Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

More Americans are joining the ‘cashless’ economy

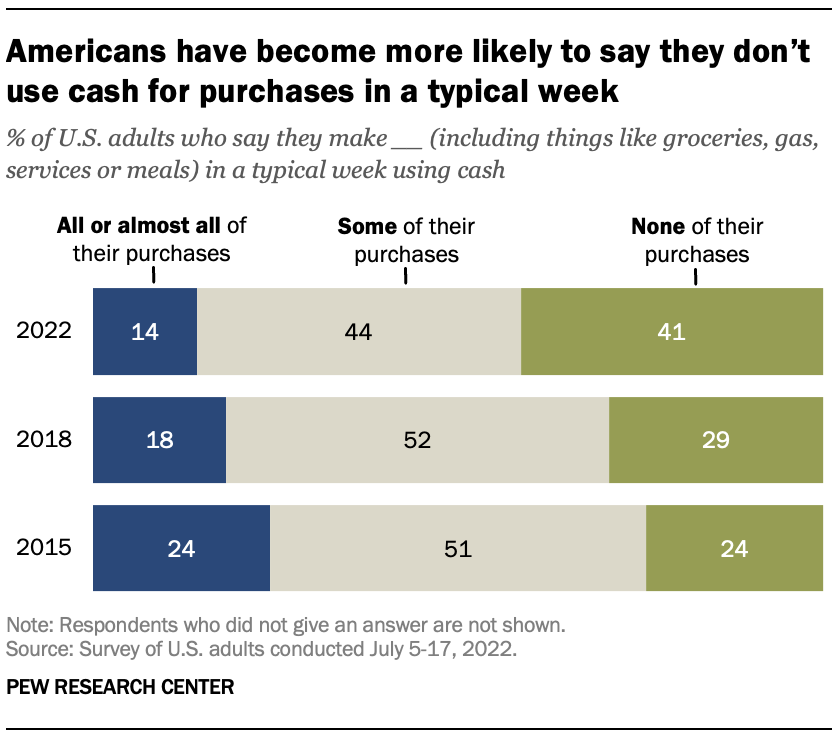

In less than a decade, the share of Americans who go “cashless” in a typical week has increased by double digits. Today, roughly four-in-ten Americans (41%) say none of their purchases in a typical week are paid for using cash, up from 29% in 2018 and 24% in 2015, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

Conversely, the portion of Americans who say that all or almost all of their purchases are paid for using cash in a typical week has steadily decreased, from 24% in 2015 to 18% in 2018 to 14% today. Still, roughly six-in-ten Americans (59%) say that in a typical week, at least some of their purchases are paid for using cash.

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand Americans’ use of cash for everyday purchases and how this practice has changed over time. For the new material in this analysis, the Center surveyed 6,034 U.S. adults from July 5-17, 2022. This included 4,996 respondents from the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. It also included an oversample of 1,038 respondents from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis.

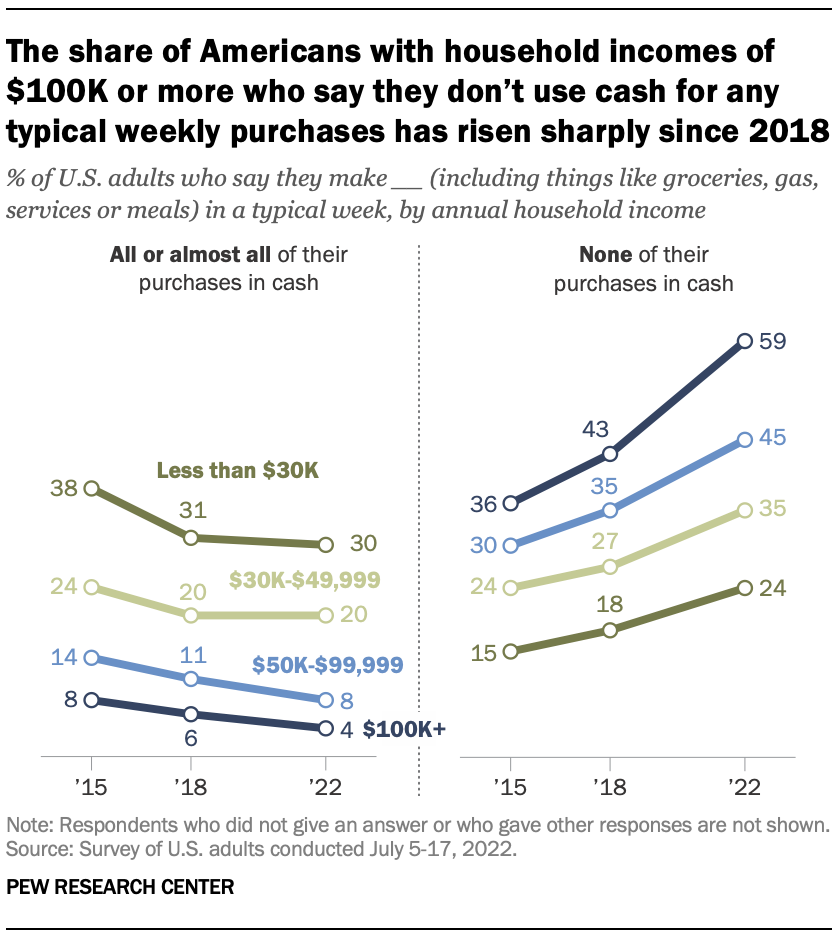

Americans with lower incomes continue to be more reliant on cash than those who are more affluent. Three-in-ten Americans whose household income falls below $30,000 a year say they use cash for all or almost all of their purchases in a typical week. That share drops to 20% among those in households earning $30,000 to $49,999 and 6% among those living in households earning $50,000 or more a year.

Even so, growing shares of Americans across income groups are relying less on cash than in previous years. This is especially the case among the highest earners: Roughly six-in-ten adults whose annual household income is $100,000 or more (59%) say they make none of their typical weekly purchases using cash, up from 43% in 2018 and 36% in 2015.

There are also differences by race and ethnicity in cash usage. Roughly a quarter of Black adults (26%) and 21% of Hispanic adults say that all or almost all of their purchases in a typical week are paid for using cash, compared with 12% of White adults who say the same.

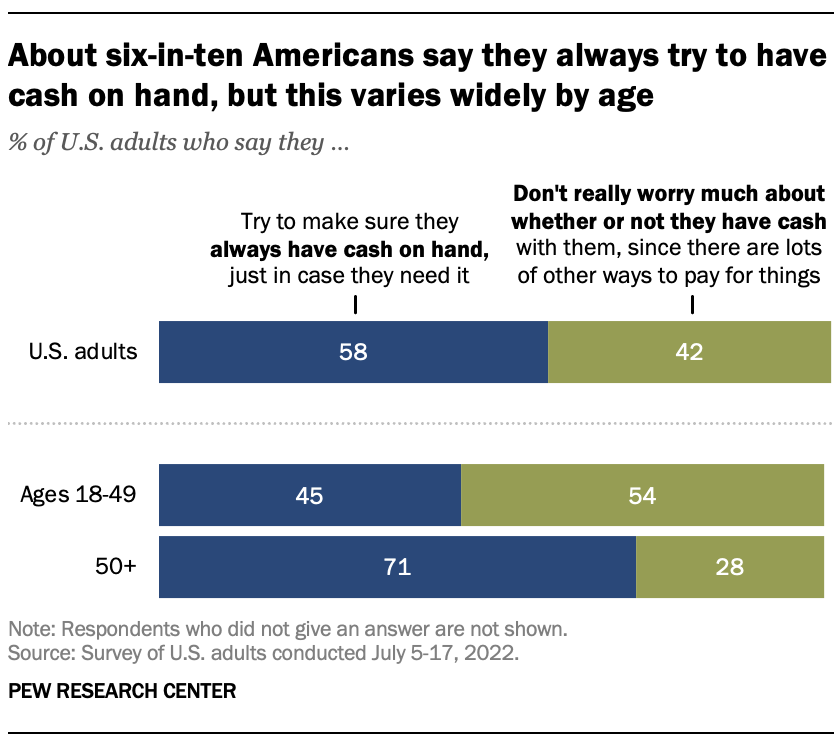

Even though cash is playing less of role in people’s weekly purchases, the survey also finds that a majority of Americans do try to have cash on hand. About six-in-ten adults (58%) say they try to make sure they always have cash on hand, while 42% say they do not really worry much about whether they have cash with them since there are other ways to pay for things. These shares have shifted slightly through the years .

As was true in previous surveys , Americans’ habits related to carrying cash vary by age. Adults under 50 are less likely than those ages 50 and older to say they try to always have cash on hand (45% vs. 71%). And just over half of adults younger than 50 (54%) say they don’t worry much about whether or not they have cash on them, compared with 28% of those 50 and older.

Note: Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis.

Read more from our series examining Americans’ experiences with money, investing and spending in the digital age:

- For shopping, phones are common and influencers have become a factor – especially for young adults

- Payment apps like Venmo and Cash App bring convenience – and security concerns – to some users

- 46% of Americans who have invested in cryptocurrency say it’s done worse than expected

- Economy & Work

- Emerging Technology

- Personal Finances

- Technology Adoption

Michelle Faverio is a research analyst focusing on internet and technology research at Pew Research Center

A look at small businesses in the U.S.

7 facts about americans and taxes, key facts about asian americans living in poverty, methodology: 2023 focus groups of asian americans, 1 in 10: redefining the asian american dream (short film), most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Related Expertise: Payments and Transaction Banking , Financial Institutions , Economic Development

How Cashless Payments Help Economies Grow

May 28, 2019 By Markus Massi , Godfrey Sullivan , Michael Strauß , and Mohammad Khan

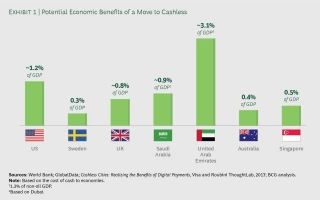

Cash is no longer king. In fact, economies that are more cash intensive tend to grow slowly and miss out on significant financial benefits. Conversely, economies that switch to digital are more successful; the switch can boost annual GDP by as much as 3 percentage points, BCG research shows.

Numerous examples around the world illustrate how cashless payments are economic propellers. Bangladesh’s bKash, which enables transfers via mobile phones, has spurred growth and boosted financial inclusion in that country. The upside comes not from more money but from digital’s role in simplifying the process of sending and receiving payments. Among advanced economies, Sweden and South Korea have moved steadily away from cash. (Cash transactions in Sweden made up less than 2% of the value of payments in 2018, for example.) The result has been a shrinking gray economy, booming online commerce, and a sharp reduction in fraud.

And yet, despite the evidence, there is little sign the world will go cashless anytime soon. Cash remains the world’s most widely used payment instrument. Perhaps surprisingly, the global ratio of cash to GDP rose to 9.6% in 2018, compared with 8.1% in 2011 . In Europe, 80% of point-of-sale transactions are still conducted in cash. People have a strong emotional connection to notes, coins, and currency—and a lingering distrust of digital alternatives.

Slow progress toward cashless economies may be a source of frustration to policymakers, merchants, and financial institutions, all of which stand to accrue benefits from digital. However, there are steps they can take. The right strategies, incentives, infrastructure, and regulation can encourage innovation and boost public confidence in noncash systems. Partnerships, both public and private, can also be critical in marshaling expertise and creating momentum. The tools are in place. All that is required to move forward is the will to act.

The right strategies, incentives, infrastructure, and regulation can boost public confidence in noncash systems.

Copy Shareable Link

Cash Versus Digital

Despite huge growth in smartphone adoption and increasing demand for digital banking, the majority of countries remain heavily dependent on cash. Some 2 billion people globally do not have a bank account, showing that cash remains essential to financial inclusion. And cash is entrenched in the economies of many developed markets. In the UK, the broad measure of money supply, encompassing coins, notes, and cash-like instruments, reached £82 billion in late 2018, compared with about £68 billion four years previously.

Cash is popular because it is user-friendly. It is inclusive, trusted (it does not require intermediation by third parties), accessible, and reliable. It doesn’t require point-of-sale (POS) technology and can’t be hacked or undermined by a loss of power, a cyber attack, or a system failure. Spending cash does not create a data point that might be exploited for cross-selling.

Still, cash is inherently problematic. Undeclared payments in cash lead to tax gaps, and there are costs associated with handling, printing, transporting, and safeguarding cash. One major North American bank spends approximately $5 billion per year processing cash and check transactions and servicing ATMs. In the UK, the cost of free-to-the-customer ATM withdrawals is estimated at about £1 billion a year. Where ATM fees are charged, they are regressive, impacting lower-income demographics more than others.

Cash is inherently problematic.

Payments using a card, app, or computer, conversely, are transparent, clean, and usually quite simple. No trips to the ATM are required, and there’s no need to worry about carrying large amounts of cash in public. There is no cost of handling (although those savings are more than offset by card fees paid by merchants and indirectly by customers).

Further, because cards, apps, and other digital solutions make it easier to send and receive money, they increase economic activity and generate a wide array of financial and nonfinancial benefits.

BCG estimates that a move to a cashless model would add about 1 percentage point to the annual GDPs of mature economies and more than 3 percentage points to those of emerging economies. (See Exhibit 1.) One reason is that mobile money can increase the velocity of value transfers. In addition, digital transactions provide more transparency, making it easier to offer and obtain financing.

In an increasingly urbanized world, many cities (among them Bucharest, Seoul, Dubai, Madrid, and New York City) have introduced smart-city initiatives, leveraging digital to improve lives across a variety of parameters. Digital-payments technology is part of that equation, and one study estimates that increasing digital payments in 100 leading cities could generate direct net benefits of $470 billion per year. Small businesses in particular may benefit, with mobile payments enabling them to rent, buy, and get paid more easily.

Cashless payments can help supervisors, central banks, and commercial banks do better jobs. Electronic payments enable more comprehensive oversight and monitoring and can inform central banks’ monetary and economic policies. More visibility aids credit process management, allowing banks to make more-informed lending decisions. Cashless societies may also bring less obvious benefits: During the European sovereign debt crisis in 2012, some economists argued that moves by central banks to cut interest rates to below zero would be ineffective without a concurrent ban on cash. If people must pay to make bank deposits, it makes sense to keep money under the mattress.

Challenges in Making the Switch to Digital

Digital is an attractive alternative where the cost of cash is high (transport, ATM servicing, security, labor), where technology uptake is accelerating, or where the government struggles to collect sales tax. Numerous countries meet one or more of these criteria, according to an analysis in Harvard Business Review. They include developed markets such as France, Belgium, Spain, and Germany. Still, barriers to uptake remain. We have identified five principal areas of resistance. (See Exhibit 2.)

The High Cost of Electronic Payments. Electronic payments incur significant fees and charges. The British Retail Consortium said in 2018 that, despite regulation of interchange fees, the all-in cost of digital payments had risen in 2017. UK retailers spent an additional £170 million to process card payments, for a total cost of almost £1 billion. Increasing card costs were driven entirely by scheme fee increases, which rose 39%, measured as a percentage of turnover; the problem was exacerbated by limited market competition, the BRC said. Most payments systems are monopolies or duopolies.

A Lack of Customer-Centric Solutions. Payments solutions are often designed without customers’ needs in mind and with a focus on technology rather than user-friendliness. Many countries offer a fragmented patchwork of solutions that lack interoperability. In many cases, you cannot make a payment from one brand of e-wallet to another. Consumers habitually need to carry multiple cards to meet their daily needs. As a result, the penetration rates of person-to-person (P2P) solutions have remained relatively low (below 15%) outside the frontier markets of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.

Minimal Coordination Between Government Entities. Lacking a central authority to drive transformation and coordination, projects are likely to fail. In addition, a lack of proper governance, planning, and education on the implementation frontline is likely to result in fragmentation, bureaucracy, and parallel processes.

Insufficient Trust in Electronic Payments. Banks and companies are under rising pressure to protect their customers against cyber attacks. More than a few large companies with global operations have been hacked in recent years, resulting in massive losses of customer data. The UK’s national crime agency said in April 2018 that seven of the country’s biggest banks reduced operations or shut down systems following an attack the previous year. One reason is that, in many cases, attempts to increase cyber resilience do not keep pace with the rapid uptake of digital payments.

In some countries, consumers are concerned about the impact of digital payments on the cost of living and their control over their own budget. Japanese consumers remain wedded to cash, for instance, and visitors to the country are often struck by how many transactions are still conducted using notes and coins compared with neighboring China. Uptake in Germany is also relatively slow.

The data created by digital transactions is a valuable commodity. It may bring significant benefits to companies, even though consumers in many countries experience a “trust gap” and are less certain of those benefits. Even in Sweden, the most cashless society globally (about three-quarters of all purchases are made by card), there are residual doubts, particularly over security. In early 2018, Sweden’s central bank governor, Stefan Ingves, urged his government to consider the vulnerability of the payment network in case of extreme circumstances.

The Absence of Supporting Infrastructure. Infrastructure is a key element of a thriving payments ecosystem. Equally, its absence can be a hindrance. Rural areas in particular may not have infrastructure in place. In some places, there is a gender divide, with women excluded from internet access. In many countries delays of two to three days in real-time interbank transfers are common. The necessary standards to support infrastructure are also often absent.

For a digital-payments system to take root, support in the form of legal frameworks, electrical networks, and security is also necessary.

How Policymakers Have Driven Uptake

In September 2016, the G20 heads of state and government endorsed the High-Level Principles of Digital Financial Inclusion (HLPs), recognizing the capacity of digital to help people get access to financial services. Certainly, countries with dedicated digital policies and infrastructure have seen faster progress. Examples abound:

- In Singapore, cashless payments took a major step forward in 2017 with the introduction of PayNow, a national real-time payment platform.

- South Korea saw accelerating adoption after introducing end-of-year tax credits for up to 30% of spending on debit cards.

- Sweden has rolled out an array of policies encouraging cashless payments, from eliminating infrastructure such as ATMs while putting in place enabling measures such as electronic know-your-customer (e-KYC) capabilities and real-time payments and by granting stores the right to refuse cash. A tangential impact has been a surge in tax receipts, with value-added tax rising nearly 30% over five years.

- The Reserve Bank of Australia has taken action to address the high cost of digital payments, capping interchange fees and putting a ceiling on card surcharges for small businesses. The moves led to a US$11 billion decline in merchant payment costs and an acceleration in the growth of card transactions. A similar cap in the US in 2011 led to an 8% rise in credit card usage.

An emerging group of “payments tigers” have also made especially rapid progress. Poland, for example, saw card transactions increase from fewer than 30 per capita in 2010 to approximately 125 in 2017, driven by initiatives such as Cashless Poland, a public-private partnership to support cashless payments for small businesses.

Numerous initiatives are underway in Africa. Ghana is digitizing with the aim of improving access to financial services, and Malawi has seen a sharp rise in cashless transactions. Rwanda aims to become a cashless economy by 2024. In late 2018, the nation’s central bank launched a regulatory sandbox for testing digital payment solutions.

Clearly, given the diversity of economic systems around the world, there’s no single solution that will guarantee a seamless transition. Still, several foundational elements raise the chances of a successful digital journey.

Laying the Foundations

Laying the foundations for a cashless economy should typically begin with a holistic and overarching national payments agenda, driven by a consortium of key stakeholders including the government, the central bank, financial institutions, consumer protection agencies, and merchants. The government should determine a timeline and a target end state, based on a thorough assessment of the technological, competitive, and regulatory landscape and benchmarking of functional requirements and enablers. (See “Enablers of a Cashless Economy” for two ways in which stakeholders can support an environment conducive to a cashless economy.)

Begin with a holistic and overarching national payments agenda.

Enablers of a cashless economy.

In addition to taking direct action to effect cashless transactions, stakeholders will benefit from helping to create an environment that is conducive to a cashless economy. Two areas of focus stand out as being particularly valuable.

Safeguarding of Consumer Interests. Consumer protection is vital. One regulatory initiative that addresses this issue is Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, which came into force in May 2018. The GDPR has increased consumer confidence by requiring companies to safeguard consumer data and seek explicit permission for its commercial use. Government-mandated means of streamlining dispute resolution mechanisms would further bolster consumer protection and confidence, building comfort with the notion of a cashless economy.

An Ecosystem of Innovation. One in four fintechs globally is focused on payments. They bring with them, of course, a new focus on digital technologies. Several central banks are now evaluating the potential of these technologies, including blockchain and digital currencies, which may promote financial inclusion and increase efficiency through disintermediation and faster settlement cycles. Open-banking initiatives in many countries are encouraging collaboration between financial institutions and startups, leading to more data sharing, increased cross-selling, and the emergence of payments ecosystems.

Appropriate governance and operational structures must be put in place. These would include establishing an overarching body to manage strategy and facilitate alignment and an operational committee to provide feedback and identify issues as projects move forward.

Industry stakeholders should be closely involved, providing both technical and market expertise.

Finally, teams driving change need to be multidisciplinary, bringing together skills and know-how spanning economics, technologies, and payments.

It makes sense to start small, targeting low-value, high-frequency transactions. However, it pays to think big in terms of collaboration and long-term implementation. BCG has identified five levers that can drive the transformation process. (See Exhibit 3.)

Establish the right incentives. Targeted incentives will encourage consumers and merchants to consider moving away from cash. This might be achieved through reducing the cost of digital payments, introducing cash-handling charges, or restricting the use of cash above certain thresholds (the EU is currently considering this final measure). In Sweden, a consortium of banks launched a free mobile payments app, which was adopted by 50% of the population within four years of launch.

PromptPay , the electronic payment service under the Thai government’s e-payment plan, encouraged uptake by removing charges for online banking. Chinese mobile payment leaders Alipay and WeChat Pay are engaged in an ongoing battle to attract users to their e-wallets, offering incentives that include cash rebates, free bus rides, and even the chance to win gold.

Governments and companies might also consider consumer-friendly schemes such as weekly prize drawings based on transaction IDs or systems with specific demographics in mind.

Encourage competition and ensure a level playing field. Competition naturally exerts downward pressure on prices and encourages innovation, helping to offset the high cost of electronic payments. Measures to enable point-of-sale solutions are likely to help, as are rules for transparency regarding fees. And governments can seek to actively support innovation. The UK, for example, offers research and development tax relief and has introduced a number of tax-related initiatives as part of the National Innovation and Science Agenda, including for investors in startups. The country’s Faster Payments Central Infrastructure is open to established banks and challengers and creates a mechanism for fintechs to access payment systems.

Some countries encourage competition by encouraging or enabling the creation of privately owned payment rails. This has long been the case in the US, where The Clearing House operates several privately owned payment rails that integrate with the federally owned rails.

Provide world-class supporting infrastructure . Infrastructure is the key enabler of a cashless payments model and should encompass the internet, mobile and payments technologies, regulation, security, and electricity networks. Governments should in parallel encourage innovations that promote real-time interbank payments for retail transactions and strengthen operations through new business and operating models.

Already, some countries have transferred responsibility for payments infrastructures from central banks to private companies or consortiums of banks. The UK Faster Payments Service, an initiative to reduce payment times between bank accounts, is run by privately owned Vocalink, for instance. In 2018, a group of Australian financial institutions and the Reserve Bank of Australia launched the New Payments Platform, which is based on ISO 20022 messaging formats and enables consumers, businesses, and government agencies to make real-time, data-rich payments between accounts. And Hong Kong and Singapore, among others, have built multicurrency payment systems for interbank transfers, strengthening their positions as global trading hubs.

Streamline and enforce regulations. Targeted and proportional regulation can strengthen confidence in electronic payments and enforce financial inclusion. Initiatives such as rapid dispute resolution mechanisms, licensing schemes, and fee caps have been highly effective in boosting the uptake of cashless solutions.

A strong and proactive regulator is essential. For example, the US regulator made a big push after 9/11 to enforce an electronic check exchange standard. If the regulator does not make this kind of effort (for example, in real-time payments), everything takes longer.

Partner with the private sector. Policymakers should seek to collaborate with stakeholders to foster innovation; already around the world many are doing so. Thai state authorities, for example, have joined with the private sector to launch the National e-Payment Master Plan. The plan’s PromptPay initiative enables interbank fund transfers using mobile phones and has signed up more than 2 million merchants to QR-code payment. In Europe, the Cashless Poland Foundation provides small and medium-sized retail businesses with point-of-sale terminals and subsidizes them to take low-value card payments, which otherwise might not be cost-effective. Noncash payments in Russia grew from approximately 25 per capita in 2010 to roughly 150 in 2017, amid collaboration between banks and government. Russia’s Sberbank, with its 55% market share, employed 10,000 meet-and-greeters in bank branches to provide information and encourage adoption.

As digital lifestyles expand and more people around the world get connected, it makes sense that payment systems will adapt. Consumers, companies, and governments stand to benefit, and the rise of e-commerce requires an efficient electronic payments infrastructure. However, after thousands of years of fiat currencies, policymakers and corporate leaders should not underestimate the challenges. The solution should be a holistic approach, comprising the right infrastructure, legal frameworks, technologies, and a willingness to partner and collaborate. The task is complex, but the prize is faster growth and an economy enabled for the future.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

Managing Director & Partner

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Subscribe to our Financial Institutions E-Alert.

This is how many Americans never use cash

The share of Americans who go cashless in a typical week is on the rise. Image: Unsplash/naipo.de

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Michelle Faverio

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} United States is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, united states.

- An increasing number of Americans don't use cash to make any purchases in a typical week.

- There are differences based on income and ethnicity as well.

- More than half of Americans still like to have cash available, though, just in case.

In less than a decade, the share of Americans who go “cashless” in a typical week has increased by double digits. Today, roughly four-in-ten Americans (41%) say none of their purchases in a typical week are paid for using cash, up from 29% in 2018 and 24% in 2015, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

Conversely, the portion of Americans who say that all or almost all of their purchases are paid for using cash in a typical week has steadily decreased, from 24% in 2015 to 18% in 2018 to 14% today. Still, roughly six-in-ten Americans (59%) say that in a typical week, at least some of their purchases are paid for using cash.

Americans with lower incomes continue to be more reliant on cash than those who are more affluent. Three-in-ten Americans whose household income falls below $30,000 a year say they use cash for all or almost all of their purchases in a typical week. That share drops to 20% among those in households earning $30,000 to $49,999 and 6% among those living in households earning $50,000 or more a year.

Even so, growing shares of Americans across income groups are relying less on cash than in previous years. This is especially the case among the highest earners: Roughly six-in-ten adults whose annual household income is $100,000 or more (59%) say they make none of their typical weekly purchases using cash, up from 43% in 2018 and 36% in 2015.

There are also differences by race and ethnicity in cash usage. Roughly a quarter of Black adults (26%) and 21% of Hispanic adults say that all or almost all of their purchases in a typical week are paid for using cash, compared with 12% of White adults who say the same.

Even though cash is playing less of role in people’s weekly purchases, the survey also finds that a majority of Americans do try to have cash on hand. About six-in-ten adults (58%) say they try to make sure they always have cash on hand, while 42% say they do not really worry much about whether they have cash with them since there are other ways to pay for things. These shares have shifted slightly through the years .

As was true in previous surveys , Americans’ habits related to carrying cash vary by age. Adults under 50 are less likely than those ages 50 and older to say they try to always have cash on hand (45% vs. 71%). And just over half of adults younger than 50 (54%) say they don’t worry much about whether or not they have cash on them, compared with 28% of those 50 and older.

Note: Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution Network has built a global community of central banks, international organizations and leading blockchain experts to identify and leverage innovations in distributed ledger technologies (DLT) that could help usher in a new age for the global banking system.

We are now helping central banks build, pilot and scale innovative policy frameworks for guiding the implementation of DLT, with a focus on central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) . DLT has widespread implications for the financial and monetary systems of tomorrow, but decisions about its use require input from multiple sectors in order to realize the technology’s full potential.

“Over the next four years, we should expect to see many central banks decide whether they will use blockchain and distributed ledger technologies to improve their processes and economic welfare. Given the systemic importance of central bank processes, and the relative freshness of blockchain technology, banks must carefully consider all known and unknown risks to implementation.”

Our Central Banks in the Age of Blockchain community is an initiative of the Platform for Shaping the Future of Technology Governance: Blockchain and Digital Assets.

Read more about our impact , and learn how you can join this first-of-its-kind initiative.

Have you read?

How japan is moving towards a cashless society with digital salary payments , does going cashless hurt financial inclusion, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Financial and Monetary Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Revitalizing the future economy: Critical mineral derivatives could bring stability

Reese Epper, Brad Handler and Morgan Bazilian

April 29, 2024

The latest on the US economy, and other economics stories to read

April 26, 2024

How fintech innovation can unlock Africa’s gaming revolution

Lucy Hoffman

April 24, 2024

Can you answer these 3 questions about your finances? The majority of US adults cannot

Michelle Meineke

It’s financial literacy month: From schools to the workplace, let's take action

Annamaria Lusardi and Andrea Sticha

The global supply of equities is shrinking – here's what you need to know

Emma Charlton

A Cashless Society: Facts and Issues

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 November 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Yukinobu Kitamura 3

Part of the book series: Hitotsubashi University IER Economic Research Series ((HUIERS,volume 48))

7188 Accesses

3 Altmetric

In this chapter, I would like to describe my views on the development of a cashless society. We will first examine statistics related to cashless payments. When calculated to include bank transfers/account transfers, the cashless payment ratio reaches as high as 92% in Japan, which is not a low figure even among developed countries.

With regard to the choice of payment method, empirical studies and observed facts indicate that the cost structure is much more complex than the cost function considered by economic theorists, and that there are differences among retailers in their attitudes toward pricing and discounts.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

7.1 Introduction

In this chapter, I would like to describe my views on the development of a cashless society. We will first examine statistics related to cashless payments. The cashless payment ratio presented by the Japanese government represents the ratio of the amount paid with credit cards, electronic money, and debit cards to the amount of private final consumption expenditure, and it has been pointed out that the value of this ratio in Japan was 18.2% in 2015, which was quite low among developed countries. However, this statistic does not include bank transfers/account transfers and other electronic payments that households and businesses use on a daily basis, and is not considered to be a useful statistic when considering a cashless society. When recalculated to include bank transfers/account transfers, the cashless payment ratio reaches as high as 92% in Japan, which is not a low figure even among developed countries.

With regard to the choice of payment method, empirical studies and observed facts indicate that the cost structure is much more complex than the cost function considered by economic theorists, and that there are differences among retailers in their attitudes toward pricing and discounts. It is also clear that retailers have different attitudes toward pricing and discounting, and that the fact that cash payments are still used to some extent may reflect the preferences of retailers as well as consumers.

With regard to the merits of going cashless, most of the issues discussed are based on the assumption that cash will be abolished, and do not identify the advantages of going cashless while maintaining cash. At the same time, the disadvantages also relate to special cases where cash payments are rejected and the scale and immediacy of crime in cyberspace compared to cash, and do not discuss the disadvantages created by cashlessness itself.

As for policy issues, we discuss measures that will lead to the realization of a cashless society, including the creation of a system and the fostering of a competitive environment for businesses to increase the quality and diversity of their payment methods, and the promotion of digitization, with the government taking the lead. The interpretation here is that a cashless society will emerge as a by-product of the industrial revolution that has been underway since the end of the twentieth century, centered on the development of information and communications.

7.2 Statistics Related to the Cashless System

Among some statistics that capture the reality of cashless payments, we discuss two indicators that we felt needed to be explained.

7.2.1 Cashless Payment Ratio

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry's “Fin Tech Vision” defines the cashless payment ratio as the amount of cashless payments (payments made with credit cards, debit cards, and electronic money) as a percentage of private final consumption expenditure. In Japan, the ratio was 18.2% as of 2015, which is quite low, and the government set a numerical target (Key Performance Indicator: KPI) in its Future Investment Strategy 2017 to raise the ratio to around 40% over the next 10 years.

The figures and future numerical targets for the cashless payment ratio have been circulated through the mass media and other media, and there is a widespread perception that Japan is a cash-based society compared with other developed countries. However, we consider the progress of cashless society not only in terms of the quantitative aspect, such as the increase in the ratio of cashless payment methods used, but also in terms of qualitative improvements, such as the addition of new value that contributes to user convenience and the provision of payment methods at lower prices than in the past. Also, as Fuchida ( 2018 ) writes, the cashless payment ratio set as a KPI in the “Future Investment Strategy 2017” ignores traditional electronic payment methods such as bank transfers, automatic deductions, and account transfers, and it does not include inter-personal transfers between mobile phones or Payment Initiation Service Provider (PISP)-type payments are also not considered. In order to take these points into account, we proposed to add the share of bank transfers/account transfers in private final consumption expenditure.

However, it should be noted that transfers/account transfers include direct debits related to the use of credit cards and so on, thus simply adding them up may result in double counting. Here, we assume that all credit card payments are included in transfers/account transfers, and recalculate the ratio of cash and cashless payments, which were 8 versus 92% in 2015 data. This means that electronic payments accounted for 92% of the total, while cash payments accounted for less than 10%. At the same time, a recalculation of the same data for Germany, which was identified as having a lower cashless payment ratio than Japan, showed a ratio of 2.58 to 97.42%. According to this definition, Germany was even more cashless than Japan. Interestingly, the same recalculation for Singapore, which had the highest cashless payment ratio, showed that the ratio was 16.52 versus 83.48%, indicating that Singapore was lagging behind Japan and Germany in cashless payments. As for South Korea, which had a high cashless payment ratio of 90%, the ratio was 0.43 versus 99.57%, which means that the country had almost completely achieved cashless payments. This seems to be an overestimation of cashlessness, given the realities in South Korea. Furthermore, I think it is a matter of national accounts in China; the amount of credit card payments is more than twice as large as private final consumption expenditure. Whether this is because credit card payments include payments other than private final consumption expenditure or because private final consumption expenditure is underreported, cannot be determined for China, which is often mentioned as a country that is making progress in going cashless, strict international comparisons using statistics should be avoided (see Nakajima, 2017 ).

According to the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI, 2016 , 2017 ) in BIS, the cashless payment ratio in Japan appears to have increased steadily from 14.3% in 2011 to 18.2% in 2015. However, if we recalculate the ratio to include bank transfers and direct debits, the ratio remains almost unchanged at 8.48 versus 91.52% in 2011.

So what is the reality? To give an overview of the flow of funds in the household sector in Japan, including my personal experience, most salaries and other income are paid by bank transfer. From this, monthly expenditures are made, but the majority of housing, utilities, transportation and communications, and education are paid by direct debit. Durable consumer goods such as clothing, footwear, furniture, and household goods are also likely to be paid for by credit card or other means of payment rather than cash. The only areas of household consumption that are likely to be paid for in cash are food, education and entertainment, health care, and others. The total share of these items is estimated to be about 50% of total expenditures at most.

As will be discussed later, the choice of means of payment differs according to the range of payments, with credit card payments and bank transfers/direct debits being chosen for high-value expenditures exceeding 10,000 yen, and electronic money being used more frequently in recent years for payments of 1,000 yen or less. Taking these factors into account, there is still a possibility that cash will be used for payments in the range between 1,000 yen and 10,000 yen. It is not surprising to consider this to be about 10% of total household spending.

In summary, the government's statistic that cash spending accounts for 80% of private final consumption expenditure, including households, does not reflect reality, and although individual differences may exist, it is thought that cash spending is at most 10%, with the remaining 90% being paid electronically.

This chapter is not interested only in retail payments in Japan, but also in trends in private (household and corporate) payments in the Japanese economy as a whole and the financial system's response to these trends. In particular, when considering the financial system's response, it is desirable to consider the entire payment system, including bank transfers and account transfers as an issue.

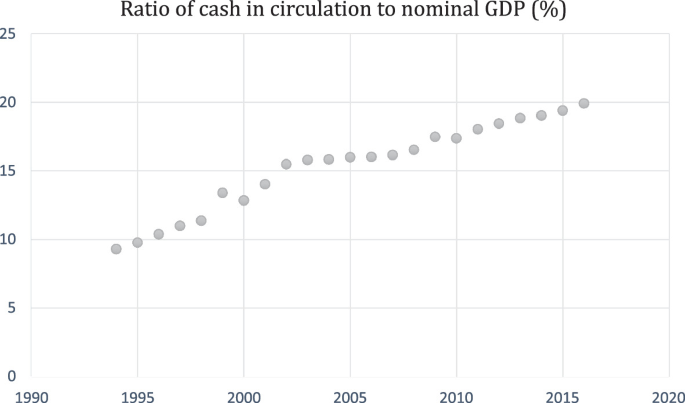

7.2.2 Ratio of Cash in Circulation to Nominal GDP

According to Bank of Japan ( 2017 ), the ratio of cash balances in circulation to nominal GDP was 19.4% in 2015, the highest among the CPMI member countries. The Bank's explanation for this high cash balance is as follows. (1) The demand for cash as a means of storing value is quite high, reflecting the high level of security in the country, the low level of counterfeit currency, the high level of public confidence in banknotes, and the low opportunity cost of holding cash due to low interest rates. (2) Cash is generally accepted as a means of payment. This is because cash is valued for its various characteristics, such as compulsory acceptability, general acceptability, finality, and anonymity.

As is a common problem in economics, it is impossible to explain economic variables that change over time with constant institutions and characteristics. Please see Fig. 7.1 . In 1994, the ratio was 9.26%, which is not very high by international standards. It is not likely that the institutions and characteristics used by the BOJ to explain the ratio in Japan doubled between 1994 and 2016. It is unlikely.

Ratio of cash in circulation to nominal GDP (%)

Rather, the background here is probably that the Bank of Japan has continued monetary easing almost consistently and has increased the supply of currency (base money) at a pace faster than the rate of economic growth. I think there is a problem in linking this statistic to trends in the demand for currency by the private sector, including households, and the resulting slump in cashless payments.

7.3 Selecting a Payment Method

7.3.1 from the results of empirical research.

The choice of payment method depends on the size of the payment, and the main payment method is selected according to the size of the payment, as was established in an accumulation of theoretical and empirical studies in this area to date: Kitamura ( 2005 , 2010 ); a series of studies by the Bank of Canada (Bagnall et al., 2016 ; Kosse et al. 2017 ; Wakamori et al., 1998 ; Shy, 2001 ), and Garcia-Swartz et al. ( 2006a , 2006b ). Specifically, cash or electronic money is used for small payments of 1,000 yen or less, cash or debit cards for payments of 1,000 to 10,000 yen, credit cards for payments of 10,000 yen to 50,000 yen, and bank transfers for payments of 50,000 yen or more. In terms of the scale of retail outlets, sales of 1,000 yen or less are mainly at convenience stores and station kiosks, sales of 1,000–10,000 yen are mainly at supermarkets and individual specialty retailers, purchases of 10,000–50,000 yen are at department stores. For purchases of more than 50,000 yen, it would be high-end consumer durables specialty stores and high-end service stores. Each retailer already offers a payment method that matches its own payment range. In other words, convenience stores and kiosks offer electronic money such as Suica, WAON and nanaco; supermarkets offer credit cards with low annual fees; and department stores offer membership cards with credit card functions that charge a modest annual fee and provide extensive customer service.

If the cashless society is to be further advanced, the remaining areas of cash settlement will be (1) substitution of electronic money and debit cards for payments of small changes of 1,000 yen or less, and (2) substitution of credit cards, debit cards, and electronic money for payments at supermarkets and specialty retailers of between 1,000 yen and 10,000 yen.

In fact, in this field as well, supermarket e-money has expanded its charge limit to 50,000 yen and is building a system capable of handling payments of 10,000 yen or less. In addition, Suica and PASMO, which are transportation-related e-money, are working to expand the range of settlement amounts by issuing higher-end cards with automatic balance recharging and credit functions.

As shown in Chap. 5 (originally in Kitamura et al., 2009 ), the frequency of use of small coins such as 1 yen and 5 yen is steadily decreasing with the advent of electronic money, and a coinless system for small coins is under way.

A series of empirical and simulation studies conducted by the Bank of Canada has shown that consumers have a preference for cash that cannot be explained by various costs. So what other factors might be at play here?

7.3.2 Incentives for Choosing Payment Methods

When looking at settlement costs, what is often overlooked are the points given to electronic money and credit cards. From a common sense perspective, this is a return for the savings in management, accounting, and transportation costs associated with cash when using electronic money or credit cards, and at the same time, it is part of a strategy to attract customers by giving them an incentive to continue using electronic money or credit cards. It is also thought to be part of a strategy to attract customers by giving them an incentive to continue using electronic money and credit cards.

On the other hand, credit cards also require retailers to pay a fee, so some offer discounts for cash payments. There are still some long-established sushi restaurants and traditional Japanese cuisine restaurants that only accept cash payment. It is still there.

In this way, the incentives for choosing a payment method vary and do not seem to have a structure that can be statistically lumped together. In addition, the idea that it is desirable for retailers to offer a variety of payment options to acquire customers is not necessarily an accepted idea.

Although bank transfers and account transfers are widely used, they should be available 24 h a day, 365 days a year for convenience, but this is not yet the case in Japan. The 24-h operation of ATMs is also common practice overseas, but this is also not available in many places in Japan.

In the past, banks were not allowed to issue credit cards, but their affiliates issued credit cards in cooperation with credit card brands (Visa, MasterCard, etc.). Even today, when banks are able to issue credit cards, they do so in cooperation with the major credit card brands. As a result, credit card operations and management decisions are based on the judgment of the credit card brands, and may not necessarily be in line with the realities of the Japanese retail industry. The number of credit cards issued in 2017 was 272.01 million, a penetration rate of about 2.6 cards per adult. The conditions for issuing (or obtaining) a credit card in Japan are considered to be looser than those in other countries, and the use of credit cards is increasing. The use of debit cards is limited due to the fact that the number of stores where they can be used is still small and the hours of availability are restricted.

Electronic money cannot be used internationally because it cannot be withdrawn in cash (only one-way charging of cash to electronic money) and its specifications are different from those of foreign electronic money. Cross-border payment is the issue of e-money and Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) to be determined in the near future. From the point of view of foreign travelers, there is also the inconvenience of not being able to use the e-money in Japan that they use in their home country.

As described above, the choice of payment method is not necessarily made under the same conditions, or on equal footing. As mentioned, there is a segregation of payment methods according to industry and payment scale, and it can be judged that cash payment is selected to some extent among them.

7.4 Advantages and Disadvantages of Going Cashless

A problem that sometimes arises in the implementation of economic policy is that in calculating the merits (benefits) and demerits (costs) of a policy, the merits are overestimated and the demerits are underestimated, only to realize the magnitude of the actual demerits after the policy is implemented.

The immediate prospect of a cashless society does not envisage a society in which the circulation of cash currency is completely eliminated. Many of the advantages of a cashless society that many commentators have highlighted, consciously or unconsciously, emphasize the cost-saving effects that would result if cash currency were completely abolished. Naturally, while maintaining cash currency, as we saw in Sect. 7.2 of this chapter, the policy goal is to reduce cash settlements from about 8% of total settlements to about 4%, and if private final consumption expenditure is set at 286 trillion yen in 2016, 4% of that is about 11 trillion yen. In other words, we should discuss the merits and demerits of shifting 11 trillion yen worth of cash payments to electronic payments. There is not much to be gained by discussing the issue too broadly, however.

7.4.1 Advantages of Going Cashless

Fuchida ( 2017 , 2018 ) and Nikkei MOOK ( 2018 ) enumerate the benefits of going cashless.

No cost for production and maintenance of coins and banknotes.

No cost for transportation and storage of cash.

Eliminates the hassle and cost of anti-counterfeiting measures.

Eliminates the public health problem of using coins and paper money.

Enables faster and more efficient transactions.

No need to queue up at a financial institution or ATM to withdraw cash.

Eliminates cash-related costs for financial institutions such as investing in and managing ATMs.

Fuchida also discusses the benefits that will ripple throughout the economy.

Shrinking the underground economy, criminal and terrorist financing, and tax evasion.

Promoting financial inclusion.

Of these advantages listed, (1), (2), (3), and (4) can be achieved if cash is completely abolished, but they do not apply as long as cash currency continues to be issued. As for (2), if the demand for cash declines and the amount in circulation decreases, the cost may be reduced accordingly. The extent to which the number of ATMs and the vehicles to transport cash will be reduced will depend on the amount of the decline in demand. As for (4), currencies are more contaminated by mold than usually thought, and the risk of a pandemic would decrease if the use of currencies declined. Japanese currency is updated relatively frequently, and I have not heard of any cases where it has served as a vector for epidemics.

One of the arguments for (5) is that it eliminates the need to exchange cash and the need to confirm and count amounts. In terms of finality of payment, there is no quicker means of payment than cash payment. Electronic payments, even with debit cards, are slower than hand-delivered cash. It is true, nonetheless, that the time and effort required to confirm and count cash can be reduced if electronic payments are used. The point in (6) is that travel time and waiting time can be eliminated. Even with electronic payments, it takes time to operate a computer terminal or mobile phone, and if the payment does not go well, the customer may have to go to a bank, so it is not possible to assume that alternative payment methods will not eliminate loss of time. (7) Also, as long as cash currency remains, there is a limit to the cost reduction. This is more likely to be brought about by the evolution of FinTech using artificial intelligence (AI) than by going cashless.

Points (8) and (9) have been cited as benefits, considered from an economy-wide perspective. The argument in (8) has been proposed by Rogoff (2017) and many other experts; but empirically, it is unclear to what extent the underground economy and crime would be reduced. Simply put, if there is a separate objective of tax evasion and crime in the underground economy, going cashless will only lead to flight to anonymous payment methods that are alternatives to cash. Public finance economists regularly measure the size of the underground economy, and Japan's underground economy is estimated to be less than 10% of GDP, which is considerably lower than that of other developed countries. The fact that there is little relationship between cash and crime is probably one of the reasons cash can be used with confidence. As for point (9), it has been widely confirmed that citizens of developing countries who had no contact with finance until now have been able to participate in many economic activities by acquiring payment functions through mobile phones. However, this is probably an issue that is not directly related to the cashless society as it happened, because the information and communication industry entered the payment business.

If we assume that cash will continue to exist, there will be additional costs to the existing cash management costs, such as infrastructure development and technology investment for cashless transactions. If we assume that cash will continue to exist, it would be correct to assume that there will be additional costs, such as infrastructure development and technological investment, to existing cash management costs. In this context, if cash management costs are reduced by progress in the shift to cashless transactions, and if there is still a surplus even after investing the extra funds in infrastructure and technology development for cashless transactions, then the shift to cashless transactions will continue. On the other hand, if cash management costs cannot be reduced to such an extent that the cost of additional capital investment becomes a burden, progress toward a cashless society may not be as rapid as it could be.

As we will discuss in Sect. 7.5 of this chapter, if we consider that the shift to a cashless society is a by-product of the evolution of AI and FinTech, particularly in financial institutions, it is difficult and too simplistic to merely compare cash management costs with capital investment costs for a cashless society.

7.4.2 Disadvantages of Going Cashless

When considering the advantages of going cashless, many argued that it would reduce the cost of maintaining cash. The disadvantages of going cashless are, of course, the inconvenience of suppressing the use of cash and the fact that the scale of theft is limited by the physical constraints of cash. With electronic money and virtual currency, theft on a large scale that is unthinkable with cash can, in principle, occur at once.

Some countries, such as Sweden, Denmark, the United Kingdom, and South Korea, have given some retailers the authority to refuse to accept payments in cash in order to promote cashless transactions. One can argue that such measures are necessary to some extent to promote a cashless society, but cash is the so-called last means of payment for those who are alienated from finance. Refusal of cash payment may be acceptable in clubs or schools where the members are fixed, but it is preferable not to allow refusal of cash payment in places where an unspecified number of people may carry out transactions.

To begin with, the government's “Strategy for the Revitalization of Japan, Revised 2014” stated that the government would “work to improve the convenience and efficiency of payments through the widespread use of cashless payments in light of the hosting of the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Tokyo and other events. In other words, the government's proposal to go cashless included the goal of making it more convenient for the rapidly growing number of anticipated foreign tourists.

In this light, we should not be so preoccupied with promoting a cashless society that we inconvenience not only domestic consumers but also foreign tourists in making payments. I myself have been refused cash payments in Denmark and the UK, but I managed to cope with the situation using a highly versatile credit card. In the trend of internationalization, the payment methods that are easy for foreign tourists to use are those that they use in their home countries (e.g., Alipay, Apple Pay, bank debit cards). In order to make these payment methods usable in Japan, it is necessary to create a mechanism to authenticate the payment methods in the Japanese payment system.

Japanese financial institutions are open to the idea of going cashless in the sense of replacing a portion of domestic cash payments with credit and debit card payments, or replacing cash by issuing privately issued digital currency using blockchain technology, but they are very cautious about allowing compatibility with electronic money and debit cards issued overseas. A delay in addressing this part of the problem could lead to the creation of a Galapagos-island-like cashless society specifically evolved only in Japan, which would indirectly exclude foreign travelers.

The other disadvantage is the security problem. On January 26, 2018, 0.5 billion cryptocurrency XEM (currency unit of NEM, equivalent to 58billion yen at market value) was stolen via on-line within ten minutes or so. At the end of March 2018, the entire amount 0.5 billion XEM was converted into other cryptocurrencies and ultimately into legal tender, and the culprit has yet to be caught. The theft of cryptocurrency has often occurred, but this was the first theft on this scale in history. Footnote 1

A robbery of this scale would not have happened in a cash-transport robbery. In other words, to transport 58 billion yen in cash at one time, a truck with a considerable transportation capacity, a considerable number of people, and a considerable amount of time are required, and it is almost impossible to do so without being noticed by a third party.

Coincheck, which was involved in the incident, was found to have a number of problems with its security management after the fact, and was given a business improvement order by the Financial Service Agency (FSA). The incident prompted a review of the FSA's response to the security management system for crypto-currency exchanges under the amended Funds Settlement Law, and on March 8, 2018, the FSA issued business improvement orders to seven exchanges, including Coincheck. Footnote 2

In contrast, debit cards, credit cards, and e-money are properly managed, and banks and other financial institutions may take the view that their security measures are perfect, but as with crypto-currencies, security problems occur where controls are weak. Specifically, there have been frequent incidents of credit card fraud through breaches of credit card information at the retail level. There is also no end to the number of elderly people who become victims of fraud through the use of counterfeit cards and lax cash-card authentication.

It is also impossible to assume that central banks are safe. In fact, although it is unclear how often crises that threaten the security of central banks occur, it seems that attempts are regularly made to use internal email information obtained through unauthorized access to send malware by impersonation.

On February 4, 2016, after business hours, hackers used malware to infiltrate the Bangladesh Central Bank's systems and, using a hijacked account, sent fake money transfer instructions to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York via SWIFT, successfully transferring funds to bank accounts in the Philippines and other locations. The total amount affected by the fraudulent remittance was $101 million, of which about $81 million (about ¥9.2 billion) has not been recovered. It has been reported that such crimes involving central banks have also occurred in Vietnam, Ecuador, and other countries, and the central banks and private banks of each country are required to share information and strengthen security.

As we have already seen, more than 90% of household payments are made electronically, and an even higher percentage of businesses rely on electronic payments. The reality is that cash holdings have been whittled down to a minimum, and the trend toward a cashless society is unlikely to stop. As a result, it is only natural that criminals will shift their focus from cash to electronic payments through the manipulation of digital information. Even if the government promotes the shift to cashless transactions, it should take sufficient security measures, recognizing that the risk will be exposed to consumers and retailers, who are the least security-conscious, and that criminals will exploit this risk.

7.5 Policy Issues

Japanese society is facing a variety of structural problems, including a declining birthrate, aging population, depopulation of rural areas, and difficulties in succeeding for individual businesses. At the same time, advances in information technology (IT) have led to the automatic accumulation of big data via the Internet, and AI has come to be used in the economy and society to replace human judgment through machine learning mechanisms such as deep learning. The financial industry is also being forced to change in the midst of this major historical trend, and the major megabanks are responding with a series of plans to close branches and cut staff.

A cashless society will inevitably emerge as part of the economic and social transformation. It is important to develop the infrastructure, including the legal system, and promote a competitive environment in order to achieve this. Moreover, a cashless society will emerge as a by-product of the industrial revolution centered on the broader development of information and communications, and the cashless society itself will not play a leading role, nor is it appropriate to set it as an independent policy goal.

I would like to point out two policy issues. First, an e-government system should be established as soon as possible to provide highly convenient administrative services and efficient administrative operations by digitizing government administrative procedures and settlements for tax payments, social insurance premiums, and pension benefits in an integrated manner. One of the reasons the Nordic countries are using personal identification numbers to make various administrative services online is to cope with their low population density relative to their land area. It is estimated that Japan's population will reach half of its current level (63.5 million people) around 2100, if demographic trends remain unchanged. It is difficult to imagine what will happen socio-economically if the population density is halved, but in Finland and Sweden, if you go out of the cities to the suburbs, you will find endless forests and lakes with hardly a soul in sight. In England and France, the winters are not so severe, so even if the population density is low, the land can be used as pasture or farmland. In Japan, however, there are many mountains, so the flat land is barely used as farmland, but the mountain forests are almost completely abandoned. In any case, it is almost certain that it will become impossible to provide the same level of administrative services as at present as the population continues to decline.

One of the most advanced examples is the digitization of the Estonian government, which has been introduced by Okina et al. ( 2017 , Chap. 16) and Arikivi and Maeda ( 2016 ). The Estonian government is trying to determine the extent to which the government can digitize the current situation, and this is possible because Estonia is a small country with a population of 1.3 million. However, compared to the current situation where only about 10% of the population has obtained a My Number card, even though the Japanese government has introduced a My Number card (i.e., National Identification Number Card in Japan), it seems a world away.

For example, it is said that more than 60 billion yen is currently required to hold each House of Representatives election. If this could be converted to online voting using the My Number system that each person has, the cost savings would be substantial. In the first place, if voting could be conducted with a fixed voting period, there would be no need to choose a specific voting date among various schedule adjustments. In many ways, e-government would allow for more agile government operations at less cost and with fewer people, but we must change the current situation, which has not even reached the stage of discussing the possibility.

Second, in connection with the shift to a cashless society, the question of what to do with the cash issued by central banks will also be unavoidable. As can be seen in Fig. 7.1 , the ratio of cash balances in circulation to nominal GDP has doubled over the past 20 years. Using the quantity theory of money, a rough estimate is that nominal GDP grew by only 7.6% over the 22 years from 1994 to 2016, while cash grew by 13%. If prices have not changed that much, it means the velocity of cash in circulation has halved. As the shift to cashless transactions progresses, the demand for currency for settlement reasons will decline, and we cannot deny the possibility that it is being held in reserve within households, corporations, and private financial institutions under zero (negative) interest rates. This means that the transmission mechanism of monetary policy is also undergoing a transformation.

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has been pursuing quantitative and qualitative monetary easing since April 2013, but the reason the policy has not been effective is that there may be a discrepancy between the monetary policy tools chosen and the direction of the policy and the trend toward electronic finance and FinTech, as seen in the shift to cashless banking.

As we have seen in this chapter, more than 90% of total payments are made electronically, and if the cashless system continues to advance further, the demand for cash will decline. At present, no major country has decided to abolish the issuance of currency, but it is a natural progression to consider whether to gradually reduce the supply of cash and to issue the minimum necessary, or to circulate a central bank digital currency (CBDC) that can be used in cyberspace.

While Bitcoin and other crypto-currencies/assets have been pointed out as having problems, there is a growing recognition that they are innovations with potential for a variety of applications. Footnote 3

It is not the purpose of this chapter to discuss the future of money. I will only point out the following. As a researcher who has been thinking about this problem, I can say that it is more difficult than expected to devise a digital currency that can be easily carried around like paper money and yet be useful in cyberspace.

7.6 Conclusion

The choice of means of payment by economic agents should be left to the judgment of economic agents, not something that should be made a policy goal. If a particular technology or service is in its early stages and the government intends to foster it, it may be willing to protect or subsidize it for a certain period of time, but payments are already a mature technology, and cash has existed for more than 2,700 years or so.

There is no need for the government to provide incentives to promote a cashless society. In the first place, the act of payment itself is a means for the purpose of consumption of goods and services, not an end in itself. Cashless transactions are the result of the choice of payment methods. As electronic commerce expands further and retailers voluntarily introduce multi-payment functions, the shift to cashless transactions will naturally occur.

Rather, what is important is the argument that a cashless society will be born as a byproduct of the various IT and AI applications resulting from advances in information technology, as they become a response to structural problems such as the declining birthrate, aging population, and depopulation of rural areas.

As a technical response to structural problems, we should not forget that among the policy issues to be considered are also the issues of how to combine and implement policies (policy mix problem) and in what order (policy sequence problem). The private sector has had the unpleasant experience of becoming “Galapagosized”, being left behind by international competition and international standards, while being preoccupied with fighting for a small domestic market share in the name of competition policy. I hope that payment technology will not make the same mistake.

Initially, the NEM Foundation, the custodians of NEM, made an announcement to the effect that the leaked NEM could be automatically tracked by mosaic and that the perpetrators would not be able to redeem it; but in fact, by going through underground exchanges that could not be mosaicked (such as CoinPayments) In fact, they were exchanged. The NEM Foundation has also quickly abandoned its mosaic tracking system. Although crypto-currencies have been thought to be traceable because their transactions are public, this incident has shown that there is considerable demand for criminally involved crypto-currencies to be purchased in exchange for other crypto-currencies. If they could be obtained at low prices,, it became clear that the system would not work.

The security of the crypto-currency itself and the security of exchanges and exchangers are often discussed in a confused manner, but the security of the crypto-currency itself, which uses public key cryptography, and the security of the Internet environment of exchanges are two different issues. The hackers who stole the private key by breaking in through a lax security system have made it an urgent issue to strengthen the security of exchanges and exchangers.

There have been various debates over central banknotes. Black ( 1970 ) and Fama ( 1980 ) have discussed the economy without money, especially monetary, under a general equilibrium model; Woodford ( 2000 ) has discussed monetary policy without money; and central banknotes have been discussed in the literature. Moreover, since Eisler ( 1933 ), Goodfriend ( 2000 ), Buiter ( 2005 ), Rogoff ( 2014 ), Agarwal and Kimball ( 2015 ) and others have made various proposals for mechanisms that could add negative interest rates to money. The possibility of a digital currency issued by a central bank has also been discussed by Barrdear and Kumhof ( 2016 ), Skingsley ( 2016 ), Bordo and Levin ( 2017 ), BIS ( 2018 ), Prasad ( 2018 ), and others.

Agarwal, R., & Kimball, M. (2015). Breaking through the zero lower bound . IMF Working Paper, WP/15/224.

Google Scholar

Allikivi, R., & Maeda, Y. (2016). Miraikokka Esutonia no chosen (Challenges of Estonia, the Futuristic Nation) . Next Publishing.

Bagnall, J., Bounie, D., Huynh, K. P., Kosse, A., Schmidt, T., Schuh, S., & Stix, H. (2016). Consumer cash usage: A cross-country comparison with payment diary survey data. International Journal of Central Banking, 12 (4), 1–61.

Barrdear, J. & Kumhof, M. (2016). The macroeconomics of central bank issued digital currencies . Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No. 605.

Bank of Japan. (2017). “BIS kessai toukei kara mita nihon no riteiru・ooguchi shikinn kesssai shisutemu no tokucyou”(Characteristics of Retail and Large-size Payment System in Japan from BIS payment statistics), Annex to Payment and Settlement Systems Report, Bank of Japan, Payment System Department, February 2017.

BIS. (2018). Central bank digital currencies . BIS Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and Market Committee.

Black, F. (1970). Banking and interest rates in a world without money: The effects of uncontrolled banking. Journal of Bank Research, 1 , 9–20.

Bordo, M. D. & Levin, A. T. (2017). Central bank digital currency and the future of monetary policy . Hoover Institution Economic Working Papers, No. 17104.

Buiter, W. H. (2005). Overcoming the zero bound: Gesell vs. Eisler. mimeo.

CPMI (2016). Statistics on Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems in the CPMI countries , BIS.

CPMI (2017). Statistics on Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems in the CPMI countries , BIS.

Eisler, R. (1933). Stable money: The remedy for the economic world crisis . Search Publishing.

Fama, E., & F. (1980). Banking in the theory of finance. Journal of Monetary Economics, 6 , 39–57.

Article Google Scholar

Fuchida, Y. (2018). Wagakuni no kyasyuresu ka eno kadai (Issues on Cashless Society in Japan), Kikan Kojin Kinyu (Quarterly Journal of Personal Finance). Winter Issue, 2018 , 50–57.

Garcia-Swartz, D., & D., Hahn, Robert W. and Layne-Farrar, Anne. (2006a). The move toward a cashless society: A close look at payment instrument economics. Review of Network Economics, 5 (2), 175–198.

Garcia-Swartz, D., & D., Hahn, Robert W. and Layne-Farrar, Anne. (2006b). The move toward a cashless society: Calculating the costs and benefits. Review of Network Economics, 5 (2), 199–228.

Goodfriend, M. (2000). Overcoming the zero bound on interest rate policy Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 32(4). Part, 2 , 1007–1035.

Kitamura, Y. (2005). Denshi manei no Fkyu to Kessai syudan no sentaku (Diffusion of Electronic Money and Choice of Payment Methods), Kinyu chosa kenkyu kai houkokusyo, (The Report of the Financial Services Research Association in July 2005, No. 34), Chapter 2, pp. 21–37.

Kitamura,Y.(2018) Kyashuresu ka no jittai to sono kadai (Cashless Society: Facts and Issues) Kinyu chosa kenkyu kai houkokusyo (The Report of the Financial Service Research Association), No.60., Chapter 3, July 2018, 67–82.

Kitamura, Y., Omori, M. & Nishida, K. (2009). Denishi manei ga Kahei jyuyou ni ataeru eikyou ni tsuite: jikeiretsu bunseki”(Impact of Electronic Money on Demand for Cash: Time Series Analysis), Financial Review (Ministry of Finance) , May 2009, Vol. 97, No. 5, pp. 129–152.