Advertisement

Gender-based violence and hegemonic masculinity in China: an analysis based on the quantitative research

- Survey Report

- Open access

- Published: 05 August 2019

- Volume 3 , pages 84–97, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Xiangxian Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6944-2948 1 ,

- Gang Fang 2 &

- Hongtao Li 3

12k Accesses

6 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Based on a survey implemented in a county in central China, the researchers found it is common for women to experience gender-based violence, especially violence at the hands of intimate partners. About half of men surveyed reported inflicting physical or sexual violence on their female partners. One in five men reported having raped a partner or non-partner woman. The physical, mental and reproductive health of the female and male respondents were found to be significantly associated with women’s victimization and men’s perpetration of intimate partner violence. Gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence, is a construction of the social-ecological system. Four elements that are key to hegemonic masculinity are identified: male decision-making, male reputation, violence and heterosexuality. By positing the four elements as standards that define a “real man”, the domination of men over women is naturalized and legitimized. It is necessary to foster other non-violent and more equitable masculinities.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the concept of intimate partner violence (IPV) against women arrived in China in the 1990s, surveys conducted by institutions like the Women’s Federation of China (Tao and Jiang 1993 ) and China Population and Development Research Center (Zheng and Xie 2004 ) have demonstrated that IPV is the most common form of violence against women in China. In the effort to eliminate the violence, Chinese scholars have taken into consideration a wide range of topics such as feminist law, ethnic minority issues, marriage markets and the imbalanced sex ratio in their studies of IPV against women (Gu 2014 ; Song and Zhang 2017 ; Dan 2018 ). While more and more international studies point to the strong connection between rigid hegemonic masculinities and violence against women (Schrock and Padavic 2007 ; Duncanson 2015 ; Cossins and Plummer 2018 ; Heilman and Barker 2018 ), this connection is neglected in China. Understanding gender based violence, especially IPV against women, from the perspective of hegemonic masculinities is thus the goal of our survey.

In May 2011, field research was carried out in a county in central China where the majority of the population lives in rural areas. By multiple stage random sampling, 67 communities were chosen and then 50 interviewees (25 women and 25 men) were randomly selected in each community. We had a response rate of 83.7%, with 1103 women and 1017 men aged 18–49 years completing the female and male questionnaires. Among the respondents, 97.8% of them are currently or have been partnered. The female and male questionnaires and research protocol were provided by the institutions that initiated and provided technical support for the survey. The implementation team made slight adjustments to the questionnaires based on Chinese and local contexts. Personal digital assistants were used to ensure that the responses of the interviewees were strictly confidential. Further information is provided in the Table 8 in Appendix (see Table 1 ).

2 Intimate partner violence against women

2.1 prevalence.

A breakdown of details reported by men follows in this paragraph. With respect to emotional violence, 28.6% of men reported deliberately frightening or intimidating their female partners, 22.4% reported insulting or deliberately making their partner feel bad about herself, and 14.2% reported deliberately degrading her in front of others. In terms of financial violence, the three most common items concerned men were forbidding women to find work or earn money (10.6%), male partners who spent their own earnings on alcohol and cigarettes although they knew their female partners could not support the family alone (7.7%), and forcing the female partner out of the place of residence (7.2%). In terms of physical violence, pushing or shoving was the most common type (32.8%), slapping or throwing things at women was second (29.8%), and striking women with fists was third (17.8%). With respect to sexual violence, the most common occurrence was the man insisting on sex when the female partner was unwilling, because the man felt entitled to sex with the woman who was his wife or girlfriend Footnote 1 (15.0%). In other cases the man physically forced his female partner to have sex (12.1%). Both of these behaviors are categorized as partner rape. In terms of the lifetime prevalence of partner rape, 14.3% of male respondents reported having perpetrated partner rape and 9.9% of female respondents reported being the victim. The items partner rape and males forcing female partners to watch phonography or perform sexual acts they do not want are classified as sexual violence. In addition, based on reports from women, the prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual violence inflicted by male partners during the female partner’s any of pregnancy were 13.1%, 3.6% and 5.5%, respectively.

Compared with to the instances of IPV documented above, men controlling the behavior of female partners was much more common. A total of 91.0% of men reported having done this at some point during their lives and 86.4% of women reported being controlled at some point. Among the specific items of men controlling the behavior of female partners, the most common is the male partner having more power to make big decisions (72.4%), followed by the male partner not allowing the female partner to wear certain items of clothing (45.8%) and getting angry if the female partner asks him to use a condom (40.3%).

Women often experience more than one type of IPV. Among women who reported experiencing emotional, financial, physical or sexual IPV, 43% of them experienced only one type, 30% experienced two types, 20% experienced three types and 8% experienced four types. Based on the reports of male perpetrators, the four percentage were 36%, 34%, 22% and 9%, respectively.

With respect to emotional, financial, physical and sexual IPV during the 12 months prior to the survey date, the prevalence of perpetrations reported by men were 19.1%, 10.5%, 14.4% and 7.5%, respectively, and the prevalence of victimizations reported by women were 10%, 6.9%, 6.8% and 3.3%, respectively.

2.2 Health consequences and seeking help

The statistics show the ratio of women injured from IPV was alarmingly high. Among 364 women who reported being victims of physical IPV, 40.7% (n = 148) suffered injuries including sprains, burns, knife cuts, bone fractures, lost teeth and other injuries, or had to receive medical care or be hospitalized. With respect to the severity of physical IPV injuries, 34.5% of 148 injured women were bedridden for a period of time, had to take work leave, or had to receive medical care. Beside these physical injures, IPV harmed women in other ways. Compared to women who never experienced IPV, the possibility that women who experienced IPV would suffer from mental and/or reproductive health problems was significantly higher (see Table 2 below).

Many women who are victims of IPV do not seek help. Among 364 women who reported experiencing physical IPV, 60% kept silent, only 6.6% reported the IPV to the police, 10% sought medical help and 36.8% told family members. Among 24 women who reported IPV to the police, 11 women did not report the details of how the police reacted to their reports, only one woman got the chance to open a court case, three women were sent away, and nine women were asked to compromise with their partners. Among the women who sought medical help, only half of them (n = 30) told the truth about how they had been injured. Of the 133 women who told family members about the IPV, nearly half of them (44.4%) were not supported by the family. Instead what they said was treated with indifference, or the family blamed the woman for causing the IPV or she was told to keep silent. In 24.8% of the cases, families were supportive, among other things, suggesting the women report the matter to the police. In 30.8% of the cases, the family’s reactions were ambiguous.

Women who claimed to be victims of rape or attempted rape by non-partners had similar experiences. Among 176 women who reported experiencing such violence, 72% kept silent and the rest sought help from family, hotlines, the local Women’s Federation or community committee, medical personnel or the police. Among 14 women who reported to the police, 8 women had cases opened. Among 30 women who told their families about being victims of sexual violence, nearly half of them (43.3%) were treated with ambivalence, 30% were not supported and 26.7% were supported.

3 Men’s childhood trauma and the rape of non-partners

3.1 childhood trauma.

Data for five kinds of childhood trauma were collected and are presented below. Hunger here refers to not enough food during childhood. Three behaviors are defined as neglect: living in different households (not with parents) at different times during childhood; parents did not look after the child due to alcohol or drug abuse; or the child spent nights outside the home and adults at home did not notice. Emotional violence includes the following behaviors of parents or teachers: scolding children for being lazy, stupid or weak; or humiliating children in public. Children who witness their mother being beaten by her husband or boyfriend are also victims of emotional violence. Physical violence refers to children being beaten by hard objects, being scarred by beatings, and being physically punished by teachers or principles. The following items are considered sexual violence against children: other people touching a child’s hips or genital areas, children being forced to touch themselves, children being frightened or threatened into having sex with others, or children having sex with men or women 5 years older than they are.

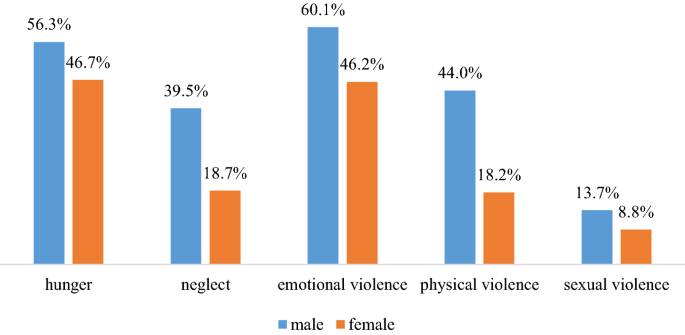

As Fig. 1 shows, many respondents experienced violence or adversity during childhood and male respondents were more likely than females to be involved (P < 0.0001). Besides the traumas listed in Fig. 1 , 24.7% of male respondents reported being bullied at school or in their communities during childhood, and 21.8% reported bullying others.

Source as Table 1

The prevalence of childhood trauma reported by male and female respondents.

3.2 Rape against non-partners

This study investigated men raping non-partner women. This included a man forcing or persuading a woman to have sex against her will, or a man having sex with a woman who was unable to give consent because of excessive alcohol or drug consumption. Gang rape, in which a woman was forced or persuaded to have sex against her will with more than one man, was also investigated. In order to present non-partner rape in context, data on partner rape are also listed in Table 3 . Although the majority of rapes are partner rapes, as indicated in Table 3 , women also face the risk of non-partner rape. One in five women reported being the victim of rape or attempted raped by non-partner men.

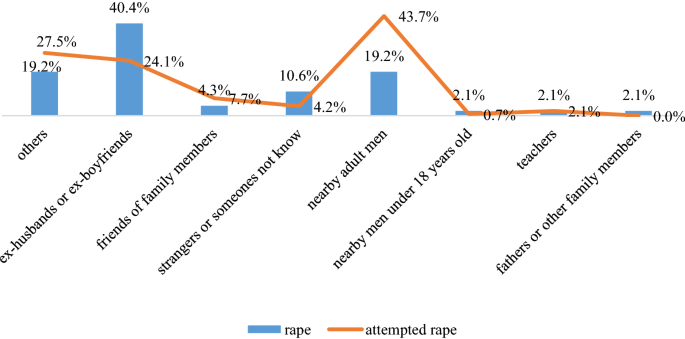

Regarding the motivation of rape, according to 222 male respondents who reported raping or attempting to rape non-partner women, the most common motivation was a feeling of male sexual entitlement. This included the man wanting to have the woman sexually, wanting to have sex, or wanting to show that he could have sex. Among these male respondents, 86.1% reported being driven by sexual entitlement. As well as sexual entitlement, 58% of the men reported being bored or seeking fun, 43% were angry or wanted to punish the woman, and 24% reported they had been drinking alcohol. Figure 2 indicates that some men’s sexual entitlement towards a women did not stop after the end of an intimate partner relationship. In fact ex-husbands and ex-boyfriends were the most likely perpetrators of non-partner rape. A look at the information reported by males who acknowledged having raped a woman, 91% of them committed rape for the first time between the ages of 15 and 29 years old, and 19.8% of the men raped more than one women.

Information on the perpetrators of 47 non-partner rapes and 145 attempted rape, as reported by women.

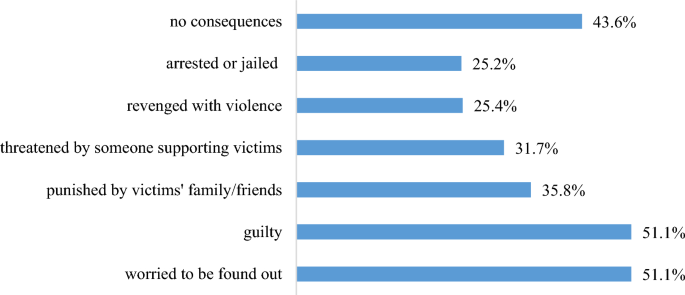

As shown in Fig. 3 , among 222 men who reported raping or attempting to rape non-partner women, nearly half of them reported suffering no consequences and only one quarter experienced legal repercussions. These findings correlate with the fact that about three quarters of women respondents kept silent after experiencing rape or attempted rape by non-partners.

The consequences of rape and attempted rape of non-partner women, as reported by male perpetrators.

4 Hegemonic masculinity and the risk factors of gender-based violence

4.1 hegemonic masculinity.

The views of the respondents on gender, femininities and masculinities were evaluated on several scales and Table 4 summarizes the specific elements of hegemonic masculinity. All except one of the items were supported by more than half of the male and female respondents.

There are two contradictions in Table 4 . First, while almost every male and female respondent agrees in the abstract principle that women and men should be treated equally, more than half of them also agree that men have more privileges than women when it comes to decision-making and sex life. The second contradiction is that, although more than 80% of male and female respondents agree men should share in the housework, more than half also consider looking after family members as women’s paramount duty. The gap between their attitudes and behaviors is greater for male respondents. While Table 4 shows that 92% of male respondents agree women should not be beaten in any situation, 44.7% of them reported inflicting physical IPV against women.

Why are there such striking contradictions? Table 4 reveals four key elements of hegemonic masculinity that provide at least part of the answer: (1) Men should decide important issues; (2) Men should be tough and use force if necessary; (3) A man should not beat a woman unless the woman challenges the man’s reputation; and 4) Men have to be heterosexual and it is in the nature of men to need sex more than women. By establishing these four elements above as a standard that defines “real men”, men’s domination over women is naturalized and legitimized. Such a definition of masculinity has negative ramifications for the notion of gender equality and can help to explain why there is such a large gap between male attitudes and behaviors. If hegemonic masculinity is the norm, gender equality does not mean that men and women should be treated the same, it means that men should treat women according to their “real” natures. In a world where men should decide important issues, be strong and use force if necessary, and need sex more than women, it becomes a simple matter for a man to justify forcing sex on an unwilling woman (i.e. raping a woman)—this is simply a manifestation of the natural order of things. While most people, men and women, agree that gender equality is a good thing in the abstract, widely accepted stereotypes of femininity, masculinity and gender differences lead instead to men dominating women and high levels of gender inequality.

Consistent with hegemonic masculinity which encourages men to be tough, use violence and not control sexual desire, male respondents reported a high likelihood of engaging in violent behavior and having unprotected sex. Nearly one in 5 men (18%) reported having participated in some form of violence including owning weapons, fighting with weapons, joining in gangs, being arrested and being in jail. Having unprotected sex was strikingly common. Among 856 men who reported having sexual experiences and answered the related questions, 82.7% of them reported never or seldom using condoms. Among 88 men who had had more than one sex partner during the last 12 month, 78.2% never or seldom used condoms.

IPV against women, one of the most common forms of violence engaged in by male respondents, also harms the male perpetrators. Compared with male respondents who never perpetrated IPV, Table 5 indicates that men who had perpetrated IPV were more likely to experience mental and reproductive health problems.

4.2 Risk factors for gender-based violence against women

Although poverty, low educational level, youth, and job pressures or unemployment are all commonly assumed to be risk factors associated with men perpetrating physical/sexual IPV against women, these are not confirmed by multiple logistic statistics. Table 6 presents the factors that increase the likelihood of a male perpetrating physical IPV against women. These are generational transmission of domestic violence and male domination, a man’s involvement in other types of violence, alcohol abuse, multiple sexual partners and quarrels between partners.

A comparison of Tables 6 and 7 shows that both the likelihood of men perpetrating physical and sexual IPV against women, and the likelihood of men raping partner and non-partner women were increased by three common risk factors: trauma during childhood, involvement in other types of violence, and having multiple sexual partners. Specifically, having experienced sexual violence during childhood and having low support for gender equality were found to be associated with men inflicting sexual violence.

5 Conclusion

Gender-based violence perpetrated by men is constructed within the social-ecological system, which is composed of four concentric circles. The innermost circle is the individual, and for this circle research identifies several risk factors including childhood trauma, involvement in other types of violence, alcohol abuse, multiple sexual partners and low support for gender equality. In the second circle consisting of relationships, male domination within the family, couples quarreling, generational transmission of ideas about unequal gender relationships and the commission of male violence against both females and children are found to be risk factors. The third circle consists of community, and risk factors in this circle are correlated to community responses to IPV and sexual assault against women, and people’s consciousness of and attitude towards the laws and regulations governing IPV and VAW. The outermost circle consists of social norms and the political and economic environments, and researchers find out that in China, social values, social policy, and laws and regulations are permeated with ideas of rigid hegemonic masculinity, and serve to perpetuate gender-based violence, especially IPV against women (Wang et al. 2013 ; Deng and Shi 2018 ).

Based on our findings, we have the following core recommendations: (1) The whole society including governments, mass media, communities and schools should recognize rigid hegemonic masculinity and work to eliminate this type of masculinity which perpetuates gender-based violence, especially IPV against women, encouraging instead non-violent masculinities based on gender equality. (2) The laws and regulations to stop IPV against women should be strengthened and stronger implementation and evaluation are needed to ensure that men are unable to commit violence against women with impunity. (3) Governmental agencies and NGOs should provide professional services for abused women, engage men in programs of violence prevention and strive to eliminate childhood trauma for boys and girls.

A female respondent received a different question asking if she had had sex she did not want with a male partner because she was afraid the man might become violent or hurt her if she refused.

Cossins, A., & Plummer, M. (2018). Masculinity and sexual abuse, explaining the transition from victim to offender. Men and Masculinities, 21 (2), 163–188.

Article Google Scholar

Dan, S.-H. (2018). New development of female jurisprudence studies: An overview of masters and doctoral theses on female jurisprudence from 2006 to 2015. Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 27 (3), 119–128.

Google Scholar

Deng, Y.-X., & Shi, F. (2018). Dormitory labor regime and male workers: A study on Foxconn factory. Journal of Hunan University, 32 (5), 128–135.

Duncanson, C. (2015). Hegemonic masculinity and the possibility of change in gender relations. Men and Masculinities, 18 (2), 231–248.

Gu, X.-B. (2014). Gendered suffering-middle-aged Miao women’s narratives on domestic violence in Southwest China. Journal of Zhejiang Gongshang University, 28 (4), 3–21.

Heilman, B., & Barker, G., (2018). Masculine norms and violence: Making the connections. https://promundoglobal.org/resources/page/10/?type=reports . Accessed February 12, 2019.

Schrock, D. P., & Padavic, I. (2007). Negotiating hegemonic masculinity in a batterer intervention program. Gender and Society, 21 (5), 625–649.

Song, Y.-P., & Zhang, J.-W. (2017). Less is better? The effects of imbalance in sex ratio in the marriage market on domestic violence against women in China. Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 26 (3), 5–15.

Tao, C.-F., & Jiang, Y.-P. (1993). An overview of Chinese women’s social status . Beijing: Chinese Women Publisher.

Wang, X. -Y., Jiao, D. -P., & Yang, L. -C. (2013). Masculinities and gender-based violence in transitional China. China Office of UNFPA.

Zheng, Z. Z., & Xie, Z. M. (2004). Migration and rural women’s development . Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The research is funded by China Office of United Nation Population Fund, technically supported by Partners for Prevention, an Asia–Pacific programme jointly established by United Nations Development Programme, United Nation Population Fund, UN women and UN Volunteers, and conducted by the Anti-Domestic Violence Network of China and the Beijing Forestry University.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, 300387, China

Xiangxian Wang

Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, 100083, China

China Women’s University, Beijing, 100101, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xiangxian Wang .

See Table 8 .

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wang, X., Fang, G. & Li, H. Gender-based violence and hegemonic masculinity in China: an analysis based on the quantitative research. China popul. dev. stud. 3 , 84–97 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-019-00030-9

Download citation

Received : 31 May 2019

Accepted : 26 July 2019

Published : 05 August 2019

Issue Date : October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-019-00030-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gender-based violence

- Intimate partner violence

- Hegemonic masculinity

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 27 March 2020

Homoprejudiced violence among Chinese men who have sex with men: a cross-sectional analysis in Guangzhou, China

- Dan Wu 1 , 2 ,

- Eileen Yang 2 , 3 ,

- Wenting Huang 2 , 4 ,

- Weiming Tang 2 , 5 , 6 ,

- Huifang Xu 7 ,

- Chuncheng Liu 8 ,

- Stefan Baral 9 ,

- Suzanne Day 3 &

- Joseph D. Tucker 1 , 2 , 5

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 400 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

4830 Accesses

3 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Homoprejudiced violence, defined as physical, verbal, psychological and cyber aggression against others because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation, is an important public health issue. Most homoprejudiced violence research has been conducted in high-income countries. This study examined homoprejudiced violence among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Guangzhou, China.

MSM in a large Chinese city, Guangzhou, completed an online survey. Data about experiencing and initiating homoprejudiced violence was collected. Multivariable logistic regression analyses, controlling for age, residence, occupation, heterosexual marriage, education and income, were carried out to explore associated factors.

A total of 777 responses were analyzed and most (64.9%) men were under the age of 30. Three-hundred-ninety-nine (51.4%) men experienced homoprejudiced violence and 205 (25.9%) men perpetrated homoprejudiced violence against others. Men who identified as heterosexual were less (AOR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.9) likely to experience homoprejudiced violence compared to men who identified as gay. Men who experienced homoprejudiced violence were more likely to initiate homoprejudiced violence (AOR = 2.44, 95% CI: 1.6–3.5). Men who disclosed their sexual orientation to other people were more likely to experience homoprejudiced violence (AOR = 1.8, 95% CI:1.3–2.5).

Conclusions

These findings suggest the importance of further research and the implementation of interventions focused on preventing and mitigating the effects of homoprejudiced violence among MSM in China.

Peer Review reports

Homoprejudiced violence is a major public health issue [ 1 ]. Homoprejudiced violence is defined as physical, verbal, psychological, and cyber aggression against an individual, group or community based on their actual or perceived sexual orientation [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Homoprejudiced violence can be directed at people who identify as sexual minorities or those who are perceived as being a sexual minority.

The United Nations (UN) has recognized homoprejudiced violence as an important public health problem [ 4 ]. Homoprejudiced violence can result in physical and psychological harm, decreased productivity, and increased risk of addictions (e.g., substance and alcohol use) [ 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. However, homoprejudiced violence is often under-reported because victims are afraid of disclosing their sexual orientation [ 10 ] and there are limited resources for survivors [ 9 , 11 ].

There is less research on homoprejudice in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [ 12 , 13 ], including China [ 4 ]. One Chinese study found that 40.7% of sexual minorities experienced name calling, 34.8% were verbally abused, 22.4% were isolated in school, and 6.0% received physical violence threats [ 6 ]. Furthermore, existing evidence is focused more broadly on sexual minorities as a whole [ 9 ]. Previous research on LGBT youth in the United States reported that gay men are at higher risk of ostracization and receiving homoprejudiced remarks compared to lesbian and bisexual subgroups [ 14 , 15 ]. However, little is known about the experiences of homoprejudiced violence among gay men or other men who have sex with men (MSM). Discrimination and homoprejudiced violence are known to influence sexual orientation disclosure [ 7 , 10 , 16 ] and uptake of HIV and other sexual health services [ 17 ]. A study in the United States reported that homoprejudiced violence victimization during youth was associated with more condomless sex and higher risk of HIV during adulthood [ 18 ].

Homoprejudiced violence initiated by gay men has not been well studied [ 9 ]. Many people who do not conform to gender and sexual norms are stigmatized, especially among men [ 14 ]. Masculinity is a primary component of socially desirable gender expression for men, and according to Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity, aggression is a feature of masculinity [ 19 , 20 ]. As a result, both heterosexual men and closeted gay men may act in an aggressive way towards gay people to demonstrate their masculinity and differentiate themselves from gay men. Some gay men are afraid of receiving homoprejudiced violence and in order to hide their sexual orientation, show aggressive behaviors against LGBT groups to reinforce their masculinity [ 6 , 9 ]. Understanding homoprejudiced violence may help to improve resources and develop interventions. The purpose of this study was to examine the frequency and correlates of homoprejudiced violence among MSM in Guangzhou, China.

Material and methods

Online survey.

In partnership with a local community-based organization (CBO) and the Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), we conducted a cross-sectional online questionnaire survey with 777 MSM in Guangzhou, China in September 2018. The survey was distributed online to MSM through CBO and CDC social media accounts. Eligibility criteria included the following: being biologically male at birth; being 16 years old or above; reported ever having oral or anal sex with men; residing in Guangzhou in the past six months. All survey data were anonymous and confidential, and online consent was obtained prior to the survey. Each man who participated received either 7.5 USD (50 Chinese Yuan) or a free HIV self-test kit as an incentive to participate.

Survey instruments

We collected information about participants’ sociodemographic characteristics including age, residence permit, occupation, heterosexual marital status (never married, engaged or married, and divorced/separated/widowed), annual income, highest education obtained (high school or less, some college, university, and postgraduate), gender identity (male, female, transgender, and unsure), sexual orientation (gay, bisexual, heterosexual, and unsure) and sexual orientation disclosure to people other than their partner(s) (yes/no).

Homoprejudiced violence questionnaire

Twelve homoprejudiced violence survey items were designed based on previous literature [ 5 , 21 , 22 ]. We selected 12 items to cover four domains – physical assault, verbal aggression, psychological abuse, and cyber violence (Supplementary file 1 ). We translated and adapted the 12 items in order for them to be relevant to Chinese men. These 12 items asked whether a participant had ever experienced any of the following due to their sexual orientation: being gossiped about, being name called, being deliberately alienated or isolated, being threatened, being maliciously called gay, being spat on, having personal belongings damaged, being deprived of economic resources or personal belongings by someone (including family members), having personal freedom restricted by someone (including family members), being physically harmed (such as being slapped, beaten or kicked), being harmed on social media (such as WeChat and Weibo, the Chinese substitutes of WhatsApp and Twitter), and being harmed through phone calls or messages. The items were field tested with 10 participants and minor amendments were made for better clarity.

All 12 items used three responses: “yes”, “no” and “do not want to tell”. A new summative variable was generated by adding up the responses (“yes” were coded as 1, “no” or “do not want to tell” were coded as 0) of the 12 items to assess the overall prevalence. The summed value 0 was recoded as 0 (no prior experiences of homoprejudiced violence), and the summed values 1 to 12 were recoded as 1 (prior experiences of homoprejudiced violence of any type) (outcome 1). Additionally, one follow-up item asked whether participants had ever committed any of the 12 violent behaviors aforementioned against others due to their sexual orientation (yes, no, do not want to tell) (outcome 2). The Cronbach alpha value of the 12-item homoprejudiced violence questionnaire was 0.89.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to describe sample characteristics, including sociodemographic backgrounds and frequencies of violence experiences. The two outcomes were dichotomized (with “no” and “do not want to tell” grouped together) in regression analyses. We conducted univariate and multivariable binary logistic regressions to examine sociodemographic factors associated with homoprejudiced violence. We reported odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 25.

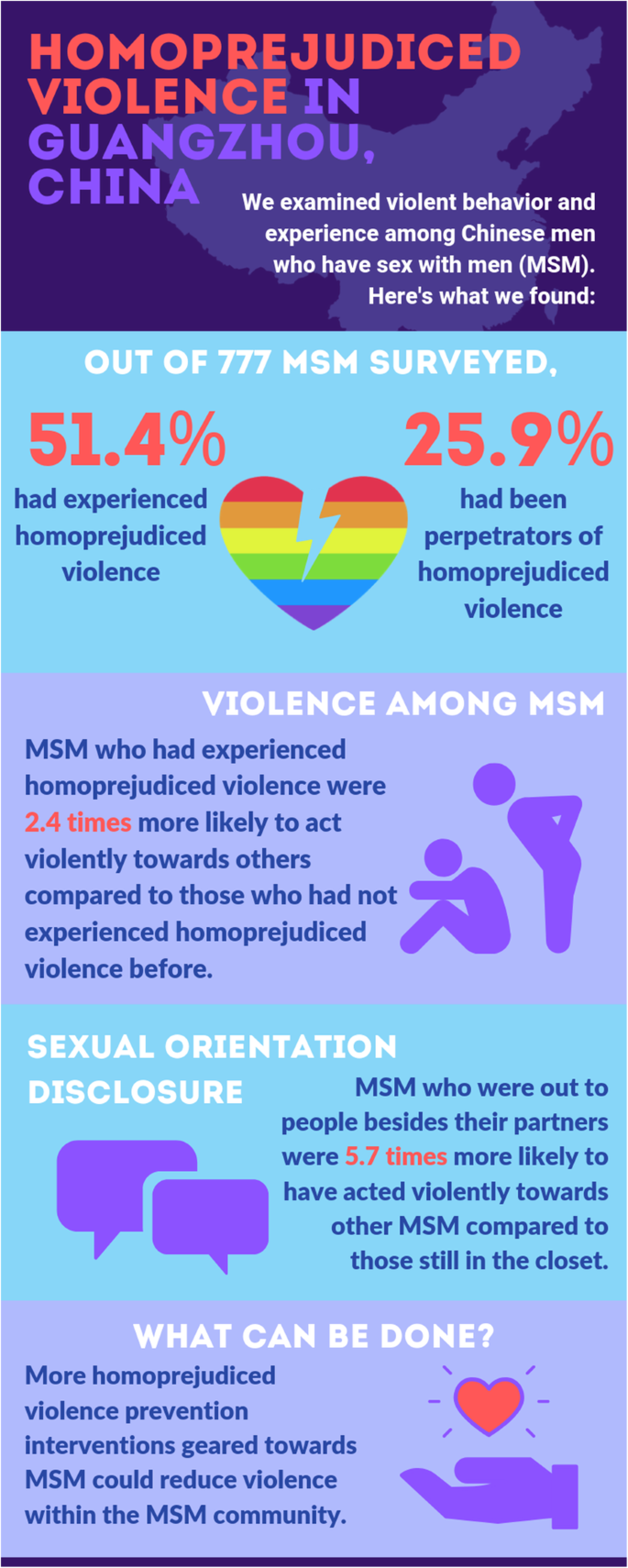

We invited 2691 MSM to participate in the survey and 917 completed the questionnaire (response rate = 34%). Overall, 140 of these 917 MSM did not meet inclusion criteria and were excluded from the analysis. Data from 777 men were included in the analysis. Table 1 shows sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Over half of survey respondents were under the age of 30 (495, 64.9%) and self-identified as gay (447, 57.5%). Most men lived in urban areas (639, 82.2%). A large proportion of men were not students (718, 92.4%), and about half had obtained university-level education or above (440, 56.7%). Around 40% (313) of men earned an annual income between US$8682–13,024, and nearly three-quarters had never been engaged or married to a woman (574, 73.9%). Most men had disclosed their sexual orientation to people other than their partners (571, 73.5%). A total of 399 (51.4%) men reported experiences of homoprejudiced violence, while 205 (25.9%) men initiated homoprejudiced violence (Fig. 1 ). Frequencies of each violence item are reported in Table 2 . One hundred and six men (13.4%) experienced physical violence. One hundred and eighty-three men (23.1%) experienced name calling. Two hundred men (25.2%) experienced social isolation. One hundred and thirteen men (14.2%) experienced deprivation of economic resources or personal belongings and 128 (16.1%) reported cyber violence on social media.

Infographic of homoprejudiced violence in Guangzhou, China. Source of data: The authors created this infographic based on the study findings by using a free graphic design website Canva ( https://www.canva.com/ )

After controlling for demographic variables including age, residence status, occupation, marital status, education level, and annual income, multivariable logistic regression analyses showed that men who identified as heterosexual were less (AOR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.9) likely to experience homoprejudiced violence compared to men who identified as gay.Men who were unsure about their sexual orientation were more likely (AOR = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.2–5.5) to have experienced homoprejudiced violence compared to gay men (Table 3 ). Men who disclosed their sexual orientation were,more likely (AOR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.3–2.5) to experience homoprejudiced violence compared to other men (Table 3 ).

Men younger than 30 years old were more likely to have initiated homoprejudiced violence against others compared to older men (AOR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.5–3.8) (Table 3 ). Urban men were also more likely to have initiated homoprejudiced violence compared to rural men (AOR = 2.9, 95% CI: 1.6–5.2). Men who were engaged or married to women were more likely (AOR = 5.7, 95% CI: 3.6–9.1) to have initiated homoprejudiced violence than those who had never been married. Men who were separated, divorced, or widowed were more likely (AOR = 9.2, 95% CI: 4.8–17.6) to have initiated homoprejudiced violence compared to other men. People who identified as women or transgender/unsure were found to be 3.0 times (AOR = 3.0, 95% CI: 1.5–6.2) and 2.2 times (AOR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.2–4.2) more likely to have been a perpetrator, respectively. Respondents who ever experienced homoprejudiced violence before were 2.4 times (AOR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.6–3.5) more likely to have initiated homoprejudiced violence against others.

Homoprejudiced violence among sexual minorities is an important public health issue in many LMICs. Our study contributes to the literature by examining homoprejudiced violence among MSM in China, including MSM-initiated homoprejudiced violence .

We found that approximately half of men had ever experienced some form of homoprejudiced violence. This is lower than the prevalence of homoprejudiced violence observed in the UK [ 9 ] and US [ 11 , 23 ]. Less homoprejudiced violence in Guangzhou may be related to lower levels of disclosing sexual orientation [ 24 ]. This finding is consistent with studies showing that more visible LGBT people may suffer from higher levels of violence [ 25 , 26 ]. Interventions to reduce discrimination against sexual minorities are needed in China.

Many MSM in our sample who experienced homoprejudiced violence then went on to initiate homoprejudiced violence against other MSM. This finding is consistent with a study from the United States [ 27 ]. MSM may use violence as an approach to conceal their sexual orientation if they have been a victim of homoprejudiced violence [ 9 ]. Other potential factors may include poor sexual education and fear of social stigma. Poor awareness of homoprejudiced violence might also play a role. Understanding the context of homoprejudiced violence is key to successfully creating an environment where all MSM feel safe.

The data presented here have implications for research and policy. There are few epidemiological studies focusing on homoprejudiced violence among MSM in LMICs. Our study provides evidence on the prevalence and correlates of homoprejudiced violence. In terms of designing interventions, some subsets of MSM may be at greater risk for homoprejudiced violence. Our study suggests that younger, urban, and openly gay men are more likely to initiate homoprejudiced violence against others. Given young gay men are more often engaged in community-based sexual health programs, there may be missed opportunities for engaging community-based organizations to develop anti-violence interventions.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, we conducted the survey with MSM who subscribed to the social media account of a community-based organization that provided sexual health services in a developed city in China. Our participants had higher education and income than the average Guangzhou resident. Our study results should not be extrapolated to the wider community of MSM in China. Second, we combined participants’ responses of “no” and “don’t want to tell” to homoprejudiced violence as one category. This may result in a conservative or underestimate of the actual prevalence of homoprejudiced violence experiences due to unwillingness to share. Third, the study focused on homoprejudiced violence, but not broader experiences of homoprejudice. It is likely that non-violent experiences of homoprejudice among MSM are even more prevalent (e.g. social exclusion). Fourth, we recruited MSM who ever had anal or oral sex with a man in the study but did not include those who were gay men but had never engaged in sex with a man, limiting our understanding of the experiences of homoprejudiced violence to a subset of sexually active MSM. Lastly, an online cross-sectional questionnaire survey has limited depth to fully understand men’s thoughts about their own experiences. Qualitative research is warranted to better understand the issue.

Homoprejudiced violence is an important public health problem. We found high a prevalence of homoprejudiced violence victimization and perpetration among Chinese MSM. Interventions are necessary to prevent homoprejudiced violence among Chinese MSM and create an environment where MSM feel safe.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Men who have sex with men

Low- and middle-income countries

Srabstein JC, Leventhal BL. Prevention of bullying-related morbidity and mortality: a call for public health policies. SciELO Public Health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2010;88:403. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.10.077123 .

Rutherford A, Zwi AB, Grove NJ, Butchart A. Violence: a glossary. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(8):676–80.

Article Google Scholar

The Rainbow Project. Bullying Belfast: The Rainbow Project; 2019 [cited 2019 4 June]. Available from: https://www.rainbow-project.org/bullying .

UNESCO. Review of homophobic bullying in educational institutions Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2012 [cited 2019 2 June]. Available from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000215708 .

Amankavičiūtė S. Sexual orientation and gender identity based bullying in Lithuanian schools: Survey data analysis2014; ILGA-Europe. Available from: https://www.ilga-europe.org/sites/default/files/Attachments/lt_-_report_en_-_house_of_diversity.pdf .

C-z W, W-l L. The association between school bullying and mental health of sexual minority students. Chinese J Clin Psychol. 2015;23(4):701–5.

Google Scholar

Formby E. The impact of homophobic and transphobic bullying on education and employment: a European survey 2013. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University; 2013.

Lea T, de Wit J, Reynolds R. Minority stress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults in Australia: associations with psychological distress, suicidality, and substance use. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(8):1571–8.

Highland Council Psychological Services. A Whole-School study of the extent and impact of homophobic bullying Highland2014 [cited 2019 4 June]. Available from: https://www.highland.gov.uk/download/downloads/id/12122/homophobic_bullying_report_november_2014.pdf .

Takács J. Social exclusion of young lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in Europe: ILGA Europe Brussels. Belgium; 2006.

Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Zongrone AD, Clark CM, Truong NL. The 2017 National School Climate Survey: the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our Nation's schools: ERIC; 2018.

Ireland PR. A macro-level analysis of the scope, causes, and consequences of homophobia in Africa. Afr Stud Rev. 2013;56(2):47–66.

Spijkerboer T. Fleeing homophobia: sexual orientation, gender identity and asylum: Routledge; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Katz-Wise SL, Rosario M, Tsappis M. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth and family acceptance. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2016;63(6):1011–25.

Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Diaz EM. Who, what, where, when, and why: demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(7):976–88.

Hollis LP, McCalla SA. Bullied back in the closet: disengagement of LGBT employees facing workplace bullying. J Psychol Issues Organ Cult. 2013;4(2):6–16.

Johnson CA. Off the map. How HIV/AIDS programming is failing same-sex practicing people in Africa New York: International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission; 2007 [cited 2019 21 August 2019]. Available from: https://outrightinternational.org/sites/default/files/6-1.pdf .

Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Cheong J, Wright ER. Gay-related development, early abuse and adult health outcomes among gay males. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(6):891–902.

Connell RW. Gender and power: society, the person and sexual politics: John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

Connell RW. Masculinities: polity; 2005.

Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Cyberbullying research summary: Bullying, cyberbullying, and sexual orientation. Cyberbullying Research Center: http://cyberbullying org/cyberbullying_sexual_ orientation_fact_sheet pdf. 2011.

Evans CB, Chapman MV. Bullied youth: the impact of bullying through lesbian, gay, and bisexual name calling. Am J Orthop. 2014;84(6):644.

Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Jones KC, Outlaw AY, Fields SD. Smith fTYoCSISG, Justin C. racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(S1):S39–45.

Liu JX, Choi K. Experiences of social discrimination among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. AIDS Behavior. 2006;10(1):25–33.

Stahnke T, LeGendre P, Grekov I, Petti V, McClintock M, Aronowitz A. Violence Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Bias; 2008.

Human Rights Watch. “We Need a law for Liberation": Gender, Sexuality and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey 2008 [cited 2019 20 June]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/turkey0508/ .

Ma X. Bullying and being bullied: to what extent are bullies also victims? Am Educ Res J. 2016;38(2):351–70.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This work received funding support from Academy of Medical Sciences and the Newton Fund (Grant number NIF\R1\181020), National Institutes of Health (NIAID 1R01AI114310–01), UNC-South China STD Research Training Center (FIC 1D43TW009532–01), UNC Center for AIDS Research (NIAID 5P30AI050410), the North Carolina Translational & Clinical Sciences Institute (1UL1TR001111), and SMU Research Initiation Project (QD2017N030, C1034448). The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

International Diagnostics Centre, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, Bloomsbury, London, WC1E 7HT, UK

Dan Wu & Joseph D. Tucker

Social Entrepreneurship to Spur Health (SESH) Global, Guangzhou, China

Dan Wu, Eileen Yang, Wenting Huang, Weiming Tang & Joseph D. Tucker

Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

Eileen Yang & Suzanne Day

Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Wenting Huang

University North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Project-China, Guangzhou, China

Weiming Tang & Joseph D. Tucker

Dermatology Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Weiming Tang

Guangzhou Center of Diseases Control, Guangzhou, China

Department of Sociology, University of California San Diego, San Diego, USA

Chuncheng Liu

Department of Epidemiology, The Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

Stefan Baral

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.W. conceived the idea and designed the study. W.H., W.T., and H.X. coordinated and collected data. W.H. cleaned the data. D.W. and E.Y. analyzed the data. D.W., E.Y., and J.D. wrote the paper. W.H., W.T., C.L., S.B., S.D., and H.X. provided constructive comments and edited the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dan Wu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from Guangzhou Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. Online informed consent was obtained prior to the commencement of the survey questionnaire. The form of consent was approved by the ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

Homoprejudiced violence questionnaire.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wu, D., Yang, E., Huang, W. et al. Homoprejudiced violence among Chinese men who have sex with men: a cross-sectional analysis in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health 20 , 400 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08540-9

Download citation

Received : 08 December 2019

Accepted : 17 March 2020

Published : 27 March 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08540-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Epidemiology

- Homoprejudice

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Probing Causes of Violence Against Women in China

- 24 June 2011

HUNAN PROVINCE, China — A lively workshop session on gender equality started with brainstorming of commonly used Chinese idioms describing a good man.

He should have a back like a tiger and a waist like a bear.

He does not shed tears until his heart is broken.

He stands firm amid adversities.

On the subject of a good woman, more hands shot up.

She should behave in a sweet and helpless way.

She should be caring and affectionate.

She should be a good wife and loving mother.

Of the more than 40 men and women who attended the interviewers' training last spring, half were university students from all over China, and half of them were recruited locally from various professions. Most of them are in their 20s, joined by a few older retirees. The training -- which included an innovative use of new technology qualified them to undertake innovative field data collection on men, gender equality and violence against women.

The fieldwork is part of the research on masculinities – the qualities generally ascribed to men – and their connections to violence against women.

Generating new perspectives on masculinities

Equipped with knowledge of complicated issues surrounding violence and gender norms, the interviewers will seek views from both men and women in this Hunan Province city. China is one of seven countries included in a research project on gender-based violence in the Asia Pacific region. Led by Partners for Prevention, a regional programme supported by UNDP, UNFPA, UN Women and UN Volunteers, the research will generate new analysis on masculinities and violence in the region and is expected to improve measures to prevent and respond to violence against women.

“The research is the most strict one in terms of the ethics standard, and the most comprehensive one with lots of hard-to-ask questions,” said Professor Wang Xiangxian, one of the key Chinese researchers dedicated to this project. For both men and women, the questionnaire includes probing some of the most private aspects of their lives, including sexual relations, violence, intimate relationships and drug use. The greatest challenge the research team faces is how to ask these questions in the most appropriate way and to get honest answers without betraying the privacy of the interviewees.

Using technology to make hard-to-ask questions easier

The trendy Apple portable iTouch provides an innovative solution. All the questions are programmed in a special application that can be installed in an ITouch that will serve as a personal digital assistant for the interviewer. Instead of holding printed questionnaires in hand and going through each question face-to-face with the interviewee, the interviewer will guide the subject to answer the questions directly on the iTouch. The questions are even recorded so that those who can’t read will hear the questions with headsets and key in their answers. The use of the PDAs aims to avoid embarrassment, to allow self-reporting of violent acts such as physical abuse and rape, and to ensure maximum protection of privacy.

The field work will last for over a month in the UNFPA-supported pilot site. Already the project has made some important breakthroughs, ranging from village level awareness-raising to the issuing of city-level legislation on violence against women. The findings from the research will bring valuable insights to all stakeholders involved to formulate effective actions to prevent and respond to violence against women by taking into account of both men and women. The results will also be shared with Chinese experts involved in the process of drafting the Anti-Domestic Violence Law of China

--- Gao Cuiling, UNFPA China

Seeking Help for 'Private Matters' in China

LIU YANG CITY, China —" I feel happy with my life now. I believe it is going to be better," says 32-year-old Xiao Hui, who no longer fears the shadow of domestic violence.

Xiao Hui and her husband were schoolmates. After leaving high school, they both went to work in Guangdong Province as migrant workers for a few years, and they fell in love. They returned to Duzheng Village to get married.

With the arrival of their daughter seven years ago, Xiao Hui stayed at home while her husband worked with construction companies nearby. With one more person to feed, the couple began to quarrel about money. One day, her husband returned Xiao Hui’s complaints by forcefully shoving her to the bedside. "He treated me with no respect. He hurt me as much as if he had beaten me," said Xiao Hui.>

Xiao Hui did not just worry and cry after the incident. She remembered seeing the anti-domestic violence posters and performances near the village and she mustered up the courage to ask Ms. Zu of the Women’s Committee whether her ‘private matter’ would qualify for some sort of formal intervention. To her surprise, Ms. Zu organized a mediation session with the couple and their parents. "My husband was told if he did not stop, he would have to face the consequences," Xiao Hui recalled.

Xiao Hui thought the mediation really worked. "My husband would have started beating me if he did not get the formal warning," Xiao Hui believes.

Duzheng Village is one of the seven local villages in Liuyang that have organized intensive community activities to encourage villagers to speak out and seek support whether violence occurs in or out of their houses. It is part of a UNFPA-supported pilot initiative aiming at setting up a multi-sectoral model on violence against women. "Our volunteers spread messages on violence when entertaining big crowds of people, even at weddings and funerals," said Ms. Zu. Every household got a letter on domestic violence and there were displays in the village on where to get support when violence happens.

According to the Violence against Women: Facts and Figure 2010 compiled by UNFPA China and a Chinese NGO Andi-Domestic Violence Network, "one of the greatest challenges to addressing this is that women usually seek help from informal networks such as family, and neighbours, or never tell anyone of the violence". In China, where the culture of "washing your dirty linen at home" is extremely strong, the village campaign on violence makes it possible for many women like Xiao Hui to speak up and seek help for what is usually seen as ‘private matters.’

Related Content

Investing in equality: How young women are innovating to improve their health,…

Press Release

UNFPA receives EDGE Move and EDGEplus certifications, reconfirming its…

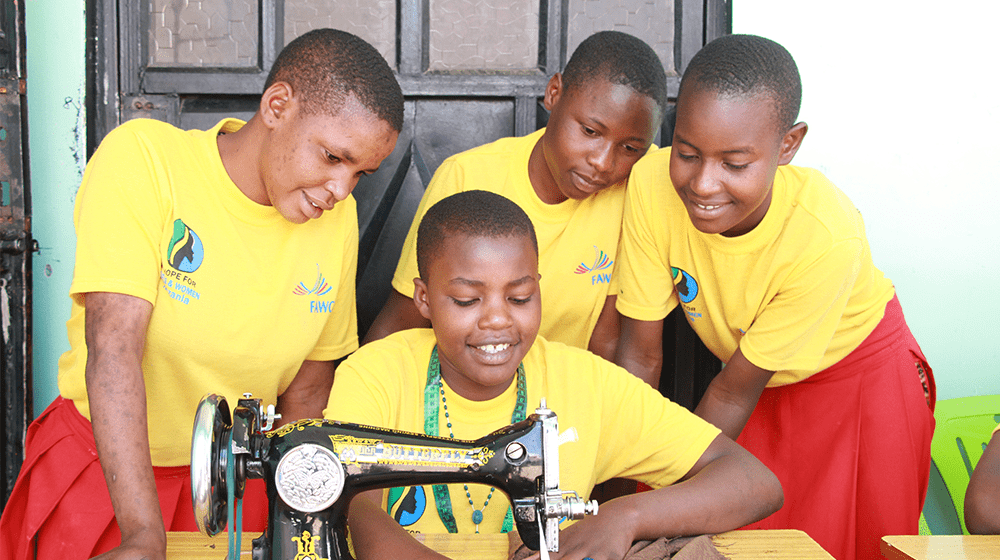

Champion of change: How a Tanzanian youth activist is rallying for gender…

We use cookies and other identifiers to help improve your online experience. By using our website you agree to this, see our cookie policy

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 10, Issue 9

- PositivMasc: masculinities and violence against women among young people. Identifying discourses and developing strategies for change, a mixed-method study protocol

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6935-9781 M Salazar 1 ,

- N Daoud 2 ,

- Claire Edwards 3 , 4 ,

- Margaret Scanlon 4 ,

- C Vives-Cases 5 , 6

- 1 Department of Global Public Health, GloSH research group , Karolinska Institutet , Stockholm , Sweden

- 2 Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences , Ben-Gurion University of the Negev , Beer-Sheva , Israel

- 3 School of Applied Social Studies , University College Cork , Cork , Ireland

- 4 Institute for Social Science in the 21st Century (ISS21) , University College Cork , Cork , Ireland

- 5 Department of Community Nursing, Preventive Medicine and Public Health and History of Science , University of Alicante , Alicante , Spain

- 6 CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health , Madrid , Spain

- Correspondence to Dr M Salazar; mariano.salazar{at}ki.se

Introduction Despite public policies and legislative changes aiming to curtail men’s violence against women (VAW) around the world, women continue to be exposed to VAW throughout their life. One in three women in Europe has reported physical or sexual abuse. Men who display unequitable masculinities are more likely to be perpetrators. VAW is increasingly appearing at younger ages. The aims of the project are fourfold: (1) to explore and position the discourses that young people (men and women, 18–24 years) in Sweden, Spain, Ireland and Israel use in their understanding of masculinities, (2) to explore how these discourses influence young people’s attitudes, behaviours and responses to VAW, (3) to explore individual and societal factors supporting and promoting anti-VAW masculinities discourses and (4) to develop actions and guidelines to support and promote anti-VAW masculinities in these settings.

Methods and analysis A participatory explorative mixed-method study will be used. In Phase 1, qualitative methods will be used to identify the discourses that young people and stakeholders use to conceptualise masculinities, VAW and the actions that are needed to support and promote antiviolence masculinities. In Phase 2, concept mapping will be used to quantify the coherence, relative importance and perceived relationship between the different actions to support and promote anti-VAW masculinities. Phase 3 is a knowledge creation and translation phase, based on findings from Phases 1 and 2, where actions and guidelines to promote and support anti-VAW masculinities will be developed.

Ethics and dissemination Ethical clearance has been obtained from ethics review boards in each country. Results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications, presentations at international conferences, policy briefs, social media and through the project online hub. With its multicountry approach, our project results seek to inform policies and interventions aimed at promoting discourses which challenge hegemonic masculinities.

- public health

- qualitative research

- statistics & research methods

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038797

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our mixed-method exploratory (MM) design allow us to combine the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative research to obtain a holistic picture of antiviolence masculinities in four countries.

The participatory design of this project engages young people and community stakeholders.

The methodology is based around a series of interconnected phases, each building on the previous one; qualitative data are used as a basic for the quantitative concept mapping study.

The exploratory longitudinal MM design is time consuming and expensive compared with cross-sectional studies.

The statistical generalisation of the quantitative findings is limited.

Introduction

The United Nations defines violence against women (VAW) as ‘any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life’. 1 Despite public policies and legislative changes aiming to curtail men’s VAW around the world, women continue to be exposed to violence throughout their life course.

According to the 2015 European Union survey on VAW, 2 one in three women in Europe has reported physical or sexual abuse from the age of 15 years. 2 Rates vary between countries; the lifetime prevalence of physical/sexual violence ranges from 46% in Sweden to 22% and 26% in Spain and Ireland, respectively. Meanwhile, in Israel, a recent nationwide study that included a stratified sample of perinatal women found that close to 40% of women attending maternal and child health services had been exposed to different forms of intimate partner violence (IPV) at some point in their lives, with the prevalence of IPV higher among Arab women (67%) than among Jewish women (27%). 3

Masculinities and VAW: what do we know?

Connell 4 proposes that there are different types of masculinities, which are related to each other in diverse ways (relations of hegemony, subordination, complicity and marginalisation). Among those, hegemonic masculinities are the constellations of actions that protect and reinforce the dominant position of men in a society. 4 They represent the ideals of what it is to be a man in a given society. While they vary across settings, they often depict men as heterosexual, strong, as household heads, economic providers, entitled to sex and above all and dominant over women. 4

Population-based studies in South Africa 5 and multicountry studies in Latin America 6 and Asia 7 have consistently found that men who display hegemonic masculinities are more likely to perpetrate different forms of VAW. A multicountry study in Asia found that men who reported adherence to traditional forms of masculinities (ie, low equality) were two times more likely to have committed sexual or physical abuse towards women (AIRR 2·22,95% CI 1.28 to 3.84). 7

However, masculinities can manifest themselves in many ways, and not always harmfully. In our previous qualitative studies in Latin America, for example, we found that young men enact different masculinities that express diverse discursive positions on gender equity and VAW. 8–10 The discursive positions range from a challenging discourse that problematises gender inequality, men’s lack of responsibility for VAW and sexual abuse and women’s subordination to discourses that reject men’s responsibility and curtail women’s agency. Most promisingly, we have identified what we might refer to as anti-VAW masculinities existing among young men. These young men are more likely to reject risk behaviours traditionally associated with masculinity, to defend women’s rights, to reject men’s VAW and to actively be involved in actions preventing or curtailing VAW. 8–10 These ideas have consequences for our understandings of masculinities in relation to VAW. These are ideas that we intend to explore further in this study, in European and Israeli contexts.

Gender, power, masculinity and its relationship to VAW

VAW does not occur in isolation as it is strongly influenced by gender and the way masculinities are enacted. Gender can be defined as the evolving, socially constructed and time-bound set of power, economic, emotional and symbolic relations by which men and women interact with each other. 11 The concept of power is central in the study of VAW and gender. While there are many definitions, 12 in this protocol power is defined as the ability to dominate others. 12

Gender relations are often unequal, and the gender order is often viewed as a norm system in which men have a dominant position over women. This power is largely exercised by controlling (often through violence) women’s lives and bodies. 11 Therefore, it is clear that understanding masculinities is crucial if VAW is to be reduced.

Masculinities are constructed, reconstructed and sustained in multiple arenas in a society. For young people, these arenas include the educational system. 13 From a symbolic perspective, the dichotomisation and conceptualisation of gender in terms of binary categories is reinforced by having separate restrooms, dividing boys and girls in sports activities, creating competition between genders and so on. Male pupils often establish hierarchies based on aggression, dominance, competition and sexuality that are reflections of the traditional gender order (ie, nerds vs the athletes, gay vs straights, etc). 13 These traditional gender hierarchies between young men (and young women) are often tolerated if not supported.

However, gender relations are not static as they are constantly evolving. They are frequently challenged by men and women rejecting the gender order and its relationships of subordination and marginalisation. 4 Howson 14 has proposed that protest masculinities and femininities exist, and are represented by men and women who challenge traditional gender relations. In Europe, Elliot has described a form of protest masculinity called caring masculinity. 15 Caring masculinities reject men’s domination over women and embrace positive values such as caring for others, interdependence and emotional expression.

Protest masculinities can also arise from men’s involvement with groups challenging men’s VAW. 16 Developing anti-VAW masculinities is a process that takes time. 8–10 It involves not only being non-violent oneself, but being agents of change by questioning and deterring VAW whenever it is enacted in a society. 16 The outcomes of this process are influenced by the intensity of men’s participation in these groups, the ideologies underpinning the group’s work and societal factors supporting or hindering change. 15

Flood 16 has highlighted that developing anti-VAW masculinities does not imply that men will also question the other privileges that patriarchy bestows to men (ie, greater decision-making power and authority, lack of involvement in household duties, etc). One example of this is benevolent sexism. 17 Benevolent sexism is a paternalistic approach that views women as weak, vulnerable and without agency. This approach fosters men’s protective stance over women; however, it also rationalises women’s subordinated position in a society. 17

It is widely recognised that traditional hegemonic forms of masculinities must be challenged and addressed if any reduction on VAW is to be achieved. 18 The European Commission Advisory Committee on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men has also highlighted the relevance of identifying and supporting new forms of masculinities in tackling gender inequality. 19

In Europe, a significant amount of research has been conducted on hegemonic masculinity and its connection with violence towards other men, 20–22 IPV/honour-related violence, 23 fatherhood, ill health and increased young men’s risky sexual behaviours 23 among others. These studies have provided important insights into the relationship between hegemonic masculinities, ill health and different types of violence. However, none have specifically focused on young people, on interrogating the existence of masculinities that specifically challenge VAW, and how these anti-VAW masculinities can be supported.

Our research focuses on young people since different forms of VAW, including IPV, are increasingly appearing at earlier ages. According to WHO data 24 young men who are violent towards women have a higher risk of continuing being violent with their future partners. In addition, toxic partner relations can begin and endure if VAW is normalised at this age. Thus, VAW prevention should start early in life if sustained progress on preventing VAW is to be achieved. We believe that identifying young people’s discursive positions on VAW, as well as the factors supporting and promoting anti-VAW masculinity discourses, are key steps in designing and implementing gender-sensitive, evidence-based policies aimed at reducing VAW. Through its methodology, participatory process and dissemination strategies, this research will seek to contribute to public and policy debate and actions around anti-VAW masculine identities in addressing VAW.

The aim of this project is to explore the discourses that young people in Sweden, Spain, Ireland and Israel use in their understanding of masculinities and to explore how these discourses influence young people’s attitudes, behaviours and responses to VAW. Furthermore, we will explore individual and societal factors supporting and promoting anti-VAW masculinity discourses within and across these countries and develop actions and guidelines to support and promote anti-VAW masculinities in these settings.

Methods and analysis

Overall project design.

This research will be conducted in Sweden, Spain, Israel and Ireland. These countries were selected because the collaborating institutions are located there. We will conduct a participatory, mixed-method (MM) study using an exploratory sequential design. 25 In the first phase, data will be gathered using semistructured interviews and focus groups discussions (FGDs) in order to identify the discourses that young people and stakeholders use to conceptualise masculinities and VAW, as well as actions needed to support and promote anti-VAW masculinities. In Phase 2, we will use concept mapping (CM) to quantify the coherence, relative importance and perceived relationship between the different actions to support and promote anti-VAW masculinities identified in Phase 1. Phase 3 is knowledge creation and translation phase where we will disseminate our findings and design guidelines, in conjunction with stakeholders and young people, to promote and support anti-VAW masculinities.

The project started on January 1st, 2019. Phase 1: The first 6 months of the project were focused on developing the project logistics and data collection instrument. Data collection for Phase 1 started on August 1st, 2019 and ended on February 29th, 2020. Phase 2: Planning for logistics and developing the data collection instrument started on March 1st, 2020 and ended on August 30th, 2020. Data collection for Phase 2 will be conducted from September 1st, 2020 to January 30th, 2021. Data analysis from both phases will be conducted from February 1st 2021 to August 30, 2021. Phase 3 started on September 1st, 2020 and will end on March 30th, 2022.

Qualitative study with young men and women

(1) To explore and position the discourses that young people use in their understanding of masculinities, (2) to explore how these discourses influence young people’s attitudes, behaviours and responses to VAW and (3) to explore individual and societal factors supporting and promoting anti-VAW masculinity discourses in the study settings.

Participant selection

Participants will be young people aged 18–24 years. Purposeful sampling 26 of young people will be undertaken based on the primary criteria of age, gender and whether or not the young person is involved in activism or an organisation working to prevent VAW. Within the sample in each country, we will seek to obtain an equal representation of men and women, of different ages within the 18–24 age bracket, and also seek to capture representation based on diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and educational levels. Due to ethical reasons, we will not ask our participants for their sexual orientation or gender identity. However, young people are welcomed to participate regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

The sampling strategy described above will allow us to compare the similarities and differences between different groups of young people based on age, gender and whether they are engaged or not in anti-VAW activism. Participants will be recruited through advertisements and flyers posted in educational institutions (high schools, universities, etc.), social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and state institutions working with young people.

Data collection

In-depth interviews and FGDs will be used to gather the data. In-depth interviews will allow us to explore individual experiences and FGDs will allow us to identify community norms and values related to our research questions. A semistructured discussion guide with open-ended questions will be used to collect the data. This will be developed based on a literature review, our previous experience in the field and discussions with the country-level advisory groups of both stakeholders and young people established for the project.

The topics to be explored in the interviews and FGDs include perceptions about masculinities, femininities, different forms of VAW (emotional, physical, sexual, controlling behaviour and online violence) and suggestions about how to promote and support anti-VAW masculinities. Short vignettes describing everyday situations where VAW is enacted will be used to encourage discussion.

Data will be collected until saturation of the information is reached. Around 15–20 in-depth interviews will be conducted per country. Four FGDs, two with young people from the general population and two with young people affiliated with organisations working to prevent VAW, will be also conducted per country. FGDs will be stratified by gender. Non-binary and gender queer people will be welcomed to be part of the FGD they feel more comfortable with. Data will be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Situational analysis 27 will be used to analyse the data. We have chosen this method because it allows us to identify how discourses on masculinity and VAW differ and overlap within and across settings. Discourses can be defined as ‘a broadly discernible cluster of terms, descriptions and figures of speech often assembled around metaphors or vivid images’. 28 They are important because they reflect how people understand different topics and act on them.

Situational analysis starts by inductively coding the text and constantly comparing the data to group the codes into categories of meaning. The constant comparison will allow us to identify how the categories merge into discourses and what axes of variation (ie, responsibility for VAW) are present in the data. The data will be represented using a positional map articulating the different positions taken or not in the masculinity discourses around different axes of variation. 27

Qualitative study with stakeholders

To identify individual and societal factors and strategies to support and promote anti-VAW masculinity discourses within and across the study settings.

Participant selection and data collection

Participants will be community (NGOs and youth organisations) and government stakeholders (ministries of social work, health, education, gender equality, etc) working in the prevention of VAW with young people. Participants will be identified through a combination of snowball sampling 26 and a web search of institutions fitting the required profile.

In-depth interviews will be used to collect the data. A semistructured discussion guide will be developed based on a literature review and discussions with the national advisory groups. Topics to be explored include: (1) general information about the organisation (aims, target groups, activities, etc), (2) how VAW is conceptualised in their work and/or programmes and (3) suggestions for strategies to promote and support antiviolence masculinities in their setting. Around 10–15 in-depth interviews will be conducted in each country. Data will be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Qualitative content analysis will be used to analyse the data. 29 The transcripts will be coded inductively looking at the manifest and latent content of the text. Codes will be categorised into a group of content that shares a commonality (categories). Later themes representing the overall meaning running through categories will be identified.

Phase 2: CM

To quantify the coherence, patterns of priorities and perceived relationship between the different actions for supporting and promoting anti-VAW masculinities identified in Phase 1.

CM is an MM approach that enables groups of actors to visualise their ideas around an issue of mutual interest and develop common frameworks through a structured participatory process. The steps are: (1) generation of ideas, (2) structuring of ideas through sorting and rating and (3) development of conceptual maps, and finally a collective interpretation of the maps. 30

Data collection and analysis