11 Facebook Case Studies & Success Stories to Inspire You

Published: August 05, 2019

Although Facebook is one of the older social media networks, it's still a thriving platform for businesses who want to boost brand awareness.

With over 2.38 billion monthly active users , you can use the platform to spread the word about your business in a number of different ways -- from photos or videos to paid advertisements.

Because there are so many marketing options and opportunities on Facebook, It can be hard to tell which strategy is actually best for your brand.

If you're not sure where to start, you can read case studies to learn about strategies that marketing pros and similar businesses have tried in the past.

A case study will often go over a brand's marketing challenge, goals, a campaign's key details, and its results. This gives you a real-life glimpse at what led a marketing team to reach success on Facebook. Case studies also can help you avoid or navigate common challenges that other companies faced when implementing a new Facebook strategy.

To help you in choosing your next Facebook strategy, we've compiled a list of 11 great case studies that show how a number of different companies have succeeded on the platform.

Even if your company has a lower budget or sells a different product, we hope these case studies will inspire you and give you creative ideas for your own scalable Facebook strategy.

Facebook Brand Awareness Case Studies:

During the 2017 holiday season, the jewelry company Pandora wanted to boost brand awareness in the German market. They also wanted to see if video ads could have the same success as their other Facebook ad formats.

They began this experiment by working with Facebook to adapt a successful TV commercial for the platform. Here's a look at the original commercial:

The ad was cut down to a 15-second clip which shows a woman receiving a Pandora necklace from her partner. It was also cropped into a square size for mobile users. Pandora then ran the ad targeting German audiences between the ages of 18-50. It appeared in newsfeeds and as an in-stream video ad .

Results: According to the case study , the video campaign lifted brand sentiment during the holiday season, with a 10-point lift in favorability. While Pandora or the case study didn't disclose how they measured their favorability score, they note that the lift means that more consumers favored Pandora over other jewelers because of the ad.

Financially, the campaign also provided ROI with a 61% lift in purchases and a 42% increase in new buyers.

Video can be memorable, emotional, and persuasive. While the case study notes that Pandora always had success with ads and purchases, the jeweler saw that a video format could boost brand awareness even further.

In just 15 seconds, Pandora was able to tell a short story that their target audience could identify with while also showing off their product. The increase in favorability shows that audiences who saw the ad connected with it and preferred the jeweler over other companies because of the marketing technique.

Part of Pandora's success might also be due to the video's platform adaptation. Although they didn't create a specific video for the Facebook platform, they picked a commercial that had already resonated with TV audiences and tweaked it to grab attention of fast-paced Facebook users. This is a good example of how a company can be resourceful with the content it already has while still catering to their online audiences.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame , a HubSpot customer, wanted to boost brand awareness and get more ticket purchases to their museum. Since they'd mainly used traditional customer outreach strategies in the past, they wanted to experiment with more ways of reaching audiences on social media.

Because the museum's social media team recognized how often they personally used Facebook Messenger, they decided to implement a messaging strategy on the Hall of Fame's official business page.

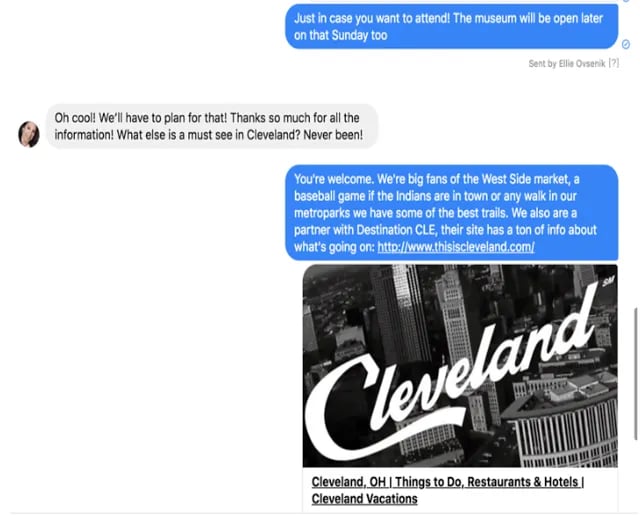

From the business page, users can click the Get Started button and open a chat with the Hall of Fame. Through the chat, social media managers were able to quickly reply to questions or comments from fans, followers, and prospective visitors. The reps would also send helpful links detailing venue pricing, events, other promotions, and activities in the surrounding area.

Since the Messenger launch, they claim to have raised their audience size by 81% and sales from prospects by 12%. The company claims that this feature was so successful that they even received 54 messages on an Easter Sunday.

Being available to connect with your audiences through Messenger can be beneficial to your business and your brand. While the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame boosted purchases, they also got to interact with their audiences on a personal level. Their availability might have made them look like a more trustworthy, friendly brand that was actually interested in their fanbase rather than just sales.

Facebook Reach Case Study:

In early 2016, Buffer started to see a decline in their brand reach and engagement on Facebook due to algorithm changes that favored individuals rather than brands. In an effort to prevent their engagement and reach numbers from dropping even further.

The brand decided to cut their posting frequency by 50%. With less time focused on many posts, they could focus more time on creating fewer, better-quality posts that purely aimed at gaining engagement. For example, instead of posting standard links and quick captions, they began to experiment with different formats such as posts with multi-paragraph captions and videos. After starting the strategy in 2016, they continued it through 2018.

Here's an example of one an interview that was produced and shared exclusively on Facebook.

The Results: By 2018, Buffer claimed that the average weekly reach nearly tripled from 44,000 at the beginning of the experiment to 120,000. The page's average daily engagements also doubled from roughly 500 per day to around 1,000.

In 2018, Buffer claimed that their posts reached between 5,000 to 20,000 people, while posts from before the experiment reached less than 2,000.

Although Buffer began the experiment before major Facebook algorithm changes , they updated this case study in 2018 claiming that this strategy has endured platform shifts and is still providing them with high reach and engagement.

It can be easy to overpost on a social network and just hope it works. But constant posts that get no reach or engagement could be wasted your time and money. They might even make your page look desperate.

What Buffer found was that less is more. Rather than spending your time posting whatever you can, you should take time to brainstorm and schedule out interesting posts that speak directly to your customer.

Facebook Video Views Case Studies:

Gearing up for Halloween in 2016, Tomcat, a rodent extermination company, wanted to experiment with a puppet-filled, horror-themed, live video event. The narrative, which was created in part by their marketing agency, told the story of a few oblivious teenage mice that were vacationing in a haunted cabin in the woods. At peak points of the story, audiences were asked to use the comments to choose which mouse puppet would die next or how they would die.

Prior to the video event, Tomcat also rolled out movie posters with the event date, an image of the scared mouse puppets, and a headline saying, "Spoiler: They all die!"

Results: It turns out that a lot of people enjoy killing rodents. The live video got over 2.3 million unique views , and 21% of them actively participated. As an added bonus, the video also boosted Tomcat's Facebook fanbase by 58% and earned them a Cyber Lion at the 2017 Cannes Lions awards.

Here's a hilarious sizzle reel that shows a few clips from the video and a few key stats:

This example shows how creative content marketing can help even the most logistical businesses gain engagement. While pest control can be a dry topic for a video, the brand highlighted it in a creative and funny way.

This study also highlights how interactivity can provide huge bonuses when it comes to views and engagement. Even though many of the viewers knew all the rats would die, many still participated just because it was fun.

Not only might this peak brand interest from people who hadn't thought that deeply about pest control, but interactivity can also help a video algorithmically. As more people comment, share, and react to a live video, there's more likelihood that it will get prioritized and displayed in the feeds of others.

In 2017, HubSpot's social media team embarked on an experiment where they pivoted their video goals from lead generation to audience engagement. Prior to this shift, HubSpot had regularly posted Facebook videos that were created to generate leads. As part of the new strategy, the team brainstormed a list of headlines and topics that they thought their social media audience would actually like, rather than just topics that would generate sales.

Along with this pivot, they also experimented with other video elements including video design, formatting, and size .

Results: After they started to launch the audience-friendly videos, they saw monthly video views jump from 50,000 to 1 million in mid-2017.

Creating content that caters to your fanbase's interests and the social platform it's posted on can be much more effective than content that seeks out leads.

While videos with the pure goal of selling a product can fall flat with views and engagement, creative videos that intrigue and inform your audiences about a topic they relate to can be a much more effective way to gain and keep your audience. Once the audience trusts you and consumes your content regularly, they might even trust and gain interest in your products.

Facebook App Installs Case Study:

Foxnext games.

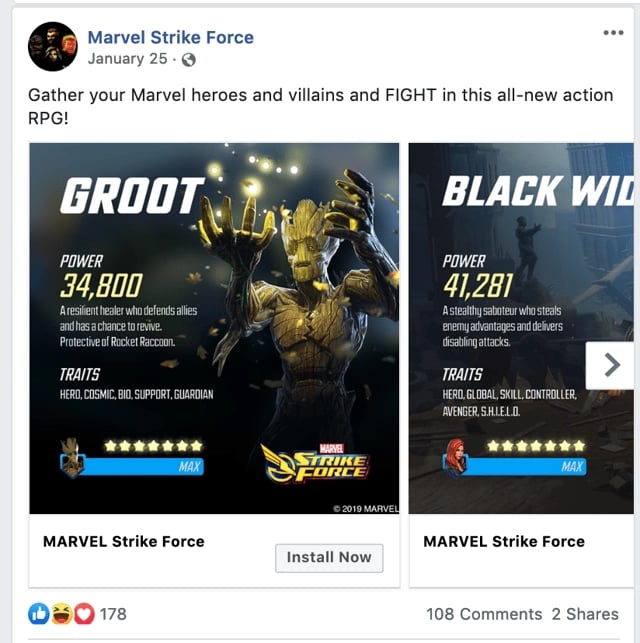

FoxNext Games, a video game company owned by 20th Century Fox, wanted to improve the level of app installs for one of its newest releases, Marvel Strike Force. While FoxNext had previously advertised other games with Facebook video ads, they wanted to test out the swipe-able photo carousel post format. Each photo, designed like a playing card, highlighted a different element of the game.

The add offered a call-to-action button that said "Install Now" and lead to the app store where it could be downloaded. FoxNext launched it on both Facebook and Instagram. To see if the carousel was more efficient than video campaigns, they compared two ads that advertised the same game with each format.

Results: According to Facebook , the photo ads delivered a 6% higher return on ad spend, 14% more revenue, 61% more installs, and 33% lower cost per app install.

Takeaways If your product is visual, a carousel can be a great way to show off different elements of it. This case study also shows how designing ads around your audience's interest can help each post stand out to them. In this scenario, FoxNext needed to advertise a game about superheroes. They knew that their fanbase was interested in gaming, adventure, and comic books, so they created carousels that felt more like playing cards to expand on the game's visual narrative.

Facebook Lead Gen Case Study:

Major impact media.

In 2019, Major Impact Media released a case study about a real-estate client that wanted to generate more leads. Prior to working with Major Impact, the Minneapolis, Minnesota brokerage hired another firm to build out an online lead generation funnel that had garnered them no leads in the two months it was active. They turned to Major Impact looking for a process where they could regularly be generating online leads.

As part of the lead generation process, the marketing and brokerage firms made a series of Facebook ads with the lead generation objective set. Major Impact also helped the company build a CRM that could capture these leads as they came in.

Results: Within a day, they received eight leads for $2.45 each. In the next 90 days, the marketing firm claimed the ads generated over 370 local leads at the average cost of $6.77 each. Each lead gave the company their name, email, and phone number.

Although these results sound like a promising improvement, readers of this case study should keep in mind that no number of qualified leads or ROI was disclosed. While the study states that leads were gained, it's unclear which of them lead to actual sales -- if any.

This shows how Facebook ad targeting can be helpful when you're seeking out leads from a specific audience in a local area. The Minneapolis brokerage's original marketing and social media strategies weren't succeeding because they were looking for a very specific audience of prospective buyers in the immediate area.

Ad targeting allowed their posts to be placed on the news feeds of people in the area who might be searching for real estate or have interests related to buying a home. This, in turn, might have caused them more success in gaining leads.

Facebook Engagement Case Study:

When the eyewear brand Hawkers partnered up with Spanish clothing brand El Ganso for a joint line of sunglasses, Hawkers' marketing team wanted to see which Facebook ad format would garner the most engagement. Between March and April of 2017, they launched a combination of standard ads and collection ads on Facebook.

While their standard ads had a photo, a caption and a call-to-action linking to their site, the collection ads offered a header image or video, followed by smaller images of sunglasses from the line underneath.

Image from Digital Training Academy

To A/B test ad effectiveness of the different ad types, Hawkers showed half of its audience standard photo ads while the other half were presented with the collection format. The company also used Facebook's Audience Lookalike feature to target the ads their audiences and similar users in Spain.

Results: The collection ad boosted engagement by 86% . The collection ads also saw a 51% higher rate of return than the other ads.

This study shows how an ad that shows off different elements of your product or service could be more engaging to your audience. With collection ads, audiences can see a bunch of products as well as a main image or video about the sunglass line. With a standard single photo or video, the number of products you show might be limited. While some users might not respond well to one image or video, they might engage if they see a number of different products or styles they like.

Facebook Conversion Case Study:

Femibion from merck.

Femibion, a German family-planning brand owned by Merck Consumer Health, wanted to generate leads by offering audiences a free baby planning book called "Femibion BabyPlanung." The company worked with Facebook to launch a multistage campaign with a combination of traditional image and link ads with carousel ads.

The campaign began with a cheeky series of carousel ads that featured tasteful pictures of "baby-making places," or locations where women might conceive a child. The later ads were a more standard format that displayed an image of the book and a call-to-action.

When the first ads launched in December 2016, they were targeted to female audiences in Germany. In 2017, during the later stages of the campaign, the standard ads were retargeted to women who had previously interacted with the carousel ads. With this strategy, people who already showed interest would see more ads for the free product offer. This could cause them to remember the offer or click when they saw it a second time.

Results: By the time the promotion ended in April 2017, ads saw a 35% increase in conversion rate. The company had also generated 10,000 leads and decreased their sample distribution cost by two times.

This case study shows how a company successfully brought leads through the funnel. By targeting women in Germany for their first series of creative "baby-making" ads, they gained attention from a broad audience. Then, by focusing their next round of ads on women who'd already shown some type of interest in their product, they reminded those audiences of the offer which may have enabled those people to convert to leads.

Facebook Product Sales Case Study

In an effort to boost sales from its Latin American audiences, Samsung promoted the 2015 Argentina launch of the Galaxy S6 smartphone with a one-month Facebook campaign.

The campaign featured three videos that highlighted the phone's design, camera, and long battery life respectively.

One video was released each week and all of them were targeted to men and women in Argentina. In the fourth week of the campaign, Samsung launched more traditional video and photo ads about the product. These ads were specifically targeted to people who'd engaged with the videos and their lookalike audiences.

Results: Samsung received 500% ROI from the month-long campaign and a 7% increase in new customers.

Like Femibion, Samsung tested a multiple ad strategy where the targeting got more specific as the promotions continued. They too saw the benefit of targeting ads to users who already showed interest in the first rounds of advertisements. This strategy definitely seems like one that could be effective when trying to gain more qualified leads.

Facebook Store Visits Case Study:

Church's chicken.

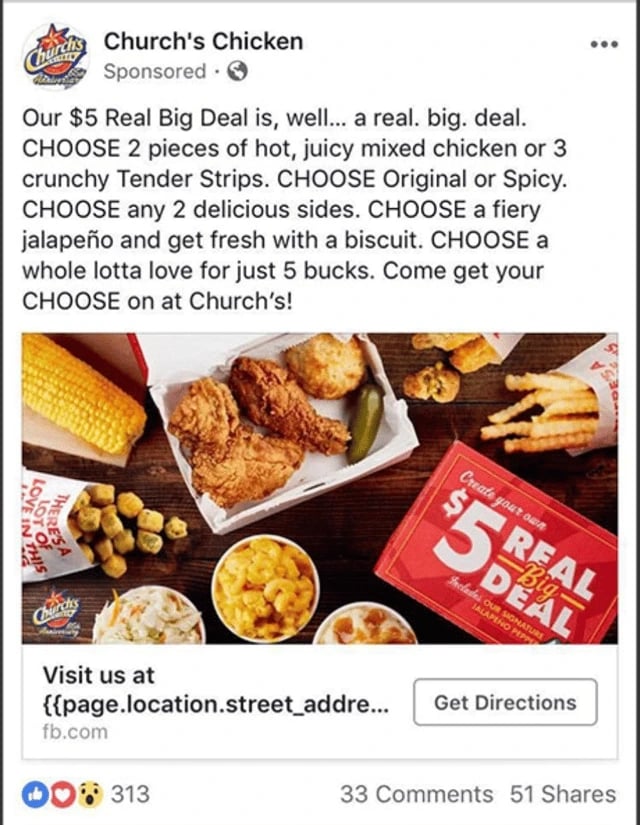

The world's third-largest chicken restaurant, Church's Chicken, wanted to see if they could use Facebook to increase in-restaurant traffic. From February to October of 2017, the chain ran a series of ads with the "Store Traffic" ad objectives. Rather than giving customers a link to a purchasing or order page, these ads offer users a call-to-action that says "Get Directions." The dynamic store-traffic ad also gives users the store information for the restaurant closest to them.

Image from Facebook

The ads ran on desktop and mobile newsfeeds and were targeted at people living near a Church's Chicken who were also interested in "quick-serve restaurants." The study also noted that third-party data was used to target customers who were "big spenders" at these types of restaurants.

To measure the results, the team compared data from Facebook's store-reporting feature with data from all of its locations.

Results: The ads resulted in over 592,000 store visits with an 800% ROI. Each visit cost the company an average of $1.14. The ROI of the campaign was four times the team's return goal.

If you don't have an ecommerce business, Facebook ads can still be helpful for you if they're strategized properly. In this example, Church's ads targeted locals who like quick-serve restaurants and served them a dynamic ad with text that notified them of a restaurant in their direct area. This type of targeting and ad strategy could be helpful to small businesses or hyperlocal businesses that want to gain foot traffic or awareness from the prospective customers closest to them.

Navigating Case Studies

If you're a marketer that wants to execute proven Facebook strategies, case studies will be incredibly helpful for you. If the case studies on the list above didn't answer one of your burning Facebook questions, there are plenty of other resources and success stories online.

As you look for a great case study to model your next campaign strategy, look for stories that seem credible and don't feel too vague. The best case studies will clearly go over a company's mission, challenge or mission, process, and results.

Because many of the case studies you'll find are from big businesses, you might also want to look at strategies that you can implement on a smaller scale. For example, while you may not be able to create a full commercial at the production quality of Pandora, you might still be able to make a lower-budget video that still conveys a strong message to your audience.

If you're interested in starting a paid campaign, check out this helpful how-to post . If you just want to take advantage of free options, we also have some great information on Facebook Live and Facebook for Business .

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

25 of the Best Facebook Pages We've Ever Seen

7 Brands With Brilliant Facebook Marketing Strategies, and Why They Work

10 Brands Whose Visual Facebook Content Tickles Our Funny Bone

9 Excellent Examples of Brands Using Facebook's New Page Design

6 Facebook Marketing Best Practices

Facebook Fan Page Best Practices with Mari Smith [@InboundNow #18]

7 Awesome B2B Facebook Fan Pages

Learn how to maximize the value of your marketing and ad spend on Meta platforms Facebook and Instagram.

Marketing software that helps you drive revenue, save time and resources, and measure and optimize your investments — all on one easy-to-use platform

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Michelle N. Meyer

Everything You Need to Know About Facebook's Controversial Emotion Experiment

The closest any of us who might have participated in Facebook's huge social engineering study came to actually consenting to participate was signing up for the service. Facebook's Data Use Policy warns users that Facebook “may use the information we receive about you…for internal operations, including troubleshooting, data analysis, testing, research and service improvement.” This has led to charges that the study violated laws designed to protect human research subjects. But it turns out that those laws don’t apply to the study, and even if they did, it could have been approved, perhaps with some tweaks. Why this is the case requires a bit of explanation.

#### Michelle N. Meyer

##### About

[Michelle N. Meyer](http://www.michellenmeyer.com/) is an Assistant Professor and Director of Bioethics Policy in the Union Graduate College-Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Bioethics Program, where she writes and teaches at the intersection of law, science, and philosophy. She is a member of the board of three non-profit organizations devoted to scientific research, including the Board of Directors of [PersonalGenomes.org](http://personalgenomes.org/).

For one week in 2012, Facebook altered the algorithms it uses to determine which status updates appeared in the News Feed of 689,003 randomly selected users (about 1 of every 2,500 Facebook users). The results of this study were just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

As the authors explain, “[b]ecause people’s friends frequently produce much more content than one person can view,” Facebook ordinarily filters News Feed content “via a ranking algorithm that Facebook continually develops and tests in the interest of showing viewers the content they will find most relevant and engaging.” In this study, the algorithm filtered content based on its emotional content. A post was identified as “positive” or “negative” if it used at least one word identified as positive or negative by software (run automatically without researchers accessing users’ text).

Some critics of the experiment have characterized it as one in which the researchers intentionally tried “to make users sad.” With the benefit of hindsight, they claim that the study merely tested the perfectly obvious proposition that reducing the amount of positive content in a user’s News Feed would cause that user to use more negative words and fewer positive words themselves and/or to become less happy (more on the gap between these effects in a minute). But that’s *not *what some prior studies would have predicted.

Previous studies both in the U.S. and in Germany had found that the largely positive, often self-promotional content that Facebook tends to feature has made users feel bitter and resentful---a phenomenon the German researchers memorably call “the self-promotion-envy spiral.” Those studies would have predicted that reducing the positive content in a user’s feed might actually make users less sad. And it makes sense that Facebook would want to determine what will make users spend more time on its site rather than close that tab in disgust or despair. The study’s first author, Adam Kramer of Facebook, confirms ---on Facebook, of course---that they did indeed want to investigate the theory that seeing friends’ positive content makes users sad.

To do so, the researchers conducted two experiments, with a total of four groups of users (about 155,000 each). In the first experiment, Facebook reduced the positive content of News Feeds. Each positive post “had between a 10-percent and 90-percent chance (based on their User ID) of being omitted from their News Feed for that specific viewing.” In the second experiment, Facebook reduced the negative content of News Feeds in the same manner. In both experiments, these treatment conditions were compared with control conditions in which a similar portion of posts were randomly filtered out (i.e., without regard to emotional content). Note that whatever negativity users were exposed to came from their own friends, not, somehow, from Facebook engineers. In the first, presumably most objectionable, experiment, the researchers chose to filter out varying amounts (10 percent to 90 percent) of friends’ positive content, thereby leaving a News Feed more concentrated with posts in which a user’s friend had written at least one negative word.

The results:

Boone Ashworth

Carlton Reid

Amanda Hoover

Reece Rogers

[f]or people who had positive content reduced in their News Feed, a larger percentage of words in people’s status updates were negative and a smaller percentage were positive. When negativity was reduced, the opposite pattern occurred. These results suggest that the emotions expressed by friends, via online social networks, influence our own moods, constituting, to our knowledge, the first experimental evidence for massive-scale emotional contagion via social networks.

Note two things. First, while statistically significant, these effect sizes are, as the authors acknowledge, quite small. The largest effect size was a mere two hundredths of a standard deviation (d = .02). The smallest was one thousandth of a standard deviation (d = .001). The authors suggest that their findings are primarily significant for public health purposes, because when the aggregated, even small individual effects can have large social consequences.

Second, although the researchers conclude that their experiments constitute evidence of “social contagion” ---that is, that “emotional states can be transferred to others”--- this overstates what they could possibly know from this study. The fact that someone exposed to positive words very slightly increased the amount of positive words that she then used in her Facebook posts does not necessarily mean that this change in her News Feed content caused any change in her mood . The very slight increase in the use of positive words could simply be a matter of keeping up (or down, in the case of the reduced positivity experiment) with the Joneses. It seems highly likely that Facebook users experience (varying degrees of) pressure to conform to social norms about acceptable levels of snark and kvetching---and of bragging and pollyannaisms. Someone who is already internally grumbling about how United Statesians are, like, such total posers during the World Cup may feel freer to voice that complaint on Facebook than when his feed was more densely concentrated with posts of the “human beings are so great and I feel so lucky to know you all---group hug! feel any worse than they otherwise would have, much less for any increase in negative affect that may have occurred to have risen to the level of a mental health crisis, as some have suggested.

One threshold question in determining whether this study required ethical approval by an Internal Review Board is whether it constituted “human subjects research.” An activity is considered “ research ” under the federal regulations, if it is “a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.” The study was plenty systematic, and it was designed to investigate the “self-promotion-envy spiral” theory of social networks. Check.

As defined by the regulations, a “human subject” is “a living individual about whom an investigator... obtains,” inter alia, “data through intervention.” Intervention, in turn, includes “manipulations of the subject or the subject’s environment that are performed for research purposes.” According to guidance issued by the Office for Human Research Protection s (OHRP), the federal agency tasked with overseeing application of the regulations to HHS-conducted and –funded human subjects research, “orchestrating environmental events or social interactions” constitutes manipulation.

I suppose one could argue---in the tradition of choice architecture---that to say that Facebook manipulated its users’ environment is a near tautology. Facebook employs algorithms to filter News Feeds, which it apparently regularly tweaks in an effort to maximize user satisfaction, ideal ad placement, and so on. It may be that Facebook regularly changes the algorithms that determine how a user experiences her News Feed.

Given this baseline of constant manipulation, you could say that this study did not involve any incremental additional manipulation. No manipulation, no intervention. No intervention, no human subjects. No human subjects, no federal regulations requiring IRB approval. But…

That doesn’t mean that moving from one algorithm to the next doesn’t constitute a manipulation of the user’s environment. Therefore, I assume that this study meets the federal definition of “human subjects research” (HSR).

Importantly---and contrary to the apparent beliefs of some commentators---not all HSR is subject to the federal regulations, including IRB review. By the terms of the regulations themselves , HSR is subject to IRB review only when it is conducted or funded by any of several federal departments and agencies (so-called Common Rule agencies), or when it will form the basis of an FDA marketing application . HSR conducted and funded solely by entities like Facebook is not subject to federal research regulations.

But this study was not conducted by Facebook alone; the second and third authors on the paper have appointments at the University of California, San Francisco, and Cornell, respectively. Although some commentators assume that university research is only subject to the federal regulations when that research is funded by the government, this, too, is incorrect. Any college or university that accepts any research funds from any Common Rule agency must sign a Federalwide Assurance (FWA) , a boilerplate contract between the institution and OHRP in which the institution identifies the duly-formed and registered IRB that will review the funded research. The FWA invites institutions to voluntarily commit to extend the requirement of IRB review from funded projects to all human subject research in which the institution is engaged, regardless of the source of funding. Historically, the vast majority of colleges and universities have agreed to “check the box,” as it’s called. If you are a student or a faculty member at an institution that has checked the box, then any HSR you conduct must be approved by an IRB.

As I recently had occasion to discover , Cornell has indeed checked the box ( see #5 here ). UCSF appears to have done so , as well, although it’s possible that it simply requires IRB review of all HSR by institutional policy, rather than FWA contract.

But these FWAs only require IRB review if the two authors’ participation in the Facebook study meant that Cornell and UCSF were “engaged” in research. When an institution is “engaged in research” turns out to be an important legal question in much collaborative research, and one the Common Rule itself doesn’t address. OHRP, however, has issued (non-binding, of course) guidance on the matter. The general rule is that an institution is engaged in research when its employee or agent obtains data about subjects through intervention or interaction, identifiable private information about subjects, or subjects’ informed consent.

According to the author contributions section of the PNAS paper, the Facebook-affiliated author “performed [the] research” and “analyzed [the] data.” The two academic authors merely helped him design the research and write the paper. They would not seem to have been involved, then, in obtaining either data or informed consent. (And even if the academic authors had gotten their hands on individualized data, so long as that data remained coded by Facebook user ID numbers that did not allow them to readily ascertain subjects’ identities, OHRP would not consider them to have been engaged in research.)

>Because the two academic authors merely designed the research and wrote the paper, they would not seem to have been involved, then, in obtaining either data or informed consent.

It would seem, then, that neither UCSF nor Cornell was "engaged in research" and, since Facebook was engaged in HSR but is not subject to the federal regulations, that IRB approval was not required. Whether that’s a good or a bad thing is a separate question, of course. (A previous report that the Cornell researcher had received funding from the Army Research Office, which as part of the Department of Defense, a Common Rule agency, would have triggered IRB review, has been retracted.) In fact, as this piece went to press on Monday afternoon, Cornell’s media relations had just issued a statement that provided exactly this explanation for why it determined that IRB review was not required.

Princeton psychologist Susan Fiske, who edited the PNAS article, told a Los Angeles Times reporter the following :

But then Forbes reported that Fiske “misunderstood the nature of the approval. A source familiar with the matter says the study was approved only through an internal review process at Facebook, not through a university Institutional Review Board.”

Most recently, Fiske told the Atlantic that Cornell's IRB did indeed review the study, and approved it as having involved a "pre-existing dataset." Given that, according to the PNAS paper, the two academic researchers collaborated with the Facebook researcher in designing the research, it strikes me as disingenuous to claim that the dataset preexisted the academic researchers' involvement. As I suggested above, however, it does strike me as correct to conclude that, given the academic researchers' particular contributions to the study, neither UCSF nor Cornell was engaged in research, and hence that IRB review was not required at all.

>It strikes me as disingenuous to claim that the dataset preexisted the academic researchers' involvement.

But if an IRB had reviewed it, could it have approved it, consistent with a plausible interpretation of the Common Rule? The answer, I think, is Yes, although under the federal regulations, the study ought to have required a bit more informed consent than was present here (about which more below).

Many have expressed outrage that any IRB could approve this study, and there has been speculation about the possible grounds the IRB might have given. The Atlantic suggests that the “experiment is almost certainly legal. In the company’s current terms of service, Facebook users relinquish the use of their data for ‘data analysis, testing, [and] research.’” But once a study is under an IRB’s jurisdiction, the IRB is obligated to apply the standards of informed consent set out in the federal regulations , which go well, well beyond a one-time click-through consent to unspecified “research.” Facebook’s own terms of service are simply not relevant. Not directly, anyway.

>Facebook’s own terms of service are simply not relevant. Not directly, anyway.

According to Prof. Fiske’s now-uncertain report of her conversation with the authors, by contrast, the local IRB approved the study “on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time.” This fact actually is relevant to a proper application of the Common Rule to the study.

Here’s how. Section 46.116(d) of the regulations provides:

An IRB may approve a consent procedure which does not include, or which alters, some or all of the elements of informed consent set forth in this section, or waive the requirements to obtain informed consent provided the IRB finds and documents that: 1. The research involves no more than minimal risk to the subjects; 2. The waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects; 3. The research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver or alteration; and 4. Whenever appropriate, the subjects will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation.

The Common Rule defines “minimal risk” to mean “that the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the research are not greater in and of themselves than those ordinarily encountered in daily life.” The IRB might plausibly have decided that since the subjects’ environments, like those of all Facebook users, are constantly being manipulated by Facebook, the study’s risks were no greater than what the subjects experience in daily life as regular Facebook users, and so the study posed no more than “minimal risk” to them.

That strikes me as a winning argument, unless there’s something about this manipulation of users’ News Feeds that was significantly riskier than other Facebook manipulations. It’s hard to say, since we don’t know all the ways the company adjusts its algorithms---or the effects of most of these unpublicized manipulations.

Even if you don’t buy that Facebook regularly manipulates users’ emotions (and recall, again, that it’s not clear that the experiment in fact did alter users’ emotions), other actors intentionally manipulate our emotions every day. Consider “ fear appeals ”---ads and other messages intended to shape the recipient’s behavior by making her feel a negative emotion (usually fear, but also sadness or distress). Examples include “scared straight” programs for youth warning of the dangers of alcohol, smoking, and drugs, and singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan’s ASPCA animal cruelty donation appeal (which I cannot watch without becoming upset—YMMV--and there’s no way on earth I’m being dragged to the “ emotional manipulation ” that is, according to one critic, The Fault in Our Stars).

Continuing with the rest of the § 46.116(d) criteria, the IRB might also plausibly have found that participating in the study without Common Rule-type informed consent would not “adversely effect the rights and welfare of the subjects,” since Facebook has limited users’ rights by requiring them to agree that their information may be used “for internal operations, including troubleshooting, data analysis, testing, research and service improvement.”

__Finally, the study couldn’t feasibly have been conducted with full Common Rule-style informed consent--which requires a statement of the purpose of the research and the specific risks that are foreseen--without biasing the entire study. __Of course, surely the IRB, without biasing the study, could have required researchers to provide subjects with some information about this specific study beyond the single word “research” that appears in the general Data Use Policy, as well as the opportunity to decline to participate in this particular study, and these things should have been required on a plain reading of § 46.116(d).

In other words, the study was probably eligible for “alteration” in some of the elements of informed consent otherwise required by the regulations, but not for a blanket waiver.

Moreover, subjects should have been debriefed by Facebook and the other researchers, not left to read media accounts of the study and wonder whether they were among the randomly-selected subjects studied.

Still, the bottom line is that---assuming the experiment required IRB approval at all---it was probably approvable in some form that involved much less than 100 percent disclosure about exactly what Facebook planned to do and why.

There are (at least) two ways of thinking about this feedback loop between the risks we encounter in daily life and what counts as “minimal risk” research for purposes of the federal regulations.

One view is that once upon a time, the primary sources of emotional manipulation in a person’s life were called “toxic people,” and once you figured out who those people were, you would avoid them as much as possible. Now, everyone’s trying to nudge, data mine, or manipulate you into doing or feeling or not doing or not feeling something, and they have access to you 24/7 through targeted ads, sophisticated algorithms, and so on, and the ubiquity is being further used against us by watering down human subjects research protections.

There’s something to that lament.

The other view is that this bootstrapping is entirely appropriate. If Facebook had acted on its own, it could have tweaked its algorithms to cause more or fewer positive posts in users’ News Feeds even *without *obtaining users’ click-through consent (it’s not as if Facebook promises its users that it will feed them their friends’ status updates in any particular way), and certainly without going through the IRB approval process. It’s only once someone tries to learn something about the effects of that activity and share that knowledge with the world that we throw up obstacles.

>Would we have ever known the extent to which Facebook manipulates its News Feed algorithms had Facebook not collaborated with academics incentivized to publish their findings?

Academic researchers’ status as academics already makes it more burdensome for them to engage in exactly the same kinds of studies that corporations like Facebook can engage in at will. If, on top of that, IRBs didn’t recognize our society’s shifting expectations of privacy (and manipulation) and incorporate those evolving expectations into their minimal risk analysis, that would make academic research still harder, and would only serve to help ensure that those who are most likely to study the effects of a manipulative practice and share those results with the rest of us have reduced incentives to do so. Would we have ever known the extent to which Facebook manipulates its News Feed algorithms had Facebook not collaborated with academics incentivized to publish their findings?

We can certainly have a conversation about the appropriateness of Facebook-like manipulations, data mining, and other 21st-century practices. But so long as we allow private entities to engage freely in these practices, we ought not unduly restrain academics trying to determine their effects. Recall those fear appeals I mentioned above. As one social psychology doctoral candidate noted on Twitter, IRBs make it impossible to study the effects of appeals that carry the same intensity of fear as real-world appeals to which people are exposed routinely, and on a mass scale, with unknown consequences. That doesn’t make a lot of sense. What corporations can do at will to serve their bottom line, and non-profits can do to serve their cause, we shouldn’t make (even) harder---or impossible---for those seeking to produce generalizable knowledge to do

- This post originally appeared on The Faculty Lounge under the headline How an IRB Could Have Legitimately Approved the Facebook Experiment—and Why that May Be a Good Thing .*

Emily Mullin

John Timmer, Ars Technica

Chris Baraniuk

Geraldine Castro

Lyndie Chiou

Everything We Know About Facebook’s Secret Mood-Manipulation Experiment

It was probably legal. But was it ethical?

Updated, 09/08/14

Facebook’s News Feed—the main list of status updates, messages, and photos you see when you open Facebook on your computer or phone—is not a perfect mirror of the world.

But few users expect that Facebook would change its News Feed in order to manipulate their emotional state.

We now know that’s exactly what happened two years ago. For one week in January 2012, data scientists skewed what almost 700,000 Facebook users saw when they logged into its service. Some people were shown content with a preponderance of happy and positive words; some were shown content analyzed as sadder than average. And when the week was over, these manipulated users were more likely to post either especially positive or negative words themselves.

This tinkering was just revealed as part of a new study , published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . Many previous studies have used Facebook data to examine “emotional contagion,” as this one did. This study is different because, while other studies have observed Facebook user data, this one set out to manipulate them.

The experiment is almost certainly legal. In the company’s current terms of service, Facebook users relinquish the use of their data for “data analysis, testing, [and] research.” Is it ethical, though? Since news of the study first emerged, I’ve seen and heard both privacy advocates and casual users express surprise at the audacity of the experiment.

In the wake of both the Snowden stuff and the Cuba twitter stuff, the Facebook “transmission of anger” experiment is terrifying. — Clay Johnson (@cjoh) June 28, 2014

Get off Facebook. Get your family off Facebook. If you work there, quit. They’re fucking awful. — Erin Kissane (@kissane) June 28, 2014

We’re tracking the ethical, legal, and philosophical response to this Facebook experiment here. We’ve also asked the authors of the study for comment. Author Jamie Guillory replied and referred us to a Facebook spokesman. Early Sunday morning, a Facebook spokesman sent this comment in an email:

This research was conducted for a single week in 2012 and none of the data used was associated with a specific person’s Facebook account. We do research to improve our services and to make the content people see on Facebook as relevant and engaging as possible. A big part of this is understanding how people respond to different types of content, whether it’s positive or negative in tone, news from friends, or information from pages they follow. We carefully consider what research we do and have a strong internal review process. There is no unnecessary collection of people’s data in connection with these research initiatives and all data is stored securely.

And on Sunday afternoon, Adam D.I. Kramer, one of the study’s authors and a Facebook employee, commented on the experiment in a public Facebook post. “And at the end of the day, the actual impact on people in the experiment was the minimal amount to statistically detect it,” he writes. “Having written and designed this experiment myself, I can tell you that our goal was never to upset anyone … In hindsight, the research benefits of the paper may not have justified all of this anxiety.”

Kramer adds that Facebook’s internal review practices have “come a long way” since 2012, when the experiment was run.

What did the paper itself find?

The study found that by manipulating the News Feeds displayed to 689,003 Facebook users, it could affect the content that those users posted to Facebook. More negative News Feeds led to more negative status messages, as more positive News Feeds led to positive statuses.

As far as the study was concerned, this meant that it had shown “that emotional states can be transferred to others via emotional contagion, leading people to experience the same emotions without their awareness.” It touts that this emotional contagion can be achieved without “direct interaction between people” (because the unwitting subjects were only seeing each others’ News Feeds).

The researchers add that never during the experiment could they read individual users’ posts.

Two interesting things stuck out to me in the study.

The first? The effect the study documents is very small, as little as one-tenth of a percent of an observed change. That doesn’t mean it’s unimportant, though, as the authors add:

Given the massive scale of social networks such as Facebook, even small effects can have large aggregated consequences … After all, an effect size of d = 0.001 at Facebook’s scale is not negligible: In early 2013, this would have corresponded to hundreds of thousands of emotion expressions in status updates per day .

The second was this line:

Omitting emotional content reduced the amount of words the person subsequently produced, both when positivity was reduced (z = −4.78, P < 0.001) and when negativity was reduced (z = −7.219, P < 0.001).

In other words, when researchers reduced the appearance of either positive or negative sentiments in people’s News Feeds—when the feeds just got generally less emotional—those people stopped writing so many words on Facebook.

Make people’s feeds blander and they stop typing things into Facebook.

Was the study well designed? Perhaps not, says John Grohol, the founder of psychology website Psych Central. Grohol believes the study’s methods are hampered by the misuse of tools: Software better matched to analyze novels and essays, he says, is being applied toward the much shorter texts on social networks.

Let’s look at two hypothetical examples of why this is important. Here are two sample tweets (or status updates) that are not uncommon: “I am not happy.” “I am not having a great day.” An independent rater or judge would rate these two tweets as negative—they’re clearly expressing a negative emotion. That would be +2 on the negative scale, and 0 on the positive scale. But the LIWC 2007 tool doesn’t see it that way. Instead, it would rate these two tweets as scoring +2 for positive (because of the words “great” and “happy”) and +2 for negative (because of the word “not” in both texts).

“What the Facebook researchers clearly show,” writes Grohol, “is that they put too much faith in the tools they’re using without understanding—and discussing—the tools’ significant limitations.”

Did an institutional review board (IRB)—an independent ethics committee that vets research that involves humans—approve the experiment?

According to a Cornell University press statement on Monday, the experiment was conducted before an IRB was consulted. * Cornell professor Jeffrey Hancock—an author of the study—began working on the results after Facebook had conducted the experiment. Hancock only had access to results, says the release, so “Cornell University’s Institutional Review Board concluded that he was not directly engaged in human research and that no review by the Cornell Human Research Protection Program was required.”

In other words, the experiment had already been run, so its human subjects were beyond protecting. Assuming the researchers did not see users’ confidential data, the results of the experiment could be examined without further endangering any subjects.

Both Cornell and Facebook have been reluctant to provide details about the process beyond their respective prepared statements. One of the study's authors told The Atlantic on Monday that he’s been advised by the university not to speak to reporters.

By the time the study reached Susan Fiske, the Princeton University psychology professor who edited the study for publication, Cornell’s IRB members had already determined it outside of their purview.

Fiske had earlier conveyed to The Atlantic that the experiment was IRB-approved.

“I was concerned,” Fiske told The Atlantic on Saturday , “ until I queried the authors and they said their local institutional review board had approved it—and apparently on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time.”

On Sunday, other reports raised questions about how an IRB was consulted. In a Facebook post on Sunday, study author Adam Kramer referenced only “internal review practices.” And a Forbes report that day, citing an unnamed source, claimed that Facebook only used an internal review.

When The Atlantic asked Fiske to clarify Sunday, she said the researchers’ “revision letter said they had Cornell IRB approval as a ‘pre-existing dataset’ presumably from FB, who seems to have reviewed it as well in some unspecified way … Under IRB regulations, pre-existing dataset would have been approved previously and someone is just analyzing data already collected, often by someone else.”

The mention of a “pre-existing dataset” here matters because, as Fiske explained in a follow-up email, “presumably the data already existed when they applied to Cornell IRB.” (She also noted: “I am not second-guessing the decision.”) Cornell’s Monday statement confirms this presumption.

On Saturday, Fiske said that she didn’t want the “the originality of the research” to be lost, but called the experiment “an open ethical question.”

“It’s ethically okay from the regulations perspective, but ethics are kind of social decisions. There’s not an absolute answer. And so the level of outrage that appears to be happening suggests that maybe it shouldn’t have been done … I’m still thinking about it and I’m a little creeped out, too.”

For more, check Atlantic editor Adrienne LaFrance’s full interview with Prof. Fiske .

From what we know now, were the experiment’s subjects able to provide informed consent?

In its ethical principles and code of conduct , the American Psychological Association (APA) defines informed consent like this:

When psychologists conduct research or provide assessment, therapy, counseling, or consulting services in person or via electronic transmission or other forms of communication, they obtain the informed consent of the individual or individuals using language that is reasonably understandable to that person or persons except when conducting such activities without consent is mandated by law or governmental regulation or as otherwise provided in this Ethics Code.

As mentioned above, the research seems to have been carried out under Facebook’s extensive terms of service. The company’s current data-use policy, which governs exactly how it may use users’ data, runs to more than 9,000 words and uses the word research twice. But as Forbes writer Kashmir Hill reported Monday night , the data-use policy in effect when the experiment was conducted never mentioned “research” at all— the word wasn’t inserted until May 2012 .

Never mind whether the current data-use policy constitutes “language that is reasonably understandable”: Under the January 2012 terms of service, did Facebook secure even shaky consent?

The APA has further guidelines for so-called deceptive research like this, where the real purpose of the research can’t be made available to participants during research. The last of these guidelines is:

Psychologists explain any deception that is an integral feature of the design and conduct of an experiment to participants as early as is feasible, preferably at the conclusion of their participation, but no later than at the conclusion of the data collection, and permit participants to withdraw their data.

At the end of the experiment, did Facebook tell the user-subjects that their News Feeds had been altered for the sake of research? If so, the study never mentions it.

James Grimmelmann, a law professor at the University of Maryland, believes the study did not secure informed consent. And he adds that Facebook fails even its own standards , which are lower than that of the academy:

A stronger reason is that even when Facebook manipulates our News Feeds to sell us things, it is supposed—legally and ethically—to meet certain minimal standards. Anything on Facebook that is actually an ad is labelled as such (even if not always clearly.) This study failed even that test, and for a particularly unappealing research goal: We wanted to see if we could make you feel bad without you noticing. We succeeded .

Did the U.S. government sponsor the research?

Cornell has now updated its June 10 story to say that the research received no external funding. Originally, Cornell had identified the Army Research Office, an agency within the U.S. Army that funds basic research in the military’s interest, as one of the funders of the experiment.

Do these kind of News Feed tweaks happen at other times?

At any one time, Facebook said last year, there were on average 1,500 pieces of content that could show up in your News Feed. The company uses an algorithm to determine what to display and what to hide.

It talks about this algorithm very rarely, but we know it’s very powerful. Last year, the company changed News Feed to surface more news stories. Websites like BuzzFeed and Upworthy proceeded to see record-busting numbers of visitors.

So we know it happens. Consider Fiske’s explanation of the research ethics here—the study was approved “on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time.” And consider also that from this study alone Facebook knows at least one knob to tweak to get users to post more words on Facebook.

* This post originally stated that an institutional review board, or IRB, was consulted before the experiment took place regarding certain aspects of data collection.

Adrienne LaFrance contributed writing and reporting.

Send us an email

How to write a social media case study (with template)

Written by by Jenn Chen

Published on October 10, 2019

Reading time 8 minutes

You’ve got a good number of social media clients under your belt and you feel fairly confident in your own service or product content marketing strategy. To attract new clients, you’ll tell them how you’ve tripled someone else’s engagement rates but how do they know this is true? Enter the case study.

Social media case studies are often used as part of a sales funnel: the potential client sees themselves in the case study and signs up because they want the same or better results. At Sprout, we use this strategy with our own case studies highlighting our customer’s successes.

Writing and publishing case studies is time intensive but straight forward. This guide will walk through how to create a social media case study for your business and highlight some examples.

What is a social media case study?

A case study is basically a long testimonial or review. Case studies commonly highlight what a business has achieved by using a social media service or strategy, and they illustrate how your company’s offerings help clients in a specific situation. Some case studies are written just to examine how a problem was solved or performance was improved from a general perspective. For this guide, we’ll be examining case studies that are focused on highlighting a company’s own products and services.

Case studies come in all content formats: long-form article, downloadable PDF, video and infographic. A single case study can be recycled into different formats as long as the information is still relevant.

At their core, case studies serve to inform a current or potential customer about a real-life scenario where your service or product was applied. There’s often a set date range for the campaign and accompanying, real-life statistics. The idea is to help the reader get a clearer understanding of how to use your product and why it could help.

Broad selling points like “our service will cut down your response time” are nice but a sentence like “After three months of using the software for responses, the company decreased their response time by 52%” works even better. It’s no longer a dream that you’ll help them decrease the response time because you already have with another company.

So now that you understand what a case study is, let’s get started on how to create one that’s effective and will help attract new clients.

How to write a social marketing case study

Writing an effective case study is all about the prep work. You’ve got to get all of the questions and set up ready so you can minimize lots of back and forth between you and the client.

1. Prepare your questions

Depending on how the case study will be presented and how familiar you are with the client to be featured, you may want to send some preliminary questions before the interview. It’s important to not only get permission from the company to use their logo, quotes and graphs but also to make sure they know they’ll be going into a public case study.

Your preliminary questions should cover background information about the company and ask about campaigns they are interested in discussing. Be sure to also identify which of your products and services they used. You can go into the details in the interview.

Once you receive the preliminary answers back, it’s time to prepare your questions for the interview. This is where you’ll get more information about how they used your products and how they contributed to the campaign’s success.

2. Interview

When you conduct your interview, think ahead on how you want it to be done. Whether it’s a phone call, video meeting or in-person meeting, you want to make sure it’s recorded. You can use tools like Google Meet, Zoom or UberConference to host and record calls (with your client’s permission, of course). This ensures that your quotes are accurate and you can play it back in case you miss any information. Tip: test out your recording device and process before the interview. You don’t want to go through the interview only to find out the recording didn’t save.

Ask open-ended questions to invite good quotes. You may need to use follow-up questions if the answers are too vague. Here are some examples.

- Explain how you use (your product or service) in general and for the campaign. Please name specific features.

- Describe how the feature helped your campaign achieve success.

- What were the campaign outcomes?

- What did you learn from the campaign?

Since we’re focused on creating a social media case study in this case, you can dive more deeply into social strategies and tactics too:

- Tell me about your approach to social media. How has it changed over time, if at all? What role does it play for the organization? How do you use it? What are you hoping to achieve?

- Are there specific social channels you prioritize? If so, why?

- How do you make sure your social efforts are reaching the right audience?

- What specific challenges do organizations like yours face when it comes to social?

- How do you measure the ROI of using social ? Are there certain outcomes that prove the value of social for your organization? What metrics are you using to determine how effective social is for you?

As the conversation continues, you can ask more leading questions if you need to to make sure you get quotes that tie these strategic insights directly back to the services, products or strategies your company has delivered to the client to help them achieve success. Here are just a couple of examples.

- Are there specific features that stick out to you as particularly helpful or especially beneficial for you and your objectives?

- How are you using (product/service) to support your social strategy? What’s a typical day like for your team using it?

The above quote was inserted into the Sprout Lake Metroparks case study . It’s an example of identifying a quote from an interview that helps make the impact of the product tangible in a client’s day to day.

At the end of the interview, be sure to thank the company and request relevant assets.

Afterwards, you may want to transcribe the interview to increase the ease of reviewing the material and writing the case study. You can DIY or use a paid service like Rev to speed up this part of the process.

3. Request assets and graphics

This is another important prep step because you want to make sure you get everything you need out of one request and avoid back and forth that takes up both you and your customer’s time. Be very clear on what you need and the file formats you need them in.

Some common assets include:

- Logo in .png format

- Logo guidelines so you know how to use them correctly

- Links to social media posts that were used during the campaign

- Headshots of people you interviewed

- Social media analytics reports. Make sure you name them and provide the requested date range, so that if you’re using a tool like Sprout, clients know which one to export.

4. Write the copy

Now that the information has been collected, it’s time to dissect it all and assemble it. At the end of this guide, we have an example outline template for you to follow. When writing a case study, you want to write to the audience that you’re trying to attract . In this case, it’ll be a potential customer that’s similar to the one you’re highlighting.

Use a mix of sentences and bullet points to attract different kinds of readers. The tone should be uplifting because you’re highlighting a success story. When identifying quotes to use, remove any fillers (“um”) and cut out unnecessary info.

5. Pay attention to formatting

And finally, depending on the content type, enlist the help of a graphic designer to make it look presentable. You may also want to include call-to-action buttons or links inside of your article. If you offer free trials, case studies are a great place to promote them.

Social media case study template

Writing a case study is a lot like writing a story or presenting a research paper (but less dry). This is a general outline to follow but you are welcome to enhance to fit your needs.

Headline Attention-grabbing and effective. Example: “ How Benefit turns cosmetics into connection using Sprout Social ” Summary A few sentences long with a basic overview of the brand’s story. Give the who, what, where, why and how. Which service and/or product did they use? Introduce the company Give background on who you’re highlighting. Include pertinent information like how big their social media team is, information about who you interviewed and how they run their social media. Describe the problem or campaign What were they trying to solve? Why was this a problem for them? What were the goals of the campaign? Present the solution and end results Describe what was done to achieve success. Include relevant social media statistics (graphics are encouraged). Conclusion Wrap it up with a reflection from the company spokesperson. How did they think the campaign went? What would they change to build on this success for the future? How did using the service compare to other services used in a similar situation?

Case studies are essential marketing and sales tools for any business that offer robust services or products. They help the customer reading them to picture their own company using the product in a similar fashion. Like a testimonial, words from the case study’s company carry more weight than sales points from the company.

When creating your first case study, keep in mind that preparation is the key to success. You want to find a company that is more than happy to sing your praises and share details about their social media campaign.

Once you’ve started developing case studies, find out the best ways to promote them alongside all your other content with our free social media content mix tool .

[Toolkit] Communications Toolkit to Safeguard Your Brand

Find Your Next Social Media Management Tool With This Scorecard

How to ladder up your brand’s social media maturity

3 Social media executives share what it takes to build a long-term career in social

- Data Report

- Social Media Content

The 2024 Content Benchmarks Report

Always up-to-date guide to social media image sizes

- Social Media Strategy

The power of frontline employee engagement on social media

- Marketing Disciplines

B2B content marketing: Ultimate strategy guide for 2024

- Now on slide

Build and grow stronger relationships on social

Sprout Social helps you understand and reach your audience, engage your community and measure performance with the only all-in-one social media management platform built for connection.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Facebook and Cambridge Analytica: What You Need to Know as Fallout Widens

By Kevin Granville

- March 19, 2018

Our report that a political firm hired by the Trump campaign acquired access to private data on millions of Facebook users has sparked new questions about how the social media giant protects user information.

Who collected all that data?

Cambridge Analytica, a political data firm hired by President Trump’s 2016 election campaign, gained access to private information on more than 50 million Facebook users. The firm offered tools that could identify the personalities of American voters and influence their behavior.

Cambridge has been largely funded by Robert Mercer, the wealthy Republican donor, and Stephen K. Bannon, a former adviser to the president who became an early board member and gave the firm its name. It has pitched its services to potential clients ranging from Mastercard and the New York Yankees to the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

On Monday, a British TV news report cast it in a harsher light, showing video of Cambridge Analytica executives offering to entrap politicians. A day later, as a furor grew, the company suspended its chief executive, Alexander Nix.

[Read more about how Cambridge Analytica and the Trump campaign became linked]

What kind of information was collected, and how was it acquired?

The data, a portion of which was viewed by The New York Times, included details on users’ identities, friend networks and “likes.” The idea was to map personality traits based on what people had liked on Facebook, and then use that information to target audiences with digital ads.

Researchers in 2014 asked users to take a personality survey and download an app, which scraped some private information from their profiles and those of their friends, activity that Facebook permitted at the time and has since banned.

The technique had been developed at Cambridge University’s Psychometrics Center. The center declined to work with Cambridge Analytica, but Aleksandr Kogan, a Russian-American psychology professor at the university, was willing.

Dr. Kogan built his own app and in June 2014 began harvesting data for Cambridge Analytica.

He ultimately provided over 50 million raw profiles to the firm, said Christopher Wylie, a data expert who oversaw Cambridge Analytica’s data harvesting. Only about 270,000 users — those who participated in the survey — had consented to having their data harvested, though they were all told that it was being used for academic use.

Facebook said no passwords or “sensitive pieces of information” had been taken, though information about a user’s location was available to Cambridge.

[Read more about the internal tension at the top of Facebook over the platform’s political exploitation]

So was Facebook hacked?

Facebook in recent days has insisted that what Cambridge did was not a data breach , because it routinely allows researchers to have access to user data for academic purposes — and users consent to this access when they create a Facebook account.

But Facebook prohibits this kind of data to be sold or transferred “to any ad network, data broker or other advertising or monetization-related service.” It says that was exactly what Dr. Kogan did, in providing the information to a political consulting firm.

Dr. Kogan declined to provide The Times with details of what had happened, citing nondisclosure agreements with Facebook and Cambridge Analytica.

Cambridge Analytica officials, after denying that they had obtained or used Facebook data, changed their story last week. In a statement to The Times, the company acknowledged that it had acquired the data, though it blamed Dr. Kogan for violating Facebook’s rules and said it had deleted the information as soon as it learned of the problem two years ago.

But the data, or at least copies, may still exist. The Times was recently able to view a set of raw data from the profiles Cambridge Analytica obtained.

What is Facebook doing in response?

The company issued a statement on Friday saying that in 2015, when it learned that Dr. Kogan’s research had been turned over to Cambridge Analytica, violating its terms of service, it removed Dr. Kogan’s app from the site. It said it had demanded and received certification that the data had been destroyed.

Facebook also said: “Several days ago, we received reports that, contrary to the certifications we were given, not all data was deleted. We are moving aggressively to determine the accuracy of these claims. If true, this is another unacceptable violation of trust and the commitments they made. We are suspending SCL/Cambridge Analytica, Wylie and Kogan from Facebook, pending further information.”

In a further step, Facebook said Monday that it had hired a digital forensics firm “to determine the accuracy of the claims that the Facebook data in question still exists.” It said that Cambridge Analytica had agreed to the review and that Dr. Kogan had given a verbal commitment, while Mr. Wylie “thus far has declined.”

[Read more about how to protect your data on Facebook]

What are others saying?

Facebook, already facing deep questions over the use of its platform by those seeking to spread Russian propaganda and fake news, is facing a renewed backlash after the news about Cambridge Analytica. Investors have not been pleased, sending shares of the company down more than 8 percent since Friday.

■The Federal Trade Commission said Tuesday it is investigating whether Facebook violated a 2011 consent agreement to keep users’ data private.

■ In Congress, Senators Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat from Minnesota, and John Kennedy, a Republican from Louisiana, have asked to hold a hearing on Facebook’s links to Cambridge Analytica. Republican leaders of the Senate Commerce Committee, led by John Thune of South Dakota, wrote a letter on Monday to Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, demanding answers to questions about how the data was collected.

■ A British Parliament committee sent a letter to Mr. Zuckerberg asking him to appear before the panel to answer questions on Facebook’s ties to Cambridge Analytica.

■ The attorney general of Massachusetts, Maura Healey, announced on Saturday that her office was opening an investigation. “Massachusetts residents deserve answers immediately from Facebook and Cambridge Analytica,” she said in a Twitter post . Facebook’s lack of disclosure on the harvesting of data could violate privacy laws in Britain and several states.

A Guide to Digital Safety

A few simple changes can go a long way toward protecting yourself and your information online..

A data breach into your health information can leave you feeling helpless. But there are steps you can take to limit the potential harm.

Don’t know where to start? These easy-to-follow tips and best practices will keep you safe with minimal effort.

Your email address has become a digital bread crumb that companies can use to link your activity across sites. Here’s how you can limit this .

Protect your most sensitive accounts by creating unique passwords and adding extra layers of verification .

There are stronger methods of two-factor authentication than text messages. Here are the pros and cons of each .

Do you store photos, videos and important documents in the cloud? Make sure you keep a copy of what you hold most dear .

Browser extensions are free add-ons that you can use to slow down or stop data collection. Here are a few to try.

TechRepublic

Account information.

Share with Your Friends

Facebook data privacy scandal: A cheat sheet

Your email has been sent

A decade of apparent indifference for data privacy at Facebook has culminated in revelations that organizations harvested user data for targeted advertising, particularly political advertising, to apparent success. While the most well-known offender is Cambridge Analytica–the political consulting and strategic communication firm behind the pro-Brexit Leave EU campaign, as well as Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign–other companies have likely used similar tactics to collect personal data of Facebook users.

TechRepublic’s cheat sheet about the Facebook data privacy scandal covers the ongoing controversy surrounding the illicit use of profile information. This article will be updated as more information about this developing story comes to the forefront. It is also available as a download, Cheat sheet: Facebook Data Privacy Scandal (free PDF) .

SEE: Navigating data privacy (ZDNet/TechRepublic special feature) | Download the free PDF version (TechRepublic)

What is the Facebook data privacy scandal?

The Facebook data privacy scandal centers around the collection of personally identifiable information of “ up to 87 million people ” by the political consulting and strategic communication firm Cambridge Analytica. That company–and others–were able to gain access to personal data of Facebook users due to the confluence of a variety of factors, broadly including inadequate safeguards against companies engaging in data harvesting, little to no oversight of developers by Facebook, developer abuse of the Facebook API, and users agreeing to overly broad terms and conditions.

SEE: Information security policy (TechRepublic Premium)