- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Qualitative Data Collection: What it is + Methods to do it

Qualitative data collection is vital in qualitative research. It helps researchers understand individuals’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in a specific context.

Several methods are used to collect qualitative data, including interviews, surveys, focus groups, and observations. Understanding the various methods used for gathering qualitative data is essential for successful qualitative research.

In this post, we will discuss qualitative data and its collection methods of it.

What is Qualitative Data?

Qualitative data is defined as data that approximates and characterizes. It can be observed and recorded.

This data type is non-numerical in nature. This type of data is collected through methods of observations, one-to-one interviews, conducting focus groups, and similar methods.

Qualitative data in statistics is also known as categorical data – data that can be arranged categorically based on the attributes and properties of a thing or a phenomenon.

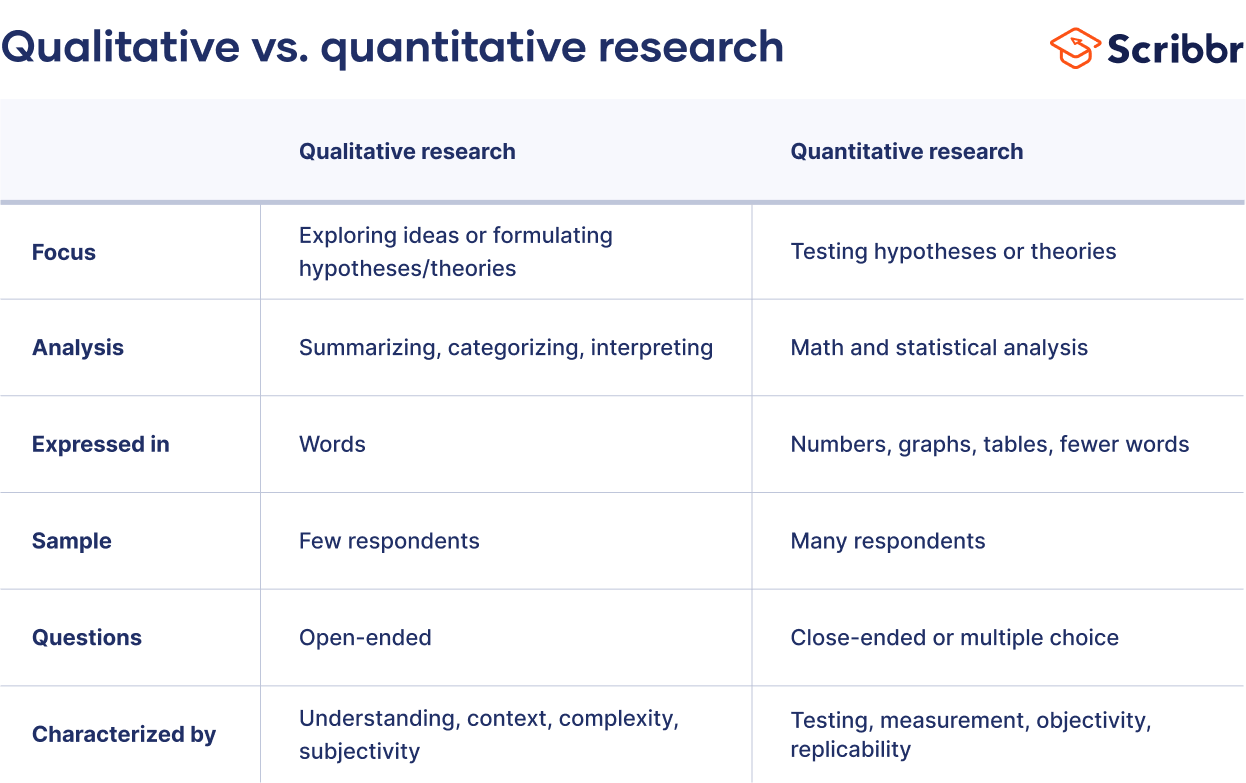

It’s pretty easy to understand the difference between qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data does not include numbers in its definition of traits, whereas quantitative research data is all about numbers.

- The cake is orange, blue, and black in color (qualitative).

- Females have brown, black, blonde, and red hair (qualitative).

What is Qualitative Data Collection?

Qualitative data collection is gathering non-numerical information, such as words, images, and observations, to understand individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and motivations in a specific context. It is an approach used in qualitative research. It seeks to understand social phenomena through in-depth exploration and analysis of people’s perspectives, experiences, and narratives. In statistical analysis , distinguishing between categorical data and numerical data is essential, as categorical data involves distinct categories or labels, while numerical data consists of measurable quantities.

The data collected through qualitative methods are often subjective, open-ended, and unstructured and can provide a rich and nuanced understanding of complex social phenomena.

What is the need for Qualitative Data Collection?

Qualitative research is a type of study carried out with a qualitative approach to understand the exploratory reasons and to assay how and why a specific program or phenomenon operates in the way it is working. A researcher can access numerous qualitative data collection methods that he/she feels are relevant.

Qualitative data collection methods serve the primary purpose of collecting textual data for research and analysis , like the thematic analysis. The collected research data is used to examine:

- Knowledge around a specific issue or a program, experience of people.

- Meaning and relationships.

- Social norms and contextual or cultural practices demean people or impact a cause.

The qualitative data is textual or non-numerical. It covers mostly the images, videos, texts, and written or spoken words by the people. You can opt for any digital data collection methods , like structured or semi-structured surveys, or settle for the traditional approach comprising individual interviews, group discussions, etc.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Effective Qualitative Data Collection Methods

Data at hand leads to a smooth process ensuring all the decisions made are for the business’s betterment. You will be able to make informed decisions only if you have relevant data.

Well! With quality data, you will improve the quality of decision-making. But you will also enhance the quality of the results expected from any endeavor.

Qualitative data collection methods are exploratory. Those are usually more focused on gaining insights and understanding the underlying reasons by digging deeper.

Although quantitative data cannot be quantified, measuring it or analyzing qualitative data might become an issue. Due to the lack of measurability, collection methods of qualitative data are primarily unstructured or structured in rare cases – that too to some extent.

Let’s explore the most common methods used for the collection of qualitative data:

Individual interview

It is one of the most trusted, widely used, and familiar qualitative data collection methods primarily because of its approach. An individual or face-to-face interview is a direct conversation between two people with a specific structure and purpose.

The interview questionnaire is designed in the manner to elicit the interviewee’s knowledge or perspective related to a topic, program, or issue.

At times, depending on the interviewer’s approach, the conversation can be unstructured or informal but focused on understanding the individual’s beliefs, values, understandings, feelings, experiences, and perspectives on an issue.

More often, the interviewer chooses to ask open-ended questions in individual interviews. If the interviewee selects answers from a set of given options, it becomes a structured, fixed response or a biased discussion.

The individual interview is an ideal qualitative data collection method. Particularly when the researchers want highly personalized information from the participants. The individual interview is a notable method if the interviewer decides to probe further and ask follow-up questions to gain more insights.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

Qualitative surveys

To develop an informed hypothesis, many researchers use qualitative research surveys for data collection or to collect a piece of detailed information about a product or an issue. If you want to create questionnaires for collecting textual or qualitative data, then ask more open-ended questions .

To answer such qualitative research questions , the respondent has to write his/her opinion or perspective concerning a specific topic or issue. Unlike other collection methods, online surveys have a wider reach. People can provide you with quality data that is highly credible and valuable.

Paper surveys

Online surveys, focus group discussions.

Focus group discussions can also be considered a type of interview, but it is conducted in a group discussion setting. Usually, the focus group consists of 8 – 10 people (the size may vary depending on the researcher’s requirement). The researchers ensure appropriate space is given to the participants to discuss a topic or issue in a context. The participants are allowed to either agree or disagree with each other’s comments.

With a focused group discussion, researchers know how a particular group of participants perceives the topic. Researchers analyze what participants think of an issue, the range of opinions expressed, and the ideas discussed. The data is collected by noting down the variations or inconsistencies (if any exist) in the participants, especially in terms of belief, experiences, and practice.

The participants of focused group discussions are selected based on the topic or issues for which the researcher wants actionable insights. For example, if the research is about the recovery of college students from drug addiction. The participants have to be college students studying and recovering from drug addiction.

Other parameters such as age, qualification, financial background, social presence, and demographics are also considered, but not primarily, as the group needs diverse participants. Frequently, the qualitative data collected through focused group discussion is more descriptive and highly detailed.

Record keeping

This method uses reliable documents and other sources of information that already exist as the data source. This information can help with the new study. It’s a lot like going to the library. There, you can look through books and other sources to find information that can be used in your research.

Case studies

In this method, data is collected by looking at case studies in detail. This method’s flexibility is shown by the fact that it can be used to analyze both simple and complicated topics. This method’s strength is how well it draws conclusions from a mix of one or more qualitative data collection methods.

Observations

Observation is one of the traditional methods of qualitative data collection. It is used by researchers to gather descriptive analysis data by observing people and their behavior at events or in their natural settings. In this method, the researcher is completely immersed in watching people by taking a participatory stance to take down notes.

There are two main types of observation:

- Covert: In this method, the observer is concealed without letting anyone know that they are being observed. For example, a researcher studying the rituals of a wedding in nomadic tribes must join them as a guest and quietly see everything.

- Overt: In this method, everyone is aware that they are being watched. For example, A researcher or an observer wants to study the wedding rituals of a nomadic tribe. To proceed with the research, the observer or researcher can reveal why he is attending the marriage and even use a video camera to shoot everything around him.

Observation is a useful method of qualitative data collection, especially when you want to study the ongoing process, situation, or reactions on a specific issue related to the people being observed.

When you want to understand people’s behavior or their way of interaction in a particular community or demographic, you can rely on the observation data. Remember, if you fail to get quality data through surveys, qualitative interviews , or group discussions, rely on observation.

It is the best and most trusted collection method of qualitative data to generate qualitative data as it requires equal to no effort from the participants.

Qualitative Data Analysis

You invested time and money acquiring your data, so analyze it. It’s necessary to avoid being in the dark after all your hard work. Qualitative data analysis starts with knowing its two basic techniques, but there are no rules.

- Deductive Approach: The deductive data analysis uses a researcher-defined structure to analyze qualitative data. This method is quick and easy when a researcher knows what the sample population will say.

- Inductive Approach: The inductive technique has no structure or framework. When a researcher knows little about the event, an inductive approach is applied.

Whether you want to analyze qualitative data from a one-on-one interview or a survey, these simple steps will ensure a comprehensive qualitative data analysis.

Step 1: Arrange your Data

After collecting all the data, it is mostly unstructured and sometimes unclear. Arranging your data is the first stage in qualitative data analysis. So, researchers must transcribe data before analyzing it.

Step 2: Organize all your Data

After transforming and arranging your data, the next step is to organize it. One of the best ways to organize the data is to think back to your research goals and then organize the data based on the research questions you asked.

Step 3: Set a Code to the Data Collected

Setting up appropriate codes for the collected data gets you one step closer. Coding is one of the most effective methods for compressing a massive amount of data. It allows you to derive theories from relevant research findings.

Step 4: Validate your Data

Qualitative data analysis success requires data validation. Data validation should be done throughout the research process, not just once. There are two sides to validating data:

- The accuracy of your research design or methods.

- Reliability—how well the approaches deliver accurate data.

Step 5: Concluding the Analysis Process

Finally, conclude your data in a presentable report. The report should describe your research methods, their pros and cons, and research limitations. Your report should include findings, inferences, and future research.

QuestionPro is a comprehensive online survey software that offers a variety of qualitative data analysis tools to help businesses and researchers in making sense of their data. Users can use many different qualitative analysis methods to learn more about their data.

Users of QuestionPro can see their data in different charts and graphs, which makes it easier to spot patterns and trends. It can help researchers and businesses learn more about their target audience, which can lead to better decisions and better results.

Choosing the right software can be tough. Whether you’re a researcher, business leader, or marketer, check out the top 10 qualitative data analysis software for analyzing qualitative data.

Advantages of Qualitative Data Collection

Qualitative data collection has several advantages, including:

- In-depth understanding: It provides in-depth information about attitudes and behaviors, leading to a deeper understanding of the research.

- Flexibility: The methods allow researchers to modify questions or change direction if new information emerges.

- Contextualization: Qualitative research data is in context, which helps to provide a deep understanding of the experiences and perspectives of individuals.

- Rich data: It often produces rich, detailed, and nuanced information that cannot capture through numerical data.

- Engagement: The methods, such as interviews and focus groups, involve active meetings with participants, leading to a deeper understanding.

- Multiple perspectives: This can provide various views and a rich array of voices, adding depth and complexity.

- Realistic setting: It often occurs in realistic settings, providing more authentic experiences and behaviors.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Qualitative research is one of the best methods for identifying the behavior and patterns governing social conditions, issues, or topics. It spans a step ahead of quantitative data as it fails to explain the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon, but qualitative data quickly does.

Qualitative research is one of the best tools to identify behaviors and patterns governing social conditions. It goes a step beyond quantitative data by providing the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon that cannot be explored quantitatively.

With QuestionPro, you can use it for qualitative data collection through various methods. Using Our robust suite correctly, you can enhance the quality and integrity of the collected data.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Data Discovery: What it is, Importance, Process + Use Cases

Sep 16, 2024

Competitive Insights : Importance, How to Get + Usage

Sep 13, 2024

Participant Engagement: Strategies + Improving Interaction

Sep 12, 2024

Employee Recognition Programs: A Complete Guide

Sep 11, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on 4 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 30 January 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analysing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, and history.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organisation?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography, action research, phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasise different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organisations to understand their cultures. | |

| Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. | |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves ‘instruments’ in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analysing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organise your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorise your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analysing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasise different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorise common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analysing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analysing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalisability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalisable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labour-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organisation to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, January 30). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 16 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/introduction-to-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

UpMetrics Blog

Read the latest expert insights, trends, and best practices around impact measurement and leveraging actionable data to drive meaningful change.

8 Essential Qualitative Data Collection Methods

Qualitative data methods allow you to dive deep into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

British mathematician and marketing mastermind Clive Humby once famously stated that “Data is the new oil.” He has a point. Without data, nonprofit organizations are left second-guessing what their clients and supporters think, how their brand compares to others in the market, whether their messaging is on-point, how their campaigns are performing, where improvements can be made, and how overall results can be optimized.

There are two primary data collection methodologies: qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection. At UpMetrics, we believe that just relying on quantitative, static data is no longer an option to drive effective impact. In this guide, we’ll focus on qualitative data collection methods and how they can help you gather, analyze, and collate information that can help drive your organization forward.

What is Qualitative Data?

Data collection in qualitative research focuses on gathering contextual information. Unlike quantitative data, which focuses primarily on numbers to establish ‘how many’ or ‘how much,’ qualitative data collection tools allow you to assess the ‘why’s’ and ‘how’s’ behind those statistics. This is vital for nonprofits as it enables organizations to determine:

- Existing knowledge surrounding a particular issue.

- How social norms and cultural practices impact a cause.

- What kind of experiences and interactions people have with your brand.

- Trends in the way people change their opinions.

- Whether meaningful relationships are being established between all parties.

In short, qualitative data collection methods collect perceptual and descriptive information that helps you understand the reasoning and motivation behind particular reactions and behaviors. For that reason, qualitative data methods are usually non-numerical and center around spoken and written words rather than data extrapolated from a spreadsheet or report.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data

Quantitative and qualitative data represent both sides of the same coin. There will always be some degree of debate over the importance of quantitative vs. qualitative research, data, and collection. However, successful organizations should strive to achieve a balance between the two.

Organizations can track their performance by collecting quantitative data based on metrics including dollars raised, membership growth, number of people served, overhead costs, etc. This is all essential information to have. However, the data lacks value without the additional details provided by qualitative research because it doesn’t tell you anything about how your target audience thinks, feels, and acts.

Qualitative data collection is particularly relevant in the nonprofit sector as the relationships people have with the causes they support are fundamentally personal and cannot be expressed numerically. Qualitative data methods allow you to deep dive into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

8 Types of Qualitative Data Collection Methods

As we have firmly established the need for qualitative data, it’s time to answer the next big question: how to collect qualitative data.

Here is a list of the most common qualitative data collection methods. You don’t need to use them all in your quest for gathering information. However, a foundational understanding of each will help you refine your research strategy and select the methods that are likely to provide the highest quality business intelligence for your organization.

1. Interviews

One-on-one interviews are one of the most commonly used data collection methods in qualitative research because they allow you to collect highly personalized information directly from the source. Interviews explore participants' opinions, motivations, beliefs, and experiences and are particularly beneficial in gathering data on sensitive topics because respondents are more likely to open up in a one-on-one setting than in a group environment.

Interviews can be conducted in person or by online video call. Typically, they are separated into three main categories:

- Structured Interviews - Structured interviews consist of predetermined (and usually closed) questions with little or no variation between interviewees. There is generally no scope for elaboration or follow-up questions, making them better suited to researching specific topics.

- Unstructured Interviews – Conversely, unstructured interviews have little to no organization or preconceived topics and include predominantly open questions. As a result, the discussion will flow in completely different directions for each participant and can be very time-consuming. For this reason, unstructured interviews are generally only used when little is known about the subject area or when in-depth responses are required on a particular subject.

- Semi-Structured Interviews – A combination of the two interviews mentioned above, semi-structured interviews comprise several scripted questions but allow both interviewers and interviewees the opportunity to diverge and elaborate so more in-depth reasoning can be explored.

While each approach has its merits, semi-structured interviews are typically favored as a way to uncover detailed information in a timely manner while highlighting areas that may not have been considered relevant in previous research efforts. Whichever type of interview you utilize, participants must be fully briefed on the format, purpose, and what you hope to achieve. With that in mind, here are a few tips to follow:

- Give them an idea of how long the interview will last

- If you plan to record the conversation, ask permission beforehand

- Provide the opportunity to ask questions before you begin and again at the end.

2. Focus Groups

Focus groups share much in common with less structured interviews, the key difference being that the goal is to collect data from several participants simultaneously. Focus groups are effective in gathering information based on collective views and are one of the most popular data collection instruments in qualitative research when a series of one-on-one interviews proves too time-consuming or difficult to schedule.

Focus groups are most helpful in gathering data from a specific group of people, such as donors or clients from a particular demographic. The discussion should be focused on a specific topic and carefully guided and moderated by the researcher to determine participant views and the reasoning behind them.

Feedback in a group setting often provides richer data than one-on-one interviews, as participants are generally more open to sharing when others are sharing too. Plus, input from one participant may spark insight from another that would not have come to light otherwise. However, here are a couple of potential downsides:

- If participants are uneasy with each other, they may not be at ease openly discussing their feelings or opinions.

- If the topic is not of interest or does not focus on something participants are willing to discuss, data will lack value.

The size of the group should be carefully considered. Research suggests over-recruiting to avoid risking cancellation, even if that means moderators have to manage more participants than anticipated. The optimum group size is generally between six and eight for all participants to be granted ample opportunity to speak. However, focus groups can still be successful with as few as three or as many as fourteen participants.

3. Observation

Observation is one of the ultimate data collection tools in qualitative research for gathering information through subjective methods. A technique used frequently by modern-day marketers, qualitative observation is also favored by psychologists, sociologists, behavior specialists, and product developers.

The primary purpose is to gather information that cannot be measured or easily quantified. It involves virtually no cognitive input from the participants themselves. Researchers simply observe subjects and their reactions during the course of their regular routines and take detailed field notes from which to draw information.

Observational techniques vary in terms of contact with participants. Some qualitative observations involve the complete immersion of the researcher over a period of time. For example, attending the same church, clinic, society meetings, or volunteer organizations as the participants. Under these circumstances, researchers will likely witness the most natural responses rather than relying on behaviors elicited in a simulated environment. Depending on the study and intended purpose, they may or may not choose to identify themselves as a researcher during the process.

Regardless of whether you take a covert or overt approach, remember that because each researcher is as unique as every participant, they will have their own inherent biases. Therefore, observational studies are prone to a high degree of subjectivity. For example, one researcher’s notes on the behavior of donors at a society event may vary wildly from the next. So, each qualitative observational study is unique in its own right.

4. Open-Ended Surveys and Questionnaires

Open-ended surveys and questionnaires allow organizations to collect views and opinions from respondents without meeting in person. They can be sent electronically and are considered one of the most cost-effective qualitative data collection tools. Unlike closed question surveys and questionnaires that limit responses, open-ended questions allow participants to provide lengthy and in-depth answers from which you can extrapolate large amounts of data.

The findings of open-ended surveys and questionnaires can be challenging to analyze because there are no uniform answers. A popular approach is to record sentiments as positive, negative, and neutral and further dissect the data from there. To gather the best business intelligence, carefully consider the presentation and length of your survey or questionnaire. Here is a list of essential considerations:

- Number of questions : Too many can feel intimidating, and you’ll experience low response rates. Too few can feel like it’s not worth the effort. Plus, the data you collect will have limited actionability. The consensus on how many questions to include varies depending on which sources you consult. However, 5-10 is a good benchmark for shorter surveys that take around 10 minutes and 15-20 for longer surveys that take approximately 20 minutes to complete.

- Personalization: Your response rate will be higher if you greet patients by name and demonstrate a historical knowledge of their interactions with your brand.

- Visual elements : Recipients can be easily turned off by poorly designed questionnaires. Besides, it’s a good idea to customize your survey template to include brand assets like colors, logos, and fonts to increase brand loyalty and recognition.

- Reminders : Sending survey reminders is the best way to improve your response rate. You don’t want to hassle respondents too soon, nor do you want to wait too long. Sending a follow-up at around the 3-7 mark is usually the most effective.

- Building a feedback loop : Adding a tick-box requesting permission for further follow-ups is a proven way to elicit more in-depth feedback. Plus, it gives respondents a voice and makes their opinion feel valued.

5. Case Studies

Case studies are often a preferred method of qualitative research data collection for organizations looking to generate incredibly detailed and in-depth information on a specific topic. Case studies are usually a deep dive into one specific case or a small number of related cases. As a result, they work well for organizations that operate in niche markets.

Case studies typically involve several qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, surveys, and observation. The idea is to cast a wide net to obtain a rich picture comprising multiple views and responses. When conducted correctly, case studies can generate vast bodies of data that can be used to improve processes at every client and donor touchpoint.

The best way to demonstrate the purpose and value of a case study is with an example: A Longitudinal Qualitative Case Study of Change in Nonprofits – Suggesting A New Approach to the Management of Change .

The researchers established that while change management had already been widely researched in commercial and for-profit settings, little reference had been made to the unique challenges in the nonprofit sector. The case study examined change and change management at a single nonprofit hospital from the viewpoint of all those who witnessed and experienced it. To gain a holistic view of the entire process, research included interviews with employees at every level, from nursing staff to CEOs, to identify the direct and indirect impacts of change. Results were collated based on detailed responses to questions about preparing for change, experiencing change, and reflecting on change.

6. Text Analysis

Text analysis has long been used in political and social science spheres to gain a deeper understanding of behaviors and motivations by gathering insights from human-written texts. By analyzing the flow of text and word choices, relationships between other texts written by the same participant can be identified so that researchers can draw conclusions about the mindset of their target audience. Though technically a qualitative data collection method, the process can involve some quantitative elements, as often, computer systems are used to scan, extract, and categorize information to identify patterns, sentiments, and other actionable information.

You might be wondering how to collect written information from your research subjects. There are many different options, and approaches can be overt or covert.

Examples include:

- Investigating how often certain cause-related words and phrases are used in client and donor social media posts.

- Asking participants to keep a journal or diary.

- Analyzing existing interview transcripts and survey responses.

By conducting a detailed analysis, you can connect elements of written text to specific issues, causes, and cultural perspectives, allowing you to draw empirical conclusions about personal views, behaviors, and social relations. With small studies focusing on participants' subjective experience on a specific theme or topic, diaries and journals can be particularly effective in building an understanding of underlying thought processes and beliefs.

7. Audio and Video Recordings

Similarly to how data is collected from a person’s writing, you can draw valuable conclusions by observing someone’s speech patterns, intonation, and body language when you watch or listen to them interact in a particular environment or within specific surroundings.

Video and audio recordings are helpful in circumstances where researchers predict better results by having participants be in the moment rather than having them think about what to write down or how to formulate an answer to an email survey.

You can collect audio and video materials for analysis from multiple sources, including:

- Previously filmed records of events

- Interview recordings

- Video diaries

Utilizing audio and video footage allows researchers to revisit key themes, and it's possible to use the same analytical sources in multiple studies – providing that the scope of the original recording is comprehensive enough to cover the intended theme in adequate depth.

It can be challenging to present the results of audio and video analysis in a quantifiable form that helps you gauge campaign and market performance. However, results can be used to effectively design concept maps that extrapolate central themes that arise consistently. Concept Mapping offers organizations a visual representation of thought patterns and how ideas link together between different demographics. This data can prove invaluable in identifying areas for improvement and change across entire projects and organizational processes.

8. Hybrid Methodologies

It is often possible to utilize data collection methods in qualitative research that provide quantitative facts and figures. So if you’re struggling to settle on an approach, a hybrid methodology may be a good starting point. For instance, a survey format that asks closed and open questions can collect and collate quantitative and qualitative data.

A Net Promoter Score (NPS) survey is a great example. The primary goal of an NPS survey is to collect quantitative ratings of various factors on a score of 1-10. However, they also utilize open-ended follow-up questions to collect qualitative data that helps identify insights into the trends, thought processes, reasoning, and behaviors behind the initial scoring.

Collect and Collate Actionable Data with UpMetrics

Most nonprofits believe data is strategically important. It has been statistically proven that organizations with advanced data insights achieve their missions more efficiently. Yet, studies show that despite 90% of organizations collecting data, only 5% believe internal decision-making is data-driven. At UpMetrics, we’re here to help you change that.

Unlock your organization's impact potential with an Impact Framework UpMetrics' next generation Impact Measurement and Management platform makes measuring, optimizing, and showcasing your organization's impact easier than ever before.

As part of our IMM Suite's free Starter Plan, we're excited to offer mission-driven organizations no-cost access to our new Impact Framework Builder functionality so that you can define how you're thinking about impact tied to your mission and vision.

Disrupting Tradition

Download our case study to discover how the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation is using a Learning Mindset to Support Grantees in Measuring Impact

Techniques of Qualitative Data Collection

- First Online: 10 June 2024

Cite this chapter

- Rashina Hoda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5147-8096 2

In this chapter, we will learn about two groups of data collection techniques: custom-data and existing-data collection. Then we will delve into the details of popular collection techniques such as pre-interview questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and observations. We will look into other sources and collection techniques such as focus groups, surveys, recordings, texts, social media, artefacts, data mining, and immersive experiences in extended realities. Researchers will benefit from reading this chapter in conjunction with the Basics of Qualitative Data Collection , Qualitative Data Preparation and Filtering , and Socio-technical Grounded Theory for Qualitative Data Analysis chapters. Collectively, they cover socio-technical grounded theory’s Basic Stage.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Begel, A., DeLine, R., & Zimmermann, T. (2010). Social media for software engineering. In Proceedings of the FSE/SDP workshop on Future of software engineering research (pp. 33–38).

Google Scholar

Berntzen, M., Hoda, R., Moe, N. B., & Stray, V. (2022). A taxonomy of inter-team coordination mechanisms in large-scale agile. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 49 (2), 699–718.

Article Google Scholar

Berntzen, M., Stray, V., Moe, N. B., & Hoda, R. (2023). Responding to change over time: A longitudinal case study on changes in coordination mechanisms in large-scale agile. Empirical Software Engineering, 28 (5), 114.

Charmaz, K., Belgrave, L., et al. (2012). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, 2 , 347–365.

Gold, N. E., & Krinke, J. (2022). Ethics in the mining of software repositories. Empirical Software Engineering, 27 (1), 17.

Gonzalez-Barahona, J. (2020). Mining software repositories while respecting privacy. In Mining Software Repositories Tutorial . https://2020. msrconf. org/details/msr-2020-Education/1/Mining-Software-Repositories-While-Respect ing-Privacy

Graetsch, U. M., Khalajzadeh, H., Shahin, M., Hoda, R., & Grundy, J. (2023). Dealing with data challenges when delivering data-intensive software solutions. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering . https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2023.3291003

Hine, C. (2008). Virtual ethnography: Modes, varieties, affordances. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods (pp. 257–270).

Hoda, R., Noble, J., & Marshall, S. (2012). Self-organizing roles on agile software development teams. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 39 (3), 422–444.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! the challenges and opportunities of social media. Business horizons, 53 (1), 59–68.

LeCompte, M. D., & Goetz, J. P. (1982). Problems of reliability and validity in ethnographic research, Review of Educational Research, 52 (1), 31–60.

Liu, M., Peng, X., Marcus, A., Xing, S., Treude, C., & Zhao, C. (2021). API-related developer information needs in stack overflow. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 48 (11), 4485–4500.

Madampe, K., Hoda, R., & Singh, P. (2020). Towards understanding emotional response to requirements changes in agile teams. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: New Ideas and Emerging Results (pp. 37–40).

Masood, Z., Hoda, R., & Blincoe, K. (2020a). How agile teams make self-assignment work: A grounded theory study, Empirical Software Engineering, 25 , 4962–5005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-020-09876-x

Masood, Z., Hoda, R., Blincoe, K. (2020b). Real world Scrum: A grounded theory of variations in practice. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 48 (5), 1579–1591.

McCarney, R., Warner, J., Iliffe, S., Van Haselen, R., Griffin, M., & Fisher, P. (2007). The hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7 (1), 30.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society (Vol. 111). Chicago University of Chicago Press.

Monahan, T., & Fisher, J. A. (2010). Benefits of ‘observer effects’: Lessons from the field. Qualitative Research, 10 (3), 357–376.

O’Connor, R. (2012). Using grounded theory coding mechanisms to analyze case study and focus group data in the context of software process research. In Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (pp. 256–270). IGI Global.

Shastri, Y., Hoda, R., & Amor, R. (2017). Understanding the roles of the manager in agile project management. In Proceedings of the 10th Innovations in Software Engineering Conference (pp. 45–55).

Storey, M.-A., Treude, C., van Deursen, A., & Cheng, L.-T. (2010). The impact of social media on software engineering practices and tools. In Proceedings of the FSE/SDP workshop on Future of software engineering research (pp. 359–364).

Treude, C., Barzilay, O., & Storey, M.-A. (2011). How do programmers ask and answer questions on the web? (NIER track). In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Software Engineering (pp. 804–807).

Wolfe, A. (1991). Mind, self, society, and computer: Artificial intelligence and the sociology of mind. American Journal of Sociology, 96 (5), 1073–1096.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Rashina Hoda

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Hoda, R. (2024). Techniques of Qualitative Data Collection. In: Qualitative Research with Socio-Technical Grounded Theory. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60533-8_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60533-8_8

Published : 10 June 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-60532-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-60533-8

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

779k Accesses

369 Citations

90 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

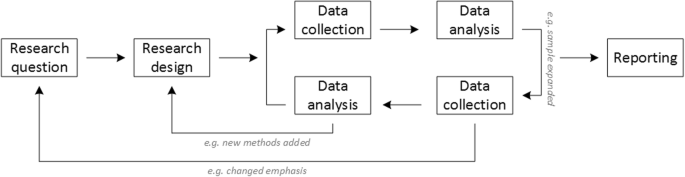

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

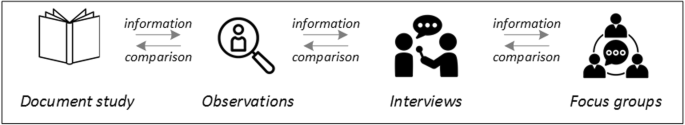

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

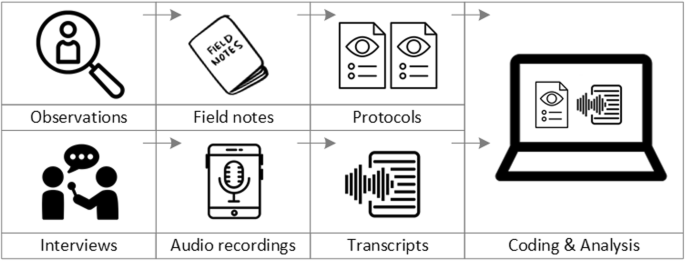

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

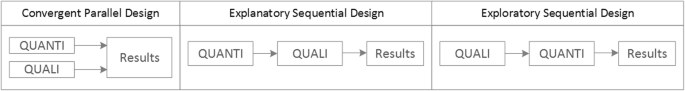

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].