Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

One way to help big groups of students? Volunteer tutors.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

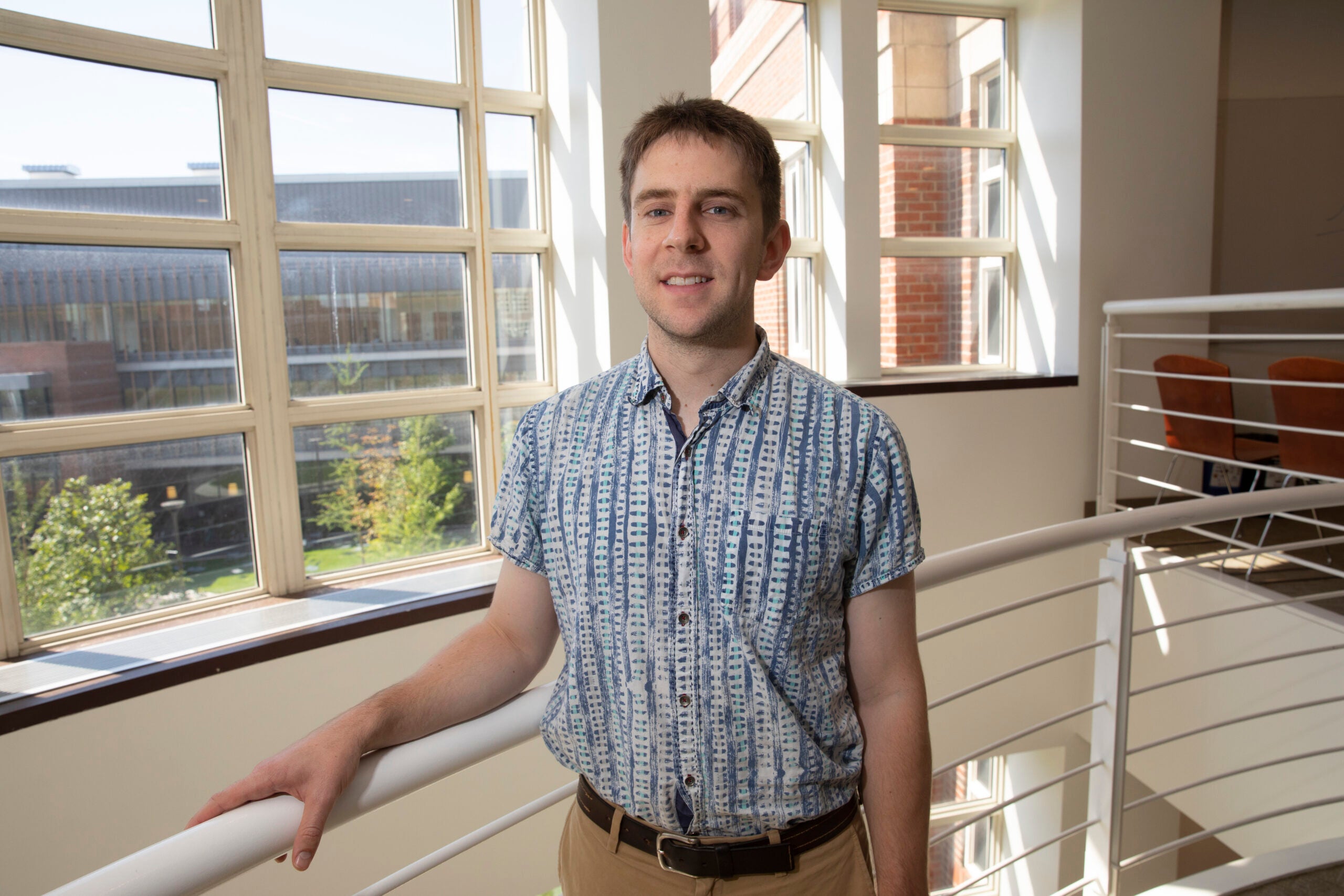

Robert Sampson, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, is one of the researchers studying the link between poverty and social mobility.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Unpacking the power of poverty

Peter Reuell

Harvard Staff Writer

Study picks out key indicators like lead exposure, violence, and incarceration that impact children’s later success

Social scientists have long understood that a child’s environment — in particular growing up in poverty — can have long-lasting effects on their success later in life. What’s less well understood is exactly how.

A new Harvard study is beginning to pry open that black box.

Conducted by Robert Sampson, the Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, and Robert Manduca, a doctoral student in sociology and social policy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the study points to a handful of key indicators, including exposure to high levels of lead, violence, and incarceration as key predictors of children’s later success. The study is described in an April paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“What this paper is trying to do, in a sense, is move beyond the traditional neighborhood indicators people use, like poverty,” Sampson said. “For decades, people have shown poverty to be important … but it doesn’t necessarily tell us what the mechanisms are, and how growing up in poor neighborhoods affects children’s outcomes.”

To explore potential pathways, Manduca and Sampson turned to the income tax records of parents and approximately 230,000 children who lived in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, compiled by Harvard’s Opportunity Atlas project. They integrated these records with survey data collected by the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, measures of violence and incarceration, census indicators, and blood-lead levels for the city’s neighborhoods in the 1990s.

They found that the greater the extent to which poor black male children were exposed to harsh environments, the higher their chances of being incarcerated in adulthood and the lower their adult incomes, measured in their 30s. A similar income pattern also emerged for whites.

Among both black and white girls, the data showed that increased exposure to harsh environments predicted higher rates of teen pregnancy.

Despite the similarity of results along racial lines, Chicago’s segregation means that far more black children were exposed to harsh environments — in terms of toxicity, violence, and incarceration — harmful to their mental and physical health.

“The least-exposed majority-black neighborhoods still had levels of harshness and toxicity greater than the most-exposed majority-white neighborhoods, which plausibly accounts for a substantial portion of the racial disparities in outcomes,” Manduca said.

“It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.” Robert Sampson

“What this paper shows … is the independent predictive power of harsh environments on top of standard variables,” Sampson said. “It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.”

More like this

Cities’ wealth gap is growing, too

Racial and economic disparities intertwined, study finds

The study isn’t solely focused on the mechanisms of how poverty impacts children; it also challenges traditional notions of what remedies might be available.

“This has [various] policy implications,” Sampson said. “Because when you talk about the effects of poverty, that leads to a particular kind of thinking, which has to do with blocked opportunities and the lack of resources in a neighborhood.

“That doesn’t mean resources are unimportant,” he continued, “but what this study suggests is that environmental policy and criminal justice reform can be thought of as social mobility policy. I think that’s provocative, because that’s different than saying it’s just about poverty itself and childhood education and human capital investment, which has traditionally been the conversation.”

The study did suggest that some factors — like community cohesion, social ties, and friendship networks — could act as bulwarks against harsh environments. Many researchers, including Sampson himself, have shown that community cohesion and local organizations can help reduce violence. But Sampson said their ability to do so is limited.

“One of the positive ways to interpret this is that violence is falling in society,” he said. “Research has shown that community organizations are responsible for a good chunk of the drop. But when it comes to what’s affecting the kids themselves, it’s the homicide that happens on the corner, it’s the lead in their environment, it’s the incarceration of their parents that’s having the more proximate, direct influence.”

Going forward, Sampson said he hopes the study will spur similar research in other cities and expand to include other environmental contamination, including so-called brownfield sites.

Ultimately, Sampson said he hopes the study can reveal the myriad ways in which poverty shapes not only the resources that are available for children, but the very world in which they find themselves growing up.

“Poverty is sort of a catchall term,” he said. “The idea here is to peel things back and ask, What does it mean to grow up in a poor white neighborhood? What does it mean to grow up in a poor black neighborhood? What do kids actually experience?

“What it means for a black child on the south side of Chicago is much higher rates of exposure to violence and lead and incarceration, and this has intergenerational consequences,” he continued. “This is particularly important because it provides a way to think about potentially intervening in the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. We don’t typically think about criminal justice reform or environmental policy as social mobility policy. But maybe we should.”

This research was supported with funding from the Project on Race, Class & Cumulative Adversity at Harvard University, the Ford Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation.

Share this article

You might like.

Research finds low-cost, online program yields significant results

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

When should Harvard speak out?

Institutional Voice Working Group provides a roadmap in new report

Had a bad experience meditating? You're not alone.

Altered states of consciousness through yoga, mindfulness more common than thought and mostly beneficial, study finds — though clinicians ill-equipped to help those who struggle

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Poverty and Social Exclusion

Defining, measuring and tackling poverty, latest articles, home page featured articles, buenos aires 2017.

A recent report form the city of Buenos Aires measuring multi-dimensional poverty, using the consensual method, has found that in 2019, 15.3% of households were multi-dimensionally poor, rising to 25.7% for households with children under 18 years of age. The method established will be used to measure nu,ti-dimensional poverty on an ongoing basis.

6th Townsend poverty conference ad

We are now delighted to offer you the presentation slides and video recordings of sessions across the three days, featuring formal presentations, interactive Q&As, networking opportunities and much more.

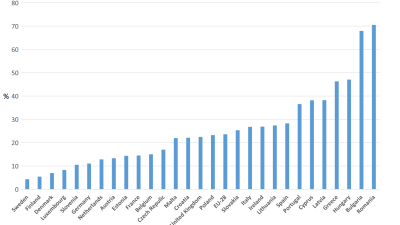

Child deprivation in EU member states, 2018

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Steering Group on Measuring Poverty and Inequality has been tasked with producing a guide on Measuring Social Exclusion which references a lot of our PSE work.

Households in poverty: five case studies

Find out what it really means to miss out on what others take for granted and the deep impact this has on lives and opportunities. The PSE team have filmed with five families living in London, north-east England, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Between them, they represent each of the following key groups vulnerable to poverty:

- single parents on benefits

- the young unemployed

- low-paid workers supporting a family

- adults who are disabled

- single pensioners .

All lack a range of the necessities selected by the public as essential for a minimum living standard in the UK today (see the full list of child and adult necessities in explore the data ). They are all also living on a low income. Using the consensual method for defining poverty that underpins the PSE: UK research, each household is living in poverty.

The following series of short films were recorded between late 2011 and early 2012. The PSE team is very grateful to all the families who are sharing their experiences with us.

Living in poverty featured articles

Featured case studies, the johnsons story.

Renée is 40 and works long hours for low pay to try to provide for her four children, aged 3 to 14, and her 80-year-old mother.

Jennie's story

Jennie is 39 and unemployed. She lives with her three sons, all of whom have disabilities, in Redbridge, outer London.

Marc's Story

Marc is 19 and lives in Redcar in north-east England, a town where there are twelve times as many people claiming job seeker’s allowance as there a

The burden of the downturn that followed the 2008 economic crash was borne by those on the lowest incomes (see Burden of economic downturn taken by the low paid ). In addition, the Coalition government’s austerity measures and changes to the tax and benefit system will impact heavily on those on lowest incomes. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that the net effect will be a rise in both child and adult poverty levels (see UK poverty set to rise in next three years ). The government’s plans include cuts of £18 billion to the welfare budget between 2011 and 2014. While the introduction of Universal Credit should, in principle, increase the benefit entitlements of some households, these improvements are more than offset by other changes to personal taxes and state benefits, such as linking benefits to the Consumer Price Index rather than to the Retail Price Index (see Child and adult poverty set to rise by 2015 ). In addition, Universal Credit risks making certain groups significantly worse off, in particular single working mothers (see Welfare reforms could push 250,000 children deeper into poverty ).

Tweet this page

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

A modest intervention that helps low-income families beat the poverty trap

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

Many low-income families might desire to move into different neighborhoods — places that are safer, quieter, or have more resources in their schools. In fact, not many do relocate. But it turns out they are far more likely to move when someone is on hand to help them do it.

That’s the outcome of a high-profile experiment by a research team including MIT economists, which shows that a modest amount of logistical assistance dramatically increases the likelihood that low-income families will move into neighborhoods providing better economic opportunity.

The randomized field experiment, set in the Seattle area, showed the number of families using vouchers for new housing jumped from 15 percent to 53 percent when they had more information, some financial support, and, most of all, a “navigator” who helped them address logistical challenges.

“The question we were after is really what drives residential segregation,” says Nathaniel Hendren, an MIT economist and co-author of the paper detailing the results. “Is it due to preferences people have, due to having family or jobs close by? Or are there constraints on the search process that make it difficult to move?” As the study clearly shows, he says, “Just pairing people with [navigators] broke down search barriers and created dramatic changes in where they chose to live. This was really just a very deep need in the search process.”

The study’s results have prompted U.S. Congress to twice allocate $25 million in funds allowing eight other U.S. cities to run their own versions of the experiment and measure the impact.

That is partly because the result “represented a bigger treatment effect than any of us had really ever seen,” says Christopher Palmer, an MIT economist and a co-author of the paper. “We spend a little bit of money to help people take down the barriers to moving to these places, and they are happy to do it.”

Having attracted attention when the top-line numbers were first aired in 2019, the study is now in its final form as a peer-reviewed paper, “ Creating Moves to Opportunity: Experimental Evidence on Barriers to Neighborhood Choice ,” published in this month’s issue of the American Economic Review .

The authors are Peter Bergman, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin; Raj Chetty, a professor at Harvard University; Stefanie DeLuca, a professor at Johns Hopkins University; Hendren, a professor in MIT’s Department of Economics; Lawrence F. Katz, a professor at Harvard University; and Palmer, an associate professor in the MIT Sloan School of Management.

New research renews an idea

The study follows other prominent work about the geography of economic mobility. In 2018, Chetty and Hendren released an “Opportunity Atlas” of the U.S., a comprehensive national study showing that, other things being equal, some areas provide greater long-term economic mobility for people who grow up there. The project brought renewed attention to the influence of place on economic outcomes.

The Seattle experiment also follows a 1990s federal government program called Moving to Opportunity, a test in five U.S. cities helping families seek new neighborhoods. That intervention had mixed results : Participants who moved reported better mental health, but there was no apparent change in income levels.

Still, in light of the Opportunity Atlas data, the scholars decided revisit the concept, with a program they call Creating Moves to Opportunity (CMTO). This provides housing vouchers along with a bundle of other things: Short-term financial assistance of about $1,000 on average, more information, and the assistance of a “navigator,” a caseworker who would help troubleshoot issues that families encountered.

The experiment was implemented by the Seattle and King County Housing Authorities, along with MDRC, a nonprofit policy research organization, and J-PAL North America. The latter is one of the arms of the MIT-based Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), a leading center promoting randomized, controlled trials in the social sciences.

The experiment had 712 families in it, and two phases. In the first, all participants were issued housing vouchers worth a little more than $1,500 per month on average, and divided into treatment and control groups. Families in the treatment group also received the CMTO bundle of services, including the navigator.

In this phase, lasting from 2018 to 2019, 53 percent of families in the treatment group used the housing vouchers, while only 15 percent of those in the control group used the vouchers. Families who moved dispersed to 46 different neighborhoods, defined by U.S. Census Bureau tracts, meaning they were not just shifting en masse from one location to one other.

Families who moved were very likely to want to renew their leases, and expressed satisfaction with their new neighborhoods. All told, the program cost about $2,670 per family. Additional research scholars in the group have conducted about changes in income suggest the program’s direct benefits are 2.5 times greater than its costs.

“Our sense is that’s a pretty reasonable return for the money compared to other strategies we have to combat intergenerational poverty,” Hendren says.

Logistical and emotional support

In the second phase of the experiment, lasting from 2019 to 2020, families in a treatment group received individual components of the CMTO support, while the control group again only received the housing vouchers. This way, the researchers could see which parts of the program made the biggest difference. The vast majority of the impact, it turned out, came from receiving the full set of services, especially the “customized” help of navigators.

“What came out of the phase two results was that the customized search assistance was just invaluable to people,” Palmer says. “The barriers are so heterogenous across families.” Some people might have trouble understanding lease terms; others might want guidance about schools; still others might have no experience renting a moving truck.

The research turned up a related phenomenon: In 251 follow-up interviews, families often emphasized that the navigators mattered partly because moving is so stressful.

“When we interviewed people and asked them what was so valuable about that, they said things like, ‘Emotional support,’” Palmer observes. He notes that many families participating in the program are “in distress,” facing serious problems such as the potential for homelessness.

Moving the experiment to other cities

The researchers say they welcome the opportunity to see how the Creating Moves to Opportunity program, or at least localized replications of it, might fare in other places. Congress allocated $25 million in 2019, and then again in 2022, so the program could be tried out in eight metro areas: Cleveland, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Nashville, New Orleans, New York City, Pittsburgh, and Rochester. With the Covid-19 pandemic having slowed the process, officials in those places are still examing the outcomes.

“It’s thrilling to us that Congress has appropriated money to try this program in different cities, so we can verify it wasn’t just that we had really magical and dedicated family navigators in Seattle,” Palmer says. “That would be really useful to test and know.”

Seattle might feature a few particularities that helped the program succeed. As a newer city than many metro areas, it may contain fewer social roadblocks to moving across neighborhoods, for instance.

“It’s conceivable that in Seattle, the barriers for moving to opportunity are more solvable than they might be somewhere else.” Palmer says. “That’s [one reason] to test it in other places.”

Still, the Seattle experiment might translate well even in cities considered to have entrenched neighborhood boundaries and racial divisions. Some of the project’s elements extend earlier work applied in the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program, a voucher plan run by the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership. In Seattle, though, the researchers were able to rigorously test the program as a field experiment, one reason it has seemed viable to try replicate it elsewhere.

“The generalizable lesson is there’s not a deep-seated preference for staying put that’s driving residential segregation,” Hendren says. “I think that’s important to take away from this. Is this the right policy to fight residential segregation? That’s an open question, and we’ll see if this kind of approach generalizes to other cities.”

The research was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, the Surgo Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, and Harvard University.

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Nathaniel Hendren

- Christopher Palmer

- Department of Economics

- MIT Sloan School of Management

Related Topics

- Social sciences

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

Related Articles

How to avoid a “winner’s curse” for social programs

Nathaniel Hendren wants to understand the conditions of opportunity

Moving in circles

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

MIT Corporation elects 10 term members, two life members

Read full story →

Diane Hoskins ’79: How going off-track can lead new SA+P graduates to become integrators of ideas

Chancellor Melissa Nobles’ address to MIT’s undergraduate Class of 2024

Noubar Afeyan PhD ’87 gives new MIT graduates a special assignment

Commencement address by Noubar Afeyan PhD ’87

President Sally Kornbluth’s charge to the Class of 2024

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Mozambique case study shows that poverty is about much more than income

Research Fellow, World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), United Nations University

Anthropologist and senior researcher, Chr. Michelsen Institute

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

United Nations University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

What does it mean to be poor? On the face of it, this may not sound like a very difficult question. In developed countries, almost all official and everyday definitions refer to poverty in income terms. In this sense, low consumption power (income) and poverty are essentially synonymous.

Outside of developed countries, a similar view of poverty frequently gets headlines. In its global comparisons, the World Bank has adopted the (in)famous poverty line of US$1.90 a day . So, people with daily real incomes below this amount form part of the global poor – thankfully, now a diminishing group.

One might dispute exactly how and where such a poverty line should be set. But the idea that being poor means not having an adequate income often seems uncontroversial.

Of course, among academics things are rarely so settled. Between economists, there is disagreement about whether poverty should be measured only in monetary terms. In other areas of social science, there is a tradition of scepticism that suggests standard quantitative definitions of poverty can be misleading .

Representing poverty as a kind of well-defined objective condition, like an infectious disease, focuses attention on the symptoms and immediate consequences of poverty. It risks diverting attention away from the underlying structural causes and diverse experiences of the poor.

Challenging official narratives

In a recent paper we explore contrasting views of well-being in Mozambique. Our interest reflects the country’s controversial track record. From the early 1990s until recently, Mozambique achieved one of the strongest sustained periods of aggregate economic growth of any country. Yet some argue this growth has largely not trickled down, leaving many behind.

Official poverty estimates undertaken by the government are of the classic quantitative or economic kind. Here a set of basic needs is identified and costed. Households consuming goods worth less than the cost of a minimal basket are deemed to be “poor”. Applying this definition, data from national surveys shows consumption poverty has declined over the past two decades at a steady, but not especially rapid, pace.

Today, almost half of all Mozambicans continue to live in absolute poverty. There are also large spatial gaps in well-being. For example, there is much lower poverty in the south of the country, around the capital city, reflecting widening levels of consumption inequality.

To provide perspective on this official narrative, a range of bottom-up studies of poverty , including our own, have been conducted by anthropologists in different parts of the country. These diverge in both form and content from the economic approach.

Indeed, the very starting point of this research has been distinctive. The intention was not to apply a pre-given or conceptually static definition of poverty, from which a count of the poor could proceed. Instead it was to probe local perspectives on well-being, the diverse forms of disadvantage, and the kinds of social relations in which disadvantage arises.

A main finding that emerges from the anthropological work is that we cannot see the poor without seeing the better-off. Local grammars of poverty – namely, the terms used to describe who are better- or worse-off – consistently distinguish between socially marginalised individuals and those with strong local social connections.

Perceptions of deprivation do highlight material deficiencies, such as a lack of food or clothes. But social relationships are vital to cope with vulnerability (shocks) and to facilitate social mobility. Being poor is intimately connected to one’s perceived “position” in a wider society and, through this, one’s scope for upward movement.

Self-reinforcing disadvantage

The anthropological view highlights the complex and often fairly localised ways in which the powerful, sometimes politically-connected, hoard opportunities for development. This reinforces existing divides and limits the social and economic mobility of the most disadvantaged.

For instance, the National District Development Fund in Niassa, Mozambique’s northern province, was seen as a main source of money for investment in (rural) economic activities. Formally, in allocating the funds, priority was to be given to agriculture rather than businesses, women rather than men, and associations rather than individuals.

But we found that the funds had been systematically co-opted by local influentes . These included traditional authorities, male entrepreneurs and the governing party elite through an intricate system of social relations of exclusion and bribes.

Other vignettes from the lives of the poor point to the diverse mechanisms through which disadvantage is reproduced. This is often linked to specific cultural practices that empower certain groups above others. They also point to the self-reinforcing nature of social and economic disadvantage.

For example, we met a single mother who had lost large parts of her harvest to drought two years in a row. She had struggled hard to put all her three children to school, but with no crops to sell and no well-placed family to support her, she could no longer pay the bribes necessary for her children to move up classes. We also encountered instances where people cut themselves off from vital relationships to avoid exposing themselves to the embarrassment of having failed and so as to preserve their dignity.

Making sense of disciplinary divides

How can we make sense of different disciplinary perspectives on poverty? On the one hand, it is tempting to seek some reconciliation. Surely, metrics of social capital or even subjective well-being can be added to existing measures of consumption power to provide a more complete characterisation of the poor? Or perhaps qualitative follow-ups among the consumption poor could be used to add local context?

Certainly, combined qualitative-quantitative approaches to poverty research have become popular and often yield richer insights than any one method on its own. Yet, as we elaborate in our paper, this somewhat misses the point.

There are fundamental philosophical differences between standard quantitative (economic) and qualitative (anthropological) traditions, which do not admit any easy fusion. These include differences in understandings about the form of social reality, what can be known about poverty, and how poverty is produced and reproduced.

For this reason, it is vital to allow separate and diverse perspectives on poverty to flourish. Each methodological approach has distinct strengths, limitations and policy uses.

The economic approach is essential to track economic progress over time on a consistent basis and identify households at greatest risk of consumption poverty (for example, to target social policy). But to uncover – and even resist – the inherently relational and often political ways in which poverty emerges and is reproduced requires a deeper, local, ethnographic touch.

Bringing these different perspectives into a meaningful dialogue with each other remains the next challenge.

- Southern Africa

- Peacebuilding

- Poverty2021

Data Manager

Research Support Officer

Director, Social Policy

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BJPsych Bull

- v.44(5); 2020 Oct

Poverty and mental health: policy, practice and research implications

Lee knifton.

1 Centre for Health Policy, University of Strathclyde, Scotland, and Mental Health Foundation, Scotland and Northern Ireland

Greig Inglis

2 University of West of Scotland, Paisley

Associated Data

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.78.

This article examines the relationship between poverty and mental health problems. We draw on the experience of Glasgow, our home city, which contains some of Western Europe's areas of greatest concentrated poverty and poorest health outcomes. We highlight how mental health problems are related directly to poverty, which in turn underlies wider health inequalities. We then outline implications for psychiatry.

Doctors have often played leading roles in social movements to improve the public's health. These range from the early days of John Snow isolating the role of contaminated water supplies in spreading cholera, through to advocating harm reduction, challenging HIV stigma and, more recently, highlighting the public health catastrophe of mass incarceration in the USA. 1 Almost all examples are rooted in poverty. There is now increasing recognition that mental health problems form the greatest public health challenge of our time, and that the poor bear the greatest burden of mental illness. 2

Our article draws on data from Scotland, and especially Glasgow, which contains some of the areas of greatest need and widest health inequalities in Western Europe. However, the relationship between poverty, social stress and mental health problems is not a new phenomenon and was reported by social psychiatrists half a century ago in Langner & Michael's 1963 New York study 3 and consistently since then. Poverty is both a cause of mental health problems and a consequence. Poverty in childhood and among adults can cause poor mental health through social stresses, stigma and trauma. Equally, mental health problems can lead to impoverishment through loss of employment or underemployment, or fragmentation of social relationships. This vicious cycle is in reality even more complex, as many people with mental health problems move in and out of poverty, living precarious lives.

Poverty and mental health

The mental health of individuals is shaped by the social, environmental and economic conditions in which they are born, grow, work and age. 4 – 7 Poverty and deprivation are key determinants of children's social and behavioural development 8 , 9 and adult mental health. 10 In Scotland, individuals living in the most deprived areas report higher levels of mental ill health and lower levels of well-being than those living in the most affluent areas. In 2018 for example, 23% of men and 26% of women living in the most deprived areas of Scotland reported levels of mental distress indicative of a possible psychiatric disorder, compared with 12 and 16% of men and women living in the least deprived areas. 11 There is also a clear relationship between area deprivation and suicide in Scotland, with suicides three times more likely in the least than in the most deprived areas. 12

Inequalities in mental health emerge early in life and become more pronounced throughout childhood. In one cohort study, 7.3% of 4-year-olds in the most deprived areas of Glasgow were rated by their teacher as displaying ‘abnormal’ social, behavioural and emotional difficulties, compared with only 4.1% in the least deprived areas. By age 7, the gap between these groups had widened substantially: 14.7% of children in the most deprived areas were rated as having ‘abnormal’ difficulties, compared with 3.6% of children in the least deprived. 13 National data from parental ratings of children's behaviour show a similar pattern: at around 4 years of age, 20% of children living in the most deprived areas of Scotland are rated as having ‘borderline’ or ‘abnormal’ levels of difficulties, compared with only 7% living in the least deprived areas. 14

These findings reflect a broader pattern of socioeconomic inequalities in health that is observed internationally. 15 The primary causes of these inequalities are structural differences in socioeconomic groups’ access to economic, social and political resources, which in turn affect health through a range of more immediate environmental, psychological and behavioural processes. 16 , 17 A wide range of risk factors are more prevalent among low income groups for example, including low levels of perceived control 18 and unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and low levels of physical activity, 11 although these are best understood as mechanisms that link the structural causes of inequality to health outcomes. 17

Excess mortality and mental health in Glasgow

Glasgow has some of the highest Scottish rates of income deprivation, working-age adults claiming out of work benefits, and children living in low-income families. 19 Moreover, the city also reports poor mental health, relative to the Scottish average, on a host of indicators, including lower mental well-being and life satisfaction, and higher rates of common mental health problems, prescriptions for anxiety, depression or psychosis, and greater numbers of patients with hospital admissions for psychiatric conditions. 19

These statistics are consistent with Glasgow's overall health profile and high rates of mortality. Life expectancy in Glasgow is the lowest in Scotland. For example, men and women born in Glasgow in 2016–2018 can expect to live 3.6 and 2.7 fewer years respectively than the Scottish average. 20 Within Glasgow, men and women living in the most deprived areas of the city can expect to live 13.5 and 10.7 fewer years respectively than those living in the least deprived areas. 21

The high level of mortality in Glasgow can largely be attributed to the effects of deprivation and poverty in the city, although high levels of excess mortality have also been recorded in Glasgow, meaning a significant level of mortality in excess of that which can be explained by deprivation. For example, premature mortality (deaths under 65 years of age) is 30% higher in Glasgow compared with Liverpool and Manchester, despite the similar levels of deprivation between these cities. 22 Crucially, this excess premature mortality is in large part driven by higher rates of ‘deaths of despair’ 23 in Glasgow, namely deaths from suicide and alcohol- and drug-related causes. 22

It has been proposed that excess mortality in Glasgow can be explained by a number of historical processes that have rendered the city especially vulnerable to the hazardous effects of deprivation and poverty. These include the lagged effects of historically high levels of deprivation and overcrowding; regional policies that saw industry and sections of the population moved out of Glasgow; the nature of urban change in Glasgow during the post-war period and its effects on living conditions and social connections; and local government responses to UK policies during the 1980s. 24 On the last point, Walsh and colleagues 24 describe how the UK government introduced a host of neoliberal policies during this period – including rapid deindustrialisation – that had particularly adverse effects in cities such as Glasgow, Manchester and Liverpool. While Manchester and Liverpool were able to mitigate the negative effects of these national policies to some extent by pursuing urban regeneration and mobilising the political participation of citizens, there were fewer such efforts made in Glasgow, which contributed to the diverging health profiles of the cities.

These researchers have also suggested that this excess mortality may partly reflect an inadequate measurement of deprivation. 24 However, that does not capture the reality of living in poverty. One aspect of this lived experience that may be important is the experience of poverty-based stigma and discrimination. 25 Stigma is a fundamental cause of health inequalities, 26 and international evidence has demonstrated that poverty stigma is associated with poor mental health among low-income groups. 27 Individuals living in socioeconomically deprived areas may also experience ‘spatial’ stigma, which similarly has a range of adverse health effects for residents 28 and, crucially, may be unintentionally exacerbated by media and public health professionals’ reports of regional health inequalities. 29 Given the continued focus on Glasgow's relatively poor health it is possible that the city is more vulnerable to such stigmatising processes. However, we stress that additional research will be required to test whether stigma is an important aspect of the lived reality of poverty, particularly as several psychosocial explanations have already been offered for the excess mortality, with varying levels of supporting evidence. 24 The notion of intersectional stigma is also gaining traction and requires further research.

Understanding the life-course impact of poverty on mental health is also important. Childhood adversity is one mechanism through which poverty and deprivation have an impact on mental health. Adverse childhood experiences, such as exposure to abuse or household dysfunction, are relatively common in the population. Marryat & Frank examined the prevalence of seven adverse childhood experiences among children born in 2004–2005 in Scotland, and found that approximately two-thirds had experienced at least one adverse experience by age 8. 30 Moreover, the prevalence was greatest in low-income households: only 1% of children in the highest-income households had four or more adverse childhood experiences, compared with 10.8% in the lowest-income households. Adverse childhood experiences are also strong predictors of mental health in adulthood: individuals who have experienced at least four are at a considerably greater risk of mental ill health, problematic alcohol use and drug misuse. 31 It has also been suggested that experiences of childhood adversity and complex trauma may contribute to Glasgow's – and Scotland's – excess mortality, particularly that which is attributable to violence, suicide and alcohol and drug-related deaths. 32 The implications are significant for psychiatry. Not only does it offer a broader explanation of causation; it also highlights the importance of supporting early interventions for young people's mental health and supporting the families – including children – of those experiencing mental health problems.

Implications

When faced with the scale of the challenge the response can be daunting. This is especially so at a time when we see increasing poverty and socioeconomic inequalities within our society and challenging political conditions. The complexity and enduring nature of the problems necessitate a multilevel response from psychiatry across practice, policy, advocacy and research, which we explore in this section. We argue that this response should address three broad areas.

Reinvigorate social psychiatry and influence public policy

The demise of social psychiatry in the UK and USA in recent decades has deflected focus away from the social causes and consequences of mental health problems at the very time that social inequalities have been increasing. Now is the time to renew social psychiatry at professional and academic levels. There is considerable scope to form alliances with other areas – especially public mental health agencies and charities. Psychiatry as a profession should support those advocating for progressive public policies to reduce poverty and its impact. If we do not, then, as Phelan and colleagues outline, we will focus only on the intermediate causes of health inequalities, rather than the fundamental causes, and this will ensure that these inequalities persist and are reproduced over time. 33 Activism with those who have consistently highlighted the links between poverty and mental health problems, such as The Equality Trust, may effect change among policy makers.

Tackle intersectional stigma and disadvantage

We must understand, research and tackle stigma in a much more sophisticated way by recognising that mental health stigma does not sit in isolation. We need to understand and address what Turan and colleagues define as intersectional stigma. 34 Intersectional stigma explains the convergence of multiple stigmatised identities that can include ethnicity, gender, sexuality, poverty and health status. This can then magnify the impact on the person's life. In this context, the reality is that you have a much greater chance of getting a mental health problem if you experience poverty. And if you do, then you will likely experience more stigma and discrimination. Its impact on your life will be greater, for example on precarious employment, housing, education and finances. It is harder to recover and the impact on family members may be magnified. Intersectional stigma remains poorly researched and understood, 35 although the health impact of poverty stigma is now emerging as an important issue in studies in Glasgow and elsewhere. 25

Embed poverty-aware practice and commissioning

We conclude with our third idea, to ensure that poverty-aware practice is embedded in services through commissioning, training and teaching. This means that recognising and responding to poverty is part of assessments and care. Income maximisation schemes should be available as an important dimension of healthcare: how to access benefits, manage debt, access local childcare and access support for employment at the earliest stages. This needs to be matched by a major investment in mental health services focused on low-income areas, to address the inverse care law. 36 These principles are already being put into action. For example across Scotland, including Glasgow, several general practices working in the most deprived areas (referred to as Deep End practices) have recently trialled the integration of money advice workers within primary care, which has generated considerable financial gains for patients. 37

About the authors

Lee Knifton is Reader and Co-Director of the Centre for Health Policy at the University of Strathclyde, Scotland, and Director of the Mental Health Foundation, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Greig Inglis is a lecturer in psychology at the University of West of Scotland, Paisley, Scotland.

Author contributions

Both authors were fully and equally involved in the design of the article, drafting the article and making revisions to the final version and are accountable for the integrity of the work.

Declaration of interest

Supplementary material.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 May 2024

Escaping poverty: changing characteristics of China’s rural poverty reduction policy and future trends

- Yunhui Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8824-6109 1 na1 ,

- Yihua Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9089-4172 2 , 3 na1 &

- Zhiying Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2219-5473 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 694 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

66 Accesses

Metrics details

- Development studies

- Social policy

Eliminating poverty is a shared aspiration of people worldwide. This article analyzes 762 rural poverty-related texts promulgated and implemented by the Chinese Government since 1984 using content analysis based on a three-dimensional framework encompassing the time of policy issuance, policy goals, and types of policy instruments. The study outlines the overall landscape and evolutionary context of the policy system. The results show that, during absolute poverty governance, China’s rural poverty governance can be broadly divided into three stages: regional development-oriented poverty alleviation, comprehensive poverty alleviation, and targeted poverty alleviation. Based on the production-oriented welfare model, economic development became the primary goal of poverty alleviation policies, while insufficient attention was given to service support and capacity-building goals. The alleviation of poverty mainly relied on the propulsive force generated by supply-side policy instruments led by the Government and the external driving force generated by environmental policy instruments, with a significant deficiency in the propulsive force produced by demand-side policy instruments. Entering the phase of relative poverty governance, optimizing poverty governance policy instruments requires breaking free from path dependence, following the evolutionary pattern of poverty governance. It involves ensuring that policy instruments support economic development while emphasizing addressing service support and capacity-building goals. It is crucial to increase the frequency of using demand-side policy instruments, stimulate their pulling force on poverty alleviation, and achieve a trend of evolutionary innovation and the collaborative governance of policy instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Does the BRI contribute to poverty reduction in countries along the Belt and Road? A DID-based empirical test

Feminization of poverty: an analysis of multidimensional poverty among rural women in China

The effects of China’s poverty eradication program on sustainability and inequality

Problem statement.

The aspiration to eliminate poverty has been a longstanding societal ideal since ancient times. It represents an intrinsic right for people across the globe in their pursuit of a fulfilling life. The elimination of hunger and poverty, central targets outlined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, also stands as a cornerstone in the development agendas of numerous nations worldwide. Rowntree’s ( 1902 ) early definition of poverty in 1902 classified it as primary and secondary poverty. He argued that a family is in poverty when its total income fails to meet the essential survival needs of its members. This concept is considered the foundation of research into absolute poverty. Essentially, absolute poverty is a physiological concept that explores the link between nutrition and survival (Lister, 2021 ). As economic and social development advances, Peter Townsend contends that absolute poverty overlooks the social and cultural aspects of ‘human need,’ both ‘need’ and ‘poverty’ are products of social construction. “Both ‘need’ and ‘poverty’ are social constructs.” Townsend ( 1979 ) introduced the concept of relative poverty, which signifies exclusion from typical social lifestyles and activities. However, Sen ( 1982 ) proposed in “Poverty and Famine” that the core of poverty lies in the lack of viability rather than mere low income. Alongside research, countries generally categorize poverty into absolute and relative forms. Research shows that most of the world’s impoverished population resides in rural areas (Poverty and Initiative, 2018 ). The capacity of rural people to elevate themselves from poverty holds profound implications for their daily sustenance and global food security. The United Nations and countries worldwide are working to eradicate rural poverty by promoting inclusive growth and sustainable livelihoods.

As an agricultural powerhouse with a massive rural populace, China’s countryside constituted over 80% of its total population in the nascent years following the establishment of the People’s Republic. The rapid economic growth brought about by the reform and opening-up has also exacerbated the development gap between urban and rural areas. The natural and economic factors that have long impeded rural development have become more pronounced, with the hollowing out of the countryside, the aging of the population, the abandonment of infrastructure, environmental degradation, and persistent poverty drawing the Government’s attention. In 1978, 250 million rural residents living under the poverty threshold of 100 RMB annual per capita income represented a 30.7% rural poverty rate Footnote 1 (see Fig. 1 ). Alleviating rural poverty thus emerged as an urgent priority fettering China’s socioeconomic advancement. Since the 1980s, the Chinese Government has embarked on large-scale anti-poverty initiatives in the countryside, promulgating numerous policies that achieved remarkable success in eradicating absolute poverty. From 1985 to 2000, the rural absolute impoverished population rapidly declined from 125 million to 32.09 million, with poverty rates plummeting dramatically from 14.8% to 3.5%. Upon entering the 21st century, both the quantity and incidence of rural absolute poverty persisted in substantial decreases. In 2015, the Central Government further proposed targeted poverty alleviation targets. By 2020, China had accomplished its poverty alleviation targets, eliminating destitution under extant standards.

The rural poor population and poverty incidence rate for 1985–2000 were calculated using the 1978 poverty standard per capita net income of 100 yuan; the rural poor population and poverty incidence rate for 2000–2020 were calculated using the 2010 poverty standard per capita net income of 2300 yuan—data from China Statistical Yearbook.

Governance refers to the process by which a variety of governmental and non-governmental institutions and actors work together to establish conditions for social order and collective action (Stoker, 2012 ). It involves diverse approaches employed by individuals and institutions, both public and private, to manage public affairs. This ongoing process entails cooperative actions, including the implementation of formal institutional arrangements and the agreement on informal arrangements that align with their interests (The Commission on Global Governance, 1995 ). Kooiman and Jentoft ( 2009 ) introduced three essential elements of governance: imagery, instruments, and action. Imagery refers to the rationale behind governance, encompassing vision, judgment, beliefs, and goals, typically grounded in systematic values or knowledge systems. Instruments involve the selection and application of governance methods, serving as intermediaries that connect imagery to action. Action, in turn, represents the practical implementation of these “instruments”. Poverty governance in China constitutes a collaborative effort among the government, market, and society, with a focus on people’s interests, aimed at achieving common prosperity. It encompasses both economic and social dimensions, with the goal of reducing poverty, protecting the rights of the impoverished, and enhancing social equity. In this fight against poverty, which is the largest and most robust in the history of human poverty alleviation, China has taken many original and unique major governance initiatives and accumulated a series of replicable and generalizable experiences in poverty alleviation. However, eliminating absolute poverty does not mean there is no poverty in China, and China is still far from achieving high-quality and high-standard poverty alleviation (Zhou et al., 2020 ). Poverty presents dynamic, multifaceted challenges, including policy-dependent severe behaviors (Wan et al., 2021 ) and the objectivity that relative poverty cannot be entirely eradicated (Hagenaars, 2014 ). With China’s elimination of absolute poverty, the Government’s poverty alleviation focus has shifted from abolishing destitution to alleviating relative hardship (Shen and Li, 2022 ). Given the evolving forms and aims of poverty governance, the period of relative poverty alleviation necessitates continued efforts to prevent regression and enact efficacious policies to mitigate dependence. There is an urgent need to clarify questions about optimal relative poverty governance policies and how they differ from periods of absolute poverty governance. However, current literature exhibits limited systematic investigation into the textual content of absolute rural poverty policies. This study offers an original contribution by analyzing policy texts to reveal changes in China’s poverty reduction policy from the absolute to relative poverty governance periods.

This paper examines the Chinese Government’s rural poverty alleviation policies over time, utilizing content analysis to address two key questions: First, what characterized the Government’s poverty governance model during absolute poverty governance, and what was the operational logic? Second, in the relative poverty governance period, how is pro-poor policy logically related to absolute poverty governance, and what policies should the Government adopt? Answering these questions scientifically can delineate dynamic changes in China’s rural absolute poverty policy instruments, analyze the utility and limitations of existing pro-poor instruments, and inform suggestions to optimize relevant policies moving forward. The research aims to contribute Chinese experiences and insights to the broader cause of international poverty alleviation. Examining the evolution of poverty governance models and policy instruments across periods of absolute and relative poverty has implications for developing effective, context-specific poverty reduction strategies tailored to contemporary implementation environments.

Literature review

Research of the typology of policy instruments.

Policy instruments, sometimes called government or governance instruments, represent the government’s strategies and actions to attain policy targets (Hughes, 2017 ). No universal standard exists for categorizing policy instruments, leading researchers to classify them based on distinct characteristics and targets. Dahl and Lindblom ( 1953 ) have proposed a classification of instruments into regulatory and non-regulatory categories based on their authority attributes; Owen E. Hughes categorizes policy instruments into four distinct groups: government supply, production, subsidies, and regulation, based on the Government’s functions (Hughes, 2017 ); Rothwell and Zegveld categorize policy instruments into three groups: supply, environmental, and demand, considering their intended purposes Howlett and Remash distinguish among voluntary, hybrid, and coercive instruments based on the level of coercion (Howlett et al., 1995 ).

Based on typological analyses and investigations of policy instruments, some scholars have also directed their attention to the factors that influence the choice and utilization of policy instruments to better achieve policy targets in intricate public policy decision-making and implementation contexts. Several studies have emphasized the “fit” of policy instruments, whereby the selection of these instruments is associated with policy targets, the development of state capacity, civil society (Howlett et al., 1995 ), temporal characteristics, field-specific attributes, instrument attributes, and policy strength, all of which impact the effectiveness of policy instrument configurations (Zhang et al., 2022 ). This concept captures the degree of alignment between the selection of policy instruments and specific conditions. In line with this notion, research has conducted empirical analyses of the selection and allocation of policy instruments in specific domains, such as China’s research and development of new energy vehicles (Shao et al., 2021 ), low-carbon city pilot programs (Hong et al., 2021 ), and government attention to the power sector (Cheng and Yang, 2023 ).

Chinese scholars emphasize the role of the Government as a policy solution provider and prefer the “supply-demand-environment” policy instrument classification framework proposed by Rothwell and Zegveld (Rothwell and Zegveld, 1984 ) when conducting policy instrument research and apply it to environmental governance (Liao, 2018 ), energy policy (Li et al., 2023 ; Yang et al., 2021 ), and photovoltaic poverty alleviation (Zhang et al., 2018 ), among other policy area studies.

The selection of policy instruments in poverty alleviation research

In several developing countries, the implementation of measures such as increased financial support, infrastructure development, and enhanced educational levels plays a crucial role in elevating the income of impoverished individuals and stimulating economic growth in disadvantaged regions (Arsani et al., 2020 ; Cross and Neumark, 2021 ; Deepika and Sigi, 2014 ; Mugo and Kilonzo, 2017 ; Page and Pande, 2018 ). This pattern extends to China as well. With the growing focus on policy instrument research, the policy instrument perspective has become increasingly prominent in examining various policy domains (Peters, 2020 ). Nonetheless, the literature concerning inductive analysis utilizing policy instrument typology, grounded in the attributes and characteristics of poverty alleviation, remains exceedingly scarce. Although a substantial portion of research related to poverty alleviation centers on specific policy measures, it remains pertinent.

Promoting industrial development is a paramount strategy in pursuing poverty eradication. As elucidated by Mariara and Kiriti ( 2020 ), the advancement of the industrial sector can bring about more substantial benefits for impoverished communities by facilitating the organization and active participation of rural populations within the industrial framework. It enhances production efficiency and reshapes production dynamics, ultimately culminating in economic development-driven poverty alleviation. Furthermore, Economic development can also be attained through strategic infrastructure development. Zhou et al. ( 2023 ) found that transport infrastructure can significantly enhance economic development, especially public investment in poor areas, and therefore, infrastructure development should be a priority policy option.

Poverty alleviation through education represents an enduring mechanism for sustained poverty reduction. Song ( 2012 ) explored the influence of primary education on China’s labor market, discovering that universal access to primary education yielded a significant reduction in poverty within China, with urban areas particularly benefiting from this effect. Liu et al. ( 2023 ) found that compulsory education more effectively addresses rural poverty than upper-secondary education. The Government should prioritize implementing compulsory education as a long-term policy instrument in rural areas, recognizing its potency in poverty alleviation.

The empowerment of underprivileged individuals can be aptly realized through talent development and expanding employment opportunities. Guo and Wang ( 2021 ) found that rural labor transfer augments the per capita livelihood capital of the remaining population and facilitates the escape from vulnerability and the attainment of stable employment among the impoverished. The significance of government service support for impoverished segments of society should not be underestimated. Yang and Cao ( 2022 ) revealed that augmenting the provision of fundamental public services in rural areas constitutes a crucial strategy for alleviating rural poverty, significantly reducing the incidence of such poverty. Furthermore, Jiang et al. ( 2020 ) uncovered that engaging farmers in underdeveloped and impoverished regions of China in savings and commercial insurance can effectively diminish poverty vulnerability. Deng ( 2019 ) also found that savings and commercial insurance can reduce health expenditures where catastrophic or poverty-inducing levels occur.

The primary approach to poverty alleviation is intricately linked to the formulation and execution of public policies. Government-led initiatives constitute a crucial facet of China’s poverty governance, highlighting the pivotal role of policy instrument selection and allocation. Scholarly investigations have delved into using policy instruments in poverty alleviation, enriching our comprehension of related policies. Nonetheless, research combining policy instruments to scrutinize pro-poor policy evolution remains limited (Zhang et al., 2018 ), with a dearth of comprehensive examinations that draw on policy instrument theory to elucidate pro-poor policy change and optimization recommendations. Consequently, this study commences when the Chinese Government launched large-scale poverty alleviation efforts, focusing on central policy documents closely associated with poverty alleviation between 1984 and 2022. It employs content analysis to conduct text mining of standardized policy documents, dissecting the semantic information conveyed by specific word frequencies and frequencies within the policy texts across various phases. When coupled with coding results, these findings facilitate the categorization and quantitative analysis of policy instruments for poverty alleviation, enabling a comprehensive discussion on their application in poverty governance.

Analytical framework and research methods

Policy text selection.

The sample for this study is primarily obtained from the Peking University-Chinese Laws and Regulations Database. Focus on policy samples regarding poverty alleviation and reduction from 1984 to 2022. First, utilizing the keywords “poverty, poverty reduction, poverty alleviation, help, and special hardship,” examining central laws and regulations, and conducting a full-text search for the timeframe up to November 2, 2022, is necessary. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the policy texts, this study supplemented the selected policies by using the policy repositories on the official websites of the State Council, the State Council’s Bureau of Rural Revitalization, and various government agencies.

Furthermore, this study follows specific policy selection criteria to ensure the representativeness of the selected policy document: first, the government-issued policy texts are heavily linked to poverty alleviation and reduction efforts. To accurately reflect the national Government’s attitudes and actions towards poverty alleviation, the literature must directly outline their measures. The literature’s scope should encompass policy documents from different areas of social development; second, the selected texts mainly include notices, announcements, opinions and methods, decisions, and other policy documents from the central Government and its supervised ministries and commissions. Finally, the study selected 762 policy texts that met its needs.

Policy analysis framework

Policy instruments are one of the most important ways to study and analyze public policies. As the primary means and effective way of government management, policy instruments have an essential impact on the implementation effect of public policies. China’s poverty alleviation policies have been regularly adjusted in response to changing goal circumstances, making the timing of policy implementations a crucial element in tracking the evolution and forecasting future trends of poverty alleviation in the country. The policy target is the core element of public policy, an essential criterion for measuring the degree of response to public problems, and it also determines the means chosen to achieve the target. Hence, this paper examines the trends in China’s anti-poverty policy from three perspectives: policy initiation time, policy targets, and policy instruments.

Time dimension. This paper analyzes the characteristics and influencing factors of China’s poverty alleviation policies in different periods by examining the quantitative trends and evolution of policies over time. Starting from the period of the Chinese Government’s large-scale poverty alleviation efforts, we will examine the development of these policies in a historical context.

Policy goal dimension. In order to sort out China’s anti-poverty policies in a more detailed way, China’s anti-poverty policy targets will be divided into specific categories based on the value of the targets. For a long time, China’s rural poor groups generally have had poor economic conditions, lack of ability, and insufficient support and assistance groups. Given this, this paper divides anti-poverty policy targets into three major categories: economic development category, capacity-building category, and service support category. The economic development category is to improve the infrastructure construction and economic development level of poor areas to drive the poor groups out of poverty and become rich. The service support category provides various services and policy support for developing poor groups, such as employment skills training, policy promotion and interpretation, and information and counseling services for poor groups. Capacity building focuses on the self-development awareness of poor groups and the cultivation and enhancement of their capacities to make up for the shortcomings of development and strengthen the endogenous motivation for poverty alleviation and enrichment.

Policy instruments dimension. Each classification of policy instruments has specific application scenarios, and their combination and comprehensive use aims to maximize effectiveness and synergistic value. However, the policy instrument model Roy Rothwell and Walter Zegveld developed is more comprehensive and operational from a comparative standpoint (Dylander, 1980 ). The analytical framework presents a downgraded view of the complex policy system, focusing on the instruments and measures for operationalizing policy instruments. It highlights the dual effectiveness of intra-dimensional aggregation and inter-dimensional differentiation to aid in identifying each policy instrument’s content and boundaries, thus simplifying the presentation of specific operations. Due to the superiority of this policy model, it has been widely used in policy research in many fields, such as economic development (Eisinger, 1988 ), environmental pollution prevention (Qin and Youhai, 2020 ), and public health care (Yue et al., 2020 ). Concurrently, within the realm of rural poverty governance in China, the backing furnished by both central and local governments for poverty alleviation development, the cultivation of a propitious economic, social, and legal milieu through high-level strategic planning to steer and oversee the trajectory of development in the sphere of poverty alleviation, alongside the emphasis placed on the regulatory functions of central and local governments in shaping poverty alleviation policies in line with market and societal demands to address the genuine requirements of impoverished segments of society, all underscore the pivotal role of government macroeconomic control.

These strategies primarily hinge on the implementation paths meticulously devised by policymakers to attain their designated policy targets. They exhibit a substantial congruence with the internal logic and external utility of supply-side, environment-side, and demand-side policy instruments. Consequently, this approach serves as a valuable analytical instrument within this paper.

Supply-side instruments refer to the Government’s role as a provider, taking the necessary measures to ensure the basic livelihood security of people experiencing poverty and to improve the quality of life and development motivation of people experiencing poverty, specifically including financial inputs, information services, talent training, and infrastructure construction. Demand-side instruments measures refer to the Government’s efforts to stimulate consumption in poverty-stricken areas by promoting poverty alleviation markets, expanding poverty alleviation channels, and promoting poverty alleviation industries, including government purchase, service outsourcing, market shaping, and collaborative exchanges. Environment-side instruments refer to the strong guarantee provided by the Government to create a favorable external environment for poverty alleviation, strengthen the elements of poverty alleviation, and stimulate the endogenous impetus, specifically target planning, regulatory control, tax incentives, and guiding publicity. Examining the policy instruments’ specific measures makes it possible to understand the differentiation of the anti-poverty governance approach, the existing problems, and the direction of future improvement.

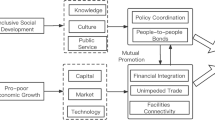

The deployment of these three policy instruments within poverty alleviation reinforces one another, as depicted in Fig. 2 . When viewed through the lens of poverty reduction as a mechanism for propelling economic and social development in impoverished regions, the evolution and advancement of poverty alleviation stem from the interaction and synergy among pushing, pulling, and external forces. In this dynamic, the three policy instruments act as a direct impetus, a direct attractor, and an indirect influencer, respectively, jointly propelling the progression and development of poverty alleviation efforts. These three forces are not static but evolve over different stages of the developmental process, each concentrating on distinct policy targets and modes of poverty management. This study’s central inquiry examines the focal points and attributes of supply-side, demand-side, and environment-side policy instruments throughout China’s rural anti-poverty endeavors.

Schematic illustration of the impact of policy instruments on pro-poor development.

Research methodology

This study employs content analysis to categorize and distill policy texts regarding rural poverty governance in China. Content analysis is a scientific research method that objectively describes observable phenomena and can handle massive amounts of data over extended periods (Riffe et al., 2019 ). Based on specific statistical principles, content analysis can be employed for any type of text, such as policy documents, sounds, images, and videos (Drisko and Maschi, 2016 ). To conduct content analysis, the following vital steps must be followed: defining the study purposes, identifying the unit or sample to be analyzed, determining the categories to be analyzed, identifying and coding the coding elements, testing for reliability, and analyzing and interpreting the results. Policy documents contain explicit content with multiple dimensions and valuable information. The central Government of China holds absolute authority and leadership. Its policies are highly targeted, allowing effective regulation and management of economic and social development and safeguarding people’s well-being. Therefore, we applied the content analysis method to thoroughly analyze 762 anti-poverty policy texts. Through this analysis, we examined the development of China’s anti-poverty policies from three dimensions: policy initiation time, policy targets, and policy instruments.

With the help of NVivo12 software, this paper classified 762 pro-poor policy texts into quantifiable textual analysis units according to the three-level coding principle of “policy text period—type of policy instruments—specific policy content.” According to the type of instruments and the temporal order of the policy, the analysis unit of this paper is coded, and each code is categorized according to the feature words corresponding to the nodes to analyze the use of different policy instruments in terms of the frequency of use of policy instruments. Where “A, B, C” in the code represents the policy instruments type, “1, 2, 3” represents the policy period, and “a, b, c, d” represents the specific policy content. For instance, the document “A-1-d” includes details about the supply-side policy instrument in the “Notice on the National Poverty Alleviation Program of 1987,” released in 1994. The specific policy instruments reference point is “With the support of the state, develop and utilize local resources, develop raw material production, and rely on scientific and technological progress to provide production impetus for the masses to escape from poverty.” Then, following the policy instruments framework, each textual analysis unit is analyzed, and finally, each textual analysis unit is categorized into the corresponding policy instruments (see Table 1 ).

Another coder examined the policy text’s credibility to ensure the study’s validity and reliability. Both parties agreed on disputed issues to establish coding guidelines. The author then recoded for robustness in reverse policy text order, resulting in a final Kappa coefficient of 0.875 (>0.81), indicating high reliability and validity (Richard, 1977 ).

Policy text analysis

Time dimension analysis.

This paper delineates the various stages of policy evolution through a quantitative analysis of 762 policy documents and a comprehensive interpretation of the keywords within these texts. Furthermore, it offers a specific examination of the characteristics of anti-poverty policy evolution at different junctures. It sheds light on the trajectory of the Chinese Government’s efforts in poverty alleviation.

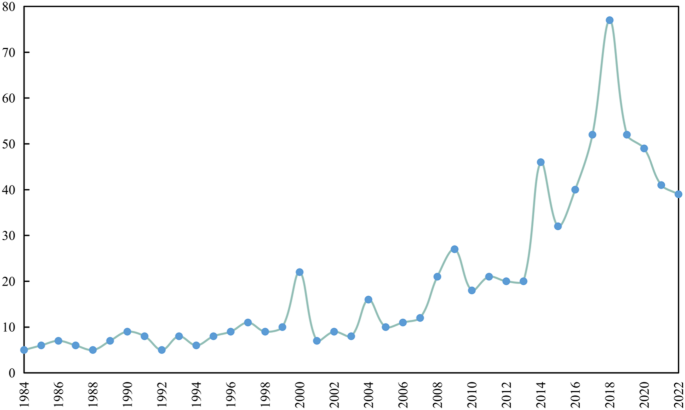

As Fig. 3 illustrates, from 1984 to 2022, there has been a discernible upward trend in introducing anti-poverty policies in rural China, with an exceptionally remarkable surge in recent years. Notably, the number of anti-poverty policies exhibited three peaks in 2000, 2013, and 2018, and the disparity in the number of policies before and after these peaks is quite substantial.

The trends in the distribution of the introduction time of anti-poverty policies in China.

In consideration of the actual context of rural poverty governance and the pivotal time points highlighted in the previous analysis, this paper categorizes the evolution of China’s anti-poverty policy into the following four distinct stages:

The first stage (1984–2000) is characterized as the “Regional Development-Side Poverty Alleviation” phase. During this period, the Chinese Government embarked on large-scale, organized, and meticulously planned rural poverty alleviation and development initiatives in impoverished rural areas. This approach to poverty alleviation was underpinned by a regional development strategy, marking the Government’s proactive involvement in addressing poverty. For instance, in 1986, the Central Government convened the inaugural national conference on poverty alleviation, setting forth the ambitious goal of achieving “Eighty-seven Years of Poverty Alleviation and Attack,” aiming to resolve the fundamental subsistence challenges of 80 million impoverished rural residents by 1990. In 1994, the Central Government issued the first national poverty alleviation and development program, the “National Plan for Poverty Alleviation in 1987.” This program emphasized the importance of focusing on impoverished counties that required assistance. It introduced the concentration of resources and the mobilization of social efforts to ensure the effective implementation of poverty alleviation programs. 109 relevant documents were introduced during this stage, all aimed at achieving the fundamental resolution of subsistence issues for impoverished rural households by 2000.