- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 21 Nov 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Cold Call: Building a More Equitable Culture at Delta Air Lines

In December 2020 Delta Air Lines CEO Ed Bastian and his leadership team were reviewing the decision to join the OneTen coalition, where he and 36 other CEOs committed to recruiting, hiring, training, and advancing one million Black Americans over the next ten years into family-sustaining jobs. But, how do you ensure everyone has equal access to opportunity within an organization? Professor Linda Hill discusses Delta’s decision and its progress in embedding a culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion in her case, “OneTen at Delta Air Lines: Catalyzing Family-Sustaining Careers for Black Talent.”

- 16 Oct 2023

Advancing Black Talent: From the Flight Ramp to 'Family-Sustaining' Careers at Delta

By emphasizing skills and expanding professional development opportunities, the airline is making strides toward recruiting and advancing Black employees. Case studies by Linda Hill offer an inside look at how Delta CEO Ed Bastian is creating a more equitable company and a stronger talent pipeline.

- 26 Jul 2023

- Research & Ideas

STEM Needs More Women. Recruiters Often Keep Them Out

Tech companies and programs turn to recruiters to find top-notch candidates, but gender bias can creep in long before women even apply, according to research by Jacqueline Ng Lane and colleagues. She highlights several tactics to make the process more equitable.

- 28 Feb 2023

Can Apprenticeships Work in the US? Employers Seeking New Talent Pipelines Take Note

What if the conventional college-and-internship route doesn't give future employees the skills they need to build tomorrow's companies? Research by Joseph Fuller and colleagues illustrates the advantages that apprenticeships can provide to employees and young talent.

- 09 Aug 2021

OneTen: Creating a New Pathway for Black Talent

A new organization aims to help 1 million Black Americans launch careers in the next decade, expanding the talent pool. Rawi E. Abdelal, Katherine Connolly Baden, and Boris Groysberg explain how. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 19 May 2021

Why America Needs a Better Bridge Between School and Career

As the COVID-19 pandemic wanes, America faces a critical opportunity to close gaps that leave many workers behind, say Joseph Fuller and Rachel Lipson. What will it take? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Mar 2021

Managing Future Growth at an Innovative Workforce Education Startup

Guild Education is an education marketplace that connects employers and universities to provide employees with “education as a benefit.” Now CEO and co-founder Rachel Carlson must decide how to manage the company’s future growth. Professor Bill Sahlman discusses this unique startup and Carlson’s plans for its growth in his case, “Guild Education: Unlocking Opportunity for America's Workforce.” Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Aug 2020

Who Will Give You the Best Professional Guidance?

Even the most powerful leaders need support and guidance occasionally. Julia Austin offers advice own how and where to find the right type of mentor. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 27 Apr 2020

How Remote Work Changes What We Think About Onboarding

COVID-19 has turned many companies into federations of remote workplaces, but without guidance on how their onboarding of new employees must change, says Boris Groysberg. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 07 Jul 2019

Walmart's Workforce of the Future

A case study by William Kerr explores Walmart's plans for future workforce makeup and training, and its search for opportunities from digital infrastructure and automation. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 30 Jun 2019

- Working Paper Summaries

The Comprehensive Effects of Sales Force Management: A Dynamic Structural Analysis of Selection, Compensation, and Training

When sales forces are well managed, firms can induce greater performance from them. For this study, the authors collaborated with a major multinational firm to develop and estimate a dynamic structural model of sales employee responses to various management instruments like compensation, training, and recruiting/termination policies.

- 03 Apr 2019

Learning or Playing? The Effect of Gamified Training on Performance

Games-based training is widely used to engage and motivate employees to learn, but research about its effectiveness has been scant. This study at a large professional services firm adopting a gamified training platform showed the training helps performance when employees are already highly engaged, and harms performance when they’re not.

- 02 Apr 2019

Managerial Quality and Productivity Dynamics

Which managerial skills, traits, and practices matter most for productivity? This study of a large garment firm in India analyzes the integration of features of managerial quality into a production process characterized by learning by doing.

- 23 Jul 2018

The Creative Consulting Company

Management theories cannot be tested in laboratories; they must be applied, tested, and extended in real organizations. For this reason the most creative consulting companies balance conflicting demands between short‐term business development and long‐term knowledge creation.

- 25 Jul 2016

Who is to Blame for 'The Great Training Robbery'?

Companies spend billions annually training their executives, yet rarely realize all the benefit they could, argue Michael Beer and colleagues. He discusses a new research paper, The Great Training Robbery. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 19 Apr 2016

The Great Training Robbery

There is a widely held assumption in corporate life that well trained, even inspired individuals can change the system. This article explains why training fails and discusses why the “great training robbery” persists. The authors offer a framework for integrating leadership and organization change and development, and discuss implications for the corporate HR function.

- 08 Sep 2015

Knowledge Transfer: You Can't Learn Surgery By Watching

Learning to perform a job by watching others and copying their actions is not a great technique for corporate knowledge transfer. Christopher G. Myers suggests a better approach: Coactive vicarious learning. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Oct 2011

How ‘Hybrid’ Nonprofits Can Stay on Mission

As nonprofits add more for-profit elements to their business models, they can suffer mission drift. Associate Professor Julie Battilana says hybrid organizations can stay on target if they focus on two factors: the employees they hire and the way they socialize those employees. Key concepts include: In order to avoid mission drift, hybrid organizations need to focus on whom they hire and whether their employees are open to socialization. Because early socialization is so important, hybrid firms may be better off hiring new college graduates with no work background rather than a mix of seasoned bankers and social workers. The longer their tenure in a hybrid organization, the more likely top managers may be to hire junior people. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

Leadership development by failure: A case study

Posted by Jeff Russell | September 22 2016

To the extent that leadership is learned, it’s learned through experience. In his Model for Learning and Development , Morgan McCall of the University of Southern California argues that successful managers learn 10 percent from formal schooling and 20 percent from other people, compared to 70 percent from personal and professional experience. “Learning,” in this case, means gaining knowledge or acquiring a skill.

Experience is an ongoing process, and good leaders need to make the most of it. Some look but don’t see; some listen but don’t understand. As T.S. Eliot said, “We had the experience but missed the meaning.”

Experience necessarily involves failures, and you certainly shouldn’t miss the meaning of those. Failures can prepare you to be a leader—as long as you take the time to reflect on them. When you’re reflective, you think about outcomes and impact. You develop judgment.

By “failing,” I don’t mean simply “making a mistake. Failing can involve falling short in a duty or an expected action. It can also refer to a situation in which you don’t make the most of an opportunity. I’m all too familiar with both scenarios and can speak from personal experience about the benefits of failure.

Can’t do, need to do

I came from an athletic family, and in high school my identity was tied up in playing football. I spent the summer before senior year preparing for what I thought would be my crowning season as a fullback and cornerback. I was co-captain of the team and expected to play in college. On the first play of the first game, however, I tore up my knee and had to sit out the rest of the season.

That turn of events was not in the script, and it spelled the end of my college football dreams. What I took away from the experience is that you can’t control all outcomes. When disaster strikes, you have to move on to plan B.

For me, plan B was to pursue an education that would lead to becoming a faculty member in engineering. But from the get-go I faced a significant obstacle: I couldn’t write. I had trouble organizing my thoughts and didn’t understand basic syntax and grammar.

So I just hunkered down, developing my writing skills at every opportunity. I studied others’ papers and tried to figure out how they approached similar subjects. What outline did they use? How did they integrate figures and tables? How did they organize and package information? It took a while, but with practice—and feedback from many faculty members—I improved my writing.

The paradigm here is “can’t do; need to do.” I couldn’t write, but I needed to write to pursue a career in academia. In other words, I needed to face my deficiencies and get on with developing my skills.

Community matters

As an undergraduate at the University of Cincinnati, I walked into my first fluid mechanics class and knew I was in deep trouble. That class alone covered five chapters! I dropped the course, retook it, and dropped it again. Part of the problem was a lack of focus; part of it was a mental block. During my junior year I dropped out of college altogether, feeling like I couldn’t cut it.

I was in a ditch, and I couldn’t have pulled myself out without a hand from the engineering department’s chairman and secretary. These kind people provided encouragement, assuring me I wasn’t the first student to face such difficulties. Other patient faculty members helped me figure out a schedule to get back on track. Family and friends also encouraged me.

The lesson is that community matters. I realized that obtaining my civil engineering degree wouldn’t have been possible without this wonderful support network.

I moved on to Purdue for my master’s degree and, after one year, started work on my Ph.D. dissertation. I entered my preliminary examination feeling confident but underwent a brutal interrogation from my committee. They asked many questions I couldn’t answer, and after three long hours I considered leaving the room. I looked at my adviser and actually started crying.

Days later, he assured me that the committee members recognized my potential. They just wanted to show me that I didn’t know as much as I thought I did, and that pursuit of knowledge is an ongoing lifetime effort.

I got the point: “always be prepared, if not overprepared.” And keep learning, because you don’t know everything.

It takes a lot of noes to get to a yes

My rejections weren’t a total loss. I learned a lot about myself. I also learned how to communicate, how to understand what organizations need, and how to build relationships that would be useful in my career. In other words, achieving success wasn’t all that mattered; going through the process was valuable in and of itself.

The job search also showed me that it often takes a lot of noes to get to a yes.

The next step on my career progression was a run for chair of UW-Madison’s civil and environmental engineering department. I lost twice, then won, and immediately began pushing for changes in the department. My aggressive agenda caused enough discontent that I faced a challenger after only a year. I prevailed, but the lesson wasn’t lost on me: don’t get too far out ahead of the people you’re leading. It takes patience to manage the process of change.

Know when to move on

I’ll close with one last failure on the road to my current position as the dean of UW-Madison Continuing Studies and vice provost of Lifelong Learning. I became chair of a professional organization’s committee, tasked with rethinking the educational requirements for practicing civil engineers. Over the course of two decades the committee made progress in creating a model law, but we ran into roadblocks getting it adopted on the state level.

Finally, a leader from the organization informed me that “the committee needs new blood.” In other words, I was fired.

After all the work I’d put in, I was disappointed. There was still work to be done. But this was yet another failure worth reflecting on. I concluded that a leader must know when to move on. I should have stepped down earlier but had no sense of what I would do next. Since I hadn’t thought ahead, I kept working on the committee and couldn’t let go of it.

My takeaway: always have a transition plan.

Using position and influence wisely

I began with the idea that leadership is learned through experience, and I know that reading about someone else’s epiphanies can have only so much value. But I’ll end with three more lessons that I’ve found particularly useful in my career. I’ve learned each one in typical fashion—the hard way.

Treat people based upon who you are, not who they are or how they act. Leaders must be centered and know themselves.

To quote Maya Angelou, people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel. In other words, leaders must use their power wisely, especially in situations that are stressful and involve the lives of others.

To paraphrase Heraclitus, it’s not possible to step twice in the same river, or to come into contact twice with a mortal being in the same state. Life is an ongoing process, and none of us has arrived. We must, through experience, continue learning, observing, and growing.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

HBR Case Study: A Rush to Failure?

A complex project for the space station must come in on time and on budget—but the push for speed might be its undoing.

There is absolutely no reason why the contractors shouldn’t be able to give us rapid product development and flawless products—speed and quality both,” David MacDonagle said as he tried to light a cigarette. The warm wind, portending rain, kept blowing out his matches. Finally he gave up and slipped the cigarette back in his pocket.

- TC Tom Cross is a senior director in executive education at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, where he develops executive learning programs for Department of Defense leaders. Previously he was a senior executive at such firms as KFC and Office Depot.

Partner Center

MBA Knowledge Base

Business • Management • Technology

Home » Management Case Studies » Case Study of Nestle: Training and Development

Case Study of Nestle: Training and Development

Nestle is world’s leading food company, with a 135-year history and operations in virtually every country in the world. Nestle’s principal assets are not office buildings, factories, or even brands. Rather, it is the fact that they are a global organization comprised of many nationalities, religions, and ethnic backgrounds all working together in one single unifying corporate culture .

Culture at Nestle and Human Resources Policy

Nestle culture unifies people on all continents. The most important parts of Nestle’s business strategy and culture are the development of human capacity in each country where they operate. Learning is an integral part of Nestle’s culture. This is firmly stated in The Nestle Human Resources Policy, a totally new policy that encompasses the guidelines that constitute a sound basis for efficient and effective human resource management . People development is the driving force of the policy, which includes clear principles on non-discrimination, the right of collective bargaining as well as the strict prohibition of any form of harassment. The policy deals with recruitment , remuneration and training and development and emphasizes individual responsibility, strong leadership and a commitment to life-long learning as required characteristics for Nestle managers.

Training Programs at Nestle

The willingness to learn is therefore an essential condition to be employed by Nestle. First and foremost, training is done on-the-job. Guiding and coaching is part of the responsibility of each manager and is crucial to make each one progress in his/her position. Formal training programs are generally purpose-oriented and designed to improve relevant skills and competencies . Therefore they are proposed in the framework of individual development programs and not as a reward.

Literacy Training

Most of Nestle’s people development programs assume a good basic education on the part of employees. However, in a number of countries, we have decided to offer employees the opportunity to upgrade their essential literacy skills. A number of Nestle companies have therefore set up special programs for those who, for one reason or another, missed a large part of their elementary schooling.

These programs are especially important as they introduce increasingly sophisticated production techniques into each country where they operate. As the level of technology in Nestle factories has steadily risen, the need for training has increased at all levels. Much of this is on-the-job training to develop the specific skills to operate more advanced equipment. But it’s not only new technical abilities that are required. It’s sometimes new working practices. For example, more flexibility and more independence among work teams are sometimes needed if equipment is to operate at maximum efficiency .

“Sometimes we have debates in class and we are afraid to stand up. But our facilitators tell us to stand up because one day we might be in the parliament!” (Maria Modiba, Production line worker, Babelegi factory, Nestle South Africa).

Nestle Apprenticeship Program

Apprenticeship programs have been an essential part of Nestle training where the young trainees spent three days a week at work and two at school. Positive results observed but some of these soon ran into a problem. At the end of training, many students were hired away by other companies which provided no training of their own.

“My two elder brothers worked here before me. Like them, for me the Nestle Apprenticeship Program in Nigeria will not be the end of my training but it will provide me with the right base for further advancement. We should have more apprentices here as we are trained so well!” (John Edobor Eghoghon, Apprentice Mechanic, Agbara Factory, Nestle Nigeria) (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); “It’s not only a matter of learning bakery; we also learn about microbiology, finance, budgeting, costs, sales, how to treat the customer, and so on. That is the reason I think that this is really something that is going to give meaning to my life. It will be very useful for everything.” (Jair Andres Santa, Apprentice Baker, La Rosa Factory Dosquebradas, Nestle Columbia).

Local Training

Two-thirds of all Nestle employees work in factories, most of which organize continuous training to meet their specific needs. In addition, a number of Nestle operating companies run their own residential training centers. The result is that local training is the largest component of Nestle’s people development activities worldwide and a substantial majority of the company’s 240000 employees receive training every year. Ensuring appropriate and continuous training is an official part of every manager’s responsibilities and, in many cases; the manager is personally involved in the teaching. For this reason, part of the training structure in every company is focused on developing managers own coaching skills. Additional courses are held outside the factory when required, generally in connection with the operation of new technology.

The variety of programs is very extensive. They start with continuation training for ex-apprentices who have the potential to become supervisors or section leaders, and continue through several levels of technical, electrical and maintenance engineering as well as IT management. The degree to which factories develop “home-grown” specialists varies considerably, reflecting the availability of trained people on the job market in each country. On-the-job training is also a key element of career development in commercial and administrative positions. Here too, most courses are delivered in-house by Nestle trainers but, as the level rises, collaboration with external institutes increases.

“As part of the Young Managers’ Training Program I was sent to a different part of the country and began by selling small portions of our Maggi bouillon cubes to the street stalls, the ‘sari sari’ stores, in my country. Even though most of my main key accounts are now supermarkets, this early exposure were an invaluable learning experience and will help me all my life.” (Diane Jennifer Zabala, Key Account Specialist, Sales, Nestle Philippines). “Through its education and training program, Nestle manifests its belief that people are the most important asset. In my case, I was fortunate to participate in Nestle’s Young Managers Program at the start of my Nestle career, in 1967. This foundation has sustained me all these years up to my present position of CEO of one of the top 12 Nestle companies in the world.” (Juan Santos, CEO, Nestle Philippines)

Virtually every national Nestle company organizes management-training courses for new employees with High school or university qualifications. But their approaches vary considerably. In Japan, for example, they consist of a series of short courses typically lasting three days each. Subjects include human assessment skills, leadership and strategy as well as courses for new supervisors and new key staff. In Mexico, Nestle set up a national training center in 1965. In addition to those following regular training programs, some 100 people follow programs for young managers there every year. These are based on a series of modules that allows tailored courses to be offered to each participant. Nestle India runs 12-month programs for management trainees in sales and marketing, finance and human resources, as well as in milk collection and agricultural services. These involve periods of fieldwork, not only to develop a broad range of skills but also to introduce new employees to company organization and systems. The scope of local training is expanding. The growing familiarity with information technology has enabled “distance learning” to become a valuable resource, and many Nestle companies have appointed corporate training assistants in this area. It has the great advantage of allowing students to select courses that meet their individual needs and do the work at their own pace, at convenient times. In Singapore, to quote just one example, staff is given financial help to take evening courses in job-related subjects. Fees and expenses are reimbursed for successfully following courses leading to a trade certificate, a high school diploma, university entrance qualifications, and a bachelor’s degree.

International Training

Nestle’s success in growing local companies in each country has been highly influenced by the functioning of its International Training Centre, located near company’s corporate headquarters in Switzerland. For over 30 years, the Rive-Reine International Training Centre has brought together managers from around the world to learn from senior Nestle managers and from each other.Country managers decide who attends which course, although there is central screening for qualifications, and classes are carefully composed to include people with a range of geographic and functional backgrounds. Typically a class contains 15—20 nationalities. The Centre delivers some 70 courses, attended by about 1700 managers each year from over 80 countries. All course leaders are Nestle managers with many years of experience in a range of countries. Only 25% of the teaching is done by outside professionals, as the primary faculty is the Nestle senior management. The programs can be broadly divided into two groups:

- Management courses: these account for about 66% of all courses at Rive-Reine. The participants have typically been with the company for four to five years. The intention is to develop a real appreciation of Nestle values and business approaches. These courses focus on internal activities.

- Executive courses: these classes often contain people who have attended a management course five to ten years earlier. The focus is on developing the ability to represent Nestle externally and to work with outsiders. It emphasizes industry analysis, often asking: “What would you do if you were a competitor?”

Nestle’s overarching principle is that each employee should have the opportunity to develop to the maximum of his or her potential. Nestle do this because they believe it pays off in the long run in their business results, and that sustainable long-term relationships with highly competent people and with the communities where they operate enhance their ability to make consistent profits. It is important to give people the opportunities for life-long learning as at Nestle that all employees are called upon to upgrade their skills in a fast-changing world. By offering opportunities to develop , they not only enrich themselves as a company, they also make themselves individually more autonomous, confident, and, in turn, more employable and open to new positions within the company. Enhancing this virtuous circle is the ultimate goal of their training efforts at many different levels through the thousands of training programs they run each year.

External Links:

- Employee and Career Development (Nestle Global)

Related Posts:

- Case Study: Starbucks Growth Strategy

- Case Study: Kraft's Takeover of Cadbury

- Case Study: Organizational Structure and Culture of Virgin Group

- Case Study of Global Knowledge: Technology as an Effective Ingredient of Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

- Case Study: Wal-Mart's Failure in Germany

- Case Study of IBM: Employee Training through E-Learning

- Case Study: Marketing Strategy Analysis of Apple iPad

- Case Study: The Strategic Alliance Between Renault and Nissan

- Case Study: An Assessment of Wal-Mart's Global Expansion Strategy

- Case Study: L'Oreal Global Branding Strategy

4 thoughts on “ Case Study of Nestle: Training and Development ”

Very nice case study

one question, when is this case study published? please ,thank you. i am doing this for final year project. as references

Post date: 03-09-2010

How does Nestle evaluate the effectiveness of training programs? Explain your reasons

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Advertisement

Causal and Corrective Organisational Culture: A Systematic Review of Case Studies of Institutional Failure

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 28 September 2020

- Volume 174 , pages 457–483, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- E. Julie Hald 1 ,

- Alex Gillespie 1 &

- Tom W. Reader 1

14k Accesses

11 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Organisational culture is assumed to be a key factor in large-scale and avoidable institutional failures (e.g. accidents, corruption). Whilst models such as “ethical culture” and “safety culture” have been used to explain such failures, minimal research has investigated their ability to do so, and a single and unified model of the role of culture in institutional failures is lacking. To address this, we systematically identified case study articles investigating the relationship between culture and institutional failures relating to ethics and risk management ( n = 74). A content analysis of the cultural factors leading to failures found 23 common factors and a common sequential pattern. First, culture is described as causing practices that develop into institutional failure (e.g. poor prioritisation, ineffective management, inadequate training). Second, and usually sequentially related to causal culture, culture is also used to describe the problems of correction: how people, in most cases, had the opportunity to correct a problem and avert failure, but did not take appropriate action (e.g. listening and responding to employee concerns). It was established that most of the cultural factors identified in the case studies were consistent with survey-based models of safety culture and ethical culture. Failures of safety and ethics also largely involve the same causal and corrective factors of culture, although some aspects of culture more frequently precede certain outcome types (e.g. management not listening to warnings more commonly precedes a loss of human life). We propose that the distinction between causal and corrective culture can form the basis of a unified (combining both ethical and safety culture literatures) and generalisable model of organisational failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Integrating Cultural and Regulatory Factors in the Bowtie: Moving from Hand-Waving to Rigor

The Safety Culture Construct: Theory and Practice

Cultural Effects on the Selection of Aviation Safety Management Strategies

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scholars have long been interested in the role of culture as a causal factor in institutional failures, defined as a significant physical, financial, or social loss (Perrow 1999 ; Rasmussen 1997 ; Reason 1990 ; Turner 1978 ; Vaughan 1999 ). Institutional failures can be diverse in nature (e.g. accidents, scandals, bankruptcies), and culture is used to explain the shared values, beliefs, and assumptions which guide behaviour within an organisation and lead to poor outcomes (Schein 1984 ; Schneider et al. 2013 ; Ouchi and Wilkins 1985 ). Research on the cultural factors that lead to organisational failure has, largely, coalesced into two distinct paradigms: safety culture and ethical culture. These, respectively, examine how the management of risk and ethics within an organisation shape attitudes (e.g. of employees towards incident reporting or whistleblowing) and practices (e.g. risk-taking, unethical conduct) that contribute to large-scale failures (e.g. accidents, corruption) (e.g. Cooper 2000 ; Guldenmund 2000 ; Kaptein 2008 ). However, the extent to which theories of safety culture and ethical culture explain why organisational failures occur, and have identified the key psychological dimensions that account for problematic behaviour, is nascent. This is because studies of safety culture and ethical culture have tended to be prospective, for example using cross-sectional surveys to examine the relationship between employee beliefs (e.g. on norms for safe and ethical conduct) and behaviours (e.g. safety compliance, reporting ethical breaches). The role of safety culture and ethical culture in causing organisational failures is less well-established, and we investigate this in the current article through undertaking a systematic review of case study analyses using culture to understand institutional failures. We examine the utilisation and similarity of concepts from the safety and ethical culture literature to explain these failures, and propose a broader and more generalisable model on the role of causal and corrective organisational culture in institutional failures.

Organisational Culture and Its Relationship with Institutional Failure

There are pockets of consensus regarding how to define organisational culture. It is generally accepted that culture provides the rather stable and shared system of values, beliefs, and assumptions which provides approved modes of thought and behaviour, is resistant to change, and maintained through social interaction (Schall 1983 ; Schein 1984 ; Schneider et al. 2013 ). Schein ( 1984 ) further suggests culture is stratified by different levels of meaning, where the deepest level comprises the underlying and pervasive assumptions which organisational members tacitly accept, the intermediary level comprises what they espouse to believe, and the highest level consists of visible or audible patterns of behaviour and artefacts which are a manifestation of the other levels. Studies of culture divide according to whether they orient ethnographically to organisations “ as cultures,” or measure culture through surveys and questionnaires as a variable or “something an organisation has ” (Smircich 1983 , p. 347, original emphasis).

Various attributes and types of culture have been associated with financial performance (e.g. Denison 1984 ; O’Reilly et al. 2014 ). Barney ( 1986 ) suggests culture can afford a sustained competitive advantage if characterised by uncommon qualities which cannot be imitated by other organisations. Similarity in survey responses, as an indicator of cultural strength, has also been linked to performance (e.g. Denison 1990 ; Gordon and DiTomaso 1992 ). However, as Reason ( 1998 ) highlights, the very same processes of internal integration and external adaptation which maintain group cohesion and thus comprise the core function of a culture (Schein 2010 ) can threaten an organisation’s survival when applied to goals which undermine good practise. Namely, through normalising maladaptive behaviour, “cultures create problems as well as solving them” (Kroeber and Kluckhohn 1952 , p. 57). This duality corresponds to the sub-field of sociology which draws on Merton ( 1936 , 1940 , 1968 ) and Durkheim (1895/ 1966 ) to investigate how the same processes which produce positive organisational outcomes, are also responsible for the ‘dark side’ that generates mistakes, misconduct, and disaster (Vaughan 1999 ).

Institutional failure is “a physical, cultural, and emotional event incurring social loss, often possessing a dramatic quality that damages the fabric of social life” (Vaughan 1999 , p. 292). Concretely, it is typically used to refer to large-scale avoidable failures, for example accidents (e.g. Chernobyl, Deepwater Horizon) or scandals (e.g. Enron, Barings Bank), that have consequences for those within an organisation (e.g. employees), stakeholders (e.g. passengers, investors, the public), the environment (e.g. pollution), and integrity of an institution itself (e.g. collapse, or huge reputational damage). Within the diverse conceptual models that are used to explain failure, for example by Turner ( 1978 ; Turner and Pidgeon 1997 ), Reason ( 1990 , 2016 ), Perrow ( 1984 , 1999 ), and Rasmussen ( 1997 ), organisational culture is often a key element.

Turner ( 1978 ) was first to describe failure as a socio-technical phenomenon, rather than an event which is divine, coincidental, or purely technical (Turner and Pidgeon 1997 ). He conducted a systematic qualitative analysis of 84 British accident and disaster reports published between 1965 and 1975, developing a six-stage developmental sequence model of failure (‘man-made disaster’) as being preceded by several preconditions which develop during a ‘disaster incubation period.’ The incubation period involves the slow ‘accumulation’ of events which deviate from the culture’s beliefs and norms regarding hazards. This accumulation can continue for many years and is enabled by people’s incorrect assumptions about hazards, problems in information-handling, rigidities of perception, and inappropriate or outdated formal procedures. The incubation period ends when a ‘precipitating incident’ such as an explosion, fire, or plunge in share prices, exposes the actual state of affairs. Culture is at the centre of Turner’s model which equates failure sociologically to a cultural collapse (Pidgeon and O’Leary 2000 ). Yet, culture operates at a meta-level in the divergence between what people believe is an accurate perception of affairs, and what is actually true. This highlights how disaster occurs despite people believing they are taking the necessary precautions against failure, but does not identify common ways in which it is precipitated by specific cultural problems.

Reason’s ( 1990 , 2016 ) model of accident causation also considers the role of organisational culture. Reason posits an organisation’s layers of defence are somewhat akin to layers of Swiss cheese: each has gaps representing weaknesses, through which an accident ‘trajectory’ can pass if gaps momentarily align. Defence weaknesses are constantly moving, making their alignment—and thus failure—a rare occurrence (Reason 1998 ). Reason makes the useful distinction between the errors or violations at the ‘sharp-end’ of operations which ‘trigger’ failure (‘active failures’)—the final slice in the Swiss cheese model—and the latent error- and violation-producing conditions. Latent conditions include for example an emphasis on cost-cutting (e.g. understaffing), aspects of organisational structure and how business is conducted, inadequate hardware in terms of tools and equipment, poor system design, and procedures which are unclear or not applicable. They persist undetected and are a product of culture, as well as management decisions, and organisational processes. However, only culture is ubiquitous enough to influence all aspects of defence. Culture “can not only open gaps and weaknesses but also—and most importantly—it can allow them to remain uncorrected” (Reason 1998 , p. 297).

Culture is less focal in Perrow’s ( 1984 , 1999 ) theory of normal accidents which suggests failure is a normal and unpreventable part of organisational systems working with high-risk technology (e.g. nuclear power plants, air traffic control) because they are characterised by ‘tight coupling’ (e.g. little scope for slack, delays, and alternative procedures) and high ‘interactive complexity’ of system components. Perrow gives external forces of capitalism a larger role in failure than culture. He notes,

If culture plays a role, as many argue it does (…), it is not the most important one, and while efforts to change the culture to one that favors high reliability operations are certainly of high priority, restricting the catastrophic potential of our enterprises is of higher priority. (…) Rather than look to national cultures, or even to cultures of companies and the workplace, we might look at plain old free-market capitalism (Perrow 1999 , p. 416, original emphasis).

Perrow defines culture in positive terms as a source of reliability, and thus does not associate culture with the negative potential of adverse outcomes. Instead, this potential is attributed to external production pressures of the outside economic system. However, the ways in which an organisation manages the two opposing goals of efficiency and safety can shed light on what is valued and tolerated within an organisation (i.e. culture), and would explain why not all those operating in the same economic conditions experience failure.

Rasmussen ( 1997 ) includes culture as a possible preventative mechanism. According to Rasmussen ( 1997 ), organisations are constantly under pressure to maintain an acceptable workload, safe performance, and avoid economic failure. These are depicted as boundaries, where the organisation is at the centre, managing the tensions between them. The organisation moves toward the ‘functionally acceptable' (i.e. safe) performance boundary when it reduces employees’ workload or increases productivity. Errors and accidents occur if the organisation moves so far that it crosses the boundary of functionally acceptable performance. Rasmussen proposes that informational campaigns for safety culture can counter the pressures of efficiency and thus improve control of performance. Safety culture is defined in terms of people’s knowledge of the boundary of functionally acceptable performance. Like Perrow, this highlights the positive role of culture in fostering an awareness of risk and danger, but does not highlight the negative contributing aspects of culture.

In conclusion, different and seminal models of organisational failure view failure as something which emerges gradually and sequentially over several contributing factors (Reason 1990 ; Turner 1978 ). Organisational culture permeates these models through providing an explanatory framework for understanding the drivers of behaviour within an organisation (e.g. the values that underlie, and are expressed, through cost-cutting, incentivisation, system design, procedures), and explaining how norms and values towards risk (e.g. normalisation and tolerance) determine how managers and employees identify and respond to hazards. Subsequent research on the role of organisational culture in institutional failures has tended to focus on two domains: safety culture and ethical culture.

Safety Culture and Ethical Culture

Safety culture and ethical culture are the main cultural dimensions applied to investigate the relationship between culture and institutional failures (Cooper 2000 ; Guldenmund 2000 ; Kaptein 2008 ; Treviño and Weaver 2003 ). Although they focus on different sets of values (e.g. the importance of safety, adhering to ethical standards), behaviours (e.g. risk-taking, dishonesty), and outcomes (e.g. accidents, scandals), safety culture and ethical culture have many parallels in how they are used to explain organisational failures. For instance, both stress the importance of senior leadership in setting standards, supervisors in guiding behaviour, organisational and group norms in determining what practices are acceptable, giving employees the knowledge and skills to behave effectively, and ensuring employees can speak-up (and are listened to) when they raise concerns (Ardichvili and Jondle 2009 ; Guldenmund 2000 ; Kaptein 2011 ; Neal and Griffin 2002 ; Reader and O’Connor 2014 ; Zohar 2010 ). However, both models diverge in their origins, and the variables they use to explain organisational failures.

Interest in safety culture came from a shift in focus from models of causation to how crisis and risk management might be improved to provide institutional resilience (Pidgeon and O’Leary 2000 ). Safety culture relates to the norms and practises surrounding health and safety within an organisation (Cooper 2000 ; Guldenmund 2000 ), and is highly related to safety climate (perceptions on the priority of safety) (Zohar 2010 ). Pidgeon and O’Leary ( 2017 ) suggest a ‘good’ safety culture is characterised by senior management’s commitment to safety, a shared concern for hazards and how they impact people, realistic norms and procedures for managing risk, and continual processes of reflection and organisational learning. Safety culture gained traction in the 1980s to account for large-scale failures such as the Chernobyl nuclear disaster (Pidgeon 1998 ) and Piper Alpha oil rig explosion ( 1993 ) where shared patterns of belief and behaviour were found to have played a significant role in the disasters. In both cases, a prioritisation of other concerns (e.g. productivity) by senior managers led to operational decisions that weakened safety (e.g. on the use of resources, reduced safety inspections, pushing safety capabilities), the normalisation of unsafe practices (e.g. unsupervised staff undertaking maintenance routines), and a lack of preparedness for managing safety emergencies. By focussing accident investigations on the system and cultural context of organisations, safety culture theory departed from earlier research which had attributed accidents to fallible mental processes (e.g. forgetfulness, negligence) in individuals working directly with the system (Reason 2000 ). Rather, safety is understood as part of an organisation’s value-system, with the consideration of safety in everyday practices being a product of, and revealing, these values (Guldenmund 2000 ).

Interest in the domain of ethical culture has come about due to organisational failures that are considered a consequence of unethical conduct (e.g. scandals of Enron, LIBOR, and Odebrecht). Similar to safety culture, the concept of ethical culture emerges from the rationale that unethical acts within an organisation are likely to reflect values within an organisation for ethical conduct, rather than individual failings. This diverges from the perspective that unethical behaviour is determined by individual factors such as a person’s sensitivity to moral issues (Rest 1979 ), level of moral judgement (Kohlberg 1969 ), and guilt proneness (e.g. Cohen et al. 2012 ). Within the ethical culture framework, ethical behaviour is conceptualised as determined by immediate job pressures, institutional values and norms on the importance of ethics (e.g. for indicating the appropriateness of behaviours), and the embedding of these values into formal systems (e.g. rules and polices) (Treviño 1986 ; Treviño et al. 2014 ). As with safety culture, ethical culture is conceptualised as a subset of organisational culture, with specific domains of activity—for instance on transparency or the sanctioning of unethical behaviour—constituting an ethical culture (Kaptein 2008 ; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010 ). Furthermore, ethical culture is influenced by the values and behaviours of leaders (see Ardichvili and Jondle 2009 ), and associated through various dimensions with reported (un)ethical behaviour and intentions (e.g. Kaptein 2011 ; Sweeney et al. 2010 ; Zaal et al. 2019 ). Several contributing factors to ethical culture have been identified, including an organisational commitment to employees (Fernández and Camacho 2016 ), the presence of ethics programmes such as a dedicated ethics department or committee (Martineau et al. 2017 ), the role-modelling of ethical practises by management (Kaptein 2011 ), and reward systems that reinforce ethical behaviour (Treviño et al. 1998 ). Ethical climate, understood as the perceptions of organisational values for ethics (Victor and Cullen 1988 ), has been distinguished from ethical culture, which relates more to the systems of control that shape ethical behaviour (Kaptein 2011 ; Treviño et al. 1998 ). As the dimensions of ethical culture and ethical climate are highly related (Treviño et al. 1998 ), we, like others (e.g. Ardichvili and Jondle 2009 ), regard ethical climate as a sub-category of ethical culture.

The fields of both safety culture and ethical culture have arisen to explain organisational failures, and to investigate this, researchers in both fields have relied on psychometrically validated surveys (Guldenmund 2007 ; Kaptein 2008 ). These are used to measure employee perceptions of the culture (e.g. management commitment to safety, reporting safety incidents, clarity of expected conduct, reporting ethical concerns), with responses being associated at an individual, unit, or organisational level with adverse outcomes. For instance, research shows safety culture to be associated with safety behaviours, reporting, and lost-time injuries (Beus et al. 2016 ; Christian et al. 2009 ; Petitta et al. 2017 ), and ethical culture to be associated with ethical choices and reports of unethical behaviours (e.g. intentions to report misconduct) (Schaubroeck et al. 2012 ; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010 ; Kaptein 2011 ). Associations between safety culture and ethical culture and larger-scale organisational failures (e.g. corruption, process safety failures) are absent due to their rarity (e.g. in comparison to individual reports on behaviour), unpredictability (e.g. in identifying and accessing a failing organisation), and the challenges of expecting employees to recognise and report on sensitive topics like safety and ethics (e.g. Antonsen 2009a ; Arnold and Feldman 1981 ; Fischer and Fick 1993 ). Furthermore, whilst survey methods have provided valuable insight on ‘what’ cultural dimensions are associated with adverse outcomes, they have not necessarily shown ‘how’ various aspects of culture interact to create the conditions for failure. This is important because failure is defined by the nature of its sequential development through several events over time (Reason 1990 ; Turner 1978 ).

In summary, researchers have provided and validated conceptual models for measuring safety culture and ethical culture, and these models are the most widely used to understand the cultural conditions under which institutional failures occur. However, for reasons of methodology and data availability, both concepts are limited in the extent to which their underlying components are demonstrated and understood (e.g. in terms of sequence within an event) to have a role in explaining large-scale and avoidable institutional failures (e.g. accidents, scandals). Indeed, it is not clear that safety culture and ethical culture are entirely distinct in explaining failure: for example, investigations of hospital failures in the UK (e.g. Mid Staffordshire hospital, Shrewsbury and Telford hospital) have revealed a combination of poor safety culture (e.g. staff not reporting on sub-standard care) and poor ethical culture (e.g. dismissing patient concerns, concealing poor care) to have led to unnecessary patient deaths (Francis 2013 ; Lintern 2019 ). There may be aspects of organisational culture important for explaining institutional failures that are generalisable and not unique to either safety culture or ethical culture (e.g. reporting on concerns), or factors that are not considered within either model. To better explain the role of organisational culture in institutional failures, and specifically the contribution of safety culture and ethical culture, we undertake a systematic review of articles investigating the relationship between culture and institutional failures.

Current Study

In this study, we undertake an inductive content analysis of case studies investigating the role of organisational culture in institutional failures. Case study analyses draw on a multitude of secondary sources to understand causes of an institutional failure, including investigative reports, organisational documents, as well as first-person accounts, which only become available after a failure because of a need to establish what occurred (Cox and Flin 1998 ; Feagin et al. 1991 ). This mitigates the previously mentioned limitations with survey-based methods, and supports an approach which can consider the perspectives of all people and sub-cultures involved, enabling analysis of ‘how’ culture led to failure (Glendon and Stanton 2000 ; Tellis 1997 ). Given these methodological affordances, case studies may provide insight on the most commonly identified aspects of safety culture and ethical culture that underlie organisational failures, alongside identifying cultural factors not established within survey-based models of safety culture and ethical culture. Moreover, their inductive and retrospective nature offers the opportunity to determine whether failures of safety and ethics differ by the cultural factors they involve, or if the conceptual boundaries of safety culture and ethical culture become less distinct when considering failure. In this study, we systematically identify and analyse case studies of institutional failure in order to address four research questions. We define institutional failure as an event with multiple causes which had developed over time (Turner 1978 ; Turner and Pidgeon 1997 ).

First, we identify and extract the aspects of organisational culture reported as contributing to institutional failures. Our aim is to determine whether a common set of cultural factors can be established—from across the multiple and independent case studies—as leading to institutional failure. We think that establishing what cultural factors have been used to explain failure provides a logical starting point for our analysis because these cultural factors have not been systematically catalogued before and it will enable comparisons with existing models of safety culture, ethical culture, and failure.

Second, we examine how different cultural factors are used to explain institutional failure. We explore whether, as specified in various models of institutional failure (e.g. Reason 1990 ; Turner 1978 ), culture is used to both account for the organisational conditions that underlie failure (e.g. norms, values), and problems in responding to threats that endanger an organisation (e.g. a developing accident). This exploration of how culture is used to explain failure will shed light on the mechanisms by which culture contributes to failure. These mechanisms are beyond the scope of survey-based methods which measure cultural elements to the degree that they are present or absent (see Reason 2000 ).

Third, we consider the cultural factors identified in case studies of institutional failure in relation to the safety culture and ethical culture models. We investigate the extent to which the cultural factors identified by analyses of institutional failure map onto existing models of safety culture and ethical culture. We identify cultural factors not typically included with models of safety culture and ethical culture, and consider whether they indicate other aspects of organisational culture which may be important for explaining institutional failure. As a third step, this establishes the extent to which retrospective studies diverge from survey-based studies of safety culture and ethical culture.

Fourth, we examine whether the cultural factors identified as contributing to institutional failures vary according to failure-type (safety or ethics) and failure-outcome (e.g. loss of life, environmental damage). Here, we are interested in the extent to which models of safety culture and ethical culture are exclusive and explanatory of institutional failures, or whether a more generalisable model of institutional failure might be derived.

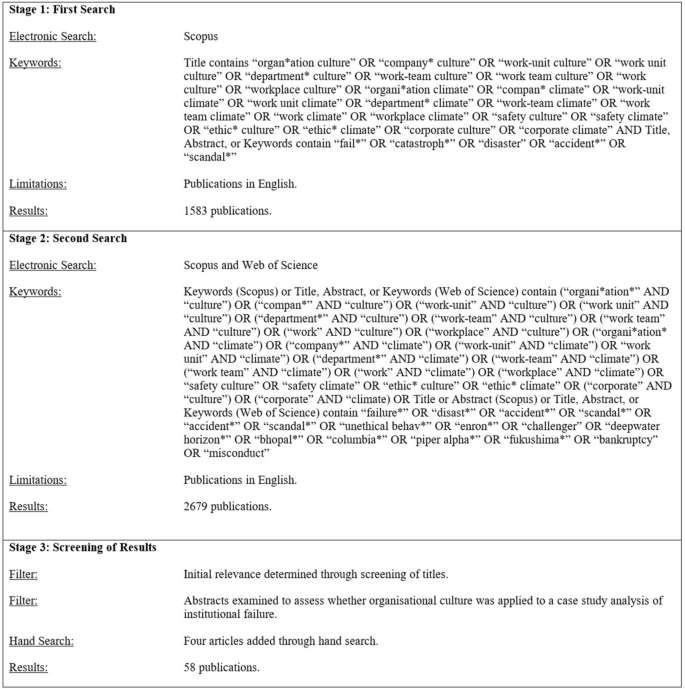

This is the first systematic review of case studies which use culture to account for the causation of institutional failure. Accordingly, there was no protocol available and the development of search terms was challenging given the literature on culture and failure is ill-defined and prone to differences in terminology. For stage 1, search terms were designed to ensure the primacy of organisational culture as a theoretical framework (see Fig. 1 ). Using Scopus and Web of Science, studies were identified if ‘organisational culture’ or an equivalent term (e.g. ‘organisational climate’) based on Schneider et al. ( 2013 ) featured in the title, and ‘failure’ or an equivalent term (e.g. ‘disaster’) featured in the title, abstract, or keywords. No date parameters were applied. Assessing the output revealed some issues with this first search. First, limiting the occurrence of ‘culture’ to title only included some studies not found otherwise, but excluded publications which mention culture only in the abstract or keywords. Second, studies which refer only to ‘culture’ or ‘climate’ were not identified because the search terms required more specificity (i.e. ‘organisational culture’). Third, it was evident that several studies name a high-profile failure rather than use a generic term like ‘failure.’

Procedure for study selection

For stage 2, the search for ‘organisational culture’ and ‘failure’ was expanded to keywords in Scopus, and title, abstract, and keywords in Web of Science. Studies were also identified if they specified failures (e.g. ‘Challenger’) in keywords (Scopus) or title, abstract, and keywords (Web of Science), or if they used specific text strings such as ‘culture at’ and ‘learn* from’ in the title or abstract (Scopus) and title, abstract, and keywords (Web of Science). Books and book chapters were initially included in this second Scopus search given knowledge of some seminal publications in the field (e.g. Vaughan 1996 ), but ultimately screened out for a more manageable extraction process. Differences in search fields across databases are owing to differences in search capabilities of Scopus and Web of Science. After removal of 771 duplicates, the final corpus consisted of 3,491 publications. The same search terms without the inclusion of ‘culture’ or ‘climate’ yielded 18,419 articles in Web of Science, and thus we can estimate that about 23% of case study research on organisational failure utilises culture concepts. Through screening of titles and abstracts, studies were included if they contained a case study of one or more institutional failures and employed organisational culture as a main theoretical framework. A hand search was conducted to ensure no relevant case studies had been omitted, and this led to the addition of articles by Bennett ( 2020 ), Merenda and Irwin ( 2018 ), Jung and Park ( 2017 ), and Reason ( 1998 ). The final corpus consisted of 58 articles.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The full-text of included articles was retrieved and extraction was carried out according to the four research questions. To establish what cultural factors are cited as contributing to institutional failure, a content analysis of included articles was carried out at the sentence-level. “Content analysis is a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff 2013 , p. 24). This content analysis was inductive because no pre-existing model of culture or climate was used to identify the cultural factors cited by case studies. Avoiding pre-conceived cultural factors was considered important for methodological integrity given the untraditional nature of this review. Cultural factors were collapsed based on similarity over three rounds of consolidation into 23 categories.

To establish how case studies use cultural factors to explain failure, each factor was additionally coded for the presence of preceding cultural causes and subsequent cultural outcomes (i.e. which it elicited or supported). Cultural factors were not double-coded unless they indexed distinct values or behaviours, and where it was necessary to capture the unconnected causes or outcomes of a single cultural factor.

To establish whether the cultural factors identified in case studies correspond to the items and dimensions of models of safety culture and ethical culture, we examined two reviews of safety culture and climate scales (Flin et al. 2000 ; Guldenmund 2000 ), two widely-cited models of ethical culture (Kaptein 2008 ; Treviño et al. 1998 ), and conducted additional literature searches where a cultural factor was not captured by these resources (e.g. Hessels and Wurmser 2020 ; Singhapakdi et al. 1996 ).

Finally, each failure analysed was coded according to type (i.e. safety or ethics) and outcome (e.g. environmental damage). The cultural factors cited in relation to each failure type and outcome were examined for patterns to see if any cultural factors are exclusively involved in safety failures or ethical failures and whether some aspects of culture more frequently precede specific failure outcomes.

Fifty-eight articles containing 74 case studies of 57 unique institutional failures were identified. The most common journal of publication was Safety Science (12.07%, n = 7; see “ Appendix ”). The culture models of safety culture (36.21%, n = 21), organisational culture (17.24%, n = 10), and corporate culture (13.79%, n = 8) were most frequent. Overall, the failures investigated were diverse, including: nuclear disasters, oil rig explosions, doping in professional sport, financial fraud, failures to adapt, poor planning, accidents in public transport, the hiring of incompetent staff, institutional abuse, espionage, hazardous spills, and fires. Case studies analysed failures of safety (55.41%, n = 41), ethics (41.89%, n = 31) and a third category of strategy (2.7% of case studies, n = 2).

Case studies predominantly investigated fraud (27.03%, n = 20), oil and gas spills (12.16%, n = 9), space shuttle disasters (12.16%, n = 9), nuclear disasters (8.11%, n = 6), and rail accidents (6.76%, n = 5). Recurrent failures were the accounting fraud at Enron (8.11%, n = 6), the disintegration of the Space Shuttle Columbia as it was entering the atmosphere (6.76%, n = 5), the disintegration of the Space Shuttle Challenger at 73 s after it lifted-off (5.41%, n = 4), and the Fukushima nuclear disaster (5.41%, n = 4). Overall, case studies spanned 15 sectors. Ten were encompassed by the Global Industry Classification Standard (MSCI and S&P Global Market Intelligence 2018 ) (see Fig. 2 ).

Case studies of institutional failure according to the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) with the additions of ‘Space exploration,’ ‘Government’, ‘Professional sports,’ ‘Education’, and ‘Military’

Establishing Whether a Common Set of Cultural Factors Contribute to Failure

To establish whether case studies identify a common set of cultural factors, we systematically coded and collapsed all cultural factors invoked by case studies. Twenty-three cultural factors were identified as contributing to failure, indicating that failure arises from a generally common set of values and practises (see Table 1 ).

The most common cultural factor was a problem in how priorities were ranked within the organisation. This predominantly involved safety or ethics being less prioritised in favour of profitability or productivity. For example, a focus on production at a meat supplier motivated poor hygiene practises and the repackaging of expired meat products, eventually causing a tragic E. coli O157 outbreak in South Wales (Griffith 2010 ). The focus on profit could also manifest as aggressiveness and an orientation towards competitiveness. At Enron, the lowest performing employees were annually let go in a ‘rank and yank system’ which created a ‘cut-throat’ culture of competition between employees that normalised accounting fraud (Cuong 2011 ; Froud et al. 2004 ). In all cases, productivity had short-term benefits with unforeseen long-term outcomes. This is illustrated by Reason ( 1998 ) who describes how competition between British warships in nineteenth century peacetime led to polishing practises which removed the watertight quality of doors, contributing to naval disasters such as the HMS Camperdown. As Reason ( 1998 ) notes, “peacetime ‘display culture’ not only undermined the Royal Navy’s fighting ability, it also created gleaming death traps” (p. 298). Being the most prevalent cultural factor in failure, it would be useful to know its preconditions. However, in the few cases where an underlying cause was given, the failure to prioritise safety and ethics was the outcome of forces outside an organisation’s control, including societal or national norms (e.g. neoliberalism; Behling et al. 2019 ; Kee et al. 2017 ), privatisation (Dien et al. 2004 ), and legislation (Behling et al. 2019 ).

Inadequate management was also a common cultural factor. Occasionally this involved aspects of leadership style and personality, such as the CEO being distant and unavailable to employees (Johnson 2008 ), exhibiting excessive confidence (Amernic and Craig 2013 ; Cervellati et al. 2013 ), divisiveness or dogmatism (Fallon and Cooper 2015 ). It also involved leaders pursuing inappropriate business strategies, such as undercutting competitors, resulting in an artificial market monopoly (Goh et al. 2010 ). However, inadequate management more frequently involved managers and supervisors not verifying that procedures and jobsites (i.e. operating standards) were maintained by employees. It also manifested in overly generous reward structures which encouraged unethical behaviour (e.g. Froud et al. 2004 ; Molina 2018 ). The large role attributed management must be considered in relation to inadequate board supervision which was less frequently cited. It may be that board effectiveness and composition are less consequential than adequate executive management to the prevention of adverse events (cf. Baysinger and Butler 1985 ; Uzun et al. 2004 ).

Training and Policy

The many problems related to training and policy reflect Reason’s ( 1990 ) idea that failure is triggered by the errors or violations of individuals dealing immediately with the system (Reason 1990 ; see also Robson et al. 2012 ; Schulte et al. 2003 ). Indeed, inadequate training of employees resulted in a workforce which lacked the ability to properly carry out tasks, causing behaviour that precipitated or facilitated failure. Unsurprisingly, inadequate training was often the outcome of cultural factors which reduced its apparent necessity, including cost-cutting and a focus on profit (e.g. Froud et al. 2004 ; MacLean et al. 2004 ), insufficient regulation (e.g. Crofts 2017 ; Kim et al. 2018 ), and a shared belief that failure was not possible anyway (e.g. Cervellati et al. 2013 , 1993 ; Reason 1998 ). For example, operators at Chernobyl had not been effectively trained in the dangers of nuclear power, and thus did not exercise appropriate caution (Reason 1998 ).

Problems of policy related to the content or availability of information about organisational procedures (e.g. Rafeld et al. 2019 ; Reader and O’Connor 2014 ). On the one hand, overly-proscriptive policy could deter employees from violating procedure even when a situation demanded it (e.g. Broadribb 2015 ). For example, a stringent culture of procedural compliance deterred the pilots of Swissair flight 111 from landing the aircraft as quickly as possible when inflight smoke was detected (McCall and Pruchnicki 2017 ). Policy could also give license to unethical practise through vagueness. As Sims and Brinkmann ( 2002 ) note, “[w]hen people are not sure what to do, unethical behaviour may flourish as aggressive individuals pursue what they believe to be acceptable” (p. 334).

Institutional change was the least-cited contributing factor to failure, indicating that failure may be more commonly the outcome of enduring beliefs and behaviour. Change contributed to failure where it clashed with or weakened an existing culture, for example a new CEO was a poor cultural fit (e.g. Johnson 2008 ) or administrative changes disrupted employees’ accustomed occupational roles (Lederman et al. 2015 ).

Speaking-Up System and Bullying

The availability of a medium was not the most important factor in employees speaking-up about problems to management. Case studies more frequently attributed employee silence to a fear of victimisation from bullying (e.g. Crofts 2017 ; Johnson 2008 ; Froud et al. 2004 ) and material retaliation such as being fired (e.g. Beamish 2000 ; Guthrie and Shayo 2005 ). This reflects the health problems associated with being bullied at work (e.g. Nielsen and Einarsen 2012 ; Einarsen and Skogstad 1996 ) and suggests that organisational responses to whistle-blowers are an important determinant of speaking-up behaviour.

Establishing whether Culture is Used in the Dynamic Sense of Failure Models

To establish whether usage of the concept of culture was congruent with the dynamic failure models of Reason ( 1998 ) and Turner ( 1978 ), we counted the number of factors cited and coded for possible sequential relationships between them. With a mean of 7.28 cultural factors cited per case study, usage of culture was in line with these failure models. Cultural factors were also frequently linked sequentially (87.84%, n = 65) and case studies typically cited more than one sequence of cultural factors (59.46%, n = 44). This reflects popular models of failure development which suggest the complex and dynamic nature of failure development (Reason 1990 ; Turner 1978 ) and is a divergence from survey-based studies of safety culture and ethical culture which commonly measure culture by its absence (see Reason 2000 ).

Sequences of cultural factors tended to consist of two cultural factors (77.03%, n = 57). Fewer case studies cited sequences of three (22.97%, n = 17), four (2.7%, n = 2), five (1.35%, n = 1), and six cultural factors (1.35%, n = 1). Importantly, sequential cultural factors were not necessarily consecutive. For example, in a case study of the Piper Alpha oil rig explosion, it was the combination of (a) inadequate regulation, (b) the primacy of production, and (c) disbelief that failure was possible, which together led to (d) design decisions that created (e) an unsafe physical work environment ( Paté-Cornell 1993 ).

Case studies used culture to explain failure in two ways. Most often culture described problematic values and practises that were endogenous to the culture and directly contributed to failure (93.24% of case studies, n = 69). This encompassed 15 of the 23 cultural factors, including: change, disbelief, employee satisfaction, the external environment, homogeneity, planning, priorities, procedure, management, regulation, resources, role-modelling, supervision, teamwork, and training and policy. These cultural factors can create the preconditions for failure to occur. Although we are not suggesting a new concept, they can be grouped into the category of ‘causal culture’ for ease of interpretation.

Culture was also used to explain why an organisation failed to correct a problem before it was able to develop into failure (72.97% of case studies, n = 54). Issues of corrective culture manifested as ‘problems dealing with problems.’ This encompassed eight of the 23 cultural factors, including: bullying, listening, learning, problem acceptance, problem response, rhetoric, speaking-up, and speaking-up system. These may be organised into the two categories of voicing and hearing. Voicing factors refer to the failure of employees to voice concerns about institutional problems to people in authority. Hearing factors refer to the failure by management to act on information received about institutional problems. This distinction maps onto the two critical phases of an organisation’s ‘adaptive capacity’: first, disruptive events need to be identified and relayed appropriately, and second, information must be heeded with the proper deployment of resources (Burnard and Bhamra 2011 ). Problems of corrective culture are distinct from other cultural factors because they do not advance the development of a failure. Instead, they represent missed opportunities to address a problem and potentially avert failure.

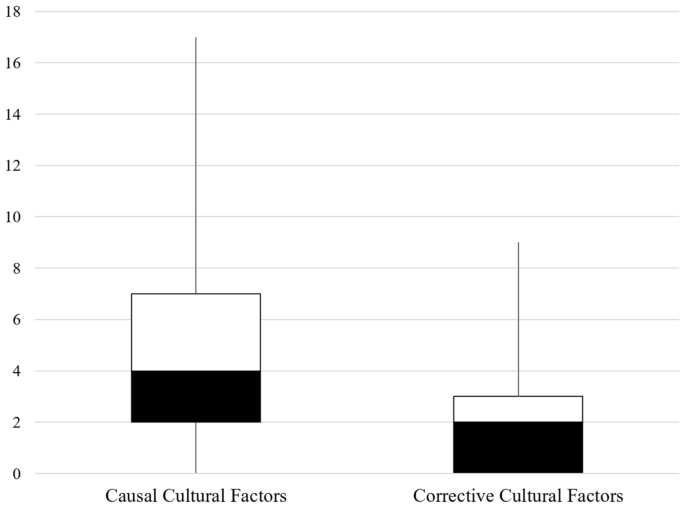

Case studies cite an average of 4.99 causal cultural factors and 2.3 corrective cultural factors. As depicted in Fig. 3 , the maximum number of causal and corrective factors cited by any case study is 17 and nine, respectively. Twenty case studies (27.03%) cite only causal factors, whilst five case studies (6.76%) describe failure arising from corrective factors alone. Indeed, 66.22 percent of case studies describe a combination of causal and corrective cultural factors. This indicates that failure commonly involves more aspects of causal culture, but that failure is typically also preceded by at least one missed opportunity to avert failure.

Frequency of causal and corrective cultural factors by case study

In summary, where studies of safety culture and ethical culture have prospectively measured culture through the perceptions of organisational members, case studies have retrospectively analysed how cultural factors interact in a sequential way to produce failure. Case studies thus reveal that, rather than exerting a top-down influence on behaviour, cultural factors divide according to whether they represent causes of failure or missed opportunities to avert failure. Indeed, a majority of case studies highlight that failures could have been prevented.

Establishing How Retrospective Case Studies Diverge from Survey-based Models of Safety Culture and Ethical Culture

Twenty of the 23 cultural factors which contribute to failure are typically part of models of safety culture (Flin et al. 2000 ; Guldenmund 2000 ; Hessels and Wurmser 2020 ) or ethical culture (Kaptein 2008 ; Singhapakdi et al. 1996 ; Treviño et al. 1998 ) (see Table 2 ). This indicates that case study analyses and survey-based studies largely overlap in the cultural factors they identify. However, three cultural factors—listening, bullying, and homogeneity—were novel, and are important to identify.

Listening is not typically measured by survey-based studies of safety culture and ethical culture. This is noteworthy given that a failure to listen to signs or information about problems is mentioned by a third of case studies. A diverse literature outside of culture recognises the importance of listening in organisations (e.g. Gillespie and Reader 2016 ). Some draw on the Foucauldian concept of ‘parrhesia’ (true speech) to analyse whistleblowing and listening (e.g. Catlaw et al. 2014 ; Vandekerckhove and Langenberg 2012 ; Weiskopf and Tobias-Miersch 2016 ). For instance, Vandekerckhove and Langenberg ( 2012 ) suggest that parrhesia in the workplace may not be heard because information typically travels up a hierarchy, requiring that a series of people have the courage to speak-up to the next person above them. Others use the term ‘deaf effect’ to understand when organisations persist with projects despite reports of trouble (Cueller et al. 2006 ; Keil and Robey 1999 ). Jones and Kelly ( 2014 ) suggest that when whistle-blowers are listened to, it can create a mutually-reinforcing cycle that benefits organisational learning, whilst ‘organisational disregard’ can create a norm of silence, preventing people from coming forward about other issues (see also Mannion and Davies 2018 ). Burris ( 2012 ) focusses on the information communicated and finds that managers are more likely to agree with information that supports rather than challenges the organisation’s goals, and that this relationship is mediated by the perceived loyalty and threat of voicing employees. Perceptions of management listening have also been linked to psychological safety and creativity (Castro et al. 2018 ).

The case studies indicate that not listening (i.e. not heeding information) was the outcome of culture in two ways (see Table 3 for examples). First, not listening occurred because the information received (i.e. X is unsafe or unethical ) conflicted with the receiver’s taken-for-granted assumptions about the world as a cultural member (i.e. X is safe, X is ethical, or failure cannot happen ), resulting in a breakdown of intersubjectivity (e.g. Grice 1975 ). Choo ( 2008 ) refers to this misalignment between information and available cognitive frame as an ‘epistemic blindspot.’ In terms of excluding employees from decision-making, this misalignment could cause employee involvement to be regarded as extraneous. Second, not listening occurred because the information, whilst decoded ‘correctly’ in terms of intent and content, conflicted with competing cultural values and demands. These include a pressure to maintain performance levels (e.g. Broadribb 2015 ; Mason 2004 ) and having to manage with limited resources (e.g. MacLean et al. 2004 ). Competing values and demands may also account for those cases where managers excluded employees from decision-making. Involving employees may conflict with organisational goals if employees communicate inconvenient information or deplete valued time.

Bullying is the second cultural factor not typically a part of models of safety culture and ethical culture. Bullying deterred employees from speaking-up about organisational problems (e.g. Dimeo 2014 ; Patrick et al. 2018 ). Bullying had pragmatic qualities somewhat similar to gossip: it was a form of social control directed at someone perceived to have transgressed the rules, which seemed to reinforce the group’s normative boundaries of right and wrong (Gluckman 1963 ; see also Waddington 2016 ). Bullying is naturally more hostile than gossip, and was indelibly dysfunctional because it enabled unsafe or unethical practises to persist and remain acceptable to (most) group members. As such bullying can have adverse outcomes for organisations, as well as individuals (e.g. self-esteem, Randle 2003 ; job satisfaction, Quine 1999 ).

The final cultural factor not typically a part of models of safety culture and ethical culture is workforce homogeneity (i.e. the absence of diversity). In the case studies, homogeneity was predominantly fostered through recruitment and promotion practises which rewarded unethical behaviour with a sense of belonging (Crawford et al. 2017 ) or (continued) employment (Fallon and Cooper 2015 ; Sims and Brinkmann 2002 , 2003 ). Homogeneity has been studied as a source of cultural strength, associated with more reliable performance in stable environments (Sørensen 2002 ), job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and less role stress (Barnes et al. 2006 ). Conversely, diversity research shows that demographic diversity amongst members of the board and management has a positive effect on financial performance (e.g. Erhardt et al. 2003 ), promotes cognitive diversity (see Horwitz 2005 ), and mitigates groupthink (Janis 1972 ). Indeed, strongly shared values and norms can be maladaptive (Syed 2019 ), but there is need to further conceptualise homogeneity as a cultural phenomenon that is conducive to failure.

In summary, whilst the cultural factors identified by case studies largely map onto models of safety culture and ethical culture, listening, bullying, and homogeneity as cultural phenomena need further research as they relate to adverse organisational events. However, the large overlap suggests failure and less severe events arise from a common set of cultural factors.

Establishing whether Cultural Factors vary by Failure and Outcome Type

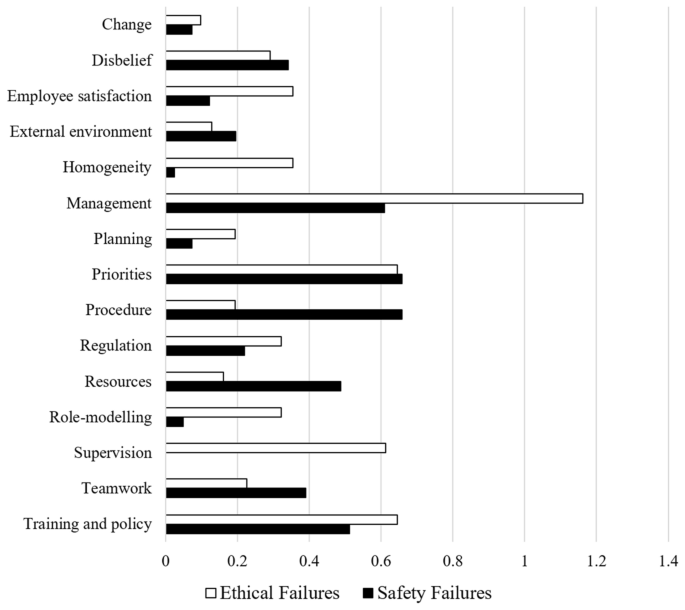

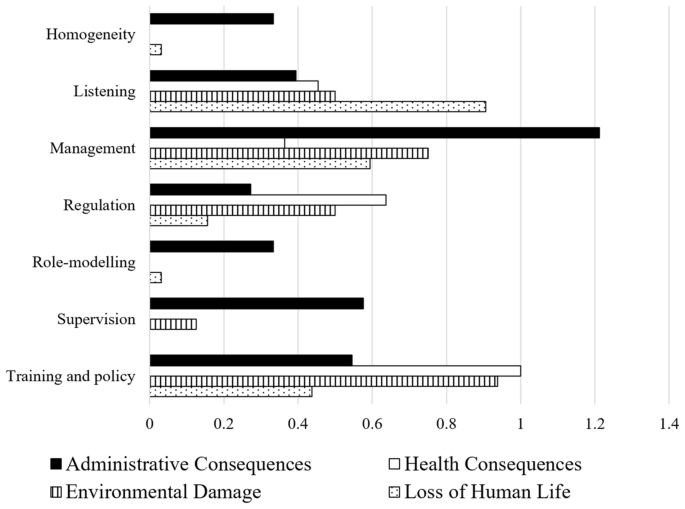

Cultural factors by failure-type.