Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- For authors

- New editors

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 52, Issue 22

- Rigorous qualitative research in sports, exercise and musculoskeletal medicine journals is important and relevant

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6325-2705 Susan C Slade 1 , 2 ,

- Shilpa Patel 3 ,

- Martin Underwood 3 ,

- Jennifer L Keating 1

- 1 Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences , Monash University , Melbourne , Victoria , Australia

- 2 La Trobe Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine Research , School of Allied Health/College of Science, Health and Engineering, La Trobe University , Melbourne , Victoria , Australia

- 3 Division of Health Sciences, Warwick Clinical Trials Unit , Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick , Coventry , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Susan C Slade, Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3128, Australia; susan.slade{at}monash.edu

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097833

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- qualitative

- methodology

Qualitative research enables inquiry into processes and beliefs through exploration of narratives, personal experiences and language. 1 Its findings can inform and improve healthcare decisions by providing information about peoples’ perceptions, beliefs, experiences and behaviour, and augment quantitative analyses of effectiveness data. The results of qualitative research can inform stakeholders about facilitators and obstacles to exercise, motivation and adherence, the influence of experiences, beliefs, disability and capability on physical activity, exercise engagement and performance, and to test strategies that maximise physical performance.

High-quality qualitative research can also enrich interpretation of quantitative analyses and be pooled in metasyntheses for evaluation of strength of evidence; contribute to the development and implementation of clinical decision support aids, outcome measures and clinical practice guidelines 2 such as the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines ( www.nice.org.uk ) and Ottawa Panel guidelines for knee osteoarthritis 3 ; and inform health and social care. 4

In 2000, just 0.6% of papers in 170 general medical, mental health and nursing journals reported qualitative research. Between 1999 and 2008, the proportion of qualitative studies in 20 high-impact general medical and health services and policy research journals remained consistently low. 5 Our audit and assessment of Scopus top 10 journals in ‘physical therapy, sports therapy and rehabilitation’ identified few qualitative publications. These ranged from zero to three per journal from January 2017 to August 2017. Other journals publishing reports in the field of exercise and sports medicine had better representation of qualitative research into exercise prescription for low back pain: for example, Journal of Physiotherapy (n=3), Clinical Rehabilitation (n=7) and Physiotherapy (n=11).

In sport and exercise research, qualitative analysis is fundamental to understanding factors such as exercise adherence, the nature of effective training, non-response to interventions and stakeholder priorities. 6 Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health is the first international journal dedicated solely to qualitative research in sport and exercise psychology, sport sociology, sports coaching, and sports and exercise medicine. Greater representation of qualitative research in BJSM would enhance the scope of its publications. Strategies that enhance the research rigour and credibility of qualitative research reports may promote acceptance of qualitative studies across a wider spectrum of journals.

Reporting guidelines

All research reports need to demonstrate that the work meets accepted standards for scientific rigour. Reporting guidelines and checklists such as the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) 7 guide the complete and transparent reporting of qualitative studies. A comprehensive study report provides the detail that readers need to appraise the credibility of findings. Formalised checklists create uniformity across publications and enable replication and validation, and facilitate translation of key findings to practice.

Risk of bias/trustworthiness

Items likely to be important to consider for risk of bias/assessment of internal validity are sampling strategies, adequacy (often termed saturation) of data collection to support theory development, participant protection, researcher bias, data collection methods designed to enhance accuracy, explicit analysis procedures, clarity in the links between data and results, and selective reporting bias.

Qualitative metasynthesis

A synthesis of evidence from qualitative research can provide ‘strength of evidence’ and benefits when qualitative data are available in peer-reviewed publications. 8 Comprehensive reporting is guided by the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) 9 statement. Assessment of overall confidence in review findings is guided by the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research. 9

The Equator Network: repository for reporting guidelines

Reporting guidelines are available on the Equator Network ( www.equator.org ). As an overview, empirical studies should include the headings of title and abstract, background, methods (theoretical framework, research team characteristics, participant selection, ethical issues, setting, data collection and analysis), results (synthesis, interpretation and links to empirical data), discussion and other (conflicts of interest, funding). 7 For metasynthesis, recommended headings are aim, synthesis method, eligibility criteria, data sources, search strategy, study selection, appraisal, data extraction and analysis steps, coding, theme derivation, supporting quotations, synthesis output and discussion. 10

Conclusion and recommendations

We encourage and support a higher profile of empirical qualitative studies and metasyntheses in BJSM and representation of stakeholder beliefs and experiences. It would advance reporting practices if authors submit, and editors require, manuscripts that comply with published reporting guidelines (COREQ for empirical studies; ENTREQ for metasyntheses). The quality of qualitative research publications might be advanced if reviewers use standardised reporting guidelines, and risk of bias assessment items that evaluate internal validity when reviewing manuscripts for publication. This would be facilitated by guideline checklists that are returned with manuscript review. We recommend and support a BJSM policy that requires completion of reporting guideline checklists for manuscript submission.

- Huberman AM ,

- Ziebland S ,

- Fitzpatrick R , et al

- Brosseau L ,

- Desjardins B , et al

- Noyes J , et al

- Gagliardi AR ,

- Stenner R ,

- Swinkels A ,

- Mitchell T , et al

- Sainsbury P ,

- Patel S , et al

- Glenton C ,

- Munthe-Kaas H , et al

- Flemming K ,

- McInnes E , et al

Contributors All authors have contributed to this editorial and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conflict of interest statement.

- < Previous

Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: a review of qualitative studies

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Steven Allender, Gill Cowburn, Charlie Foster, Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: a review of qualitative studies, Health Education Research , Volume 21, Issue 6, December 2006, Pages 826–835, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl063

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Qualitative research may be able to provide an answer as to why adults and children do or do not participate in sport and physical activity. This paper systematically examines published and unpublished qualitative research studies of UK children's and adults' reasons for participation and non-participation in sport and physical activity. The review covers peer reviewed and gray literature from 1990 to 2004. Papers were entered into review if they: aimed to explore the participants' experiences of sport and physical activity and reasons for participation or non-participation in sport and physical activity, collected information on participants who lived in the United Kingdom and presented data collected using qualitative methods. From >1200 papers identified in the initial search, 24 papers met all inclusion criteria. The majority of these reported research with young people based in community settings. Weight management, social interaction and enjoyment were common reasons for participation in sport and physical activity. Concerns about maintaining a slim body shape motivated participation among young girls. Older people identified the importance of sport and physical activity in staving off the effects of aging and providing a social support network. Challenges to identity such as having to show others an unfit body, lacking confidence and competence in core skills or appearing overly masculine were barriers to participation.

It is generally accepted that physical activity confers benefits to psychosocial health, functional ability and general quality of life [ 1 ] and has been proven to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease [ 2 ] and some cancers [ 3 ]. Here, physical activity refers to ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure’ [ 4 ].

Conditions associated with physical inactivity include obesity, hypertension, diabetes, back pain, poor joint mobility and psychosocial problems [ 5–7 ]. Physical inactivity is a major public health challenge in the developed world and is recognized as a global epidemic [ 8 ]. Within the United States, the rate of childhood obesity is expected to reach 40% in the next two decades [ 9 ] and Type 2 diabetes is expected to affect 300 million people worldwide within the same time [ 10 ].

The UK government has set a target for ‘70% of the population to be reasonably active (for example 30 minutes of moderate exercise five times a week) by 2020’ [ 8 , 11 ] (p. 15). This target could be described as ambitious; only 37% of men and 24% of women in the United Kingdom currently meet this benchmark [ 12 ]. The Health Survey for England (HSE) [ 13 ] found that the number of physically inactive people (less than one occasion of 30-min activity per week) was increasing and that this trend was consistent for both genders and across all age groups [ 14 ]. Conventionally, sport and forms of physical activity such as aerobics, running or gym work have been the focus of efforts to increase population activity levels. The HSE measure includes activities, such as gardening and housework, which are not traditionally considered as physical activity. Sport England found that in the 10-year period between 1987 and 1996 participation in traditional types of sport and physical activity stagnated or fell in all groups other than the 60- to 69-year old age group. This trend was socially patterned by gender, socio-economic status, social class and ethnicity [ 15 ]. There are many broad influences upon physical activity behavior including intra-personal, social, environmental factors and these determinants vary across the life course [ 4 ].

Ambitious national targets and increased funding of community sport and physical activity projects (such as the Sports Hub in Regent's Park, London) [ 16 ] show that sport and physical activity is gaining social, political and health policy importance. The increased interest in physical activity is welcome, but the trend data hints that current interventions to promote sport and physical activity are inadequate. Further, it questions whether the evidence base supporting physical activity policy provides an adequate understanding of the reasons for participation or non-participation in physical activity.

Historically, research into determinants of sport and physical activity participation has tended to adopt quantitative methods, which undertake cross-sectional surveys of pre-determined questions on individual's knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about sport and physical activity. For example, the HSE [ 13 ] asks adults about activity in five domains: activity at work, activity at home (e.g. housework, gardening, do it yourself maintenance (DIY)), walks of ≥15 min and sports and exercise activities. Large studies such as these can successfully assess the direction and strength of trends in participation but are unable to explain how children and adults adopt, maintain or cease to participate in sport and physical activity throughout their lives.

An alternative approach is required which is sensitive to the contextual, social, economic and cultural factors which influence participation in physical activity [ 17 ]. Qualitative methods offer this in-depth insight into individuals' experiences and perceptions of the motives and barriers to participation in sport and physical activity [ 18 ] and are recognized as increasingly important in developing the evidence base for public health [ 19 ]. Although qualitative research is a blanket term for a wide range of approaches, this type of research typically aims to understand the meaning of individual experience within social context. The data for qualitative studies often come from repeated interviews or focus groups, are generally more in-depth and have fewer participants than quantitative research. Additionally, the inductive nature of qualitative research allows for theory to emerge from the lived experiences of research participants rather than the pre-determined hypotheses testing of quantitative approaches.

Thomas and Nelson [ 20 ] describe qualitative methods as the ‘new kid on the block’ in sport and physical activity research and a small body of qualitative research on sport and physical activity in the United Kingdom is known to exist. This paper aims to systematically examine published and unpublished qualitative research studies which have examined UK children's and adults' reasons for participation and non-participation in sport and physical activity.

The review of qualitative research covered the period from 1990 to 2004. This 15-year period was considered adequate to cover the most recent research on barriers and motivation to participation in sport and physical activity. Research papers were sourced in three ways. First, a wide range of electronic databases were searched, including Medline, CINAHL, Index to Thesis, ISI Science Citation Index, ISI Social Science Citation Index, PAIS International, PSYCHINFO, SIGLE and SPORTS-DISCUS. Second, relevant references from published literature were followed up and included where they met inclusion criteria. Third, additional ‘gray’ literature not identified in electronic searches was sourced through individuals who were likely to have knowledge in this area, including librarians and researchers active in the field. This third step ensures inclusion of papers which may not be submitted to peer review journals including reports for government bodies such as Sport England or the Department of Health. Search terms included ‘sports’, ‘dancing’, ‘play’, ‘cycle’, ‘walk’, ‘physical activity’, ‘physical education’ and ‘exercise’.

Papers which met the following criteria were entered into the next phase of the review:

(i) the aim of the study was to explore the participants' experiences of sport and physical activity and reasons for participation or non-participation in sport and physical activity;

(ii) the study collected information on participants who lived in the United Kingdom; and,

(iii) the study presented data collected using qualitative methods.

Two researchers (GC and SA) reviewed each paper independently. Results were compared and discrepancies discussed. Data were extracted using a review schema developed by the research team. In most cases, the original author's own words were used in an attempt to convey the intended meaning and to allow for more realistic comparison between studies.

More than 1200 papers were identified by the initial search strategy. A total of 24 papers were accepted into the final stage of the review, with all but two published during or after 1997. Half of the papers (12) reported research where data were collected in community settings. Of the others, four were set in general physician (GP) referral schemes (in which GPs refer patients to physical activity groups), three in schools, two in sports and leisure clubs and one in a group of three national sports governing bodies. Table I shows that studies described participants by socio-economic status (working class, low income, private or public patient), ethnicity (South Asian and Black in one study, or Scottish, Pakistani, Chinese, Bangladeshi in another) and level of exercise (Elite or other, participant or non-participant).

Participant characteristics

Almost two-thirds of papers (15) did not specify a theoretical framework. Of the nine that did, three used grounded theory, three used a feminist framework, one used figurational sociology, one used gender relations theory and one used Sidentop's model of participation.

The age profile of participants was described in different ways although some grouping was possible ( Table I ). Two studies involved children aged <15 years (5–15 years old and 9–15 years old), seven studies involved research with teenage girls or younger women (aged between 14 and 24 years), 11 related to middle-aged participants (30–65 years) and four reported on adults 50 years or older. The results are organized in two sections: reasons for participation in physical activity and barriers to participation in physical activity. Within each section, results are presented in order of the age group which participated in the study.

Reasons for participation in sport and physical activity

Table II summarizes the main findings of this review. Although most people recognized that there were health benefits associated with physical activity, this was not the main reason for participation. Other factors such as weight management, enjoyment, social interaction and support were more common reasons for people being physically active.

Summary of main findings

Young children

Participation for young children was found to be more enjoyable when children were not being forced to compete and win, but encouraged to experiment with different activities. MacPhail et al. [ 21 ] found providing children with many different types of physical activity and sport-encouraged participation. Enjoyment and support from parents were also crucial [ 22 ]. Parents play a large role in enabling young children opportunities to be physically active and Bostock [ 23 ] found that mothers with young children discouraged their children from playing in an environment perceived as unsafe. Porter [ 24 ] showed that parents are more supportive of activity with easy access, a safe play environment, good ‘drop-off’ arrangements and activities available for other members of the family.

Teenagers and young women

Concerns about body shape and weight management were the main reasons for the participation of young girls. A number of studies [ 25–27 ] reported pressure to conform to popular ideals of beauty as important reasons for teenage girls being physically active. Flintoff and Scraton [ 28 ] interviewed very active girls who described having learnt new skills, increased self-esteem, improved fitness and developed new social networks as motivation to be physically active.

Support from family and significant others at ‘key’ transitional phases (such as changing schools) was essential to maintaining participation [ 29 ]. Those who continued participating through these transitionary periods recalled the importance of positive influences at school in becoming and staying physically active. For girls, having peers to share their active time with was important.

A wide range of adults were studied including patients in GP referral schemes, gay and disabled groups, runners and South Asian and Black communities.

Adults exercise for a sense of achievement, skill development and to spend ‘luxury time’ on themselves away from daily responsibilities [ 30 ]. Non-exercisers recalled negative school experiences as reasons for not participating into middle age [ 31 ].

Studies of GP exercise referral schemes found that the medical sanctioning of programs was a great motivator for participation [ 32 ]. Other benefits reported by referral scheme participants were the social support network created and the general health benefits of being active [ 30 , 33 ].

Among disabled men, exercise provided an opportunity to positively reinterpret their role following a disabling injury [ 34 ]. For this group, displaying and confirming their status as active and competitive was beneficial. Participants in this study described the support network offered by participation as the real value of physical activity and sport. In particular, meeting other disabled men and sharing similar experiences was a key motivator. The building of skills and confidence was another motive for disabled men's participation in sport [ 35 ].

The enjoyment and social networks offered by sport and physical activity are clearly important motivators for many different groups of people aged between 18 and 50 years. The reasons for participation can, however, differ subtly between people within a single group. For example, Smith [ 36 ] interviewed members of a running club and found a distinction between ‘runners’ and ‘joggers’. Runners were elite members of the club and were motivated by intense competition and winning. Conversely, joggers did not consider themselves competitive in races but aimed to better their own previous best time. Joggers were more motivated by the health benefits of running and the increased status afforded to them by non-exercisers who saw them as fit and healthy.

Older adults

Hardcastle and Taylor [ 37 ] suggest that a complex interplay of physical, psychological and environmental factors influence participation among older people. Older adults identified the health benefits of physical activity in terms of reducing the effects of aging and being fit and able to play with grandchildren [ 38 ].

While GP referrals [ 32 , 39 ] encouraged the uptake of exercise in older age groups participation appears to be maintained through enjoyment and strong social networks. This is exemplified by Cooper and Thomas' [ 40 ] study of ballroom dancers in London. Social dancers described dance as helping them challenge the traditional expectations of older people being physically infirm. Participation over time was supported by the flexible nature of ballroom dancing. Different styles of dance provide more or less vigorous forms of activity to suit the skills and limitations of each dancer. Equally important was the social network provided by the weekly social dance encouraging the maintenance of participation across major life events such as bereavement through the support of other dancers in the group. Other studies also highlight the importance of social networks in maintaining participation [ 41 ].

Barriers to participation in sport and physical activity

On a simple level, barriers to participation in physical activity include high costs, poor access to facilities and unsafe environments. Other more complex issues relating to identity and shifting social networks also have a great influence. There were no studies reporting on the barriers to participation in sport and physical activity facing young children.

Negative experiences during school physical activity [physical education (PE)] classes were the strongest factor discouraging participation in teenage girls [ 29 ]. For many girls, impressing boyfriends and other peers was seen as more important than physical activity. While many girls wanted to be physically active, a tension existed between wishing to appear feminine and attractive and the sweaty muscular image attached to active women [ 25 ].

A number of studies [ 27 , 29 , 42 ] showed that tight, ill-fitting PE uniforms were major impediments to girls participating in school sport. These concerns over image and relationships with peers led to an increased interest in non-active leisure.

Flintoff and Scraton [ 28 ] cited the disruptive influence of boys in PE class as another major reason for girls' non-participation. The competitive nature of PE classes and the lack of support for girls from teachers reinforced these problems. Girls were actively marginalized in PE class by boys and many described not being able to get involved in games or even getting to use equipment. Teachers were found to be complicit in this marginalization by not challenging the disruptive behavior of boys in class. Coakley and White [ 29 ] noted that boys were also disruptive out of class and some boys actively discouraged their girlfriends from participating in sport as it made them look ‘butch’. Mulvihill et al. [ 22 ] and Coakley and White [ 29 ] both argue that gender stereotyping has serious negative effects on the participation of girls. Realistic role models for all body types and competency levels were needed rather than the current ‘sporty’ types.

Orme [ 42 ] found that girls were bored by the traditional sports offered in PE. Mulvihill et al. [ 22 ] found that many girls were disappointed with the lack of variety in PE and would rather play sports other than football, rugby and hockey. Being unable to demonstrate competency of a skill to peers in class also made people uncomfortable with PE. Non-traditional activities such as dance were more popular than traditional PE as they provided the opportunity for fun and enjoyment without competition [ 28 ].

Coakley and White [ 29 ] showed that the transition from childhood to adulthood was a key risk time for drop-out. Teenagers did not wish to be associated with activities which they described as ‘childish’ and instead chose activities that were independent and conferred a more adult identity upon them. One participant in this study described leaving a netball team of younger girls because it was ‘babyish’. A number of young women interviewed by these researchers described their belief that ‘adult’ women did not participate in physical activity or sport.

Anxiety and lack of confidence about entering unfamiliar settings such as gyms were the main barriers to participation in GP referral schemes. Not knowing other people, poor body image and not fitting in with the ‘gym’ culture were the prime concerns of this group [ 33 ]. The adults reported in the studies reviewed did not identify with role models used to promote physical activity and people from this age group suggested that realistic exercise leaders would be more effective in encouraging participation [ 41 ]. The lack of realistic role models was also a problem for members of the South Asian and Black community [ 43 ]. This group did not see physical activity as a black or Asian pursuit, but rather as white, middle-class, male domain. The authors argue that there were few opportunities or facilities available to this group.

Self-perception is incredibly important in motivating people to participate in all types of physical activity. The stigma attached to being socially disadvantaged was shown to decrease exercise among low-income women in the Midlands [ 23 ]. Women in this study did not want others to see them walking due to the social stigma attached with not owning a car.

Arthur and Finch's [ 35 ] study of adults with disabilities found that few relevant or positive role models existed. Disabled men reported a lack of knowledge about the appropriate types or levels of activity in relation to their disability. Additionally there were few opportunities to meet other people who were active and disabled. This study also found that the dominance of masculine stereotypes in sport was a particular challenge to participation among gay men. These men expressed concerns about not fitting in and not being one of the ‘lads’. Gay men reported withdrawing from organized sport due to feeling uncomfortable in the associated social situations [ 34 ].

Shaw and Hoeber's [ 44 ] discourse study of three English sports governing bodies reinforced the negative impact of macho culture in sport. Their study found that discourses of masculinity were predominant at all levels of the organization from coaching to senior management. The use of gendered language was shown to actively discourage women from advancing in these organizations. Discourses of femininity (characterized by loyalty, organizational, communicative and human resource skills) were associated with middle and lower management positions compared with masculine discourses (centered on elite coaching, competition and the imperative to win), which were associated with senior organizational roles.

Some older adults were unsure about the ‘right amount’ of physical activity for someone of their age [ 38 ]. As in other age groups, the lack of realistic role models in the community was a deterrent. Exercise prescriptions were perceived as targeted at young people and not relevant to older groups. Porter [ 31 ] found that older people were anxious about returning to physical activity and identified cost and time barriers as the main problems.

This paper has reviewed the qualitative research into the reasons for participation and non-participation of UK adults and children in sport and physical activity. The review covered all qualitative papers relating to sport and physical activity in the United Kingdom from 1990 to 2004.

Although we did find >20 studies, few studies met the basic qualitative research quality criteria of reporting a theoretical framework [ 45 ]. It would appear that little theory is being generated empirically and suggests that any understanding of reasons for participation and non-participation in physical activity in the United Kingdom may be limited.

Shaw and Hoeber [ 44 ] provide one example of the benefits a theoretical framework brings to qualitative research in their analysis of the gendered nature of discourses in three national sporting bodies. Their feminist discourse analysis framework directed the research toward the particular forms of language used in a specific social setting and the implications of this language for marginalizing some groups while supporting the dominance of others. The authors used this framework to show how the masculine discourses used in senior positions actively reduced the career opportunities for women, while men were shown to be actively deterred from regional development officer posts by the feminine discourse surrounding these roles.

Motivations and barriers to participation

Fun, enjoyment and social support for aspects of identity were reported more often as predictors of participation and non-participation than perceived health benefits. For young children and teenage girls in particular, pressure to conform to social stereotypes is a key motivator. Along with older groups, children see enjoyment and social interaction with peers as reasons to be physically active. Although girls report a willingness to be active, this must be on their own terms in a safe non-threatening environment.

A clear opposition can be seen between girls wanting to be physically active and at the same time feminine [ 25 ] and the strong macho culture of school and extracurricular sport [ 46 ]. One area where the evidence base is strong is the negative impact which school PE classes have on participation of young girls. Changing PE uniforms, providing single sex classes and offering alternate, non-competitive forms of PE are easy, realistic ways in which PE could be changed and which the research suggests would improve long-term participation. Additionally, teachers need to take a more active role in ensuring that students are involved and enjoying PE classes. There appears to be some change in this area. The Youth Sports Trust/Nike Girls Project ‘Girls in Sport’ program involved 64 schools across England with the intention of creating ‘girl-friendly’ forms of PE and with changing school practices and community attitudes [ 47 ]. Preliminary results show changes in the style of teaching in PE, ‘girl-friendly’ changing rooms, positive role models for girls in sport, extended and new types of activities, relaxed emphasis on PE kit and an emphasis on rewarding effort as well as achievement.

A number of papers reviewed made the point that the role models for children and young adults are usually beautiful and thin in the case of women and muscular in the case of men. The desire to be thin and, in the case of girls, feminine, leads to increased motivation to be physically active [ 28 ]. This desire is not as strong in older populations and from the mid-20s on, role models with a perfect body have a negative effect on participation [ 43 ].

While the masculine nature of organized and semi-organized sport culture marginalizes women, this review has shown that groups of men are also marginalized. Robertson [ 34 ] has suggested a rethinking of youth sports and in particular the links between sport and masculine identities. Identity formation is a key transition in adolescence, and there is some evidence that physical activity advances identity development. Kendzierski [ 48 ] reported that individuals with an exercise self-schema (self-perception as a physically active person) tended to be active more often and in more types of activity than those with a non-exercise schema (self-perception as not physically active). This relationship between leisure activity and identity may also be dependent on gender and the gendered nature of activities [ 49 ]. Alternate models of sporting clubs, such as those in which children can try a number of traditional and non-traditional sports in one place, could also provide improved take up and maintenance of participation.

Implications for the promotion of sport and physical activity

… throughout the sport and physical activity sector the quality and availability of data on facilities, participation, long term trends, behavioural and other factors is very poor [ 11 ] (p. 14).

Little is known about the reasons why people do and do not participate in physical activity and the relationship between their levels of participation and different stages in their lives. A number of the papers reviewed [ 29 , 34 , 35 ] found that significant shifts in the life course have implications for participation in physical activity. A mix of quantitative and qualitative methods could build an evidence base to understand changes to sport and physical activity at critical transitional phases during childhood, adolescence and adult life. This review provides a starting point for new work.

This review has identified qualitative studies of the reasons for and barriers to participation in sport and physical activity. Participation is motivated by enjoyment and the development and maintenance of social support networks. Barriers to participation include transitions at key stages of the life course and having to reorient individual identities during these times. The theoretical and evidence base informing policy and health promotion is limited and more work needs to be done in this area.

None declared.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

- physical activity

- older adult

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Athl Train

- v.36(2); Apr-Jun 2001

Qualitative Inquiry in Athletic Training: Principles, Possibilities, and Promises

William A. Pitney, EdD, ATC/L, contributed to conception and design and drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the article. Jenny Parker, EdD, contributed to conception and design and critical revision and final approval of the article.

To discuss the principles of qualitative research and provide insights into how such methods can benefit the profession of athletic training.

Background:

The growth of a profession is influenced by the type of research performed by its members. Although qualitative research methods can serve to answer many clinical and professional questions that help athletic trainers navigate their socioprofessional contexts, an informal review of the Journal of Athletic Training reveals a paucity of such methods.

Description:

We provide an overview of the characteristics of qualitative research and common data collection and analysis techniques. Practical examples related to athletic training are also offered.

Applications:

Athletic trainers interact with other professionals, patients, athletes, and administrators and function in a larger society. Consequently, they are likely to face critical influences and phenomena that affect the meaning they give to their experiences. Qualitative research facilitates a depth of understanding related to our contexts that traditional research may not provide. Furthermore, qualitative research complements traditional ways of thinking about research itself and promotes a greater understanding related to specific phenomena. As the profession of athletic training continues to grow, qualitative research methods will assume a more prominent role. Thus, it will be necessary for consumers of athletic training research to understand the functional aspects of the qualitative paradigm.

In a recent publication, Knight and Ingersoll 1 suggested that the growth of the athletic training profession depends in part on the scholarly activity performed by its members. Research, as one form of scholarly activity, plays an essential role in revealing cause and effect, making associations among concepts, making comparisons, gaining insights, guiding decision making, and developing a sound knowledge base. As Weissinger et al 2 stated, one potential influencing factor involved with the development of a body of knowledge in a profession is an expansion of the methods used to collect and analyze data.

An informal appraisal of the past athletic training research in the Journal of Athletic Training reveals that quantitative research methods are currently a widely used form of inquiry. This is certainly not surprising given the scientific nature of the profession and the research questions that have been asked and answered within this paradigm. Although quantitative research has surely contributed to the advancement of knowledge and subsequent health care delivery in athletic training, we must recognize that both researchers and clinicians ask many questions that warrant the use of alternative methods. The purpose of our article, therefore, is to offer a first step in facilitating an understanding of qualitative inquiry within the field of athletic training. This article is divided into 3 main sections. In the first section, we will explain the primary characteristics of qualitative research. The second section focuses on common data collection and data analysis procedures. Finally, in the third section, we will discuss the future directions of qualitative research in athletic training. Throughout this article we will provide practical examples and possibilities, including how qualitative research can inform athletic trainers.

PRIMARY CHARACTERISTICS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

The quantitative research paradigm takes a positivistic stance. That is, this paradigm assumes that a single objective reality exists, 3 which is ascertainable by our senses and logical extensions of our senses 4 (eg, microscopes, electrocardiograms, electromyograms). We can, therefore, measure and observe components of this single reality and test hypotheses about how one component affects another. The qualitative research paradigm, on the other hand, is based on the postmodern philosophical idea that multiple realities exist. Consequently, rather than our world being one objective and measurable entity, it is a subjective phenomenon that needs to be interpreted. 3 The qualitative paradigm recognizes that the meaning people give to situations and phenomena is crucial for understanding a particular context. 5 However, qualitative and quantitative methods are more than just different ways of researching the same items. Rather, they answer different types of questions, have different strengths, and use different techniques. 6

Qualitative researchers are especially concerned with how people develop meaning out of their lived experiences. 7 Moreover, qualitative research is based on the idea that meaning is socially constructed. That is, meaning is created based on personal interactions with others and our environment and the perceptions we give to our lived experiences. Therefore, qualitative researchers rely on a combination of textual data from interviews, conversations, and field notes rather than attempting to reduce meaning to numbers for comparative purposes.

Qualitative research can also be known as naturalistic inquiry, interpretive research, phenomenologic research, ethnography, and even descriptive research. Although qualitative inquiry can be performed in a variety of ways, common tenets are shared in this paradigm. Patton 8 discussed these common tenets as themes of qualitative inquiry. At a fundamental level, Patton 8 stated, qualitative inquiry is based on naturalistic inquiry, a holistic perspective, a focus on processes, inductive analysis, qualitative data, personal insights, case orientation, empathetic neutrality, and flexibility of design.

Qualitative researchers prefer natural or real-world settings. They do not attempt to control variables, manipulate procedures, create research or comparison groups, or isolate a particular phenomenon. Rather, qualitative researchers immerse themselves in a naturally occurring setting to observe and understand it. Thus, qualitative research tends to take a holistic perspective to inquiry. As such, the entire phenomenon under investigation is understood as a complete system rather than isolated events.

Qualitative research is most appropriate for answering questions relative to processes, site-specific phenomena, contexts, programs, or situations in which little is already known. As an example, “by what processes and in what ways have athletic trainers improved health care delivery in a rural school district?” is a question that is best answered using qualitative methods. “What is the economic impact of athletic trainers working in a rural school district?” is best answered using quantitative methods because economic factors are best measured with numbers. 9 An additional example is “in what way does approved clinical instructor status improve the educational delivery to student athletic trainers during their clinical education?” Such a question warrants qualitative methods because the approved clinical instructor programs will be new in the near future and little is known about the influence such programs will have on student learning.

Additionally, qualitative research is flexible and dynamic in that a researcher can choose which data to collect and how during the research process. In fact, qualitative research has metaphorically been compared with jazz music 10 because of the improvisation and flexibility needed to appropriately adapt the methods as findings unfold. Therefore, once researchers initiate a qualitative study and collect data, they need to be prepared to change their procedures and tactics as the process evolves and new insights are gained.

Qualitative research is inductive as opposed to deductive. The researcher begins with specific data and moves toward building general patterns. 8 That is, whereas an experimental design requires that a hypothesis be stated before the study in an attempt to either prove or disprove it, a qualitative study allows various dimensions to unfold or emerge, thus permitting hypotheses to become a product of the research. Moreover, qualitative inquiry is interpretive in that a researcher gathers a large amount of data with the intent of theorizing about the problem or phenomenon under investigation. Qualitative methods are a fundamental research strategy for many of the social sciences, including sociology and anthropology. Although qualitative research is derived from various epistemologic, philosophical, and methodologic traditions, 8 at its foundation are phenomenology and symbolic interactionism. 3

Phenomenology focuses on an individual's experience, how people create their view of the world around them, and how they interact with their environment. 11 Researchers using a phenomenologic approach seek both a rich description of a context and a depth of understanding and meaning related to specific phenomena but from the participants' perspectives. 12 In athletic training, for example, such an approach could be used to address a phenomenon related to rehabilitation noncompliance, practitioner burnout, or nontraditional student experiences in an athletic training education program. As a more specific example, practitioner burnout could be investigated qualitatively to identify stress-coping strategies. Thus, practitioners could share their perspectives and describe how they attempted to cope with stress in a specific context. Such a qualitative investigation may uncover contextual issues that facilitated the burnout process.

Symbolic interactionism is a reaction to psychology's focus on intrinsic factors (eg, motivation or stress) and sociology's emphasis on extrinsic factors (eg, social class and structure) causing a specific behavior. 13 According to Blumer, 13 the symbolic interactionist framework suggested that (1) human beings act toward objects based on the meaning that the items have for them, (2) meaning is a product of social interaction in our society, and (3) the attribution of meaning to objects through symbols is a continuous interpretive process. An example of using a symbolic interactionist's framework in athletic training is examining the professional socialization process of various contexts (eg, intercollegiate athletics, high school, or professional ranks). Additionally, such questions as how medical decisions are made in a clinical context or how athletic trainers in various subcultures develop professionally over time are potential research topics that could be addressed from the symbolic interactionist perspective. At its foundation, however, qualitative inquiry is interpretive, relies on inductive analysis, and is concerned with the meaning created by participants. The Table identifies the key differences between qualitative and quantitative research.

Comparison of Qualitative and Quantitative Research Attributes

QUALITATIVE DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

As with any research project involving human participants, a qualitative researcher must receive approval from an institutional review board. The review board ensures that the data collection and data analysis procedures protect the participants' anonymity. This is accomplished by giving any participants, institutions, or programs a pseudonym before any portion of the report is published. Qualitative researchers collect data in many ways, including interviews, observations, document analysis, artifacts (eg, photographs, videotapes, and tools), and surveys. Interviews and observations, however, are 2 of the most commonly used methods of gathering data in qualitative research. The following section will explain the observation and interview process and then describe how the textual data are analyzed.

OBSERVATION

Qualitative researchers often immerse themselves in a particular context and observe participants. Observation involves recording interactions among subjects, various events, a participant's behavior, and even a description of the context by taking field notes. 11 , 14 Such observations allow the qualitative researcher not only to recognize the essence of a context but also to identify particular behavior patterns and meanings.

Observation can be participatory or nonparticipatory. With participant observation, a qualitative researcher becomes involved in the actual activity being studied. For example, an athletic training researcher interested in understanding the contextual influences and dynamics of patient interaction within the professional ranks might volunteer with a professional team during practices. During this time, the researcher could not only provide health care services (ie, participate in the setting) but also observe the natural setting to further understand the dynamics involved. Nonparticipatory involvement means that the researcher does not participate in the activity while obtaining data. Rather, he or she watches a phenomenon in its natural setting.

Interviews are conducted when a researcher needs to understand factors that cannot be observed. 8 For example, for a study conducted to gain insight into and understanding of why particular athletes play through pain, interviews would be necessary because the athlete's thoughts, feelings, and perceptions cannot be observed.

Interviews are also conducted when information about past events needs to be obtained. For example, a researcher investigating the professional socialization of intercollegiate athletic trainers may attempt to learn about the initial experiences and challenges they faced when first entering their work environment. Obviously, these experiences and challenges are not observable, so participants would need to be asked to reflect on these past events.

An interview can take many forms, including an unstructured, semistructured, or structured format. 3 , 12 Generally, however, a semistructured format is most commonly used 12 and directed by an interview guide. That is, based on the research question, an interview guide is designed to formulate a list of questions related to specific phenomena. A less structured interview guide is often preferred because it assumes that interviewees will explain, characterize, and define their contexts in unique ways. 3 Regardless of the type of interview conducted, the conversation is recorded (with the participant's permission) and transcribed. The data are then considered textual and the written words can be analyzed.

DATA ANALYSIS

Qualitative data analysis is interpretive in nature. Harris 15 reviewed the literature regarding interpretive research and identified 3 levels of interpretation that are necessary for drawing appropriate conclusions. First, the project must be grounded in the collective understandings of the culture created among the participants. Second, the project must include the researcher's insights. Third, the project must be well linked to other research. Harris 15 added that combining interpretations at each of these 3 levels into an integrated whole is paramount in qualitative research. The researcher interviews and observes participants (or specific behaviors if watching videotapes of social interactions) and then examines the data for meaning. We must make clear, however, that with qualitative research, the data analysis is a continuous and ongoing activity that occurs simultaneously with data collection. From the moment the first interview is conducted or the first observation is made, the researcher obtains a deeper understanding of the phenomenon being studied and may, accordingly, make modifications and adjustments to the data collection techniques.

Qualitative researchers have a preference for grounded theory, that is, developing theory based on the data obtained in a study. 16 According to Strauss and Corbin, 17 textual data are initially analyzed by creating concepts and categories. The researcher reads a sentence or paragraph and then gives this incident a name or label that represents it. These conceptual statements are then reviewed and grouped into categories according to their similarities. This is similar to Lincoln and Guba's 18 process of identifying units of data, such as sentences, paragraphs, or comments, that can provide information about a particular concept in and of itself. These “units of data” are then categorized according to their similarities with other units. The following is a useful sequence based on the literature 3 , 4 , 6 , 12 that helps a reader to understand how qualitative data are analyzed. Qualitative data analysis involves (1) identifying meaningful concepts (meaning condensation), (2) grouping similar concepts together (meaning categorization), (3) labeling groups of concepts (defining the categories), (4) developing theory, (5) negatively testing the theory, and (6) comparing the theory with the relevant literature.

Initially, the transcripts and observation notes are read and a participant's meaningful statements are identified, rephrased, and abridged. For example, if a student athletic trainer hypothetically suggested in an interview that he or she “spends a great deal of time each day having student-athletes tell them about their frustrations,” this could be labeled as “listening.” Therefore, meaning is condensed, and larger portions of text are reduced and made more succinct. 12 Essentially, the concepts identified are then considered to be units of data.

Once various concepts are identified and condensed, they are compared with one another. At this time, the like concepts are grouped together into categories. The various categories, or groups of concepts, are then given labels that describe the categories. For example, using the hypothetical situation above, if a researcher had several different concepts from interviews with student athletic trainers, such as “listening,” “giving advice,” and “empathizing,” these could be categorized as “student athletic trainers' social support schemes.” The researcher then examines the categories and interprets their relationship, subsequently creating a tentative theory. As Thomas and Nelson 19 stated, the researcher attempts to “merge” categories into a holistic portrayal of the phenomenon under investigation.

The generated theory, however, must then be negatively analyzed. This means that the generated theory is tested for its plausibility. For example, after conducting 3 interviews and observing student athletic trainers for 4 weeks, a researcher identified and documented a particular sequence of social support schemes displayed by the participants. It would be necessary for this researcher to investigate the experiences of other student athletic trainers in the same or similar contexts to determine whether the theory or explanatory concepts are applicable. Moreover, a negative case analysis involves being skeptical about findings and searching for alternative explanations that link the various categories. Once the theory is developed, it is then compared with the related literature.

Although the data analysis can be done by hand using concepts printed on note cards, many computerized data analysis programs are currently available to qualitative researchers. Examples include the NUD*IST (Non-numerical, Unstructured Data require ways of Indexing, Searching and Theorizing) program, produced by QSR International (Melbourne, Australia), and The Ethnograph, produced by Qualis Research Associates (Amherst, MA). These programs offer qualitative researchers a structured database to organize concepts and categories and quickly find units of data in the transcripts.

Qualitative research is based on human interest and actively seeks to fully understand human behavior by becoming close to those being studied to expose factors that may not be identified with instruments or surveys. 8 Moreover, qualitative research tends to humanize data, problems, and issues, 20 presupposing that a phenomenon cannot be understood without empathy and introspection. 8 The researcher, however, is the primary data collection and data analysis instrument and is capable of extreme sensitivity and flexibility with regard to thoughtfully examining and organizing the data. Quantitative research, alternatively, attempts to be objective through blind experiments and collecting data with instruments that do not rely on human sensitivity. 8 A qualitative researcher's intimate involvement with participants and data often prompts the questions of researcher bias and how the reader of a qualitative research study can trust the interpretation of data.

Although quantitative research would be concerned with aspects of validity and reliability of data collection and analysis, these terms are not typically used in qualitative research. Rather, qualitative researchers are concerned with the “trustworthiness” or “authenticity” of the study. Trustworthiness of a qualitative study can be established in many ways, including triangulation, 4 , 6 , 11 peer reviews, and member checks. 3

Triangulation refers to a researcher's cross-checking information from multiple perspectives. This can entail using different investigators, different methods (ie, observations and interviews), or even different data sources. 8 Using the previous example, if a researcher was gathering data related to student athletic trainer's social support schemes, it would be wise to interview not only student athletic trainers but also student athletes, supervising staff, and clinical educators. Thus, there are multiple sources from which to collect data and subsequently triangulate the findings to ensure that the findings are accurate and make sense in a given context.

Peer review requires that a highly skilled external researcher examine the transcripts, concepts, and categories generated from the study. The examination is performed to ensure that the study was performed in a logical manner and that the insights and discoveries uncovered in the investigation are credible. A member check refers to the qualitative researcher's sharing the initial results of the study with a few participants and asking them to examine the findings relative to their own experiences to ensure that the findings are plausible from the participants' perspectives.

Although quantitative studies concern themselves with sample size, this is not the case with qualitative research. Because a goal of quantitative studies is to attempt to generalize, large sample sizes are desirable. Qualitative research seeks to gain insight and understanding about particular phenomena, cases, processes, or programs. As such, qualitative research may be conducted with one participant or multiple participants, depending on the context or phenomenon under investigation.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND POSSIBILITIES IN ATHLETIC TRAINING

Many professions have affirmed the value and impact that qualitative inquiry can have on professional practice. In fact, many journals have committed to publishing qualitative research projects. Examples relative to athletic training include Qualitative Health Research, Social Science and Medicine, The Gerontologist, Family Medicine, Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, Advanced Nursing Science, 21 Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, Sociology of Sport Journal, International Review of Sport Sociology, and the British Medical Journal. Although athletic training is largely a scientific field of study, we must recognize the potential promise qualitative research offers to help us further understand our professional roles in a social context.

The delivery of patient care is itself a social act that results in many interactions, which create shared meanings. 15 Athletic trainers associate with other professionals, patients, athletes, and administrators and, therefore, function in a larger society. Moreover, we cannot divorce ourselves from our context and the influences that affect us as health care providers. Consequently, we are likely to face critical influences and phenomena that affect the meaning we create. Qualitative research can facilitate a better understanding of phenomena and allow athletic trainers to better navigate their socioprofessional environments.

Arguments about whether quantitative or qualitative research has more merit have raged for many years 19 and have produced many debates and propositions. An either-or relationship, however, should not exist between qualitative and quantitative methods because, as we have discussed in this article, they answer different types of questions that facilitate an understanding of our professional roles and responsibilities. In many instances, a study can use both quantitative and qualitative methods in a mixed-methods approach. As an example, Hughes et al 22 used a mixed-methods approach to study the appeal of designer drinks among young people. These authors conducted group interviews (focus groups) to explore attitudes related to drinking and then used the qualitative results to inform the development of the questionnaire for the quantitative portion of the study. Furthermore, when a quantitative study uncovers a nuance or unexpected finding related to the human condition, a qualitative analysis could be integrated to gain a better understanding of the situation. The idea of combining methods, however, is not without debate. The multimethod approach is often contended because of the broad theoretical differences. 23

When both the quantitative and qualitative paradigms are understood, valued, and sometimes integrated, the breadth and depth of knowledge in athletic training can expand and positively influence the lives of patients, clinicians, educators, and student athletic trainers. We have written this article to provide an initial step toward a better understanding of the basic principles of qualitative research for the readership of the Journal of Athletic Training. For a more comprehensive understanding of the qualitative research paradigm, we direct those interested to investigate the references and suggested readings listed below.

SUGGESTED READINGS

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 October 2018

A qualitative investigation of the role of sport coaches in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health

- Louise Mansfield ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4332-4366 1 ,

- Tess Kay 1 ,

- Nana Anokye 2 &

- Julia Fox-Rushby 3

BMC Public Health volume 18 , Article number: 1196 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

7578 Accesses

12 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Community sport can potentially help to increase levels of physical activity and improve public health. Sport coaches have a role to play in designing and implementing community sport for health. To equip the community sport workforce with the knowledge and skills to design and deliver sport and empower inactive participants to take part, this study delivered a bespoke training package on public health and recruiting inactive people to community sport for sport coaches. We examined the views of sport coach participants about the training and their role in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with paid full-time sport coaches ( n = 15) and community sport managers and commissioners ( n = 15) with expertise in sport coaching. Interviews were conducted by a skilled interviewer with in-depth understanding of community sport and sport coach training, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis.

Three key themes were identified showing how the role of sport coaches can be maximised in designing and delivering community sport for physical activity and health outcomes, and in empowering participants to take part. The themes were: (1) training sport coaches in understanding public health, (2) public involvement in community sport for health, and (3) building collaborations between community sport and public health sectors.

Training for sport coaches is required to develop understandings of public health and skills in targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people to community sport. Public involvement in designing community sport is significant in empowering inactive people to take part. Ongoing knowledge exchange activities between the community sport and public health sector are also required in ensuring community sport can increase physical activity and improve public health.

Peer Review reports

Regular physical activity is significant in the prevention and treatment of physical and mental health conditions including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, some cancers, anxiety and depression [ 1 ]. Worldwide, the prevalence of physical activity at recommended levels is low. Current estimates in the UK are that approximately 20 million adults (39%) are categorised as inactive because they fail to meet the recommended guidelines for physical activity of 150 min per week of moderate intensity physical activity and strength exercise on at least 2 days [ 2 ]. Increasing population levels of physical activity can potentially improve public health. In England, the Moving More, Living More cross Government group includes representation from national lead agencies, Sport England, the Department of Health and Public Health England and recognises the role that sport can play in helping people to become more active for improved health outcomes [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. This perspective reflects more recent debates about the potential of low intensity physical activity for improving health which challenge established physical activity for health guidelines emphasising moderate and vigorous intensity phyiscal activity [ 6 ].

Successive Sport England strategies have focused on developing sporting opportunites tailored to the needs of diverse communities of local users. With devolvement of public health priorities to local authorities in April 2013, there is a heightened significance of locally based initiatives and the role of complex community interventions for public health outcomes; those that involve several interlocking components important to successful delivery [ 7 , 8 ]. Community-centred interventions can have a positive impact on health behaviours [ 9 , 10 ]. Successful community-based health interventions are associated with extensive formative research, participatory strategies and a theoretical and practical focus on changing social norms [ 11 ].

Sport coaches have a vital role to play in changing social norms around sports through individual and community engagement and empowering or enabling participants to take part in physical activity [ 12 ]. Empowerment theory provides a useful theoretical approach for understanding the complexities of raising physical activity levels through community sport. At the community level, empowerment theory investigates people’s capacity to influence organisations and institutions which impact on their lives [ 13 , 14 ]. The theory addresses the processes by which personal and social factors of life enable and constrain behaviours, and this provides the theoretical basis of this study.

There are 1,109, 000 sport coaches in the UK primarily working in sports clubs or extra-curricular school-based programmes, with much of their expertise focused on beginners and learners and sport enthusiasts [ 15 ]. Sports coaches represent community assets in the development of sport for health programmes for inactive adults who may be apprehensive rather than enthusiastic about taking part in sport [ 12 ], yet little is known about the occupational drivers, priorities and requirements of this workforce. There is potential for them to be a resource for identifying and assessing inactive people and providing physical activity education, promotion and support in local public health environments; a role more commonly associated with routine care in GP surgeries and health centres [ 16 , 17 ]. The potential of sports clubs as a health promotion setting has been recognised [ 18 , 19 ]. Key issues have been identified in developing successful approaches to health promotion in sports clubs including the need for clear health focused strategies, adapting sports activity, ensuring a health promoting environment, enabling learning opportunities about sport for health and workforce training in public health [ 20 ]. Knowledge and skill development in the sport coach workforce is imperative to equip it to design, deliver and evaluate community sport opportunities for public health outcomes [ 21 ]. Most recent models for such workforce development advocate partnership approaches between sport and leisure providers, public health professionals and the participants for whom community sport programmes are designed and delivered [ 22 ]. The aim of this paper is to explore the role of sport coaches in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health.

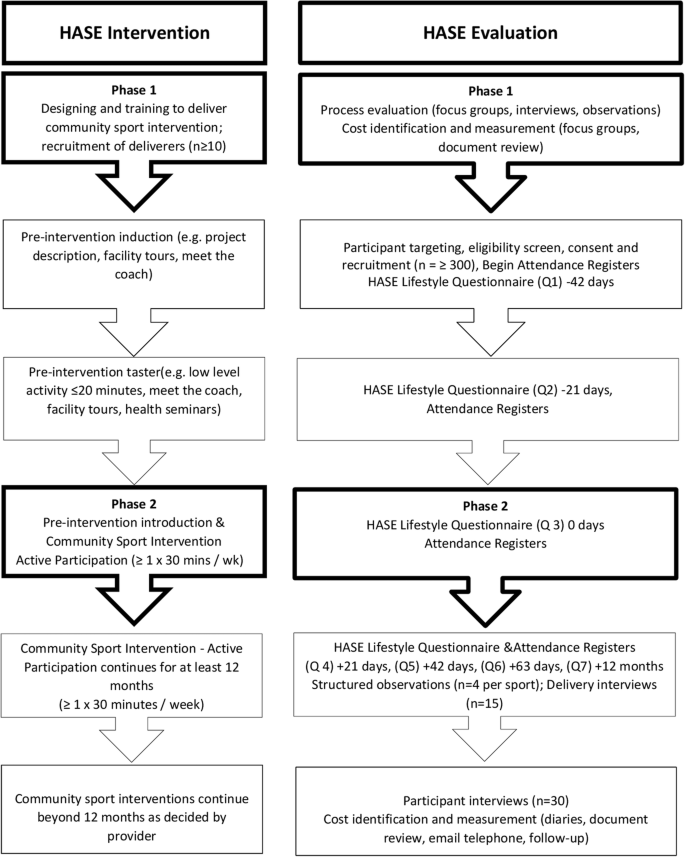

Background to the study – The health and sport engagement (HASE) project

Between March 2013 and July 2016, 32 sport coaches delivering and managing community sport in the London Borough of Hounslow were involved in a complex community sport intervention; the Health and Sport Engagement (HASE) project. The aim of the HASE project was to engage previously inactive people in sustained sporting activity for 1 × 30 min a week, examine the associated health and wellbeing outcomes of doing so, and produce information of value to those commissioning public health programmes that could potentially include sport. Full details of the HASE project are provided in the published protocol [ 23 ]. A summary of the HASE project intervention and evaluation phases is provided in Fig. 1 .

The Health and Sport Engagement (HASE) Study overview

Design and delivery of the HASE intervention involved a collaborative partnership between local community participants, sport coaches and community sport managers/ commissioners in the London Borough of Hounslow (LBH), and sport and public health researchers at Brunel University London. Coaches were key stakeholders in the project which employed a collaborative approach to stakeholder engagement, involving them in the initial project ideas development prior to the funding application, and in formative discussions about relevant training and the content and scheduling of training. Training served not only as a form of education and skill development but as a space for on-going involvement of coaches in the co-design [ 24 ] of the training programme, the precise nature of the sport activities and their delivery and evaluation approaches.

During a 12-month delivery phase, community sport coaches delivered 682 sport sessions to 550 people in the HASE project. Community sport coaches with expertise and experience in delivering and managing sport activities and with knowledge of diverse local communities were identified as central to the successful design and implementation of community sport for inactive people. A bespoke HASE training programme was included to identify existing expertise and additional skills and knowledge requirements of community sport coaches in designing and implementing community sport for health. The HASE training schedule for sport coaches consisted of two elements:

To develop understandings of public health for sport coaches, training included The Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) Level 2 Award in Understanding Health Improvement, and workshops on targeting, promoting and retaining inactive people to sport ( http://makesportfun.com/ ), and disability, inclusion and sport ( https://disabilitysportscoach.co.uk/training-workshops/ ).

To address the need for cross sector collaboration and partnership between local sport and public health groups, sports coaches and public health professionals attended a bespoke knowledge exchange workshop on getting to know and understand the roles and working practices of personnel in each sector ( http://makesportfun.com/ ).

Between March–September 2013, 32 community sport coaches were trained in the RSPH Level 2 Award in the first phase of the HASE project. Fifteen of those sport coaches were paid and full-time and they also engaged in training about targeting, recruiting and retaining inactive people in community sport and an on-line disability in sport course. Fourteen of those additionally attended knowledge exchange activities between sport coaches and public health professionals (1 coach was unavailable due to work commitments). Knowledge exchange activities included demonstrations of adapted sports activities, a ‘meet and greet’ event in which coaches and health professionals were paired to talk and exchange professional information, then paired with another expert at 5-min intervals, and a discussion forum about the strategy and mechanism of local authority public health referral scheme.

The HASE project included a mixed methods evaluation of the outcomes, processes and costs of the complex community sport intervention. Process evaluations are recommended in examining the efficacy of complex interventions and have value in multisite projects where the same interventions are tailored to the specific contexts and delivered and received in diverse ways [ 25 ]. Process evaluations using qualitative methods can complement research designs that assess effectiveness and efficiency quantitatively [ 26 ], by providing in-depth knowledge from those delivering and receiving the interventions. Evaluating the design, implementation, mechanisms of impact, and contextual factors that create different intervention effects can support the development of optimal complex community interventions and contribute to decision making about whether it is feasible to proceed to a larger scale trial [ 27 ]. This study presents findings from the interviews with sport coaches and community sport managers or commissioners with expertise in sport coaching which formed part of the process evaluation in the HASE project.

Data collection

Taking a pragmatic approach to evaluation to ensure timely, practice relevant yet rigorous research [ 28 ] the 15 sport coaches who had been trained in the RSPH Level 2 Award, attended the workshops and completed the on-line disability in sport course were invited for interview. All but one of those had also attended the knowledge exchange workshops with public health professionals. Fifteen community sport managers or commissioners with knowledge of sport coaching and involved in developing the HASE intervention and evaluation were also invited to interview. Thirty telephone interviews were conducted with paid full-time sport coaches ( n = 15) and community sport managers and commissioners ( n = 15) with expertise in sport coaching.

Semi structured interviews were conducted by one researcher (LM) for consistency of questioning. The aims of these interviews were twofold: (1) to examine the aspirations and logic underpinning design, delivery, promotion, and commissioning of sport for health projects, and (2) to examine the experiences and views of the HASE training. The interview guide can be found in Additional file 1 . The interview data helped to determine the role of the sports coach in designing and delivering a complex community sport intervention for increasing physical activity and improving health. In this paper direct quotes are included in the results and respondents referred to by gender, self-reported job and coaching role and years of experience (YE).