- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Business Education

- Business Law

- Business Policy and Strategy

- Entrepreneurship

- Human Resource Management

- Information Systems

- International Business

- Negotiations and Bargaining

- Operations Management

- Organization Theory

- Organizational Behavior

- Problem Solving and Creativity

- Research Methods

- Social Issues

- Technology and Innovation Management

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The resource-based view of the firm.

- Douglas Miller Douglas Miller Management and Global Business Department, Rutgers University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.4

- Published online: 26 March 2019

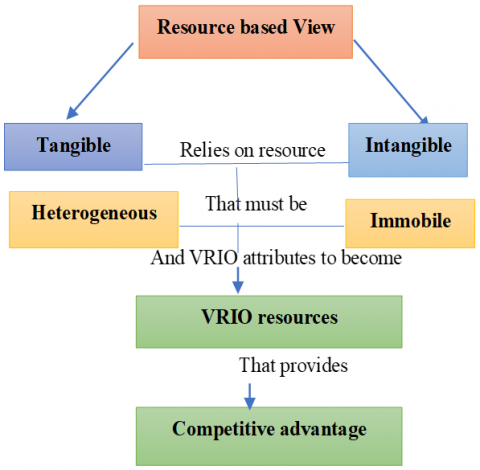

The Resource-Based View of the firm (RBV) is a set of related theories sharing the assumptions of resource heterogeneity and resource immobility across firms. In this view, a firm is a bundle of resources, capabilities, or routines which create value and cannot be easily imitated or appropriated by competitors due to isolating mechanisms. Grounded in the economic traditions of the “Chicago School” of economic efficiency, the “Austrian School” of economics, and organizational economics, the RBV comprises theories that explain the existence of (sustained) competitive advantage and of economic rents. Empirical research from this perspective addresses both firm performance and firm behavior at the level of business strategy (e.g., within-industry competition) and corporate strategy (e.g., acquisitions). Initially developed through a series of papers by several authors in the 1980s–1990s, major extensions and refinements of the RBV include the knowledge-based view of the firm (KBV), dynamic capabilities, and the relational view, which recognizes capabilities can be developed and shared through alliances between firms.

- resource-based view

- competitive advantage

- firm performance

- knowledge-based view

- sustained competitive advantage

- capabilities

- dynamic capabilities

First labeled by Wernerfelt ( 1984 ) and developed through a series of papers by various authors, the resource-based view of the firm (RBV) explains how firms achieve competitive advantage and economic rents through ownership and management of assets, capabilities, knowledge, and similar internal resources. Resource-based theory is complementary to more outward-looking theories of competitive advantage, most notably Porter’s ( 1980 ) Five Forces approach to analyzing industry structure. The RBV has been applied to derive hypotheses about numerous areas of research in strategic management and other disciplines, becoming a prevailing perspective employed in the field over recent decades. However, criticism of the RBV as untestable, incomplete, or even tautological has generated substantial debate. Major reviews of the theory (e.g., Mahoney & Pandian, 1992 ; Hoskisson, Hitt, Wan, & Yiu, 1999 ; Barney & Arikan, 2001 ; Lockett, Thompson, & Morgenstern, 2009 ; Kraaijenbrink, Spender, & Groen, 2010 ) and empirical RBV literature (e.g., Armstrong & Shimizu, 2007 ; Newbert, 2007 ; Crook, Ketchen, Combs, & Todd, 2008 ) inform this current essay. The remainder of this essay discusses key assumptions and definitions, the historical development of the core literature and extensions, empirical applications, critiques and responses, and suggestions for use by researchers.

Assumptions and Definitions

Industrial organization economics typically assumed that firms were undifferentiated suppliers responding to demand and thereby setting prices to clear markets. Thus, observed performance differences between firms over time were seen as stemming from structural differences in industries and economies, such as government regulation or barriers to entry. If one firm discovered a useful asset or activity, other firms could quickly copy it and compete away any economic profits in excess of a basic return to risk. By contrast, the resource-based view (RBV) assumes the following:

Resources are heterogeneous across firms.

Resources are imperfectly mobile across firms.

As explained by Wernerfelt ( 1984 ), just as firms might occupy different positions in product markets (Porter, 1980 ), they might acquire or build different resources aligned with those positions. Developing products that make best use of one’s existing resources, and developing new resources that best support a set of products are two sides of the same coin. Therefore, firm strategy is idiosyncratic and heavily path-dependent—past investments, activities, relationships, and knowledge create the conditions for subsequent decisions by a given firm.

Resources are “all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc. controlled by a firm that enable the firm to conceive of and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness” (Daft, 1983 ; as quoted by Barney, 1991 , p. 101).

While this early definition of resources listed “capabilities” as one example, later literature uses the term “resources” to indicate mostly assets rather than activities, described by nouns rather than verbs. Resources or routines (i.e., “regular and predictable behavioral patterns,” see Nelson & Winter, 1982 , p. 14) tend to be discussed as discrete inputs to be used in more complex or “higher-order” (Winter, 2000 ) activities called “capabilities.”

A capability “refers to the ability of an organization to perform a coordinated set of tasks, utilizing organizational resources, for the purpose of achieving a particular end result” (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003 , p. 999). These authors further distinguish between operational and dynamic capabilities:

An operational capability is “a high-level routine (or collection of routines) that, together with its implementing input flows, confers upon an organization’s management a set of decision options for producing significant outputs of a particular type” (Winter, 2000 , p. 983).

A dynamic capability is “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997 , p. 516); or to “build, integrate, or reconfigure operational capabilities” (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003 ) in any environment.

Despite these distinctions, the same logic applies to any of these conceptions of the internal components of a firm, whether these are called resources or capabilities, are considered as static or dynamic, reside in managers or other employees, or are distinguished in other ways. Assuming the component differs across firms, and rivals cannot easily copy the component, it is possible for firms competing in the same market (i.e., under the same structure) to have different performance, even in the long run, and different optimal strategies.

Clarifying earlier statements by various authors, Peteraf and Barney ( 2003 ), state that different versions of resource-based theory can explain either competitive advantage or economic rents, offering the following definitions:

An enterprise has Competitive Advantage if it is able to create more economic value than the marginal (breakeven) competitor in its product market. (Peteraf & Barney, 2003 , p. 314)

Economic rents are “returns to a factor in excess of its opportunity costs” and equivalent to the excess residual value (i.e., total economic value created less value delivered to the customer) of a focal firm relative to its break-even rival (Peteraf & Barney, 2003 , p. 315).

Competitive advantage relates closely to value creation, while economic rents take into account aspects of value appropriation, including what the firm has to pay in strategic factor markets (Barney, 1986a ) to acquire resources. Neither competitive advantage nor economic rents are defined as equal to profits or above-average returns. The extent to which indicators of financial performance such as market valuation, accounting returns, or growth reflect the fundamental dependent variables is an important discussion within the empirical literature on the RBV.

Development

Economic foundations.

Resource-based theory was built on diverse foundations in the underlying discipline of economics, reflecting the perspectives of the multiple authors who collectively developed the theory over several years. Primary influences were the “Chicago School” of economics, with its emphasis on efficiency; the “Austrian School” of economics, as interpreted through the lens of Edith Penrose’s Theory of the Growth of the Firm ( 1959 ); and organizational economics, particularly evolutionary economics (Nelson & Winter, 1982 ). As a comparison, Porter’s ( 1980 ) industry analysis derived directly from the approach of the “Harvard School” of industrial organization economics and its Structure-Conduct-Performance (S-C-P) paradigm (Mason, 1939 ; Bain, 1968 ; Caves, 1984 ). Whereas the S-C-P paradigm pointed to market power and barriers to competition as antitrust concerns, the “Chicago School” countered that a greater firm size and market share could arise instead from greater efficiency, in which case industry concentration was not necessarily harmful to social welfare. These efficiency arguments were brought into the strategic management literature by Demsetz ( 1973 ) and Rumelt ( 1982 ), among others, retaining the assumption that markets reach equilibrium (Lippman & Rumelt, 1982 ). Austrian economics (e.g., Von Hayek, 1948 ; Von Mises, 1949 ) does not share that assumption, focusing more on subjective, entrepreneurial alertness and judgment in an ever-changing business landscape. However, the links to Austrian economics were mediated through Penrose ( 1959 ). Her definitions of resources and their constraints, the distinction between resources themselves and the services that those resources provide, and the importance of managerial capabilities in teams are essential to the resource-based view (RBV) (Kor & Mahoney, 2004 ). Nevertheless, the potential for further refinements to the RBV using the assumptions and insights of Austrian economics was only appreciated later (Foss & Ishikawa, 2007 ; Foss, Klein, Kor, & Mahoney, 2008 ). Similarly, evolutionary economics, with its portrayal of industries as moving toward, yet never reaching, equilibrium, and its analysis at the level of routines, was incorporated into early RBV theory primarily through recognition that competitive advantage arises out of Schumpeterian “creative destruction” (Schumpeter, 1950 ; Barney 1986b ). However, later emphasis on knowledge resources and dynamic capabilities brought the influence of evolutionary economics to the forefront (Mahoney & Pandian, 1992 ; Teece et al., 1997 ).

Early Statements

Foundational writings in business policy included detailed accounts of how the internal workings of large corporations allowed them to thrive in difficult industries (e.g., Andrews, 1971 ). After heavy emphasis on industry characteristics in the early days of strategic management, Wernerfelt ( 1984 ) sought to restore the balance between internal and external analysis. He defined resources as the set of tangible and intangible assets semi-permanently attached to a firm. He proposed that the kind of resources subject to “resource position barriers” (Wernerfelt, 1984 , p. 173) can lead to high profits (akin to first-mover advantages; Lieberman & Montgomery, 1988 ); that strategy involves balancing the exploitation of existing resources and the development of new resources; that bundles of resources can be acquired in imperfect markets for entire businesses; and that this perspective leads to a new understanding of corporate diversification distinct from industry attractiveness and market power. Prahalad and Hamel ( 1990 ) further developed and popularized the idea that corporations should diversify on the basis of their “core competence.” Wernerfelt stated that “…these authors were single-handedly responsible for diffusion of the resource-based view into practice” (Wernerfelt, 1995 , p. 171).

Using a similar assumption of resource heterogeneity, Rumelt ( 1984 ) clarified several “isolating mechanisms” that prevent imitation of strategic resources, particularly “causal ambiguity” (Lippman & Rumelt, 1982 ), or uncertainty surrounding the link between any particular resource and the firm’s performance, which can lead to response lags. Barney ( 1986a ) further developed the concept of efficient strategic factor markets, using economic logic (Demsetz, 1973 ) to propose that gaining resources at an advantageous cost must come down to either differing expectations (preexisting heterogeneity, especially in information) or luck. Therefore, resources are only a source of economic rents when they are not fully tradeable. Barney ( 1986a ) concluded that internal analysis of one’s resources is a more likely path to economic rents than external analysis of industry conditions. Peteraf ( 1993 ) formalized the necessary conditions for resource-based economic rents as superior (heterogeneous) resources, ex post limits to competition (i.e., isolating mechanisms), imperfect resource mobility, and ex ante limits to competition (i.e., differing expectations under uncertainty). The mechanisms for imperfect resource mobility were explicated by Dierickx and Cool ( 1989 ). Along with causal ambiguity, they explain additional barriers to imitation: time compression diseconomies (related to learning curves; Lieberman, 1987 ), interconnected asset stocks (also called cospecialized assets; Teece, 1986 ), and asset mass efficiencies (e.g., R&D know-how creates absorptive capacity for further learning; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990 ). Dierickx & Cool ( 1989 ) also discuss the possibility of asset erosion and causal ambiguity about not only the function of resources, but also the process of their accumulation, pointing toward later, more dynamic variations of resource-based logic.

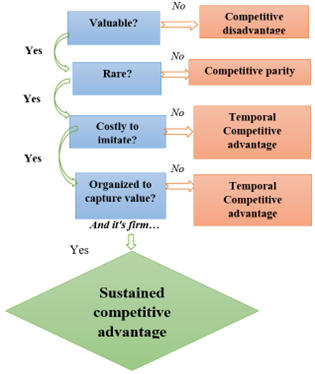

Next, a highly influential paper by Barney ( 1991 ) summarized the conditions for resource-based sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) through a concise framework: value, rareness, imperfect imitability, and non-substitutability (VRIN). This paper has been cited over 14,000 times (Web of Science). Barney later amended the framework to combine imitability and substitutability, adding organization (VRIO) to exploit the resource as the fourth factor (Barney, 1995 ). A resource or capability which is valuable, but not rare, can only bring the firm to competitive parity, at best. Value and rareness, with appropriate organization, can yield temporary competitive advantage. But only if all four conditions are met can the firm generate SCA from its resources. Barney’s ( 1991 ) framework brought together the earlier insights from multiple authors, clearly linking barriers to imitation (i.e., isolating mechanisms [Peteraf, 1993 ]) with sustainable competitive advantage. Other typologies (e.g., Black & Boal, 1994 ), descriptions of resource characteristics (e.g., Amit & Schoemaker, 1993 ; Grant, 1991 ), and clarifications of how the RBV relates to economic theories of the firm (e.g., Conner, 1991 ) further enriched this approach.

Major Extensions

As with the RBV in general, the development of the “knowledge-based view” (KBV) came through contributions from several authors. Building on Polanyi’s ( 1966 ) distinction between codified and tacit knowledge, Kogut and Zander ( 1992 ) describe the firm as a knowledge-bearing entity which acts as a social community. Since the knowledge developed in the firm is partially tacit and usually socially complex, knowledge is the quintessential resource that meets the VRIO criteria. Zander and Kogut ( 1995 ) further explicated five dimensions of knowledge: codifiability, teachability, complexity, system dependence, and product observability. A key distinction within statements of the KBV is whether knowledge is constructed at the collective level (Spender, 1996 ) or exists at the individual level, requiring organizational learning and integration capabilities to support a strategy (Grant, 1996a ).

The literature on dynamic capabilities also highlights combinative capabilities (Kogut & Zander, 1992 ), while elaborating on other capabilities that can build or alter resources or operational capabilities, especially in environments with rapid change (Grant, 1996b ). Definitions and exemplars of dynamic capabilities differ somewhat across seminal papers by Teece et al. ( 1997 ), Eisenhardt and Martin ( 2000 ), and Winter ( 2003 ). Some of the dynamic capabilities literature emphasizes the dynamics of markets, which require firms to use such capabilities; while other literature emphasizes the endogenous change that such capabilities enable, even to the point of enacting the environment. However, the core logic is consistent, and fits well within the RBV. Firms develop dynamic capabilities over time in a path-dependent manner, and constantly employ them to update their resources and activities. The complexity of these capabilities makes it difficult for competitors to understand or imitate them.

The third major extension of the RBV explains that resources and capabilities can be jointly developed, controlled, and used by firms in cooperative relationships. This “relational view” maintains a focus on internal operations, but allows more than one firm to share those operations. Dyer and Singh ( 1998 ) theorize that inter-organizational competitive advantage can come from relationship-specific assets, routines for extensive knowledge exchange, complementary and scarce resources or capabilities, and governance mechanisms that reduce transaction costs. The relational view has provided a bridge for more sociological explanations to influence the RBV (e.g., Gulati, 1999 ). The approach is consistent with Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven’s ( 1996 ) resource-based explanation that alliance formation arises from the combination of strategic needs and social opportunities. A more comprehensive resource-based theory of strategic alliances is provided by Das and Teng ( 2000 ).

Empirical Applications

Scholars have employed the Resource-Based View (RBV) to study phenomena in business strategy, corporate strategy, and cooperative strategy. Here, I cite early papers on each topic. For single-business firms, some studies of sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) have considered tangible assets such as property or location (Miller & Shamsie, 1996 ). Greater emphasis has been placed on intangible assets, including knowledge and innovation gained through R&D (Henderson & Cockburn, 1994 ) and know-how in functions of manufacturing, marketing, or information technology (Brush & Artz, 1999 ; Li & Calantone, 1998 ). Human resources have been studied both in terms of HR systems and policies for the development of firm-specific human capital (Delaney & Huselid, 1996 ) and strategic leadership (Castanias & Helfat, 1991 ). For corporate strategy, resource-based logic has driven research on corporate diversification (Robins & Wiersema, 1995 ), mergers and acquisitions (Capron, 1999 ), restructuring and divestitures (Bergh, 1998 ), international diversification (Arora & Gambardella, 1997 ), and technological diversity (Miller, 2004 ). The study of relational resources has shed light on alliance formation (Mowery, Oxley, & Silverman, 1996 ), performance (Combs & Ketchen, 1999 ), and duration (Dussauge, Garrette, & Mitchell, 2000 ). Overall, a bibliometric analysis identified 42 core papers in the RBV, which were cited by 3,904 papers published between 1991 and 2001 (Acedo, Barroso, & Galan, 2006 ), and thousands more since 2001 .

Critiques and Responses

The resource-based view (RBV) has been criticized on the basis of various concerns. See Kraaijenbrink et al. ( 2010 ) and Lockett et al. ( 2009 ) for more extensive analysis.

Several points of criticism concern the nature of resources. The broad definitions of resources in early RBV papers have been criticized as overly inclusive (Priem & Butler, 2001 ). Further, if every firm’s resources are unique, then comparisons, let alone generalizations from large-sample statistical analysis are impossible (Gibbert, 2006 ). Also, the types of resources most likely to support sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) (i.e., knowledge, reputation, or complex internal processes) will be difficult for researchers to observe (Godfrey & Hill, 1995 ). Finally, managers may have limited ability to control the sources of heterogeneity or even to effect change on the basis of resource-based logic, given imperfect property rights and uncertainty (Coff, 1999 ; McGuinness & Morgan, 2000 ).

In response to these criticisms about the nature of resources, some authors have acknowledged that not everything can be a strategic (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993 ) or critical resource (Wernerfelt, 1989 ). Also, heterogeneity does not have to imply uniqueness: firms could differ based on some quality of a resource measured on a continuum. While some empirical tests reinterpret common variables as proxies for resources (e.g., R&D, which is an input to organizational learning, not a direct measure of knowledge), other literature employs archival, observational, or survey methodology to assess well-defined resources or capabilities in a given setting (e.g., Henderson & Cockburn, 1994 ; Miller & Shamsie, 1996 ; Makri, Hitt, & Lane, 2010 ; Rawley & Simcoe, 2010 ; Wu, 2013 ). The main admonition of RBV proponents in this regard has been to improve theory and empirics through operationalization of key terms (Rouse & Daellenbach, 2002 ). The extensive empirical literature using RBV logic gives evidence that scholars seem to be able to define resources in a meaningful way and measure them to some extent, and Prahalad and Hamel’s ( 1990 ) explanation of core competence was widely embraced by corporate executives.

Regarding the paper by Barney ( 1991 ) laying out the resource characteristics of value, rareness, imperfect imitability, and non-substitutability, the strongest critique has been about value. Priem and Butler ( 2001 ) contend that (the use of) a resource can only be valuable if an economic actor outside the firm desires to pay for it. Therefore, the definition of value is exogenous to the RBV. If the resource itself is static (its characteristics do not change over time), then a resource-based SCA is only possible if markets are relatively stable. Furthermore, Priem and Butler ( 2001 ), among others, argue, it is a tautology to define competitive advantage as the condition of implementing a rare value-creating strategy while theorizing that the resources that create competitive advantage are those that are valuable and rare.

The defense by Peteraf and Barney ( 2003 ) exemplifies several aspects of response to this critique. First, they clarify terms, such as competitive advantage, for which multiple definitions existed by different authors (Powell, 2001 ). Second, they explain that valuable resources do not necessarily lead to competitive advantage, but only create potential for it. Third, they draw on the “value-price-cost” framework (Anderson & Narus, 1998 ) to distinguish between value creation and appropriation. Barney ( 2001 ) acknowledges that value is exogenous to resource-based explanations, while Makadok ( 2001 ) attempts to break the tautology by suggesting value is only revealed after the resource is deployed in the market, and Kraaijenbrek et al. ( 2010 ) suggest that a more subjective and socially defined view of value would help.

Other critiques highlight the boundaries of resource-based theory. First, it is possible to state the core propositions of the RBV (e.g., Barney & Arikan, 2001 ) without explaining how resource heterogeneity arises. Therefore, while resource-based research may explore the emergence of heterogeneity, it is not inherent to the theory itself. Second, VRIO (valuable, rare, costly to imitate, and organizationally enabled) resources are not a necessary condition for SCA; lasting differences in firm profitability can exist due to industry or national economic structure. Even at the resource level of analysis, uncertainty and sunk costs (e.g., as in bidding on mineral rights) can generate SCA in a set of initially homogeneous firms (Foss & Knudsen, 2003 ). Third, competitive advantage is not a sufficient condition for economic rents or above-normal returns, due to the principle of equifinality (Ray, Barney, & Muhanna, 2004 ). Rivals may have distinct resources that yield similar improvements in efficiency, which would be a case of resource substitutability. Yet even if rivals have different sources and realizations of improved efficiency—for instance, lower raw-material costs versus economies of scale in production—they could each have a (sustained) competitive advantage but no difference in overall cost or profits. Thus, superior financial performance does not necessarily imply the presence of VRIO resources, nor does the presence of VRIO resources guarantee superior financial performance.

Scholars writing in the RBV tradition tend to see these issues as opportunities to combine resource-based logic with theory at other levels of analysis, such as individual creativity, team production, industry structure, technology evolution, or legal systems. Along with extensive consideration of firm performance (Armstrong & Shimizu, 2007 ), the empirical RBV literature seeks to explain or predict firm behavior which might also reflect these non-resource-level factors. In this way, a particular study might test one step in the chain of causality, such as from a unique historical circumstance to persistent superior efficiency or reputation, without trying to link that advantage to financial performance.

A few other calls for refinement to resource-based theorizing and testing have come from scholars seeking to develop the RBV. Dierickx and Cool ( 1989 ) clarify that strategic factor markets are incomplete, and resources accumulated internally over time are particularly good candidates to support SCA. The literature on dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997 ) recognizes the potential for change in both firm activities and industry conditions. Moreover, the capabilities literature highlights that complex bundles of resources, not standalone assets, are usually necessary to develop SCA (Newbert, 2008 ). Makadok ( 2001 ) distinguishes between resource-picking and capability-building and analyzes how they might interact in a single firm. Others explain the role of managers in resource recombination through activities of stabilizing, enriching, and pioneering (Sirmon, Hitt, & Ireland, 2007 ). Poor management can lead to erosion of capabilities or their imitation. Also, just as resource heterogeneity and immobility can lead to sustained advantage, it can also lead to long-term disadvantage; the converse of core competence (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990 ) is core rigidity, being locked in to resources with low value (Leonard-Barton, 1992 ).

Suggestions for Use

The resource-based view is best considered a “research program” (Lado, Boyd, Wright, & Kroll, 2006 ) or “metatheory” (Levitas & Ndofor, 2006 ) involving the core assumptions of resource heterogeneity and imperfect mobility, not a single theory or a paradigm. A resource-based theory can incorporate various additional assumptions, levels of analysis, or logic from complementary theories, and seek to explain or predict various outcomes. Thus, the persistence of the terminology “resource-based view” (RBV) rather than “resource-based theory” (RBT) reflects not only inertia in language, but also an appreciation of the rich ground which the core assumptions provide for research. There is no single resource-based theory, but many are possible. Based on the responses to critiques of the RBV and exemplary studies in the literature, paying attention to the following steps will help to ensure the development of sound and useful resource-based research.

First, define assumptions about decision-makers and their thought processes. Most of the RBV literature fits into Organizational Economics, recognizing bounded rationality, asymmetric information, transaction costs, and limitations to optimal contracting. The knowledge-based view (KBV) is more explicitly behavioral and process-oriented (Hoskisson et al., 1999 ), often eschewing any consideration of opportunism. Instead, KBV research highlights issues in replication or transfer of tacit knowledge and the possibility of satisficing in the process of knowledge search. Some variations of dynamic capabilities reasoning incorporate a stronger role for the subjective judgment of managers. For example, managers may have mental models or a “dominant logic” (Prahalad & Bettis, 1986 ) that they apply or adjust depending on their assessment of internal and external factors. Other assumptions about individual and group decision-making—common cognitive biases, the psychology of learning, creativity, negotiation—can provide microfoundations to strengthen resource-based theory.

Second, define the objective of the firm: temporary competitive advantage, sustainable competitive advantage, economic rents, survival, or some other conception of performance. What is an appropriate measure for the objective? If relative to competitors, how are competitors defined? If it is “long term,” then over what length of time should the performance be measured? Resource-based theory does not have to accept the standard business-school goal of maximizing shareholder value. Organizations with an express purpose of benefiting multiple stakeholders still need to compete, and can have resources or capabilities, as well as products, that differ from those of other organizations. Even if the theory is meant to explain strategic behavior, rather than performance, there must be an account of why that behavior would be selected, involving both behavioral assumptions and an objective.

Third, a closely related subject is the nature of economic equilibrium, or the lack of it. Are there barriers to entry or imitation that exist outside the firm’s own efforts? Do managers expect that if they build a strategy on a superior capability, the market will stay consistent enough for that strategy to work years later? Some theoretical treatments of resource-based logic using non-cooperative (e.g., Grahovac & Miller, 2009 ) or cooperative game theory (e.g., Adner & Zemsky, 2006 ; Lippman & Rumelt, 2003 ) clarify definitions, objectives, the structure of markets, and the nature of competition. While such parsimonious precision may not be possible for a large-scale empirical study, such a study can at least be internally consistent with a neoclassical, evolutionary, or subjectivist economic approach, or a more behavioral one.

Fourth, develop a theory for the particular context. Generalizability is not the ultimate goal of any single RBV study, because resources and their characteristics can only be clearly valued and measured in a particular setting. Thus, findings need to be aggregated and compared across settings to build the overall research program. Ultimately, research on intangible, inimitable resources requires process-based case studies, returning the field of strategic management to its roots. Thus, RBV research may be better approached from a critical realist or constructivist perspective than a positivist philosophy of science (Miller & Tsang, 2011 ; Mir & Watson, 2000 ; Tsang & Kwan, 1999 ). A theory of sustainable competitive advantage for the particular context could mean paying attention to operationalizing each part of VRIO (value, rareness, imitability and substitutability, and organization) and how those parts interact. For instance, value might derive from R&D to create a product feature favored by consumers, or from improved efficiency in manufacturing. This distinction has implications for imitability: the internal process may be more causally ambiguous, whereas the same product feature that increases willingness-to-pay might be achievable through a substitute capability. Further, if the industry is already an oligopoly because other resources are rare, the adoption of a resource with greater value-creation potential would induce rivals to be willing to pay more to imitate that resource, so value, rareness, and imitability are intrinsically tied (Grahovac & Miller, 2009 ). For small firms, organization may be primarily owner/manager attention to the capability, while for large firms, whether a resource is fully utilized depends more on organizational structure. Constructs and variables need not be generalizable across contexts. Note that the VRIO framework is multiplicative, not additive: all four parts must be satisfied for sustainability. However, reviews of the empirical RBV literature have generally found most papers focus on either value or imitability; rareness is implied by barriers to imitation (Crook et al., 2008 ), and organization is often assumed.

Fifth, evaluate endogeneity directly. The RBV explains that managers play an active role in selecting and using resources and capabilities, resulting in strong path-dependence. Therefore, any sample of firms with variation in a resource will not capture random assignment of resources to firms. To evaluate the relationship between the quantity or quality of a resource and firm performance (or other outcomes), one must take into account the likelihood of the firm having that resource (Masten, 1993 ). Since both resources themselves and the decision processes behind their accumulation are often unobservable, dealing with endogeneity is a primary challenge for empirical research in the RBV. Note that controlling for endogeneity through the use of longitudinal data and statistical methods (e.g., Heckman selection equations or propensity scores) is necessary not only to establish the direction of causality between constructs, but also to accurately assess the magnitude and sign of the correlations themselves. For instance, resource-based literature on diversification uses various techniques to evaluate both the possibility of endogeneity from feedback loops (i.e., better performance facilitating further diversification) and possible spurious relationships; questioning whether there is a significant performance effect of diversification at all, on average (e.g., Villalonga, 2004 ; Miller, 2006 ). In a related manner, Bayesian techniques allow researchers to evaluate each firm’s decision as unique, more fully incorporating known heterogeneity (e.g., Mackey, Barney, & Dotson, 2017 ). These techniques answer the question “What should a given firm do?” rather than “What should the average firm do?” Empirical studies in the RBV have moved away from simple regressions of performance on measures of resources, and toward systems of equations incorporating latent factors, self-selection, and instrumental variables to control for endogeneity.

Sixth, employ resource-based logic with other theories. Broadly speaking, the RBV is a firm-level theory. Thus, factors at other levels of analysis can create important contingencies in the relationships between resources/capabilities and competitive advantage or economic rents. Empirical research employing resource-based logic has incorporated national, industry, strategic group, dyad, network, and corporate parent levels of analysis. Early on, Amit and Schoemaker ( 1993 ) noted the importance of adjusting the performance variables in RBV studies for industry, and dummy variables for other levels of analysis are common. More interesting is research that develops the logic of how the internal and external factors interrelate. There are also levels of analysis within firms, such as teams, individuals, or various stakeholders. These micro levels of analysis particularly shed light on who appropriates the value created in a firm (e.g., Coff, 1999 ). Cooperative game theory is another approach by means of which to explain value appropriation, with economic actors defined at various levels of analysis (e.g., Adegbesan, 2009 ; Lippman & Rumelt, 2003 ). Another broad characterization of the RBV is that it explains what happens to resources and because of resources, but does not necessarily explain why a firm has those particular resources. One opportunity for new combinations of theory comes from the intersection of RBV with literature on entrepreneurship and creativity. Insights about the origin of resources can especially help to define what it means for a resource to be non-substitutable. Another opportunity is to link RBV logic with a specific theory of the firm. Gibbons ( 2005 ) formalizes four such theories based around transaction costs (with rent-seeking), property rights, incentive systems, and adaptation. In particular, the KBV meshes well with Transaction Cost Economics, since knowledge is difficult to trade without revealing it to another party (e.g., Argyres & Zenger, 2012 ; Silverman, 1999 ). Property rights theory fits with management of tangible resources (e.g., Kim & Mahoney, 2005 ), while dynamic capabilities align well with incentive systems and adaptation theories (e.g., Teece, 2007 ). Attempts to define the RBV (or KBV) as a theory of the firm itself (Conner, 1991 ; Conner & Prahalad, 1996 ; Grant, 1996a ) have not been widely accepted (e.g., Foss, 1996 ; Mahoney, 2001 ). Likewise, since strategic management is an eclectic field, it is unlikely that anyone will build a grand, unified theory of competitive advantage with resources as the foundation. Instead, it is possible that many different contributions will develop, adopting various theoretical perspectives in conjunction with the core assumptions and insights of the RBV.

Further Reading

- Armstrong, C. E. , & Shimizu, K. (2007). A review of approaches to empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management , 33 , 959–986.

- Barney, J. B. (1986a). Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management Science , 32 (10), 1231–1241.

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management , 17 , 99–120.

- Barney, J. B. , & Arikan, A. M. (2001). The resource-based view: Origins and implications. In M. A. Hitt , R. E. Freeman , & J. S. Harrison (Eds.), The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management (pp. 124–188). Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell.

- Dyer, J. , & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of inter-organizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review , 23 (4), 660–679.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. , & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal , 21 (10–11) (Special Issue), 1105–1121.

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal , 17 (Winter Special Issue), 109–122.

- Helfat, C. E. , & Peteraf, M. A. (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal , 24 , 997–1010.

- Kraaijenbrink, J. , Spender, J.-C. , & Groen, A. J. (2010). The resource-based view: A review and assessment of its critiques. Journal of Management , 36 (1), 349–372.

- Lippman, S. A. , & Rumelt, R. P. (1982). Uncertain imitability: An analysis of interfirm differences in efficiency under competition. The Bell Journal of Economics , 13 (2), 418–438.

- Lockett, A. , Thompson, S. , & Morgenstern, U. (2009). The development of the resource-based view of the firm: A critical appraisal. International Journal of Management Reviews , 11 , 9–28.

- Mahoney, J. T. , & Pandian, J. R. (1992). The resource-based view within the conversation of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal , 13 , 363–380.

- Makadok, R. (2001). Toward a synthesis of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views of rent creation. Strategic Management Journal , 22 (5), 387–401.

- Newbert, S. L. (2007). Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal , 28 , 121–146.

- Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal , 14 (3), 179–191.

- Peteraf, M. A. , & Barney, J. B. (2003). Unraveling the resource-based tangle. Managerial and Decision Economics , 24 , 309–323.

- Prahalad, C. K. , & Hamel, G. (1990). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review , 68 (3), 79–91.

- Priem, R. L. , & Butler, J. E. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Academy of Management Review , 26 (1), 22–40.

- Spender, J. C. (1996). Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal , 17 (Winter Special Issue), 109–122.

- Teece, D. J. , Pisano, G. , & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal , 18 (7), 509–533.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 5 (2), 171–180.

- Winter, S. G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal , 24 (October Special Issue), 991–995.

- Acedo, F. J. , Barroso, C. , & Galan, J. L. (2006). The resource-based theory: Dissemination and main trends. Strategic Management Journal , 27 , 621–636.

- Adegbesan, J. A. (2009). On the origins of competitive advantage: Strategic factor markets and heterogeneous resource complementarity. Academy of Management Review , 34 (3), 463–475.

- Adner, R. , & Zemsky, P. (2006). A demand-based perspective on sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal , 27 (3), 215–239.

- Amit, R. , & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal , 14 , 33–46.

- Anderson, J. C. , & Narus, J. A. (1998). Business marketing: Understand what customers value. Harvard Business Review , 76 (6), 53–65.

- Andrews, K. (1971). The concepts of corporate strategy . Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

- Argyres, N. S. , & Zenger, T. R. (2012). Capabilities, transaction costs, and firm boundaries. Organization Science , 23 (6), 1643–1657.

- Arora, A. , & Gambardella, A. (1997). Domestic markets and international competitiveness: Generic and product-specific competencies in the engineering sector. Strategic Management Journal , 18 (Special Summer Issue), 53–74.

- Bain, J. S. (1968). Industrial organization (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Barney, J. B. (1986b). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review , 11 , 656–665.

- Barney, J. B. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. The Academy of Management Executive , 9 (4), 49–61.

- Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review , 26 (1), 41–56.

- Barney, J. B. , & Arikan, A. M. (2001). The resource-based view: Origins and implications. In M. A. Hitt , R. E. Freeman , & J. S. Harrison (Eds.). The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management (pp. 124–188). Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell.

- Black, J. A. , & Boal, K. B. (1994). Strategic resources: Traits, configurations and paths to sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal , 15 (Special Issue), 131–148.

- Bergh, D. D. (1998). Product-market uncertainty, portfolio restructuring, and performance: An information-processing and resource-based view. Journal of Management , 24 (2), 135–155.

- Brush, T. H. , & Artz, K. W. (1999). Toward a contingent resource-based theory: The impact of information asymmetry on the value of capabilities in veterinary medicine. Strategic Management Journal , 20 (3), 223–250.

- Capron, L. (1999). The long-term performance of horizontal acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal , 20 (11), 987–1018.

- Castanias, R. P. , & Helfat, C. E. (1991). Managerial resources and rents. Journal of Management , 17 (1), 155–171.

- Caves, R. E. (1984). Economic analysis and the quest for competitive advantage. The American Economic Review , 74 (2), 127–132.

- Coff, R. W. (1999). When competitive advantage doesn’t lead to performance: The resource-based view and stakeholder bargaining power. Organization Science , 10 (2), 119–133.

- Cohen, W. M. , & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly , 35 , 128–152.

- Combs, J. G. , & Ketchen, D. J., Jr. (1999). Explaining interfirm cooperation and performance: Toward a reconciliation of predictions from the resource-based view and organizational economics. Strategic Management Journal , 20 (9), 867–888.

- Conner, K. R. (1991). A historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organization economics: Do we have a new theory of the firm? Journal of Management , 17 (1), 121–154.

- Conner, K. R. , & Prahalad, C. K. (1996). A resource-based theory of the firm: Knowledge versus opportunism. Organization Science , 7 (5), 477–501.

- Crook, T. R. , Ketchen Jr., D. J. , Combs, J. G. , & Todd, S. Y. (2008). Strategic resources and performance: A meta-analysis. Strategic Management Journal , 29 (11), 1141–1154.

- Daft, R. (1983). Organization theory and design . New York, NY: West.

- Das, T. K. , & Teng, B. S. (2000). A resource-based theory of strategic alliances. Journal of Management , 26 (1), 31–61.

- Delaney, J. T. , & Huselid, M. A. (1996). The impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal , 39 (4), 949–969.

- Demsetz, H. (1973). Industry structure, market rivalry, and public policy. Journal of Law and Economics , 16 , 1–9.

- Dierickx, I. , & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science , 35 (12), 1504–1511.

- Dussauge, P. , Garrette, B. , & Mitchell, W. (2000). Learning from competing partners: Outcomes and durations of scale and link alliances in Europe, North America and Asia. Strategic Management Journal , 21 (2), 99–126.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. , & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal , Special Issue 21 (10–11), 1105–1121.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. , & Schoonhoven, C. B. (1996). Resource-based view of strategic alliance formation: Strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms. Organization Science , 7 (2), 136–150.

- Foss, N. J. (1996). Knowledge-based approaches to the theory of the firm: Some critical comments. Organization Science , 7 , 470–476.

- Foss, N. J. , & Ishikawa, I. (2007). Towards a dynamic resource-based view: Insights from Austrian capital and entrepreneurship theory. Organization Studies , 28 , 749–772.

- Foss, N. J. , Klein, P. G. , Kor, Y. Y. , & Mahoney, J. T. (2008). Entrepreneurship, subjectivism, and the resource-based view: Toward a new synthesis. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal , 2 , 73–94.

- Foss, N. J. , & Knudsen, T. (2003). The resource-based tangle: Towards a sustainable explanation of competitive advantage. Managerial and Decision Economics , 24 , 291–307.

- Gibbert, M. (2006). Generalizing about uniqueness: An essay on an apparent paradox in the resource-based view. Journal of Management Inquiry , 15 , 124–134.

- Gibbons, R. (2005). Four formal(izable) theories of the firm? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization , 58 , 200–245.

- Godfrey, P. C. , & Hill, C. W. L. (1995). The problem of unobservables in strategic management research. Strategic Management Journal , 16 (7), 519–533.

- Grahovac, J. , & Miller, D. J. (2009). Competitive advantage and performance: The impact of value creation and costliness of imitation. Strategic Management Journal , 30 (11), 1192–1212.

- Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive Advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review , 33 (3), 114–135.

- Grant, R. M. (1996a). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal , 17 (Winter Special Issue), 109–122.

- Grant, R. M. (1996b). Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science , 7 , 375–387.

- Gulati, R. (1999). Network location and learning: The influence of network resources and firm capabilities on alliance formation. Strategic Management Journal , 20 (5), 397–420.

- Helfat, C. E. , & Peteraf, M. A. (2003). The dynamic resource-based View: Capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal , 24 , 997–1010.

- Henderson, R. , & Cockburn, I. (1994). Measuring competence? Exploring firm effects in pharmaceutical research. Strategic Management Journal , 15 , 63–84.

- Hitt, M. A. , Hoskisson, R. E. , & Kim, H. (1997). International diversifications: Effects on innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal , 40 , 767–798.

- Hoskisson, R. E. , Hitt, M. A. , Wan, W. P. , & Yiu, D. (1999). Theory and research in strategic management: Swings of a pendulum. Journal of Management , 25 (3), 417–456.

- Kim, J. , & Mahoney, J. T. (2005). Property rights theory, transaction costs theory, and agency theory: An organizational economics approach to strategic management. Managerial and Decision Economics , 26 (4), 223–242.

- Kogut, B. , & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science , 3 (3), 383–397.

- Kor, Y. Y. , & Mahoney, J. T. (2004). Edith Penrose’s (1959) contributions to the resource-based view of strategic management. Journal of Management Studies , 41 (1), 183–191.

- Lado, A. A. , Boyd, N. G. , Wright, P. , & Kroll, M. (2006). Paradox and theorizing within the resource-based view. Academy of Management Review , 31 (1), 115–131.

- Leiblein, M. J. , & Miller, D. J. (2003). An empirical examination of transaction- and firm-level influences on the vertical boundaries of the firm. Strategic Management Journal , 24 (9), 839–859.

- Leonard-Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal , 13 (Special Issue), 111–125.

- Levitas, E. , & Ndofor, H. A. (2006). What to do with the resource-based view: A few suggestions for what ails the RBV that supporters and opponents might accept. Journal of Management Inquiry , 15 , 135–144.

- Li, T. , & Calantone, R. J. (1998). The impact of market knowledge competence on new product advantage: Conceptualization and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing , 62 (4), 3–29.

- Lieberman, M. B. (1987). The learning curve, diffusion, and competitive strategy. Strategic Management Journal , 8 (5), 441–452.

- Lieberman, M. B. , & Montgomery, D. B. (1988). First‐mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal , 9 (S1), 41–58.

- Lippman, S. A. , & Rumelt, R. P. (2003). A bargaining perspective on resource advantage. Strategic Management Journal , 24 (11), 1069–1086.

- Mackey, T. B. , Barney, J. A. , & Dotson, J. P. (2017). Corporate diversification and the value of individual firms: A Bayesian approach. Strategic Management Journal , 38 (2), 322–341.

- Mahoney, J. T. (2001). A resource-based theory of sustainable rents. Journal of Management , 27 (6), 651–660.

- Makri, M. , Hitt, M. A. , & Lane, P. J. (2010). Complementary technologies, knowledge relatedness, and invention outcomes in high technology mergers and acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal , 31 , 602–628.

- Mason, E. S. (1939). Price and production policies of large scale enterprises. American Economic Review , 29 , 61–74.

- Masten, S. (1993). Transaction costs, mistakes and performance: Assessing the importance of governance. Managerial and Decision Economics , 14 , 119–129.

- McGuinness, T. , & Morgan, R. E. (2000). Strategy, dynamic capabilities and complex science: Management rhetoric vs. reality. Strategic Change , 9 (4), 209–220.

- Miller, D. , & Shamsie, J. (1996). The resource-based view of the firm in two environments: The Hollywood film studios from 1936–1965. Academy of Management Journal , 39 , 519–543.

- Miller, D. J. (2004). Firms’ technological resources and the performance effects of diversification: A longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal , 25 (11), 1097–1119.

- Miller, D. J. (2006). Technological diversity, related diversification, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal , 27 (7), 601–619.

- Miller, K. D. , & Tsang, E. W. (2011). Testing management theories: Critical realist philosophy and research methods. Strategic Management Journal , 32 (2), 139–158.

- Mir, R. , & Watson, A. (2000). Strategic management and the philosophy of science: The case for a constructivist methodology. Strategic Management Journal , 21 (9), 941–953.

- Mowery, D. C. , Oxley, J. E. , & Silverman, B. S. (1996). Strategic alliances and interfirm knowledge transfer. Strategic Management Journal , 17 (S2), 77–91.

- Nelson, R. , & Winter, S. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Newbert, S. L. (2008). Value, rareness, competitive advantage, and performance: A conceptual-level empirical investigation of the resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal , 29 , 745–768.

- Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm . New York, NY: Wiley.

- Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension . London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy . New York, NY: Free Press.

- Powell, T. C. (2001). Competitive advantage: Logical and philosophical considerations. Strategic Management Journal , 22 , 875–888.

- Prahalad, C. K. , & Bettis, R. (1986). The dominant logic: A new linkage between diversity and performance. Strategic Management Journal , 7 , 485–501.

- Rawley, E. , & Simcoe, T. S. (2010). Diversification, diseconomies of scope, and vertical contracting: Evidence from the taxicab industry. Management Science , 56 (9), 1534–1550.

- Ray, G. , Barney, J. B. , & Muhanna, W. A. (2004). Capabilities, business processes, and competitive advantage: Choosing the dependent variable in empirical tests of the resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal , 25 (1), 23–37.

- Robins, J. , & Wiersema, M. F. (1995). A resource-based approach to the multibusiness firm: Empirical analysis of portfolio interrelationships and corporate financial performance. Strategic Management Journal , 16 , 277–299.

- Rouse, M. J. , & Daellenbach, U. S. (2002). More thinking on research methods for the resource-based perspective. Strategic Management Journal , 23 (10), 963–967.

- Rumelt, R. P. (1982). Diversification strategy and profitability. Strategic Management Journal , 3 (4), 359–369.

- Rumelt, R. P. (1984). Toward a strategic theory of the firm. In R. Lamb (Ed.), Competitive strategic management (pp. 556–570). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1950). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy . New York, NY: Harper and Brothers.

- Silverman, B. S. (1999). Technological resources and the direction of corporate diversification: Toward an integration of the resource-based view and transaction cost economics. Management Science , 45 (8), 1109–1124.

- Sirmon, D. G. , Hitt, M. A. , & Ireland, R. D. (2007). Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Academy of Management Review , 32 , 273–292.

- Teece, D. J. (1986). Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy , 15 (6), 285–305.

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal , 28 (13), 1319–1350.

- Tsang, E. W. , & Kwan, K. M. (1999). Replication and theory development in organizational science: A critical realist perspective. Academy of Management Review , 24 (4), 759–780.

- Villalonga, B. (2004). Does diversification cause the “diversification discount”? Financial Management , 33 , 5–27.

- Von Hayek, F. A. (1948). Individualism and economic order . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Von Mises, L. (1949). Human action . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Weigelt, C. B. , & Miller, D. J. (2013). Implications of internal organizational structure for firm boundaries. Strategic Management Journal , 34 (12), 1411–1434.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal , 5(2), 171–180.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1989). From critical resources to corporate strategy. Journal of General Management , 14 (3), 4–12.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1995). The resource‐based view of the firm: Ten years after. Strategic Management Journal , 16 (3), 171–174.

- Winter, S. G. (2000). The satisficing principle in capability learning. Strategic Management Journal , 21 (10–11), 981–996.

- Wu, B. (2013). Opportunity costs, industry dynamics, and corporate diversification: Evidence from the cardiovascular medical device industry, 1976–2004. Strategic Management Journal , 34 (11), 1265–1287.

- Zander, U. , & Kogut, B. (1995). Knowledge and the speed of the transfer and imitation of organizational capabilities: An empirical test. Organization Science , 6 (1), 76–92.

Related Articles

- Corporate or Product Diversification

- Appropriation of Value from Competitive Advantages

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Business and Management. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 01 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Character limit 500 /500

Resource-Based View Theory

- First Online: 01 January 2011

Cite this chapter

- Mahdieh Taher 4

Part of the book series: Integrated Series in Information Systems ((ISIS,volume 28))

9844 Accesses

4 Citations

Resource-based view (RBV) theory has been discussed in strategic management and Information Systems (IS) for many years. Although many extensions and elaborations of RBV have been published over the years, to a considerable extent, most of them have identified critical resources and investigated the impact of resources on competitive advantage and/or other organization issues such as corporative environmental performance, profitability, and strategic alliance. Nevertheless, the orchestration of resources seems to influence these results. There still remains the issue of resource relations in an organization, the internal interaction of resources, especially IT resources with non-IT resources and the process of IT resource interaction with other resources within a firm which we have called resource impressionability. To fill these gaps in IS literature, we propose the new concept of resource orchestration in order to answer resource impressionability issues during implementation of IT projects.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abbreviations

Competitive advantage

Information system

Information technology

Resource-based view

Sustained competitive advantage

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14 (1), 33–46.

Article Google Scholar

Andreu, R., & Ciborra, C. (1996). Organizational learning and core capabilities development: The role of IT. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 5 (2), 111–127.

Apel, W. (Revised and Enlarged edition (January 1968)). Harvard dictionary of music (2nd ed.). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Google Scholar

Barney, J. B. (1986a). Strategic factor markets: expectations, luck and business strategy. Management Science, 32 (10), 1231–1241.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99–120.

Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26 (1), 41–56.

Barney, J., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2001). The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. Journal of Management, 27 , 625–641.

Bharadwaj, A. S. (2000). A resource-based perspective on information technology capability and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 24 (1), 169–196.

Bharadwaj, A. S., Sambamurthy, V., & Zmud, R. W. (1998). IT capabilities: Theoretical perspectives and empirical operationalization. In R. Hirschheim, M. Newman, & J. I. DeGross (Eds.), Proceedings of the 19th international conference on information systems (pp. 378–385), Helsinki.

Birkinshaw, J., & Goddard, J. (2009). What is your management model? MIT Sloan Management Review, 50 (2), 81–90.

Black, J. A., & Boal, K. B. (1994). Strategic resources: Traits, configurations and paths to sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 15 (Summer), 131–148.

Bowman, C. (2001). “Value” in the resource-based view of the firm: A contribution to the debate. Academy of Management Review, 26 (4), 501–502.

Capron, L., & Hulland, J. (1999). Redeployment of brands, sales forces, and general marketing management expertise following horizontal acquisitions: A resource-based view. Journal of Marketing, 63 (April), 41–54.

Clemons, E. K., & Row, M. C. (1991). Sustaining IT advantage: The role of structural differences. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 15 (3), 275–292.

Collis, D. J. (1994). Research note: How valuable are organizational capabilities? Strategic Management Journal, 15 (Winter Special Issue), 143–152.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B.-S. (1998). Resource and risk management in the strategic alliance making process. Journal of Management, 24 (1), 21–24.

Day, G. S. (1994). The capabilites of market-driven organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58 (4), 37–52.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21 (10–11), 1105–1121.

Ethiraj, S. K., Kale, P., Krishnan, M. S., & Singh, J. V. (2005). Where do capabilities come from and how do they matter? A study in the software services industry. Strategic Management Journal, 26 (1), 25–45.

Gavetti, G. (2005). Cognition and hierarchy: Rethinking the microfoundations of capabilities’ development. Organization Science, 16 (6), 599–617.

Goold, M., & Campbell, A. (1998). Desperately seeking synergy, harvard business review, September-October, 131–143.

Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Information Systems Management, 18 (1), 185–214.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33 (3), 114–135.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7 (4), 375–387.

Helfat, C. E. (1997). Know-how and asset complementarity and dynamic capability accumulation: The case of R&D. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (5), 339–360.

Helfat, C. E., & Raubitschek, R. S. (2000). Product sequencing: Co-evolution of knowledge, capabilities and products. Strategic Management Journal, 21 (10–11), 961–979.

Hoopes, D. G., Madsen, T. L., & Walker, G. (2003). Guest editors’ introduction to the special issue: Why is there a resource-based view? Toward a theory of competitive heterogeneity. Strategic Management Journal, 24 (8), 889–902.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1998). An information company in Mexico: Extending the resource-based view of the firm to a developing country context. Information Systems Research, 9 (4), 342–361.

Leonard-Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13 (8), 111–125.

Mahoney, J. T., & Pandian, R. (1992). The resource-based view within the conversation of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 13 , 363–380.

Makadok, R. (2001). Toward a synthesis of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views of rent creation. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (5), 387–402.

Mata, F. J., Fuerst, W. L., & Barney, J. B. (1995). Information technology and sustained competitive advantage: A resource-based analysis. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 19 (4), 487–505.

Melville, N., Kraemer, K., & Gurbaxani, V. (2004). Review: Information technology and organizational performance: An integrative model of it business value. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 28 (2), 283–322.

Montealegre, R. (2002). A process model of capability development: Lessons from the electronic commerce strategy at Bolsa de Valores de Guayaquil. Organization Science, 13 (5), 514–531.

Nelson, R., & Winter, S. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pavlou, P.A. (2002). The role of interorganizational coordination capabilities in new product development. In Proceedings of the 8th Americas conference on information systems (AMCIS) , 9–11 August (pp. 2565–2572), Dallas, Texas.

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm . London: Basil Blackwell.

Peppard, J., & Ward, J. (2004). Beyond strategic information systems: Towards an IS capability. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 13 (2), 167–194.

Piccoli, G., Feeny, D., & Ives, B. (2002). Creating and sustaining IT-enabled competitive advantage . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Piccoli, G., & Ives, B. (2005). IT-dependent strategic initiatives and sustained competitive advantage: A review and synthesis of the literature. MIS Quarterly, 29 (4), 747–776.

Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage-creating and sustaining superior performance . New York: The Free Press. 1985.

Powell, T. C., & Dent-Micallef, A. (1997). Information technology as competitive advantage: The role of human, business, and technology resources. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (5), 375–405.

Ravichandran, T., & Lertwongsatien, C. (2002). Impact of information systems resources and capabilities on firm performance. In Proceesings of 23rd international conference on information systems (pp. 577–582).

Ray, G., Muhanna, W. A., & Barney, J. B. (2005). Information technology and the performance of the customer service process: A resource-based analysis. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 29 (4), 625–651.

Ross, J. W., Beath, C. M., & Goodhue, D. L. (1996). Develop long-term competitiveness through IT assets. Sloan Management Review, 38 (1), 31–42.

Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. (1997). A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 40 (3), 534–559.

Sambamurthy, V., Bharadwaj, A., & Grover, V. (2003). Shaping agility through digital options: Reconceptualizing the role of information technology in contemporary firms. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 27 (2), 237–263.

Sanchez, R. (2001). The dynamic capabilities school: Strategy as a collective learning process to develop distinctive competences. In H. W. Volberda & T. Elfring (Eds.), Rethinking strategy (pp. 143–157). London: Sage.

Santhanam, R., & Hartono, E. (2003). Issues in linking information technology capability to firm performance. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 21 (1), 125–153.

Stalk, G., Evans, P., & Shulman, L. E. (1992). Competing on capabilities: The new rules of corporate strategy. Harvard Business Review, 70 (2), 57–69.

Tan, C. W., Lim, E. T. K., Pan, S. L., & Chan, C. M. L. (2004). Enterprise system as an orchestrator of dynamic capability development: A case study of the IRAS and TechCo. In B. Kaplan, D. P. Truex, D. Wastell, A. T. Wood-Harper, & J. I. DeGross (Eds.), Information systems research: Relevant theory and informed practice (pp. 515–534). Norwell: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Tanriverdi, H. (2006). Performance effects of information technology synergies in multibusiness firms. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 30 (1), 57–77.

Teece, D., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7), 509–533.

Teo, T. S. H., & Ranganathan, C. (2004). Adopters and non-adopters of business-to-business electronic commerce in Singapore. Information Management, 42 (1), 89–102.

Tippins, M. J., & Sohi, R. S. (2003). IT competency and firm performance: Is organizational learning a missing link? Strategic Management Journal, 24 (8), 745–761.

Wade, M., & Hulland, J. (2004). Review: The resource-based view and information systems research: Review, extension, and suggestions for future research. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 28 (1), 107–142.

Wheeler, B. (2002). The net-enabled business innovation cycle: A dynamic capabilities theory for harnessing it to create customer value. Information Systems Research, 13 (2), 147–150.

Winter, S. G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24 (10), 991–995.

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). The net-enabled business innovation cycle and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Information Systems Research, 13 (2), 147–150.

Zhu, K. (2004). The complementarity of information technology infrastructure and e-commerce capability: A resource-based assessment of their business value. Journal of Management Information Systems, 21 (1), 175–211.

Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization Science, 13 (3), 339–351.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Information Systems, School of Computing, National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore, 117543, Singapore

Mahdieh Taher

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mahdieh Taher .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

, School of Business and Economics, Swansea University, Singleton Park, Swansea, SA2 8PP, United Kingdom

Yogesh K. Dwivedi

IMD, Ch. de Bellerive 23, Lausanne, 1001, Switzerland

Michael R. Wade

Principia College, Maybeck Place 1, Elsah, 62028, Illinois, USA

Scott L. Schneberger

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Taher, M. (2012). Resource-Based View Theory. In: Dwivedi, Y., Wade, M., Schneberger, S. (eds) Information Systems Theory. Integrated Series in Information Systems, vol 28. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6108-2_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6108-2_8

Published : 01 August 2011

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-6107-5

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-6108-2

eBook Packages : Business and Economics Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Search form

A systematic review of resource-based view and dynamic capabilities of firms and future research avenues.

© 2023 IIETA. This article is published by IIETA and is licensed under the CC BY 4.0 license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

OPEN ACCESS

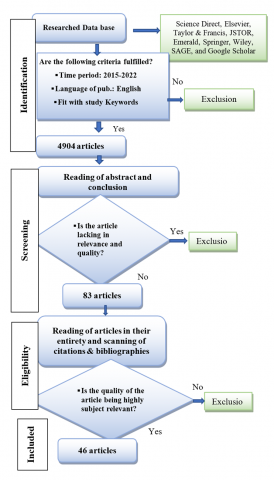

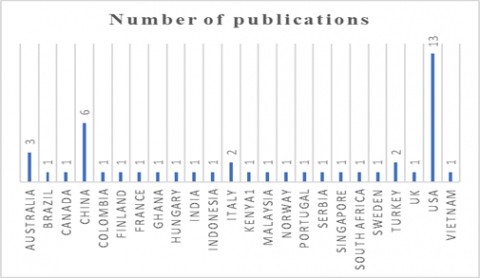

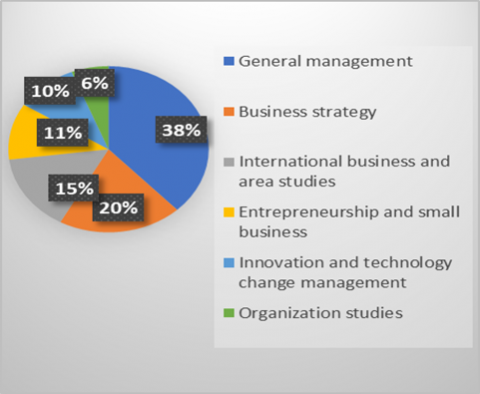

This study synthesizes empirical research on Resource-Based Views (RBVs) and Dynamic Capabilities (DCs) of firms across various sectors, aiming to create a comprehensive understanding of these topics. Utilizing a systematic literature review methodology, 46 articles that met stringent screening criteria were analyzed, with key information extracted. These articles, sourced from databases such as Science Direct, Elsevier, JSTOR, and Google Scholar, centered on studies related to RBV and DCs. Thematic content analysis was employed to distill the primary research focus on RBV and DC. Search terms included "resource-based view," "firm resource approach," "dynamic capabilities," "firm capabilities," and "organizational capabilities." Inclusion criteria were based on search boundaries, publication date, language, and search strings, while exclusion criteria included relevance, quality, and duplication. The analysis yielded five major themes related to RBV (knowledge-based, human, physical, technological, and organizational resources) and four primary themes regarding DCs (marketing, operational, innovative, and alliance/integration capabilities). These themes were scrutinized to comprehend the current state of knowledge, identify research gaps, and suggest future research opportunities. The review reveals that while RBVs emphasize how a firm's resources contribute to its competitive advantage, DCs elucidate how firms can cultivate a competitive advantage in fluctuating environments. Areas underexplored in existing research, such as the types of resources influencing financial and non-financial performance, the measurement of a firm’s capabilities, and the critique of RBV, present potential avenues for future investigations.

resource-based view, dynamic capabilities, firms’ capabilities, resources, capabilities, systematic literature review

In today's dynamic and highly competitive environment, organizations should be active actors in the market and must be able to respond to environmental changes through their resources and capabilities [1]. Firms need to recognize and take advantage of resource opportunities and prevent potential threats to achieve a long-lasting competitive edge [2]. According to the resource-based view (RBV), a firm's ability to maintain competitiveness depends on its access to valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources [3]. The firm's ability to create or obtain these resources has an impact on its effectiveness, competitiveness, and profitability. The RBV emphasizes the organization's resources, capabilities, and competencies to identify ways to provide superior competitive advantages [4]. A firm can possess various resources and capabilities, and most of these capabilities are closely associated with improved performance [5, 6].

Capabilities are bundles of knowledge and skills that allow firms to plan their operations and utilize their resources [7]. Dynamic capabilities (DCs) are a perspective developed based on the RBV framework to describe how businesses can dynamically build-essential and unique resource qualities. To gain a competitive advantage, the organization must constantly integrate, reconfigure, renew, and create tangible and intangible resources in response to changing market conditions [8]. According to Zahra [9] DCs involve processes that are used to reorganize the resource base to respond to changing market conditions. DCs are the capacity of a firm to combine, develop, and reorganize its internal and external resources and competencies to respond to rapidly shifting business environments. RBV and DCs are crucial to gaining and maintaining a competitive advantage because they enable firms to rearrange their resources in response to changes in the external environment [10]. The competition between Samsung and Apple can be taken as a practical example to understand RBV and DCs. The two businesses compete against the same external market pressures and work in the same sector. However, because of the disparity in resource availability and DCs, the organizations achieve differing organizational performance.

Even though research on strategic management is increasingly focused on the relevance of RBV and DCs for the competitiveness of firms, a great number of publications on the subject over the last decade have caused fragmentation of knowledge, and as a result, various authors have criticized the concept as being difficult to operationalize if it is not systematically reviewed [11, 12]. This research aims to synthesize the current progress of research on RBV and DCs to address this fragmentation. We hope our systematic review will make important contributions both intellectually and empirically by identifying, assessing, and integrating the research findings to produce a summary of the most recent data to provide an evidence-based metaphor on the topic. Therefore, our review adds relevant value to existing knowledge of the topic and creates future research agendas for academics who are interested in exploring the topic.

This review was guided by the following research questions:

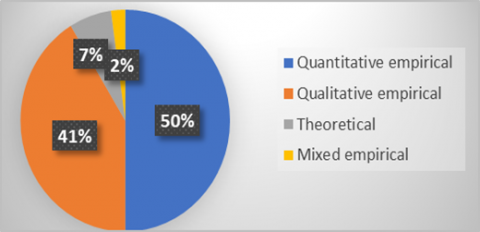

RQ1: What are the various research designs and methodologies that have been used in RBV and DC’s publications?

RQ2: What are the key themes and trends in the RBV and DCs literature, and how have they evolved over time?

RQ3: What are promising avenues for further RBV and DC research?

Based on the results of our review, the majority of studies agree that the RBV of the firm places more emphasis on gaining sustainable competitive advantage through VRIO resources, whereas the dynamic capabilities view places a greater emphasis on the question of competitive survival in response to quickly changing contemporary business conditions.