Report Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System

Easily browse the critical components of this report…

Introduction

Throughout the nation, people of color are far more likely to enter the nation’s justice system than the general population. State and federal governments are aware of this disparity, and researchers and policymakers are studying the drivers behind the statistics and what strategies might be employed to address the disparities, ensuring evenhanded processes at all points in the criminal justice system. This primer highlights data, reports, state laws, innovations, commissions, approaches and other resources addressing racial and ethnic disparities within our country’s justice systems, to provide information for the nation’s decision-makers, state legislators.

Examining the Data and Innovative Justice Responses to Address Disparities

For states to have a clear understanding of the extent of racial and ethnic disparities in the states, they need to have data from all stages of the criminal justice system.

1. Law Enforcement

Disparities within traffic stops.

Contact with law enforcement, particularly at traffic stops, is often the most common interaction people have with the criminal legal system.

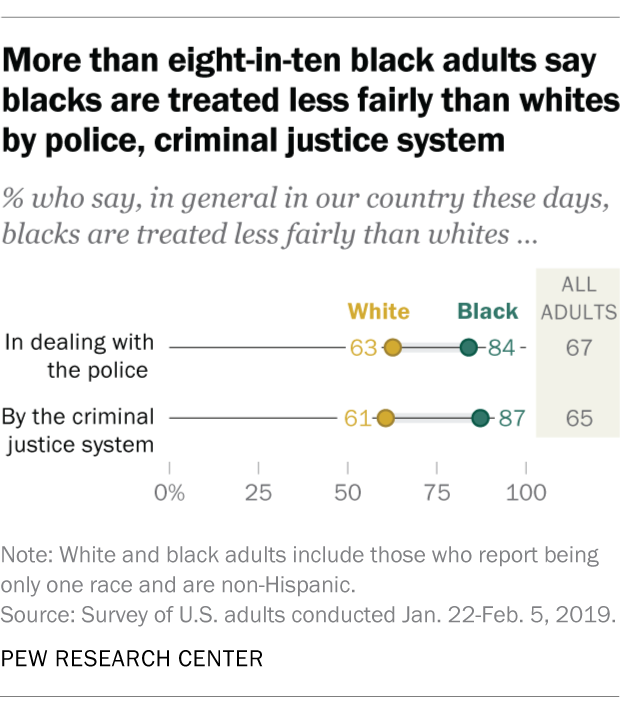

According to a large-scale analysis of racial disparities in police stops across the United States , “police stop and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias.” The study, the largest to date, analyzed data on approximately 95 million stops from 21 state patrol agencies and 35 municipal police departments across the country. The authors found Black drivers were less likely to be stopped after sunset, when it is more difficult to determine a driver’s race, suggesting bias in stop decisions. Furthermore, by examining the rate at which stopped drivers were searched and turned up contraband, the study found that the bar for searching Black and Hispanic drivers was lower than that for searching white drivers.

The study also investigated the effects of legalization of recreational cannabis on racial disparities in stop outcomes—specifically examining Colorado and Washington, two of the first states to legalize the substance. It found that following the legalization of cannabis, the number of total searches fell substantially. The authors theorized this may have been due to legalization removing a common reason officers cite for conducting searches. Nevertheless, Black and Hispanic drivers were still more likely to be searched than white drivers were post-legalization.

Data Collection Requirements in Statute

At least 23 states and the District of Columbia have laws related to or requiring collection of data when an individual is stopped by law enforcement. Some of these laws specifically prohibit racial profiling or require departments to adopt a policy to the same effect. Collection of demographic data can serve as a means of ensuring compliance with those provisions or informing officials on current practices so they can respond accordingly.

States have employed many reporting or other requirements for evaluation of the data collected under these laws. For example, Montana requires agencies to adopt a policy that provides for periodic reviews to “determine whether any peace officers of the law enforcement agency have a pattern of stopping members of minority groups for violations of vehicle laws in a number disproportionate to the population of minority groups residing or traveling within the jurisdiction…”

Maryland’s law requires local agencies to report their data to the Maryland Statistical Analysis Center. The center is then tasked with analyzing the annual reports from local agencies and posting the data in an online display that is filtered by jurisdiction and by each data point collected by officers.

The amount and kind of data collected also varies state by state. Some states leave the specifics to local jurisdictions or require the creation of a form based on statutory guidance, but most require the collection of demographic data including race, ethnicity, color, age, gender, minority group or state of residence. Notably, Missouri’s law requires collection of the following 10 data points:

- The age, gender and race or minority group of the individual stopped.

- The reasons for the stop.

- Whether a search was conducted because of the stop.

- If a search was conducted, whether the individual consented to the search, the probable cause for the search, whether the person was searched, whether the person’s property was searched, and the duration of the search.

- Whether any contraband was discovered during the search and the type of any contraband discovered.

- Whether any warning or citation was issued because of the stop.

- If a warning or citation was issued, the violation charged or warning provided.

- Whether an arrest was made because of either the stop or the search.

- If an arrest was made, the crime charged.

- The location of the stop.

State laws differ as to what kind of stop triggers a data reporting requirement. For example, Florida’s law applies to stops where citations are issued for violations of the state’s safety belt law. While Virginia’s law is broader, requiring all law enforcement to collect data pertaining to all investigatory motor vehicle stops, all stop-and-frisks of a person and all other investigatory detentions that do not result in arrest or the issuance of a summons.

Cultural Competency and Bias Reduction Training for Law Enforcement

At least 48 states and the District of Columbia have statutory training requirements for law enforcement. These laws require law enforcement personnel statewide to be trained on specific topics during their initial training and/or at recurring intervals, such as in-service training or continuing education.

In most states, the law simply requires training on a subject, leaving the specifics to be determined by state training boards or other local authorities designated by law. However, some states, such as Iowa and West Virginia, have very detailed requirements and even specify how many hours are required, the subject of the training, required content, whether the training must be received in person and who is approved to provide the training.

Overall, at least 26 states mandate some form of bias reduction training. Find out more about these laws on NCSL’s Law Enforcement Training webpage.

Law Enforcement Employment and Labor Policies

States have also addressed equity and accountability in policing through certification and accountability measures and hiring practices.

For example, a 2020 California law ( AB 846 ) changed state certification requirements by expanding current officer evaluations to screen for various kinds of bias in addition to physical, emotional or mental conditions that might adversely affect an officer’s exercise of peace officer powers. The law also requires the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training to study, review and update regulations and screening materials to identify explicit and implicit bias against race or ethnicity, gender, nationality, religion, disability or sexual orientation related to emotional and mental condition evaluations.

In addition to screening, the California law requires every department or agency that employs peace officers to review the job descriptions used in recruitment and hiring and to make changes that deemphasize the paramilitary aspects of the job. The intent is to place more emphasis on community interaction and collaborative problem-solving.

Nevada ( AB 409 ), in 2021, added to statutory certification requirements mandating evaluation of officer recruits to identify implicit bias on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, physical or mental disability, sexual orientation or gender identity expression. That same year, Nevada also enacted legislation ( SB 236 ) that requires law enforcement agencies to establish early warning systems to identify officers who display bias indicators or demonstrate other problematic behavior. It also requires increased supervision, training and, if appropriate, counseling to officers identified by the system. If an officer is repeatedly identified by the early warning system, the law requires the employing agency to consider consequences, including transfer from high-profile assignments or other means of discipline.

Another area of interest for states has been hiring a more diverse workforce in law enforcement and support agencies. For example, New Jersey SB 2767 (2020) required the state Civil Service Commission to conduct a statewide diversity analysis of the ethnic and racial makeup of all law enforcement agencies in the state.

Finally, at least one state addressed bias in policing through a state civil rights act. Massachusetts ( SB 2963 ) established a state right to bias-free professional policing. Conduct against an aggrieved person resulting in decertification by the Police Office Standards and Training Commission constitute a prima-facie violation of the right to bias-free professional policing. The law also specifies that no officer is immune from civil liability for violating a person’s right to bias-free professional policing if the conduct results in officer decertification.

Disproportionality of Native Americans in the Justice System According to the U.S. Department of Justice, from 2015 to 2019, the number of American Indian or Alaska Native justice-involved individuals housed in local jails for federal correctional authorities, state prison authorities or tribal governments increased by 3.6% . Though American Indian and Alaska Natives make up a small proportion of the national incarcerated population relative to other ethnicities, some jurisdictions are finding they are disproportionately represented in the justice system. For example, in Pennington County , S.D., it is estimated that 10% to 25% of the county’s residents are Native American, but they account for 55% of the county’s jail population. Similarly, Montana’s Commission on Sentencing found that while Native Americans represent 7% of the state’s general population, they comprised 17% of those incarcerated in correctional facilities in 2014 and 19% of the state’s total arrests in 2015.

Modal title

2. pretrial release and prosecution, risk assessments.

Recently, state laws have authorized or required courts to use pretrial risk assessment tools. There are about two dozen pretrial risk assessment tools in use across the states.

Laws in Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, New Jersey and Vermont require courts to adopt or consider risk assessments in at least some, if not all, cases on a statewide basis. While laws in Colorado, Illinois, Montana, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia and West Virginia authorize or encourage, but do not require, adopting a risk assessment tool on a statewide basis.

This broad state adoption of risk assessment tools raises concern that systemic bias may impact their use. In 2014, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said pretrial risk assessment tools “may exacerbate unwarranted and unjust disparities that are already far too common in our criminal justice system and our society.”

More than 100 civil rights organizations expressed similar concerns in a statement following a 2017 convening. The dependance of pretrial risk assessment tools on data that reflect systemic bias is the crux of the issue. The statement highlights that police officers disproportionately arrest people of color, which impacts risk assessment tools that rely on arrest data. The statement then set out key principles mitigating harm that may be caused by risk assessments, recognizing their broad use across the country.

The conversation about bias in pretrial risk assessments is ongoing. In 2021, the Urban Institute published the report “ Racial Equity and Criminal Justice Risk Assessment .” In the report, the authors discuss and make recommendations for policymakers to balance the use of risk assessment as a component of evidence-based practice with pursuing goals of reducing racial and ethnic disparities. The authors state that “carefully constructed and properly used risk assessment instruments that account for fairness can help limit racial bias in criminal justice decision-making.”

Academic studies show varied results related to the use of risk assessments and their effect on racial and ethnic disparities in the justice system. One study, “ Racist Algorithms or Systemic Problems ,” concludes “there is currently no valid evidence that instruments in general are biased against individuals of color,” and, “Where bias has been found, it appears to have more to do with the specific risk instrument.” In another study, “ Employing Standardized Risk Assessment in Pretrial Release Decisions ,” the authors, without making causal conclusions, find that “despite comparable risk scores, African American participants were detained significantly longer than Caucasian participants … and were less likely to receive diversion opportunity.”

In a recent report titled “ Civil Rights and Pretrial Risk Assessment Instruments ,” the authors recommend steps to protect civil rights when risk assessment tools are used. The report underscores the importance of expansive transparency throughout design and implementation of these tools. It also suggests more community oversight and governance that promotes reduced incarceration and racially equitable outcomes. Finally, the report suggests decisions made by judges to detain should be rare, deliberate and not dependent solely on pretrial risk assessment instruments.

States are starting to regulate the use of risk assessments and promote best practices by requiring the tool to be validated on a regular basis, be free from racial or gender bias and that documents, data and records related to the tool be publicly available.

For example, California (2019 SB 36 ) requires a pretrial services agency validate pretrial risk assessment tools on a regular basis and to make specified information regarding the tool, including validation studies, publicly available. The law also requires the judicial council to maintain a list of pretrial services agencies that have satisfied the validation requirements and complied with the transparency requirements. California published its most recent validation report in June 2021.

Similarly, Idaho (2019 HB 118 ) now requires all documents, data, records and information used to build and validate a risk assessment tool to be publicly available for inspection, auditing and testing. The law requires public availability of ongoing documents, data, records and written policies on usage and validation of a tool. It also authorizes defendants to have access to calculations and data related to their own risk score and prohibits the use of proprietary tools.

Pretrial Release

A recent report from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights evaluates the civil rights implications of pretrial release systems across the country.

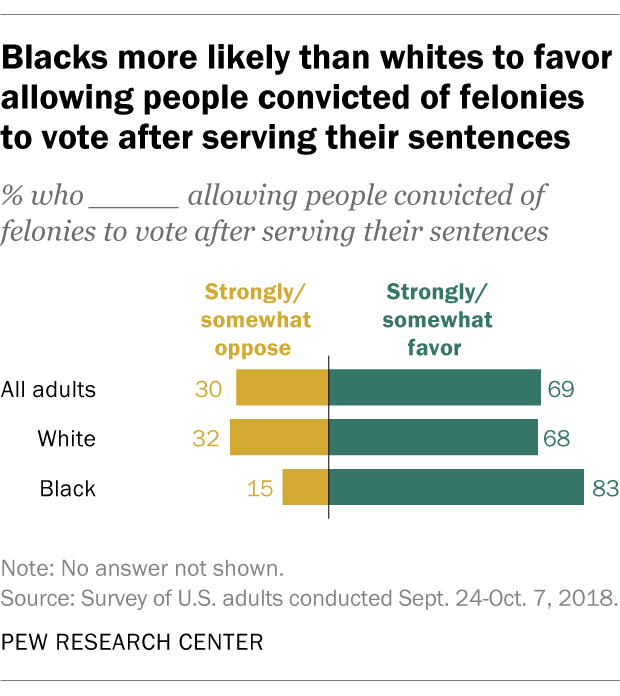

Notable findings from the report include stark racial and gender disparities in pretrial populations with higher detention rates and financial conditions of release imposed on minority populations. The report also finds that more than 60% of defendants are detained pretrial because of an inability to pay financial conditions of release.

States have recently enacted legislation to address defendants’ ability to pay financial conditions of release, with at least 11 states requiring courts to conduct ability-to-pay considerations when setting release conditions. NCSL’s Statutory Framework of Pretrial Release report has additional information about state approaches to pretrial release.

Prosecutorial Discretion

Prosecutorial discretion is a term used to describe the power of prosecutors to decide whether to charge a person for a crime, which criminal charges to file and whether to enter into a plea agreement. Some argue this discretion can be a source of disparities within the criminal justice system.

The Prosecutorial Performance Indicators (PPI), developed by Florida International University and Loyola University Chicago, is an example of an effort to address this. PPI provides prosecutors’ offices with a method to measure their performance through several indicators, including racial and ethnic disparities. As part of their work to bring accountability and oversight to prosecutorial discretion, PPI has created six measures specifically related to racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system. The PPI measures include the following:

- Victimization of Racial/Ethnic Minorities.

- Case Dismissal Differences by Victim Race/Ethnicity.

- Case Filing Differences by Defendant Race/Ethnicity.

- Pretrial Detention Differences by Defendant Race/Ethnicity.

- Diversion Differences by Defendant Race/Ethnicity.

- Charging and Plea Offer Differences by Defendant Race/Ethnicity.

Below is a table highlighting disparity data discovered through the use of PPI measures , gathered from specific jurisdictions.

| Point of Discretion/Jurisdiction | Disparity Data from PPI |

|---|---|

Young People in the Justice System

As is the case in the adult system, compared to young white people, youth of color are disproportionately represented at every stage in the nation’s juvenile justice system. Overall juvenile placements fell by 54% between 2001 and 2015, but the placement rate for Black youth was 433 per 100,000, compared to a white youth placement rate of 86 per 100,000. According to a report from the Prison Policy Initiative, an advocacy organization, titled “ Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie 2019 ,” 14% of all those younger than 18 in the U.S. are Black, but they make up 42% of the boys and 35% of the girls in juvenile facilities. Additionally, Native American and Hispanic girls and boys are also overrepresented in the juvenile justice system relative to their share of the total youth population. Information from California reveals that prosecutors send Hispanic youth to adult court via “direct file” at over three times the rate of white youth.

At the federal level, the 2018 reauthorized Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act requires states to identify and analyze data on race and ethnicity in state, local and tribal juvenile justice systems. States must identify disparities and develop and implement work plans to address them. States are required to document how they are addressing racial and ethnic disparities and establish a coordinating body composed of juvenile justice stakeholders to advise states, units of local government and Native American tribes. If a state fails to meet the act’s requirements, it will result in a 20% reduction of formula grant funding.

An example of a coordinating council that has examined extensive data is the Equity and Justice for All Youth Subcommittee of the Georgia Juvenile Justice State Advisory Group . The group conducted a county-by-county assessment and analysis of disproportionality in Georgia and found one of the most effective ways to reduce disproportionate treatment of youth is to reduce harsh disciplinary measures in schools. This in turn helps reduce disproportionate referrals to the system.

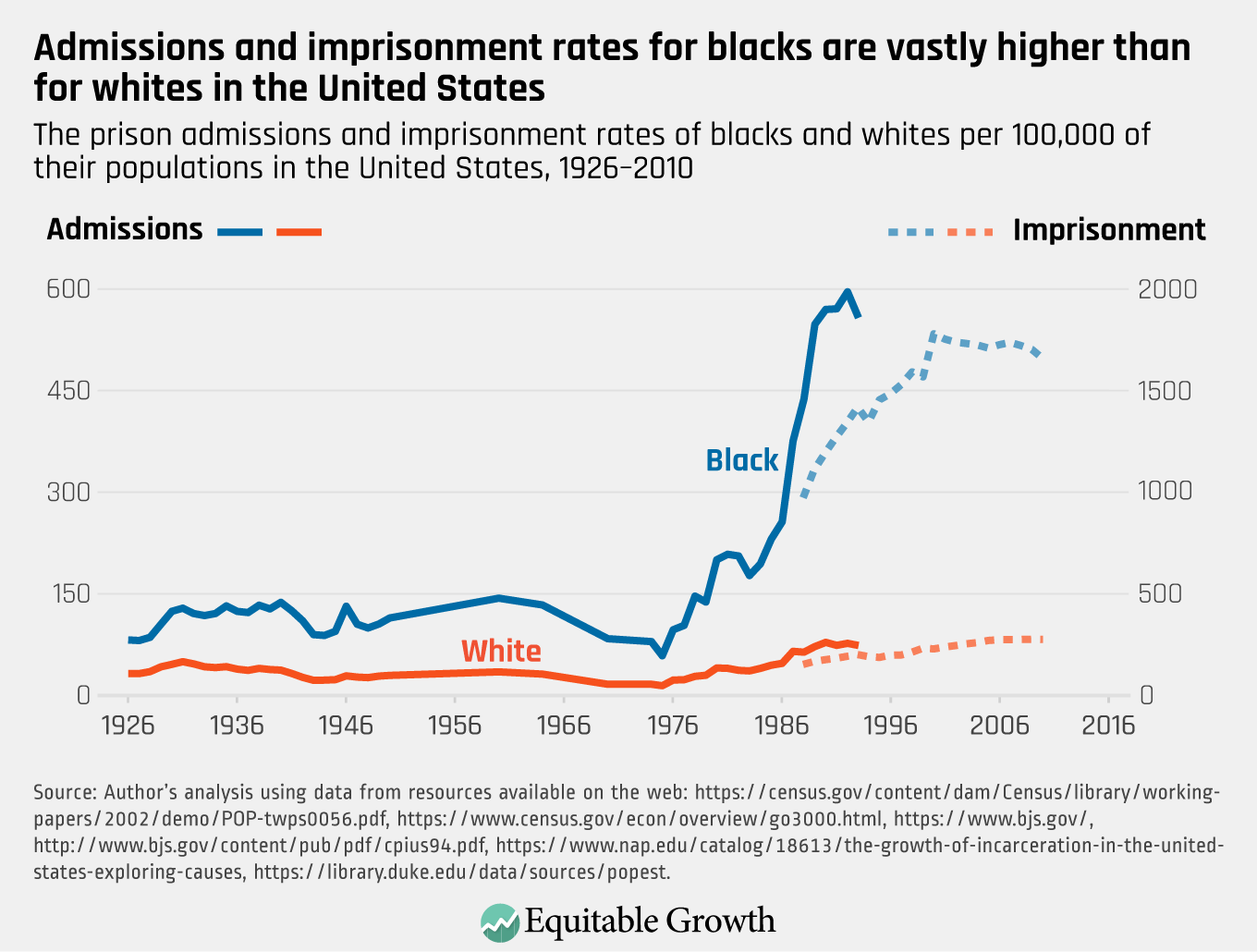

3. Incarceration

Incarceration statistics help paint a picture of the disparities in the criminal justice system. Significant racial and ethnic disparities can be seen in both jails and prisons. According to the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge website , “While Black and Latinx people make up 30% of the U.S. population, they account for 51% of the jail population.”

An October 2021 report from The Sentencing Project, an organization advocating for criminal justice reform, found that “Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at nearly five times the rate of whites, and Latinx people are 1.3 times as likely to be incarcerated than non-Latinx whites.” At the time of the report, there were 12 states where more than half of the prison population is Black and seven states with a disparity between the Black and white imprisonment rate of more than 9 to 1.

To have a clearer sense of the racial makeup of who is incarcerated at any given time, some systems developed data dashboards to provide information on their jail populations. In Allegheny County, Pa., for instance, the jail data dashboard is publicly available and provides a range of information on who is incarcerated in the jail. The dashboard provides an up-to-the-day look at the race, gender and age of the jail population. According to the dashboard, on average from Jan. 1, 2019, to mid-November 2021, 65% of individuals in the jail were Black.

Dashboards may also be established by the individual state, though these generally look back over a specified time, rather than providing a close-to-live look at the jail population. Colorado passed a law in 2019 ( HB 1297 ) requiring county jails to collect certain data and report it to the state Division of Criminal Justice on a quarterly basis. That data is compiled in a publicly available Jail Data Dashboard . The dashboard includes information on the racial and ethnic makeup of jail populations in the state. In the second quarter of 2021, 88% of people incarcerated in jails in the state were white, 16% were Black, 2% were Native American and 1% were classified as “other race.” In the same quarter, ethnicity data for incarcerated people showed 67% were non-Hispanic, 33% were Hispanic and 9% were classified with “unknown ethnicity.”

Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections has an online dashboard providing similar information for the state prison population. The dashboard shows Black people make up 12% of the state’s overall population but 44% of the population in state correctional institutions, while white people make up 74% of the state population and 45% of the state prison population. While dashboards themselves don’t reduce disparities, they help create a clearer understanding of them.

4. Sentencing

Racial and ethnic disparities can also be seen in the sentencing of individuals following a criminal conviction. The use of sentencing enhancements and federal drug sentencing both provide examples of the disparities in sentencing.

Sentencing enhancements in California have been found to be applied disproportionately to people of color and individuals with mental illness according to the state’s Committee on Revision of the Penal Code . More than 92% of the people sentenced for a gang enhancement in the state, for instance, are Black or Hispanic. The state has more than 150 different sentence enhancements and more than 80% of people incarcerated in the state are subject to a sentence enhancement.

In response to recommendations from the committee, AB 333 was enacted in 2021 to modify the state’s gang enhancement statutes by reducing the list of crimes under which use of the current charge alone creates proof of a “pattern” of criminal gang activity and separates gang allegations from underlying charges at trial.

Impact Statements and Legislative Task Forces

Racial impact statements and data.

Legislatures are currently taking many steps to increase their understanding of racial and ethnic disparities in the justice system. In some states, this has taken the form of racial and ethnic impact statements or corrections impact statements.

At least 18 states require corrections impact statements for legislation that would make changes to criminal offenses and penalties. These look at the fiscal impact of policy changes on correctional populations and criminal justice resources. A few states have required the inclusion of information on the impacts of policy changes on certain racial and ethnic groups.

Colorado has taken this approach. The state enacted legislation in 2013 (SB 229) requiring corrections fiscal notes to include information on gender and minority data. In 2019, the state passed legislation (HB 1184) requiring the staff of the legislative council to prepare demographic notes for certain bills. These notes use “available data to outline the potential effects of a legislative measure on disparities within the state, including a statement of whether the measure is likely to increase or decrease disparities to the extent the data is available.”

Other states with laws requiring racial and ethnic impact statements include Connecticut , Iowa , Maine , New Hampshire , New Jersey , Oregon and Virginia . Additionally, Florida announced a partnership in July 2019 “between the Florida Senate and Florida State University’s College of Criminology & Criminal Justice to analyze racial and ethnic impacts of proposed legislation.” Minnesota’s Sentencing Commission has compiled racial impact statements for the legislature since 2006, though this is not required in law.

Legislative Studies and Task Forces

States are also taking a closer look at racial disparities within criminal justice systems by creating legislative studies or judicial task forces. These bodies examined disproportionalities in the criminal justice system, investigated possible causes and recommended solutions.

In 2018, Vermont legislatively established the state’s Racial Disparities in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice System Advisory Panel . The panel submitted its report to the General Assembly in 2019. Part of the report recommended instituting a public complaint process with the state’s Human Rights Commission to address perceived implicit bias across all state government systems. It also recommended training first responders to identify mental health needs, educating all law enforcement officers on bias and racial disparities and adopting a community policing paradigm. Finally, the panel agreed that increased and improved data collection was important to combat racial and ethnic disparities in the justice system. The panel recommended “developing laws and rules that will require data collection that captures high-impact, high-discretion decision points that occur during the judicial processes.”

State lawmakers are well positioned to make policy changes to address the racial and ethnic disparities that research has shown are present throughout the criminal justice system. As they continue to develop a greater understanding of these disparities, state legislatures have an opportunity to make their systems fairer for all individuals who encounter the justice system, with the goal of reducing or eliminating racial and ethnic disparities.

- NCSL on View the PDF Report NCSL

DO NOT DELETE - NCSL Search Page Data

Related resources, balancing public safety and the rights of people awaiting trial.

Pretrial justice policy was the subject of a recent NCSL Town Hall with state Sens. Elgie Sims of Illinois and Brian Pettyjohn of Delaware.

Cannabis Overview

Law enforcement training, contact ncsl.

For more information on this topic, use this form to reach NCSL staff.

- What is your role? Legislator Legislative Staff Other

- Is this a press or media inquiry? No Yes

- Admin Email

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Boston busing in 1974 was about race. Now the issue is class.

History of Chichén Itzá written in DNA

Examining the duality of Israel

Protesters take a knee in front of New York City police officers during a solidarity rally for George Floyd, June 4, 2020.

AP Photo/Frank Franklin II

Solving racial disparities in policing

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Experts say approach must be comprehensive as roots are embedded in culture

“ Unequal ” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. The first part explores the experience of people of color with the criminal justice legal system in America.

It seems there’s no end to them. They are the recent videos and reports of Black and brown people beaten or killed by law enforcement officers, and they have fueled a national outcry over the disproportionate use of excessive, and often lethal, force against people of color, and galvanized demands for police reform.

This is not the first time in recent decades that high-profile police violence — from the 1991 beating of Rodney King to the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 — ignited calls for change. But this time appears different. The police killings of Breonna Taylor in March, George Floyd in May, and a string of others triggered historic, widespread marches and rallies across the nation, from small towns to major cities, drawing protesters of unprecedented diversity in race, gender, and age.

According to historians and other scholars, the problem is embedded in the story of the nation and its culture. Rooted in slavery, racial disparities in policing and police violence, they say, are sustained by systemic exclusion and discrimination, and fueled by implicit and explicit bias. Any solution clearly will require myriad new approaches to law enforcement, courts, and community involvement, and comprehensive social change driven from the bottom up and the top down.

While police reform has become a major focus, the current moment of national reckoning has widened the lens on systemic racism for many Americans. The range of issues, though less familiar to some, is well known to scholars and activists. Across Harvard, for instance, faculty members have long explored the ways inequality permeates every aspect of American life. Their research and scholarship sits at the heart of a new Gazette series starting today aimed at finding ways forward in the areas of democracy; wealth and opportunity; environment and health; and education. It begins with this first on policing.

Harvard Kennedy School Professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people.

Photo by Martha Stewart

The history of racialized policing

Like many scholars, Khalil Gibran Muhammad , professor of history, race, and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School , traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people. This legacy, he believes, can still be seen in policing today. “The surveillance, the deputization essentially of all white men to be police officers or, in this case, slave patrollers, and then to dispense corporal punishment on the scene are all baked in from the very beginning,” he told NPR last year.

Slave patrols, and the slave codes they enforced, ended after the Civil War and the passage of the 13th amendment, which formally ended slavery “except as a punishment for crime.” But Muhammad notes that former Confederate states quickly used that exception to justify new restrictions. Known as the Black codes, the various rules limited the kinds of jobs African Americans could hold, their rights to buy and own property, and even their movements.

“The genius of the former Confederate states was to say, ‘Oh, well, if all we need to do is make them criminals and they can be put back in slavery, well, then that’s what we’ll do.’ And that’s exactly what the Black codes set out to do. The Black codes, for all intents and purposes, criminalized every form of African American freedom and mobility, political power, economic power, except the one thing it didn’t criminalize was the right to work for a white man on a white man’s terms.” In particular, he said the Ku Klux Klan “took about the business of terrorizing, policing, surveilling, and controlling Black people. … The Klan totally dominates the machinery of justice in the South.”

When, during what became known as the Great Migration, millions of African Americans fled the still largely agrarian South for opportunities in the thriving manufacturing centers of the North, they discovered that metropolitan police departments tended to enforce the law along racial and ethnic lines, with newcomers overseen by those who came before. “There was an early emphasis on people whose status was just a tiny notch better than the folks whom they were focused on policing,” Muhammad said. “And so the Anglo-Saxons are policing the Irish or the Germans are policing the Irish. The Irish are policing the Poles.” And then arrived a wave of Black Southerners looking for a better life.

In his groundbreaking work, “ The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America ,” Muhammad argues that an essential turning point came in the early 1900s amid efforts to professionalize police forces across the nation, in part by using crime statistics to guide law enforcement efforts. For the first time, Americans with European roots were grouped into one broad category, white, and set apart from the other category, Black.

Citing Muhammad’s research, Harvard historian Jill Lepore has summarized the consequences this way : “Police patrolled Black neighborhoods and arrested Black people disproportionately; prosecutors indicted Black people disproportionately; juries found Black people guilty disproportionately; judges gave Black people disproportionately long sentences; and, then, after all this, social scientists, observing the number of Black people in jail, decided that, as a matter of biology, Black people were disproportionately inclined to criminality.”

“History shows that crime data was never objective in any meaningful sense,” Muhammad wrote. Instead, crime statistics were “weaponized” to justify racial profiling, police brutality, and ever more policing of Black people.

This phenomenon, he believes, has continued well into this century and is exemplified by William J. Bratton, one of the most famous police leaders in recent America history. Known as “America’s Top Cop,” Bratton led police departments in his native Boston, Los Angeles, and twice in New York, finally retiring in 2016.

Bratton rejected notions that crime was a result of social and economic forces, such as poverty, unemployment, police practices, and racism. Instead, he said in a 2017 speech, “It is about behavior.” Through most of his career, he was a proponent of statistically-based “predictive” policing — essentially placing forces in areas where crime numbers were highest, focused on the groups found there.

Bratton argued that the technology eliminated the problem of prejudice in policing, without ever questioning potential bias in the data or algorithms themselves — a significant issue given the fact that Black Americans are arrested and convicted of crimes at disproportionately higher rates than whites. This approach has led to widely discredited practices such as racial profiling and “stop-and-frisk.” And, Muhammad notes, “There is no research consensus on whether or how much violence dropped in cities due to policing.”

Gathering numbers

In 2015 The Washington Post began tracking every fatal shooting by an on-duty officer, using news stories, social media posts, and police reports in the wake of the fatal police shooting of Brown, a Black teenager in Ferguson, Mo. According to the newspaper, Black Americans are killed by police at twice the rate of white Americans, and Hispanic Americans are also killed by police at a disproportionate rate.

Such efforts have proved useful for researchers such as economist Rajiv Sethi .

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute , Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers, a difficult task given that data from such encounters is largely unavailable from police departments. Instead, Sethi and his team of researchers have turned to information collected by websites and news organizations including The Washington Post and The Guardian, merged with data from other sources such as the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Census, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Rajiv Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers,

Courtesy photo

They have found that exposure to deadly force is highest in the Mountain West and Pacific regions relative to the mid-Atlantic and northeastern states, and that racial disparities in relation to deadly force are even greater than the national numbers imply. “In the country as a whole, you’re about two to three times more likely to face deadly force if you’re Black than if you are white” said Sethi. “But if you look at individual cities separately, disparities in exposure are much higher.”

Examining the characteristics associated with police departments that experience high numbers of lethal encounters is one way to better understand and address racial disparities in policing and the use of violence, Sethi said, but it’s a massive undertaking given the decentralized nature of policing in America. There are roughly 18,000 police departments in the country, and more than 3,000 sheriff’s offices, each with its own approaches to training and selection.

“They behave in very different ways, and what we’re finding in our current research is that they are very different in the degree to which they use deadly force,” said Sethi. To make real change, “You really need to focus on the agency level where organizational culture lies, where selection and training protocols have an effect, and where leadership can make a difference.”

Sethi pointed to the example of Camden, N.J., which disbanded and replaced its police force in 2013, initially in response to a budget crisis, but eventually resulting in an effort to fundamentally change the way the police engaged with the community. While there have been improvements, including greater witness cooperation, lower crime, and fewer abuse complaints, the Camden case doesn’t fit any particular narrative, said Sethi, noting that the number of officers actually increased as part of the reform. While the city is still faced with its share of problems, Sethi called its efforts to rethink policing “important models from which we can learn.”

Fighting vs. preventing crime

For many analysts, the real problem with policing in America is the fact that there is simply too much of it. “We’ve seen since the mid-1970s a dramatic increase in expenditures that are associated with expanding the criminal legal system, including personnel and the tasks we ask police to do,” said Sandra Susan Smith , Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice at HKS, and the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. “And at the same time we see dramatic declines in resources devoted to social welfare programs.”

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson, but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work,” said Brandon Terry, assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies.

Kris Snibble/Harvard file photo

Smith’s comment highlights a key argument embraced by many activists and experts calling for dramatic police reform: diverting resources from the police to better support community services including health care, housing, and education, and stronger economic and job opportunities. They argue that broader support for such measures will decrease the need for policing, and in turn reduce violent confrontations, particularly in over-policed, economically disadvantaged communities, and communities of color.

For Brandon Terry , that tension took the form of an ice container during his Baltimore high school chemistry final. The frozen cubes were placed in the middle of the classroom to help keep the students cool as a heat wave sent temperatures soaring. “That was their solution to the building’s lack of air conditioning,” said Terry, a Harvard assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies. “Just grab an ice cube.”

Terry’s story is the kind many researchers cite to show the negative impact of underinvesting in children who will make up the future population, and instead devoting resources toward policing tactics that embrace armored vehicles, automatic weapons, and spy planes. Terry’s is also the kind of tale promoted by activists eager to defund the police, a movement begun in the late 1960s that has again gained momentum as the death toll from violent encounters mounts. A scholar of Martin Luther King Jr., Terry said the Civil Rights leader’s views on the Vietnam War are echoed in the calls of activists today who are pressing to redistribute police resources.

“King thought that the idea of spending many orders of magnitude more for an unjust war than we did for the abolition of poverty and the abolition of ghettoization was a moral travesty, and it reflected a kind of sickness at the core of our society,” said Terry. “And part of what the defund model is based upon is a similar moral criticism, that these budgets reflect priorities that we have, and our priorities are broken.”

Terry also thinks the policing debate needs to be expanded to embrace a fuller understanding of what it means for people to feel truly safe in their communities. He highlights the work of sociologist Chris Muller and Harvard’s Robert Sampson, who have studied racial disparities in exposures to lead and the connections between a child’s early exposure to the toxic metal and antisocial behavior. Various studies have shown that lead exposure in children can contribute to cognitive impairment and behavioral problems, including heightened aggression.

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson,” said Terry, “but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work.”

Policing and criminal justice system

Alexandra Natapoff , Lee S. Kreindler Professor of Law, sees policing as inexorably linked to the country’s criminal justice system and its long ties to racism.

“Policing does not stand alone or apart from how we charge people with crimes, or how we convict them, or how we treat them once they’ve been convicted,” she said. “That entire bundle of official practices is a central part of how we govern, and in particular, how we have historically governed Black people and other people of color, and economically and socially disadvantaged populations.”

Unpacking such a complicated issue requires voices from a variety of different backgrounds, experiences, and fields of expertise who can shine light on the problem and possible solutions, said Natapoff, who co-founded a new lecture series with HLS Professor Andrew Crespo titled “ Policing in America .”

In recent weeks the pair have hosted Zoom discussions on topics ranging from qualified immunity to the Black Lives Matter movement to police unions to the broad contours of the American penal system. The series reflects the important work being done around the country, said Natapoff, and offers people the chance to further “engage in dialogue over these over these rich, complicated, controversial issues around race and policing, and governance and democracy.”

Courts and mass incarceration

Much of Natapoff’s recent work emphasizes the hidden dangers of the nation’s misdemeanor system. In her book “ Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal ,” Natapoff shows how the practice of stopping, arresting, and charging people with low-level offenses often sends them down a devastating path.

“This is how most people encounter the criminal apparatus, and it’s the first step of mass incarceration, the initial net that sweeps people of color disproportionately into the criminal system,” said Natapoff. “It is also the locus that overexposes Black people to police violence. The implications of this enormous net of police and prosecutorial authority around minor conduct is central to understanding many of the worst dysfunctions of our criminal system.”

One consequence is that Black and brown people are incarcerated at much higher rates than white people. America has approximately 2.3 million people in federal, state, and local prisons and jails, according to a 2020 report from the nonprofit the Prison Policy Initiative. According to a 2018 report from the Sentencing Project, Black men are 5.9 times as likely to be incarcerated as white men and Hispanic men are 3.1 times as likely.

Reducing mass incarceration requires shrinking the misdemeanor net “along all of its axes” said Natapoff, who supports a range of reforms including training police officers to both confront and arrest people less for low-level offenses, and the policies of forward-thinking prosecutors willing to “charge fewer of those offenses when police do make arrests.”

She praises the efforts of Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins in Massachusetts and George Gascón, the district attorney in Los Angeles County, Calif., who have pledged to stop prosecuting a range of misdemeanor crimes such as resisting arrest, loitering, trespassing, and drug possession. “If cities and towns across the country committed to that kind of reform, that would be a profoundly meaningful change,” said Natapoff, “and it would be a big step toward shrinking our entire criminal apparatus.”

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner cites the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Sentencing reform

Another contributing factor in mass incarceration is sentencing disparities.

A recent Harvard Law School study found that, as is true nationally, people of color are “drastically overrepresented in Massachusetts state prisons.” But the report also noted that Black and Latinx people were less likely to have their cases resolved through pretrial probation — a way to dismiss charges if the accused meet certain conditions — and receive much longer sentences than their white counterparts.

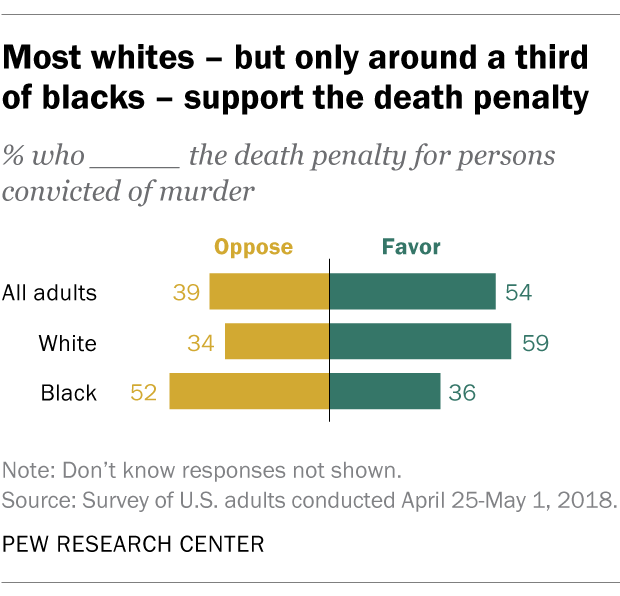

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner also notes the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons. She points to the way the 1994 Crime Bill (legislation sponsored by then-Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware) ushered in much harsher drug penalties for crack than for powder cocaine. This tied the hands of judges issuing sentences and disproportionately punished people of color in the process. “The disparity in the treatment of crack and cocaine really was backed up by anecdote and stereotype, not by data,” said Gertner, a lecturer at HLS. “There was no data suggesting that crack was infinitely more dangerous than cocaine. It was the young Black predator narrative.”

The First Step Act, a bipartisan prison reform bill aimed at reducing racial disparities in drug sentencing and signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2018, is just what its name implies, said Gertner.

“It reduces sentences to the merely inhumane rather than the grotesque. We still throw people in jail more than anybody else. We still resort to imprisonment, rather than thinking of other alternatives. We still resort to punishment rather than other models. None of that has really changed. I don’t deny the significance of somebody getting out of prison a year or two early, but no one should think that that’s reform.”

Not just bad apples

Reform has long been a goal for federal leaders. Many heralded Obama-era changes aimed at eliminating racial disparities in policing and outlined in the report by The President’s Task Force on 21st Century policing. But HKS’s Smith saw them as largely symbolic. “It’s a nod to reform. But most of the reforms that are implemented in this country tend to be reforms that nibble around the edges and don’t really make much of a difference.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Smith, who cites studies suggesting a majority of Americans hold negative biases against Black and brown people, and that unconscious prejudices and stereotypes are difficult to erase.

“Experiments show that you can, in the context of a day, get people to think about race differently, and maybe even behave differently. But if you follow up, say, a week, or two weeks later, those effects are gone. We don’t know how to produce effects that are long-lasting. We invest huge amounts to implement such police reforms, but most often there’s no empirical evidence to support their efficacy.”

Even the early studies around the effectiveness of body cameras suggest the devices do little to change “officers’ patterns of behavior,” said Smith, though she cautions that researchers are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data.

And though police body cameras have caught officers in unjust violence, much of the general public views the problem as anomalous.

“Despite what many people in low-income communities of color think about police officers, the broader society has a lot of respect for police and thinks if you just get rid of the bad apples, everything will be fine,” Smith added. “The problem, of course, is this is not just an issue of bad apples.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Sandra Susan Smith, a professor of criminal justice Harvard Kennedy School.

Community-based ways forward

Still Smith sees reason for hope and possible ways forward involving a range of community-based approaches. As part of the effort to explore meaningful change, Smith, along with Christopher Winship , Diker-Tishman Professor of Sociology at Harvard University and a member of the senior faculty at HKS, have organized “ Reimagining Community Safety: A Program in Criminal Justice Speaker Series ” to better understand the perspectives of practitioners, policymakers, community leaders, activists, and academics engaged in public safety reform.

Some community-based safety models have yielded important results. Smith singles out the Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets program (known as CAHOOTS ) in Eugene, Ore., which supplements police with a community-based public safety program. When callers dial 911 they are often diverted to teams of workers trained in crisis resolution, mental health, and emergency medicine, who are better equipped to handle non-life-threatening situations. The numbers support her case. In 2017 the program received 25,000 calls, only 250 of which required police assistance. Training similar teams of specialists who don’t carry weapons to handle all traffic stops could go a long way toward ending violent police encounters, she said.

“Imagine you have those kinds of services in play,” said Smith, paired with community-based anti-violence program such as Cure Violence , which aims to stop violence in targeted neighborhoods by using approaches health experts take to control disease, such as identifying and treating individuals and changing social norms. Together, she said, these programs “could make a huge difference.”

At Harvard Law School, students have been studying how an alternate 911-response team might function in Boston. “We were trying to move from thinking about a 911-response system as an opportunity to intervene in an acute moment, to thinking about what it would look like to have a system that is trying to help reweave some of the threads of community, a system that is more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” said HLS Professor Rachel Viscomi, who directs the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program and oversaw the research.

The forthcoming report, compiled by two students in the HLS clinic, Billy Roberts and Anna Vande Velde, will offer officials a range of ideas for how to think about community safety that builds on existing efforts in Boston and other cities, said Viscomi.

But Smith, like others, knows community-based interventions are only part of the solution. She applauds the Justice Department’s investigation into the Ferguson Police Department after the shooting of Brown. The 102-page report shed light on the department’s discriminatory policing practices, including the ways police disproportionately targeted Black residents for tickets and fines to help balance the city’s budget. To fix such entrenched problems, state governments need to rethink their spending priorities and tax systems so they can provide cities and towns the financial support they need to remain debt-free, said Smith.

Rethinking the 911-response system to being one that is “more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” is part of the student-led research under the direction of Law School Professor Rachel Viscomi, who heads up the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

“Part of the solution has to be a discussion about how government is funded and how a city like Ferguson got to a place where government had so few resources that they resorted to extortion of their residents, in particular residents of color, in order to make ends meet,” she said. “We’ve learned since that Ferguson is hardly the only municipality that has struggled with funding issues and sought to address them through the oppression and repression of their politically, socially, and economically marginalized Black and Latino residents.”

Police contracts, she said, also need to be reexamined. The daughter of a “union man,” Smith said she firmly supports officers’ rights to union representation to secure fair wages, health care, and safe working conditions. But the power unions hold to structure police contracts in ways that protect officers from being disciplined for “illegal and unethical behavior” needs to be challenged, she said.

“I think it’s incredibly important for individuals to be held accountable and for those institutions in which they are embedded to hold them to account. But we routinely find that union contracts buffer individual officers from having to be accountable. We see this at the level of the Supreme Court as well, whose rulings around qualified immunity have protected law enforcement from civil suits. That needs to change.”

Other Harvard experts agree. In an opinion piece in The Boston Globe last June, Tomiko Brown-Nagin , dean of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute and the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at HLS, pointed out the Court’s “expansive interpretation of qualified immunity” and called for reform that would “promote accountability.”

“This nation is devoted to freedom, to combating racial discrimination, and to making government accountable to the people,” wrote Brown-Nagin. “Legislators today, like those who passed landmark Civil Rights legislation more than 50 years ago, must take a stand for equal justice under law. Shielding police misconduct offends our fundamental values and cannot be tolerated.”

Share this article

You might like.

School-reform specialist examines mixed legacy of landmark decision, changes in demography, hurdles to equity in opportunity

Research using new method upends narrative on ritual sacrifices, yields discovery on resistance built to colonial-era epidemics

Expert in law, ethics traces history, increasing polarization, steps to bolster democratic process

When should Harvard speak out?

Institutional Voice Working Group provides a roadmap in new report

Had a bad experience meditating? You're not alone.

Altered states of consciousness through yoga, mindfulness more common than thought and mostly beneficial, study finds — though clinicians ill-equipped to help those who struggle

College sees strong yield for students accepted to Class of 2028

Financial aid was a critical factor, dean says

Criminal Justice

In May of 2020, the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police sparked a national conversation on racism in policing. The conversation was long overdue. While Floyd’s death was a wake-up call for many, it was also the latest evidence of systemic, anti-Black racism in the United States criminal justice system.

Since the 1600s, racist stereotypes have permeated American society and shaped its criminal justice system. Some of the first organized “police forces” in the United States were slave patrols in the American South, and as policing evolved, disparities in the treatment of Black and white Americans did not.

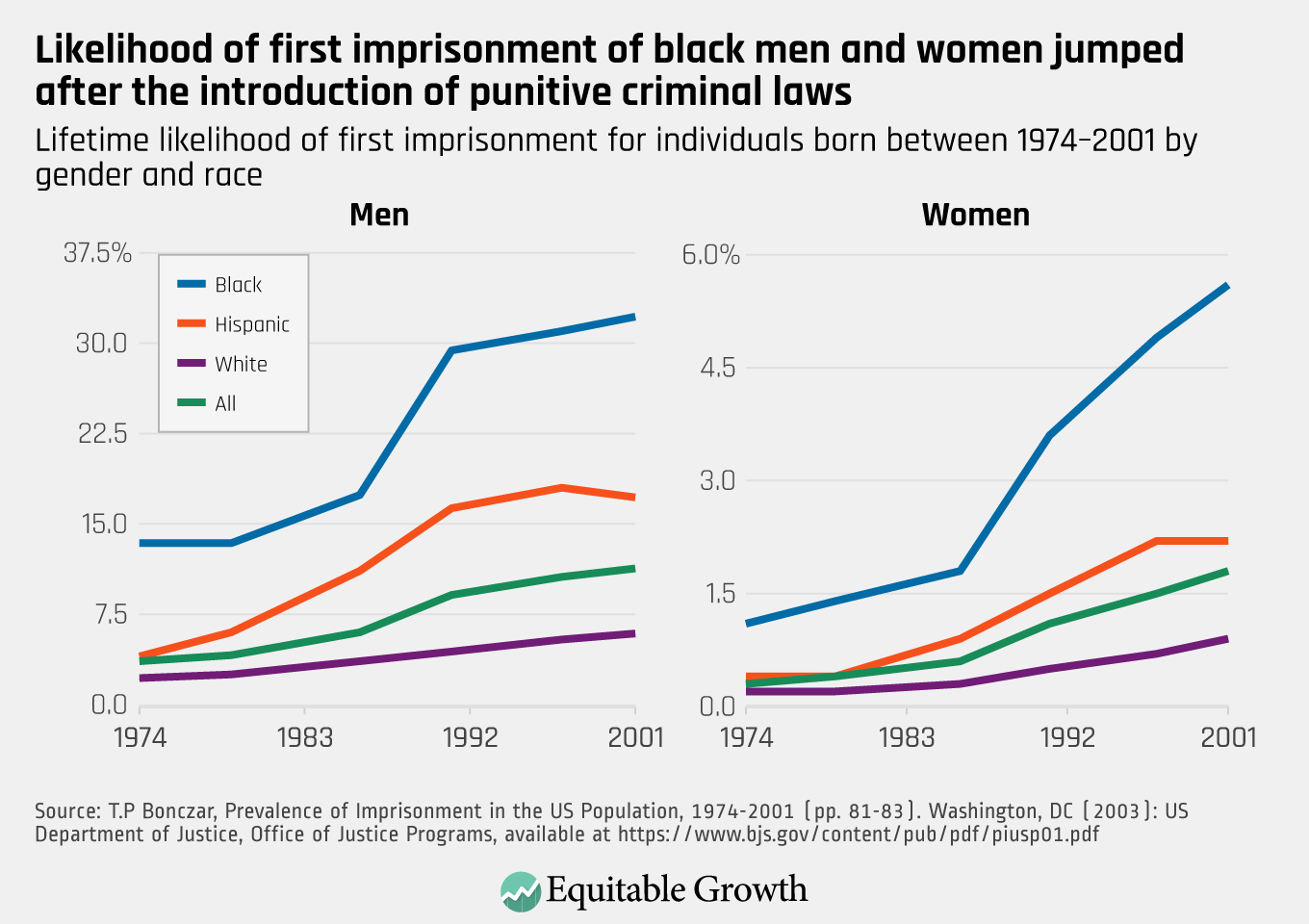

During the 1980s, the federal government’s strategy to counter illegal drug use shifted from treatment and poverty reduction programs to increased incarceration, penalties, and enforcement for drug offenders. The prison population skyrocketed over the next several decades — in 1972 there were only 200,000 people incarcerated in the United States, while there are now more than 2.2 million. The trend of mass incarceration has meant mostly Black incarceration. Black Americans currently represent one-third of the incarcerated population, even though they make up only an eighth of American adults.

Today, Black Americans are more likely to be arrested, convicted, and given harsher sentences than white Americans who commit the same crimes. They receive much greater police scrutiny than those who are not Black — for instance, they use drugs at the same rates as other races and ethnicities but make up nearly 1 in 3 arrests for drug use. And they suffer deadly police violence at a greater rate than non-Black Americans, as the family of George Floyd knows all too well.

Our criminal justice system’s violence and inequality toward Black Americans is fueled by a long history of racism that frames Black people as inherently dangerous criminals. Positively transforming criminal justice in the United States will require confronting this history and implementing policy based in fairness and accountability.

Sources for the information above are cited at the bottom of this page.

Explore a curated sample of Harvard research and resources related to anti-Black racism in criminal justice below.

The great decoupling: the disconnection between criminal offending and experience of arrest across two cohorts.

Contact with the criminal justice system should only occur when one commits a crime. This study reveals how police arrests are increasingly informed by race instead of criminal behavior.

Unfair by Design: The War on Drugs, Race, and the Legitimacy of the Criminal Justice System

Equality before the law is one of the fundamental guarantees citizens expect in a just and fair society. This study explains how the recent trend toward mass incarceration, which has a disproportionate impact on African Americans, undermines this claim to fairness.

The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (HarvardKey Only)

The idea of Black people as innately dangerous and criminal is deeply ingrained in the United States. This book traces the history of this notion and reveals how social scientists and reformers used crime statistics to mask and excuse anti-black racism, violence, and discrimination across the nation.

Punishment without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal (HarvardKey Only)

This book examines inequality in the criminal justice system through an in-depth look at misdemeanors. It reveals a sprawling system that punishes the innocent and disproportionately targets low-income people of color.

Visualizing Police Exposure by Race, Gender, and Age in New York City

This data visualization depicts the disparities in average police stops in New York City from 2004 to 2012. It illustrates that Black men and women are more likely than their peers to be exposed to policing.

Racial Disparities in the Massachusetts Criminal System

People of color are drastically overrepresented in Massachusetts state prisons. This report explores the factors that lead to persistent racial disparities in the Massachusetts criminal system.

American Policing and Protest || Radcliffe Institute

The United States has a long history of police violence against people of color. In this panel, experts discuss the historical roots of policing and ways to create a fair criminal justice system.

PolicyCast: A Historic Crossroads for Systemic Racism and Policing in America

In this podcast Harvard Kennedy School professors Khalil Gibran Muhammad and Erica Chenoweth discuss police brutality, addressing systemic racism in criminal justice, and social movements.

Citations for Section Overview

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. "War on Drugs." Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/war-on-drugs

- Ghandnoosh, Nazgol. 2015. “Black Lives Matter: Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice System.” The Sentencing Project. February 3, 2015. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/black-lives-matter-eliminating-racial-inequity-in-the-criminal-justice-system/.

- Mauer, Marc. 2011. “Addressing Racial Disparities in Incarceration.” The Prison Journal 91 (3): 87S-101S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885511415227

- Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. 2019. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, with a New Preface. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/alma/990120310410203941/catalog.

- Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, and Monica Anderson. 2020. “Amid Protests, Majorities Across Racial and Ethnic Groups Express Support for the Black Lives Matter Movement.” Pew Research Center. June 12, 2020. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/.

- “Racial Justice.” n.d. Equal Justice Initiative. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://eji.org/racial-justice/.

Citations for Page Images

- Interior of Strafford County Jail, New Hampshire | Unidentified Artist. Crime, Prisons: United States. New Hampshire. Dover. Strafford County Jail: New Hampshire State Charitable and Correctional Institutions: Interior - Strafford County Jail., 1902. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/HUAM313572soc/catalog

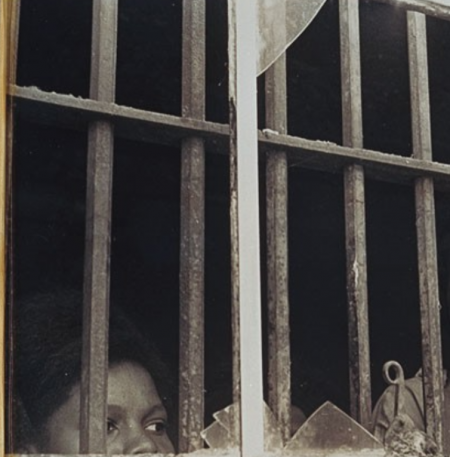

- A young Black girl in a Georgia prison cell, 1963 | Young girls being held in a prison cell at the Leesburg stockade. Part of Barbara Deming Papers. Folder: Alphabetical Correspondence: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC): Photographs, 1963. RLG collection level record MHVW92-A44. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvgroup1003350/urn-3:RAD.SCHL:258877/catalog

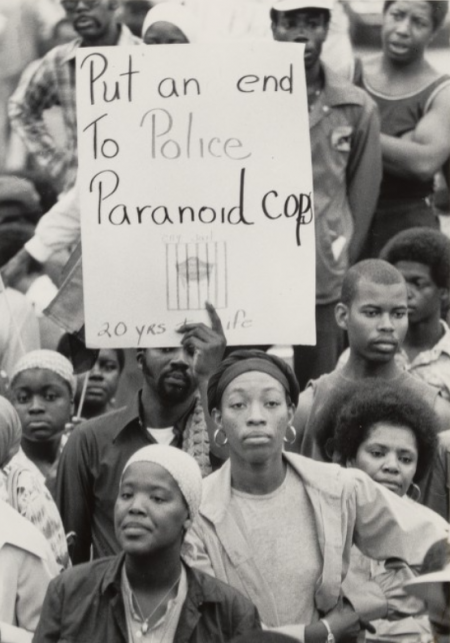

- A New York City demonstration against discriminatory policing, 1976 | Lane, Bettye. Police and Jewish demonstration in Crown Heights , 1976. Part of Bettye Lane Photographs. Folder: Crown Heights demonstration. Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute PC32-136-R8/f12. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/8000905528/catalog

REVIEW CONTENTS

Systemic triage: implicit racial bias in the criminal courtroom, crook county: racism and injustice in america’s largest criminal court, by nicole van cleve, stanford university press, april 2016.

author. Professor of Law, U.C. Irvine School of Law. A.B. Harvard College, J.D. Yale Law School. I wish to thank Rick Banks, Erwin Chemerinsky, Beth Colgan, Sharon Dolovich, Ingrid Eagly, Jonathan Glater, Kaaryn Gustafson, Maximo Langer, Stephen Lee, Sasha Natapoff, Priscilla Ocen, Kevin Lapp, Eric Miller, Richard Re, Christine Scott-Hayward, Carroll Seron, and Bryan Sykes, for valuable feedback. I am also grateful to members of The Yale Law Journal , particularly John Ehrett, Hilary Ledwell, Aaron Levine, Diana Li, and Anna Mohan for their thoughtful comments and editorial suggestions.

Introduction

The criminal justice system is broken. Its policies and policing practices flood courtrooms in urban environments with too many cases to handle given available resources. Many are cases involving indigent individuals of color accused of nonviolent offenses. Scholars like Sasha Natapoff, Jenny Roberts, and Issa Kohler-Hausmann are bringing much needed attention to this serious issue, focusing primarily on misdemeanor adjudications. 1

In a groundbreaking new book, Crook County: Racism and Injustice in America’s Largest Criminal Court , Professor Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve 2 adds an important, novel dimension to this problem. She exposes the deeply flawed operation of the criminal justice system by focusing on how felonies are processed in Cook County, Illinois. Her disturbing ethnography of the Cook County-Chicago criminal courts, the largest unified criminal court system in the United States, 3 is based upon 104 in-depth interviews with judges, prosecutors, public defenders, and private attorneys; her own experiences clerking for both the Cook County District Attorney’s Office and the Cook County Public Defender’s Office; and one thousand hours of felony courtroom observations conducted by 130 court watchers. 4 This mix of perspectives, all of which focus on the court professionals “whose actions define the experience and appearance of justice,” 5 provides a chilling account of how racialized justice is practiced in the Cook County criminal justice system, despite the existence of due process protections and a court record. By “turn[ing] the lens on those in power as they do the marginalizing,” 6 Van Cleve reveals how judges, defense lawyers, and prosecutors transform race-neutral due process protections into the tools of racial punishment.

An important theme of Van Cleve’s book is that the racism practiced in the Cook County courts is not “more enigmatic than the overt racism of the past.” 7 Rather, it is equally “ pervasive, direct, and violent.” 8 To substantiate this point, she exposes deeply problematic and explicitly racist practices that courtroom actors engage in, despite holding seemingly contradictory perspectives. This is one of the more compelling aspects of her book, since it is unusual to encounter such blatant racism on display in this ostensibly colorblind and post-racial era. She explains how these actors “claim their behavior as ‘colorblind’ through coded language, mimic fairness through due process procedures, and rationalize abuse based on morality—all while achieving the experience of segregation and de facto racism.” 9

In this Review, I complicate the theory of racism underlying Van Cleve’s ethnography. Although she never states this explicitly, her theory rests on the assumption that racial bias is visible and conscious, even if expressed in ways that mask its presence. This is demonstrated not only by the examples she uses, but also by the book’s conclusion, which encourages readers to go to court to observe the racist practices she describes and thus shame courtroom actors into changing them.

However, I argue that the problem of racial bias is not so limited. Rather, research from the past several decades reveals that implicit racial biases can influence the behaviors and judgments of even the most consciously egalitarian individuals in ways of which they are unaware and thus unable to control. Additionally, the effects of implicit biases may not be open and obvious. Importantly, then, the absence of discernible racism does not signal the absence of racial bias. Furthermore, since it is not possible to detect the influence of implicit biases on decision making simply through observations and interviews, it is difficult to ferret out and even more difficult to address. Yet, the absence of overtly racist practices does not make the problem of racial bias any less concerning.

Despite the fact that implicit biases operate in the shadows, I argue that there is strong reason to suspect that they will influence the judgments of courtroom actors in Cook County, even after blatantly racist practices disappear. This is because criminal courthouses in jurisdictions across the country, including those in Cook County, are bearing the brunt of “tough on crime” policies and policing practices that disproportionately target enforcement of nonviolent and quality of life offenses in indigent, urban, and minority communities. These policies and practices burden the system with more cases than it has the capacity to handle, resulting in what I refer to as systemic triage.

Triage denotes the process of determining how to allocate scarce resources. In the criminal justice context, scholars typically use the term triage to describe how public defenders attempt to distribute zealous advocacy amongst their clients because crushing caseloads limit their ability to zealously represent them all. 10 In this Review, I build upon my prior work examining public defender triage 11 and use the phrase systemic triage to highlight that all criminal justice system players are impacted by such expansive criminal justice policies and policing practices—not only public defenders, but also the entire cadre of courtroom players, including prosecutors and judges.

I argue that under conditions of systemic triage, implicit racial biases are likely to thrive. First, these criminal justice policies and policing practices will strengthen the already ubiquitous association between subordinated groups and crime by filling courtrooms with overwhelming numbers of people of color. Second, implicit biases flourish in situations where individuals make decisions quickly and on the basis of limited information, exactly the circumstances that exist under systemic triage. In sum, the problem of racial bias will likely persist under conditions of systemic triage, even when it is not accompanied by patently racist behaviors. This problem is even more pernicious because its subtle nature makes it more challenging to expose and correct.

This Review proceeds in three parts. Part I summarizes and analyzes Van Cleve’s ethnographic evidence and conclusions. Importantly, because her account is primarily qualitative, I cannot quantify the frequency with which the problematic practices she identifies occur nor determine how representative her examples are. Part II argues that racism in the criminal justice system is more problematic and pernicious than even Van Cleve’s account suggests. Relying on social science evidence demonstrating the existence of implicit racial biases, I argue that these biases can influence the discretionary decisions, perceptions, and practices of even the most well-meaning individuals in ways that are not readily observable. We should be especially concerned about implicit bias in courtrooms experiencing systemic triage. Finally, Part III offers some solutions to reduce the racialized effects of systemic triage.

i. racism in practice

Van Cleve’s haunting ethnography argues that the existence of “myriad due process protections, legal safeguards, and a courtroom record supposedly holding judges and lawyers accountable” 12 does little to prevent racism from manifesting in the criminal courtrooms of Cook County. Rather, her work reveals how these courts are “transformed from central sites of due process into central sites of racialized punishment.” 13 This punishment takes multiple forms, including treating people of color as criminalseven when they are members of the public appearing in court as jurors, witnesses, or researchers; 14 ridiculing defendants with stereotypically black-sounding names; 15 mocking the speech patterns of black defendants by employing a bastardized version of Ebonics; 16 using lynching language during plea negotiations; 17 and subjecting people of color to degrading and humiliating treatment. 18 Van Cleve argues that courtroom actors also routinely punish defendants of color for attempting to exercise their due process rights.

Evidence from her ethnography reveals that judges, prosecutors, defense lawyers, and sheriff’s deputies engaged in these racialized practices. Even more disturbingly, bad racial actors were not the only ones to treat people of color more harshly. 19 Van Cleve’s ethnography would be slightly less chilling if this were the case because then one could take some comfort knowing that the problems would disappear once all the bad apples were removed from the system. However, Van Cleve’s observations foreclose this simplistic account. Rather, she includes examples of even well-meaning judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers participating in and sustaining this system of racial punishment.

The obvious question is how can actors who “subscribe to the principles of due process, . . . learn ethical standards in law school[,] . . . speak in sympathetic ways about justice, fairness, colorblindness, and even identify bias in the system,” engage in and rationalize their racialized practices? 20 As I discuss in Section I.A, Van Cleve argues that racism in the courts is accomplished through a process of acculturation that begins at the courthouse doors with sheriff’s deputies enforcing racial boundaries. In Section I.B, I present Van Cleve’s assessment of how this racialized culture is maintained through the aggressive policing and harsh treatment of anyone, including courtroom actors, who fails to observe its practices. 21 I also describe Van Cleve’s explanation for how judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys rationalize their racist behaviors by divorcing their perspectives from their practices or “duties” within the system. It is in this way, she argues, that they deflect blame, assuage their guilt, and abdicate responsibility for their role in maintaining the system of racialized punishment. Finally, Section I.C explores some limitations of her powerful and disturbing account.

A. Policing Racial Boundaries

Van Cleve suggests that the “double system of justice” 22 that exists in Cook County begins as defendants, family members, jurors, and witnesses arrive at the courthouse during the morning “rush hour.” She argues that armed sheriff’s deputies, who are the first institutional players the public encounters, begin the process of teaching people of color that they are second-class citizens within this space. 23 To support this point, she shares accounts of court watchers who observed deputies single out people of color for racial mockery and disrespect, making white court watchers acutely aware of their white privilege. 24 She explains that some white court watchers, no matter how they were dressed, reported being asked why they were there and whether they were lawyers or students, while some black court watchers “were mistaken for defendants and treated like criminals.” 25

She also provides anecdotes of sheriff’s deputies continuing to police racial boundaries in the courtrooms by subjecting people of color to hostile and disrespectful treatment for actions as simple—and reasonable—as daring to ask questions. When Van Cleve was a clerk in the prosecutor’s office, she observed an incident that occurred when an elderly black woman attempted to ascertain where her son’s case would be heard. The deputy “tore the woman up with insults” and finally stated to a prosecutor walking into the courtroom, “Tell her: ‘Your son is executed.’” 26 In contrast, Van Cleve also observed the different treatment of an older, gray-haired white woman—wearing a diamond wedding ring and sporting “perfectly coiffed” hair and “manicured and pristine” nails—who crossed the barrier separating the gallery from the courtroom to talk to the court clerk. This woman “was able to finish her question, was answered respectfully, and then the sheriff kindly told her to sit down—acting more like an usher than the abuser who had been barking at the public all afternoon.” 27 These are just a few of the disturbing examples of sheriff’s deputies demeaning people of color while treating the few privileged whites who appeared in the courthouse differently.

Van Cleve’s book does not share a single story in which courtroom actors chastised deputies for the hostility and aggressiveness they heaped on people of color. Instead, she argues that courtroom actors were socialized within the courthouse culture to avoid commenting on racial abuse and racial divides. 28 This is discussed next.

B. Culture and the Race Blind Code

Sheriff’s deputies were not the only courtroom actors to engage in racist behaviors. Van Cleve shares anecdotes of judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers helping to create and sustain a system of racial punishment. Based on her ethnographic evidence, she explains that courtroom professionals learn to code race out of the picture by conflating criminality, morality, and race. This is done primarily by labeling certain defendants as “mopes,” a construct that implies immorality. 29 The term is used by courtroom actors to refer to “someone who is uneducated, incompetent, degenerate, and lazy.” 30 According to her, mope is a synonym for “nigger.” 31

Defendants who were labeled mopes were typically charged with nonviolent offenses, such as possession of drugs and shoplifting, that “imply social dysfunction rather than criminal risk.” 32 Because these defendants were overwhelmingly black and brown, “the moral rubric applied to defendants by courtroom professionals” was racially inscribed. 33 As such, the “‘immorality’ of defendants . . . is both a criminal distinction and a racial one . . . .” 34 Van Cleve argues that by using this colorblind logic, courtroom professionals convinced themselves that the “disdain” they showed to people of color was “not based upon the color of their skin but upon the moral violations they embody.” 35 She concludes that this “race-blind” code “ allow[ed] racism to exist in the courthouse space without professionals being ‘racists.’” 36