- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.1: Arguments Against Abortion

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 35918

- Nathan Nobis & Kristina Grob

- Morehouse College & University of South Carolina Sumter via Open Philosophy Press

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

We will begin with arguments for the conclusion that abortion is generally wrong , perhaps nearly always wrong . These can be seen as reasons to believe fetuses have the “right to life” or are otherwise seriously wrong to kill.

5.1.1 Fetuses are human

First, there is the claim that fetuses are “human” and so abortion is wrong. People sometimes debate whether fetuses are human , but fetuses found in (human) women clearly are biologically human : they aren’t cats or dogs. And so we have this argument, with a clearly true first premise:

Fetuses are biologically human.

All things that are biologically human are wrong to kill.

Therefore, fetuses are wrong to kill.

The second premise, however, is false, as easy counterexamples show. Consider some random living biologically human cells or tissues in a petri dish. It wouldn’t be wrong at all to wash those cells or tissues down the drain, killing them; scratching yourself or shaving might kill some biologically human skin cells, but that’s not wrong; a tumor might be biologically human, but not wrong to kill. So just because something is biologically human, that does not at all mean it’s wrong to kill that thing. We saw this same point about what’s merely biologically alive.

This suggests a deficiency in some common understandings of the important idea of “human rights.” “Human rights” are sometimes described as rights someone has just because they are human or simply in virtue of being human .

But the human cells in the petri dish above don’t have “human rights” and a human heart wouldn’t have “human rights” either. Many examples would make it clear that merely being biologically human doesn’t give something human rights. And many human rights advocates do not think that abortion is wrong, despite recognizing that (human) fetuses are biologically human.

The problem about what is often said about human rights is that people often do not think about what makes human beings have rights or why we have them, when we have them. The common explanation, that we have (human) rights just because we are (biologically) human , is incorrect, as the above discussion makes clear. This misunderstanding of the basis or foundation of human rights is problematic because it leads to a widespread, misplaced fixation on whether fetuses are merely biologically “human” and the mistaken thought that if they are, they have “human rights.” To address this problem, we need to identify better, more fundamental, explanations why we have rights, or why killing us is generally wrong, and see how those explanations might apply to fetuses, as we are doing here.

It might be that when people appeal to the importance and value of being “human,” the concern isn’t our biology itself, but the psychological characteristics that many human beings have: consciousness, awareness, feelings and so on. We will discuss this different meaning of “human” below. This meaning of “human” might be better expressed as conscious being , or “person,” or human person. This might be what people have in mind when they argue that fetuses aren’t even “human.”

Human rights are vitally important, and we would do better if we spoke in terms of “conscious-being rights” or “person-rights,” not “human rights.” This more accurate and informed understanding and terminology would help address human rights issues in general, and help us better think through ethical questions about biologically human embryos and fetuses.

5.1.2 Fetuses are human beings

Some respond to the arguments above—against the significance of being merely biologically human—by observing that fetuses aren’t just mere human cells, but are organized in ways that make them beings or organisms . (A kidney is part of a “being,” but the “being” is the whole organism.) That suggests this argument:

Fetuses are human beings or organisms .

All human beings or organisms are wrong to kill.

Therefore, fetuses are wrong to kill, so abortion is wrong.

The first premise is true: fetuses are dependent beings, but dependent beings are still beings.

The second premise, however, is the challenge, in terms of providing good reasons to accept it. Clearly many human beings or organisms are wrong to kill, or wrong to kill unless there’s a good reason that would justify that killing, e.g., self-defense. (This is often described by philosophers as us being prima facie wrong to kill, in contrast to absolutely or necessarily wrong to kill.) Why is this though? What makes us wrong to kill? And do these answers suggest that all human beings or organisms are wrong to kill?

Above it was argued that we are wrong to kill because we are conscious and feeling: we are aware of the world, have feelings and our perspectives can go better or worse for us —we can be harmed— and that’s what makes killing us wrong. It may also sometimes be not wrong to let us die, and perhaps even kill us, if we come to completely and permanently lacking consciousness, say from major brain damage or a coma, since we can’t be harmed by death anymore: we might even be described as dead in the sense of being “brain dead.” 10

So, on this explanation, human beings are wrong to kill, when they are wrong to kill, not because they are human beings (a circular explanation), but because we have psychological, mental or emotional characteristics like these. This explains why we have rights in a simple, common-sense way: it also simply explains why rocks, microorganisms and plants don’t have rights. The challenge then is explaining why fetuses that have never been conscious or had any feeling or awareness would be wrong to kill. How then can the second premise above, general to all human organisms, be supported, especially when applied to early fetuses?

One common attempt is to argue that early fetuses are wrong to kill because there is continuous development from fetuses to us, and since we are wrong to kill now , fetuses are also wrong to kill, since we’ve been the “same being” all along. 11 But this can’t be good reasoning, since we have many physical, cognitive, emotional and moral characteristics now that we lacked as fetuses (and as children). So even if we are the “same being” over time, even if we were once early fetuses, that doesn’t show that fetuses have the moral rights that babies, children and adults have: we, our bodies and our rights sometimes change.

A second attempt proposes that rights are essential to human organisms: they have them whenever they exist. This perspective sees having rights, or the characteristics that make someone have rights, as essential to living human organisms. The claim is that “having rights” is an essential property of human beings or organisms, and so whenever there’s a living human organism, there’s someone with rights, even if that organism totally lacks consciousness, like an early fetus. (In contrast, the proposal we advocate for about what makes us have rights understands rights as “accidental” to our bodies but “essential” to our minds or awareness, since our bodies haven’t always “contained” a conscious being, so to speak.)

Such a view supports the premise above; maybe it just is that premise above. But why believe that rights are essential to human organisms? Some argue this is because of what “kind” of beings we are, which is often presumed to be “rational beings.” The reasoning seems to be this: first, that rights come from being a rational being: this is part of our “nature.” Second, that all human organisms, including fetuses, are the “kind” of being that is a “rational being,” so every being of the “kind” rational being has rights. 12

In response, this explanation might seem question-begging: it might amount to just asserting that all human beings have rights. This explanation is, at least, abstract. It seems to involve some categorization and a claim that everyone who is in a certain category has some of the same moral characteristics that others in that category have, but because of a characteristic (actual rationality) that only these others have: so, these others profoundly define what everyone else is . If this makes sense, why not also categorize us all as not rational beings , if we are the same kind of beings as fetuses that are actually not rational?

This explanation might seem to involve thinking that rights somehow “trickle down” from later rationality to our embryonic origins, and so what we have later we also have earlier , because we are the same being or the same “kind” of being. But this idea is, in general, doubtful: we are now responsible beings, in part because we are rational beings, but fetuses aren’t responsible for anything. And we are now able to engage in moral reasoning since we are rational beings, but fetuses don’t have the “rights” that uniquely depend on moral reasoning abilities. So that an individual is a member of some general group or kind doesn’t tell us much about their rights: that depends on the actual details about that individual, beyond their being members of a group or kind.

To make this more concrete, return to the permanently comatose individuals mentioned above: are we the same kind of beings, of the same “essence,” as these human beings? If so, then it seems that some human beings can be not wrong to let die or kill, when they have lost consciousness. Therefore, perhaps some other human beings, like early fetuses, are also not wrong to kill before they have gained consciousness . And if we are not the same “kind” of beings, or have different essences, then perhaps we also aren’t the same kind of beings as fetuses either.

Similar questions arise concerning anencephalic babies, tragically born without most of their brains: are they the same “kind” of beings as “regular” babies or us? If so, then—since such babies are arguably morally permissible to let die, even when they could be kept alive, since being alive does them no good—then being of our “kind” doesn’t mean the individual has the same rights as us, since letting us die would be wrong. But if such babies are a different “kind” of beings than us, then pre-conscious fetuses might be of a relevantly different kind also.

So, in general, this proposal that early fetuses essentially have rights is suspect, if we evaluate the reasons given in its support. Even if fetuses and us are the same “kind” of beings (which perhaps we are not!) that doesn’t immediately tell us what rights fetuses would have, if any. And we might even reasonably think that, despite our being the same kind of beings as fetuses (e.g., the same kind of biology), we are also importantly different kinds of beings (e.g., one kind with a mental life and another kind which has never had it). This photograph of a 6-week old fetus might help bring out the ambiguity in what kinds of beings we all are:

In sum, the abstract view that all human organisms have rights essentially needs to be plausibly explained and defended. We need to understand how it really works. We need to be shown why it’s a better explanation, all things considered, than a consciousness and feelings-based theory of rights that simply explains why we, and babies, have rights, why racism, sexism and other forms of clearly wrongful discrimination are wrong, and , importantly, how we might lose rights in irreversible coma cases (if people always retained the right to life in these circumstances, presumably, it would be wrong to let anyone die), and more.

5.1.3 Fetuses are persons

Finally, we get to what some see as the core issue here, namely whether fetuses are persons , and an argument like this:

Fetuses are persons, perhaps from conception.

Persons have the right to life and are wrong to kill.

So, abortion is wrong, as it involves killing persons.

The second premise seems very plausible, but there are some important complications about it that will be discussed later. So let’s focus on the idea of personhood and whether any fetuses are persons. What is it to be a person ? One answer that everyone can agree on is that persons are beings with rights and value . That’s a fine answer, but it takes us back to the initial question: OK, who or what has the rights and value of persons? What makes someone or something a person?

Answers here are often merely asserted , but these answers need to be tested: definitions can be judged in terms of whether they fit how a word is used. We might begin by thinking about what makes us persons. Consider this:

We are persons now. Either we will always be persons or we will cease being persons. If we will cease to be persons, what can end our personhood? If we will always be persons, how could that be?

Both options yield insight into personhood. Many people think that their personhood ends at death or if they were to go into a permanent coma: their body is (biologically) alive but the person is gone: that is why other people are sad. And if we continue to exist after the death of our bodies, as some religions maintain, what continues to exist? The person , perhaps even without a body, some think! Both responses suggest that personhood is defined by a rough and vague set of psychological or mental, rational and emotional characteristics: consciousness, knowledge, memories, and ways of communicating, all psychologically unified by a unique personality.

A second activity supports this understanding:

Make a list of things that are definitely not persons . Make a list of individuals who definitely are persons . Make a list of imaginary or fictional personified beings which, if existed, would be persons: these beings that fit or display the concept of person, even if they don’t exist. What explains the patterns of the lists?

Rocks, carrots, cups and dead gnats are clearly not persons. We are persons. Science fiction gives us ideas of personified beings: to give something the traits of a person is to indicate what the traits of persons are, so personified beings give insights into what it is to be a person. Even though the non-human characters from, say, Star Wars don’t exist, they fit the concept of person: we could befriend them, work with them, and so on, and we could only do that with persons. A common idea of God is that of an immaterial person who has exceptional power, knowledge, and goodness: you couldn’t pray to a rock and hope that rock would respond: you could only pray to a person. Are conscious and feeling animals, like chimpanzees, dolphins, cats, dogs, chickens, pigs, and cows more relevantly like us, as persons, or are they more like rocks and cabbages, non-persons? Conscious and feeling animals seem to be closer to persons than not. 13 So, this classificatory and explanatory activity further supports a psychological understanding of personhood: persons are, at root, conscious, aware and feeling beings.

Concerning abortion, early fetuses would not be persons on this account: they are not yet conscious or aware since their brains and nervous systems are either non-existent or insufficiently developed. Consciousness emerges in fetuses much later in pregnancy, likely after the first trimester or a bit beyond. This is after when most abortions occur. Most abortions, then, do not involve killing a person , since the fetus has not developed the characteristics for personhood. We will briefly discuss later abortions, that potentially affect fetuses who are persons or close to it, below.

It is perhaps worthwhile to notice though that if someone believed that fetuses are persons and thought this makes abortion wrong, it’s unclear how they could coherently believe that a pregnancy resulting from rape or incest could permissibly be ended by an abortion. Some who oppose abortion argue that, since you are a person, it would be wrong to kill you now even if you were conceived because of a rape, and so it’s wrong to kill any fetus who is a person, even if they exist because of a rape: whether someone is a person or not doesn’t depend on their origins: it would make no sense to think that, for two otherwise identical fetuses, one is a person but the other isn’t, because that one was conceived by rape. Therefore, those who accept a “personhood argument” against abortion, yet think that abortions in cases of rape are acceptable, seem to have an inconsistent view.

5.1.4 Fetuses are potential persons

If fetuses aren’t persons, they are at least potential persons, meaning they could and would become persons. This is true. This, however, doesn’t mean that they currently have the rights of persons because, in general, potential things of a kind don’t have the rights of actual things of that kind : potential doctors, lawyers, judges, presidents, voters, veterans, adults, parents, spouses, graduates, moral reasoners and more don’t have the rights of actual individuals of those kinds.

Some respond that potential gives the right to at least try to become something. But that trying sometimes involves the cooperation of others: if your friend is a potential medical student, but only if you tutor her for many hours a day, are you obligated to tutor her? If my child is a potential NASCAR champion, am I obligated to buy her a race car to practice? ‘No’ to both and so it is unclear that a pregnant woman would be obligated to provide what’s necessary to bring about a fetus’s potential. (More on that below, concerning the what obligations the right to life imposes on others, in terms of obligations to assist other people.)

5.1.5 Abortion prevents fetuses from experiencing their valuable futures

The argument against abortion that is likely most-discussed by philosophers comes from philosopher Don Marquis. 14 He argues that it is wrong to kill us, typical adults and children, because it deprives us from experiencing our (expected to be) valuable futures, which is a great loss to us . He argues that since fetuses also have valuable futures (“futures like ours” he calls them), they are also wrong to kill. His argument has much to recommend it, but there are reasons to doubt it as well.

First, fetuses don’t seem to have futures like our futures , since—as they are pre-conscious—they are entirely psychologically disconnected from any future experiences: there is no (even broken) chain of experiences from the fetus to that future person’s experiences. Babies are, at least, aware of the current moment, which leads to the next moment; children and adults think about and plan for their futures, but fetuses cannot do these things, being completely unconscious and without a mind.

Second, this fact might even mean that the early fetus doesn’t literally have a future: if your future couldn’t include you being a merely physical, non-conscious object (e.g., you couldn’t be a corpse: if there’s a corpse, you are gone), then non-conscious physical objects, like a fetus, couldn’t literally be a future person. 15 If this is correct, early fetuses don’t even have futures, much less futures like ours. Something would have a future, like ours, only when there is someone there to be psychologically connected to that future: that someone arrives later in pregnancy, after when most abortions occur.

A third objection is more abstract and depends on the “metaphysics” of objects. It begins with the observation that there are single objects with parts with space between them . Indeed almost every object is like this, if you could look close enough: it’s not just single dinette sets, since there is literally some space between the parts of most physical objects. From this, it follows that there seem to be single objects such as an-egg-and-the-sperm-that-would-fertilize-it . And these would also seem to have a future of value, given how Marquis describes this concept. (It should be made clear that sperm and eggs alone do not have futures of value, and Marquis does not claim they do: this is not the objection here). The problem is that contraception, even by abstinence , prevents that thing’s future of value from materializing, and so seems to be wrong when we use Marquis’s reasoning. Since contraception is not wrong, but his general premise suggests that it is , it seems that preventing something from experiencing its valuable future isn’t always wrong and so Marquis’s argument appears to be unsound. 16

In sum, these are some of the most influential arguments against abortion. Our discussion was brief, but these arguments do not appear to be successful: they do not show that abortion is wrong, much less make it clear and obvious that abortion is wrong.

Four pro-life philosophers make the case against abortion

To put it mildly, the American Philosophical Association is not a bastion of pro-life sentiment. Hence, I was surprised to discover that the A.P.A. had organized a pro-life symposium, “New Pro-Life Bioethics,” at our annual conference this month in Philadelphia. Hosted by Jorge Garcia (Boston College), the panel featured the philosophers Celia Wolf-Devine (Stonehill College), Anthony McCarthy (Bios Centre in London) and Francis Beckwith (Baylor University), all of whom presented the case against abortion in terms of current political and academic values.

Recognizing the omnipresent call for a “welcoming” society, Ms. Wolf-Devine explored contemporary society’s emphasis on the virtue of inclusion and the vice of exclusion. The call for inclusion emphasizes the need to pay special attention to the more vulnerable members of society, who can easily be treated as non-persons in society’s commerce. She argued that our national practice of abortion, comparatively one of the most extreme in terms of legal permissiveness, contradicts the good of inclusion by condemning an entire category of human beings to death, often on the slightest of grounds. There is something contradictory in a society that claims to be welcoming and protective of the vulnerable but that shows a callous indifference to the fate of human beings before the moment of birth.

There is something contradictory in a society that claims to be protective of the vulnerable but shows a callous indifference to the fate of human beings before the moment of birth.

Mr. McCarthy’s paper tackled the question of abortion from the perspective of equality. A common egalitarian argument in favor of abortion and the funding thereof goes something like this: If a woman has an unwanted pregnancy and is denied access to abortion, she might be required to sacrifice educational and work opportunities. Since men do not become pregnant, they face no such obstacles to pursuing their professional goals. Restrictions to abortion access thus places women in a position of inequality with men.

Mr. McCarthy counter-argued that, in fact, the practice of abortion creates a certain inequality between men and women since it does not respect the experiences, such as pregnancy, which are unique to women. Some proponents of abortion deride pregnancy as a malign condition. A disgruntled audience member referred to pregnant women as “incubators.” Mr. McCarthy argued that authentic gender equality involves respect for what makes women different, including support for the well-being of both women and children through pregnancy, childbirth and beyond. He pointed out that in his native England, pregnant women acting as surrogates are given a certain amount of time after birth to decide whether to keep the child they bore and not fulfill the conditions of the surrogacy contract. This is done out of acknowledgment of the gender-specific biological and emotional changes undergone by a woman who has nurtured a child in the womb.

The most compelling argument against abortion remains what it has been for decades: Directly killing innocent human beings is gravely unjust.

Mr. Beckwith explored the question of abortion in light of the longstanding philosophical dispute concerning the “criteria of personhood.” The question of which human beings count as persons is closely yoked to the political question of which human beings will receive civil protection and which can be killed without legal penalty. The personhood criteria range from the most inclusive (genetic identity as a member of the species Homo sapiens ) to the more restrictive (evidence of consciousness) to the most exclusionary (evidence of rationality and self-motivating behavior).

Mr. Beckwith has long used the argument from personal identity (the continuity between my mature, conscious self and my embryonic, fetal and childhood self and my future older, possibly demented self) to make the case against abortion, infanticide and euthanasia. To draw the line between personhood and non-personhood after conception or before natural death is to make an arbitrary distinction—and a lethal one at that. Mr. Beckwith noted, however, that none of the usual candidates for a criterion of personhood is completely satisfying. Even the common pro-life argument from species membership could, unamended, smack of a certain materialism.

The most compelling argument against abortion remains what it has been for decades: Directly killing innocent human beings is gravely unjust. Abortion is the direct killing of innocent human beings. But political debate rarely proceeds by such crystalline syllogisms. The aim of the A.P.A.’s pro-life symposium was to amplify the argument by showing how our practice of abortion brutally violates the values of inclusion, equality and personhood that contemporary society claims to cherish. In the very month we grimly commemorate Roe v. Wade, such new philosophical directions are welcome winter light.

John J. Conley, S.J., is a Jesuit of the Maryland Province and a regular columnist for America . He is the current Francis J. Knott Chair of Philosophy and Theology at Loyola University, Maryland.

Most popular

Your source for jobs, books, retreats, and much more.

The latest from america

There’s a Better Way to Debate Abortion

Caution and epistemic humility can guide our approach.

If Justice Samuel Alito’s draft majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization becomes law, we will enter a post– Roe v. Wade world in which the laws governing abortion will be legislatively decided in 50 states.

In the short term, at least, the abortion debate will become even more inflamed than it has been. Overturning Roe , after all, would be a profound change not just in the law but in many people’s lives, shattering the assumption of millions of Americans that they have a constitutional right to an abortion.

This doesn’t mean Roe was correct. For the reasons Alito lays out, I believe that Roe was a terribly misguided decision, and that a wiser course would have been for the issue of abortion to have been given a democratic outlet, allowing even the losers “the satisfaction of a fair hearing and an honest fight,” in the words of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Instead, for nearly half a century, Roe has been the law of the land. But even those who would welcome its undoing should acknowledge that its reversal could convulse the nation.

From the December 2019 issue: The dishonesty of the abortion debate

If we are going to debate abortion in every state, given how fractured and angry America is today, we need caution and epistemic humility to guide our approach.

We can start by acknowledging the inescapable ambiguities in this staggeringly complicated moral question. No matter one’s position on abortion, each of us should recognize that those who hold views different from our own have some valid points, and that the positions we embrace raise complicated issues. That realization alone should lead us to engage in this debate with a little more tolerance and a bit less certitude.

Many of those on the pro-life side exhibit a gap between the rhetoric they employ and the conclusions they actually seem to draw. In the 1990s, I had an exchange, via fax, with a pro-life thinker. During our dialogue, I pressed him on what he believed, morally speaking , should be the legal penalty for a woman who has an abortion and a doctor who performs one.

My point was a simple one: If he believed, as he claimed, that an abortion even moments after conception is the killing of an innocent child—that the fetus, from the instant of conception, is a human being deserving of all the moral and political rights granted to your neighbor next door—then the act ought to be treated, if not as murder, at least as manslaughter. Surely, given what my interlocutor considered to be the gravity of the offense, fining the doctor and taking no action against the mother would be morally incongruent. He was understandably uncomfortable with this line of questioning, unwilling to go to the places his premises led. When it comes to abortion, few people are.

Humane pro-life advocates respond that while an abortion is the taking of a human life, the woman having the abortion has been misled by our degraded culture into denying the humanity of the child. She is a victim of misinformation; she can’t be held accountable for what she doesn’t know. I’m not unsympathetic to this argument, but I think it ultimately falls short. In other contexts, insisting that people who committed atrocities because they truly believed the people against whom they were committing atrocities were less than human should be let off the hook doesn’t carry the day. I’m struggling to understand why it would in this context.

There are other complicating matters. For example, about half of all fertilized eggs are aborted spontaneously —that is, result in miscarriage—usually before the woman knows she is pregnant. Focus on the Family, an influential Christian ministry, is emphatic : “Human life begins at fertilization.” Does this mean that when a fertilized egg is spontaneously aborted, it is comparable—biologically, morally, ethically, or in any other way—to when a 2-year-old child dies? If not, why not? There’s also the matter of those who are pro-life and contend that abortion is the killing of an innocent human being but allow for exceptions in the case of rape or incest. That is an understandable impulse but I don’t think it’s a logically sustainable one.

The pro-choice side, for its part, seldom focuses on late-term abortions. Let’s grant that late-term abortions are very rare. But the question remains: Is there any point during gestation when pro-choice advocates would say “slow down” or “stop”—and if so, on what grounds? Or do they believe, in principle, that aborting a child up to the point of delivery is a defensible and justifiable act; that an abortion procedure is, ethically speaking, the same as removing an appendix? If not, are those who are pro-choice willing to say, as do most Americans, that the procedure gets more ethically problematic the further along in a pregnancy?

Read: When a right becomes a privilege

Plenty of people who consider themselves pro-choice have over the years put on their refrigerator door sonograms of the baby they are expecting. That tells us something. So does biology. The human embryo is a human organism, with the genetic makeup of a human being. “The argument, in which thoughtful people differ, is about the moral significance and hence the proper legal status of life in its early stages,” as the columnist George Will put it.

These are not “gotcha questions”; they are ones I have struggled with for as long as I’ve thought through where I stand on abortion, and I’ve tried to remain open to corrections in my thinking. I’m not comfortable with those who are unwilling to grant any concessions to the other side or acknowledge difficulties inherent in their own position. But I’m not comfortable with my own position, either—thinking about abortion taking place on a continuum, and troubled by abortions, particularly later in pregnancy, as the child develops.

The question I can’t answer is where the moral inflection point is, when the fetus starts to have claims of its own, including the right to life. Does it depend on fetal development? If so, what aspect of fetal development? Brain waves? Feeling pain? Dreaming? The development of the spine? Viability outside the womb? Something else? Any line I might draw seems to me entirely arbitrary and capricious.

Because of that, I consider myself pro-life, but with caveats. My inability to identify a clear demarcation point—when a fetus becomes a person—argues for erring on the side of protecting the unborn. But it’s a prudential judgment, hardly a certain one.

At the same time, even if one believes that the moral needle ought to lean in the direction of protecting the unborn from abortion, that doesn’t mean one should be indifferent to the enormous burden on the woman who is carrying the child and seeks an abortion, including women who discover that their unborn child has severe birth defects. Nor does it mean that all of us who are disturbed by abortion believe it is the equivalent of killing a child after birth. In this respect, my view is similar to that of some Jewish authorities , who hold that until delivery, a fetus is considered a part of the mother’s body, although it does possess certain characteristics of a person and has value. But an early-term abortion is not equivalent to killing a young child. (Many of those who hold this position base their views in part on Exodus 21, in which a miscarriage that results from men fighting and pushing a pregnant woman is punished by a fine, but the person responsible for the miscarriage is not tried for murder.)

“There is not the slightest recognition on either side that abortion might be at the limits of our empirical and moral knowledge,” the columnist Charles Krauthammer wrote in 1985. “The problem starts with an awesome mystery: the transformation of two soulless cells into a living human being. That leads to an insoluble empirical question: How and exactly when does that occur? On that, in turn, hangs the moral issue: What are the claims of the entity undergoing that transformation?”

That strikes me as right; with abortion, we’re dealing with an awesome mystery and insoluble empirical questions. Which means that rather than hurling invective at one another and caricaturing those with whom we disagree, we should try to understand their views, acknowledge our limitations, and even show a touch of grace and empathy. In this nation, riven and pulsating with hate, that’s not the direction the debate is most likely to take. But that doesn’t excuse us from trying.

Princeton Legal Journal

The First Amendment and the Abortion Rights Debate

Sofia Cipriano

Following Dobbs v. Jackson ’s (2022) reversal of Roe v. Wade (1973) — and the subsequent revocation of federal abortion protection — activists and scholars have begun to reconsider how to best ground abortion rights in the Constitution. In the past year, numerous Jewish rights groups have attempted to overturn state abortion bans by arguing that abortion rights are protected by various state constitutions’ free exercise clauses — and, by extension, the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. While reframing the abortion rights debate as a question of religious freedom is undoubtedly strategic, the Free Exercise Clause is not the only place to locate abortion rights: the Establishment Clause also warrants further investigation.

Roe anchored abortion rights in the right to privacy — an unenumerated right with a long history of legal recognition. In various cases spanning the past two centuries, t he Supreme Court located the right to privacy in the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments . Roe classified abortion as a fundamental right protected by strict scrutiny, meaning that states could only regulate abortion in the face of a “compelling government interest” and must narrowly tailor legislation to that end. As such, Roe ’s trimester framework prevented states from placing burdens on abortion access in the first few months of pregnancy. After the fetus crosses the viability line — the point at which the fetus can survive outside the womb — states could pass laws regulating abortion, as the Court found that “the potentiality of human life” constitutes a “compelling” interest. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) later replaced strict scrutiny with the weaker “undue burden” standard, giving states greater leeway to restrict abortion access. Dobbs v. Jackson overturned both Roe and Casey , leaving abortion regulations up to individual states.

While Roe constituted an essential step forward in terms of abortion rights, weaknesses in its argumentation made it more susceptible to attacks by skeptics of substantive due process. Roe argues that the unenumerated right to abortion is implied by the unenumerated right to privacy — a chain of logic which twice removes abortion rights from the Constitution’s language. Moreover, Roe’s trimester framework was unclear and flawed from the beginning, lacking substantial scientific rationale. As medicine becomes more and more advanced, the arbitrariness of the viability line has grown increasingly apparent.

As abortion rights supporters have looked for alternative constitutional justifications for abortion rights, the First Amendment has become increasingly more visible. Certain religious groups — particularly Jewish groups — have argued that they have a right to abortion care. In Generation to Generation Inc v. Florida , a religious rights group argued that Florida’s abortion ban (HB 5) constituted a violation of the Florida State Constitution: “In Jewish law, abortion is required if necessary to protect the health, mental or physical well-being of the woman, or for many other reasons not permitted under the Act. As such, the Act prohibits Jewish women from practicing their faith free of government intrusion and thus violates their privacy rights and religious freedom.” Similar cases have arisen in Indiana and Texas. Absent constitutional protection of abortion rights, the Christian religious majorities in many states may unjustly impose their moral and ethical code on other groups, implying an unconstitutional religious hierarchy.

Cases like Generation to Generation Inc v. Florida may also trigger heightened scrutiny status in higher courts; The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993) places strict scrutiny on cases which “burden any aspect of religious observance or practice.”

But framing the issue as one of Free Exercise does not interact with major objections to abortion rights. Anti-abortion advocates contend that abortion is tantamount to murder. An anti-abortion advocate may argue that just as religious rituals involving human sacrifice are illegal, so abortion ought to be illegal. Anti-abortion advocates may be able to argue that abortion bans hold up against strict scrutiny since “preserving potential life” constitutes a “compelling interest.”

The question of when life begins—which is fundamentally a moral and religious question—is both essential to the abortion debate and often ignored by left-leaning activists. For select Christian advocacy groups (as well as other anti-abortion groups) who believe that life begins at conception, abortion bans are a deeply moral issue. Abortion bans which operate under the logic that abortion is murder essentially legislate a definition of when life begins, which is problematic from a First Amendment perspective; the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment prevents the government from intervening in religious debates. While numerous legal thinkers have associated the abortion debate with the First Amendment, this argument has not been fully litigated. As an amicus brief filed in Dobbs by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Center for Inquiry, and American Atheists points out, anti-abortion rhetoric is explicitly religious: “There is hardly a secular veil to the religious intent and positions of individuals, churches, and state actors in their attempts to limit access to abortion.” Justice Stevens located a similar issue with anti-abortion rhetoric in his concurring opinion in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989) , stating: “I am persuaded that the absence of any secular purpose for the legislative declarations that life begins at conception and that conception occurs at fertilization makes the relevant portion of the preamble invalid under the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Federal Constitution.” Judges who justify their judicial decisions on abortion using similar rhetoric blur the line between church and state.

Framing the abortion debate around religious freedom would thus address the two main categories of arguments made by anti-abortion activists: arguments centered around issues with substantive due process and moral objections to abortion.

Conservatives may maintain, however, that legalizing abortion on the federal level is an Establishment Clause violation to begin with, since the government would essentially be imposing a federal position on abortion. Many anti-abortion advocates favor leaving abortion rights up to individual states. However, in the absence of recognized federal, constitutional protection of abortion rights, states will ban abortion. Protecting religious freedom of the individual is of the utmost importance — the United States government must actively intervene in order to uphold the line between church and state. Protecting abortion rights would allow everyone in the United States to act in accordance with their own moral and religious perspectives on abortion.

Reframing the abortion rights debate as a question of religious freedom is the most viable path forward. Anchoring abortion rights in the Establishment Clause would ensure Americans have the right to maintain their own personal and religious beliefs regarding the question of when life begins. In the short term, however, litigants could take advantage of Establishment Clauses in state constitutions. Yet, given the swing of the Court towards expanding religious freedom protections at the time of writing, Free Exercise arguments may prove better at securing citizens a right to an abortion.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Abortion Rights: For and Against

Kate Greasley and Christopher Kaczor, Abortion Rights: For and Against , Cambridge University Press, 2018, 260pp., $29.99 (pbk), ISBN 9781316621851.

Reviewed by M. T. Lu, University of St. Thomas (Minnesota)

The editorial front matter in this volume claims that the book "gives readers a window into how moral philosophers argue about the contention issue of abortion rights." As a descriptive claim this strikes me as largely true. Unfortunately, how many "moral philosophers" actually do argue about this issue is not how they should.

The book consists of two essays written (apparently independently) by Kate Greasley (pro-abortion) and by Christopher Kaczor (anti-abortion), followed by a response from each author to the other, and finally a short reply to each response. Greasley begins the central argumentative part of her essay in favor of abortion rights by conceding what she calls the "silver bullet," namely that "if the fetus is a person, equivalent in value to a born human being, then abortion is almost always morally wrong and legal abortion permissions almost entirely unjustified" (5). In other words, she identifies moral personhood as the gravamen of the abortion question, setting aside (without argument) so-called women's rights arguments (of the sort made famous by Judith Jarvis Thomson) that abortion can still be justified even if the unborn child is a person.

This concession makes it immediately clear that her essay is not intended to be any kind of synopsis of the pro-choice side of the abortion debate, but to advance what Greasley herself takes to be the strongest case for the non-personhood of the unborn child. This is significant because many pro-choice writers take women's rights style arguments to be more effective, both because they prescind from many of the difficult questions about the nature of the child, but also because they purport to establish the moral permissibility of abortion even if the unborn child is a person. To concede this point, then, is to give up a lot of ground pro-choice writers have long coveted and so must presumably express Greasley's confidence in her own capacity to establish the non-personhood of the fetus.

Unfortunately, anyone expecting some kind of a new argument (much less one likely to change the mind of anyone already familiar with the abortion literature) will be disappointed. Greasley's argumentative strategy is well-worn. She defends a version of the familiar "developmental view" largely drawn from Mary Anne Warren which "takes personhood or moral status to supervene on developmentally acquired capacities, most notably psychological capacities such as consciousness, ability to reason, communication, independent agency, and the ability to form conscious desires" (26). While such traits may not all be necessary for personhood, Greasley concurs with Warren that "a creature could not lack all of the traits and yet be a person" (26).

She proposes that the non-personhood of the fetus can be established by means of three thought experiments, one of which -- the "embryo rescue case" (ERC) -- she seems to think is nearly dispositive. This is something like a trolley scenario in which we are invited to choose between rescuing "five frozen human embryos" or "one fully formed human baby" from a burning building. Greasley holds that it would be "unthinkable" to rescue the embryos "despite the fact that the embryos number five and the baby only one" (27). This she takes to be deeply problematic for anyone holding the standard pro-life view that the embryos are "morally considerable persons." Ultimately, she thinks this shows that "people simply do not believe that death is as serious for the embryo, or as tragic from an impartial point of view, as infant death or the death of an adult human being" (30). Accordingly, "the [intuitive] pull to save the baby . . . rather than the embryos -- even though this would mean saving the one over the many -- tells us something meaningful about our view of the relative status of embryos and born human beings" (31, emphasis in original).

Greasley's thought here is straightforward: if people would save one infant over five embryos, then they simply cannot believe that those embryos are "morally considerable persons." Of course, even if this is what the respondents believe , that doesn't by itself show that the belief is true . To be fair, Greasley does somewhat concede this point, noting that historically many have (falsely) denied the moral status of certain groups. Nonetheless, she largely dismisses the possibility that this is just a mistaken belief and seems to think the only truly plausible explanation for the near universal intuition is a (warranted) belief that the infant is a person and the embryos are not.

I do not have much confidence in the philosophical helpfulness of these sorts of cases in general, but if we are forced to play this game some reflection will show that the ERC doesn't have nearly the force Greasley want to gives it. Consider a parallel case in which we have to choose between saving five fully conscious nonagenarians and one baby. Perhaps I am unusual, but my intuitions are almost entirely in favor of the baby, "even though this would mean saving the one over the many." This is obviously not because I think the elderly are not persons. In fact, forced to choose, I wouldn't hesitate much between saving, say, one mother with small children over five childless, middle-aged tenured philosophy professors. Again, this is not because I deny the personhood of my colleagues (certain faculty meetings notwithstanding), but for the simple reason that I genuinely believe that it would very likely be worse for several small children to lose their mother than for five childless adults to die tragically (though, of course, there are possible circumstances that might cause me to reconsider). In short, a decided preference for one over many does not by itself entail, or even strongly suggest, a clear denial of the personhood of the many.

In the end, though, the larger problem with Greasley's approach is not merely competing intuitions. The personhood question really cannot be convincingly settled by this sort of intuition pumping. Indeed, it is precisely the intractability of the personhood question that leads so many pro-choice writers to embrace a women's right approach that putatively allows them to prescind from the question.

To her credit, after presenting her thought experiments Greasley does at least make some effort to engage personhood arguments. However, she is unsuccessful because her criticisms make clear that she doesn't really understand what she is criticizing. While there are a number of approaches to arguing for the personhood of the unborn child (and both authors discuss Don Marquis' famous "future like ours" argument at length) the key one here is Christopher Kaczor's "Personhood as Endowment" argument.

Kaczor begins by distinguishing a "functional" view of personhood from his "endowment" (or sometimes "substance") view. The functional view (of which Warren's and Greasley's accounts are examples) makes personhood dependent on the occurrent exercise of certain (especially rational) powers. By contrast, on the endowment view "it is sufficient for moral status to be capable of sentience or capable of rational functioning. An appeal is made here not to actual functioning but to the kind of thing the being is, the kind of being capable of sentience or rational functioning" (135). So, what matters for the personhood of the unborn child (or anyone else, such as a sleeping adult) is not whether that individual is currently exercising or demonstrating the powers characteristic of a person, but whether that individual is the kind of being that is rational (or sentient, etc.) by nature.

On this view, any and all human beings, from conception onwards, are rational creatures. If all rational creatures (human or otherwise) are persons, then all human beings are persons. As Kaczor puts it, the "substance view rests on the claim that each and every human being (born and unborn) actually (not just potentially) possesses a rational nature, and therefore merits fundamental respect as a rational being" (135-6, emphasis added).

That Greasley misunderstands the view is clear from her attempt to criticize it. She claims that "if we award [the young] equal moral status, this can only be on the basis of their potential to exercise those capacities in the future " (50, emphasis added). In short, they have a right to life not because they are actual persons, but because "they are at least potential persons in that they are individual human organisms that will, if they survive and develop, eventually become persons" (50). However, she notes that this "potentiality principles suffers . . . from an obvious logical problem . . . [that] there is no reason why being a potential person ought to endow a creature with the very same rights as an actual person" (51). Given that obvious problem, one would think Greasley should give more thought to why pro-life writers, Kaczor included, have continued to insist on the point.

In his initial response, Kaczor notes that he has "never encountered a single scholar who defends the view that the prenatal human being has a right to live because he or she is a potential person . . . The classic pro-life view is not that the prenatal human being is a potential person , but rather that the prenatal human being is a person with potential " (196). Unfortunately, after saying this, he does not go on to explain what it means or why exactly, which is the greatest defect in his part of the book.

In fact, the substance view is rooted in Aristotle's philosophy of nature. While contemporary neo-Aristotelians and Thomists have developed the view considerably, the relevant issue here is that any (putative) potential must belong to a substance with a particular nature. To say that a particular substance has a potential to develop in some way is not to make a prediction about the future , but to make a claim about that thing's nature right now . On this view, no non-rational being can ever develop rational powers ( de novo ) and remain the same thing. [1] Rather, insofar as a rational being begins to exercise those powers at some point in its life it does so precisely because they were always already latent in its nature. To say that a fetus is "potentially rational" is not to say that it will become a rational being when it begins to exercise those powers; it is rather to say that its (latent) rational nature will (likely, but not necessarily) become more fully actualized. [2]

Greasley's putative counterexamples show that she doesn't understand this. She claims that just "as a caterpillar that metamorphoses into a butterfly appears to go through a fundamental and substantial change in nature while remaining the same thing , so it seems true to say of human beings that when the go through a fundamental change in nature as when they become persons, while remaining the same numerical entity" (183). Similarly, she claims her imagined interlocutor "presumably would not agree that dead human bodies are persons . . . even though they are . . . numerically identical with the human being that was alive" (183).

For the substance theorist, neither example makes sense. The caterpillar cannot undergo "a fundamental and substantial change" and yet remain "the same thing" because a substantial change, by definition, involves the destruction of the original thing. The substance theorist would say that the caterpillar has not undergone a substantial change at all (and therefore is numerically identical to the butterfly) but has, well, metamorphosed (i.e., literally, "changed shape"). In Greasley's other case, the substance theorist does not regard a corpse as numerically identical with the human being that was alive, precisely because death is a substantial change .

On this view, the identity of a substance across the actualization of some potency just means that the change in question is not (and cannot be) a substantial change. Instead, such a (developmental) change is the actualization of a latent potency that was always already there in the nature of that substance. This is exactly how a substance theorist understands the human being from conception: as a substance of a rational nature. While the zygote, embryo, fetus, infant, etc. cannot occurrently exercise any rational powers, he or she is a rational creature from the moment of his or her substantial existence. Furthermore, since classical substance theorists hold organisms to be paradigmatic substances, the beginning of the rational substance is identical with the beginning of the organism. Accordingly, the human organism cannot become a person, because that would constitute a substantial change. So, if the being capable of exercising rational powers at some point (say, t + 7 years) is numerically identical with the fetus at t, that just means no substantial change can have occurred between t and t+7.

Of course, this just scratches the surface in articulating the substance view and none of this shows that it is correct. Like any other serious philosophical view, it requires development and defense from a variety of possible objections. My point is simply that Greasley has not raised the right kind of objections, because her criticisms reveal that she's attacking a straw man. As I noted above, however, I also think Kaczor can be legitimately criticized for failing to make clear why this is so. While he often notes Greasley's misunderstandings, he doesn't really show why she's failing to engage the substance view.

Ultimately, this is what I mean when I say the book reflects how "moral philosophers" do argue about abortion, rather than how they should. The kinds of criticisms Greasley offers of potentiality reflect the same kind of misunderstanding of the substance view that Michael Tooley has been offering since the early 70's. There isn't a real dialectic here because Greasley doesn't adequately understand the view she's criticizing and Kaczor hasn't adequately articulated and defended its deeper basis. Greasley's arguments fall flat largely because she's attempting to establish the non-personhood of the unborn child through superficial thought experiments without even grappling with the deeper metaphysical issues at hand. In short, Greasley is talking past Kaczor, not actually identifying and attacking putatively false premises or fallacious reasoning. For Kaczor's part, while I think he does a better job of actually engaging various pro-choice arguments overall, he still leaves much too much unsaid.

In the end, it's not clear what philosophical purpose this book best serves. It does not offer any significantly new arguments (nor do the authors claim otherwise). Neither is it an attempt to summarize the state of the abortion debate, as large parts of that debate are elided or ignored (e.g. the women's rights arguments and the more recent virtue ethics discussions). Even just with regards to the views of the two authors, it's unnecessary in that each of them has a more complete monograph on the subject. I find these sorts of "for and against" books are rarely that successful, and I fear this one will only tend to confirm that judgment.

[1] If Michael Tooley’s famous kitten example (a magic serum that makes a normal kitten into a rational cat) were actually possible, it would constitute a substantial change.

[2] On this view, the claim “human beings are rational” is an example of what Michael Thompson has called an “Aristotelian Categorical.” It is parallel to the claim that “human beings are bipedal” and would not be falsified by adducing an example of a human being born without legs, nor by a normal infant who cannot (yet and may never) walk. Needless to say, much more can and should be said that space does not permit.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

A scientist weighs up the five main anti-abortion arguments

In the last week alone, abortion has caused controversy in the US , the UK and in Chile . Medical science is often invoked on both sides of the debate. So what is the evidence on some of the main claims around abortion?

There are few topics in modern discourse quite as divisive, as fraught with misunderstanding and as rooted in deeply-held conviction as abortion.

Those on the pro-choice side of the spectrum argue that it is a woman’s right to choose whether she carries a pregnancy to term or not. On the other side, anti-abortion activists insist that from the moment of conception a foetus has an inalienable right to existence. In recent years, polarisation has increased and the topic has become exceptionally politically partisan, with the personal and political aspects increasingly difficult to separate.

Amid all the passionate argument, it is easy for misunderstandings and fictions to fill the void between opposing ideologies. Yet if we are to have a reasoned discussion about abortion rights, we have to jettison the persistent falsehoods that cloud the topic. If we are to choose reason over rhetoric, it is worth addressing some of the more pernicious myths that emerge each time the abortion question is raised.

Abortion leads to depression and suicide

Of all the myths surrounding abortion, I feel that the assertion that it leads to depression and suicide must rank as the most odious. It is a perennial favourite of anti-abortion groups. Anti-abortion campaigners call it PAS – post-abortion-syndrome, a term coined by Dr Vincent Rue . Rue is a prolific anti-abortion campaigner who testified before the US Congress in 1981 that he had observed post-traumatic stress syndrome in women who had undergone abortions. The claim rapidly mutated into the ominous and potent suggestion that abortion leads to suicide and depression. Yet despite the ubiquity of this claim by anti-abortion advocates, PAS is not recognised by relevant expert bodies. It does not appear in the DSM-V (the handbook of mental health), and the link between abortion and mental health problems is dismissed by organisations tasked with mental health protection including the American Psychological Association , the American Psychiatric Association and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists .

The reason for this dismissive attitude is simple: despite years of research there is no evidence that PAS exists. The hypothesis that women who undergo an abortion have worse mental health outcomes than those that don’t is at heart a scientific claim and can be tested as such. One recent study in Denmark charted the psychological health of 365,550 women, including 84,620 who’d had abortions. They found neither an increase in psychological damage, nor any elevated risk of suicide. This finding isn’t especially surprising, as previous investigations found that provided a woman was not already depressive then “elective abortion of an unintended pregnancy does not pose a risk to mental health”. In an article for the Journal of the American Medical Association entitled “The myth of the abortion trauma syndrome” , Dr. Nada Stotland eloquently stated the disconnect between the message of anti-choice organisations and the peer-reviewed literature on the subject: “Currently, there are active attempts to convince the public and women considering abortion that abortion frequently has negative psychiatric consequences. This assertion is not borne out by the literature: the vast majority of women tolerate abortion without psychiatric sequelae”, a conclusion echoed in systematic reviews .

But despite the science simply not supporting the assertions of the anti-abortion brigade, the myth persists. In a relatively recent move, some US states now require physicians to warn women seeking an abortion of the dangers to their mental health, in spite of the complete lack of scientific justification for doing so. In South Dakota, a 2005 state law not only mandated this perversion of informed consent, but also added a reprehensible smattering of emotional manipulation by insisting women be told they are terminating “a whole, separate, unique, living human being”. The jarring disconnect between scientific best evidence and the practices enforced by legislation is worrying, expressed with weary regret by the Guttmacher institute : “ ... anti-abortion activists are able to take advantage of the fact that the general public and most policy-makers do not know what constitutes “good science ... to defend their positions, these activists often cite studies that have serious methodological flaws or draw inappropriate conclusions from more rigorous studies”.

Contrary to the assertions of anti-abortion activists, the majority of women granted an abortion report relief as their primary feeling, not depression. The research also unveils a subtle but important corollary; whilst women are don’t generally suffer long-term mental health effects related to the abortion, short term guilt and sadness was far more likely if the women came from a background where abortion was viewed negatively or their decisions decried. Given this is precisely the attitude fostered by anti-abortion activists, there is a dark irony at play when organisations of this ilk increase the suffering of the very women they claim to help.

Abortion causes cancer

As if abortion were not already an emotive enough issue, elements of the anti-abortion movement have long postulated that women who elect to have an abortion are at a much increased risk of cancer, particularly of the breast. This is absolute unbridled nonsense of the highest order - the abortion-breast-cancer conjecture (ABC) was championed by prominent born-again Christian and anti-abortion campaigner Dr Joel Brind in the early 1990s . This alleged link is not supported by the scientific literature, and the ostensible link between breast cancer and induced abortion is explicitly rejected by the medical community.

But whilst there is scant scientific evidence for the ABC hypothesis, this didn’t stop the administration of George W. Bush altering the National Cancer Institute (NCI) website to suggest that elective abortion may lead to breast cancer in the early 2000s. The medical community reacted with disgust, and the New York Times slammed the rhetorical duplicity of the Bush administration as an “egregious distortion” . The NCI convened a workshop to look at the evidence in February 2003, and concluded that the hypothesis was devoid of any supporting evidence and was political rather than medical in nature. After this stinging rebuke, Brind resorted to hackneyed conspiracy theory, claiming that it was a “corrupt federal agency” and dedicated to “protecting the abortion industry” , as well as directing his ire towards the mainstream medical community .

Claims that abortion increases the risk of cancer are not credible, a position supported by bodies worldwide, including the WHO, the National Cancer Institute, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Yet the ABC myth is still a potent weapon in the arsenal of anti-abortion campaigners. In 2005, Canadian anti-abortion protesters put up posters alleging a cover-up by national cancer bodies. Even today , some US state legislation demands physicians warn women about the risk despite the complete absence of a reason to suspect there is one. As an article in Medical History explains, this continuing focus on the non-existence of a link is the culmination of the “... anti-abortion movement’s efforts, following the violence of the early 1990s, to regain respectability through changing its tactics and rhetoric, which included the adoption of the ABC link as part of its new ‘women-centred’ strategy.”

Abortion reduces fertility

The suggestion that abortion can damage fertility is understandably terrifying, but based on out-dated understanding of abortion techniques. Early surgical abortions tended to be performed using a dilation and curettage (D&C) method, with an inherent but small risk of scarring that could potentially lead to complication. However, this technique is obsolete , replaced with a much safer and effective suction method in the early 1970s. In the 21st century, the WHO recommend a suction-based technique for surgical abortion, rendering the risk to future fertility negligible.

On top of this, across most of Europe the majority of abortions now take place early in the pregnancy , below 9 weeks. Abortions at this early stage are medical in nature, using compounds such as mifepristone (RU-486) which induce miscarriage. There is no evidence that either medical or modern surgical abortion impacts future fertility.

The foetus can feel pain

One of the most inflammatory arguments against abortion is rooted in the assertion that the foetus can feel pain, and that termination is therefore a brutal affair. This is extremely unlikely to be true . A foetus in the early stages of development lacks the developed nervous system and brain to feel pain or even be aware of their surroundings. The neuroanatomical apparatus required for pain and sensation is not complete until about 26 weeks into pregnancy. As the upper limit worldwide for termination is 24 weeks, and the vast majority of pregnancies are terminated well before this (most in the first 9 weeks in the UK), the question of foetal pain is a complete red herring. This is reflected in the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’s report on foetal pain , which concludes “... existing data suggests that cortical processing and therefore foetal perception of pain cannot occur before 24 weeks of gestation”.

Despite its complete lack of veracity, this myth remains a powerful one, and in several US states legislation dictates that doctors can be fined for not warning women that the foetus might experience pain, despite the scientific advice suggesting “proposals to inform women seeking abortions of the potential for pain in foetuses are not supported by evidence. Legal or clinical mandates for interventions to prevent such pain are scientifically unsound and may expose women to inappropriate interventions, risks, and distress.”

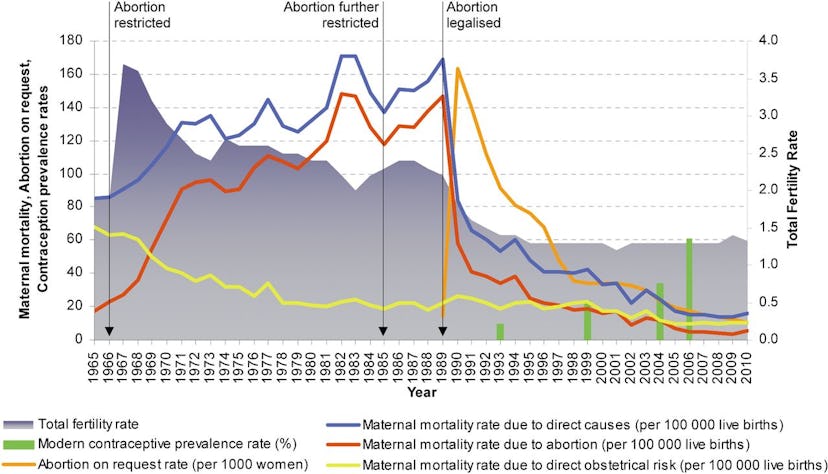

Reducing access to abortion decreases demand for abortion

Anti-abortion campaigners often operate under the implicit assumption that additional hurdles towards obtaining abortions will decrease the number of abortion performed; this is demonstrably false. Reducing access to abortion doesn’t quell the demand for abortion, and making abortion illegal simply makes abortion less safe. Evidence suggests that the abortion rate is approximately equal in countries with and without legal abortion. A 2012 Lancet study found that regions with restricted abortion access have higher rates than more liberal areas, and restricted regions had a much higher incidence of unsafe abortion. Worldwide, about 42 million women a year choose to get abortions, and of these about 21.6 million are unsafe. The consequences of this are grim, resulting in around 47,000 maternal deaths a year . This makes it one of the leading causes of maternal mortality (13%), and can lead to serious complications even when survived.

In the developed world where international travel is affordable, abortion restrictions make even less sense. Ireland, for example, has incredibly restrictive abortion laws, a hangover from the days when it was the last outpost of the Vatican in Europe (a situation I’ve alluded to before ). But whilst the Irish anti-abortion lobbyists boast of Ireland being abortion-free, this sanctimonious gloat ignores that fact that an average of 12 women a day travel to Britain for abortions, with others procuring abortificants online. These extra barriers do not dissuade women from seeking terminations, they merely add emotional and financial obstacles to obtaining them.

These are just some of the claims which surface, hydra-like, when abortion is discussed, and this article is by no means comprehensive. Abortion is an emotive issue, and there is an an entire spectrum of positions which one might subscribe to. And of course, people have every right to hold any opinion they like. But we do not have the right to invent our own facts, and perpetuating debunked fiction helps no one. Such cynical truth-bending is not only intellectually vapid, it compounds an already difficult situation many women face, substituing emotive and sometimes manipulative fabrications in lieu of clear information.

Dr David Robert Grimes is a physicist and cancer researcher at Oxford University. He is a regular Irish Times columnist and blogs at www.davidrobertgrimes.com . He was joint winner of the 2014 John Maddox Prize for Standing up for Science .

- Notes & Theories

Most viewed

Key Arguments From Both Sides of the Abortion Debate

Mark Wilson / Staff / Getty Images

- Reproductive Rights

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.A., English Language and Literature, Well College

Many points come up in the abortion debate . Here's a look at abortion from both sides : 10 arguments for abortion and 10 arguments against abortion, for a total of 20 statements that represent a range of topics as seen from both sides.

Pro-Life Arguments

- Since life begins at conception, abortion is akin to murder as it is the act of taking human life. Abortion is in direct defiance of the commonly accepted idea of the sanctity of human life.

- No civilized society permits one human to intentionally harm or take the life of another human without punishment, and abortion is no different.

- Adoption is a viable alternative to abortion and accomplishes the same result. And with 1.5 million American families wanting to adopt a child, there is no such thing as an unwanted child.

- An abortion can result in medical complications later in life; the risk of ectopic pregnancies is increased if other factors such as smoking are present, the chance of a miscarriage increases in some cases, and pelvic inflammatory disease also increases.

- In the instance of rape and incest, taking certain drugs soon after the event can ensure that a woman will not get pregnant. Abortion punishes the unborn child who committed no crime; instead, it is the perpetrator who should be punished.

- Abortion should not be used as another form of contraception.

- For women who demand complete control of their body, control should include preventing the risk of unwanted pregnancy through the responsible use of contraception or, if that is not possible, through abstinence .

- Many Americans who pay taxes are opposed to abortion, therefore it's morally wrong to use tax dollars to fund abortion.

- Those who choose abortions are often minors or young women with insufficient life experience to understand fully what they are doing. Many have lifelong regrets afterward.

- Abortion sometimes causes psychological pain and stress.

Pro-Choice Arguments

- Nearly all abortions take place in the first trimester when a fetus is attached by the placenta and umbilical cord to the mother. As such, its health is dependent on her health, and cannot be regarded as a separate entity as it cannot exist outside her womb.

- The concept of personhood is different from the concept of human life. Human life occurs at conception, but fertilized eggs used for in vitro fertilization are also human lives and those not implanted are routinely thrown away. Is this murder, and if not, then how is abortion murder?

- Adoption is not an alternative to abortion because it remains the woman's choice whether or not to give her child up for adoption. Statistics show that very few women who give birth choose to give up their babies; less than 3% of White unmarried women and less than 2% of Black unmarried women.

- Abortion is a safe medical procedure. The vast majority of women who have an abortion do so in their first trimester. Medical abortions have a very low risk of serious complications and do not affect a woman's health or future ability to become pregnant or give birth.

- In the case of rape or incest, forcing a woman made pregnant by this violent act would cause further psychological harm to the victim. Often a woman is too afraid to speak up or is unaware she is pregnant, thus the morning after pill is ineffective in these situations.

- Abortion is not used as a form of contraception . Pregnancy can occur even with contraceptive use. Few women who have abortions do not use any form of birth control, and that is due more to individual carelessness than to the availability of abortion.

- The ability of a woman to have control of her body is critical to civil rights. Take away her reproductive choice and you step onto a slippery slope. If the government can force a woman to continue a pregnancy, what about forcing a woman to use contraception or undergo sterilization?

- Taxpayer dollars are used to enable poor women to access the same medical services as rich women, and abortion is one of these services. Funding abortion is no different from funding a war in the Mideast. For those who are opposed, the place to express outrage is in the voting booth.

- Teenagers who become mothers have grim prospects for the future. They are much more likely to leave school; receive inadequate prenatal care; or develop mental health problems.

- Like any other difficult situation, abortion creates stress. Yet the American Psychological Association found that stress was greatest prior to an abortion and that there was no evidence of post-abortion syndrome.

Additional References

- Alvarez, R. Michael, and John Brehm. " American Ambivalence Towards Abortion Policy: Development of a Heteroskedastic Probit Model of Competing Values ." American Journal of Political Science 39.4 (1995): 1055–82. Print.