Qualitative Study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervene or introduce treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypotheses as well as further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and application of qualitative research.

Qualitative research at its core, ask open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers such as ‘how’ and ‘why’. Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions at hand, qualitative research design is often not linear in the same way quantitative design is. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be difficult to accurately capture quantitatively, whereas a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a certain time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify and it is important to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore ‘compete’ against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each, qualitative and quantitative work are not necessarily opposites nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites, and they are certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined that there is a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated together.

Examples of Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography

Ethnography as a research design has its origins in social and cultural anthropology, and involves the researcher being directly immersed in the participant’s environment. Through this immersion, the ethnographer can use a variety of data collection techniques with the aim of being able to produce a comprehensive account of the social phenomena that occurred during the research period. That is to say, the researcher’s aim with ethnography is to immerse themselves into the research population and come out of it with accounts of actions, behaviors, events, etc. through the eyes of someone involved in the population. Direct involvement of the researcher with the target population is one benefit of ethnographic research because it can then be possible to find data that is otherwise very difficult to extract and record.

Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is the “generation of a theoretical model through the experience of observing a study population and developing a comparative analysis of their speech and behavior.” As opposed to quantitative research which is deductive and tests or verifies an existing theory, grounded theory research is inductive and therefore lends itself to research that is aiming to study social interactions or experiences. In essence, Grounded Theory’s goal is to explain for example how and why an event occurs or how and why people might behave a certain way. Through observing the population, a researcher using the Grounded Theory approach can then develop a theory to explain the phenomena of interest.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is defined as the “study of the meaning of phenomena or the study of the particular”. At first glance, it might seem that Grounded Theory and Phenomenology are quite similar, but upon careful examination, the differences can be seen. At its core, phenomenology looks to investigate experiences from the perspective of the individual. Phenomenology is essentially looking into the ‘lived experiences’ of the participants and aims to examine how and why participants behaved a certain way, from their perspective . Herein lies one of the main differences between Grounded Theory and Phenomenology. Grounded Theory aims to develop a theory for social phenomena through an examination of various data sources whereas Phenomenology focuses on describing and explaining an event or phenomena from the perspective of those who have experienced it.

Narrative Research

One of qualitative research’s strengths lies in its ability to tell a story, often from the perspective of those directly involved in it. Reporting on qualitative research involves including details and descriptions of the setting involved and quotes from participants. This detail is called ‘thick’ or ‘rich’ description and is a strength of qualitative research. Narrative research is rife with the possibilities of ‘thick’ description as this approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals, in the hopes of creating a cohesive story, or narrative. While it might seem like a waste of time to focus on such a specific, individual level, understanding one or two people’s narratives for an event or phenomenon can help to inform researchers about the influences that helped shape that narrative. The tension or conflict of differing narratives can be “opportunities for innovation”.

Research Paradigm

Research paradigms are the assumptions, norms, and standards that underpin different approaches to research. Essentially, research paradigms are the ‘worldview’ that inform research. It is valuable for researchers, both qualitative and quantitative, to understand what paradigm they are working within because understanding the theoretical basis of research paradigms allows researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approach being used and adjust accordingly. Different paradigms have different ontology and epistemologies . Ontology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of reality” whereas epistemology is defined as the “assumptions about the nature of knowledge” that inform the work researchers do. It is important to understand the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research paradigm researchers are working within to allow for a full understanding of the approach being used and the assumptions that underpin the approach as a whole. Further, it is crucial that researchers understand their own ontological and epistemological assumptions about the world in general because their assumptions about the world will necessarily impact how they interact with research. A discussion of the research paradigm is not complete without describing positivist, postpositivist, and constructivist philosophies.

Positivist vs Postpositivist

To further understand qualitative research, we need to discuss positivist and postpositivist frameworks. Positivism is a philosophy that the scientific method can and should be applied to social as well as natural sciences. Essentially, positivist thinking insists that the social sciences should use natural science methods in its research which stems from positivist ontology that there is an objective reality that exists that is fully independent of our perception of the world as individuals. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist philosophy, which can be seen in the value it places on concepts such as causality, generalizability, and replicability.

Conversely, postpositivists argue that social reality can never be one hundred percent explained but it could be approximated. Indeed, qualitative researchers have been insisting that there are “fundamental limits to the extent to which the methods and procedures of the natural sciences could be applied to the social world” and therefore postpositivist philosophy is often associated with qualitative research. An example of positivist versus postpositivist values in research might be that positivist philosophies value hypothesis-testing, whereas postpositivist philosophies value the ability to formulate a substantive theory.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a subcategory of postpositivism. Most researchers invested in postpositivist research are constructivist as well, meaning they think there is no objective external reality that exists but rather that reality is constructed. Constructivism is a theoretical lens that emphasizes the dynamic nature of our world. “Constructivism contends that individuals’ views are directly influenced by their experiences, and it is these individual experiences and views that shape their perspective of reality”. Essentially, Constructivist thought focuses on how ‘reality’ is not a fixed certainty and experiences, interactions, and backgrounds give people a unique view of the world. Constructivism contends, unlike in positivist views, that there is not necessarily an ‘objective’ reality we all experience. This is the ‘relativist’ ontological view that reality and the world we live in are dynamic and socially constructed. Therefore, qualitative scientific knowledge can be inductive as well as deductive.”

So why is it important to understand the differences in assumptions that different philosophies and approaches to research have? Fundamentally, the assumptions underpinning the research tools a researcher selects provide an overall base for the assumptions the rest of the research will have and can even change the role of the researcher themselves. For example, is the researcher an ‘objective’ observer such as in positivist quantitative work? Or is the researcher an active participant in the research itself, as in postpositivist qualitative work? Understanding the philosophical base of the research undertaken allows researchers to fully understand the implications of their work and their role within the research, as well as reflect on their own positionality and bias as it pertains to the research they are conducting.

Data Sampling

The better the sample represents the intended study population, the more likely the researcher is to encompass the varying factors at play. The following are examples of participant sampling and selection:

Purposive sampling- selection based on the researcher’s rationale in terms of being the most informative.

Criterion sampling-selection based on pre-identified factors.

Convenience sampling- selection based on availability.

Snowball sampling- the selection is by referral from other participants or people who know potential participants.

Extreme case sampling- targeted selection of rare cases.

Typical case sampling-selection based on regular or average participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

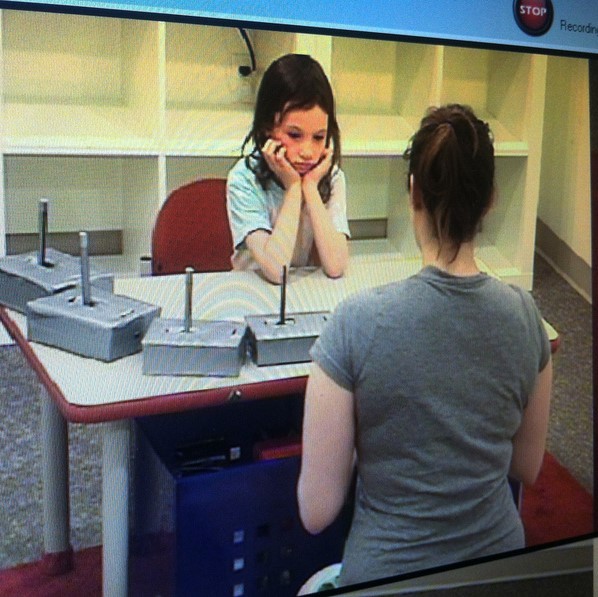

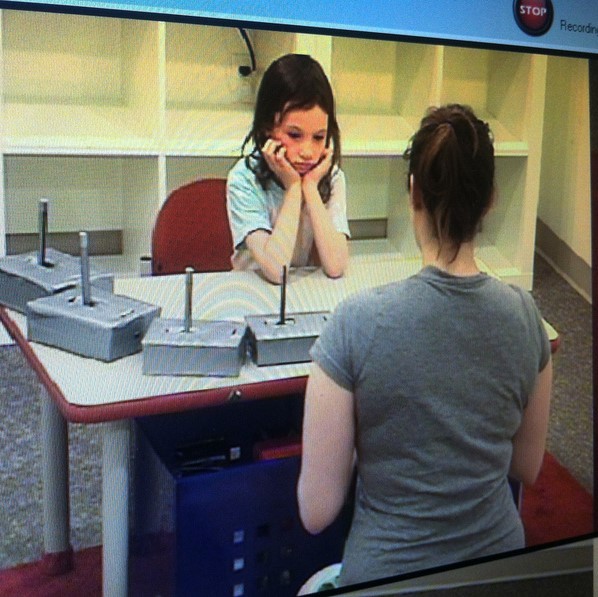

Qualitative research uses several techniques including interviews, focus groups, and observation. [1] [2] [3] Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one on one and is appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be a participant-observer to share the experiences of the subject or a non-participant or detached observer.

While quantitative research design prescribes a controlled environment for data collection, qualitative data collection may be in a central location or in the environment of the participants, depending on the study goals and design. Qualitative research could amount to a large amount of data. Data is transcribed which may then be coded manually or with the use of Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software or CAQDAS such as ATLAS.ti or NVivo.

After the coding process, qualitative research results could be in various formats. It could be a synthesis and interpretation presented with excerpts from the data. Results also could be in the form of themes and theory or model development.

Dissemination

To standardize and facilitate the dissemination of qualitative research outcomes, the healthcare team can use two reporting standards. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ is a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is a checklist covering a wider range of qualitative research.

Examples of Application

Many times a research question will start with qualitative research. The qualitative research will help generate the research hypothesis which can be tested with quantitative methods. After the data is collected and analyzed with quantitative methods, a set of qualitative methods can be used to dive deeper into the data for a better understanding of what the numbers truly mean and their implications. The qualitative methods can then help clarify the quantitative data and also help refine the hypothesis for future research. Furthermore, with qualitative research researchers can explore subjects that are poorly studied with quantitative methods. These include opinions, individual's actions, and social science research.

A good qualitative study design starts with a goal or objective. This should be clearly defined or stated. The target population needs to be specified. A method for obtaining information from the study population must be carefully detailed to ensure there are no omissions of part of the target population. A proper collection method should be selected which will help obtain the desired information without overly limiting the collected data because many times, the information sought is not well compartmentalized or obtained. Finally, the design should ensure adequate methods for analyzing the data. An example may help better clarify some of the various aspects of qualitative research.

A researcher wants to decrease the number of teenagers who smoke in their community. The researcher could begin by asking current teen smokers why they started smoking through structured or unstructured interviews (qualitative research). The researcher can also get together a group of current teenage smokers and conduct a focus group to help brainstorm factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke (qualitative research).

In this example, the researcher has used qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) to generate a list of ideas of both why teens start to smoke as well as factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke. Next, the researcher compiles this data. The research found that, hypothetically, peer pressure, health issues, cost, being considered “cool,” and rebellious behavior all might increase or decrease the likelihood of teens starting to smoke.

The researcher creates a survey asking teen participants to rank how important each of the above factors is in either starting smoking (for current smokers) or not smoking (for current non-smokers). This survey provides specific numbers (ranked importance of each factor) and is thus a quantitative research tool.

The researcher can use the results of the survey to focus efforts on the one or two highest-ranked factors. Let us say the researcher found that health was the major factor that keeps teens from starting to smoke, and peer pressure was the major factor that contributed to teens to start smoking. The researcher can go back to qualitative research methods to dive deeper into each of these for more information. The researcher wants to focus on how to keep teens from starting to smoke, so they focus on the peer pressure aspect.

The researcher can conduct interviews and/or focus groups (qualitative research) about what types and forms of peer pressure are commonly encountered, where the peer pressure comes from, and where smoking first starts. The researcher hypothetically finds that peer pressure often occurs after school at the local teen hangouts, mostly the local park. The researcher also hypothetically finds that peer pressure comes from older, current smokers who provide the cigarettes.

The researcher could further explore this observation made at the local teen hangouts (qualitative research) and take notes regarding who is smoking, who is not, and what observable factors are at play for peer pressure of smoking. The researcher finds a local park where many local teenagers hang out and see that a shady, overgrown area of the park is where the smokers tend to hang out. The researcher notes the smoking teenagers buy their cigarettes from a local convenience store adjacent to the park where the clerk does not check identification before selling cigarettes. These observations fall under qualitative research.

If the researcher returns to the park and counts how many individuals smoke in each region of the park, this numerical data would be quantitative research. Based on the researcher's efforts thus far, they conclude that local teen smoking and teenagers who start to smoke may decrease if there are fewer overgrown areas of the park and the local convenience store does not sell cigarettes to underage individuals.

The researcher could try to have the parks department reassess the shady areas to make them less conducive to the smokers or identify how to limit the sales of cigarettes to underage individuals by the convenience store. The researcher would then cycle back to qualitative methods of asking at-risk population their perceptions of the changes, what factors are still at play, as well as quantitative research that includes teen smoking rates in the community, the incidence of new teen smokers, among others.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

Why Schools Need to Change Learning for Success in the Real World

Amanda Avallone (she/her/hers) Learning Officer (ret.) Next Generation Learning Challenges in Portland, Maine

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Preparing young people for life-long success through real-world learning

All students need to leave school—frequently, regularly, and of course, temporarily… To accomplish this, schools must take down the walls that separate the learning that students do, and could do, in school from the learning they do and could do, outside. —Elliot Washor and Charles Mojkowski, Big Picture Learning

In 2017 NGLC published the MyWays Student Success Series , a collection of reports, resources, and tools to support educators and communities to reimagine traditional definitions of learner success and redesign learning to help all students prepare for their futures. Inspired by the practices and valuable feedback from schools and districts in the NGLC network, the MyWays project has continued to evolve and expand to meet the needs of practitioners and their communities.

One area of particular interest for educators who are adopting broader definitions of success, like the MyWays Student Success Framework , is providing all students with authentic, real-world learning opportunities. Grace Belfiore, one of the principal researchers and authors of the MyWays report series, observes that, “One of the most striking implications of the MyWays’ research was the realization that it is difficult, if not impossible, to help learners develop these competencies and skills without going outside the classroom walls.” She also notes that, although some educators in the NGLC community have made real-world learning the cornerstone of their model, many others who have embraced next gen learning are newcomers to accessing the world outside of school as a rich source of student learning.

School lasts for 12 years, but students’ lives last a lot longer. What are we doing to develop people ?

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning , I spoke to a variety of experts who are partnering with their communities to provide relevant and authentic student learning. This edition will also introduce practitioners to a new NGLC resource for this work, the MyWays Real-World Learning Toolkit . In particular, I’ll share:

- Why real-world learning is essential for student success

- Expert advice and resources to incorporate real-world learning in your classroom or school

Skills and Abilities for Lifelong Success

Early access to real-world projects is a springboard to seeing what success looks like outside of the classroom. —Natasha Morrison, director of real world learning at Da Vinci Schools.

The MyWays Student Success Framework and other 21st-century definitions of success share a fundamental understanding that the world has changed and continues to change at an accelerating rate. In addition to Content Knowledge, learners also need competencies within the MyWays domains of Habits of Success, Creative Know How, and Wayfinding Abilities to navigate through learning, career, and life. Young people need to experience learning that does more than prepare them to take a test or pass into the next grade.

Lindsey Stutheit, workforce partnership liaison at Laramie County School District #1 in Cheyenne, WY, expresses it this way: “For a long time, college- and career-readiness has really meant college, and that, in my experience, has meant preparing for the ACT or other state-mandated standardized tests. We spend a lot of resources and time preparing students for these tests, something fleeting and momentary. These tests are valid measures, but they aren’t geared around careers, personal skills, or adult skills. ” Lindsey and other leaders in her district recognize that young people need to develop capabilities that are life-long, life-wide, and life-worthy. “School lasts for 12 years,” she notes, “but students’ lives last a lot longer. What are we doing to develop people ?”

Casey Lamb, chief operating officer at Schools That Can , a network of schools that have embraced real-world learning, also argues for a more holistic notion of education and preparation. Real-world learning is, she says, “not just about the partnerships but about the outcomes, which move beyond what is usually tested in schools. It’s about developing whole humans.”

However, expecting schools to do this work alone, our experts tell us, is neither reasonable nor possible. According to Casey, one reason young people need access to learning experiences outside of school is that “the majority of teachers went to school to be teachers. They should not be expected to know everything about all of the myriad fields in order to prepare students for every career and opportunity. Real-world learning connects both students and teachers to people in the community who are working in different environments and have different perspectives, as well as to the skills adults use on a daily basis. ”

In this way, Casey explains, real-world experiences “ground students’ learning in the paths they will pursue after graduation. It better prepares them for those pathways, offers them choices, and gives them the ability to be successful there.”

Equitable Access to the World of Adults

Offering opportunities for young people to connect with the world outside of school is not new. Common activities like field trips, science fairs, model UN, theater productions, and extracurricular clubs can provide learners with access to adults in the community. Yet, as Lindsey observes, supporting young people to work side by side with adult professionals “is often teacher dependent and based on the connections individual teachers have. You also see the same students participating over and over.”

According to Lindsey, schools need to ensure that all students have access to support for wayfinding through education, work, and life, including meaningful connections to a wide range of adults from different industries and careers . This kind of social capital “is an equity issue for us and one reason it’s facilitated at the district level—to improve student exposure and reach.”

As described in MyWays Report 4: 5 Essentials in Building Social Capital , social capital is a developmental system of human relationships, including caring adults, mentors and coaches, and professional networks. According to the MyWays research, social capital plays two important roles in the life of young people: “as support in times of need and as social leverage to get ahead.” Significant disparities exist, however, between students of varying socioeconomic backgrounds in the opportunities to build social capital. Because both social capital roles are manifested in well-designed real-world learning, the MyWays Real-World Learning Toolkit includes a Social Capital Tool , which supports educators to design learning for social capital benefits for learners across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Real-World Contexts for “Whitewater Learning”

Real-world learning shares characteristics and benefits with other types of authentic, active learning. For example, both school-based and real-world projects can help learners develop Habits of Success , from initiative and perseverance to time management. However, real-world learning also provides the unique benefits, motivations, and opportunities of tackling real problems in the environments in which they occur, in all their messiness and urgency . As explored in the MyWays Key Elements of Real-World Learning Tool , well-designed outside-of-school experiences give learners the opportunity to encounter and respond to “whitewater conditions”—diverse challenges, complexities, and unfamiliar circumstances like those they will encounter as adults.

Skills like project management, collaboration, and problem-solving must be learned in a hands-on, high-stakes way.

Natasha explains that classroom experiences that simulate real-world learning are not enough, especially when it comes to preparing young people for future careers. “You can’t simulate social interaction. It’s not the same as an airline pilot using a flight simulator. There’s no substitute for engagement with the professional world. Attempting to develop career skills with virtually no real-world practice or feedback doesn’t achieve ideal outcomes . Partnership with industry professionals on real-world projects allows students to hone the skills they’ll actually use in the modern workforce. Skills like project management, collaboration, and problem-solving must be learned in a hands-on, high-stakes way.”

In addition to teaching a fuller range of competencies and facilitating connections to a wide array of adults, meaningful real-world learning provides learners with opportunities to make choices and practice self-direction. According to Grace, “ Experience in real and diverse situations is key to agency, and to help achieve growth, educators and youth advocates need to help students access and utilize a range of real-world situations .” Real-world learning can also foster identity development, she says, offering young people a vision of what’s possible for their futures.

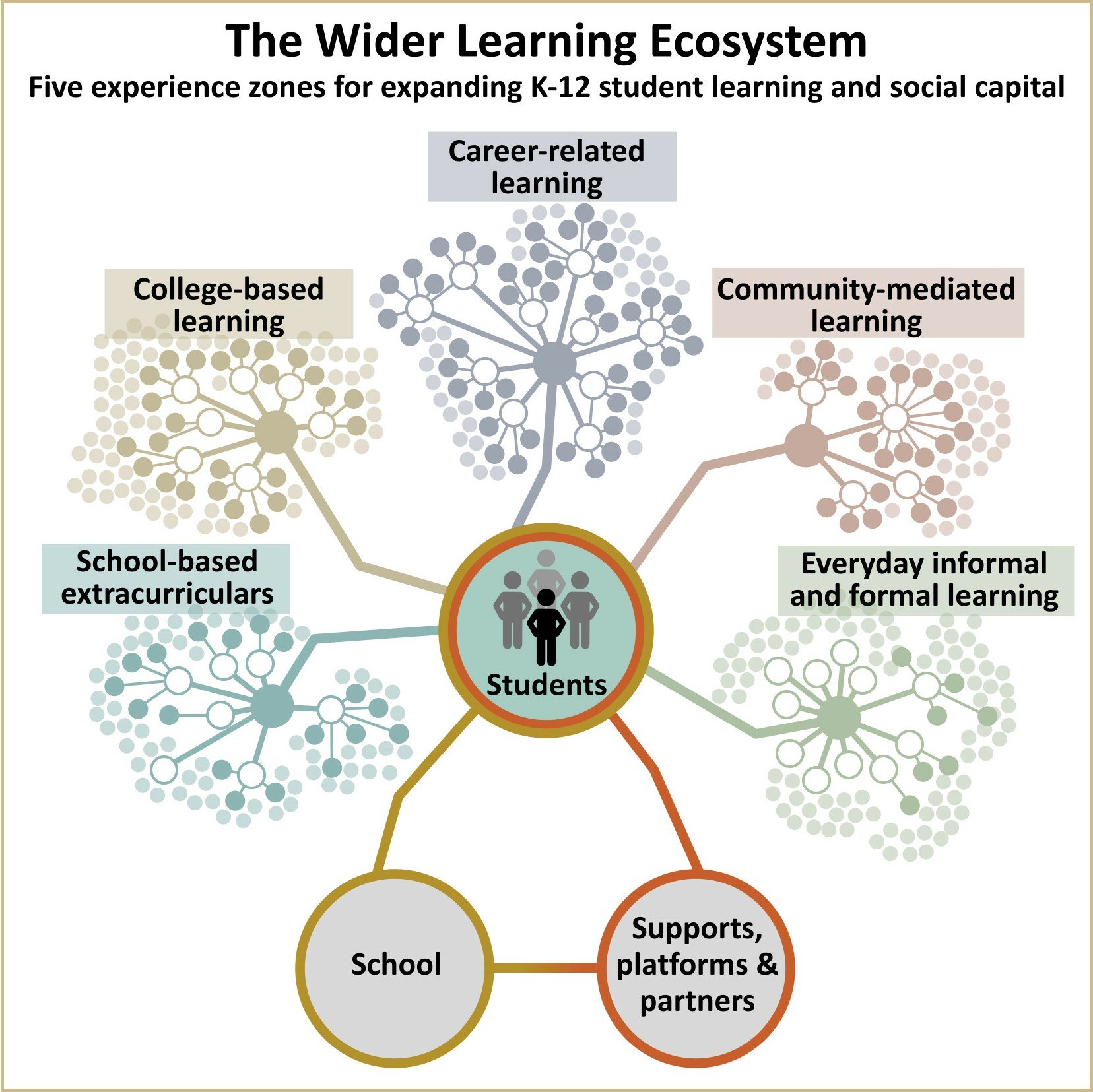

Connections to the Wider Learning Ecosystem

Redesigning learning to be more like an apprenticeship for adult life can seem overwhelming. In part, that’s because educators have traditionally shouldered so much of this responsibility. However, schools and educators have numerous assets and partners for this work . Accessing the Wider Learning Ecosystem means leveraging the vast network of resources and experiences, formal and informal, that exist outside of school, including higher education, the workplace, and community assets like museums and libraries, as well as school-based extracurricular activities. Tapping into these assets is the focus of the MyWays 5 Zones of the Wider Learning Ecosystem Tool .

The 5 Zones of the Wider Learning Ecosystem

As featured in a Practitioner’s Guide about community partnerships , Natasha and her colleagues at Da Vinci Schools provide high school students with numerous real-world learning experiences throughout the Wider Learning Ecosystem. Partnerships with colleges, universities, and local businesses open up opportunities for apprentice adults to participate in dual or concurrent enrollment in higher education, job-shadowing, internships, career-focused boot camps, and other industry-based experiences. Educators at both Da Vinci Schools and in Laramie County stress that these experiences need to be well designed to achieve the desired impact. According to Lindsey, “Earning college credits should not be random. Credits should lead to students’ goals for after graduation.” Similarly, workplace experiences “can’t just be a job. They have to build career awareness and help students prepare for their futures.”

Though the kinds of experiences mentioned above are most common at the secondary level, building learner skills to be successful in a real-world learning context can occur at any grade , and educators can gradually integrate real-world learning elements over time. Casey defines real-world learning this way: “In its simplest form, it’s learning that is hands on, engaging, and connected with the world beyond school walls.”

When deeply implemented, real-world learning looks more like this: “All students access multiple opportunities and teachers are actively involved. Teachers have built relationships with the community and moved beyond offering a one-off project,” Casey explains. For instance, at the “leading level” of the Schools That Can Real-World Learning Rubric , “Real-world experiences are ongoing throughout the course of the year. Real-world learning is part of the fabric of the school and everyone benefits.”

For schools and educators new to real-world learning, Casey offers several ways to get started, such as by designing learning projects and experiences that are hands on and involve learning by doing . Maker education is one example. She also recommends inquiry-based approaches like Self-Organized Learning Environments (SOLE), in which educators present learners with real-world problems and frame projects “as a big question to research and explore and build solutions to. Ideally, learning should be interdisciplinary as well because that’s the way the real world works.”

As a natural next step for engaging with the world outside of school, Casey suggests “having students present to authentic audiences outside of school or bringing experts or professionals into the school. They can be judges on work and help kids get a different kind of feedback. It’s an easy way to start those partnerships and build a mutually beneficial relationship.”

The MyWays Readiness and Preparation Tool acknowledges that many of the attributes of real-world learning are very different from the kind of teaching and learning that happens in more traditional schools. In addition to building educator capacity for designing authentic, hands-on, and student-driven learning, this tool recognizes that students themselves and members of the community will likely need assistance as they shift their mindsets and think about learning in new ways . Lindsey’s experiences bear this reality out. She recounts, for example, “When I tell a local business leader that simply coming in and talking about your business might be hard for a teacher to justify without an educational goal in mind, it can be really eye-opening. People from industry and the community may know little about education, but it’s not insurmountable.”

For that reason, the Readiness and Preparation Tool helps schools gauge the readiness of educators, learners, and external partners from the Wider Learning Ecosystem. It also provides suggestions and resources to prepare all three partners to co-create powerful and successful real-world learning experiences.

- The MyWays Real-World Learning Toolkit provides educators and their community partners with four tools to support the design of powerful and successful real-world learning experiences.

- The Schools That Can Real-World Learning Rubric (free to download with registration) serves as a guide to help K-12 schools reflect, set goals, and drive improvements around RWL.

- Part one and part two of the Practitioner’s Guide series "It Takes a Village" shares practices and resources from three school systems deeply engaged in real-world learning: Da Vinci Schools (CA), St. Vrain Valley Schools (CO), and Vista Unified School District (CA).

- “ Who You Know: Building Students’ Social Capital ” explores in greater depth why social capital is an essential part of young people’s preparation for life and how schools and educators can support students in acquiring it.

- MyWays Report 11: Learning Design for Broader, Deeper Competencies presents research, design principles, and case studies on key practices, like real-world learning, that support student development of agency, social capital, and competencies for success.

Photo at top, courtesy of NGLC: Students at Vista High School engage in real-world learning.

Amanda Avallone (she/her/hers)

Learning officer (ret.), next generation learning challenges.

Amanda retired from Next Generation Learning Challenges in 2022. As a Learning Officer for NGLC, she collaborated with pioneering educators and their communities to design authentic, powerful learning experiences for young people. She created educator professional learning experiences that exemplify the kind of learning we want for our students and she supported, connected, and celebrated, through storytelling, the educators who are already doing the challenging work of transforming learning every day.

Read More About Why Schools Need to Change

Bring Your Vision for Student Success to Life with NGLC and Bravely

March 13, 2024

For Ethical AI, Listen to Teachers

Jason Wilmot

October 23, 2023

Turning School Libraries into Discipline Centers Is Not the Answer to Disruptive Classroom Behavior

Stephanie McGary

October 4, 2023

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.5: Conducting Psychology Research in the Real World

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10603

- Matthias R. Mehl

- https://nobaproject.com/ via The Noba Project

University of Arizona

Because of its ability to determine cause-and-effect relationships, the laboratory experiment is traditionally considered the method of choice for psychological science. One downside, however, is that as it carefully controls conditions and their effects, it can yield findings that are out of touch with reality and have limited use when trying to understand real-world behavior. This module highlights the importance of also conducting research outside the psychology laboratory, within participants’ natural, everyday environments, and reviews existing methodologies for studying daily life.

learning objectives

- Identify limitations of the traditional laboratory experiment.

- Explain ways in which daily life research can further psychological science.

- Know what methods exist for conducting psychological research in the real world.

Introduction

The laboratory experiment is traditionally considered the “gold standard” in psychology research. This is because only laboratory experiments can clearly separate cause from effect and therefore establish causality. Despite this unique strength, it is also clear that a scientific field that is mainly based on controlled laboratory studies ends up lopsided. Specifically, it accumulates a lot of knowledge on what can happen—under carefully isolated and controlled circumstances—but it has little to say about what actually does happen under the circumstances that people actually encounter in their daily lives.

For example, imagine you are a participant in an experiment that looks at the effect of being in a good mood on generosity, a topic that may have a good deal of practical application. Researchers create an internally-valid, carefully-controlled experiment where they randomly assign you to watch either a happy movie or a neutral movie, and then you are given the opportunity to help the researcher out by staying longer and participating in another study. If people in a good mood are more willing to stay and help out, the researchers can feel confident that – since everything else was held constant – your positive mood led you to be more helpful. However, what does this tell us about helping behaviors in the real world? Does it generalize to other kinds of helping, such as donating money to a charitable cause? Would all kinds of happy movies produce this behavior, or only this one? What about other positive experiences that might boost mood, like receiving a compliment or a good grade? And what if you were watching the movie with friends, in a crowded theatre, rather than in a sterile research lab? Taking research out into the real world can help answer some of these sorts of important questions.

As one of the founding fathers of social psychology remarked, “Experimentation in the laboratory occurs, socially speaking, on an island quite isolated from the life of society” (Lewin, 1944, p. 286). This module highlights the importance of going beyond experimentation and also conducting research outside the laboratory (Reis & Gosling, 2010), directly within participants’ natural environments, and reviews existing methodologies for studying daily life.

Rationale for Conducting Psychology Research in the Real World

One important challenge researchers face when designing a study is to find the right balance between ensuring internal validity , or the degree to which a study allows unambiguous causal inferences, and external validity , or the degree to which a study ensures that potential findings apply to settings and samples other than the ones being studied (Brewer, 2000). Unfortunately, these two kinds of validity tend to be difficult to achieve at the same time, in one study. This is because creating a controlled setting, in which all potentially influential factors (other than the experimentally-manipulated variable) are controlled, is bound to create an environment that is quite different from what people naturally encounter (e.g., using a happy movie clip to promote helpful behavior). However, it is the degree to which an experimental situation is comparable to the corresponding real-world situation of interest that determines how generalizable potential findings will be. In other words, if an experiment is very far-off from what a person might normally experience in everyday life, you might reasonably question just how useful its findings are.

Because of the incompatibility of the two types of validity, one is often—by design—prioritized over the other. Due to the importance of identifying true causal relationships, psychology has traditionally emphasized internal over external validity. However, in order to make claims about human behavior that apply across populations and environments, researchers complement traditional laboratory research, where participants are brought into the lab, with field research where, in essence, the psychological laboratory is brought to participants. Field studies allow for the important test of how psychological variables and processes of interest “behave” under real-world circumstances (i.e., what actually does happen rather than what can happen ). They can also facilitate “downstream” operationalizations of constructs that measure life outcomes of interest directly rather than indirectly.

Take, for example, the fascinating field of psychoneuroimmunology, where the goal is to understand the interplay of psychological factors - such as personality traits or one’s stress level - and the immune system. Highly sophisticated and carefully controlled experiments offer ways to isolate the variety of neural, hormonal, and cellular mechanisms that link psychological variables such as chronic stress to biological outcomes such as immunosuppression (a state of impaired immune functioning; Sapolsky, 2004). Although these studies demonstrate impressively how psychological factors can affect health-relevant biological processes, they—because of their research design—remain mute about the degree to which these factors actually do undermine people’s everyday health in real life. It is certainly important to show that laboratory stress can alter the number of natural killer cells in the blood. But it is equally important to test to what extent the levels of stress that people experience on a day-to-day basis result in them catching a cold more often or taking longer to recover from one. The goal for researchers, therefore, must be to complement traditional laboratory experiments with less controlled studies under real-world circumstances. The term ecological validity is used to refer the degree to which an effect has been obtained under conditions that are typical for what happens in everyday life (Brewer, 2000). In this example, then, people might keep a careful daily log of how much stress they are under as well as noting physical symptoms such as headaches or nausea. Although many factors beyond stress level may be responsible for these symptoms, this more correlational approach can shed light on how the relationship between stress and health plays out outside of the laboratory.

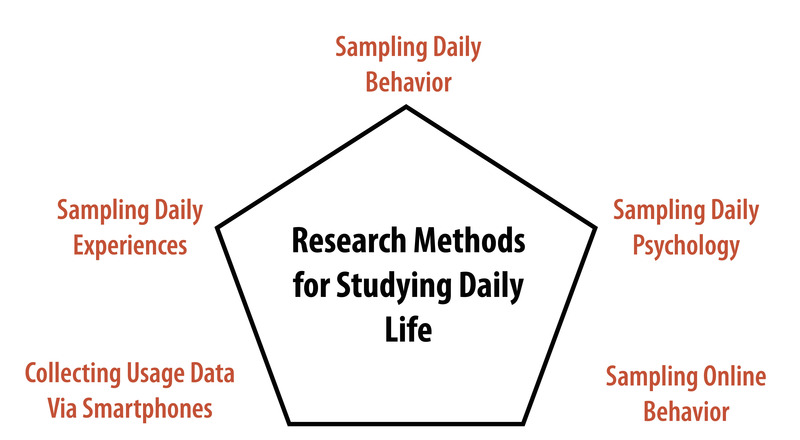

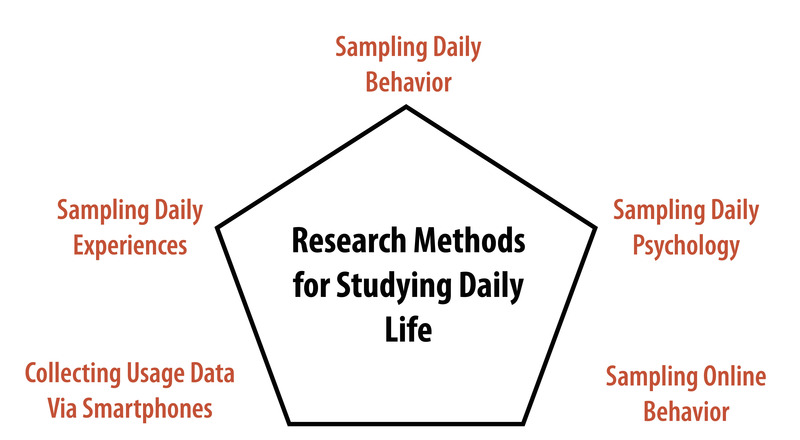

An Overview of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life

Capturing “life as it is lived” has been a strong goal for some researchers for a long time. Wilhelm and his colleagues recently published a comprehensive review of early attempts to systematically document daily life (Wilhelm, Perrez, & Pawlik, 2012). Building onto these original methods, researchers have, over the past decades, developed a broad toolbox for measuring experiences, behavior, and physiology directly in participants’ daily lives (Mehl & Conner, 2012). Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the methodologies described below.

Studying Daily Experiences

Starting in the mid-1970s, motivated by a growing skepticism toward highly-controlled laboratory studies, a few groups of researchers developed a set of new methods that are now commonly known as the experience-sampling method (Hektner, Schmidt, & Csikszentmihalyi, 2007), ecological momentary assessment (Stone & Shiffman, 1994), or the diary method (Bolger & Rafaeli, 2003). Although variations within this set of methods exist, the basic idea behind all of them is to collect in-the-moment (or, close-to-the-moment) self-report data directly from people as they go about their daily lives. This is typically accomplished by asking participants’ repeatedly (e.g., five times per day) over a period of time (e.g., a week) to report on their current thoughts and feelings. The momentary questionnaires often ask about their location (e.g., “Where are you now?”), social environment (e.g., “With whom are you now?”), activity (e.g., “What are you currently doing?”), and experiences (e.g., “How are you feeling?”). That way, researchers get a snapshot of what was going on in participants’ lives at the time at which they were asked to report.

Technology has made this sort of research possible, and recent technological advances have altered the different tools researchers are able to easily use. Initially, participants wore electronic wristwatches that beeped at preprogrammed but seemingly random times, at which they completed one of a stack of provided paper questionnaires. With the mobile computing revolution, both the prompting and the questionnaire completion were gradually replaced by handheld devices such as smartphones. Being able to collect the momentary questionnaires digitally and time-stamped (i.e., having a record of exactly when participants responded) had major methodological and practical advantages and contributed to experience sampling going mainstream (Conner, Tennen, Fleeson, & Barrett, 2009).

Over time, experience sampling and related momentary self-report methods have become very popular, and, by now, they are effectively the gold standard for studying daily life. They have helped make progress in almost all areas of psychology (Mehl & Conner, 2012). These methods ensure receiving many measurements from many participants, and has further inspired the development of novel statistical methods (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). Finally, and maybe most importantly, they accomplished what they sought out to accomplish: to bring attention to what psychology ultimately wants and needs to know about, namely “what people actually do, think, and feel in the various contexts of their lives” (Funder, 2001, p. 213). In short, these approaches have allowed researchers to do research that is more externally valid, or more generalizable to real life, than the traditional laboratory experiment.

To illustrate these techniques, consider a classic study, Stone, Reed, and Neale (1987), who tracked positive and negative experiences surrounding a respiratory infection using daily experience sampling. They found that undesirable experiences peaked and desirable ones dipped about four to five days prior to participants coming down with the cold. More recently, Killingsworth and Gilbert (2010) collected momentary self-reports from more than 2,000 participants via a smartphone app. They found that participants were less happy when their mind was in an idling, mind-wandering state, such as surfing the Internet or multitasking at work, than when it was in an engaged, task-focused one, such as working diligently on a paper. These are just two examples that illustrate how experience-sampling studies have yielded findings that could not be obtained with traditional laboratory methods.

Recently, the day reconstruction method (DRM) (Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, & Stone, 2004) has been developed to obtain information about a person’s daily experiences without going through the burden of collecting momentary experience-sampling data. In the DRM, participants report their experiences of a given day retrospectively after engaging in a systematic, experiential reconstruction of the day on the following day. As a participant in this type of study, you might look back on yesterday, divide it up into a series of episodes such as “made breakfast,” “drove to work,” “had a meeting,” etc. You might then report who you were with in each episode and how you felt in each. This approach has shed light on what situations lead to moments of positive and negative mood throughout the course of a normal day.

Studying Daily Behavior

Experience sampling is often used to study everyday behavior (i.e., daily social interactions and activities). In the laboratory, behavior is best studied using direct behavioral observation (e.g., video recordings). In the real world, this is, of course, much more difficult. As Funder put it, it seems it would require a “detective’s report [that] would specify in exact detail everything the participant said and did, and with whom, in all of the contexts of the participant’s life” (Funder, 2007, p. 41).

As difficult as this may seem, Mehl and colleagues have developed a naturalistic observation methodology that is similar in spirit. Rather than following participants—like a detective—with a video camera (see Craik, 2000), they equip participants with a portable audio recorder that is programmed to periodically record brief snippets of ambient sounds (e.g., 30 seconds every 12 minutes). Participants carry the recorder (originally a microcassette recorder, now a smartphone app) on them as they go about their days and return it at the end of the study. The recorder provides researchers with a series of sound bites that, together, amount to an acoustic diary of participants’ days as they naturally unfold—and that constitute a representative sample of their daily activities and social encounters. Because it is somewhat similar to having the researcher’s ear at the participant’s lapel, they called their method the electronically activated recorder, or EAR (Mehl, Pennebaker, Crow, Dabbs, & Price, 2001). The ambient sound recordings can be coded for many things, including participants’ locations (e.g., at school, in a coffee shop), activities (e.g., watching TV, eating), interactions (e.g., in a group, on the phone), and emotional expressions (e.g., laughing, sighing). As unnatural or intrusive as it might seem, participants report that they quickly grow accustomed to the EAR and say they soon find themselves behaving as they normally would.

In a cross-cultural study, Ramírez-Esparza and her colleagues used the EAR method to study sociability in the United States and Mexico. Interestingly, they found that although American participants rated themselves significantly higher than Mexicans on the question, “I see myself as a person who is talkative,” they actually spent almost 10 percent less time talking than Mexicans did (Ramírez-Esparza, Mehl, Álvarez Bermúdez, & Pennebaker, 2009). In a similar way, Mehl and his colleagues used the EAR method to debunk the long-standing myth that women are considerably more talkative than men. Using data from six different studies, they showed that both sexes use on average about 16,000 words per day. The estimated sex difference of 546 words was trivial compared to the immense range of more than 46,000 words between the least and most talkative individual (695 versus 47,016 words; Mehl, Vazire, Ramírez-Esparza, Slatcher, & Pennebaker, 2007). Together, these studies demonstrate how naturalistic observation can be used to study objective aspects of daily behavior and how it can yield findings quite different from what other methods yield (Mehl, Robbins, & Deters, 2012).

A series of other methods and creative ways for assessing behavior directly and unobtrusively in the real world are described in a seminal book on real-world, subtle measures (Webb, Campbell, Schwartz, Sechrest, & Grove, 1981). For example, researchers have used time-lapse photography to study the flow of people and the use of space in urban public places (Whyte, 1980). More recently, they have observed people’s personal (e.g., dorm rooms) and professional (e.g., offices) spaces to understand how personality is expressed and detected in everyday environments (Gosling, Ko, Mannarelli, & Morris, 2002). They have even systematically collected and analyzed people’s garbage to measure what people actually consume (e.g., empty alcohol bottles or cigarette boxes) rather than what they say they consume (Rathje & Murphy, 2001). Because people often cannot and sometimes may not want to accurately report what they do, the direct—and ideally nonreactive—assessment of real-world behavior is of high importance for psychological research (Baumeister, Vohs, & Funder, 2007).

Studying Daily Physiology

In addition to studying how people think, feel, and behave in the real world, researchers are also interested in how our bodies respond to the fluctuating demands of our lives. What are the daily experiences that make our “blood boil”? How do our neurotransmitters and hormones respond to the stressors we encounter in our lives? What physiological reactions do we show to being loved—or getting ostracized? You can see how studying these powerful experiences in real life, as they actually happen, may provide more rich and informative data than one might obtain in an artificial laboratory setting that merely mimics these experiences.

Also, in pursuing these questions, it is important to keep in mind that what is stressful, engaging, or boring for one person might not be so for another. It is, in part, for this reason that researchers have found only limited correspondence between how people respond physiologically to a standardized laboratory stressor (e.g., giving a speech) and how they respond to stressful experiences in their lives. To give an example, Wilhelm and Grossman (2010) describe a participant who showed rather minimal heart rate increases in response to a laboratory stressor (about five to 10 beats per minute) but quite dramatic increases (almost 50 beats per minute) later in the afternoon while watching a soccer game. Of course, the reverse pattern can happen as well, such as when patients have high blood pressure in the doctor’s office but not in their home environment—the so-called white coat hypertension (White, Schulman, McCabe, & Dey, 1989).

Ambulatory physiological monitoring – that is, monitoring physiological reactions as people go about their daily lives - has a long history in biomedical research and an array of monitoring devices exist (Fahrenberg & Myrtek, 1996). Among the biological signals that can now be measured in daily life with portable signal recording devices are the electrocardiogram (ECG), blood pressure, electrodermal activity (or “sweat response”), body temperature, and even the electroencephalogram (EEG) (Wilhelm & Grossman, 2010). Most recently, researchers have added ambulatory assessment of hormones (e.g., cortisol) and other biomarkers (e.g., immune markers) to the list (Schlotz, 2012). The development of ever more sophisticated ways to track what goes on underneath our skins as we go about our lives is a fascinating and rapidly advancing field.

In a recent study, Lane, Zareba, Reis, Peterson, and Moss (2011) used experience sampling combined with ambulatory electrocardiography (a so-called Holter monitor) to study how emotional experiences can alter cardiac function in patients with a congenital heart abnormality (e.g., long QT syndrome). Consistent with the idea that emotions may, in some cases, be able to trigger a cardiac event, they found that typical—in most cases even relatively low intensity— daily emotions had a measurable effect on ventricular repolarization, an important cardiac indicator that, in these patients, is linked to risk of a cardiac event. In another study, Smyth and colleagues (1998) combined experience sampling with momentary assessment of cortisol, a stress hormone. They found that momentary reports of current or even anticipated stress predicted increased cortisol secretion 20 minutes later. Further, and independent of that, the experience of other kinds of negative affect (e.g., anger, frustration) also predicted higher levels of cortisol and the experience of positive affect (e.g., happy, joyful) predicted lower levels of this important stress hormone. Taken together, these studies illustrate how researchers can use ambulatory physiological monitoring to study how the little—and seemingly trivial or inconsequential—experiences in our lives leave objective, measurable traces in our bodily systems.

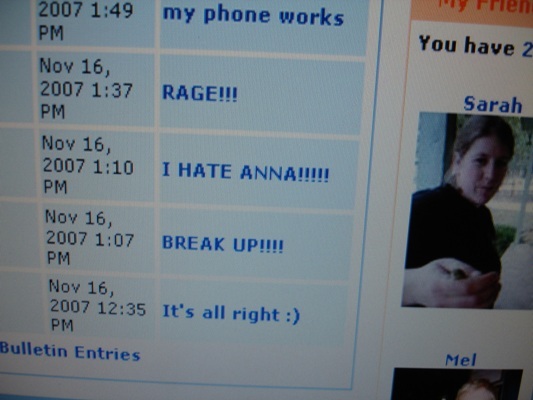

Studying Online Behavior

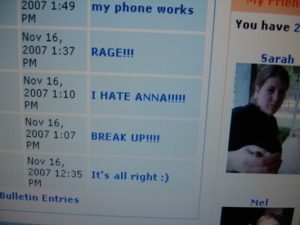

Another domain of daily life that has only recently emerged is virtual daily behavior or how people act and interact with others on the Internet. Irrespective of whether social media will turn out to be humanity’s blessing or curse (both scientists and laypeople are currently divided over this question), the fact is that people are spending an ever increasing amount of time online. In light of that, researchers are beginning to think of virtual behavior as being as serious as “actual” behavior and seek to make it a legitimate target of their investigations (Gosling & Johnson, 2010).

One way to study virtual behavior is to make use of the fact that most of what people do on the Web—emailing, chatting, tweeting, blogging, posting— leaves direct (and permanent) verbal traces. For example, differences in the ways in which people use words (e.g., subtle preferences in word choice) have been found to carry a lot of psychological information (Pennebaker, Mehl, & Niederhoffer, 2003). Therefore, a good way to study virtual social behavior is to study virtual language behavior. Researchers can download people’s—often public—verbal expressions and communications and analyze them using modern text analysis programs (e.g., Pennebaker, Booth, & Francis, 2007).

For example, Cohn, Mehl, and Pennebaker (2004) downloaded blogs of more than a thousand users of lifejournal.com, one of the first Internet blogging sites, to study how people responded socially and emotionally to the attacks of September 11, 2001. In going “the online route,” they could bypass a critical limitation of coping research, the inability to obtain baseline information; that is, how people were doing before the traumatic event occurred. Through access to the database of public blogs, they downloaded entries from two months prior to two months after the attacks. Their linguistic analyses revealed that in the first days after the attacks, participants expectedly expressed more negative emotions and were more cognitively and socially engaged, asking questions and sending messages of support. Already after two weeks, though, their moods and social engagement returned to baseline, and, interestingly, their use of cognitive-analytic words (e.g., “think,” “question”) even dropped below their normal level. Over the next six weeks, their mood hovered around their pre-9/11 baseline, but both their social engagement and cognitive-analytic processing stayed remarkably low. This suggests a social and cognitive weariness in the aftermath of the attacks. In using virtual verbal behavior as a marker of psychological functioning, this study was able to draw a fine timeline of how humans cope with disasters.

Reflecting their rapidly growing real-world importance, researchers are now beginning to investigate behavior on social networking sites such as Facebook (Wilson, Gosling, & Graham, 2012). Most research looks at psychological correlates of online behavior such as personality traits and the quality of one’s social life but, importantly, there are also first attempts to export traditional experimental research designs into an online setting. In a pioneering study of online social influence, Bond and colleagues (2012) experimentally tested the effects that peer feedback has on voting behavior. Remarkably, their sample consisted of 16 million (!) Facebook users. They found that online political-mobilization messages (e.g., “I voted” accompanied by selected pictures of their Facebook friends) influenced real-world voting behavior. This was true not just for users who saw the messages but also for their friends and friends of their friends. Although the intervention effect on a single user was very small, through the enormous number of users and indirect social contagion effects, it resulted cumulatively in an estimated 340,000 additional votes—enough to tilt a close election. In short, although still in its infancy, research on virtual daily behavior is bound to change social science, and it has already helped us better understand both virtual and “actual” behavior.

“Smartphone Psychology”?

A review of research methods for studying daily life would not be complete without a vision of “what’s next.” Given how common they have become, it is safe to predict that smartphones will not just remain devices for everyday online communication but will also become devices for scientific data collection and intervention (Kaplan & Stone, 2013; Yarkoni, 2012). These devices automatically store vast amounts of real-world user interaction data, and, in addition, they are equipped with sensors to track the physical (e. g., location, position) and social (e.g., wireless connections around the phone) context of these interactions. Miller (2012, p. 234) states, “The question is not whether smartphones will revolutionize psychology but how, when, and where the revolution will happen.” Obviously, their immense potential for data collection also brings with it big new challenges for researchers (e.g., privacy protection, data analysis, and synthesis). Yet it is clear that many of the methods described in this module—and many still to be developed ways of collecting real-world data—will, in the future, become integrated into the devices that people naturally and happily carry with them from the moment they get up in the morning to the moment they go to bed.

This module sought to make a case for psychology research conducted outside the lab. If the ultimate goal of the social and behavioral sciences is to explain human behavior, then researchers must also—in addition to conducting carefully controlled lab studies—deal with the “messy” real world and find ways to capture life as it naturally happens.

Mortensen and Cialdini (2010) refer to the dynamic give-and-take between laboratory and field research as “ full-cycle psychology ”. Going full cycle, they suggest, means that “researchers use naturalistic observation to determine an effect’s presence in the real world, theory to determine what processes underlie the effect, experimentation to verify the effect and its underlying processes, and a return to the natural environment to corroborate the experimental findings” (Mortensen & Cialdini, 2010, p. 53). To accomplish this, researchers have access to a toolbox of research methods for studying daily life that is now more diverse and more versatile than it has ever been before. So, all it takes is to go ahead and—literally—bring science to life.

Outside Resources

Discussion questions.

- What do you think about the tradeoff between unambiguously establishing cause and effect (internal validity) and ensuring that research findings apply to people’s everyday lives (external validity)? Which one of these would you prioritize as a researcher? Why?

- What challenges do you see that daily-life researchers may face in their studies? How can they be overcome?

- What ethical issues can come up in daily-life studies? How can (or should) they be addressed?

- How do you think smartphones and other mobile electronic devices will change psychological research? What are their promises for the field? And what are their pitfalls?

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Funder, D. C. (2007). Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2 , 396–403.

- Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J-P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616.

- Bond, R. M., Jones, J. J., Kramer, A. D., Marlow, C., Settle, J. E., & Fowler, J. H. (2012). A 61 million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature , 489, 295–298.

- Brewer, M. B. (2000). Research design and issues of validity. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social psychology (pp. 3–16). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohn, M. A., Mehl, M. R., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2004). Linguistic indicators of psychological change after September 11, 2001. Psychological Science, 15, 687–693.

- Conner, T. S., Tennen, H., Fleeson, W., & Barrett, L. F. (2009). Experience sampling methods: A modern idiographic approach to personality research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3 , 292–313.

- Craik, K. H. (2000). The lived day of an individual: A person-environment perspective. In W. B. Walsh, K. H. Craik, & R. H. Price (Eds.), Person-environment psychology: New directions and perspectives (pp. 233–266). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Fahrenberg, J., &. Myrtek, M. (Eds.) (1996). Ambulatory assessment: Computer-assisted psychological and psychophysiological methods in monitoring and field studies . Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber.

- Funder, D. C. (2007). The personality puzzle . New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

- Funder, D. C. (2001). Personality. Review of Psychology, 52, 197–221.

- Gosling, S. D., & Johnson, J. A. (2010). Advanced methods for conducting online behavioral research . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Gosling, S. D., Ko, S. J., Mannarelli, T., & Morris, M. E. (2002). A room with a cue: Personality judgments based on offices and bedrooms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82 , 379–398.

- Hektner, J. M., Schmidt, J. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2007). Experience sampling method: Measuring the quality of everyday life . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kahneman, D., Krueger, A., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., and Stone, A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The Day Reconstruction Method. Science , 306, 1776–780.

- Kaplan, R. M., & Stone A. A. (2013). Bringing the laboratory and clinic to the community: Mobile technologies for health promotion and disease prevention. Annual Review of Psychology, 64 , 471-498.

- Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science , 330, 932.

- Lane, R. D., Zareba, W., Reis, H., Peterson, D., &, Moss, A. (2011). Changes in ventricular repolarization duration during typical daily emotion in patients with Long QT Syndrome. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73 , 98–105.

- Lewin, K. (1944) Constructs in psychology and psychological ecology . University of Iowa Studies in Child Welfare, 20, 23–27.

- Mehl, M. R., & Conner, T. S. (Eds.) (2012). Handbook of research methods for studying daily life . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Mehl, M. R., Pennebaker, J. W., Crow, M., Dabbs, J., & Price, J. (2001). The electronically activated recorder (EAR): A device for sampling naturalistic daily activities and conversations. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 33 , 517–523.

- Mehl, M. R., Robbins, M. L., & Deters, G. F. (2012). Naturalistic observation of health-relevant social processes: The electronically activated recorder (EAR) methodology in psychosomatics. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74 , 410–417.

- Mehl, M. R., Vazire, S., Ramírez-Esparza, N., Slatcher, R. B., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2007). Are women really more talkative than men? Science, 317 , 82.

- Miller, G. (2012). The smartphone psychology manifesto. Perspectives in Psychological Science , 7, 221–237.

- Mortenson, C. R., & Cialdini, R. B. (2010). Full-cycle social psychology for theory and application. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 53–63.

- Pennebaker, J. W., Mehl, M. R., Niederhoffer, K. (2003). Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annual Review of Psychology, 54 , 547–577.

- Ramírez-Esparza, N., Mehl, M. R., Álvarez Bermúdez, J., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2009). Are Mexicans more or less sociable than Americans? Insights from a naturalistic observation study. Journal of Research in Personality, 43 , 1–7.

- Rathje, W., & Murphy, C. (2001). Rubbish! The archaeology of garbage . New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Reis, H. T., & Gosling, S. D. (2010). Social psychological methods outside the laboratory. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey, (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 82–114). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: A guide to stress, stress-related diseases and coping . New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co.

- Schlotz, W. (2012). Ambulatory psychoneuroendocrinology: Assessing salivary cortisol and other hormones in daily life. In M.R. Mehl & T.S. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 193–209). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Smyth, J., Ockenfels, M. C., Porter, L., Kirschbaum, C., Hellhammer, D. H., & Stone, A. A. (1998). Stressors and mood measured on a momentary basis are associated with salivary cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23 , 353–370.

- Stone, A. A., & Shiffman, S. (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16 , 199–202.

- Stone, A. A., Reed, B. R., Neale, J. M. (1987). Changes in daily event frequency precede episodes of physical symptoms. Journal of Human Stress, 13 , 70–74.

- Webb, E. J., Campbell, D. T., Schwartz, R. D., Sechrest, L., & Grove, J. B. (1981). Nonreactive measures in the social sciences . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- White, W. B., Schulman, P., McCabe, E. J., & Dey, H. M. (1989). Average daily blood pressure, not office blood pressure, determines cardiac function in patients with hypertension. Journal of the American Medical Association, 261 , 873–877.

- Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces . Washington, DC: The Conservation Foundation.

- Wilhelm, F.H., & Grossman, P. (2010). Emotions beyond the laboratory: Theoretical fundaments, study design, and analytic strategies for advanced ambulatory assessment. Biological Psychology, 84 , 552–569.

- Wilhelm, P., Perrez, M., & Pawlik, K. (2012). Conducting research in daily life: A historical review. In M. R. Mehl & T. S. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Wilson, R., & Gosling, S. D., & Graham, L. (2012). A review of Facebook research in the social sciences. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7 , 203–220.

- Yarkoni, T. (2012). Psychoinformatics: New horizons at the interface of the psychological and computing sciences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21 , 391–397.

Bridging the Lab and the Real World

- Applied Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Infant Development

- Sign Language

Whether and to what degree discoveries made in the lab generalize to the real world has been a long-standing debate among researchers of all stripes. New advances in technology and methodologies are enabling psychological scientists to bridge this divide and bring the controlled assessment of the lab into the world at large. Five researchers working in a variety of areas came together at the 2017 International Convention of Psychological Science in Vienna, to discuss the ways in which they balance, combine, and synergize the confines of the lab with the complex reality of our world.

Gesturing Toward Language

APS Past President Susan Goldin-Meadow of th University of Chicago uses a combination of lab-based and real-world environments to examine another aspect of infant development: gesture and its relation to language acquisition. It may seem intuitive that children use gestures as a stand-in for words they don’t know or can’t yet say, but Goldin-Meadow has found the movements are more than that. Pointing gestures not only function like words in children’s speech, but may actually be part of the word-learning process.

Goldin-Meadow first found indications of this by comparing the spontaneous gesture production of typically developing 14-month-old children with their vocabulary at 54 months. In addition to a correlation between gesture and vocabulary, she also found that the well-established positive association between socioeconomic status and child vocabulary size can be partially mediated by gesture production at 14 months.

To go deeper into this relationship and investigate the possible causal role of gesture, experimenters manipulated gesture production during a series of experimental sessions in the children’s homes. Experimenters did not use gesture in their sessions, used gesture but did not instruct the child to do so, or gestured and encouraged the child to do the same. Children who were told to gesture used more words in a follow-up assessment than did those who had only witnessed the experimenter gesture or who saw no gestures at all. They also produced more gestures with their parents outside of the experimental session. Because the experimenters manipulated gesture, the findings provide convincing evidence that gesturing can play a causal role in word learning.

In a series of lab-based studies (which will be followed up by neuroimaging studies), Goldin-Meadow also found that performing a gesture of an action (e.g., miming the turning of a knob) helps children better generalize that word to other knob-turning situations than does simply turning the knob themselves.

These observations about children’s use of gesturing and language in the real world, supported by laboratory testing, demonstrate how these two settings can work synergistically to provide us with new insights into development.

Just Moving to Move

APS Fellow Karen Adolph , a professor of psychology at New York University, aims to capture the complexity of infant learning beyond what has been observed in the lab. For example, technological advances such as head-mounted eye tracking for mobile infants have revealed that they don’t attend to their caregivers’ faces as much as previously believed — in one study, Adolph found that infants spent about 16% of the time looking at their parents and only 5% of the time focused specifically on parents’ faces.

Lab setups to study infant walking typically involve getting subjects to walk in a continuous, forward, straight path through a designated recording area. But infant ambulation in the real world is often far from a continuous, forward, straight path — babies stop and start, walk in every direction, and move in curves. These components were previously not able to be studied in the lab-based paradigm, but a larger recording area with a pressure-sensitive floor has enabled researchers to track how babies walk freely around a room.

Technological advances have allowed Adolph to investigate not just how babies walk, but why. Young children were typically theorized to use walking to get to a destination that they can see but that is not reachable from their current position. Using the same eye-tracking technology as the previous experiment, Adolph found that these destination-based bouts of walking account for only about 18% of toddlers’ movement. Sometimes they look toward one destination but then walk to another in what Adolph terms “discovery bouts,” accounting for about 10% of their walking trips. Babies, it turns out, are largely wanderers; most bouts do not have a destination at all.

“They are just moving to move,” says Adolph.

While lab tasks have the advantage of being well-controlled, Adolph’s findings reveal how they fail to capture the full picture.

“The cost of over-simplifying behaviors is that we lose sight of the phenomenon that we want to study,” she said. “In developmental psychology, over-reliance on laboratory tasks has led us to develop erroneous and superfluous theories about infant development.”

Adolph hopes to correct this trend moving forward.

Attention in Detail

To draw clear conclusions about the complex construct of attention, lab-based studies have typically separated out two main aspects of attentional shifting. These shifts can be driven by endogenous signals, which are voluntary and strategic (e.g., searching for a specific target), or exogenous signals, where attention is automatically shifted in response to an external stimulus — a more reflexive reaction.

Voluntary attentional shifting has been linked to the dorsal frontoparietal (dFP) region of the brain, while the ventral frontoparietal (vFP) area has been thought to primarily mediate reflexive shifts, though more recent evidence suggests the two systems may also interact and overlap with each other.

The lab studies that have provided these insights, however, use primarily stereotyped paradigms and simple, repeated stimuli, a far cry from the cohesive, complex visuospatial landscape we encounter in our everyday lives. Recent technological advances in eye tracking, saliency maps, and imaging methods have enabled researchers like Emiliano Macaluso, a professor at the Lyon Neuroscience Research Center, to study attention in a more naturalistic setting, where stimuli are more numerous and dynamic and where there is not always an explicit task to be done or goal to be achieved.

Macaluso has used dynamic visual environments, including first-person perspective videos and virtual environment setups, to examine how attentional shift is mediated in the brain under different conditions and to compare the responses of healthy subjects with those of subjects with lesions in the vFP region. Throughout these studies, he also has mapped and compared brain activation in individuals when viewing task-relevant objects and objects that were relevant only to a previous task, as well as when shifting their attention toward salient stimuli. These activation patterns were largely segregated between the ventral and dorsal networks, but also revealed greater nuance in how the brain controls attention, as the vFP was found to play a role in orienting attention toward task-relevant objects, and lesions in the ventral region interfered with this processing. Conversely, the dFP was activated during orientation toward salient events and locations.

Macaluso hopes to continue using these naturalistic settings to gain even greater insight into how the brain mediates the processes of attentional control.

Language Richness and Reward