Untitled Leader

Driving Success: Leadership Lessons from Toyota’s Journey

The Road to Leadership Excellence

The automotive industry, a realm where innovation and precision meet on four wheels, has produced titans that have driven society forward. Among these giants, one name has become synonymous with excellence, efficiency, and enduring success: Toyota. As we delve into the world of leadership, the stories and lessons from Toyota’s remarkable journey emerge as a reservoir of wisdom, a testament to the power of visionary leadership and continuous improvement.

In a landscape marked by rapid technological advancements, shifting consumer demands, and global competition, the story of Toyota stands as a beacon of inspiration for leaders across industries. For over eight decades, this Japanese automaker has transformed from a modest textile machinery company into an international powerhouse, reshaping not only the automotive landscape but also the very essence of leadership.

As we embark on this journey through Toyota’s rich history, we’ll traverse the roads of its humble beginnings, navigate the curves of crisis and innovation, and accelerate through the highways of ethical leadership and sustainability. We will explore how Toyota’s leadership philosophy, known as “The Toyota Way,” has become a lodestar guiding countless organizations worldwide towards operational excellence and ethical leadership.

At the heart of Toyota’s story are individuals who went beyond conventional leadership to inspire change, often in the face of adversity. Figures like Kiichiro Toyoda, Taiichi Ohno, Eiji Toyoda, and Akio Toyoda have left indelible marks on Toyota’s legacy, shaping the company’s culture and its journey toward becoming the world’s largest automaker.

But this article is more than a historical account; it’s a blueprint for leadership development . It is a guide for current and aspiring leaders who seek to lead with purpose, cultivate a culture of continuous improvement, and navigate the complex terrain of modern leadership. Whether you’re leading a small team or a multinational corporation, the principles and stories shared within these pages will resonate, offering practical insights that transcend industry boundaries.

Toyota’s journey is not merely a success story; it’s a tapestry of triumphs and tribulations, of vision and adaptation, of innovation and sustainability. It is a story of leadership that has withstood the test of time and continues to drive forward, setting the course for the future.

So, fasten your seatbelt, for we are about to embark on a transformative journey through the annals of Toyota’s leadership, where each turn of the wheel reveals a new lesson, and each mile traveled brings us closer to the destination of enduring leadership excellence. In the following sections, we will dissect the Toyota Way, explore the pivotal moments in Toyota’s history, and glean insights that will enrich your leadership journey, no matter where it takes you. Welcome to “Driving Success: Leadership Lessons from Toyota’s Journey.”

Toyota’s Historical Context

To truly understand the essence of Toyota’s leadership journey, we must first delve into its historical context, tracing the company’s roots from its humble beginnings to its emergence as a global automotive powerhouse. Toyota’s story is one of evolution and adaptation, shaped by both internal and external forces.

Founding of Toyota and its Early Years

Toyota’s origins can be traced back to the early 20th century when Sakichi Toyoda, a visionary inventor and entrepreneur, founded the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works. While initially specializing in textile machinery, Sakichi Toyoda’s inventive spirit led him to develop the world’s first automatic loom. His pioneering work in automation set the stage for the company’s future endeavors.

In 1937, the automotive division of the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works spun off to become the Toyota Motor Corporation. The transition from looms to automobiles marked a pivotal moment in Toyota’s history. The company’s founders, including Kiichiro Toyoda, Sakichi’s son, envisioned a future where automobiles would play a crucial role in shaping society.

Emergence as a Global Automotive Giant

Toyota’s journey was not without its share of challenges. World War II disrupted production, and the company faced post-war economic hardships. However, it was during these difficult times that Toyota began to lay the groundwork for what would become the Toyota Production System (TPS).

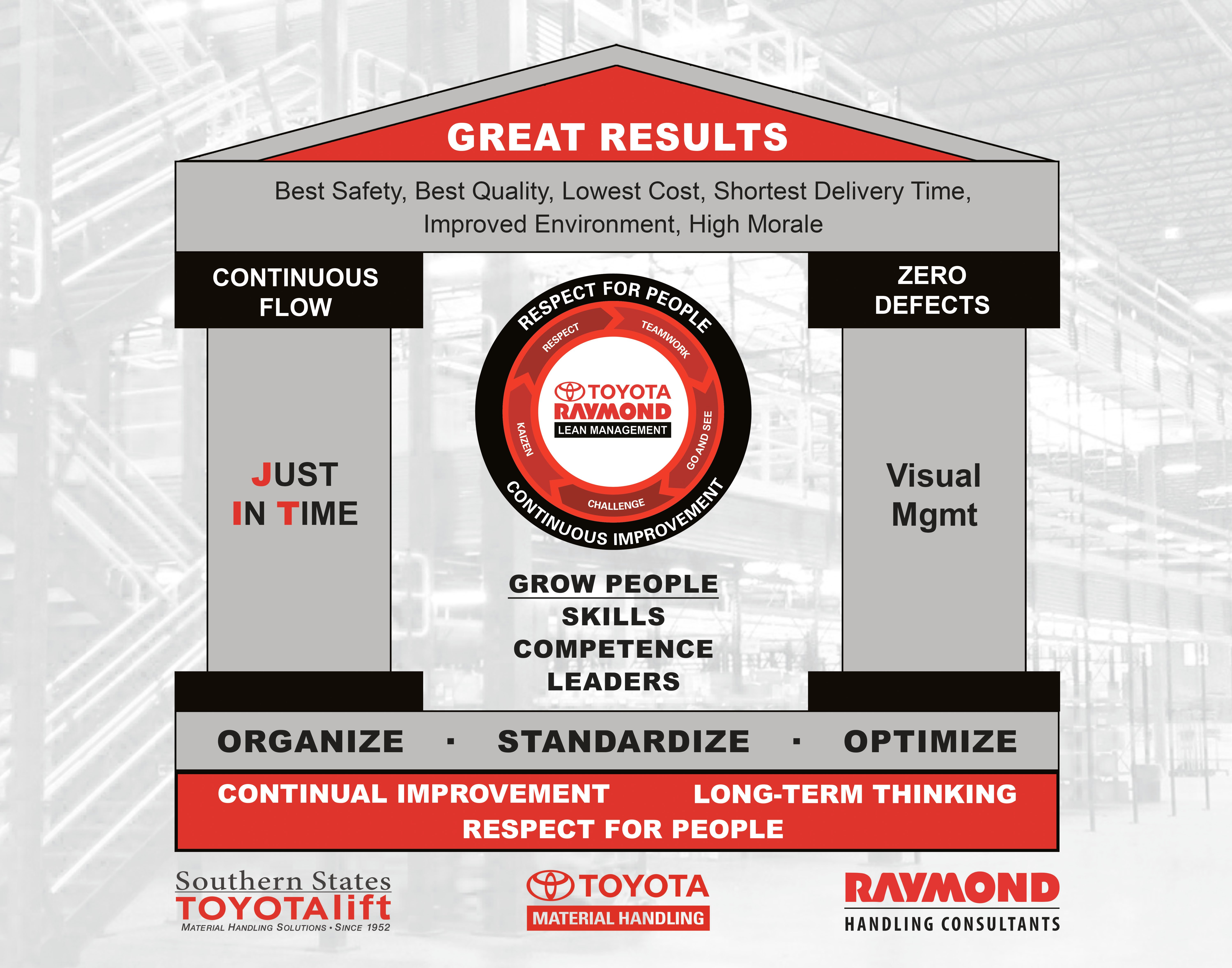

The TPS, developed by Taiichi Ohno, emphasized efficiency, waste reduction, and continuous improvement. It revolutionized manufacturing by introducing concepts like Just-in-Time (JIT) production and Kanban, which would later become synonymous with lean manufacturing practices. These principles would not only transform Toyota but also influence industries worldwide.

By the 1960s, Toyota had become a prominent player in the Japanese and international markets. The introduction of the Toyota Corolla in 1966 marked a significant milestone, as it became one of the best-selling cars globally, solidifying Toyota’s reputation for quality and reliability.

Impact of Historical Events on Toyota’s Leadership and Culture

Historical events and challenges have played a pivotal role in shaping Toyota’s leadership and organizational culture. One such event was the 1973 oil crisis, which exposed the vulnerability of traditional automotive manufacturing methods reliant on large inventories. Toyota’s ability to adapt quickly to changing market conditions through the principles of the TPS allowed it to weather the crisis more effectively than many competitors.

Another transformative period in Toyota’s history occurred during the 1980s and 1990s, as the company expanded its global footprint. Toyota’s leadership recognized the importance of localizing production and adapting to diverse markets, demonstrating a keen understanding of the need for both global standardization and local customization.

Throughout these decades, leaders like Eiji Toyoda, who served as president and later chairman, played instrumental roles in driving Toyota’s global expansion and ensuring that the company remained aligned with its core principles. Their commitment to the Toyota Way and the principles of continuous improvement helped maintain Toyota’s competitive edge.

Understanding Toyota’s historical journey provides a critical backdrop for comprehending the leadership principles that have propelled it to greatness. From a small division within a textile machinery company to a global automotive giant, Toyota’s path has been marked by innovation, resilience, and a steadfast commitment to its core values. In the following sections, we will delve deeper into the leadership philosophies and strategies that have underpinned Toyota’s remarkable evolution.

The Toyota Way: Guiding Leadership Excellence

At the heart of Toyota’s enduring success lies a philosophy that has not only transformed the company itself but has also left an indelible mark on the world of business and leadership – The Toyota Way. This section explores the core principles and philosophies that make up The Toyota Way and how they guide leadership decisions within the organization.

Explanation of the Toyota Production System (TPS)

The cornerstone of The Toyota Way is the Toyota Production System (TPS), often referred to as lean manufacturing. Developed in the post-World War II era by Taiichi Ohno, TPS is a systematic approach to manufacturing that emphasizes efficiency, waste reduction, and the relentless pursuit of perfection.

Continuous Improvement (Kaizen): At the heart of TPS is the concept of Kaizen, which means “continuous improvement.” Toyota leaders and employees are encouraged to constantly seek better ways to do their work. This philosophy fosters a culture of innovation and ensures that no process or product is ever considered perfect.

Respect for People: The Toyota Way places a strong emphasis on respecting and valuing every employee. This respect is not just a platitude but is deeply ingrained in Toyota’s culture. It means involving employees in decision-making, empowering them to make improvements, and recognizing their contributions.

Core Principles of the Toyota Way

Just-in-Time Production: The principle of Just-in-Time (JIT) production aims to eliminate waste by producing only what is needed when it is needed. This reduces excess inventory, minimizes storage costs, and enhances responsiveness to customer demand.

Built-in Quality: Unlike traditional manufacturing approaches that relied on quality control at the end of the production process, TPS focuses on building quality into every step. This prevents defects from occurring in the first place, reducing waste and costs.

How the Toyota Way Guides Leadership Decisions

The Toyota Way is not just a set of principles; it is a mindset that permeates every aspect of the organization. Leaders at Toyota use these principles to guide their decision-making and shape the company’s culture.

Long-Term Perspective: Toyota leaders are known for their long-term perspective. Instead of focusing solely on short-term profits, they consider the long-term impact of their decisions on the company, its employees, and the communities it serves.

Gemba Walks: Toyota leaders practice “Gemba,” which means going to the actual place where work is done. This hands-on approach allows leaders to understand the challenges faced by employees, identify opportunities for improvement, and build stronger relationships within the organization.

Empowerment: Leaders at Toyota empower their employees to take ownership of their work and make decisions that drive improvement. This empowerment fosters a sense of ownership and accountability throughout the organization.

Customer-Centric: Toyota’s leadership prioritizes the customer above all else. Understanding and meeting customer needs are central to Toyota’s success, and leaders constantly seek ways to enhance customer satisfaction.

In essence, The Toyota Way is not just a set of principles but a way of life within the organization. It’s a leadership philosophy that values people, encourages continuous improvement, and strives for excellence in every aspect of the business.

As we delve deeper into Toyota’s leadership journey, we will see how these principles were put into practice by key figures in the company’s history and how they continue to shape Toyota’s approach to leadership in the modern era. The Toyota Way is not only a blueprint for success but also a testament to the enduring power of effective leadership philosophy.

Leadership at the Helm

In any successful organization, leadership is the driving force behind its growth, innovation, and adaptability. Within Toyota, a lineage of visionary leaders has emerged over the years, each contributing to the company’s ascent to global prominence. In this section, we will delve into the key figures who have shaped Toyota’s leadership journey, their distinctive leadership styles, and the profound impact they have had on the company’s culture.

Key Figures in Toyota’s Leadership History

Kiichiro Toyoda: The son of Toyota’s founder, Sakichi Toyoda, Kiichiro Toyoda took the reins as the company transitioned from textile machinery to automobiles. Under his leadership, Toyota expanded into the automotive industry and laid the foundation for what would become the Toyota Production System (TPS). Kiichiro’s vision set the stage for Toyota’s remarkable transformation.

Taiichi Ohno: Often hailed as the father of TPS, Taiichi Ohno’s leadership was instrumental in refining the principles of lean manufacturing. His focus on eliminating waste, creating flow, and continuous improvement revolutionized the way Toyota produced vehicles. Ohno’s leadership was characterized by hands-on problem-solving and a relentless pursuit of efficiency.

Eiji Toyoda: Eiji Toyoda, cousin to Kiichiro Toyoda, served as Toyota’s president and later as chairman. His leadership was marked by a commitment to quality and innovation. Eiji played a pivotal role in shaping Toyota’s global expansion strategy, including establishing Toyota’s presence in the United States. He emphasized the importance of building a culture of excellence within the company.

Akio Toyoda: The current president and CEO of Toyota, Akio Toyoda, is the grandson of Kiichiro Toyoda. Under his leadership, Toyota has navigated through various challenges, including the global financial crisis and quality issues. Akio Toyoda is known for his hands-on approach, commitment to innovation, and dedication to preserving Toyota’s core values while adapting to a rapidly changing industry.

Leadership Styles and Philosophies of Notable Toyota Leaders

Kiichiro Toyoda: Kiichiro exhibited a pioneering and entrepreneurial leadership style. His willingness to take risks and venture into the unknown marked the early days of Toyota’s journey into the automotive industry. He believed in the potential of his team and encouraged them to think outside the box.

Taiichi Ohno: Ohno’s leadership style can be described as pragmatic and results-oriented. He believed in leading by example and spending time on the shop floor to understand and improve processes. His mantra was to “see, hear, and feel” the problems firsthand.

Eiji Toyoda: Eiji Toyoda’s leadership style was characterized by a focus on quality, innovation, and global expansion. He fostered a culture of experimentation and encouraged employees to voice their ideas. Eiji’s leadership legacy is the emphasis on always looking forward and pursuing excellence.

Akio Toyoda: Akio Toyoda’s leadership style combines a deep reverence for Toyota’s heritage with a commitment to adapt to contemporary challenges. He is known for his energetic and inspirational leadership, advocating for “genchi genbutsu” (going to the source to see the problem) and innovation in the face of change.

The Role of Visionary Leadership in Toyota’s Success

Throughout Toyota’s history, visionary leadership has been a consistent theme. These leaders did more than steer the company; they set the course for Toyota’s cultural identity and values. Their ability to foresee industry trends, their dedication to continuous improvement, and their unwavering commitment to quality have been instrumental in Toyota’s remarkable journey.

In the next section of this article, we will explore pivotal moments in Toyota’s history, including how these leaders navigated crises, embraced innovation, and adapted to changing landscapes. Their leadership philosophies and strategies provide valuable lessons for leaders in any field who aspire to drive success through visionary, purpose-driven leadership. Toyota’s story demonstrates that effective leadership is not only about achieving short-term goals but also about creating a legacy that endures for generations to come.

Lessons from Crisis and Innovation

One of the defining features of Toyota’s leadership journey is its ability to navigate through crises and drive innovation, often emerging from adversity stronger than before. In this section, we will explore how Toyota’s leadership responded to pivotal moments in the company’s history, demonstrating resilience, adaptability, and a commitment to continuous improvement.

Toyota’s Response to the 1973 Oil Crisis

The 1973 oil crisis was a seismic event that sent shockwaves through the global automotive industry. Skyrocketing oil prices and fuel shortages threatened the viability of large, gas-guzzling vehicles that many automakers were producing. Toyota, under the leadership of Eiji Toyoda and Taiichi Ohno, responded with agility and innovation.

Embracing Efficiency: Toyota recognized the need for more fuel-efficient vehicles and shifted its focus towards compact and economical cars. The introduction of the Toyota Corolla in 1966 and the Toyota Starlet in 1973 showcased the company’s commitment to producing vehicles that aligned with the changing market demands.

Lean Manufacturing Triumphs: The principles of the Toyota Production System (TPS) proved invaluable during this crisis. TPS allowed Toyota to adapt quickly to changing production requirements and reduce waste. The ability to produce smaller, more fuel-efficient cars efficiently gave Toyota a competitive edge.

Commitment to Quality: While adapting to market demands, Toyota maintained its unwavering commitment to quality. This approach not only solidified Toyota’s reputation for reliability but also helped the company gain consumer trust during a time of uncertainty.

Coping with Quality Issues (e.g., Recall Crisis in 2009)

Toyota’s reputation for quality took a severe hit in 2009 when a series of recalls related to unintended acceleration issues rocked the company. The crisis tested the leadership of then-President Akio Toyoda.

Immediate Action and Transparency: Akio Toyoda’s leadership during this crisis was marked by a swift response. He personally apologized and acknowledged the issues, demonstrating a commitment to transparency and accountability. Toyota launched extensive investigations, recalled affected vehicles, and implemented rigorous quality control measures.

Learning and Improvement: Toyota used the recall crisis as an opportunity to reevaluate its processes and culture. The company reaffirmed its commitment to quality and customer safety, implementing comprehensive changes to prevent similar issues in the future. This experience reinforced the importance of continuous improvement and a culture of learning.

Innovations and Breakthroughs in Automotive Technology

In addition to crisis management, Toyota’s leadership has consistently driven innovation in the automotive industry. Key innovations include:

Hybrid Technology: Toyota’s pioneering hybrid technology, exemplified by the Prius, revolutionized the automotive landscape. Under the leadership of Akio Toyoda, Toyota continued to invest in hybrid and electric vehicle technology, contributing to the global shift toward more sustainable transportation.

Autonomous Driving and Mobility Solutions: Toyota has been at the forefront of developing autonomous driving technologies and mobility solutions. The company’s investments in artificial intelligence, robotics, and connected vehicles reflect its commitment to shaping the future of transportation.

Environmental Sustainability: Toyota has been a leader in environmental sustainability, not only in its vehicle technology but also in its manufacturing processes. The company has made significant strides in reducing its environmental footprint and promoting sustainability throughout the automotive industry.

The lessons from these moments in Toyota’s history are clear: effective leadership requires the ability to adapt to external challenges, maintain a commitment to core values, and leverage innovation as a strategic asset. Toyota’s resilience in the face of adversity and its dedication to continuous improvement have been key factors in its ongoing success. These lessons are invaluable for leaders in any industry, demonstrating that with the right approach, crises can be turned into opportunities for growth and innovation.

Building a Culture of Continuous Improvement

Toyota’s ascent to automotive greatness is inseparable from its commitment to a culture of continuous improvement. In this section, we will explore how Toyota’s leadership instilled and nurtured this culture, emphasizing the role of frontline employees and the enduring impact of their approach.

The Role of Frontline Employees in Toyota’s Improvement Process

Empowering the Frontline: Toyota’s leadership has long recognized the invaluable insights and expertise of frontline employees. They are the ones who witness processes firsthand and are best positioned to identify areas for improvement. Toyota’s culture encourages employees to speak up, voice concerns, and suggest innovations.

Kaizen in Action: The concept of Kaizen, or continuous improvement, is not limited to management. It permeates every level of the organization, with employees actively participating in Kaizen activities. Workers are encouraged to seek out inefficiencies, suggest improvements, and experiment with new ideas, creating a bottom-up approach to innovation.

Respect for People: A fundamental aspect of Toyota’s culture is respect for people. This goes beyond words; it is reflected in how leaders and employees interact. Leaders actively listen to employees, value their contributions, and provide the necessary support for implementing improvements.

Encouraging Employee Involvement and Empowerment

Quality Circles: Toyota was a pioneer in the use of Quality Circles, small groups of employees who meet regularly to discuss and solve work-related problems. These circles foster a sense of ownership and accountability, as well as a culture of collaboration.

Training and Development: Toyota invests significantly in training and developing its employees. This includes not only technical skills but also leadership and problem-solving capabilities. Leadership at Toyota recognizes that an empowered and skilled workforce is essential for sustained improvement.

Recognition and Rewards: Toyota’s leadership understands the importance of recognizing and rewarding employees for their contributions to continuous improvement. This recognition can take various forms, from monetary rewards to public acknowledgment of achievements.

How Leaders Instill a Mindset of Continuous Improvement

Leading by Example: Toyota’s leaders lead by example, demonstrating their commitment to continuous improvement through their actions. They actively engage in problem-solving, participate in Gemba walks (going to the workplace to observe and engage), and encourage employees to do the same.

Alignment with Core Principles: The principles of The Toyota Way, including Just-in-Time production and built-in quality, are not just slogans but guiding lights for decision-making. Leaders consistently refer to these principles when addressing challenges and making improvements.

Long-Term Perspective: Toyota’s leadership maintains a long-term perspective. They understand that continuous improvement is not a quick fix but a journey that requires dedication and patience. This perspective helps leaders stay committed to the process even when results may not be immediate.

Toyota’s emphasis on a culture of continuous improvement is not merely a management strategy but a way of life within the organization. It is a commitment to excellence that extends beyond the production line to every facet of the company. This culture has been a key driver of Toyota’s ability to adapt, innovate, and excel in a rapidly changing industry.

In the subsequent sections of this article, we will delve into Toyota’s global perspective, its commitment to ethical leadership and sustainability, and the collaborative strategies that have contributed to its supply chain resilience. The lessons from Toyota’s culture of continuous improvement serve as a blueprint for leaders in any industry who seek to foster innovation, empower their teams, and drive sustained success.

The Global Perspective

Toyota’s journey to leadership isn’t confined to its home market in Japan. It’s a story of expanding horizons, embracing diverse cultures, and adapting to global markets while upholding the principles of The Toyota Way. In this section, we explore Toyota’s international expansion and the leadership challenges and strategies it encountered on the global stage.

Toyota’s Expansion into International Markets

Early Global Ventures: Toyota’s leadership recognized the need for international expansion early on. In the 1950s and 1960s, the company began exporting vehicles to the United States and establishing overseas production facilities. This marked the beginning of Toyota’s global presence.

Balancing Global and Local: A key challenge for Toyota’s leadership was striking the right balance between global standardization and local adaptation. While maintaining consistent quality and production standards globally, Toyota also acknowledged the importance of tailoring products and operations to suit the preferences and regulations of local markets.

Leadership Challenges in Managing a Global Organization

Cultural Diversity: Toyota’s leadership faced the complex task of navigating cultural diversity across different regions. Understanding and respecting cultural nuances while maintaining a unified corporate culture posed challenges and required a keen sense of cultural intelligence.

Supply Chain Management: As Toyota’s global footprint expanded, so did the complexity of its supply chain. Effective leadership was required to ensure the smooth flow of parts and materials across borders, particularly in times of economic or political upheaval.

Global Leadership Development: Toyota recognized the importance of nurturing leaders who could operate effectively in an international context. Leadership development programs were designed to equip leaders with the skills and mindset needed to manage diverse teams and markets.

Balancing Global Standards with Local Adaptation

Standardization: Toyota’s commitment to quality and efficiency led to the development of global standards for manufacturing and product quality. These standards ensured consistency in the company’s operations worldwide.

Local Responsiveness: While standardization was essential, Toyota also acknowledged the need for localization. Products were adapted to suit local preferences, and production processes were adjusted to meet specific market demands.

Global Supply Chain Resilience: Toyota’s leadership recognized the importance of building a resilient global supply chain. Diversification of suppliers and production sites helped mitigate risks associated with natural disasters, economic fluctuations, and other unforeseen challenges.

The global perspective in Toyota’s leadership journey teaches us that effective leadership transcends borders. It requires an appreciation for cultural diversity, adaptability to changing market dynamics, and a commitment to maintaining a consistent standard of quality and innovation across diverse markets. Toyota’s ability to harmonize global and local perspectives has been a hallmark of its success.

In the subsequent sections of this article, we will explore Toyota’s commitment to ethical leadership and sustainability, its collaborative strategies within the automotive industry, and the future of leadership at Toyota as it faces technological disruptions and evolving customer expectations. These aspects of Toyota’s journey offer valuable insights for leaders navigating an increasingly interconnected and globalized world.

Ethical Leadership and Sustainability

Toyota’s leadership journey is not solely defined by its business success but also by its unwavering commitment to ethical leadership and sustainability. In this section, we will explore how Toyota’s leaders have navigated ethical challenges and championed sustainability, emphasizing the impact of responsible leadership in shaping the company’s long-term success.

Toyota’s Commitment to Environmental Sustainability

Pioneering Hybrid Technology: Toyota’s dedication to environmental sustainability was exemplified by its development of hybrid technology, most notably in the Toyota Prius. Released in 1997, the Prius was the world’s first mass-produced hybrid vehicle. This move was not just a business decision but a statement of Toyota’s commitment to reducing its environmental footprint.

Innovations in Green Technology: Toyota has continued to invest heavily in research and development, aiming to reduce emissions and improve fuel efficiency. The company’s leadership has recognized that sustainability is not just a moral imperative but also a competitive advantage in a world increasingly concerned with environmental issues.

Ethical Challenges Faced by Toyota and Their Resolution

Quality and Safety Recalls: As mentioned earlier, Toyota faced a significant quality and safety recall crisis in 2009. The way Toyota’s leadership responded to this crisis highlighted the importance of ethical responsibility. Acknowledging the issues, taking swift action, and prioritizing customer safety were at the core of the response.

Supply Chain Responsibility: Toyota’s leadership extended its ethical considerations to its supply chain, ensuring that suppliers adhere to ethical standards and practices. This commitment to responsible sourcing reflects Toyota’s dedication to ethical leadership throughout its ecosystem.

The Importance of Ethical Leadership in Long-Term Success

Building Trust: Toyota’s commitment to ethical leadership has helped build and maintain trust with customers, employees, and stakeholders. Trust is a crucial asset in today’s business environment, and ethical leadership is instrumental in its cultivation.

Enhancing Reputation: Ethical leadership enhances a company’s reputation, which, in turn, can have a positive impact on brand loyalty and market share. Toyota’s reputation for quality and ethical conduct has contributed to its longevity and competitiveness.

Mitigating Risk: Ethical leadership helps mitigate various risks, including legal, financial, and reputational. By adhering to ethical standards, Toyota has reduced its exposure to potential liabilities and crises.

Sustainable Business Model: Ethical leadership aligns with the principles of sustainability, promoting responsible stewardship of resources and fostering long-term business sustainability.

Toyota’s journey underscores the significance of ethical leadership in maintaining a resilient and reputable organization. The ability to respond to ethical challenges with integrity and transparency has been a distinguishing feature of Toyota’s leadership culture.

In the subsequent sections of this article, we will delve into Toyota’s collaborative leadership strategies with suppliers and partners, as well as the company’s preparations for the future in the face of technological disruptions. Toyota’s commitment to ethical leadership and sustainability serves as a beacon for leaders across industries, emphasizing that enduring success is not solely measured by financial achievements but also by the ethical legacy a company leaves behind.

Collaborative Leadership

Collaboration has been a cornerstone of Toyota’s leadership philosophy, shaping its relationships with suppliers, partners, and competitors. In this section, we will explore how Toyota’s collaborative approach has been instrumental in its success, highlighting the strategies and lessons that leaders can draw from this cooperative mindset.

Toyota’s Approach to Collaboration with Suppliers and Partners

Building Strong Supplier Relationships: Toyota’s leadership recognizes that suppliers are essential partners in the production process. Toyota has a long history of building strong, mutually beneficial relationships with its suppliers. This includes fostering trust, providing support, and collaborating on product and process improvements.

The Toyota Production System (TPS) and Suppliers: TPS extends beyond Toyota’s production lines. The company encourages suppliers to adopt TPS principles, such as Just-in-Time (JIT) production and continuous improvement, which not only improve efficiency but also strengthen the entire supply chain.

Lessons in Collaborative Leadership from Toyota

Trust and Transparency: Trust forms the bedrock of successful collaboration. Toyota’s leadership places a high premium on transparency, openly sharing information with partners and suppliers. Trust is cultivated through consistent actions that demonstrate a commitment to collaboration.

Long-Term Perspective: Toyota’s leadership takes a long-term view of its relationships. Collaborative partnerships are not seen as transactional but as enduring bonds that contribute to the success of all parties involved. This perspective encourages partners to invest in the relationship for the long haul.

Shared Goals and Values: Collaboration is most effective when all parties share common goals and values. Toyota aligns itself with suppliers and partners who are committed to the same principles of quality, continuous improvement, and customer satisfaction.

The Impact of Collaborative Leadership on Supply Chain Resilience

Supply Chain Resilience: Toyota’s collaborative approach to supply chain management has contributed to its resilience in the face of various challenges, including natural disasters, economic fluctuations, and global disruptions. Strong relationships with suppliers allow for more effective risk mitigation and rapid recovery.

Adaptation to Market Dynamics: Collaborative leadership enables Toyota to adapt to changing market dynamics swiftly. By working closely with suppliers, the company can adjust production schedules, respond to shifts in demand, and introduce new products more efficiently.

The Broader Industry Impact

Toyota’s commitment to collaborative leadership has had a profound influence on the automotive industry. Many of the principles and practices developed by Toyota have been adopted by other automakers and have become industry standards. The collaborative mindset that Toyota promotes has fostered innovation and raised the bar for operational excellence.

Toyota’s journey is a testament to the power of collaboration in leadership. The company’s ability to cultivate strong relationships with suppliers and partners has not only enhanced its competitiveness but has also contributed to its resilience and adaptability. The lessons from Toyota’s collaborative leadership extend beyond the automotive industry, serving as an inspiration for leaders in various fields who seek to forge strong, enduring partnerships and build a culture of shared success. In the following sections, we will explore the future of leadership at Toyota as it confronts technological disruptions and evolving customer expectations, ensuring that the company remains at the forefront of innovation and excellence.

Navigating the Future: Leadership in a Technological Landscape

As Toyota’s illustrious journey through history has demonstrated, effective leadership isn’t confined to past achievements; it’s a forward-looking endeavor. In this section, we explore Toyota’s preparations for the future, which involve embracing technological disruptions, addressing changing customer expectations, and redefining what leadership means in a rapidly evolving automotive landscape.

Technological Disruptions and Innovation

Embracing Electric Vehicles (EVs): Toyota has recognized the shift towards electric mobility and has embarked on an ambitious path to develop a wide range of electric vehicles. This shift underscores Toyota’s commitment to sustainability and its responsiveness to evolving consumer preferences.

Investing in Autonomous Driving: Toyota is actively investing in autonomous driving technology, acknowledging the transformative potential of self-driving vehicles. The company envisions a future where mobility is safer and more accessible through autonomous transportation solutions.

The Role of Leadership in Navigating Technological Changes

Visionary Leadership: Toyota’s leadership, under the guidance of figures like Akio Toyoda, has demonstrated a visionary outlook by embracing technologies that will shape the future of mobility. This involves not only recognizing emerging trends but also committing to substantial investments in research and development.

Managing Change: Effective leaders at Toyota understand the importance of managing change within the organization. Adapting to new technologies requires a culture that embraces innovation, encourages experimentation, and provides the necessary resources for technological advancements.

Addressing Evolving Customer Expectations

Customer-Centric Approach: Toyota’s leadership has always been deeply customer-centric, and this approach remains central in the face of technological changes. Understanding and anticipating customer needs are critical in the development of new technologies and mobility solutions.

Personalization and Connectivity: Toyota is responding to changing customer expectations by offering more personalized and connected vehicle experiences. This includes features like advanced infotainment systems, connectivity with mobile devices, and a focus on enhancing the overall driving experience.

The Future of Leadership at Toyota

Leaders as Innovators: The future of leadership at Toyota will see leaders embracing their roles as innovators and disruptors. They will need to challenge conventional thinking, foster a culture of experimentation, and drive forward-thinking solutions.

Sustainability Champions: Ethical leadership and sustainability will remain at the forefront of Toyota’s leadership philosophy. Leaders will continue to champion responsible business practices and eco-friendly technologies to address global environmental challenges.

Global and Local Collaboration: The global perspective in leadership will become increasingly important as Toyota continues to expand its operations. Leaders will need to navigate the complexities of operating in diverse markets while maintaining a cohesive organizational culture.

Toyota’s leadership journey is far from over; it’s an ongoing saga of adaptability, innovation, and a commitment to values that have withstood the test of time. As the automotive industry undergoes unprecedented changes, Toyota’s leaders are poised to guide the company into a future where technology, sustainability, and customer-centricity will define success. The lessons from Toyota’s journey serve as a guidepost for leaders across industries, reminding us that effective leadership isn’t about resting on past laurels but about navigating the ever-evolving landscape with vision and purpose.

Steering Towards a Legacy: Toyota’s Leadership Journey

As we conclude our exploration of Toyota’s remarkable leadership journey, it becomes evident that the company’s success is a testament to the enduring principles, adaptive strategies, and visionary leaders that have shaped its path. Toyota’s legacy isn’t just about producing world-class automobiles; it’s about leadership that has redefined industry standards, inspired countless organizations, and left an indelible mark on the world of business and leadership.

Key Takeaways from Toyota’s Leadership Journey

The Toyota Way: At the core of Toyota’s leadership success lies “The Toyota Way.” This philosophy, which emphasizes continuous improvement, respect for people, and a commitment to quality, has not only guided Toyota but has also become a source of inspiration for leaders across industries.

Adaptability and Resilience: Toyota’s ability to navigate through crises, embrace innovation, and adapt to changing market dynamics underscores the importance of adaptability and resilience in leadership. The company’s leadership responded to challenges with determination, ensuring that Toyota emerged stronger from each trial.

Collaboration and Ethical Leadership: Toyota’s commitment to collaboration with suppliers, partners, and a focus on ethical leadership has been central to its success. Trust, transparency, and shared values have paved the way for enduring relationships and industry-changing partnerships.

Sustainability and Customer-Centricity: Toyota’s leadership has shown that an unwavering commitment to sustainability and a deep understanding of customer needs are crucial in building a resilient and customer-focused organization.

The Ongoing Journey of Leadership at Toyota

As Toyota navigates the ever-evolving landscape of the automotive industry, its leadership faces new challenges and opportunities. The transition to electric vehicles, the pursuit of autonomous driving, and the commitment to sustainability will continue to shape Toyota’s leadership journey.

Leaders as Innovators: Toyota’s leaders will need to embrace their roles as innovators, leading the charge in technological advancements, and shaping the future of mobility.

Global Leadership: Operating in diverse markets across the globe will require leaders who can bridge cultures, manage global supply chains, and drive local adaptation while preserving the company’s core values.

Sustainability Champions: Toyota’s leadership will continue to advocate for sustainability, not just as a corporate responsibility but as a fundamental driver of success in a world increasingly focused on environmental issues.

A Source of Inspiration for Leaders Everywhere

Toyota’s leadership journey serves as a source of inspiration for leaders everywhere, offering valuable lessons in adaptability, collaboration, ethical conduct, and a commitment to continuous improvement. It demonstrates that effective leadership is not a fixed state but an ongoing process of growth, learning, and adaptation.

In closing, Toyota’s legacy is a testament to the transformative power of visionary leadership that is grounded in principles, embraces change, and values people. It reminds us that leadership isn’t just about reaching the pinnacle of success; it’s about setting a course for enduring excellence and leaving a legacy that transcends generations. Toyota’s journey is a beacon for leaders across industries, inviting them to embark on their own transformative quests, shaping the future with resilience, innovation, and unwavering commitment to their core values.

Similar Posts

Leadership Legacy: Denise Morrison’s Trailblazing Journey at Campbell’s Soup

Unveiling the Leadership Journey of Denise Morrison Leadership is a journey fraught with challenges, triumphs, and transformation. It is an art that requires courage, vision, and the ability to navigate uncharted waters. Over the years, the corporate landscape has witnessed exceptional leaders who have left an indelible mark on their organizations and industries. One such…

The Timeless Leadership Lessons from Sitting Bull: A Study in Resilience, Vision, and Courage

Unveiling the Leadership Wisdom of Sitting Bull In today’s fast-paced and competitive world, the art of leadership has never been more important. As we navigate through the complexities of the modern era, it is essential for leaders to draw inspiration and wisdom from the past, from individuals who have demonstrated exceptional leadership skills and left…

From Winning to Succeeding: How Shifting Your Focus Can Lead to Sustainable Growth

Winning vs. Succeeding: Understanding the Difference In the world of sports, business, and politics, the terms “winning” and “succeeding” are often used interchangeably. However, these two concepts are fundamentally different, and understanding this difference is crucial for leaders in any industry. Winning is typically defined as achieving a specific goal or beating an opponent in…

Elevating Leadership: Guiding with Service, Empowering through Example

Navigating Leadership’s True North: A Journey into Service-Centered Excellence In the realm of organizational dynamics and human interaction, the concept of leadership stands as a steadfast beacon guiding teams and individuals towards shared goals and aspirations. However, as the winds of change sweep through the landscapes of industries and institutions, it becomes increasingly vital to…

Cultivating Peak Performance: The Path to Becoming a Top Leader

Cultivating Excellence: The Path to Leadership Greatness In today’s fast-paced and competitive world, the demand for exceptional leadership is more significant than ever. Organizations seek leaders who can navigate complex challenges, inspire teams, and drive transformative change. If you aspire to be a top leader, it is essential to recognize that the journey begins with…

The Obama Leadership Compass: Charting a Course for Transformative Change

Embarking on Obama’s Leadership Journey Leadership is an enduring and evolving concept that continues to captivate the attention of people worldwide. In a rapidly changing world, it is essential for individuals to understand and learn from the journeys of successful leaders who have demonstrated exceptional abilities to navigate through complex challenges and inspire others. Barack…

- About / Contact

- Privacy Policy

- Alphabetical List of Companies

- Business Analysis Topics

Toyota’s Organizational Culture: An Analysis

Toyota Motor Corporation’s organizational culture defines the responses of employees to challenges that the company faces in the market. As a global leader in the automobile market, Toyota uses its work culture to maximize human resource capabilities in innovation. The company benefits from its organizational culture in terms of motivating workers to adopt effective problem-solving behaviors. The characteristics of the organizational culture indicate a careful approach in facilitating organizational learning in the automotive business. As Toyota’s organizational structure (company structure) evolves, so does its business culture. The automaker’s company culture highlights the importance of developing an appropriate workplace culture to support global business success.

Toyota’s culture effectively supports endeavors in innovation and continuous improvement. An understanding of this business culture is beneficial to identifying beliefs and principles that contribute to the strength of the company and its brands against competitors, like Tesla , Ford , Nissan, BMW , and General Motors . Despite the tough rivalry noted in the Five Forces analysis of Toyota , the company maintains competitive human resources with the help of its organizational culture.

Features of Toyota’s Organizational Culture

Toyota’s organizational culture adapts to international business needs, such as legal requirements and emerging concerns in the market. In the past, the automaker’s business culture emphasized a sense of hierarchy and secrecy, which translated to employees’ perception that all decisions must come from the headquarters in Japan. Today, the characteristics of Toyota’s organizational culture are as follows, arranged according to significance:

- Continuous improvement through learning

Teamwork . Toyota uses teams in most of its business areas. One of the company’s principles is that the constructive collaboration of teamwork leads to greater capabilities and success in the automotive industry. This part of the work culture emphasizes the involvement of employees in their respective teams. To ensure that teamwork is properly integrated in the organizational culture, every Toyota employee goes through a teambuilding training program. Through this emphasis on teamwork, the company culture aligns with job design and human resource development in Toyota’s operations management .

Continuous Improvement through Learning . Toyota’s organizational culture facilitates the development of the firm as a learning organization. A learning organization utilizes information gained through the activities of individual workers to develop policies and programs for better results. The company’s business culture highlights learning as a way of developing solutions to problems, such as problems in vehicle manufacturing, people’s mobility, and the transportation sector. In this way, improvements in business processes and outputs fulfill Toyota’s vision statement and mission statement with the support of this organizational culture.

Quality . Quality is at the heart of Toyota’s organizational culture. The success of the company is typically attributed to its ability to provide high-quality automobiles. To effectively integrate quality in its work culture, the firm uses the principles of The Toyota Way, which emphasizes quality in solving problems. These principles define the business management approaches used in the automotive company. This quality factor in the business culture translates to quality in human resource management, worker behaviors, and organizational outputs, such as cars. Thus, the competitive advantages noted in the SWOT analysis of Toyota are partly dependent on this quality-focused characteristic of the corporate culture.

Secrecy . Toyota’s organizational culture has a considerable degree of secrecy. However, the level of secrecy has declined through the years, especially after the automaker’s reorganization in 2013. In the old company culture, information about problems encountered in the workplace must go through the firm’s headquarters in Japan. Today, the company’s organizational culture does not emphasize secrecy as much. For example, many of the problems encountered in manufacturing plants in the U.S. are now disseminated, analyzed, and solved within the North America business unit of Toyota.

Key Points on Toyota’s Culture

The characteristics of Toyota’s organizational culture enable the business to continue growing. The company’s innovation capabilities are based on continuous improvement through learning. Quality improvement and problem-solving effectiveness in the automotive business are achieved through the activities of work teams and individual employees. These cultural traits ensure human resource support for strategies addressing external factors linked to the opportunities and threats described in the PESTLE/PESTEL analysis of Toyota . However, secrecy in Toyota’s business culture presents drawbacks because it reduces organizational flexibility in rapid problem-solving endeavors.

- Kaila, H. L. (2023). Linking safety culture to company values and legacy. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 18 (1).

- Toyota Code of Conduct .

- Toyota Motor Corporation – Form 20-F .

- Toyota Motor Corporation – Philosophy .

- U.S. Department of Commerce – International Trade Administration – Automotive Industry .

- Zhang, W., Zeng, X., Liang, H., Xue, Y., & Cao, X. (2023). Understanding how organizational culture affects innovation performance: A management context perspective. Sustainability, 15 (8), 6644.

- Copyright by Panmore Institute - All rights reserved.

- This article may not be reproduced, distributed, or mirrored without written permission from Panmore Institute and its author/s.

- Educators, Researchers, and Students: You are permitted to quote or paraphrase parts of this article (not the entire article) for educational or research purposes, as long as the article is properly cited and referenced together with its URL/link.

How Toyota Turns Workers Into Problem Solvers

Sarah Jane Johnston: Why study Toyota? With all the books and articles on Toyota, lean manufacturing, just-in-time, kanban systems, quality systems, etc. that came out in the 1980s and 90s, hasn't the topic been exhausted?

Steven Spear: Well, this has been a much-researched area. When Kent Bowen and I first did a literature search, we found nearly 3,000 articles and books had been published on some of the topics you just mentioned.

However, there was an apparent discrepancy. There had been this wide, long-standing recognition of Toyota as the premier automobile manufacturer in terms of the unmatched combination of high quality, low cost, short lead-time and flexible production. And Toyota's operating system—the Toyota Production System—had been widely credited for Toyota's sustained leadership in manufacturing performance. Furthermore, Toyota had been remarkably open in letting outsiders study its operations. The American Big Three and many other auto companies had done major benchmarking studies, and they and other companies had tried to implement their own forms of the Toyota Production System. There is the Ford Production System, the Chrysler Operating System, and General Motors went so far as to establish a joint venture with Toyota called NUMMI, approximately fifteen years ago.

However, despite Toyota's openness and the genuinely honest efforts by other companies over many years to emulate Toyota, no one had yet matched Toyota in terms of having simultaneously high-quality, low-cost, short lead-time, flexible production over time and broadly based across the system.

It was from observations such as these that Kent and I started to form the impression that despite all the attention that had already been paid to Toyota, something critical was being missed. Therefore, we approached people at Toyota to ask what they did that others might have missed.

Q: What did they say?

A: To paraphrase one of our contacts, he said, "It's not that we don't want to tell you what TPS is, it's that we can't. We don't have adequate words for it. But, we can show you what TPS is."

Over about a four-year period, they showed us how work was actually done in practice in dozens of plants. Kent and I went to Toyota plants and those of suppliers here in the U.S. and in Japan and directly watched literally hundreds of people in a wide variety of roles, functional specialties, and hierarchical levels. I personally was in the field for at least 180 working days during that time and even spent one week at a non-Toyota plant doing assembly work and spent another five months as part of a Toyota team that was trying to teach TPS at a first-tier supplier in Kentucky.

Q: What did you discover?

A: We concluded that Toyota has come up with a powerful, broadly applicable answer to a fundamental managerial problem. The products we consume and the services we use are typically not the result of a single person's effort. Rather, they come to us through the collective effort of many people each doing a small part of the larger whole. To a certain extent, this is because of the advantages of specialization that Adam Smith identified in pin manufacturing as long ago as 1776 in The Wealth of Nations . However, it goes beyond the economies of scale that accrue to the specialist, such as skill and equipment focus, setup minimization, etc.

The products and services characteristic of our modern economy are far too complex for any one person to understand how they work. It is cognitively overwhelming. Therefore, organizations must have some mechanism for decomposing the whole system into sub-system and component parts, each "cognitively" small or simple enough for individual people to do meaningful work. However, decomposing the complex whole into simpler parts is only part of the challenge. The decomposition must occur in concert with complimentary mechanisms that reintegrate the parts into a meaningful, harmonious whole.

This common yet nevertheless challenging problem is obviously evident when we talk about the design of complex technical devices. Automobiles have tens of thousands of mechanical and electronic parts. Software has millions and millions of lines of code. Each system can require scores if not hundreds of person-work-years to be designed. No one person can be responsible for the design of a whole system. No one is either smart enough or long-lived enough to do the design work single handedly.

Furthermore, we observe that technical systems are tested repeatedly in prototype forms before being released. Why? Because designers know that no matter how good their initial efforts, they will miss the mark on the first try. There will be something about the design of the overall system structure or architecture, the interfaces that connect components, or the individual components themselves that need redesign. In other words, to some extent the first try will be wrong, and the organization designing a complex system needs to design, test, and improve the system in a way that allows iterative congruence to an acceptable outcome.

The same set of conditions that affect groups of people engaged in collaborative product design affect groups of people engaged in the collaborative production and delivery of goods and services. As with complex technical systems, there would be cognitive overload for one person to design, test-in-use, and improve the work systems of factories, hotels, hospitals, or agencies as reflected in (a) the structure of who gets what good, service, or information from whom, (b) the coordinative connections among people so that they can express reliably what they need to do their work and learn what others need from them, and (c) the individual work activities that create intermediate products, services, and information. In essence then, the people who work in an organization that produces something are simultaneously engaged in collaborative production and delivery and are also engaged in a collaborative process of self-reflective design, "prototype testing," and improvement of their own work systems amidst changes in market needs, products, technical processes, and so forth.

It is our conclusion that Toyota has developed a set of principles, Rules-in-Use we've called them, that allow organizations to engage in this (self-reflective) design, testing, and improvement so that (nearly) everyone can contribute at or near his or her potential, and when the parts come together the whole is much, much greater than the sum of the parts.

Q: What are these rules?

A: We've seen that consistently—across functional roles, products, processes (assembly, equipment maintenance and repair, materials logistics, training, system redesign, administration, etc.), and hierarchical levels (from shop floor to plant manager and above) that in TPS managed organizations the design of nearly all work activities, connections among people, and pathways of connected activities over which products, services, and information take form are specified-in-their-design, tested-with-their-every-use, and improved close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem .

Q: That sounds pretty rigorous.

A: It is, but consider what the Toyota people are attempting to accomplish. They are saying before you (or you all) do work, make clear what you expect to happen (by specifying the design), each time you do work, see that what you expected has actually occurred (by testing with each use), and when there is a difference between what had actually happened and what was predicted, solve problems while the information is still fresh.

Q: That reminds me of what my high school lab science teacher required.

A: Exactly! This is a system designed for broad based, frequent, rapid, low-cost learning. The "Rules" imply a belief that we may not get the right solution (to work system design) on the first try, but that if we design everything we do as a bona fide experiment, we can more rapidly converge, iteratively, and at lower cost, on the right answer, and, in the process, learn a heck of lot more about the system we are operating.

Q: You say in your article that the Toyota system involves a rigorous and methodical problem-solving approach that is made part of everyone's work and is done under the guidance of a teacher. How difficult would it be for companies to develop their own program based on the Toyota model?

A: Your question cuts right to a critical issue. We discussed earlier the basic problem that for complex systems, responsibility for design, testing, and improvement must be distributed broadly. We've observed that Toyota, its best suppliers, and other companies that have learned well from Toyota can confidently distribute a tremendous amount of responsibility to the people who actually do the work, from the most senior, expeirenced member of the organization to the most junior. This is accomplished because of the tremendous emphasis on teaching everyone how to be a skillful problem solver.

Q: How do they do this?

A: They do this by teaching people to solve problems by solving problems. For instance, in our paper we describe a team at a Toyota supplier, Aisin. The team members, when they were first hired, were inexperienced with at best an average high school education. In the first phase of their employment, the hurdle was merely learning how to do the routine work for which they were responsible. Soon thereafter though, they learned how to immediately identify problems that occurred as they did their work. Then they learned how to do sophisticated root-cause analysis to find the underlying conditions that created the symptoms that they had experienced. Then they regularly practiced developing counter-measures—changes in work, tool, product, or process design—that would remove the underlying root causes.

Q: Sounds impressive.

A: Yes, but frustrating. They complained that when they started, they were "blissful in their ignorance." But after this sustained development, they could now see problems, root down to their probable cause, design solutions, but the team members couldn't actually implement these solutions. Therefore, as a final round, the team members received training in various technical crafts—one became a licensed electrician, another a machinist, another learned some carpentry skills.

Q: Was this unique?

A: Absolutely not. We saw the similar approach repeated elsewhere. At Taiheiyo, another supplier, team members made sophisticated improvements in robotic welding equipment that reduced cost, increased quality, and won recognition with an award from the Ministry of Environment. At NHK (Nippon Spring) another team conducted a series of experiments that increased quality, productivity, and efficiency in a seat production line.

Q: What is the role of the manager in this process?

A: Your question about the role of the manager gets right to the heart of the difficulty of managing this way. For many people, it requires a profound shift in mind-set in terms of how the manager envisions his or her role. For the team at Aisin to become so skilled as problem solvers, they had to be led through their training by a capable team leader and group leader. The team leader and group leader were capable of teaching these skills in a directed, learn-by-doing fashion, because they too were consistently trained in a similar fashion by their immediate senior. We found that in the best TPS-managed plants, there was a pathway of learning and teaching that cascaded from the most senior levels to the most junior. In effect, the needs of people directly touching the work determined the assistance, problem solving, and training activities of those more senior. This is a sharp contrast, in fact a near inversion, in terms of who works for whom when compared with the more traditional, centralized command and control system characterized by a downward diffusion of work orders and an upward reporting of work status.

Q: And if you are hiring a manager to help run this system, what are the attributes of the ideal candidate?

A: We observed that the best managers in these TPS managed organizations, and the managers in organizations that seem to adopt the Rules-in-Use approach most rapidly are humble but also self-confident enough to be great learners and terrific teachers. Furthermore, they are willing to subscribe to a consistent set of values.

Q: How do you mean?

A: Again, it is what is implied in the guideline of specifying every design, testing with every use, and improving close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem. If we do this consistently, we are saying through our action that when people come to work, they are entitled to expect that they will succeed in doing something of value for another person. If they don't succeed, they are entitled to know immediately that they have not. And when they have not succeeded, they have the right to expect that they will be involved in creating a solution that makes success more likely on the next try. People who cannot subscribe to these ideas—neither in their words nor in their actions—are not likely to manage effectively in this system.

Q: That sounds somewhat high-minded and esoteric.

A: I agree with you that it strikes the ear as sounding high principled but perhaps not practical. However, I'm fundamentally an empiricist, so I have to go back to what we have observed. In organizations in which managers really live by these Rules, either in the Toyota system or at sites that have successfully transformed themselves, there is a palpable, positive difference in the attitude of people that is coupled with exceptional performance along critical business measures such as quality, cost, safety, and cycle time.

Q: Have any other research projects evolved from your findings?

A: We titled the results of our initial research "Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System." Kent and I are reasonably confident that the Rules-in-Use about which we have written are a successful decoding. Now, we are trying to "replicate the DNA" at a variety of sites. We want to know where and when these Rules create great value, and where they do, how they can be implemented most effectively.

Since we are empiricists, we are conducting experiments through our field research. We are part of a fairly ambitious effort at Alcoa to develop and deploy the Alcoa Business System, ABS. This is a fusion of Alcoa's long standing value system, which has helped make Alcoa the safest employer in the country, with the Rules in Use. That effort has been going on for a number of years, first with the enthusiastic support of Alcoa's former CEO, Paul O'Neill, now Secretary of the Treasury (not your typical retirement, eh?) and now with the backing of Alain Belda, the company's current head. There have been some really inspirational early results in places as disparate as Hernando, Mississippi and Poces de Caldas, Brazil and with processes as disparate as smelting, extrusion, die design, and finance.

We also started creating pilot sites in the health care industry. We started our work with a "learning unit" at Deaconess-Glover Hospital in Needham, not far from campus. We've got a series of case studies that captures some of the learnings from that effort. More recently, we've established pilot sites at Presbyterian and South Side Hospitals, both part of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. This work is part of a larger, comprehensive effort being made under the auspices of the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative, with broad community support, with cooperation from the Centers for Disease Control, and with backing from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Also, we've been testing these ideas with our students: Kent in the first year Technology and Operations Management class for which he is course head, me in a second year elective called Running and Growing the Small Company, and both of us in an Executive Education course in which we participate called Building Competitive Advantage Through Operations.

- 25 Jun 2024

- Research & Ideas

Rapport: The Hidden Advantage That Women Managers Bring to Teams

- 11 Jun 2024

- In Practice

The Harvard Business School Faculty Summer Reader 2024

How transparency sped innovation in a $13 billion wireless sector.

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- 27 Jun 2016

These Management Practices, Like Certain Technologies, Boost Company Performance

- Infrastructure

- Organizational Design

- Competency and Skills

- Manufacturing

- Transportation

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

- Scroll to top

- Request a demo

How Toyota uses Beaconforce to add a human touch to productivity

4 ottobre, 2022, introduction the solution the advantages results.

Toyota is one of the world’s largest and best- known automobile manufacturing businesses employing over 360,000 people. The company’s vision is to “lead the way to the future of mobility by developing the safest and most responsible ways of transporting people”. Toyota’s two main values include respect for people and continuous improvement. While many people know about Toyota’s original manufacturing philosophy called the Toyota Production System (TPS) which aims to eliminate waste and achieve the best possible efficiency - widely known as a “lean” or “just-in-time” system, only a few know the principle of TPS is the concept of jidoka - a Japanese term that can be translated as “ automation with a human touch ”. The aim of jidoka is to spot problems or faults in the production process and take prompt action to prevent problems from happening again while maintaining quality and productivity. Toyota had long known the value of the human touch and how respect for their people empowered continuous improvement. Toyota Motor Italia offered employees a survey relating to their involvement but, with such a large workforce this data could only be collected every two years. Toyota realized that if they could find a way to frequently check on their people’s engagement and motivation the company would be able to identify areas of improvement, define action plans and measure their impact in a more agile way . Aware of the partial effectiveness of the two-year employee engagement survey, Toyota Motor Italia realized the need to implement a tool that would help them support employees on a daily basis. The company commissioned Gartner to recommend tools that would: Be easily integrated into their people’s daily workflows Collect data in real-time Involve line managers in a more effective way Facilitate meaningful and productive conversations Provide HR with clear metrics Support the Toyota values of respect for people and continuous improvement

After a thorough analysis of available technologies, Toyota Motor Italia selected Beaconforce as the system most aligned with the principles of TPS. With these principles in mind, Beaconforce implemented methods taking into account several factors. Firstly, by spearheading the redesign of Toyota’s HR reports with a strong focus on the fact that Toyota has always been committed to putting their people’s needs first . By leveraging the Beaconforce Stress Diagram to identify the teams and employees under high stress . And, in order to help employees in the stress zone, HR created a clear escalation process that involves managers first, and top management after if the situation doesn’t improve. And finally, through Beaconforce, the monitoring of organizational and team engagement in a more structured way, adding objective data to performance reviews or other qualitative approaches . On a quarterly basis, among all the Beaconforce key indicators, HR identifies the main areas of improvement and the metrics that require more attention and then presents an action plan to top management.

“After doing an analysis with Gartner of the different options out there, we couldn’t find any other technology that allowed us to manage, monitor, and cultivate intrinsic motivation like Beaconforce allowed us to do in real-time.”

Giuseppe de Nichilo

HR, Corporate Planning & Facilities General Manager at Toyota

Changing what they measure, directed leaders’ attention to the real drivers of sustainable success . With the identification of teams and employees that were under stress, Toyota’s HR team was able to help employees at risk of burnout. Some of these action plans have included: Providing dedicated training to the employees after identifying a gap in their knowledge or skills. Guiding managers on reassessments of work allocation within teams. Personalized coaching sessions when the issue is not directly related to the day-to-day activity.

The results of implementing beaconforce exceeded toyota motor italia’s expectations. within the first few months, results included: an adoption rate of 98% (greater acceptance than any previous technology). employee stress was reduced by 32% turnover rate reduction by 65% (from 2.84% to 0.95%, data relating to the period: february 2019 - may 2022). greater sensitivity in conversations between managers and workers real-time reporting of employee engagement and motivation agile business improvement . in many ways, beconforce is the embodiment of “automation with a human touch" but instead of looking for problems or faults in the production process, beaconforce uses technology such as artificial intelligence (ai) to identify sentiments within the workforce to instigate conversations with managers that can prevent stress, burnout or other problems occurring., see the files we have prepared for you, success stories.

How Tirreno Power Lowers Turnover & Retains Top Talent

How Beaconforce helped Falck Renewables in the energy sector’s war of talent

Next project.

Resilience Tested: Toyota Crisis Management Case Study

Crisis management is organization’s ability to navigate through challenging times.

The renowned Japanese automaker Toyota faced such challenge which shook the automotive industry and put a dent in the previously pristine reputation of the brand.

The Toyota crisis, characterized by sudden acceleration issues in some of its vehicles, serves as a compelling case study for examining the importance of effective crisis management.

Toyota crisis management case study gives background of the crisis, analyze Toyota’s initial response, explore their crisis management strategy, evaluate its effectiveness, and draw valuable lessons from this pivotal event.

By understanding how Toyota tackled this crisis, we can glean insights that will help organizations better prepare for and respond to similar challenges in the future.

Let’s start reading

Brief history of Toyota as a company

Toyota, one of the world’s largest automobile manufacturers, has a rich history that spans over eight decades. The company was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda in 1937 as a spinoff of his father’s textile machinery business.

Initially, Toyota focused on producing automatic looms, but Kiichiro had a vision to expand into the automotive industry. Inspired by a trip to the United States and Europe, he saw the potential for automobiles to transform society and decided to steer the company in that direction.

In 1936, Toyota built its first prototype car, the A1, and in 1937, they officially established the Toyota Motor Corporation. The company faced numerous challenges in its early years, including the disruption caused by World War II, which halted production.

However, Toyota persisted and resumed operations after the war, embarking on a journey that would eventually lead to global recognition.

Toyota’s breakthrough came in the 1960s with the introduction of the compact and affordable Toyota Corolla, which quickly gained popularity worldwide. This success laid the foundation for Toyota’s reputation for producing reliable, fuel-efficient, and high-quality vehicles.

Throughout the following decades, Toyota expanded its product lineup, launching models like the Camry, Prius (the world’s first mass-produced hybrid car), and the Land Cruiser, among others.

Toyota’s commitment to continuous improvement and efficiency led to the development and implementation of the Toyota Production System (TPS), often referred to as “lean manufacturing.” TPS revolutionized the automotive industry by minimizing waste, improving productivity, and enhancing quality.

Over the years, Toyota successfully implemented many change initiatives.

By the turn of the 21st century, Toyota had firmly established itself as a global automotive powerhouse, consistently ranking among the top automakers in terms of sales volume.

However, the company would soon face a significant challenge in the form of the sudden acceleration crisis, which tested Toyota’s crisis management capabilities and had far-reaching implications for the brand.

Description of the sudden acceleration crisis

The sudden acceleration crisis was a pivotal event in Toyota’s history, which unfolded in the late 2000s and early 2010s. It involved a series of incidents where Toyota vehicles experienced unintended acceleration, leading to accidents, injuries, and even fatalities. Reports emerged of vehicles accelerating uncontrollably, despite drivers attempting to apply the brakes or shift into neutral.

The crisis gained significant media attention and scrutiny , as it posed serious safety concerns for Toyota customers and raised questions about the company’s manufacturing processes and quality control. The issue affected a wide range of Toyota models, including popular ones such as the Camry, Corolla, and Prius.

Investigations revealed that the unintended acceleration was attributed to various factors. One prominent cause was a design flaw in the accelerator pedal assembly, where the pedals could become trapped or stuck in a partially depressed position. Additionally, electronic throttle control systems were also identified as potential contributors to the issue.

The sudden acceleration crisis had severe consequences for Toyota. It tarnished the company’s reputation for reliability and safety, and public trust in the brand was significantly eroded. Toyota faced a wave of lawsuits, regulatory investigations, and recalls, as it scrambled to address the issue and restore consumer confidence.

The crisis prompted Toyota to launch one of the largest recalls in automotive history, affecting millions of vehicles worldwide. The company took steps to redesign and replace the faulty accelerator pedals and improve the electronic throttle control systems to prevent future incidents. Toyota also faced criticism for its initial response, with accusations of a lack of transparency and timely communication with the public.

The sudden acceleration crisis served as a wake-up call for Toyota, highlighting the importance of effective crisis management and the need for proactive measures to address safety concerns promptly.

Toyota crisis management case study helps us to understand how company’s respond to this crisis and set a precedent for handling future challenges in the years to come.

Timeline of events leading up to the crisis

To understand the timeline of events leading up to the sudden acceleration crisis at Toyota, let’s explore the key milestones:

- Early 2000s: Reports of unintended acceleration incidents begin to surface, with some drivers claiming their Toyota vehicles experienced sudden and uncontrolled acceleration. These incidents, although relatively isolated, raised concerns among consumers.

- August 2009: A tragic incident occurs in California when a Lexus ES 350, a Toyota brand, accelerates uncontrollably, resulting in a high-speed crash that claims the lives of four people. The incident receives significant media attention, highlighting the potential dangers of unintended acceleration.