- Get Involved

- Issue Brief pdf (2.3 MB)

Issue Brief: Advancing Gender Equality in Malaysia

Issue Brief

March 8, 2021

Gender equality is not only a basic human right, but is also critical in accelerating progress on sustainable development. The empowerment of women and girls is closely linked to several of the Sustainable Development Goals, including education, poverty, and climate change). One of the significant structural barriers to women’s economic empowerment is the disproportionate burden of domestic unpaid work that restricts women from undertaking paid jobs, advanced education and skills training, and—most importantly—participation in public life. While household work has economic value, it is not counted in traditional measures of GDP. It is estimated that unpaid work undertaken by women today “amounts to as much as $10 trillion of output per year, roughly equivalent to 13 percent of global GDP.” Social and cultural norms often limit the capacity of women to engage in the formal economy due to restricted mobility and lack of access to quality education, training, and finance, among other factors.

This Issue Brief provides a short overview of different aspects of gender equality in the Malaysian economy and how gender-responsive approaches in economic planning, budgeting and evaluation will contribute towards the shaping Malaysia into an inclusive society that it aspires to be.

Document Type

Regions and countries, sustainable development goals, related publications.

Publications

Issue brief: investing in the care economy: opportunities....

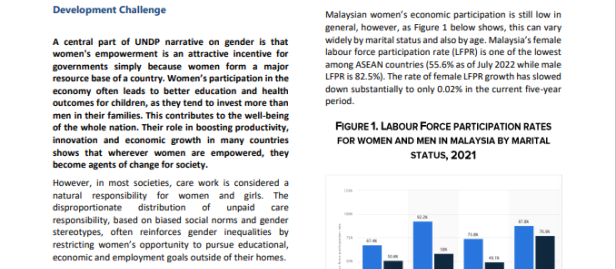

A central part of UNDP narrative on gender is that women's empowerment is an attractive incentive for governments simply because women form a major resource bas...

Inequality in Access to Essential Health and Medicine: CO...

Before the pandemic, the Asia Pacific region enjoyed the steepest human development growth globally. However, the progress is uneven within the region especiall...

The Onset of a Pandemic: Impact Assessments and Policy Re...

This report is a call to action, to prepare for future crises, and the ones that we are experiencing today to tackle the multi-faceted social and economic dimen...

Issue Brief: Projected impact of COVID-19 on Malaysian Hu...

The resulting simulation of COVID-adjusted HDI in 2020 shows a decline of the Malaysia HDI score from 0.810 in 2019 to 0.797, a contraction of 1.6 per cent. Non...

Cari Makan: General Observations on Building Forward Bett...

The COVID-19 pandemic has set back progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Globally, between 119 to 124 million people dropped back into extr...

Trends in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst indigenous p...

The uptake rate of COVID-19 vaccine among Orang Asli communities in Peninsular Malaysia is currently suboptimal if the intention is to achieve herd immunity. Fi...

It might sound awkward that a man is talking about gender equality but just to clear this, in Emma Watson’s words, “Men, gender equality is your issue, too”. I will take that invitation and begin to talk about gender inequality and women in Malaysia.

Let’s look at the Gender Gap Report which first started in 2006 and look at how we fared in 2014.

I am not sure how to explain the rankings nor do I have the time to go through the complex methodologies used but in relative terms against other countries, perhaps what I can conclude is

- We are progressing but at a slow pace;

- Male domination and chauvinism still exists.

In our workforce, Malaysia has come a long way since 1982. There were less than 1.8 million women employed in 1982 with a labour force participation rate of 44.5 percent and unemployment rate of 4.6 percent.

But in the most recent 2013 statistics, we saw the number of women employed almost tripled to about 5 million with a labour force participation rate of 52.4 percent and unemployment rate of 3.4 percent.

This means that more than half of women of working age are employed and this is a first in the Najib Abdul Razak administration and the only time we have breached 50 percent since 1982.

I believe it will most likely remain at this band of 50-60 percent.

Another recent encouraging news we read was from Hays Asia Salary Guide 2015. The employment of women in senior management roles in Malaysia has actually increased from 29 percent in 2014 to 34 percent in 2015.

But if anyone wants to be negative about this, we can. Put this in another way, after so long, we still see men dominating the senior management roles.

In political leadership, the numbers are disappointing. I realized that there are only two women ministers in our cabinet - Nancy Shukri (Minister in PM's Department) and Rohani Abd Karim (Women, Family and Community Development Minister). In Penang's state exco, there's only Chong Eng. In Selangor's state exco, they have two - Daroyah Alwi and Elizabeth Wong. In Kelantan's state exco, they have one women exco member - Mumtaz Md Nawi.

We can perhaps understand why if we look at the pattern in the GE 13 election results. In the recent 13th general election, we saw a total of 168 female candidates named out of the 727 Parliament and state seats. Seventy-one women candidates were from Barisan Nasional, 77 from Pakatan Rakyat while the rest were independents or non-BN and non-Pakatan. That is just 23 percent.

The results? Eighty female elected representatives only. That’s a winning rate of 48 percent and participation rate of 11 percent in our houses of representatives. That’s not good. How did this happen?

Here’s my message to the voters. If gender was a key criterion when you voted in the 13th GE, perhaps you should do us a favour and stay at home in the next election.

Marked improvement in key posts

In the federal government, we have seen a marked improvement where women today hold almost all of the key posts - from international trade and economic planning to welfare, education and healthcare. We have a total of 11 top ranked women in government today. Perhaps, I should name them here:

I have personally worked with a few of them in the list above plus a few other directors-general of other federal government agencies. They are more than capable to lead!

But the government can’t do this alone. It is as good as banking on only one sports legend - Nicol David - to carry the Jalur Gemilang in the sports arena when there are dozens if not a hundred different types of sport.

Based on a 2013 survey by Talent Corp, only 8 percent of board members of all listed companies were women and this is a long way off the government's target of 30 percent by 2016. Why is it a government target, I’m not sure, but although we must not forego meritocracy for the sake of meeting the numbers, any form of gender inequality on equal merits must not be tolerated especially by the private sector.

Perhaps what is lacking in Malaysia is an inspirational icon who can lead, educate and champion the cause for equality.

The fight against gender inequality must go on, especially in Malaysia. We cannot afford to slide further in the Gender Gap Report or slack in other initiatives.

Not just because Kofi Annan said that, “Gender equality is a precondition for meeting the challenge of reducing poverty, promoting sustainable development and building good governance”.

To me, it is about respect.

Happy International Women’s Day. #makeithappen

GOH WEI LIANG is a senior analyst at a government agency. He blogs at http://manifestogwl.blogspot.com

- The Star ePaper

- Subscriptions

- Manage Profile

- Change Password

- Manage Logins

- Manage Subscription

- Transaction History

- Manage Billing Info

- Manage For You

- Manage Bookmarks

- Package & Pricing

Beyond International Women’s Day: A look at Malaysia’s legal milestones for gender equality

Thursday, 14 Mar 2024

Related News

Bukit Assek rep hands out gifts of cooking oil for International Women's Day

Appreciate, respect and treat women with respect, says queen on international women's day, international women’s day reflects progress and challenges of women’s rights in laos, says country's top beauty queen.

LAST week, I had the extraordinary privilege of speaking at the EmpowerHER Symposium on International Women’s Day.

The symposium offered a beautifully nuanced exploration of women’s empowerment. There was a diverse range of speakers, each bringing their unique expertise and perspective to the table.

This multifaceted approach to empowerment resonated deeply with me, and It highlighted the interconnectedness of various aspects of women’s lives.

While other speakers offered valuable insights on beauty and health, a crucial yet often diminished aspect of empowerment, I felt a deep responsibility to delve into the legal framework that shapes Malaysian women’s lives.

The conversation on women empowerment is an essential one, not just once a year on International Women’s Day, but every day.

Despite Malaysia’s impressive female literacy rate and a growing participation in the workforce, challenges remain. To understand the current landscape and future possibilities, it’s nonetheless important for us to examine Malaysia’s legal journey concerning women’s rights.

Malaysia’s accession to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1995 marked a significant turning point for women’s rights in the country.

This international commitment served as a catalyst that propelled Malaysia forward on the path towards gender equality. It ushered in a wave of legal reforms aimed at dismantling discriminatory laws and practices against women, both in public and private spheres.

Prior to this, legal protections for women were scarce, with limited recourse beyond the Penal Code, and Article 8(1) of the Federal Constitution which guarantees equality before the law.

However, the introduction of Article 8(2) in 2001, explicitly prohibiting gender discrimination, signalled a monumental shift in legislative attitudes.

Since then, Malaysia has moved from a landscape with limited legal protections for women to one that’s actively dismantling discriminatory practices. However, let’s not mistake progress for completion. While strides have been taken, achieving absolute protection for Malaysian women remains an ongoing endeavour.

What we have achieved so far

1. Anti-Sexual Harassment Act 2022 (Act 840)

This landmark legislation, nearly two decades in the making, finally became reality with the combined efforts of MPs from both sides of the aisle. Previously, women had to navigate a complex web of laws, including the Penal Code, Employment Act, and Communications & Multimedia Act, often yielding unsatisfactory results due to weak provisions and lengthy court proceedings.

Under the Act, “sexual harassment” is properly defined for the first time in Malaysia law.

It is defined as “any unwanted conduct of a sexual nature, in any form, whether verbal, non-verbal, visual, gestural or physical, directed at a person which is reasonably offensive or humiliating or is a threat to his well-being”.

It establishes a dedicated Tribunal to address complaints of sexual harassment, empowering women to seek compensation and redress within a two-month timeframe.

2. Amendment to Employment Act 1955 (Act 265)

The 2022 amendments introduced a new provision (Section 69F) specifically addressing employment discrimination. This gives power to the Labour Director-General to make direct inquiries into any employee-employer dispute concerning discrimination in employment, and to make decisions and orders thereof, with the aim to promote better protection for workers, particularly women, in line with international labour standards and CEDAW.

Prior to the amendment, Malaysian women facing discrimination in the workplace had limited legal recourse. Existing laws like the Employment Act offered some protection, but they often lacked specific provisions addressing gender discrimination. The burden of proof also often rested heavily on the employee experiencing discrimination.

3. Anti-Stalking Laws in the Penal Code (Act 574)

Stalking, a pervasive and often terrifying experience, lacked a clear definition in the Penal Code. This meant that seemingly innocuous actions, like repeated compliments or unwanted attention, couldn’t be addressed by law enforcement.

Existing sections of the Penal Code, such as those related to physical contact (Section 354 & 355) or lewd comments (Section 509), fell short of delivering women from prolonged fear and distress caused by stalking. The lack of a legal definition had left many women vulnerable to repeated harassment with few legal options available.

Thankfully, a crucial step forward was taken on March 29, 2023, with the amendment of the Penal Code.

The introduction of Section 507A now defines stalking as “the repeated act of harassment, which is intended or is likely to cause distress, fear, or alarm to any person for their safety.”

This broader definition encompasses a wider range of behaviours, both physical and online, that can cause significant emotional distress to the victim.

4. Abolition of Section 498 of the Penal Code

Not all laws are made by Parliament. Sometimes, we see caselaw establish new precedents and strike down unfair or unconstitutional laws. Under Yang Amat Arif Tun Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat, our very first woman Chief Justice, it is no coincidence that the current lineup of the Federal Court is said by some to be among the most progressive in Malaysia’s history.

This progressive stance was evident in a landmark ruling on Dec 15, 2023.

The Federal Court struck down Section 498 of the Penal Code as unconstitutional. This section previously penalised any man who entices away a woman that he knows is already married to another man.

However, Chief Justice Tun Tengku Maimun ruled that Section 498 violated the Federal Constitution’s Article 8(2) guaranteeing equality before the law. The critical flaw was that only husbands could utilise this provision, discriminating against women who couldn’t seek legal recourse if their husbands were enticed by another woman.

Celebrating progress is crucial, but the fight for women’s rights in Malaysia is far from over. Although Malaysia has made significant strides in recent years towards women’s rights, there are still critical gaps in the legal framework which leave many women vulnerable to abuse and limit the ability to live safe and fulfilling lives.

Our journey toward legal advancements for women’s rights hasn’t always been linear.

Progress isn’t always linear

A recent example highlights this challenge. Recently, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim announced plans to table legal amendments this month that would replace the term “whose father” with “parents or at least one of the parents” in Parts I and II of the Federal Constitution’s Second Schedule, slated for presentation in Parliament this month.

However, this optimism quickly turns to dismay when we consider the fact that the proposed amendment, while empowering women, was bundled with potentially regressive measures that could jeopardise citizenship rights of marginalised members of society, including foundlings, orphans, children born out of wedlock, and adopted children.

Among the proposed amendments are revision to the Second Schedule, Part II Section 1(e), which currently grants citizenship by operation of law to every stateless person born in Malaysia, and Second Schedule, Part III, Section 19(b), which would affect abandoned children.

Under the proposed changes, granting citizenship would become solely at the discretion of the Home Ministry, removing the current automatic pathway for those meeting the criteria outlined in the Second Schedule.

While I appreciate the positive strides made by this amendment package in advancing women’s rights, no woman could possibly endorse it in good conscience if it comes at the expense of further marginalising other vulnerable groups. We urge the government to consider decoupling the proposed amendments. Separating the women’s rights amendments would allow for their swift implementation while allowing for further discussion and refinement of any provisions that might negatively impact marginalised communities.

As we approach the 30th anniversary of CEDAW next year, it’s crucial to reflect on our achievements and identify the remaining legal gaps impacting women, both in their roles as mothers, and as professionals.

These vital reforms are deeply personal to me. As a woman in both politics and law, I’m fiercely committed to advocating and championing them. It’s about empowering not just women, but every Malaysian bar none to thrive and contribute equally in our society.

Let’s keep the conversation going and work together to build a future where equality for all is a reality.

CHAN QUIN ER

Lawyer and MCA central committee member

Tags / Keywords: International Women's Day

Found a mistake in this article?

Report it to us.

Thank you for your report!

Maybank myimpact SME leads the way in championing sustainability for SMEs

Next in letters.

Trending in Opinion

Air pollutant index, highest api readings, select state and location to view the latest api reading.

- Select Location

Source: Department of Environment, Malaysia

Others Also Read

Best viewed on Chrome browsers.

We would love to keep you posted on the latest promotion. Kindly fill the form below

Thank you for downloading.

We hope you enjoy this feature!

- Press Statements

- AGMs and EGMs

- In Memoriam

- Legal and General News

- Court Judgments

- Peer Support Network

- Sijil Annual and Payments

- Practice Management

- Professional Development

- Opportunities for Practice

- Mentor-Mentee Programmes

- Laws, BC Rulings and Practice Directions

- Become a Member

- Legal Directories

- BC Legal Aid Centres

- State Bar Committees

- Law Firms | Areas of Practice

- Useful Forms

- Malaysian Bar and Bar Council

- President's Corner

- Previous Committees

- Advertising

- Compensation Fund

New login method: If first-time login, the password is your NRIC No. Call 20502191 for help.

If you have lost your password, you must set a new password. To begin this process, please key in your 12-digit NRIC No. below.

Please enter name of firm or registered email address, indicate whether you want to retrieve your firm's username or password, and click "Submit".

Registration ( restricted to Members of the Malaysian Bar )

Fields marked with an asterisk ( * ) are required.

Please key in your membership number, and click "GO"

Please key in your pupil code, and click "Submit"

Change Password

- Legal Directory

- Online Shop

- BC Online Facilities

- Login Type 2

- Login Type 3

- Login Type 4

- Resolutions

- General News

- Members' Opinions

- Go back to list

GENDER EQUALITY UNDER ARTICLE 8: HUMAN RIGHTS,

ISLAM AND “FEMINISMS”

By © Salbiah Ahmad *

* LL.B (Hons.) University of Singapore, Masters in Comparative Law (International Islamic University, Malaysia), Dip. Shariah and Administration (IIUM), Recipient of fellowship from the Islam and Human Rights Fellowship, Religion and Law Program, University of Emory Law School, Atlanta, GA, USA (2003–2004) and the Southeast Asian Scholars and Public Intellectuals Fellowship (SEAF) of the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), National University Malaysia, 2000.

This paper explores the term gender under Article 8 (2) of the Federal Constitution. Art. 8 (2) inter alia provides that there shall be no discrimination on the basis of gender “except as expressly authorized by the Constitution”. The principle of gender non–discrimination is premised on the fundamental principle of equality, a principle enshrined in Art. 8 (1). Gender equality has a global jurisprudence to mean both “sameness” and “difference”, notions included in a substantive equality standard which prioritizes equality of opportunity and outcomes. These issues remain unexplored in local jurisprudence. The paper also looks at equality in human rights and in Islam, as the latter factor continues to inform politics, policy and law in Malaysia. An understanding of these premises is crucial to the realization and implementation of the principle of equality. The State is committed to protect and guarantee the principle of equality under the Constitution and under her international obligations under principal human rights conventions. Malaysia, since 1995, is party to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Introduction

The principle of equality is the most fundamental of human rights and has been described as the “starting point of all liberties”. [1] International human rights law reflects this belief. Art.3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 (UDHR) declares that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. The UDHR is not a treaty but it embodies a moral authority and sets out a common standard of achievement of all peoples and nations. [2] The UDHR is the root document from which the international human rights treaties have grown.

The International Bill of Rights comprises of the UDHR, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

The ICCPR and the ICESCR are binding international treaties of which Malaysia is not a party to. The ICCPR obliges States Parties to guarantee in law the same civil and political rights that appear in the UDHR and to provide the means of fully enforcing them. The ICESCR obliges States Parties to progressively realize social and economic rights.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 1979 (CEFDAW) is a women’s rights instrument. It contains elements of both civil and political rights, and economic, social and cultural rights. Malaysia has signed and ratified CEFDAW in 1995. [3]

It was in furtherance to Malaysia’s commitment to CEFDAW that Art. 8 (2) of the Federal Constitution was amended in July 2001 to include gender as a basis for non–discrimination. [4]

Sex And Gender Theory

Art. 8 (1) of the Federal Constitution reads: All persons are equal before the law and entitled to equal protection of the law.

Art 8 (2) reads: Except as expressly authorized by this Constitution, there shall be no discrimination against citizens on the ground only of religion, race, descent, place of birth or gender in any law or in the appointment under a public authority or in the administration of any law relating to the acquisition, holding or disposition of property or the establishing or carrying on of any trade, business, profession, vocation or employment. (emphasis added).

Art. 1 of CEFDAW reads: For the purposes of the present Convention, the term “discrimination against women”, shall mean any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women , of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field. (emphasis added).

It is useful to clarify key terms.

Sex refers to the biological distinctions between men and women, the most obvious differences being the reproductive organs. To use sex as a variable means to ask whether it makes a difference whether the actor or subject is (biological) male or (biological) female. In gender theory, this ought to mean asking whether biological differences alone (be they hormonal, muscular or variations in height/weight/body etc) make a difference.

Gender is a more complicated concept than sex. Where sex is about maleness or femaleness (measured in biological difference), gender is about masculinity and femininity, measured in socially constructed and contextually contingent ideas about what attitudes and behaviors correspond to ideal–type maleness or femaleness. Gender rests not on biological sex differences but on interpretations of behavior that are culturally associated with sex differences. [5]

Gender theory refers to the conceptual framework feminists have invented. Whatever its different prescriptions, feminism is a politics of protest directed at transforming the historically unequal power relationships between women and men. While feminist theory would not be possible without use of gender as an analytical tool, the use of gender theory does not by itself constitutes a feminist approach. What is uniquely feminist is the assumption and critique of women’s oppression. [6]

As gender is socially constructed, this means that it varies across cultures, times and between members of the same sex and varies between the sexes. [7] This means that there is nothing natural, inherent or biologically inevitable about social attributes, activities and behaviors that come to be defined as either masculine or feminine.

The underlying aim of the principle of gender equality (when it references women) [8] is the eradication of the disabilities that are imposed on women based on cultural definitions of her role in society, and not merely discrimination based on her biological–reproductive capacity or other biological traits. [9]

Women’s ability to exercise her rights is shaped not only by social constructions on sex differences, but also factors such as class, race, ethnicity, the role of the state in constructing gender ideologies and relations of power.

The inclusion of gender in Art 8 (2) read with Art. 8 (1) provides for the following:

non–discrimination against females on the basis of cultural definitions of her role in society;

non–discrimination against females on the basis of her biological sex difference;

non–discrimination against males on the basis of biological sex differences and interpretations of behavior that is culturally associated with sex differences.

Thus the women’s lobby has enshrined gender theory [10] (which includes feminist theory of women’s oppression and gender theory which includes viewing men as a subject of oppressive gender constructs), into the equality clause in Art. 8.

PART 1

Feminist Legal Theory

The issue of what constitutes equality for women and how they can achieve it is the heart of the feminist project. [11] Feminist legal scholarship is the process or development of using law to improve the position of women or to eliminate the constraints of gender on both sexes.

(i) Formal Equality Model

Formal equality assumes that equality is achieved if the law treats likes alike. Put in another way, an equal protection guarantee required only that similarly situated classes be treated similarly. Equality in this model is equated with sameness.

Only individuals who are the same are entitled to be treated equally. For example, qualified female and male lawyers may be admitted to the legal profession. As lawyers with the requisite qualifications, both male and females arguably are similarly situated. In this situation, it may be argued that there are no differences between male and female lawyers. This formal equality model has secured positive changes for women.

What if women and men are not similarly situated? For example, a term of employment allows the dismissal of female airline stewardesses who are pregnant. Here males and females are not similarly situated because only females can get pregnant as that is a sexual–biological difference between males and females.

Pregnant females can be dismissed under this standard. Males are never pregnant, so the question of dismissal on pregnancy does not arise. Females may argue that this discriminates between sexes. Under the formal equality model, this is not discrimination as like is treated alike.

Under this equality model, pregnant females and males are not the same, so different treatment (dismissal) is not discrimination. Put in another way, if pregnant females expect to be treated the same as man then they should not get pregnant. If they expect to be treated differently when pregnant, that is discrimination.

But females get pregnant. Preventing females from pregnancy is a condition which discriminates.

Feminists argue that under the sameness standard, women are always measured against men. Gender neutrality is simply the male standard. [12] Advantaged groups establish the norms for comparison. Women can fail the similarly–situated test by having a characteristic that is unique, or by being designated as “different” simply because they are relatively disadvantaged.

Thus when women and men are not identically situated as in the pregnancy example, the formal equality model does not help. In fact, it perpetuates discrimination. Women can be like men in the workplace (when they are not pregnant) but they can undergo reproductive experiences which can make them different.

Treating women the same as men or different from men (men as the comparator) do not produce satisfying results for women’s equality. To the extent that women are not like men or because society has assigned them a subordinate status, they cannot achieve equality through the application of formal equality.

(ii) Substantive Equality Model

The focus of a substantive equality model is not simply with equal treatment under the law. The focus is not sameness or difference, but rather with disadvantage.

The central inquiry of this model is whether the rule/practice in question contributes to the subordination of the disadvantaged group (women). Under this model, discrimination consists of treatment that disadvantages or further oppresses a group that has historically experienced institutional and systemic oppression. [13]

A substantive equality model is concerned with two factors:

equality of opportunity (and access)

equality of outcomes.

In realizing these twin objectives, women are not to be discriminated against because they are different to men. Differences are acknowledged.

However, the focus is not on whether women are different, but rather whether their treatment in law contributes to their historic and systemic disadvantage. Within thus model of equality, differential treatment may be required, not to perpetuate existing inequalities but to achieve and maintain a real state of effective equality.

In the pregnancy case, pregnancy cannot be penalized (dismissal). Such a term of employment is discriminatory because it does not recognize difference.

A substantive equality approach would require for example that an employer provide a temporary change of work location or duties for pregnant women (if her current duties might prove unsafe/hazardous) and a right of the employee to return to her former position following maternity leave. Thus different treatment or affirmative action may be required in a substantive equality approach to prevent discrimination.

As a substantive model of equality aims to correct structural discrimination, it makes no distinction where that discrimination takes place, whether in the private realms of the family or in the marketplace. Equality measures do not address just the law, it has to address the economic, social and political dimensions of the disadvantaged.

The Interpretation Of Equality Under Art. 8

Art. 8 (1) and (2) do not tell us about the specific content of equality. While equality is not defined, it has been the subject of interpretation.

Caselaw on Art. 8 have accepted the Aristotelian notion of equality that things that are alike should be treated alike. [14]

The Federal Court in the infamous case of the dismissal on ground of pregnancy, missed a golden opportunity to reverse the tide in favor of a globally accepted standard of substantive equality.

In Beatrice a/p A.T. Fernandez v Sistem Penerbangan Malaysia , [15] a decision handed down in March this year, the appellant did not resign after being pregnant contrary to a term stipulated in the collective agreement (CA) of the air carrier, which requires all stewardesses of a particular category to resign on becoming pregnant. The Federal Court in refusing leave for the appellant to appeal a Court of Appeal decision dismissing her application ruled that the term in the CA did not infringe Art. 8 inter alia on the technical ground that the amendment to Art. 8 (2) to include gender was made in 2001, the appellant being dismissed in 1991.

Further the court said, “ ..in construing Article 8 of the Federal Constitution, our hands are tied. The equal protection clause in Clause (1) of the Article 8 thereof extends only to persons in the same class. It recognizes that all persons by nature, attainment, circumstances and the varying needs of different classes of persons often require separate treatment. Regardless of how we try to interpret Art. 8…we could only come to the conclusion that there was obviously no contravention. ” [16]

It is unclear from the grounds of judgment if the court did apply its mind at all the requirements of the formal equality standard in identifying the comparator (the class of persons to whom the appellant is to be compared with) and why the appellant and the class of persons are not the same, in order to fulfill the like treated alike standard.

The court took a ‘protective’ pose to say that, “ it is not difficult to understand why airlines cannot have pregnant stewardesses working like other pregnant women employees. We take judicial notice that the nature of the job requires flight stewardesses to work long hours and often flying across different time zones. They have to do much walking on board flying aircraft. It is certainly not a conducive place for pregnant women to be. ”

The protection of pregnant women consideration did not result in any recommendation of a change of duties to accommodate sexual difference in the case. In other words, the appellant was made solely responsible for putting herself in the position which requires her resignation/dismissal.

From the preceding sections, it is submitted that the formal equality model of like treated alike does not eliminate discrimination against women and in fact can perpetuate discrimination of women. The formal equality modal was dominant at a point in time but has now been displaced with the substantive model of equality in most national jurisdictions globally through interpretation [17] and/or legislation. [18]

Compliance With Art. 8 Substantive Equality Standard And CEFDAW

A substantive equality approach has changed social, political and legal understandings (“equal before the law”, “equal protection under the law’) of what discrimination is and how it occurs. It has transformed the equality framework in grounding legal reasoning in the social realities of women and disadvantaged groups.

The substantive modal of equality is incorporated and promoted under CEFDAW through the recognition in its provisions that women are subordinated through the construction of stereotyped and subservient roles and the requirement that governments implement affirmative measures to overcome the historical disadvantage of women.

While Art. 8 addresses the judiciary in addressing and providing remedies to equality challenges, CEFDAW addresses governments and holds the executive responsible in complying with obligations through a reporting mechanism. [19]

CEFDAW requires States Parties to enact legal guarantees of equality and to provide the means of fully enforcing them. It obliges governments to guarantee women “the exercise and enjoyment “of these rights” (Art. 3 in Part 1 CEFDAW). Exercise of these rights means access to the use of rights by making adjudicative procedures for vindicating rights accessible, affordable and known. Enjoyment of these rights means actually experiencing the benefit of the right and/or having the content of the right made real in one’s life. [20]

The exercise and enjoyment of these rights obliges the government to go beyond mere statements in legal documents of its commitment to women’s equality. It obliges governments to ensure through law and other means the practical realization of women’s equality. Thus legislation is not the complete solution. Taking appropriate means include designing and implementing programs or allocating resources. Governments are required to act not just refraining from discriminating.

The government has to eliminate structural discrimination (including the historical disadvantage of women) in all fields, including the political, economic, social and cultural fields. Part III CEFDAW details specific measures in access to work, remuneration, social security, pregnancy and maternity, education, health care and living conditions.

CEFDAW extinguishes the split between public and private spheres. It addresses the family and obliges the government to eliminate discrimination by “any person, or organisation or enterprise”. [21]

“Sharia’ Law” Reservations And “Personal Law” Restrictions To Women’s Equality

This paper will be referring to the government’s claims to qualify CEFDAW’s application in relation to Islamic law and the constitutional qualifications of “personal law” to Art. 8. This approach is selected due to the increasing political significance of Islam and Islamic law in Malaysia. [22] For purposes of consistency, the terms Syariah and Islamic law would be used for this paper and distinguished where relevant.

It should be noted at the outset (my explanations follow), that :–

equality under the Federal Constitution is qualified by Islamic law and doctrine;

and CEFDAW is qualified by Islamic law and the Federal Constitution (Islamic law and doctrine).

It seems an oxymoron that an international covenant should be limited by a national constitution when that international covenant has an objective to secure state compliance to its provisions.

The accession statement to CEFDAW on Islamic law appears to be a blanket qualification. [23] This means that regardless of the fact that Malaysia is not homogeneously Muslim, the government of Malaysia may not implement CEFDAW if there is a conflict between CEFDAW and Islamic law. The statement uses the term “Islamic Sharia’ law” which is rendered in this discussion henceforth as Islamic law and not Islam per se.

Malaysia registered her reservations at accession declaring that “Malaysia's accession is subject to the understanding that the provisions of the Convention do not conflict with the provisions of the Islamic Sharia' law and the Federal Constitution of Malaysia.” [24]

In addition to the statement on the Syariah, Malaysia has retained her reservations to Art. 5 (a), 7 (b), 9 (2), 16 (1) (a),(c),(f) and (g) and Art. 16 (2). [25] This paper will not cover a discussion these reserved articles and the implications thereof. [26]

The Federal Constitution does not allow the entire Art. 8 to invalidate or prohibit anything covered in Art. 8 (5). In other words, clause (5) sets out “lawful discrimination” under the Constitution. In this regard, the writer confines herself to Art. 8 (5) (a) on personal law, specifically Islamic law. [27] Islamic law in this regard is construed as that which the federal and state legislature is competent to legislate upon as per the Federal Constitution.

Art. 8 (2) is further qualified by any provision on discrimination which is so expressed in the Constitution. “Lawful discrimination” in this case refers to Art. 152 and Art. 153 on Malay Language, the special position of the Malays (special privileges of Malays and the Malay Rulers) and natives of Sabah and Sarawak. This point is also beyond the scope of this paper.

Art. 74 (2) of the Federal Constitution empowers the State Legislature to make laws on any matter in the State List in the Ninth Schedule. Item 1 of the State List allows the State Legislature to make laws inter alia on “Islamic law and personal and family law of persons professing the religion of Islam”.

The State Legislature however has no power to make law “in respect of offences except in so far as conferred by federal law, the control of propagating doctrines and beliefs among persons professing the religion of Islam; the determination of matters of Islamic law and doctrine and Malay custom”. (emphasis added). Such a power is vested only in Parliament.

Thus, personal law as Islamic law covers both Islamic law and Islamic doctrine under the Federal Constitution. Thus construed, Art. 8 (1) cannot invalidate or prohibit Islamic law and Islamic doctrine.

A question arises at this point if Islamic law is limited to legislated law or law passed by Parliament and State Legislatures or whether it covers general Islamic law. There is a view that the latter is covered. [28]

In any case, for the purpose of this discussion as Islamic doctrine is a legitimate matter for Parliament to legislate upon, the paper will proceed on the following basis:

that CEFDAW is made subject to the no–conflict rule to Islamic law (“Islamic Sharia’ law) and the Federal Constitution,

that both CEFDAW and Art. 8 are subject to the no–conflict rule to legislated Islamic law, general Islamic law and Islamic doctrine.

Universalism, Cultural Relativism And Fundamentalism

The no–conflict rule becomes problematic if CEFDAW and Art. 8 are incompatible with Islam, Islamic law and Islamic doctrine. If that is the case, then the substantive equality standard and the measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women under CEFDAW (and under principal human rights covenants and principles), would fail.

There are two ways of working a resolution, either compelling compliance or exploring the avenue of redefining or transforming or reclaiming cultural understandings that would support or mirror compatibility.

In the last thirty years or so, the international community and human rights actors have lobbied at the national and international level for minimizing governments’ claim of cultural relativism in defense of non–compliance with universal standards of human rights.

When women’s human rights were accorded recognition as human rights at the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights, renewed efforts to eradicate claims of cultural relativism came to the fore. Work on lifting country reservations on CEFDAW based on cultural relativism arguments intensified. In many of these campaigns, cultural relativism was perceived as fundamentalism. [29]

The rational of a binding treaty such as CEFDAW, obliges States Parties to implement measures to eliminate discrimination in religious and customary practices. Malaysia like other Muslim majority countries have made reservations on inter alia Art. 16 CEFDAW, which concerns equality between men and women in all matters relating to marriage and family relations, which are governed in Malaysia for Muslims by Islamic law.

Human rights have searched for a universal sense of truth, values, ethics, morality and justice. Relativism is the view that this search is hopeless and futile because the concepts of truth and falsehood, rights and wrong, rights and duties can exist and be valid only within a specific context. Cultural relativism is derived from relativism and developed initially in reaction against Western assertions of cultural superiority. [30]

Cultural relativism has been invoked to support claims that international human rights norms should not apply, or should apply only with a special interpretation, as the norms are alien to the groups in question. In assertions, the claim is often made that values when based on religious values enjoy supremacy over international law.

“Fundamentalism” is a self–referencing term adopted by a group of Protestant Christians in 1920 who rallied behind a series of pamphlets called The Fundamentals (1910–1915). In time, the term “fundamentalism” took a pejorative hue in the United States, in political debates about the Equal Rights Amendments, abortion and prayer in schools indicating positions articulated by conservative Christian groups. By extension it has been used to refer to Muslims who reject Western secular modernism. It was used widely during the 1979 Iranian revolution. Issues of gender play a crucial role in the language of fundamentalism. What is championed is a divinely sanctioned vision of natural differences between the sexes that make it appropriate for women to live within boundaries that would be restrictive for men, and to live under men’s protection and even surveillance. [31]

Rights Require A Cultural Legitimacy For Compliance

International human rights law has not yet been applied effectively to redress the disadvantages and injustices experienced by women by reason only of their being women. In this sense, respect for human rights fails to be “universal”. [32]

The first Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, Radhika Coomaraswamy acknowledges the problem in a different way. She asks the question, “How can universal human rights be legtimised in radically different societies without succumbing to either homogenizing universalism or the paralysis of cultural relativism?” [33] She proposes that those in the West must guard against the idea that the West is progressive on women’s rights and the East is barbaric and backward.

Human rights ought by definition to be universal in concept, scope and content as well as in application: a globally accepted set of rights or claims to which all human beings are entitled by virtue of their humanity and without distinction on grounds such as race, gender or religion. Yet there can be no prospect of the universal application of such rights unless there is, at least, substantial agreement on their concept, scope and content. [34] International human rights norms require a cultural legitimacy among Muslims and Muslim–majority states. [35]

The need to locate cultural legitimacy for human rights standards becomes imperative when the practical implementation of these norms (the States Parties’ obligation to implement measures to eliminate discrimination), requires voluntary compliance and cooperation by governments.

“Secular scholars of religion” or “religiously committed scholars and lay persons”, who are involved in projects on religion and human rights say that there is no “abyss separating the two realms”. The dreams and goals of those who pursue and defend human rights are clear echoes of ancient prophetic voices which also hoped for an ideal society based on justice and truth. The laying bare of assumptions and premises of each system (religious tradition and modern human rights) and examination of those premises will allow a contemplation of a fruitful intersection. [36]

The Project on Religion and Human Rights [37] has developed a framework to resolve issues of universalism and cultural relativism. I am sharing this approach as I have found the framework relevant in debating rights and religion as well.

The Project identified three broad and fundamental dimensions as follows: (1) levels of discourse, (2) perspectives of speakers, and (3) cultural complexity.

(1) Levels of discourse:

The tension between rights and religion does not invalidate the universality of human rights and it does not also imply moral bankruptcy. An investigation of tension may call for the development of creative strategies for universalizing such standards which acknowledge and engage seriously the cultural perspectives of traditions committed to diverse premises and world views. [38]

The exploration of such strategies will help promote popular legitimacy for human rights. This will generate the political will to enact and implement human rights standards and achieve a sufficient level of voluntary compliance for enforcement to be effective. No system of enforcement can cope with massive and persistent violations of its normative standards. Thus voluntary compliance must be the rule rather than the exception.

(2) Perspectives of Speakers:

The speakers are of three types (i) state actors, (ii) NGOs, religious representatives, individual actors, and (iii) the oppressed, both individually and collectively, and women. There are critical questions to ask of speakers’ positions (e.g., powerful or powerless?), representation (e.g., on whose behalf?), language and collateral behavior (e.g., are actions consonant with discourse?)

State actors speak from a position of political power and often represent themselves as speaking on behalf of an entire nation or an entire culture. Their actions belie the sincerity of their motives and their discourse and their language of relativism is often used as a screen to perpetrate and defend human rights violations. Thus there is reason to be skeptical about appeals by undemocratic states to cultural relativism.

The third class of speakers, the ones whose rights are violated by invocation of culture and religion are often drowned out. These voices and perspectives have to be taken into account as authentic witnesses to oppression. [39]

(3) Cultural complexity:

When governments invoke cultural pretexts for denying rights, it appears as though there is a unitary, monolithic culture that is shared by its citizens. This is not the case as every society and every culture is comprised of diverse views about significant issues of human of human life and human well–being, including of course, issues of human rights.

In Muslim societies, there is a significant group of people comprising of clerics and religious leaders who are more familiar with their own cultural traditions. In these conversations, groups in support of international norms and groups familiar with their cultural traditions may have in common shared aspirations on rights and freedom. Their learning from each other (and from women) is often impeded by gaps in their respective discourses on universality and cultural relativism. Bridging this “discourse gap” becomes important and devising creative means to achieve this goal should be given priority. [40]

In working the cross–cultural and internal dialogue, rights advocates are cautioned to avoid the trap of totalizing cultures. This is to avoid colluding with state actors in their totalizing rhetoric, but more importantly, to continue fostering human rights dialogues internal to and between cultural traditions. [41] Thus religion and culture can be an agent for the promulgation of human rights norms. [42]

Scholars have thus maintained the position that religion and the international human rights regime are not incompatible. This is a work in progress and it becomes incumbent for secular and religious human rights scholars and activists to contextualize these efforts. [43]

This part of the paper hopes to contextualize the debate of women’s equal rights in Western feminist scholarship (developed from the 1970s) with that of the so–called “gender jihad” or “religious feminism”, more particularly Islamic feminism(s) of the 1990s.

The cross–cultural and internal dialogue (intra–faith) approaches continue among women human rights actors and religious and secular scholars. For a large segment of believers the search for an authentically–spiritual approach is part of the spiritual journey of the faith.

Feminism and feminist legal theory can be said to be based on analysis of gender rooted in patriarchal and capitalist relations. In this regard, the gender theory that informs the substantive equality standard is valid where society is organized along patriarchal and capitalist lines. The focus of analysis in feminist legal theory is on the ideological nature of law that is in the way in which law operates to reinforce unequal power relations by naturalizing and universalizing patriarchal and capitalist relations. [44]

In the course of the global discourse on rights, religion and fundamentalism, feminism and feminist legal theory on equality have been identified as “Western scholarship”. The question then arises if gender theory on sexual differences (which premises the substantive equality standard), is universal in its application to Muslim societies. This query has prompted Muslim women scholars to investigate claims of “inauthencity” and to find the meaning of Quranic discourses on gender.

Margot Badran writes that “feminisms” are produced in particular places and are articulated in local terms. Third World women for instance, locate struggles against insubordination and oppression within local liberation and religious reform movements. There are “globally scattered feminisms” and the claim that feminism is Western is essentialist in nature. Feminism is “a plant that only grows in its own soil.” [45]

Martha Nussbaum proposed a course of feminist practice that is “strongly universal, committed to cross–cultural norms of justice, equality, and rights, and at the same time sensitive to local particularity, and to the many ways in which circumstances shape not only options but also beliefs and practice.”Thus a “universalist feminism” need not be insensitive to difference or imperialistic. A particular type of universalism, framed in terms of general human powers and their development, offers us in fact the best framework within which to locate our thought about difference. [46]

Amina Wadud, a “pro–faith, pro–feminist academic and an activist creating reform”, writes that gender reform remains one of the most controversial and yet essential lenses through which topics of Islam and modernity have been approached. [47]

In her forthcoming book, Inside Gender Jihad, Women’s Reform in Islam, she explores “the legitimate articulations of indigenous Muslim intellectual and political confrontation to two influential epistemologies: Western discourse of globalization, democracy and human rights and progressive Islamic discourse that is creating a unique response to Islamic origins, historical and ideological development into a trajectory essential to an Islamically authentic and indigenous reconstruction of globalization, democracy and human rights”.

Wadud does not discount gender theory but her pro–faith journey in Gender Jihad emanates from the notion of the human being based on a relationship with the divine. Sacred systems are not incorrigibly patriarchal and beyond redemption. She “wrestles” with the “hegemony of male privilege in Islamic interpretation as patriarchal interpretation, which continuously leaves a mark on Islamic praxis and thought. Too many of the world’s Muslims cannot perceive a distinction between this interpretation and the divine will, leading to the truncated notion of divine intent….limited to the malestream perspective.” [48]

Equality And The Gender Construct In Islam

The Quranic story of human origins affirms that man is not made in the image of God and there is no flawed female helpmate extracted from him as an afterthought. When the proto–human soul ( nafs ) is brought into existence, its mate ( zawj ) is already part of the plan. The Quran treats women and men in exactly the same way. Whatever the Quran says about the relationship between God and the individual is not in gender terms. [49]

Scholars doing exegesis agree that the Quran is not a dual–gendered text that has male and female voices in it. Access to the divine discourse is mediated by humans and in gendered languages and historically its masculinist biases that have prevailed in exegesis because Muslim societies like other societies have patriarchal histories. [50]

The re–reading of text by women has also found a flaw in malestream interpretation methodology which promotes a gendered view of sexual difference. The locus classicus is the interpretation to Q 4:34.

There is no term in the Quran that indicates that child–bearing is a female’s primary function or that mothering is her exclusive role. Scholars note that verse 4:34 demonstrates a specific situation where when a female carries a child, her husband is enjoined to provide material support for her and the Quran renders this by the phrase, “Men are responsible ( qawwamua ‘ala ) women [on the basis] of what Allah has faddala [preferred] some of them over others, and [on the basis] of what they spend of their property for the support of women..”.

Patriarchal reading of 4:34 has lifted a particular specific context where men have to provide material support for childbearing women (the Quran does not assume that all women will bear children) into a universal principal. Malestream interpretation have rendered 4:34 and qiwamah as an unconditional preference of men over women or that men are superior to women (in strength and in reason). [51]

For example, the Organisation of Islamic Conference (OIC) has developed the Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam where it advocates that equality of women and men is not absolute. Art. 6 of the Cairo Declaration reads:

(a) Woman is equal to man in human dignity and has rights to enjoy as well as duties to perform; she has her own civil entity and financial independence, and the right to retain her name and lineage.

(b) The husband is responsible for the support for the welfare of the family.

Human rights scholars and ‘secular scholars of religion’ have found the guarantee of equality ‘in human dignity’ under the OIC Cairo Declaration as falling short of human rights guarantee under the ICCPR. [52] As equality and civil and cultural rights are enshrined in CEFDAW, the OIC Cairo Declaration falls short of CEFDAW as well.

Muslim scholars who support the no–absolute equality approach premise their view of male privilege on the ground that males provide material support for women (although the context is specific).

Wadud however renders 4:34 to mean that the qiwamah is neither biological or inherent but it is valuable and that in some circumstances some men may be responsible for some women and in other contexts, some women may be responsible for some men. The Quran suggests mutual responsibility between males and females. [53]

This view resonates with the view of the Human Rights Committee that “Equality during marriage implies that husband and wife should participate equally in responsibility and authority within the family.” [54]

Whatever may be the premises of the gender theorizing, this illustration of the universals and the specifics in exegetical work of Muslim scholars on 4:34, show that sexual difference does not call for discriminatory treatment. In particular contexts, a woman’s pregnancy require differential treatment (our pregnant stewardess example, supra ). Differences are recognized but not penalised.

It is not possible in this brief paper to illustrate the invaluable exegetical work of Muslim scholars in reading–out patriarchal interpretations from the text, contextually. The re–reading efforts are important in the evolution of normative principles which would form the premises of equality and equality standards in assessing discrimination against women.

The normative principles culled from a re–reading would have to be applied in the investigation of the no–conflict rule to Islam, Islamic law and doctrine as stated earlier.

It is the writer’s opinion that the re–reading of 4:34 does not compromise the notion of equality enshrined in CFEDAW and principal human rights conventions and the notion of a substantive equality standard.

The immediate tasks for human rights defenders would be the investigation of all the specific contexts and the universals and whether provisions in CEFDAW and national law and policy qualify as specific contingent situations or universals. This approach does not exhaust the exploration of other empowering methodology which promotes gender equality and justice.

With new approaches in culling normative principles which promote gender equality and justice, are in a position to investigate the various contexts of marriage and family relations, custody and guardianship rights, inheritance and property rights and a host of civil and political rights, and economic, social and cultural rights enshrined in CEFDAW and national law and policy.

The function of human rights in the discourse of human rights and religion is the exploration of the core–irreconcilable differences in religious values and to work through an internal dialogue with religion and cross–cultural exchanges to minimize the differences. The expansion of the penumbra for dialogue would help inform strategies and principles towards gender equality.

Bibliography

Abdullahi A. An Na’im ed., Human Rights in Cross–Cultural Perspectives (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1992)

––––––––“What do we mean by Universal? ”, Index on Censorship 4/5 1994. 120–128

–––––––– “Political Islam” , in Peter L. Berger ed., The Desecularisation of the World–Resurgent Religion and World Politics (Washington DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center, 1999)

––––––––, “The Interdependence of Religion, Secularism and Human Rights: Prospects for Muslim Societies” , Common Knowledge. Vol. 11:1 (Winter 2005)

––––––––– The Future of the Sharia Project (forthcoming)

Amina Wadud, Quran and Women: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Women’s Perspective . (Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit Fajar Bakti, 1992)

–––––––– Manuscript Proposal: Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam (2005) unpublished

–––––––– Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam (forthcoming) (One World Publications).

Asma Barlas, Believing Women in Islam: Unreading Patriarchal Interpretations of the Quran (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2002)

Azza Karam, Women, Islamisms and the State: Contemporary Feminisms in Egypt (New York: St Martins Press, 1998)

Catherine McKinnon, Feminism Unmodified (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1987)

Donna Sullivan, “Gender Equality and Religious Freedom ”, 24 N.Y.U.J Int’l L. & Pol. (1991–1992) 795–856. p. 797

––––––––, “ Commentary on the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women ”, in IIHR, Optional Protocol CEDAW . UNIFEM. 2000. 31–108.

John Kelsey eds. et. al ., Religion and Human Rights Project (New York: The Project on Religion and Human Rights, 1994)

John S. Hawley, “Fundamentalism”, in Courtney W. Howland ed., Religious Fundamentalisms and the Human Rights of Women (New York: St Martins Press, 1999) 3–8

Joseph Tussman eds. et.al., “The Equal Protection of Laws” , 37. Cal. L. Rev. 341 (1949)

Julie S. Peters, “Reconceptualising the Relationship between Religion, Women, Culture and Human Rights”, in Carrie Gustafson eds., et. al., Religion and Human Rights: Competing Claims? (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1998)

Margot Badran, “Islamic Feminism: What’s in a Name?” , Al–Ahram Weekly Online. January 2002 http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2002/569/cul.htm

––––––––“ Toward Islamic Feminisms: A Look at the Middle East”, in Asma Asfaruddin ed., Hermeneutics and Honor (London: Harvard University Press, 1998)

Martha C. Nussbaum, Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach (Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, 2000)

Mary J. Frug , Postmodern Legal Feminism (London: Routledge, 1992)

Martin E. Marty eds. et.al., The Fundamentalism Project, Fundamentalisms Observed (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999)

Mashood Baderin, International Human Rights and Islamic Law (Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2003)

Michael Singer, “Relativism, Culture, Religion and Identity”, in Courtney W. Howland ed., Religious Fundamentalisms and the Human Rights of Women (New York: St Martins Press, 1999) 45– 54

Michael S. Berger et. al., “Women in Judaism from the Perspective of Human Rights ”, in John Witte Jr eds., et.al., Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Religious Perspective s (The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 1996) 295–322

Radhika Coomaraswamy, “ Women, Ethnicity and the Discourse of Rights” , in Rebecca Cook ed., Human Rights of Women: National and International Perspectives (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994) 39–57

Ratna Kapur, “ On Women, Equality and the Constitution ”, NationalLawSchool Journal. Special Issue 1993. (Bangalore: NationalLawSchool of IndiaUniversity) 1–61.

––––––––– ed. et. al ., Subversive Sites: Feminist Engagements with Law in India (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1996)

R. Charli Carpenter, Gender Theory in World Politics: Contributions from a Non–Feminist Standpoint . http://www.isanet.org/archive/carpenter.html

Rebecca Cook, “State Accountability Under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women” , in Rebecca Cook ed., Human Rights of Women: National and International Perspectives (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994) 228–256

–––––––– “Women’s International Human Rights Law: The Way Forward” , in Rebecca Cook ed., Human Rights of Women: National and International Perspectives (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994) 3–36

Salbiah Ahmad, “Unveiling Religious Discrimination” , MALAYA! malaysiakini.com. 2004

–––––––– “Pregnant, Productive and Discriminated” , MALAYA! malaysiakini.com 2005

––––––––“ Islam in Malaysia: Constitutional and Human Rights Perspectives” , MWJHR (2005) vol. 2 Issue 1 http://www.bepress.com/mwjhr/vol2/iss/

––––––––“ The Other as the Enemy ”, MALAYA! malaysiakini.com. 2005

––––––––“ Safeguarding Pluralism” , MALAYA! malaysiakin.com. 2005

Shanthi Dairiam, The Status of CEDAW Implementation in ASEAN and Selected Muslim Countries . IWRAW–AP Occasional Papers No. 1 (Kuala Lumpur: IWRAW–AP, 2004)

Sheridan L.A. eds. et.al, The Constitution of Malaysia (Singapore: Malayan Law Journal, 1987)

Susan Waltz, “Universal Human Rights: The Contribution of Muslim States” , Human Rights Quarterly 26 92004) 799–844

Women’s Aid Organisation, Briefing Notes http://www.wao.org.my/news/20010905briefingnotes.htm

[1] Mashood Baderin, International Human Rights and Islamic Law. (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2003) p. 58 quoting Justice Tanaka in the South West Africa Cases [1966] ICJ Reports, p. 304.

[2] It is frequently supposed that Muslim states are either absent or have contested the process and project or played no significant role. However, see Susan Waltz, “Universal Human Rights: The Contribution of Muslim States ”, Human Rights Quarterly 26 (2004) 799–844. The United Nations has records of the contributions of Muslim–majority states and Muslim diplomats from 1946–1966 to the deliberations to the UDHR and the ICCPR (1966) and ICESCR (1966).

[3] CEFDAW was adopted as a treaty in 1979 after the ICCPR and ICESCR had come into force.

[4] Women’s groups in Malaysia had lobbied for the inclusion of both “sex” and “gender” to Art. 8 (2). http://www.wao.org.my/news/20010905briefingnotes.htm . It is the author’s position that while the ratification to CEFDAW by the government prompted the lobby for the 2001 amendment to Art. 8 (2), the notion of a substantive equality standard does not solely require CEFDAW for interpretation of that standard in the courts, which comes into play through the interpretation of “equal before the law” and “equal protection” under Art. 8 (1), a clause intact since independence in 1957.

[5] R. Charli Carpenter, Gender Theory in World Politics: Contributions from a Non–Feminist Standpoint . http://www.isanet.org/archive/carpenter.html p.4

[6] Carpenter, ibid. Carpenter emphasises that the application of the gender framework by non–feminists does not threaten the feminist normative debate, rather, it serves to validate feminist epistemology.

[7] The concept of gender helps explain variation across same–sex distributions, cultures and time periods. The concept of sex explains uniformity within same–sex distributions and variations between the sexes. Carpenter, ibid.

[8] The gender framework is not limited to explaining discrimination against women. Gender is not synonymous with women or women’s issues. A gender theory that focuses only on women and essentialises men leaves other topics on gender unexplored. Carpenter, ibid at p. 7

[9] Donna Sullivan, “ Gender Equality and Religious Freedom ”, 24. N.Y.U.J. Int’l L. & Pol. 797 (1991–1992) 795–856. p. 797 footnote 2.

[10] It is not however clear from the briefing note to the ministry concerned that the women’s lobby had this distinction in mind. http://www.wao.org.my/news/20010905briefingnotes.htm

[11] Mary J. Frug, Postmodern Legal Feminism. (London: Routledge. 1992) p.4

[12] Catherine McKinnon, Feminism Unmodified. (Cambridge, Mass: HarvardUniversity Press. 1987) p. 34

[13] Ratna Kapur eds. et.al., Subversive Sites: Feminist Engagements with Law in India . (New Delhi: Sage Publications.1996) p. 176–177.

[14] See for example PP v Khong Teng Khen [1976] 2 MLJ 166. The Malaysian courts’ articulation of equality standards fall short of the developments in this area worldwide. See Joseph Tussman and Jacobus tenBroek, “ The Equal Protection of Laws” , 37 Cal. L. Rev. 341 (1949). The arguments in Tussman and tenBroek for the formal equality standard are no longer followed in responsible jurisdictions committed to the fundamental principle of equality of all human beings.

[15] [2005] 2 CLJ 713.; http://www.kehakiman.gov.my/jugdment/fc/archive/07.06_08–51–2003(W).htm ; Salbiah Ahmad, “Pregnant, Productive and Discriminated” , MALAYA! malaysiakini.com. 2005

[16] The court also held that the CA is an agreement between private parties which takes it out of the purview of the equal protection clause.

[17] Art 8 (1) and (2) are in pari materia to Art. 14 and Art 15 (1) respectively of the Indian Constitution. Art. 15 (1) prohibits discrimination on grounds inter alia of sex. See Ratna Kapur, “ On Women, Equality and the Constitution” , NationalLawSchool Journal. Special Issue 1993. Bangalore: NationalLawSchool of IndiaUniversity. 1–61., where she did a critical study of the equality cases in the context of the formal and substantive equality modals and makes an argument for the adoption of the substantive equality standard.

[18] E.g. Section 15 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms which spells out (1) the right to equality before the law; (2) the right to equality under the law; (3) the right to equal protection of the law; and (4) the right to equal benefit of the law. Section 15 has been construed to address the substantive equality of women, people of color, aboriginal peoples and people with disabilities.

[19] Malaysia is not party to the Optional Protocol to CEFDAW. See Donna Sullivan, “ Commentary on the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women ”, in IIHR, Optional Protocol CEDAW . UNIFEM. 2000. 31–108.

[20] See Rebecca Cook, “ State Accountability Under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women ” in Rebecca Cook, ed., Human Rights of Women: National and International Perspectives. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994) at 230–39

[21] See General Recommendation No. 19 UN Doc. A/47/38 (1992) paragraph 19.

[22] Salbiah Ahmad, “ Islam in Malaysia, Constitutional and Human Rights Perspectives ,” MWJHR (2005) vol. 2 Issue 1 http://www.bepress.com/mwjhr/vol2/iss1/

[23] It can be argued that personal law as Islamic law in Art 8 (5) (a) should only apply to Muslims as per a reading of Art. 74(2) and Item 1 of the Ninth Schedule. Thus restrictions to equality under Islamic law (if any) should not apply to non–Muslims. The same cannot be said for the qualification to CEFDAW.

- A Organization of the Year Award 2012 (24 Oct 2012)

- Acceptance Speech by Lim Chee Wee, President, Malaysian Bar, at the United Nations Malaysia Organization of the Year Award 2012 Presentation Ceremony, Renaissance Hotel, Kuala Lumpur (24 Oct 2012)

- United Nations celebrates 67th anniversary (News Release: The Malaysian Bar presented UN Malaysia Award for its pivotal role in Malaysias democratic development)

What are the international justice norms? written by Tan Peek Guat, Sunday, July 20 2014 12:10 am

This article first appeared in Forum, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on April 1, 2019 - April 7, 2019

Heralded by the hashtag #balanceforbetter, this year’s International Women’s Day came with the call to create a gender-balanced working world. While balance is important for all workers throughout an organisation, it is particularly relevant to women who — much more so than their male colleagues — are often expected to strike a balance between career building and homemaking, between bringing home a pay cheque and bringing up the children, and even between ambition and compassion.

From a more practical perspective, gender balance means creating more equitable opportunities for women, particularly at the highest levels of an organisation. According to “The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Asia-Pacific”, a report published by McKinsey’s business and research arm, McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), women in the region continue to be concentrated in lower growth sectors and lower paying roles. The talent pipeline also narrows for women, with a drop-off of over 50% of representation from entry level to senior management.

Beyond the moral and ethical implications suggested by this imbalance, gender inequality puts corporations at a disadvantage. McKinsey research from our Women Matter series has shown that greater representation of women in senior corporate positions correlates to improved business performance. In essence, diversity leads to more dynamic discussions, a broader range of factors considered and healthy challenges to conventional thinking. The benefits apply to governments as well as private organisations. In short, gender equality at all levels is not just a moral and ethical imperative; it is also good for business and the economy.

Ultimately, measures that help promote gender balance — for instance, flexible hours and expanded parental leave — directly improve the work-life balance of all employees, female and male. These factors can be crucial as today’s top talent, often favoured with multiple opportunities, weigh work-life balance and other aspects of happiness more keenly than previous generations in choosing and staying with their employers.

Gender balance — a trisector effort

Much is at stake. MGI’s report has estimated that US$12 trillion can be added to global growth by advancing gender equality. According to the report, Malaysia has the potential to add US$50 billion a year to its gross domestic product by 2025, which would be an 8% increase over its business-as-usual trajectory.

Capturing these benefits requires not just a vision and a will but also proactive and focused measures. Governments, companies and society, which make up this trifecta, must work together to unlock this potential.

Malaysia has already taken steps to address sources of gender inequality. The United Nations has listed Malaysia as a leader in encouraging women to participate in science, and half of all researchers in Malaysia are women. In addition, in 2004, the government committed to filling at least 30% of key roles in the public sector with women, and in 2017, women comprised 36% of the public-sector workforce. Also, in 2015, the government mandated that women comprise at least 30% of the boards of large corporations by 2020, making it the only country in Asean with such a directive.

Despite these encouraging steps, women in Malaysia still face barriers. Persistent challenges facing women include the difficulties of juggling family responsibilities with paid work, traditional attitudes towards women, limited access to finances, inadequate parental leave policies and inadequate skills for the modern labour market.

Prioritising government action for gender equality

The first actor in the tripartite effort to encourage gender balance is the government, which must build on ongoing efforts to bring more women into the workforce and particularly into senior positions. In Malaysia, women account for 38% of the workforce, one percentage point higher than the 37% average in Asia-Pacific. They also contribute about 32% to Malaysia’s GDP, compared with 36% in Asia-Pacific. Along with building a more equitable workforce, bringing participation in the workforce by women closer to parity would have economic benefits.

To advance gender equality in Malaysia, measures should be taken that address gender stereotyping, sexual harassment, lack of women in leadership roles, support for pregnant women and balancing work and caregiving responsibilities, among other pressing issues. The Gender Equality Act was introduced in 2006 to protect women from discrimination through all stages of life and efforts are needed to finalise and implement its provisions.

The business case for gender equality

There is also a big role businesses can play to improve gender parity — pivotal of which is narrowing gaps in pay for equal work. A gender pay gap is a contributing factor to lower representation of women along the pipeline and this remains a problem in Malaysia, where women degree holders on average get only 76% of what men get paid, according to numbers released by the Department of Statistics in 2017.

Thankfully, both the government and private corporations within the country are stepping up efforts to drive change. For example, 30% Club Malaysia, a business group that campaigns for more female directors on company boards, has helped advance women in directorships and leadership positions and is on course to achieve 30% women on corporate boards by 2020. Their numbers have risen to 19.1% in 2017, up from 16.6% at end-2016. The club convenes women through roundtable sessions where several issues that women are facing are raised, including sourcing for board-ready women directors.