- The Big Debate: Should Human Cloning Be Legalised?

In 1997, Ian Wilmut and Keith Campbell of the Roslin Institute shocked the scientific community and the world when they announced the birth of a successfully cloned sheep named Dolly. After Dolly was born, the cloning of humans seemed , at least in principle, achievable. The possibility of cloning humans sparked heated debate across the world about the acceptability and necessity of such a procedure. Some felt that biotechnology had gone a step too far while others welcomed such a development. Since then, several other species including, goats, pigs, mules, cows, mice, and cats, have been successfully cloned. The possibility of human cloning engages not only religious, social, cultural, and moral challenges but also legal and ethical issues. The debate on human cloning also raises questions of human and fundamental rights, particularly liberty of procreation, freedom of thought and scientific inquiry, and right to health. There are currently several types of cloning carried out by scientists that include cellular cloning, embryo cloning, and molecular cloning. Embryo cloning is further divided into, nuclear transfer, blastocyst division or twinning, and blastomere separation. The cloning technique used to clone Dolly was a type of nuclear transfer.

Arguments In Favor Of Human Cloning

Help infertile couples.

Human cloning technology, once optimized, will have the ability to help infertile couples who cannot produce sperm or eggs to have children that are genetically related to them. A couple could potentially decide to have a clone of the man born through his female partner or a clone of the woman providing the genetic material. A human clone would, therefore, become a “ single parent-child .” Currently, treatment for infertility is not very successful. By some estimates, the success rates of infertility treatments, including IVF (in vitro fertilization) is less than 10%. The procedures are not only frustrating, but they are also expensive. In some instances, human cloning technology could be considered as the last best hope for having children for infertile couples.

Recreate A Lost Child Or Relative

The loss of a child is one of the worst tragedies that parents face. After such a painful ordeal, grief-stricken parents often wish they could have their perfect baby back. Human cloning technology could potentially allow parents to recreate a child or relative while seeking redress for their loss. Cells of a dying child could be taken and used later for cloning without consent from the parents. While the new child would not take away the memory, he/she would probably help take away some of the pain. The technology would allow parents to have a twin of their child, and like other twins, the new child would be a unique individual.

Exercise Procreative Liberty

The freedom to decide whether or not to have an offspring is an important concept of personal liberty. People have the right to utilize human cloning technology in the same way they have a right to other reproductive related procedures and technologies such as the Vitro fertilization or contraceptives. A parent’s right to bear a child through cloning should, therefore, be respected. When the technology is established and becomes no less safe than natural reproduction, then human cloning should be allowed as a reproductive right. Cloning would also allow members of the LGBT community to have children related to them. In a lesbian couple, one of them could be cloned and brought to term in either of the women. In a gay couple, one of the men could be cloned, but the couple would need to find a woman to donate an egg and a surrogate mother to bring the embryo to term.

Offspring Free Of Genetic Defects

Current knowledge of bioengineering coupled with human cloning technology could help many parents have offspring free of defective genetic material that could cause disorders and deadly diseases. In a case where both parents have recessive genes for the fatal disease, they could avoid more traditional methods that could result in a child with dominant genes, which would consequently lead to the disease. The parents could use human cloning technology to have a child without the disease since the genetic makeup of the child would be the same as that of a parent who was cloned.

Provide Medical Cures

Human cloning technology could help children born with incurable diseases that can only be treated through a transplant, where donors with an organ match are not found. Cloning technology would allow a child to be cloned under reproductive purpose, which would allow the resulting clone to donate an organ such as a kidney or bone marrow. In that case, the older child would be saved , and the younger clone child would also live since bone marrow regenerates, and humans can live with one kidney. The technology would allow a parent to save an existing life through a new life. Human cloning technology could also utilize the nuclear transplantation technique to produce human stem cells for therapeutic purposes. Stem cells from the umbilical cord could be cultured and allowed to develop into tissues such as bone marrow or a kidney when needed. Since the DNA of the new organ or bone marrow is matched to the patient, there would be a lower risk of organ rejection as a foreign matter by the patient’s body.

A Step Towards Immortality

Human clones are sometimes called “ later-born twin s” by those receptive to the idea of human cloning. The term is justified by the fact that the cloned being would have the same genetic material as the original and would be born after the person who is cloned. The process of human cloning can be considered as taking human DNA and reversing its age back to zero. Some scientists believe that the technology would allow them to understand how to reverse DNA to any desirable age. Such knowledge would be seen as a step closer to a fountain of youth. Some people believe that human cloning technology would allow people to have some kind of immortality because their DNA would live on after they die.

Arguments Against Human Cloning

Medical danger.

Based on information gained from previous cloning experiments, cloned mammals die younger and suffer prematurely from diseases such as arthritis. Cloned animals also have a higher risk of developing genetic defects and being born deformed or with a disease. Studies on cloned mice have shown that they die prematurely from damaged livers, tumors, and pneumonia. Since human cloning technology is not tested, scientists cannot rule out biological damage to the clone. The National Bioethics Advisory Commission report stated that it is morally unacceptable for anyone in the private or public sector, whether in a research or clinical setting, to attempt to create a child through somatic cell nuclear transfer cloning because it would pose unacceptable potential risks to the fetus or child. Human cloning technology would also put the mother at risk.

Dr. Leon Kass, chairman of the President’s Council of Bioethics, has warned that studies on animal cloning suggest late-term fetal losses or spontaneous abortions occur at a higher rate in cloned fetuses than in natural pregnancies. In humans, a late-term fetal loss could significantly increase maternal mortality and morbidity. Cloning could also pose psychological risks to the mother due to the late spontaneous abortions, the birth of a child with severe health problems, or the birth of a stillborn baby.

Disrespect For The Dignity Of The Cloned Person

One of the most satisfying and difficult things about being a human is developing a sense of self. It involves understanding our capabilities, strengths, needs, wants, and understanding how we fit into the community or the world. A crucial part of that process is learning from and then breaking away from parents and understanding how we are similar or different from our parents. Human cloning technology would potentially diminish the individuality or uniqueness of a cloned child. Even in instances where the child is cloned from someone other than their parents, it would not be very easy for them to develop a sense of self. It could also lead to the devaluation of clones when compared to a non-clone or original. Cloning would also infringe on the clone’s freedom, autonomy, and self-determination. Cloned children would be raised unavoidably in the shadow of the person they were cloned from.

Co-modification Of Cloned Children

Human cloning technology would, in return for compensation, provide offspring with specific genetic makeup. Cloning a child would also require some patented reproductive procedure and technology that could be sold. Consequently, human cloning technology would lead society to view children and people as objects that can be designed and manufactured with specific characteristics. Buyers would theoretically want to pay top dollar for a cloned embryo of a Nobel Prize winner, celebrity, or any other prominent figure in society.

Societal Dangers

Some experts have argued that societal hazards may be the least appreciated in discussions on human cloning technology. Such technology could, for example, lead to new and more effective forms of eugenics . In countries run by dictators, governments could engage in mass cloning of people who are “deemed” of proper genetic makeup. In democracies, human cloning technology could lead to free-market eugenics that could have a significant societal impact when coupled with bioengineering techniques. People could theoretically bioengineer their clones to have certain traits. When done on a mass scale, it would lead to a kind of a master race based on fashion.

International Stand On Human Cloning

In March 2005, the United Nations General assembly approved a non-binding Declaration that called on UN member states to ban all forms of human cloning as incompatible with the protection of human life and human dignity. The Declaration concluded efforts that had begun in 2001 with a proposal from Germany and France for a convention against the reproductive cloning of humans. The US and 83 other nations supported a ban on all human cloning technology for reproductive and therapeutic or experimental purposes. The other 34 nations, including the UK, Japan, and China, voted against the ban. While 37 countries abstained from the vote, and 36 countries were absent.

More in Society

The Most Isolated Tribe on Earth

Countries Who Have Never Won A Summer Olympic Medal

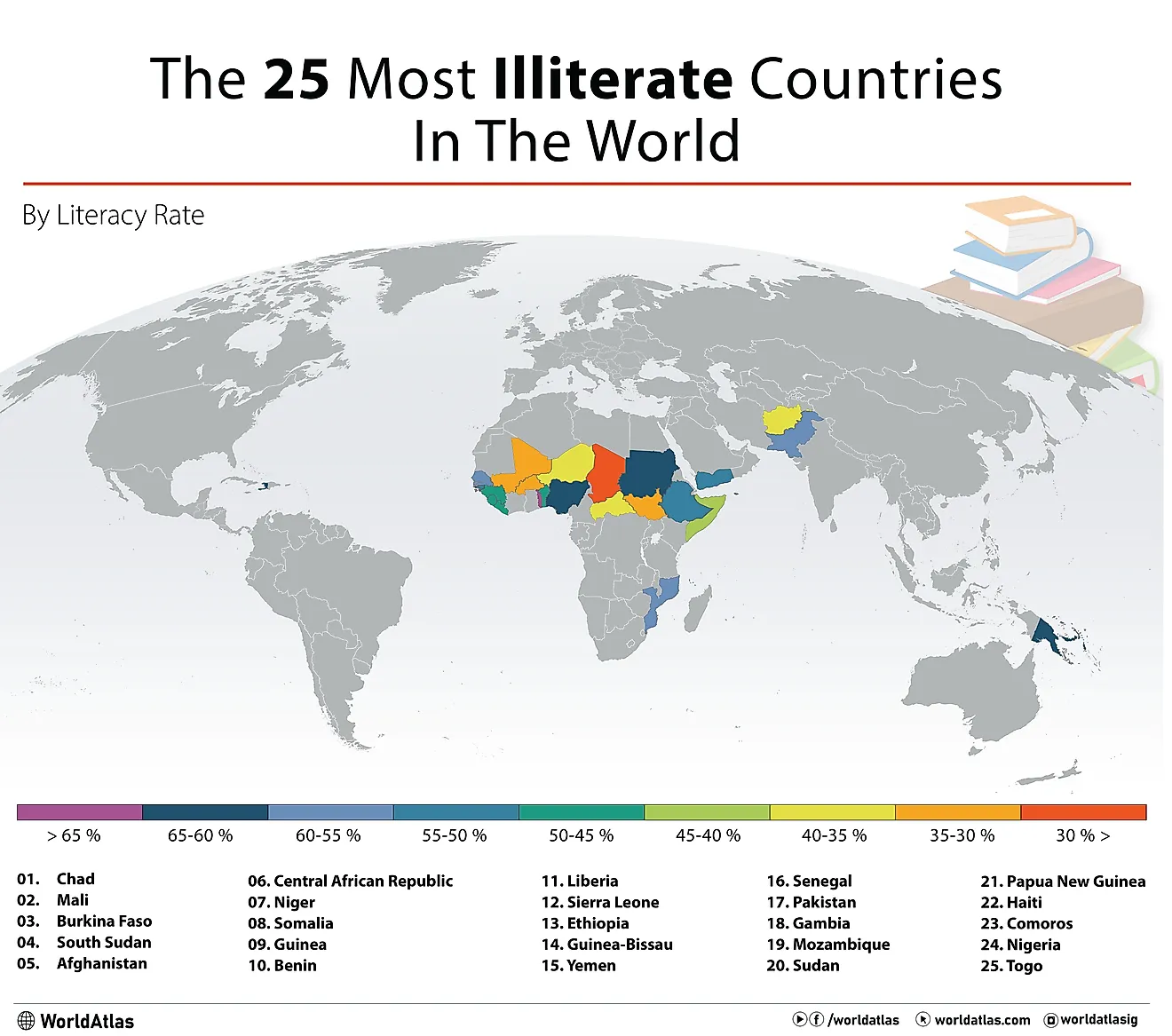

25 Most Illiterate Countries

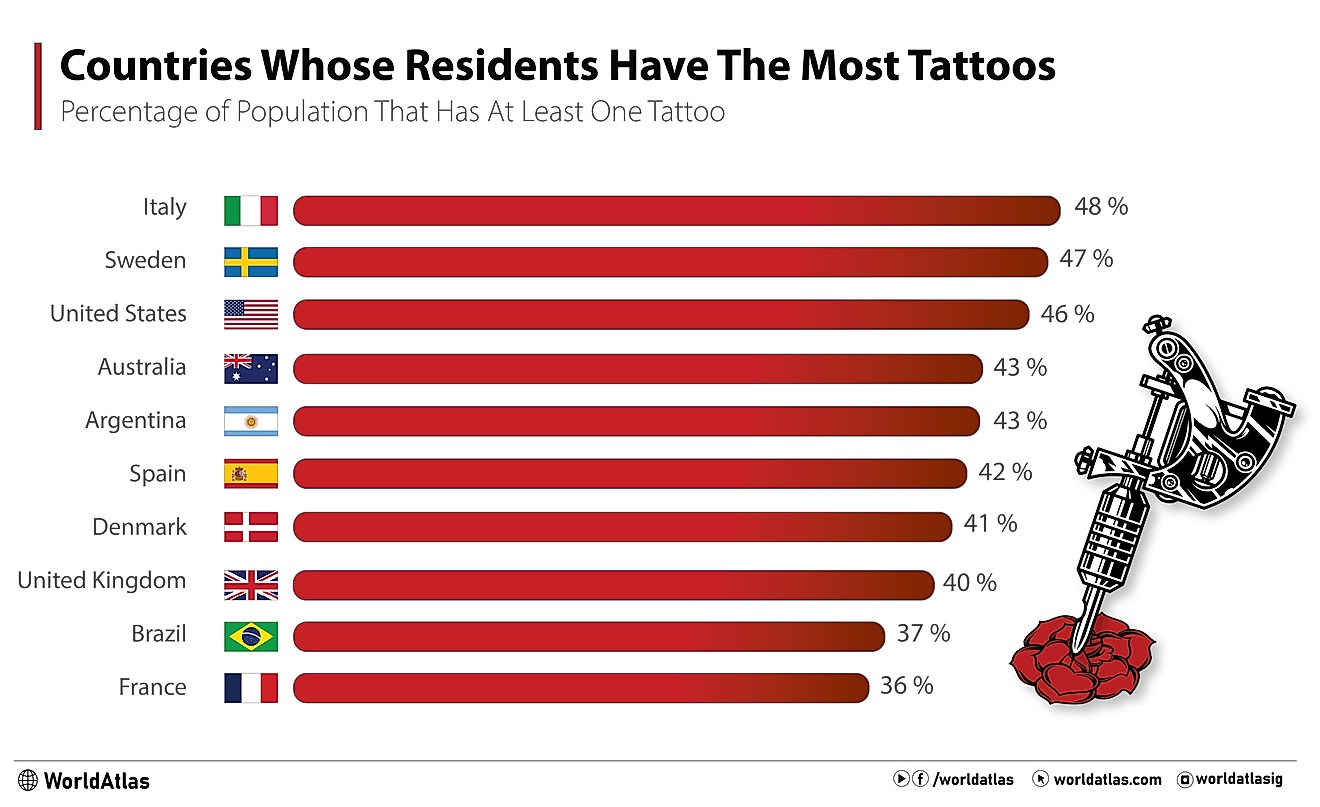

Which Country's Residents Have the Most Tattoos?

Alan Watts' Guide To The Meaning Of Life

Did Nietzsche Believe In Free Will?

Is Metaphysics The Study Of Philosophy Or Science?

5 Islamic Scientific Ideas That Changed The World

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

Genetic engineering debate: Should human cloning be legal?

Source: Composite by G_marius based on University of Michigan School of Natural Resources image

Human cloning is possible but unlawful in most countries. We discuss the pros and cons of genetic engineering and cloning, and whether it should be legal. This is your opportunity to convince other people to support or oppose to human cloning. Leave your comments below.

What is human cloning?

Human cloning refers to the creation of replicas or identical copies of human through genetic engineering techniques . Human cloning was a popular theme in science fiction literature but technological progress has made possible the clonation of species. Scientists have already managed to successfully clone plants and animals and in theory using similar technologies they could also create copies of humans. There are two processes through which humans could be in theory cloned:

- Somatic cell nuclear transfer : This technique consists of removing the genetic material from a host egg cell, and then implanting the nucleus of a somatic cell (from a donnor) into this egg. The somatic cell genetic material is fused using electricity. This was the technique employed to clone the famous sheep Dolly in 1996.

- Induced pluripotent stem cells : This approach relies on adult cells that have been genetically reprogrammed. A specific set of genes, usually referred to as "reprogramming factors", are introduced into a specific adult cell type. These factors send signals in the adult cell transforming it into a pluripotent stem cell . This technique is still in development and entails some problems but it has already been employed with mice.

The impact that human cloning could have on our societies and future populations have made this topic extremely controversial . Although there are many pros in terms of innovation, reproduction and health, there are also several drawbacks from the ethical and legal perspective. Many countries such as the Australia, Canada, and the United Nations have already passed laws to ban human cloning. However, the issues is far from being settled. Many voices are arguing in favor of human cloning and others are stauch opponents to the legalization of this practice.

Pros of human cloning

Many science fiction movies, such as Gattaca , The Island or Moon have dealt with the implications of genetic engineering and human cloning. Most of them have portrayed a somewhat dystopian future and emphasize the problems of genetic manipulation. However, it is also important to stress the potential benefits of human cloning. Here is a list of its pros :

- Reproduction of infertile couples: using human cloning techniques parents could have babies without needing a donnor or a surrogate.

- Defective genes could be eliminated.

- Genetic modification : parents could decide on some characteristics of their children before they are born, such as the sex, and avoid some congenital disease.

- Prevent some genetic disorders and syndromes: some families have a propensity to certain genetic disorders, some of which could be prevented by genetic selection.

- Cure some diseases and disorders: therapeutic human cloning may allow cloning organs and tissues and replacing damaged ones. This would contribute to increase lifespams and quality of life in the world.

Cons of human cloning

On the other hand we cannot omit the dangers that human cloning may bring to our societies. This is a list of some of the most commonly argued cons :

- Create divides within society: genetically selected people could be, in theory, more intelligent and physically attractive than other people. This could gradually evolve into a caste system.

- Diversity could be lost if parents would choose similar patterns in selecting the genetic material for their children.

- Faster aging and in-built genetic defects: until cloning technology is fully polished, human cloning may create many problems. Since older cells are often used to create clones this could produce premature aging for people. Moreover animal clones have usually been unhealthy.

- Interference with nature and religion: many people find human cloning to be artificial and to be at odds with their beliefs. Human clones could, thus, be stygmaized.

- Unlawful use of clones: as in some science fiction movies and books, clones could be created just as for the purpose of economic gain. Certain types of humans could be created to work on certain jobs, even under abusive conditions. Clones could be also brought up for unlawful activities.

Do you think the pros of human cloning outweigh its cons? Should we allow scientists to clone humans (or parts of humans) for therapeutic and or reproductive reasons?

Vote to see result and collect 1 XP. Your vote is anonymous. If you change your mind, you can change your vote simply by clicking on another option.

Voting results

New to netivist?

Join with confidence, netivist is completely advertisement free. You will not receive any promotional materials from third parties.

Or sign in with your favourite Social Network:

Join the debate

In order to join the debate you must be logged in.

Already have an account on netivist? Just login . New to netivist? Create your account for free .

Report Abuse and Offensive language

Was there any kind of offensive or inappropriate language used in this comment.

If you feel this user's conduct is unappropriate, please report this comment and our moderaters will review its content and deal with this matter as soon as possible.

NOTE: Your account might be penalized should we not find any wrongdoing by this user. Only use this feature if you are certain this user has infringed netivist's Terms of Service .

Our moderators will now review this comment and act accordingly. If it contains abusive or inappropriate language its author will be penalized.

Posting Comment

Your comment is being posted. This might take a few seconds, please wait.

Error Posting Comment

error.

We are having trouble saving your comment. Please try again .

Most Voted Debates

| Rank | |

|---|---|

Start a Debate

Would you like to create a debate and share it with the netivist community? We will help you do it!

Found a technical issue?

Are you experiencing any technical problem with netivist? Please let us know!

Help netivist

Help netivist continue running free!

Please consider making a small donation today. This will allow us to keep netivist alive and available to a wide audience and to keep on introducing new debates and features to improve your experience.

- What is netivist?

- Entertainment

- Top Debates

- Top Campaigns

- Provide Feedback

Follow us on social media:

Share by Email

There was an error...

Email successfully sent to:

Join with confidence, netivist is completely advertisement free You will not recive any promotional materials from third parties

Join netivist

Already have a netivist account?

If you already created your netivist account, please log in using the button below.

If you are new to netivist, please create your account for free and start collecting your netivist points!

You just leveled up!

Congrats you just reached a new level on Netivist. Keep up the good work.

Together we can make a difference

Follow us and don't miss out on the latest debates!

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Human Cloning, Should It Be Banned or Legalized? Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2136

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Introduction

Human cloning has emerged to be among the greatest ethical debates in our era, with most states expressing their opposition or acceptance in the process. In some states, cloning is illegal while others are still debating on its scientific and social impacts. In addition, most federal institutions in the US are prohibited from practicing human cloning, even at experimental levels (Haugen & Musser, 2008). One fact, however, that needs to be placed under consideration is that the cloning technology is already here, and either way, at some point human clones would be acceptable to help in elongating human genetic lines.

In biology, cloning refers to the process of producing populations that look alike with identical genetics that happens naturally when organisms such as plants, insects or bacteria reproduce asexually (Langwith, 2012). In biotechnology, cloning refers to the processes employed to develop copies of DNA portions of organisms or cells. The term also means the making of many copies of a product like software or digital media.

The term ‘clone’ originates from the early Greek word “twig”, which refers to the process whereby new plants can be developed from a twig. Horticulturalists applied the spelling “clon” until the twentieth century, the last ‘e’ was added to show that the vowel is a ‘long o’ and not a ‘short o’. Since the word entered the popular glossary in a more common context, the spelling “clone” has been applied exclusively. Botanists traditionally used the term ‘lusus’.

The United States’ Department of Food and Drugs Administration approved the human consumption of meat and any other products from cloned animals on December 28, 2006, with no unique labeling needed because food from cloned animals had been proved to be the same to the organisms from which they were cloned. Such practice has received strong opposition in other places due to misinformation, like Europe, in particular over the issue of labeling (Feight & Zukairat, 2009).

Many ethical myths such as the role of God, the soul as well as the quality of life that the clones would live has become the basis for many arguments against cloning. Such persons also need to put into consideration the positive aspects of cloning such as quick medical interventions, long life spans, and better life quality. This speech explores into the pros and cons of cloning, putting into consideration both the technological and the social impacts that it will cause. Relatively, this paper seeks to answer the questions as to whether cloning would help the society and whether it is ethically responsible to clone humans to create new lives. Through reference to a number of animal cloning instances, the speech will consider the effectiveness and levels of benefits that were accrued from such clonings.

History of Cloning

The success in animal cloning formed the basis of the heated argument regarding human cloning in the contemporary world. Various attempts have been made in regards to human cloning, and they have revealed a great success. Dolly the sheep is the world most famous cloned animal known. The sheep were cloned through somatic nuclear transfer from the udder cell of a six-year-old sheep in the year 1996 after 276 failed attempts. To make Dolly, researchers isolated a somatic cell from adult female sheep. Next, they removed the nucleus and all its DNA from an egg cell. Then they moved the nucleus from the somatic cell to the egg cell, after a couple of chemical tweaks, the egg cell, with its new nucleus behaved like a freshly fertilized egg. It developed into an embryo, which was implanted into a surrogate mother and carried to term. Since the successful attempt of animal cloning, various experiments has been placed under way to shed more light on this process.

Applications of Animal Cloning

Xenotransplantation; Involve transplantation of nonhuman tissues or organs into human recipients. Increasing demand for human organs has led to the adoption of this method as an alternative. The only obstacle is immunological responses which may lead to rejection of these organs by the body (Winters, 2007). However, researchers are still working on various ways through which such immunological responses can be addressed so as to make the complete process a success.

Breeding endogenic body tissues; Modern study shows that organs from cloned pigs produce organs that can be used in a human transplant. Pig organs are approximately similar to those of humans, including plumbing regions. The only problem using pig’s organs is that they are coated with sugar molecules and trigger acute rejection in humans. Scientists are however working to produce pigs that produce sugar lacking genes through cloning (Winters, 2007). The success of this technology would bring about a great breakthrough in the area of human cloning.

Animal models; The technique has been used to create models of human diseases. Hepatitis C virus a very persistent disease can not be proficiently propagated in cell cultures, researchers have heavily relied on the animal model to study physical characteristics of HCV and events associated with its infections. This has been done in molecular cloning of HCV genome in chimpanzees (Roleff, 2006).

Pros of Human Cloning

Despite the many hullabaloos that surround cloning, it is important to consider its positive impacts on the livelihood of human nature. There are plethoras of payback that come with human cloning; some of which include the following:

Elimination of defective genes; Genetic illness may not be the leading killers today, but there are chances of them developing into major killers in future. As human reproduction progresses, there are many damages that occur on their DNA lines. As a result, defective genes and mutations could occur and ruin the quality of lives. However, with the cloning technology, such defective genes and mutations can be eliminated to improve the quality of lives for these people (Johnson, 2008).

Enhances quick healing from traumatic injuries; certain life happenings such as fatal accidents and life conditions often result into trauma for the victims. Recovery from such traumatic injuries may take long depending on the cause of harm. This situation is likely to change with the introduction of cloning technology since the victims would have their own cells cloned and used in replacing the injured parts. This would even hasten the healing process.

Quite a solution to infertility; In spite of many infertility treatments being successful, cloning provides a quick and most efficient solution to infertility (Haugen & Musser, 2010). Imagine creating a twin brother or sister of your infertile partner from the clone and beginning a new family; it feels good and many people would prefer it to undergoing the painful process of infertility treatment.

Cons of Human Cloning

Despite the above benefits, many religious and social activists largely condemn the act of human cloning for a number of reasons. Most of these revolve around the supremacy of God as well as the quality of lives that the clones would live. Here are some of the issues that largely demean the art of human cloning.

Possibilities of quick aging; Cloning involve taking older human cells and using them to create new ones. There are often many possibilities that the developing embryo would adopt the imprinted age, and as a result cause premature aging issues (Haugen & Musser, 2008). In some instances, the clones would succumb to premature deaths. This makes human cloning a great peril to the social livelihood.

Cloning lowers the individual’s sense of humanity. A human clone may be a new life, having unique preferences, however, the clone is simply a twin of another person, and no matter the age, there would be a potential personality loss, which makes the process inefficient.

Reduction in human life value; with the existence of cloning, humans are likely to become more of commodities than living beings (Macintosh, 2009). For instance, if you do not like behavior or something else in your child, you simply clone another and only make sure the problem is solved this time round. With this type of life, new societal divisions could be created, in which perfect clones, are treated better than the humans got through the natural process.

Most religious activists also view human cloning as an act that largely diminishes the role of God in creation. Some of the many questions that may remain unanswered include whether the human soul exists and whether it is lost during cloning. Most of these revelations would be contrary to the religious beliefs of many people, hence causing a stir in the social beliefs.

Considering the above pros and cons of human cloning, both sides of argument hold sufficient weight and justify their stand. It is, however, a fact that the ban or illegality of human cloning would just be momentary since most technological advances would automatically embrace this new culture (Haugen & Musser, 2010). The increasing practice of animal cloning is increasingly becoming extensive and given more time, human cloning would suffice. The major successes achieved in the field of cloning over the past two centuries have been remarkable. Given the pros of human cloning, it is evident that its practice would be upheld and many nations may come up with universal laws concerning the art of human cloning. Despite the bone of contention regarding its applicability within the current social system, the practice will gradually increase hence creating the demand for its applicability. Human cloning may come with activities that are contrary to many social norms, however, the benefits also needs to be emphasized on.

Barber, N. (2013). Cloning and genetic engineering.New York: Rosen Publishing’s Rosen Central.

Feight, J., & Zuraikat, N. (2009). Cloned food labeling: History, issues, and bill S. 414.International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 3(2), 149-163.

Fiester, A. (2005). Ethical Issues In Animal Cloning. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 48(2), 328-343.

Haugen, D. M., & Musser, S. (2008). Human embryo experimentation . Detroit: Greenhaven Press.

Haugen, D. M., & Musser, S. (2010). Technology and society . Detroit: Greenhaven Press.

Johnson, J. A. (2008). Human cloning . Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

Macintosh, K. L. (2009). Illegal Beings Human Clones and the Law . Leiden: Cambridge University Press.

Wimmer, T. (2009). Cloning: Dolly the sheep . Mankato, MN: Creative Education.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Analyzing an Author’s Life Experiences, Essay Example

Apple Inc Strategic, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

© Getty Images

Should human cloning be allowed?

A Nobel Prize-winning scientist has claimed that human cloning could become a reality within the next 50 years.

The British biologist Sir John Gurdon carried out pioneering frog cloning work during the 1950s and 60s – research which led to the creation of Dolly the sheep in 1996.

During an appearance on BBC Radio 4’s The Life Scientific , Gurdon said that the time period between his cloned frogs and Dolly the sheep could be similar to the time we have to wait until the first human clone.

He said: "When my first frog experiments were done, an eminent American reporter came down and said 'How long will it be before these things can be done in mammals or humans?'”

"I said: 'Well, it could be anywhere between 10 years and 100 years – how about 50 years? It turned out that wasn't far off the mark as far as Dolly was concerned. Maybe the same answer is appropriate."

Advocates of human cloning argue that it would have important uses, such as allowing parents to clone a child who’s been tragically lost in an accident or through illness. The technology could also allow scientists to grow replacement tissues and organs that are accepted by the body without the need for immunosuppressive drugs.

On the flipside, critics highlight the fact that many cloned animals end up being deformed, warning that human clones could be similarly damaged. Others worry that cloning might lead to a loss of human dignity and individuality, as vividly depicted in Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World .

Despite such complex ethical issues, however, Gurdon believes that human cloning would soon be accepted by the public if it turns out to have valuable medical uses.

- What’s the biological difference between identical twins and clones?

- Could we clone a mammoth or a dinosaur?

Follow Science Focus on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and Flipboard

Share this article

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

You are now being redirected to goldpdf.site....

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 21 March 2017

The global governance of human cloning: the case of UNESCO

- Adèle Langlois 1

Palgrave Communications volume 3 , Article number: 17019 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

71k Accesses

10 Citations

135 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Politics and international relations

- Science, technology and society

Since Dolly the Sheep was cloned in 1996, the question of whether human reproductive cloning should be banned or pursued has been the subject of international debate. Feelings run strong on both sides. In 2005, the United Nations adopted its Declaration on Human Cloning to try to deal with the issue. The declaration is ambiguously worded, prohibiting “all forms of human cloning inasmuch as they are incompatible with human dignity and the protection of human life”. It received only ambivalent support from UN member states. Given this unsatisfactory outcome, in 2008 UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) set up a Working Group to investigate the possibility of a legally binding convention to ban human reproductive cloning. The Working Group was made up of members of the International Bioethics Committee, established in 1993 as part of UNESCO’s Bioethics Programme. It found that the lack of clarity in international law is unhelpful for those states yet to formulate national regulations or policies on human cloning. Despite this, member states of UNESCO resisted the idea of a convention for several years. This changed in 2015, but there has been no practical progress on the issue. Drawing on official records and first-hand observations at bioethics meetings, this article examines the human cloning debate at UNESCO from 2008 onwards, thus building on and advancing current scholarship by applying recent ideas on global governance to an empirical case. It concludes that, although human reproductive cloning is a challenging subject, establishing a robust global governance framework in this area may be possible via an alternative deliberative format, based on knowledge sharing and feasibility testing rather than the interest-based bargaining that is common to intergovernmental organizations and involving a wide range of stakeholders. This article is published as part of a collection on global governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Dutch perspectives on the conceptual and moral qualification of human embryo-like structures: a qualitative study

Rights, interests and expectations: Indigenous perspectives on unrestricted access to genomic data

Crispr in context: towards a socially responsible debate on embryo editing, introduction.

UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) was founded in 1945, aiming to “build peace in the minds of men” through education, science, culture and communication ( UNESCO, 2007 ). Its Bioethics Programme began in 1993. The organization deems itself uniquely placed to lead the way in setting bioethical standards, as the only UN agency with a mandate for both the human and social sciences ( UNESCO, 2016e ). To this end, it has adopted three declarations on bioethics: the 1997 Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights (UNESCO, 1997), the 2003 International Declaration on Human Genetic Data (UNESCO, 2003) and the 2005 Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (UNESCO, 2005b). After drafting three declarations in the space of a decade, UNESCO decided to take a “normative pause” and instead focus on fostering take-up of the existing declarations regionally and nationally ( UNESCO, 2005a ). Before long, however, it started to consider a fourth bioethics instrument, an international convention on human cloning. From 2008 to 2011 it investigated whether an international convention to ban human reproductive cloning is warranted. The Working Group assigned to this question “flip-flopped” back and forth: in 2008 it recommended a convention, in 2009 it decided continued international dialogue would be sufficient and in 2010 it went back to a convention. As member states could not agree on a way forward, the issue was dropped in 2011 without a firm decision being made on the need or otherwise for a convention. This can be seen as a global governance failure. In 2014, the Bioethics Programme began to revisit the issue. This time there was greater consensus on the need for a ban on human reproductive cloning, but no practical progress has been made.

This article takes a traditional global governance scenario—a debate within a UN agency about whether to draft an international convention—and asks why the outcome was unsatisfactory. The analysis draws on first-hand observations of UNESCO’s publicly held bioethics meetings in 2010 and 2011, official UNESCO records of these and other meetings and UNESCO reports on human cloning. After a brief introduction to (a) developments in global governance and (b) the science and ethics of human cloning, the article charts the progress and ultimate collapse of the UNESCO cloning debate from 2008 to 2011 and developments from 2014 onwards. It concludes that, although human reproductive cloning is a challenging subject, establishing a global governance framework in this area may be possible via an alternative deliberative format.

Global governance

Ruggie (2014 : 5) defines governance as “systems of authoritative norms, rules, institutions, and practices by means of which any collectivity, from the local to the global, manages its common affairs”. At the global level these systems, particularly within formal intergovernmental settings such as UNESCO, are increasingly seen to be inadequate, with scholars variously describing them as “facing a deep crisis” ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 737), “suboptimal” ( Ruggie, 2014 : 15) and suffering the “pathologies” of gridlock, fragmentation, disconnect between related issue areas and conflicts of interest ( Pegram and Acuto, 2015 : 586). The old, hierarchical model of multilateral governance is considered too rigid ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 737) and to have “limited utility in dealing with many of today’s most significant global challenges” ( Ruggie, 2014 : 8). Traditional intergovernmental organizations have not adapted to the increasing complexity of society and the ensuing need for flexible regulatory mechanisms that can keep pace with scientific development ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 742–743).

These problems have led to changes and innovations in both the theory and practice of global governance ( Ruggie, 2014 ; Weiss and Wilkinson, 2014 ; Pegram and Acuto, 2015 : 588). As Pauwelyn et al. (2014: 734) note, “Formal international law is stagnating in terms of both quantity and quality. It is increasingly superseded by ‘informal international lawmaking’ involving new actors, new processes, and new outputs”. They refer to this stagnation as “treaty fatigue” ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 739). The international system is becoming more pluralist and less dominated by sovereign states pursuing narrow interests. There has been movement towards voluntary rather than binding regulation, as well as capacity building ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 736; Pegram and Acuto, 2015 : 591). Particularly for emerging areas, such as the internet, regulation has been informal, with no discussion of a legally binding treaty ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 738). In turn, a “second generation” of global governance scholarship, which recognizes the complexity of global governance in a changed global context, is focusing less exclusively on intergovernmental politics. In the introduction to their special issue of Millennium on global governance’s “interregnum”, Pegram and Acuto (2015 : 586 and 588) predict a “more innovative global governance research and practice-oriented agenda” and a transition to “a potentially more pluralist (and hopefully more democratic) intellectual and practical ecosystem, as well as to new structures of power”. This article applies some of these new practices and ideas to UNESCO’s human cloning debate, answering Pegram and Acuto’s call for “more empirical research” ( Pegram and Acuto, 2015 : 595).

Human cloning and its current international regulation

Although the idea of human cloning excites strong views, there is much confusion about what it would actually entail. Cloning can take two forms: “reproductive” cloning and “therapeutic” or “research” cloning. These terms are not scientifically accurate, but are commonly used nevertheless. They stem from the process of somatic cell nuclear transfer, whereby an enucleated egg receives a nucleus from a somatic (body) cell. In reproductive cloning, the embryo is implanted into a female for gestation. Through this method, Dolly the Sheep became the first mammal to be cloned in July 1996. In therapeutic cloning, an embryo is harvested for stem cells rather than brought to term ( Wilmut et al., 1998 : 21; Bowring, 2004 : 402–403; Isasi et al., 2004 : 628; United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies, 2007 : 6). Although therapeutic cloning is held by many to have great potential medically, as a source of compatible tissue and organs for those who need transplants, it generates considerable controversy. For people who see human life as beginning at fertilization, therapeutic cloning is also reproductive ( Isasi et al., 2004 : 628; Lo et al., 2010 : 17).

Since the cloning of Dolly the Sheep, ethicists, lawyers and scientists have argued vigorously both for and against developing this technology for use in humans. Those in favour draw on liberal values, citing reproductive freedom, or hope that cloning will provide a new means to tackle infertility. Those against fear for the psychological health of the clone, who would be unable to enjoy what they see as the inherently human quality of having a unique identity. Clones might be expected by their “parents” to conform to a particular life pattern, or feel shackled by knowing about the life of the person from whom they were cloned. Those on both sides mostly agree that, based on the poor success rate in animal cloning and the potential health risks to mother and child, on safety grounds it would be unethical to attempt human cloning currently ( Kass, 1998 : 694–695; Robertson, 1998 : 1372, 1410–1411 and 1415–1416; Burley and Harris, 1999 : 110; de Melo-Martín, 2002 : 248–250; Harris-Short, 2004 : 333 and 344; Tannert, 2006 : 239; Mameli, 2007 : 87; Morales, 2009 : 43; Shapsay, 2012 : 357; The Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2012 : 804–805; Wilmut, 2014 : 40–41).

Many countries have banned reproductive and/or therapeutic cloning. In most cases, their laws refer to somatic cell nuclear transfer rather than cloning more generally and thus newer technologies are not covered ( Lo et al., 2010 : 16). Several international and regional measures also prohibit human reproductive cloning: UNESCO’s 1997 Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights (UNESCO, 1997), the World Health Organization’s resolutions of 1997 and 1998 on the implications of cloning for human health (WHO, 1998), the Council of Europe’s 1998 Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, on the Prohibition of Cloning Human Beings (Council of Europe, 1998) and the European Union’s 2000 (amended 2007) Charter of Fundamental Human Rights (European Union, 2012). As the Council of Europe’s protocol has been ratified by only 23 of its 47 member states, the EU Charter is limited to the enactment of EU law and UNESCO’s declaration is by definition non-binding, none of these represent an absolute ban ( Council of Europe, 2016 ; European Commission, 2016 ). Hence, at the request of France and Germany, in 2001 the UN General Assembly began to deliberate on a binding treaty to prohibit human reproductive cloning. Four years of dispute and discord followed. Some states were concerned that an embargo on reproductive cloning specifically would implicitly endorse therapeutic or research cloning, whilst those wishing to pursue therapeutic cloning could not support a holistic ban. With agreement on a binding convention seemingly elusive, the General Assembly opted for a non-binding declaration. The United Nations Declaration on Human Cloning was duly adopted on 8 March 2005, but not unanimously. 84 states voted in favour, 34 voted against and 37 abstained ( Arsanjani, 2006 ; Isasi and Annas, 2006 ; Cameron and Henderson, 2007 ). The declaration, rather ambiguously, calls on states to “prohibit all forms of human cloning inasmuch as they are incompatible with human dignity and the protection of human life” ( United Nations, 2005 ). It is considered too weak an instrument to either thwart rogue research or promote legitimate scientific endeavour ( Isasi and Annas, 2006 : 63; United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies, 2007 : 19).

The UNESCO Bioethics Programme

The UNESCO Bioethics Programme began in 1993 with the formation of the International Bioethics Committee (IBC), made up of independent experts. An Intergovernmental Bioethics Committee (IGBC), comprising state representatives, followed in 1999. Each committee has 36 members. The IBC meets yearly and the IGBC biennially. Regular joint meetings of the two committees are also held. The IBC has various functions, including promoting bioethics education and reflection on ethical issues. The IGBC’s mandate is to examine the recommendations of the IBC and report back to the Director-General of UNESCO ( UNESCO, 1998 ). The IBC works on the basis of 2-year Work Programmes (human cloning, for example, featured in the 2008–2009 and 2010–2011 programmes), with reflections on particular topics being drafted by specially appointed Working Groups, comprising a small number of IBC members, over the 2-year cycle. Each Group presents their work-in-progress at IBC and IGBC meetings and takes the views expressed at these meetings into account in their final reports.

Scholars from both within and without the Bioethics Programme have analysed its efficacy as a forum for ethical debate and standard-setting. Footnote 1 These analyses have mostly focused on the negotiation of the 2005 Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights . The interest-based bargaining often seen within intergovernmental organizations led to vague wording on beginning and end of life issues and risk assessment, while controversial issues such as sex selection, gene therapy and stem cell research were left out entirely, as states could not reach a consensus on these ( Schmidt, 2007 ; Langlois, 2013 ). UNESCO claims that its status as an intergovernmental body differentiates it from ethics institutions outside of the UN like the World Medical Association, a professional body ( ten Have, 2006 : 342). However, there has been a lack of buy-in from the global bioethics community, particularly academics, who have questioned the expertise and representativeness of the IBC ( Cameron 2014 : 237 and 240). The lack of enforcement power of the 2005 declaration, as a non-binding instrument, has also been noted. Yet Cameron (2014 : 252 and 261) argues that declarations have advantages over conventions, because of their reliance on moral persuasion and their inclusivity in comparison to conventions, which are only binding on those states that accede to them. UNESCO suffered a major setback in 2011, when the United States withdrew funding in light of Palestine’s admittance as a member state, a cut of 22 per cent of the operational budget ( UNESCO, 2011e ; UNESCO, 2013a ). 2 The Bioethics Programme has emerged relatively unscathed, however, as its budget allocation has largely been protected (UNESCO, 2013c; UNESCO, 2016a ).

The human cloning debate at UNESCO 2008–2011

At the request of then Director-General of UNESCO, Koïchiro Matsuura, in 2008 the IBC decided to investigate the possibility of a convention on human cloning and appointed a Working Group on Human Cloning and International Governance ( UNESCO, 2009a : 1–2). This was a response to the publication of a report the previous year by the United Nations University’s Institute of Advanced Studies, entitled Is Human Reproductive Cloning Inevitable: Future Options for UN Governance . The Working Group was tasked with reviewing “whether the scientific, ethical, social, political and legal developments on human cloning in recent years justify a new initiative at international level”, rather than examining the ethics and science of human cloning per se or drafting a legal text ( UNESCO, 2008a : 1). The IBC and IGBC meetings where human cloning was discussed took place as follows: ( Table 1 )

The Working Group’s first report was an interim report, published in September 2008. It recommended a new, binding international convention to ban human reproductive cloning ( UNESCO, 2008b : 4). The report was discussed the following month by the IBC and IGBC (the IBC met for 2 days by itself and then jointly with the IGBC for 2 days), where it was given an ambivalent reception. Many participants did not believe there had been sufficient change in national positions to avoid a repetition of the fractious debate and unsatisfactory outcome at the UN General Assembly a few years before. On the other hand, some delegates underlined the potential utility of a convention for those developing countries yet to legislate on cloning ( UNESCO, 2010a : 6 and 12). In response to these discussions, the Working Group was more cautious in its final report of June 2009. Judging that the introduction of a new international normative instrument would be premature, it recommended increased global dialogue as an alternative ( UNESCO, 2009a : 7). This suggestion was commended by the IGBC at its July 2009 meeting, with several participants noting that developing countries that do not have “a well-developed national bioethics infrastructure” would benefit particularly from international level debate ( UNESCO, 2009b : 4).

The cloning mandate continued into the next Work Programme of 2010–2011. After discussion at its November 2009 meeting and on the advice of the IGBC, the IBC instructed an expanded Working Group to continue its work on cloning by examining three issues: (a) the ethical impact of terminology (b) dissemination activities and (c) regulation of human reproductive cloning (including by moratorium). The Working Group duly delivered a draft report to the IBC and joint IBC–IGBC meetings of October 2010. On options for regulation, it found that a more robust instrument on human reproductive cloning than existed currently was needed, such as an international convention or moratorium ( UNESCO, 2010b : 1 and 6). The reception from the IBC and IGBC was again mixed, as reported by the UNESCO website:

IBC members were unequivocal in expressing concern that the recent scientific developments have raised a need for a binding international legal instrument. However, feedback by Member States of IGBC was indicative that the political hurdles that have prevented the realization of such instrument in the past are still in place. [ sic ] ( UNESCO, 2016b )

As noted in the official record of the IBC-only meeting, members considered it “imperative” that binding international law to ban human reproductive cloning be put in place ( UNESCO, 2011d : 6). By contrast, within the joint IBC–IGBC meeting that followed, the US delegation was perplexed as to why the possibility of a convention was “back on the table”, after it had seemingly been rejected in the 2008–2009 Working Group’s final report. It advocated ongoing dialogue instead, alongside support for states developing national regulations on cloning. Germany and Brazil also backed the status quo, prompting one IBC member to ask why in 2010 they believed a convention to be premature, when in 2001, the year the idea was first put to the UN, they had thought one timely. Meanwhile, some developing countries stated their desire for a convention on cloning (but not necessarily a prohibitive one) (personal observations, Joint Session of the IBC and IGBC, October 2010). Given the diversity of views, it was left that the IGBC would “thoroughly examine the issue” at its next session (to be held in September the following year), after the IBC, via the Working Group, had finalized its report (UNESCO, 2016b).

The IBC held its next meeting in May–June 2011, at which the Working Group presented a draft “final statement” rather than a finalized version of the draft report of the previous year. This statement repeated the recommendations of the 2010 draft report, emphasizing that developing countries that do not have national regulations on human reproductive cloning are in particular need of a binding international convention or moratorium. In addition, it suggested that “technical manipulations of human embryo, either for research or therapeutic purposes” [ sic ] (that is, what is commonly known as therapeutic or research cloning) should carry on being regulated at domestic level, in accordance with social, historical and religious contexts ( UNESCO, 2011b : 3). The IBC chose not to adopt the statement because of the now “divergent positions” of its members on both the ethics and governance of cloning ( UNESCO, 2011c : 4). At the ethical level, some members were not convinced that the potential for detrimental genetic determinism was a strong enough argument against reproductive cloning, whilst at the political level, some felt the committee could make little progress while consensus among states remained elusive (personal observations, Eighteenth Session of the IBC, May–June 2011).

At the IGBC’s September 2011 meeting, the outgoing IBC Chair reported on his committee’s activities. With regard to the cloning debate, he explained that despite some members having wanted to go to a vote on whether to adopt the Working Group’s draft statement, he had opposed this, because the IBC had always operated by consensus in the past. He also expressed his belief that consensus on a ban will always be impossible to achieve, because at its core the issue is philosophical rather than scientific, concerning the status of the early embryo. IGBC delegations agreed for the most part, the United States, Austria and Denmark echoing IBC members in predicting that further efforts to reach an agreement on regulation would prove fruitless (personal observations, Seventh Session of the IGBC, September 2011). The official conclusions of the meeting noted the topic’s ongoing importance, but also the absence of any consensus among both states and IBC members. Hence the IGBC merely called on UNESCO “to continue to follow the developments in this field in order to anticipate emerging ethical challenges” ( UNESCO, 2011a: 3 ). Subsequently, the 2012–2013 IBC Work Programme consigned cloning to monitoring by a few IBC members, who were in turn to report any significant developments in the field to the committee and thereby the Director-General of UNESCO ( UNESCO, 2016f ).

After 4 years of work and discussion, then, UNESCO’s inability to come to a consensus on whether or not a convention to ban human reproductive cloning would be desirable meant that a decision against a convention was made by default. The Working Group’s draft final statement of 2011 had concluded, “The current non-binding international regulations cannot be considered sufficient in addressing the challenges posed by the contemporary scientific developments and to safeguard the interests of the developing countries that still lack specific regulations in this area” ( UNESCO, 2011b : 3). If this is the case, UNESCO’s failure to meet the need identified by its Working Group is problematic, as there is a governance gap.

2014–2015 developments

In its 2014–2015 Work Programme the IBC revisited the topic of human cloning as part of its wider efforts to update its earlier work on the human genome and human rights. The June 2015 draft report of the Working Group appointed to this task reiterated the need for a ban on human reproductive cloning. It also called for “a global forum of scientists and bioethicists, under the auspices of the United Nations” to investigate what the consequences of new genomic technologies might be and stated, “The United Nations should be responsible for making fundamental normative decisions. The precautionary principle should be respected, ensuring that substantial consensus of the scientific community on the safety of new technological applications be the premise for any further consideration” ( UNESCO, 2015b : 25–27).

The IGBC, on reviewing this draft report at its July 2015 meeting (Ninth Session), found the IBC’s recommendations to be “pertinent and timely” (UNESCO, 2015a: 2). This was in marked contrast to the comments by some of its members a few years before that a ban on human reproductive cloning would be “premature” ( UNESCO, 2009a : 7). Perhaps wary of ceding “territory”, the IGBC stressed that UNESCO was the appropriate forum for discussion of a ban. In the official conclusions of the meeting, it also invited the Secretariat of the Bioethics Programme to “collect and compile existing legal models, case studies and best practices” on cloning and other issues relating to the human genome addressed in the report ( UNESCO, 2015a : 2–3). The draft was revised in light of the IGBC’s comments and then discussed and revised again at the IBC’s 22 nd Session in October 2015. The final version— Report of the IBC on Updating Its Reflection on the Human Genome and Human Rights —states that the UN should be responsible for fundamental normative decisions “through its several agencies and bodies and other possible procedures of consultation and evaluation” rather than a new global forum. It also asserts UNESCO’s position as a key player in the bioethics community, adding that, in terms of any revisions to existing declarations, “First of all, this is a task to perform for UNESCO, building on its well-established, pivotal role as a global forum for global bioethics” ( UNESCO, 2015c : 27–29).

The report addresses several issues that fall under the banner of the human genome and human rights, not just cloning. Nevertheless, cloning is prominent. The Executive Summary includes an “open list” of recommended actions for states and governments. The first item is: “Produce an international legally binding instrument to ban human cloning for reproductive purposes”. There are also recommendations for scientists and regulatory bodies, who are to “renounce the pursuit of spectacular experiments that do not comply with the respect of fundamental human rights” ( UNESCO, 2015c : 3–4). The main text expands on this, to state that such experiments should be discouraged (by not being allocated public funds, for instance) and in some cases prohibited, where there is no medical justification and a risk to safety. That this refers to cloning is made explicit, as follows: “Research on the possibility of cloning human beings for reproductive purposes remains the most illustrative example of what should remain banned all over the world” ( UNESCO, 2015c : 26). More generally, the report advocates a conservative approach to decision- and law-making that may be particularly relevant to human embryonic stem cell research, or “therapeutic cloning”. It encourages the adoption of legislation at international and national levels that is “as non-controversial as possible, especially with regard to the issues of modifying the human genome and producing and destroying human embryos”, to respect differing sensitivities and cultures ( UNESCO, 2015c : 3 and 6). Footnote 2 With regard to developing countries, the report acknowledges that they may not have major access to new genomic technologies in the near future, but recommends that LMIC (low and middle income country) governments develop national policies on genomics “within the context of their national economic and sociocultural uniqueness” ( UNESCO, 2015c : 29). The report also makes recommendations for “all actors of civil society”, including the media, educators and businesses. The former are to “avoid any sensationalism”, whilst the latter are not to chase profit by operating in countries with weak regulations ( UNESCO, 2015c : 3–4).

Hofferberth (2015 : 616) is critical of the assumption that “global problems are tractable and solutions feasible if actors will only come and work together to solve them”. As shown above, some members of the IBC and IGBC believed that the reason why they failed to reach consensus during the first 4 years of debate on human cloning (2008–2011) was the inherently irresolvable nature of the problem itself. But other controversial areas, such as business and human rights, have not proved immune to recent efforts towards policy and norm convergence ( Ruggie, 2014 : 6). Another possible explanation for the failure, then, is that the legal and organizational structures directing the deliberation did not lend themselves to consensual decision-making. In the early 2000s the UN General Assembly had found that the old model of state-based treaty negotiation did not work for human cloning, when it failed to agree on a convention and chose a non-binding declaration instead. UNESCO’s experience was similar, although it was not negotiations on treaty content that failed, but the preceding stage of deciding whether or not to attempt to draft a treaty. In raising the possibility of a convention in 2008, UNESCO was going against the emerging trend within global governance towards voluntary rather than binding regulation, combined with capacity building. Germany, for example, which was one of the states that originally espoused the idea of a human cloning convention at the UN in 2001, now looks for other, less rigid means by which the goals of a proposed treaty can be reached ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 739). Within UNESCO, as in other intergovernmental organizations, it is states that make the final decisions, so even if in 2011 the IBC (made up of independent experts) had continued to insist on the desirability of a convention, it would only have had the power to recommend to member states that they take the idea forward.

Pauwelyn et al. (2014 : 734) advocate “thick stakeholder consensus” over the “thin state consent” that is the hallmark of the old hierarchical approach to governance. As a treaty could be based on back-room deals between undemocratic states and yet be recognized as international law, they argue that formality is no guarantee of legitimacy, if the latter is assessed in terms of inclusiveness and effectiveness rather than tradition. Rather, the process by which agreement is reached is crucial, as well as the outcome. Careful, open and expert deliberation can lead to high quality outputs, which may or may not be legally binding ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 748–749). One way to achieve both process and output would be to loosen UNESCO’s understanding of “consensus”. By sticking to a rigid definition of consensus at its 2011 meeting, the IBC effectively gave each member a veto. Pauwelyn et al. (2014 : 754–755) contrast this type of arrangement with the “standards world” (that is, the International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission), which sits outside the intergovernmental system. Here, where governance is seen to be nimbler and more flexible than in traditional governance settings, “consensus” means that “the views of all parties concerned must be taken into any account and an attempt must be made to reconcile conflicting arguments”, so that general agreement can be reached. This level of consensus might be a more realistic target for the IBC and IGBC, enabling them to move forward.

One problem the Bioethics Programme has faced consistently is lack of time for in-depth discussion. At the IBC meeting in May–June 2011, for instance, the public session devoted to cloning lasted little more than an hour (although the committee later continued its discussions in a private meeting). This was not unusual. At the IGBC’s September 2013 meeting (Eighth Session), which reviewed 20 years of the Bioethics Programme, one delegate stated that their government would stop funding their attendance at such meetings unless more time were given to dialogue and papers were sent out early enough for delegates to consult with the relevant ministries on what position they should take (personal observations, Eighteenth Session of the IBC, May–June 2011 and Eighth Session of the IGBC, September 2013 4 ). The Bioethics Programme has already started to implement such changes. More time was allocated to each discussion topic at the IBC and joint IBC–IGBC meetings of September 2014 than at previous sessions, an online forum for past and present IBC members has been established and concept notes to invite written comments from the IGBC on the IBC’s work ahead of meetings have been introduced ( UNESCO, 2015d : 2 and 17).

If deliberations were to emulate recent innovations in other intergovernmental fora, they might be improved further. After its disappointing Copenhagen round in 2009, the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has moved from formal treaty negotiations that encouraged bargaining and confrontation to workshops and roundtables designed to foster knowledge exchange. This has resulted in “positive competitive dynamics” among states wishing to be leaders in the field of climate change mitigation ( Rietig, 2014 : 372–374). Other stakeholders have also been given a stronger voice; the Paris conference of 2015 made space for NGOs, businesses and cities to share best practices. Furthermore, the Paris Agreement of December 2015 takes a bottom-up approach, in that it is based on Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (pledged targets and actions) by individual states ( Busby, 2016 : 3, 4 and 7). Similarly, after the UN failed to adopt both a code of conduct and a set of norms on business and human rights after several years of trying, it piloted a different standard-setting method. Based on a series of site visits to firms and communities, extensive research and testing of key proposals through feasibility studies, pilot grievance mechanisms and scenario-based exercises, as well as multistakeholder consultations, the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights were endorsed by the Human Rights Council in 2011 and have since been adopted by several other bodies, including business associations. Ruggie (2014 : 5–6 and 10), who directed the consultation process, claims that producing the guiding principles through this “polycentric governance” enabled them to achieve the “thick” consensus advocated by Pauwelyn et al .

Ruggie (2014 : 10) argues that conceptual arguments must be supported by experiential ones if they are to persuade people of the need for change. The cloning debate is necessarily conceptual, as while questions over safety prevail there is no way to experience cloning to see whether fears (about autonomy and individuality, for example) are founded or unfounded. The closest proxies are animal cloning and twin studies. Yet sharing of national regulations and policies on cloning via workshops and roundtables and scenario-based exercises involving potential stakeholders would be feasible. Similar exercises (collating examples of legal frameworks, best practices and case studies) were suggested by the IGBC in their response to the IBC’s 2015 draft report on the human genome and human rights. Such activities could meet developing countries’ needs for something on which to base national cloning legislation, identified by all three IBC Working Groups (2008–2009, 2010–2011 and 2014–2015), by alternative means to a binding international convention, the latest recommendations of the IBC on this (and the IGBC’s endorsement of them) notwithstanding. Continuing to develop the Bioethics Programme’s deliberative format, away from short, formal discussions within committees towards more in-depth information exchange between a broader range of stakeholders, bottom-up pledges of action and development of best practice through feasibility studies, may not result in a decision to begin negotiating a treaty (or even a softer declaration), but could lead to a set of resources and commitments that might prove equally effective in promoting ethical behaviour on the part of states and other actors. An added benefit would be that this type of less legalistic, more flexible deliberative output could be more easily adapted and developed to take account of future scientific advances ( Pauwelyn et al., 2014 : 742–743). Even if UNESCO were to decide to follow the IBC’s 2015 recommendation to pursue the elaboration a further international legal instrument on human cloning, adopting these measures could result in a qualitatively stronger instrument than the Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights , for example, as there would be less interest-based bargaining and more buy-in from stakeholders.

When intergovernmental organizations are unable to agree on a form of binding international law such as a convention, they sometimes settle for a declaration, which is less demanding of states. This occurred at the UN in 2005, when the General Assembly could not resolve its members’ differences on what the content and reach of a convention on human cloning should be. Declarations have been the preferred option for UNESCO’s Bioethics Programme in the past, as the drafting period is usually shorter than for a convention and the final product is more likely to inspire consensus, partly because it will be seen to be more flexible and less onerous than a binding piece of legislation ( Langlois, 2013 : 65–66). But this was not a viable path for UNESCO when it came to the regulation of human cloning, because an international declaration—the United Nations Declaration on Human Cloning of 2005—already existed. The Bioethics Programme thus broke with previous practice and began to investigate the possibility of a convention on cloning in 2008. There was tension between IBC and IGBC members over whether a convention would be desirable, with the former (the independent experts) supporting a ban on human reproductive cloning and the latter (representing states) concerned that negotiations would simply revisit the disagreements of the UN General Assembly debates of a few years before. Ultimately, with consensus within and between the two committees proving elusive, the idea of a cloning convention dropped from their agendas in 2012.

The idea was taken up again in 2014, as part of the IBC’s work on the human genome. We can only speculate as to why the IGBC of 2015 was keener on a ban on human reproductive cloning than the IGBC of 2008–2011. The United States was no longer a member, but Germany and Brazil still were ( UNESCO, 2016c ). It could be that, since the first human therapeutic (or research) cloning via somatic cell nuclear transfer took place in 2013 ( Tachibana et al., 2013 ), human reproductive cloning has moved from the realms of science fiction to real possibility in the eyes of policy-makers. Or the changes to the deliberative format at IBC and IGBC meetings introduced in 2014, such as pre-session concept notes and longer discussions, may have engendered greater consensus between the two committees. Yet, despite this consensus, there has been no move on the part of UNESCO to start to develop a treaty. In past standard-setting endeavours, an IBC Working Group has done the initial drafting, but the IBC Work Programme of 2016–2017 makes no mention of human cloning ( UNESCO, 2016d ).

For those states that have yet to formulate national regulations or policies on human cloning, the continued lack of clear guidance at international level may be particularly unhelpful. Thus better global governance in this area is needed. In its 2015 report on the human genome and human rights, the IBC fell somewhere between old and new forms of global governance. There was a strong call for an international binding instrument on human reproductive cloning, to be produced by states and governments, but there were also recommended actions and principles for a broad range of stakeholders, including national governments, scientists, the media, educators and corporations. The science and politics of human cloning have moved on since 2011, when states’ positions were seemingly intractable. Were the Bioethics Programme to mirror successful moves in other fora, such as the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Human Rights Council, towards knowledge sharing, scenario-based exercises and action pledges involving a wide range of stakeholders, a robust global governance framework for human cloning—whether a legally binding instrument or something more flexible—might be achievable.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Additional information

How to cite this article : Langlois A (2017) The global governance of human cloning: the case of UNESCO. Palgrave Communications . 3:17019 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.19. Footnote 3 Footnote 4

See, for example, Macpherson CC (2007) Global bioethics: Did the universal declaration on bioethics and human rights miss the boat? Journal of Medical Ethics ; 33 (10): 588–590; Snead CO (2009) Bioethics and self-governance: The lessons of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy ; 34 (3): 204–222; Kirby M (2010) Health care and global justice. Singapore Academic of Law Journal ; 22 (special ed. 2): 785–800; Langlois A (2013) Negotiating Bioethics: The Governance of UNESCO’s Bioethics Programme . Routledge: Abingdon; Cameron NM de S (2014) Humans, rights, and twenty-first century technologies: The making of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Journal of Legal Medicine ; 35 (2): 235–272.