- Community and Engagement

- Honors and Awards

- Give Now

This is How Students Can Learn Problem-Solving Skills in Social Studies

A new study led by a researcher from North Carolina State University offers lessons on how social studies teachers could use computational thinking and computer-based resources to analyze primary source data, such as economic information, maps or historical documents. The findings suggest that these approaches advance not only computational thinking, but also student understanding of social studies concepts.

In the journal Theory & Research in Social Education , researchers reported findings from a case study of a high school social studies class called “Measuring the Past” that was offered in a private school. In the project-centered class, students used statistical software to analyze historical and economic data and identify trends. Researchers found students were able to learn problem-solving skills through the series of structured computer analysis projects.

“The purpose of social studies is to enhance student’s ability to participate in a democratic society,” said Meghan Manfra , associate professor of education at NC State. “Our research indicates computational thinking is a fruitful way to engage students in interdisciplinary investigation and develop the skills and habits they need to be successful.”

There is a growing effort to incorporate computational thinking across subjects in K-12 education, Manfra said, to help prepare students for a technology-driven world. Computers have made new techniques possible for historians and social scientists to analyze and interpret digital data, maps and images. Teachers face a potential “firehose” of primary source data they could bring into the classroom, such as the National Archives’ collection of historical letters, speeches, and maps important to American history .

“There are more efforts to integrate computer science across grade levels and subject areas,” Manfra said. “We take the definition of ‘computational thinking’ to be less computer science specific, and much more about a habit of mind. We see it as a structured problem-solving approach.”

In the high school class under study, researchers offered a phrase for the class to use as a guide for how to think about and structure the class projects: analyze the data, look for patterns, and then develop rules or models based on their analysis to solve a problem. They shortened that phrase to “data-patterns-rules.” The projects were also structured as a series, with each students gaining more independence with each project.

“The teacher had a lot of autonomy to develop a curriculum, and the projects were unique,” Manfra said. “Another important aspect of the structure was the students did three rounds of analyzing data, presenting their findings, and developing a model based on what they found. Each time, the teacher got more general in what he was giving the students so they had to flex more of their own thinking.”

In the first project, students analyzed Dollar Street , a website by GapMinder that has a database of photographs of items in homes around the world. Students posed and answered their own questions about the data. For example, one group analyzed whether the number of books in a home related to a family’s income.

In the second project, students tracked prices of labor or products like wool, grain and livestock in England to understand the bubonic plague’s impact on the economy during the Middle Ages.

In the last project, students found their own data to compare social or economic trends during two American wars, such as the War of 1812 and World War I. For example, one group of students compared numbers of draftees and volunteers in two conflicts and related that to the outcome of the war.

From the students’ work, the researchers saw that students were able to learn problem-solving and apply data analysis skills while looking at differences across cultures, the economic effects of historical events and to how political trends can help shape conflicts.

“Based on what we found, this approach not only enhances students’ computational thinking for STEM fields, but it also improves their social studies understanding and knowledge,” Manfra said. “It’s a fruitful approach to teaching and learning.”

From student essays about computational thinking, the researchers saw many students came away with a stronger understanding of the concept. Some students defined it as thinking “based on computer-generated statistics,” while others defined it as analyzing data so a computer can display it, and others said it meant analyzing information in a “computer-like” logical way. In addition, they also saw that students learned skills important in an age of misinformation – they were able to think deeply about potential limitations of the data and the source it came from.

“We found that students were developing data literacy,” Manfra said “They understood databases as a construction, designed to tell a story. We thought that was pretty sophisticated, and that thinking emerged because of what they were experiencing through this project.”

This story originally appeared on the NC State News site.

- Research and Impact

- faculty publications

- Meghan Manfra

- social studies education

More From College of Education News

College of Education Awarded $4 Million in Grant Funding From October 2023 Through March 2024

Distinguished University Professor of Mathematics and Statistics Education Hollylynne Lee Leads Team Named Finalist in 2023-24 Tools Competition

Goodnight Distinguished Professor in Educational Equity Maria Coady, Assistant Teaching Professor Joanna Koch to Examine Dual-language Immersion Programs in Rural North Carolina Settings through Spencer Foundation Grant

- Illinois Online

- Illinois Remote

- TA Resources

- Teaching Consultation

- Teaching Portfolio Program

- Grad Academy for College Teaching

- Faculty Events

- The Art of Teaching

- 2022 Illinois Summer Teaching Institute

- Large Classes

- Leading Discussions

- Laboratory Classes

- Lecture-Based Classes

- Planning a Class Session

- Questioning Strategies

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

- The Case Method

- Community-Based Learning: Service Learning

- Group Learning

- Just-in-Time Teaching

- Creating a Syllabus

- Motivating Students

- Dealing With Cheating

- Discouraging & Detecting Plagiarism

- Diversity & Creating an Inclusive Classroom

- Harassment & Discrimination

- Professional Conduct

- Foundations of Good Teaching

- Student Engagement

- Assessment Strategies

- Course Design

- Student Resources

- Teaching Tips

- Graduate Teacher Certificate

- Certificate in Foundations of Teaching

- Teacher Scholar Certificate

- Certificate in Technology-Enhanced Teaching

- Master Course in Online Teaching (MCOT)

- 2022 Celebration of College Teaching

- 2023 Celebration of College Teaching

- Hybrid Teaching and Learning Certificate

- Classroom Observation Etiquette

- Teaching Philosophy Statement

- Pedagogical Literature Review

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Instructor Stories

- Podcast: Teach Talk Listen Learn

- Universal Design for Learning

Sign-Up to receive Teaching and Learning news and events

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method in which complex real-world problems are used as the vehicle to promote student learning of concepts and principles as opposed to direct presentation of facts and concepts. In addition to course content, PBL can promote the development of critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and communication skills. It can also provide opportunities for working in groups, finding and evaluating research materials, and life-long learning (Duch et al, 2001).

PBL can be incorporated into any learning situation. In the strictest definition of PBL, the approach is used over the entire semester as the primary method of teaching. However, broader definitions and uses range from including PBL in lab and design classes, to using it simply to start a single discussion. PBL can also be used to create assessment items. The main thread connecting these various uses is the real-world problem.

Any subject area can be adapted to PBL with a little creativity. While the core problems will vary among disciplines, there are some characteristics of good PBL problems that transcend fields (Duch, Groh, and Allen, 2001):

- The problem must motivate students to seek out a deeper understanding of concepts.

- The problem should require students to make reasoned decisions and to defend them.

- The problem should incorporate the content objectives in such a way as to connect it to previous courses/knowledge.

- If used for a group project, the problem needs a level of complexity to ensure that the students must work together to solve it.

- If used for a multistage project, the initial steps of the problem should be open-ended and engaging to draw students into the problem.

The problems can come from a variety of sources: newspapers, magazines, journals, books, textbooks, and television/ movies. Some are in such form that they can be used with little editing; however, others need to be rewritten to be of use. The following guidelines from The Power of Problem-Based Learning (Duch et al, 2001) are written for creating PBL problems for a class centered around the method; however, the general ideas can be applied in simpler uses of PBL:

- Choose a central idea, concept, or principle that is always taught in a given course, and then think of a typical end-of-chapter problem, assignment, or homework that is usually assigned to students to help them learn that concept. List the learning objectives that students should meet when they work through the problem.

- Think of a real-world context for the concept under consideration. Develop a storytelling aspect to an end-of-chapter problem, or research an actual case that can be adapted, adding some motivation for students to solve the problem. More complex problems will challenge students to go beyond simple plug-and-chug to solve it. Look at magazines, newspapers, and articles for ideas on the story line. Some PBL practitioners talk to professionals in the field, searching for ideas of realistic applications of the concept being taught.

- What will the first page (or stage) look like? What open-ended questions can be asked? What learning issues will be identified?

- How will the problem be structured?

- How long will the problem be? How many class periods will it take to complete?

- Will students be given information in subsequent pages (or stages) as they work through the problem?

- What resources will the students need?

- What end product will the students produce at the completion of the problem?

- Write a teacher's guide detailing the instructional plans on using the problem in the course. If the course is a medium- to large-size class, a combination of mini-lectures, whole-class discussions, and small group work with regular reporting may be necessary. The teacher's guide can indicate plans or options for cycling through the pages of the problem interspersing the various modes of learning.

- The final step is to identify key resources for students. Students need to learn to identify and utilize learning resources on their own, but it can be helpful if the instructor indicates a few good sources to get them started. Many students will want to limit their research to the Internet, so it will be important to guide them toward the library as well.

The method for distributing a PBL problem falls under three closely related teaching techniques: case studies, role-plays, and simulations. Case studies are presented to students in written form. Role-plays have students improvise scenes based on character descriptions given. Today, simulations often involve computer-based programs. Regardless of which technique is used, the heart of the method remains the same: the real-world problem.

Where can I learn more?

- PBL through the Institute for Transforming Undergraduate Education at the University of Delaware

- Duch, B. J., Groh, S. E, & Allen, D. E. (Eds.). (2001). The power of problem-based learning . Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Grasha, A. F. (1996). Teaching with style: A practical guide to enhancing learning by understanding teaching and learning styles. Pittsburgh: Alliance Publishers.

Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning

249 Armory Building 505 East Armory Avenue Champaign, IL 61820

217 333-1462

Email: [email protected]

Office of the Provost

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

IDEAL Method as a Problem-Based Learning Approach in Social Studies

2021, International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews

The purpose of this research is to investigate the effectiveness, applicability, and instructional impact of using the IDEAL (Identify, Demonstrate, Explore, Act, and Look Back) method as a Problem-Based Learning Approach in Social Studies. The IDEAL method as a Problem-Based Learning is a constructivist, student-centered instructional strategy in which students work collaboratively to solve problems and reflect on their learning experiences to advance or gain new knowledge. The one-group pre-test and post-test experimental design were used to complete the study that was carried out for one week. In all, sixty (60) Grade Ten (10) students at Bagong Nayon II National High School were randomly selected as the participants of the study. The respondents in one group experimental research were taught prescribed by the curriculum of Social Studies using the IDEAL method as a Problem-Based Learning approach. The study shows the IDEAL method as a Problem-Based Learning approach to be a better instructional method for teaching Social Studies. The participants in the one-group experimental research who were taught through the IDEAL method as a PBL performed better as established through the pre-test and posttest scores; and they were also found more motivated towards the Social Studies classes. The data analyses and interpretation suggest that the IDEAL method as a PBL can improve Social Studies teaching and learning practices that lead to the improvement of the students' academic achievement. Hence, it is recommended that teachers use the IDEAL method as a PBL approach in Social Studies classes to enhance the critical and problem solving, communication, collaboration, creativity, and innovation skills of the students.

Related Papers

International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation

The aim of this study is to notice the effectiveness of problem-based learning method applied on students at seventh grade in Junior High School 25 Semarang on Social Science subject. Data was gathered through observation, interview, questioner, documentation and student test result. Responds analysis used quantitative descriptive analysis while test result analysis employed t-test. The result of this study showed that problem-based learning method was profoundly beneficial and enjoyable for students. This was demonstrated by the high score shown in student responds indicators encompassing interest, learning responds, cooperation, responsibility, activeness, understanding, and student knowledge after learning process conducted as well as in student achievement which presented a rise. Average score achieved in factual learning was 74.59 while problem-based learning recorded 86.56. The average deviation from those learnings was-11.969. Thus, due to sig> 0.001, there was a deviation on students' achievement in between factual and problem-based learning.

Al-Ta lim Journal

Ratna Ningsih

The learning outcomes of the Social Sciences study at the Elementary School level in Indonesia in general have not shown maximum results, this is because the social studies field includes subjects that are less attractive to students. This study aims to determine the effect of Problem Based Learning learning method and Conventional learning method as well as the ability to think logically towards learning outcomes in Social Sciences. This research was conducted on class VI students of the State Ibtidaiyah Madrasah in Ciputat, with a total of 60 students. This study uses treatment by level 2 x 2. The data analysis technique is the analysis of two-way variance (ANAVA). The results of the study showed that: (1) Student learning outcomes in social studies subjects taught using PBL learning method were higher than students taught using conventional method, (2) for students who have high logical thinking skills, the learning outcomes of students taught using the Problem Based Learning met...

Proceedings of the First Indonesian Communication Forum of Teacher Training and Education Faculty Leaders International Conference on Education 2017 (ICE 2017)

Yemima Natalia

PrimaryEdu - Journal of Primary Education

Rizki Pebriana

The main problem of this study is the lack of ability to think kriis Elementary School fifth grade students in the learning of Social Sciences. This study uses a quantitative approach with quasi-experimental methods. The study population was the fifth-grade elementary school students in District Ciparay Bandung regency. The sample consisted of 51 students divided into 25 students in the class IV-A as an experimental group and 26 students in the class IV-B as the control group. Instruments used comprises a written test regarding social issues. Quantitative analysis is performed against the average pretest and post test critical thinking skills by using the t-test and Mann Whitney test. The results showed that the differences are critical thinking skills in students using problem-based learning model at initial measurement (pre-test) and the final measurement (post-test). encourage the student can solve his problems with critical thinking, there are no differences in the ability of cr...

Open Access Publishing Group

Based on the subjects of social sciences, the students are directed, guided, and helped to become Indonesian citizens and to be effective world citizens. To develop these capabilities, it requires the necessary competence of teachers in delivering learning. Skills teachers in planning lessons need to take into account and relate to the methods that will be used in learning. Problem solving method is a way of solving problems based on data or information which is accurate to obtain a conclusion. This research was implemented to improve the process by applying certain methods. As a matter of fact, the procedure is done through action planning, action, observation and reflection. The research cycle lasted a few times until the learning objectives achieved the social knowledge material, in this case, the subject of Natural Resources. The results showed, in the first cycle, the writer got the average value of the subject of the Natural Resources subject of 38 students at 5.63, at the second cycle was 6.92, while the third cycle was 7.53. There was an improvement of results from the first cycle to the second cycle was 23%, while, the second cycle to the third cycle of 9%. Overall, during the treatment performed by three cycles, there was an increase of learning outcomes through method of solving the problem by 34%.

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science

Dwi Astuti Wahyu Nurhayati

The background underlying this study is due to the implementing of instruction methods that have not demonstrated thinking skill. The discussion of Social Studies material is also very broad, demanding students to possess thinking skill (critical thinking and creative thinking). Thinking skill is crucial to deal with problems in doing tasks in order to improve learning outcomes, or even to solve problems that exist in either students themselves or in their environment. In an effort to improve learning outcomes, teachers can adopt thinking skill-based inquiry learning method. The objective of this study is to (1)examine learning outcomes of Social Studies between those who use thinking skill-based inquiry learning method and those who adopt conventional method; (2) investigate the significant effect of using thinking skill-based inquiry learning method; and (3) analyzing the effect size of thinking skill-based inquiry learning method on the Social Studies learning outcomes. This article exploited a perceptible or measurable way, notably an apparent- empirical construction, in which thinking skill-based inquiry learning method was the independent variable and learning outcome was the dependent variable. The instruments used were test and documentation. This study used a saturated sampling technique. The population in this study was all grade 8 students. This study engaged 2 classes as the sample, namely class VIII-H as the control class consisting of 38 students, and class VIII-I as the experimental class comprising of 34 pupils. The statistics were analyzed using the t-test, and the aftermath capacity was calculated by using Cohen's formula. The outcome of this finding determined as follows(1) the learning outcomes of Social Studies of students who used thinking skill-based inquiry learning method was 80.91 on average, better than the students who used the conventional learning method; (2) it displayed that a significant reaction of reasoning competency-based question and reasoning instruction design or approach on the pupils learning reaction with the value of tcount = 6.57, and ttable at the 5% significance level was 1.65, indicating that the value of tcount > ttable, (3) the effect size of thinking skill-based inquiry learning method on the students' learning outcome was up to 91.9%, which was classified as the high percentage.

Nur Muhammad

This study aims to determine the improvement of the quality of learning social studies using a scientific approach and build a model of scientific approach to improve the quality of learning of social studies. To get a clear picture of the model of scientific approach to teaching social studies in Labschool Junior High School Jakarta, the researchers used a qualitative approach within a period of four months in February to May 2015. The results of this study indicate that the model of scientific approach can improve the quality of teaching social studies. Scientific approach emphasizes students to seek and find their own knowledge is at the core of learning social studies. As revealed by Swan, et. al., which is Central to a rich experience of social studies is the capability for developing questions that can frame and advance an inquiry. Those questions come in two forms: compelling and supporting questions. Based on the above explanation, we can understand that the center of the de...

International Journal of Advanced Research (IJAR)

IJAR Indexing

This study aims to improve students\' ability to express their opinions on PKn (Civic Education) graphic design majors by applying the Problem Based Learning (PBL) model through discussion techniques to form a positive student social attitude as a provision to socialize in the community. This study uses a type of classroom action research (CAR) focused on classroom situations commonly known as classroom action research. PTK is an action research aimed at improving the quality of learning in the classroom. The focus of PTK on students and the teaching and learning processes that occur in the classroom. The main purpose of PTK is to solve problems that occur in the classroom and improve the real activities of lecturers in the development of their profession. Based on the results of research and discussion it can be concluded that the Application of Problem Based Learning models can improve the ability. that is, with indicators formulating problems, being able to ask and answer questions, having critical and logical thinking in analyzing problems, then being able to find relevant information and be able to deduce the results of the presentation.

JMIE (Journal of Madrasah Ibtidaiyah Education)

Faridillah Fahmi Nurfurqon

This local wisdom-based learning is expected to be able to bridge students to understand and know the customs, culture, values and norms that apply in the region or ethnic group. This study aims to explore the values of local wisdom in elementary social studies learning using a Problem based learning model. The research design uses a descriptive research model. The data collected in the form of quantitative data through formative tests, analysis of observation sheets, and document analysis. The number of research subjects consisted of 35 students divided. This research was conducted in a public school located in Cimahi City. The results of the study indicate that the implementation of the PBL model to explore the values of local wisdom in elementary social studies learning can be selected and used as one of the appropriate methods or innovations to be applied by teachers in the online learning process.

RELATED PAPERS

Food Chemistry

Daniel Demeyer

Jairo Preciado

Critical Care

Federico Bilotta

Dermatologic Therapy

Arturo Bonometti

Advances in Cancer Research

Balaji Krishnamachary

Comparative Parasitology

Sherman Hendrix

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery

Mehmet Bayramiçli

Edward Parra

Imam Hossein University

Interdisciplinary studies of Islamic revolution civilization

Katerin Torres

jesus flores

Journal of Mammalogy

Mauro Nicolás Tammone

Molecular Therapy

john bringas

Louis Nwajiaku

Pepatudzu : Media Pendidikan dan Sosial Kemasyarakatan

Ahmad Yakin

Saša Ćirković

Ecología Aplicada

Daniel Ballarín

Şevket Ercan Kızılay

Journal of Oceanography

Ehsan Rastgoftar

Suzana Barbosa Luciana Mielniczuk Jornalismo E Tecnologias Moveis Livros Labcom

Barbosa Suzana

麦考瑞大学毕业证文凭办理成绩单修改 办理澳洲MQ文凭学位证书学历认证

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

10 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Sayed Fayaz Ahmad, Heesup Han, … Antonio Ariza-Montes

Anger is eliminated with the disposal of a paper written because of provocation

Yuta Kanaya & Nobuyuki Kawai

Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research

Lisa Messeri & M. J. Crockett

Introduction

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

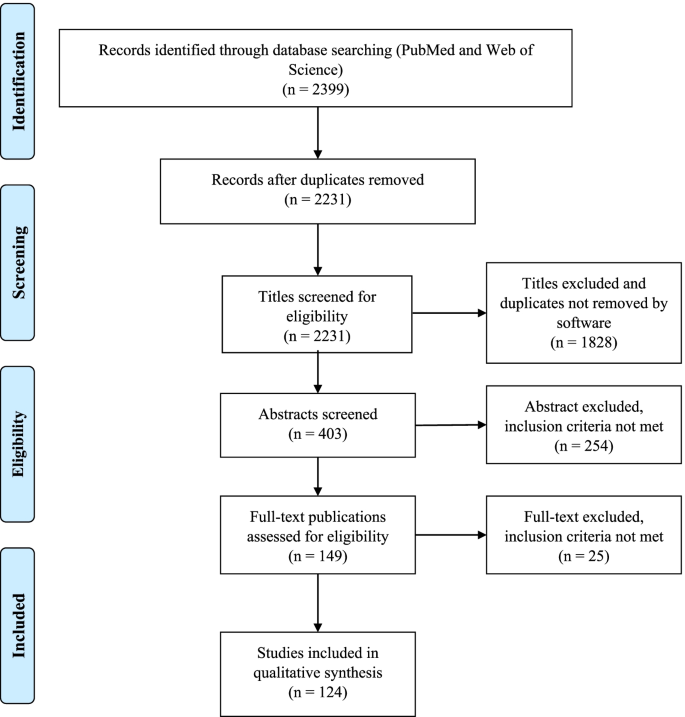

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

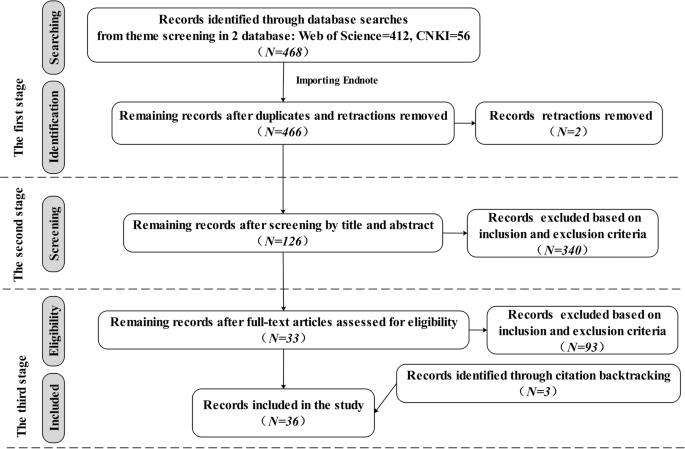

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

Publication bias test

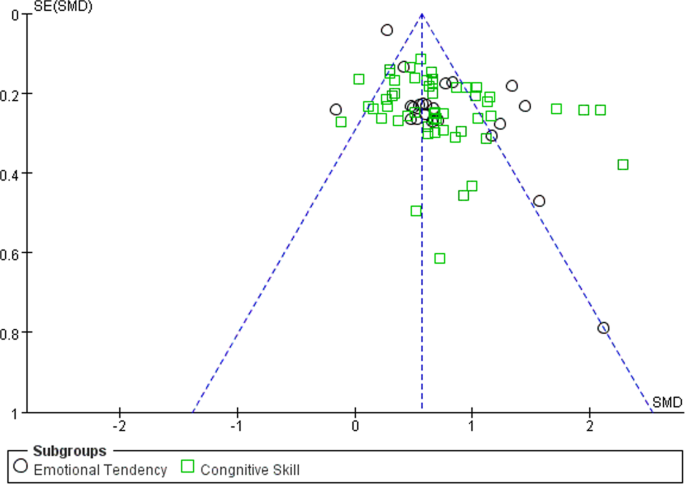

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

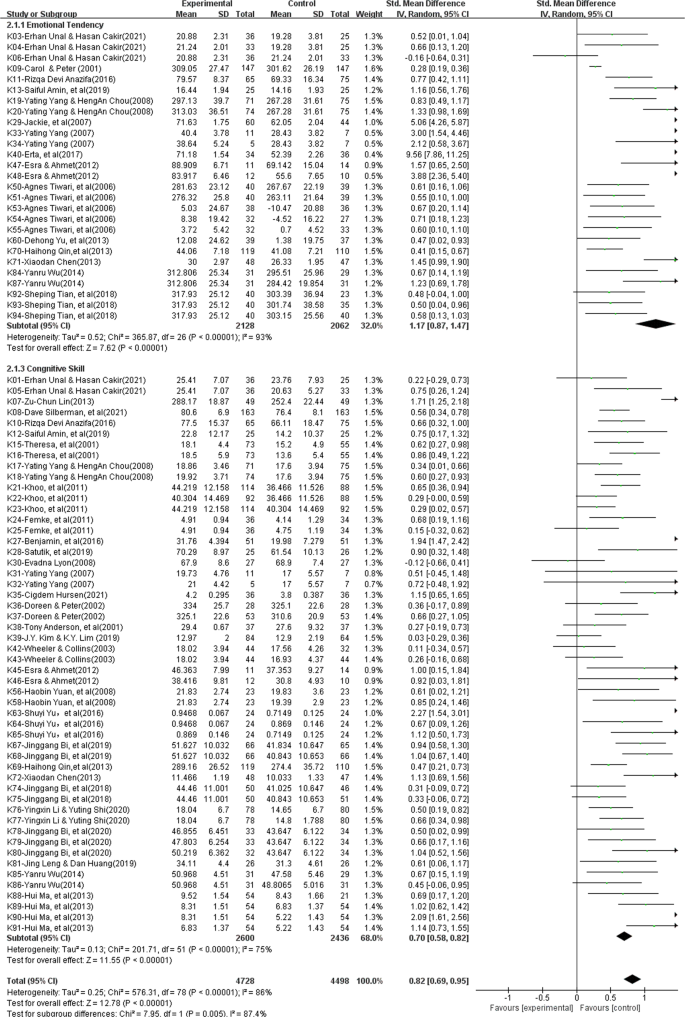

The analysis of the overall effect size

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.

Various group sizes influenced critical thinking positively, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05). Critical thinking showed a general declining trend with increasing group size. The overall effect size of 2–3 people in this situation was the biggest (ES = 0.99, P < 0.01), and when the group size was greater than 7 people, the improvement in critical thinking was at the lower-middle level (ES < 0.5, P < 0.01). These results show that the impact on critical thinking is positively connected with group size, and as group size grows, so does the overall impact.

Various measuring tools influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05). In this situation, the self-adapting measurement tools obtained an upper-medium level of effect (ES = 0.78), whereas the complete effect size of the standardized measurement tools was the largest, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.84, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the beneficial influence of the measuring tool on cultivating critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Different subject areas had a greater impact on critical thinking, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). Mathematics had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 1.68, P < 0.01), followed by science (ES = 1.25, P < 0.01) and medical science (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Programming technology was the least effective (ES = 0.39, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to education (ES = 0.72, P < 0.01) and other fields (such as language, art, and social sciences) (ES = 0.58, P < 0.01). These results suggest that scientific fields (e.g., mathematics, science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

According to this meta-analysis, using collaborative problem-solving as an intervention strategy in critical thinking teaching has a considerable amount of impact on cultivating learners’ critical thinking as a whole and has a favorable promotional effect on the two dimensions of critical thinking. According to certain studies, collaborative problem solving, the most frequently used critical thinking teaching strategy in curriculum instruction can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking (e.g., Liang et al., 2017 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Cindy, 2004 ). This meta-analysis provides convergent data support for the above research views. Thus, the findings of this meta-analysis not only effectively address the first research query regarding the overall effect of cultivating critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills) utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving, but also enhance our confidence in cultivating critical thinking by using collaborative problem-solving intervention approach in the context of classroom teaching.

Furthermore, the associated improvements in attitudinal tendency are much stronger, but the corresponding improvements in cognitive skill are only marginally better. According to certain studies, cognitive skill differs from the attitudinal tendency in classroom instruction; the cultivation and development of the former as a key ability is a process of gradual accumulation, while the latter as an attitude is affected by the context of the teaching situation (e.g., a novel and exciting teaching approach, challenging and rewarding tasks) (Halpern, 2001 ; Wei and Hong, 2022 ). Collaborative problem-solving as a teaching approach is exciting and interesting, as well as rewarding and challenging; because it takes the learners as the focus and examines problems with poor structure in real situations, and it can inspire students to fully realize their potential for problem-solving, which will significantly improve their attitudinal tendency toward solving problems (Liu et al., 2020 ). Similar to how collaborative problem-solving influences attitudinal tendency, attitudinal tendency impacts cognitive skill when attempting to solve a problem (Liu et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ), and stronger attitudinal tendencies are associated with improved learning achievement and cognitive ability in students (Sison, 2008 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ). It can be seen that the two specific dimensions of critical thinking as well as critical thinking as a whole are affected by collaborative problem-solving, and this study illuminates the nuanced links between cognitive skills and attitudinal tendencies with regard to these two dimensions of critical thinking. To fully develop students’ capacity for critical thinking, future empirical research should pay closer attention to cognitive skills.

The moderating effects of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

In order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking, exploring possible moderating effects that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis. The findings show that the moderating factors, such as the teaching type, learning stage, group size, learning scaffold, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, could all support the cultivation of collaborative problem-solving in critical thinking. Among them, the effect size differences between the learning stage and measuring tool are not significant, which does not explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

In terms of the learning stage, various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively without significant intergroup differences, indicating that we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking.

Although high education accounts for 70.89% of all empirical studies performed by researchers, high school may be the appropriate learning stage to foster students’ critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving since it has the largest overall effect size. This phenomenon may be related to student’s cognitive development, which needs to be further studied in follow-up research.

With regard to teaching type, mixed course teaching may be the best teaching method to cultivate students’ critical thinking. Relevant studies have shown that in the actual teaching process if students are trained in thinking methods alone, the methods they learn are isolated and divorced from subject knowledge, which is not conducive to their transfer of thinking methods; therefore, if students’ thinking is trained only in subject teaching without systematic method training, it is challenging to apply to real-world circumstances (Ruggiero, 2012 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Teaching critical thinking as mixed course teaching in parallel to other subject teachings can achieve the best effect on learners’ critical thinking, and explicit critical thinking instruction is more effective than less explicit critical thinking instruction (Bensley and Spero, 2014 ).

In terms of the intervention duration, with longer intervention times, the overall effect size shows an upward tendency. Thus, the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated. Critical thinking, as a key competency for students in the 21st century, is difficult to get a meaningful improvement in a brief intervention duration. Instead, it could be developed over a lengthy period of time through consistent teaching and the progressive accumulation of knowledge (Halpern, 2001 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Therefore, future empirical studies ought to take these restrictions into account throughout a longer period of critical thinking instruction.

With regard to group size, a group size of 2–3 persons has the highest effect size, and the comprehensive effect size decreases with increasing group size in general. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a group composed of two to four members is most appropriate for collaborative learning (Schellens and Valcke, 2006 ). However, the meta-analysis results also indicate that once the group size exceeds 7 people, small groups cannot produce better interaction and performance than large groups. This may be because the learning scaffolds of technique support, resource support, and teacher support improve the frequency and effectiveness of interaction among group members, and a collaborative group with more members may increase the diversity of views, which is helpful to cultivate critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

With regard to the learning scaffold, the three different kinds of learning scaffolds can all enhance critical thinking. Among them, the teacher-supported learning scaffold has the largest overall effect size, demonstrating the interdependence of effective learning scaffolds and collaborative problem-solving. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a successful strategy is to encourage learners to collaborate, come up with solutions, and develop critical thinking skills by using learning scaffolds (Reiser, 2004 ; Xu et al., 2022 ); learning scaffolds can lower task complexity and unpleasant feelings while also enticing students to engage in learning activities (Wood et al., 2006 ); learning scaffolds are designed to assist students in using learning approaches more successfully to adapt the collaborative problem-solving process, and the teacher-supported learning scaffolds have the greatest influence on critical thinking in this process because they are more targeted, informative, and timely (Xu et al., 2022 ).

With respect to the measuring tool, despite the fact that standardized measurement tools (such as the WGCTA, CCTT, and CCTST) have been acknowledged as trustworthy and effective by worldwide experts, only 54.43% of the research included in this meta-analysis adopted them for assessment, and the results indicated no intergroup differences. These results suggest that not all teaching circumstances are appropriate for measuring critical thinking using standardized measurement tools. “The measuring tools for measuring thinking ability have limits in assessing learners in educational situations and should be adapted appropriately to accurately assess the changes in learners’ critical thinking.”, according to Simpson and Courtney ( 2002 , p. 91). As a result, in order to more fully and precisely gauge how learners’ critical thinking has evolved, we must properly modify standardized measuring tools based on collaborative problem-solving learning contexts.

With regard to the subject area, the comprehensive effect size of science departments (e.g., mathematics, science, medical science) is larger than that of language arts and social sciences. Some recent international education reforms have noted that critical thinking is a basic part of scientific literacy. Students with scientific literacy can prove the rationality of their judgment according to accurate evidence and reasonable standards when they face challenges or poorly structured problems (Kyndt et al., 2013 ), which makes critical thinking crucial for developing scientific understanding and applying this understanding to practical problem solving for problems related to science, technology, and society (Yore et al., 2007 ).

Suggestions for critical thinking teaching

Other than those stated in the discussion above, the following suggestions are offered for critical thinking instruction utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

First, teachers should put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, to design real problems based on collaborative situations. This meta-analysis provides evidence to support the view that collaborative problem-solving has a strong synergistic effect on promoting students’ critical thinking. Asking questions about real situations and allowing learners to take part in critical discussions on real problems during class instruction are key ways to teach critical thinking rather than simply reading speculative articles without practice (Mulnix, 2012 ). Furthermore, the improvement of students’ critical thinking is realized through cognitive conflict with other learners in the problem situation (Yang et al., 2008 ). Consequently, it is essential for teachers to put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, and design real problems and encourage students to discuss, negotiate, and argue based on collaborative problem-solving situations.

Second, teachers should design and implement mixed courses to cultivate learners’ critical thinking, utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving. Critical thinking can be taught through curriculum instruction (Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), with the goal of cultivating learners’ critical thinking for flexible transfer and application in real problem-solving situations. This meta-analysis shows that mixed course teaching has a highly substantial impact on the cultivation and promotion of learners’ critical thinking. Therefore, teachers should design and implement mixed course teaching with real collaborative problem-solving situations in combination with the knowledge content of specific disciplines in conventional teaching, teach methods and strategies of critical thinking based on poorly structured problems to help students master critical thinking, and provide practical activities in which students can interact with each other to develop knowledge construction and critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Third, teachers should be more trained in critical thinking, particularly preservice teachers, and they also should be conscious of the ways in which teachers’ support for learning scaffolds can promote critical thinking. The learning scaffold supported by teachers had the greatest impact on learners’ critical thinking, in addition to being more directive, targeted, and timely (Wood et al., 2006 ). Critical thinking can only be effectively taught when teachers recognize the significance of critical thinking for students’ growth and use the proper approaches while designing instructional activities (Forawi, 2016 ). Therefore, with the intention of enabling teachers to create learning scaffolds to cultivate learners’ critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem solving, it is essential to concentrate on the teacher-supported learning scaffolds and enhance the instruction for teaching critical thinking to teachers, especially preservice teachers.

Implications and limitations

There are certain limitations in this meta-analysis, but future research can correct them. First, the search languages were restricted to English and Chinese, so it is possible that pertinent studies that were written in other languages were overlooked, resulting in an inadequate number of articles for review. Second, these data provided by the included studies are partially missing, such as whether teachers were trained in the theory and practice of critical thinking, the average age and gender of learners, and the differences in critical thinking among learners of various ages and genders. Third, as is typical for review articles, more studies were released while this meta-analysis was being done; therefore, it had a time limit. With the development of relevant research, future studies focusing on these issues are highly relevant and needed.

Conclusions

The subject of the magnitude of collaborative problem-solving’s impact on fostering students’ critical thinking, which received scant attention from other studies, was successfully addressed by this study. The question of the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking was addressed in this study, which addressed a topic that had gotten little attention in earlier research. The following conclusions can be made:

Regarding the results obtained, collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster learners’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]). With respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving can significantly and effectively improve students’ attitudinal tendency, and the comprehensive effect is significant (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

As demonstrated by both the results and the discussion, there are varying degrees of beneficial effects on students’ critical thinking from all seven moderating factors, which were found across 36 studies. In this context, the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have a positive impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. Since the learning stage (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05) and measuring tools (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05) did not demonstrate any significant intergroup differences, we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included within the article and its supplementary information files, and the supplementary information files are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IPFJO6 .

Bensley DA, Spero RA (2014) Improving critical thinking skills and meta-cognitive monitoring through direct infusion. Think Skills Creat 12:55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2014.02.001

Article Google Scholar

Castle A (2009) Defining and assessing critical thinking skills for student radiographers. Radiography 15(1):70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2007.10.007

Chen XD (2013) An empirical study on the influence of PBL teaching model on critical thinking ability of non-English majors. J PLA Foreign Lang College 36 (04):68–72

Google Scholar

Cohen A (1992) Antecedents of organizational commitment across occupational groups: a meta-analysis. J Organ Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130602

Cooper H (2010) Research synthesis and meta-analysis: a step-by-step approach, 4th edn. Sage, London, England

Cindy HS (2004) Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educ Psychol Rev 51(1):31–39

Duch BJ, Gron SD, Allen DE (2001) The power of problem-based learning: a practical “how to” for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline. Stylus Educ Sci 2:190–198

Ennis RH (1989) Critical thinking and subject specificity: clarification and needed research. Educ Res 18(3):4–10. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x018003004

Facione PA (1990) Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research findings and recommendations. Eric document reproduction service. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed315423

Facione PA, Facione NC (1992) The California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI) and the CCTDI test manual. California Academic Press, Millbrae, CA

Forawi SA (2016) Standard-based science education and critical thinking. Think Skills Creat 20:52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.02.005

Halpern DF (2001) Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. J Gen Educ 50(4):270–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/27797889

Hu WP, Liu J (2015) Cultivation of pupils’ thinking ability: a five-year follow-up study. Psychol Behav Res 13(05):648–654. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2015.05.010

Huber K (2016) Does college teach critical thinking? A meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 86(2):431–468. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315605917

Kek MYCA, Huijser H (2011) The power of problem-based learning in developing critical thinking skills: preparing students for tomorrow’s digital futures in today’s classrooms. High Educ Res Dev 30(3):329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.501074

Kuncel NR (2011) Measurement and meaning of critical thinking (Research report for the NRC 21st Century Skills Workshop). National Research Council, Washington, DC

Kyndt E, Raes E, Lismont B, Timmers F, Cascallar E, Dochy F (2013) A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educ Res Rev 10(2):133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.02.002

Leng J, Lu XX (2020) Is critical thinking really teachable?—A meta-analysis based on 79 experimental or quasi experimental studies. Open Educ Res 26(06):110–118. https://doi.org/10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2020.06.011

Liang YZ, Zhu K, Zhao CL (2017) An empirical study on the depth of interaction promoted by collaborative problem solving learning activities. J E-educ Res 38(10):87–92. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2017.10.014

Lipsey M, Wilson D (2001) Practical meta-analysis. International Educational and Professional, London, pp. 92–160

Liu Z, Wu W, Jiang Q (2020) A study on the influence of problem based learning on college students’ critical thinking-based on a meta-analysis of 31 studies. Explor High Educ 03:43–49

Morris SB (2008) Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organ Res Methods 11(2):364–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106291059

Article ADS Google Scholar

Mulnix JW (2012) Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educ Philos Theory 44(5):464–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2010.00673.x

Naber J, Wyatt TH (2014) The effect of reflective writing interventions on the critical thinking skills and dispositions of baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 34(1):67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.002

National Research Council (2012) Education for life and work: developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Niu L, Behar HLS, Garvan CW (2013) Do instructional interventions influence college students’ critical thinking skills? A meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 9(12):114–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.12.002

Peng ZM, Deng L (2017) Towards the core of education reform: cultivating critical thinking skills as the core of skills in the 21st century. Res Educ Dev 24:57–63. https://doi.org/10.14121/j.cnki.1008-3855.2017.24.011

Reiser BJ (2004) Scaffolding complex learning: the mechanisms of structuring and problematizing student work. J Learn Sci 13(3):273–304. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1303_2

Ruggiero VR (2012) The art of thinking: a guide to critical and creative thought, 4th edn. Harper Collins College Publishers, New York

Schellens T, Valcke M (2006) Fostering knowledge construction in university students through asynchronous discussion groups. Comput Educ 46(4):349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2004.07.010

Sendag S, Odabasi HF (2009) Effects of an online problem based learning course on content knowledge acquisition and critical thinking skills. Comput Educ 53(1):132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.01.008

Sison R (2008) Investigating Pair Programming in a Software Engineering Course in an Asian Setting. 2008 15th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference, pp. 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1109/APSEC.2008.61

Simpson E, Courtney M (2002) Critical thinking in nursing education: literature review. Mary Courtney 8(2):89–98