- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

7 Ways to Improve Your Ethical Decision-Making

Effective decision-making is the cornerstone of any thriving business. According to a survey of 760 companies cited in the Harvard Business Review , decision effectiveness and financial results correlated at a 95 percent confidence level across countries, industries, and organization sizes.

Yet, making ethical decisions can be difficult in the workplace and often requires dealing with ambiguous situations.

If you want to become a more effective leader , here’s an overview of why ethical decision-making is important in business and how to be better at it.

Access your free e-book today.

The Importance of Ethical Decision-Making

Any management position involves decision-making .

“Even with formal systems in place, managers have a great deal of discretion in making decisions that affect employees,” says Harvard Business School Professor Nien-hê Hsieh in the online course Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability . “This is because many of the activities companies need to carry out are too complex to specify in advance.”

This is where ethical decision-making comes in. As a leader, your decisions influence your company’s culture, employees’ motivation and productivity, and business processes’ effectiveness.

It also impacts your organization’s reputation—in terms of how customers, partners, investors, and prospective employees perceive it—and long-term success.

With such a large portion of your company’s performance relying on your guidance, here are seven ways to improve your ethical decision-making.

1. Gain Clarity Around Personal Commitments

You may be familiar with the saying, “Know thyself.” The first step to including ethics in your decision-making process is defining your personal commitments.

To gain clarity around those, Hsieh recommends asking:

- What’s core to my identity? How do I perceive myself?

- What lines or boundaries will I not cross?

- What kind of life do I want to live?

- What type of leader do I want to be?

Once you better understand your core beliefs, values, and ideals, it’s easier to commit to ethical guidelines in the workplace. If you get stuck when making challenging decisions, revisit those questions for guidance.

2. Overcome Biases

A bias is a systematic, often unconscious inclination toward a belief, opinion, perspective, or decision. It influences how you perceive and interpret information, make judgments, and behave.

Bias is often based on:

- Personal experience

- Cultural background

- Social conditioning

- Individual preference

It exists in the workplace as well.

“Most of the time, people try to act fairly, but personal beliefs or attitudes—both conscious and subconscious—affect our ability to do so,” Hsieh says in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability .

There are two types of bias:

- Explicit: A bias you’re aware of, such as ageism.

- Implicit: A bias that operates outside your awareness, such as cultural conditioning.

Whether explicit or implicit, you must overcome bias to make ethical, fair decisions.

Related: How to Overcome Stereotypes in Your Organization

3. Reflect on Past Decisions

The next step is reflecting on previous decisions.

“By understanding different kinds of bias and how they can show themselves in the workplace, we can reflect on past decisions, experiences, and emotions to help identify problem areas,” Hsieh says in the course.

Reflect on your decisions’ processes and the outcomes. Were they favorable? What would you do differently? Did bias affect them?

Through analyzing prior experiences, you can learn lessons that help guide your ethical decision-making.

4. Be Compassionate

Decisions requiring an ethical lens are often difficult, such as terminating an employee.

“Termination decisions are some of the hardest that managers will ever have to make,” Hsieh says in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability . “These decisions affect real people with whom we often work every day and who are likely to depend on their job for their livelihood.”

Such decisions require a compassionate approach. Try imagining yourself in the other person’s shoes, and think about what you would want to hear. Doing so allows you to approach decision-making with more empathy.

5. Focus on Fairness

Being “fair” in the workplace is often ambiguous, but it’s vital to ethical decision-making.

“Fairness is not only an ethical response to power asymmetries in the work environment,” Hsieh says in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability . “Fairness–and having a successful organizational culture–can benefit the organization economically and legally as well.”

It’s particularly important to consider fairness in the context of your employees. According to Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability , operationalizing fairness in employment relationships requires:

- Legitimate expectations: Expectations stemming from a promise or regular practice that employees can anticipate and rely on.

- Procedural fairness: Concern with whether decisions are made and carried out impartially, consistently, and transparently.

- Distributive fairness: The fair allocation of opportunities, benefits, and burdens based on employees’ efforts or contributions.

Keeping these aspects of fairness in mind can be the difference between a harmonious team and an employment lawsuit. When in doubt, ask yourself: “If I or someone I loved was at the receiving end of this decision, what would I consider ‘fair’?”

6. Take an Individualized Approach

Not every employee is the same. Your relationships with team members, managers, and organizational leaders differ based on factors like context and personality types.

“Given the personal nature of employment relationships, your judgment and actions in these areas will often require adjustment according to each specific situation,” Hsieh explains in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability .

One way to achieve this is by tailoring your decision-making based on employees’ values and beliefs. For example, if a colleague expresses concerns about a project’s environmental impact, explore eco-friendly approaches that align with their values.

Another way you can customize your ethical decision-making is by accommodating employees’ cultural differences. Doing so can foster a more inclusive work environment and boost your team’s performance .

7. Accept Feedback

Ethical decision-making is susceptible to gray areas and often met with dissent, so it’s critical to be approachable and open to feedback .

The benefits of receiving feedback include:

- Learning from mistakes.

- Having more opportunities to exhibit compassion, fairness, and transparency.

- Identifying blind spots you weren’t aware of.

- Bringing your team into the decision-making process.

While such conversations can be uncomfortable, don’t avoid them. Accepting feedback will not only make you a more effective leader but also help your employees gain a voice in the workplace.

Ethical Decision-Making Is a Continuous Learning Process

Ethical decision-making doesn’t come with right or wrong answers—it’s a continuous learning process.

“There often is no right answer, only imperfect solutions to difficult problems,” Hsieh says. “But even without a single ‘right’ answer, making thoughtful, ethical decisions can make a major difference in the lives of your employees and colleagues.”

By taking an online course, such as Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability , you can develop the frameworks and tools to make effective decisions that benefit all aspects of your business.

Ready to improve your ethical decision-making? Enroll in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability —one of our online leadership and management courses —and download our free e-book on how to become a more effective leader.

About the Author

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Seven Ethical Stances to Consider

After studying the concepts of better thinking, the basics of ethical interpretation, and the philosophical conception of objective and subjective thinking, we must focus on various philosophical and ethical approaches that individuals employ daily. For simplicity’s sake, this chapter has been broken into seven areas of exploration. This compilation is designed to introduce these significant ethical decision-making approaches to understand better how each of us might decide critical ethical issues and so that we can better understand how people and organizations have argued moral theory historically. This study is also essential for us to become more familiar with how people might best make ethical decisions, thus leading all of us toward continuous improvement over time.

The categories we will explore are:

Natural Law

Individuals and institutions use more than one approach to decision-making. They use a combination or hybrid of theories because moral stances often overlap and dictate differing approaches or perspectives and their use. Because this is a reality, we must be diligent when studying the ethical theory of these seven concrete categories. We must be mindful that these classifications are theoretically artificial and must be applied in “real-life” situations to develop further meaning and understanding. By studying these categories, we become more aware of the presumptions and assumptions of those involved in the decision-making process. Hopefully, we will be better equipped to evaluate moral processes and outcomes.

Consequentialist Thinking

- The teleological approach

- The issue of Utility

- Act and Rule Utility

- Jeremy Bentham and JS Mill

The first general category of ethical thinking is “consequentialist” thinking. Individuals using this stance believe that the right action in any circumstance or dilemma produces results the result one, either individually or by group consensus, believes is valuable.

Consequentialists hold that ethical decisions can only be accurately judged on the merit of the result or outcome of the decision. As a result, such philosophical theories as pragmatism and utilitarianism are often referred to as teleological theories. The term teleology comes from the Greek root “telos, ” loosely translated as the end, completion, purpose, or goal of any thing or activity.

An excellent example can be found in Aristotle’s stance on ethics. Aristotle maintains a form of teleology by arguing the result of individual happiness is the essential element when deciding the ethical nature of a subject. Using his idea of the balance point of life as the basis to determine the level of contentment, Aristotle reasons that one’s knowledge of the outcome is the most crucial element to consider when determining the moral validity of a situation.

Consequentiality theory may also be interpreted in the framework of utilitarianism. This moral stance argues that the most moral results in “the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number.” In both examples, Aristotle’s definition from the fourth century BC and the concept of utility basically center on England’s seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, offering a moral problem-solving approach central to the success and practical use of the theories. This practicality or success can be understood by formulating other hybrid moral theories. Philosophers such as Cornman and Frankena use consequentiality in their moral approaches, creating hybrids where moral outcomes are understood in the context of many possible outcomes. In this sense, such thinkers see morality in terms of contextualism or the idea that situations, circumstances, and personalization play a large part in proper moral decision-making.

- Order of the world

- Natural process

- Thomas Aquinas

The second approach to moral decision-making is natural law. In this stance, we find arguments that base the morally correct decision on the ability to explore the natural world around us through proper reason. Using our natural logic or reasoning ability, we can deduce proper moral assessment; thus, correct morality or decision-making should be based on natural processes or connected with nature cycles or natural laws around us.

At the core of this belief is the assertion that principles of human conduct can be derived from a proper understanding of humanity in the context of the universe as a rational whole. The proper ethical choice can be found in contemplating individuals’ acknowledgment and acceptance of their place with each other and nature.

The prime example of this ethical approach is the Stoic movement of the late Hellenistic Greek and Roman Republic era. According to the Stoics, one who wishes to live a moral life must understand that life is short and we are limited in our control of many factors. Therefore, we must accept nature’s control by acknowledging that we are left with nothing in our lives except the ability to control our actions in response to the powers of nature. Through our understanding of these factors, we should try to live humble life devoted to moral principles found in an organic approach to living that acknowledges this power.

- Deontological Thinking

- Categorical Imperative

- The Principle of Ends

- Immanuel Kant

The third ethical theory is the conception of duty. The central belief is that morality comes from doing what we understand to be the practical content and application of the convictions we acquire from the world around us and the people in it. This approach, best exemplified by the work of Immanuel Kant, is based on the philosophical conception of deontology.

Deontology refers to the belief that morality is only correctly understood in the context of moral necessity or obligation. Unlike consequentialist theory, deontological thinkers believe that truly right decisions are not based on practical results but rather the moral obligation inherent in the notion of duty found in the natural understanding and right employment of the concept of reason.

In Kant’s nineteenth-century theory, he points to two specific components that are the basis of duty-based ethical approaches. Individuals often refer to the categorical imperative or a universal moral principle that can be upheld regardless of the situation and the principle of ends. The categorical imperative or universal principle argues that ethically the right decision must be based on the belief that the process of carrying out proper moral decision-making is more important or just as necessary as the proper, reasoned end. Individuals who approach moral problem-solving from this perspective base their moral decision-making on their obligation to an absolutistic statement found in the base conception of this obligation to principles. Look at the following link to analyze Kant’s central portion of this theory.

- History of Rights in the Western World

- Preservation of Rights

- The Golden Rule

This fourth moral category relies on the belief that morality is shaped by one’s determination and assessment of human rights. This stance or moral decision-making process emphasizes justified expectations about the benefits to other people or society and what should be at the basis of that expectation of thought and behavior. These expectations are often understood as morally inherent provisions.

This view illustrates that we are entitled to rights provided we act towards others similarly, thus ensuring corresponding rights for them. Founded within the English tradition, dating to at least the thirteenth century, the expectation of how we treat others has become connected with a core of values that define life and the importance of each individual. Ethical evaluation is resolved by preserving agreed-upon respect for others through cooperation. Right and wrong are abstracted within the framework of expectations concerning benefits for individuals and people in groups.

The process to determine mutual rights is understood through consistent and careful exploration of mutually agreed-upon factors, the preservation of which is exchanging certain essential agreed-upon benefits to the advantage of those involved. In this sense, for the benefit of all, individuals base their moral conceptions on the practical application of daily life, the vision they have for how it should be carried out, and the preservation and betterment of that life through agreed-upon standards or the preservation of rights best understood in the conception of the idea of the golden rule, for example.

This ideology can also be understood in Thomas Hobbes’ ethical theory from the seventeenth century. He writes the harmful component of the golden rule is perhaps more productive. He argues that “not doing for others what you don’t want to be done to you” may be a more moral way to formulate or work towards a more moral society. Not getting in each other’s way by attempting to treat others as you would like to be treated. However, a demonstration of rights-based moral theory respects individual desires and rights. When doing this, people do not infringe on others’ interests or violate their rights and/or their ability to adhere to proper moral principles. This approach to morality relies upon understanding what is essential to most people involved in moral decision-making. It can often be seen in the formulation of laws that confirm the preservation of this conception of proper acquisition.

In thinking through the possible argument that ethical determination is founded in a discoverable and agreed-upon conception of what everyone is entitled to, listen to Robert Wright’s assessment of how compassion might be connected to the Golden Rule and our natural inclinations. Wright argues that our ethical evaluation might be understood within this hybrid of theories by integrating rights, instinct, and natural law.

- People We Respect

- Concepts We Prefer

- Simplistic and Natural

Virtue ethics is the fifth stance. In studying “ethos” or character, thinkers believe morality is directly connected to peoples’ understanding of what is conceptually “good.” The idea of a hierarchy of opinion, thought, or ideology becomes the focus of this perspective. Its conceptualization is correlated with what “behaviors or thoughts” we prefer individuals to possess and less about the reality of where people are in their moral stances.

Virtue ethics is best understood in the framework of the understanding of the terms “ideals or forms”, used by Greeks such as Plato and Aristotle. Their view maintains that humans have the innate inclination and ability to understand the concept of “betterment” in all avenues of life. As a result, we must seek to understand “true wisdom” to grasp the values or virtues we hold dear.

By doing this, morality becomes both the compass and motivating factor for our lives. It also becomes a guideline by encouraging us, through reason and knowledge, towards what are appropriate thoughts and behaviors while pushing us to realize that such ideas are not only subjective. Thus, these ideals function as factors for proper behavioral practice. In that process, we find meaning or progress in our lives. One way to do this is to focus on people that we respect. By analyzing their behavior and characteristics, we can internalize those values and make them part of our lives.

- The Importance of Belief

- Group or Individual Authority

- Revelation Based

- Conscience (Soul)

The sixth moral category highlights the concept of morality based on some form of authority, whether as a political, social, or cultural entity. Often referred to as “belief ethics”, this approach can also be understood as determined by a form of a supernatural or natural authority figure who has given humanity a preferred way or manner of living.

This approach conceptualizes morality as a series of beliefs, concepts, or dictums given to humans for survival. This belief often is directly connected with the understanding that morality can be closely linked to authority figures and to direct imperatives. Thus, many assert or argue that religion and/or religious beliefs may be directly tied to one’s understanding of morality or ethical belief. Therefore the issue is how one attains that moral understanding.

There are many plausible arguments, but I have narrowed it down to two that best explain this perspective.

- Morality, though steeped in some form of a moral command, is usually connected with a unique situation or understanding, allowing this information to be divulged. When this unique situation occurs, these ideas are often reason-based and/or virtue oriented and hold to conduct that enhances the well-being or “betterment” of those involved.

- The authority-based approach to ethical conceptualization often asserts that conscience, or an innate awareness within us, confirms the validity of this understanding. Thus, some authority-based interpretations argue that morality is known through the combination of directives and solid moral “feelings” or understanding coupled with a strong awareness of inner inclinations. “Inner awareness” leads or confirms to us that such natural or supernatural authorities dictate proper moral principles. In the end, authority becomes a basis for people to determine the right course of action in ethical decision-making, understanding that the human is part of that process but not the sole factor in formulating proper ethical standards and/or norms.

- Community Standards

- Kinship & Nepotism

- Reciprocity

The last area of exploration is instinct. This study comes from the belief that morality stems from our natural urges or natural/biological phenomena. This approach stresses the importance of understanding our instincts’ role in developing morality. Instinct can be defined as a form of natural control or guidance that influence our thinking and behavior. It is central to how we relate to others in a community.

Unlike the other theories presented, this stance argues that community standards or moral stances are based on our natural need to preserve ourselves or our species/gene pool. Therefore, morality is staked in self-preservation.

Individuals who defend this viewpoint believe they will naturally favor their kin or biological relations in moral decision-making. Therefore, their moral stances rely upon biological factors, and they dictate their priorities and moral beliefs. Additionally, this field of moral analysis asserts that our biological makeup or natural “being” influences us in two other ways. One, we innately work towards reciprocity or the moral belief that exchanging goods and/or aid is central to morality; and two, the basis of actual ethical decision-making, can be found in sharing “favors” so that individuals benefit.

The core of reciprocity is found in individual right versus wrong assessments and uniting those factors with the self-interest found in community cooperation. As a result, instinct morality seems to be motivated in many theories by the assumption that reality dictates moral choices and that community norms are simply a reflection of individual and natural rectifications that ultimately maximize individual survival. Listen to Jane Goodall to hear more about the argument of instinct-based morality as a plausible ethical decision-making outcome.

Franz De Waal has defended that animals can teach us much about moral behavior. Listen to his analysis of the morality of animal behavior that supports the ideology of instinct ethics.

Ultimately, instinct ethics focuses on believing humans have become too complicated in our ethical evaluation. We may rely too much on education, reason, and complex systems that have yielded unethical returns. By attempting to return to what is most natural, theorists’ arguments support the idea that we would be more moral if we focused on community, cooperation, and natural need.

Final Thoughts on Seven Approaches to Ethical Problem Solving

The approaches discussed in this chapter are plausible arguments for how morality is formulated and discuss what factors affect how people conceptualize decision-making. Leaders need to understand these approaches when they weigh difficult decisions or formulate business policies. What is perhaps just as important is that one takes these seven approaches and qualifies that knowledge with the understanding that these approaches are integrated into many ways. Though these categories are “neat” and “tidy” by definition, they also are explored in an academic setting. The reality of the human experience dictates that we understand these elements in the context of integration. A person who relies on instinct as the basis of moral decision-making in one instance might appeal to virtues or values in another. Beyond this, it is commonplace to see individuals appeal to both in the same circumstance, thus creating, as listed above, hybrid theories. A good example might be the understanding that authority-based ethical theory coincides with instinct and virtue, as individuals argue that God or some supernatural power created virtue, values, or instinct as an ethical gauge.

All appeal to both facets or are multi-layered in their approach to understanding the basics of moral theory and thus make the task of assessing these various approaches extremely difficult. Perhaps the place to start in the estimation of University of Alabama professor James Rachels is to acknowledge these various approaches and work to see their unique overlapping components and specific connections. Rachels offers two solid suggestions for dealing with moral basics that should help address these areas as one is confronted by their different stances.

- First, get as much factual knowledge as possible.

- Second, attempt to decrease subjective interpretations or human prejudice.

Taking these seven as the beginning of approaches, leaders can begin to understand how individuals approach moral decision-making more fully. Developing awareness of these categories and their potential hybrids allows us to more clearly, effectively, and carefully address potential problems.

References:

Cotton, J. (2016, April 06). Immanuel Kant. Retrieved from https://www.theschooloflife.com/thebookoflife/immanuel-kant/

Goodall, J. (2002, March). What separates us from chimpanzees? Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_goodall_on_what_separates_us_from_the_apes

Waal, F. D. (n.d.). Moral behavior in animals. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/frans_de_waal_do_animals_have_morals

Wright, R. (2009, October). The evolution of compassion. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/robert_wright_the_evolution_of_compassion

Chapter 4--Perspectives in Ethical Theory Copyright © 2018 by Christopher Brooks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thinking Ethically

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Ethics Resources

- Ethical Decision Making

Moral issues greet us each morning in the newspaper, confront us in the memos on our desks, nag us from our children's soccer fields, and bid us good night on the evening news. We are bombarded daily with questions about the justice of our foreign policy, the morality of medical technologies that can prolong our lives, the rights of the homeless, the fairness of our children's teachers to the diverse students in their classrooms.

Dealing with these moral issues is often perplexing. How, exactly, should we think through an ethical issue? What questions should we ask? What factors should we consider?

The first step in analyzing moral issues is obvious but not always easy: Get the facts. Some moral issues create controversies simply because we do not bother to check the facts. This first step, although obvious, is also among the most important and the most frequently overlooked.

But having the facts is not enough. Facts by themselves only tell us what is ; they do not tell us what ought to be. In addition to getting the facts, resolving an ethical issue also requires an appeal to values. Philosophers have developed five different approaches to values to deal with moral issues.

The Utilitarian Approach Utilitarianism was conceived in the 19th century by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill to help legislators determine which laws were morally best. Both Bentham and Mill suggested that ethical actions are those that provide the greatest balance of good over evil.

To analyze an issue using the utilitarian approach, we first identify the various courses of action available to us. Second, we ask who will be affected by each action and what benefits or harms will be derived from each. And third, we choose the action that will produce the greatest benefits and the least harm. The ethical action is the one that provides the greatest good for the greatest number.

The Rights Approach The second important approach to ethics has its roots in the philosophy of the 18th-century thinker Immanuel Kant and others like him, who focused on the individual's right to choose for herself or himself. According to these philosophers, what makes human beings different from mere things is that people have dignity based on their ability to choose freely what they will do with their lives, and they have a fundamental moral right to have these choices respected. People are not objects to be manipulated; it is a violation of human dignity to use people in ways they do not freely choose.

Of course, many different, but related, rights exist besides this basic one. These other rights (an incomplete list below) can be thought of as different aspects of the basic right to be treated as we choose.

The right to the truth: We have a right to be told the truth and to be informed about matters that significantly affect our choices.

The right of privacy: We have the right to do, believe, and say whatever we choose in our personal lives so long as we do not violate the rights of others.

The right not to be injured: We have the right not to be harmed or injured unless we freely and knowingly do something to deserve punishment or we freely and knowingly choose to risk such injuries.

The right to what is agreed: We have a right to what has been promised by those with whom we have freely entered into a contract or agreement.

In deciding whether an action is moral or immoral using this second approach, then, we must ask, Does the action respect the moral rights of everyone? Actions are wrong to the extent that they violate the rights of individuals; the more serious the violation, the more wrongful the action.

The Fairness or Justice Approach The fairness or justice approach to ethics has its roots in the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who said that "equals should be treated equally and unequals unequally." The basic moral question in this approach is: How fair is an action? Does it treat everyone in the same way, or does it show favoritism and discrimination?

Favoritism gives benefits to some people without a justifiable reason for singling them out; discrimination imposes burdens on people who are no different from those on whom burdens are not imposed. Both favoritism and discrimination are unjust and wrong.

The Common-Good Approach This approach to ethics assumes a society comprising individuals whose own good is inextricably linked to the good of the community. Community members are bound by the pursuit of common values and goals.

The common good is a notion that originated more than 2,000 years ago in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero. More recently, contemporary ethicist John Rawls defined the common good as "certain general conditions that are...equally to everyone's advantage."

In this approach, we focus on ensuring that the social policies, social systems, institutions, and environments on which we depend are beneficial to all. Examples of goods common to all include affordable health care, effective public safety, peace among nations, a just legal system, and an unpolluted environment.

Appeals to the common good urge us to view ourselves as members of the same community, reflecting on broad questions concerning the kind of society we want to become and how we are to achieve that society. While respecting and valuing the freedom of individuals to pursue their own goals, the common-good approach challenges us also to recognize and further those goals we share in common.

The Virtue Approach The virtue approach to ethics assumes that there are certain ideals toward which we should strive, which provide for the full development of our humanity. These ideals are discovered through thoughtful reflection on what kind of people we have the potential to become.

Virtues are attitudes or character traits that enable us to be and to act in ways that develop our highest potential. They enable us to pursue the ideals we have adopted. Honesty, courage, compassion, generosity, fidelity, integrity, fairness, self-control, and prudence are all examples of virtues.

Virtues are like habits; that is, once acquired, they become characteristic of a person. Moreover, a person who has developed virtues will be naturally disposed to act in ways consistent with moral principles. The virtuous person is the ethical person.

In dealing with an ethical problem using the virtue approach, we might ask, What kind of person should I be? What will promote the development of character within myself and my community?

Ethical Problem Solving These five approaches suggest that once we have ascertained the facts, we should ask ourselves five questions when trying to resolve a moral issue:

What benefits and what harms will each course of action produce, and which alternative will lead to the best overall consequences?

What moral rights do the affected parties have, and which course of action best respects those rights?

Which course of action treats everyone the same, except where there is a morally justifiable reason not to, and does not show favoritism or discrimination?

Which course of action advances the common good?

Which course of action develops moral virtues?

This method, of course, does not provide an automatic solution to moral problems. It is not meant to. The method is merely meant to help identify most of the important ethical considerations. In the end, we must deliberate on moral issues for ourselves, keeping a careful eye on both the facts and on the ethical considerations involved.

This article updates several previous pieces from Issues in Ethics by Manuel Velasquez - Dirksen Professor of Business Ethics at Santa Clara University and former Center director - and Claire Andre, associate Center director. "Thinking Ethically" is based on a framework developed by the authors in collaboration with Center Director Thomas Shanks, S.J., Presidential Professor of Ethics and the Common Good Michael J. Meyer, and others. The framework is used as the basis for many programs and presentations at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics.

5.3 Ethical Principles and Responsible Decision-Making

- What are major ethical principles that can be used by individuals and organizations?

Before turning to organizational and systems levels of ethics, we discuss classical ethical principles that are very relevant now and on which decisions can be and are made by individuals, organizations, and other stakeholders who choose principled, responsible ways of acting toward others. 17

Ethical principles are different from values in that the former are considered as rules that are more permanent, universal, and unchanging, whereas values are subjective, even personal, and can change with time. Principles help inform and influence values. Some of the principles presented here date back to Plato, Socrates, and even earlier to ancient religious groups. These principles can be, and are, used in combination; different principles are also used in different situations. 18 The principles that we will cover are utilitarianism, universalism, rights/legal, justice, virtue, common good, and ethical relativism approaches. As you read these, ask yourself which principles characterize and underlie your own values, beliefs, behaviors, and actions. It is helpful to ask and if not clear, perhaps identify the principles, you most often use now and those you aspire to use more, and why. Using one or more of these principles and ethical approaches intentionally can also help you examine choices and options before making a decision or solving an ethical dilemma. Becoming familiar with these principles, then, can help inform your moral decision process and help you observe the principles that a team, workgroup, or organization that you now participate in or will be joining may be using. Using creativity is also important when examining difficult moral decisions when sometimes it may seem that there are two “right” ways to act in a situation or perhaps no way seems morally right, which may also signal that not taking an action at that time may be needed, unless taking no action produces worse results.

Utilitarianism: A Consequentialist, “Ends Justifies Means” Approach

The utilitarianism principle basically holds that an action is morally right if it produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people. An action is morally right if the net benefits over costs are greatest for all affected compared with the net benefits of all other possible choices. This, as with all these principles and approaches, is broad in nature and seemingly rather abstract. At the same time, each one has a logic. When we present the specifics and facts of a situation, this and the other principles begin to make sense, although judgement is still required.

Some limitations of this principle suggest that it does not consider individuals, and there is no agreement on the definition of “good for all concerned.” In addition, it is difficult to measure “costs and benefits.” This is one of the most widely used principles by corporations, institutions, nations, and individuals, given the limitations that accompany it. Use of this principle generally applies when resources are scarce, there is a conflict in priorities, and no clear choice meets everyone’s needs—that is, a zero-sum decision is imminent

Universalism: A Duty-Based Approach

Universalism is a principle that considers the welfare and risks of all parties when considering policy decisions and outcomes. Also needs of individuals involved in a decision are identified as well as the choices they have and the information they need to protect their welfare. This principle involves taking human beings, their needs, and their values seriously. It is not only a method to make a decision; it is a way of incorporating a humane consideration of and for individuals and groups when deciding a course of action. As some have asked, “What is a human life worth?”

Cooper, Santora, and Sarros wrote, “Universalism is the outward expression of leadership character and is made manifest by respectfulness for others, fairness, cooperativeness, compassion, spiritual respect, and humility.” Corporate leaders in the “World’s Most Ethical Companies” strive to set a “tone at the top” to exemplify and embody universal principles in their business practices. 19 Howard Schultz, founder of Starbucks; cofounder Jim Sinegal at Costco; Sheryl Sandberg, chief operating officer of Facebook; and Ursula M. Burns, previous chairperson and CEO of Xerox have demonstrated setting effective ethical tones at the top of organizations.

Limitations here also show that using this principle may not always prove realistic or practical in all situations. In addition, using this principle can require sacrifice of human life—that is, giving one’s life to help or save others—which may seem contrary to the principle. The film The Post , based on fact, portrays how the daughter of the founder of the famed newspaper, the Washington Post , inherited the role of CEO and was forced to make a decision between publishing a whistle-blowers’ classified government documents of then top-level generals and officials or keep silent and protect the newspaper. The classified documents contained information proving that generals and other top-level government administrators were lying to the public about the actual status of the United States in the Vietnam War. Those documents revealed that there were doubts the war could be won while thousands of young Americans continued to die fighting. The dilemma for the Washington Post ’s then CEO centered on her having to choose between exposing the truth based on freedom of speech—which was the mission and foundation of the newspaper—or staying silent and suppressing the classified information. She chose, with the support of and pressure from her editorial staff, to release the classified documents to the public. The Supreme Court upheld her and her staff’s decision. A result was enflamed widespread public protests from American youth and others. President Johnson was pressured to resign, Secretary of State McNamara later apologized, and the war eventually ended with U.S. troops withdrawing. So, universalist ethical principles may present difficulties when used in complex situations, but such principles can also save lives, protect the integrity of a nation, and stop meaningless destruction.

Rights: A Moral and Legal Entitlement–Based Approach

This principle is grounded in both legal and moral rights . Legal rights are entitlements that are limited to a particular legal system and jurisdiction. In the United States, the Constitution and Declaration of Independence are the basis for citizens’ legal rights, for example, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and the right to freedom of speech. Moral (and human) rights, on the other hand, are universal and based on norms in every society, for example, the right not to be enslaved and the right to work.

To get a sense of individual rights in the workplace, log on to one of the “Best Companies to Work For” annual lists (http://fortune.com/best-companies/). Profiles of leaders and organizations’ policies, practices, perks, diversity, compensation, and other statistics regarding employee welfare and benefits can be reviewed. The “World’s Most Ethical Companies” also provides examples of workforce and workplace legal and moral rights. This principle, as with universalism, can always be used when individuals, groups, and nations are involved in decisions that may violate or harm such rights as life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and free speech.

Some limitations when using this principle are (1) it can be used to disguise and manipulate selfish and unjust political interests, (2) it is difficult to determine who deserves what when both parties are “right,” and (3) individuals can exaggerate certain entitlements at the expense of others. Still, the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791, was designed as and remains the foundation of, which is based on freedom and justice to protect the basic rights of all.

Justice: Procedures, Compensation, and Retribution

This principle has at least four major components that are based on the tenets that (1) all individuals should be treated equally; (2) justice is served when all persons have equal opportunities and advantages (through their positions and offices) to society’s opportunities and burdens; (3) fair decision practices, procedures, and agreements among parties should be practiced; and (4) punishment is served to someone who has inflicted harm on another, and compensation is given to those for a past harm or injustice committed against them.

A simple way of summarizing this principle when examining a moral dilemma is to ask of a proposed action or decision: (1) Is it fair? (2) Is it right? (3) Who gets hurt? (4) Who has to pay for the consequences? (5) Do I/we want to assume responsibility for the consequences? It is interesting to reflect on how many corporate disasters and crises might have been prevented had the leaders and those involved taken such questions seriously before proceeding with decisions. For example, the following precautionary actions might have prevented the disaster: updating the equipment and machinery that failed in the BP and the Exxon Valdez oil crises and investment banks and lending institutions following rules not to sell subprime mortgages that could not and would not be paid, actions that led to the near collapse of the global economy.

Limitations when using this principle involve the question of who decides who is right and wrong and who has been harmed in complex situations. This is especially the case when facts are not available and there is no objective external jurisdiction of the state or federal government. In addition, we are sometimes faced with the question, “Who has the moral authority to punish to pay compensation to whom?” Still, as with the other principles discussed here, justice stands as a necessary and invaluable building block of democracies and freedom.

Virtue Ethics: Character-Based Virtues

Virtue ethics is based on character traits such as being truthful, practical wisdom, happiness, flourishing, and well-being. It focuses on the type of person we ought to be, not on specific actions that should be taken. Grounded in good character, motives, and core values, the principle is best exemplified by those whose examples show the virtues to be emulated.

Basically, the possessor of good character is moral, acts morally, feels good, is happy, and flourishes. Altruism is also part of character-based virtue ethics. Practical wisdom, however, is often required to be virtuous.

This principle is related to universalism. Many leaders’ character and actions serve as examples of how character-based virtues work. For example, the famous Warren Buffett stands as an icon of good character who demonstrates trustworthy values and practical wisdom. Applying this principle is related to a “quick test” before acting or making a decision by asking, “What would my ‘best self’ do in this situation?” Others ask the question inserting someone they know or honor highly.

There are some limitations to this ethic. First, some individuals may disagree about who is virtuous in different situations and therefore would refuse to use that person’s character as a principle. Also, the issue arises, “Who defines virtuous , especially when a complex act or incident is involved that requires factual information and objective criteria to resolve?”

The Common Good

The common good is defined as “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members relatively thorough and ready access to their own fulfillment.” Decision makers must take into consideration the intent as well as the effects of their actions and decisions on the broader society and the common good of the many. 20

Identifying and basing decisions on the common good requires us to make goals and take actions that take others, beyond ourselves and our self-interest, into account. Applying the common good principle can also be asked by a simple question: “How will this decision or action affect the broader physical, cultural, and social environment in which I, my family, my friends, and others have to live, breathe, and thrive in now, next week, and beyond?”

A major limitation when using this principle is, “Who determines what the common good is in situations where two or more parties differ over whose interests are violated?” In individualistic and capitalist societies, it is difficult in many cases for individuals to give up their interests and tangible goods for what may not benefit them or may even deprive them.

Ethical Relativism: A Self-Interest Approach

Ethical relativism is really not a “principle” to be followed or modeled. It is an orientation that many use quite frequently. Ethical relativism holds that people set their own moral standards for judging their actions. Only the individual’s self-interest and values are relevant for judging his or her behavior. Moreover, moral standards, according to this principle, vary from one culture to another. “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.”

Obvious limitations of relativism include following one’s blind spots or self-interests that can interfere with facts and reality. Followers of this principle can become absolutists and “true believers”—many times believing and following their own ideology and beliefs. Countries and cultures that follow this orientation can result in dictatorships and absolutist regimes that practice different forms of slavery and abuse to large numbers of people. For example, South Africa’s all-white National Party and government after 1948 implemented and enforced a policy of apartheid that consisted of racial segregation. That policy lasted until the 1990s, when several parties negotiated its demise—with the help of Nelson Mandela ( www.history.com/topics/apartheid ). Until that time, international firms doing business in South Africa were expected to abide by the apartheid policy and its underlying values. Many companies in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere were pressured in the 1980s and before by public interest groups whether or not to continue doing business or leave South Africa.

At the individual level, then, principles and values offer a source of stability and self-control while also affecting job satisfaction and performance. At the organizational level, principled and values-based leadership influences cultures that inspire and motivate ethical behavior and performance. The following section discusses how ethical leadership at the top and throughout organizations affects ethical actions and behaviors. 21

Concept Check

- What are some ethical guidelines individuals and organizations can use to make ethical choices?

- Can being aware of the actual values you use to guide your actions make a difference in your choices?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: David S. Bright, Anastasia H. Cortes

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Management

- Publication date: Mar 20, 2019

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/5-3-ethical-principles-and-responsible-decision-making

© Jan 9, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Training & Certification

- Knowledge Center

- ECI Research

- Business Integrity Library

- Career Center

- The PLUS Ethical Decision Making Model

Seven Steps to Ethical Decision Making – Step 1: Define the problem (consult PLUS filters ) – Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support – Step 3: Identify alternatives – Step 4: Evaluate the alternatives (consult PLUS filters ) – Step 5: Make the decision – Step 6: Implement the decision – Step 7: Evaluate the decision (consult PLUS filters )

Introduction Organizations struggle to develop a simple set of guidelines that makes it easier for individual employees, regardless of position or level, to be confident that his/her decisions meet all of the competing standards for effective and ethical decision-making used by the organization. Such a model must take into account two realities:

- Every employee is called upon to make decisions in the normal course of doing his/her job. Organizations cannot function effectively if employees are not empowered to make decisions consistent with their positions and responsibilities.

- For the decision maker to be confident in the decision’s soundness, every decision should be tested against the organization’s policies and values, applicable laws and regulations as well as the individual employee’s definition of what is right, fair, good and acceptable.

The decision making process described below has been carefully constructed to be:

- Fundamentally sound based on current theories and understandings of both decision-making processes and ethics.

- Simple and straightforward enough to be easily integrated into every employee’s thought processes.

- Descriptive (detailing how ethical decision are made naturally) rather than prescriptive (defining unnatural ways of making choices).

Why do organizations need ethical decision making? See our special edition case study, #RespectAtWork, to find out.

First, explore the difference between what you expect and/or desire and the current reality. By defining the problem in terms of outcomes, you can clearly state the problem.

Consider this example: Tenants at an older office building are complaining that their employees are getting angry and frustrated because there is always a long delay getting an elevator to the lobby at rush hour. Many possible solutions exist, and all are predicated on a particular understanding the problem:

- Flexible hours – so all the tenants’ employees are not at the elevators at the same time.

- Faster elevators – so each elevator can carry more people in a given time period.

- Bigger elevators – so each elevator can carry more people per trip.

- Elevator banks – so each elevator only stops on certain floors, increasing efficiency.

- Better elevator controls – so each elevator is used more efficiently.

- More elevators – so that overall carrying capacity can be increased.

- Improved elevator maintenance – so each elevator is more efficient.

- Encourage employees to use the stairs – so fewer people use the elevators.

The real-life decision makers defined the problem as “people complaining about having to wait.” Their solution was to make the wait less frustrating by piping music into the elevator lobbies. The complaints stopped. There is no way that the eventual solution could have been reached if, for example, the problem had been defined as “too few elevators.”

How you define the problem determines where you go to look for alternatives/solutions– so define the problem carefully.

Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support

Once the problem is defined, it is critical to search out resources that may be of assistance in making the decision. Resources can include people (i.e., a mentor, coworkers, external colleagues, or friends and family) as well professional guidelines and organizational policies and codes. Such resources are critical for determining parameters, generating solutions, clarifying priorities and providing support, both while implementing the solution and dealing with the repercussions of the solution.

Step 3: Identify available alternative solutions to the problem The key to this step is to not limit yourself to obvious alternatives or merely what has worked in the past. Be open to new and better alternatives. Consider as many as solutions as possible — five or more in most cases, three at the barest minimum. This gets away from the trap of seeing “both sides of the situation” and limiting one’s alternatives to two opposing choices (i.e., either this or that).

Step 4: Evaluate the identified alternatives As you evaluate each alternative, identify the likely positive and negative consequence of each. It is unusual to find one alternative that would completely resolve the problem and is significantly better than all others. As you consider positive and negative consequences, you must be careful to differentiate between what you know for a fact and what you believe might be the case. Consulting resources, including written guidelines and standards, can help you ascertain which consequences are of greater (and lesser) import.

You should think through not just what results each alternative could yield, but the likelihood it is that such impact will occur. You will only have all the facts in simple cases. It is reasonable and usually even necessary to supplement the facts you have with realistic assumptions and informed beliefs. Nonetheless, keep in mind that the more the evaluation is fact-based, the more confident you can be that the expected outcome will occur. Knowing the ratio of fact-based evaluation versus non-fact-based evaluation allows you to gauge how confident you can be in the proposed impact of each alternative.

Step 5: Make the decision When acting alone, this is the natural next step after selecting the best alternative. When you are working in a team environment, this is where a proposal is made to the team, complete with a clear definition of the problem, a clear list of the alternatives that were considered and a clear rationale for the proposed solution.

Step 6: Implement the decision While this might seem obvious, it is necessary to make the point that deciding on the best alternative is not the same as doing something. The action itself is the first real, tangible step in changing the situation. It is not enough to think about it or talk about it or even decide to do it. A decision only counts when it is implemented. As Lou Gerstner (former CEO of IBM) said, “There are no more prizes for predicting rain. There are only prizes for building arks.”

Step 7: Evaluate the decision Every decision is intended to fix a problem. The final test of any decision is whether or not the problem was fixed. Did it go away? Did it change appreciably? Is it better now, or worse, or the same? What new problems did the solution create?

Ethics Filters

The ethical component of the decision making process takes the form of a set of “filters.” Their purpose is to surface the ethics considerations and implications of the decision at hand. When decisions are classified as being “business” decisions (rather than “ethics” issues), values can quickly be left out of consideration and ethical lapses can occur.

At key steps in the process, you should stop and work through these filters, ensuring that the ethics issues imbedded in the decision are given consideration.

We group the considerations into the mnemonic PLUS.

- P = Policies Is it consistent with my organization’s policies, procedures and guidelines?

- L = Legal Is it acceptable under the applicable laws and regulations?

- U = Universal Does it conform to the universal principles/values my organization has adopted?

- S = Self Does it satisfy my personal definition of right, good and fair?

The PLUS filters work as an integral part of steps 1, 4 and 7 of the decision-making process. The decision maker applies the four PLUS filters to determine if the ethical component(s) of the decision are being surfaced/addressed/satisfied.

- Does the existing situation violate any of the PLUS considerations?

- Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support

- Step 3: Identify available alternative solutions to the problem

- Will the alternative I am considering resolve the PLUS violations?

- Will the alternative being considered create any new PLUS considerations?

- Are the ethical trade-offs acceptable?

- Step 5: Make the decision

- Step 6: Implement the decision

- Does the resultant situation resolve the earlier PLUS considerations?

- Are there any new PLUS considerations to be addressed?

The PLUS filters do not guarantee an ethically-sound decision. They merely ensure that the ethics components of the situation will be surfaced so that they might be considered.

How Organizations Can Support Ethical Decision-Making Organizations empower employees with the knowledge and tools they need to make ethical decisions by

- Intentionally and regularly communicating to all employees:

- Organizational policies and procedures as they apply to the common workplace ethics issues.

- Applicable laws and regulations.

- Agreed-upon set of “universal” values (i.e., Empathy, Patience, Integrity, Courage [EPIC]).

- Providing a formal mechanism (i.e., a code and a helpline, giving employees access to a definitive interpretation of the policies, laws and universal values when they need additional guidance before making a decision).

- Free Ethics & Compliance Toolkit

- Ethics and Compliance Glossary

- Definitions of Values

- Why Have a Code of Conduct?

- Code Construction and Content

- Common Code Provisions

- Ten Style Tips for Writing an Effective Code of Conduct

- Five Keys to Reducing Ethics and Compliance Risk

- Business Ethics & Compliance Timeline

- Creating Environments Conducive to Social Interaction

Thinking Ethically: A Framework for Moral Decision Making

- Developing a Positive Climate with Trust and Respect

- Developing Self-Esteem, Confidence, Resiliency, and Mindset

- Developing Ability to Consider Different Perspectives

- Developing Tools and Techniques Useful in Social Problem-Solving

- Leadership Problem-Solving Model

- A Problem-Solving Model for Improving Student Achievement

- Six-Step Problem-Solving Model

- Hurson’s Productive Thinking Model: Solving Problems Creatively

- The Power of Storytelling and Play

- Creative Documentation & Assessment

- Materials for Use in Creating “Third Party” Solution Scenarios

- Resources for Connecting Schools to Communities

- Resources for Enabling Students

| Benefits most but not all Protects the rights of all Distributes benefits fairly among all Benefits the common good virtue and development of character Examples which can be used in early childhood settings: . Benefits most but not all. Eminent Domain is an excellent example of this. A city may wish to put in a new road or airport, for instance, and what is in the way may have to be removed or relocated (houses, fields, stores, etc.). This could be reacted with puppets, a felt story, drawings, etc. The block area would be a nice setting for it. Protects the rights of all. For example, everyone in an early childhood center deserves to be treated with respect and kindness, to have a chance to tell their side of a story, to be able to seek help when needed, to have water when thirsty, access to food when hungry, access to the bathroom when needed, access to rest when tired, and so forth. Many school settings have the children generate a Code of Conduct which applies to everyone. When children are part of the generation of a Code of Conduct, they are more invested in it and more understanding of what it is about. . Distributes benefits fairly among all. Here is an example from an early childhood center in NH: “We had an example of the Justice Model today! The children were gathered, ready to go outside to the playground. However, the door through which we usually exit was blocked due to a painting project by our maintenance peole. So, the problem to be solved was: How do we get outside today? As a group, we processed possible solutions. One child said, “We can go out through Miss Lori’s room!” Another child said, “We can go out through the kitchen!” Other options included not going out at all, or waiting until the painting project was completed. At this point, a heavy discussion ensued as to which room we should exit from. Children had very strong opinions on this. It was clear that the group was all in favor of going outside right away, but some wanted to exit through Miss Lori’s door and others through the kitchen door. I was going to facilitate our usual method of voting to determine the solution, but suddenly the Justice Ethical Model popped into my mind. Perhaps there was a way to satisfy everyone – distributing the benefits of the solution equally… I brought this up to the children, and asked if there was a solution where everyone could get their way. A couple of children said that we could go out in two groups! One group through Miss Lori’s door and the other group through the kitchen door! So we did this! Esther led the “Miss Lori door” group, and I the kitchen door group! Only an hour earlier I had been musing about how to present these rather abstract, complex ethical models to the children in a way they could understand. Fate easily resolved this situation!” Benefits the “common good.” Here is an example from an early childhood center whose children wished to have a seesaw for their playground – benefiting all of them! The story follows: Promotes virtue and development of character. Sometimes a solution to a problem may hurt someone’s feelings, or interfere with a personal vision. An example might be if a child were building a tower in the block area, and others wanted to join in. Should it then become a group building project? Collaboration, and so forth? Or should the original child be allowed to finish what he had started (Imagine if Michelangelo had had help on a sculpture, or da Vinci on one of his works…) Sometimes collaboration is good, and sometimes individual expression is good. It can be a process deciding which is most beneficial in a situation… Philosophers have developed five different approaches to values to deal with moral issues.

Utilitarianism was conceived in the 19th century by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill to help legislators determine which laws were morally best. Both Bentham and Mill suggested that ethical actions are those that provide the greatest balance of good over evil. To analyze an issue using the utilitarian approach, we first identify the various courses of action available to us. Second, we ask who will be affected by each action and what benefits or harms will be derived from each. And third, we choose the action that will produce the greatest benefits and the least harm. The ethical action is the one that provides the greatest good for the greatest number.

The second important approach to ethics has its roots in the philosophy of the 18th-century thinker Immanuel Kant and others like him, who focused on the individual’s right to choose for herself or himself. According to these philosophers, what makes human beings different from mere things is that people have dignity based on their ability to choose freely what they will do with their lives, and they have a fundamental moral right to have these choices respected. People are not objects to be manipulated; it is a violation of human dignity to use people in ways they do not freely choose. Of course, many different, but related, rights exist besides this basic one. These other rights (an incomplete list below) can be thought of as different aspects of the basic right to be treated as we choose. In deciding whether an action is moral or immoral using this second approach, then, we must ask, Does the action respect the moral rights of everyone? Actions are wrong to the extent that they violate the rights of individuals; the more serious the violation, the more wrongful the action.

The fairness or justice approach to ethics has its roots in the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who said that “equals should be treated equally and unequals unequally.” The basic moral question in this approach is: How fair is an action? Does it treat everyone in the same way, or does it show favoritism and discrimination? Favoritism gives benefits to some people without a justifiable reason for singling them out; discrimination imposes burdens on people who are no different from those on whom burdens are not imposed. Both favoritism and discrimination are unjust and wrong.

This approach to ethics assumes a society comprising individuals whose own good is inextricably linked to the good of the community. Community members are bound by the pursuit of common values and goals. The common good is a notion that originated more than 2,000 years ago in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero. More recently, contemporary ethicist John Rawls defined the common good as “certain general conditions that are…equally to everyone’s advantage.” In this approach, we focus on ensuring that the social policies, social systems, institutions, and environments on which we depend are beneficial to all. Examples of goods common to all include affordable health care, effective public safety, peace among nations, a just legal system, and an unpolluted environment. Appeals to the common good urge us to view ourselves as members of the same community, reflecting on broad questions concerning the kind of society we want to become and how we are to achieve that society. While respecting and valuing the freedom of individuals to pursue their own goals, the common-good approach challenges us also to recognize and further those goals we share in common.

The virtue approach to ethics assumes that there are certain ideals toward which we should strive, which provide for the full development of our humanity. These ideals are discovered through thoughtful reflection on what kind of people we have the potential to become. Virtues are attitudes or character traits that enable us to be and to act in ways that develop our highest potential. They enable us to pursue the ideals we have adopted. Honesty, courage, compassion, generosity, fidelity, integrity, fairness, self-control, and prudence are all examples of virtues. Virtues are like habits; that is, once acquired, they become characteristic of a person. Moreover, a person who has developed virtues will be naturally disposed to act in ways consistent with moral principles. The virtuous person is the ethical person. In dealing with an ethical problem using the virtue approach, we might ask, What kind of person should I be? What will promote the development of character within myself and my community?

These five approaches suggest that once we have ascertained the facts, we should ask ourselves five questions when trying to resolve a moral issue: This method, of course, does not provide an automatic solution to moral problems. It is not meant to. The method is merely meant to help identify most of the important ethical considerations. In the end, we must deliberate on moral issues for ourselves, keeping a careful eye on both the facts and on the ethical considerations involved. This article updates several previous pieces from by Manuel Velasquez – Dirksen Professor of Business Ethics at Santa Clara University and former Center director – and Claire Andre, associate Center director. “Thinking Ethically” is based on a framework developed by the authors in collaboration with Center Director Thomas Shanks, S.J., Presidential Professor of Ethics and the Common Good Michael J. Meyer, and others. The framework is used as the basis for many programs and presentations at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. |

These 5 approaches and their history can be found at:

Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v7n1/thinking.html

Examination of Ethical Decision-Making Models Across Disciplines: Common Elements and Application to the Field of Behavior Analysis

- Discussion and Review Paper

- Published: 29 November 2022

- Volume 16 , pages 657–671, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Victoria D. Suarez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4940-0780 1 ,

- Videsha Marya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5836-5470 1 , 2 ,

- Mary Jane Weiss ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2836-3861 1 &

- David Cox ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4376-2104 1 , 3

1445 Accesses

3 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

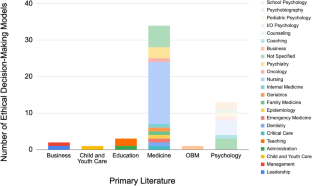

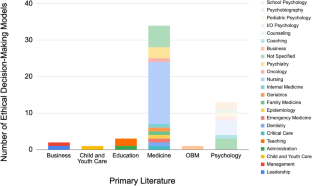

Human service practitioners from varying fields make ethical decisions daily. At some point during their careers, many behavior analysts may face ethical decisions outside the range of their previous education, training, and professional experiences. To help practitioners make better decisions, researchers have published ethical decision-making models; however, it is unknown the extent to which published models recommend similar behaviors. Thus, we systematically reviewed and analyzed ethical decision-making models from published peer-reviewed articles in behavior analysis and related allied health professions. We identified 55 ethical decision-making models across 60 peer-reviewed articles, seven primary professions (e.g., medicine, psychology), and 22 subfields (e.g., dentistry, family medicine). Through consensus-based analysis, we identified nine behaviors commonly recommended across the set of reviewed ethical decision-making models with almost all ( n = 52) models arranging the recommended behaviors sequentially and less than half ( n = 23) including a problem-solving approach. All nine ethical decision-making steps clustered around the ethical decision-making steps in the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts published by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board ( 2020 ) suggesting broad professional consensus for the behaviors likely involved in ethical decision making.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

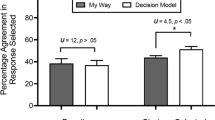

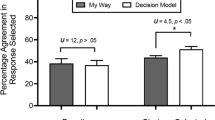

Assessing the Reliability of and Preference for an Ethical Decision Model

Promoting Ethical and Evidence-Based Practice through a Panel Review Process: A Case Study in Implementation Research

Ethical behavior analysis: evidence-based practice as a framework for ethical decision making, all articles with an asterisk indicate the final articles included in the review.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General & Applied, 70 (9), 1–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093718

Article Google Scholar

Bailey, J., & Burch, M. (2013). Ethics for behavior analysts (2nd expanded ed).

Bailey, J., & Burch, M. (2016). Ethics for behavior analysts (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315669212

Book Google Scholar

Bailey, J., & Burch, M. (2022). Ethics for behavior analysts (4th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003198550

Baum, W. M. (2017). Behavior analysis, Darwinian evolutionary processes, and the diversity of human behavior. In On Human Nature (pp. 397–415). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-420190-3.00024-7

Chapter Google Scholar

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (BACB, 2004, 2010). Guidelines for responsible conduct for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2010-Disciplinary-Standards_.pdf

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (BACB, 2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts . https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/BACB-Compliance-Code-10-8-15watermark.pdf

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (BACB, 2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts . https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-code-for-behavior-analysts/

*Boccio, D. E. (2021). Does use of a decision-making model improve the quality of school psychologists’ ethical decisions? Ethics & Behavior, 31 (2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1715802

Boivin, N., Ruane, J., Quigley, S. P., Harper, J., & Weiss, M. J. (2021). Interdisciplinary collaboration training: An example of a preservice training series. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1–14 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00561-z

*Bolmsjö, I. Å., Edberg, A. K., & Sandman, L. (2006a). Everyday ethical problems in dementia care: A teleological model. Nursing Ethics , 13 (4), 340–359. https://doi.org/10.1191/0969733006ne890oa

Article PubMed Google Scholar

*Bolmsjö, I. Å., Sandman, L., & Andersson, E. (2006b). Everyday ethics in the care of elderly people. Nursing Ethics , 13 (3), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1191/0969733006ne875oa

*Bommer, M., Gratto, C., Gravander, J., & Tuttle, M. (1987). A behavioral model of ethical and unethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics , 6 (4), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00382936