- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Historical Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- History by Period

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Intellectual History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Language Teaching and Learning

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Christianity

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Browse content in Law

- Company and Commercial Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Criminal Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Legal System and Practice

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Browse content in Economics

- Economic History

- Browse content in Education

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Browse content in Politics

- Asian Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- European Union

- Human Rights and Politics

- International Relations

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Public Policy

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Sociology of Religion

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

1 From Law and Technology to Law as Technology

- Published: September 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter argues that law can be seen as technological when, ironically, law is called to respond to technological change. Through a focus on the legal responses to cloning, it is shown that the called-for laws were responding to visions of cloning futures directly sourced from science fiction. Having located these legal acts within science fiction, the essential elements of this future-oriented process – monstrous technology, vulnerable humanity and saving law – can be seen. This will be identified as the ‘Frankenstein myth.’ What is revealed is that science fiction holds the technical and legal together at the level of substantive dreaming and also at the level of basic commitments. The irony intrudes at this point. This saving law that can determine the future has a particular character. It is a species of pure power, manufactured through procedure in the present to determine the future. It appears to have the same characteristics that have been ascribed to technology. With this the categories established by the Frankenstein myth of ‘technology’, ‘humanity’ and ‘law’ seem to be imploded. What is glimpsed is the singularity of technical legality.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Legal Technology: Assessment of the Legal Tech Industry’s Potential

- Open access

- Published: 28 January 2022

- Volume 14 , pages 595–619, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Karolina Mania ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9063-7563 1

9403 Accesses

7 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in the sector of legal services has resulted in the emergence of a new category of services known as legal technology (legal tech). This article aims at defining the current state of research concerning the matter, confirming its interdisciplinary nature and examining the level of its popularity. The strategy assumed for the article has influenced the order and sequence of the topics covered starting from an introduction to legal technology together with analysis of the context of the definition of the term (legal tech) (“ Introduction ” section), through a detailed discussion of the methodology of systematic literature review, its results and an appraisal of the popularity of the notions (“ Materials and Methods ” and “ Bibliometric Analysis ” sections), the application of the thematic analysis method (“ Thematic Analysis of the Reference Repository ” section), Google Trends analysis (“ Analysis of the Popularity of the Terms ‘Legal Technology’ or ‘Legal Tech’ (Google Trends) ” section), and finally the conclusions (“ Conclusions ” section). The research methodology covers a systematic literature review, quantitative bibliometric analysis, the thematic analysis method, and — complementarily — popularity analysis performed using the Google Trends analytical tool. The article confirms the multidisciplinary nature of legal technology as a subject matter, indicating the thematic categories corresponding with the notion under investigation. It contains a description of the geographical segmentation and difference in that regard at a global level. The author has verified the presence of publications on legal technology and shown that the future of the legal services sector lies in an interdisciplinary juxtaposition of the classic legal sciences with entirely new areas, i.e. IT, artificial intelligence, and data analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

Drishti Yadav

Bridging Digital Divides: a Literature Review and Research Agenda for Information Systems Research

Polyxeni Vassilakopoulou & Eli Hustad

Research Methods for Public Policy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The impact exerted by information and communication technologies on individual branches of the economy lets one assume that the legal services sector is also subject to change resulting from the common use of ICT tools. Footnote 1 Legal services covering a range of components such as legal consultancy, representing the client in court and out-of-court proceedings, producing legal documentation, and other unclassified activities performed by applying specialist legal knowledge, are subject to the process of digital transformation (Hartung et al., 2018 ). Online legal advice, case management systems, electronic arbitration proceedings, or AI-based document analysis are already commonplace in law firms and legal departments across the world (Abramovsky & Griffith, 2006 ).

Using advanced IT solutions to attain the objectives of both effective provision of legal services and representing the interest of law firms and legal departments has triggered the emergence of a new legal services sector, i.e. legal technology (abridged to legal tech) (Katsh, 1996 ). Footnote 2 The term covers all information and communication technologies used in the legal service sector such as contract management systems or document management systems, systems of e-discovery in litigation, or judicial predictive systems (Fenwick et al., 2019 ).

The potential of using IT solution dedicated to the legal industry is reflected in business reports, suggesting that in 2018 legal tech investment reached USD 1 billion, that is almost four times more than in the preceding year (USD 233 million in 2017). Footnote 3 Correlating that data with a growing value of the global market of legal services estimated to reach a record-breaking USD 1.011 trillion in 2021, up from USD 849 billion in 2017, USD 886 billion in 2018, and USD 925 billion in 2019, one could conclude that the future of the legal services sector is moving towards a technological revolution entailing a business model change, process automation, and employment reduction (Bourke et al., 2020 ). Footnote 4

Although that data suggest growing trends as regards the value of the global legal tech market, the list of companies in the sector developed by a research project of Stanford University (USA) called Stanford Law School’s LegalTech Index, in November 2019 there existed (globally) a mere (or as many as?) 1249 entities (firms) offering technologies discussed here dedicated to the legal sector. Footnote 5 A relatively limited number of players generating that market’s great value makes one wonder and want to embark on advanced analytical studies that would allow for its realistic assessment (Wang, 2007 ).

The sector has rapidly grown over the last few years, which can be seen in an increasing number of publications. Footnote 6 At the same time, the literature lacks a systematic review investigating the bibliometric and thematic analysis of the term (Snyder, 2019 ). It is necessary to consider the level of popularity of the topic, its potential, and interdisciplinary character. That is why the first step towards an in-depth analysis of any topic must involve becoming familiar with the current state of knowledge, which translates into the need to systematically review academic literature (Leith, 2000 ).

The paper offers original contributions to the current literature. This contribution aims at performing the first step in research devoted to the legal tech industry, starting from just systematic literature review that would result in a preliminary assessment of the potential of the matter at hand as well defining the current state of knowledge, links with specific scientific disciplines, and followed by positing possible research gaps. Footnote 7

The paper is structured as follows: the second section presents the research methodology and the third one the bibliometric analysis covering analysis using the Google Trends tool. The fourth is concentrated on a thematic analysis of the reference repository (indicated in the “ Bibliometric Analysis ” section). The conclusion with the description of a scope for future research is located in the last section.

The Term ‘Legal Technology’

When starting to analyse this topic, it is worth starting by explaining the origins of the term ‘legal technology’, which in the USA has been used since around 2010 and which derives from a combination of the terms ‘legal service’ and ‘technology’ (Hartung et al., 2017 ). Footnote 8 The term was originally used by the start-up community with a strong interest in the newly emerging field of IT services. Searching for earlier mentions of this related topic in the literature, one can find publications referring to lawyer support systems including expert systems dating back as far as the 1960s (Maiellaro, 1970 ). For the purpose of this article, this concept is understood as IT tools, including both hardware and software, used in law.

On the basis of the completed literature review, in accordance with the methodological guidelines of conducting an integrative literature review, I have analysed the concept and its definition (Torraco, 2005 ; Burke & Hutchins, 2007 ; Shuck, 2011 ). An in-depth analysis of the definitions used within the repository of texts confirmed the lack of a homogenous definition of the concept of legal tech, which corresponds to the nature of the IT services sector studied, which does not require the introduction of normative definitions, characterised by an evolutionary nature, variable scope, and the need for constant adaptation to the needs of the market, mainly the addressees of its services — the lawyers. Footnote 9

In the surveyed repository, I found no definition of legal technology as such. Few authors indicated the author’s explanation of the subjective understanding of the concept, which was done, for example, by T. Kerikmäe, T. Hoffmann, and A. Chochia in the article ‘Legal technology for law firms: Determining roadmaps for innovation’ indicating that ‘Legal technology, or Legal Tech, in this context represents a broad range of solutions that affect both lawyers and clients on various levels’ (Kerikmäe et al., 2018 ). However, these are not attempts to introduce a systematic definition of the concept or to collate the terminology used so far in the literature on the topic. In the compilation of texts, however, I have encountered numerous references directly to the notion, which occurred in different contexts. On the basis of the gathered knowledge, I can state that whilst the authors do not use a definition of the concept, they all use it when referring to any IT solutions applied in the field of law.

Not finding any attempts to define the notion of legal tech, I decided to introduce a division of the specificity of the texts included in the repository. Hence, I have singled out articles of the following nature Footnote 10 :

Case studies, offering in-depth descriptions of particular tools belonging to the field of legal tech (Giordano, 2004 ; Moxley, 2015 ; Gerami & Hawes, 2018 );

Technological, making clarifications in the area of applied technical solutions possible in specific tools or systems (Heintz, 2001 ; Hokkanen & Lauritsen, 2002 ; Ryan, 2017 ; Veatch, 2018 );

Overviews juxtaposing areas of technology application as translated, for example, into legal application practice (Oskamp & Lauritsen, 2002 ; Lettieri et al., 2018 ) or the historical context of the development of the legal tech field (Socha, 2017 );

Theoretical, analysing conceptual approaches to selected issues at the interface of technology and law (Leith, 2005 ; Ruhl & Katz, 2015 );

Opinion-forming, being expressions of a stance, the voice of authors regarding the further impact of legal tech on the legal service market (Marcus, 2008 ; Marin, 2011 ; Widrig & Tag, 2014 ; Dixon Jr,, 2015 ; Kerikmäe et al., 2018 ); and

Empirical, describing the course of the research carried out and its results (Lambert, 2008 ). Footnote 11

In conclusion, the notion of legal technology, which has no legal definition, is therefore essentially a doctrinal concept, variously understood by authors. For the most part, authors give a descriptive account of the concept or try to put it into a functional framework.

In addition to the search for a definition of the concept of legal tech, it is necessary to mention the process of digitalisation being the cause of the occurring changes on the legal service market, as well as the emergence and dynamic development of such sectors as legal tech (Oster, 2021 ). The process of digitalisation of law can be divided into three stages. The first was based on copying the content of the law into legal information systems, i.e. on their digitisation (Zeleznikow & Hunter, 1994 ). The second is based on the automation of decision-making processes, i.e. the creation of more or less sophisticated expert systems, using, amongst other things, inference mechanisms (Kerikmäe & Särav, 2017 ). The third consists in linking legal rules or contract content to programming codes, i.e. legal engineering (Goldenfein & Leiter, 2018 ).

The digitalisation of services triggers a kind of legal-technological interdependence, as shown by the development of artificial intelligence, the current manifestation of which is the work on the creation of a European framework for functioning in this field published by the European Parliament on 20 October 2020 entitled ‘Framework of ethical aspects of artificial intelligence, robotics, and related technologies’. Footnote 12 The new algorithms being developed will have to comply with the rules and legal order of the European Union, and the guardian of this change is legislation.

Materials and Methods

To capture the current state of scientific achievements on the subject the method of systematic literature review (SLR) has been used, allowing for a thorough understanding of the notion examined, assessment of the advancement of the research carried out to date, identifying research gaps, and thereby examining the quantitative and qualitative nature of available academic publications (“ Bibliometric Analysis Focused on the Year Publication ” section) (Gimenez & Tachizawa, 2012 ). “ Bibliometric Analysis Focused on the Selection of the Journal, Research Questions, and Keywords ” section, in turn, makes accessory use of the analytical tool Google Trends to show tendencies linked to the results found at earlier stages.

‘SLRs in management are used to provide transparency, clarity, accessibility, and impartial inclusive coverage on a particular area (Thome et al., 2016 )’ (Michie & Williams, 2003 ). As a comprehensive method, it is objective and replicable. The systematic literature review performed involved three stages: (1) creation of a literature database, (2) selection of the works included, and (3) analysis (Levy & Ellis, 2006 ). The first phase included search criteria identification, specification of inclusion criteria restricting works sequentially included in the set as well as their re-verification, and search for sources in three scientific databases: ProQuest, Ebsco, and JSTOR (Lu et al., 2018 ).

As any literature examination needs to meet the requirement of rigorous methodological research procedure, the approach taken was based on reviewing exclusively renowned electronic scientific databases making it possible to access sources from across the globe (Wilding et al., 2012 ). The systematic literature review within scientific databases helped examine the real state of knowledge without assessing accessory sources and avoiding the criticism of a fragmentary approach (Schmid & Kotulla, 2011 ). In my review approach, I decided to concentrate only on academic literature, what was a part of a strategy to capture contextual information (Adams et al., 2017 ). Footnote 13

The research activity started with defining criteria of automated search for works in the said databases, setting the key term as legal technology, a scientific and industry (business) notion of the subject under examination. Aware, however, that the term is often abbreviated to ‘legal tech’, I decided to extend my search to be certain that the analysis of sources was comprehensive (Lodhi, 2016 ). Footnote 14 Importantly, the review procedure confirmed that either of the verbal categories generated different results; hence, the assumption made was justified methodologically.

Then research moved on to the phase of isolation of the inclusion criteria for the publications featuring in the databases, which allowed for assessment of their utility (Booth et al., 2012 ). The search was limited to publications: (1) strictly concerning the sector examined, thus entering the terms in inverted commas (as legal technology and legal tech) to ensure a precise selection of appropriate texts; (2) in English, the universal language of science; (3) available as full text ; and (4) peer-reviewed (Schutte & Steyn, 2015 ). Given the research questions posed, I did not introduce time restrictions, which let me examine the period and edition frequency.

Additionally, in order to fully examine the existing state of the knowledge on the subject, I decided not to narrow the publications down to those with the phrases examined only in the title or abstract. That approach facilitated a realistic assessment of the number of publications about the sector studied here without running the risk of overlooking valuable sources. The results of the first stage of the systematisation involved selecting works fit for inclusion thus allowing for eliminating double sources, those of accessory importance and in a non-English version.

“ Thematic Analysis of the Reference Repository ” section employs the method of thematic analysis, allowing for proving a correlation of the subject discussed here with the field of legal and management sciences. For a more extensive analysis of the reference repository (described in the “ Bibliometric Analysis ” section) and in order to discover a conceptual map, it was used a quantitative analysis method in the form of thematic analysis. Its key assumption is based on: ‘(…) identifying and describing both implicit and explicit ideas within the data that is themes’ (Guest et al., 2011 ), which makes it: ‘(…) a flexible and useful research tool, which can potentially provide a rich and detailed, yet complex account of data’ (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ).

These research methods have helped find answers to the following research questions (Parris & Peachey, 2013 ):

Does the topic of legal technology (legal tech) has a homogeneous or interdisciplinary character?

Are articles about legal technology (legal tech) published in scientific periodicals?

Over what period of time can scientific publications on legal technology (legal tech) be found?

What key research areas is the topic of legal technology (legal tech) linked to?

Is the matter of legal technology (legal tech) enjoying a growing or decreasing interest online?

Is there a geographical segmentation in terms of the popularity of legal technology (legal tech) online?

Bibliometric Analysis

Following the research path presented above and the first stage, as just discussed, a database of literature was created including 577 items. The second stage involved a selection of the included works, with 507 publications eliminated. That move involved ones that were duplicates, with no thematic link, non-English (in Russian or Portuguese) or referring to the subject examined only marginally (e.g. covering domestic violence) (Valverde, 2004 ). The correctness was verified by means of abstract review, thus keeping key sources directly related to the topic of legal technology (legal tech). Ultimately, the reference repository featured 70 records (see Table 1 ). Footnote 15

The results of the systematic literature review for legal technology and legal tech were solely based on an analysis limited to selected three databases of scientific sources (ProQuest, Ebsco, and JSTOR), to provide certainty in terms of the mode of their publication, review procedure, and methodological rigor (Conn et al., 2003 ). Disregarding ‘grey literature’ included in the Google Scholar database helped arrive at the reference repository composition reflecting the current state of the global body of research (Hempel et al., 2016 ). Still, in order to showcase the potential of the subject, I decided to add the last column to Table 1 with a quantitative list of publications available in the Google Scholar database narrowed down to selected inclusion criteria available there, hence the possibility to enter the terms in inverted commas, with at least one of the words and found anywhere in the article (Adams et al., 2017 ). The process generated 9530 records. Google Scholar, which includes scientific industry and popular science publications, constitutes (potentially) one of the richest records within the subject in question (Mahood et al., 2014 ). One can then assume that the topic is of major interest to publishers also outside of the scientific community. Still, this information is only supplementary and shows a research interest in the subject, without including Google Scholar records in the final reference repository.

Bibliometric Analysis Focused on the Year Publication

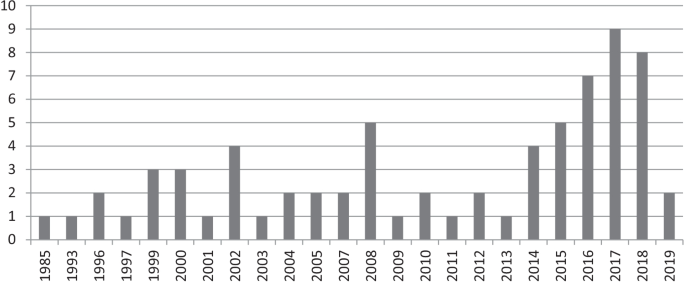

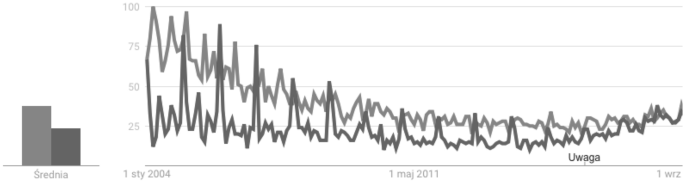

The systematic review of the literature concerning the subject within three scientific databases resulted in 70 scientific articles published in 1985–2019 (see Table 1 ) (Brereton et al., 2007 ). Consequently, the following stage of my research was an analysis of the number of publications in individual years, thus examining the trend related to scientists’ interest in the subject (see Chart 1 ).

The subject of ‘legal technology’ or ‘legal tech’ in academic publications. Source: Author’s own elaboration

As seen in the bar chart, the subject in question has been discussed in academic literature since the 1980s, starting from 1985. The mean value suggests a growing number of publications as well as an increasing interest shown by scientists in the topic. At the same time, it is worth noting that in the period from 1985 to 2019, the Google Scholar database includes 8110 records and 759 in 2019 alone. Footnote 16 Consequently, I believe that the subject is not new, because its beginnings date back to the 1980s, but only now the level of interest in it is visible, with a growing tendency.

Bibliometric Analysis Focused on the Selection of the Journal, Research Questions, and Keywords

Continuing the study of the obtained repository of 70 texts, I decided to analyse the collection in depth in terms of (1) the place of publication, i.e. the journals in which the authors published their texts; (2) the research questions and/or issues constituting the thematic core of the text; and (3) the selection of keywords assigned to each text.

Of the 70 sources selected, four were published in the American Bar Association’s journal The Judges’ Journal ([12], [13], [17], [25]). Three appeared in the journal Judicature published by the Bolch Judicial Institute Duke Law School ([01], [06], [08]) and in The Florida Bar Journal [50], [52], [53]). Two each were published in Family Law Quarterly ([09], [10]), Legal Information Management ([02], [21]), Artificial Intelligence and Law ([30], [31]), American Journal of Trial Advocacy ([44], [46]), In ternational Review of Law, Computers & Technology [35], [58]), University of Ottawa Press ([60], [61]), and Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies ([15], [63]). The remaining journals included one text each on a given topic: Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics [03], The Journal of Equipment Lease Financing [04], Future Internet [05], Technology Innovation Management Review [07], Iowa Law Review [11], International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care [14], Union of Jurists of Romanis Law Review [16], Systemic Practice and Action Research [18], Revista Direito GV [20], Northwestern University Law Review [22], Journal of Nursing Law [23], The Entrepreneurial Executive [24], Texas Law Review [26], Journal of Digital Asset Management [27], Information Systems Frontiers [28], Journal of Financial Service Professionals [29], Federal Communications Law Journal [33], International review of Law, Computers & Technology [35], IT Professional [36], International Financial Law Review [37], Daedalus [38], IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering [39], Journal of East Asia and International Law [40], Croatian International Relations Review [41], International Tax Review [42], University of Toronto Law Journal [43], American Journal of Trial Advocacy [44], Family Law Archive [45], Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law [47], University of Toledo Law Review [48], Circuits [51], Harvard Law & Policy Review [54], Touro Law Review [55], American Bar Association [56], Oxford Journal of Legal Studies [57], The Futurist [59], Columbia Law Review [62], Rand [64], The Supreme Court Review [65], Journal of Law and Society [66], Public Choice [67], Duke Law Journal [68], Yale Law & Policy Review [69], and Law & Social Inquiry [70].

Analysis of the repository in terms of the location of texts in journals revealed a relatively high level of fragmentation, yet legal technology topics are overwhelmingly within the scope of strictly legal publications (such as The Columbia Law Review ). There are also journals dealing with economics ( Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics ), management (e.g. Journal of Digital Asset Management ), innovation (e.g. Technology Innovation Management Review ), and IT (e.g. IT Professional ).

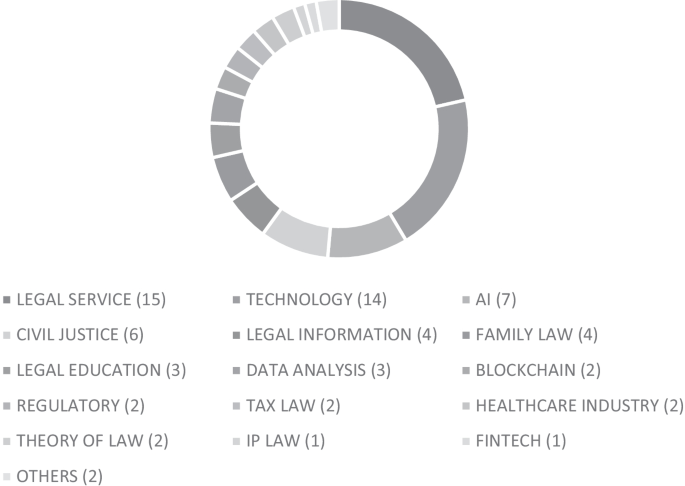

By examining the repository in terms of the research questions and keywords posed by the publications, it was possible to draw interesting conclusions about the main fields of interest of the researchers, as well as related topics. All 70 texts were grouped into 15 categories, according to the areas in which the authors posed their research questions and keywords. Thus, there is a predominance of issues covering the topic of legal service understood as changes occurring on the legal service market and within the profession (15 texts). In second place is the ‘technology’ category (14 texts), covering both IT topics and strictly technical aspects concerning the legal technology sector. Third place was taken by the ‘AI’ category (seven publications), which includes texts describing the impact of artificial intelligence on the legal services sector, both from a public and a private perspective. This was followed by the ‘civil justice’ category strictly covering aspects of the impact of legal technology and technology per se affecting the administration of justice.

Other categories included ‘legal information’ (four texts) dedicated to sources on legal information, ‘family law’ (four publications) dedicated to the specific field of family law, ‘legal education’ (three texts) including sources on the impact of the industry development on the education system and the need for its reform, ‘data analysis’ (three texts) covering the subject of data analysis which can be used in the field of legal technology, ‘blockchain’ (two texts) — dedicated to the implementation of this technique in the field of law, ‘regulators’ (two texts) — concerning the postulation of law regulation in selected areas, ‘tax law’ (two texts) — dealing strictly with the tax field, ‘healthcare industry’ (two sources) — the subject of the healthcare system, and ‘theory of law’ (two publications) — theoretical considerations in the light of the growing importance of the legal tech industry. The last two items — ‘IP law’ and ‘fintech’ — are examples of very specialised texts covering narrow fields; hence, their number is insignificant (Chart 2 ).

Key research areas and keywords related to ‘legal technology’ in academic publications. Source: Author’s own elaboration

To conclude this part of the research, legal technology is of interest mainly to lawyers and the legal services industry, as reflected in the vast majority of the repository texts published in legal journals. This sector clearly recognises the imminent (ongoing?) change that the implementation of technology is bringing in it. However, it can also be seen that technology, IT services, artificial intelligence, or data analysis, which were originally fields distant from legal sciences, are now becoming part of them. The future of the legal services sector is an interdisciplinary juxtaposition of classic legal sciences with entirely new areas. It is not only changing the existing legal service market, but also creating new IT services sectors, which makes this subject even more exciting and growing in topicality.

Thematic Analysis of the Reference Repository

As an auxiliary to content analysis, bibliometric studies allow for assessing individual features of a set. Their results show new knowledge that determines further directions of research as well as the need to use new research methods to analyse the available data more thoroughly (Nowell et al., 2017 ). Data analysis leading towards finding patterns (themes) helps acquire new information, and so perceive a new context of content acquired earlier as part of research questions posed at the preliminary stage (Braun & Clarke, 2012 ).

Themes can be interpreted using an inductive or deductive approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ). In my analysis, I used the former, based on examination of an entire data set (reference repository), to then look for thematic similarities between individual extracted codes, without assuming any preliminary theories (Clarke & Braun, 2013 ).

As the thematic analysis method is also subject to the rigor of a methodical research procedure, the further steps were strictly based on the recommendations by Virginia Braun and Victora Clarke (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ). Following the structure posited by the authors, they covered six stages (Table 2 ). Footnote 17

In phase one (Getting familiar with the data), I examined in detail the data selected at an earlier stage in the process of setting a reference repository. The process of repeated reading of all 70 articles aimed at actively looking for patterns and starting to develop guidelines as regards further content-coding (King, 2004 ; Nowell et al., 2017 ).

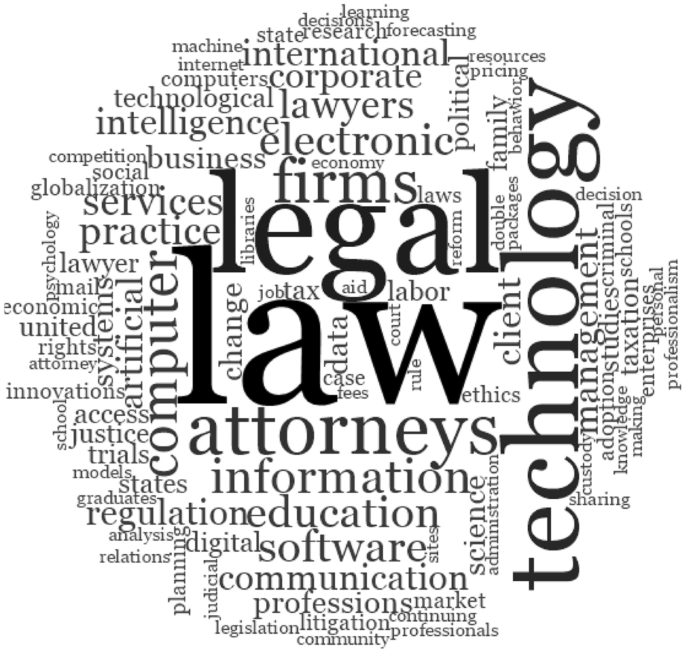

Verification of the frequency of appearance of keywords or derivative terms within a given thematic scope brings to life the existing links to other scientific disciplines (Huutoniemi et al., 2010 ). Because of the interdisciplinarity of the sector examined here, it is vital to understand its location on the map of scientific domains and correlation with individual ones. My analysis of data in their entirety let me conclude that only few publications featured the keyword category completed by the authors (Hjørland, 2001 ). Consequently, I decided to analyse the thematic categories to which a given publisher assigned each of the publications.

In phase two (Generating initial codes), I extracted from the ProQuest base data assigned to the category SUBJECT (39 records were analysed). Footnote 18 They included 194 terms (subjects). In the Ebsco base, where I analysed 20 texts, I took into account the category SUBJECT TERM, allowing me to select 106 items. Footnote 19 In the last database analysed, JSTOR, I took into consideration the TOPIC items (as no author assigned keywords to their publication), which resulted in 97 items. Footnote 20 The semantic extraction of terms suggesting the classification of a given article as falling within the topic examined (with all the texts in the reference repository) generated a list of 397 initial codes (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2011 ).

Further, in next phase (Searching for themes), I focused on my search for themes, i.e. sorting out the 397 codes, remembering that “(…) you can code individual extracts of data in as many different ‘themes’ as they fit into — so an extract may be uncoded, coded once, or coded many times, as relevant” (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ) (Chart 3 ).

Word frequency query results (based on a list of 397 codes). Source: Author’s own elaboration

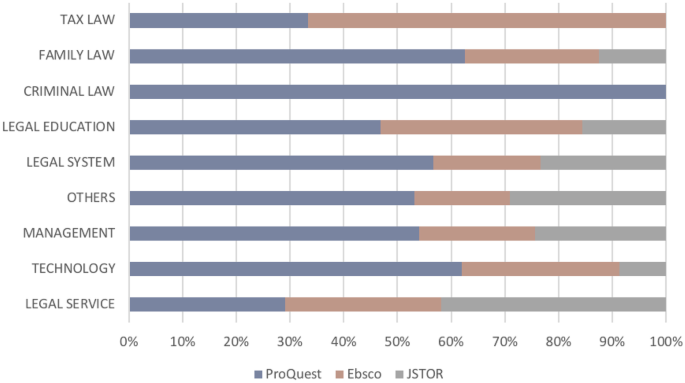

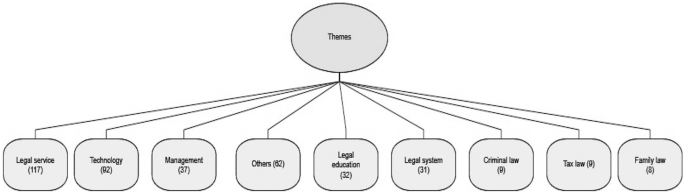

Ones from ProQuest let me find nine themes: (1) Technology (57 codes), (2) Legal service (34 codes), (3) Others (33 codes), (4) Management (20 codes), (5) Legal system (17 codes), (6) Legal education (15 codes), (7) Criminal law (9 codes), (8) Family law (5 codes), and (9) Tax law (3 codes). I divided the codes of the articles found in the Ebsco database into eight themes: (1) Legal service (34 codes), (2) Technology (27 codes), (3) Legal education (12 codes), (4) Others (11 codes), (5) Management (8 codes), (6) Tax law (6 codes), (7) Legal system (6 codes), and (8) Family law (2 codes). Last but not least, I sorted the JSTOR data into seven themes: (1) Legal service (49 codes), (2) Others (18 codes), (3) Management (9 codes), (4) Technology (8 codes), (5) Legal system (7 codes), (6) Legal education (5 codes), and (7) Family law (1 code). The Other theme is a set: “(…) miscellaneous to house codes — possibly temporarily — that do not seem to fit into your main themes” (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ) (Chart 4 ).

Existence of codes within the 3 scientific databases. Source: Author’s own elaboration

The activities performed resulted in 397 codes. I divided that set into nine themes: (1) Legal service (117 codes), (2) Technology (92 codes), (3) Management (37 codes), (4) Others (62 codes), (5) Legal education (32 codes), (6) Legal system (31 codes), (7) Criminal law (9 codes), (8) Tax law (9 codes), and (9) Family law (8 codes) (Chart 5 ). Footnote 21

Initial thematic map showing 9 themes (with the number of assigned codes). Source: Author’s own elaboration

The ‘Reviewing themes’ stage included the reviewing and refining of the selected themes. Finding thematic links, or absence thereof, helped me draft the ultimate thematic map, featuring the following categories. Then, in the ‘Defining and naming themes’ phase, I renamed and redefined the ultimate 4 themes: (1) Legal service (206 codes), (2) Technology (92 codes), (3) Management (37 codes), and (4) Others (62 codes). In the theme ‘Legal service’, I located sub-categories: Legal system, Legal education, Criminal law, Family law, and Tax law.

The stages described above let me move swiftly to the final phase of ‘Producing the report’ (Cassell & Symon, 2004 ).

The most essential information stemming from the study performed helped me show correlations with the terminology of the discipline of management sciences as one of four key themes as well as confirm the interdisciplinary nature of the topic discussed. Confirmation of the interdisciplinary nature of the legal tech sector enables precise indication of the fields of science to which researchers dealing with a given topic should refer. Subsequent studies of a given industry should not ignore the state of knowledge of legal and management sciences as well as technological solutions.

Analysis of the Popularity of the Terms ‘Legal Technology’ or ‘Legal Tech’ (Google Trends)

The systematic literature review was supplemented by an analysis of the popularity of the terms examined using a commonly accessible analytical tool, Google Trends (Jun et al., 2018 ). It allows for monitoring popularity levels of terms of interest available online in the world’s most popular search engine, Google. Footnote 22 The data below obtained by means of Google Trends helped me specify the level of interest in individual concepts in the Google search process as well as their regionalisation (Ouellette, 2014 ). That information supplements the knowledge about the existence of trends related to the matter at hand (Heyman, 2015 ). Footnote 23

Using the Google Trends tool, I showed the following parameters: the entire world and the period from 1 January 2004 to 12 November 2019. Additionally, I decided not to make the categories more precise, this avoiding a thematic narrowing-down, of particular importance given the interdisciplinary nature of the subject scope between IT, business, law and, as mentioned before, legal service, technology, and management (López-Cózar et al., 2018 ). The Google Trends tool confirmed the dominant frequency of queries for the term legal technology (38/100 on average) over its abbreviated version legal tech (24/100 on average). Also, a growing trend was found for the popularity of legal tech starting from December 2015 (see Chart 6 ).

Summary of popularity of the terms ‘legal technology’ (light grey) and ‘legal tech’ (dark grey) found by Google Trends. Source: Google Trends: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=legal%20technology,legal%20tech

Based on the percentage values calculated for searches of the two terms in question across the world, an interesting regularity was observed. Footnote 24 Namely, in the countries of the common law system as well as ones whose legal systems feature some of its aspects, the search for legal technology is dominant (USA — 52%, Canada — 62%, Australia — 78%, UK — 72%, India — 75%, or South Africa — 81%). At the same time, in the countries of the continental legal system legal tech is considerably more frequently searched in Google (Germany — 87%, France — 79%, Poland — 100%, or Russia — 100%). Footnote 25 A higher level of use of the term legal tech in the countries of the common law system (and the term legal technology in the countries of the civil law system) provides relevant information necessary for further research on the subject.

The Google Trends tool also allowed for defining the highest levels of popularity attached to the terms legal technology and legal tech within the timeframe in question, i.e. from 1 January 2004 to 12 November 2019 divided per country. The values are presented in the table below on a 0 to 100 scale, where the maximum number stands for the location where the term was searched for most frequently out of all searches (within a given location) and 50 stands for the location with the term’s popularity twice lower. Footnote 26 To illustrate the geographical distribution, I opted for showing only the first five of the countries interested (in both terms examined) (Table 3 ).

The results suggest that Singapore is a country where the popularity level of the topic discussed here is considerable, as it ranks high second, for both forms of the term. Further, the emerging market of African countries seems to express an interest, too, as evidenced by the presence of as many as three states from Africa on the legal technology list. A wide range of countries in both columns suggests the need to use appropriate terminology when researching the field of our interest here.

Conclusions

The paper analyses the current state of research concerning the matter of legal technology. The work is conducted through a systematic literature review, bibliometric, and thematic analysis.

The bibliometric analysis may be auxiliary as real research work on issues should not be limited to just numbers and ought to evaluate content. However, presenting a current list of literature on a given subject and offering an assessment of selected features of that set in a single place allowed me for using correct terminology, defining directions for further research efforts, and finding research gaps. The systematic literature review has helped capture in a single place the actual state of academic publications on legal technology, identify the legal tech industry’s potential, and take note of the growing interest in the subject matter (Ratinho et al., 2020 ). The superimposition of two images: one showing the number of academic publications in the period 1985–2019 (Chart 1 ) and the other the interest in the terms examined here in the Google search engine (Chart 6 ), clearly shows that starting from 2014 the interest in legal technology is constantly growing, both in science and elsewhere.

At the same time, the process of reference repository building proved that searches for legal technology or legal tech (within scientific databases) could render misleadingly high results for the number of publications. After their qualitative verification, it turned out that the set included many publications not content-linked with the sector in question, which shows a broad context of using terms in many scientific domains, such as research on domestic violence, culture, or the history of feminist movements (Padoongpatt, 2015 ; Sreenivas, 2015 ; Valverde, 2004 ).

The thematic analysis method has confirmed the interdisciplinary context of the sector examined, finding patterns (themes) within thematic terms present for each of the analysed publications from the reference repository. Consequently, the conclusion is that the legal technology industry can be an object of research in terms of technological solutions, the legal service sector, and management systems.

The paper’s originality involves identifying (1) the current state of academic literature on legal technology, (2) a different approach to the use of a term legal tech and legal technology in the countries of the common law and continental law systems, (3) rising level of popularity of terms legal tech and legal technology online, (4) an interdisciplinary context of a matter of legal technology, and (5) implications whether legal technology should be analysed from the perspective of its influence on the whole legal sector.

The qualitative analysis of the content of the set examined exposed numerous research gaps that can be helpful for future research directions. The key ones being (1) the absence of a systematic literature review for the terms legal technology and legal tech in ‘grey literature’, (2) the absence of research concerning the economic and social impact of legal technology on the legal service market, and (3) the absence of studies examining the legal service market transformation process evident in the form of the commonly observed phenomena of service commodification or servitisation (Bhimani et al., 2019 ).

The conducted research was limited only to the examination of the potential of interest in the given topic within the indicated time period, mainly within scientific literature, which is its limitation. Another extremely interesting source important source for the development of science is sources of grey literature, which, especially in the context of the subject under study, are gaining much importance. Numerous publications, industry reports, or surveys of private institutions provide a wealth of relevant data on the researched legal tech market and do not fall within the scope of scientific literature. Therefore, for future development, in the next stages of the research it is worthwhile looking strictly at industry reports allowing analysis of the legal tech sector in individual countries, examining their specific features and important differences.

Importantly for the continuation of research in the area indicated, it is worth looking into the examination of the process of digitalisation of legal services. It is possible to carry out a systematic literature review of this concept, which would allow for answering the same research questions, yet in a new context, i.e. the timeline of occurrence of scientific articles on a given topic, key areas in relation to a given topic, growing or declining interest in it, or geographical segmentation. Overlaying the information obtained would facilitate the formulation of assumptions in terms of further directions of change, new areas of interest, and finding key areas related to both the topics of digitisation of legal services and legal tech.

Report World Bank. The Changing Nature of Work, World Bank 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/816281518818814423/2019-WDR-Report.pdf . (9 November 2019, date last accessed).

In this article, the terms ‘legal technology’ and ‘legal tech’ are used as synonyms. In their scope, they cover IT solutions dedicated for the legal services sector. A separate thematic category is ‘law tech’ which refers to IT tools designed solely for consumers.

Report Litify, ‘Law 2.0 The Disruptors, Innovators, and the Laggards Who May Be Left Behind’, Litify 2019. https://www.litify.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Law2.0-Litify.pdf (9 November 2019, date last accessed).

Legal Services Market by Types (B2B Legal Services, B2C Legal Services, Criminal Law Practices and Hybrid Commercial Legal Services), By Size, By Practice, By Key Players And By End Users—Global Forecast To 2023 (12 February 2020, date last accessed). Deloitte report ‘Developing Legal Talent. Stepping into the Future Law Firm’, Deloitte 2016. https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/audit/articles/developing-legal-talent.html (9 November 2019, date last accessed).

The website of the research project Stanford Law School’s LegalTech : https://techindex.law.stanford.edu . When the project was launched in November 2017, the list of global legal tech firms included 750 entities. In October 2021, there are 1816 of them.

The increasing number of publications is described in Part 3.

In my future research work, I intend to analyse industry (business) reports (on legal technology) that are sources of ‘grey literature’, thus enabling a comparison with the results published in this article.

In source literature, the terms legal tech , legal technology , law tech , legal IT , or legal informatics are used interchangeably, as confirmed by a review of all the sources included in the repository.

The following part of the article includes a detailed explanation of the systematic literature review process which allowed for the creation of the said text repository.

At the end of each of the isolated categories, I indicate examples of texts from the repository which fit in with its specific aspects.

In the entire repository, merely a single text based on empirical studies was identified and acknowledged in a relevant footnote.

European Parliament resolution of 20 October 2020 with recommendations to the Commission on a framework of ethical aspects of artificial intelligence, robotics and related technologies, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0275_EN.html .

I have ultimately decided to choose three acknowledged (electronic) scientific databases (ProQuest, Ebsco, JSTOR) as selective literature reviews including selected journals or thematic categories could fail to offer a complete picture of the current state of academic publications, increasing often of an interdisciplinary nature. I was able to access those databases thanks to a license agreement of my University between 2 and 26 November 2019.

The said approach to search criteria identification complies with the principles of investigation triangulation, allowing for a higher level of reliability and transparency of the entire research process. The entered formula is the following: ProQuest and Ebsco—(‘legal technology’) OR (‘legal tech’), and JSTOR—(‘legal technology’) OR (‘legal tech’)).

See Appendix Reference repository.

Until 21 November 2019, Google Scholar offers 21 publications of 2019 with the term ‘legal technology’ in the title and 35 ones with ‘legal tech’.

The stage of coding has been performed using Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) – NVIVO.

‘Subject’ definition used in ProQuest database: “The ProQuest Thesaurus is used to index the ProQuest Central subject field. A thesaurus is an alphabetical listing of all the subject terms in a single database, used to classify and organize information for that database”. https://proquest.libguides.com/pqc/fields (02 December 2019, date last accessed). 39 records in ProQuest database were analysed as only authors of 11 articles indicated their keywords.

Subject term’ used in Ebsco database: “subject terms that are assigned to describe the content of an article”. https://connect.ebsco.com/s/article/Advanced-Searching-with-CINAHL-Subject-Headings?language=en_US (02 December 2019, date last accessed). “EBSCO maintains a Comprehensive Subject Index (CSI) of subject terms, which are applied to all articles indexed by EBSCO”. https://connect.ebsco.com/s/article/How-does-EBSCO-create-subject-headings-for-EBSCOhost-articles?language=en_US (02 December 2019, date last accessed). 20 records in Ebsco database were analyses as only authors of 4 articles indicated their keywords.

‘Topic’ used in JSTOR database: “topics are terms sourced from the JSTOR Thesaurus, a taxonomy built from 17 + controlled vocabularies that is integrated with the JSTOR platform”. https://about.jstor.org/platform-features/topics-on-jstor/ (02 December 2019, date last accessed). 11 records in JSTOR database were analysed while none of the authors indicated their keywords.

The bulky Other category includes such terms as: diabetic retinopathy, genomes, sequencing, genic resources, nurses, hospitals, political parties, and anthropology, which are not logically linked.

Worldwide desktop market share of leading search engines from January 2010 to July 2019: https://www.statista.com/statistics/216573/worldwide-market-share-of-search-engines/ (12 November 2019, date last accessed).

The compilation could be usefully complemented with information on the presence of specific words over the set period in the collection of books from Google Books, featuring more than 25 million items, as enabled by the Google Ngram tool. Its important methodological limitation is the temporal narrowing down of its results to only 1800–2008 (book publication date), which in the case of the subject at hand considerably narrows down the research field, although it does show the existing trends. Googl Ngram has several limitations that influence the reliability of the results. The Google Books catalogue includes considerably many academic sources, which partly distorts the results, yet is an interesting complementary source of knowledge at the level of preliminary source review. Source Google Ngram: https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=legal+technology&case_insensitive=on&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=50&share=&direct_url=t4%3B%2Clegal%20technology%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Blegal%20technology%3B%2Cc0%3B%3BLegal%20Technology%3B%2Cc0#t4%3B%2Clegal%20technology%3B%2Cc0%3B%2Cs0%3B%3Blegal%20technology%3B%2Cc0%3B%3BLegal%20Technology%3B%2Cc0 . (12 November 2019, date last accessed).

As regards the Google Trends tool, the popularity of the term searched is proportional to the overall number of Google searches made over a given time in a given location.

Source – Google Trends: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=legal%20technology,legal%20tech .

Information on the data collection system in Google Trends: https://support.google.com/trends/?hl=en#topic=6248052 .

Abramovsky, L., & Griffith, R. (2006). Outsourcing and offshoring of business services: How important is ICT? Journal of the European Economic Association, 4 (2–3), 594–601.

Article Google Scholar

Adams, R. J., Smart, P., & Huff, A. S. (2017). Shades of grey: Guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19 (4), 432–454.

Bhimani, H., Mention, A. L., & Barlatier, P. J. (2019). Social media and innovation: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144 , 251–269.

Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review . SAGE Publications.

Google Scholar

Bourke, J., Roper, S., & Love, J. H. (2020). Innovation in legal services: The practices that influence ideation and codification activities. Journal of Business Research, 109 , 132–147.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2 Research Designs . Washington: American Psychological Association.

Brereton, P., Kitchenham, B. A., Budgen, D., Turner, M., & Khalil, M. (2007). Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. Journal of Systems and Software, 80 (4), 571–583.

Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2007). Training transfer: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 6 (3), 263–296.

Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2004). Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research . Sage Publications.

Book Google Scholar

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26 (2), 120–123.

Conn, V. S., Valentine, J. C., Cooper, H. M., & Rantz, M. J. (2003). Grey literature in meta-analyses. Nursing Research, 52 (4), 256–261.

Dixon, H. B., Jr. (2015). Technology and the future of legal services. The Judges’ Journal, 54 , 40.

Fenwick, M., Corrales, M., & Haapio, H. (2019). Legal tech smart contracts and blockchain . Springer.

Gerami, M., & Hawes, A. (2018). Justis: At the forefront of the evolution of legal technology in the UK. Legal Information Management, 18 (2), 86–92.

Gimenez, C., & Tachizawa, E. (2012). Extending sustainability to suppliers: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17 (5), 531–543.

Goldenfein, J., & Leiter, A. (2018). Legal engineering on the blockchain: ‘Smart contracts’ as legal conduct. Law and Critique, 29 (2), 141–149.

Giordano, S. M. (2004). Electronic evidence and the law. Information Systems Frontiers, 6 (2), 161–174.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2011). Applied Thematic Analysis . Sage Publications.

Hartung, M., Bues, M. M., & Halbleib, G. (2017). Legal tech . Munich: CH Beck.

Hartung, M., Bues, M. M., & Halbleib, G. (2018). Legal Tech: A Practitioner’s Guide . Munich: CH Beck.

Hempel, S., Xenakis, L., & Danz, M. (2016). Systematic review step 3: Conduct a literature search and screen for inclusion. In S. Hempel, L. Xenakis, & M. Danz (Eds.), Systematic Reviews for Occupational Safety and Health Questions: Resources for Evidence Synthesis (pp. 24–34). RAND Corporation.

Chapter Google Scholar

Heintz, M. E. (2001). The digital divide and courtroom technology: Can David keep up with Goliath. Federal Communications Law Journal, 54 , 567.

Heyman, S. (2015) Google books: A complex and controversial experiment . NYTimes.com. Accessed November 12, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/29/arts/international/google-books-a-complex-and-controversial-experiment.html

Hokkanen, J., & Lauritsen, M. (2002). Knowledge tools for legal knowledge tool makers. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 10 (4), 295–302.

Hjørland, B. (2001). Towards a theory of aboutness subject topicality theme domain field content... and relevance. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology , 52 (9), 774–778.

Huutoniemi, K., Klein, J. T., Bruun, H., & Hukkinen, J. (2010). Analysing interdisciplinarity: Typology and indicators. Research Policy, 39 (1), 79–88.

Jun, S. P., Yoo, H. S., & Choi, S. (2018). Ten years of research change using Google Trends: From the perspective of big data utilizations and applications. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 130 , 69–87.

Mahood, Q., Van Eerd, D., & Irvin, E. (2014). Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits. Research Synthesis Methods, 5 (3), 221–234.

Marcus, R. L. (2008). The impact of computers on the legal profession: Evolution or revolution. Northwestern University Law Review, 102 , 1827.

Katsh, M. E. (1996). Competing in cyberspace: The future of the legal profession. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 52 (2–3), 109–117.

Kerikmäe, T., Hoffmann, T., & Chochia, A. (2018). Legal technology for law firms: Determining roadmaps for innovation. Croatian International Relations Review, 24 (81), 91–112.

Kerikmäe, T., & Särav, S. (2017). Paradigms for automatization of logic and legal reasoning. Law and Logic: Contemporary Issues Duncker & Humblot, 205 , 222.

King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (p. 256). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Lambert, J. T. (2008). Attorneys and their use of technology. The Entrepreneurial Executive, 13 , 83.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2011). Beyond constant comparison qualitative data analysis: Using NVivo. School Psychology Quarterly, 26 (1), 70.

Leith, P. (2000). IT and law and law schools. International Review of Law Computers & Technology, 14 (2), 171–189.

Leith, P. (2005). Developing theory in legal technology. International Review of Law Computers & Technology, 19 (3), 231–233.

Levy, Y., & Ellis, T. J. (2006). A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in support of information systems research. Informing Science Journal, 9 , 181–212.

Lettieri, N., Altamura, A., Giugno, R., Guarino, A., Malandrino, D., Pulvirenti, A., & Zaccagnino, R. (2018). Ex machina: Analytical platforms law and the challenges of computational legal science. Future Internet, 10 (5), 37.

Lodhi, M. F. K. (2016). Quality issues in higher education: The role of methodological triangulation in enhancing the quality of a doctoral thesis. Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 4 (1), 62.

López-Cózar, E. D., Orduña-Malea, E., Martín-Martín, A., & Ayllón, J. M. (2018). Google Scholar: The ‘big data’ bibliographic tool . arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.06351

Lu, Y., Papagiannidis, S., & Alamanos, E. (2018). Internet of Things: A systematic review of the business literature from the user and organisational perspectives. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136 , 285–297.

Marin, D. (2011). General considerations regarding electronic monitoring services and programs. Union of Jurists of Romania Law Review , 1 (2).

Maiellaro, N. (1970). Using expert systems to check building applications. WIT Transactions on Information and Communication Technologies, 19 , 12.

Michie, S., & Williams, S. (2003). Reducing work related psychological ill health and sickness absence: A systematic literature review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60 (1), 3–9.

Moxley, L. (2015). Zooming past the monopoly: A consumer rights approach to reforming the lawyer’s monopoly and improving access to justice. Harvard Law & Policy Review, 9 , 553.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16 (1), 1609406917733847.

Oskamp, A., & Lauritsen, M. (2002). AI in law practice? So far, not much. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 10 (4), 227.

Oster, J. (2021). Code is code and law is law—The law of digitalization and the digitalization of law. International Journal of Law and Information Technology, 29 (2), 101–117.

Ouellette, L. L. (2014). The Google shortcut to trademark law. California Law Review, 102 , 351.

Padoongpatt, T. M. (2015). ‘A landmark for Sun Valley’: Wat Thai of Los Angeles and Thai American suburban culture in 1980s San Fernando Valley. Journal of American Ethnic History, 34 (2), 83–114.

Parris, D. L., & Peachey, J. W. (2013). A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 113 (3), 377–393.

Ratinho, T., Amezcua, A., Honig, B., & Zeng, Z. (2020). Supporting entrepreneurs: A systematic review of literature and an agenda for research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change , 154 , 119956.

Ryan, P. A. (2017). Smart contract relations in e-commerce: Legal implications of exchanges conducted on the blockchain. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7 (10), 10–17.

Ruhl, J. B., & Katz, D. M. (2015). Measuring monitoring and managing legal complexity. Iowa Law Review, 101 , 191.

Schmid, S., & Kotulla, T. (2011). 50 years of research on international standardization and adaptation — From a systematic literature analysis to a theoretical framework. International Business Review, 20 (5), 491–507.

Schutte, F., & Steyn, R. (2015). The scientific building blocks for business coaching: A literature review. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13 (1), 1–11.

Shuck, B. (2011). Integrative literature review: Four emerging perspectives of employee engagement: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 10 (3), 304–328.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104 , 333–339.

Socha, G. (2017). What will AI mean for you. Judicature, 101 , 6.

Sreenivas, M. (2015). Birth control in the shadow of empire: The trials of Annie Besant 1877–1878. Feminist Studies, 41 (3), 509–537.

Thomé, A. M. T., Scavarda, L. F., & Scavarda, A. J. (2016). Conducting systematic literature review in operations management. Production Planning & Control, 27 (5), 408–420.

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4 (3), 356–367.

Valverde, M. (2004). A postcolonial women’s law? Domestic violence and the Ontario liquor board’s ‘Indian list’ 1950–1990. Feminist Studies, 30 (3), 566–588.

Veatch, W. S. (2018). Using artificial intelligence technology to remain competitive in a Fintech environment. The Journal of Equipment Lease Financing (online), 36 (2), 1A-11A.

Wang, M. (2007). The impact of information technology development on the legal concept—A particular examination on the legal concept of ‘Signatures.’ International Journal of Law and Information Technology, 15 (3), 253–274.

Widrig, D., & Tag, B. (2014). HTA and its legal issues: A framework for identifying legal issues in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 30 (6), 587–594.

Wilding, R., Wagner, B., Colicchia, C., & Strozzi, F. (2012). Supply chain risk management: A new methodology for a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Management, 17 (4), 403–418.

Zeleznikow, J., & Hunter, D. (1994). Building Intelligent Legal Information Systems: Representation and Reasoning in law (No. 13) . Netherlands: Kluwer Law and Taxation Publishers.

Download references

Fund was provided by National Science Centre, Miniatura 2 (DEC-2018/02/X/HS4/03272/1).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Economics, Finance and Management, Faculty of Management and Social Communication, Jagiellonian University, Cracow, Poland

Karolina Mania

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Karolina Mania .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reference repository

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mania, K. Legal Technology: Assessment of the Legal Tech Industry’s Potential. J Knowl Econ 14 , 595–619 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-00924-z

Download citation

Received : 16 December 2020

Accepted : 13 January 2022

Published : 28 January 2022

Issue Date : June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-00924-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Legal technology

- Legal service

- Service management

- Legal management

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Evolving Impacts of Technology in the Legal System

- Share on Facebook

- Tweet this Story

- Share on Google+

While change can be hard in the legal industry, legal professionals now find themselves in a position to embrace newer, perhaps unfamiliar technologies to support a growing number of online court services.

In response to the world-wide COVID-19 pandemic, courts around the world have had to adapt to the challenges presented by this unprecedented situation, perhaps some better than others. While a critical transition from traditional court proceedings to an online mode has allowed justice to continue in many jurisdictions, courts and legal professionals are now tasked with the added responsibility of adopting new and somewhat unfamiliar technologies in the face of an ever-changing legal landscape.

Change can be hard. The justice system and its pre-pandemic resistance to technology are prime examples of a sector that is extremely careful to make hastily changes. However, law professionals and individuals needing legal services are looking to technology to help them safely resume work and secure legal support in the ongoing face of COVID-19. In an effort to explore how the pandemic has changed the courts perception and use of technology, as well as to address issues of access to the courts, ABC Legal Services held a webinar on the topic of legal technology and its growing impact on access to the legal system. The webinar was hosted by the company’s Training and Communication Specialist, Tomas Campomanes. The panelists included Radley Angelo, Head of Customer Success at ABC Legal, Brandon Fuller, Chief Technology Officer at ABC Legal and President of Docketly and me, Sascha Mehlhase, VP of Products at ABC Legal.

Radley Angelo kicked off our discussion providing an overview of natural language processing (NLP) and its role in the legal industry. In its simplest definition, NLP is a type of software that allows computers to read text or language quickly. NLP deployments in the document and text-heavy legal sector can help legal professionals quickly work through contracts or other legal documents. The technology provides valuable insight and analytics to the reader, including the ability to summarize common clauses and if they varied from standard phrases. Scalable deployments of NLP in the legal sector can predict many concepts, which can help improve efficiency in staff hours and paralegal time. The potential of NLP in the legal sector is just getting started. Radley finished the topic by stating it is exciting to see this is where the industry is trending with this technology as we more closely embrace insights and intelligence.

From there, Brandon Fuller went into discussion on the wide uses of machine learning (ML) technology inside artificial intelligence (AI). Brandon discussed how machine learning isn’t really about machines, but how humans can better do their jobs with the aid of machines. Brandon stated, “Basically you can have a human do it, a machine ‘watches’ and then the machine repeats the pattern and detects things at a larger scale by remembering what you did. If you aren’t quite sure what causes something, you can feed the machine a variety of data and it will find the correlations for you.”

The legal sector’s initial ML deployments were seen in the backend for invoice and billing. Now, legal professionals can leverage ML to help identify and analyze large volumes of data from the courts, and from there, dictate what tasks and workflows need to be moved through. With ML, a machine can perform tasks at record speed with exceptional efficiency, for example, law professionals can use ML for document review where the technology reviews a large file to find patterns, as well as varieties of service rates and service probabilities. Brandon advised with the additional use of ML technology, a large amount of employee work can be done digitally –making their jobs more efficient and effective, which directly impacts the customer’s experience by having a quick and positive interaction.