What is Material Culture?

Below are some definitions of material culture, along with a list of relevant texts links, suggested by participants at a University of Delaware workshop.

Definitions of Material Culture The things we make reflect our beliefs about the world; the things around us affect the way that we understand the world. There is an unending circularity to this that implies less a circle and more a kind of wheel moving. – Lance Winn, with respect to Foucault

Material culture is the history and philosophy of objects and the myriad relationships between people and things. –Bernie Herman

Material Culture Studies opens the question of the “thingness” of things—what is matter? How does it produce meaning, yield uses, constitute worlds? Material culture studies attends to the situation of “things,” their accreted associations and meanings as they are successively performed. Working with “things” is so rooted in experience, so tuned to how we perceive the world, so inductive, that teacher and student become fellow observers / users, equally able to respond to the strangeness of this “thing,” before them, now. “Things” matter and the knowledge they offer us transforms our sense of the habit worlds we live and make. –Julian Yates

My idea of material culture studies is a quite literal one: I see us engaged in in-depth studies of the materials of human cultures–of anything (any/thing/) for how it reflects and constructs the culture of which it is a part . –Marcy Dinius

The American Institute for Conservation’s definition for “cultural property” can loosely substitute for material culture. “The legacy of our collective cultural heritage enriches our lives. Each generation has a responsibility to maintain and to protect this heritage for the benefit of succeeding generations. Conservation is the field dedicated to preserving cultural property – objects, collections, specimens, structures, or sites identified as having artistic, historic, scientific, religious, or social significance – for future generations. -AIC website —-Jae Gutierrez

The rise of mass consumption was accompanied by a proliferation in objects and the multiplication of meanings, practices, and “needs” associated with these things. Material Culture Studies helps us to think about the objects, and the cultural, political, and economic systems that created them . –Will Scott

Material Culture is the unpacking or mining of both historic and everyday objects to find the embedded ideas and concepts that define the surrounding society . — Joyce Hill Stoner

Material culture is the relationship between people and things . —Arwen Mohun

Further notes from Arwen : Material culture scholars ask questions like: how do historical actors and present day people make and use objects like houses, books, and paintings? What did those objects mean to specific historical actors at specific moments in time? How might these meanings change over time? How have authors and artists used material things as symbols in art and literature? How do the physical characteristics of artifacts— the paper a magazine or newspaper is printed on, the cloth a garment is fashioned from—affect interpretation?

Some material culture scholars incorporate the answers to these kinds of questions into books and articles for scholarly audiences. Others incorporate them into the process of making or conserving physical objects and textual artifacts. Or work to engage the general public in appreciating the history of material objects.

Why does material culture studies matter (and who does it matter to?) It matters because we all live in a material world, but are educated in intellectual traditions that too often abstract, ignore, or decontextualize physical objects and processes.

Material culture studies promotes:

- material citizenship–recognition that things have politics and that our choices about how we

- make , buy, use, and view things are important aspects of global citizenship

- stewardship —skills to select and care for culturally significant things

- insightful new scholarship on the history of how people have made and used objects and shaped their built environments

- creativity in the creation of material culture

- common ground between the public and the academy —in K-12 education, in museum settings, as well as university classrooms and study spaces associated with various collections on this and other campuses.

Material Culture Studies intersects with Women’s Studies in fascinating ways. In every culture or community– national, ethnic, religious, or other sort – women have been and continue to be defined by notions of “femininity,” and those notions are almost always embodied by and made visible through clothing, as both material (in all senses of the word) and as ideological choices— Margaret Stetz

Critical Texts in the Field of Material Culture Studies

From Lance Winn: Marx, The Communist Manifesto (gives us the language to critique material) McLuhan, Understanding Media (apologies for claiming such an overused text but “the medium is the message” … e=mc… . squared”

De Landa, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (impossible where to even begin, start with things as an accumulation of energies)

The Electronic Disturbance by The Critical Art Ensemble (material is often now immaterial and yet somehow still affects us)

Formless: A Users Guide by Krauss and Bois (Like all the above, they equip us with language to describe things that we take for granted… better yet they have pictures as well, and an alternative history of art that does not let you see the history of making in the same way ever again.

From Bernie Herman: Judy Attfield, Wild Things . Attfield offers an extraordinary perspective on the relationship between objects and design through the notion of wildness. Wildness simply is the elusive and ambiguous nature of things in the construction of meaning–in historical, cultural, and critical contexts. Her work resonates far beyond her examples.

Francis Ponge, Soap . Ponge dedicates the medium of the “prose poem” to the explication of ordinary objects. In Soap he visits and revisits this humble object in ways that offer provocative insight into the very nature of things in their greater generality. The sleight of interpretation that enables us to realize that soap is an object that diminishes in its actualization raises questions about how analysis similarly exaggerates and lessens an object. Unlike the current burst of books about things like salt and pencils, Ponge’s essay reminds us of the poetical and magical aspects of objects.

Lynn Meskell, Object Worlds of Ancient Egypt . Meskell’s discussion of the quality of agency in things is smart and informed. With implications that range far beyond her immediate topic, Object Worlds provides a cogent argument for object biographies. The discussion on agency raises the fundamental question of how objects “act” in/on the contexts they inhabit/furnish.

William Gibson, Count Zero . Gibson’s second cyberpunk novel, Count Zero works from an evocation of Joseph Cornell’s constructions in a near future defined by virtuality and artificial intelligences. Set aside the science fiction associations and read this work of fiction as a meditation on the relationships between objects that questions the role that humans play in the production and consumption of desire and meaning.

David Howes, ed ., Empire of the Senses . This is a great collection of essays that explores the full array of the senses (including proprioception ) in the reception of the material world. Published by Berg, this is one of several readers that contain both reprinted and original essays that explore the complex terrain on which we engage materiality through the senses as well as the varied critical positions we bring to writing and interpretation.

From Julian Yates: George Perec, A Species of Space and other Pieces , trans . John Sturrock (London: Penguin, 1997)

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life , trans . Steven Rendell (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002)

Michel Serres, The Parasite , trans . Lawrence Schehr (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005)

William Pietz, “ The Problem of the Fetish 1, 2 and 2A ” Res 9, 13, and 16 (1985. 1987 and 1989)

Arjun Appadurai ( ed ), The Social Life of Things (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985)

From Marcy Dinius: Bill Brown, ed . Things . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey B. Pingree, eds . New Media: 1740-1915. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

D. F. McKenzie, Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Miles Orvell, The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture , 1880-1940 . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth . New York: Knopf, 2001.

From Arwen Mohun: Melvin Kranzberg, “At the Beginning,” Technology and Culture 1 (1959). Mel was the moving force in creating the Society for the History of Technology and its journal, Technology and Culture. This manifesto remains the most concise statement about why the history of technology should be important to all of us.

Donald Kraybill, The Riddle of the Amish . Kraybill’s explanation of how the Amish have“negotiated with modernity” through their choices about technology powerfully argues against technological determinism. He shows how the Amish have made choices about using technology in accordance with their values and, by implication, how everyone else can too.

James Scott, Seeing Like a State explores the history of how technologies of “seeing”—mapping, counting— in the hands of well-intentioned states have created human disasters.

Lerman, Mohun, and Oldenziel, editors, Technology and Culture: A Reader —most everything I know about gender and technology, I learned from working on this book.

Mike Rose, The Mind at Work is an educational sociologist’s thoughtful discussion of the changing nature of low-paid labor and skill.

From Will Scott: Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste : A theoretical examination of the relationship between objects, practices, and social relations.

Nan Enstad, Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture, and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century : The women who populate Enstad’s book are producers and consumers of fashion. It highlights the role of popular culture in constructing desires for objects.

Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style : A brilliant little book that “reads” punk style in 1970s Britain. A must read for those interested in the history of youth culture and fashion.

Karal Ann Marling, As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s : Marling treats such subjects as Disneyland, Mamie Eisenhower’s fashion, power tools, and paintby -numbers art with sensitivity and intelligence.

Anne McClintock, “Soft-Soaping Empire: Commodity Racism and Imperial Advertising”: A smart, oft-anthologized essay that demonstrates the cultural importance of one commodity— soap—in the British Empire.

Museum of Modern Art, Machine Art : The catalog accompanying the 1934 exhibition is a pictorial and textual manifesto on behalf of Bauhaus-influenced modernism, which influenced a generation of American designers.

Susan Strasser, Never Done: A History of American Housework and Waste and Want : A Social History of Trash: UD’s own Strasser examines the material transformation of the American home and the environmental consequences of the proliferation of things in these classics.

Richard Longstreth, City Center to Regional Mall: Architecture, the Automobile, and Retailing in Los Angeles, 1920-1950 : The transformation of vernacular, retail architecture told through images and keen, understated analysis.

Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class : First published in 1899, this social satire remains a powerful critique of the use of things for social advancement.

From George Basalla: Daniel Miller. The Comfort of Things D. Penney& Dr. Stasny . The Things they Left Behind. This is a book about the abandoned suitcases left in an insane asylum by inmates after their death. Includes photos and biographies of key persons. Very moving.

Deborah Cohn. Household Gods (The British and their possessions).

Barbara Stafford, an art historian, several books about material culture. Her books are heavy on theory but very good.

John Mack. The Art of Small Things

Pablo Neruda. Ode to Common Things

Roger-Pol Droit. How are Things (philosophy)

Lorraince Daston, ed ., Things that Talk . MIT Press. A big book of essays.

Bill Brown. A Sense of Things (American literature & Things)

Sherry Turkle. Evocative Objects . MIT Press.

D.B. Meli . Thinking with Objects

Simon Holloway. Corrugated Iron: Building on the Frontier . Wonderful pictures of corrugated iron buildings around the world.

H.W. Longfellow’s long poem Keramos, about the history of pottery and the value of craftsmanship

From Margaret Stetz: Through the Wardrobe: Women’s Relationships with Their Clothes . ed . Ali Guy, et al. Berg, 2001

The Fashion Reader . ed . Linda Welters and Abby Lillethun. Berg, 2007

A Perfect Fit: Clothes, Character, and the Promise of America , by Jenna Weissman Joselit. Henry Holt, 2001.

Clothing as Material Culture . eds . Susanne Kuchler and Daniel Miller. Berg, 2005

Sex and Suits . by Anne Hollander. Kodansha, 1994

Upcoming opportunities

- Winterthur Research Fellowships 2015-16

- Blithe Spirits forum

- Advancing Research Communication and Scholarship – call for proposals

Material Culture - Artifacts and the Meaning(s) They Carry

What Can the Material Culture of a Society Tell Scientists?

- Ancient Civilizations

- Excavations

- History of Animal and Plant Domestication

- M.A., Anthropology, University of Iowa

- B.Ed., Illinois State University

Material culture is a term used in archaeology and other anthropology-related fields to refer to all the corporeal, tangible objects that are created, used, kept and left behind by past and present cultures. Material culture refers to objects that are used, lived in, displayed and experienced; and the terms includes all the things people make, including tools, pottery , houses , furniture, buttons, roads , even the cities themselves. An archaeologist thus can be defined as a person who studies the material culture of a past society: but they're not the only ones who do that.

Material Culture: Key Takeaways

- Material culture refers to the corporeal, tangible objects created, used, kept, and left behind by people.

- A term used by archaeologists and other anthropologists.

- One focus is the meaning of the objects: how we use them, how we treat them, what they say about us.

- Some objects reflect family history, status, gender, and/or ethnic identity.

- People have been making and saving objects for 2.5 million years.

- There is some evidence that our cousins the orangutans do the same.

Material Culture Studies

Material culture studies, however, focus not just on the artifacts themselves, but rather the meaning of those objects to people. One of the features that characterize humans apart from other species is the extent to which we interact with objects, whether they are used or traded, whether they are curated or discarded.

Objects in human life can become integrated into social relationships: for example, strong emotional attachments are found between people and material culture that is connected to ancestors. Grandmother's sideboard, a teapot handed down from family member to family member, a class ring from the 1920s, these are the things that turn up in the long-established television program "Antiques Roadshow," often accompanied by family history and a vow to never let them be sold.

Recalling the Past, Constructing an Identity

Such objects transmit culture with them, creating and reinforcing cultural norms: this kind of object needs tending, this does not. Girl Scout badges, fraternity pins, even Fitbit watches are "symbolic storage devices," symbols of social identity that may persist through multiple generations. In this manner, they can also be teaching tools: this is how we were in the past, this is how we need to behave in the present.

Objects can also recall past events: antlers collected on a hunting trip, a necklace of beads obtained on holiday or at a fair, a picture book that reminds the owner of a trip, all of these objects contain a meaning to their owners, apart from and perhaps above their materiality. Gifts are set in patterned displays (comparable in some respects to shrines) in homes as markers of memory. Even if the objects themselves are considered ugly by their owners, they're kept because they keep alive the memory of families and individuals that might otherwise be forgotten. Those objects leave "traces," that have established narratives associated with them.

Ancient Symbolism

All of these ideas, all of these ways that humans interact with objects today have ancient roots. We've been collecting and venerating objects since we started making tools 2.5 million years ago , and archaeologists and paleontologists are today agreed that the objects that were collected in the past contain intimate information about the cultures that collected them. Today, the debates center on how to access that information, and to what extent that is even possible.

Interestingly, there is increasing evidence that material culture is a primate thing: tool use and collecting behavior have been identified in chimpanzee and orangutan groups.

Changes in the Study of Material Culture

The symbolic aspects of material culture have been studied by archaeologists since the late 1970s. Archaeologists have always identified cultural groups by the stuff they collected and used, such as house construction methods; pottery styles; bone, stone and metal tools; and recurring symbols painted on objects and sewn into textiles. But it wasn't until the late 1970s that archaeologists began to actively think about the human-cultural material relationship.

They began to ask: does the simple description of material culture traits sufficiently define cultural groups, or should we leverage what we know and understand about the social relationships of artifacts to get to a better understanding of the ancient cultures? What kicked that off was a recognition that groups of people who share material culture may not ever have spoken the same language, or shared the same religious or secular customs, or interacted with one another in any other way other than to exchange material goods . Are collections of artifact traits just an archaeological construct with no reality?

But the artifacts that make up material culture were meaningfully constituted and actively manipulated to attain certain ends, such as establishing status , contesting power, marking an ethnic identity, defining the individual self or demonstrating gender. Material culture both reflects society and is involved in its constitution and transformation. Creating, exchanging and consuming objects are necessary parts of displaying, negotiating and enhancing a particular public self. Objects can be seen as the blank slates upon which we project our needs, desires, ideas and values. As such, material culture contains a wealth of information about who we are, who we want to be.

- Berger, Arthur Asa. "Reading matter: Multidisciplinary perspectives on material culture." New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Coward, Fiona, and Clive Gamble. " Big Brains, Small Worlds: Material Culture and the Evolution of the Mind ." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 363.1499 (2008): 1969-79. Print.

- González-Ruibal, Alfredo, Almudena Hernando, and Gustavo Politis. " Ontology of the Self and Material Culture: Arrow-Making among the Awá Hunter-Gatherers (Brazil) ." Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 30.1 (2011): 1-16. Print.

- Hodder, Ian. Symbols in Action: Ethnoarchaeological Studies of Material Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. Print.

- Money, Annemarie. " Material Culture and the Living Room: The Appropriation and Use of Goods in Everyday Life ." Journal of Consumer Culture 7.3 (2007): 355-77. Print.

- O'Toole, Paddy, and Prisca Were. " Observing Places: Using Space and Material Culture in Qualitative Research ." Qualitative Research 8.5 (2008): 616-34. Print.

- Tehrani, Jamshid J., and Felix Riede. " Towards an Archaeology of Pedagogy: Learning, Teaching and the Generation of Material Culture Traditions ." World Archaeology 40.3 (2008): 316-31. Print.

- van Schaik, Carel P., et al. " Orangutan Cultures and the Evolution of Material Culture. " Science 299.5603 (2003): 102-05. Print.

- Skraelings: The Viking Name for the Inuits of Greenland

- Ethnoarchaeology: Blending Cultural Anthropology and Archaeology

- Archaeology Clubs for Amateurs

- Exchange Systems and Trade Networks in Anthropology and Archaeology

- Prehistoric Stone Tools Categories and Terms

- Archaeology Subfields

- The Invention of Pottery

- Stratigraphy: Earth's Geological, Archaeological Layers

- Luminescence Dating

- Post-Processual Archaeology - What is Culture in Archaeology Anyway?

- Processual Archaeology

- Three Age System - Categorizing European Prehistory

- Quarry Sites: The Archaeological Study of Ancient Mining

- Uncovering the Archaeological Remains of Tipis

- Wootz Steel: Making Damascus Steel Blades

- Acheulean Handaxe: Definition and History

- Material Culture

- Primary Sources

- Research Projects

Home > Essay 1: Material Culture

Essay 1: Material Culture

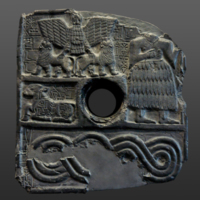

Essay 1 focuses on the analysis of an object chosen from a pre-selected collection. The goal is to contextualize the object and use it as a starting point to discuss some of the larger topics covered in the course.

Relief of Ur-Nanše

Standard of Ur (Peace Side)

Standard of Ur (War Side)

Stele of Ušumgal

Banquet Plaque from Tutub

Votive Plaque of Dudu

Obelisk of Maništušu

Victory Stele of Narām-Sîn

Expelled from the Garden of Eden

by Ricardo Jasso Huezo

Why would a politician —the leader of a certain political group— call himself a "god"? Even more, why would the "divinity" of a leader be depicted in a public monument? What is behind the "Victory Stele" of Akkadian king Naram-Sin?

Standard of Ur (War)

by Robert Ledniczky

As Britain consolidated their colonial power in the wake of the first world war, other agents of the Empire were engaging in other operations, including imperial excavation. Between 1922-1934, British archeologist Leonard Woolley would conduct his most famous excavations for the British Museum in partnership with the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

The Centralization of Power Through Economic Conquest: The Obelisk of Manishtushu

by Andrew Pottorf

Over the span of roughly two centuries, the Sargonic dynasty attained a greater level of territorial control than previously realized in the ancient Near East, achieving what may be considered the world’s first empire. This empire was formed and maintained through conquests, both military and economic, that transferred political power from various city-states and regions to the Sargonic rulers and their loyal dependents.

Standard of Ur: A Story of Social Organization

by Ameek Shokar

In the late 1920s, British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley embarked on journey to complete an extensive excavation of the ancient city of Ur. The prize discovery of Woolley’s dig was a trapezoidal wooden object that has become known as the Standard of Ur. The object was found in the tomb of next to a man who Woolley believed might have used the object as a standard used a symbol of the state in battle.

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Material Culture

Introductory Essay Material Culture and the Meaning of Objects

- Material Culture 48(1):1-9

- Center for the Study of Cuban Culture + Economy

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Emmanuel B Garcia

- Andres Suhendrawan

- Graciela Mayet

- Michael Hughes

- Daniel Keenen

- Cult Surviv Q

- Emilio Morales

- Henri Lefebvre

- Michel Maffesoli

- S. A. Leblanc

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Material Culture

- Getting Started

Material Culture: Getting Started

- Objects and Artifacts

- Print as Material Culture

- Additional Resources

Understanding Material Culture Studies

What is material culture? Material culture studies? And what does materiality mean?

Material culture are physical objects, resources, and spaces that people use to define their culture. This can include furniture, clothing, toys, tools, buildings, and architecture. Print material culture can include items like music sheets, comic books, and magazines in addition to books. Non-material culture includes things like beliefs, values, and social roles.

Material culture studies is the scholarly analysis of material culture. This is typically done within fields like archeology and anthropology, but it is also of interest within the fields of history, sociology, and cultural geography. Material culture studies engages with methodologies and interests across disciplines, united through an interest in studying the relationship between people and their relationship to things.

Materiality is a concept used when analyzing material culture within the social sciences. It is generally the idea that the physical properties of an object impacts the way it is used. In material culture studies, this can be used to better understand an obscure item or to learn about cultural practices and use through an analysis of its physical qualities and condition.

Introduction

This guide is intended to help students with being their research on material culture and materiality in the Rubenstein Library. In addition to holding various manuscripts, books, and journals, the Rubenstein Library also holds numerous objects and artifacts in its collections. Typical archival and print material like manuscripts and books can also be the subject of material culture studies and this guide provides an introduction to students for viewing printed material beyond their texts.

Note: It is neither a complete guide to material culture studies nor a comprehensive list of object and artifact resources in the Rubenstein Library. This guide is an entry point, and provides a sample of some of the resources we have available and how they can be used for research. For the next step in researching material culture and materiality, I would encourage you to reach out to Rubenstein staff directly or through our contact form .

Online Resources

- Teaching Materiality Online with the Rubenstein Library While this guide is focused on teaching materiality in an online, remote, classroom setting, it also provides some good exercises and explanations for learning about materiality and material culture.

- Journal of Material Culture Journal of Material Culture explores the relationship between artefacts and social relations. It draws on a range of disciplines including anthropology, archaeology, design studies, history, human geography and museology.

Materials in Our Collections

Rare large two-sided silk banner reading “Justice” carried in parades by the Ilford (London) Women's Social and Political Union in 1909-1910, from the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection .

Confederate pocketbook from the Trinity College Historical Society collection .

Prosthetic glass eyeballs from the History of Medicine artifacts Collection .

Recommended Reading

- Next: Objects and Artifacts >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 2:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/material_culture

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Stones, Bones and the Sacred: Essays on Material Culture and Religion in Honor of Dennis E. Smith. Early Christianity and its literature

Bilal bas , marmara university. [email protected].

Preview [The Table of Contents is listed below.]

Material products of any religious tradition such as buildings, monuments, graveyards, dress, food, musical instruments, ritual objects are considered by scholars to be revealing of a tradition’s world view. Material culture thus tells us as much about a religion as texts, beliefs, and dogmas. Moreover, it has the capacity to open up new areas of investigation where literary evidence remains silent. Literary culture of a religion such as Christianity is often considered to reflect the concerns and preferences of a cultural elite that generally represented what scholars call the “official religion”. The ordinary members of religion often experience religious life in ways that differ from elites, hence the term “popular religion”. In addition to furnishing us insights about the world of the elite, material culture also provides us with many insights about that of ordinary people. In the attempt to reconstruct these varying worlds, material culture has been employed in the study of religion for quite some time and archaeology has become a major provider of evidence for historical constructions of religions. Yet one should always keep in mind that archaeological evidence does not give us as direct information as literary evidence because, since it cannot speak for itself, it is always open to various interpretations.

Reconstruction of early Christianity is often difficult on account of the scarcity of literary evidence. As a result, material evidence provided by archaeological research is increasingly employed in the study of early Christianity and the New Testament in order to shed light on various areas of investigation where literary sources are largely silent. The late Helmut Koester of Harvard Divinity School was a prominent scholar who actively engaged in archaeological investigation as an aid to New Testament scholarship. The combination is challenging and difficult for it requires expertise in two rather difficult and demanding disciplines. This brings us to his student and heir Dennis E. Smith who successfully engaged in both disciplines with his pioneering work on meals in Greco-Roman Antiquity and to the Colloquium on Material Culture and Ancient Religion (COMCAR) in which most of the authors of this volume participated.

Stones, Bones, and the Sacred is a collection of 16 essays on material culture and ancient religion in honor of Dennis E. Smith edited by Alan H. Cadwallader. In the first essay, Hal E. Taussig presents a general evaluation of Dennis E. Smith’s scholarship and the final essay is written by Smith himself as a response to the essays. In general, the essays focus on the intersection of material culture, ancient religion, and the texts and practices of early Christianity. Many of the authors attempt to employ the interpretation of material culture in the New Testament exegesis and Christian origins (Ibita, Økland, Huber, Cadwallader, Kurek-Chomycz and Bieringer, Weima, Thompson, and Wilson). A group of scholars employ literary and material evidence in order to explore meals in Greco-Roman world and early Christianity (Ibita, Alikin, Friesen, Schowalter, Dyer, Økland).

All the essays are well-written, learned contributions to their respective fields and thus worth mentioning. However, due to the limited space allowed for a book review, there is room to review only some of them.

In “Embodied Inequalities: Diet Reconstruction and Christian Origins”, Steven J. Friesen analyzes the findings of the literature on diet reconstruction in the Roman Empire and the reasons of inequality in food distribution in order to show the ways in which the earliest churches distributed their sources differently. The data is obtained mainly through a new method, stable isotope analysis of skeletal remains. Friesen suggests that though the data is not yet sufficient enough to reach general conclusions, it still allows us to explore questions of inequality related to an individual’s regional origins, gender, age, occupation, status, and urbanity, and in relation to this, it may also enable us to study ways the earliest Christians positioned themselves in terms of inequality of food distributions. It may furnish a promising avenue, suggests Friesen, for examining redistributions of food in early church rituals, food charity and nonritual distribution of food, as well as the discursive deployment of hunger and the symbolic potential of nourishment in the texts and the narrative significance of food and hunger in Christian literature. Though this new tool does indeed look promising for opening up new doors to various questions, the data provided by the method is to date meagre and therefore insufficient to create reliable reconstructions.

In “Eating Words in the New Testament”, Keith Dyer compares the statistics of eating and banqueting vocabulary of the New Testament with those of Josephus’s writings in order to evaluate the Smith-Klingardt paradigm that the Greco-Roman banquet across the Mediterranean world was the primary model for all main meal dining (including Jewish and early Christian meals) in the first century of the Common Era and beyond. The statistics are remarkable in that in comparison with the numerous uses in Josephus, the New Testament authors rarely used the vocabulary related to banqueting. Dyer explains this situation by referring to the sensibilities of NT writers, in particular of Paul, to their addressees who mostly came from lower strata of society, namely poor people and slaves who had little opportunity to participate in such banquets. Even Dyer’s findings promise new insights into the social structure of the earliest Christian communities, they represent a challenge to the Smith-Klingardt paradigm.

In “Making Men in Rev 2-3: Reading the Seven Messages in the Bath-Gymnasiums of Asia Minor”, Lyn R. Huber employs the bath-gymnasium culture the Roman Anatolia to reconstruct the meaning of the messages of Rev 2-3 to seven churches in conversation with the masculine gender in the Roman world. She suggests that it is possible to see how the messages participate in a cultural imagination of a masculine ideal, by envisioning a victor whose endurance leads to reward in a New Jerusalem. The essay shows that the bath-gymnasium complex was a cite designed for the production of virtuous and disciplined young men. Endurance in face of trials and hardships, discipline, physical harmony, moderation and courage were considered qualities necessary to become an ideal man. Since certain features of Rev 2-3 evoke the ways masculinity was constructed in the bath-gymnasium, Huber concludes that it is possible that Rev imagines audience members whose identities are shaped in relation to this culture. It is a well-structured argument, and the parallels are striking; yet this canon of virtues cannot be easily specified for the bath-gymnasium context as they are common in Greco-Roman culture in general.

In “At the Origins of Christian Apologetic Literature: The Politics of Patronage in Hadrianic Athens”, William Rutherford mainly focuses on Hadrian’s religious performances and public acts of munificence toward Athens, in search for possible reasons for the emperor’s special favors to the city. He suggests that as the seat of the Panhellenion, Athens assumed a central role in the emperor’s program of uniting Roman West with Greek East. He also mentions that his patronage of Athens served as an intertext for Aristides’s Apology which he shows was a work of political theology, thereby suggesting a similarity between the political ideology of the emperor’s benefactions and that of the argument of Aristides’s work. As all political theologians of early church history from the Apostle Paul down to Eusebius of Caesarea present similar Stoic outlooks derived from their Greco-Roman pagan counterparts, Rutherford’s construction is persuasive.

In “One Grave, Two Women, One Men: Complicating Family Life at Colossae”, the editor of the volume Alan H. Cadwallader attempts to identify the possible audience of Paul’s instructions for maintaining the Roman nuclear family relations in his letter to Colosseans (3:18-25) by exploring the indications of family and household at Colossae derived from the epigraphy and reliefs of funerary stones and monuments. He suggests that an analysis of several epitaphs and funerary monuments reveals a rather “variegated scene of households and differentiated family structures and that none of the epitaphs fits the form implied in the code in the letter.” Cadwallader argues that if these epitaphs are a representative sample of Colossian society, then perhaps the code had little to do with the membership of the Colossian congregation and suggests that possibly the letter had another audience, fictive or otherwise, in view. The essay is well-written with an impressive interpretation of the material evidence even if the evidence unearthed to date is insufficient to reach a reliable construction of the Colossian society.

In “The Baptists of Corinth: Paul, the Partisans of Apollos, and the History of Baptism in Nascent Christianity,” Stephen J. Patterson focuses on the story of how baptism came to be a rite practiced within nascent Christian communities. The author examines the context of 1 Cor 1:11-13 as the earliest mention of baptism and concludes that figures like Apollos have to be the missing link in the history of baptism. If we take him as a baptist who baptized like John, Patterson convingly argues, then baptism came not from Christians like Paul, but from baptists like Apollos. The rite was later appropriated by Christian communities as the initiation ritual by which everyone joined the church.

The final essay of the volume is a response by Dennis E. Smith to all contributions, grouped under the titles of “Material Culture”, “Meals in the Greco-Roman World”, and the “New Testament and Christian Origins”. Taken together the essays make a substantial contribution, with Smith’s words, “in exhibiting the interrelationship between the interpretation of material culture and New Testament exegesis.”

Table of Contents

Preface, p. xvii The Scholarship of Dennis E. Smith, Hal E. Taussig, p. xix Embodied Inequalities: Diet Reconstruction and Christian Origins, Steven J. Friesen, p. 9 Food Crises in Corinth? Revisiting the Evidence and Its Possible Implications in Reading 1 Cor 11:17-34, Ma. Marilou S. Ibita, p. 33 Don’t Take It Lying Down: Nondining Features of the Omrit Temple Excavations, Daniel N. Schowalter, p. 55 Eating Words in the New Testament, Keith Dyer, p. 69 Ancient Drinking in Modern Bible Translation, Jorunn Økland, p. 85 Making Men in Rev 2-3: Reading the Seven Messages in the Bath-Gymnasiums of Asia Minor, Lynn R. Huber, p. 101 At the Origins of Christian Apologetic Literature: The Politics of Patronage in Hadrianic Athens, William Rutherford, p. 129 One Grave, Two Women, One Man: Complicating Family Life at Colossae, Alan H. Cadwallader, p. 157. The Corinthian χαιναí χτíσεις? Second Corinthians 5:17 and the Roman Refoundation of Corinth, Dominika Kurek-Chomycz and Reimund Bieringer, p. 195 Women as Leaders in the Gatherings of Early Christian Communities: A Sociocultural Analysis, Valeriy A. Alikin, p. 221 The Political Charges against Paul and Silas in Acts 17:6-7: Roman Benefaction in Thessalonica, Jeffrey A. D. Weima, p. 241. Paul’s Walk to Assos: A Hodological Inquiry into Its Geography, Archaeology, and Purpose, Glen L. Thompson and Mark Wilson, p. 269. The Baptists of Corinth: Paul, the Partisans of Apollos, and the History of Baptism in Nascent Christianity, Stephen J. Patterson, p. 315 A Response, Dennis E. Smith, p. 329 List of Contributors, p. 335 Index of Ancient Sources, p. 339 Index of Place Names, p. 352 Index of Modern Authors, p. 355 Index of Subjects, p. 361

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Art / Architecture

- Aviation / Military / Space

- In the Classroom

- Museum Studies

- National Air and Space Museum Titles

- National Museum of African American History and Culture

- National Museum of American History Titles

- National Museum of Natural History Titles

- National Museum of the American Indian Titles

- Performing Arts

- Photography

- Recent Releases

- Science / Nature

- Smithsonian

- Upcoming Titles

History From Things: Essays on Material Culture

Available from the following retailers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianbooks-media.s3.amazonaws.com/retailers/amazon.jpg.100x40_q85.jpg)

Product Description

Author information, review quotes, more from museum studies.

51 Material Culture Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Material culture refers to the physical objects that are a meaningful part of a culture. It includes anything from buildings and tools to clothes and art.

It can be divided into two categories: movable and immovable. Movable objects are those that can be easily transported, such as furniture and clothing. Immovable objects are those that are fixed in place, such as houses and monuments.

Material culture is important because it helps us to understand how people lived in the past and present. By studying the objects that they used, we can learn about their customs, beliefs, and way of life.

Definitions of Material Culture

Common definitions include:

- Woodward (2007, p. 7) provides a nice simple definition where he calls material culture “objects as elements of culture”

- A more detailed definition comes from Dant (1999, p. 1) who calls material culture “things, both natural and man-made, [that] are appropriated into human culture in such a way that they re-present the social relation of culture, standing in for human beings, carrying values, ideas, and emotions”

Go Deeper: Learn About the Sociology of Culture

Examples of Movable Material Culture

Books, as artifacts of a time and place, can tell us about the interests and concerns of a culture. They contain explanations of the non-material elements of a culture because they record and share knowledge.

2. Clothing

Every culture, and even every generation, has their own approach to fashion. For example, bell-bottoms were popular in the 1970s, while skinny jeans were popular in the 2010s.

Clothing can also tell us a lot about the modesty of a culture. Today, Western beaches are full of bikinis, whereas in many Middle Eastern countries, modesty commands that women cover their bodies more while at the beach.

Just as with clothing, different cultures have different toys. For example, the Japanese love Hello Kitty, while Americans love Transformers. In the past, toys were often made of wood, whereas today, they’re generally made from plastic. In the future, this will help historians to locate the era of their archaeological digs.

Related Article: 63 Non-Material Culture Examples

4. Decorations

In the United States, people often put up Christmas trees and hang stockings over the fireplace. Meanwhile, in Thailand, people often put up ornate paper lanterns during the Buddhist holiday of Loi Krathong.

There are periods of time when certain artistic styles become the dominant forms of art. For example, in the Renaissance era, paintings were often of religious scenes, while in the Impressionist era, paintings were often of landscapes.

One culture with unique shoes is the Dutch culture. Traditional Dutch shoes are called klompen, and they are made from wood. In the west, we call them clogs. These shoes are often crafted from a single block of wood and painted with bright colors.

7. Magazines

Magazines are a great example of material culture because they reflect the interests of a particular culture at a particular time. For example, in the 1950s, magazines were often filled with advertisements for new appliances and cars. Today, magazines are often filled with advertisements for luxury vacations and clothes.

8. Musical Instruments

Each culture has its own musical instruments. The sitar, for example, is a popular Indian instrument made from wood and metal. The bagpipes, on the other hand, are a popular Scottish instrument made from animal intestine and wood.

9. Board Games (such as Chess)

The oldest chess set in the world is from India and it is estimated to be around 1,500 years old. This showed archaeologists that chess is a game that has been popular in many different cultures for a very long time. By tracking chess sets from digs around the world, we can map how the game spread around the world.

10. Cuisine

Different cultures have different cuisines. For example, French cuisine contains a lot of butter and cream, while Thai cuisine contains a lot of spicy chili peppers. American cuisine is often a mix of different cuisines, revealing how this culture is a mixing pot of migrants coming from many other cultures.

11. Ornaments

Different cultures have different ornaments. For example, Native Americans often have Dreamweavers in their homes. In China, people often put up red lanterns during the New Year. These ornaments can tell us a lot about cultures’ histories, values, and traditions.

12. Furniture

Furniture trends vary by culture. In Sweeden, for example, there is a trend of using minimalist furniture in homes. By contrast, in the United States, it is often popular to have big, plush sofas and chairs in homes.

13. Technology

Technology is a great example of material culture because it changes so rapidly. For example, the first cell phone was released in 1983, and now there are phones that can be used to surf the web, take pictures, and even make phone calls. By studying old cell phones, historians of the future will be able to learn about the technological advances that have been made over the years.

Different cultures have different tools. The Inuit, for example, have a tool called an ulu, which is a knife that is used to cut meat and fish. The Inca, on the other hand, have a tool called a quipu, which is used to record numbers and data. By studying different cultures’ tools, we can learn a lot about their lifestyles and the ways in which they interact with their environment.

15. Sculptures

Sculptures can reveal the artworks and preferences of different cultures at points in time. For example, the terracotta army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang is a collection of sculptures that were made in China over 2,000 years ago. We can contrast the outfits of these sculptures to those of the ancient Greek sculptures to contrast various parts of the cultures – including clothing and artistic styles.

16. Weapons

Weapons are a great example of material culture because they can show us the technological developments of cultures over time. In North America, the different styles of arrowheads at archaeological sites can show when the site was used and by which cultural group.

17. Writing and Alphabet

While knowledge is an example of non-material culture , the way in which it is recorded is material culture. For example, the Greek alphabet is a cultural artifact of the Greek culture, whereas the Latin alphabet (which the English language still uses today) is an artifact of English culture.

18. Souvenirs

Souvenirs are objects kept to memorialize good times, especially special events or trips. They are typically created or purchased by tourists and represent the culture of the place they are visiting. For example, a tourist who visits Greece may buy a replica of an ancient Greek vase as a souvenir.

19. Archives

Archives include libraries, personal files, and government files. While archives may hold within them nonmaterial knowledge, they are the material texts that maintain that knowledge. Here, we can see an example of how nonmaterial culture can be turned into material culture.

20. Tattoos

Some cultural groups tattoo themselves as a sign of their cultural pride or identity. For example, the Maori people of New Zealand tattoo their faces with designs that demonstrate their fierce warrior history.

Coins can be seen as a type of material culture because they are used as a means of exchange in many cultures. They can be made from a variety of materials, such as gold, silver, and bronze, and they often depict the cultural values of the group that created them. For example, Roman coins often depict the image of the emperor on one side and a symbol of the Roman gods on the other.

22. Jewelry

Jewelry is often used as a way to show off the wealth and status of its owner. It can be made from a variety of materials, such as gold, silver, and bronze, and it often depicts the cultural values of the group that created it. For example, Celtic jewelry is often made from gold and silver and is decorated with intricate designs that represent the Celtic culture.

23. Pottery

Pottery is commonly extracted during archaeological digs. It can be used to date the site and identify who used it, as different cultures have their own unique pottery styles. It can also tell us about the diet and lifestyle of a culture, as different cultures use pottery for different purposes. For example, the ancient Greeks used pottery to cook food, whereas the Inuit people of the Arctic use pottery to store food.

24. Garbage

While it may not be pleasant to sift through, our garbage says a lot about our culture. It can show us what we deem important enough to discard and what we think is worth keeping. It can also tell us about our technological progress, as different cultures have different methods of garbage disposal. For example, the ancient Greeks simply threw their garbage on the ground, whereas modern-day societies have garbage cans, landfills, and incinerators.

Chests are commonly found on archaeological sites and they can be figurative goldmines for historians because they often preserve what is left inside. The oldest chest in the world was found in Bulgaria and it is over 7,000 years old. It is decorated with intricate carvings that depict the culture of the people who made it.

26. Coffins

Coffins are often used to bury the dead and as a result, they can provide archaeologists with valuable information about a culture. For example, the ancient Egyptians used coffins to protect the bodies of their Pharaohs from decay. They were also decorated with hieroglyphics and other images that told the story of the Pharaoh’s life.

27. Cutlery

Cutlery is surprisingly variable across cultures. Furthermore, what the cutlery is made of is indicative of the time period of the culture (e.g. bone, wood, or metal). In the East, the most common cutlery is chopsticks, while in the West, forks and knives are more common.

28. Figurines

Figurines are often used to represent the deities or heroes of a culture. They can be made from a variety of materials, such as stone, clay, and metal, and they often depict the cultural values of the group that created them. For example, the ancient Greeks created figurines of their gods and goddesses out of marble and bronze. These figurines were often used in religious ceremonies. Thus, figurines are examples of material culture that can often reveal insights into the culture’s religion.

Masks are often used in religious ceremonies to represent the gods or heroes of a culture. They can be made from a variety of materials, such as stone, clay, and metal, and they often depict the cultural values of the group that created them. For example, the ancient Egyptians used masks to represent their gods and goddesses. These masks were often used in religious ceremonies. Thus, like figurines, masks are examples of material culture that can often reveal insights into the culture’s religion.

30. Religious Artifacts

Religious artifacts can include items such as statues, paintings, and jewelry. They are often used to represent the deities or heroes of a culture. They can also be used in ceremonies such as weddings, funerals, and baptisms. A unique real-life example of a religious artifact is the Ark of the Covenant, which is a chest that contains the Ten Commandments.

31. Handheld Technologies

Handheld technologies will be studied for generations to come as cultural artifacts of the 21st Century. They will be able to tell future historians a lot about our culture. They will labor over why we were so obsessed with these little machines, and even dependant upon them to the extent people get anxious without them by their sides.

32. Writing Implements

Writing implements, like all technologies, have progressed over time. They can tell us a lot about the culture that created them. For example, ancient cultures often wrote on papyrus with reeds, while modern cultures often use paper and pens. This difference can tell us about the development of writing in different cultures.

Flags are used to represent the country or culture that created them. The colors and symbols on the flags have important meanings for cultures. For example, the United States flag has 13 stripes, which represent the original 13 colonies. The 50 stars on the flag represent the 50 states in the United States.

34. Boats and Canoes

Historians can look at the boats and canoes of different cultures and deduce a great deal about their naval activities. For example, the long thin boats of Vikings had their shape because they were designed to be able to sail in shallow water and beaches. This allowed them to raid coastal villages without having to worry about getting stuck.

35. Textiles

Textiles are used in a variety of ways by different cultures. They can be used to make clothing, bedding, and other household items. Textiles can also be used to make religious objects, such as tapestries and flags. By studying the textiles in a culture’s history, we can learn about the different ways cultures produced their products as well as what crops were prevalent in their societies for the production of fabrics.

Examples of Immovable Material Culture

36. places of worship.

As with houses, different cultures have different approaches to places of worship. Mosques, for example, are often very ornate and decorated with intricate carvings and calligraphy. Many European Catholic churches are laced with gold and amazing artworks to demonstrate the medieval Church’s wealth. Meanwhile, Protestant churches in America are often very plain and simple, with little decoration.

37. Landscaping and Gardens

The ways in which we landscape our yards can reveal things about our cultures. For example, Japanese landscaping is often very zen, with carefully placed rocks and gravel pathways. American landscaping is often much more chaotic, with large trees and flower gardens.

38. Monuments

Monuments are constructed to memorialize things that are important to a cultural group. They can be used to commemorate important events or people in a culture’s history. As a result, they’re quintessential examples of material culture. An example of a cultural monument is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C., which commemorates the American soldiers who were killed or went missing during the Vietnam War.

39. Museums

Museums house a wide range of material cultural artifacts. This can include anything from paintings and sculptures to tools and furniture. By studying the objects in museums, we can learn a lot about the cultures that created them. For example, by studying the pottery in a Chinese museum, we can learn about the different styles of pottery that have been produced in China over the years.

40. Relic Boundaries

Relic boundaries are boundary lines such as walls and fences that have fallen into disuse. These boundaries can reveal the edges of ethnic groupings, cultural faultlines, and the the rise and fall of civilizations. An example of a relic boundary is the Berlin Wall which still stands as a memory of the split between communist and capitalist ideologies in Europe during the 20th Century.

41. Cave Paintings

Cave paintings are some of the oldest examples of material culture. They can be found in caves all over the world, and they typically depict scenes from the culture’s mythology or daily life. By studying cave paintings, we can learn about the beliefs and daily life of the cultures that created them. The oldest cave painting in the world is the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave painting, which is around 32,000 years old.

42. Skyscrapers

Skyscrapers are monuments to the engineering feats of modern societies. They are some of the tallest and most impressive buildings in the world, and they serve as icons of the cultures that built them. The Burj Khalifa, which is located in Dubai, is currently the tallest building in the world.

43. Roads and Highways

Roads and highways are some of the most visible examples of material culture. They are essential to the functioning of a society, and they can be used to measure a society’s level of development. For example, the interstate highway system in the United States is a symbol of the country’s high level of development.

44. Bridges

Bridges are another type of infrastructure that can be used to measure a society’s level of development. They are often considered to be symbols of strength and unity, and they can be used to connect different geographical regions. The Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco is an example of an iconic bridge that has come to represent its city and American ingenuity.

Ruins are physical evidence of a culture’s decline. They can be used to study the causes of a culture’s downfall, and they can provide insights into the lifestyles of past cultures . The ruins of Machu Picchu in Peru are an example of an ancient ruin that is still being studied by archaeologists today.

Different cultures have different approaches to housing which can tell us things about how they live their lives. For example, the houses in downtown Amsterdam are tall and skinny; while houses in the United States are often large and spread out across sprawling suburbs.

Furthermore, each culture has their own approach to the architecture of houses. In the United States, you will see houses that look like McMansions, while in Australia you will see the quintessential red brick house or ‘Queenslander’ which is built on stilts to allow for cool air to run below the house.

47. Stadiums

The Colosseum in Rome is an example of an ancient stadium that still stands as a piece of the material culture of Ancient Rome. It memorializes the ancient and brutal Gladiator sports of the Romans. Today, stadiums are used to host sporting events and other large-scale entertainments. They are often symbols of the cultures that built them and the moment in time in which they were built – for example, many countries build new stadiums to host the Olympic Games and show off the grandeur of their culture.

48. Pyramids

The oldest pyramid in the world is the Pyramid of Djoser , which was built in 2630 BCE. Pyramids are some of the most iconic examples of ancient Egyptian and Mayan architecture, and they serve as memorials to the cultures who built them. Today, pyramids are popular tourist destinations and symbols of ancient culture.

49. Castles

Castles are some of the most well-known examples of medieval architecture. They were used as fortresses by the nobility in medieval Europe, and they often housed large numbers of people. Castles are popular tourist destinations today, and they are seen by archaeologists as representative of the cultures of medieval Europe.

50. Road Signs

Road signs are a type of communication technology that is used to direct traffic. They vary in design depending on the culture that created them, and they can be used to indicate the type of road that is being traveled on, the speed limit, and the direction that the driver should be going.

51. Physical Advertising

The number of physical advertisements in our cities, on our roads, and even on our trains, is a symbol of the late-capitalist culture in which we live. Even today, scholars examine these adverts to generate insights into how our culture operates and how it’s propagated through the narratives promoted in adverts.

Material vs Non-Material Culture

In cultural anthropology , material culture is contrasted to non-material culture. Whereas material culture is the physical stuff that is representative of a cultural group, non-material culture is the knowledge, ideas, ideology, memories, dances, folklore and other elements of culture that exist in abstract rather than physical forms.

Material culture is important because it helps us to understand how people lived in the past and present. By studying the objects that they used, we can learn about their customs, beliefs, and way of life. For example, the traditional dress of a region can tell us about its climate and geography, and social structure.

Material culture can also be used to track the spread of ideas and technologies. For example, the invention of the printing press can be traced by looking at the material culture of different regions.

References:

Dant, T. (1999). Material culture in the social world . London: McGraw-Hill Education.

Woodward, I. (2007). Understanding material culture . London: Sage.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

Essays on material culture

- Studentshare

- Material Culture

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

Non-Material and Material Culture Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Material and non-material aspects of culture differ primarily based on the focus of the two approaches. Material culture is focused on resources, objects, and spaces that are significant to and define a larger culture. This can refer to locations such as cities, temples, or even workplaces as much as to tools and goods. On the other hand, non-material culture is entirely concerned with non-physical ideas and values that are inherent to cultures (Alabama State Department of Education, 2020). These may often manifest as norms, rituals, beliefs, morals, institutions, organizations, and language. The non-material components of culture often result in a guide or set of rules that dictate the relationship of events, objects, or other factors with people. In the case of religion, the existence of non-physical languages, values, norms, and symbols is especially significant.

Both non-material and material culture has drastically evolved and changed in recent decades. Material goods have significance to many individuals as a signifier of comfort. Technology is an especially relevant factor of the material culture as it permeates all aspects of life, from personal to professional. Non-material culture varies among cultural and national groups, though an overall decline in the reliance on norms and rituals can be observed. Organizational structure and behaviors have become more significant than the experiences in most other forms of collectives such as religious groups, local communities, and other areas of life.

In my personal experience, I have had mostly positive experiences among people involved in alternative subcultures. The presence of self-identification and a more original form of self-expression is important among such individuals. I find this to be an important concept in my own life, as it is important to recognize your own identity outside of your work and career. The subculture often relies on art forms such as music, dance, performance, and other forms of creation to form a community and communicate its identity.

Alabama State Department of Education. (2020). What is culture? Alabama State Department of Education. Web.

- The Most Influential Cultural Phenomenon That Has Influenced Americans' Lives

- The Analysis of Christmas as a Cultural Context of Consumption

- Aboriginals' Living Conditions in Canada

- Duties and Responsibilities of the US Army Under Title Code 10

- Demand and Supply as Basic Concepts in a Market Economy

- Developing Cultural Awareness in Tour Around Wroclaw

- The Yanomami Culture and Survival

- Facing Mount Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu by Kenyatta

- What Role Does Food Play in Cultural Identity?

- Islamic Civilization and Culture: The 7th Century

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 17). Non-Material and Material Culture. https://ivypanda.com/essays/non-material-and-material-culture/

"Non-Material and Material Culture." IvyPanda , 17 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/non-material-and-material-culture/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Non-Material and Material Culture'. 17 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Non-Material and Material Culture." November 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/non-material-and-material-culture/.

1. IvyPanda . "Non-Material and Material Culture." November 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/non-material-and-material-culture/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Non-Material and Material Culture." November 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/non-material-and-material-culture/.

Home — Essay Samples — Science — Language — Difference Between Material and Nonmaterial Culture

Difference Between Material and Nonmaterial Culture

- Categories: Language

About this sample

Words: 598 |

Published: Mar 20, 2024

Words: 598 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Material culture, nonmaterial culture, relationship between material and nonmaterial culture, implications for society.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Science

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 370 words

6 pages / 2692 words

3 pages / 1323 words

1 pages / 489 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Language

Giddens, Anthony. 'Functionalism.' In Introduction to Sociology. W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 'Manifesto of the Communist Party.' Marxists Internet Archive, 1848.Blumer, Herbert. 'Society as [...]

The English language holds a significant position in the global arena, serving as a means of communication across cultures, nationalities, and professions. Its importance cannot be overstated, as it has become the lingua franca [...]

The English language is widely regarded as the global lingua franca, serving as a common means of communication for people from diverse linguistic backgrounds. However, despite its widespread use, the English language presents a [...]

Vygotsky's theory of speech, also known as the sociocultural theory, has had a significant impact on the field of developmental psychology. This theory emphasizes the role of social interaction and cultural context in the [...]

George Orwell’s 1984 portrays a dystopian society whose values and freedoms have been marred through the manipulation of language and thus thought processes. Language has become a tool of mind control for the oppressive [...]

In today's visually saturated world, it is often said that a picture is worth a thousand words. However, in his article "Words Triumph Over Images," published in The New York Times in 2011, Errol Morris argues the opposite: that [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

What is Material Culture?

Material culture is a term used in archaeology and other anthropology-related fields to refer to all the corporeal, tangible objects that are created, used, kept and left behind by past and present cultures. Material culture refers to objects that are used, lived in, displayed and experienced; and the terms includes all the things people make, including tools, pottery, houses, furniture ...

Material culture

tural geography (a selective material culture bibli-ography is appended below). These developments and activities have been spontaneous and largely uncoordinated responses to a perceived scholarly need and opportunity. This essay attempts to de-fine material culture and considers the nature of the discipline. It makes no claim to be either the

Essay 1: Material Culture. Essay 1 focuses on the analysis of an object chosen from a pre-selected collection. The goal is to contextualize the object and use it as a starting point to discuss some of the larger topics covered in the course.

Material culture is a study carried out through objects (artefacts) to see social markers, historical traces, social knowledge, and the identity of a particular nation or society.

Material culture are physical objects, resources, and spaces that people use to define their culture. This can include furniture, clothing, toys, tools, buildings, and architecture. ... they signal the need to decenter the social within social anthropology in order to make room for the material." Each essay is a case study and the introduction ...

moments in material culture scholarship, and present research from around the world, focusing on multiple material and digital media that show the scope and breadth of this exciting Þeld. Written in an easy-to-read style, it is essential reading for students, researchers, and professionals with an interest in mate-rial culture. LU ANN DE CUNZO

In this way, the study of material culture is a useful venue to help us comprehend cultures and societies (Glacken 1976). Fortunately, making sense of material culture can be approached by a variety of theoretical frameworks, each one adding value through particular insights and epistemologies. This essay points to conceptual or theoretical ...

Stones, Bones, and the Sacred is a collection of 16 essays on material culture and ancient religion in honor of Dennis E. Smith edited by Alan H. Cadwallader. In the first essay, Hal E. Taussig presents a general evaluation of Dennis E. Smith's scholarship and the final essay is written by Smith himself as a response to the essays. In general ...

Understanding Material Culture is an extension of Woodward's earlier work on the narrative presented by material culture. The book aims at expanding this topic and at the same time generalizing the information on material culture. The author achieves this mainly by providing definitions, adding information on such topics as theoretical ...

Eighteen essays discuss the use of artifacts and material culture evidence in broadening historical understanding of the past. Contributors come from a wide array of backgrounds, including art history, anthropology, archaeology, and the history of technology, and the artifacts examined range from Chinese bronzes to the cultural landscape of eighteenth-century English gardens and from New ...

An Essay on Material Culture Some Concluding Reflections Kristian Kristiansen The concept of Culture has been a battlefield between different theoretical regimes in the history of anthropology and archa-eology. Such debates are therefore also a historical barometer of the health and polemic vigour of the disciplines. ...

Colonial American communities developed far from the metropole, along the western frontier of Britain's empire. In such an isolated setting, objects of material culture helped their owners generate new social and political identities. On May 8, 1736, a Boston merchant sold to Andrew Bordman " one large black framed looking glass, one ...

Material Culture - Objects. This essay explores ways to use material objects in the study of history. "Material objects" include items with physical substance. They are primarily shaped or produced by human action, though objects created by nature can also play an important role in the history of human societies.

51 Material Culture Examples (2024)

Material Culture In Anthropology. 962 Words4 Pages. "Recent thinking in anthropology defines material culture as an 'event' or 'effect' that emerges from the performance of material things, bodies and spaces" (Kim 2017:194). Material culture shapes the way that we live today and has a huge role in our social lives.

The Material culture is one of the most popular assignments among students' documents. If you are stuck with writing or missing ideas, scroll down and find inspiration in the best samples. Material culture is quite a rare and popular topic for writing an essay, but it certainly is in our database.

The essays in this new collection examine just that. The contributors pose not only a historical, pragmatic use for the items, but also delve into more imaginative aspects of what defines us as Americans. Both the lighter and the telephone are investigated, as well as how the lava lamp represents sixties counterculture and containment.

Although there are valid definitions of material cultures by various historical scholars, Brown defines it as a "study through artifacts of the beliefs- values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions- of a particular community of society at given time" (1). Get a custom essay on Material Culture: Pottery. 185 writers online.

Material culture is focused on resources, objects, and spaces that are significant to and define a larger culture. This can refer to locations such as cities, temples, or even workplaces as much as to tools and goods. On the other hand, non-material culture is entirely concerned with non-physical ideas and values that are inherent to cultures ...

In conclusion, material and nonmaterial culture are two distinct but interconnected aspects of human society. Material culture encompasses the physical objects and artifacts of a society, while nonmaterial culture includes the intangible beliefs, values, and practices that shape human behavior and interaction. By understanding the relationship between these two aspects of culture, we can gain ...

Having a car means that I accept having to pay out for insurances, taxes, etc. in order to use it on public roads. MATERIAL AND NONMATERIAL CULTURE 3. 2. Glamorous ball-gown; I value the appropriateness of wearing such a dress for the right occasion, such as a wedding, rather than to the supermarket. 3.