Is It Okay to Use "We" In a Research Paper? Here's What You Need to Know

Explore the use of "we" in research papers: guidelines, alternatives, and considerations for effective academic writing. Learn when and how to use it appropriately.

Jun 25, 2024

When embarking on the journey of academic writing, particularly in research papers, one of the first questions that often arises is about pronoun usage. Specifically, many writers grapple with the question: Is it okay to use "we" in a research paper?

This seemingly simple grammatical choice carries significant weight in academic circles. Using pronouns, especially first-person pronouns like "we," can influence the tone, clarity, and perceived objectivity of your work. It's a topic that has sparked debates among scholars, with opinions evolving and varying across different disciplines.

The importance of pronoun usage in academic writing cannot be overstated, especially in contexts like thesis and scientific writing. It affects how your research is perceived, how you position yourself as an author, and how you engage with your readers using the first person or third person. The choice between using "we," maintaining a more impersonal tone, or opting for alternatives can impact the overall effectiveness of your communication.

In this blog post, we'll explore the nuances of using "we" in research papers, examining both traditional and modern perspectives. We'll delve into the pros and cons, provide guidelines for appropriate usage, and offer alternatives to help you confidently navigate writing academic papers.

Traditional Stance on Using "We" in Research Papers

historical preference for third-person perspective.

Academic writing traditionally favored a third-person perspective, especially in scientific fields. This preference emerged in the late 19th century as part of a push for objectivity in scientific communication. The goal was to present research as unbiased facts and observations.

Key aspects:

- Emphasis on passive voice versus active voice when choosing to use the first person or third person in writing a research paper.

- The use of impersonal constructions and passive voice can help avoid personal pronouns.

- Third-person references to authors

Reasons for avoiding first-person pronouns

Arguments against using "we" in research papers:

- Perceived lack of objectivity

- Ambiguity in meaning

- Concerns about formality

- Shift of focus from research to researchers

- Adherence to established conventions

- Avoid presumption in single-authored papers when you decide to use first-person pronouns or not. when you decide to use first-person pronouns or not.

This approach shaped academic writing for decades and still influences some disciplines, especially in the context of writing a research paper. However, attitudes toward pronoun usage have begun to change in recent years.

Changing Perspectives in Academic Writing

Shift towards more personal and engaging academic prose.

Recent years have seen a move towards more accessible academic writing. This shift aims to:

- Increase readability

- Engage readers more effectively by incorporating second-person narrative techniques.

- Acknowledge the researcher's role in the work

- Promote transparency in research processes

Key changes:

- More direct language

- Increased use of active voice can make your academic papers more engaging.

- Greater acceptance of narrative elements

Acceptance of first-person pronouns in some disciplines

Some fields now allow or encourage the use of "we" and other first-person pronouns. This varies by:

- Discipline: More common in humanities and social sciences

- Journal: Some publications explicitly permit or prefer first-person usage

- Type of paper: Often more accepted in qualitative research or opinion pieces

Reasons for acceptance:

- Clarity in describing methods and decisions

- Ownership of ideas and findings is crucial when writing a research paper.

- Improved reader engagement in scientific writing

- Recognition of researcher subjectivity in some fields

However, acceptance is not universal. Many disciplines and publications still prefer traditional, impersonal styles.

When It's Appropriate to Use "We" in Research Papers

Collaborative research with multiple authors

- Natural fit for papers with multiple contributors

- Accurately reflects joint effort and shared responsibility

- Examples: "We conducted experiments..." or "We conclude that..."

Describing methodology or procedures

- Clarifies who performed specific actions, helping to avoid personal pronouns that might otherwise confuse the audience.

- Adds transparency to the research process, particularly when first-person pronouns are used effectively.

- Example: "We collected data using..."

Presenting arguments or hypotheses

- Demonstrates ownership of ideas

- Can make complex concepts more accessible in a research report.

- Example: "We argue that..." or "We hypothesize..."

Discipline-specific conventions

- Usage varies widely between fields

- More common in Social sciences, Humanities, and Some STEM fields (e.g., computer science)

- Less common in Hard sciences, Medical research

- Always check journal guidelines and field norms, particularly regarding the use of the first person or third person.

Key point: Use "we" judiciously, balancing clarity and convention.

When to Avoid Using "We" in Research Papers

Single-authored papers

- Can seem odd or presumptuous

- Alternatives: Use "I" if appropriate, Use passive voice, and Refer to yourself as " the researcher " or "the author"

Presenting factual information or literature reviews

- Facts stand independently of the author

- Keep the focus on the information, not the presenter, when writing a research paper.

- Examples: "Previous studies have shown..." instead of "We know from previous studies..." "The data indicate..." instead of "We see in the data..."

When trying to maintain an objective tone

- Some topics in research reports require a more detached approach.

- Avoid "we" when: Reporting widely accepted facts, Describing established theories, Presenting controversial findings

- Use impersonal constructions: "It was observed that...", "The results suggest..."

Remember: Always prioritize clarity and adhere to your field's conventions.

Alternatives to Using "We"

Passive voice.

- Shifts focus to the action or result

- Examples: "The experiment was conducted..." (instead of "We experimented...") "It was observed that..." (instead of "We observed that...")

- Use personal pronouns sparingly to avoid overly complex sentences.

Third-person perspective

- Refers to the research or study itself

- Examples: "This study examines..." (instead of "We examine...") "The results indicate..." (instead of "We found...")

- Can create a more objective tone

Using "the researcher(s)" or "the author(s)"

- Useful for single- authored papers

- Maintains formality while acknowledging human involvement

- Examples: "The researchers collected data..." (instead of "We collected data...") "The author argues..." (instead of "We argue...")

- Can become repetitive if overused in writing research papers.

Tips for using alternatives:

- Vary sentence structure to maintain reader interest

- Ensure clarity is not sacrificed for formality

- Choose the most appropriate alternative based on context

- Consider journal guidelines and field conventions when writing a research paper.

Remember: The goal is clear, effective communication of your research, whether you use first person or third person.

Tips for Effective Academic Writing

Consistency in pronoun usage.

- Choose a style and stick to it throughout

- Avoid mixing "we" with impersonal constructions

- Exceptions: Different sections may require different approaches, Clearly mark any intentional shifts in perspective

Balancing formality with clarity and engagement

- Prioritize clear communication

- Use simple, direct language where possible when writing research papers, and try to use the term that best fits the context.

- Engage readers without sacrificing academic rigor

- Techniques: Use active voice judiciously, Vary sentence structure, Incorporate relevant examples or analogies

Seeking feedback from peers or mentors

- Share drafts with colleagues in your field to improve your research report.

- Ask for specific feedback on writing style

- Consider perspectives from Senior researchers , Peers at similar career stages, Potential target audience members, and how they prefer the use of the first person or third person in research.

- Be open to constructive criticism

Additional tips:

- Read widely in your field to understand style norms when writing research papers.

- Practice different writing styles to find your voice

- Revise and edit multiple times

- Use style guides relevant to your discipline

- Consider the reader's perspective while writing

Remember: Effective academic writing communicates complex ideas while meeting field-specific expectations.

Recap of key points

- The use of "we" in research papers is evolving

- Appropriateness depends on Discipline, Journal guidelines, Research type, Personal preference

- Alternatives include passive voice and third-person perspective, while the increased use of passive voice can sometimes create ambiguity.

- Consider audience, field norms, and clarity when choosing a style

- Consistency and balance in the use of first person or third person are crucial.

Encouragement to make informed choices in academic writing

- Understand the context of your work

- Stay informed about current trends in your field

- Prioritize clear communication of your research

- Be confident in your choices, but remain flexible

- Remember: No universal rule fits all situations, Effective writing adapts to its purpose and audience

- Continually refine your writing skills, including the appropriate use of personal pronouns in APA format.

Final thoughts:

- Writing style impacts how your research is received

- Make deliberate choices to enhance your paper's impact by using appropriate personal pronouns.

- Balance tradition with evolving norms in academic writing

- Your unique voice can contribute to advancing your field, particularly in writing a research paper.

Ultimately, choose a style that best serves your research and readers while adhering to relevant guidelines of scientific writing and thesis format. It may also be acceptable to use first-person pronouns where appropriate.

Easily pronounces technical words in any field

Writing Style

Pronoun Usage

Research Papers

Academic Writing

Recent articles

Best Business Schools in the US

Glice Martineau

Jul 10, 2024

Graduate School

United States of America

Business School

When Does College Start in the US?

Kate Windsor

College search tools

College admissions guide

College planning tips

College academic calendar

Summer term

Quarter system calendar

Spring semester start

Fall semester start

College start dates

When does college start

How to Apply to Graduate School? Practical and Helpful Tips

Derek Pankaew

Jul 11, 2024

#GradSchoolApplication

#GraduateSchool

#HigherEducation

#AdmissionTips

#PersonalStatement

9 Things I Wish I Knew Before Starting a PhD

#AcademicJourney

#GradSchoolTips

#PhDStudentLife

#ResearchAndMentorship

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Can You Use I or We in a Research Paper?

4-minute read

- 11th July 2023

Writing in the first person, or using I and we pronouns, has traditionally been frowned upon in academic writing . But despite this long-standing norm, writing in the first person isn’t actually prohibited. In fact, it’s becoming more acceptable – even in research papers.

If you’re wondering whether you can use I (or we ) in your research paper, you should check with your institution first and foremost. Many schools have rules regarding first-person use. If it’s up to you, though, we still recommend some guidelines. Check out our tips below!

When Is It Most Acceptable to Write in the First Person?

Certain sections of your paper are more conducive to writing in the first person. Typically, the first person makes sense in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections. You should still limit your use of I and we , though, or your essay may start to sound like a personal narrative .

Using first-person pronouns is most useful and acceptable in the following circumstances.

When doing so removes the passive voice and adds flow

Sometimes, writers have to bend over backward just to avoid using the first person, often producing clunky sentences and a lot of passive voice constructions. The first person can remedy this. For example:

Both sentences are fine, but the second one flows better and is easier to read.

When doing so differentiates between your research and other literature

When discussing literature from other researchers and authors, you might be comparing it with your own findings or hypotheses . Using the first person can help clarify that you are engaging in such a comparison. For example:

In the first sentence, using “the author” to avoid the first person creates ambiguity. The second sentence prevents misinterpretation.

When doing so allows you to express your interest in the subject

In some instances, you may need to provide background for why you’re researching your topic. This information may include your personal interest in or experience with the subject, both of which are easier to express using first-person pronouns. For example:

Expressing personal experiences and viewpoints isn’t always a good idea in research papers. When it’s appropriate to do so, though, just make sure you don’t overuse the first person.

When to Avoid Writing in the First Person

It’s usually a good idea to stick to the third person in the methods and results sections of your research paper. Additionally, be careful not to use the first person when:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● It makes your findings seem like personal observations rather than factual results.

● It removes objectivity and implies that the writing may be biased .

● It appears in phrases such as I think or I believe , which can weaken your writing.

Keeping Your Writing Formal and Objective

Using the first person while maintaining a formal tone can be tricky, but keeping a few tips in mind can help you strike a balance. The important thing is to make sure the tone isn’t too conversational.

To achieve this, avoid referring to the readers, such as with the second-person you . Use we and us only when referring to yourself and the other authors/researchers involved in the paper, not the audience.

It’s becoming more acceptable in the academic world to use first-person pronouns such as we and I in research papers. But make sure you check with your instructor or institution first because they may have strict rules regarding this practice.

If you do decide to use the first person, make sure you do so effectively by following the tips we’ve laid out in this guide. And once you’ve written a draft, send us a copy! Our expert proofreaders and editors will be happy to check your grammar, spelling, word choice, references, tone, and more. Submit a 500-word sample today!

Is it ever acceptable to use I or we in a research paper?

In some instances, using first-person pronouns can help you to establish credibility, add clarity, and make the writing easier to read.

How can I avoid using I in my writing?

Writing in the passive voice can help you to avoid using the first person.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

First-Person Pronouns

Use first-person pronouns in APA Style to describe your work as well as your personal reactions.

- If you are writing a paper by yourself, use the pronoun “I” to refer to yourself.

- If you are writing a paper with coauthors, use the pronoun “we” to refer yourself and your coauthors together.

Referring to yourself in the third person

Do not use the third person to refer to yourself. Writers are often tempted to do this as a way to sound more formal or scholarly; however, it can create ambiguity for readers about whether you or someone else performed an action.

Correct: I explored treatments for social anxiety.

Incorrect: The author explored treatments for social anxiety.

First-person pronouns are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Section 4.16 and the Concise Guide Section 2.16

Editorial “we”

Also avoid the editorial “we” to refer to people in general.

Incorrect: We often worry about what other people think of us.

Instead, specify the meaning of “we”—do you mean other people in general, other people of your age, other students, other psychologists, other nurses, or some other group? The previous sentence can be clarified as follows:

Correct: As young adults, we often worry about what other people think of us. I explored my own experience of social anxiety...

When you use the first person to describe your own actions, readers clearly understand when you are writing about your own work and reactions versus those of other researchers.

We Vs. They: Using the First & Third Person in Research Papers

Writing in the first , second , or third person is referred to as the author’s point of view . When we write, our tendency is to personalize the text by writing in the first person . That is, we use pronouns such as “I” and “we”. This is acceptable when writing personal information, a journal, or a book. However, it is not common in academic writing.

Some writers find the use of first , second , or third person point of view a bit confusing while writing research papers. Since second person is avoided while writing in academic or scientific papers, the main confusion remains within first or third person.

In the following sections, we will discuss the usage and examples of the first , second , and third person point of view.

First Person Pronouns

The first person point of view simply means that we use the pronouns that refer to ourselves in the text. These are as follows:

Can we use I or We In the Scientific Paper?

Using these, we present the information based on what “we” found. In science and mathematics, this point of view is rarely used. It is often considered to be somewhat self-serving and arrogant . It is important to remember that when writing your research results, the focus of the communication is the research and not the persons who conducted the research. When you want to persuade the reader, it is best to avoid personal pronouns in academic writing even when it is personal opinion from the authors of the study. In addition to sounding somewhat arrogant, the strength of your findings might be underestimated.

For example:

Based on my results, I concluded that A and B did not equal to C.

In this example, the entire meaning of the research could be misconstrued. The results discussed are not those of the author ; they are generated from the experiment. To refer to the results in this context is incorrect and should be avoided. To make it more appropriate, the above sentence can be revised as follows:

Based on the results of the assay, A and B did not equal to C.

Second Person Pronouns

The second person point of view uses pronouns that refer to the reader. These are as follows:

This point of view is usually used in the context of providing instructions or advice , such as in “how to” manuals or recipe books. The reason behind using the second person is to engage the reader.

You will want to buy a turkey that is large enough to feed your extended family. Before cooking it, you must wash it first thoroughly with cold water.

Although this is a good technique for giving instructions, it is not appropriate in academic or scientific writing.

Third Person Pronouns

The third person point of view uses both proper nouns, such as a person’s name, and pronouns that refer to individuals or groups (e.g., doctors, researchers) but not directly to the reader. The ones that refer to individuals are as follows:

- Hers (possessive form)

- His (possessive form)

- Its (possessive form)

- One’s (possessive form)

The third person point of view that refers to groups include the following:

- Their (possessive form)

- Theirs (plural possessive form)

Everyone at the convention was interested in what Dr. Johnson presented. The instructors decided that the students should help pay for lab supplies. The researchers determined that there was not enough sample material to conduct the assay.

The third person point of view is generally used in scientific papers but, at times, the format can be difficult. We use indefinite pronouns to refer back to the subject but must avoid using masculine or feminine terminology. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he has enough material for his experiment. The nurse must ensure that she has a large enough blood sample for her assay.

Many authors attempt to resolve this issue by using “he or she” or “him or her,” but this gets cumbersome and too many of these can distract the reader. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he or she has enough material for his or her experiment. The nurse must ensure that he or she has a large enough blood sample for his or her assay.

These issues can easily be resolved by making the subjects plural as follows:

Researchers must ensure that they have enough material for their experiment. Nurses must ensure that they have large enough blood samples for their assay.

Exceptions to the Rules

As mentioned earlier, the third person is generally used in scientific writing, but the rules are not quite as stringent anymore. It is now acceptable to use both the first and third person pronouns in some contexts, but this is still under controversy.

In a February 2011 blog on Eloquent Science , Professor David M. Schultz presented several opinions on whether the author viewpoints differed. However, there appeared to be no consensus. Some believed that the old rules should stand to avoid subjectivity, while others believed that if the facts were valid, it didn’t matter which point of view was used.

First or Third Person: What Do The Journals Say

In general, it is acceptable in to use the first person point of view in abstracts, introductions, discussions, and conclusions, in some journals. Even then, avoid using “I” in these sections. Instead, use “we” to refer to the group of researchers that were part of the study. The third person point of view is used for writing methods and results sections. Consistency is the key and switching from one point of view to another within sections of a manuscript can be distracting and is discouraged. It is best to always check your author guidelines for that particular journal. Once that is done, make sure your manuscript is free from the above-mentioned or any other grammatical error.

You are the only researcher involved in your thesis project. You want to avoid using the first person point of view throughout, but there are no other researchers on the project so the pronoun “we” would not be appropriate. What do you do and why? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments section below.

I am writing the history of an engineering company for which I worked. How do I relate a significant incident that involved me?

Hi Roger, Thank you for your question. If you are narrating the history for the company that you worked at, you would have to refer to it from an employee’s perspective (third person). If you are writing the history as an account of your experiences with the company (including the significant incident), you could refer to yourself as ”I” or ”My.” (first person) You could go through other articles related to language and grammar on Enago Academy’s website https://enago.com/academy/ to help you with your document drafting. Did you get a chance to install our free Mobile App? https://www.enago.com/academy/mobile-app/ . Make sure you subscribe to our weekly newsletter: https://www.enago.com/academy/subscribe-now/ .

Good day , i am writing a research paper and m y setting is a company . is it ethical to put the name of the company in the research paper . i the management has allowed me to conduct my research in thir company .

thanks docarlene diaz

Generally authors do not mention the names of the organization separately within the research paper. The name of the educational institution the researcher or the PhD student is working in needs to be mentioned along with the name in the list of authors. However, if the research has been carried out in a company, it might not be mandatory to mention the name after the name in the list of authors. You can check with the author guidelines of your target journal and if needed confirm with the editor of the journal. Also check with the mangement of the company whether they want the name of the company to be mentioned in the research paper.

Finishing up my dissertation the information is clear and concise.

How to write the right first person pronoun if there is a single researcher? Thanks

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Use of "I", "we" and the passive voice in a scientific thesis [duplicate]

Possible Duplicate: Style Question: Use of “we” vs. “I” vs. passive voice in a dissertation

When the first person voice is used in scientific writing it is mostly used in the first person plural, as scientific papers almost always have more than one co-author, such as

We propose a new method to study cell differentiation in nematodes.

Often the "we" also includes the reader

We may see in Figure 4.2 that...

However, I am writing a thesis which means I am the only author and I even have to testify in writing that the work is my own and I did not receive any help other than from the indicated sources. Therefore it seems I should use "I", but this seems to be very unusual in scientific writing and even discouraged as one may sound pretentious or self-absorbed. However, the alternative is to use the passive voice, which seems to be even more discouraged as it produces hard to read writing and indeed an entire thesis in the passive voice may be indigestible for any reader.

So far, I used the second form of "we" extensively that includes me and the reader. This form is often natural when describing mathematical derivations as the truth is objective and it suggests that I am taking the reader by the hand and walking her through the process. Still, I'm trying not do overdo this form.

However, eventually I will need to refer to methods that I propose and choices that I have made. Should I just follow scientific convention and use "we" although it is factually inaccurate or indeed write in the scorned-upon "I"?

- writing-style

- mathematics

- passive-voice

- personal-pronouns

- 3 In your particular case, an inclusive we could be used to recognize the nematodes collaboration :) – Dr. belisarius Commented May 10, 2011 at 13:01

- 3 I find the use of "we" odd if there is only one author. I read a paper by a single author recently and he consistently wrote things like "we propose...", "we then present..." and I kept thinking, wait, who did you work with? – Flash Commented May 10, 2011 at 14:08

- 2 @Andrew: Seriously? You read academic papers, and you're not at least aware of the convention? You might not endorse it, but you could just accept it as something some people do. – FumbleFingers Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:05

- 1 @oceanhug: Probably saying nothing you don't already know, but bear in mind this sort of question could become a bit of a 'poll'. And there will be plenty of people who actively dislike using the effectively 'singular we' in any context. Because of associations with the 'academic old guard', the 'regal we', whatever. Or in solidarity with the march towards 'individualism' that marks Western civilisation. You, on the other hand, have a thesis to write. – FumbleFingers Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:58

- I have seen academic papers by a single author using I . However I agree with FumbleFingers that most of the time you would use we , and that I sounds strange in an academic paper. Personally, if I were to read your thesis and saw we , I wouldn't find it as an implication that you were not the only author of the work. Also, I assume you will have a thesis supervisor, who is also responsible to check (and possibly approve) your work, so you can include him/her in the we . – nico Commented May 11, 2011 at 6:47

6 Answers 6

I tried to use "I" in the first version of my thesis (in mathematics). When my advisor suggested corrections, the most detailed and strongly-worded of them was to use "we"; later, I asked another young professor whether one could use "I" and she said "Only if you want to sound like an arrogant bastard", and observed that only old people with established reputations can get away with it.

My extremely informal recollection of some articles that are more than, say, forty years old is that the singular is used more often, so what she says may be true but for a different reason than simple pride. The modern culture may disparage apparent displays of ego simply because of the greater prevalence of collaboration, whether or not your paper is a product of it. This is complete speculation, though.

I disagreed with the change at the time but acquiesced anyway, and now, with distance, I realize that it was a good idea. Scattering the paper with "I" draws attention to the author, and especially in mathematical writing, the prose is filled with impersonal subjects (that is, you often don't mean "I" literally, as in "If y = f(x), then we have an equation..."). Using "we" allows it to simply sink into the background, where it belongs. If it's your thesis, you don't have to put any special effort into reminding the reader who is talking, just like in an essay, they used to tell me not to say "in my opinion" before stating it.

EDIT: Oh, I forgot entirely about "the author". I hate that phrase, because it is just as inconsistent with "we" as with "I" and disingenuous to boot. If you have to make a truly personal remark, just say "I", and perhaps set off the entire comment by "Personally..." or something like that.

- 3 Excellent answer. I totally agree on all points, which you express well. Egalitarianism, individualism, or whatever may push for the first person singular, but it's distracting in serious academic texts. Though I don't have a big problem with ' the author ' once (maybe twice). – FumbleFingers Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:14

- 7 We think you’ve hit the nail on the head with your speculation. – Konrad Rudolph Commented May 11, 2011 at 14:23

- 1 -1; I strongly disagree. Moreover, the APA (and perhaps other) style manuals disagree. The persistence of using the passive voice to minimize the use of first person pronouns is a historical affectation that most of us have been trained from a young age to slavishly employ. However, it tends to yield awkward prose that is hard to read. If the greatest crime that must be committed is either "egotism" or "lack of clarity", I certainly choose to be egotistic. – russellpierce Commented Oct 23, 2012 at 16:06

- 6 @RyanReich: You know that a down-vote is not a personal criticism right? – russellpierce Commented Dec 24, 2012 at 14:45

- 2 @russellpierce. There are enough people around saying "never use passive voice" that they need to be argued against. The passive voice should be used whenever it improves your prose, and this happens moderately often. If you look at some early scientific papers, the incessant use of the first person pronoun can be really distracting, and many of these uses can be avoided using the passive voice. – Peter Shor Commented Oct 16, 2017 at 16:00

I don't think there's anything wrong with using we in single-author scientific journal papers. It's the tradition, and if you use I in scientific papers it stands out, not necessarily in a good way. On the other hand, a PhD thesis is not a scientific journal paper, but a PhD thesis, and if you want to use I in it I don't see anything wrong with that.

The passive voice should not be used to avoid writing I or we . If the entire thesis is written in the passive voice, it is much harder to read, and the sentences within it 1 have to be reworded awkwardly so that some good transitions between the sentences within a paragraph are lost. On the other hand, if some sentences seem to require the passive voice, by all means those sentences should be written in the passive voice. But the passive voice should only be used where it is justified, that is, where its use improves readability of the thesis.

1 See how much better your sentences would read here.

- Shor: In the end I mostly go with @Ryan Reich's answer, but you and @Rafael Beraldo make additional important points. I'm minded to say that - probably with no concious effort on your part - you only used I once in your second paragraph. And that was only to quote the word. When I compare my sentences here with yours, I think yours look more authoritative, academic, educational, etc. You say you don't see anything wrong with I, but I bet you wouldn't use it in OP's position lol – FumbleFingers Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:47

- 3 @FumbleFingers: The lack of pronouns I and you in my second paragraph was quite deliberate, and took some effort. – Peter Shor Commented May 11, 2011 at 1:30

- Shor: Ah. Well, it was worth the effort from my point of view, if that's any recompense for your labours. But I notice you don't deny you'd avoid using I in a thesis yourself, even if you wouldn't think of that as particularly wrong on the part of someone else. – FumbleFingers Commented May 11, 2011 at 2:40

- @FumbleFingers: I've only written one thesis, and the pronoun we is the one I mainly used in it. – Peter Shor Commented May 11, 2011 at 10:30

- 1 some authors use I instead of we when only one author: link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00114-008-0435-3 – Tomas Commented Apr 13, 2016 at 10:39

By all means write "I". By an amusing coincidence, I have in front of me the article Deformations of Symmetric Products , a proceedings article published by Princeton University Press. The author is the late George R. Kempf, a distinguished algebraic geometer, and on the very first page I read [not we read:-)]: "My proof uses heavily the deformation theory..." . And on the second page "I will use without particular references standard facts from deformation theory". I could give any number of examples: this usage is quite widespread.

- 1 The very example you give supports the opposite view. As a ' distinguished algebraic geometer ', of course Kempf could get away with "I" if he wanted to be self-indulgent. It may become less noticed in future, but in the here and now many (including perhaps those who will assess OP's thesis) both notice and deplore it. – FumbleFingers Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:22

- 1 @FumbleFingers: I just gave a factual reference to show that "I" is indeed used. Calling the late George Kempf self-indulgent is rather insulting. – Georges Elencwajg Commented May 11, 2011 at 9:52

- 1 I have no opinion on Kempf. Perhaps I should have used less loaded phrasing. I just meant that what's appropriate / acceptable for distinguished academicians isn't necessarily the best option for a somewhat more humble thesis-writer. Okay, it was OTT to baldly say your example supports the opposite view. But depending how you look at things, it supports either or neither position. – FumbleFingers Commented May 11, 2011 at 13:44

Many people in academia encourage the use of “we” instead of “I”, although many other people don’t — I can easily remember that Chomsky, at least in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax , do use the first-person singular. Personally, I prefer to use “I”, if I’m the only author. I believe that it sounds much better, not to mention, humbler.

If you have an adviser, then you should really ask him. If you’re writing for a journal, see if they have published articles in which the author use “I” instead of “we”.

- 1 I like @Ryan Reich's answer better, to be honest. But you make the important additional point that much academic output can and should be guided by what's expected in context . Ask your advisor, mentor, editor or whatever if you don't already know that context. Don't do the 'unexpected' without being aware you're doing it, and having some idea how it'll go down. That would hardly be a rigorous academic approach. – FumbleFingers Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:33

- @FumbleFingers, thank you. For some reason, I find the use of “we” to be conservative. Although science is not a solo task,there is nothing bad in remembering the reader that this is only your interpretation and findings about the subject. This is less obvious when reading seminal books on any area — by saying “I”, the author reminds us that he is human, and not a king ruling. – rberaldo Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:54

- I think it's a finely-balanced thing, and all your arguments carry weight. The bottom line for OP should be 'ask the man', but we can afford to have our own personal positions. I only wrote one thesis, decades ago, and I bet I never used "I" once. Since then I've been in programming, and I nearly always use "we" in comments (in code that I wrote alone), even though most of that code was never likely to even be read by anyone except me. YMMD – FumbleFingers Commented May 10, 2011 at 23:19

Remember that in situations like this, it is common for the author to refer to himself as "this author," e.g., "This author proposes a novel solution to the problem of X."

- In general this author is used only for personal opinions. "This author believes that the statistical tools used in most previous articles on this topic are inadequate" , but not "this author collected samples ..." – Peter Shor Commented Nov 1, 2018 at 11:45

How about using neither? What about using factual voice instead :

"A new method to study cell differentiation in nematodes is proposed.""A new method to study cell differentiation in nematodes will be proposed." or "Figure 4.2 shows that..."

"A new method to study cell differentiation in nematodes will be proposed."

Was Replaced with :

"A new method to study cell differentiation in nematodes is proposed."

in accordance with suggestions (details in comments below).

- 4 That is passive. Nothing wrong with it, but that's what it is. – Cerberus - Reinstate Monica Commented May 10, 2011 at 12:09

- 1 Nix the "will be" with "has been". I recommend using positive and factual statements, and not futuristic promises. By the time someone reads this, the works has already been done, and has been reported on. – John Alexiou Commented May 10, 2011 at 16:33

- 2 "Figure 4.2 shows that..." Good: definitely an improvement over the original. "A new method to study cell differentiation in nematodes will be proposed." Terrible: this kind of use of the passive voice to avoid writing we or I makes papers much harder to read. – Peter Shor Commented May 10, 2011 at 18:19

- #Peter : Thanks , What about "A new method to study cell differentiation in nematodes is proposed."? – jimjim Commented May 10, 2011 at 22:27

- 2 @ja72: Not will be , not has been , A new method to study ... is proposed. You're proposing it as you write; the fact that the reader reads it later is completely immaterial; if you say has been , you are saying that you (or somebody else) proposed it in a previous paper. – Peter Shor Commented Nov 1, 2018 at 11:36

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged writing writing-style mathematics passive-voice personal-pronouns or ask your own question .

- Featured on Meta

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

- Upcoming initiatives on Stack Overflow and across the Stack Exchange network...

- We spent a sprint addressing your requests — here’s how it went

Hot Network Questions

- Is it rude to ask Phd student to give daily report?

- Order of pole of Poincaré series

- Travel in Schengen with French residence permit stolen abroad

- Relation between Unity of Apperception and judgements in Kant

- Open or closed windows in a tornado?

- Alternative to isinglass for tarts or other desserts

- Is there any country/case where entering with two different passports at two different times may cause an issue?

- How to port Matlab/Python's Multivariate FoxH implementation in Mathematica?

- Why don't we call value investing "timing the market"?

- 1 External SSD with OS and all files, used by 2 Macs, possible?

- Why mention Balak ben Tzipor?

- Do we always use "worsen" with something which is already bad?

- How to restore a destroyed vampire as a vampire?

- Is it possible to have a double miracle Sudoku grid?

- How to save oneself from this particular angst?

- Diminished/Half diminished

- Why is the MOSFET in this fan control circuit overheating?

- ANOVA with unreliable measure

- How many blocks per second can be sustainably be created using a time warp attack?

- In exercise 8.23 of Nielsen and Chuang why is the quantum operation no longer trace-preserving?

- Is the system y(t) = d x(t)/dt memoryless

- Old client wants files from materials created for them 6 years ago

- Can a group have a subgroup whose complement is closed under the group operation?

- What are the functions obtained by complex polynomials evaluated at complex numbers

Should I Use “I”?

What this handout is about.

This handout is about determining when to use first person pronouns (“I”, “we,” “me,” “us,” “my,” and “our”) and personal experience in academic writing. “First person” and “personal experience” might sound like two ways of saying the same thing, but first person and personal experience can work in very different ways in your writing. You might choose to use “I” but not make any reference to your individual experiences in a particular paper. Or you might include a brief description of an experience that could help illustrate a point you’re making without ever using the word “I.” So whether or not you should use first person and personal experience are really two separate questions, both of which this handout addresses. It also offers some alternatives if you decide that either “I” or personal experience isn’t appropriate for your project. If you’ve decided that you do want to use one of them, this handout offers some ideas about how to do so effectively, because in many cases using one or the other might strengthen your writing.

Expectations about academic writing

Students often arrive at college with strict lists of writing rules in mind. Often these are rather strict lists of absolutes, including rules both stated and unstated:

- Each essay should have exactly five paragraphs.

- Don’t begin a sentence with “and” or “because.”

- Never include personal opinion.

- Never use “I” in essays.

We get these ideas primarily from teachers and other students. Often these ideas are derived from good advice but have been turned into unnecessarily strict rules in our minds. The problem is that overly strict rules about writing can prevent us, as writers, from being flexible enough to learn to adapt to the writing styles of different fields, ranging from the sciences to the humanities, and different kinds of writing projects, ranging from reviews to research.

So when it suits your purpose as a scholar, you will probably need to break some of the old rules, particularly the rules that prohibit first person pronouns and personal experience. Although there are certainly some instructors who think that these rules should be followed (so it is a good idea to ask directly), many instructors in all kinds of fields are finding reason to depart from these rules. Avoiding “I” can lead to awkwardness and vagueness, whereas using it in your writing can improve style and clarity. Using personal experience, when relevant, can add concreteness and even authority to writing that might otherwise be vague and impersonal. Because college writing situations vary widely in terms of stylistic conventions, tone, audience, and purpose, the trick is deciphering the conventions of your writing context and determining how your purpose and audience affect the way you write. The rest of this handout is devoted to strategies for figuring out when to use “I” and personal experience.

Effective uses of “I”:

In many cases, using the first person pronoun can improve your writing, by offering the following benefits:

- Assertiveness: In some cases you might wish to emphasize agency (who is doing what), as for instance if you need to point out how valuable your particular project is to an academic discipline or to claim your unique perspective or argument.

- Clarity: Because trying to avoid the first person can lead to awkward constructions and vagueness, using the first person can improve your writing style.

- Positioning yourself in the essay: In some projects, you need to explain how your research or ideas build on or depart from the work of others, in which case you’ll need to say “I,” “we,” “my,” or “our”; if you wish to claim some kind of authority on the topic, first person may help you do so.

Deciding whether “I” will help your style

Here is an example of how using the first person can make the writing clearer and more assertive:

Original example:

In studying American popular culture of the 1980s, the question of to what degree materialism was a major characteristic of the cultural milieu was explored.

Better example using first person:

In our study of American popular culture of the 1980s, we explored the degree to which materialism characterized the cultural milieu.

The original example sounds less emphatic and direct than the revised version; using “I” allows the writers to avoid the convoluted construction of the original and clarifies who did what.

Here is an example in which alternatives to the first person would be more appropriate:

As I observed the communication styles of first-year Carolina women, I noticed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

Better example:

A study of the communication styles of first-year Carolina women revealed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

In the original example, using the first person grounds the experience heavily in the writer’s subjective, individual perspective, but the writer’s purpose is to describe a phenomenon that is in fact objective or independent of that perspective. Avoiding the first person here creates the desired impression of an observed phenomenon that could be reproduced and also creates a stronger, clearer statement.

Here’s another example in which an alternative to first person works better:

As I was reading this study of medieval village life, I noticed that social class tended to be clearly defined.

This study of medieval village life reveals that social class tended to be clearly defined.

Although you may run across instructors who find the casual style of the original example refreshing, they are probably rare. The revised version sounds more academic and renders the statement more assertive and direct.

Here’s a final example:

I think that Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases, or at least it seems that way to me.

Better example

Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases.

In this example, there is no real need to announce that that statement about Aristotle is your thought; this is your paper, so readers will assume that the ideas in it are yours.

Determining whether to use “I” according to the conventions of the academic field

Which fields allow “I”?

The rules for this are changing, so it’s always best to ask your instructor if you’re not sure about using first person. But here are some general guidelines.

Sciences: In the past, scientific writers avoided the use of “I” because scientists often view the first person as interfering with the impression of objectivity and impersonality they are seeking to create. But conventions seem to be changing in some cases—for instance, when a scientific writer is describing a project she is working on or positioning that project within the existing research on the topic. Check with your science instructor to find out whether it’s o.k. to use “I” in their class.

Social Sciences: Some social scientists try to avoid “I” for the same reasons that other scientists do. But first person is becoming more commonly accepted, especially when the writer is describing their project or perspective.

Humanities: Ask your instructor whether you should use “I.” The purpose of writing in the humanities is generally to offer your own analysis of language, ideas, or a work of art. Writers in these fields tend to value assertiveness and to emphasize agency (who’s doing what), so the first person is often—but not always—appropriate. Sometimes writers use the first person in a less effective way, preceding an assertion with “I think,” “I feel,” or “I believe” as if such a phrase could replace a real defense of an argument. While your audience is generally interested in your perspective in the humanities fields, readers do expect you to fully argue, support, and illustrate your assertions. Personal belief or opinion is generally not sufficient in itself; you will need evidence of some kind to convince your reader.

Other writing situations: If you’re writing a speech, use of the first and even the second person (“you”) is generally encouraged because these personal pronouns can create a desirable sense of connection between speaker and listener and can contribute to the sense that the speaker is sincere and involved in the issue. If you’re writing a resume, though, avoid the first person; describe your experience, education, and skills without using a personal pronoun (for example, under “Experience” you might write “Volunteered as a peer counselor”).

A note on the second person “you”:

In situations where your intention is to sound conversational and friendly because it suits your purpose, as it does in this handout intended to offer helpful advice, or in a letter or speech, “you” might help to create just the sense of familiarity you’re after. But in most academic writing situations, “you” sounds overly conversational, as for instance in a claim like “when you read the poem ‘The Wasteland,’ you feel a sense of emptiness.” In this case, the “you” sounds overly conversational. The statement would read better as “The poem ‘The Wasteland’ creates a sense of emptiness.” Academic writers almost always use alternatives to the second person pronoun, such as “one,” “the reader,” or “people.”

Personal experience in academic writing

The question of whether personal experience has a place in academic writing depends on context and purpose. In papers that seek to analyze an objective principle or data as in science papers, or in papers for a field that explicitly tries to minimize the effect of the researcher’s presence such as anthropology, personal experience would probably distract from your purpose. But sometimes you might need to explicitly situate your position as researcher in relation to your subject of study. Or if your purpose is to present your individual response to a work of art, to offer examples of how an idea or theory might apply to life, or to use experience as evidence or a demonstration of an abstract principle, personal experience might have a legitimate role to play in your academic writing. Using personal experience effectively usually means keeping it in the service of your argument, as opposed to letting it become an end in itself or take over the paper.

It’s also usually best to keep your real or hypothetical stories brief, but they can strengthen arguments in need of concrete illustrations or even just a little more vitality.

Here are some examples of effective ways to incorporate personal experience in academic writing:

- Anecdotes: In some cases, brief examples of experiences you’ve had or witnessed may serve as useful illustrations of a point you’re arguing or a theory you’re evaluating. For instance, in philosophical arguments, writers often use a real or hypothetical situation to illustrate abstract ideas and principles.

- References to your own experience can explain your interest in an issue or even help to establish your authority on a topic.

- Some specific writing situations, such as application essays, explicitly call for discussion of personal experience.

Here are some suggestions about including personal experience in writing for specific fields:

Philosophy: In philosophical writing, your purpose is generally to reconstruct or evaluate an existing argument, and/or to generate your own. Sometimes, doing this effectively may involve offering a hypothetical example or an illustration. In these cases, you might find that inventing or recounting a scenario that you’ve experienced or witnessed could help demonstrate your point. Personal experience can play a very useful role in your philosophy papers, as long as you always explain to the reader how the experience is related to your argument. (See our handout on writing in philosophy for more information.)

Religion: Religion courses might seem like a place where personal experience would be welcomed. But most religion courses take a cultural, historical, or textual approach, and these generally require objectivity and impersonality. So although you probably have very strong beliefs or powerful experiences in this area that might motivate your interest in the field, they shouldn’t supplant scholarly analysis. But ask your instructor, as it is possible that they are interested in your personal experiences with religion, especially in less formal assignments such as response papers. (See our handout on writing in religious studies for more information.)

Literature, Music, Fine Arts, and Film: Writing projects in these fields can sometimes benefit from the inclusion of personal experience, as long as it isn’t tangential. For instance, your annoyance over your roommate’s habits might not add much to an analysis of “Citizen Kane.” However, if you’re writing about Ridley Scott’s treatment of relationships between women in the movie “Thelma and Louise,” some reference your own observations about these relationships might be relevant if it adds to your analysis of the film. Personal experience can be especially appropriate in a response paper, or in any kind of assignment that asks about your experience of the work as a reader or viewer. Some film and literature scholars are interested in how a film or literary text is received by different audiences, so a discussion of how a particular viewer or reader experiences or identifies with the piece would probably be appropriate. (See our handouts on writing about fiction , art history , and drama for more information.)

Women’s Studies: Women’s Studies classes tend to be taught from a feminist perspective, a perspective which is generally interested in the ways in which individuals experience gender roles. So personal experience can often serve as evidence for your analytical and argumentative papers in this field. This field is also one in which you might be asked to keep a journal, a kind of writing that requires you to apply theoretical concepts to your experiences.

History: If you’re analyzing a historical period or issue, personal experience is less likely to advance your purpose of objectivity. However, some kinds of historical scholarship do involve the exploration of personal histories. So although you might not be referencing your own experience, you might very well be discussing other people’s experiences as illustrations of their historical contexts. (See our handout on writing in history for more information.)

Sciences: Because the primary purpose is to study data and fixed principles in an objective way, personal experience is less likely to have a place in this kind of writing. Often, as in a lab report, your goal is to describe observations in such a way that a reader could duplicate the experiment, so the less extra information, the better. Of course, if you’re working in the social sciences, case studies—accounts of the personal experiences of other people—are a crucial part of your scholarship. (See our handout on writing in the sciences for more information.)

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Tips & Guides

How To Avoid Using “We,” “You,” And “I” in an Essay

- Posted on October 27, 2022 October 27, 2022

Maintaining a formal voice while writing academic essays and papers is essential to sound objective.

One of the main rules of academic or formal writing is to avoid first-person pronouns like “we,” “you,” and “I.” These words pull focus away from the topic and shift it to the speaker – the opposite of your goal.

While it may seem difficult at first, some tricks can help you avoid personal language and keep a professional tone.

Let’s learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

What Is a Personal Pronoun?

Pronouns are words used to refer to a noun indirectly. Examples include “he,” “his,” “her,” and “hers.” Any time you refer to a noun – whether a person, object, or animal – without using its name, you use a pronoun.

Personal pronouns are a type of pronoun. A personal pronoun is a pronoun you use whenever you directly refer to the subject of the sentence.

Take the following short paragraph as an example:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. Mr. Smith also said that Mr. Smith lost Mr. Smith’s laptop in the lunchroom.”

The above sentence contains no pronouns at all. There are three places where you would insert a pronoun, but only two where you would put a personal pronoun. See the revised sentence below:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. He also said that he lost his laptop in the lunchroom.”

“He” is a personal pronoun because we are talking directly about Mr. Smith. “His” is not a personal pronoun (it’s a possessive pronoun) because we are not speaking directly about Mr. Smith. Rather, we are talking about Mr. Smith’s laptop.

If later on you talk about Mr. Smith’s laptop, you may say:

“Mr. Smith found it in his car, not the lunchroom!”

In this case, “it” is a personal pronoun because in this point of view we are making a reference to the laptop directly and not as something owned by Mr. Smith.

Why Avoid Personal Pronouns in Essay Writing

We’re teaching you how to avoid using “I” in writing, but why is this necessary? Academic writing aims to focus on a clear topic, sound objective, and paint the writer as a source of authority. Word choice can significantly impact your success in achieving these goals.

Writing that uses personal pronouns can unintentionally shift the reader’s focus onto the writer, pulling their focus away from the topic at hand.

Personal pronouns may also make your work seem less objective.

One of the most challenging parts of essay writing is learning which words to avoid and how to avoid them. Fortunately, following a few simple tricks, you can master the English Language and write like a pro in no time.

Alternatives To Using Personal Pronouns

How to not use “I” in a paper? What are the alternatives? There are many ways to avoid the use of personal pronouns in academic writing. By shifting your word choice and sentence structure, you can keep the overall meaning of your sentences while re-shaping your tone.

Utilize Passive Voice

In conventional writing, students are taught to avoid the passive voice as much as possible, but it can be an excellent way to avoid first-person pronouns in academic writing.

You can use the passive voice to avoid using pronouns. Take this sentence, for example:

“ We used 150 ml of HCl for the experiment.”

Instead of using “we” and the active voice, you can use a passive voice without a pronoun. The sentence above becomes:

“150 ml of HCl were used for the experiment.”

Using the passive voice removes your team from the experiment and makes your work sound more objective.

Take a Third-Person Perspective

Another answer to “how to avoid using ‘we’ in an essay?” is the use of a third-person perspective. Changing the perspective is a good way to take first-person pronouns out of a sentence. A third-person point of view will not use any first-person pronouns because the information is not given from the speaker’s perspective.

A third-person sentence is spoken entirely about the subject where the speaker is outside of the sentence.

Take a look at the sentence below:

“In this article you will learn about formal writing.”

The perspective in that sentence is second person, and it uses the personal pronoun “you.” You can change this sentence to sound more objective by using third-person pronouns:

“In this article the reader will learn about formal writing.”

The use of a third-person point of view makes the second sentence sound more academic and confident. Second-person pronouns, like those used in the first sentence, sound less formal and objective.

Be Specific With Word Choice

You can avoid first-personal pronouns by choosing your words carefully. Often, you may find that you are inserting unnecessary nouns into your work.

Take the following sentence as an example:

“ My research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

In this case, the first-person pronoun ‘my’ can be entirely cut out from the sentence. It then becomes:

“Research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

The second sentence is more succinct and sounds more authoritative without changing the sentence structure.

You should also make sure to watch out for the improper use of adverbs and nouns. Being careful with your word choice regarding nouns, adverbs, verbs, and adjectives can help mitigate your use of personal pronouns.

“They bravely started the French revolution in 1789.”

While this sentence might be fine in a story about the revolution, an essay or academic piece should only focus on the facts. The world ‘bravely’ is a good indicator that you are inserting unnecessary personal pronouns into your work.

We can revise this sentence into:

“The French revolution started in 1789.”

Avoid adverbs (adjectives that describe verbs), and you will find that you avoid personal pronouns by default.

Closing Thoughts

In academic writing, It is crucial to sound objective and focus on the topic. Using personal pronouns pulls the focus away from the subject and makes writing sound subjective.

Hopefully, this article has helped you learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

When working on any formal writing assignment, avoid personal pronouns and informal language as much as possible.

While getting the hang of academic writing, you will likely make some mistakes, so revising is vital. Always double-check for personal pronouns, plagiarism , spelling mistakes, and correctly cited pieces.

You can prevent and correct mistakes using a plagiarism checker at any time, completely for free.

Quetext is a platform that helps you with all those tasks. Check out all resources that are available to you today.

Sign Up for Quetext Today!

Click below to find a pricing plan that fits your needs.

You May Also Like

A Guide to Paraphrasing Poetry, With Examples

- Posted on July 12, 2024

Preparing Students for the Future: AI Literacy and Digital Citizenship

- Posted on July 5, 2024

How to Summarize a Paper, a Story, a Book, a Report or an Essay

- Posted on June 25, 2024 June 25, 2024

How to Use AI to Enhance Your Storytelling Process

- Posted on June 12, 2024

Essential Comma Rules for Business Emails

- Posted on June 7, 2024

How to Write Polished, Professional Emails With AI

- Posted on May 30, 2024

A Safer Learning Environment: The Impact of AI Detection on School Security

- Posted on May 17, 2024

Rethinking Academic Integrity Policies in the AI Era

- Posted on May 10, 2024 May 10, 2024

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

“I” & “We” in Academic Writing: Examples from 9,830 Studies

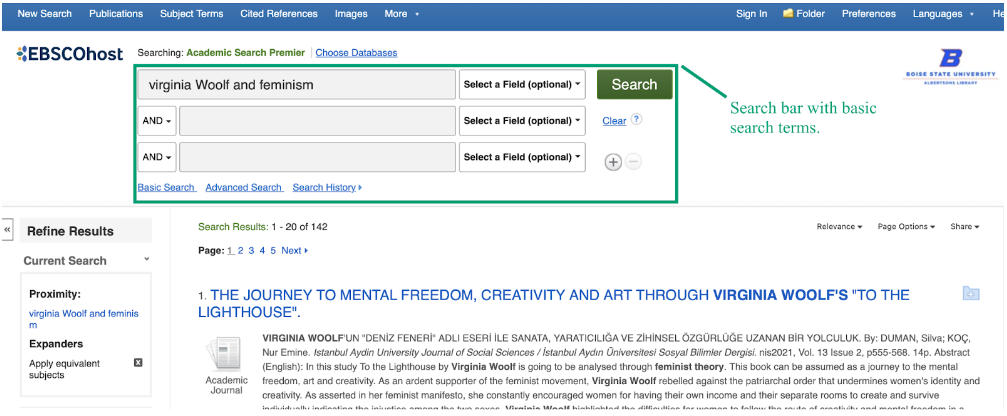

I analyzed a random sample of 9,830 full-text research papers, uploaded to PubMed Central between the years 2016 and 2021, in order to explore whether first-person pronouns are used in the scientific literature, and how?

I used the BioC API to download the data (see the References section below).

Popularity of first-person pronouns in the scientific literature

In our sample of 9,830 articles, 93.8% used the first-person pronouns “I” or “We”. The use of the pronoun “We” was a lot more prevalent than “I” (93.1% versus 13.9%, respectively).

In fact, even articles written by single authors were more likely to use “We” instead of “I”. Out of 9,830 articles, 39 were written by single authors: 8 of them used “I” and 19 used “We”.

The following table describes the use of first-person pronouns in each section of the research article:

| Article Section | Proportion of sections that used the pronoun “I” | Proportion of sections that used the pronoun “We” |

|---|---|---|

| Abstract | 0.01% | 22.71% |

| Introduction | 1.41% | 64.31% |

| Methods | 7.29% | 68.29% |

| Results | 6.28% | 52.36% |

| Discussion | 2.60% | 85.65% |

Use of the pronoun “I”

The pronoun “I” was mostly used in the Methods section (present in 7.29% of all methods sections in our sample).

For example:

“In general, I assumed a steady-state and a closed-population.” Link to the article on PubMed

“I” was also prevalent in the Results section (6.28%). But here, all of its uses were to quote participants’ answers, such as: