- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal

This article explores the ethical issues that may arise in your proposed study during your doctoral research degree.

What ethical principles apply when planning and conducting research?

Research ethics are the moral principles that govern how researchers conduct their studies (Wellcome Trust, 2014). As there are elements of uncertainty and risk involved in any study, every researcher has to consider how they can uphold these ethical principles and conduct the research in a way that protects the interests and welfare of participants and other stakeholders (such as organisations).

You will need to consider the ethical issues that might arise in your proposed study. Consideration of the fundamental ethical principles that underpin all research will help you to identify the key issues and how these could be addressed. As you are probably a practitioner who wants to undertake research within your workplace, consider how your role as an ‘insider’ influences how you will conduct your study. Think about the ethical issues that might arise when you become an insider researcher (for example, relating to trust, confidentiality and anonymity).

What key ethical principles do you think will be important when planning or conducting your research, particularly as an insider? Principles that come to mind might include autonomy, respect, dignity, privacy, informed consent and confidentiality. You may also have identified principles such as competence, integrity, wellbeing, justice and non-discrimination.

Key ethical issues that you will address as an insider researcher include:

- Gaining trust

- Avoiding coercion when recruiting colleagues or other participants (such as students or service users)

- Practical challenges relating to ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of organisations and staff or other participants.

(Heslop et al, 2018)

A fuller discussion of ethical principles is available from the British Psychological Society’s Code of Human Research Ethics (BPS, 2021).

You can also refer to guidance from the British Educational Research Association and the British Association for Applied Linguistics .

Ethical principles are essential for protecting the interests of research participants, including maximising the benefits and minimising any risks associated with taking part in a study. These principles describe ethical conduct which reflects the integrity of the researcher, promotes the wellbeing of participants and ensures high-quality research is conducted (Health Research Authority, 2022).

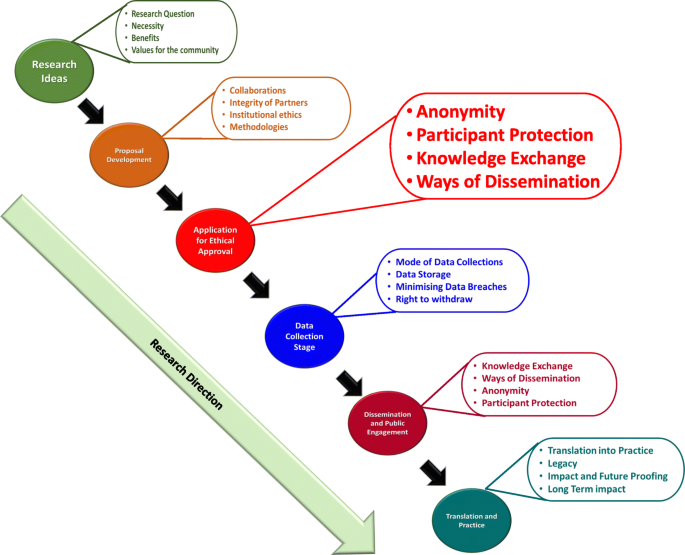

Research ethics is therefore not simply about gaining ethical approval for your study to be conducted. Research ethics relates to your moral conduct as a doctoral researcher and will apply throughout your study from design to dissemination (British Psychological Society, 2021). When you apply to undertake a doctorate, you will need to clearly indicate in your proposal that you understand these ethical principles and are committed to upholding them.

Where can I find ethical guidance and resources?

Professional bodies, learned societies, health and social care authorities, academic publications, Research Ethics Committees and research organisations provide a range of ethical guidance and resources. International codes such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights underpin ethical frameworks (United Nations, 1948).

You may be aware of key legislation in your own country or the country where you plan to undertake the research, including laws relating to consent, data protection and decision-making capacity, for example, the Data Protection Act, 2018 (UK). If you want to find out more about becoming an ethical researcher, check out this Open University short course: Becoming an ethical researcher: Introduction and guidance: What is a badged course? - OpenLearn - Open University

You should be able to justify the research decisions you make. Utilising these resources will guide your ethical judgements when writing your proposal and ultimately when designing and conducting your research study. The Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (British Educational Research Association, 2018) identifies the key responsibilities you will have when you conduct your research, including the range of stakeholders that you will have responsibilities to, as follows:

- to your participants (e.g. to appropriately inform them, facilitate their participation and support them)

- clients, stakeholders and sponsors

- the community of educational or health and social care researchers

- for publication and dissemination

- your wellbeing and development

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (no date) has emphasised the need to promote equality, diversity and inclusion when undertaking research, particularly to address long-standing social and health inequalities. Research should be informed by the diversity of people’s experiences and insights, so that it will lead to the development of practice that addresses genuine need. A commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion aims to eradicate prejudice and discrimination on the basis of an individual or group of individuals' protected characteristics such as sex (gender), disability, race, sexual orientation, in line with the Equality Act 2010.

The NIHR has produced guidance for enhancing the inclusion of ‘under-served groups’ when designing a research study (2020). Although the guidance refers to clinical research it is relevant to research more broadly.

You should consider how you will promote equality and diversity in your planned study, including through aspects such as your research topic or question, the methodology you will use, the participants you plan to recruit and how you will analyse and interpret your data.

What ethical issues do I need to consider when writing my research proposal?

You might be planning to undertake research in a health, social care, educational or other setting, including observations and interviews. The following prompts should help you to identify key ethical issues that you need to bear in mind when undertaking research in such settings.

1. Imagine you are a potential participant. Think about the questions and concerns that you might have:

- How would you feel if a researcher sat in your space and took notes, completed a checklist, or made an audio or film recording?

- What harm might a researcher cause by observing or interviewing you and others?

- What would you want to know about the researcher and ask them about the study before giving consent?

- When imagining you are the participant, how could the researcher make you feel more comfortable to be observed or interviewed?

2. Having considered the perspective of your potential participant, how would you take account of concerns such as privacy, consent, wellbeing and power in your research proposal?

[Adapted from OpenLearn course: Becoming an ethical researcher, Week 2 Activity 3: Becoming an ethical researcher - OpenLearn - Open University ]

The ethical issues to be considered will vary depending on your organisational context/role, the types of participants you plan to recruit (for example, children, adults with mental health problems), the research methods you will use, and the types of data you will collect. You will need to decide how to recruit your participants so you do not inappropriately exclude anyone. Consider what methods may be necessary to facilitate their voice and how you can obtain their consent to taking part or ensure that consent is obtained from someone else as necessary, for example, a parent in the case of a child.

You should also think about how to avoid imposing an unnecessary burden or costs on your participants. For example, by minimising the length of time they will have to commit to the study and by providing travel or other expenses. Identify the measures that you will take to store your participants’ data safely and maintain their confidentiality and anonymity when you report your findings. You could do this by storing interview and video recordings in a secure server and anonymising their names and those of their organisations using pseudonyms.

Professional codes such as the Code of Human Research Ethics (BPS, 2021) provide guidance on undertaking research with children. Being an ‘insider’ researching within your own organisation has advantages. However, you should also consider how this might impact on your research, such as power dynamics, consent, potential bias and any conflict of interest between your professional and researcher roles (Sapiro and Matthews, 2020).

How have other researchers addressed any ethical challenges?

The literature provides researchers’ accounts explaining how they addressed ethical challenges when undertaking studies. For example, Turcotte-Tremblay and McSween-Cadieux (2018) discuss strategies for protecting participants’ confidentiality when disseminating findings locally, such as undertaking fieldwork in multiple sites and providing findings in a generalised form. In addition, professional guidance includes case studies illustrating how ethical issues can be addressed, including when researching online forums (British Sociological Association, no date).

Watch the videos below and consider what insights the postgraduate researcher and supervisor provide regarding issues such as being an ‘insider researcher’, power relations, avoiding intrusion, maintaining participant anonymity and complying with research ethics and professional standards. How might their experiences inform the design and conduct of your own study?

Postgraduate researcher and supervisor talk about ethical considerations

Your thoughtful consideration of the ethical issues that might arise and how you would address these should enable you to propose an ethically informed study and conduct it in a responsible, fair and sensitive manner.

British Educational Research Association (2018) Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018 (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

British Psychological Society (2021) Code of Human Research Ethics . Available at: https://cms.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/BPS%20Code%20of%20Human%20Research%20Ethics%20%281%29.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

British Sociological Association (2016) Researching online forums . Available at: https://www.britsoc.co.uk/media/24834/j000208_researching_online_forums_-cs1-_v3.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Health Research Authority (2022) UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research . Available at: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/uk-policy-framework-health-social-care-research/uk-policy-framework-health-and-social-care-research/#chiefinvestigators (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Heslop, C., Burns, S., Lobo, R. (2018) ‘Managing qualitative research as insider-research in small rural communities’, Rural and Remote Health , 18: pp. 4576.

Equality Act 2010, c. 15. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/introduction (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Research (no date) Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) . Available at: https://arc-kss.nihr.ac.uk/public-and-community-involvement/pcie-guide/how-to-do-pcie/equality-diversity-and-inclusion-edi (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Research (2020) Improving inclusion of under-served groups in clinical research: Guidance from INCLUDE project. Available at: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/improving-inclusion-of-under-served-groups-in-clinical-research-guidance-from-include-project/25435 (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Sapiro, B. and Matthews, E. (2020) ‘Both Insider and Outsider. On Conducting Social Work Research in Mental Health Settings’, Advances in Social Work , 20(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.18060/23926

Turcotte-Tremblay, A. and McSween-Cadieux, E. (2018) ‘A reflection on the challenge of protecting confidentiality of participants when disseminating research results locally’, BMC Medical Ethics, 19(supplement 1), no. 45. Available at: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-018-0279-0

United Nations General Assembly (1948) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights . Resolution A/RES/217/A. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights#:~:text=Drafted%20by%20representatives%20with%20different,all%20peoples%20and%20all%20nations . (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Wellcome Trust (2014) Ensuring your research is ethical: A guide for Extended Project Qualification students . Available at: https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/wtp057673_0.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

More articles from the research proposal collection

Writing your research proposal

A doctoral research degree is the highest academic qualification that a student can achieve. The guidance provided in these articles will help you apply for one of the two main types of research degree offered by The Open University.

Level: 1 Introductory

Defining your research methodology

Your research methodology is the approach you will take to guide your research process and explain why you use particular methods. This article explains more.

Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview

The final article looks at writing your research proposal - from the introduction through to citations and referencing - as well as preparing for your interview.

Free courses on postgraduate study

Are you ready for postgraduate study?

This free course, Are you ready for postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and ensure you are ready to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Succeeding in postgraduate study

This free course, Succeeding in postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Applying to study for a PhD in psychology

This free OpenLearn course is for psychology students and graduates who are interested in PhD study at some future point. Even if you have met PhD students and heard about their projects, it is likely that you have only a vague idea of what PhD study entails. This course is intended to give you more information.

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Tuesday, 27 June 2023

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'Pebbles balance on a stone see-saw' - Copyright: Photo 51106733 / Balance © Anatoli Styf | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Camera equipment set up filming a man talking' - Copyright: Photo 42631221 © Gabriel Robledo | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Applying to study for a PhD in psychology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Succeeding in postgraduate study' - Copyright: © Everste/Getty Images

- Image 'Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal' - Copyright: Photo 50384175 / Children Playing © Lenutaidi | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview' - Copyright: Photo 133038259 / Black Student © Fizkes | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Defining your research methodology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Writing your research proposal' - Copyright free

- Image 'Are you ready for postgraduate study?' - Copyright free

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

100 Questions (and Answers) About Research Ethics

- Emily E. Anderson - Loyola University Chicago, USA

- Amy Corneli - Duke University School of Medicine, USA

- Description

100 Questions (and Answers) About Research Ethics is an essential guide for graduate students and researchers in the social and behavioral sciences. It identifies ethical issues that individuals must consider when planning research studies as well as provides guidance on how to address ethical issues that might arise during research implementation. Questions such as assessing risks, to protecting privacy and vulnerable populations, obtaining informed consent, using technology including social media, negotiating the IRB process, and handling data ethically are covered.

Acting as a resource for students developing their thesis and dissertation proposals and for junior faculty designing research, this book reflects the latest U.S. federal research regulations to take effect mostly in January 2018.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

“The book is extremely informative, well-organized, and an invaluable tool for students, faculty, and literally all researchers across disciplines. I have taught research methods courses for many years, and the ethics and responsible conduct of research for several years, and found this text to be loaded with easily accessible information I find incredibly useful for teaching these courses. The text answers many questions that students typically ask that take considerable effort to answer and eliminates my concern that I am not always providing the most useful or accurate responses. It is extremely informative and well done and is a must for researchers and practitioners engaged in the research enterprise. Well done in all respects! A+.”

“The approach to the book makes it easy to incorporate in a class setting; it is an ideal reference and quick-check for students, but there is still a great deal of substantive material. The questions can provide a ready jumping off point for class discussions and can easily serve as the foundation for class topics and projects.”

“This book will be helpful to both professional and student researchers. As Chair of my institution's IRB, I will be recommending it to my IRB members, and also to my colleagues who are planning to submit protocols for review.”

KEY FEATURES:

- Emphasizes holistic, broader ethical thinking within the regulatory/compliance framework rather than focusing narrowly on compliance with guidance provided by IRBs and federal regulations.

- Offers guidance for helping potential participants make an informed decision about study participation so that researchers ensure that volunteers understand what it entails and give their informed consent without any coercion.

- Offers guidance for preparing an IRB application, a process that is challenging for even the most seasoned researchers.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Part 3 Protecting Privacy and Confidentiality

Part 6 Designing Ethical Research

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

First do no harm: An exploration of researchers’ ethics of conduct in Big Data behavioral studies

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Institute for Biomedical Ethics, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft

Roles Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Faculty of Psychology, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Roles Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

- Maddalena Favaretto,

- Eva De Clercq,

- Jens Gaab,

- Bernice Simone Elger

- Published: November 5, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241865

- Reader Comments

Research ethics has traditionally been guided by well-established documents such as the Belmont Report and the Declaration of Helsinki. At the same time, the introduction of Big Data methods, that is having a great impact in behavioral research, is raising complex ethical issues that make protection of research participants an increasingly difficult challenge. By conducting 39 semi-structured interviews with academic scholars in both Switzerland and United States, our research aims at exploring the code of ethics and research practices of academic scholars involved in Big Data studies in the fields of psychology and sociology to understand if the principles set by the Belmont Report are still considered relevant in Big Data research. Our study shows how scholars generally find traditional principles to be a suitable guide to perform ethical data research but, at the same time, they recognized and elaborated on the challenges embedded in their practical application. In addition, due to the growing introduction of new actors in scholarly research, such as data holders and owners, it was also questioned whether responsibility to protect research participants should fall solely on investigators. In order to appropriately address ethics issues in Big Data research projects, education in ethics, exchange and dialogue between research teams and scholars from different disciplines should be enhanced. In addition, models of consultancy and shared responsibility between investigators, data owners and review boards should be implemented in order to ensure better protection of research participants.

Citation: Favaretto M, De Clercq E, Gaab J, Elger BS (2020) First do no harm: An exploration of researchers’ ethics of conduct in Big Data behavioral studies. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0241865. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241865

Editor: Daniel Jeremiah Hurst, Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, UNITED STATES

Received: July 22, 2020; Accepted: October 21, 2020; Published: November 5, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Favaretto et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The raw data and the transcripts related to the project cannot be openly released due to ethical constraints (such as easy re-identification of the participants and the sensitive nature of parts of the interviews). The main points of contact for fielding data access requests for this manuscript are: the Head of the Institute for Biomedical Ethics (Bernice Elger: [email protected] ), the corresponding author (Maddalena Favaretto: [email protected] ), and Anne-Christine Loschnigg ( [email protected] ). Data sharing is contingent on the data being handled appropriately by the data requester and in accordance with all applicable local requirements. Upon request, a data sharing agreement will be stipulated between the Institute for Biomedical Ethics and the one requesting the data that will state that: 1) The shared data must be deleted by the end of 2023 as stipulated in the recruitment email sent to the study participants designed in accordance to the project proposal of the NRP 75 sent to the Ethics Committee northwest/central Switzerland (EKNZ); 2) The people requesting the data agree to ensure its confidentiality, they should not attempt to re-identify the participants and the data should not be shared with any further third stakeholder not involved in the data sharing agreement signed between the Institute for Biomedical Ethics and those requesting the data; 3) The data will be shared only after the Institute for Biomedical Ethics has received specific written consent for data sharing from the study participants.

Funding: The funding for this study was provided by the Swiss National Science Foundation in the framework of the National Research Program “Big Data”, NRP 75 (Grant-No: 407540_167211, recipient: Prof. Bernice Simone Elger). We confirm that the Swiss National Science Foundation had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Big Data methods have a great impact in behavioral sciences [ 1 – 3 ], but challenge the traditional interpretation and validity of research principles in psychology and sociology by raising new and unpredictable ethical concerns. Traditionally, research ethics have been guided by well-established reports and declarations such as the Belmont Report and the Declaration of Helsinki [ 4 – 6 ]. At the core of these documents are three fundamental principles– respect for persons , beneficence , and justice –and their related interpretations and practices, such as the acknowledgment of participants’ autonomous participation and the need to obtain informed consent, minimization of harm, risk benefit assessment, fairness in distribution and dissemination of research outcomes, and fair participant selection (e.g. to avoid additional burden to vulnerable populations) [ 7 ].

As data stemming from human interactions is more and more available to scholars, thanks to a) the increased distribution of technological devices, b) the growing use of digital services, and c) the implementation of new digital technologies [ 8 , 9 ], researchers and institutional bodies are confronted with novel ethical questions. These encompass harm, that might be caused by the linkage of publicly available datasets on research participants [ 10 ], the level of privacy users expect in digital platforms such as social media [ 11 ], the level of protection that investigators should ensure for the anonymity of their participants in research using sensing devices and tracking technologies [ 12 ], and the role of individuals in consenting in participating in large scale data studies [ 13 ].

Consent is one of the most challenged practices in data research. In this context subjects are often unaware of the fact that their data is collected and analyzed and lack the appropriate control over their data, preventing them the possibility to withdraw from a study, that allows for autonomous participation [ 14 , 15 ]. When it comes to the principle of beneficence , Big Data brings about issues with regard to the appropriate risk-benefit ratio for participants as it becomes more difficult for researchers to anticipate unintended harmful consequences [ 8 ]. For example, it is increasingly complicated to ensure anonymity of the participant as risks of re-identification abound in Big Data practices [ 12 ]. Finally, interventions and knowledge developed from Big Data research might benefit only part of the population thus creating issues of justice and fairness [ 10 ]; this is mainly due to the deepening of the digital divide between people who have access to digital resources and those who do not, on the basis of a significant number of demographic variables such as income, ethnicity, age, skills, geographical location and gender [ 10 , 16 ].

There is evidence that researchers and regulatory bodies are struggling to appropriately address these novel ethical questions raised by Big Data. For instance, a group of researchers based at Queen’s Mary University in the UK used a model of geographic profiling on a series of publicly available datasets in order to reveal the identity of famous British artist Banksy [ 17 ]. The study was criticized by scholars for being disrespectful of the privacy of a private citizen and their family and a deliberate violation of the artist’s right of and preference for remaining anonymous [ 18 ]. Another example is the now infamous case of the Emotional Contagion study. Using a specific software, a research team manipulated the News Feeds of 689,003 Facebook users in order investigate how “emotional states can be transferred to others via emotional contagion, leading people to experience the same emotions without their awareness” [ 19 ]. Ethics scholars and the public criticized this study because it was performed without obtaining the appropriate consent from Facebook users and it could have cause psychological harm by showing participants only negative feeds on their homepage [ 20 , 21 ].

Given these substantial challenges, it is legitimate to ask whether the principles set by the Belmont Report are still relevant for digital research practices. Scholars advocate for the construction of flexible guidelines and for the need to revise, reshape and update the guiding principles of research ethics in order to overcome the challenges raised in data research and provide adequate assistance to investigators [ 22 – 24 ].

As ethics governance of Big Data research is currently at debate, researchers’ own ethical attitudes influence significantly how ethical issues are presently dealt with. As researchers are experts on the technical details of their own research, it is also useful for research ethicists and members of ethical committees and Institutional Review Boards (IRB) to be knowledgeable of these attitudes. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the code of ethics and research practices of behavioral scientists involved in Big Data studies in the behavioral sciences in order to investigate perceived strategies to promote ethical and responsible conduct of Big Data research. We have conducted interviews with researchers in the fields of sociology and psychology from eminent universities both in Switzerland and the United States, where we asked them to share details about the type of strategies they develop to protect research participants in their projects; what ethical principles they apply to their projects; their opinion on how Big Data research should ideally be conducted and what ethical challenges they have faced in their research. The present study aims to contribute to the existing literature on the code of conduct of researchers involved in digital research in different countries and the value of traditional ethical principles [ 14 , 22 , 23 ] in order to contribute to the discussion around the construction of harmonized and applicable principles for Big Data studies. This manuscript aims at investigating the following research questions: 1) what are the ethical principles that can still be considered relevant for Big Data research in the behavioral sciences; 2) what are the challenges that Big data methods are posing to traditional ethical principles; 3) what are the investigators’ responsibilities and roles in reflecting upon strategies to protect research participants.

Material and methods

This study is part of a larger research project that investigated the ethical and regulatory challenges of Big Data research. We decided to focus on behavioral sciences, specifically phycology and sociology, for two main reasons. First, the larger research project aimed at investigating the challenges introduced by Big Data methods for regulatory bodies such as Research Ethics Committees (RECs) and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) [ 25 ]. Both in Switzerland and the United States, Big Data research methods in these two fields are questioning the concept of human research subject–due to the increased distance and detachment between research subjects and investigators brought by digitalized means for data collection (e.g. social media profiles, data networks, transaction logs etc.) and analysis [ 18 ]. As a consequence current legislation in charge of regulating academic research, such as the Human Research Act (HRA) [ 26 ], the Federal Act of Data Protection [ 27 ] and the Common Rule [ 18 ], is being increasingly challenged. Second, especially in Switzerland, behavioral studies using Big Data methods are at the moment among the most underregulated types of research projects [ 26 , 28 , 29 ]. In fact, the current definition of human subject leaves many Big Data projects out of the scope of regulatory overview despite the possible ethical challenges they pose. For instance, according to the HRA research that involves anonymized data from research participants does not need ethics approval [ 26 ].

In addition, we selected Switzerland and the United States to recruit participants: Switzerland, where Big Data research is a quite recent phenomenon, was chosen because the study was designed, funded and conducted there. The United States were selected as a as a comparative sample, where advanced Big Data research has been taking place for several years in the academic environment, as evidenced by the numerous grants placed for Big Data research projects by federal institutions, such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) [ 30 , 31 ] and the National Institute of Health (NIH) [ 32 ].

For the purpose of our study we defined Big Data as an overarching umbrella term that designates a set of advanced digital techniques (e.g. data mining, neural networks, deep learning, artificial intelligence, natural language processing, profiling, scoring systems) that are increasingly used in research to analyze large datasets with the aim of revealing patterns, trends and associations about individuals, groups and society in general [ 33 ]. Within this definition we selected participants that conducted heterogeneous Big Data research projects: from internet-based research and social media studies, to aggregate analysis of corporate datasets, to behavioral research using sensing devices. Participant selection was based on their involvement in Big Data research and was conducted systematically by browsing the professional pages of all professors affiliated to the departments of psychology and sociology of all twelve Swiss Universities and the top ten American Universities according to the Times Higher Education University Ranking 2018. Other candidates were identified through snowballing. Through our systematic selection we also identified a consistent number of researchers with a background in data science that were involved in research projects in behavioral sciences (in sociology, psychology and similar fields) during the time of their interview. Since their profile matched the selection criteria, we included them in our sample.

We conducted 39 semi structured interviews with academic scholars involved in research projects that adopt Big Data methodologies. Twenty participants were from Swiss universities and 29 came from American institutions. They comprised of a majority of professors (n = 34) and a few senior researchers or postdocs (n = 5). Ethics approval was sought from the Ethics Committee northwest/central Switzerland (EKNZ) who deemed our study exempt. Oral informed consent was sought prior the start of each interview. Interviews were administered using a semi-structured interview guide developed, through consensus and discussion, after the research team had the time to familiarize with the literature and studies on Big Data research and data ethics. The questions explored topics like: ethical issues related to Big Data studies in the behavioral sciences; ethics of conduct with regards to Big Data research project; institutional regulatory practices; definition and understanding of the term Big Data; and opinions towards data driven studies ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241865.t001

Interviews were tape recorded and transcribed ad-verbatim. We subsequently transferred the transcripts into the qualitative software MAXQDA (version 2018) to support with data management and the analytic process [ 34 ]. Analysis of the dataset was done using thematic analysis [ 35 ]. The first four interviews were independently read and coded by two members of the research team in order to explore the thematic elements of the interviews. To ensure consistency during the analysis process, the two researchers subsequently confronted the preliminary open-ended coding and they developed an expanded coding scheme that was used for all of the remaining transcripts. Several themes relevant for this study were agreed upon during the coding sessions such as: a) responsibility and the role of the researcher in Big Data research; b) research standards for Big Data studies; c) attitudes towards the use of publicly available data; d) emerging ethical issues from Big Data studies. Since part of the data has already been published, we refer to a previous publication [ 33 ] for additional information on methodology, project design, data collection and data analysis.

Researcher’s code of ethics for Big Data studies was chosen as a topic to explore since participants, by identifying several ethical challenges related to Big Data, expressed concerns regarding the protection of the human subject in digital research and expressed shared strategies and opinions on how to ethically conduct Big Data studies. Consequently, all the interviews that were coded within the aforementioned topics were read again, analyzed and sorted into sub-topics. This phase was performed by the first author while the second author supervised this phase by checking for consistency and accuracy.

For this study we conducted 39 interviews with respectively 21 sociologists (9 from CH and 12 from the US), 11 psychologists (6 from CH and 5 from the US), and 7 data scientists (5 from CH and 2 from the US). Among them, 27 scholars (12 from CH and 21 from US) stated that they were working on Big Data research projects or on projects that involve Big Data methodologies, four participants (all from CH) noted that they were not involved in Big Data research and eight (7 from CH and one from the US) were unsure whether their research could be described or considered as Big Data research ( Table 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241865.t002

Respondents, while discussing codes of ethics and ethical practices for Big Data research, both a) shared their personal strategies that they implemented in their own research projects to protect research subjects, and b) generally discussed the appropriate research practices to be implemented in Big Data research. Table 3 illustrates the type of Big Data our participants were working with at the time of the interview.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241865.t003

Our analysis identified several themes and subthemes. They were then divided and analyzed within three major thematic clusters: a) ethical principles for Big Data research; b) challenges that Big Data is introducing for research principles; c) ethical reflection and responsibility in research. Table 4 reports the themes and subthemes that emerged from the interviews and their occurrence in the dataset. Representative anonymized quotes were taken from the interviews to further illustrate the reported results.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241865.t004

Ethical principles for digital research

Belmont principles, beneficence and avoiding harm..

First, many of the respondents shared their opinions on what ethical guidelines and principles they consider important to conduct ethical research in the digital era. Table 5 illustrates the number of researchers that mentioned a specific ethical principle or research practice as relevant for Big Data research.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241865.t005

Three of our participants, generally referred to the principles stated in the Belmont Report and the ones related to the Declaration of Helsinki.

I think the Belmont Report principles. The starting point so. . . .you know beneficence, respect for the individuals, justice… and applying those and they would take some work for how to apply those exactly or what it would mean translating to this context but that would be the starting point (P18, US–data science).

A common concern was minimization of harm for research participants and the importance of beneficence as prominent components of scholarly research.

And…on an ethical point of view… and I guess we should be careful that experiment doesn’t harm people or not offend people for example if it's about religion or something like that it can be tricky (P25, CH–psychology).

Beneficence, in the context of digital Big Data research, was sometimes associated with the possibility of giving back to the community as a sort of tradeoff for the inconvenience that research might cause to research participants. On this, P9, an American sociologist, shared:

I mean it's interesting that the ethical challenges that I faced… (pause) had more to do with whether I feel, for instance in working in the developing world…is it really beneficial to the people that I'm working with, I mean what I'm doing. You know I make heavy demands on these people so one of the ethical challenges that I face is, am I giving back enough to the community.

While another American scholar, a psychologist, was concerned about how to define acceptable risks in digital research and finding the right balance between benefit and risks for research projects.

P17: Expecting benefit from a study that should outweigh the respective risks. I mean, I think that's a pretty clear one. This is something I definitely I don't know the answer to and I'm curious about how much other people have thought about it. Because like what is an acceptable sort of variation in expected benefits and risks. Like, you could potentially say “on average my study is expected to deliver higher benefits than risks”… there's an open question of like, … some individuals might regardless suffer under your research or be hurt. Even if some others are benefitting in some sense.

For two researchers, respect for the participant and their personhood was deemed particularly important irrespective of the type of research conducted. P19, an American sociologist, commented:

What I would like to see is integrity and personhood of every single individual who is researched, whether they are dead or alive, that that be respected in a very fundamental way. And that is the case whether it's Big Data, and whether is interviews, archival, ethnographic, textual or what have you. And I think this is a permanent really deep tension in wissenshaftlich ( scientific research ) activities because we are treating the people as data. And that's a fundamental tension. And I think it would be deeply important to explicitly sanitize that tension from the get-go and to hang on to that personhood and the respect for that personhood.

Informed consent and transparency.

Consent was by far the most prominent practice that emerged from the interviews as three quarters of our participants mentioned it, equally distributed among American and Swiss researchers. Numerous scholars emphasized how informed consent is at the foundation of appropriate research practices. P2, a Swiss psychologist, noted:

But of course it's pretty clear to me informed consent is very important and it’s crucial that people know what it is what kind of data is collected and when they would have the possibility of saying no and so on. I think that’s pretty standard for any type of data. (…) I mean it all goes down to informed consent.

For a few of our participants, in the era of Big Data, it becomes not really a matter of consent but a matter of awareness. Since research with Big Data could theoretically be performed without the knowledge of the participant, research subjects at least have to be made aware that they are part of a research project as claimed by P38 a Swiss sociologist who said:

I think that everything comes down to the awareness of the subject about what is collected about them. I mean, we have collected data for ages, right? And I mean, before it was using pen and paper questionnaires, phone interviews or…there’s been data collection about private life of people for, I mean, since social science exists. So, I think the only difference now is the awareness.

Another practice that was considered fundamental by our participants was the right of participants to withdraw from a research study that, in turn, was translated in giving the participants more control over their data in the context of Big Data research. For example, while describing their study with social media, a Swiss sociologist (P38) explained that”the condition was that everybody who participated was actually able to look at his own data and decide to drop from the survey any time”. Another Swiss sociologist (P37), when describing a study design in which they asked participants to install an add-on on their browser to collect data on their Facebook interactions, underlined the importance of giving participants control over their data and to teach them how to manage them, in order to create a trust based exchange between them and the investigators:

And there you'd have to be sure that people…it's not just anonymizing them, people also need to have a control over their data, that's kind of very important because you need kind of an established trust between the research and its subjects as it were. So they would have the opportunity of uninstall the…if they're willing to take part, that's kind of the first step, and they would need to download that add-on and they'd also be instructed on how to uninstall the add-on at any point in time. They'd be also instructed on how to pause the gathering of their data at any point in time and then again also delete data that well…at first I thought it was a great study now I'm not so sure about, I want to delete everything I've ever collected.

The same researcher suggested to create regulations that ensure ownership of research data to participants in order to allow them to have actual power over their participation past the point of initial consent.

And legal parameters then should be constructed as such that it has to be transparent, that it guards the rights of the individual (…) in terms of having ownership of their data. Particularly if it's private data they agree to give away. And they become part of a research process that only ends where their say. And they can always withdraw the data at any point in time and not just at the beginning with agreeing or not agreeing to taking part in that. But also at different other points in time. So that i think the…you have to include them more throughout your research process. Which is more of a hassle, costs more money and more time, but in the end you kind of. . . .it makes it more transparent and perhaps it makes it more interesting for them as well and that would have kind of beneficial effects for the larger public I suppose.

In addition, transparency of motives and practices was also considered a fundamental principle for digital research. For instance, transparency was seen as a way for research participants to be fully informed about the research procedures and methods used by investigators. According to a few participants transparency is key to guarantee people’s trust the research system and to minimize their worry and reservations about participating in research studies. On this P14, an American psychologist, noted:

I think we need to have greater transparency and more. . . . You know our system, we have in the United States is that…well not a crisis, the problem that we face in the United States which you also face I'm sure, is that…you know, people have to believe that this is good stuff to do (participating in a study). And if they don't believe that this is good stuff to do then it's a problem. And so. . . .so I think that that. . . .and I think that the consent process is part of it but I think that the other part of it is that the investigators and the researchers, the investigators and the institutions, you know, need to be more transparent and more accountable and make the case that this is something worth doing and that they're being responsible about it.

A Swiss sociologist, P38, who described how they implemented transparency in their research project by giving control to participants over the data they were collecting on them, highlighted that the fear individuals might have towards digital and Big Data research might come from lack of information and understanding about what data investigators are collecting on them and how they are using it. In this sense transparency of practices not only ensures that more individuals trust the research systems, but it will also assist them in making a truly informed decision about their participation in a study.

And if I remember correctly the conditions were: transparency, so every subject had to have access to the full data that we were collecting. They had also the possibility to erase everything if they wanted to and to drop from the campaign. I guess it's about transparency. (…) So, I think this is key, so you need to be transparent about what kind of data you collect and why and maybe what will happen to the data. Because people are afraid of things they don't understand so the better they understand what's happening the more they would be actually. . . . not only they will be willing to participate but also the more they will put the line in the right place. So, this I agree, this I don't agree. But the less you understand the further away you put the line and you just want to be on the safe side. So, the better they understand the better they can draw the line at the right place, and say ok: this is not your business, this I'm willing to share with you.

In addition, one of our participants considered transparency to be an important value also between scholars from different research teams. According to this participant, open and transparent communication and exchange between research would help implement appropriate ethical norms for digital research. They shared:

But I think part of it is just having more transparency among researchers themselves. I think you need to have like more discussions like: here's what I'm doing…here's what I'm doing…just more sharing in general, I think, and more discussion. (…) People being more transparent on how they're doing their work would just create more norms around it. Because I think in many cases people don't know what other people have been doing. And that's part of the issues that, you know, it's like how do I apply these abstract standards to this case, I mean that can be though. But if you know what everybody is doing it makes a little bit easier. (P3-US, Sociologist)

On the other hand, however, a sociologist from Switzerland (P37), noted that the drive towards research transparency might become problematic for ensuring the anonymity of research participants as more information you share about research practices and methods the more possibilities of backtracking and re-identifying the participants to the study.

It’s problematic also because modern social science, or science anyway, has a strong and very good drive towards transparency. But transparency also means, that the more we become transparent the less we can guarantee anonymity (…) If you say: "well, we did a crawl study", people will ask "well, where are you starting, what are your seeds for the crawler?". And it's important to, you know, to be transparent in that respect.

Privacy and anonymity.

Respect for the privacy of research participants, and protection from possible identification, usually achieved through anonymization of data, were the second most mentioned standards to be considered while conducting Big Data research. P33, a Swiss sociologist, underlined how “If ever, then privacy has…like it’s never been more important than now”, since information about individuals is becoming increasingly available thanks to digital technologies, and how institutions now have a responsibility to ensure that such privacy is respected. A Swiss data scientist, P29, described the privacy aspect embedded in their research with social media and how their team is constantly developing strategies to ensure anonymity of research subjects. They told:

Yeah, there is a privacy aspect of course, that's the main concern, that you basically…if you’re able to reconstruct like the name of the person and then the age of the person, the address of the person, of course you can link it then to the partner of the person, right? If she or he has, they're sharing the same address. And then you can easily create the story out of that, right? And then this could be an issue but…again, like we try to reapply some kind of anonymization techniques. We have some people working mostly on that. There is a postdoc in our group who is working on anonymization techniques.

Similarly, an American researcher, P6 Sociologist, underlined how it should become a routine practice for every research project to consider and implement practices to protect human participants from possible re-identification:

In the social science world people have to be at least sensitive to the fact that they could be collecting data that allows for the deductive identification of individuals. And that probably…that should be a key focus of every proposal of how do you protect against that.

Challenges introduced by Big Data to research ethics and ethical principles

A consistent number of our researcher, on the other hand, recognized how Big Data research and methods are introducing numerous challenges related to the principles and practices they consider fundamental for ethical research and reflected upon the limits of the traditional ethical principles.

When discussing informed consent, participants noted that that it might not be the main standard to refer to when creating ethical frameworks for research practices as it cannot be ensured anymore in much digital research. For instance, P14, an American psychologist noted:

I think that that the kind of informed consent that we, you know, when we sign on to Facebook or Reddit or Twitter or whatever, you know, people have no idea of what that means and they don't have any idea of what they're agreeing to. And so, you know the idea that that can bear the entire weight of all this research is, I think…I think notification is really important, you can ask for consent but the idea that that can bear the whole weight for allowing people to do whatever/ researchers to do whatever they want, I think it's misguided.

Similarly, P18, an American scholar with a background in data science, felt that although there is still a place for informed consent in the digital era, this practice should be appropriately revisited and reconsidered as it cannot be applied anymore in the stricter sense, for instance when analyzing aggregated databases where personal identifiers are removed and it would be impossible to trace back the individual to ask them for consent. Data aggregation is the process of gathering data from multiple sources and presenting it in a summarized format. Through the process of data aggregation, data can be stripped from personal identifiers thus ensuring anonymization of the dataset and analyzing aggregate data should, theoretically not reveal personal information about the user. The participant shared:

Certainly, I think there is [space for informed consent in digital research]. And like I said I think we should require people to have informed consent about their data being used in aggregate analysis. And I think right now we do not have informed consent. (…) So, I think again, under the strictest interpretation even to consent to have one’s data involved in an aggregate analysis should involve that. But I don't know, short of that, what would be an acceptable tradeoff or level of treatment. Whether simply aggregating the analysis is good enough and if so what level of aggregation is necessary.

As for consent, many of our participants while recognizing the importance of privacy and anonymity, also reflected on some of the challenges that Big Data and digitalization of research are creating for these research standards. First, a few respondents highlighted how in digital research the risk of identification of participants is quite high as anonymized datasets could almost always be de-anonymized, especially if data is not adequately secured. On this, P1, an American sociologist explained:

I understand and recognize that there are limits to anonymization. And that under certain circumstances almost every anonymized dataset can be de-anonymized. That's what the research that shows us. I mean sometimes that requires significant effort and then you ask yourself would someone really invest like, you know, supercomputers to solve this problem to de-anonymize…

A Swiss sociologist (P38) described how anonymization practices towards the protection of the privacy of the research participant could, on the other hand, diminish the value of the data for research as anonymization would destroy some of the information the researcher is actually interested in.

You know, we cannot do much about it. So… there is a tendency now to anonymize the data but basically ehm…anonymization means destruction of information in the data. And sometimes the information that is destroyed is really the information we need…

Moreover, it was also claimed how digital practices in research are currently blurring the line between private and public spaces creating additional challenges for the protection of the privacy of the research participant and practices of informed consent. A few of our researchers highlighted how research subjects might have an expectation of privacy even in public digital spaces such as social media and public records. In this context, an American sociologist, P9, noted how participants could have a problem in allowing researchers to link together publicly available datasets as they would prefer information stemming from this linkage to remain private:

P9USR: Well because the question is…even if you have no expectation of privacy in your Twitter account, you know Twitter is public. And even if you have no expectation of privacy in terms of whether you voted or not, I don't know, in Italy maybe it's a public record whether if you show up at the pool or not. Right? I can go to the city government and see who voted in the last elections right? (…) So…who voted is listed or what political party they're member of is listed, is public information. But you might have expectation of privacy when it comes to linking those data. So even though you don't expect privacy in Twitter and you don't expect privacy in your voting records, maybe you don't like it when someone links those things together.

In addition, a sociologist, P19 from the US, noted how even with just linking information of some publicly available data, research subjects could be easily identified.

However, when one goes to the trouble of linking up some of the aspects of these publicly available sets it may make some individuals identifiable in a way that they haven't been before. Even though one is purely using publicly available data. So, you might say that it kind of falls into an intermediate zone. And raises practical and ethical questions on protection when working with publicly available data. I don't know how many other people you have interviewed who are working in this particular grey zone.

Two of our participants while describing personal strategies to handle matters of expectation of privacy and consent, discussed the increased blur between private and public spaces and how it is becoming increasingly contextual to adequately handle matters of privacy on social media.

P2USR: So, for example when I study journalists, I assume that their Tweets are public data just because Twitter is the main platform for journalists to kind of present their public and professional accomplishments and so I feel fine kind of using their tweets, like in the context of my research. I will say the same thing, about Facebook data for example. So, some of the journalists kind of… that I interviewed are… are not on Facebook anymore, but at the time we became friends on Facebook and there were postings and I… I wouldn't feel as comfortable, I wouldn't use their Facebook data. I just think that somehow besides the norms of the Facebook platform is that it's more private data, from…especially when it's not a public page so… But it's like… it's fuzzy.

Responsibility and ethical reflection in research

Due to the challenges introduced by digital methods, some of our participants elaborated on their opinions regarding the role of ethical reflection and their responsibility in addressing such challenges in order to ensure the protection of research participants.

Among them, some researches emphasized the importance for investigators to apply ethical standards to appropriately perform their research projects. However, a couple of them recognized how not all researchers might have the background and expertise to acknowledge the ethical issues stemming from their research projects or to be adequately familiar with ethical frameworks. On this, P12, an American sociologist, highlighted the importance of education in ethics for research practitioners:

I also want to re-emphasize that I think that as researchers in this field we need to have training in ethics because a lot of the work that we're doing (pause) you know can be on the border of infringing on people’s privacy.

In addition, self-reflection, ethical interrogation and evaluation about the appropriateness of certain research practices was a theme that emerged quite often during our interviews. For an American psychologist, P4, concerned about issues of consent in digital research, it is paramount that investigator begin to interrogate themselves upon what type of analysis would be ethically appropriate without explicit consent of participants.

And it is interesting by the way around Big Data because in many cases those data were generated by people who didn't sign any consent form. And they have their data used for research. Even (for the) secondary analysis of our own data the question is: what can you do without consent?

Similarly, P26, a sociologist from Switzerland, reflected upon the difficulties that researchers might encounter in evaluating what type of data investigators can consider unproblematic to collect and analyze even in digital public spaces, like social media:

Even though again, it's often not as clear cut, but I think if people make information public that is slightly different from when you are posting privately within a network and assume that the only people really seeing that are your friends. I see that this has its own limits as well because certain things…well A: something like a profile image I think is always by default public on Facebook…so… there you don't really have a choice to post it privately. I guess your only choice is not to change it ever. And then the other thing is that…I know it because I study (…) internet skills, I know a lot of people are not very skilled. So, there are a lot of instances where people don't realize they're posting publicly. So even if something is public you can't assume people had meant it to be public.

Moreover, reflection and evaluation of the intent behind a research study was considered important by P31, a Swiss data scientist, for ethical research in Big Data. The researcher recognized that this is difficult to put into practice as investigators with ill intent might lie about their motivations and you could have negative consequences even with the noblest of intents.

I find it really difficult to answer that. I would say, the first thing that comes to my mind is the evaluation of intent… rather than other technicality. And I think that's a lacking point. But also the reason why I don't give that answer immediately is like…intent is really difficult to probe… and it's probably for some people quite easy to know what is the accepted intent. And then I can of course give you a story that is quite acceptable to you. And also with good intent you can do evil things. So, it's difficult but I would say that discussion about the intent is very important. So that would be maybe for me a minimal requirement. At least in the discussions.

In this context, some scholars also discussed their perception regarding responsibility of protecting research participants in digital studies and the role investigators play in overcoming ethical issues.

For a few of them it was clear that the responsibility of protecting the data subjects should fall on the investigators themselves. For instance, an American scholar, P22 sociologist, while discussing the importance of creating an ethical framework for digital research that uses publicly available data of citizens shared:

So, I do think (the responsibility) it's on researchers (…) and I get frustrated sometimes when people say "well it's not up to us, if they post it there then it's public". It's like well it is up to us, it's literally our job, we do it all day, try to decide, you know, what people want known about them and what people don't. So, we should apply those same metrics here.

However, other researchers also pointed out how the introduction of digital technologies and digital methods for behavioral research is currently shifting the perceived responsibility scholars have. P16, an American sociologist, shared some concerns regarding the use of sensor devices for behavioral research and reflected on how much responsibility they, as investigators, have in assuring data protection of their research subjects since the data they work with is owned by the company that provided the device for data collection:

There's still seems to be this question about…whether. . . .what the Fitbit corporation is doing with those data and whether we as researchers should be concerned about that. We're asking people to wear Fitbits for a study. Or whether that's just a separate issue. And I don't know what the answer to that is, I just know that it seems like the type of question that it's going to come up over and over and over again.

One a similar note, P14, an American psychologist, noted that while researchers actually have a responsibility of preventing harm that might derive from data research, it should be a responsibility in part shared with data holders. They claimed:

Do I think that the holders of data have a responsibility to try to you know, try to prevent misuse of data? Yeah, I think they probably do. (…) I think there is a notion of stewardship there. Then I think that investigators also have an independent obligation to make sure to think about the data they're analyzing and trying to get and think about what they're using it for. So not to use data in order to harm other people or those kinds of things.

Finally, a few participants hinted at the fact that research ethics boards like Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and Ethics Committees (ECs) should play a bigger role of responsibility in ensuring that investigators actually perform their research ethically. For instance, P16, an American sociologist, complained that IRBs do not provide adequate follow-up to researchers to ensure that they are appropriately following the approved research protocols.

There does seem to be kind of a big gap even in the existing system. Which is that a researcher proposes a project, the IRB hopefully works with the researcher and the project gets approved and there's very little follow-up and very little support for sort of making sure that the things that are laid out at the IRB actually in the proposal and the project protocol actually happen. And not that I don't believe that most researchers have good intensions to follow the rules and all of that but there are so many of kind of different projects and different pressures that things can slip by and there's… there's nobody.

As Big Data methodologies are becoming widespread in research, it is important to reach international consensus on whether and how traditional principles for research ethics, such as the ones described in the Belmont Report, are still relevant for the new ethical questions introduced by Big Data and internet research [ 22 , 23 ]. Our study offers a relevant contribution to this debate as it investigated the methodological strategies and code of ethics researchers from different jurisdictions—Swiss and American investigators—apply in their Big Data research projects. It is interesting to notice how, despite regional difference, participants shared very similar ethical priorities. This might be due to the international nature of academic research, where scholars share similar codes of ethics and apply similar strategies for the protection of research participants.

Our results point out that in their code of conduct, researchers mainly referred to the traditional ethical principles enshrined in the Belmont report and the Declaration of Helsinki, like respect for persons in the practice of informed consent, beneficence, minimization of harm through protection of privacy and anonymization, and justice. This finding shows that such principles are still considered relevant in behavioral sciences to address the ethical issues of Big Data research, despite the critique of some that rules designed for medical research cannot be applied in sociological research [ 36 ]. Even before the advent of Big Data, the practical implementation of the Belmont Report principles has never been an easy endeavor as they were originally conceived to be flexible to accommodate a wide range of different research settings and methods. However it has been argued that exactly this flexibility makes them the perfect framework in which investigators can “clarify trade-offs, suggest improvements to research designs, and enable researchers to explain their reasoning to each other and the public” in digital behavioral research [ 2 ].

Our study shows how scholars still place great importance on the practice of informed consent. They considered crucial that participants are appropriately notified of their research participation, are adequately informed about at least some of the details and procedures of the study, and are given the possibility to withdraw at any point in time. A recent study, however, has highlighted that there is currently no consensus among investigators on how to collect meaningful informed consent among participants in digital research [ 37 ]. Similarly, a few researchers from our study recognized that consent, although preferable in theory, might not be the most adequate practice to refer to when designing ethical frameworks. In the era of Big Data behavioral research, informed consent becomes an extremely complex practice that is intrinsically dependent on the context of the study and the type of Big Data used. For instance, in certain behavioral studies that analyze track data from devices related to a limited number of participants, it would be feasible to ask for consent prior to beginning of the study. However, recombination and reanalysis of the data, possibly across ecosystems far removed from the original source of the data, makes it very difficult to fully inform participants about the range of uses to which their data would be put through, the type of information that could emerge from the analysis of the data, and the unforeseeable harms that the disclosure of such information could cause [ 38 ]. In online studies and internet-mediated research, consent often amounts to an agreement to unread terms of service or a vague privacy policy provided by digital platforms [ 18 ]. Sometimes valid informed consent is not even required by official guidelines when the analyzed data can be considered ‘in the public domain’ [ 39 ], leaving participants unaware that research is performed on their data. It has been argued however that researchers should not just assume that public information is freely accessible for collection and research just because it is public. Researchers should take into consideration what the subject might have intended or desired regarding the possibility for their data to be used for research purposes [ 40 ]. At the same level, we can also argue that even when information is harvested with consent, the subject might a) not wish for their data to be analyzed or reused outside of the purview of the original research purpose and b) fail to understand what is the extent of the information that the analysis of the dataset might reveal about them.

Matzner and Ochs argue that practices of informed consent “are widely accepted since they cohere with notions of the individual that we have been trained to adopt for several centuries” [ 41 ], however they also emphasize how such notions are being altered and challenged by the openness and transience of data-analytics that prevent us from continuing to consider the subject and the researcher within a self-contained dynamic. Since respect for persons , in the form of informed consent, is just one of the principles that needs to be balanced when considering research ethics [ 42 ], it becomes of outmost importance to find the right balance between the perceived necessity of still ensuring consent from participants and the reality that such consent is sometimes impossible to obtain properly. Salganik [ 2 ], for instance, suggests that in the context of digital behavioral research rather than “informed consent for everything”, researchers should follow a more complex rule: “some form of consent for most things”. This means that, assuming informed consent is required, it should be evaluated on a case by case basis whether consent is a) practically feasible and b) actually necessary. This practice might however leave too much space to the discretion of the investigator who might not have the skills to appropriately evaluate the ethical facets of their research projects [ 43 ].

Next to consent, participants from our study also argued in favor of ensuring more control to participants over their own data. In the past years, in fact, it has been argued that individuals often lack the control to manage, protect and delete their data [ 20 , 28 ]. Strategies of dynamic consent could be considered a potential tool to address ethical issues related to consent in Big Data behavioral research. Dynamic consent, a model where online tools are developed to have individuals engage in decisions about how their personal information should be used and which allows them some degree of control over the use of their data, are currently mainly developed for biomedical Big Data research [ 44 , 45 ]. Additional research could be performed to investigate if such models can be translated and applied also for behavioral digital research.