The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter, DNP, APRN, ACNS-BC, CNE

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

- ACN FOUNDATION

- SIGNATURE EVENTS

- SCHOLARSHIPS

- POLICY & ADVOCACY

- ACN MERCHANDISE

- MYACN LOGIN

- THE BUZZ LOGIN

- STUDENT LOGIN

- ACN governance and structure

- Work at ACN

- Contact ACN

- NurseClick – ACN’s blog

- Media releases

- Publications

- ACN podcast

- Men in Nursing

- NurseStrong

- Recognition of Service

- Free eNewsletter

- Areas of study

- Graduate Certificates

- Nursing (Re-entry)

- Preparation for Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE)

- Continuing Professional Development

- Immunisation courses

- Single units of study

- Transition to Practice Program

- Refresher programs

- Principles of Emergency Care

- Medicines Management Course

- Professional Practice Course

- Endorsements

- Student support

- Student policies

- Clinical placements

- Career mentoring

- Indemnity insurance

- Legal advice

- ACN representation

- Affiliate membership

- Undergraduate membership

- Retired membership

- States and Territories

- ACN Fellowship

- Referral discount

- Health Minister’s Award for Nursing Trailblazers

- Emerging Nurse Leader program

- Emerging Policy Leader Program

- Emerging Research Leader Program

- Nurse Unit Manager Leadership Program

- Nurse Director Leadership Program

- Nurse Executive Leadership Program

- The Leader’s Series

- Nurse Executive Capability Framework

- Thought leadership

- Other leadership courses

- National Nurses Breakfast

- National Nursing Forum

- History Faculty Conference

- Next Generation Faculty Summit

- Let’s Talk Leadership

- Virtual Open Day

- National Nursing Roadshow

- Policy Summit

- Nursing & Health Expo

- Event and webinar calendar

- Grants and awards

- First Nations health scholarships

- External nursing scholarships

- Assessor’s login

- ACN Advocacy and Policy

- Position Statements

- Submissions

- White Papers

- Aged Care Solutions Expert Advisory Group

- Nurses and Violence Taskforce

- Parliamentary Friends of Nursing

- Aged Care Transition to Practice Program

- Our affiliates

- Immunisation

- Join as an Affiliated Organisation

- Our Affiliates

- Our Corporate Partners

- Events sponsorship

- Advertise with us

- Career Hub resources

- Critical Thinking

Q&A: What is critical thinking and when would you use critical thinking in the clinical setting?

(Write 2-3 paragraphs)

In literature ‘critical thinking’ is often used, and perhaps confused, with problem-solving and clinical decision-making skills and clinical reasoning. In practice, problem-solving tends to focus on the identification and resolution of a problem, whilst critical thinking goes beyond this to incorporate asking skilled questions and critiquing solutions.

Critical thinking has been defined in many ways, but is essentially the process of deliberate, systematic and logical thinking, while considering bias or assumptions that may affect your thinking or assessment of a situation. In healthcare, the clinical setting whether acute care sector or aged care critical thinking has generally been defined as reasoned, reflective thinking which can evaluate the given evidence and its significance to the patient’s situation. Critical thinking occasionally involves suspension of one’s immediate judgment to adequately evaluate and appraise a situation, including questioning whether the current practice is evidence-based. Skills such as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation are required to interpret thinking and the situation. A lack of critical thinking may manifest as a failure to anticipate the consequences of one’s actions.

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them.

The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought.

Critical thinking can be defined as, “the art of analysing and evaluating thinking with a view to improving it”. The eight Parts or Elements of Thinking involved in critical thinking:

- All reasoning has a purpose (goals, objectives).

- All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem .

- All reasoning is based on assumptions (line of reasoning, information taken for granted).

- All reasoning is done from some point of view.

- All reasoning is based on data, information and evidence .

- All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas .

- All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data.

- All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequence.

Q&A: To become a nurse requires that you learn to think like a nurse. What makes the thinking of a nurse different from a doctor, a dentist or an engineer?

It is how we view the health care consumer or aged care consumer, and the type of problems nurses deal with in clinical practice when we engage in health care patient centred care. To think like a nurse requires that we learn the content of nursing; the ideas, concepts, ethics and theories of nursing and develop our intellectual capacities and skills so that we become disciplined, self-directed, critical thinkers.

As a nurse you are required to think about the entire patient/s and what you have learnt as a nurse including; ideas, theories, and concepts in nursing. It is important that we develop our skills so that we become highly proficient critical thinkers in nursing.

In nursing, critical thinkers need to be:

Nurses need to use language that will clearly communicate a lot of information that is key to good nursing care, for handover and escalation of care for improving patient safety and reducing adverse outcomes, some organisations use the iSoBAR (identify–situation–observations–background–agreed plan–read back) format. Firstly, the “i”, for “identify yourself and the patient”, placed the patient’s identity, rather than the diagnosis, in primary position and provided a method of introduction. (This is particularly important when teams are widely spread geographically.) The prompt, “S” (“situation”) “o” for “observations”, was included to provide an adequate baseline of factual information on which to devise a plan of care. and “B” (“background”), “A” “agreed plan” and “R” “read back” to reinforce the transfer of information and accountability.

In clinical practice experienced nurses engage in multiple clinical reasoning episodes for each patient in their care. An experienced nurse may enter a patient’s room and immediately observe significant data, draw conclusions about the patient and initiate appropriate care. Because of their knowledge, skill and experience the expert nurse may appear to perform these processes in a way that seems automatic or instinctive. However, clinical reasoning is a learnt skill.

Key critical thinking skills – the clinical reasoning cycle / critical thinking process

To support nursing students in the clinical setting, breakdown the critical thinking process into phases;

- Decide/identify

This is a dynamic process and nurses often combine one or more of the phases, move back and forth between them before reaching a decision, reaching outcomes and then evaluating outcomes.

For nursing students to learn to manage complex clinical scenarios effectively, it is essential to understand the process and steps of clinical reasoning. Nursing students need to learn rules that determine how cues shape clinical decisions and the connections between cues and outcomes.

Start with the Patient – what is the issue? Holistic approach – describe or list the facts, people.

Collect information – Handover report, medical and nursing, allied health notes. Results, patient history and medications.

- New information – patient assessment

Process Information – Interpret- data, signs and symptoms, normal and abnormal.

- Analyse – relevant from non-relevant information, narrow down the information

- Evaluate – deductions or form opinions and outcomes

Identify Problems – Analyse the facts and interferences to make a definitive diagnosis of the patients’ problem.

Establish Goals – Describe what you want to happen, desired outcomes and timeframe.

Take action – Select a course of action between alternatives available.

Evaluate Outcomes – The effectiveness of the actions and outcomes. Has the situation changed or improved?

Reflect on process and new learning – What have you learnt and what would you do differently next time.

Scenario: Apply the clinical reasoning cycle, see below, to a scenario that occurred with a patient in your clinical practice setting. This could be the doctor’s orders, the patient’s vital signs or a change in the patient’s condition.

(Write 3-5 paragraphs)

Important skills for critical thinking

Some skills are more important than others when it comes to critical thinking. The skills that are most important are:

- Interpreting – Understanding and explaining the meaning of information, or a particular event.

- Analysing – Investigating a course of action, that is based upon data that is objective and subjective.

- Evaluating – This is how you assess the value of the information that you have. Is the information relevant, reliable and credible?

This skill is also needed to determine if outcomes have been fully reached.

Based upon those three skills, you can use clinical reasoning to determine what the problem is.

These decisions have to be based upon sound reasoning:

- Explaining – Clearly and concisely explaining your conclusions. The nurse needs to be able to give a sound rationale for their answers.

- Self-regulating – You have to monitor your own thought processes. This means that you must reflect on the process that lead to the conclusion. Be on alert for bias and improper assumptions.

Critical thinking pitfalls

Errors that occur in critical thinking in nursing can cause incorrect conclusions. This is particularly dangerous in nursing because an incorrect conclusion can lead to incorrect clinical actions.

Illogical Processes

A common illogical thought process is known as “appeal to tradition”. This is what people are doing when they say it’s always been done like this. Creative, new approaches are not tried because of tradition.

All people have biases. Critical thinkers are able to look at their biases and not let them compromise their thinking processes.

Biases can complicate decision making, communication and ultimately effect patient care.

Closed Minded

Being closed-minded in nursing is dangerous because it ignores other team members points of view. Essential input from other experts, as well as patients and their families are also ignored which ultimately impacts on patient care. This means that fewer clinical options are explored, and fewer innovative ideas are used for critical thinking to guide decision making.

So, no matter if you are an intensive care nurse, community health nurse or a nurse practitioner, you should always keep in mind the importance of critical thinking in the nursing clinical setting.

It is essential for nurses to develop this skill: not only to have knowledge but to be able to apply knowledge in anticipation of patients’ needs using evidence-based care guidelines.

American Management Association (2012). ‘AMA 2012 Critical Skills Survey: Executive Summary’. (2012). American Management Association. http://playbook.amanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/2012-Critical-Skills-Survey-pdf.pdf Accessed 5 May 2020.

Korn, M. (2014). ‘Bosses Seek ‘Critical Thinking,’ but What Is That?,’ The Wall Street Journal . https://www.wsj.com/articles/bosses-seek-critical-thinking-but-what-is-that-1413923730?tesla=y&mg=reno64-wsj&url=http://online.wsj.com/article/SB12483389912594473586204580228373641221834.html#livefyre-comment Accessed 5 May 2020.

School of Nursing and Midwifery Faculty of Health, University of Newcastle. (2009). Clinical reasoning. Instructors resources. https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/86536/Clinical-Reasoning-Instructor-Resources.pdf Accessed 11 May 2020

The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing + Examples. Nurse Journal social community for nurses worldwide. 2020. https://nursejournal.org/community/the-value-of-critical-thinking-in-nursing/ Accessed 8 May 2020.

Paul And Elder (2009) Have Defined Critical Thinking As: The Art of Analysing And Evaluating …

https://www.chegg.com/homework-help/questions-and-answers/paul-elder-2009-defined-critical-thinking-art-analyzing-evaluating-thinking-view-improving-q23582096 Accessed 8 May 2020 .

Cody, W.K. (2002). Critical thinking and nursing science: judgment, or vision? Nursing Science Quarterly, 15(3), 184-189.

Facione, P. (2011). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assessment , ISBN 13: 978-1-891557-07-1.

McGrath, J. (2005). Critical thinking and evidence- based practice. Journal of Professional Nursing, 21(6), 364-371.

Porteous, J., Stewart-Wynne, G., Connolly, M. and Crommelin, P. (2009). iSoBAR — a concept and handover checklist: the National Clinical Handover Initiative. Med J Aust 2009; 190 (11): S152.

Related posts

Planning your career 5 November 2021

Active Listening 4 November 2021

Ethical Leadership 4 November 2021

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 07 October 2020

Impact of social problem-solving training on critical thinking and decision making of nursing students

- Soleiman Ahmady 1 &

- Sara Shahbazi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8397-6233 2 , 3

BMC Nursing volume 19 , Article number: 94 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

22 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The complex health system and challenging patient care environment require experienced nurses, especially those with high cognitive skills such as problem-solving, decision- making and critical thinking. Therefore, this study investigated the impact of social problem-solving training on nursing students’ critical thinking and decision-making.

This study was quasi-experimental research and pre-test and post-test design and performed on 40 undergraduate/four-year students of nursing in Borujen Nursing School/Iran that was randomly divided into 2 groups; experimental ( n = 20) and control (n = 20). Then, a social problem-solving course was held for the experimental group. A demographic questionnaire, social problem-solving inventory-revised, California critical thinking test, and decision-making questionnaire was used to collect the information. The reliability and validity of all of them were confirmed. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software and independent sampled T-test, paired T-test, square chi, and Pearson correlation coefficient.

The finding indicated that the social problem-solving course positively affected the student’ social problem-solving and decision-making and critical thinking skills after the instructional course in the experimental group ( P < 0.05), but this result was not observed in the control group ( P > 0.05).

Conclusions

The results showed that structured social problem-solving training could improve cognitive problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making skills. Considering this result, nursing education should be presented using new strategies and creative and different ways from traditional education methods. Cognitive skills training should be integrated in the nursing curriculum. Therefore, training cognitive skills such as problem- solving to nursing students is recommended.

Peer Review reports

Continuous monitoring and providing high-quality care to patients is one of the main tasks of nurses. Nurses’ roles are diverse and include care, educational, supportive, and interventional roles when dealing with patients’ clinical problems [ 1 , 2 ].

Providing professional nursing services requires the cognitive skills such as problem-solving, decision-making and critical thinking, and information synthesis [ 3 ].

Problem-solving is an essential skill in nursing. Improving this skill is very important for nurses because it is an intellectual process which requires the reflection and creative thinking [ 4 ].

Problem-solving skill means acquiring knowledge to reach a solution, and a person’s ability to use this knowledge to find a solution requires critical thinking. The promotion of these skills is considered a necessary condition for nurses’ performance in the nursing profession [ 5 , 6 ].

Managing the complexities and challenges of health systems requires competent nurses with high levels of critical thinking skills. A nurse’s critical thinking skills can affect patient safety because it enables nurses to correctly diagnose the patient’s initial problem and take the right action for the right reason [ 4 , 7 , 8 ].

Problem-solving and decision-making are complex and difficult processes for nurses, because they have to care for multiple patients with different problems in complex and unpredictable treatment environments [ 9 , 10 ].

Clinical decision making is an important element of professional nursing care; nurses’ ability to form effective clinical decisions is the most significant issue affecting the care standard. Nurses build 2 kinds of choices associated with the practice: patient care decisions that affect direct patient care and occupational decisions that affect the work context or teams [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ].

The utilization of nursing process guarantees the provision of professional and effective care. The nursing process provides nurses with the chance to learn problem-solving skills through teamwork, health management, and patient care. Problem-solving is at the heart of nursing process which is why this skill underlies all nursing practices. Therefore, proper training of this skill in an undergraduate nursing program is essential [ 17 ].

Nursing students face unique problems which are specific to the clinical and therapeutic environment, causing a lot of stresses during clinical education. This stress can affect their problem- solving skills [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. They need to promote their problem-solving and critical thinking skills to meet the complex needs of current healthcare settings and should be able to respond to changing circumstances and apply knowledge and skills in different clinical situations [ 22 ]. Institutions should provide this important opportunity for them.

Despite, the results of studies in nursing students show the weakness of their problem-solving skills, while in complex health environments and exposure to emerging diseases, nurses need to diagnose problems and solve them rapidly accurately. The teaching of these skills should begin in college and continue in health care environments [ 5 , 23 , 24 ].

It should not be forgotten that in addition to the problems caused by the patients’ disease, a large proportion of the problems facing nurses are related to the procedures of the natural life of their patients and their families, the majority of nurses with the rest of health team and the various roles defined for nurses [ 25 ].

Therefore, in addition to above- mentioned issues, other ability is required to deal with common problems in the working environment for nurses, the skill is “social problem solving”, because the term social problem-solving includes a method of problem-solving in the “natural context” or the “real world” [ 26 , 27 ]. In reviewing the existing research literature on the competencies and skills required by nursing students, what attracts a lot of attention is the weakness of basic skills and the lack of formal and systematic training of these skills in the nursing curriculum, it indicates a gap in this area [ 5 , 24 , 25 ]. In this regard, the researchers tried to reduce this significant gap by holding a formal problem-solving skills training course, emphasizing the common social issues in the real world of work. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the impact of social problem-solving skills training on nursing students’ critical thinking and decision-making.

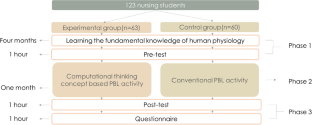

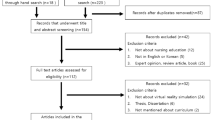

Setting and sample

This quasi-experimental study with pretest and post-test design was performed on 40 undergraduate/four-year nursing students in Borujen nursing school in Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. The periods of data collection were 4 months.

According to the fact that senior students of nursing have passed clinical training and internship programs, they have more familiarity with wards and treatment areas, patients and issues in treatment areas and also they have faced the problems which the nurses have with other health team personnel and patients and their families, they have been chosen for this study. Therefore, this study’s sampling method was based on the purpose, and the sample size was equal to the total population. The whole of four-year nursing students participated in this study and the sample size was 40 members. Participants was randomly divided in 2 groups; experimental ( n = 20) and control (n = 20).

The inclusion criteria to take part in the present research were students’ willingness to take part, studying in the four-year nursing, not having the record of psychological sickness or using the related drugs (all based on their self-utterance).

Intervention

At the beginning of study, all students completed the demographic information’ questionnaire. The study’s intervening variables were controlled between the two groups [such as age, marital status, work experience, training courses, psychological illness, psychiatric medication use and improving cognitive skills courses (critical thinking, problem- solving, and decision making in the last 6 months)]. Both groups were homogeneous in terms of demographic variables ( P > 0.05). Decision making and critical thinking skills and social problem solving of participants in 2 groups was evaluated before and 1 month after the intervention.

All questionnaires were anonymous and had an identification code which carefully distributed by the researcher.

To control the transfer of information among the students of two groups, the classification list of students for internships, provided by the head of nursing department at the beginning of semester, was used.

Furthermore, the groups with the odd number of experimental group and the groups with the even number formed the control group and thus were less in contact with each other.

The importance of not transferring information among groups was fully described to the experimental group. They were asked not to provide any information about the course to the students of the control group.

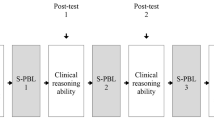

Then, training a course of social problem-solving skills for the experimental group, given in a separate course and the period from the nursing curriculum and was held in 8 sessions during 2 months, using small group discussion, brainstorming, case-based discussion, and reaching the solution in small 4 member groups, taking results of the social problem-solving model as mentioned by D-zurilla and gold fried [ 26 ]. The instructor was an assistant professor of university and had a history of teaching problem-solving courses. This model’ stages are explained in Table 1 .

All training sessions were performed due to the model, and one step of the model was implemented in each session. In each session, the teacher stated the educational objectives and asked the students to share their experiences in dealing to various workplace problems, home and community due to the topic of session. Besides, in each session, a case-based scenario was presented and thoroughly analyzed, and students discussed it.

Instruments

In this study, the data were collected using demographic variables questionnaire and social problem- solving inventory – revised (SPSI-R) developed by D’zurilla and Nezu (2002) [ 26 ], California critical thinking skills test- form B (CCTST; 1994) [ 27 , 28 ] and decision-making questionnaire.

SPSI-R is a self - reporting tool with 52 questions ranging from a Likert scale (1: Absolutely not – 5: very much).

The minimum score maybe 25 and at a maximum of 125, therefore:

The score 25 and 50: weak social problem-solving skills.

The score 50–75: moderate social problem-solving skills.

The score higher of 75: strong social problem-solving skills.

The reliability assessed by repeated tests is between 0.68 and 0.91, and its alpha coefficient between 0.69 and 0.95 was reported [ 26 ]. The structural validity of questionnaire has also been confirmed. All validity analyses have confirmed SPSI as a social problem - solving scale.

In Iran, the alpha coefficient of 0.85 is measured for five factors, and the retest reliability coefficient was obtained 0.88. All of the narratives analyzes confirmed SPSI as a social problem- solving scale [ 29 ].

California critical thinking skills test- form B(CCTST; 1994): This test is a standard tool for assessing the basic skills of critical thinking at the high school and higher education levels (Facione & Facione, 1992, 1998) [ 27 ].

This tool has 34 multiple-choice questions which assessed analysis, inference, and argument evaluation. Facione and Facione (1993) reported that a KR-20 range of 0.65 to 0.75 for this tool is acceptable [ 27 ].

In Iran, the KR-20 for the total scale was 0.62. This coefficient is acceptable for questionnaires that measure the level of thinking ability of individuals.

After changing the English names of this questionnaire to Persian, its content validity was approved by the Board of Experts.

The subscale analysis of Persian version of CCTST showed a positive high level of correlation between total test score and the components (analysis, r = 0.61; evaluation, r = 0.71; inference, r = 0.88; inductive reasoning, r = 0.73; and deductive reasoning, r = 0.74) [ 28 ].

A decision-making questionnaire with 20 questions was used to measure decision-making skills. This questionnaire was made by a researcher and was prepared under the supervision of a professor with psychometric expertise. Five professors confirmed the face and content validity of this questionnaire. The reliability was obtained at 0.87 which confirmed for 30 students using the test-retest method at a time interval of 2 weeks. Each question had four levels and a score from 0.25 to 1. The minimum score of this questionnaire was 5, and the maximum score was 20 [ 30 ].

Statistical analysis

For analyzing the applied data, the SPSS Version 16, and descriptive statistics tests, independent sample T-test, paired T-test, Pearson correlation coefficient, and square chi were used. The significant level was taken P < 0.05.

The average age of students was 21.7 ± 1.34, and the academic average total score was 16.32 ± 2.83. Other demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2 .

None of the students had a history of psychiatric illness or psychiatric drug use. Findings obtained from the chi-square test showed that there is not any significant difference between the two groups statistically in terms of demographic variables.

The mean scores in social decision making, critical thinking, and decision-making in whole samples before intervention showed no significant difference between the two groups statistically ( P > 0.05), but showed a significant difference after the intervention ( P < 0.05) (Table 3 ).

Scores in Table 4 showed a significant positive difference before and after intervention in the “experimental” group ( P < 0.05), but this difference was not seen in the control group ( P > 0.05).

Among the demographic variables, only a positive relationship was seen between marital status and decision-making skills (r = 0.72, P < 0.05).

Also, the scores of critical thinking skill’ subgroups and social problem solving’ subgroups are presented in Tables 5 and 6 which showed a significant positive difference before and after intervention in the “experimental” group (P < 0.05), but this difference was not seen in the control group ( P > 0.05).

In the present study conducted by some studies, problem-solving and critical thinking and decision-making scores of nursing students are moderate [ 5 , 24 , 31 ].

The results showed that problem-solving skills, critical thinking, and decision-making in nursing students were promoted through a social problem-solving training course. Unfortunately, no study has examined the effect of teaching social problem-solving skills on nursing students’ critical thinking and decision-making skills.

Altun (2018) believes that if the values of truth and human dignity are promoted in students, it will help them acquire problem-solving skills. Free discussion between students and faculty on value topics can lead to the development of students’ information processing in values. Developing self-awareness increases students’ impartiality and problem-solving ability [ 5 ]. The results of this study are consistent to the results of present study.

Erozkan (2017), in his study, reported there is a significant relationship between social problem solving and social self-efficacy and the sub-dimensions of social problem solving [ 32 ]. In the present study, social problem -solving skills training has improved problem -solving skills and its subdivisions.

The results of study by Moshirabadi (2015) showed that the mean score of total problem-solving skills was 89.52 ± 21.58 and this average was lower in fourth-year students than other students. He explained that education should improve students’ problem-solving skills. Because nursing students with advanced problem-solving skills are vital to today’s evolving society [ 22 ]. In the present study, the results showed students’ weakness in the skills in question, and holding a social problem-solving skills training course could increase the level of these skills.

Çinar (2010) reported midwives and nurses are expected to use problem-solving strategies and effective decision-making in their work, using rich basic knowledge.

These skills should be developed throughout one’s profession. The results of this study showed that academic education could increase problem-solving skills of nursing and midwifery students, and final year students have higher skill levels [ 23 ].

Bayani (2012) reported that the ability to solve social problems has a determining role in mental health. Problem-solving training can lead to a level upgrade of mental health and quality of life [ 33 ]; These results agree with the results obtained in our study.

Conducted by this study, Kocoglu (2016) reported nurses’ understanding of their problem-solving skills is moderate. Receiving advice and support from qualified nursing managers and educators can enhance this skill and positively impact their behavior [ 31 ].

Kashaninia (2015), in her study, reported teaching critical thinking skills can promote critical thinking and the application of rational decision-making styles by nurses.

One of the main components of sound performance in nursing is nurses’ ability to process information and make good decisions; these abilities themselves require critical thinking. Therefore, universities should envisage educational and supportive programs emphasizing critical thinking to cultivate their students’ professional competencies, decision-making, problem-solving, and self-efficacy [ 34 ].

The study results of Kirmizi (2015) also showed a moderate positive relationship between critical thinking and problem-solving skills [ 35 ].

Hong (2015) reported that using continuing PBL training promotes reflection and critical thinking in clinical nurses. Applying brainstorming in PBL increases the motivation to participate collaboratively and encourages teamwork. Learners become familiar with different perspectives on patients’ problems and gain a more comprehensive understanding. Achieving these competencies is the basis of clinical decision-making in nursing. The dynamic and ongoing involvement of clinical staff can bridge the gap between theory and practice [ 36 ].

Ancel (2016) emphasizes that structured and managed problem-solving training can increase students’ confidence in applying problem-solving skills and help them achieve self-confidence. He reported that nursing students want to be taught in more innovative ways than traditional teaching methods which cognitive skills training should be included in their curriculum. To this end, university faculties and lecturers should believe in the importance of strategies used in teaching and the richness of educational content offered to students [ 17 ].

The results of these recent studies are adjusted with the finding of recent research and emphasize the importance of structured teaching cognitive skills to nurses and nursing students.

Based on the results of this study on improving critical thinking and decision-making skills in the intervention group, researchers guess the reasons to achieve the results of study in the following cases:

In nursing internationally, problem-solving skills (PS) have been introduced as a key strategy for better patient care [ 17 ]. Problem-solving can be defined as a self-oriented cognitive-behavioral process used to identify or discover effective solutions to a special problem in everyday life. In particular, the application of this cognitive-behavioral methodology identifies a wide range of possible effective solutions to a particular problem and enhancement the likelihood of selecting the most effective solution from among the various options [ 27 ].

In social problem-solving theory, there is a difference among the concepts of problem-solving and solution implementation, because the concepts of these two processes are different, and in practice, they require different skills.

In the problem-solving process, we seek to find solutions to specific problems, while in the implementation of solution, the process of implementing those solutions in the real problematic situation is considered [ 25 , 26 ].

The use of D’zurilla and Goldfride’s social problem-solving model was effective in achieving the study results because of its theoretical foundations and the usage of the principles of cognitive reinforcement skills. Social problem solving is considered an intellectual, logical, effort-based, and deliberate activity [ 26 , 32 ]; therefore, using this model can also affect other skills that need recognition.

In this study, problem-solving training from case studies and group discussion methods, brainstorming, and activity in small groups, was used.

There are significant educational achievements in using small- group learning strategies. The limited number of learners in each group increases the interaction between learners, instructors, and content. In this way, the teacher will be able to predict activities and apply techniques that will lead students to achieve high cognitive taxonomy levels. That is, confront students with assignments and activities that force them to use cognitive processes such as analysis, reasoning, evaluation, and criticism.

In small groups, students are given the opportunity to the enquiry, discuss differences of opinion, and come up with solutions. This method creates a comprehensive understanding of the subject for the student [ 36 ].

According to the results, social problem solving increases the nurses’ decision-making ability and critical thinking regarding identifying the patient’s needs and choosing the best nursing procedures. According to what was discussed, the implementation of this intervention in larger groups and in different levels of education by teaching other cognitive skills and examining their impact on other cognitive skills of nursing students, in the future, is recommended.

Social problem- solving training by affecting critical thinking skills and decision-making of nursing students increases patient safety. It improves the quality of care because patients’ needs are better identified and analyzed, and the best solutions are adopted to solve the problem.

In the end, the implementation of this intervention in larger groups in different levels of education by teaching other cognitive skills and examining their impact on other cognitive skills of nursing students in the future is recommended.

Study limitations

This study was performed on fourth-year nursing students, but the students of other levels should be studied during a cohort from the beginning to the end of course to monitor the cognitive skills improvement.

The promotion of high-level cognitive skills is one of the main goals of higher education. It is very necessary to adopt appropriate approaches to improve the level of thinking. According to this study results, the teachers and planners are expected to use effective approaches and models such as D’zurilla and Goldfride social problem solving to improve problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making skills. What has been confirmed in this study is that the routine training in the control group should, as it should, has not been able to improve the students’ critical thinking skills, and the traditional educational system needs to be transformed and reviewed to achieve this goal.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

California critical thinking skills test

Social problem-solving inventory – revised

Pesudovs L. Medical/surgical nursing in the home. Aust Nurs Midwifery J. 2014;22(3):24.

PubMed Google Scholar

Szeri C, et al. Problem solving skills of the nursing and midwifery students and influential factors. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem. 2010;12(4).

Friese CR, et al. Pod nursing on a medical/surgical unit: implementation and outcomes evaluation. J Nurs Adm. 2014;44(4):207–11.

Article Google Scholar

Lyneham J. A conceptual model for medical-surgical nursing: moving toward an international clinical specialty. Medsurg Nurs. 2013;22(4):215–20 263.

Altun I. The perceived problem solving ability and values of student nurses and midwives. Nurse Educ Today. 2003;23(8):575–84.

Deniz Kocoglu R, et al. Problem solving training for first line nurse managers. Int J Caring Sci. 2016;9(3):955.

Google Scholar

Mahoney C, et al. Implementing an 'arts in nursing' program on a medical-surgical unit. Medsurg Nurs. 2011;20(5):273–4.

Pardue SF. Decision-making skills and critical thinking ability among associate degree, diploma, baccalaureate, and master's-prepared nurses. J Nurs Educ. 1987;26(9):354–61.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kozlowski D, et al. The role of emotion in clinical decision making: an integrative literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):255.

Kuiper RA, Pesut DJ. Promoting cognitive and metacognitive reflective reasoning skills in nursing practice: self-regulated learning theory. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(4):381–91.

Huitzi-Egilegor JX, et al. Implementation of the nursing process in a health area: models and assessment structures used. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(5):772–7.

Lauri S. Development of the nursing process through action research. J Adv Nurs. 1982;7(4):301–7.

Muller-Staub M, de Graaf-Waar H, Paans W. An internationally consented standard for nursing process-clinical decision support Systems in Electronic Health Records. Comput Inform Nurs. 2016;34(11):493–502.

Neville K, Roan N. Challenges in nursing practice: nurses' perceptions in caring for hospitalized medical-surgical patients with substance abuse/dependence. J Nurs Adm. 2014;44(6):339–46.

Rabelo-Silva ER, et al. Advanced nursing process quality: comparing the international classification for nursing practice (ICNP) with the NANDA-international (NANDA-I) and nursing interventions classification (NIC). J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(3–4):379–87.

Varcoe C. Disparagement of the nursing process: the new dogma? J Adv Nurs. 1996;23(1):120–5.

Ancel G. Problem-solving training: effects on the problem-solving skills and self-efficacy of nursing students. Eurasian J Educ Res. 2016;64:231–46.

Fang J, et al. Social problem-solving in Chinese baccalaureate nursing students. J Evid Based Med. 2016;9(4):181–7.

Kanbay Y, Okanli A. The effect of critical thinking education on nursing students' problem-solving skills. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53(3):313–21.

Lau Y. Factors affecting the social problem-solving ability of baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(1):121–6.

Terzioglu F. The perceived problem-solving ability of nurse managers. J Nurs Manag. 2006;14(5):340–7.

Moshirabadi, Z., et al., The perceived problem solving skill of Iranian nursing students . 2015.

Cinar N. Problem solving skills of the nursing and midwifery students and influential factors. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem. 2010;12(4):601–6.

Moattari M, et al. Clinical concept mapping: does it improve discipline-based critical thinking of nursing students? Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19(1):70–6.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Elliott TR, Grant JS, Miller DM. Social Problem-Solving Abilities and Behavioral Health. In Chang EC, D'Zurilla TJ, Sanna LJ, editors. Social problem solving: Theory, research, and training. American Psychological Association; 2004. p. 117–33.

D'Zurilla TJ, Maydeu-Olivares A. Conceptual and methodological issues in social problem-solving assessment. Behav Ther. 1995;26(3):409–32.

Facione PA. The California Critical Thinking Skills Test--College Level. Technical Report# 1. Experimental Validation and Content Validity; 1990.

Khalili H, Zadeh MH. Investigation of reliability, validity and normality Persian version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test; Form B (CCTST). J Med Educ. 2003;3(1).

Mokhberi A. Questionnaire, psychometrics, and standardization of indicators of social problem solving ability. Educ Measurement. 2011;1(4):1–21.

Heidari M, Shahbazi S. Effect of training problem-solving skill on decision-making and critical thinking of personnel at medical emergencies. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2016;6(4):182–7.

Kocoglu D, Duygulu S, Abaan S, Akin B. Problem Solving Training for First Line Nurse Managers. Int J Caring Sci. 2016;9(13):955–65.

Erozkan A. Analysis of social problem solving and social self-efficacy in prospective teachers. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice. 2014;14(2):447–55.

Bayani AA, Ranjbar M, Bayani A. The study of relationship between social problem-solving and depression and social phobia among students. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2012;22(94):91–8.

Kashaninia Z, et al. The effect of teaching critical thinking skills on the decision making style of nursing managers. J Client-Centered Nurs Care. 2015;1(4):197–204.

Kirmizi FS, Saygi C, Yurdakal IH. Determine the relationship between the disposition of critical thinking and the perception about problem solving skills. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;191:657–61.

Hung CH, Lin CY. Using concept mapping to evaluate knowledge structure in problem-based learning. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:212.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This article results from research project No. 980 approved by the Research and Technology Department of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. We would like to appreciate to all personnel and students of the Borujen Nursing School. The efforts of all those who assisted us throughout this research.

‘Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medical Education, Virtual School of Medical Education and Management, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Soleiman Ahmady

Virtual School of Medical Education and management, Shahid Beheshty University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Sara Shahbazi

Community-Oriented Nursing Midwifery Research Center, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SA and SSH conceptualized the study, developed the proposal, coordinated the project, completed initial data entry and analysis, and wrote the report. SSH conducted the statistical analyses. SA and SSH assisted in writing and editing the final report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sara Shahbazi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was reviewed and given exempt status by the Institutional Review Board of the research and technology department of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences (IRB No. 08–2017-109). Before the survey, students completed a research consent form and were assured that their information would remain confidential. After the end of the study, a training course for the control group students was held.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ahmady, S., Shahbazi, S. Impact of social problem-solving training on critical thinking and decision making of nursing students. BMC Nurs 19 , 94 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00487-x

Download citation

Received : 11 March 2020

Accepted : 29 September 2020

Published : 07 October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00487-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social problem solving

- Decision making

- Critical thinking

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Critical Thinking

Building Creative Thinking Skills

Lumen Learning

Creative Thinking

Think about a time when you visited a museum or a sculpture garden, or you attended an orchestral performance or a concert by a favorite performer. Did you marvel at the skill, the artistry, and the innovation? Did you imagine how wonderful it must feel to have those abilities?

If you’ve ever had thoughts like this, you must know you’re not alone. It’s hard for anyone to behold a great work of art or performance and not imagine standing, even briefly, in the artist’s shoes.

But when you’ve admired creative works or creative people, have you acknowledged the seeds of creativity within yourself?

You might be surprised to know that everyone has creative abilities: It’s true of everyone who fully expresses creative abilities as well as those who express them very little or not at all. All humans are innately creative, especially if creativity is understood as a problem-solving skill.

Put another way, creativity is inspired when there is a problem to solve. For example, when a sculptor creates an amazing sculpture, it’s an act of problem-solving: perhaps she must determine which artistic style to use in order to create the likeness of an object, or perhaps she is deciding which tools will most suit her purpose or style, perhaps she is assessing how best to satisfy a customer’s request or earn income from her art—you get the idea. In every case, the problem sparks the sculptor’s creativity and she brings her creativity to bear in finding an artistic solution.

Considered as an act of problem-solving, creativity can be understood as a skill —as opposed to an inborn talent or natural “gift”—that can be taught as well as learned. Problem-solving is something we are called upon to do every day, from performing mundane chores to executing sophisticated projects. The good news is that we can always improve upon our problem-solving and creative-thinking skills—even if we don’t consider ourselves to be artists or “creative.” The following information may surprise and encourage you!

- Creative thinking (a companion to critical thinking) is an invaluable skill for college students . It’s important because it helps you look at problems and situations from a fresh perspective. Creating thinking is a way to develop novel or unorthodox solutions that do not depend wholly on past or current solutions. It’s a way of employing strategies to clear your mind so that your thoughts and ideas can transcend what appear to be the limitations of a problem. Creative thinking is a way of moving beyond barriers. [1]

- As a creative thinker, you are curious, optimistic, and imaginative. You see problems as interesting opportunities, and you challenge assumptions and suspend judgment. You don’t give up easily. You work hard. [2]

Is this you? Even if you don’t yet see yourself as a competent creative thinker or problem-solver, you can learn solid skills and techniques to help you become one.

How to Stimulate Creative Thinking

The following video, How to Stimulate the Creative Process , identifies six strategies to stimulate your creative thinking.

- Sleep on it. Over the years, researchers have found that the REM sleep cycle boosts our creativity and problem-solving abilities, providing us with innovative ideas or answers to vexing dilemmas when we awaken. Keep a pen and paper by the bed so you can write down your nocturnal insights if they wake you up.

- Go for a run or hit the gym. Studies indicate that exercise stimulates creative thinking, and the brainpower boost lasts for a few hours.

- Allow your mind to wander a few times every day. Far from being a waste of time, daydreaming has been found to be an essential part of generating new ideas. If you’re stuck on a problem or creatively blocked, think about something else for a while.

- Keep learning. Studying something far removed from your area of expertise is especially effective in helping you think in new ways.

- Put yourself in nerve-racking situations once in a while to fire up your brain. Fear and frustration can trigger innovative thinking.

- Keep a notebook with you so you always have a way to record fleeting thoughts. They’re sometimes the best ideas of all.

- Image of throwing a pot. Authored by : Sterling College. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/qFFeQG . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Creative Thinking Skills. Provided by : Fostering Creativity and Critical Thinking with Technology. Located at : https://creativecriticalthinking.wikispaces.com/Creative+Thinking . License : Other . License Terms : GNU Free Documentation License

- Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom. Authored by : Thomas C. Priester, editor. Provided by : Open SUNY Textbooks. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/foundations-of-academic-success/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- How to Stimulate the Creative Process. Authored by : Howcast. Located at : https://youtu.be/kPC8e-Jk5uw . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Media Attributions

- Mumaw, Stefan. "Born This Way: Is Creativity Innate or Learned?" Peachpit. Pearson, 27 Dec 2012. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- Harris, Robert. "Introduction to Creative Thinking." Virtual Salt. 2 Apr 2012. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

About the Author

name: Lumen Learning

Building Creative Thinking Skills Copyright © 2021 by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Rev Bras Enferm

- v.76(4); 2023

- PMC10561938

Language: English | Portuguese | Spanish

Clinical supervision strategies, learning, and critical thinking of nursing students

Estrategias de supervisión clínica, aprendizaje y pensamiento crítico de los estudiantes de enfermería, estratégias de supervisão clínica, aprendizagem e pensamento crítico dos estudantes de enfermagem, angélica oliveira veríssimo da silva.

I Universidade de Aveiro, Departamento de Educação e Psicologia. Aveiro, Portugal

António Luís Rodrigues Faria de Carvalho

II Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Porto. Porto, Portugal

Rui Marques Vieira

Cristina maria correia barroso pinto, associated data.

https://doi.org/10.48331/scielodata.PC3XOX

To identify the supervisory strategies that Nursing students consider facilitators of the development of critical thinking skills in clinical teaching.

This is a qualitative study, within the interpretative paradigm, using the focus group methodology. Eight undergraduate nursing students participated in the study.

Participants recognized the indispensability of critical thinking for professional responsibility and quality of care and highlighted the importance of using supervisory strategies adapted to their needs, learning objectives, and the context of clinical practice.

Final considerations:

This study highlights the urgent need to establish, within the Nursing curricula, clinical supervision strategies that promote critical thinking and favor the development of skills for good clinical judgment, problem solving, and safe, effective, and ethical decision-making.

Identificar as estratégias supervisivas que os estudantes de Enfermagem consideram facilitadoras do desenvolvimento das capacidades de pensamento crítico no contexto de ensino clínico.

Métodos:

Estudo de natureza qualitativa, inserido no paradigma interpretativo, com recurso à metodologia focus group . Participaram do estudo oito estudantes do curso de licenciatura em Enfermagem.

Resultados:

Os participantes reconheceram a imprescindibilidade do pensamento crítico para a responsabilidade profissional e qualidade na assistência; e destacaram a importância da utilização de estratégias supervisivas adequadas às suas necessidades, aos objetivos de aprendizagem e ao contexto da prática clínica.

Considerações finais:

Este estudo sobreleva a premência em se estabelecer, dentro dos currículos do curso de Enfermagem, estratégias de supervisão clínica promotoras do pensamento crítico, que favoreçam o desenvolvimento de capacidades para o bom julgamento clínico, resolução de problemas e tomada de decisão segura, eficaz e ética.

Identificar las estrategias de supervisión que los estudiantes de Enfermería consideran facilitadoras del desarrollo de las capacidades de pensamiento crítico en el contexto de enseñanza clínica.

Estudio de naturaleza cualitativa, inserido en el paradigma interpretativo, con recurso a la metodología focus group . Participaron del estudio ocho estudiantes del curso de licenciatura en Enfermería.

Los participantes reconocieron la imprescindibilidad del pensamiento crítico para la responsabilidad profesional y calidad en la asistencia; y destacaron la importancia de la utilización de estrategias de supervisión adecuadas a sus necesidades, a los objetivos de aprendizaje y al contexto de la práctica clínica.

Consideraciones finales:

Este estudio sobrepasa la urgencia en establecerse, dentro de los currículos del curso de Enfermería, estrategias de supervisión clínica promotoras del pensamiento crítico, que favorezcan el desarrollo de capacidades para el bueno juicio clínico, resolución de problemas y toma de decisión segura, eficaz y ética.

INTRODUCTION

The complex challenges that globalization imposes incorporate the need to establish critical thinking (CT) as a pillar today. It is the duty of educational institutions to prepare their students adequately so that they can provide timely and appropriate answers to the diverse and emerging problems that society and patients impose on them ( 1 ) . Critical thinking, as a set of skills and dispositions, has sparked the interest of the scientific community and of national and international organizations ( 2 - 3 ) . In recent years, efforts have been made to incorporate it into the curricula in different educational institutions.

Widely studied in the last decades, CT can be defined as intentional, rational, and reflective thinking, focused on what one should believe and do ( 4 ) , which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation ( 5 ) . It is considered essential for the development of the ability to process information and evaluate its plausibility, to clearly argue and defend one’s position, to foresee consequences, to examine the pros and cons in the decision-making process ( 6 - 7 ) . Being able to think critically is evidenced as an important predictor of good academic performance ( 8 ) . Students with high CT skills are capable of organizing their learning, monitor and evaluate their performance ( 9 ) , and such skills favor successful decision making ( 8 ) .

Like globalization, health care has also become complex and demanding; nursing has evolved as a profession, a fact that has generated the need for professionals to demonstrate critical-reflexive characteristics in their daily practice ( 10 ) . Nursing as a profession is configured as the largest workforce in health care, both by the number of professionals and by its proximity to patients and their families, because it is the nursing professionals who ensure 24 hours of patient care. This proximity and all the complexity involved in nursing care, along with technological advances, require skills that allow nurses to provide safe and quality care ( 11 - 15 ) .

In the context of health care, CT can be defined as the rigorous, intentional, and result-focused reasoning based on the patient’s needs ( 16 ) . For the promotion of safe and quality care, nursing students should be trained in a reflective manner to be able to act and respond assertively to the complex tangle of issues that emerge from the clinical context in the face of dynamic, uncertain, unpredictable, and inconstant situations ( 15 , 17 ) . Thus, CT skills are considered essential components for professional responsibility and quality in nursing care ( 11 - 12 , 14 , 16 , 18 - 19 ) .

Thinking critically is not innate, so it requires effort and integration of contexts and teaching and learning proposals that favor its evolution ( 20 ) . For the development of CT skills, it is important to ensure learning environments that enable the active involvement of students ( 21 ) , since active learning methodologies can stimulate the development of higher order cognitive processes ( 12 , 15 , 22 - 23 ) . Active learning methodologies are considered the key to success that guarantees students the ability to analyze evidence and proposals, make fair judgments, propose solutions ( 22 , 24 - 25 ) , evaluate their decisions and, if necessary, go back to the start and reconstruct the whole process ( 26 ) .

Thus, the clinical teaching context constitutes the space of choice for the development of CT skills due to its dynamic, interactive, unpredictable, mediating, facilitating, and enhancing nature of practical learning ( 27 - 28 ) . Clinical teaching, performed in health institutions, is characterized by learning in real context, where the student applies theoretical knowledge in practice, that is, it integrates knowing with doing, resulting in a reflective and critical process and in the improvement of clinical skills and competencies that, when properly conducted, culminates in a conscious, critical, and creative student action ( 11 , 29 - 30 ) . Clinical teaching, through the supervisory process, aims to guarantee the student the acquisition of knowledge and the development of skills and attitudes for the performance of autonomous, conscious, and grounded interventions ( 29 - 31 ) .

It is possible to state that CT, as a set of skills, can be taught, and the more these skills are trained, the greater the probability of favorable results, which contributes to the training of students capable of providing assertive answers to the complex problems presented ( 5 , 22 , 32 ) . Critical teaching, due to its real-world nature, favors the development of these abilities (professional competencies), since it enables the articulation between theory and practice, enhanced by the adoption of a proactive learning attitude ( 29 ) . Clinical supervision strategies (CSS) can influence the development of nursing students’ CT skills, which are essential for their performance in care practice.

Currently, there are several studies that address CT issues ( 1 - 6 , 8 , 19 , 32 ) in a general manner and others more directed to nursing ( 18 , 21 - 22 , 26 ) ; however, there are still no studies relating supervision strategies to the development of CT in nursing students. Based on the premise that CT is a fundamental aspect during the critical teaching of these students, the adoption of constructivist teaching strategies that allow them to improve CT learning should be encouraged. In this sense, it is essential to identify the students’ CT skills and the CSSs that most promote their development.

To identify the supervisory strategies that Nursing students consider facilitators of the development of CT skills in clinical teaching.

Ethical aspects

This study was submitted to the opinion of the Ethics Committee of a Nursing School in Northern Portugal, and its ethical and methodological aspects were approved. All study participants signed the Informed Consent Form, which guarantees the right to data privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality.

Theoretical and methodological framework

The theoretical and methodological framework is based on the qualitative approach. This seeks to interpret and understand a reality from the perspective of the actors involved in the process ( 33 ) .