already explored on that subject. This step aims to update the subject for the academic community and to have a basis to support new research. Therefore, it must be done before any other process within the research paper. However, in the literature review (Chapter Two), this step of searching for data and previous work is all the work. That is, you will only develop the theoretical framework.

In general, you will need to choose the topic in question and search for more relevant works and authors that worked around that research idea you want to discuss. As the intention is to make history and update the subject, you will be able to use works from different dates, showing how opinions and views have evolved over time.

Suppose the subject of your research paper is the role of monarchies in 21st-century societies, for example. In that case, you must present a history of how this institution came about, its impact on society, and what roles the institution is currently playing in modern societies. In the end, you can make a more personal conclusion about your vision.

If your topic covered contains a lot of content, you will need to select the most important and relevant and highlight them throughout the work. This is because you will need to reference the entire work. This means that the research paper literature review needs to be filled with citations from other authors. Therefore, it will present references in practically every paragraph.

In order not to make your work uninteresting and repetitive, you should quote differently throughout development. Switching between direct and indirect citations and trying to fit as much content and work as possible will enrich your project and demonstrate to the evaluators how deep you have been in the search.

Within the review, the only part that does not need to be referenced is the conclusion. After all, it will be written as your final and personal view of everything you have read and analyzed.

How to write a literature review?

Here are some practical and easy tips for structuring a quality and compliant research paper literature review!

Introduction

As with any work, the introduction should attract your project readers’ attention and help them understand the basis of the subject that will be worked on. When reading the introduction, you need to be clear to whoever is reading about your research and what it wants to show.

Following the example cited on the theme of monarchies’ roles in the 21st-century societies, the introduction needs to clarify what this type of institution is and why research on it is vital for this area. Also, it would help if you also quoted how the work was developed and the purpose of your literary study.

Basically, you will introduce the subject in such a way that the reader – even without knowing anything about the topic – can read the complete work and grasp the approach, understanding what was done and the meaning of it.

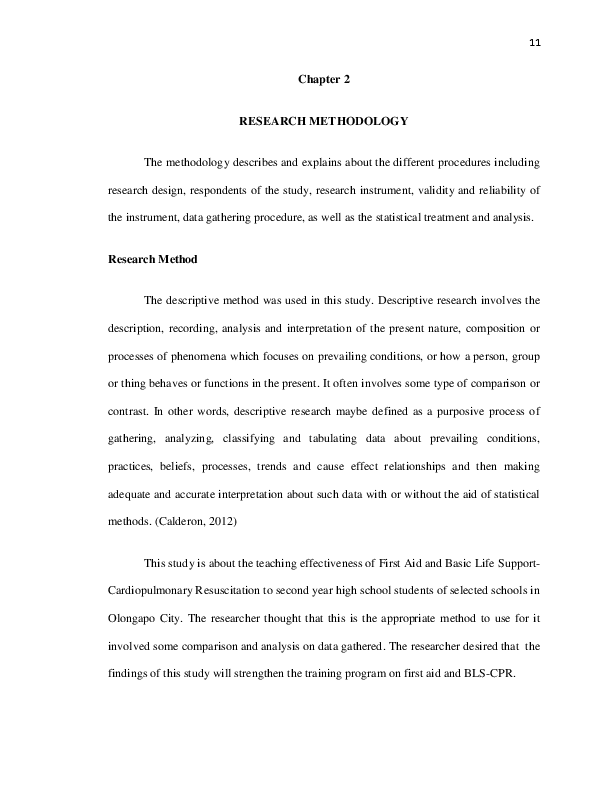

Methodology

Describing the methodology of a literature review is simpler than describing the steps of field research or experiment. In this step, you will need to describe how your research was carried out, where the information was searched, and retrieved.

As you will need to gather a lot of content, searches can be done in books, academic articles, academic publications, old monographs, internet articles, among other reliable sources. The important thing is always to be sure with your supervisor or other teachers about the reliability of each content used. After all, as the entire work is a theoretical reference, choosing unreliable base papers can greatly damage your grade and hinder your approval, putting at risk the quality and integrity of your entire research paper.

Results and conclusion

The results must present clearly and objectively everything that has been observed and collected from studies throughout history on the research’s theme. In this step, you should show the comparisons between authors, like what was the view of the subject before and how it is currently, in an updated way.

You will also be able to show the developments within the theme and the progress of research and discoveries, as well as the conclusions on the issue so far. In the end, you will summarize everything you have read and discovered, and present your final view on the topic.

Also, it is important to demonstrate whether your project objectives have been met and how. The conclusion is the crucial point to convince your reader and examiner of the relevance and importance of all the work you have done for your area or branch, society, or the environment. Therefore, you must present everything clearly and concisely, closing your research paper with a flourish.

In all academic work, bibliographic references are essential. In the academic paper literature review, however, these references will be gathered at the end of the work and throughout the texts.

Citations during the development of the subject must be referenced in accordance with the guideline of your institutions and departments. For each type of reference, there is a rule that depends on the number of words or how you will make it.

Also, in the list of bibliographic references, where you will need to put all the content used, the rules change according to your search source. For internet sources, for example, the way of referencing is different than book sources.

A wrong quote throughout the text or a used work that you forget to put in the references can lead to your project being labeled a plagiarism work, which is a crime and can lead to several consequences. Therefore, studying these standards is essential and determinant for the success of your work’s literature review (Chapter Two).

By adequately studying the rules, dedicating yourself, and putting them into practice, not only will it be easy to develop a successful project, but achieving your dream grade will be closer than you think.

Not What You Were Looking For? Send Us Your Topic

INSTRUCTIONS AFTER PAYMENT

- 1.Your Full name

- 2. Your Active Email Address

- 3. Your Phone Number

- 4. Amount Paid

- 5. Project Topic

- 6. Location you made payment from

» Send the above details to our email; [email protected] or to our support phone number; (+234) 0813 2546 417 . As soon as details are sent and payment is confirmed, your project will be delivered to you within minutes.

Latest Updates

Role of cooperative society in the provision of agro processing equipment, role of federal government in cooperative financing, factors that can influence the establishment of cooperative., leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Advertisements

- Hire A Writer

- Plagiarism Research Clinic

- International Students

- Project Categories

- WHY HIRE A PREMIUM RESEARCHER?

- UPGRADE PLAN

- PROFESSIONAL PLAN

- STANDARD PLAN

- MBA MSC STANDARD PLAN

- MBA MSC PROFESSIONAL PLAN

Research Methods

Chapter 2 introduction.

Maybe you have already gained some experience in doing research, for example in your bachelor studies, or as part of your work.

The challenge in conducting academic research at masters level, is that it is multi-faceted.

The types of activities are:

- Finding and reviewing literature on your research topic;

- Designing a research project that will answer your research questions;

- Collecting relevant data from one or more sources;

- Analyzing the data, statistically or otherwise, and

- Writing up and presenting your findings.

Some researchers are strong on some parts but weak on others.

We do not require perfection. But we do require high quality.

Going through all stages of the research project, with the guidance of your supervisor, is a learning process.

The journey is hard at times, but in the end your thesis is considered an academic publication, and we want you to be proud of what you have achieved!

Probably the biggest challenge is, where to begin?

- What will be your topic?

- And once you have selected a topic, what are the questions that you want to answer, and how?

In the first chapter of the book, you will find several views on the nature and scope of business research.

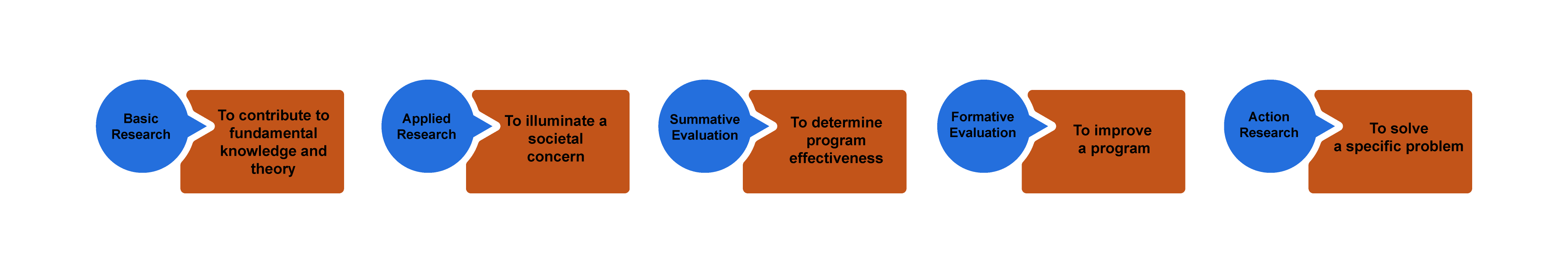

Since a study in business administration derives its relevance from its application to real-life situations, an MBA typically falls in the grey area between applied research and basic research.

The focus of applied research is on finding solutions to problems, and on improving (y)our understanding of existing theories of management.

Applied research that makes use of existing theories, often leads to amendments or refinements of these theories. That is, the applied research feeds back to basic research.

In the early stages of your research, you will feel like you are running around in circles.

You start with an idea for a research topic. Then, after reading literature on the topic, you will revise or refine your idea. And start reading again with a clearer focus ...

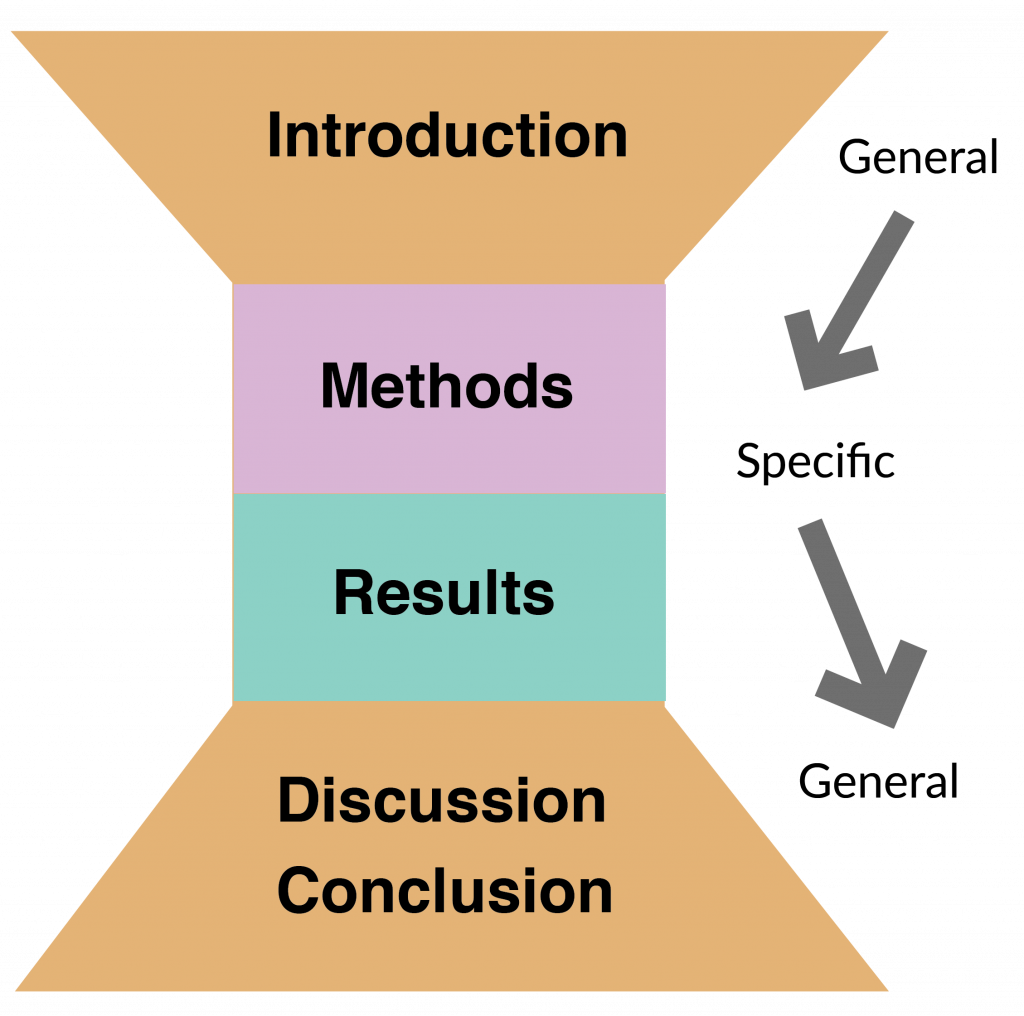

A thesis research/project typically consists of two main stages.

The first stage is the research proposal .

Once the research proposal has been approved, you can start with the data collection, analysis and write-up (including conclusions and recommendations).

Stage 1, the research proposal consists of he first three chapters of the commonly used five-chapter structure :

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- An introduction to the topic.

- The research questions that you want to answer (and/or hypotheses that you want to test).

- A note on why the research is of academic and/or professional relevance.

- Chapter 2: Literature

- A review of relevant literature on the topic.

- Chapter 3: Methodology

The methodology is at the core of your research. Here, you define how you are going to do the research. What data will be collected, and how?

Your data should allow you to answer your research questions. In the research proposal, you will also provide answers to the questions when and how much . Is it feasible to conduct the research within the given time-frame (say, 3-6 months for a typical master thesis)? And do you have the resources to collect and analyze the data?

In stage 2 you collect and analyze the data, and write the conclusions.

- Chapter 4: Data Analysis and Findings

- Chapter 5: Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

This video gives a nice overview of the elements of writing a thesis.

Chapter 2. Research Design

Getting started.

When I teach undergraduates qualitative research methods, the final product of the course is a “research proposal” that incorporates all they have learned and enlists the knowledge they have learned about qualitative research methods in an original design that addresses a particular research question. I highly recommend you think about designing your own research study as you progress through this textbook. Even if you don’t have a study in mind yet, it can be a helpful exercise as you progress through the course. But how to start? How can one design a research study before they even know what research looks like? This chapter will serve as a brief overview of the research design process to orient you to what will be coming in later chapters. Think of it as a “skeleton” of what you will read in more detail in later chapters. Ideally, you will read this chapter both now (in sequence) and later during your reading of the remainder of the text. Do not worry if you have questions the first time you read this chapter. Many things will become clearer as the text advances and as you gain a deeper understanding of all the components of good qualitative research. This is just a preliminary map to get you on the right road.

Research Design Steps

Before you even get started, you will need to have a broad topic of interest in mind. [1] . In my experience, students can confuse this broad topic with the actual research question, so it is important to clearly distinguish the two. And the place to start is the broad topic. It might be, as was the case with me, working-class college students. But what about working-class college students? What’s it like to be one? Why are there so few compared to others? How do colleges assist (or fail to assist) them? What interested me was something I could barely articulate at first and went something like this: “Why was it so difficult and lonely to be me?” And by extension, “Did others share this experience?”

Once you have a general topic, reflect on why this is important to you. Sometimes we connect with a topic and we don’t really know why. Even if you are not willing to share the real underlying reason you are interested in a topic, it is important that you know the deeper reasons that motivate you. Otherwise, it is quite possible that at some point during the research, you will find yourself turned around facing the wrong direction. I have seen it happen many times. The reason is that the research question is not the same thing as the general topic of interest, and if you don’t know the reasons for your interest, you are likely to design a study answering a research question that is beside the point—to you, at least. And this means you will be much less motivated to carry your research to completion.

Researcher Note

Why do you employ qualitative research methods in your area of study? What are the advantages of qualitative research methods for studying mentorship?

Qualitative research methods are a huge opportunity to increase access, equity, inclusion, and social justice. Qualitative research allows us to engage and examine the uniquenesses/nuances within minoritized and dominant identities and our experiences with these identities. Qualitative research allows us to explore a specific topic, and through that exploration, we can link history to experiences and look for patterns or offer up a unique phenomenon. There’s such beauty in being able to tell a particular story, and qualitative research is a great mode for that! For our work, we examined the relationships we typically use the term mentorship for but didn’t feel that was quite the right word. Qualitative research allowed us to pick apart what we did and how we engaged in our relationships, which then allowed us to more accurately describe what was unique about our mentorship relationships, which we ultimately named liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021) . Qualitative research gave us the means to explore, process, and name our experiences; what a powerful tool!

How do you come up with ideas for what to study (and how to study it)? Where did you get the idea for studying mentorship?

Coming up with ideas for research, for me, is kind of like Googling a question I have, not finding enough information, and then deciding to dig a little deeper to get the answer. The idea to study mentorship actually came up in conversation with my mentorship triad. We were talking in one of our meetings about our relationship—kind of meta, huh? We discussed how we felt that mentorship was not quite the right term for the relationships we had built. One of us asked what was different about our relationships and mentorship. This all happened when I was taking an ethnography course. During the next session of class, we were discussing auto- and duoethnography, and it hit me—let’s explore our version of mentorship, which we later went on to name liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021 ). The idea and questions came out of being curious and wanting to find an answer. As I continue to research, I see opportunities in questions I have about my work or during conversations that, in our search for answers, end up exposing gaps in the literature. If I can’t find the answer already out there, I can study it.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

When you have a better idea of why you are interested in what it is that interests you, you may be surprised to learn that the obvious approaches to the topic are not the only ones. For example, let’s say you think you are interested in preserving coastal wildlife. And as a social scientist, you are interested in policies and practices that affect the long-term viability of coastal wildlife, especially around fishing communities. It would be natural then to consider designing a research study around fishing communities and how they manage their ecosystems. But when you really think about it, you realize that what interests you the most is how people whose livelihoods depend on a particular resource act in ways that deplete that resource. Or, even deeper, you contemplate the puzzle, “How do people justify actions that damage their surroundings?” Now, there are many ways to design a study that gets at that broader question, and not all of them are about fishing communities, although that is certainly one way to go. Maybe you could design an interview-based study that includes and compares loggers, fishers, and desert golfers (those who golf in arid lands that require a great deal of wasteful irrigation). Or design a case study around one particular example where resources were completely used up by a community. Without knowing what it is you are really interested in, what motivates your interest in a surface phenomenon, you are unlikely to come up with the appropriate research design.

These first stages of research design are often the most difficult, but have patience . Taking the time to consider why you are going to go through a lot of trouble to get answers will prevent a lot of wasted energy in the future.

There are distinct reasons for pursuing particular research questions, and it is helpful to distinguish between them. First, you may be personally motivated. This is probably the most important and the most often overlooked. What is it about the social world that sparks your curiosity? What bothers you? What answers do you need in order to keep living? For me, I knew I needed to get a handle on what higher education was for before I kept going at it. I needed to understand why I felt so different from my peers and whether this whole “higher education” thing was “for the likes of me” before I could complete my degree. That is the personal motivation question. Your personal motivation might also be political in nature, in that you want to change the world in a particular way. It’s all right to acknowledge this. In fact, it is better to acknowledge it than to hide it.

There are also academic and professional motivations for a particular study. If you are an absolute beginner, these may be difficult to find. We’ll talk more about this when we discuss reviewing the literature. Simply put, you are probably not the only person in the world to have thought about this question or issue and those related to it. So how does your interest area fit into what others have studied? Perhaps there is a good study out there of fishing communities, but no one has quite asked the “justification” question. You are motivated to address this to “fill the gap” in our collective knowledge. And maybe you are really not at all sure of what interests you, but you do know that [insert your topic] interests a lot of people, so you would like to work in this area too. You want to be involved in the academic conversation. That is a professional motivation and a very important one to articulate.

Practical and strategic motivations are a third kind. Perhaps you want to encourage people to take better care of the natural resources around them. If this is also part of your motivation, you will want to design your research project in a way that might have an impact on how people behave in the future. There are many ways to do this, one of which is using qualitative research methods rather than quantitative research methods, as the findings of qualitative research are often easier to communicate to a broader audience than the results of quantitative research. You might even be able to engage the community you are studying in the collecting and analyzing of data, something taboo in quantitative research but actively embraced and encouraged by qualitative researchers. But there are other practical reasons, such as getting “done” with your research in a certain amount of time or having access (or no access) to certain information. There is nothing wrong with considering constraints and opportunities when designing your study. Or maybe one of the practical or strategic goals is about learning competence in this area so that you can demonstrate the ability to conduct interviews and focus groups with future employers. Keeping that in mind will help shape your study and prevent you from getting sidetracked using a technique that you are less invested in learning about.

STOP HERE for a moment

I recommend you write a paragraph (at least) explaining your aims and goals. Include a sentence about each of the following: personal/political goals, practical or professional/academic goals, and practical/strategic goals. Think through how all of the goals are related and can be achieved by this particular research study . If they can’t, have a rethink. Perhaps this is not the best way to go about it.

You will also want to be clear about the purpose of your study. “Wait, didn’t we just do this?” you might ask. No! Your goals are not the same as the purpose of the study, although they are related. You can think about purpose lying on a continuum from “ theory ” to “action” (figure 2.1). Sometimes you are doing research to discover new knowledge about the world, while other times you are doing a study because you want to measure an impact or make a difference in the world.

Basic research involves research that is done for the sake of “pure” knowledge—that is, knowledge that, at least at this moment in time, may not have any apparent use or application. Often, and this is very important, knowledge of this kind is later found to be extremely helpful in solving problems. So one way of thinking about basic research is that it is knowledge for which no use is yet known but will probably one day prove to be extremely useful. If you are doing basic research, you do not need to argue its usefulness, as the whole point is that we just don’t know yet what this might be.

Researchers engaged in basic research want to understand how the world operates. They are interested in investigating a phenomenon to get at the nature of reality with regard to that phenomenon. The basic researcher’s purpose is to understand and explain ( Patton 2002:215 ).

Basic research is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works. Grounded Theory is one approach to qualitative research methods that exemplifies basic research (see chapter 4). Most academic journal articles publish basic research findings. If you are working in academia (e.g., writing your dissertation), the default expectation is that you are conducting basic research.

Applied research in the social sciences is research that addresses human and social problems. Unlike basic research, the researcher has expectations that the research will help contribute to resolving a problem, if only by identifying its contours, history, or context. From my experience, most students have this as their baseline assumption about research. Why do a study if not to make things better? But this is a common mistake. Students and their committee members are often working with default assumptions here—the former thinking about applied research as their purpose, the latter thinking about basic research: “The purpose of applied research is to contribute knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment. While in basic research the source of questions is the tradition within a scholarly discipline, in applied research the source of questions is in the problems and concerns experienced by people and by policymakers” ( Patton 2002:217 ).

Applied research is less geared toward theory in two ways. First, its questions do not derive from previous literature. For this reason, applied research studies have much more limited literature reviews than those found in basic research (although they make up for this by having much more “background” about the problem). Second, it does not generate theory in the same way as basic research does. The findings of an applied research project may not be generalizable beyond the boundaries of this particular problem or context. The findings are more limited. They are useful now but may be less useful later. This is why basic research remains the default “gold standard” of academic research.

Evaluation research is research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. We already know the problems, and someone has already come up with solutions. There might be a program, say, for first-generation college students on your campus. Does this program work? Are first-generation students who participate in the program more likely to graduate than those who do not? These are the types of questions addressed by evaluation research. There are two types of research within this broader frame; however, one more action-oriented than the next. In summative evaluation , an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made. Should we continue our first-gen program? Is it a good model for other campuses? Because the purpose of such summative evaluation is to measure success and to determine whether this success is scalable (capable of being generalized beyond the specific case), quantitative data is more often used than qualitative data. In our example, we might have “outcomes” data for thousands of students, and we might run various tests to determine if the better outcomes of those in the program are statistically significant so that we can generalize the findings and recommend similar programs elsewhere. Qualitative data in the form of focus groups or interviews can then be used for illustrative purposes, providing more depth to the quantitative analyses. In contrast, formative evaluation attempts to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness). Formative evaluations rely more heavily on qualitative data—case studies, interviews, focus groups. The findings are meant not to generalize beyond the particular but to improve this program. If you are a student seeking to improve your qualitative research skills and you do not care about generating basic research, formative evaluation studies might be an attractive option for you to pursue, as there are always local programs that need evaluation and suggestions for improvement. Again, be very clear about your purpose when talking through your research proposal with your committee.

Action research takes a further step beyond evaluation, even formative evaluation, to being part of the solution itself. This is about as far from basic research as one could get and definitely falls beyond the scope of “science,” as conventionally defined. The distinction between action and research is blurry, the research methods are often in constant flux, and the only “findings” are specific to the problem or case at hand and often are findings about the process of intervention itself. Rather than evaluate a program as a whole, action research often seeks to change and improve some particular aspect that may not be working—maybe there is not enough diversity in an organization or maybe women’s voices are muted during meetings and the organization wonders why and would like to change this. In a further step, participatory action research , those women would become part of the research team, attempting to amplify their voices in the organization through participation in the action research. As action research employs methods that involve people in the process, focus groups are quite common.

If you are working on a thesis or dissertation, chances are your committee will expect you to be contributing to fundamental knowledge and theory ( basic research ). If your interests lie more toward the action end of the continuum, however, it is helpful to talk to your committee about this before you get started. Knowing your purpose in advance will help avoid misunderstandings during the later stages of the research process!

The Research Question

Once you have written your paragraph and clarified your purpose and truly know that this study is the best study for you to be doing right now , you are ready to write and refine your actual research question. Know that research questions are often moving targets in qualitative research, that they can be refined up to the very end of data collection and analysis. But you do have to have a working research question at all stages. This is your “anchor” when you get lost in the data. What are you addressing? What are you looking at and why? Your research question guides you through the thicket. It is common to have a whole host of questions about a phenomenon or case, both at the outset and throughout the study, but you should be able to pare it down to no more than two or three sentences when asked. These sentences should both clarify the intent of the research and explain why this is an important question to answer. More on refining your research question can be found in chapter 4.

Chances are, you will have already done some prior reading before coming up with your interest and your questions, but you may not have conducted a systematic literature review. This is the next crucial stage to be completed before venturing further. You don’t want to start collecting data and then realize that someone has already beaten you to the punch. A review of the literature that is already out there will let you know (1) if others have already done the study you are envisioning; (2) if others have done similar studies, which can help you out; and (3) what ideas or concepts are out there that can help you frame your study and make sense of your findings. More on literature reviews can be found in chapter 9.

In addition to reviewing the literature for similar studies to what you are proposing, it can be extremely helpful to find a study that inspires you. This may have absolutely nothing to do with the topic you are interested in but is written so beautifully or organized so interestingly or otherwise speaks to you in such a way that you want to post it somewhere to remind you of what you want to be doing. You might not understand this in the early stages—why would you find a study that has nothing to do with the one you are doing helpful? But trust me, when you are deep into analysis and writing, having an inspirational model in view can help you push through. If you are motivated to do something that might change the world, you probably have read something somewhere that inspired you. Go back to that original inspiration and read it carefully and see how they managed to convey the passion that you so appreciate.

At this stage, you are still just getting started. There are a lot of things to do before setting forth to collect data! You’ll want to consider and choose a research tradition and a set of data-collection techniques that both help you answer your research question and match all your aims and goals. For example, if you really want to help migrant workers speak for themselves, you might draw on feminist theory and participatory action research models. Chapters 3 and 4 will provide you with more information on epistemologies and approaches.

Next, you have to clarify your “units of analysis.” What is the level at which you are focusing your study? Often, the unit in qualitative research methods is individual people, or “human subjects.” But your units of analysis could just as well be organizations (colleges, hospitals) or programs or even whole nations. Think about what it is you want to be saying at the end of your study—are the insights you are hoping to make about people or about organizations or about something else entirely? A unit of analysis can even be a historical period! Every unit of analysis will call for a different kind of data collection and analysis and will produce different kinds of “findings” at the conclusion of your study. [2]

Regardless of what unit of analysis you select, you will probably have to consider the “human subjects” involved in your research. [3] Who are they? What interactions will you have with them—that is, what kind of data will you be collecting? Before answering these questions, define your population of interest and your research setting. Use your research question to help guide you.

Let’s use an example from a real study. In Geographies of Campus Inequality , Benson and Lee ( 2020 ) list three related research questions: “(1) What are the different ways that first-generation students organize their social, extracurricular, and academic activities at selective and highly selective colleges? (2) how do first-generation students sort themselves and get sorted into these different types of campus lives; and (3) how do these different patterns of campus engagement prepare first-generation students for their post-college lives?” (3).

Note that we are jumping into this a bit late, after Benson and Lee have described previous studies (the literature review) and what is known about first-generation college students and what is not known. They want to know about differences within this group, and they are interested in ones attending certain kinds of colleges because those colleges will be sites where academic and extracurricular pressures compete. That is the context for their three related research questions. What is the population of interest here? First-generation college students . What is the research setting? Selective and highly selective colleges . But a host of questions remain. Which students in the real world, which colleges? What about gender, race, and other identity markers? Will the students be asked questions? Are the students still in college, or will they be asked about what college was like for them? Will they be observed? Will they be shadowed? Will they be surveyed? Will they be asked to keep diaries of their time in college? How many students? How many colleges? For how long will they be observed?

Recommendation

Take a moment and write down suggestions for Benson and Lee before continuing on to what they actually did.

Have you written down your own suggestions? Good. Now let’s compare those with what they actually did. Benson and Lee drew on two sources of data: in-depth interviews with sixty-four first-generation students and survey data from a preexisting national survey of students at twenty-eight selective colleges. Let’s ignore the survey for our purposes here and focus on those interviews. The interviews were conducted between 2014 and 2016 at a single selective college, “Hilltop” (a pseudonym ). They employed a “purposive” sampling strategy to ensure an equal number of male-identifying and female-identifying students as well as equal numbers of White, Black, and Latinx students. Each student was interviewed once. Hilltop is a selective liberal arts college in the northeast that enrolls about three thousand students.

How did your suggestions match up to those actually used by the researchers in this study? It is possible your suggestions were too ambitious? Beginning qualitative researchers can often make that mistake. You want a research design that is both effective (it matches your question and goals) and doable. You will never be able to collect data from your entire population of interest (unless your research question is really so narrow to be relevant to very few people!), so you will need to come up with a good sample. Define the criteria for this sample, as Benson and Lee did when deciding to interview an equal number of students by gender and race categories. Define the criteria for your sample setting too. Hilltop is typical for selective colleges. That was a research choice made by Benson and Lee. For more on sampling and sampling choices, see chapter 5.

Benson and Lee chose to employ interviews. If you also would like to include interviews, you have to think about what will be asked in them. Most interview-based research involves an interview guide, a set of questions or question areas that will be asked of each participant. The research question helps you create a relevant interview guide. You want to ask questions whose answers will provide insight into your research question. Again, your research question is the anchor you will continually come back to as you plan for and conduct your study. It may be that once you begin interviewing, you find that people are telling you something totally unexpected, and this makes you rethink your research question. That is fine. Then you have a new anchor. But you always have an anchor. More on interviewing can be found in chapter 11.

Let’s imagine Benson and Lee also observed college students as they went about doing the things college students do, both in the classroom and in the clubs and social activities in which they participate. They would have needed a plan for this. Would they sit in on classes? Which ones and how many? Would they attend club meetings and sports events? Which ones and how many? Would they participate themselves? How would they record their observations? More on observation techniques can be found in both chapters 13 and 14.

At this point, the design is almost complete. You know why you are doing this study, you have a clear research question to guide you, you have identified your population of interest and research setting, and you have a reasonable sample of each. You also have put together a plan for data collection, which might include drafting an interview guide or making plans for observations. And so you know exactly what you will be doing for the next several months (or years!). To put the project into action, there are a few more things necessary before actually going into the field.

First, you will need to make sure you have any necessary supplies, including recording technology. These days, many researchers use their phones to record interviews. Second, you will need to draft a few documents for your participants. These include informed consent forms and recruiting materials, such as posters or email texts, that explain what this study is in clear language. Third, you will draft a research protocol to submit to your institutional review board (IRB) ; this research protocol will include the interview guide (if you are using one), the consent form template, and all examples of recruiting material. Depending on your institution and the details of your study design, it may take weeks or even, in some unfortunate cases, months before you secure IRB approval. Make sure you plan on this time in your project timeline. While you wait, you can continue to review the literature and possibly begin drafting a section on the literature review for your eventual presentation/publication. More on IRB procedures can be found in chapter 8 and more general ethical considerations in chapter 7.

Once you have approval, you can begin!

Research Design Checklist

Before data collection begins, do the following:

- Write a paragraph explaining your aims and goals (personal/political, practical/strategic, professional/academic).

- Define your research question; write two to three sentences that clarify the intent of the research and why this is an important question to answer.

- Review the literature for similar studies that address your research question or similar research questions; think laterally about some literature that might be helpful or illuminating but is not exactly about the same topic.

- Find a written study that inspires you—it may or may not be on the research question you have chosen.

- Consider and choose a research tradition and set of data-collection techniques that (1) help answer your research question and (2) match your aims and goals.

- Define your population of interest and your research setting.

- Define the criteria for your sample (How many? Why these? How will you find them, gain access, and acquire consent?).

- If you are conducting interviews, draft an interview guide.

- If you are making observations, create a plan for observations (sites, times, recording, access).

- Acquire any necessary technology (recording devices/software).

- Draft consent forms that clearly identify the research focus and selection process.

- Create recruiting materials (posters, email, texts).

- Apply for IRB approval (proposal plus consent form plus recruiting materials).

- Block out time for collecting data.

- At the end of the chapter, you will find a " Research Design Checklist " that summarizes the main recommendations made here ↵

- For example, if your focus is society and culture , you might collect data through observation or a case study. If your focus is individual lived experience , you are probably going to be interviewing some people. And if your focus is language and communication , you will probably be analyzing text (written or visual). ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:16 ). ↵

- You may not have any "live" human subjects. There are qualitative research methods that do not require interactions with live human beings - see chapter 16 , "Archival and Historical Sources." But for the most part, you are probably reading this textbook because you are interested in doing research with people. The rest of the chapter will assume this is the case. ↵

One of the primary methodological traditions of inquiry in qualitative research, ethnography is the study of a group or group culture, largely through observational fieldwork supplemented by interviews. It is a form of fieldwork that may include participant-observation data collection. See chapter 14 for a discussion of deep ethnography.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and research design that focuses on an individual case (e.g., setting, institution, or sometimes an individual) in order to explore its complexity, history, and interactive parts. As an approach, it is particularly useful for obtaining a deep appreciation of an issue, event, or phenomenon of interest in its particular context.

The controlling force in research; can be understood as lying on a continuum from basic research (knowledge production) to action research (effecting change).

In its most basic sense, a theory is a story we tell about how the world works that can be tested with empirical evidence. In qualitative research, we use the term in a variety of ways, many of which are different from how they are used by quantitative researchers. Although some qualitative research can be described as “testing theory,” it is more common to “build theory” from the data using inductive reasoning , as done in Grounded Theory . There are so-called “grand theories” that seek to integrate a whole series of findings and stories into an overarching paradigm about how the world works, and much smaller theories or concepts about particular processes and relationships. Theory can even be used to explain particular methodological perspectives or approaches, as in Institutional Ethnography , which is both a way of doing research and a theory about how the world works.

Research that is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and approach to analyzing qualitative data in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction. This approach was pioneered by the sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967). The elements of theory generated from comparative analysis of data are, first, conceptual categories and their properties and, second, hypotheses or generalized relations among the categories and their properties – “The constant comparing of many groups draws the [researcher’s] attention to their many similarities and differences. Considering these leads [the researcher] to generate abstract categories and their properties, which, since they emerge from the data, will clearly be important to a theory explaining the kind of behavior under observation.” (36).

An approach to research that is “multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials – case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts – that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives." ( Denzin and Lincoln 2005:2 ). Contrast with quantitative research .

Research that contributes knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment.

Research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. There are two kinds: summative and formative .

Research in which an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made, often for the purpose of generalizing to other cases or programs. Generally uses qualitative research as a supplement to primary quantitative data analyses. Contrast formative evaluation research .

Research designed to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness); relies heavily on qualitative research methods. Contrast summative evaluation research

Research carried out at a particular organizational or community site with the intention of affecting change; often involves research subjects as participants of the study. See also participatory action research .

Research in which both researchers and participants work together to understand a problematic situation and change it for the better.

The level of the focus of analysis (e.g., individual people, organizations, programs, neighborhoods).

The large group of interest to the researcher. Although it will likely be impossible to design a study that incorporates or reaches all members of the population of interest, this should be clearly defined at the outset of a study so that a reasonable sample of the population can be taken. For example, if one is studying working-class college students, the sample may include twenty such students attending a particular college, while the population is “working-class college students.” In quantitative research, clearly defining the general population of interest is a necessary step in generalizing results from a sample. In qualitative research, defining the population is conceptually important for clarity.

A fictional name assigned to give anonymity to a person, group, or place. Pseudonyms are important ways of protecting the identity of research participants while still providing a “human element” in the presentation of qualitative data. There are ethical considerations to be made in selecting pseudonyms; some researchers allow research participants to choose their own.

A requirement for research involving human participants; the documentation of informed consent. In some cases, oral consent or assent may be sufficient, but the default standard is a single-page easy-to-understand form that both the researcher and the participant sign and date. Under federal guidelines, all researchers "shall seek such consent only under circumstances that provide the prospective subject or the representative sufficient opportunity to consider whether or not to participate and that minimize the possibility of coercion or undue influence. The information that is given to the subject or the representative shall be in language understandable to the subject or the representative. No informed consent, whether oral or written, may include any exculpatory language through which the subject or the representative is made to waive or appear to waive any of the subject's rights or releases or appears to release the investigator, the sponsor, the institution, or its agents from liability for negligence" (21 CFR 50.20). Your IRB office will be able to provide a template for use in your study .

An administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated. The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research involving human participants. The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects. The IRB has the authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Welcome to Chapter 2

How to Critically Analyze Sources

Learning about synthesis analysis, chapter 2 webinars.

- Student Experience Feedback Buttons

- Library Guide: Research Process This link opens in a new window

- ASC Guide: Outlining and Annotating This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: RefWorks This link opens in a new window

- Library Guide: Copyright Information This link opens in a new window

- Library Research Consultations This link opens in a new window

Jump to DSE Guide

Need help ask us.

- Research Process An introduction to the research process.

- Determining Information Needs A Review Scholarly Journals and Other Information Sources.

- Evaluating Information Sources This page explains how to evaluate the sources of information you locate in your searches.

- Video: Doctoral Level Critique in the Literature Review This video provides doctoral candidates an overview of the importance of doctoral-level critique in the Literature Review in Chapter 2 of their dissertation.

What D oes Synthesis and Analysis Mean?

Synthesis: the combination of ideas to

- show commonalities or patterns

Analysis: a detailed examination

- of elements, ideas, or the structure of something

- can be a basis for discussion or interpretation

Synthesis and Analysis: combine and examine ideas to

- show how commonalities, patterns, and elements fit together

- form a unified point for a theory, discussion, or interpretation

- develop an informed evaluation of the idea by presenting several different viewpoints and/or ideas

- Article Spreadsheet Example (Article Organization Matrix) Use this spreadsheet to help you organize your articles as you research your topic.

Was this resource helpful?

- Next: Library Guide: Research Process >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2023 11:59 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1007176

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 Chapter 2 (Introducing Research)

Joining a Conversation

Typically, when students are taught about citing sources, it is in the context of the need to avoid plagiarism. While that is a valuable and worthwhile goal in its own right, it shifts the focus past one of the original motives for source citation. The goal of referencing sources was originally to situate thoughts in a conversation and to provide support for ideas. If I learned about ethics from Kant, then I cite Kant so that people would know whose understanding shaped my thinking. More than that, if they liked what I had to say, they could read more from Kant to explore those ideas. Of course, if they disliked what I had to say, I could also refer them to Kant’s arguments and use them to back up my own thinking.

For example, you should not take my word for it that oranges contain Vitamin C. I could not cut up an orange and extract the Vitamin C, and I’m only vaguely aware of its chemical formula. However, you don’t have to. The FDA and the CDC both support this idea, and they can provide the documentation. For that matter, I can also find formal articles that provide more information. One of the purposes of a college education is to introduce students to the larger body of knowledge that exists. For example, a student studying marketing is in no small part trying to gain access to the information that others have learned—over time—about what makes for effective marketing techniques. Chemistry students are not required to derive the periodic table on their own once every four years.

In short, college classes (and college essays) are often about joining a broader conversation on a subject. Learning, in general, is about opening one’s mind to the idea that the person doing the learning is not the beginning nor the end of all knowledge.

Remember that most college-level assignments often exist so that a teacher can evaluate a student’s knowledge. This means that displaying more of that knowledge and explaining more of the reasoning that goes into a claim typically does more to fulfill the goals of an assignment. The difference between an essay and a multiple choice test is that an essay typically gives students more room to demonstrate a thought process in action. It is a way of having students “show their work,” and so essays that jump to the end without that work are setting themselves up for failure.

Learning, Not Listing

Aristotle once claimed “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” Many students are familiar with the idea of search . The internet makes it tremendously easy to search for information—and misinformation. It takes a few seconds to find millions of results on almost any topic. However, that is not research. Where, after all, is the re in all of that? The Cambridge Dictionary offers the following definition:

Research (verb): to study a subject in detail, especially in order to discover new information or reach a new understanding.

Nothing about that implies a casual effort to type a couple of words into search engine and assuming that a result on the first screen is probably good enough. Nor does that imply that a weighted or biased search question, like “why is animal testing bad” will get worthwhile results. Instead, research requires that the researcher searches, learns a little, and then searches again . Additionally, the level of detail matters. Research often involves knowing enough to understand the deeper levels of the subject.

For example, if someone is researching the efficacy of animal testing, they might encounter a claim that mice share a certain percentage of their DNA with human beings. Even this is problematic, because measuring DNA by percentage isn’t as simple as it sounds. However, estimates range from 85% to 97.5%, with the latter number being the one that refers to the active or “working” DNA. Unfortunately, the casual reader still knows nothing of value about using mice for human research. Why? Because the casual reader doesn’t know if the testing being done involves the 97.5% or the 2.5%, or even if the test is one where it can be separated.

To put it bluntly, Abraham Lincoln once had a trip to the theater that started 97.5% the same as his other trips to the theater.

In order for casual readers to make sense of this single factoid, they need to know more about DNA and about the nature of the tests being performed on the animals. They probably need to understand biology at least a little. They certainly need to understand math at a high enough level to understand basic statistics. All of this, of course, assumes that the student has also decided that the source itself is worthy of trust. In other words, an activist website found through a search engine that proclaims “mice are almost identical to humans” or “mice lack 300 million base pairs that humans have”. Neither source is lying. Just neither source helps the reader understand what is being talked about (if the sources themselves even understand).

Before a student can write a decent paper, the student needs to have decent information. Finding that information requires research, not search. Often, student writers (and other rhetors) mistakenly begin with a presupposed position that they then try to force into the confines of their rhetoric. Argumentation requires an investigation into an issue before any claim is proffered for discussion. The ‘thesis statement’ comes last; in many ways it is the product of extensive investigation and learning. A student should be equally open to and skeptical of all sources.

Skepticism in Research

Skepticism is not doubting everyone who disagrees with you. True skepticism is doubting all claims equally and requiring every claim to be held to the same burden of proof (not just the claims we disagree with). By far, the biggest misconception novice writers struggle with is the idea that it is okay to use a low-quality source (like a blog, or a news article, or an activist organization) because they got “just facts” from that source.

The assumption seems to be that all presentations of fact are equally presented, or that sources don’t lie. However, even leaving aside that many times people do lie in their own interests, which facts are presented and how they are presented changes immensely. There’s no such thing as “just facts.” The presentation of facts matters, as does how they are gathered. Source evaluation is a fundamental aspect of advanced academic writing.

“Lies” of Omission and Inclusion: One of the simplest ways to misrepresent information is simply to exclude material that could weaken the stance that is favored by the author. This tactic is frequently called stacking the deck , and it is obviously dishonest. However, there is a related problem known as observational bias , wherein the author might not have a single negative intention whatsoever. Instead, xe simply only pays attention to the evidence that supports xir cause, because it’s what’s relevant to xir.

- Arguments in favor of nuclear energy as a “clean” fuel source frequently leave out the problem of what to do with the spent fuel rods (i.e. radioactive waste). Similarly, arguments against nuclear energy frequently count only dramatic failures of older plants and not the safe operation of numerous modern plants; another version is to highlight the health risks of nuclear energy without providing the context of health risks caused by equivalent fuel sources (e.g. coal or natural gas).

- Those who rely on personal observation in support of the idea that Zoomers are lazy might count only the times they see younger people playing games or relaxing, ignoring the number of times they see people that same age working jobs or—more accurately—the times they don’t see people that age because they are too busy helping around the house or doing homework.

A source that simply lists ideas without providing evidence or justifying how the evidence supports its conclusions is likely not a source that meets the rigor needed for an academic argument. While later chapters will go into the subject in greater detail, these guidelines suggest that in general, news media are not ideal sources. Neither are activist webpages, nor are blogs or government outlets. As later chapters will explore, all of these “sources” are not in fact sources of information. Inevitably, these documents to not create information, they simply report it. Instead, finding the original studies (performed by experts, typically controlled for bias, and reviewed by other experts before being published) is a much better alternative.

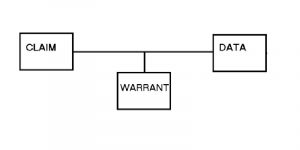

Examining Sources Using the Toulmin Model

On most issues, contradictory evidence exists and the researcher must review the options in a way that establishes one piece of evidence as more verifiable, or as otherwise preferable, to the other. In essence, researchers must be able to compare arguments to one another.

Stephen Toulmin introduced a model of analyzing arguments that broke arguments down into three essential components and three additional factors. His model provides a widely-used and accessible means of both studying and drafting arguments.

The Toulmin model can be complicated with three other components, as well: backing, rebuttals, and qualifiers. Backing represents support of the data (e.g. ‘the thermostat has always been reliable in the past’ or ‘these studies have been replicated dozens of times with many different populations’). Rebuttals, on the other hand, admit limits to the argument (e.g. ‘unless the thermostat is broken’ or ‘if you care about your long-term health’). Finally, qualifiers indicate how certain someone is about the argument (e.g. ‘it is definitely too cold in here’ is different than ‘it might be too cold in here’; likewise, ‘you might want to stop smoking’ is a lot less forceful than ‘you absolutely should stop smoking’).

At a minimum, an argument (either one made by the student or by a source being evaluated) should have all three of the primary components, even if they are incorporated together. However, most developed arguments (even short answers on tests or simple blog posts) should have all six elements in place. If they are missing, it is up to the reader to go looking for what is missing and to try to figure out why it might have been left out.