Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Webster Veterinary

Guide to Scholarly Articles

Getting started, what makes an article scholarly, why does this matter.

- Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles

- Types of Scholarly Articles

- Anatomy of Scholarly Articles

- Tips for Reading Scholarly Articles

Scholarship is a conversation.

That conversation is often found in the form of published materials such as books, essays, and articles. Here, we will focus on scholarly articles because scholarly articles often contain the most current scholarly conversation.

After reading through this guide on scholarly articles you will be able to identify and describe different types of scholarly articles. This will allow you to navigate the scholarly conversation more effectively which in turn will make your research more productive.

The distinguishing feature of a scholarly article is not that it is without errors; rather, a scholarly article is distinguished by a few characteristics which reduce the likelihood of errors. For our purposes, those characteristics are expert authors , peer-review , and citations .

- Expert Authors - Authority is constructed and contextual. In other words it is built through academic credentialing and lived experience. Scholarly articles are written by experts in their respective fields rather than generalists. Expertise often comes in the form of academic credentials. For example, an article about the spread of various diseases should be written by someone with credentials and experience in immunology or public health.

- Peer-review - Peer-review is the process whereby scholarly articles are vetted and improved. In this process an author submits an article to a journal for publication. However, before publication, an editor of the journal will send the article to other experts in the field to solicit their informed and professional opinions of it. These reviewers (sometimes called referees) will give the editor feedback regarding the quality of the article. Based on this process, articles may be published as is, published after specific changes are made, or not published at all.

- Citations - One of the key differences between scholarly articles and other kinds of articles is that the former contain citations and bibliographies. These citations allow the reader to follow up on the author's sources to verify or dispute the author's claim.

There is a well-known axiom that says "Garbage in, garbage out." In the context of research this means that the quality of your research output is dependent on the information sources that go into you own research. Generally speaking, the information found in scholarly articles is more reliable than information found elsewhere. It is important to identify scholarly articles and prioritize them in your own research.

- Next: Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2023 8:53 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/scholarly-articles

Evaluating Information Sources

- Evaluate Your Sources

- Publication Types and Bias

Structure of Scientific Papers

Reading a scholarly article, additional reading tips, for more information.

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Impact Factors and Citation Counts

- Predatory Publishing

Research papers generally follow a specific format. Here are the different parts of the scholarly article.

Abstract (Summary)

The abstract, generally written by the author(s) of the article, provides a concise summary of the whole article. Usually it highlights the focus, study results and conclusion(s) of the article.

Introduction (Why)

In this section, the authors introduce their topic, explain the purpose of the study, and present why it is important, unique or how it adds to existing knowledge in their field. Look for the author's hypothesis or thesis here.

Introduction - Literature Review (Who else)

Many scholarly articles include a summary of previous research or discussions published on this topic, called a "Literature Review". This section outlines what others have found and what questions still remain.

Methodology / Materials and Methods (How)

Find the details of how the study was performed in this section. There should be enough specifics so that you could repeat the study if you wanted.

Results (What happened)

This section includes the findings from the study. Look for the data and statistical results in the form of tables, charts, and graphs. Some papers include an analysis here.

Discussion / Analysis (What it means)

This section should tell you what the authors felt was significant about their results. The authors analyze their data and describe what they believe it means.

Conclusion (What was learned)

Here the authors offer their final thoughts and conclusions and may include: how the study addressed their hypothesis, how it contributes to the field, the strengths and weaknesses of the study, and recommendations for future research. Some papers combine the discussion and conclusion.

A scholarly paper can be difficult to read. Instead of reading straight through, try focusing on the different sections and asking specific questions at each point.

What is your research question?

When you select an article to read for a project or class, focus on your topic. Look for information in the article that is relevant to your research question.

Read the abstract first as it covers basics of the article. Questions to consider:

- What is this article about? What is the working hypothesis or thesis?

- Is this related to my question or area of research?

Second: Read the introduction and discussion/conclusion. These sections offer the main argument and hypothesis of the article. Questions to consider for the introduction:

- What do we already know about this topic and what is left to discover?

- What have other people done in regards to this topic?

- How is this research unique?

- Will this tell me anything new related to my research question?

Questions for the discussion and conclusion:

- What does the study mean and why is it important?

- What are the weaknesses in their argument?

- Is the conclusion valid?

Next: Read about the Methods/Methodology. If what you've read addresses your research question, this should be your next section. Questions to consider:

- How did the author do the research? Is it a qualitative or quantitative project?

- What data are the study based on?

- Could I repeat their work? Is all the information present in order to repeat it?

Finally: Read the Results and Analysis. Now read the details of this research. What did the researchers learn? If graphs and statistics are confusing, focus on the explanations around them. Questions to consider:

- What did the author find and how did they find it?

- Are the results presented in a factual and unbiased way?

- Does their analysis agree with the data presented?

- Is all the data present?

- What conclusions do you formulate from this data? (And does it match with the Author's conclusions?)

Review the References (anytime): These give credit to other scientists and researchers and show you the basis the authors used to develop their research. The list of references, or works cited, should include all of the materials the authors used in the article. The references list can be a good way to identify additional sources of information on the topic. Questions to ask:

- What other articles should I read?

- What other authors are respected in this field?

- What other research should I explore?

When you read these scholarly articles, remember that you will be writing based on what you read.

While you are Reading:

- Keep in mind your research question

- Focus on the information in the article relevant to your question (feel free to skim over other parts)

- Question everything you read - not everything is 100% true or performed effectively

- Think critically about what you read and seek to build your own arguments

- Read out of order! This isn't a mystery novel or movie, you want to start with the spoiler

- Use any keywords printed by the journals as further clues about the article

- Look up words you don't know

How to Take Notes on the Article

Try different ways, but use the one that fits you best. Below are some suggestions:

- Print the article and highlight, circle and otherwise mark while you read (for a PDF, you can use the highlight text feature in Adobe Reader)

- Take notes on the sections, for example in the margins (Adobe Reader offers pop-up sticky notes )

- Highlight only very important quotes or terms - or highlight potential quotes in a different color

- Summarize the main or key points

Reflect on what you have read - draw your own conclusions . As you read jot down questions that come to mind. These may be answered later on in the article or you may have found something that the authors did not consider. Here are a few questions that might be helpful:

- Have I taken time to understand all the terminology?

- Am I spending too much time on the less important parts of this article?

- Do I have any reason to question the credibility of this research?

- What specific problem does the research address and why is it important?

- How do these results relate to my research interests or to other works which I have read?

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article (Interactive tutorial) Andreas Orphanides, North Carolina State University Libraries, 2009

- How to Read an Article in a Scholarly Journal (Research Guide) Cayuga Community College Library, 2016

- How To Read a Scholarly Journal Article (YouTube Video) Tim Lockman, Kishwaukee College Library, 2012.

- How To Read a Scientific Paper (Interactive tutorial) Michael Fosmire, Purdue University Libraries, 2013. PDF

- How to Read a Scientific Paper (Online article) Science Buddies, 2012

- How to Read a Scientific Research Paper (Article) Durbin Jr., C. G. Respiratory Care, 2009

- The Illusion of Certainty and the Certainty of Illusion: A Caution when Reading Scientific Articles (Article) T. A. Lang, International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2011,

- Infographic: How to Read Scientific Papers Natalia Rodriguez, Elsevier, 2015

- Library Research Methods: Read & Evaluate Culinary Institute of America Library, 2016

- << Previous: Publication Types and Bias

- Next: Impact Factors and Citation Counts >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2024 1:17 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/evaluate

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

How to Read a Research Article: A Kind Guide for Non-Scientists

Posted January 11, 2023

By Boris Litvin

I. “ How Do You Even Read This?! ”

At last—you found it . A research article that, at first glance, can precisely answer your questions. After Googling for hours and swimming through comment sections, anecdotes, videos, and the occasional heavy debate, you’ve come across what looks like the Holy Grail. Fifteen pages whose beginning can be traced to years ago, when a team of top experts at a top university recruited countless participants who gave their time for a scientific study. Pages written by these top experts over the course of months, which were then reviewed by a panel of other top experts over the course of more months, and which you now feast your eyes upon. The title is confident. The reference section has dozens of entries. There are plenty of graphs and tables.

With a smile, you scroll through the article for a minute…and close the webpage with resignation. “ How do you even read this?! ”

Whether you’re looking for quality research about OCD, related disorders, or anything else in psychology—and whether it’s for yourself, a loved one, or a therapist—this feeling of confusion and giving up is sadly too common. You found a research article that’s relevant to your question, but as you read it, you may soon realize that this was not written with you in mind.

Unfortunately, research articles are written for scientists by other scientists in peer-reviewed reputable journals . These are not texts like novels, blog posts, or even articles in scientific magazines and websites. There is a different language, full of specific terminology, parentheses, and symbols. This lingo is used by scientists to quickly communicate relevant information and allow them to test the study on their own, challenge or agree with the findings, and use it to further understanding of OCD and related disorders in their own way. However, these scientists have spent years, if not decades, in academia, where understanding this lingo was taught and practiced from the start. Apart from the terminology, there are numbers, statistics, and Greek letters ( α , anyone?), which serve as the backbone of psychological research. These numbers and stats are ultimately the roots of this language, and all that terminology and formal verbiage become heavy flourishes that interpret these. What?!

To non-scientists, this is obviously frustrating. You may ask, “If these articles and studies are supposed to lead to a better understanding of OCD (or any psychological disorder), and inform treatment, and so on—shouldn’t they be accessible to all of us? Shouldn’t everyone be able to glance at them and gauge which course of action is best to treat their symptoms, or understand how a specific subtype of OCD works?” You may also ask, “If words in these articles are meant to interpret numbers and symbols and tests, why not just use simpler language? Statistics are complicated as it is!”

Scientists across all disciplines learn their lingo from early on; over time, it becomes internalized through reading tons of these articles and eventually writing their own. But all have found themselves in your shoes—as a student in an intro course receiving a 15-page print-out for homework (“I can definitely read this last minute…”) and then going into full-blown panic when they realize this reads like nothing they’ve seen before (“I finished War & Peace in 10th grade! Why is this so dense?!). Over time, they learn the tricks of the trade—what terminology means, what a Greek letter stands for, what numbers represent. Most importantly, they learn how to actually read a research paper—how to find what they need without reading the whole thing in linear order in a matter of minutes.

I started out as an overwhelmed student in an intro course, worked in labs, and contributed to a few research papers of my own. While I understand the terminology and am quite comfortable with reading a series of articles, I’m also mindful that most people can’t do that and would have to give up a solid amount of time by practicing this skill, going to classes, working as a researcher, and so on. So I’m writing this for anyone who wants to learn and know how to read a research article like the experts do. But before we dive in, please understand that this will require practice and comfort with some frustration before you can quickly skim these texts like an academic. It’s just like building a muscle or practicing a hobby.

II. The Structure of a Research Article

A research article can be about a comparison of ERP vs. ACT, how a cluster of neurons interact because of a specific chromosome, a summary of interviews with patients, or any other topic—but the structure of each paper is generally the same.

- The abstract

A summary of the entire paper in about 250-500 words that ideally points out the purpose of the study, what the study found, and what the results mean. 5-7 keywords are listed at the end that tell the reader the topic of the paper.

- The introduction

A text that explains the previous research that has been done on the topic of the paper, which finishes with a paragraph or two explaining the purpose of the present study. (Sometimes the “Purpose of the Study” will be its own section.)

Introductions are full of terminology and references, and are usually the most verbose parts. You’ll see a lot of parentheses with names and years (e.g. Smith & Jones, 2023). These are citations and tell the reader whose study is being referenced.

All research needs to stand on prior research, theories, and evidence, and is typically a new look into something or a reassessment of a prior study. The introduction is also called a “literature review” because it looks at what has been done before and gives credit to the authors. It’s super important—a scientist may think they’ve come up with a completely new idea, but may find that someone else already had that and wrote about it. Credit must be given where it’s due.

The “Purpose of the Study” at the end (or the last few paragraphs) will state what the current study is trying to achieve. It will present a hypothesis (an “educated guess” based on prior research), how it will test this hypothesis, and why this study is important.

- Participants

A description of the sample—people whose characteristics and responses were used to carry out the study. The participants section tells the reader who the “experimental group” is: the people chosen for the study, and how and why they were chosen (e.g. diagnoses, age). It will also usually describe a “control group” (a group of people who do not have a particular diagnosis or similar metric, whose responses will act as a comparison to the “experimental group”). This section will usually reference a table that describes demographic characteristics in terms of full numbers and/or percentages.

A description of the tools used to carry out the study with the participants. Here, tools can range from the complicated machinery used to carry out brain scans to the simple questionnaires that scientists use to ask participants about their symptoms, thoughts, and feelings and even to the location of where the study took place (a laboratory vs. somewhere else). The methods section will also describe the statistical tests used to analyze the data that is gathered using these tools.

This section is super important for scientists. It serves as an instruction manual of sorts for how to conduct the study, and would ideally allow other researchers who wish to copy the experiment in the future to do so. For the non-scientist, keep in mind that the methods section is very technical by design.

A description of results based on the analyses of data gathered from testing participants.

Although usually shorter than the others, this section is by far the most technical and complicated to understand for non-scientists. It’s common to see numbers, Greek letters, abbreviations, and other “lingo” here. Most tables and figures (charts and graphs) in an article are tied to the results section, and are also technical.

Although each paper has its own approaches, you will see a few common phrases throughout. Here are a few that are the “backbone” of each paper, without getting into too much “stats class” detail:

- (Statistically) Significant: The results of the analysis show that there is a connection to something that is not attributable to chance or randomness.

- (Statistically) Nonsignificant: The results of the analysis show that there is a higher likelihood of the results being attributed to chance or randomness, and not necessarily to the treatment, intervention, or interplay between the things studied.

- α : The Greek letter alpha ( α ) stands for significance level, a metric used as a threshold for whether the analysis is significant or not. α is usually set at .05, .01, or .001, depending on the needs of the study. These numbers are also percentages—0.05 here means that there is a 5% risk of the study showing that the results are correct when they’re actually not, 0.01 means a 1% risk, and so on.

- p : The letter p stands for probability, and the number that follows either an equals sign (=), a greater-than sign (>), or a less-than sign (<) is the probability number that is compared to the α value set by the researchers. If a p value is less than α set at 0.05, this means that the result is statistically significant and is not attributed to chance. If it is greater than the α value, the result is not statistically significant.

—Think of α as a threshold and p as the number you compare to the threshold.—

Let’s look at this with an example. “Treatment A is statistically significant at reducing symptom X, p =.03, α <.05.” In this study, with the group of participants who were tested at the location where this study took place, Treatment A reduced symptom X at a solid enough level where the results can be soundly not attributed to chance or randomness, because the p value was less than the α value.

The first part of that sentence is emphasized for a reason: this study can be done again by the same set of researchers or by a different group, and find that Treatment A actually doesn’t work so well (or works even better). As authoritative and confident a results section can look, all results should be read with the context of who the study participants were, where the study took place, and other important circumstances.

A less technical description of the results, usually written without many numbers and statistics. The discussion section shows in plain(er) language whether the results of the study supported the hypothesis outlined in the introduction, and why these results are important. A good discussion should also show what the researchers believed to be the strengths of their study (it’s good to do something innovative), as well as admit to limitations and weaknesses that could be addressed in future research (no study is perfect, and scientific humility goes a long way). The final paragraphs can suggest what future research on this topic can do, and neatly summarize the study (sometimes this can be a separate “Conclusion” section).

III. How to Read a Research Article and Get What You Need

With the descriptions of each section in mind, you’ll see that this is nothing like reading a novel, a magazine, or a web article. Texts and articles like that usually follow a pattern that requires reading from start to finish, or else there will be much confusion.

While a research article can certainly be read from start to finish (and it is encouraged to do so when trying to understand a topic at an expert level), it doesn’t have to be. In fact, most researchers don’t have time to read multiple studies word-for-word, and the structure of research articles allows them to jump around an article and get the information they need quickly and efficiently. Everyone has their own way of quickly tearing apart an article in 10 minutes, and I’d like to give you a technique which works for me if I want to casually understand a study. (For scientific purposes, I definitely read them in more detail.)

- Read the abstract first. It’s a short summary of the whole study, and you’ll go into it with a general idea of what’s happening.

- Read the “Purpose of the Study” or the last paragraphs of the introduction. With the abstract in mind, you’ll now understand in more depth what the study is about and trying to achieve here.

- Read the “Conclusion” or the last paragraphs of the discussion. Yes, skipping all the way to the end is allowed—now you’ll know the basics of what the study found and if more research is needed.

- Briefly read the “Discussion” in full. This will give more detail to what you just read, will explain why the study found what it found, and its strengths and limitations.

- Skim the “Participants”. Look for demographics, the location of the study, how long it took, and so on—now you’ll understand in what kind of experimental group these results were found.

- Skim the “Methods”. It’s technical; just pay attention to what kind of tests were run and whether they’re something standard in psychology or something new.

- Skim the “Results”. If you can understand the statistics and read the charts, great! If not, follow the “common phrases” I outlined above and skim.

- Skim the “Introduction”. By this point, you’ll already have a general idea of what the study’s purpose was, what the results found, and whether this topic needs further research. But if you’re interested in seeing how the study came to be based on prior research articles, then skim the “Introduction”. You’ll also find some definitions for what certain terms mean (and if not, you can look them up at a reputable source).

This should take about 10 minutes and give you a casual but solid understanding of what, when, where, why, and how a group of scientists did what they did.

IV. Some Final Words of Advice

I hope that the last sections made it easier to read a research article and know how to understand it. Keep practicing these skills by reading more articles, especially challenging ones. Over time, you’ll see that you will follow along with greater ease and (dare I say it?) enjoy reading them.

Before this ends, here are a few final words of advice.

1. You may realize it’s hard to fully trust statistics, especially when they are difficult to understand. First, a good research article is published in a peer-reviewed academic journal, meaning that groups of other scientists rigorously review an article before it is published. These reviewers pay special attention to the statistics and results, as publishing correct data is essential for good and flourishing science. If an article made it to the point of being published, there is a high chance that you can trust the statistics.

Also, being healthily skeptical and asking questions about statistics—or anything else—is the mark of a scientist. No scientist knows absolutely everything, and always asks questions, reaches out to fellow scientists, and reads and watches relevant content. Ask questions and be curious!

2. Don’t worry if you don’t understand everything (something that I recognize is a struggle for some folks with OCD). No one understands everything—not even top scientists. They ask questions all the time, and know that having a definitive answer is usually impossible when it comes to psychology.

3. Most things in psychological research are approximations, based on the sample that was chosen, where the study was conducted, and the strengths and limitations of a particular approach. The same framework can lead to different results with different samples and locations—and all of those results are approximations. By their nature, social sciences—those that deal with people—are more dynamic and have more nuance than the hard sciences (physics, chemistry, and biology). Nothing is perfect here and there is always more work to be done in OCD and related disorders research; it’s perfectly fine to take things with a grain of salt.

4. Google and YouTube are your friends—if you know how to use them properly. If you have questions, you can definitely search things up, as long as you know what you’re searching for and where to look. If you want to understand statistics in more depth, you can check out channels like CrashCourse for easy-to-follow explanations and Khan Academy for detailed lessons.

5. You can reach out to researchers directly if you have questions. Though busy, they’re usually quite happy to talk about their studies and point you in the right direction! And you can always email us at [email protected] or [email protected] as well!

Thank you for reading this! I’ll follow up with a second part that will get more into the technical aspects of research articles, but hope that this will be enough for a start. In the meantime, please visit https://iocdf.org/research/ to learn more about research at the IOCDF, the studies we have funded, and our 2023 Research Grant Program!

B oris Litvin is the IOCDF Research Communications Specialist.

This is SUCH a fantastic and necessary guide/post, for people in the community and beyond! Thank you so much for taking the time to create this, Boris & the IOCDF. Research is power, and should be accessible to not just those in the field – Can’t wait for the next post too!

Thank you so much for the kind words, Uma! Working on part II 🙂

Boris—this is brilliant. You explored such an important topic—relevant to academicians and laypeople alike—and wrote a piece helping to close the gap between what occurs in academia and what occurs “in the real world”. Congratulations!

Thank you very much, David!!!

Thank you for sharing this. I posted it in our OCD Research, Education and Support Group.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

borislitvin

Recent Posts

- Spectrum Designs: A Partner Empowering Through Employment

- Attending #OCDCon: Saving your ORLAN(DOUGH) $

- The Time OCD came to visit…and didn’t leave…

- Faith and OCD: Discussion and Enlightenment: Why you should attend the Faith and OCD Conference

- Self-Acceptance: A Repeated Practice

Your gift has the power to change the life of someone living with OCD!

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Writing the Introduction/Background of a Research Article

Writing the introduction and background of a research article can be daunting. Where do you start? What information should you include?

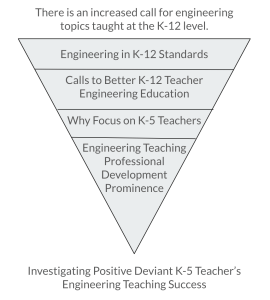

A great place to start is creating an argument structure for why your research topic is relevant and important. This structure should clearly walk the reader through current, relevant literature and lead them to the gap in the literature that your topic fills. To do this I use the following 4-step argument creation structure.

- Create argument funnel questions/statements

- Harvest article quotes that explain/backup each of the argument funnel questions/statements

- Organize article quotes to best support each section of the argument funnel

- Write prose that utilizes the article quotes to progress your argument from most well known to your specific topic

1. Argument Funnel Creation

Create an argument funnel with statements that take the reader form the most well known and widely accepted knowledge connected to my topic down to your specific research topic.

Completed Argument Funnel Example

When creating your funnel statements think about what research exists related to your topic. Where are the gaps in the existing literature? How do you know those are the gaps? If you get stuck, think about the 50,000 ft view of your topic and how you would explain the necessity of your research to people not in your field.

2. Harvesting Article Quotes

Find research articles that pertain to each of your funnel statements to back them up with evidence. As you find the articles put them into a citation manager (e.g., Zotero) now to save yourself time later. While reading the articles, pull (copy and paste) article quotes/excerpts that MAY be relevant. Pull more than you think you need, especially duplicates of the same idea by different authors to strengthen your argument. Store your quotes/excerpts in a document organized by your funnel statements with in-text citations with the page number you pulled it from. The National Academy of Engineering reports can be valuable top of funnel resources.

3. Organizing Article Quotes

Once you have harvested many article quotes for each of your funnel statements, organized them in an order that walks your reader through the literature landscape in a logical way. As you do this assume the reader doesn’t know anything about your topic so start at the beginning. Chronological order is a good place to start but may not always fit your argument. Think about your quotes/excerpts as puzzle pieces, where do they logically fit together?

4. Writing Prose

Now that your article quotes are organized, summarize the quotes in your own voice with appropriate citations. This is the time to begin including transition/connecting words and phrases between summarized quotes to bring your reader through your argument. Don’t forget to include “so what?” sentences and phrases after summarized quotes. In other words don’t only report what other authors said or found, tell the reader why that is important to your argument.

Library Research at Cornell: Find Articles

- The Research Steps

- Which Topic?

- Find the Context

- Find Articles

- Evaluate Sources

- Cite Sources

- Review the Steps

- Find Primary Sources

- Find Images

- Library Jargon

Tips for Finding Articles

- Use online databases to find articles in journals, newspapers, and magazines (periodicals). You can search for periodical articles by the article author, title, or keyword by using databases in your subject area in Databases .

- Choose the database best suited to your particular topic--see details in the box below.

- Use our Ask a Librarian service for help for figuring out which databases are best for your topic.

- If the article full text is not linked from the citation in the database you are using, search for the title of the periodical in our Catalog . This catalog lists the print, microform, and electronic versions of journals, magazines, and newspapers available in the library.

Finding Periodicals and Periodical Articles

Topic outline for this page:

- What Are Periodicals?

Finding the Periodical When You Do Have the Article Citation

- Locating Periodicals in Olin and Uris Libraries

Distinguishing Scholarly Journals from Other Periodicals

- Evaluating Individual Periodical Titles

What are Periodicals?

Periodicals are continuing publications such as journals, newspapers, or magazines. They are issued regularly (daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly).

The Cornell Library Catalog includes records for all the periodicals which are received by all the individual units of the Cornell University Library (Music Library, Mann Library, Law Library, Uris Library, etc.).

The Cornell Library Catalog does not include information on individual articles in periodicals. To find individual periodical articles by subject, article author, or article title, use periodical databases .

When you know the periodical title ( Scientific American, The New York Times, Newsweek ) search the Cornell Library Catalog by journal title .

Finding Articles When You Don't Have the Citation

To find an article, use databases.

When you don't have the citation to a specific article, but you do want to find articles on a subject, by a specific author or authors, or with a known article title, you need to use one or more periodical databases . But how do you know which periodical index to use?

What kind of periodicals are you looking for?

- scholarly journals?

- newspapers and substantive news sources?

- popular magazines?

- all three kinds?

[ Learn how to identify scholarly journals, news sources, and popular magazines. ]

If you want articles from scholarly, research, peer-reviewed journals , ask a reference librarian to recommend an index/database for your topic. Some databases index journals exclusively, like America: History and Life , EconLit , Engineering Village , MLA Bibliography , PsycINFO , PubMed , and Web of Science . Google Scholar searches across all scholarly disciplines and subjects. You can also use the subject menu in Databases linked from the library home page to locate databases that index scholarly publications.

If you want newspaper articles , see this guide to newspaper indexes and full-text newspaper databases . Online databases for finding newspaper articles are listed here: News Collections Online: News Databases .

If you want popular magazines , use Academic Search Premier or ProQuest Research Library . A printed index, Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature covering popular magazines from 1890 to 2011 is found in the Olin reference collection (Olin Reference AI 3 .R28).

The online index Reader's Guide Retrospective indexes popular magazines from 1890 to 1982 online. Periodical Contents Index covers some popular magazines for an even broader time period: 1770 to 1993.

If you want an index to all three kinds of articles, use Academic Search Premier or ProQuest Research Library . To find older articles, try Periodical Contents Index ; it indexes periodicals from 1770 to 1993.

If you want to search many databases simultaneously , use Articles & Full Text , also linked from the Library home page .

- If you're not sure which kind of periodical you want or you're not sure which periodical index to use, or if you want help searching, ask a reference librarian .

Remember you can always browse the titles of online periodical databases available online by clicking on this link to the subject categories in the Databases or on the Databases link in the search box on the Library home page .

When You Have a Citation to a Specific Article, Use the Cornell Library Catalog

When you do have the citation or reference to a periodical article--if you know at least the title of the periodical and the issue date of the article you want--you can find its location at Cornell by using the Cornell Library Catalog . Choose "Journal Title" in the drop-down menu to the right of the search box, click in the search box, type in the title of the periodical in the search box, and press <enter> . Don't use the abbreviated titles that are often used in periodical indexes; remember to omit "a," "an" or "the" when you type in the periodical title.

Search examples in the Cornell Library Catalog:

* When searching for the title, Journal of Modern History

Type the following in the search box: journal of modern history

* When searching for the title, Annales Musicologiques: Moyen-Age et Renaissance

You may type the following: annales musicologiques moyen age (Omit punctuation) (searching is not case sensitive)

Depending on the number of records your search retrieves, you will see either a list of entries or a single record for an individual periodical title. If there is a list of titles, scroll through it and click on the line that lists the journal title you want to see for the call number and location information or the online link(s).

If the journal is available in electronic form , there will be a link or links int the box labelled "Availability" in the catalog record. Click on this link. In most cases, this will take you to the opening screen for the journal, and you can choose the issue you want from there.

If the journal is available in print form , record the call number and any additional location information in the catalog record. Now you're ready to find it on the shelf. Consult the local stack directory for the call number locations in individual libraries.

Locating Print Periodicals in Olin and Uris Libraries

Current periodicals:.

Periodicals noted as "Current issues in Periodicals Room" in the Cornell Library Catalog are print journals shelved by title in the Current Periodicals Room on the main level in Olin Library. This room is immediately to the right and down the hall as you enter Olin Library. Only a small selection of current print periodicals is in this room : all other current periodical issues go directly to the Olin stacks where they are shelved by call number.

Back Issues of Periodicals

Back issues of periodicals are shelved by call number in the Olin and Uris Library stacks. Some back periodicals are shelved in specific subject rooms; watch for location notes in the Cornell Library Catalog record for the title you want.

Pay attention to the + and ++ indicators by the call number. Titles with the + and ++ (Oversize) designations and titles with no plus marks are each shelved in separate sections on each floor in Olin Library and separate floors in Uris Library.

Back issues on microfilm, microfiche, and microprint are housed on the lower or B Level in Olin Library.

Journals, news publications, and magazines are important sources for up-to-date information across a wide variety of topics. With a collection as large and diverse as Cornell's it is often difficult to distinguish between the various levels of scholarship found in the collection. In this guide we have divided the criteria for evaluating periodical literature into four categories:

- Scholarly / VIDEO: How to Identify Scholarly Journal Articles

- Substantive News and General Interest / VIDEO: How to Identify Substantive News Articles

- Sensational and Tabloid

Definitions:

Webster's Third International Dictionary defines scholarly as:

- concerned with academic study, especially research,

- exhibiting the methods and attitudes of a scholar, and

- having the manner and appearance of a scholar.

Substantive is defined as having a solid base, being substantial.

Popular means fit for, or reflecting the taste and intelligence of, the people at large.

Sensational is defined as arousing or intending to arouse strong curiosity, interest or reaction.

Keeping these definitions in mind, and realizing that none of the lines drawn between types of journals can ever be totally clear cut, the general criteria are as follows.

Scholarly journals are also called academic, peer-reviewed, or refereed journals . Strictly speaking, peer-reviewed (also called refereed) journals refer only to those scholarly journals that submit articles to several other scholars, experts, or academics (peers) in the field for review and comment. These reviewers must agree that the article represents properly conducted original research or writing before it can be published.

To check if a journal is peer-reviewed/refereed, search the journal by title in Ulrich's Periodical Directory --look for the referee jersey icon.

What to look for:

- Scholarly journal articles often have an abstract, a descriptive summary of the article contents, before the main text of the article.

- Scholarly journals generally have a sober, serious look. They often contain many graphs and charts but few glossy pages or exciting pictures.

- Scholarly journals always cite their sources in the form of footnotes or bibliographies. These bibliographies are generally lengthy and cite other scholarly writings.

- Articles are written by a scholar in the field or by someone who has done research in the field. The affiliations of the authors are listed, usually at the bottom of the first page or at the end of the article--universities, research institutions, think tanks, and the like.

- The language of scholarly journals is that of the discipline covered. It assumes some technical background on the part of the reader.

- The main purpose of a scholarly journal is to report on original research or experimentation in order to make such information available to the rest of the scholarly world.

- Many scholarly journals, though by no means all, are published by a specific professional organization.

Examples of Scholarly Journals:

- American Economic Review

- Applied Geography

- Archives of Sexual Behavior

- JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association

- Journal of Marriage and the Family (published by the National Council on Family Relations)

- Journal of Theoretical Biology

- Modern Fiction Studies

Substantive News or General Interest

These periodicals may be quite attractive in appearance, although some are in newspaper format. Articles are often heavily illustrated, generally with photographs.

News and general interest periodicals sometimes cite sources, though more often do not.

Articles may be written by a member of the editorial staff, a scholar or a free lance writer.

The language of these publications is geared to any educated audience. There is no specialty assumed, only interest and a certain level of intelligence.

They are generally published by commercial enterprises or individuals, although some emanate from specific professional organizations.

The main purpose of periodicals in this category is to provide information, in a general manner, to a broad audience of concerned citizens.

Examples of Substantive News and General Interest Periodicals:

- The Economist

- National Geographic

- The New York Times

- Scientific American

- Vital Speeches of the Day

Popular periodicals come in many formats, although often slick and attractive in appearance with lots of color graphics (photographs, drawings, etc.).

These publications do not cite sources in a bibliography. Information published in popular periodicals is often second or third hand and the original source is rarely mentioned.

Articles are usually very short and written in simple language.

The main purpose of popular periodicals is to entertain the reader, to sell products (their own or their advertisers), or to promote a viewpoint.

Examples of Popular Periodicals:

- People Weekly

- Readers Digest

- Sports Illustrated

Sensational or Tabloid

Sensational periodicals come in a variety of styles, but often use a newspaper format.

Their language is elementary and occasionally inflammatory. They assume a certain gullibility in their audience.

The main purpose of sensational magazines seems to be to arouse curiosity and to cater to popular superstitions. They often do so with flashy headlines designed to astonish (e.g., Half-man Half-woman Makes Self Pregnant).

Examples of Sensational Periodicals:

- National Examiner

- Weekly World News

Evaluating Periodicals: Magazines for Libraries

Magazines for Libraries describes and evaluates journals, magazines, and newspapers:

Or ask for assistance at the reference desk .

Reference Help

- << Previous: Find Books

- Next: Evaluate Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 11:29 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/sevensteps

Magnum Proofreading Services

- Jake Magnum

- Feb 19, 2021

How to Write an Abstract Before You Have Obtained Your Results

Updated: Jul 5, 2021

When you need to produce an abstract for research that has not yet been carried out, you should write what is known as a descriptive abstract . In this type of abstract, you explain the background, purpose, and focus of your paper but not the results or conclusion.

Obviously, it is preferable to write the abstract for your research after you have obtained your results. While you might be under pressure to submit an abstract months before your research has been completed, it is still best to postpone writing your abstract until you have your results if this is at all possible. The advice given in this article is intended for authors who have no choice but to submit an abstract before they have their results.

Guidelines and Tips for Writing an Abstract without Results

When you need to write an abstract but haven’t yet gathered your results, you can write a descriptive abstract . While these are typically used for papers written in the humanities and social sciences, you may adapt them to a scientific work if you have no other option — for example, if you need to submit an abstract eight months before your research is scheduled to be completed.

A typical descriptive abstract accomplishes three things — namely, it (1) provides background information about your study topic, (2) expresses the purpose of your study, and (3) explains what you will do to accomplish your study’s purpose. Descriptive abstracts do not usually make any mention of a study’s results. However, if a description of the results is a general requirement for your abstract, you can briefly state that you intend to express your results at a later time (after you have gathered your data).

This article will guide you through writing all three parts of a descriptive abstract for a scientific paper. Afterward, examples of full abstracts written in this style are provided.

1. Background: Give general information about your topic.

The background section of a descriptive abstract is longer than that of an informative abstract (which is the abstract style used in most scientific works). The background information provided in an informative abstract is often restricted to two sentences, one mentioning the study topic and the other introducing the general problem to be addressed. A further discussion of these kinds of abstracts can be found here . In a descriptive abstract, you can use two sentences for each of these purposes, which allows you to give more detailed background information.

The background section of an informative abstract might read as follows:

Body dissatisfaction has adverse effects on women of all ages. However, research suggests that women can apply self-compassion to reduce body dissatisfaction and create a positive body image instead. This paper aims to…

In this example, the author very quickly lets the reader know the overall topic of their paper (body dissatisfaction among women) and what avenue of this topic they will explore. They then immediately transition into discussing the purpose of their paper.

If the author had written a descriptive abstract instead, the background section might look like this:

Body dissatisfaction has adverse effects on women of all ages. It has been linked to low self-esteem, depression, social anxiety, and eating disorders. These problems can be made worse when a woman criticizes herself because of her body. Conversely, practicing self-compassion, which entails being warm towards oneself when recognizing one’s failures or inadequacies, can reduce body dissatisfaction and help to create a positive body image. This paper aims to…

In this second example, the author uses an extra sentence to list some of the specific adverse effects of body dissatisfaction. The author also defines the key term of “self-compassion” to give non-experts of the subject a better understanding of the topic.

2. Purpose: Describe the general problem that your research aims to explore.

This part of a descriptive abstract is typically made up of a single sentence. Here, you should describe your purpose for conducting your research work. This sentence should be more specific than the preceding sentences, as it should describe the specific constructs that the study will investigate. Unlike the other parts of a descriptive abstract, the sentence describing the study’s purpose should be the same as it would appear if you were writing an informative abstract.

This paper aims to explore sources of positive and negative body image by investigating whether the association between self-esteem and body image avoidance behaviors is mediated by self-compassion and appearance contingent self-worth.

This example was taken from an informative abstract but could just as well be included in a descriptive abstract.

3. Focus: Explain what you intend to do to solve the problem.

Normally, you would now describe what you did to accomplish your research goal. However, if you have not yet carried out your research, you have nothing to report. As such, you should instead explain what you intend to do to accomplish your goal. It is best to be specific regarding what tools you will use and what parameters you will measure.

In an informative abstract, the author could express the focus of their research as follows:

Using a multiple mediation model, we assessed the responses of 222 female participants who completed the Body Image Avoidance Questionnaire.

Here, the author quickly explains who the participants were, what the researchers measured, and what tool they used.

If you are writing a descriptive abstract because you do not yet have your results, then this part of your abstract will be different in two ways. First, you will have to leave out information that you do not have (e.g., the number of participants). Second, you cannot write this sentence in the past tense since you haven’t done anything yet. If the example sentence above were part of a descriptive abstract, it might read as follows:

We will employ a multiple mediation model to assess the responses given by a group of females to the Body Image Avoidance Questionnaire.

Here, the author has not included the number of participants, and they have stated what they will do rather than what they have done.

Do not in any way express what you expect or hope to find.

If you were writing an informative abstract, the next step would be to describe your results. If you are writing a descriptive abstract instead, you might be tempted to describe what you expect or hope to find. However, this should be avoided, as it reflects a lack of scientific integrity and will be perceived as misleading if you do not obtain the expected results.

On this note, you must be very careful about how you express the purpose of your study. To clarify this, I will revisit a previous example.

The use of the word “whether” is crucial in this sentence, as it expresses doubt. That is, it indicates that you don’t know what you will find. Therefore, no matter what results you obtain, this sentence cannot be considered misleading.

The following example includes a subtle change in wording, but it changes the implied meaning of the sentence:

This paper aims to explore sources of positive and negative body image by showing that the association between self-esteem and body image avoidance behaviors is mediated by self-compassion and appearance contingent self-worth.

“Investigating whether” has been changed to “showing that.” Because of this change, the author is now claiming that they will obtain a certain result (i.e., that self-compassion and appearance contingent self-worth mediate the relationship in question). This statement will be considered misleading if either variable does not turn out to be a mediating factor.

Examples of Abstracts without Results

I will begin with an abstract from the field of English literature, where descriptive abstracts are common. Afterward, I will provide a second example that shows how you can adapt this style to an abstract written in a scientific field.

(1) Revolutions are considered as a way to replace a situation or system of government with a better one. (2) However, many writers have addressed the question of whether revolution really is the right way to improve people’s lives or if it merely changes the faces of rulers or the names of governments. (3) George Orwell, who was considered an apolitical writer, is one of the writers who tackled this issue. (4) His novella Animal Farm is an allegorical story of some animals living on a farm who successfully revolt against their owner, only to create a dystopia in the end. (5) This paper aims to explore the nature of revolution throughout human history in general and how this phenomenon is treated by Orwell in his novella. (6) Specifically, we intend to use examples from Animal Farm to investigate whether we should consider revolution as an appropriate way to generate a true change in a political system and in the way people think.

The above abstract is a modified version of the abstract from “The Nature of Revolution on Animal Farm.” It contains the three main parts that have been described in this article:

First, Sentences (1)-(4) provide background information for the present study. In sentence (1), the author makes a very broad statement about a widespread topic (i.e., revolutions). Sentence (2) describes the general problem that the paper addresses. The author then gets more specific in Sentences (3) and (4), mentioning a specific writer and a specific novella.

Second, the author states their purpose for writing the paper in Sentence (5), indicated by the introductory phrase “this paper aims to.” Notice that the purpose stated in this sentence is quite general, though it is more specific than the problem described in Sentence (2).

Third, in Sentence (6), the author explains what particular question they intend to answer (i.e., “Should we consider revolution as an appropriate way to generate a true change in a political system?”), and they mention what tools they will use to do this (i.e., examples from Animal Farm ).

(1) The physical self has been considered one of the most important factors impacting global self-esteem. (2) Moreover, the physical self has recently become widely accepted as a multidimensional construct that contains several specific perceptions across various domains. (3) However, limited research has examined the physical self of athletes with physical disabilities, especially in Middle-Eastern countries. (4) Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the physical self-esteem and global self-esteem of wheelchair basketball players from Middle-Eastern countries. (5) Using the Physical Self-Description Questionnaire (PSDQ) as a measurement tool, this study aims to determine (i) whether there is a correlation between physical self-esteem and global self-esteem and (ii) which of the nine domains of the PSDQ (Health, Coordination, Activity, Body Fat, Sport Competence, Appearance, Strength, Flexibility, and Endurance) are correlated with physical self-esteem.

The above abstract is a modified version of the abstract of the article entitled “Physical self-esteem of wheelchair basketball players.” It has the same three main parts as the first example:

First, Sentences (1)-(3) are devoted to providing the background of the study. Specifically, Sentences (1) and (2) describe the general topic that will be investigated, while Sentence (3) states the general problem that the author intends to explore.

Second, in Sentence (4), the author states the overall purpose of their study by explaining what aspect of the issue mentioned in Sentence (3) they will be tackling.

Third, Sentence (5) describes the specific questions that the study will address (i.e., “Is there a correlation between physical self-esteem and global self-esteem, and which of the nine domains of the PSDQ are correlated with physical self-esteem?”). It also lets the reader know what kind of data will be used to answer these questions (i.e., PDSQ scores). Notice that the authors do not state that they expect to find any correlations.

- How to Write an Abstract

Related Posts

How to Write a Research Paper in English: A Guide for Non-native Speakers

How to Write an Abstract Quickly

Using the Present Tense and Past Tense When Writing an Abstract

This was very helpful. Thank you very much!

Thank you very much! very nice explanations for researchers in any level.

Thank you for the elaborate and clear explanations. It's been of great help. Be blessed!

Before-and-After Study

In the field of mental health, interventions (e.g., support groups) and products (e.g., digital apps) aim to improve people’s mental health, well-being or quality of life. But, how do you know if they actually have a positive impact?

To investigate whether an intervention or product has led to change, you can conduct a before-and-after study (also called pre-post study). The UK Health Security Agency describes a before-and-after study as measuring an outcome variable in a group of participants before introducing an intervention or product, and then again afterwards. Examples of outcome variables are mental health, well-being or quality of life measurements. If you observe a change in your outcome variable, you may conclude it was due to the product or intervention. However, it cannot be ruled out that something else might have caused the change, such as unexpected life events or improved access to treatment or social support.

[Image source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297715736_Embedding_Analogical_Reasoning_into_5E_Learning_Model_A_Study_of_the_Solar_System/figures?lo=1 ]

To conduct a before-and-after study, you should use the following steps as a guide:

- decide on the outcome variable you want to improve through your intervention

- recruit your sample

- get informed consent

- assess your outcome variable before starting the intervention

- deliver the intervention

- assess your outcome variable when the intervention is complete

- run your data analysis and compare your findings from before and after the intervention

For example, McKechnie and colleagues conducted a before-and-after study to investigate the effectiveness of an internet support forum for carers of people with dementia. They expected that using this forum for twelve weeks would decrease anxiety and depression in carers and change the quality of the relationship between the carer and the person with dementia. The researchers recruited a sample of 61 new forum users who gave informed consent to participate in the study. The forum users first completed questionnaires on the outcome variables of anxiety, depression and quality of relationship before starting the intervention. Then, they used the forum for twelve weeks. After using the forum, they completed the same questionnaires on anxiety, depression and quality of relationship again. The researchers ran their analysis and found that using the forum improved the quality of the relationship with the person with dementia. But they did not find change in users’ depression or anxiety over the 12-week study period.

(Author: Leonie Ader)

What is it?

“ What is a One-group pretest/posttest research design (pre-experimental research)?? ” by Search Research (2021)

This video briefly describes the pretest/posttest research design (equivalent to before-and-after study) using two specific examples.

(Academic reference: Search Research (2021, May 17). What is a One-group pretest/posttest research design (pre-experimental research)?? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JkOj6hA-Gq8&ab_channel=SearchResearch)

“ Before-and-after study: comparative studies ” by UK Health Security Agency (2020)

This article includes a comprehensive definition of the before-and-after-study design, what to use it for, Pros and Cons of the study design, how to carry out a before-and-after study as well as a real-world example.

(Academic reference: UK Health Security Agency (2020, January 30). Before-and-after study: comparative studies. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/before-and-after-study-comparative-studies#:~:text=A%20before%2Dand%2Dafter%20study%20(also%20called%20pre%2D,to%20the%20product%20or%20intervention)

How is it done?

Presentation:

“ Pre-post outcome analyses ” by Russell Cole (2020)

This high-level presentation describes how results from before-and-after studies can be analysed.

(Academic reference: Cole, R. (2020). Pre-post outcome analyses [PowerPoint slides]. https://opa.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/tpp18-pre-post-webinar-slides.pdf )

Method in action

“ Pre-Post Test Graphs ” by Greg Marchant (2013)

This video shows how to calculate graphs for a before-and-after study (pre-post test) using Excel.

(Academic reference: Marchang, G. (2013, March 20). Pre-Post Test Graphs [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4yZv6rx-vaw&ab_channel=GregMarchant)

“ The Effectiveness of an Internet Support Forum for Carers of People With Dementia: A Pre-Post Cohort Study ” by McKechnie and colleagues (2014)

This academic journal article is the full description of the before-and-after study described in the text.

(Academic reference: McKechnie, V., Barker, C., & Stott, J. (2014). The effectiveness of an Internet support forum for carers of people with dementia: a pre-post cohort study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(2), e3166.)

Share This Post:

Related posts.

Quantitative Sampling

Records and Record Keeping

Cross-Sectional Studies

Realist Evaluation

We’d love to hear from you.

Collaboration is at the heart of our Research Methods Toolkit which means we value your voice, and want to hear what you have to say. Questions, suggestions and comments help us understand what works and what needs improvement. Feel free to suggest new content and resources that we might be able to develop for the Toolkit.

Research Methods for Society and Mental Health

Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2024 | Website by Backhouse Creative

- [email protected]

- Shapiro Library

- SNHU Library Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: How old should or can a source be for my research?

- 7 Academic Integrity & Plagiarism

- 64 Academic Support, Writing Help, & Presentation Help

- 27 Access/Remote Access

- 7 Accessibility

- 9 Building/Facilities

- 7 Career/Job Information

- 26 Catalog/Print Books

- 26 Circulation

- 129 Citing Sources

- 14 Copyright

- 311 Databases

- 24 Directions/Location

- 18 Faculty Resources/Needs

- 7 Hours/Contacts

- 2 Innovation Lab & Makerspace/3D Printing

- 25 Interlibrary Loan

- 43 IT/Computer/Printing Support

- 3 Library Instruction

- 37 Library Technology Help

- 6 Multimedia

- 17 Online Programs

- 19 Periodicals

- 25 Policies

- 8 RefWorks/Citation Managers

- 4 Research Guides (LibGuides)

- 216 Research Help

- 23 University Services

Last Updated: Jun 22, 2023 Views: 125610