- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Educational Psychology?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

- Major Perspectives

- Topics of Study

Frequently Asked Questions

Educational psychology is the study of how people learn , including teaching methods, instructional processes, and individual differences in learning. It explores the cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social influences on the learning process. Educational psychologists use this understanding of how people learn to develop instructional strategies and help students succeed in school.

This branch of psychology focuses on the learning process of early childhood and adolescence. However, it also explores the social, emotional, and cognitive processes that are involved in learning throughout the entire lifespan.

The field of educational psychology incorporates a number of other disciplines, including developmental psychology , behavioral psychology , and cognitive psychology . Approaches to educational psychology include behavioral, developmental, cognitive, constructivist, and experiential perspectives.

This article discusses some of the different perspectives taken within the field of educational psychology, topics that educational psychologists study, and career options in this field.

8 Things to Know About Educational Psychology

Perspectives in educational psychology.

As with other areas of psychology, researchers within educational psychology tend to take on different perspectives when considering a problem. These perspectives focus on specific factors that influence learning, including learned behaviors, cognition, experiences, and more.

The Behavioral Perspective

This perspective suggests that all behaviors are learned through conditioning. Psychologists who take this perspective rely firmly on the principles of operant conditioning to explain how learning happens.

For example, teachers might reward learning by giving students tokens that can be exchanged for desirable items such as candy or toys. The behavioral perspective operates on the theory that students will learn when rewarded for "good" behavior and punished for "bad" behavior.

While such methods can be useful in some cases, the behavioral approach has been criticized for failing to account for attitudes , emotions, and intrinsic motivations for learning.

The Developmental Perspective

This perspective focuses on how children acquire new skills and knowledge as they develop. Jean Piaget's stages of cognitive development is one example of an important developmental theory looking at how children grow intellectually.

By understanding how children think at different stages of development, educational psychologists can better understand what children are capable of at each point of their growth. This can help educators create instructional methods and materials aimed at certain age groups.

The Cognitive Perspective

The cognitive approach has become much more widespread, mainly because it accounts for how factors such as memories, beliefs, emotions , and motivations contribute to the learning process. This theory supports the idea that a person learns as a result of their own motivation, not as a result of external rewards.

Cognitive psychology aims to understand how people think, learn, remember, and process information.

Educational psychologists who take a cognitive perspective are interested in understanding how kids become motivated to learn, how they remember the things that they learn, and how they solve problems, among other topics.

The Constructivist Approach

This perspective focuses on how we actively construct our knowledge of the world. Constructivism accounts for the social and cultural influences that affect how we learn.

Those who take the constructivist approach believe that what a person already knows is the biggest influence on how they learn new information. This means that new knowledge can only be added on to and understood in terms of existing knowledge.

This perspective is heavily influenced by the work of psychologist Lev Vygotsky , who proposed ideas such as the zone of proximal development and instructional scaffolding.

Experiential Perspective

This perspective emphasizes that a person's own life experiences influence how they understand new information. This method is similar to constructivist and cognitive perspectives in that it takes into consideration the experiences, thoughts, and feelings of the learner.

This method allows someone to find personal meaning in what they learn instead of feeling that the information doesn't apply to them.

Different perspectives on human behavior can be useful when looking at topics within the field of educational psychology. Some of these include the behavioral perspective, the constructivist approach, and the experiential perspective.

Topics in Educational Psychology

From the materials teachers use to the individual needs of students, educational psychologists delve deep to more fully understand the learning process. Some these topics of study in educational psychology include:

- Educational technology : Looking at how different types of technology can help students learn

- Instructional design : Designing effective learning materials

- Special education : Helping students who may need specialized instruction

- Curriculum development : Creating coursework that will maximize learning

- Organizational learning : Studying how people learn in organizational settings, such as workplaces

- Gifted learners : Helping students who are identified as gifted learners

Careers in Educational Psychology

Educational psychologists work with educators, administrators, teachers, and students to analyze how to help people learn best. This often involves finding ways to identify students who may need extra help, developing programs for students who are struggling, and even creating new learning methods .

Many educational psychologists work with schools directly. Some are teachers or professors, while others work with teachers to try out new learning methods for their students and develop new course curricula. An educational psychologist may even become a counselor, helping students cope with learning barriers directly.

Other educational psychologists work in research. For instance, they might work for a government organization such as the U.S. Department of Education, influencing decisions about the best ways for kids to learn in schools across the nation.

In addition, an educational psychologist work in school or university administration. In all of these roles, they can influence educational methods and help students learn in a way that best suits them.

A bachelor's degree and master's degree are usually required for careers in this field; if you want to work at a university or in school administration, you may need to complete a doctorate as well.

Educational psychologists often work in school to help students and teachers improve the learning experience. Other professionals in this field work in research to investigate the learning process and to evaluate programs designed to foster learning.

History of Educational Psychology

Educational psychology is a relatively young subfield that has experienced a tremendous amount of growth. Psychology did not emerge as a separate science until the late 1800s, so earlier interest in educational psychology was largely fueled by educational philosophers.

Many regard philosopher Johann Herbart as the father of educational psychology.

Herbart believed that a student's interest in a topic had a tremendous influence on the learning outcome. He believed teachers should consider this when deciding which type of instruction is most appropriate.

Later, psychologist and philosopher William James made significant contributions to the field. His seminal 1899 text "Talks to Teachers on Psychology" is considered the first textbook on educational psychology.

Around this same period, French psychologist Alfred Binet was developing his famous IQ tests. The tests were originally designed to help the French government identify children who had developmental delays and create special education programs.

In the United States, John Dewey had a significant influence on education. Dewey's ideas were progressive; he believed schools should focus on students rather than on subjects. He advocated active learning, arguing that hands-on experience was an important part of the process.

More recently, educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom developed an important taxonomy designed to categorize and describe different educational objectives. The three top-level domains he described were cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning objectives.

Significant Figures

Throughout history, a number of additional figures have played an important role in the development of educational psychology. Some of these well-known individuals include:

- John Locke : Locke is an English philosopher who suggested the concept of tabula rasa , or the idea that the mind is essentially a blank slate at birth. This means that knowledge is developed through experience and learning.

- Jean Piaget : A Swiss psychologist who is best known for his highly influential theory of cognitive development, Jean Piaget's influence on educational psychology is still evident today.

- B.F. Skinner : Skinner was an American psychologist who introduced the concept of operant conditioning, which influences behaviorist perspectives. His research on reinforcement and punishment continues to play an important role in education.

Educational psychology has been influenced by a number of philosophers, psychologists, and educators. Some thinkers who had a significant influence include William James, Alfred Binet, John Dewey, Jean Piaget, and Benjamin Bloom.

A Word From Verywell

Educational psychology offers valuable insights into how people learn and plays an important role in informing educational strategies and teaching methods. In addition to exploring the learning process itself, different areas of educational psychology explore the emotional, social, and cognitive factors that can influence how people learn. If you are interested in topics such as special education, curriculum design, and educational technology, then you might want to consider pursuing a career in the field of educational psychology.

A master's in educational psychology can prepare you for a career working in K-12 schools, colleges and universities, government agencies, community organizations, and counseling practices. A career as an educational psychologist involves working with children, families, schools, and other community and government agencies to create programs and resources that enhance learning.

The primary focus of educational psychology is the study of how people learn. This includes exploring the instructional processes, studying individual differences in how people learn, and developing teaching methods to help people learn more effectively.

Educational psychology is important because it has the potential to help both students and teachers. It provides important information for educators to help them create educational experiences, measure learning, and improve student motivation.

Educational psychology can aid teachers in better understanding the principles of learning in order to design more engaging and effective lesson plans and classroom experiences. It can also foster a better understanding of how learning environments, social factors, and student motivation can influence how students learn.

Parsonson BS. Evidence-based classroom behaviour management strategies . Kairaranga . 2012;13(1):16-20.

Welsh JA, Nix RL, Blair C, Bierman KL, Nelson KE. The development of cognitive skills and gains in academic school readiness for children from low-income families . J Educ Psychol . 2010;102(1):43-53. doi:10.1037/a0016738

Babakr ZH, Mohamedamin P, Kakamad K. Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory: Critical review . Asian Institute of Research: Education Quarterly Reviews. 2019;2(3). doi:10.31014/aior.1993.02.03.84

Roediger HL III. Applying cognitive psychology to education . Psychol Sci Public Interest . 2013;14(1):1-3. doi:10.1177/1529100612454415

Dennick R. Constructivism: Reflections on twenty five years teaching the constructivist approach in medical education . Int J Med Educ . 2016;7:200-205. doi:10.5116/ijme.5763.de11

Binson B, Lev-Wiesel R. Promoting personal growth through experiential learning: The case of expressive arts therapy for lecturers in Thailand . Front Psychol. 2018;8. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02276

Duque E, Gairal R, Molina S, Roca E. How the psychology of education contributes to research with a social impact on the education of students with special needs: The case of successful educational actions . Front Psychol. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00439

Barbier K, Donche V, Verschueren K. Academic (under)achievement of intellectually gifted students in the transition between primary and secondary education: An individual learner perspective . Front Psychol. 2019;10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02533

American Psychological Association. Careers in psychology .

Greenfield PM. The changing psychology of culture from 1800 through 2000 . Psychol Sci. 2013;24(9):1722-1731. doi:10.1177/0956797613479387

Hogan JD, Devonis DC, Thomas RK, et al. Herbart, Johann Friedrich . In: Encyclopedia of the History of Psychological Theories . Springer US; 2012:508-510. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0463-8_134

Sutinen A. William James’s educational will to believe . In: Theories of Bildung and Growth . SensePublishers; 2012:213-226. doi:10.1007/978-94-6209-031-6_14

Michell J. Alfred Binet and the concept of heterogeneous orders . Front Psychol . 2012;3. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00261

Talebi K. John Dewey - philosopher and educational reformer . Eur J Educ Stud. 2015;1(1):1-4.

Anderson LW. Benjamin S. Bloom: His life, his works, and his legacy . In: Zimmerman BJ, Schunk DH, eds., Educational Psychology: A Century of Contributions . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Androne M. Notes on John Locke’s views on education . Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;137:74-79. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.255

Overskeid G. Do we need the environment to explain operant behavior? . Front Psychol . 2018;9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00373

American Psychological Association. Understanding educational psychology .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Education can shape an individual's life, both in the classroom and outside of it. A quality education can lay the groundwork for a successful career , but that's far from its only purpose. Education—both formal and informal—imparts knowledge, critical thinking skills, and, in many cases, an improved ability to approach unfamiliar situations and subjects with an open mind.

Some of the pressures of modern education, by contrast, are thought to contribute to the increased incidence of mental health challenges among today’s children and young adults. Examining current approaches to education—and identifying the ways in which they may be counterproductive—can help parents, teachers, and other stakeholders better support students’ well-being.

To learn more about helping kids succeed in school, see Academic Problems and Skills .

- The Purpose of Education

- What Makes Education Effective?

- How Can We Improve Education?

Scholars and philosophers have debated the purpose of education throughout history. Some have argued that education was necessary for an engaged citizenry; some felt its purpose was to promote obedience and indoctrinate youth to dominant cultural ideas; still others believed that the pursuit of knowledge was in itself a virtuous or even spiritual goal. Today, conversations around the purpose of education tend to center around child development and the economy—that is, how education can help children grow into healthy, competent adults who are able to support themselves financially and contribute to society. Some experts warn, however, that excessive focus on the economic and pragmatic benefits of education deprives the process of joy. Humans—especially children—are natural learners, they argue, and learning may be most valuable when it’s pursued for its own sake.

Education, broadly defined, is valuable for teaching children the social, emotional, and cognitive skills needed to function in society. Formal education is thought to facilitate social learning , build executive functioning skills, and allow children to explore subjects they may not naturally be exposed to. Informal education typically allows them to cultivate their own interests and learn self-direction , itself an important life skill.

Ideally, in the modern world, education will teach both the technical skills needed for future success and cultivate the critical thinking abilities that allow humans to creatively approach problems, engage new perspectives, and innovate in an ever-changing world. Whether the current system of formal education does that effectively, however, is a source of great debate among the public and policymakers alike.

Most policymakers and educational psychologists agree that some kind of formal education is necessary to function in the modern world. But many experts argue its hyperfocus on grades, testing, and following a set curriculum, rather than children’s interests, can actually be counterproductive and interfere with the natural learning process that more informal education approaches often provide. Excessively rigid schooling is also thought to contribute to heightened anxiety among children, especially those who fall behind or are otherwise non-normative.

Homeschooling —in which a child is not enrolled in a formal school, but instead is educated by their parents or with other homeschoolers—has both strengths and drawbacks. Some common benefits reported by families include increased flexibility in what is studied, the ability to pace the curriculum to a child’s needs, and a supportive learning environment. Potential cons include reduced opportunities for socialization, limited diversity in the opinions and subjects that a child may be exposed to, and an emotional and intellectual burden placed on parents, who may struggle to keep their child engaged or update their own knowledge to ensure they’re imparting useful, up-to-date information.

Grades can be valuable tools in determining which children grasp the material and which are struggling. But despite widespread myths that good grades are necessary to succeed in life , high school and college grades do not necessarily correlate with long-term success. And hyperfocus on grades can have profoundly negative effects, as students who pursue perfect grades at all costs often struggle with anxiety , depression , or feelings of burnout .

Highly-ranked colleges are widely assumed to confer lifelong benefits to attendees, including higher incomes and more prestigious, satisfying careers. But this isn’t necessarily true. Indeed, evidence suggests that, when controlling for prior socioeconomic status and academic achievement, attending an elite college makes little difference in someone’s later income. Other research suggests that the type of college someone attends has no effect on their later life satisfaction; instead, having supportive professors or participating in meaningful activities during college best predicts someone’s future well-being.

Teachers, parents, and society at large have debated at length the criteria that denote a "good" education. In recent years, many educators have attempted to develop their curricula based on research and data, integrating the findings of developmental psychology and behavioral science into their lesson plans and teaching strategies. Recent debates have centered on how much information should be tailored to individual students vs. the class at large, and, increasingly, whether and how to integrate technology into classrooms. Students’ age, culture, individual strengths and weaknesses, and personal background—as well as any learning disabilities they may have—all play a role in the effectiveness of particular teachers and teaching methods.

The idea that education should be tailored to children’s different “learning styles”—typically categorized as visual, auditory, and kinesthetic—has been around for decades. But research has not found that creating targeted lessons based on children’s learning styles helps them learn more effectively ; some has even suggested that characterizing children as having one particular learning style could be unfairly limiting, and may stop them from tackling tasks outside of their comfort zone.

Children are by nature highly active, and an inability to move throughout the day often triggers inattention and poor mood—neither of which are conducive to learning. And moving during learning, not just before or after it, has been shown to be similarly beneficial; children who are allowed to move in class learn better , research shows, paying more attention and achieving higher outcomes.

Whether homework is beneficial is the subject of debate. Proponents argue that homework reinforces lessons and fosters time management and organizational skills. Opponents argue that excessive homework has been correlated with lower scores in critical subjects, like math and science, as well as worsened physical and mental health. Most experts argue that if homework is assigned, it should serve a specific purpose —rather than just being busywork—and should be tailored to a child’s age and needs.

In general, evidence suggests that online-only courses are less effective than courses where students are able to meet in person. However, when in-person learning is not possible—such as during the COVID-19 pandemic—well-designed distance learning programs can bridge the gap. Research indicates that online programs that mix passive instruction with active practice, and that allow students to progress at their own pace, tend to be most effective.

Depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders appear to be significantly more common in today's college students than they once were. Nearly 1 in 5 university students suffer from anxiety or depression, research suggests, and many colleges—particularly larger ones—will face at least one student suicide per year. The reasons for this are complex, experts warn, but may be due to factors including the increased prevalence of social media , the financial and academic stress of college, reduced economic opportunity upon graduation, and decreased resilience among today's youth as a result of parental over-involvement.

The world is changing rapidly, and so are children’s educational needs. While many people agree that education should prepare children for a competitive global economy, there has also been a push to recognize that children's well-being should be taken into consideration when planning curricula and structuring the school day.

To this end, parents and educators are confronting pedagogical questions such as: What is the optimal time to start school to make sure students can learn effectively—and get enough rest? How many and what kind of breaks do students need during the day? What are the best ways for students to learn, and do they differ depending on the subject being taught—or the students themselves?

In some of these areas, big changes are already taking place. Some states, for instance, are considering or have already passed laws that would delay school start times, making them more conducive to children's sleeping schedules. Other states have passed laws requiring recess, ensuring that children have access to physical activity throughout the day. These reforms, along with others, aim to protect children's physical and mental health—in addition to making them better able to focus, learn, and grow.

Many experts now believe that starting school later—typically after 8:30 A.M.—is better for children than starting earlier. This is particularly true for middle and high school children, who naturally sleep later than adults and may struggle to function if made to wake too early. Many school districts have implemented later school start times to account for this biological reality.

First and foremost, school recess provides the physical activity that is critical to a child’s physical and mental health. But recess is also an opportunity for children to socialize without (excessive) adult interference, which allows them to learn cooperation and conflict resolution skills.

Kindergarten and preschool programs are increasingly focusing on teaching children academic skills like math and reading. But evidence suggests that because children are not yet cognitively or emotionally equipped to handle most academic material, such early academic training can produce lasting harm . Some research has found that children in such programs do worse over the long term than children who spent preschool and kindergarten playing and socializing.

Children and young adults today are significantly more likely to experience mental health problems—especially anxiety and depression—than in decades past, and many will require mental health interventions at school. Evidence suggests that schools of any level can best support and help treat students with mental health disorders by proactively identifying students who need help, fostering a school culture that makes mental well-being a priority, and working to decrease stigma surrounding mental health care, both among students and their families. For students without diagnosable mental illnesses, schools can still be supportive by ensuring workloads are reasonable; providing opportunities for movement, creativity , and social connection; and reminding children, teenagers , and young adults that it's OK to ask for help.

The kids are all right... as long as we give them the space and opportunity to flex their independence.

When students don't feel like a part of their school community, learning suffers. Better architecture leads to better outcomes.

Can "drill and kill" give way to play in handwriting instruction?

Personal Perspective: One way to enrich the learning environment for students and facilitate interactions is to introduce a well-trained therapy dog to the classroom.

Everyone fears being made to look foolish. What really constitutes foolishness is the inability to separate fiction from fact,

How do you form an effective argument? A new book by Ward Farnsworth helps explain.

A Personal Perspective: Think brand-management consultations can fix what ails higher education? Think again.

No one likes to make mistakes, but we all make them. Here's why acknowledging and celebrating our mistakes is good for us—and for our kids.

Which teachers do you most remember? The ones who were inspired and inspiring, and the ones who cared. Here's how to be a great teacher.

Discover how animals are more than just pets. They're partners in healing. Dive into the therapeutic world of animal-assisted interactions.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

What Is Educational Psychology? 6 Examples and Theories

Plato believed that learning is based on the mind’s innate capacity to receive information and judge its intellectual and moral value.

Plato’s foremost pupil, Aristotle, emphasized how learning involves building associations such as succession in time, contiguity in space, and similarities and/or contrasts.

Later thinkers would devote considerable attention to learning and memory processes, various teaching methods, and how learning can be optimized.

Together, these thinkers have formed the growing and diverse body of theory and practice of educational psychology, and this intriguing topic is what we will discuss below.

Before you continue, you might like to download three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is educational psychology and why is it important, a brief history of the field, job description and roles of an educational psychologist, 3 real-life examples, 3 popular theories, educational psychology research topics, educational psychology vs school psychology, a look into vygotsky’s ideas, positivepsychology.com’s relevant resources, a take-home message.

Educational psychology is dedicated to the study and improvement of human learning, across the lifespan, in whatever setting it occurs.

Such settings include not only schools, but also workplaces, organized sports, government agencies, and retirement communities – anywhere humans are engaged in instruction and learning of some type.

Educational psychology is important because of its focus on understanding and improving the crucial human capacity to learn.

In this mission of enhancing learning, educational psychologists seek to assist students and teachers alike.

However, it was not until later in history that educational psychology emerged as a field in its own right, distinct from philosophy.

John Locke (1632–1704), the influential British philosopher and “father of psychology,” famously described the human mind as a tabula rasa (blank slate) that had no innate or inborn knowledge, but could only learn through the accumulation of experiences.

Johann Herbart (1776–1841) is considered the founder of educational psychology as a distinct field. He emphasized interest in a subject as a crucial component of learning.

He also proposed five formal steps of learning:

- Reviewing what is already known

- Previewing new material to be learned

- Presenting new material

- Relating new material to what is already known

- Showing how new knowledge can be usefully applied

Maria Montessori (1870–1952) was an Italian physician and educator who started by teaching disabled and underprivileged children. She then founded a network of schools that taught children of all backgrounds using a hands-on, multi-sensory, and often student-directed approach to learning.

Nathaniel Gage (1917–2008) was an influential educational psychologist who pioneered research on teaching. He served in the U.S. Army during WWII, where he developed aptitude tests for selecting airplane navigators and radar operators.

Gage went on to develop a research program that did much to advance the scientific study of teaching.

He believed that progress in learning highly depends on effective teaching and that a robust theory of effective teaching has to cover:

- The process of teaching

- Content to be taught

- Student abilities and motivation level

- Classroom management

The above is only a sample of the influential thinkers who have contributed over time to the field of educational psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Educational psychologists have typically earned either a master’s degree or doctorate in the field.

They work in a variety of teaching, research, and applied settings (e.g., K–12, universities, the military, and educational industries like textbook and test developers).

Those with a doctorate often teach and do research at colleges or universities.

They teach basic courses such as Introduction to Educational Psychology and more advanced seminars such as Professional Ethics in Educational Psychology , or Research Methods in Educational Psychology .

They conduct research on topics such as the best measure of literacy skills for students in secondary education, the most effective method for teaching early career professionals in engineering, and the relationship between education level and emotional health in retirees.

Educational psychologists also work in various applied roles, such as consulting on curriculum design; evaluating educational programs at schools or training sites; and offering teachers the best instructional methods for a subject area, grade level, or population, be it mainstream students, those with disabilities, or gifted students.

This theory states that besides the traditionally measured verbal and visual–spatial forms of intelligence, there are also forms that include kinesthetic or athletic intelligence, interpersonal or social–emotional intelligence, musical or artistic intelligence, and perhaps other forms we have not yet learned to measure.

Dr. Gardner teaches, conducts research, and publishes. His many books include Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences (1983) and The Disciplined Mind: Beyond Facts and Standardized Tests, the Education That Every Child Deserves (2000).

Mamie Phipps Clark (1917–1983), shown above, was the first African-American woman to receive a doctorate in psychology from Columbia University. She and her husband Kenneth Clark (1914–2005) were interested in development and self-esteem in African-American children.

Her doctoral work illustrated the dehumanizing effect of segregated schools on both African-American and white children, in the well-known “doll study” (Clark & Clark, 1939). She found that both African-American children and white children imputed more positive characteristics to white dolls than to Black dolls.

This work was used as evidence in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the unanimous U.S. Supreme Court ruling that decided that schools separated by race were not equal and must be desegregated.

She and her husband founded several institutions dedicated to providing counseling and educational services for underprivileged African-American children, including the Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited project.

Irene Marie Montero Gil earned her master’s degree from the Department of Evolutionary and Educational Psychology at the Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain.

Ms. Montero Gil had been balancing subsequent doctoral studies with her role as the youngest member of Spain’s Congress of Deputies, representing Madrid. She later postponed her studies to become Spain’s Minister of Equality, an office that advocates for equal opportunity regardless of age, gender, or disability.

The above examples show just some contributions that educational psychologists can make in research, teaching, legal, and advocacy contexts.

Day in the life of an educational psychologist w/ Dr. Sarah Chestnut

Various theories have been developed to account for how humans learn. Some of the most enduring and representative modern-day theories are discussed below.

1. Behaviorism

Behaviorism equates learning with observable changes in activity (Skinner, 1938). For example, an assembly line worker might have “learned” to assemble a toy from parts, and after 10 practice sessions, the worker can do so without errors within 60 seconds.

In behaviorism, there is a focus on stimuli or prompts to action (your supervisor hands you a box of toy parts), followed by a behavior (you assemble the toy), followed by reinforcement or lack thereof (you receive a raise for the fastest toy assembly).

Behaviorism holds that the behavioral responses that are positively reinforced are more likely to recur in the future.

We should note that behaviorists believe in a pre-set, external reality that is progressively discovered by learning.

Some scholars have also held that from a behaviorist perspective, learners are more reactive to environmental stimuli than active or proactive in the learning process (Ertmer & Newby, 2013).

However, one of the most robust developments in the later behaviorist tradition is that of positive behavioral intervention and supports (PBIS), in which proactive techniques play a prominent role in enhancing learning within schools.

Such proactive behavioral supports include maximizing structure in classrooms, teaching clear behavioral expectations in advance, regularly using prompts with students, and actively supervising students (Simonsen & Myers, 2015).

Over 2,500 schools across the United States now apply the PBIS supportive behavioral framework, with documented improvements in both student behavior (Bradshaw, Waasdorp, & Leaf, 2012) and achievement (Madigan, Cross, Smolkowski, & Stryker, 2016).

2. Cognitivism

Cognitivism was partly inspired by the development of computers and an information-processing model believed to be applicable to human learning (Neisser, 1967).

It also developed partly as a reaction to the perceived limits of the behaviorist model of learning, which was thought not to account for mental processes.

In cognitivism, learning occurs when information is received, arranged, held in memory, and retrieved for use.

Cognitivists are keenly interested in a neuronal or a brain-to-behavior perspective on learning and memory. Their lines of research often include studies involving functional brain imaging (e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging) to see which brain circuits are activated during specific learning tasks.

Cognitivists are also keenly interested in “neuroplasticity,” or how learning causes new connections to be made between individual brain cells (neurons) and their broader neuronal networks.

From the cognitivist perspective, individuals are viewed as very active in the learning process, including how they organize information to make it personally meaningful and memorable.

Cognitivists, like behaviorists, believe that learning reflects an external reality, rather than shaping or constructing reality.

3. Constructivism

Constructivism holds that from childhood on, humans learn in successive stages (Piaget, 1955).

In these stages, we match our basic concepts, or “schemas,” of reality with experiences in the world and adjust our schemas accordingly.

For example, based on certain experiences as a child, you might form the schematic concept that all objects drop when you let them go. But let’s say you get a helium balloon that rises when you let go of it. You must then adjust your schema to capture this new reality that “most things drop when I let go of them, but at least one thing rises when I let go of it.”

For constructivists, there is always a subjective component to how reality is organized. From this perspective, learning cannot be said to reflect a pre-set external reality. Rather, reality is always an interplay between one’s active construction of the world and the world itself.

For example, Zysberg and Schwabsky (2020) examined the relationships between positive school culture or climate, students’ sense of self-efficacy, and academic achievement in Israeli middle and high school settings.

They found that school climate was positively associated with students’ sense of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy, in turn, was positively associated with academic achievement in math and English.

This study reflects a constructivist approach, emphasizing how students create meaning out of their educational experiences.

Other recent research has focused on behavioral interventions to support online learning, which is increasingly prevalent as an educational option.

For example, Yeomans and Reich (2017) found that sending learners regular prompts to complete online work resulted in a 29% increase in courses completed. They concluded that sending regular reminder prompts is an inexpensive and effective way to enhance online course completion.

This study reflects a proactive behaviorist approach to improving educational outcomes.

Another current research domain in educational psychology involves the use of brain imaging techniques during learning activity.

For example, Takeuchi, Mori, Suzukamo, and Izumi (2019) studied brain activity in teachers and students while teachers provided hints for solving a visual–spatial problem (assembling puzzles).

They found that the prefrontal cortex of the brain, involved in planning and monitoring of complex cognitive activities, was significantly activated in teachers, not when they planned hints to be given, but only when they actually gave the hints.

For the student participants, the prefrontal cortex was significantly activated when they had solved the puzzle with hints provided.

This study emphasizes a cognitivist approach, focused on brain activity during learning.

For cognitivists, understanding how the brain converts instructional inputs into learning can lead to improved teaching strategies and better learning outcomes.

Educational and school psychologists overlap in their training and functions, to some extent, but also differ in important ways.

Educational psychologists are more involved in teaching and research at the college or university level. They also focus on larger and more diverse groups in their research and consulting activities.

As consultants, educational psychologists work with organizations such as school districts, militaries, or corporations in developing the best methods for instructional needs.

Some school psychologists are involved in teaching, research, and/or consulting with large groups such as a school district. However, most are more focused on working within a particular school and with individual students and their families.

About 80% of school psychologists work in public school settings and do direct interventions with individuals or small groups.

They help with testing and supporting students with special needs, helping teachers develop classroom management strategies, and engaging in individual or group counseling, which can include crisis counseling and emotional–behavioral support.

One idea central to Vygotsky’s learning theory is that of the zone of proximal development (ZPD).

The ZPD is the area between what a learner (student, adult trainee, rehabilitation patient, etc.) can already do on their own and what the learner can readily accomplish with the help of teachers or more advanced peers.

For example, a five-year-old might already know how to perform a given three-step manual task, but can they be taught to complete a four- or five-step task?

The ZPD is a zone of emerging skills, which calls for its own kind of exploration and measurement, in order to better understand a learner’s potential (Moll, 2014).

Vygotsky was also interested in the relationship between thought and language. He theorized that much of thought comprised internalized language or “inner speech.” Like Piaget, whose work he read with interest, Vygotsky came to see language as having social origins, which would then become internalized as inner speech.

In that sense, Vygotsky is often considered a (social) constructivist, where learning depends on social communication and norms. Learning thus reflects our connection to and agreement with others, more than a connection with a purely external or objective reality.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

As mentioned in the discussion of Nathaniel Gage’s theory of effective teaching, student motivation is an important component to assess and encourage.

The Who Am I Self-Reflection can help students and their teachers think about what they are good at, what significant challenges they have been confronted with, and what inspires them. This knowledge can help both teachers and students find ways to enhance motivation in specific cases.

As noted above, the cognitivist approach to educational psychology includes understanding how the brain learns by forming new connections between neurons. The Adopt A Growth Mindset activity is a simple guide to replacing fixed mindset thinking with growth statements. It can inspire adults to learn by referencing their inherent neuroplasticity.

The idea is that with enough effort and repetition, we can form new and durable connections within our brains of a positive and adaptive nature.

For parents and teachers, we recommend Dr. Gabriella Lancia’s article on Healthy Discipline Strategies for Teaching & Inspiring Children . This article offers basic and effective strategies and worksheets for creating a positive behavioral climate at home and school that is pro-social and pro-learning.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

The field of educational psychology has ancient roots and remains vibrant today.

Today, there are many programs across the world providing quality training in educational psychology at the master’s, doctoral, and postdoctoral levels.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, career opportunities in psychology will grow at a healthy rate of about 14% over this decade, and educational psychology is expected to keep pace.

In addition, job satisfaction in educational psychology and related fields such as school psychology has traditionally been high, including as it concerns social impact, independence, and compensation (Worrell, Skaggs, & Brown, 2006).

Those with a doctorate in educational psychology have potential for a broad impact on learners of any and every type. They often teach at the college or university level, conduct research and publish on various topics in the field, or consult with various organizations about the best teaching and learning methods.

Researchers in educational psychology have made important contributions to contemporary education and culture, from learning paradigms (behaviorism, cognitivism, constructionism) and the theory of multiple intelligences, to proactive school-wide positive behavioral supports.

We hope you have learned more about the rich field of educational psychology from this brief article and will find the resources it contains useful. Don’t forget to download our free Positive Psychology Exercises .

- Brown v. Board of Education , 347 U.S. (1954).

- Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & Leaf, P. J. (2012). Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems. Pediatrics , 130 (5), e1136–e1145.

- Clark, K., & Clark, M. (1939). The development of consciousness of self and the emergence of racial identification in Negro preschool children. Journal of Social Psychology , 10 (4), 591–599.

- Ertmer, P. A., & Newby, T. J. (2013). Behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism: Comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly , 26 (2), 43–71.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences . Basic Books.

- Gardner, H. (2000). The disciplined mind: Beyond facts and standardized tests, the education that every child deserves . Penguin Books.

- Grinder, R. E. (1989). Educational psychology: The master science. In M. C. Wittrock & F. Farley (Eds.), The future of educational psychology (pp. 3–18). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Madigan, K., Cross, R. W., Smolkowski, K., & Stryker, L. A. (2016). Association between schoolwide positive behavioural interventions and supports and academic achievement: A 9-year evaluation. Educational Research and Evaluation , 22 (7–8), 402–421.

- Moll, L. C. (2014). L. S. Vygotsky and education . Routledge.

- Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive psychology . Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Piaget, J. (1955). The child’s construction of reality . Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Simonsen, B., & Myers, D. (2015). Classwide positive behavior interventions and supports: A guide to proactive classroom management . Guilford Publications.

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . B. F. Skinner Foundation.

- Takeuchi, N., Mori, T., Suzukamo, Y., & Izumi, S. I. (2019). Activity of prefrontal cortex in teachers and students during teaching of an insight problem. Mind, Brain, and Education , 13 , 167–175.

- Worrell, T. G., Skaggs, G. E., & Brown, M. B. (2006). School psychologists’ job satisfaction: A 22-year perspective in the USA. School Psychology International , 27 (2), 131–145.

- Yeomans, M., & Reich, J. (2017). Planning prompts increase and forecast course completion in massive open online courses. Conference: The Seventh International Learning Analytics & Knowledge Conference , pp. 464–473.

- Zysberg, L., & Schwabsky, N. (2020). School climate, academic self-efficacy and student achievement . Educational Psychology. Taylor & Francis Online.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Am happy with you thanks again God bless you and your family

This write up is very rich and brief. keep it up our Educational Psychologist.

What’s education psychology? With references of 2018 to 2022

Hi Justusa,

Sorry, I’m not sure what you’re asking. Could you please rephrase and I’ll see if I can help!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Nice introduction. Thank you!

Very detailed and comprehensive

Thanks so much for this brief and comprehensive resource material.Much appreciated

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Learning Disabilities: 9 Types, Symptoms & Tests

Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, Sylvester Stalone, Thomas Edison, and Keanu Reeves. What do all of these individuals have in common? They have all been diagnosed [...]

Best Courses for Counselors to Grow & Develop Your Skills

Counselors come from a great variety of backgrounds often with roots in a range of helping professions. Every counselor needs to keep abreast of the [...]

How to Apply Social-Emotional Learning Activities in Education

As a teacher, your training may have focused more on academia than teaching social skills. Now in the classroom, you face the challenge of implementing [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Educational Psychology

Developments and Contestations

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 04 April 2020

- Cite this reference work entry

- Katie Wright 2 &

- Emma Buchanan 3

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE))

1278 Accesses

4 Citations

Educational psychology is a multifaceted and contested domain of knowledges and practices that resists simple definition. Its forms and foci have varied across time and place, and strands of knowledge and practice that have travelled under this disciplinary descriptor have been shaped by, and contributed to, shifting understandings of the problems and promises of education. Concepts of individual differences and forms of mental measurement are readily associated with the emergence of educational psychology. Yet, its history is broad in scope, including concerns with child development, adjustment, learning, and behavior. This chapter focuses on two major strands of historical studies of educational psychology: key figures and disciplinary developments; and critical analyses of its knowledges, practices, and impact. A concise overview of the history of educational psychology from the late nineteenth to the late twentieth century is provided. The chapter considers major strands of thought, contexts of emergence, and sites of development, as documented by historians. This includes exploration of foundational influences and examination of the role that various waves of psychological thought have played in shaping policy and in forming understandings about best practice in education, from compulsory schooling spaces to more informal educational sites such as child guidance clinics and preschools. Alongside this mapping of the historiography, central debates about the scope, promise, dangers, and effects of psychology as a foundational knowledge for education are outlined. Here, consideration is given to discussions in the past as well as more recent interpretations and critical angles.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adams, J. The Herbartian psychology applied to education. London: DC. Heath; 1897.

Google Scholar

Baker B. In perpetual motion: theories of power, educational history, and the child. New York: Peter Lang; 2001.

Beauvais C. Ages and ages: the multiplication of children’s “ages” in early twentieth-century child psychology. Hist Educ. 2016;45(3):304–18.

Article Google Scholar

Berk L. Child development. New York: Pearson; 2013.

Berliner D. The 100-year journey of educational psychology: from interest, to disdain, to respect for practice. In: Anastasia A, Fagan T, VandenBos G, editors. Exploring applied psychology: origins and critical analyses. Washington: American Psychological Association; 1993. p. 41–78.

Berliner D, Calfee R. Introduction to a dynamic and relevant educational psychology. In: Berliner D, Calfee R, editors. Handbook of educational psychology. New York: Routledge; 1996. p. 1–11.

Blumentritt TL. Personality tests. In: Salkind NJ, editor. Encyclopedia of educational psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. p. 780–6.

Boake C. From the Binet–Simon to the Wechsler–Bellevue: tracing the history of intelligence testing. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24(3):383–405.

Burman E. Deconstructing developmental psychology. 3rd ed. Sussex: Routledge; 2017.

Cannella GS. Deconstructing early childhood education: social justice and revolution. New York: Peter Lang; 1997.

Charles D. A historical overview of educational psychology. Contemp Educ Psychol. 1976;1:76–88.

Charles D. The emergence of educational psychology. In: Glover J, Ronning R, editors. Historical foundations of educational psychology. New York: Springer; 1987. p. 17–38.

Chapter Google Scholar

Collins WA, Hartup WW. History of research in developmental psychology. In: Zelaro P, editor. The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology, Body and mind, vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 1–42.

Davidson E, Benjamin L. A history of the child study movement in America. In: Glover JA, Ronning RR, editors. Historical foundations of educational psychology. New York: Springer; 1987. p. 41–60.

Du Rocher Schudlich T. Psychoanalytic theory. In: Salkind NJ, editor. Encyclopedia of educational psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. p. 815–9.

Ecclestone K, Brunila K. Governing emotionally vulnerable subjects and the “therapisation” of social justice. Pedagog Cult Soc. 2015;23(4):485–506.

Ecclestone K, Hayes D. The dangerous rise of therapeutic education. London: Routledge; 2009.

Book Google Scholar

Evans E. Modern educational psychology: an historical introduction. London: Routledge & Keagan Paul; 1969.

Evans B, Rahman S, Jones E. Managing the “unmanageable”: interwar child psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital, London. Hist Psychiatry. 2008;19(4):454–75.

Faulkner M, Jimerson S. National and international perspectives on school psychology: practice and policy. In: Thielking M, Terjesen M, editors. Handbook of Australian school psychology: integrating international research, practice, policy. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 1–19.

Fletcher R. Science, ideology and the media: the Cyril Burt Scandal. London: Routledge; 2017.

Fletcher R, Hattie J. Intelligence and intelligence testing. London: Routledge; 2011.

Galton, F. Hereditary genius: an inquiry into its laws and consequences. London: Macmillan; 1869.

Giardiello P. Pioneers of early childhood education: the roots and legacies of Rachel and Margaret McMillan, Maria Montessori and Susan Isaacs. Oxon: Routledge; 2014.

Glover J, Ronning R. Introduction. In: Glover J, Ronning R, editors. Historical foundations of educational psychology. New York: Springer; 1987. p. 3–15.

Gross R. Themes, issues and debates in psychology. London: Hodder Education; 2009.

Harwood V, Allan J. Psychopathology at school: theorizing mental disorders in education. London: Routledge; 2014.

Herbart, JF. Psychologie als wissenschaft, neu gegründet auf erfahrung, metaphysik, und mathematik. [Psychology as a science, newly founded on experience, metaphysics, and mathematics]. Königsberg: August Wilhelm Unzer; 1824.

Hilgard E. History of educational psychology. In: Berliner D, Calfee R, editors. Handbook of educational psychology. New York: Routledge; 1996a. p. 990–1004.

Hilgard E. Perspectives on educational psychology. Educ Psychol Rev. 1996b;8(4):419–31.

Horn M. Before it’s too late: the child guidance movement in the United States, 1922–1945. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1989.

James, W. Talks to teachers on psychology: and to students on some of life’s ideals. New York: Henry Holt; 1899.

Jensen A. Individual differences in mental ability. In: Glover J, Ronning R, editors. Historical foundations of educational psychology. New York: Springer; 1987. p. 61–88.

Jones K. Taming the troublesome child: American families, child guidance, and the limits of psychiatric authority. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999.

Judd, C. Genetic psychology for teachers. New York: Appleton; 1903.

Klein JT. Interdisciplinarity: history, theory, and practice. Detroit: Wayne State University Press; 1990.

Leadbetter J, Arnold C. Looking back: a hundred years of applied psychology. The Psychologist. 2013;26(9):696–8.

May H. Politics in the playground: the world of early childhood in New Zealand. Revised ed. Dunedin: Otago University Press; 2009.

Mayer R. E. L. Thorndike’s enduring contributions to educational psychology. In: Zimmerman B, Schunk D, editors. Educational psychology: a century of contributions. New York: Routledge; 2003. p. 113–54.

McCulloch G. The struggle for the history of education. Oxen: Routledge; 2011.

McKibbin R. Classes and cultures in England 1918–1951. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998.

McLeod J, Wright K. Education for citizenship: transnational expertise, curriculum reform and psychological knowledge in 1930s Australia. Hist Educ Rev. 2013;42(2):170–84.

Oakley L. Cognitive development. Essex: Routledge; 2004.

Rose N. The psychological complex: psychology, politics and society in England, 1869–1939. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1985.

Rose N. Governing the soul: the shaping of the private self. London: Routledge; 1990.

Sheehy N. Fifty key thinkers in psychology. London: Routledge; 2004.

Stewart J. Child guidance in Britain, 1918–1955: the dangerous age of childhood. London: Routledge; 2016.

Thompson D, Hogan J, Clark P. Developmental psychology in historical perspective. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

Thomson M. Psychological subjects: identity, culture, and health in twentieth-century Great Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Thorndike-Christ T, Thorndike RM. Intelligence tests. In: Salkind NJ, editor. Encyclopedia of educational psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. p. 548–54.

Turmel A. A historical sociology of childhood: developmental thinking, categorization and graphic visualization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Turtle A. Education, science and the “common weal”. In: MacLeod R, editor. The commonwealth of science: ANZAAS and the Scientific Enterprise in Australasia, 1888–1988. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 1987. p. 222–46.

Van Fleet A. Charles Judd’s psychology of schooling. Elem Sch J. 1976;76(8):455–63.

Varga D. Look – normal: the colonized child of developmental science. Hist Psychol. 2011;14(2):137–57.

Walberg HJ, Haertel GD. Educational psychology’s first century. J Educ Psychol. 1992;84(1):6–19.

Walker R, Debus R. Educational psychology: advances in learning, cognition and motivation. Change Transform Educ. 2002;5(1):1–25.

Walkerdine V. Developmental psychology and the child-centred pedagogy: the insertion of Piaget into early education. In: Henriques J, Hollway W, Urwin C, Venn C, Walkerdine V, editors. Changing the subject: psychology, social regulation and subjectivity. London: Methuen & Co; 1984. p. 153–202.

Wooldridge A. Measuring the mind: education and psychology in England, c.1860–c.1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Wright K. Rise of the therapeutic society: psychological knowledge & the contradictions of cultural change. Washington, DC: New Academia; 2011.

Wright K. “To see through Johnny and to see Johnny through”: the guidance movement in interwar Australia. J Educ Adm Hist. 2012;44(4):317–37.

Wright K, McLeod J, editors. Rethinking youth wellbeing: critical perspectives. Singapore: Springer; 2015.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Inquiry, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Katie Wright

Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Emma Buchanan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katie Wright .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Graduate School of Education, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

Tanya Fitzgerald

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Wright, K., Buchanan, E. (2020). Educational Psychology. In: Fitzgerald, T. (eds) Handbook of Historical Studies in Education. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2362-0_32

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2362-0_32

Published : 04 April 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-2361-3

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-2362-0

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

How the psychology of education contributes to research with a social impact on the education of students with special needs: the case of successful educational actions.

- 1 Department of Theory and History of Education, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 2 Department of Pedagogy, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain

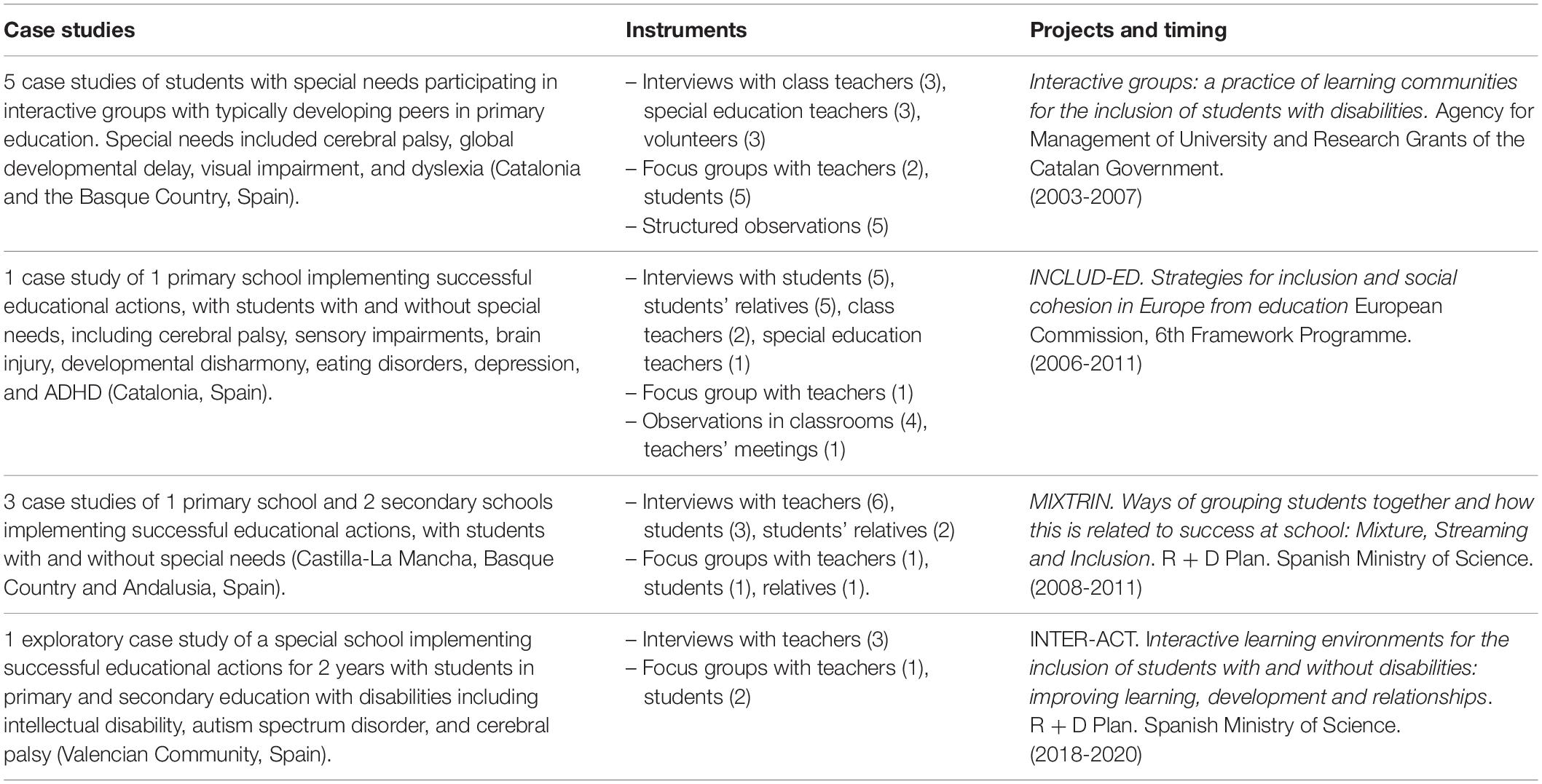

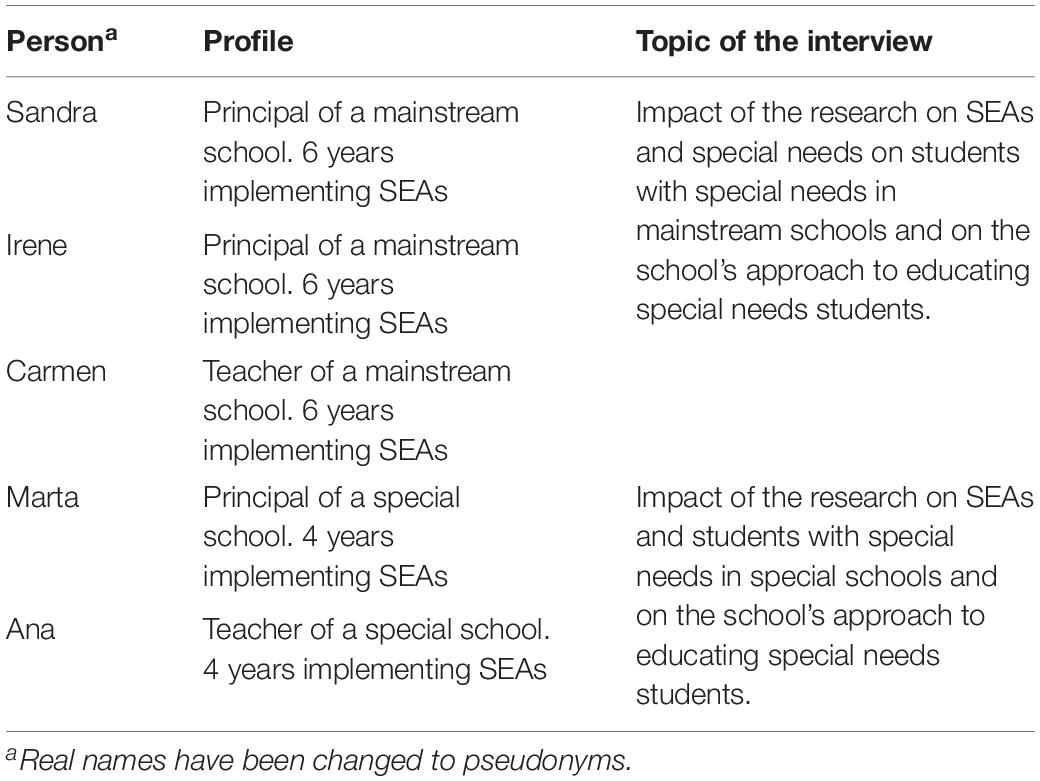

- 3 Departament of Comparative Education and Education History, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain

One current challenge in the psychology of education is identifying the teaching strategies and learning contexts that best contribute to the learning of all students, especially those whose individual characteristics make their learning process more difficult, as is the case for students with special needs. One main theory in the psychology of education is the sociocultural approach to learning, which highlights the key role of interaction in children’s learning. In the case of students with disabilities, this interactive understanding of learning is aligned with a social model of disability, which looks beyond individual students’ limitations or potentialities and focuses on contextual aspects that can enhance their learning experience and results. In recent years, the interactive view of learning based on this theory has led to the development of educational actions, such as interactive groups and dialogic literary gatherings, that have improved the learning results of diverse children, including those with disabilities. The aim of this paper is to analyze the social impact achieved by a line of research that has explored the benefits of such successful educational actions for the education of students with special needs. National and European research projects based on the communicative methodology of research have been conducted. This methodology entails drawing on egalitarian dialogue with the end-users of research – including teachers, students with and without disabilities, students’ relatives and other community members – to allow an intersubjective creation of knowledge that enables a deeper and more accurate understanding of the studied reality and its transformative potential. This line of research first allowed the identification of the benefits of interactive learning environments for students with disabilities educated in mainstream schools; later, it allowed the spreading of these actions to a greater number of mainstream schools; and more recently, it made it possible to transfer these actions to special schools and use these actions to create shared learning spaces between mainstream and special schools. The improvement of the educational opportunities for a greater number and greater diversity of students with special needs evidences the social impact of research based on key contributions of the psychology of education.

Introduction

Access to mainstream, inclusive and quality education for children with disabilities has not yet been fully achieved. Children with disabilities are still being educated in special schools in most countries, with varying percentages depending on the country, and therefore these schools attend diverse special needs ( World Health Organization, 2011 ). In addition, students with disabilities and special needs tend to leave school without adequate qualifications ( European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2017 ). Therefore, the appropriate inclusion of children with disabilities into the general education system is part of the European Disability Strategy 2010–2020 ( European Commission, 2010 ). In this context, one current challenge of the psychology of education is to identify the teaching strategies and learning contexts that best contribute to the education of students with special needs. In this endeavor, research in the psychology of education is focused on the strategies, actions and practices that enhance the learning of these students, taking into account their individual characteristics, however, importantly, research is also focused on the strategies, actions and programs that benefit the learning of all students, including those whose individual characteristics make the learning process more difficult, so that shared learning environments that promote successful learning for all can be created.

Instrumental learning, especially in regards to difficulties in reading and literacy, is one of the main concerns of research on the psychology of education ( Lloyd et al., 2009 ; Alanazi, 2017 ; Alenizi, 2019 ; Auphan et al., 2019 ; Hughes et al., 2018 ). Numerous programs for improving reading and/or reading difficulty prevention have emerged from research on reading and literacy from the perspective of the psychology of education, and their impact on improving children’s learning has been analyzed ( Vellutino and Scanlon, 2002 ; Papadopoulos et al., 2004 ; Hatcher et al., 2006 ). There are also specific studies about reading and literacy programs and their success with students with special needs ( Holliman and Hurry, 2013 ) and/or with students at risk for reading disabilities ( Lovett et al., 2017 ). Strategies to promote the learning of mathematics in children with special educational needs and disabilities have also been studied ( Pitchford et al., 2018 ), and programs based on these strategies have been developed ( Montague et al., 2014 ).

Research has also explored the association between learning difficulties and behavior problems ( Roberts et al., 2019 ), showing that lower academic achievement is a risk factor for developing behavior difficulties among students with special educational needs and disabilities ( Oldfield et al., 2017 ). The study of the learning context and the school environment, which facilitates or hinders learning, has shown that the expectations from teachers and their attitudes toward children with special needs are some of the most influential elements ( Anderson et al., 2014 ; Wilson et al., 2016 ; Bowles et al., 2018 ). Research has also found that teachers can have an important influence on the social acceptance of peers with special needs ( Schwab et al., 2016 ), which is important because the social exclusion of children can affect their learning difficulties and behavior problems ( Krull et al., 2018 ). The efficacy of peer network interventions for improving the social connections of students with severe disabilities has been highlighted ( Asmus et al., 2017 ), and programs and educational actions based on peer interaction, such as cooperative learning ( Velázquez Callado, 2012 ), have been developed to improve the school climate. Importantly, there are effective programs for improving peer acceptance and a positive coexistence related to curricular learning ( Law et al., 2017 ; Vuorinen et al., 2019 ), which is a key issue in facilitating inclusive education.

This body of research on effective actions and programs to enhance the learning and inclusion of students with disabilities and special needs shows the capacity that research in the psychology of education has for improving the education of these students. It also shows the importance that the learning context has, regarding both instruction and social relations, on the academic and social performance of students with special needs. This resonates with the social model of disability, an approach that has been claimed, from the perspective of human rights, to shift the focus from non-disabled centrism and to transcend the traditional and individualistic perspective of disabilities to focus on the improvement of educational experiences for these students ( Chun Sik Min, 2010 ; Park, 2015 ). This perspective assumes not only that children with disabilities should be included in mainstream education but also that inclusive education can be more effective ( Lindsay, 2007 ). This interactive understanding of learning allows seeing beyond individual students’ limitations or potentialities and focusing on contextual aspects that can enhance their learning experience and results ( Goodley, 2001 ; Haegele and Hodge, 2016 ).

The classical psychology of education already emphasized the importance of the social context for children’s learning. In particular, the sociocultural approach of learning developed by Vygotsky and Bruner highlighted the key role of interaction in children’s learning and development. Both authors agreed that what a child learns has been shared with other persons first, emphasizing the social construction of knowledge. While Vygotsky (1980) stated that in children’s development, higher psychological functions appear first on the interpsychological level and then on the intrapsychological level, Bruner (1996) refers to a social moment where there is interaction and then an individual moment when interiorization occurs.

Bruner evolved from a more cognitivist perspective of learning centered on individuals’ information processing ( Bruner, 1973 ) to a more sociocultural and interactive perspective ( Bruner, 1996 ) within the framework of which he conceptualized the idea of “scaffolding,” which enables novice learning in interaction with an expert, and “subcommunities of mutual learners,” where “learners help each other learn” and “scaffold for each other” ( Bruner, 1996 , p. 21). For Bruner, “It is principally through interacting with others that children find out what the culture is about and how it conceives of the world” (1996, p. 20); therefore, learning occurs through interaction within a community.

Vygotsky stated that learning precedes development, not the other way around, and he conceptualized the zone of proximal development (ZPD), which represents the opportunity that learning interactions with adults and more capable peers have to advance children’s development ( Vygotsky, 1980 ); beyond the actual level of development, the ZPD emphasizes the importance of interactions with others to solve problems and learn. He emphasized that this interaction is especially important for children with disabilities: “Precisely because retarded children, when left to themselves, will never achieve well elaborated forms of abstract thought, the school should make every effort to push them in that direction and to develop in them what is intrinsically lacking in their own development” ( Vygotsky, 1980 , p. 89). In this regard, he warned of the risks of working with children with disabilities from a perspective centered on biological processes and basic dysfunctions instead of working with higher psychological functions ( Vygotsky, 2018 ). Vygotsky’s focus on interaction provides new opportunities for learning and development for children with special needs to develop these higher psychological processes.

The sociocultural approach of learning developed by Vygotsky and Bruner has continued inspiring theory and research in the psychology of education to today. According to Dainez and Smolka (2014) , Vygotsky’s concept of compensation in relation to children with disabilities implies a social formation of mind and therefore the social responsibility of organizing an appropriate educational environment for these children. Vygotsky’s approach has been taken into account in studies about how peer mediation increases learning, especially when peers have different cognitive levels ( Tzuriel and Shamir, 2007 ), and research on children with disabilities, for instance, cerebral palsy, has been conducted based on Vygotsky’s contributions and showed improvements in these children’s spatial abilities, social interaction, autonomy, and participation in class activities ( Akhutina et al., 2003 ; Heidrich and Bassani, 2012 ).