- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

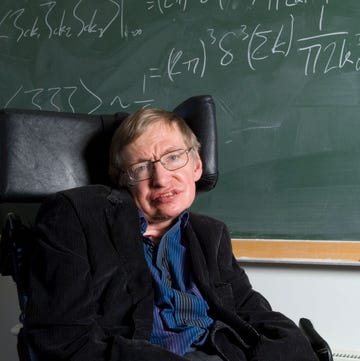

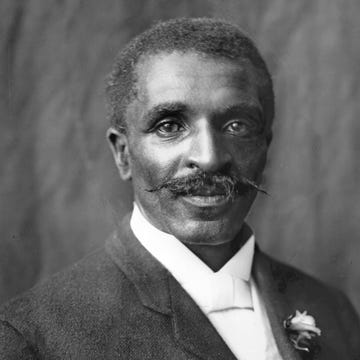

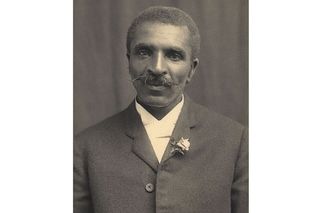

George Washington Carver

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 24, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

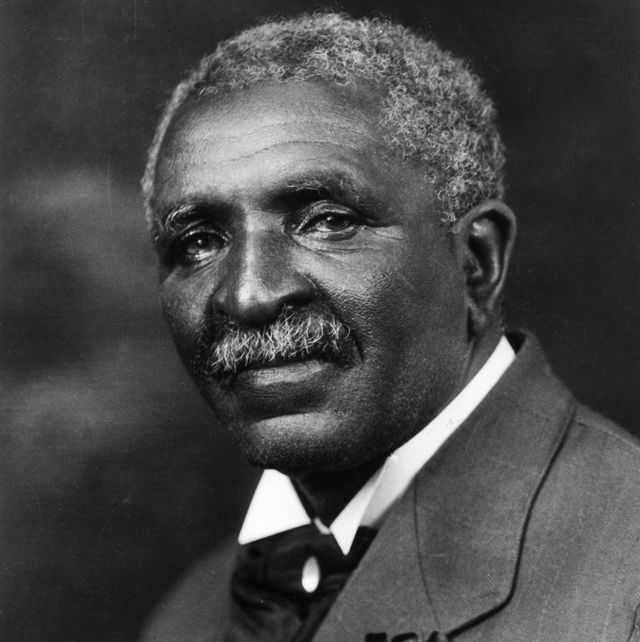

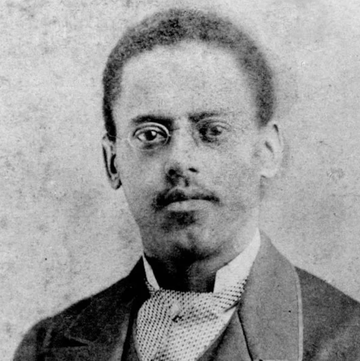

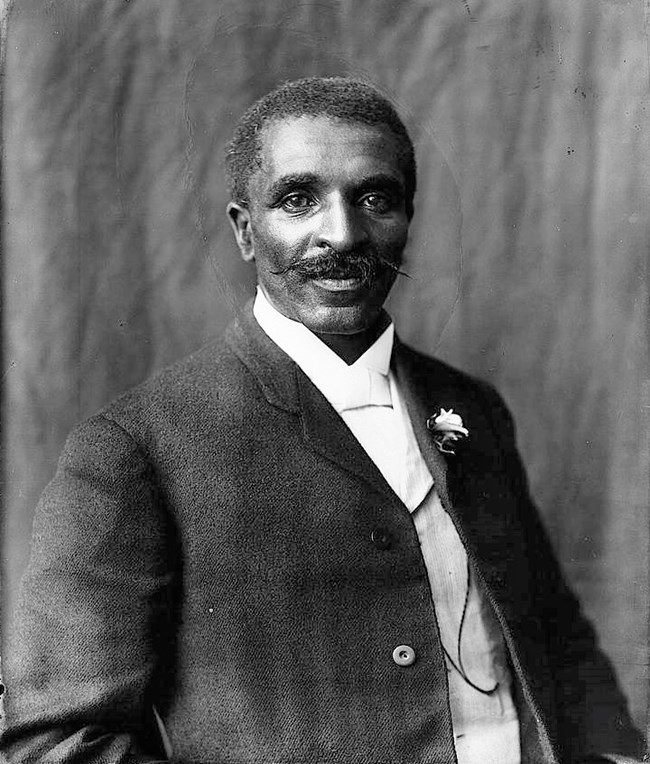

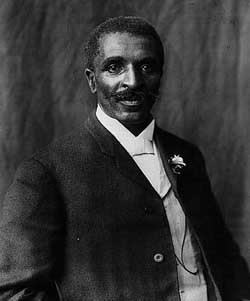

George Washington Carver was an agricultural scientist and inventor who developed hundreds of products using peanuts (though not peanut butter, as is often claimed), sweet potatoes and soybeans. Born into slavery before it was outlawed, Carver left home at a young age to pursue education and would eventually earn a master’s degree in agricultural science from Iowa State University. He would go on to teach and conduct research at Tuskegee University for decades, and soon after his death his childhood home would be named a national monument—the first of its kind to honor a Black American.

Born on a farm near Diamond, Missouri , the exact date of Carver’s birth is unknown, but it’s thought he was born in January or June of 1864.

Nine years prior, Moses Carver, a white farm owner, purchased George Carver’s mother Mary when she was 13 years old. The elder Carver reportedly was against slavery , but needed help with his 240-acre farm.

When Carver was an infant, he, his mother and his sister were kidnapped from the Carver farm by one of the bands of slave raiders that roamed Missouri during the Civil War era. They were resold in Kentucky .

Moses Carver hired a neighbor to retrieve them, but the neighbor only succeeded in finding George, whom he purchased by trading one of Moses’ finest horses. Carver grew up knowing little about his mother or his father, who had died in an accident before he was born.

Moses Carver and his wife Susan raised the young George and his brother James as their own and taught the boys how to read and write.

James gave up his studies and focused on working the fields with Moses. George, however, was a frail and sickly child who could not help with such work; instead, Susan taught him how to cook, mend, embroider, do laundry and garden, as well as how to concoct simple herbal medicines.

At a young age, Carver took a keen interest in plants and experimented with natural pesticides, fungicides and soil conditioners. He became known as the “the plant doctor” to local farmers due to his ability to discern how to improve the health of their gardens, fields and orchards.

At age 11, Carver left the farm to attend an all-Black school in the nearby town of Neosho.

He was taken in by Andrew and Mariah Watkins, a childless Black couple who gave him a roof over his head in exchange for help with household chores. A midwife and nurse, Mariah imparted on Carver her broad knowledge of medicinal herbs and her devout faith.

Disappointed with the education he received at the Neosho school, Carver moved to Kansas about two years later, joining numerous other Blacks who were traveling west.

For the next decade or so, Carver moved from one Midwestern town to another, putting himself through school and surviving off of the domestic skills he learned from his foster mothers.

He graduated from Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas, in 1880 and applied to Highland College in Kansas (today’s Highland Community College ). He was initially accepted at the all-white college but was later rejected when the administration learned he was Black.

In the late 1880s, Carver befriended the Milhollands, a white couple in Winterset, Iowa , who encouraged him to pursue a higher education. Despite his former setback, he enrolled in Simpson College , a Methodist school that admitted all qualified applicants.

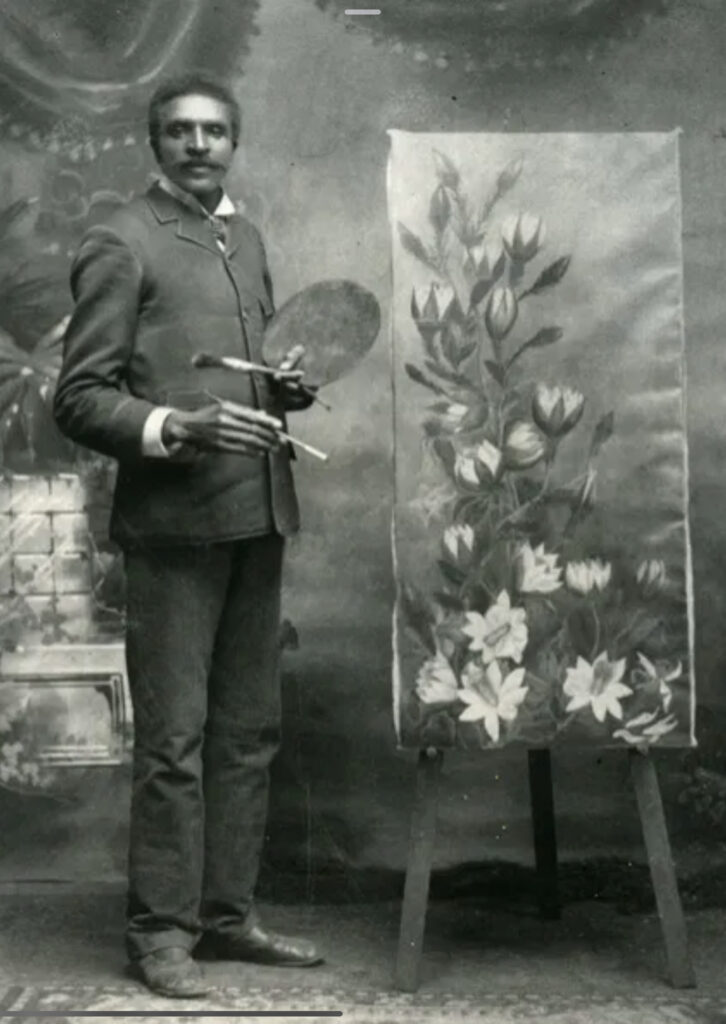

Carver initially studied art and piano in hopes of earning a teaching degree, but one of his professors, Etta Budd, was skeptical of a Black man being able to make a living as an artist. After learning of his interests in plants and flowers, Budd encouraged Carver to apply to the Iowa State Agricultural School (now Iowa State University ) to study botany.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Carver Makes Black History

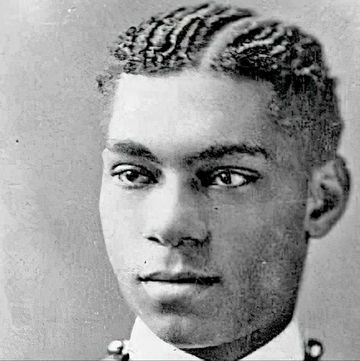

In 1894, Carver became the first African American to earn a Bachelor of Science degree. Impressed by Carver’s research on the fungal infections of soybean plants, his professors asked him to stay on for graduate studies.

Carver worked with famed mycologist (fungal scientist) L.H. Pammel at the Iowa State Experimental Station, honing his skills in identifying and treating plant diseases.

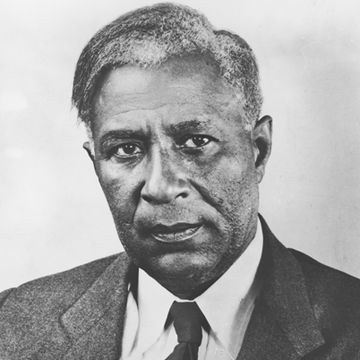

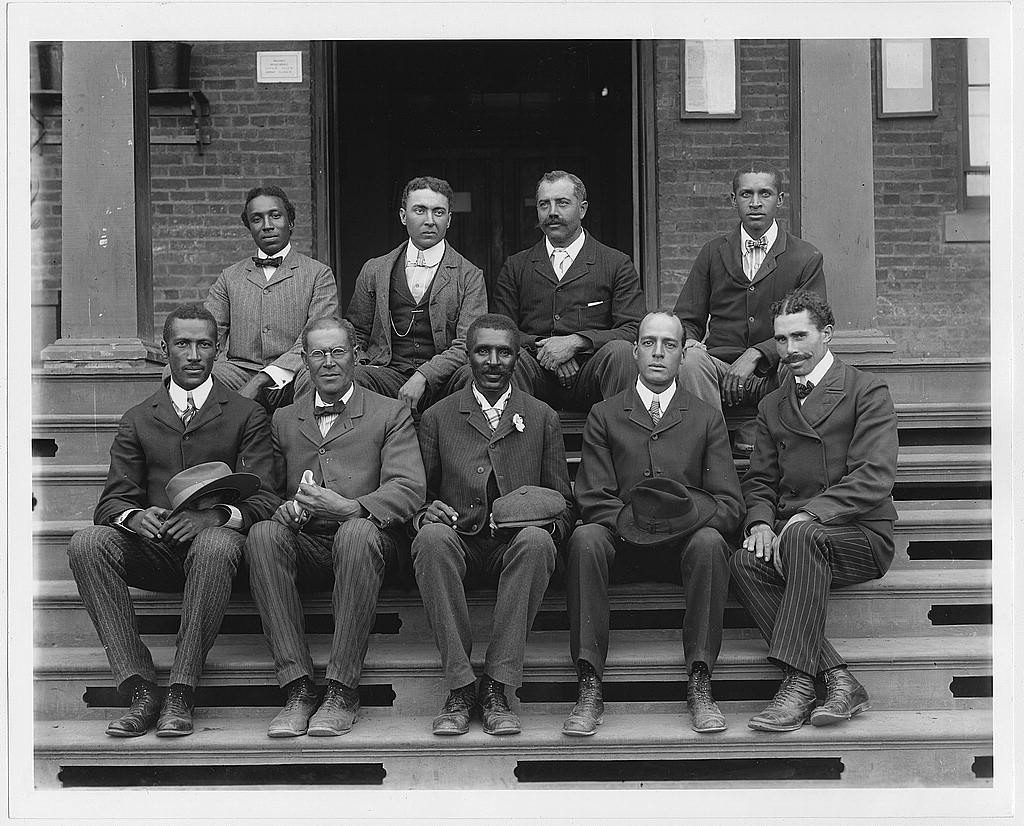

In 1896, Carver earned his Master of Agriculture degree and immediately received several offers, the most attractive of which came from Booker T. Washington (whose last name George would later add to his own) of Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University ) in Alabama .

Washington convinced the university’s trustees to establish an agricultural school, which could only be run by Carver if Tuskegee was to keep its all-Black faculty. Carver accepted the offer and would work at Tuskegee Institute for the rest of his life.

Tuskegee Institute

Carver’s early years at Tuskegee were not without hiccups.

For one, agriculture training was not popular—Southern farmers believed they already knew how to farm and students saw schooling as a means to escape farming. Additionally, many faculty members resented Carver for his high salary and demand to have two dormitory rooms, one for him and one for his plant specimens.

Carver also struggled with the demands of the faculty position he held. He wanted to devote his time to researching agriculture for ways to help out poor Southern farmers, but he was also expected to manage the school’s two farms, teach, ensure the school’s toilets and sanitary facilities worked properly, and sit on multiple committees and councils.

Carver and Washington had a complicated relationship and would butt heads often, in part because Carver wanted little to do with teaching (though he was beloved by his students). Carver would eventually get his way when Washington died in 1915 and was succeeded by Robert Russa Moton, who relieved Carver of his teaching duties except for summer school.

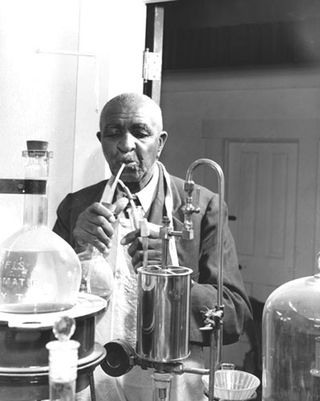

What Did George Washington Carver Invent?

By this time, Carver already had great successes in the laboratory and the community. He taught poor farmers that they could feed hogs acorns instead of commercial feed and enrich croplands with swamp muck instead of fertilizers. But it was his ideas regarding crop rotation that proved to be most valuable.

Through his work on soil chemistry, Carver learned that years of growing cotton had depleted the nutrients from soil, resulting in low yields. But by growing nitrogen-fixing plants like peanuts, soybeans and sweet potatoes, the soil could be restored, allowing yield to increase dramatically when the land was reverted to cotton use a few years later.

To further help farmers, he invented the Jessup wagon, a kind of mobile (horse-drawn) classroom and laboratory used to demonstrate soil chemistry.

Carver: The Peanut Man

Farmers, of course, loved the high yields of cotton they were now getting from Carver’s crop rotation technique. But the method had an unintended consequence: A surplus of peanuts and other non-cotton products.

Carver set to work on finding alternative uses for these products. For example, he invented numerous products from sweet potatoes, including edible products like flour and vinegar and non-food items such as stains, dyes, paints and writing ink.

But Carver’s biggest success came from peanuts.

In all, he developed more than 300 food, industrial and commercial products from peanuts, including milk, Worcestershire sauce, punches, cooking oils, salad oil, paper, cosmetics, soaps and wood stains. He also experimented with peanut-based medicines, such as antiseptics, laxatives and goiter medications.

It should be noted, however, that many of these suggestions or discoveries remained curiosities and did not find widespread applications.

In 1921, Carver appeared before the Ways and Means Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives on behalf of the peanut industry, which was seeking tariff protection. Though his testimony did not begin well, he described the wide range of products that could be made from peanuts, which not only earned him a standing ovation but also convinced the committee to approve a high protected tariff for the common legume.

He then became known as “The Peanut Man.”

Fame and Legacy

In the last two decades of his life, Carver lived as a minor celebrity but his focus was always on helping people.

He traveled the South to promote racial harmony, and he traveled to India to discuss nutrition in developing nations with Mahatma Gandhi .

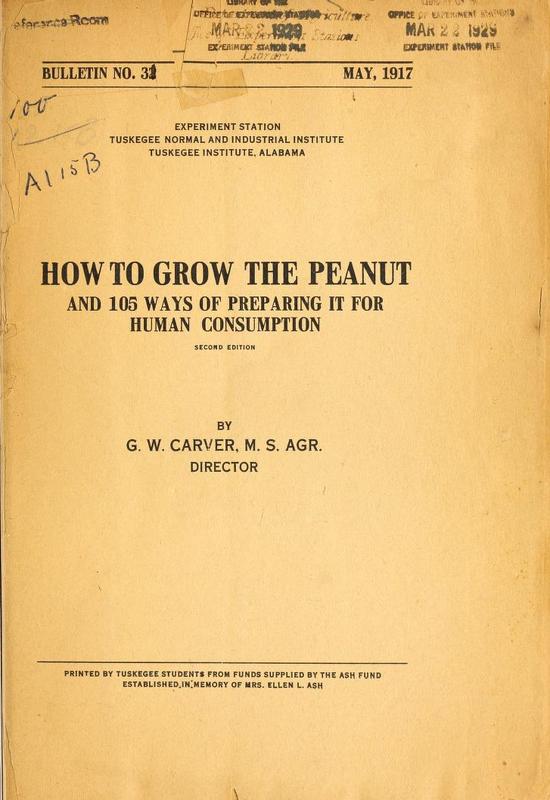

Up until the year of his death, he also released bulletins for the public (44 bulletins between 1898 and 1943). Some of the bulletins reported on research findings but many others were more practical in nature and included cultivation information for farmers, science for teachers and recipes for housewives.

In the mid-1930s, when the polio virus raged in America, Carver became convinced that peanuts were the answer. He offered a treatment of peanut oil massages and reported positive results, though no scientific evidence exists that the treatments worked (the benefits patients experienced were likely due to the massage treatment and attentive care rather than the oil).

Carver died on January 5, 1943, at Tuskegee Institute after falling down the stairs of his home. He was 78 years old. Carver was buried next to Booker T. Washington on the Tuskegee Institute grounds.

Soon after, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed legislation for Carver to receive his own monument, an honor previously only granted to presidents George Washington and Abraham Lincoln .

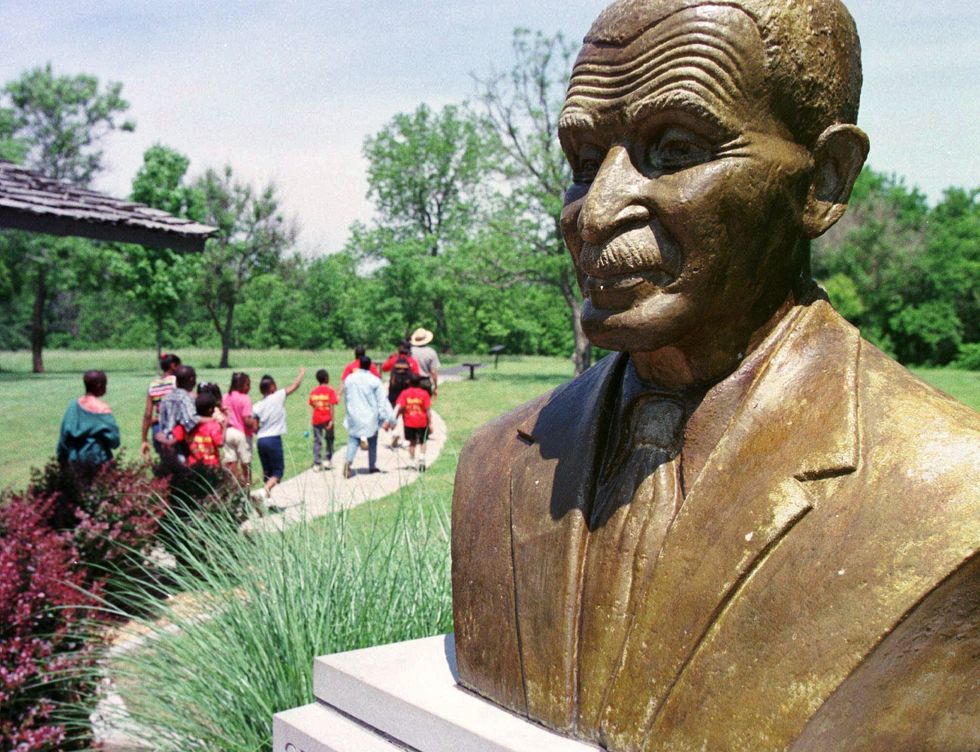

The George Washington Carver National Monument now stands in Diamond, Missouri. Carver was also posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

“Where there is no vision, there is no hope.”

“How far you go in life depends on your being tender with the young, compassionate with the aged, sympathetic with the striving and tolerant of the weak and strong. Because someday in your life you will have been all of these.”

“When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.”

George Washington Carver; American Chemical Society . George W. Carver (1865? – 1943); The State Historical Society of Missouri . George Washington Carver; Science History Museum . George Washington Carver, The Black History Monthiest Of Them All; NPR . George Washington Carver And The Peanut; American Heritage .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

George Washington Carver

Scientist and educator George Washington Carver was born into slavery and became an internationally famous botanist known for his many inventions, including more than 300 uses for the peanut.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

c. 1864-1943

Who Was George Washington Carver?

Quick facts, early life: when was george washington carver born, tuskegee institute teacher, what did george washington carver invent, racial advocacy and personal life, how did george washington carver die, legacy: museum, national monument, and more.

FULL NAME: George W. Carver BORN: c. 1864 DIED: January 5, 1943 BIRTHPLACE: Diamond, Missouri

George Washington Carver was most likely born in 1864 in Diamond, Missouri, during the Civil War years. Like many children of slaves, the exact year and date of his birth are unknown. He was one of many children born to Mary and Giles, an enslaved couple owned by Moses Carver. Giles died in an accident prior to his son’s arrival.

Aladdin 'A Weed Is a Flower: The Life of George Washington Carver' by Aliki

A week after his birth, George was kidnapped from the Carver farm, along with his sister and mother, by raiders from the neighboring state of Arkansas. The three were later sold in Kentucky. Among them, only the infant George was located by an agent of Moses Carver and returned to Missouri.

The conclusion of the Civil War in 1865 brought the end of slavery in Missouri. Moses and and his wife, Susan, subsequently raised George, as well as his older brother James, and gave him their surname.

In his later recollections, George described himself as a sickly child whose body was feeble and in “a constant warfare between life and death to see who would gain the mastery.” As a result, he often assisted Susan with domestic chores instead of doing farm labor and learned how to cook and embroider.

While living there, George developed a fascination with plants and collected specimens from the nearby woods—a hobby that foreshadowed his accomplishments later in life.

Because no local school accepted Black students at the time, Carver’s stand-in mother, Susan, taught him to read and write. The search for knowledge remained a driving force for the rest of George’s life.

When he was around 11 to 12 years old, he left the Carver home to travel to a school for Black children about 10 miles away in the town of Neosho. Although George never lived on the Carver farm again, he kept in touch with Moses and Susan and often returned to visit them.

While at school in Neosho, Carver lived with Mariah and Andrew Watkins, a Black couple who offered him lodging in exchange for help with household tasks such as laundry. Upon meeting Mariah, the boy introduced himself as “Carver’s George,” as he had done his whole life in reference to his prior owner and caretaker. Mariah told him from now on he should refer to himself as “George Carver.”

Years later, Carver adopted the middle initial “W” to distinguish himself from another man named George Carver, but it didn’t stand for any name in particular. A reporter once asked him if the initial stood for “Washington,” and he replied, “Why not?” However, Carver never actually used the name Washington and signed letters as simply George Carver or George W. Carver.

Mariah was a great influence for Carver, introducing him to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and encouraging his studious habits. “You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people,” she told him .

Carver attended a series of schools before receiving his diploma at Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas. Initially accepted to Highland College in Highland, Kansas, Carver was later denied admittance once college administrators learned of his race. Instead of attending classes, he homesteaded a claim, where he conducted biological experiments and compiled a geological collection.

While interested in science, Carver was also interested in the arts. In 1890, he began studying art and music at Simpson College in Iowa, developing his painting and drawing skills through sketches of botanical samples. His obvious aptitude for drawing the natural world prompted a teacher to suggest that Carver enroll in the botany program at the Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University).

Carver moved to Ames and began his botanical studies the following year as the first Black student at Iowa State. He excelled in his studies. Upon completion of his bachelor of science degree in 1894, Carver’s professors Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel persuaded him to stay on for a master’s degree, which he completed in 1896.

His graduate studies included intensive work in plant pathology at the Iowa Experiment Station. In these years, Carver established his reputation as a brilliant botanist and began the work he pursued throughout his career.

After graduating from Iowa State, Carver embarked on a career of teaching and research. Booker T. Washington , the founder of the Tuskegee Institute, hired Carver to run the historically Black school’s agricultural department in 1896.

Washington lured the promising young botanist to the Alabama institute with a hefty salary and the promise of two rooms on campus, while most faculty members lived with a roommate. Carver’s special status stemmed from his accomplishments and reputation, as well as his degree from a prominent institution not normally open to Black students.

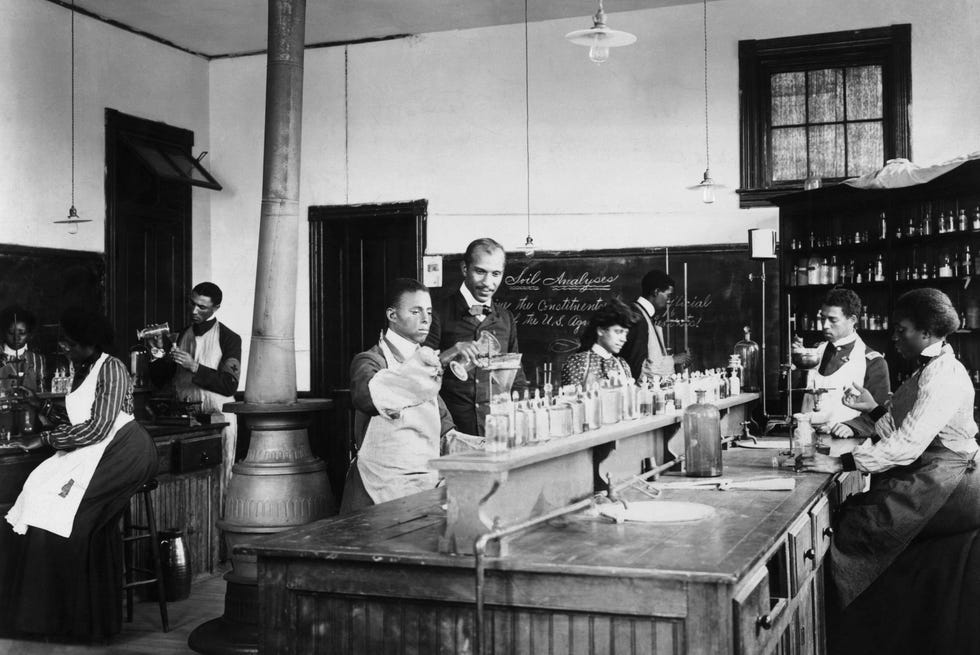

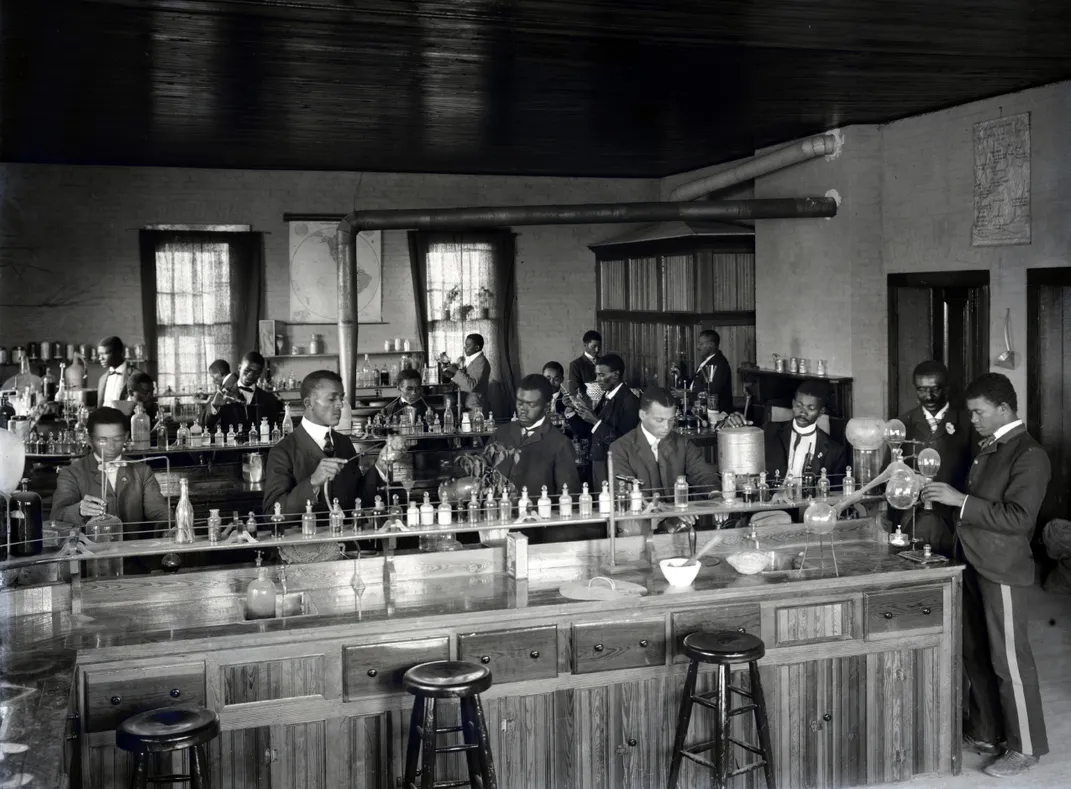

The agricultural department at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) achieved national renown under Carver’s leadership, with a curriculum and a faculty that he helped to shape. Areas of research and training included methods of crop rotation and the development of alternative cash crops for farmers in areas heavily planted with cotton. This work helped under harsh conditions, including the devastation of the boll weevil beginning in 1892.

The development of new crops and diversification of crop uses helped stabilize the livelihoods of American Southerns, including many former enslaved people who had backgrounds similar to Carver’s own. Additionally, the education of African American students at Tuskegee contributed directly to the effort of economic mobilization among Black people.

In addition to formal education in a traditional classroom setting, Carver pioneered a mobile classroom to bring his lessons to farmers. The classroom was known as a “Jesup wagon,” after New York financier and Tuskegee donor Morris Ketchum Jesup.

Carver went on to become a prominent scientific expert and one of the most famous African Americans of his time. Carver achieved international fame in political and professional circles. President Theodore Roosevelt admired his work and sought his advice on agricultural matters affecting the United States. In 1916, Carver became a member of the British Royal Society of Arts—a rare honor for an American. He also advised Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi on matters of agriculture and nutrition.

The educator used his celebrity to promote scientific causes for the remainder of his life. He wrote a syndicated newspaper column and toured the nation, speaking on the importance of agricultural innovation and the achievements at Tuskegee.

Carver’s work at the helm of the Tuskegee Institute’s agricultural department included groundbreaking research on plant biology, much of which focused on the development of new uses for crops including peanuts, sweet potatoes, soybeans, and pecans.

At the time, cotton production was on the decline in the South, and overproduction of a single crop had left many fields exhausted and barren. Carver suggested planting peanuts and soybeans, both of which could restore nitrogen to the soil, along with sweet potatoes. Although these crops grew well in southern climates, there was little demand. Carver’s inventions and research solved this problem and helped struggling sharecroppers in the South find solid ground.

Carver’s inventions include hundreds of products, including more than 300 from peanuts (milk, plastics, paints, dyes, cosmetics, medicinal oils, soap, ink, and wood stains), 118 from sweet potatoes (molasses, postage stamp glue, flour, vinegar, and synthetic rubber), and even a type of gasoline.

Did George Washington Carver Invent Peanut Butter?

Contrary to popular belief, Carver didn’t invent peanut butter . However, he did do a lot of research into new and alternate uses for peanuts.

He even became known as the “Peanut Man” after delivering a speech before the Peanut Growers Association in 1920 attesting to the wide potential of peanuts. The following year, Carver testified before Congress in support of a tariff on imported peanuts, which Congress passed in 1922.

Beyond science, Carver spoke about the possibilities for racial harmony in the United States. From 1923 to 1933, he toured white Southern colleges for the Commission on Interracial Cooperation.

However, Carver largely remained outside of the political sphere and declined to criticize prevailing social norms outright. Thus, the politics of accommodation, which Carver and Booker T. Washington championed, stood in stark contrast to activists who sought more radical change. Nonetheless, Carver’s scholarship and research contributed to improved quality of life for many farming families, making Carver an icon for Black and white Americans alike.

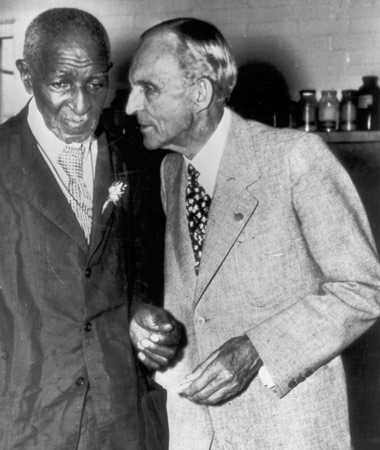

The high-profile scientist developed many friendships throughout his life, including with notable figures like auto magnate Henry Ford . Interested in developing alternatives to gasoline, Ford was drawn to Carver’s work with soybeans and peanuts. They worked on numerous projects together, including a successful replacement for rubber they created in 1942 using the goldenrod plant. Ford even had an elevator installed in Carver’s dormitory so he could access his lab more easily during his later years.

Carver never married and isn’t known to have fathered any children. Often more focused on his work than his relationships, he rejected matchmaking attempts by his friends. Still, around age 40, he began a three-year relationship with Sarah Hunt , a teacher in the Tuskegee Institute night school program. Author Christina Vella suggests in her 2015 biography titled George Washington Carver: A Life that Carver was bisexual.

In 1935, as his health was declining, Carver took on an assistant named Austin W. Curtis. Curtis assisted Carver with his research and writings and even accompanied him while traveling. Curtis also performed some of his own research during this time. “He seems to me more like a son than a person who has just come to work for me,” Carver said of Curtis, who even began calling himself “Baby Carver.”

Carver died after falling down the stairs at his home on January 5, 1943, around age 78.

He was buried next to Booker T. Washington on the Tuskegee Institute grounds. Carver’s epitaph reads: “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.” A funeral service for Carver was held at Tuskegee’s chapel.

Before Carver’s death, the first museum bearing his named opened in 1941. The George Washington Carver Museum, located on the Tuskegee Institute campus in Alabama, displayed much of his life’s work, including scientific specimens and some of his paintings and drawings. Carver, who had lived a frugal life, helped fund the museum as did his friend and collaborator Henry Ford . The scientist also established the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee, with the aim of supporting future agricultural research.

In December 1947, a fire broke out in the George Washington Carver museum, destroying much of the collection. One of the surviving works by Carver is a painting of a yucca and a cactus that was displayed at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Since 1977, the National Park Service has owned and operated the museum.

A project to erect a national monument in Carver’s honor also began before his death. Then-Senator Harry S. Truman from Missouri sponsored a bill in favor of a monument during World War II . Supporters of the bill argued that the wartime expenditure was warranted because the monument would promote patriotic fervor among Black Americans and encourage them to enlist in the military. The bill passed unanimously in both houses.

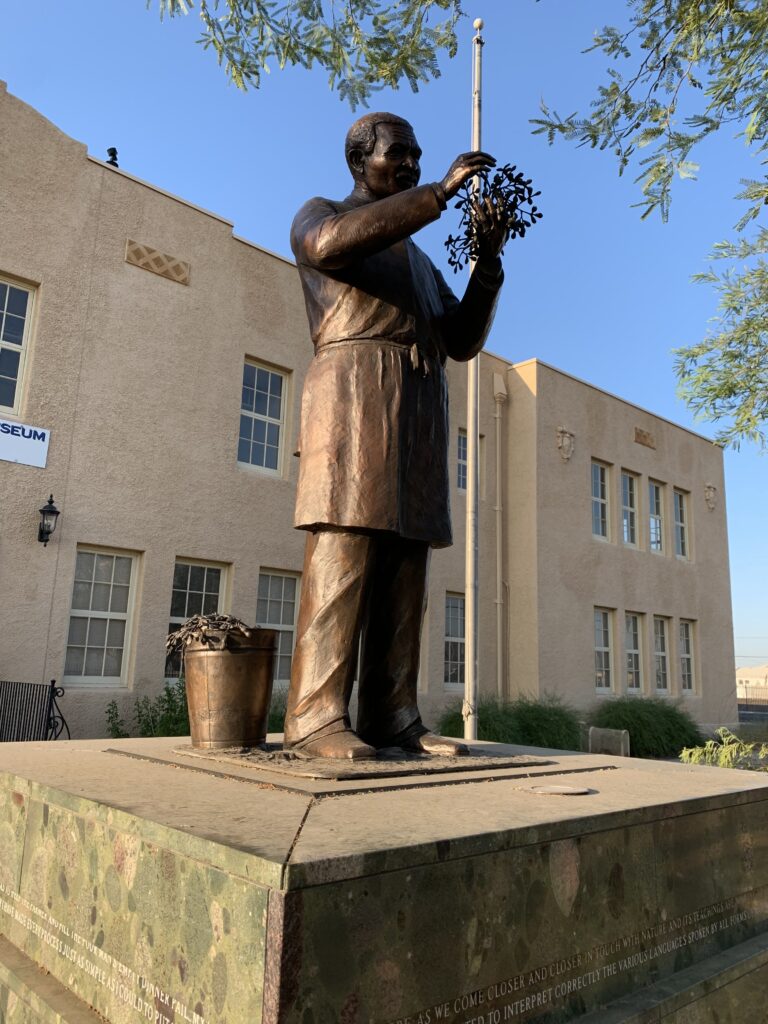

In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated $30,000 for the George Washington Carver National Monument in Diamond, Missouri, the site of the plantation where Carver lived as a child. It is the first national monument dedicated to an African American. The 210-acre complex includes a statue of Carver as well as a nature trail, museum, and cemetery.

Carver appeared on U.S. commemorative postal stamps in 1948 and 1998, as well as a commemorative half dollar coin minted between 1951 and 1954. Numerous schools bear his name, as do two United States military vessels. In 2005, the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis opened a George Washington Carver Garden, which includes a life-size statue of the garden’s famous namesake.

These honors attest to Carver’s enduring legacy as an icon of African American achievement and of American ingenuity more broadly. Carver’s life has come to symbolize the transformative potential of education, even for those born into the most unfortunate and difficult of circumstances.

- It is not the style of clothes one wears, neither the kind of automobile one drives, nor the amount of money one has in the bank, that counts. These mean nothing. It is simply service that measures success.

- When our thoughts—which bring actions—are filled with hate against anyone, Negro or white, we are in a living hell. That is as real as hell will ever be.

- I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting system, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in.

- When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.

- Look about you. Take hold of the things that are here. Let them talk to you. You learn to talk to them.

- Fear of something is at the root of hate for others, and hate within will eventually destroy the hater. Keep your thoughts free from hate, and you need have no fear from those who hate you.

- While hate for our fellow man puts us in a living hell, holding good thoughts for them brings us an opposite state of living, one of happiness, success, peace. We are then in heaven.

- Instead of growing morose and despondent over opportunities either real or imaginary that are shut from us, let us rejoice at the many unexplored fields in which there is unlimited fame and fortune to the successful explorer and upon which there is no color line; simply survival of the fittest.

- Our creator is the same and never changes despite the names given Him by people here and in all parts of the world. Even if we gave Him no name at all, He would still be there, within us, waiting to give us good on this earth.

- Nature study is agriculture, and agriculture is nature study—if properly taught.

- More and more as we come closer and closer in touch with nature and its teachings are we able to see the Divine and are therefore fitted to interpret correctly the various languages spoken by all forms of nature about us.

- As I worked on projects which fulfilled a real human need forces were working through me which amazed me. I would often go to sleep with an apparently insoluble problem. When I woke the answer was there.

- We get closer to God as we get more intimately and understandingly acquainted with the things he has created. I know of nothing more inspiring than that of making discoveries for one’s self.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Black Inventors

Frederick Jones

Lonnie Johnson

11 Famous Black Inventors Who Changed Your Life

Lewis Howard Latimer

Patricia Bath

Garrett Morgan

Madam C.J. Walker

Sarah Boone

Henry Blair

22 Famous Scientists You Should Know

7 Facts on George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver: Biography, Inventions & Quotes

George Washington Carver was a prominent American scientist and inventor in the early 1900s. Carver developed hundreds of products using the peanut, sweet potatoes and soybeans. He also was a champion of crop rotation and agricultural education. Born into slavery, today he is an icon of American ingenuity and the transformative potential of education.

Carver was likely born in January or June of 1864. His exact birth date is unknown because he was born a slave on the farm of Moses Carver in Diamond, Missouri. Very little is known about George’s father, who may have been a field hand named Giles who was killed in a farming accident before George was born. George’s mother was named Mary; he had several sisters, and a brother named James.

When George was only a few weeks old, Confederate raiders invaded the farm, kidnapping George, his mother and sister. They were sold in Kentucky, and only George was found by an agent of Moses Carver and returned to Missouri. Carver and his wife, Susan, raised George and James and taught them to read.

James soon gave up the lessons, preferring to work in the fields with his foster father. George was not a strong child and was not able to work in the fields, so Susan taught the boy to help her in the kitchen garden and to make simple herbal medicines. George became fascinated by plants and was soon experimenting with natural pesticides, fungicides and soil conditioners. Local farmers began to call George “the plant doctor,” as he was able to tell them how to improve the health of their garden plants.

At his wife’s insistence, Moses found a school that would accept George as a student. George walked the 10 miles several times a week to attend the School for African American Children in Neosho, Kan. When he was about 13 years old, he left the farm to move to Ft. Scott, Kan., but he later moved to Minneapolis, Kan., to attend high school. He earned much of his tuition by working in the kitchen of a local hotel. He concocted new recipes, which he entered in local baking contests. He graduated from Minneapolis High School in 1880 and set his sights on college.

College years

George first applied to Highland Presbyterian College in Kansas. The college was impressed by George’s application essay and granted him a full scholarship. When he arrived at the school, however, he was turned away — they hadn’t realized he was black. Over the next few years, George worked at a variety of jobs. He homesteaded a farm in Kansas, worked a ranch in New Mexico, and worked for the railroads, always saving money and looking for a college that would accept him.

In 1888, George enrolled as the first black student at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa. He began studying art and piano, expecting to earn a teaching degree. Carver later said, “The kind of people at Simpson College made me believe I was a human being.” Recognizing the unusual attention to detail in his paintings of plants and flowers his instructor, Etta Budd, encouraged him to apply to Iowa State Agricultural School (now Iowa State University) to study Botany.

At Iowa State, Carver was the first African American student to earn his Bachelor of Science in 1894. His professors were so impressed by his work on the fungal infections common to soybean plants that he was asked to remain as part of the faculty to work on his master’s degree (awarded in 1896). Working as director of the Iowa State Experimental Station, Carver discovered two types of fungi, which were subsequently named for him. Carver also began experiments in crop rotation, using soy plantings to replace nitrogen in depleted soil. Before long, Carver became well known as a leading agricultural scientist.

Tuskegee Institute

In April 1896, Carver received a letter from Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute, one of the first African American colleges in the United States. “I cannot offer you money, position or fame,” read this letter. “The first two you have. The last from the position you now occupy you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer you in their place: work – hard work, the task of bringing people from degradation, poverty and waste to full manhood. Your department exists only on paper and your laboratory will have to be in your head.” Washington’s offer was $125.00 per month (a substantial cut from Carver’s Iowa State salary) and the luxury of two rooms for living quarters (most Tuskegee faculty members had just one). It was an offer that George Carver accepted immediately and the place where he worked for the remainder of his life.

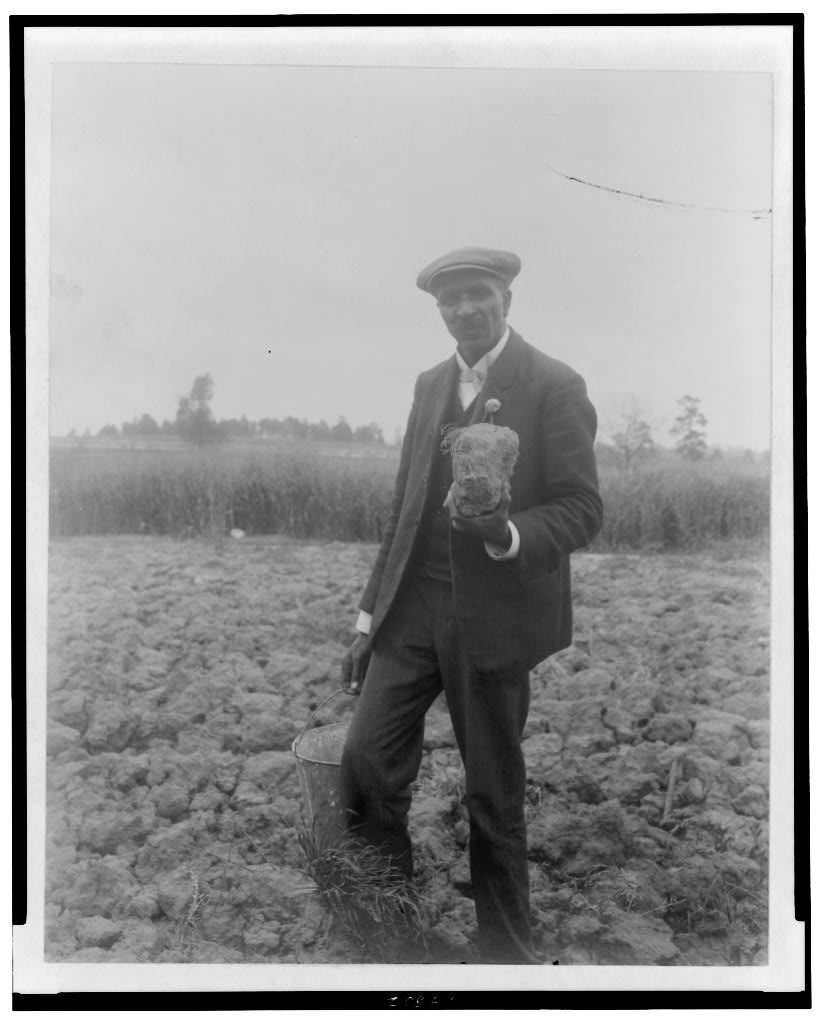

Carver was determined to use his knowledge to help poor farmers of the rural South. He began by introducing the idea of crop rotation. In the Tuskegee experimental fields, Carver settled on peanuts because it was a simple crop to grow and had excellent nitrogen fixating properties to improve soil depleted by growing cotton. He took his lessons to former slaves turned sharecroppers by inventing the Jessup Wagon, a horse-drawn classroom and laboratory for demonstrating soil chemistry. Farmers were ecstatic with the large cotton crops resulting from the cotton/peanut rotation, but were less enthusiastic about the huge surplus of peanuts that built up and began to rot in local storehouses.

Peanut products

Carver heard the complaints and retired to his laboratory for a solid week, during which he developed several new products that could be produced from peanuts. When he introduced these products to the public in a series of simple brochures, the market for peanuts skyrocketed. Today, Carver is credited with saving the agricultural economy of the rural South.

From his work at Tuskegee, Carver developed approximately 300 products made from peanuts; these included: flour, paste, insulation, paper, wall board, wood stains, soap, shaving cream and skin lotion. He experimented with medicines made from peanuts, which included antiseptics, laxatives and a treatment for goiter.

What about peanut butter?

Contrary to popular belief, while Carver developed a version of peanut butter, he did not invent it. The Incas developed a paste made out of ground peanuts as far back as 950 B.C. In the United States, according to the National Peanut Board , Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, of cereal fame, invented a version of peanut butter in 1895.

A St. Louis physician may have developed peanut butter as a protein substitute for people who had poor teeth and couldn't chew meat. Peanut butter was introduced at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.

Aiding the war effort

During World War I, Carver was asked to assist Henry Ford in producing a peanut-based replacement for rubber. Also during the war, when dyes from Europe became difficult to obtain, he helped the American textile industry by developing more than 30 colors of dye from Alabama soils.

After the War, George added a "W" to his name to honor Booker T. Washington. Carver continued to experiment with peanut products and became interested in sweet potatoes, another nitrogen-fixing crop. Products he invented using sweet potatoes include: wood fillers, more than 73 dyes, rope, breakfast cereal, synthetic silk, shoe polish and molasses. He wrote several brochures on the nutritional value of sweet potatoes and the protein found in peanuts, including recipes he invented for use of his favorite plants. He even went to India to confer with Mahatma Gandhi on nutrition in developing nations.

In 1920, Carver delivered a speech to the new Peanut Growers Association of America. This organization was advocating that Congress pass a tariff law to protect the new American industry from imported crops. As a result of this speech, he testified before Congress in 1921 and the tariff was passed in 1922. In 1923, Carver was named as Speaker for the United States Commission on Interracial Cooperation, a post he held until 1933. In 1935, he was named head of the Division of Plant Mycology and Disease Survey for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. By 1938, largely due to Carver’s influence, peanuts had grown to be a $200-million-per-year crop in the United States and were the chief agricultural product grown in the state of Alabama.

Carver's legacy

Carver died on Jan. 5, 1943. At his death, he left his life savings, more than $60,000, to found the George Washington Carver Institute for Agriculture at Tuskegee. In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated funds to erect a monument at Diamond, Missouri, in his honor.

Commemorative postage stamps were issued in 1948 and again in 1998. A George Washington Carver half-dollar coin was minted between 1951 and 1954. There are two U.S. military vessels named in his honor.

There are also numerous scholarships and schools named for him. He was awarded an honorary doctorate from Simpson College. Since his exact birth date is unknown, Congress has designated January 5 as George Washington Carver Recognition Day.

Carver only patented three of his inventions. In his words, “It is not the style of clothes one wears, neither the kind of automobile one drives, nor the amount of money one has in the bank that counts. These mean nothing. It is simply service that measures success.”

Carver quotes

"Ninety-nine percent of the failures come from people who have the habit of making excuses."

"Fear of something is at the root of hate for others, and hate within will eventually destroy the hater."

"Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom."

"When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world."

"Where there is no vision, there is no hope."

"Nothing is more beautiful than the loveliness of the woods before sunrise."

"There is no short cut to achievement. Life requires thorough preparation - veneer isn't worth anything."

"Learn to do common things uncommonly well; we must always keep in mind that anything that helps fill the dinner pail is valuable."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

30,000 years of history reveals that hard times boost human societies' resilience

'We're meeting people where they are': Graphic novels can help boost diversity in STEM, says MIT's Ritu Raman

James Webb telescope detects 1-of-a-kind atmosphere around 'Hell Planet' in distant star system

Most Popular

- 2 Cave of Crystals: The deadly cavern in Mexico dubbed 'the Sistine Chapel of crystals'

- 3 'The most critically harmful fungi to humans': How the rise of C. auris was inevitable

- 4 2,500-year-old Illyrian helmet found in burial mound likely caused 'awe in the enemy'

- 5 32 of the most colorful birds on Earth

- 2 'The most critically harmful fungi to humans': How the rise of C. auris was inevitable

- 3 32 of the most colorful birds on Earth

- 4 Roman-era skeletons buried in embrace, on top of a horse, weren't lovers, DNA analysis shows

- 5 Stone with 1,600-year-old Irish inscription found in English garden

- African American Heroes

George Washington Carver

How this scientist nurtured the land—and people’s minds

To George Washington Carver, peanuts were like paintbrushes: They were tools to express his imagination. Carver was a scientist and an inventor who found hundreds of uses for peanuts. He experimented with the legumes to make lotions, flour, soups, dyes, plastics, and gasoline—though not peanut butter!

Carver was born an enslaved person in the 1860s in Missouri . The exact date of his birth is unclear, but some historians believe it was around 1864, just before slavery was abolished in 1865. As a baby, George, his mother, and his sister were kidnapped from the man who enslaved them, Moses Carver. The kidnappers were slave raiders who planned to sell them. Moses Carver found George before he could be sold, but not his mother and sister. George never saw them again.

After slavery was abolished, George was raised by Moses Carver and his wife. He worked on their farm and in their garden, and became curious about plants, soils, and fertilizers. Neighbors called George “the plant doctor” because he knew how to nurse sick plants back to life. When he was about 13, he left to attend school and worked hard to get his education.

In 1894 he became the first Black person to graduate from Iowa State College, where he studied botany and fungal diseases, and later earned a master’s degree in agriculture. In 1896, Booker T. Washington offered him a teaching position at Tuskegee Institute, a college for African Americans.

There, Carver’s research with peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans flourished. He made agricultural advancements to help improve the lives of poor Black farmers like himself. With the help of his mobile classroom, the Jesup Wagon, he brought his lessons to former enslaved farmworkers and used showmanship to educate and entertain people about agriculture.

On January 5, 1943, Carver died after falling down some stairs. But his contributions to the field of agriculture would not be forgotten. Carver became the first Black scientist to be memorialized in a national monument, which was erected near his birthplace in Diamond Grove, Missouri.

Read this next!

African american pioneers of science, black history month, 1963 march on washington.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- (602)675-4755

[email protected]

(602) 675-4755.

George Washington Carver

“The Primary idea in all my work was to help the farmer and fill the poor man’s empty dinner pail … My idea is to help the ‘man farthest down’; This is why I have made every process as simple as I could to put it within his reach.”

George W. Carver

George Washington Carver, Born a slave around 1864, became a famous artist, teacher, scientist, and humanitarian. From childhood, he developed a remarkable understanding of the natural world. Carver devoted his life to improving agriculture and the economic conditions of African-Americans in the south.

In 1896, Booker T Washington hired Carver to teach agriculture at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Over a 40-year career, Carver taught many generations of Tuskegee students. He emphasized increasing the independence of local farmers. He believed that a practical education would both make African-Americans and white farmers self-sufficient.

“It has always been the one ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of my people possible and to this end I have been preparing myself for these many years, feeling as I do that this line of education is the key”

Struggle and Triumph: The Legacy of George Washington Carver (NPS Movie 28min)

The Early Years

“Day after day I spent in the woods… to collect my floral beauties… all sorts of vegetation seemed to thrive under my touch until I was styled the plant doctor, and plants from all over the county would be brought to me for treatment”

George Washington Carver

Born as a slave on a small farm in Diamond Grove, Missouri; the best information suggest he was born in 1864, near the end of the civil war. To appreciate nature and to assist his learning, George began a lifelong habit of taking long walks to observe nature and collect specimens.

Religion also played an important role in Carver’s life. It broke down social and racial barriers and was the inspiration for his research and teachings. Yet, he did not allow his beliefs to conflict with his scientific knowledge.

“The Great Creator… permit(s) me to speak to Him through… the animals, mineral and vegetable kingdoms…”

The School Days of G.W. Carver

“If you love it enough, anything will talk to you”

In the 1880s, local white schools did not allow African American students. Therefore, even though he had a great desire for knowledge, carver attended school whenever he could.

In 1890, Carver went to Simpson College Iowa to study art. Although African Americans were not allowed to register eventually Carver was admitted to class and he proved to be a talented artist. He paid for his tuition by doing laundry, cooking, and selling his paintings. Carver switched to agriculture studies because he saw this as a better way to contribute to his people. Carver set out to find practical ways to benefit African American farmers.

That led to enrolling at Iowa Agricultural College at Ames, Iowa. His teachers commented that Carver was “a brilliant student and collector.” He worked at the colleges’ experimental station until graduating with a Master of Science degree. He became an expert in field collecting, plant breeding, and plant diseases.

An Artistic Side

“When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world”

When young, Carver loved to draw and paint pictures. Originally an art student in college, he switched to agricultural studies. Yet, Carver continued to paint all of his life and one of his paintings won Honorable Mention at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Carver also would crochet, knit, and do needlework. Always practical, this enabled him to produce useful items for his friends. He learned how to dye his own thread and fibers with local trees, plants, and clay.

Carver collected local clays and extracted their pigments to make paints good enough to attract commercial paint companies. These paints were displayed in his laboratory and at county fairs. He used these paints in his artwork. He also developed house paint colors to encourage local farmers to improve the appearance of their homes. He arranged different paints into pleasing combinations for ceiling, cornices, and walls. Many buildings on the Tuskegee campus and throughout the area used these paint combinations.

Teaching Others

“Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom”

Booker T. Washington hired the best and brightest African American professionals to Tuskegee Institute. In 1896, he hired a young teaching assistant, George Washington Carver. They both believed a practical education was the best path to self-sufficiency for African Americans. Hired to head its Agriculture Department, Carver taught for 47 years, developing the department into a strong research center.

Carver spread the self-sufficiency message at schools, farms, and county fairs. Carver believed students learned best by doing. He expected students to “figure it out for themselves and to do all the common things uncommonly well.” Carver developed close personal relationships with his students, farmers, and powerful philanthropist with his engaging and charming talks and publications.

Booker T. Washington realized that Carver was a “great teacher, a great lecturer, and a great inspirer of young men and old men.”

Useful Bulletins by G.W. Carver

“In painting, the artist attempt to produce pleasing effects through the proper blending of colors. The. Cook must blend her food in such a manner as to produce dishes which are attractive. Harmony in food is just as important as harmony in colors.”

Carver was a talented and innovative cook. He developed recipes for tasty and nutritious dishes that used local and easily-grown crops. He trained farmers to successfully rotate and cultivate new crops and encouraged better nutrition in the South. Carver developed an agricultural extension program for Alabama that used Tuskegee Institute bulletins. In these bulletins, Carver shared his recipes with farmers and housewives.

During his more than four decades at Tuskegee, Carver published 44 practical bulletins for farmers. His first bulletin in 1898 was on feeding acorns to farm animals. His final bulletin in 1943 was about the peanut. Other individual bulletins dealt with sweet potatoes, cotton, cowpeas, alfalfa, wild plums, tomatoes, ornamental plants, corn, poultry, dairying, hogs, preserving meats in hot weather, and nature study in schools.

His most popular bulletin, How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption , was first published in 1916 and was reprinted many times. Carver’s bulletins were not the first American agricultural bulletins devoted to peanuts, but his bulletins were more popular and widespread than others.

Agricultural School On Wheels

Booker T Washington directed his faculty to “take their teaching into the community”

To take lessons to the community, Carver designed a “movable school.” Students built a wagon named for Morris k Jesup, a New York financier who gave Carver the money to equip and operate the movable school. The first one was a horse-drawn agricultural wagon called a Jesup Wagon. Later, a truck still called a Jesup Wagon carried agricultural exhibits to county fairs and community gatherings.

By 1930, the “Booker T Washington Agricultural School on Wheels” carried a nurse, a home demonstration agent, an agricultural agent, and an architect to share the latest techniques with rural people. Eventually, educational films and lectures were presented at local churches and schools. These vehicles were the foundation of Tuskegee’s extension services.

Research For Practical Applications

“Soil enrichment, natural fertilizer use, and crop rotation” were Carvers message to students and farmers

From 1915 to 1923, Carver developed techniques to improve soils depleted by repeated planting of cotton. Also, in the early 20th century, the boll weevil destroyed much of the cotton crops, and planters and farm workers suffered. Together with other agricultural experts, he urged farmers to restore nitrogen to their soils by practicing systematic crop rotation: alternating cotton crops with the planting of sweet potatoes, peanuts, or soybeans. These alternative crops restored nitrogen to the soil and were also good for human consumption. Following the crop rotation practice resulted in improved cotton yield and gave farmers alternative cash crops. He also began research into crop products (chemurgy), and taught generations of black students farming techniques for self-sufficiency. In these years, he became one of the most well-known African Americans of his time.

Always looking for practical solutions from his wide-ranging research, Carver experimented with seeds, soils, soil enrichment, and feed grains. All of his efforts were geared to increasing the self-sufficiency of African American farmers. Ahead of his time, Carver used plant hybridization and recycling the use of locally available technology.

Carver’s research also looked to provide a replacement for commercial products, which were generally beyond the budget of the small one-horse farmer. George W. Carver reputedly discovered three hundred uses for peanuts and hundreds more for soybean, pecans, and sweet potatoes. These alternative products included adhesives, axel grease, bleach, buttermilk, chili sauce, fuel briquettes, ink, instant coffee, linoleum, mayonnaise, meat tenderizer, metal polish, paper, plastic, pavement, shaving cream, shoe polish, synthetic rubber, talcum powder, and wood stain.

Later Years

“Professor Carvers Advice” – George W Carver’s syndicated newspaper column

During the last two decades of his life, Carver seemed to enjoy his celebrity status. He was often on the road promoting the Tuskegee Institute, peanut, and racial harmony. Although he only published six agricultural bulletins in 1922, he published articles in peanut industry journals and wrote a syndicated newspaper column., “Professor Carver’s Advice.” Business leaders came to seek his help, and he often responded with free advice.

From 1933 to 1935, Carver worked to develop peanut oil massages to treat polio. Ultimately researchers found the massages, not the peanut oil, provided the benefits of maintaining some mobility in paralyzed limbs.

Carver had been frugal in his life, and in his 70s, he established a legacy by creating a museum on his work and the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee to continue agricultural research. He donated $60,000 in his savings to create the foundation.

G.W. Carver Last Days

Inscribed on Mr. Carver’s tombstone are the words, “He could have added fortune to his fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world”

Upon returning home one day, Carver took a bad fall down a flight of stairs; he was found unconscious by a maid who took him to the hospital. Carver died January 5, 1943, at the age of 78 from complications (anemia) resulting from his fall. He was buried next to Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute.

National Recognition and Naming

His work, which began for the sake of the poorest farmers, paved the way for a better life for the entire South and became an inspiration to all.

George Washington Carver was born a slave. Since his owner was Moses Carver and given the first name of George, Carver referred to himself as Carver’s George. This was more a property description than a name. When George left to attend school, he slept in a barn owned by the Watkins family. Of hearing how George referred to himself, Mrs. Watkins told him that was no proper name and declared that henceforth he would be George Carver.

Like the man, Carver High school did not start with that name. The Phoenix Union High School district opted to officially embrace segregation. In 1925, to accommodate African American high school students, a bond issue was passed to erect a new high school building. The new school was named the Phoenix Union Colored High school until 1940 when the school became the Phoenix Colored High School. On January 5, 1943, George Washington Carver Died and a few months later the school took on the name of this distinguished educator, scientist, and innovator. In 1953, educational segregation was ruled unconstitutional in Arizona and the school closed the following year.

Why are so many schools, parks, and other landmarks named in honor of Carver? Carver came to stand as a symbol of the intellectual achievements of African Americans. He brought about a significant advance in agricultural training in an era when agriculture was the largest single occupation of Americans. It is so often said that Carver saved Southern agriculture and helped feed the country. His great desire was simply to serve humanity; and his work, which began for the sake of the poorest black sharecroppers, pave the way for a better life for the entire South and became an inspiration to all.

GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER NATIONAL MONUMENT

George Washington Carver National Monument orientation video. (NPS Movie 5min)

Our Monument to George Washington Carver

“How far you go in life depends on you being tender with the young, compassionate with the aged, sympathetic with the striving and tolerant of the weak and strong. Because someday in your life you will have been all of these.”

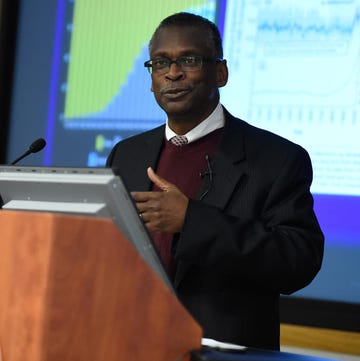

The George Washington Carver statue greeting visitors to the Carver Museum is an exhibit all to itself. The sculpture, Mr. Ed Dwight, is an internationally acclaimed sculptor whose works grace various venues around the United States. Among his works are major African American historic figures.

The Carver Statue was unveiled on February 15, 2004, in a ceremony where Governor Janet Napolitano, among many others, addressed the crowd. The artist, Ed Dwight, spoke movingly before the unveiling. There were musical presentations and acknowledgments of many distinguished guests. Visitors who have viewed and photographed the statue have praised its artistry.

The Carver Statue is an artistic achievement and a worthy monument to its namesake. This exquisite work faithfully captures Carver’s delicate features and somehow reflects the genius and hope that defined the man.

Explore Your Next Virtual Exhibit

Help Us Preserve Our History!

Donate $1 donate $5 donate $10 donate $25 donate $50, 415 e. grant street phoenix, az 85004, mailing address: po box 20491 phoenix, az 85036-0491, office hours, monday-thursday 9:00 a.m.-2:00 p.m. friday 9:00 a.m.-noon, group tours by appointment only. please call or email us to schedule in advance before visiting. walk-in museum visits not available at this time., get involved, become a volunteer, join our board of directors.

The Carver Museum © 2023. All Rights Reserved. Website Sponsored by Compass CBS . Privacy Policy / Terms of Use

Students & Educators —Menu

- Educational Resources

- Educators & Faculty

- Standards & Guidelines

- Periodic Table

- Adventures in Chemistry

- Landmarks Directory

- Frontiers of Knowledge

- Medical Miracles

- Industrial Advances

- Consumer Products

- Cradles of Chemistry

- Nomination Process

- Science Outreach

- Publications

- ACS Student Communities

- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Students & Educators

- Explore Chemistry

- Chemical Landmarks

- George Washington Carver: Chemist, Teacher, Symbol

George Washington Carver

National historic chemical landmark.

Designated January 27, 2005, at Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Alabama.

Commemorative Booklet (PDF)

There is the popular image of George Washington Carver known to every schoolchild in the United States: he was born a slave, worked hard to gain an education and become a scientist, taught at Tuskegee Institute, and became the Peanut Man who discovered myriad uses for the lowly legume. Of course, the story is not that simple. Yet despite criticisms of Carver, there is no denying his role in developing new uses for Southern agricultural crops and teaching poor Southern farmers methods of soil improvement.

George Washington Carver's Early Life

The tuskegee institute, george washington carver and booker t. washington, chemurgy: the agricultural chemist, teacher and mentor, carver as symbol, research notes and further reading, landmark designation and acknowledgments, cite this page.

George Washington Carver guarded his image carefully. While he did not write extensively about his youth, he did leave behind snippets describing his hard early years. These writings tell of a poor orphan who sought knowledge and hungered for scientific discovery but who was sickly and weak. Carver's early years were indeed difficult, but he seems to have exaggerated his frailty. For example, in an autobiographical sketch he wrote in 1897, just as he was beginning his teaching career at the Tuskegee Institute, Carver claimed that when he was a child his "body was very feble [sic] and it was a constant warfare between life and death to see who would gain the mastery." Two paragraphs later comes this sentence: "Day after day I spent in the woods alone in order to collect my floral beautis [sic] and put them in my little garden…" 3

In a 1922 sketch Carver wrote "I was born in Diamond Grove, Missouri, about the close of the great Civil War, in a little one-roomed log shanty, on the home of Mr. Moses Carver, a German by birth and the owner of my mother, my father being the property of Mr. Grant, who owned the adjoining plantation." 4 Carver was never clear about when he was born, sometimes writing "about 1865," or "near the end of the war," or "just as freedom was declared." Since Missouri never seceded from the Union, and thus was not in rebellion when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863, slavery continued in the state until the adoption of a new constitution on July 4, 1865. So Carver was most certainly born a slave, probably in the spring of 1865. 5

Carver's mother Mary was purchased as a 13-year-old girl in 1855 when Moses Carver decided that the need for help on his 240 acre farm trumped his antislavery views. The youngster knew neither of his parents since his father was killed in an accident before his birth and his mother disappeared under somewhat mysterious circumstances. When Carver was an infant his mother and he were kidnapped by one of the many bands of bushwhackers roaming Missouri during the turbulent Civil War era. A neighbor of Moses Carver was hired to find them, but succeeded only in recovering George, at the cost of one of Moses' finest horses. This meant that the young George would be raised by Moses and Susan Carver on their farm in Newton County, Missouri. Carver spent much of his boyhood assisting Susan with domestic chores, since his fragility apparently meant he could not help Moses with the farm chores. As a boy, Carver learned how to cook, mend, do laundry, and embroider. He also developed an interest in plants and helped Susan with the garden.

The youngster had a keen desire to learn, first by exploring the flora and fauna on Moses Carver's farm and by devouring Webster's Elementary Spelling Book, which "I almost knew… by heart." 6 At the age of 11, Carver left the farm and traveled 8 miles to the county seat of Neosho to attend a school for Black children. For the first time, Carver was in a predominantly African-American environment. Previously, he had lived on the Carvers' farm in relative isolation; he had grown used to solitude and had developed a love of nature. Moses and Susan Carver had served as surrogate parents. But while he continued to return to the farm on weekends, he never lived permanently with the Carvers again.

In Neosho Carver acquired a set of Black "parents," Mariah and Andrew Watkins. He lived in the Watkins' modest three-room house in exchange for helping with household tasks such as laundry. Mariah Watkins appears to have had great influence on her 11-year-old charge. She was a midwife and nurse who had wide knowledge of medicinal herbs, and she was deeply religious. Her influence and the rather eclectic introduction he had had to religion at a little church a mile from the Carver farm imparted in young George a deeply felt but unorthodox and nondenominational faith and a belief in divine revelation. He later testified to the number of revelations he had received, recalling the first as a child when his wish for a pocketknife was answered in a dream in which he had a vision of a knife sticking out a half-eaten watermelon. The next morning, the young Carver found his pocketknife. 7

Carver was eager to learn, but his first attempt at formal school proved disappointing since the schoolmaster at the Neosho knew little more than he did. Not satisfied with basic literacy, Carver decided to move west in the late 1870s, joining Black Americans disillusioned by the failure of Reconstruction in a vast migration to Kansas. For the next decade or so, Carver shuttled among numerous Midwestern communities, attending school fitfully, trying his luck at homesteading for a time, and surviving by using the domestic skills he had learned from Susan Carver and Mariah Watkins.

Sometime in the late 1880s Carver's wanderings brought him to Winterset, Iowa, where he met the Milhollands, a white couple who profoundly influenced his life and who he later credited with encouraging him to pursue higher education. The Milhollands urged Carver to enroll in nearby Simpson College. Carver was hesitant; his one previous attempt at higher education resulted in racial humiliation. He had applied to Highland College in Kansas and had been accepted, sight unseen. When he showed up to register at the all-white college, an official said his acceptance had been a mistake as the school had never admitted a Black person and had no intention to do so. Carver was reluctant to be rejected again.

But the Milhollands persisted and Carver eventually entered Simpson College, a small Methodist school in Indianola, Iowa, that admitted all qualified applicants, regardless of race or ethnicity. One Black person had attended the school before Carver, and there were three people of Asian descent still on campus. The school's Methodist affiliation fostered a deepening of Carver's faith and piety, and the school's open policy had a profound affect on his developing self-identity: "They made me believe I was a real human being," he later wrote. 8 While at Simpson, Carver studied grammar, arithmetic, etymology, voice, and piano. But his main interest was in art, especially painting, in which he had dabbled as a young man. His teacher Etta Budd was at first dubious of Carver's talents, and although she changed her perception of him as an artist, she was skeptical about the chances of a Black man earning a living as an artist. When she learned of his interest in plants, Budd encouraged Carver to study botany and pushed him to enroll at Iowa State, the agricultural college in Ames, where her father taught horticulture.

Budd's suggestion evidently posed a dilemma for Carver. He loved painting, but he shared her doubts about his ability to succeed as an artist, and he wondered whether as a painter he could make a contribution to the welfare of African Americans. Now in his mid-twenties, he had come to believe that he had divinely granted talents that should be used to improve the lot of Black Americans. This, he decided, he could do as a trained agriculturalist.

Besides, while he was giving up a career in art it was not as if he had decided to pursue something in which he had no interest. He had long studied plants and he already had developed skills in raising, cross-fertilizing, and grafting plants. He quickly made an impression on the faculty of Iowa State College, and his professors encouraged him to stay on as a graduate student after his senior year. Working with L.H. Pammel, a noted mycologist, Carver honed his talent at identifying and treating plant diseases.

Carver obtained his Master of Agriculture degree in 1896 and immediately received a number of offers. He was asked to join the faculty of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, a school for Black people in Mississippi. The faculty at Iowa State wanted him to stay and teach. But it was an offer from Booker T. Washington that proved most attractive. Washington had persuaded the trustees of Tuskegee Institute to establish an agricultural school. Since Washington wanted the faculty to remain all Black, and since Carver was the only African-American in the country with graduate training in "scientific agriculture," he was the logical choice. Carver was at first hesitant to go to Tuskegee, but Washington was persuasive and on April 12, 1896, Carver accepted, writing that "it has always been the one great ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of 'my people' possible and to this end I have been preparing myself these many years; feeling as I do that this line of education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom to our people." 9

Back to top

Tuskegee's origins were inauspicious. The school was founded on July 4, 1881, in a one-room shanty near Butler Chapel AME Zion Church with Booker T. Washington as the first teacher and a student body of 30. 10 The actual credit for the school's origins goes to George Campbell, 11 a former slave owner, and Lewis Adams, a former slave who could read and write despite a lack of formal education and who appears to have been a tinsmith, shoemaker, and harness-maker. Adams was approached by W.F. Foster, who was running for re-election to the Alabama Senate and wanted the support of African-Americans in Macon County. Foster asked Adams what he wanted in exchange for delivering votes from Black people. Adams requested Foster's support for an educational institution, and so the Alabama legislature passed a bill to establish a Negro Normal School in Tuskegee.

The initial legislation authorized $2,000 for teachers' salaries but nothing for land, buildings, or equipment. But while the school may have been poor, it had a vision from the beginning. That vision grew out of Washington's experience at Hampton Institute, a Virginia school established during Reconstruction, and it found expression in three objectives. First, Tuskegee was to concentrate on training students to be teachers and educators. Second, many Tuskegee students were taught craft and occupational skills geared to helping them find jobs in the trades and agriculture. And finally, Washington wanted Tuskegee to be "a civilizing agent:" as such education took place not only in the classroom but also in the dining hall and dormitories. Washington insisted on proper behavior and absolute cleanliness on the "Tuskegee plantation." He kept careful watch over Tuskegee's buildings and grounds as well as the dormitory rooms and table manners of faculty and staff.

Under Washington's adroit leadership the school quickly grew, moving the year after its founding to 100 acres of nearby abandoned farmland, which became the nucleus of the present school. Washington won widespread support for the school in both the North and the South. He traveled widely and spoke frequently, and convinced many wealthy and prominent people to donate money. Among the school’s early benefactors were Andrew Carnegie, Collis Huntington, and John D. Rockefeller. Washington was a skilled fund raiser, served as adviser to presidents, and helped found schools throughout the South. But he was not without his critics. W.E.B. Du Bois, for example, took exception to Tuskegee's emphasis on vocational training, arguing that it tended to keep Blacks people in a subordinate role. Du Bois favored stressing traditional higher education.

Washington died in 1915 and the debate over educational philosophy diminished as Washington's successor, Robert Russa Moton moved Tuskegee into a more traditional, degree-granting program with the establishment of a College Department in 1927. In 1985 Tuskegee became a university and now has doctoral programs. Today, the school has 3,000 students on a campus that includes 5,000 acres and more than 70 buildings.

As the most prominent African-American of his day, Booker T. Washington had tremendous influence on southern race relations from 1895 to his death in 1915. Much of this stemmed from Washington's speech at the Atlanta Exposition of 1895 in which he advocated the "doctrine of accommodation." 12 The so-called Atlanta Compromise urged Black people to accommodate to the reality of white control and acquiesce in disfranchisement and social segregation. In return, white people should encourage and reward Black progress in economic and educational development. Washington told Black people "to cast down their buckets" where they were and climb the ladder of economic success through the old virtues of hard work and thrift. "The opportunity to earn a dollar," he said, "in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house." Washington asserted that Black people should for the foreseeable future eschew demanding political and social rights, saying those rights would follow economic independence. "No race," he stressed, "that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized."

Washington's racial philosophy mirrored the times. The abolitionist spirit of the Civil War and Reconstruction had resulted in Black people winning many civil and political rights. But even before the end of Reconstruction in 1877 those rights were being eroded. Over the next 20 years the North and the federal government effectively abandoned protection of the former slaves, leaving it to white southerners to work out racial relationships. The gradual erosion of political and social rights accelerated in the 1890s during the political turmoil of the Populist era, when attempts to forge an alliance of the dispossessed of both races foundered on the race-baiting appeals of the politically entrenched. For the next half-century all white people, regardless of socio-economic status, tacitly agreed to submerge class differences in the interest of racial separation.

George Washington Carver readily accepted Washington's racial philosophy and his program of interracial cooperation in the economic sphere. Carver's own success demonstrated to him the importance of economic development in raising the economic status of former slaves. And since the vast preponderance of southern Black people remained tied to the land, Carver fervently believed that his training as an agricultural scientist had prepared him for Tuskegee.

But in reality Carver was not prepared for Tuskegee. He had spent most of his life living and working around white people; now he found himself in a community of Black people where his dark skin made him suspect among the generally lighter-skinned faculty and students. He came from the North to teach "scientific agriculture" to southern farmers who believed they already knew how to farm. Many on the faculty resented Carver's exorbitant salary of $1,000 a year plus virtually all expenses for a man who did not have a family. At the time, the average salary for a Tuskegee faculty member was less than $400 a year. Some resented Carver's demand, which was met, to have two dormitory rooms, one for him and one for his plant specimens when other unmarried faculty lived two to a room.

Carver expected that as director of the newly created Agricultural Experimental Station he would devote most of his time to research. Washington was not hostile to research, but he also expected Carver to manage the school's two farms, teach a full regimen of classes, serve on numerous committees (a chore Carver particularly disliked), and sit on the institute's executive council as well as insure that the schools water closets and other sanitary facilities functioned properly. Above all, Washington and Carver were very different men who were almost fated to clash. Washington was a pragmatist always in a hurry to get things done; Carver was a dreamer who only wanted freedom to tinker in his laboratory, experiment with plants, or if the spirit moved him, pick up a brush and paint. In addition, the well-organized Washington resented the disorganized, administratively sloppy, and shabbily dressed Carver.

To make matters worse, Carver had a running feud with George Bridgeforth, a subordinate who was not reticent in campaigning for Carver's position. Bridgeforth openly criticized Carver to Washington and the latter appeared to often take Bridgeforth's side and repeated his criticisms to Carver, who found the dispute distasteful. But Carver often refused to accept Washington's suggestions, which the principal admitted were just "a polite way of giving orders." 13 The dispute ran on for years, and Washington careened from trying to satisfy Carver to issuing him ultimatums.

Part of the problem stemmed from Carver's insistence on having a laboratory for his exclusive use and to be relieved of his teaching duties. Washington's response to this was clear: "We are all here," he said, "to help the students, to instruct them, and there is no justification for the presence of any teacher here except as that teacher is to serve the students." 14 Washington tried to placate Carver because he genuinely recognized Carver's "great ability in original research," but he refused to allow the scientist to completely stop teaching. 15 Washington's successor, Robert Russa Moton, who took over in 1915, was more accommodating, relieving Carver of all teaching except summer school.

George Washington Carver believed he had a God-given mission to use his training as an agricultural chemist to help improve the lot of poor Black and white Southern farmers. He did this by teaching farmers about fertilization and crop rotation and by developing hundreds of new products from common agricultural products. In addition to his work as a scientist, Carver served the cause of science, in the words of his chief biographer, "magnificently as an interpreter and humanizer, providing an essential link between researchers and laymen and enabling many to reap the benefits of others' work by helping them to apply it to their own circumstances." 16

Late in Carver's life he became a devotee of the chemurgy ("chem" from chemistry; urgy, Greek for work) movement. The term was used to describe scientists, agriculturalists, and industrialists who were determined to put chemistry to work to find nonfood uses for agricultural surpluses. One of the prime backers of chemurgy was Henry Ford, who Carver variously addressed in letters as "My beloved friend" and "The greatest of all my inspiring friends." 17 Ford visited Tuskegee in 1938, and Carver was Ford's guest in 1940 at the automaker's Georgia estate.

But Carver did not need the imprimatur of Henry Ford or the formal title of a movement to explain his role as a scientist, for in truth Carver dedicated his entire scientific work to the goals later advocated by the chemurgy movement. Carver's laboratory at Tuskegee, almost from the beginning of his tenure at the Institute, developed hundreds of new uses for agricultural products. The need for this resulted in part from Carver's initial success in increasing agricultural productivity on the cotton-depleted, tired, old soils of the South. On the 10-acre experimental station at Tuskegee Carver was able, by using good cultivation practices and rotating soil-enriching plants like cowpeas and beans, to dramatically increase soil productivity.