- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Research Paper vs. Research Article: What’s the Difference?

Research papers and research articles are two different forms of academic writing, with distinct characteristics. Although they share some similarities in terms of format and purpose, there are important distinctions between the two types that should be understood by students who wish to write either form effectively. This article will explain the differences between a research paper and a research article, outlining their unique features and applications. Furthermore, it will offer guidance on how best to approach each type when crafting an effective piece for scholarly consumption.

I. Introduction to Research Paper vs. Research Article

Ii. defining a research paper and a research article, iii. comparative analysis of structure, content, and writing styles between the two types of scholarly documents, iv. pros & cons of conducting either a formal or an informal study, v. concluding remarks: how to choose between the different approaches when completing academic assignments, vi. limitations in comparing these texts as distinct forms of scholarly outputs, vii. future directions for understanding similarities & differences across all kinds of academic writings.

Research Paper vs. Research Article

The academic world is full of a variety of different writing styles, each with its own unique purpose and goals. Two particularly important forms are the research paper and the research article. Each has their own distinct features that make them uniquely suited to certain tasks within academia – let’s take a closer look at what sets them apart from one another!

A research paper , as you might expect, presents in-depth analysis on an issue or topic using evidence gathered through primary sources such as field work, laboratory experiments, surveys, interviews etc., whereas a research article , typically published in scholarly journals or online publications like websites & blogs addresses specific findings derived from secondary sources like books or other papers related to said subject matter. The former requires more effort & dedication from the author due to it being time consuming & involving careful structuring along with rigorous citation format adherence; while the latter focuses mainly on providing succinct yet comprehensive overviews regarding topics which have already been extensively discussed by experts in depth previously elsewhere – taking into account present day developments/breakthroughs if necessary before finally offering opinionated conclusions pertaining to said subjects.

Exploring the Characteristics of a Research Paper and Article

- Research paper:

- Research article:

A research paper is an extended form of writing that presents and supports an argument on a particular topic. It provides evidence for the opinion or idea in the form of facts, data, analysis, opinions from authorities in specific fields etc. The objective is to make original claims based on careful evaluation of information available on a given subject. It requires significant effort as one needs to be able to distill complex topics into concisely articulated points that are supported by solid evidence.

On the other hand, a research article is usually written for publication either online or printed through journals or magazines. These articles have been peer-reviewed which means they follow certain academic standards established within their discipline while presenting factual conclusions related to ongoing debates and arguments raised by preceding works. They generally provide new insight into existing knowledge rather than build upon it using more primary sources such as surveys and experiments conducted independently by authors themselves.

Comparison of Structure, Content and Writing Styles between Research Papers and Articles For the purpose of scholarly communication, both research papers and articles play a vital role. Though there is no hard-and-fast rule that distinguishes them from each other in terms of structure or content, they usually differ significantly in their style. In comparison to research papers, articles typically have a much smaller length requirement. They can range anywhere from 1 page to as many as 30 pages depending on the journal guidelines – making them more accessible for readers who are seeking concise summaries with quick insights into topics. On the contrary, research papers tend to be longer documents that delve deeper into an issue by providing extensive background information; detailed analysis; arguments bolstered by sources such as peer-reviewed journals or interviews; conclusion sections tying up any loose ends etc.

- Research Papers: Longer documents which provide extensive coverage about an issue.

- Articles: Short pieces covering high level overviews without going too deep.

When it comes down to writing styles used for these two types of documents – Authors generally follow formal academic language while creating research paper whereas article writers tend to use more casual tones in order to appeal wider audience groups. Additionally authors will often adopt conversational elements like anecdotes when crafting articles so that readers can get better understanding about specific points being discussed within context.

Formal vs. Informal Study: A Critical Analysis The choice between conducting a formal or informal study may be difficult for researchers due to the advantages and drawbacks of each approach. Depending on their research topic, scientists must carefully weigh up the pros and cons before deciding which course of action is most suitable for them.

A formal study , as conducted in many research papers and articles, often requires more time-consuming effort from researchers than an informal one because it involves using specific methodologies such as surveys, interviews, experiments etc., gathering quantitative data that needs to be statistically analyzed by employing reliable statistical methods. On the other hand, a formal investigation allows researchers to obtain objective information from well-defined populations about predetermined variables through systematic procedures that can yield precise results with larger external validity – making it possible to make generalizations beyond those studied in this particular case.

Conversely, an informal study , also known as participant observation or field work requires less structured approaches where collecting qualitative data is usually achieved via conversations with informants instead of strict instrumentations; thus allowing greater interaction between researcher and subjects resulting in increased understanding of contextually situated phenomena within its natural setting rather than artificially created ones used in laboratories’ studies – leading to deeper insights into complex social processes . Also noteworthy is its lower financial cost when compared against highly expensive equipment needed for undertaking large scale scientific investigations.. However despite yielding valuable first person accounts which might not have been obtained elsewhere , such observations are sometimes criticized due challenges related accuracy given reliance on subjective interpretations while generating evidence without significant use of control variables .

Selecting the Optimal Approach for Academic Assignments When it comes to completing academic assignments, there are various approaches one can take. In order to ensure success and optimal results, it is important that students consider all of their options carefully before making a choice.

Research papers often require extensive research and careful consideration when selecting an approach. Using primary sources such as books or peer-reviewed articles may be more reliable in comparison to secondary sources such as websites or blogs which are usually less credible due to lack of credibility checks by professionals within the field. Additionally, data analysis can help strengthen arguments while also adding clarity to any work produced during the course of completion; however, understanding how best utilize this analytical tool effectively requires additional practice and experience on behalf of the student undertaking it. For research articles, detailed knowledge about particular topics may lead towards better outcomes but general familiarity with content areas is sufficient enough for success here too. The key lies in being able identify appropriate methods quickly through use critical thinking skills coupled with clear objectives pertaining specifically each assignment itself at hand prior its execution – this way mistakes are avoided thus delivering quality results each time..

Comparative Analyses of Scholarly Outputs

- Scholarly output, such as research papers and articles, are subject to scrutiny when attempting to make comparisons.

- Due to the differences between these two types of outputs, it can be difficult or impossible to achieve a true comparison.

Comparing scholarly outputs is not always possible due to their distinct forms. Research papers typically have more depth than an article on the same topic which may mean that even though both documents might discuss similar topics in some aspects they will differ greatly in others. Furthermore, the format of each type of document contributes further complexities; for example, a research paper is often much longer and requires extensive background information before any conclusions can be drawn while articles tend towards presenting results with little room left for interpretation. The style used by authors also adds difficulty; many times research papers include complex jargon necessary for understanding specific points whereas an article strives for simplicity so its target audience can comprehend all material without excessive effort. These limitations prevent proper analysis from being done since one piece could provide certain details while another provides only bits related thereto leading readers into confusion if attempting to compare them directly despite intentions otherwise. It then becomes clear that academic pieces should instead remain separate entities rather than compared against each other since doing so would lead only too frustration given current constraints therein found.

Exploring the Similarities and Differences Between Academic Writings

As our understanding of academic writings continues to evolve, so too must our appreciation for both their similarities and differences. From research papers to research articles, it is important to consider how each one contributes unique insight into a given topic or issue.

The research paper and research article may look similar on the surface, but upon closer inspection one can see significant differences in their format, purpose, and audience. The key distinctions between these two forms of written work are scope of content covered, type of analysis used to draw conclusions or develop knowledge from data or evidence presented, and intended readership. Ultimately, understanding the essential characteristics that distinguish a research paper from a research article is beneficial for anyone who produces such texts as it will help them craft an effective product that aligns with its desired purposes.

- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

- Richard G. Trefry Library

Q. What's the difference between a research article (or research study) and a review article?

- Course-Specific

- Textbooks & Course Materials

- Tutoring & Classroom Help

- Writing & Citing

- 44 Articles & Journals

- 11 Capstone/Thesis/Dissertation Research

- 37 Databases

- 56 Information Literacy

- 9 Interlibrary Loan

- 9 Need help getting started?

- 22 Technical Help

Answered By: Priscilla Coulter Last Updated: Jul 29, 2022 Views: 230880

A research paper is a primary source ...that is, it reports the methods and results of an original study performed by the authors . The kind of study may vary (it could have been an experiment, survey, interview, etc.), but in all cases, raw data have been collected and analyzed by the authors , and conclusions drawn from the results of that analysis.

Research papers follow a particular format. Look for:

- A brief introduction will often include a review of the existing literature on the topic studied, and explain the rationale of the author's study. This is important because it demonstrates that the authors are aware of existing studies, and are planning to contribute to this existing body of research in a meaningful way (that is, they're not just doing what others have already done).

- A methods section, where authors describe how they collected and analyzed data. Statistical analyses are included. This section is quite detailed, as it's important that other researchers be able to verify and/or replicate these methods.

- A results section describes the outcomes of the data analysis. Charts and graphs illustrating the results are typically included.

- In the discussion , authors will explain their interpretation of their results and theorize on their importance to existing and future research.

- References or works cited are always included. These are the articles and books that the authors drew upon to plan their study and to support their discussion.

You can use the library's article databases to search for research articles:

- A research article will nearly always be published in a peer-reviewed journal; click here for instructions on limiting your searches to peer-reviewed articles.

- If you have a particular type of study in mind, you can include keywords to describe it in your search . For instance, if you would like to see studies that used surveys to collect data, you can add "survey" to your topic in the database's search box. See this example search in our EBSCO databases: " bullying and survey ".

- Several of our databases have special limiting options that allow you to select specific methodologies. See, for instance, the " Methodology " box in ProQuest's PsycARTICLES Advanced Search (scroll down a bit to see it). It includes options like "Empirical Study" and "Qualitative Study", among many others.

A review article is a secondary source ...it is written about other articles, and does not report original research of its own. Review articles are very important, as they draw upon the articles that they review to suggest new research directions, to strengthen support for existing theories and/or identify patterns among exising research studies. For student researchers, review articles provide a great overview of the existing literature on a topic. If you find a literature review that fits your topic, take a look at its references/works cited list for leads on other relevant articles and books!

You can use the library's article databases to find literature reviews as well! Click here for tips.

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 7 No 0

Related Topics

- Articles & Journals

- Information Literacy

Need personalized help? Librarians are available 365 days/nights per year! See our schedule.

Learn more about how librarians can help you succeed.

Difference Between Research Article and Research Paper

This article will discuss both writings formats and discuss Difference Between Research Article and Research Paper.

It’s likely that you will hear a lot about research papers and research articles, whether you are a student at a college or university or working towards a profession.

Both types of writing are common techniques used by educators and businesses to get feedback from coworkers and students on a topic or subject. One must understand each form and how people use it in to differentiate between the two types of writing.

The majority of assignments require a specific working framework and exploration because research is seen as a movement that has gained substantial popularity in the academic world. The research papers and research articles serve as a compilation that is required for the essential certification, as well as for comprehending and demonstrating outstanding aptitude for research and study.

The research articles and research papers are the parts of the writing which need investigation, critical analysis, insight, and presentation of few particular skills from the scientists and students. When the teacher assigns the class to write a research paper, it actually overwhelms the students. Research articles and research papers have many similarities, which causes students to become confused. Here, we shall highlight the fundamental differences between the two terms.

- Table of Contents

Research Article

What will a researcher or scientist do after they have found the answer to a question or made a discovery they wish to share with the world?

Well, writing a research paper is the ideal way to share your knowledge and expertise with the world. An authentic study topic, together with pertinent findings and data, are all included in a research article. It is published by renowned scientific journals that are concerned with the field of work to which your study relates. You can refer to a research paper as a writing or a paper that informs readers of a new line of enquiry or a discovery that is supported by evidence.

A research article gets a touch of building with original research, pertinent data, and disclosures. It is a particular study article that informs readers who are worried about the finding being broken or who are looking for information to support the finding.

A research article, according to Simon Fraser University, is a piece of writing that is written about a specific topic. A research article written by an expert in a certain field is frequently written by another expert in the same field. Peer reviews are another term for this kind of writing.

A research article is a concise piece of writing on a certain subject that is typically published in issues or periodicals. Current research on the topic, including new advances, analyses of a technique or item, and brief studies previewing concepts are frequently included.

A Research article may contain details on the most recent techniques or methods in a certain industry. Peer reviews, case studies, scholarly articles, scientific, and social science articles are further types of research articles. A journal publishes research articles only after conducting a substantial amount of research in the related field. Research articles are classified as primary literature or review articles in the Publication Manual.

Purpose of Research Article

A research article may be a significant source, making it a valuable resource for creating the thesis for the relevant topic. It includes a report on the methods and results of the researchers’ original research.

The type of study conducted may vary (it may take the form of an experiment, interview, meeting, etc.), but in every instance, the researcher gathers the raw data, breaks it down, and then draws conclusions based on the investigations carried out throughout the study.

As a result, each project is different, and regardless of the language you use, your article must be able to effectively convey all of your research and findings.

Format of Research Article

Create a title that is specific enough to summarize the entire article’s content while being understandable. The article’s title ought to be relevant for the target audience.

Article titles, such as “ Effect of Alcohol on Academic Performance ,” typically describe the article’s topic matter.

The initial author of an article is typically considered to be a researcher who conducted the research and produced the paper.

Other people have made significant contributions in writing the research article that is published, and as a result, they are considered authors. Before listing your mentor’s name as a co-author or author, you can get their permission.

It gives readers a sneak peek at the entire study. By allowing other scientists to quickly scan a sizable portion of the scientific literature, they can then choose which research articles they want to study in-depth. A research article’s abstract should be a little less technical than the article’s content.

An abstract must be one paragraph long (between 100 and 250 words), summarizing the objective, methods, results, and conclusion of the study.

Giving all the information in a single paragraph is not very simple. Start by including the overview of what you feel is vital to mention, and then gradually reduce the length by omitting the unimportant details while keeping the crucial information.

In your abstract, avoid using citations or abbreviations. Without any footnotes, it must be readable.

→INTRODUCTION

- What is the objective of your research?

- What are the research questions?

- Which problem your research has addressed?

In order for your reader to comprehend the aim of the topic and what makes it so intriguing, this section of the essay provides a synopsis of the relevant literature.

A two- to four-paragraph introduction is appropriate. Finish it up with a statement that clarifies the question.

This section describes how you will respond to your question. Here, there must be enough information to let the reader understand the research.

Look for related articles that were published before yours to get a sense of this section of the article.

If you have a complicated method, it can be beneficial to include diagrams, flowcharts, or tables to describe how you use it.

Include the relevant moral considerations as well.

Do they permit participation if you use human subjects?

What pain-reduction measures would you adopt if you used animals?

Read More: Population vs Sample | Examples

This part is a presentation of the findings you came to. If necessary, use graphs and charts; nevertheless, this part should also provide a summary of the key findings.

Don’t discuss the outcomes or speculate as to why anything occurred. None of the information you discovered from research needs to be mentioned. Employ appropriate techniques to explain the data. Don’t try to distort your facts to make it appear that you have accomplished more than you have.

→TABLES AND GRAPHS

Instead of just stating, “Here are the results that are drawn,” if you are presenting the data in the form of graphs or tables, explain a little bit about what the graphs or tables indicate, such as, “This graph or table represents the activity of enzyme at different temperatures.”

→DISCUSSION

Mention the most significant findings in discussion. Try to avoid just restating those from the results section.

- How are your findings related to your question?

- Do your data give support to the proposed theory?

- Are the findings in line with the areas you looked at for the article?

Provide reasons if the results are surprising.

- Is there another way to understand the outcomes?

- What additional study is necessary to respond to your question?

- How do your findings relate to the larger context?

→ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The acknowledgements section is optional. You can express gratitude to anyone who helped you during an experiment or who provided any other substantial assistance, such as discussing your methodology or offering suggestions on a manuscript.

→REFERENCES

There are only a handful possible arrangements for this section. You could, for instance, cite the text at main points. Alternatively, include a list of references in alphabetical order at the end of the article.

Research Paper

When referring to research papers, Dr. Jane Simonsen, a history professor, once said, “The work and design are your own, but you can’t do it without relying on the efforts and wisdom of others.”

Simonsen’s assumption is accurate. A research paper is a type of writing that is typically utilized in academic settings by college or university students who have been asked to look into and research a topic before coming to their conclusion.

The use of data from reliable sources to back up the student’s conclusions is both encouraged and frequently necessary. The length of research paper is affected by the complexity of the topic. A standard research paper can be anywhere from 50 to 200 pages long.

After gathering all necessary information from sources, a student’s work will be organized into the structure. Teachers frequently use this method to help students develop a balance in their writing abilities while promoting structural discipline and standard formatting.

According to A Research Guide for Students, research papers also use the subject’s original information, and after the student has gathered the data from the investigative stage, they are summarized with a clear and simple analysis and disposition, or thesis. In fact, the thesis statement for most research papers comes from the assigned topic.

Purpose of Research Paper

Writing an outstanding research paper is not merely a non-related task that you must complete in order to pass the examination. It is a task that teaches you a lot including:

- How to research a specific topic?

- How to fully express your understanding, conclusions, and analysis to a reader?

The more you focus on paper quality while in college or university, the more you’ll need to practice writing and research skills, which will enhance both your analytical and writing abilities. Nevertheless, if you perform poorly, the competition will be weaker, and it’s more possible that you’ll look back on this period and feel regret in the future for having missed your chance. Gaining the advantages of having the best writing abilities is crucial for this reason.

Format for Research Papers

There is a set format for research papers.

A brief introduction that often includes an overview of recent literature on the given topic researched and explains the author’s motivation for undertaking the research. This is significant because it indicates that the authors are aware of the current body of research and intend to contribute to it appropriately and they are not only conducting research on the topics that other people have already conducted.

The authors describe in detail how they can gather and evaluate the data in this section. The statistical analysis is also provided. The method section is very thorough since it is crucial for other researchers to be able to verify or employ the same methods.

Read More: Reliability vs Validity | Examples

The findings of your analysis can be discussed in this section. To demonstrate your findings, use graphs and charts.

Here, the authors provide an explanation of how the results were interpreted as well as a theory outlining the significance of current and future research.

References and citations can be added here. References are genuine books and articles that authors use to conduct their research and support their arguments.

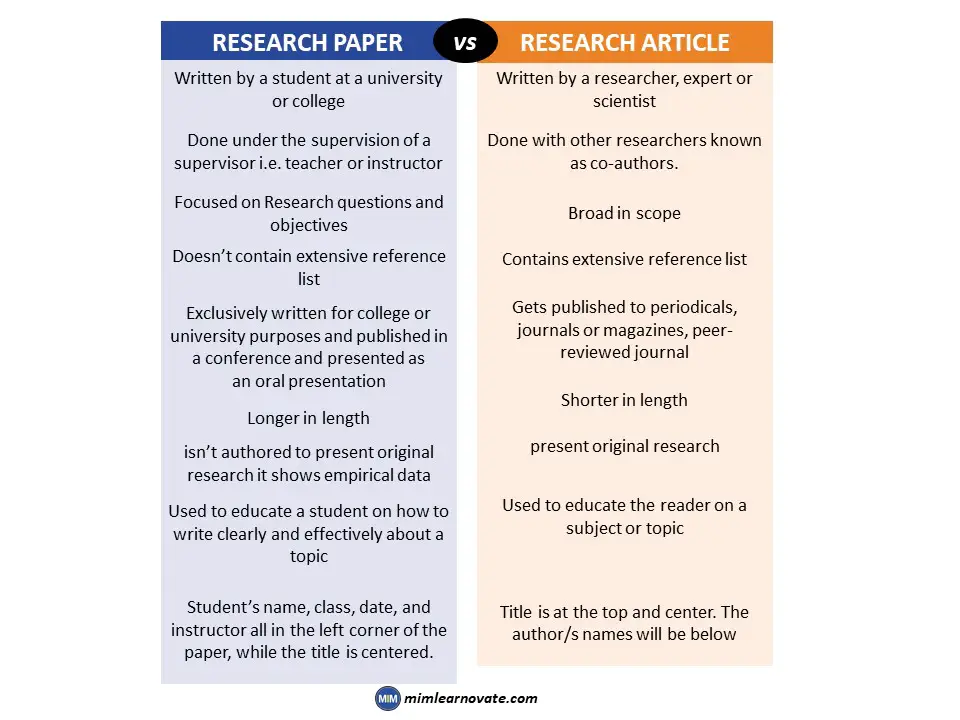

Difference Between Research Paper and Research Article

1- A student at a university or college generally writes research papers as part of their coursework. A research paper is completed for review by a teacher or instructor. Whereas, a research article is a piece of writing that has recently undergone research or review by a professional in the field.

2- The number of references used also differs slightly. A reader can typically anticipate finding a lengthy bibliography in a research article, whereas a research paper won’t call for a reference list so extensive.

3- A research paper isn’t published in any publication unless it’s a guideline on how to write one, whereas a research article is submitted to periodicals, magazines or peer-reviewed journal.

4- A research article examines a potential or existing concept and discusses its effects. A thesis may be provided in a research paper, although it will not be as detailed.

5- Both differs in terms of formatting and length. A Longer in length whereas research article might be 15 pages long, but it’s not always the case. The structure used to convey the research will be different from that of a research paper, which might use double spacing and indenting. In contrast to a journal article, which explains its original findings to the reader, a research paper is written to demonstrate empirical data rather than to provide original research.

6- The title of the research paper will be centered, and the student’s name, class, date, and teacher will be in the left corner. Whereas the title will be top and centre in the research article. The names of the author(s) are listed below.

7- Research paper is for writing practice, while the research article is a specific practice for other practitioners. A research paper is more utilized to teach students how to write clearly and effectively on a subject, whereas the research article is designed to educate the reader on a subject or topic.

Other articles

Please read through some of our other articles with examples and explanations if you’d like to learn more about research methodology.

Comparision

- Basic and Applied Research

- Cross-Sectional vs Longitudinal Studies

- Survey vs Questionnaire

- Open Ended vs Closed Ended Questions

- Experimental and Non-Experimental Research

- Inductive vs Deductive Approach

- Null and Alternative Hypothesis

- Reliability vs Validity

- Population vs Sample

- Conceptual Framework and Theoretical Framework

- Bibliography and Reference

- Stratified vs Cluster Sampling

- Sampling Error vs Sampling Bias

- Internal Validity vs External Validity

- Full-Scale, Laboratory-Scale and Pilot-Scale Studies

- Plagiarism and Paraphrasing

- Research Methodology Vs. Research Method

- Mediator and Moderator

- Type I vs Type II error

- Descriptive and Inferential Statistics

- Microsoft Excel and SPSS

- Parametric and Non-Parametric Test

- Independent vs. Dependent Variable – MIM Learnovate

- Research Article and Research Paper

- Proposition and Hypothesis

- Principal Component Analysis and Partial Least Squares

- Academic Research vs Industry Research

- Clinical Research vs Lab Research

- Research Lab and Hospital Lab

- Thesis Statement and Research Question

- Quantitative Researchers vs. Quantitative Traders

- Premise, Hypothesis and Supposition

- Survey Vs Experiment

- Hypothesis and Theory

- Independent vs. Dependent Variable

- APA vs. MLA

- Ghost Authorship vs. Gift Authorship

- Research Methods

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Case Study Research

- Survey Research

- Conclusive Research

- Descriptive Research

- Cross-Sectional Research

- Theoretical Framework

- Conceptual Framework

- Triangulation

- Grounded Theory

- Quasi-Experimental Design

- Mixed Method

- Correlational Research

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Stratified Sampling

- Ethnography

- Ghost Authorship

- Secondary Data Collection

- Primary Data Collection

- Ex-Post-Facto

- Dissertation Topic

- Thesis Statement

- Research Proposal

- Research Questions

- Research Problem

- Research Gap

- Types of Research Gaps

- Operationalization of Variables

- Literature Review

- Research Hypothesis

- Questionnaire

- Reliability

- Measurement of Scale

- Sampling Techniques

- Acknowledgements

- PLS-SEM model

- Principal Components Analysis

- Multivariate Analysis

- Friedman Test

- Chi-Square Test (Χ²)

- Effect Size

- Directional vs. Non-Directional Hypothesis

Related Posts

9 qualitative research designs and research methods, tips to increase your journal citation score, types of research quiz, difference between cohort study and case control study, convenience sampling: method and examples, difference between cohort and panel study, why is a pilot study important in research, panel survey: definition with examples, what is panel study, what is a cohort study | definition & examples, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Journal Article vs Research Paper: Difference and Comparison

A journal article presents original research findings in a concise format, focusing on a specific topic within a broader field. It undergoes peer review before publication, ensuring quality and validity. On the other hand, a research paper is a comprehensive document that may include multiple experiments, analyses, and discussions, aimed at contributing to the advancement of scientific knowledge.

Key Takeaways A journal article is a shorter scholarly writing published in a specific academic journal. A research paper is a more extended, comprehensive academic writing presenting original research. Journal articles are more focused and present specific findings, while research papers are broader and present a more comprehensive study.

Journal Article vs Research Paper

A journal article is a piece of published work that presents the research findings and may include analysis, remark, or discussion. A research paper is a detailed account of the research that may be published or unpublished and includes an introduction, literature review, methods, results, and conclusion.

Comparison Table

What is journal article.

A journal article is a scholarly publication that presents the findings of original research, analysis, or review within a particular academic field. These articles serve as fundamental units of scholarly communication, disseminating new knowledge, theories, and insights to the academic community and beyond. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

Content and Structure

1 Abstract: A journal article begins with an abstract, a concise summary of the study’s objectives, methods, results, and conclusions. The abstract provides readers with a quick overview of the article’s content and findings.

2 Introduction: Following the abstract, the introduction sets the context for the study by reviewing relevant literature, identifying gaps or controversies in existing knowledge, and stating the research objectives or hypotheses.

3 Methods: The methods section outlines the procedures, materials, and techniques used to conduct the study. It should provide sufficient detail to enable replication of the experiment or analysis by other researchers.

4 Results: This section presents the findings of the study, using tables, figures, or graphs to illustrate data. Authors describe the results objectively, without interpretation or speculation.

5 Discussion: In the discussion section, authors interpret the results in light of the study’s objectives and existing literature. They may address the implications of their findings, suggest future research directions, and discuss limitations or potential sources of bias.

6 Conclusion: The conclusion summarizes the main findings of the study and highlights their significance. It may also reiterate the study’s contribution to the field and offer final reflections or recommendations.

Peer Review Process:

1 Submission: Authors submit their articles to scholarly journals for publication consideration, adhering to the journal’s guidelines and formatting requirements.

2 Peer Review: Upon submission, the journal’s editor assigns the manuscript to peer reviewers—experts in the field—who evaluate the article’s quality, originality, methodology, and significance. Peer review helps ensure the rigor and credibility of the research.

3 Revision: Based on the reviewers’ feedback, authors may revise their article to address any concerns or criticisms raised. This iterative process of revision and reevaluation continues until the article meets the journal’s standards for publication.

4 Acceptance and Publication: If the article meets the journal’s criteria, it is accepted for publication and undergoes final editing and formatting. Once published, the article becomes part of the journal’s archive and is accessible to readers worldwide.

What is Research Paper?

A research paper is a comprehensive document that presents the findings, analysis, and interpretations of original research conducted by the author(s) within a specific academic discipline. These papers serve as a means for scholars to contribute new knowledge, theories, and insights to their respective fields. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

1. Content and Structure

1 Introduction: The introduction of a research paper provides background information on the topic, reviews relevant literature, and outlines the research objectives or hypotheses. It establishes the context for the study and justifies its significance.

2 Methods: The methods section describes the procedures, materials, and techniques employed in the research. It should provide sufficient detail to enable other researchers to replicate the study and verify its results.

3 Results: This section presents the empirical findings of the research, using tables, figures, or graphs to illustrate data. Authors report their observations or measurements objectively, without interpretation or speculation.

4 Discussion: In the discussion section, authors interpret the results in light of the research questions or hypotheses, comparing them to previous studies and addressing their implications. They may also explore alternative explanations, limitations of the study, and avenues for future research.

5 Conclusion: The conclusion summarizes the main findings of the research and highlights their significance. It may reiterate the study’s contribution to the field, offer final reflections, and suggest directions for further inquiry.

Characteristics and Scope

1 Original Research: Unlike review papers or essays, research papers are based on original research conducted by the authors. They contribute new data, insights, or interpretations to the academic discourse.

2 Rigorous Methodology: Research papers adhere to rigorous scientific or scholarly methodologies, employing systematic approaches to data collection, analysis, and interpretation. They prioritize objectivity, validity, and reliability in their findings.

3 Length and Complexity: Research papers vary in length and complexity, depending on the scope of the study and the requirements of the target publication venue. They may range from concise reports of preliminary findings to comprehensive analyses of multi-year research projects.

4 Contribution to Knowledge: Research papers aim to advance knowledge within their respective fields by addressing research gaps, testing hypotheses, or generating new theories. They contribute to the cumulative growth of scholarship through the dissemination of original research findings.

Main Differences Between Journal Article and Research Paper

- Journal articles focus on a specific aspect or finding within a broader topic.

- Research papers provide a comprehensive analysis of a research project, including multiple experiments, analyses, and discussions.

- Journal articles are concise, containing essential findings, methods, and interpretations in a limited space.

- Research papers tend to be longer and more detailed, offering exhaustive exploration of the research topic, methodology, results, and implications.

- Journal articles undergo peer review by experts in the field before publication, ensuring quality and validity.

- Research papers may or may not undergo formal peer review, depending on the publication venue or academic requirements.

- Journal articles present findings objectively, without extensive interpretation or speculation.

- Research papers include in-depth interpretation of results, discussion of implications, and exploration of potential limitations or biases.

- Journal articles contribute to the scholarly conversation by presenting new findings, analyses, or reviews within a specific topic area.

- Research papers advance knowledge within a field by offering comprehensive analyses, testing hypotheses, or generating new theories through original research.

- https://gssrr.org/index.php/gssrr/How-to-Publish-Research-Paper

- https://www.springer.com/gp/authors-editors/journal-author/types-of-journal-manuscripts/1356

- https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/index.html

Last Updated : 05 March, 2024

I’ve put so much effort writing this blog post to provide value to you. It’ll be very helpful for me, if you consider sharing it on social media or with your friends/family. SHARING IS ♥️

Emma Smith holds an MA degree in English from Irvine Valley College. She has been a Journalist since 2002, writing articles on the English language, Sports, and Law. Read more about me on her bio page .

Similar Reads

- A Journal vs An Article: Difference and Comparison

- Wax Paper vs Baking Paper: Difference and Comparison

- Parchment Paper vs Wax Paper: Difference and Comparison

- Research Method vs Research Methodology: Difference and Comparison

- Marketing Research vs Market Research: Difference and Comparison

Share this post!

21 thoughts on “journal article vs research paper: difference and comparison”.

The characteristics of a journal article outlined in the article shed light on the structured nature of these scholarly publications. It’s important to understand the components that make up a journal article to effectively communicate research findings.

Agreed, knowing the key components of a journal article is essential for researchers aiming to publish their work in reputable academic journals.

Absolutely, the detailed breakdown of the characteristics of a journal article provides valuable insights for aspiring authors.

This article provides a clear and concise comparison between journal articles and research papers. It’s informative and well-structured. I appreciate the detailed explanation of the characteristics of each type of publication.

I agree, the article provides a comprehensive overview of the differences between journal articles and research papers. It’s a valuable resource for researchers and academics.

The characteristics of a journal article and a research paper are clearly delineated in the article, providing an insightful comparison between the two types of scholarly publications.

Absolutely, the article offers a comprehensive comparison that highlights the unique features of journal articles and research papers.

The article effectively differentiates between journal articles and research papers, offering a comprehensive understanding of the distinct characteristics and purposes of each type of scholarly publication.

I concur, the article serves as an illuminating guide for researchers and scholars navigating the intricacies of academic writing and publication.

The article offers a thorough understanding of the significance of journal articles and research papers in the academic and professional spheres. It serves as a valuable resource for individuals engaged in scholarly writing and research.

I find the comparison table provided in the article particularly helpful. It offers a quick reference for distinguishing between journal articles and research papers based on publication outlet, content, target audience, peer review, length, structure, emphasis, and impact.

Yes, the comparison table is a useful tool for researchers to understand the key differences between journal articles and research papers at a glance.

The comparison table and detailed explanations in the article provide a nuanced understanding of the unique features of journal articles and research papers, making it a valuable resource for the academic community.

Absolutely, the article offers a comprehensive analysis that elucidates the differences and similarities between journal articles and research papers.

The distinction between journal articles and research papers is crucial for academic writing. This article does a great job of highlighting those differences and their respective characteristics.

Absolutely, understanding the nuances between these two types of publications is essential for academic and scholarly work. This article does an excellent job of breaking it down.

The structure of a research paper outlined in the article serves as a helpful guide for researchers looking to compose comprehensive and well-organized scholarly documents. It offers a clear framework for presenting original research findings.

I found the breakdown of the structure of a research paper to be particularly enlightening. It offers a roadmap for researchers to follow when crafting their academic work.

Yes, understanding the structure of a research paper is essential for effectively communicating the results of a study. This article provides a detailed overview of what to include in a research paper.

The detailed explanation of the structure and content of a journal article and a research paper is beneficial for researchers seeking to refine their academic writing skills and publish their work.

Indeed, the article provides valuable insights into the components and organization of journal articles and research papers, aiding researchers in producing high-quality scholarly publications.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to save this article for later? Click the heart in the bottom right corner to save to your own articles box!

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

White papers, working papers, preprints, journal articles: What’s the difference?

In this updated piece, we explain the most common types of research papers journalists will encounter, noting their strengths and weaknesses.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource February 25, 2022

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/media/working-papers-research-articles/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

This tip sheet, originally published in May 2018, has been updated to include preprint research, a type of research featured often in news coverage of the coronavirus pandemic.

Journalists rely most often on four types of research in their work. White papers, working papers, preprints and peer-reviewed journal articles.

How are they different? And which is best?

Below, we explain each, pointing out its strengths and weaknesses. As always, we urge journalists to use care in selecting any research to ground their coverage and fact-check claims.

Peer-reviewed article

Peer-reviewed research — the kind that appears in academic journals and that we highlight here at The Journalist’s Resource — has undergone a detailed critique by scholars with expertise in the field. While peer-reviewed research is generally the most reliable, journalists should keep in mind that publication in a prestigious journal is no guarantee of quality and that no single university or research organization always does the best research on a given topic.

It is safe to assume, however, that articles published in top-tier journals have been reviewed and given a stamp of approval by a number of accomplished scholars. For journalists who are uncertain, we’ve put together a list of 13 questions to ask to gauge the quality of a research article.

Keep in mind that not everything that appears in a scholarly journal has been peer reviewed. Journals publish various types of content, including book reviews, editorials, letters to the editor and, sometimes, even poetry.

Working paper

This broad category describes research papers that have not been peer reviewed or published in a journal. Working papers can be in various stages of completion. One might be ready for publication in a prestigious journal while another requires significant editing and other changes that could actually alter its main findings. Sometimes, working paper findings are so preliminary, authors will advise against citing their work .

Even so, working papers are a great way for journalists to gain access to new research quickly. The peer-review and publication process can take months to a year or longer, which means that by the time studies get published, their findings are sometimes not as useful or the data are old.

In choosing working papers, journalists should communicate with scholars about the progress of their research and how confident they are in their findings. It’s a good idea to seek corroboration from peer-reviewed research and to ask other researchers for help assessing a study.

A preprint is similar to a working paper in that it has not been vetted through a formal peer-review process. However, preprints tend to be more complete . Also, preprints submitted to public servers such as the Social Science Research Network and the health sciences server medRxiv get a cursory screening before they’re published online for public view.

Preprints, like academic journal articles, are assigned a Digital Object Identifier , or DOI, and become a permanent part of the scientific record.

White paper

A white paper is a report, often compiled by government agencies, businesses and nonprofit organizations, that outlines an issue and often explores possible solutions to a problem. For example, in November 2021, the federal Office of Community Oriented Policing Services released a white paper looking at factors that help or hinder law enforcement recruitment of Black Americans. Earlier in the year, the Advanced Technology Academic Research Center published a white paper on the American Rescue Plan ‘s widespread implications for government agencies.

In the business world, white papers also are used for marketing purposes — to describe a new product or approach, for instance, or diagnose a problem.

While a white paper can help journalists get up to speed quickly on an issue, it’s important to note some white papers advocate a specific position or policy change. Some rely on incomplete research or research that has not been peer reviewed.

Looking for more guidance on writing about research? Check out our tip sheets on covering biomedical research preprints amid the coronavirus and what journalists should know about peer review .

The Journalist’s Resource would like to thank Matthew Baum , the Marvin Kalb professor of global communications and professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School, for his help preparing this tip sheet.

About The Author

Denise-Marie Ordway

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Published on June 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

When you start planning a research project, developing research questions and creating a research design , you will have to make various decisions about the type of research you want to do.

There are many ways to categorize different types of research. The words you use to describe your research depend on your discipline and field. In general, though, the form your research design takes will be shaped by:

- The type of knowledge you aim to produce

- The type of data you will collect and analyze

- The sampling methods , timescale and location of the research

This article takes a look at some common distinctions made between different types of research and outlines the key differences between them.

Table of contents

Types of research aims, types of research data, types of sampling, timescale, and location, other interesting articles.

The first thing to consider is what kind of knowledge your research aims to contribute.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The next thing to consider is what type of data you will collect. Each kind of data is associated with a range of specific research methods and procedures.

Finally, you have to consider three closely related questions: how will you select the subjects or participants of the research? When and how often will you collect data from your subjects? And where will the research take place?

Keep in mind that the methods that you choose bring with them different risk factors and types of research bias . Biases aren’t completely avoidable, but can heavily impact the validity and reliability of your findings if left unchecked.

Choosing between all these different research types is part of the process of creating your research design , which determines exactly how your research will be conducted. But the type of research is only the first step: next, you have to make more concrete decisions about your research methods and the details of the study.

Read more about creating a research design

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/types-of-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

- Health Sciences Research Strategies

- The research process

- Defining your topic and crafting your research question

- Identifying search terms from your question

- Broaden or narrow your search

- Research methods

- Find articles in health science databases

- Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Interlibrary loan

- Find background information

- Find books and ebooks

- Types of Sources

- How to distinguish between types of journal articles

- Components of a scholarly article, and things to consider when reading one

- Critically evaluating articles & other sources

- Evidence Based Practice Portal (opens a new guide) This link opens in a new window

- Literature reviews (opens a new guide) This link opens in a new window

- Annotated bibliographies

- Writing tools

- Citing sources (opens a new guide) This link opens in a new window

- Understanding & Avoiding Plagiarism (opens a new guide) This link opens in a new window

Contact me for research assistance

Distinguishing between different types of journal articles

When writing a paper or conducting academic research, you’ll come across many different types of sources, including periodical articles. Periodical articles can be comprised of news accounts, opinion, commentary, scholarly analysis, and/or reports of research findings. There are three main types of periodicals that you will encounter: scholarly/academic, trade, and popular. The chart below will help you identify which type of periodical your article comes from.

Text and chart adapted from the WSU University Libraries' How to Distinguish Between Types of Periodicals and Types of Periodicals guides

What makes information peer-reviewed vs. scholarly vs. non-scholarly? Which type of source should I use?

- What makes information peer-reviewed vs. scholarly vs. non-scholarly?

- Which type of source should I use?

There is a nuanced distinction between peer-review and scholarship, which typically doesn't matter when evaluating sources for possible citation in your own work. Peer-review is a process through which editors of a journal have other experts in the field evaluate articles submitted to the journal for possible publication. Different journals have different ways of defining an expert in the field. Scholarly works, by contrast have an editorial process, but this process does not involve expert peer-reviewers. Rather, one or more editors, who are themselves often highly decorated scholars in a field, evaluate submissions for possible publication. This editorial process can be more economically driven than a peer-review process, with a greater emphasis on marketing and selling the published material, but as a general rule this distinction is trivial with regard to evaluating information for possible citation in your own work.

What is perhaps a more salient way of thinking about the peer-review / scholarship distinction is to recognize that while peer-reviewed information is typically highly authoritative, and is generally considered "good" information, the absence of a peer-review process doesn't automatically make information "bad." More specifically, the only thing the absence of a peer-review process means is that information published in this manner is not peer-reviewed. Nothing more. Information that falls into this category is sometimes referred to as "non-scholarly" information -- but again, that doesn't mean this information is somehow necessarily problematic.

Where does that leave you in terms of deciding what type of information to use in producing your own work? That is a highly individual decision that you must make. The Which type of source should I use? tab in this box offers further guidance on answering this question, though it is important to be aware that many WSU instructors will only consider peer-reviewed sources to be acceptable in the coursework you turn in . You can ask your instructor for his or her thoughts on the types of sources s/he will accept in student work.

Image: Martin Grater. (2017, Nov. 1). Deep Thought. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/152721954@N05/24304490568/. Used under the Creative Commons License.

Your topic and research question or thesis statement will guide you on which resources are best. Sources can be defined as primary, secondary and tertiary levels away from an event or original idea. Researchers may want to start with tertiary or secondary source for background information. Learning more about a topic will help most researchers make better use of primary sources.

While articles from scholarly journals are often the most prominent of the sources you will consider incorporating into your coursework, they are not the only sources available to you. Which sources are most appropriate to your research is a direct consequence of they type of research question you decide to address. In other words, while most university-level papers will require you to reference scholarly sources, not all will. A student in an English course writing a paper analyzing Bob Dylan's lyrics, for example, may find an interview with Dylan published in Rolling Stone magazine a useful source to cite alongside other scholarly works of literary criticism.

The WSU University Libraries' What Sources Should I Use? handout, as well as the other sub-tabs under the Evaluating information section of this guide (which is indeed the section you are currently viewing) offer further guidance on understanding and identifying scholarly resources, and comparing them against different criteria to evaluate if they will be of value to your research. How many non-scholarly works (if any) you are at liberty to cite alongside scholarly ones is often a question to ask of your professor. Some may not want you to cite any, whereas others may be ok with some non-scholarly works cited alongside scholarly ones.

Image: Brett Woods. (2006, Jan. 6). Deep Thoughts. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/brettanicus/87653641/. Used under the Creative Commons License.

- << Previous: Types of Sources

- Next: Components of a scholarly article, and things to consider when reading one >>

- Last Updated: Dec 13, 2023 4:36 PM

- URL: https://libraries.wichita.edu/health-research

Difference between Research Paper and Research Article

Research paper and research articles are bits of composing that require inquiry, critical analysis, demonstration and insight of few special abilities from understudies and researchers. This article endeavors to see whether the two terms are synonymous or there is any contrast between the two.

Research paper

Research can be said as activity which is specified much significance in scholastics. Be that as it may, research papers are not only these task papers composed by understudies as those composed by scholars and researchers and also published in different journals are additionally alluded to as research papers.

Research Article

Research article is a bit of composing that have original research thought with the pertinent data and discoveries. A research article is a composing or paper that advises individuals of a way breaking a finding or research with data to bolster the finding.

Research Paper VS Research Article

There is a pattern to allude to academic papers and term papers composed by understudies in schools as a research paper

The articles presented by researchers and scholars with their noteworthy examination are known as research articles.

Research papers composed by the students mostly not take in journals.

Research articles composed by researchers or scholars mostly published in prestigious scientific journals.

A research paper depends on the original research. The sort of research may fluctuate, contingent upon your field or topics that include survey, experiments, questionnaire, interview and so on; yet authors require gathering and investigating raw data and make an original and real study. The research paper will be founded on the investigation and understanding of this raw data.

A research article depends on other different published articles. It is usually not depend on original study. Research articles for the most part condense the current writing on a point trying to clarify the present condition of comprehension on topic.

A research paper can be said as the primary source that means, it studies the techniques and consequences of original study performed by the writers.

A research article can be said as secondary source that means it is composed about different articles, and does not studies actual research of its own.

- Importance:

In research paper, every part of this has its own importance. A concise is important in light of the fact that it shows that the writers know about existing literature, and want to add to this presented research definitively. A methods part is usually detailed and it is important in a way that different analysts have the capacity to check and/or duplicate these strategies. A result segment depicts the results of the analysis.

Research articles can be considered very important because they describe upon different articles that they analyze to propose new research bearings, to give powerful support for presented theories or distinguish designs among presented research studies. For understudy analysts, these research articles give an excellent review of presented literature on that topic. In the event that you discover a literature review that can be fit in study, investigate its references/works referred to list for guide on other articles.

From the above article we can conclude that research paper is the primary source whereas research articles are secondary.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

17 Comments Already

good article but which of them is more useful when we conduct a research

both. but research paper is more useful.

Nice explanation

There is a little difference but both are different.

Nice but i have a confusion that can a guys of Bachelors level can write Research Papers?

YEs they can if they do research project instead of development project and do something new in their project.

Thank you 😊

do you have something in your mind then please share with us. We will appreciate that.

Though it may be fairly easy to learn to speak English well enough to be understood, learning to write English correctly is very difficult, as this article so clearly illustrates. Though I greatly admire all those who are making an effort to learn another language, like English, as a non-native speaker, it is wrong for these same individuals to assume they can write English well enough to publish articles.

This article is so poorly written that I cannot understand most of it. For instance, the following phrases are utter nonsense: “A research paper can be said as the primary source that means,” — “A concise is important in light of the fact that it shows that . . .” — “A methods part is usually detailed” — “A result segment depicts the results . . .” — “they describe upon different articles that they analyze to propose new research bearings . . . or distinguish designs among presented . .. studies” — “to clarify the present condition of comprehension” — “Research papers and . . . articles require inquiry, critical analysis, demonstration and insight of few special abilities from . . .”

This article also states that “[a] research article . . . is usually not depend (sic) on original study,” then contradicts that in the next sentence with “[r]esearch articles . . . condense the current writing on a point . . .” Most studies these days are current. But, even if a study was conducted 50 years ago, it’s a cardinal rule that one should always use the original source of information rather than relying on the articles of other authors who may have misquoted something from the original study.

Articles like this one do a grave disservice to the viewing and researching public. To present this article as informative is disingenuous. To ask people who are seeking useful information to struggle with reading and trying to make sense of this poor English is so unkind and inconsiderate that I feel compelled to bring it to the author’s and publisher’s attention.

I would be honored to help anyone with their efforts to write English, but, please, be honest with yourselves about your lack of knowledge, so you will cease and desist the writing of anything online until your English skills have improved significantly. Thank you.

Thanks for such a detail input. Best wishes.

Yes you are saying right. So if you have the skills to deliver the answer in an efficient manner so kindly type it for me. Because I really want to know the difference between research paper and research article

Yes I agree with Martha. I myself found difficulty in going through the article. Although the topic is very important to be discussed because being the student of graduate, I must know the difference. But the way of delivering has dispirited me that now what other website should I visit to get accurate answer.

we need Published example of a scientific research article and another for a scientific research

how can I cite this?

“Difference between Research Paper and Research Article”, Reserachpedia.info, https://researchpedia.info/difference-between-research-paper-and-research-article/ , [27 December 2021].

I don’t understand anything. I am confused more than i came. Otehrwise, thank you for a trial. Simplify this communication.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

International Journal of Research (IJR)

IJR Journal is Multidisciplinary, high impact and indexed journal for research publication. IJR is a monthly journal for research publication.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RESEARCH PAPER AND JOURNAL ARTICLE

Difference between research paper and journal article.

Research Paper

Argumentative Research Paper

Analytical research paper, journal article, the differences, research paper:, journal article:.

- Share on Tumblr

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Trending Now

- Foundational Courses

- Data Science

- Practice Problem

- Machine Learning

- System Design

- DevOps Tutorial

- Differences between Software Testing and Quality Assurance

- Difference Between VLAN and VPN

- Difference Between GAGAN and GPS

- Difference between Primordial and Non-Primordial Threads

- Difference Between WWW and Public_HTML

- Difference between Google Jamboard and Microsoft Whiteboard

- Difference between message queues and mailboxes

- Differences between Low-Code and No-Code Development

- Difference Between Business Analytics and Predictive Analytics

- Difference between scaling horizontally and vertically for databases

- Difference Between Quantum Computing and Artificial Intelligence

- Difference Between Traditional and Online Education

- Difference between the COPY and ADD commands in a Dockerfile

- Difference between Bower and npm

- Difference between Business Intelligence and Business Analytics

- Difference between Business Intelligence and Data Warehouse

- Differences between a Matrix and a Tensor

- Difference Between Ash and Bash

- Difference Between Peloton and Echelon

Difference between Paper and Article for Scientific Writings

.Difference-table { border-collapse: collapse; width: 100%; } .Difference-table td { text-color: black !important; border: 1px solid #5fb962; text-align: left !important; padding: 8px; } .Difference-table th { border: 1px solid #5fb962; padding: 8px; } .Difference-table tr>th{ background-color: #c6ebd9; vertical-align: middle; } .Difference-table tr:nth-child(odd) { background-color: #ffffff; }

Please Login to comment...

Similar reads.

- Difference Between

- How to Use ChatGPT with Bing for Free?

- 7 Best Movavi Video Editor Alternatives in 2024

- How to Edit Comment on Instagram

- 10 Best AI Grammar Checkers and Rewording Tools

- 30 OOPs Interview Questions and Answers (2024)

Improve your Coding Skills with Practice

What kind of Experience do you want to share?

Difference between Journal Article and Research Paper

Specific education reading is an important tool that will enhance your academic excellence. To keep excelling, you will need to read relevant articles, papers, documents, and books. Journals, Journal articles, and research papers are important mechanisms for professional and academic learning.

Journal Article Vs. Research Paper

The difference between a journal article and a research paper is that the journal article is well researched and extensive. It is also conceptual and well-suited for the academic audience. Research papers on the other hand focus on a specific viewpoint and substantiate the viewpoint with relevant theories. Research papers require many extensive studies to ensure the viewpoint is fully supported.

Comparison between the Journal Article and the Research Paper

- The journal article is an overall publication while a research paper can be cited.

- Journal articles are written based on knowledge and experience while research papers require an in-depth study of the specific topic.

- Journal articles are short while research papers are long and always ongoing.

- You cannot patent a journal article but you can patent a research paper.

- While a research paper does not have a specific domain, journal articles have a broader spectrum.

- There is an impact rating needed for journal articles while no specific rating is needed for the research paper.

What is a Journal Article?

When publishing a journal article, more than one author can be used to give their specific conclusions. Journal articles are of different natures and they can be experiential. Journal articles can be academic or non-academic.

Journal articles can be presented differently as research papers and on different platforms.

What is a Research Paper?

Writing a research paper can take a lot of time. This is because it involves something that has already been published but needs to be reopened again. The first step to writing a research paper is sitting with the thought and why exactly you want to research it. The research will involve the timeframe, type of data collection method to use, and most importantly, in-depth research.

To write a research paper, you will need to do a literature review. This includes the reading of various case studies, findings, newspapers, all containing the topic of research or question to be answered.

Journal articles are written to show special or enhanced knowledge in a certain field. It is useful to bring understanding to a particular field. Journals cannot be written by just anyone. Instead, they are written by experts. A research paper on the other hand revolves around a particular topic or question. The question may contain other questions within it that need to be researched on, re-found, or re-visited. The research paperwork is done using a specific format and supports every point with tactical findings. In short, a research paper is written to answer a question or get findings of something that was already initially researched and written about.

Journals can be a paper written based on something that is currently trending or new ideologies that could be personal experiences and learnings. Research papers on the other hand are more extensive. They involve a particular topic and questions that can be presented using diagrams, graphs, and case studies.

Due to the level of research needed to write a research paper, a lot of time is needed. The findings need to be factual, totally supporting the topic or question in place. Journal papers on the other hand take a short time. That is, they can be completed within a week. A journal can go to a month but does not take as much time as a research paper.