New Data Show How the Pandemic Affected Learning Across Whole Communities

- Posted May 11, 2023

- By News editor

- Disruption and Crises

- Education Policy

- Evidence-Based Intervention

Today, The Education Recovery Scorecard , a collaboration with researchers at the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (CEPR) and Stanford University’s Educational Opportunity Project , released 12 new state reports and a research brief to provide the most comprehensive picture yet of how the pandemic affected student learning. Building on their previous work, their findings reveal how school closures and local conditions exacerbated inequality between communities — and the urgent need for school leaders to expand recovery efforts now.

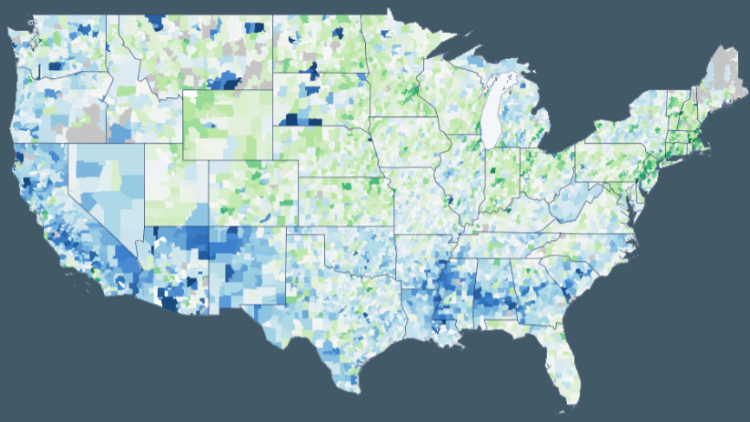

The research team reviewed data from 8,000 communities in 40 states and Washington, D.C., including 2022 NAEP scores and Spring 2022 assessments, COVID death rates, voting rates, and trust in government, patterns of social activity, and survey data from Facebook/Meta on family activities and mental health during the pandemic.

>> Read an op-ed by researchers Tom Kane and Sean Reardon in the New York Times .

They found that where children lived during the pandemic mattered more to their academic progress than their family background, income, or internet speed. Moreover, after studying instances where test scores rose or fell in the decade before the pandemic, the researchers found that the impacts lingered for years.

“Children have resumed learning, but largely at the same pace as before the pandemic. There’s no hurrying up teaching fractions or the Pythagorean theorem,” said CEPR faculty director Thomas Kane . “The hardest hit communities — like Richmond, Virginia, St. Louis, Missouri, and New Haven, Connecticut, where students fell behind by more than 1.5 years in math — have to teach 150 percent of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row — just to catch up. That is simply not going to happen without a major increase in instructional time. Any district that lost more than a year of learning should be required to revisit their recovery plans and add instructional time — summer school, extended school year, tutoring, etc. — so that students are made whole. ”

“It’s not readily visible to parents when their children have fallen behind earlier cohorts, but the data from 7,800 school districts show clearly that this is the case,” said Sean Reardon , professor of poverty and inequality, Stanford Graduate School of Education. “The educational impacts of the pandemic were not only historically large, but were disproportionately visited on communities with many low-income and minority students. Our research shows that schools were far from the only cause of decreased learning — the pandemic affected children through many ways — but they are the institution best suited to remedy the unequal impacts of the pandemic.”

The new research includes:

- A research brief that offers insights into why students in some communities fared worse than others.

- An update to the Education Recovery Scorecard, including data from 12 additional states whose 2022 scores were not available in October. The project now includes a district-level view of the pandemic’s effects in 40 states (plus D.C.).

- A new interactive map that highlights examples of inequity between neighboring school districts.

Among the key findings:

- Within the typical school district, the declines in test scores were similar for all groups of students, rich and poor, white, Black, Hispanic. And the extent to which schools were closed appears to have had the same effect on all students in a community, regardless of income or race.

- Test scores declined more in places where the COVID death rate was higher, in communities where adults reported feeling more depression and anxiety during the pandemic, and where daily routines of families were most significantly restricted. This is true even in places where schools closed only very briefly at the start of the pandemic.

- Test score declines were smaller in communities with high voting rates and high Census response rates — indicators of what sociologists call “institutional trust.” Moreover, remote learning was less harmful in such places. Living in a community where more people trusted the government appears to have been an asset to children during the pandemic.

- The average U.S. public school student in grades 3-8 lost the equivalent of a half year of learning in math and a quarter of a year in reading.

The researchers also looked at data from the decade prior to the pandemic to see how students bounced back after significant learning loss due to disruption in their schooling. The evidence shows that schools do not naturally bounce back: Affected students recovered 20–30% of the lost ground in the first year, but then made no further recovery in the subsequent three to four years.

“Schools were not the sole cause of achievement losses,” Kane said. “Nor will they be the sole solution. As enticing as it might be to get back to normal, doing so will just leave the devastating increase in inequality caused by the pandemic in place. We must create learning opportunities for students outside of the normal school calendar, by adding academic content to summer camps and after-school programs and adding an optional 13th year of schooling.”

The Education Recovery Scorecard is supported by funds from Citadel founder and CEO Kenneth C. Griffin, Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the Walton Family Foundation.

The latest research, perspectives, and highlights from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Despite Progress, Achievement Gaps Persist During Recovery from Pandemic

New research finds achievement gaps in math and reading, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, remain and have grown in some states, calls for action before federal relief funds run out

New Research Provides the First Clear Picture of Learning Loss at Local Level

To Get Kids Back on Track After COVID: Shoot for the Moon

- Our Mission

Covid-19’s Impact on Students’ Academic and Mental Well-Being

The pandemic has revealed—and exacerbated—inequities that hold many students back. Here’s how teachers can help.

The pandemic has shone a spotlight on inequality in America: School closures and social isolation have affected all students, but particularly those living in poverty. Adding to the damage to their learning, a mental health crisis is emerging as many students have lost access to services that were offered by schools.

No matter what form school takes when the new year begins—whether students and teachers are back in the school building together or still at home—teachers will face a pressing issue: How can they help students recover and stay on track throughout the year even as their lives are likely to continue to be disrupted by the pandemic?

New research provides insights about the scope of the problem—as well as potential solutions.

The Achievement Gap Is Likely to Widen

A new study suggests that the coronavirus will undo months of academic gains, leaving many students behind. The study authors project that students will start the new school year with an average of 66 percent of the learning gains in reading and 44 percent of the learning gains in math, relative to the gains for a typical school year. But the situation is worse on the reading front, as the researchers also predict that the top third of students will make gains, possibly because they’re likely to continue reading with their families while schools are closed, thus widening the achievement gap.

To make matters worse, “few school systems provide plans to support students who need accommodations or other special populations,” the researchers point out in the study, potentially impacting students with special needs and English language learners.

Of course, the idea that over the summer students forget some of what they learned in school isn’t new. But there’s a big difference between summer learning loss and pandemic-related learning loss: During the summer, formal schooling stops, and learning loss happens at roughly the same rate for all students, the researchers point out. But instruction has been uneven during the pandemic, as some students have been able to participate fully in online learning while others have faced obstacles—such as lack of internet access—that have hindered their progress.

In the study, researchers analyzed a national sample of 5 million students in grades 3–8 who took the MAP Growth test, a tool schools use to assess students’ reading and math growth throughout the school year. The researchers compared typical growth in a standard-length school year to projections based on students being out of school from mid-March on. To make those projections, they looked at research on the summer slide, weather- and disaster-related closures (such as New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina), and absenteeism.

The researchers predict that, on average, students will experience substantial drops in reading and math, losing roughly three months’ worth of gains in reading and five months’ worth of gains in math. For Megan Kuhfeld, the lead author of the study, the biggest takeaway isn’t that learning loss will happen—that’s a given by this point—but that students will come back to school having declined at vastly different rates.

“We might be facing unprecedented levels of variability come fall,” Kuhfeld told me. “Especially in school districts that serve families with lots of different needs and resources. Instead of having students reading at a grade level above or below in their classroom, teachers might have kids who slipped back a lot versus kids who have moved forward.”

Disproportionate Impact on Students Living in Poverty and Students of Color

Horace Mann once referred to schools as the “great equalizers,” yet the pandemic threatens to expose the underlying inequities of remote learning. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center analysis , 17 percent of teenagers have difficulty completing homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection. For Black students, the number spikes to 25 percent.

“There are many reasons to believe the Covid-19 impacts might be larger for children in poverty and children of color,” Kuhfeld wrote in the study. Their families suffer higher rates of infection, and the economic burden disproportionately falls on Black and Hispanic parents, who are less likely to be able to work from home during the pandemic.

Although children are less likely to become infected with Covid-19, the adult mortality rates, coupled with the devastating economic consequences of the pandemic, will likely have an indelible impact on their well-being.

Impacts on Students’ Mental Health

That impact on well-being may be magnified by another effect of school closures: Schools are “the de facto mental health system for many children and adolescents,” providing mental health services to 57 percent of adolescents who need care, according to the authors of a recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics . School closures may be especially disruptive for children from lower-income families, who are disproportionately likely to receive mental health services exclusively from schools.

“The Covid-19 pandemic may worsen existing mental health problems and lead to more cases among children and adolescents because of the unique combination of the public health crisis, social isolation, and economic recession,” write the authors of that study.

A major concern the researchers point to: Since most mental health disorders begin in childhood, it is essential that any mental health issues be identified early and treated. Left untreated, they can lead to serious health and emotional problems. In the short term, video conferencing may be an effective way to deliver mental health services to children.

Mental health and academic achievement are linked, research shows. Chronic stress changes the chemical and physical structure of the brain, impairing cognitive skills like attention, concentration, memory, and creativity. “You see deficits in your ability to regulate emotions in adaptive ways as a result of stress,” said Cara Wellman, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Indiana University in a 2014 interview . In her research, Wellman discovered that chronic stress causes the connections between brain cells to shrink in mice, leading to cognitive deficiencies in the prefrontal cortex.

While trauma-informed practices were widely used before the pandemic, they’re likely to be even more integral as students experience economic hardships and grieve the loss of family and friends. Teachers can look to schools like Fall-Hamilton Elementary in Nashville, Tennessee, as a model for trauma-informed practices .

3 Ways Teachers Can Prepare

When schools reopen, many students may be behind, compared to a typical school year, so teachers will need to be very methodical about checking in on their students—not just academically but also emotionally. Some may feel prepared to tackle the new school year head-on, but others will still be recovering from the pandemic and may still be reeling from trauma, grief, and anxiety.

Here are a few strategies teachers can prioritize when the new school year begins:

- Focus on relationships first. Fear and anxiety about the pandemic—coupled with uncertainty about the future—can be disruptive to a student’s ability to come to school ready to learn. Teachers can act as a powerful buffer against the adverse effects of trauma by helping to establish a safe and supportive environment for learning. From morning meetings to regular check-ins with students, strategies that center around relationship-building will be needed in the fall.

- Strengthen diagnostic testing. Educators should prepare for a greater range of variability in student learning than they would expect in a typical school year. Low-stakes assessments such as exit tickets and quizzes can help teachers gauge how much extra support students will need, how much time should be spent reviewing last year’s material, and what new topics can be covered.

- Differentiate instruction—particularly for vulnerable students. For the vast majority of schools, the abrupt transition to online learning left little time to plan a strategy that could adequately meet every student’s needs—in a recent survey by the Education Trust, only 24 percent of parents said that their child’s school was providing materials and other resources to support students with disabilities, and a quarter of non-English-speaking students were unable to obtain materials in their own language. Teachers can work to ensure that the students on the margins get the support they need by taking stock of students’ knowledge and skills, and differentiating instruction by giving them choices, connecting the curriculum to their interests, and providing them multiple opportunities to demonstrate their learning.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

11 Questions to Ask About COVID-19 Research

Debates have raged on social media, around dinner tables, on TV, and in Congress about the science of COVID-19. Is it really worse than the flu? How necessary are lockdowns? Do masks work to prevent infection? What kinds of masks work best? Is the new vaccine safe?

You might see friends, relatives, and coworkers offer competing answers, often brandishing studies or citing individual doctors and scientists to support their positions. With so much disagreement—and with such high stakes—how can we use science to make the best decisions?

Here at Greater Good , we cover research into social and emotional well-being, and we try to help people apply findings to their personal and professional lives. We are well aware that our business is a tricky one.

Summarizing scientific studies and distilling the key insights that people can apply to their lives isn’t just difficult for the obvious reasons, like understanding and then explaining formal science terms or rigorous empirical and analytic methods to non-specialists. It’s also the case that context gets lost when we translate findings into stories, tips, and tools, especially when we push it all through the nuance-squashing machine of the Internet. Many people rarely read past the headlines, which intrinsically aim to be relatable and provoke interest in as many people as possible. Because our articles can never be as comprehensive as the original studies, they almost always omit some crucial caveats, such as limitations acknowledged by the researchers. To get those, you need access to the studies themselves.

And it’s very common for findings and scientists to seem to contradict each other. For example, there were many contradictory findings and recommendations about the use of masks, especially at the beginning of the pandemic—though as we’ll discuss, it’s important to understand that a scientific consensus did emerge.

Given the complexities and ambiguities of the scientific endeavor, is it possible for a non-scientist to strike a balance between wholesale dismissal and uncritical belief? Are there red flags to look for when you read about a study on a site like Greater Good or hear about one on a Fox News program? If you do read an original source study, how should you, as a non-scientist, gauge its credibility?

Here are 11 questions you might ask when you read about the latest scientific findings about the pandemic, based on our own work here at Greater Good.

1. Did the study appear in a peer-reviewed journal?

In peer review, submitted articles are sent to other experts for detailed critical input that often must be addressed in a revision prior to being accepted and published. This remains one of the best ways we have for ascertaining the rigor of the study and rationale for its conclusions. Many scientists describe peer review as a truly humbling crucible. If a study didn’t go through this process, for whatever reason, it should be taken with a much bigger grain of salt.

“When thinking about the coronavirus studies, it is important to note that things were happening so fast that in the beginning people were releasing non-peer reviewed, observational studies,” says Dr. Leif Hass, a family medicine doctor and hospitalist at Sutter Health’s Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland, California. “This is what we typically do as hypothesis-generating but given the crisis, we started acting on them.”

In a confusing, time-pressed, fluid situation like the one COVID-19 presented, people without medical training have often been forced to simply defer to expertise in making individual and collective decisions, turning to culturally vetted institutions like the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Is that wise? Read on.

2. Who conducted the study, and where did it appear?

“I try to listen to the opinion of people who are deep in the field being addressed and assess their response to the study at hand,” says Hass. “With the MRNA coronavirus vaccines, I heard Paul Offit from UPenn at a UCSF Grand Rounds talk about it. He literally wrote the book on vaccines. He reviewed what we know and gave the vaccine a big thumbs up. I was sold.”

From a scientific perspective, individual expertise and accomplishment matters—but so does institutional affiliation.

Why? Because institutions provide a framework for individual accountability as well as safety guidelines. At UC Berkeley, for example , research involving human subjects during COVID-19 must submit a Human Subjects Proposal Supplement Form , and follow a standard protocol and rigorous guidelines . Is this process perfect? No. It’s run by humans and humans are imperfect. However, the conclusions are far more reliable than opinions offered by someone’s favorite YouTuber .

Recommendations coming from institutions like the CDC should not be accepted uncritically. At the same time, however, all of us—including individuals sporting a “Ph.D.” or “M.D.” after their names—must be humble in the face of them. The CDC represents a formidable concentration of scientific talent and knowledge that dwarfs the perspective of any one individual. In a crisis like COVID-19, we need to defer to that expertise, at least conditionally.

“If we look at social media, things could look frightening,” says Hass. When hundreds of millions of people are vaccinated, millions of them will be afflicted anyway, in the course of life, by conditions like strokes, anaphylaxis, and Bell’s palsy. “We have to have faith that people collecting the data will let us know if we are seeing those things above the baseline rate.”

3. Who was studied, and where?

Animal experiments tell scientists a lot, but their applicability to our daily human lives will be limited. Similarly, if researchers only studied men, the conclusions might not be relevant to women, and vice versa.

Many psychology studies rely on WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic) participants, mainly college students, which creates an in-built bias in the discipline’s conclusions. Historically, biomedical studies also bias toward gathering measures from white male study participants, which again, limits generalizability of findings. Does that mean you should dismiss Western science? Of course not. It’s just the equivalent of a “Caution,” “Yield,” or “Roadwork Ahead” sign on the road to understanding.

This applies to the coronavirus vaccines now being distributed and administered around the world. The vaccines will have side effects; all medicines do. Those side effects will be worse for some people than others, depending on their genetic inheritance, medical status, age, upbringing, current living conditions, and other factors.

For Hass, it amounts to this question: Will those side effects be worse, on balance, than COVID-19, for most people?

“When I hear that four in 100,000 [of people in the vaccine trials] had Bell’s palsy, I know that it would have been a heck of a lot worse if 100,000 people had COVID. Three hundred people would have died and many others been stuck with chronic health problems.”

4. How big was the sample?

In general, the more participants in a study, the more valid its results. That said, a large sample is sometimes impossible or even undesirable for certain kinds of studies. During COVID-19, limited time has constrained the sample sizes.

However, that acknowledged, it’s still the case that some studies have been much larger than others—and the sample sizes of the vaccine trials can still provide us with enough information to make informed decisions. Doctors and nurses on the front lines of COVID-19—who are now the very first people being injected with the vaccine—think in terms of “biological plausibility,” as Hass says.

Did the admittedly rushed FDA approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine make sense, given what we already know? Tens of thousands of doctors who have been grappling with COVID-19 are voting with their arms, in effect volunteering to be a sample for their patients. If they didn’t think the vaccine was safe, you can bet they’d resist it. When the vaccine becomes available to ordinary people, we’ll know a lot more about its effects than we do today, thanks to health care providers paving the way.

5. Did the researchers control for key differences, and do those differences apply to you?

Diversity or gender balance aren’t necessarily virtues in experimental research, though ideally a study sample is as representative of the overall population as possible. However, many studies use intentionally homogenous groups, because this allows the researchers to limit the number of different factors that might affect the result.

While good researchers try to compare apples to apples, and control for as many differences as possible in their analyses, running a study always involves trade-offs between what can be accomplished as a function of study design, and how generalizable the findings can be.

The Science of Happiness

What does it take to live a happier life? Learn research-tested strategies that you can put into practice today. Hosted by award-winning psychologist Dacher Keltner. Co-produced by PRX and UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

You also need to ask if the specific population studied even applies to you. For example, when one study found that cloth masks didn’t work in “high-risk situations,” it was sometimes used as evidence against mask mandates.

However, a look beyond the headlines revealed that the study was of health care workers treating COVID-19 patients, which is a vastly more dangerous situation than, say, going to the grocery store. Doctors who must intubate patients can end up being splattered with saliva. In that circumstance, one cloth mask won’t cut it. They also need an N95, a face shield, two layers of gloves, and two layers of gown. For the rest of us in ordinary life, masks do greatly reduce community spread, if as many people as possible are wearing them.

6. Was there a control group?

One of the first things to look for in methodology is whether the population tested was randomly selected, whether there was a control group, and whether people were randomly assigned to either group without knowing which one they were in. This is especially important if a study aims to suggest that a certain experience or treatment might actually cause a specific outcome, rather than just reporting a correlation between two variables (see next point).

For example, were some people randomly assigned a specific meditation practice while others engaged in a comparable activity or exercise? If the sample is large enough, randomized trials can produce solid conclusions. But, sometimes, a study will not have a control group because it’s ethically impossible. We can’t, for example, let sick people go untreated just to see what would happen. Biomedical research often makes use of standard “treatment as usual” or placebos in control groups. They also follow careful ethical guidelines to protect patients from both maltreatment and being deprived necessary treatment. When you’re reading about studies of masks, social distancing, and treatments during the COVID-19, you can partially gauge the reliability and validity of the study by first checking if it had a control group. If it didn’t, the findings should be taken as preliminary.

7. Did the researchers establish causality, correlation, dependence, or some other kind of relationship?

We often hear “Correlation is not causation” shouted as a kind of battle cry, to try to discredit a study. But correlation—the degree to which two or more measurements seem connected—is important, and can be a step toward eventually finding causation—that is, establishing a change in one variable directly triggers a change in another. Until then, however, there is no way to ascertain the direction of a correlational relationship (does A change B, or does B change A), or to eliminate the possibility that a third, unmeasured factor is behind the pattern of both variables without further analysis.

In the end, the important thing is to accurately identify the relationship. This has been crucial in understanding steps to counter the spread of COVID-19 like shelter-in-place orders. Just showing that greater compliance with shelter-in-place mandates was associated with lower hospitalization rates is not as conclusive as showing that one community that enacted shelter-in-place mandates had lower hospitalization rates than a different community of similar size and population density that elected not to do so.

We are not the first people to face an infection without understanding the relationships between factors that would lead to more of it. During the bubonic plague, cities would order rodents killed to control infection. They were onto something: Fleas that lived on rodents were indeed responsible. But then human cases would skyrocket.

Why? Because the fleas would migrate off the rodent corpses onto humans, which would worsen infection. Rodent control only reduces bubonic plague if it’s done proactively; once the outbreak starts, killing rats can actually make it worse. Similarly, we can’t jump to conclusions during the COVID-19 pandemic when we see correlations.

8. Are journalists and politicians, or even scientists, overstating the result?

Language that suggests a fact is “proven” by one study or which promotes one solution for all people is most likely overstating the case. Sweeping generalizations of any kind often indicate a lack of humility that should be a red flag to readers. A study may very well “suggest” a certain conclusion but it rarely, if ever, “proves” it.

This is why we use a lot of cautious, hedging language in Greater Good , like “might” or “implies.” This applies to COVID-19 as well. In fact, this understanding could save your life.

When President Trump touted the advantages of hydroxychloroquine as a way to prevent and treat COVID-19, he was dramatically overstating the results of one observational study. Later studies with control groups showed that it did not work—and, in fact, it didn’t work as a preventative for President Trump and others in the White House who contracted COVID-19. Most survived that outbreak, but hydroxychloroquine was not one of the treatments that saved their lives. This example demonstrates how misleading and even harmful overstated results can be, in a global pandemic.

9. Is there any conflict of interest suggested by the funding or the researchers’ affiliations?

A 2015 study found that you could drink lots of sugary beverages without fear of getting fat, as long as you exercised. The funder? Coca Cola, which eagerly promoted the results. This doesn’t mean the results are wrong. But it does suggest you should seek a second opinion : Has anyone else studied the effects of sugary drinks on obesity? What did they find?

It’s possible to take this insight too far. Conspiracy theorists have suggested that “Big Pharma” invented COVID-19 for the purpose of selling vaccines. Thus, we should not trust their own trials showing that the vaccine is safe and effective.

But, in addition to the fact that there is no compelling investigative evidence that pharmaceutical companies created the virus, we need to bear in mind that their trials didn’t unfold in a vacuum. Clinical trials were rigorously monitored and independently reviewed by third-party entities like the World Health Organization and government organizations around the world, like the FDA in the United States.

Does that completely eliminate any risk? Absolutely not. It does mean, however, that conflicts of interest are being very closely monitored by many, many expert eyes. This greatly reduces the probability and potential corruptive influence of conflicts of interest.

10. Do the authors reference preceding findings and original sources?

The scientific method is based on iterative progress, and grounded in coordinating discoveries over time. Researchers study what others have done and use prior findings to guide their own study approaches; every study builds on generations of precedent, and every scientist expects their own discoveries to be usurped by more sophisticated future work. In the study you are reading, do the researchers adequately describe and acknowledge earlier findings, or other key contributions from other fields or disciplines that inform aspects of the research, or the way that they interpret their results?

Greater Good’s Guide to Well-Being During Coronavirus

Practices, resources, and articles for individuals, parents, and educators facing COVID-19

This was crucial for the debates that have raged around mask mandates and social distancing. We already knew quite a bit about the efficacy of both in preventing infections, informed by centuries of practical experience and research.

When COVID-19 hit American shores, researchers and doctors did not question the necessity of masks in clinical settings. Here’s what we didn’t know: What kinds of masks would work best for the general public, who should wear them, when should we wear them, were there enough masks to go around, and could we get enough people to adopt best mask practices to make a difference in the specific context of COVID-19 ?

Over time, after a period of confusion and contradictory evidence, those questions have been answered . The very few studies that have suggested masks don’t work in stopping COVID-19 have almost all failed to account for other work on preventing the disease, and had results that simply didn’t hold up. Some were even retracted .

So, when someone shares a coronavirus study with you, it’s important to check the date. The implications of studies published early in the pandemic might be more limited and less conclusive than those published later, because the later studies could lean on and learn from previously published work. Which leads us to the next question you should ask in hearing about coronavirus research…

11. Do researchers, journalists, and politicians acknowledge limitations and entertain alternative explanations?

Is the study focused on only one side of the story or one interpretation of the data? Has it failed to consider or refute alternative explanations? Do they demonstrate awareness of which questions are answered and which aren’t by their methods? Do the journalists and politicians communicating the study know and understand these limitations?

When the Annals of Internal Medicine published a Danish study last month on the efficacy of cloth masks, some suggested that it showed masks “make no difference” against COVID-19.

The study was a good one by the standards spelled out in this article. The researchers and the journal were both credible, the study was randomized and controlled, and the sample size (4,862 people) was fairly large. Even better, the scientists went out of their way to acknowledge the limits of their work: “Inconclusive results, missing data, variable adherence, patient-reported findings on home tests, no blinding, and no assessment of whether masks could decrease disease transmission from mask wearers to others.”

Unfortunately, their scientific integrity was not reflected in the ways the study was used by some journalists, politicians, and people on social media. The study did not show that masks were useless. What it did show—and what it was designed to find out—was how much protection masks offered to the wearer under the conditions at the time in Denmark. In fact, the amount of protection for the wearer was not large, but that’s not the whole picture: We don’t wear masks mainly to protect ourselves, but to protect others from infection. Public-health recommendations have stressed that everyone needs to wear a mask to slow the spread of infection.

“We get vaccinated for the greater good, not just to protect ourselves ”

As the authors write in the paper, we need to look to other research to understand the context for their narrow results. In an editorial accompanying the paper in Annals of Internal Medicine , the editors argue that the results, together with existing data in support of masks, “should motivate widespread mask wearing to protect our communities and thereby ourselves.”

Something similar can be said of the new vaccine. “We get vaccinated for the greater good, not just to protect ourselves,” says Hass. “Being vaccinated prevents other people from getting sick. We get vaccinated for the more vulnerable in our community in addition for ourselves.”

Ultimately, the approach we should take to all new studies is a curious but skeptical one. We should take it all seriously and we should take it all with a grain of salt. You can judge a study against your experience, but you need to remember that your experience creates bias. You should try to cultivate humility, doubt, and patience. You might not always succeed; when you fail, try to admit fault and forgive yourself.

Above all, we need to try to remember that science is a process, and that conclusions always raise more questions for us to answer. That doesn’t mean we never have answers; we do. As the pandemic rages and the scientific process unfolds, we as individuals need to make the best decisions we can, with the information we have.

This article was revised and updated from a piece published by Greater Good in 2015, “ 10 Questions to Ask About Scientific Studies .”

About the Authors

Jeremy Adam Smith

Uc berkeley.

Jeremy Adam Smith edits the GGSC’s online magazine, Greater Good . He is also the author or coeditor of five books, including The Daddy Shift , Are We Born Racist? , and (most recently) The Gratitude Project: How the Science of Thankfulness Can Rewire Our Brains for Resilience, Optimism, and the Greater Good . Before joining the GGSC, Jeremy was a John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University.

Emiliana R. Simon-Thomas

Emiliana R. Simon-Thomas, Ph.D. , is the science director of the Greater Good Science Center, where she directs the GGSC’s research fellowship program and serves as a co-instructor of its Science of Happiness and Science of Happiness at Work online courses.

You May Also Enjoy

How to Form a Pandemic Pod

How to Keep the Greater Good in Mind During the Coronavirus Outbreak

Why Is COVID-19 Killing So Many Black Americans?

In a Pandemic, Elbow Touches Might Keep Us Going

Why Your Sacrifices Matter During the Pandemic

How Does COVID-19 Affect Trust in Government?

- Research Note

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2024

Determining the challenges and opportunities of virtual teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed method study in the north of Iran

- Aram Ghanavatizadeh 1 ,

- Ghahraman Mahmoudi 1 ,

- Mohammad-Ali Jahani 2 ,

- Seyedeh Niko Hashemi 3 ,

- Hossein-Ali Nikbakht 2 ,

- Mahdi Abbasi 4 ,

- Alameh Darzi 5 &

- Seyed-Amir Soltani 6

BMC Research Notes volume 17 , Article number: 148 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

47 Accesses

Metrics details

The aim of this study was to determine the challenges and opportunities of virtual education during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was conducted in 2022–2023 with a mixed method. During the quantitative phase, we chose 507 students from Mazandaran Province medical universities (both governmental and non-governmental) by stratified random sampling and during the qualitative phase 16 experts were collected by purposive sampling until we reached data saturation. Data collecting tools consisted of questionnaires during the quantitative phase and semi-structured interview during the qualitative phase. Data was analyzed using SPSS21 and MAXQDA10. Mean scores of the total score was 122.28±23.96. We found a significant association between interaction dimension and background variables ( P < 0.001). The most important privilege of virtual education is uploading the teaching material in the system so that students can access the material constantly and the most important challenge regarding virtual education is lack of proper network connection and limited bandwidth. Virtual education proved to be a suitable alternate to traditional methods of medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic in theoretical topics, we recommend that educational policymakers would take the necessary actions to provide the requirements and facilities needed to improve the quality of virtual education.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Given the adoption of technological advances in healthcare in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the dissemination of telehealth practices has dramatically increased between 2020 and 2021 [ 1 ]. Virtual education serves as a dynamic substitute for learners to constantly continue their educational journey and preserve their goals [ 2 ].

Virtual education is defined as the use of computer-based technology to provide education which consists of online learning, offline learning, or a combination of them [ 3 ]. In the web-based virtual educational platforms, students can continue to participate in the live academic lectures which they used to attend in class [ 4 ]. Virtual education varies significantly from in-person education [ 5 ]. The unavailability of necessary infrastructure and effective organizational strategies have been a major challenge for the integration of virtual education and face-to-face education [ 6 ]; [ 7 ] and this pandemic not only created the need but also provided the opportunity for accelerating digital transformation in medical education [ 8 ]. Using virtual education, learners can save and review the lectures whenever and wherever they want to. however, most professors have less experience with virtual teaching [ 9 ]. In this educational model, social interactions between the teachers and the students are solely through internet. Yet, how can a professor provide all the necessary communication, guidance, and feedback through internet alone so that learning process would be effective? Moreover, how can professors make sure that all students have access to the same content and same feedback equally? There are so many online educational activities that not all students can access equally due to differences in network conditions and inequal internet access [ 10 ]. Internet inequality could be defined as inequal distribution or access to the internet [ 11 ]. However, internet-based learning should be adjusted to different educational modalities so it would be effective [ 12 ]. Online education has played an important role in the education of undergraduate and graduate level students, and even continuing medical education (CME) of graduate doctors [ 13 ]. Learners can participate in the educational classes anytime it suits them [ 14 ].

one study conducted in Saudi Arabia revealed that using web-based video conferences during COVID-19 pandemic resulted in medical students’ satisfaction [ 15 ]. In another study by Cataudella et al. in Italy titled “Teaching During the COVID-19 Pandemic” showed that teachers exhibited lower self-esteem and self-efficacy while teaching virtually [ 16 ]. Rossi et al.’s study in Brazil demonstrated that active learning tools are helpful for students during the pandemic and they have succeeded at improving their critical thinking, motivation, and their contribution to science [ 17 ]. Khalili’s study in the United States showed that e-learning is becoming the new norm in the universities and this development can bring challenges to some, because some teachers lack the proper knowledge and expertise to create an supportive, positive and interesting environment to engage their students [ 18 ].

Currently the question is whether the implementation of virtual education has been able to satisfy students in their academic progress? Because learners are important stakeholders during the entire teaching and learning process in all educational institutions [ 19 ] and learners’ engagement in this process has positive effects on their active learning [ 20 ]. Therefore, due to widespread use of virtual education and online teaching during the pandemic, it is necessary to conduct more studies to examine the challenges and opportunities of this type of education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

Study design.

The current study was conducted using a mixed (qualitative-quantitative) method in 2022–2023 in the north of Iran.

Sample size

The study population in the quantitative phase consisted of 13,500 medical science students of all the medical universities in the province, both public and private, who benefited from virtual education during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the qualitative phase the population included experts and university professors of the same aforementioned universities.

In order to determine the sample size, it is appropriate to use between 5 and 15 observations for each variable measured [ 21 ], in this study we considered between 12 and 13 times the number of questions in the questionnaire, that is in the range of 480 and 520 participants.

The sampling method implemented in the quantitative phase was cluster sampling; first the university, then the academic major, and finally the class was considered as the cluster. 507 students were selected. 194 students from Babol university, 225 students from Sari university of Medical Sciences, and 88 students from Azad university of Sari participated in this research. Inclusion criteria in quantitative phase of this study was that participants had to be a student in one of the medical universities of Mazandaran and also to have consent to participate in the study. participants were excluded if they did not use online education methods.

In the qualitative phase we selected 16 academic staff members of both basic science and clinical stage, using purposive sampling, who were policymakers and planners in their universities and had online educational activities alongside their executive posts.

Information gathering tools

After our proposal was accepted and we obtained the ethics committee approval, we commenced our executive phase of the research. For the literature review all the articles that were published between 2010 and 2021 in different national and international databases including ISI, Pubmed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Magiran, SID, and Irandoc were reviewed. We used Persian and English keywords including online teaching, virtual teaching, active learning, COVID-19, interaction in virtual education, feedback in online education, benefits of virtual learning, disadvantages of virtual learning, and types of virtual learning.

Data measurement tools

In the quantitative phase we used a questionnaire developed by Ünal Çakiroğlu and colleagues [ 22 ]. The questionnaire consists of 7 different principles. Each principle consists of approximately 5–6 questions and a total of 40 questions and answers vary between range of not satisfied to perfectly satisfied and each question has a score of 1 to 5.

In order to convert the English questionnaire to Persian we used the translation-retranslation method as described below. At first, two translator’s experts in this field translated the English version into Farsi. A conceptual translation instead of word-to-word translation was implemented; also, clarity, simplicity, brevity, type of audience, age and cultural factors were taken into consideration by the translators. In the second stage two translators fluent in English, who were not aware of the questionnaire’s content, translated the questionnaire back into English. In general, conceptual similarity was an important factor during the translation process. finally, in the third stage an expert panel consisting of people fluent in both languages reviewed the quality of the translations in the presence of researchers and in the case of inconsistency between translations, alternative words were suggested.

To perform face validity, the questionnaire was given to 20 students (10 males and 10 females) who met the inclusion criteria and a number of related experts. They were asked for feedback about the clarity of the questionnaire, its readability, writing style, easy understanding, confusing words, comprehensibility, disproportion and ambiguity. Any needed corrections were applied.

To check the reliability, Cronbach’s alpha was used as the index to evaluate internal consistency for the entire questionnaire and for each scale. Values above 0.7 were considered acceptable. To evaluate intraclass reliability, we used test-retest method. Data from 30 students, who met the inclusion criteria, were collected in two stages with a time interval of one month then the scores obtained in these two stages were evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

To perform the qualitative phase, the data collection tool was semi-structured interview. We used the data from the quantitative phase of the study, the quantitative statistical outputs and items in the questionnaire that had the lowest points from the students’ point of view to formulate our interview questions. In the way that less favorable items from the students’ point of view were used as questions in the qualitative phase. At this point we used semi-structured interview and in-depth interview to gather our data. After conducting the interviews, handwriting, typing and listening to the files several times all the notes and writings were named and coded. in the initial coding process, the researcher reviewed the written and typed data line by line as analytical units; and then by identifying the related semantic units or determining the important parts of the text, the researchers would extract the explicit meanings and concepts from the interview texts and would write them next to the relevant sentence in the form of a code. At the same time in another text the researcher wrote down the codes with the relevant address.

Data analysis

After collecting the data and coding, the results of the quantitative phase were entered into the SPSS21 software. In order to perform the related statistical tests, first, the normality of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In order to check the linear relationships between quantitative variables, Pearson correlation coefficient was used. Friedman’s test was used to rank principals and dimensions at a significance level of p < 0.05. For analysis of the qualitative phase, content analysis method and MAXQDA10 software were carried out.

Results of the quantitative phase

From the 507 students participating in this study, regarding the demographic characteristics, the mean age of the participants was 21.47 ± 2.34 years with a range of 18 to 43 years. 319(62.92%) females and 174(34.32%) males participated in the study. The majority of the participants 145(28.6%) were medical students. (Table 1 )

Descriptive statistics of the scores of principles and dimensions of the questionnaire showed that the mean and standard deviation of the total score is 122.28±23.96 and for the three dimensions of interaction, learning and teaching. They were 34.54±8.23, 33.80±8.01 and 53.93±10.15. (Table 2 )

The results of the test about the correlation of the seven principles of the questionnaire showed that all seven principles had a positive correlation with each other and the correlation was of strong intensity. The strongest relationship was between high expectations and diverse talents ( r = 0.73, p < 0.001). The lowest correlations were found between cooperation among students and the time on task with other principles, the rest of the correlations are provided in the table. (Table 3 )

Also, in examining the relationship between the three dimensions of the questionnaire, the results showed that the highest correlation was between learning with teaching ( r = 0.786, P < 0.001) and the lowest correlation was between interaction with learning ( r = 0.666, P < 0.001), The correlation between teaching and interaction was ( r = 0.738, P < 0.001).

The result of the Friedman test showed that from the participants’ point of view, there was a difference between dimensions of online teaching including interaction, teaching and learning. In other words, according to participants, online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic had the best performance in teaching and the weakest performance in learning. (Table 4 )

The results of the qualitative phase

In the qualitative phase of the research, interview method was used to collect the data. The characteristics of the interview participants are provided in Table 5 .

In Table 6 , there are Strengths, opportunities and challenges of virtual education according to experts. Some solutions were suggested to improve this teaching method.

Qualitative phase data analysis

One of the most important opportunities of virtual teaching according to experts is the possibility of uploading the educational material in the electronic domains. The most important challenge of virtual teaching was the lack of proper and desirable communication infrastructure (internet) and poor-quality internet. The first solution proposed by the professors to increase the quality and efficacy of online teaching is recognizing the problems related to this educational method. the most important influential weakness of this method was the lack of proper communication and internet infrastructure.

The results of the study showed that all the principles of the study were positively correlated to each other and this relation was strong. The strongest relation was between high expectations and diverse talents and also between active learning and diverse talents. The least correlation was between cooperation among students and time on activity with other principles. In a study conducted by Alahmadi et al. it was shown that students believe online classes help them overcome some learning obstacles for example the fear of communication in English. One can argue that virtual classes are helping learners, especially timid learners, to interact more and overcome their fears of interaction in face-to-face classes [ 23 ]. Tanis article revealed that quick interaction between peers is helpful for their learning, whereas isolation and lack of communication was harmful, However, group project was not the best way of learning. Students found delayed feedback and limited work by their peers harmful for learning and preferred to work at their own pace [ 24 ].

In investigating the relationship between different principles, the strongest relationship was between teaching and learning and the least relation was between interaction and learning. Alenezi study mentions that it is necessary to design an effective electronic learning environment in which the content is presented based on the characteristics of the teachers and learners, the structure of the educational material and interaction creation [ 25 ]. In another study by Adnan et al. inaccessibility to internet, lack of proper interaction among teachers and learners and inefficient technology were the major challenges of students [ 26 ].

The results of the Friedman test in the present study showed that there are differences between various dimensions of virtual teaching including interaction, teaching and learning. In other words, online teaching has had the best performance in the teaching dimension and the weakest in the learning dimension during the COVID-19 pandemic. Çakiroğlu observed in his study that although the electronic learning system has advantages, there are still challenges related to the cooperation between students, and active learning was very low in virtual education [ 22 ]. Other studies showed that active learning using simulations improves conceptual learning and memory, increases motivation and study intensity, and also reduces the achievement gap in basic students [ 27 , 28 ].

According to the results of the study, one of the most important opportunities of virtual teaching is the ability to upload the teaching material in the electronic system, because it enables the students to receive and use the material as many times as they need to; this will eventually result in improvement of learning quality provided that we address the issues and challenges related to this process [ 29 ]. In electronic teaching, educational content can be quickly delivered to learners and standardized and updated if necessary. The material can be delivered using different approaches including self-directed and coaching [ 30 ].

Another strong point in online and virtual education was the increased ability of professors in working with different educational software, uploading assignments, holding online exams, and learning different ways of feedback. In Bjekic’s study, a teacher’s capability in electronic teaching is considered a combination of educational, communicational and content creation capability [ 31 ] and teacher’s ability to conduct better tests results in students’ satisfaction [ 32 , 33 ]. In this regard the faculty can use both online and offline tools for the education of students [ 34 ]. However, we should keep in mind that medical education is not solely the theoretical matters, there are also other aspects of teaching including laboratory techniques, clinical skills and patient exposure; so electronic methods alone will not be sufficient for medical education [ 35 ].

One of the other opportunities provided by virtual teaching is decreased expenses of both teachers and students due to less commute and the easy access of students to their professors through social network and also lack of limitations because of geographical distance between one individual’s residence and the place of their institute, Fedynich states that one of the advantages of remote education is that it is not limited by the learners’ location [ 36 ], also, it can be provided by the professors regardless of their location [ 37 ], it decreases students’ expenses [ 33 , 38 ] and students can ask questions whenever they have trouble with their studies and receive answers in a short amount of time and they can also see questions asked by others [ 39 ].

Of the important challenges regarding virtual education, we can mention the lack of proper communication infrastructure (internet) and low-quality internet which can affect the quality of online classes as well as examinations. An important weakness of virtual teaching is inaccessibility to digital products needed for the education by the students [ 40 ]. Not having reliable internet connection [ 41 , 42 ], hardware and software issues of virtual educational platforms [ 43 , 44 ], problems related to speed and quality of internet [ 45 , 46 ] and audio and video streaming issues are other disadvantages of this teaching method [ 47 ].

Another engagement of professors in online education is the topic of conducting online examinations, because they believe online platforms do not hold the capacity to perform reliable and valid examinations, the results of several studies showed that due to the lack of supervision during the test, students’ grades are significantly higher compared to their previous educational records [ 37 , 48 , 49 ]. On the contrary, in Lara et al.’s study scores recorded from 49 medical students in OSCE did not have a significant difference from scores obtained from the same exam conducted in-person [ 50 ], it seems like there is a difference between the nature of theoretical and applied examinations.

The other challenge was organizing practical courses and clinical rotations. Due to several infrastructural and human limitations, holding online practical classes was not possible, and students passing their clinical rotations or those who had applied courses faced many problems. In this regard, the main issue is due to the very nature of medical education and the main problem is the inability to practice and obtain clinical skills online [ 51 ]. Clinical courses have suffered from the suspension/reduction of undergraduate student internships with a knock on impact on education. The fulfilment of professional skills in clinical training present both educational and professional challenges. Medical teachers will need to innovate and think outside the box to maintain the value of medical education in extreme circumstances. A solution may be represented and the introduction of telemedicine technologies that may contribute to the improvement of core competencies, medical knowledge, overall learning, and higher quality patient care [ 52 ]. We should keep in mind that online education cannot replace the face-to-face education of laboratory skills and techniques [ 53 ]. And most students do not feel good about learning practical skills alone or online [ 39 ].

Study limitations

This study was limited to Mazandaran Province. Also, the study population was limited to the students of the Medical Sciences universities. On the other hand, we evaluated all academic levels together, and considering the fact that challenges are different in various stages of training and in different majors this may affect the overall results. For example, students in their clinical rotations have very different problems than those passing theoretical courses and topics.

Since virtual education proved to be a suitable replacement for traditional educational methods in theoretical subjects during the COVID-19 pandemic and considering the recognition of factors affecting the quality of virtual teaching; it is crucial for policymakers in the field of education to take these factors into consideration, and implement goal-oriented plans and do their best to provide the necessary requirements to improve the quality of virtual teaching, so that it ultimately leads to an increase in the quality of learning of medical students.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Poitras M-E, Couturier Y, Beaupré P, Girard A, Aubry F, Vaillancourt VT, et al. Collaborative practice competencies needed for telehealth delivery by health and social care professionals: a scoping review. J Interprof Care. 2023;1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2023.2213712

Dung DTH. The advantages and disadvantages of virtual learning. IOSR J Res Method Educ. 2020;10(3):45–8. https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-1003054548

Article Google Scholar

Shanahan MC. Transforming information search and evaluation practices of undergraduate students. Int J Med Informatics. 2008;77(8):518–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.10.004 . 26.

Gurgel BCV, Borges SB, Borges REA, Calderon PS. COVID-19: perspectives for the management of dental care and education. J Appl Oral Sci. 2020;28. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7757-2020-0358

Durán R, Estay-Niculcar C, Álvarez H. Adopción De buenas prácticas en la educación virtual en la educación superior. Aula Abierta. 2015;43(2):77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aula.2015.01.001

Chauhan S, Gilbert D, Hughes A, Kennerley Z, Phillips C, Davies A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on provision of antimicrobial stewardship education and training in UK health service sites. J Interprof Care. 2023;37(3):519–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2022.2082393

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Abedi M, Abedi D. A letter to the editor: the impact of COVID-19 on intercalating and non-clinical medical students in the UK. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1771245. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2020.1771245

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ebner M, Schön S, Braun C, Ebner M, Grigoriadis Y, Haas M, et al. COVID-19 epidemic as E-learning boost? Chronological development and effects at an Austrian university against the background of the concept of E-Learning readiness. Future Internet. 2020;12(6):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi12060094

Farooq I, Ali S, Moheet IA, AlHumaid J. COVID-19 outbreak, disruption of dental education, and the role of teledentistry. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2020;36(7):1726. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.7.3125

Rhodes A. Lowering barriers to active learning: a novel approach for online instructional environments. Adv Physiol Educ. 2021;45(3):547–53. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00009.2021

Van Deursen AJ. Digital inequality during a pandemic: quantitative study of differences in COVID-19–related internet uses and outcomes among the general population. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e20073. https://doi.org/10.2196/20073

Evans DJ, Bay BH, Wilson TD, Smith CF, Lachman N, Pawlina W. Going virtual to support anatomy education: a STOPGAP in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13(3):279–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1963

Gao J, Yang L, Zou J, Fan X. Comparison of the influence of massive open online courses and traditional teaching methods in medical education in China: a meta-analysis. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2021;49(4):639–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21523

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Cojocariu V-M, Lazar I, Nedeff V, Lazar G. SWOT anlysis of e-learning educational services from the perspective of their beneficiaries. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2014;116:1999–2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.510

Fatani TH. Student satisfaction with videoconferencing teaching quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02310-2

Cataudella S, Carta SM, Mascia ML, Masala C, Petretto DR, Agus M, et al. Teaching in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: a pilot study on teachers’ self-esteem and self-efficacy in an Italian sample. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):8211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158211

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rossi IV, de Lima JD, Sabatke B, Nunes MAF, Ramirez GE, Ramirez MI. Active learning tools improve the learning outcomes, scientific attitude, and critical thinking in higher education: experiences in an online course during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2021;49(6):888–903. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21574

Khalili H. Online interprofessional education during and post the COVID-19 pandemic: a commentary. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(5):687–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1792424

Mathew VN, Chung E. University Students’ perspectives on Open and Distance Learning (ODL) implementation amidst COVID-19. Asian J Univ Educ. 2020;16(4):152–60. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v16i4.11964

Gismalla MD-A, Mohamed MS, Ibrahim OSO, Elhassan MMA, Mohamed MN. Medical students’ perception towards E-learning during COVID 19 pandemic in a high burden developing country. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02811-8

Reisy L, Ziaee S, Mohamad E. Designing a questionnaire for diagnosis of vaginismus and determining its validity and reliability. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2015;25(125):81–94. (In persian). http://jmums.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-5900-en.html

Google Scholar

Çakýroglu Ü. Evaluating students’ perspectives about virtual classrooms with regard to seven principles of good practice. South Afr J Educ. 2014;34(2). https://doi.org/10.15700/201412071201

Alahmadi N, Muslim Alraddadi B. The impact of virtual classes on second language interaction in the Saudi EFL context: a case study of Saudi undergraduate students. Arab World Engl J (AWEJ) Volume. 2020;11. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3705065

Tanis CJ. The seven principles of online learning: feedback from faculty and alumni on its importance for teaching and learning. Res Learn Technol. 2020;28.

Alenezi A. The role of e-learning materials in enhancing teaching and learning behaviors. Int J Inform Educ Technol. 2020;10(1):48–56.

Adnan M, Anwar K. Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: students’ perspectives. Online Submiss. 2020;2(1):45–51.

Bonde MT, Makransky G, Wandall J, Larsen MV, Morsing M, Jarmer H, et al. Improving biotech education through gamified laboratory simulations. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(7):694–7.

Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, Smith MK, Okoroafor N, Jordt H et al. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 2014;111(23):8410-5.

Evans S, Perry E. An exploration of perceptions of online asynchronous and synchronous interprofessional education facilitation strategies. J Interprof Care. 2023;37(6):1010–7.

Albarrak A. E-Learning in medical education and blended Learning approach. Learning. 2011;13:14–20.

Bjekic D, Krneta R, Milosevic D. Teacher education from e-learner to e-teacher: Master curriculum. Turkish Online J Educational Technology-TOJET. 2010;9(1):202–12.

Maatuk AM, Elberkawi EK, Aljawarneh S, Rashaideh H, Alharbi H. The COVID-19 pandemic and E-learning: challenges and opportunities from the perspective of students and instructors. J Comput High Educ. 2022;34(1):21–38.

Ramírez-Hurtado JM, Hernández-Díaz AG, López-Sánchez AD, Pérez-León VE. Measuring online teaching service quality in higher education in the COVID-19 environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2403.

Craig R. The 3 instructional shifts that will redefine the college professor 2015 [ https://www.edsurge.com/news/2015-08-04-the-3-instructional-shifts-that-will-redefine-the-college-professor

Bianchi S, Bernardi S, Perilli E, Cipollone C, Di Biasi J, Macchiarelli G. Evaluation of effectiveness of digital technologies during anatomy learning in nursing school. Appl Sci. 2020;10(7):2357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10072357

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fedynich LV. Teaching beyond the classroom walls: the pros and cons of cyber learning. J Instructional Pedagogies. 2013;13.

Kim J. Learning and teaching online during Covid-19: experiences of student teachers in an early childhood education practicum. Int J Early Child. 2020;52(2):145–58.

Al Shorbaji N, Atun R, Car J, Majeed A, Wheeler EL, Beck D, et al. eLearning for undergraduate health professional education: a systematic review informing a radical transformation of health workforce development. World Health Organization; 2015.

Schlenz MA, Schmidt A, Wöstmann B, Krämer N, Schulz-Weidner N. Students’ and lecturers’ perspective on the implementation of online learning in dental education due to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–7.

Mottaghi A, Alibeik N, Savaj S, Shakiba B, Alimoradzadeh R, Almasi S et al. Comparison of Virtual and Actual Education Models on the Learning of Internal Interns During the Pandemic of COVID-19. 2021.

Sahi PK, Mishra D, Singh T. Medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57:652–7.

Atreya A, Acharya J. Distant virtual medical education during COVID-19: Half a loaf of bread. The clinical teacher. 2020.

Da Silva BM. Will virtual teaching continue after the COVID-19 pandemic? Acta Med Port. 2020;33(6):446.

Hodgson JC, Hagan P. Medical education adaptations during a pandemic: transitioning to virtual student support. Med Educ. 2020;54(7):662–3.

Kaup S, Jain R, Shivalli S, Pandey S, Kaup S. Sustaining academics during COVID-19 pandemic: the role of online teaching-learning. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(6):1220.

Roskvist R, Eggleton K, Goodyear-Smith F. Provision of e-learning programmes to replace undergraduate medical students’ clinical general practice attachments during COVID-19 stand-down. Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(4):247–54.

Sleiwah A, Mughal M, Hachach-Haram N, Roblin P. COVID-19 lockdown learning: the uprising of virtual teaching. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2020;73(8):1575–92.

Machado RA, Bonan PRF, Perez DEC, Martelli DRB, Martelli-Júnior H. I am having trouble keeping up with virtual teaching activities: reflections in the COVID-19 era. Clinics. 2020;75:e1945.

Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, Biewald MA, Farouk SS. Medical education during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: learning from a distance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(5):412–7.

Lara S, Foster CW, Hawks M, Montgomery M. Remote assessment of clinical skills during COVID-19: a virtual, high-stakes, summative pediatric objective structured clinical examination. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(6):760–1.

Su B, Zhang T, Yan L, Huang C, Cheng X, Cai C, et al. Online medical teaching in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: tools, modalities, and challenges. Front Public Health. 2021;9:797694.

Bianchi S, Gatto R, Fabiani L. Effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on medical education in Italy: considerations and tips. Appl Sci. 2020;10(7):2357. https://doi.org/10.3269/1970-5492.2020.15.24

Kalejta RF. Virology Laboratory guidelines. J Virol. 2021;95(18):e0111221. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01112-21

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the officials of the universities of medical sciences as well as all the experts and experts who have helped us with their valuable views.

There was no Funding support in this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hospital Administration Research Center, Sari Branch, Islamic Azad University, Sari, Iran

Aram Ghanavatizadeh & Ghahraman Mahmoudi

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

Mohammad-Ali Jahani & Hossein-Ali Nikbakht

Doctorate of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Seyedeh Niko Hashemi

Department of Health Economics and Management, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Mahdi Abbasi

Babol Education Department, Babol, Iran

Alameh Darzi

Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

Seyed-Amir Soltani

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Aram Ghanavatizadeh writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Ghahraman Mahmoudi: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology. Mohammad-Ali Jahani: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; software; super-vision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Hossein-Ali Nikbakht: Conceptualization; writing—original draft. Seyedeh Niko Hashemi: Formal analysis; investigation. Mahdi Abbas: data curation; Writing—original draft. Alameh Darzi writing—review and editing. Seyed Amir Soltani: writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohammad-Ali Jahani .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was done after holding the ethical code of IR.IAU.SARI.REC.1401.061 from Islamic Azad University. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. freedom of participants to participate in the study, obtaining informed consent and maintaining confidentiality of information at all stages were respected.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ghanavatizadeh, A., Mahmoudi, G., Jahani, MA. et al. Determining the challenges and opportunities of virtual teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed method study in the north of Iran. BMC Res Notes 17 , 148 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-024-06806-8

Download citation

Received : 11 April 2024

Accepted : 20 May 2024

Published : 27 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-024-06806-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Virtual education

- Active learning

- COVID-19 pandemic

BMC Research Notes

ISSN: 1756-0500

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Effect of COVID-19 on Education

Jacob hoofman.

a Wayne State University School of Medicine, 540 East Canfield, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

Elizabeth Secord

b Department of Pediatrics, Wayne Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Pediatrics Wayne State University, 400 Mack Avenue, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

COVID-19 has changed education for learners of all ages. Preliminary data project educational losses at many levels and verify the increased anxiety and depression associated with the changes, but there are not yet data on long-term outcomes. Guidance from oversight organizations regarding the safety and efficacy of new delivery modalities for education have been quickly forged. It is no surprise that the socioeconomic gaps and gaps for special learners have widened. The medical profession and other professions that teach by incrementally graduated internships are also severely affected and have had to make drastic changes.

- • Virtual learning has become a norm during COVID-19.

- • Children requiring special learning services, those living in poverty, and those speaking English as a second language have lost more from the pandemic educational changes.

- • For children with attention deficit disorder and no comorbidities, virtual learning has sometimes been advantageous.

- • Math learning scores are more likely to be affected than language arts scores by pandemic changes.

- • School meals, access to friends, and organized activities have also been lost with the closing of in-person school.