Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland

Respiratory viruses continue to circulate in Maryland, so masking remains strongly recommended when you visit Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. To protect your loved one, please do not visit if you are sick or have a COVID-19 positive test result. Get more resources on masking and COVID-19 precautions .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Pancreatic Cancer: Experts Answer 10 Commonly Asked Questions

Featured Expert:

Jin He, M.D., Ph.D.

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer death in the United States. While great strides are being made in the search and treatment of pancreatic cancer, there are still many questions about the complex disease. Jin He, M.D., Ph.D. , surgical oncologist, provided responses to frequently asked questions about pancreatic cancer:

Can pancreatic cancer be prevented?

A: Unfortunately, most pancreatic cancer cannot be prevented, but you can reduce your risk by maintaining a healthy weight, stopping smoking and limiting your alcohol intake. Other risk factors include chronic pancreatitis and family history. Occasionally, precancerous lesions can be identified and, if removed early, can prevent pancreatic cancer from developing.

What are the symptoms of pancreatic cancer?

A: There are no specific symptoms for early-stage pancreatic cancer, but if you notice unintentional weight loss, jaundice (yellowing of the skin) and stomach pain, we recommend that you see your primary care physician.

What tests are available to detect pancreatic cancer?

A: There are currently no simple tests for pancreatic cancer. Most cases are found when symptoms develop or an imaging study, such as a CT or MRI scan , is done for another reason. There is active research at Johns Hopkins that is aimed at developing a test for pancreatic cancer in the blood, urine and stool.

Why is pancreatic cancer usually found in the later stages?

A: Pancreatic cancer usually does not cause symptoms, so approximately 50 percent of pancreatic cancers will not be identified until they have already metastasized (spread to other parts of the body).

Is there a direct correlation between breast cancer and pancreatic cancer?

A: There is a relationship between BRCA mutations (breast and ovarian cancer) and pancreatic cancer. A BRCA mutation approximately doubles the lifetime risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Around 5 percent of people with pancreatic cancer have a BRCA mutation. However, breast cancer is very common, so not all patients with breast cancer are thought to have an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

Is pancreatic cancer a genetic disease?

A: Pancreatic cancer can be genetic, but the vast majority of pancreatic cancer is sporadic. Many genes play a role in the growth of pancreatic cancer. The four major driver genes include KRAS, P53, P16 and SMAD4.

If you have a strong family history of pancreatic cancer, you should contact a genetic counseling and screening program. Familial pancreatic cancer is defined as having two or more first-degree relatives with pancreatic cancer. Johns Hopkins has a familial pancreatic cancer registry for surveillance of such patients.

Can pancreatitis be a precursor for pancreatic cancer?

A: Yes, it can be. However, most cases of pancreatitis are unrelated to pancreatic cancer.

What are the chances of a pancreatic cyst becoming cancerous?

A: Pancreatic cysts are very common, and the majority are not cancerous, but some may be, and others may be precancerous. There are several different types of pancreatic cysts ranging from benign to malignant. The key is to determine the malignant risk of your specific cyst.

Is it possible to have full recovery from pancreatic cancer?

A: Yes, it is possible to have a full recovery from pancreatic cancer.

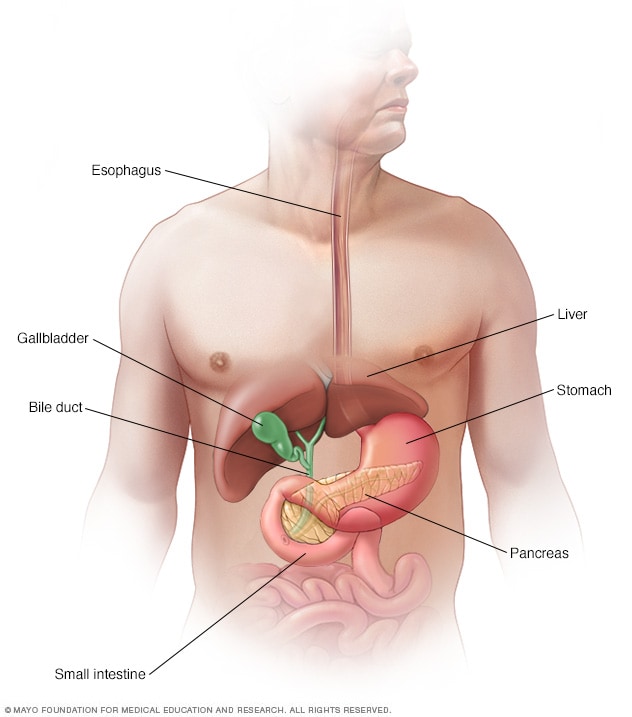

Can you live without a pancreas?

A: Yes, you can live without a pancreas, but you will be diabetic, which means you will have to take insulin regularly. You will also need to take enzyme pills to help with the digestion of food.

Pancreatic Cancer Prevention | Lana's Story

Lana Brandt had a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. After experiencing several bouts of pancreatitis, she learned that she carried a genetic mutation that increased her risk of pancreatic cancer. As a means of pancreatic cancer prevention, experts at Johns Hopkins removed her pancreas and spleen using a minimally invasive technique. They then performed an autoislet cell transplant to help her body continue to produce insulin after surgery.

Find a Doctor

Specializing In:

- Laparoscopic Pancreas Surgery

- Neuroendocrine Tumors

- Robotic Pancreas Surgery

- Whipple procedure

- Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Pancreatic Surgery

- Pancreatic Cancer

Find a Treatment Center

- Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery

- Skip Viragh Center for Pancreas Cancer

Find Additional Treatment Centers at:

- Howard County Medical Center

- Sibley Memorial Hospital

- Suburban Hospital

Request an Appointment

Pancreatic Cancer Surgery

Chemotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic Cancer Vaccine: What to Know

Related Topics

- Pancreatic Cancer Treatment

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Advances in the...

Advances in the management of pancreatic cancer

- Related content

- Peer review

- Marco Del Chiaro , professor, division chief , clinical director 1 2 ,

- Toshitaka Sugawara , assistant clinical professor 1 3 ,

- Sana D Karam , professor 2 4 ,

- Wells A Messersmith , professor , division head, , associate director 2 5

- 1 Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

- 2 University of Colorado Cancer Center, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

- 3 Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan

- 4 Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

- 5 Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

- Corresponding Author: M Del Chiaro marco.delchiaro{at}cuanschutz.edu

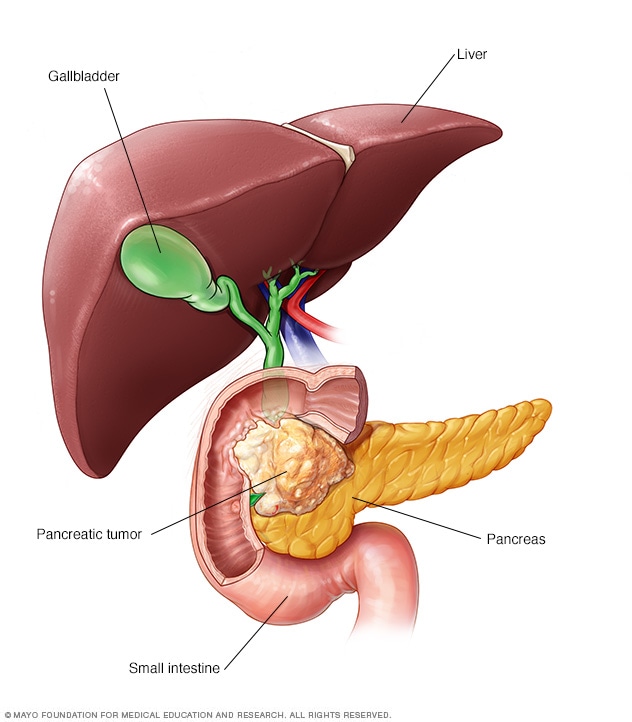

Pancreatic cancer remains among the malignancies with the worst outcomes. Survival has been improving, but at a slower rate than other cancers. Multimodal treatment, including chemotherapy, surgical resection, and radiotherapy, has been under investigation for many years. Because of the anatomical characteristics of the pancreas, more emphasis on treatment selection has been placed on local extension into major vessels. Recently, the development of more effective treatment regimens has opened up new treatment strategies, but urgent research questions have also become apparent. This review outlines the current management of pancreatic cancer, and the recent advances in its treatment. The review discusses future treatment pathways aimed at integrating novel findings of translational and clinical research.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer has been considered a deadly disease with a very small probability of long term survival. 1 Despite slow progress, long term survival rates have greatly improved, especially for resected patients. From 1975 to 2011, the five year survival for resected pancreatic cancer improved from 1.5% to 17.4%. 2 However, more recent data show that five year survival for all pancreatic cancers between 2012-18 reached only 11.5% in the United States. 3

As a systemic disease, the changes in the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer have been affected most by the improvements in systemic treatments. 4 5 Consequently, the anatomical factors influencing the resectability of pancreatic cancer, which are defined in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines, 6 have diminished in importance owing to better local and systemic control with higher response rates.

This review summarizes and contextualizes recent studies on the management of pancreatic cancer, and discusses potential treatments that are on the horizon. A detailed discussion of the preclinical or translational studies of diagnosis tools, drugs, and procedures is outside the scope of this review.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched Pubmed, the Cochrane database, and the Central Register of Controlled Trials (clinicaltrials.gov) between January 2000 and December 2022 for English language literature. We used the following keywords and keywords combinations: “pancreatic cancer”, “molecular characteristics”, “biology”, “resectability”, “metastatic”, “treatment”, “surgery”, “chemotherapy”, “radiation therapy”, “immunotherapy”, “prevention”, “precursor”, and “risk factor”. We also included the NCCN clinical practice guidelines, 6 the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines, 7 and the clinical practice guidelines from the Japan Pancreas Society. 8 We included studies based on the level of evidence; randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and large retrospective cohort studies were prioritized. Meta-analyses included retrospective and prospective studies unless otherwise specified. We prioritized the most recent studies and excluded narrative reviews, case series, and case reports. We included additional landmark studies published before January 2000, as well as after December 2022.

Epidemiology

Pancreatic cancer is reported to account for 495 773 new cases and 466 003 deaths worldwide as of 2020, with the incidence and mortality rates stable or slightly increased in many countries. 9 In the US, the estimated incidence of pancreatic cancer is increasing, with more than 50 000 new cases in 2020. Mortality rates have also increased moderately in men, to 12.7 per 100 000 men in 2020; but have remained stable in women, ranging from 9.3 to 9.6 per 100 000 women. Accordingly, pancreatic cancer is the third most common cause of cancer related death in 2023, and is predicted to become the second leading cause of cancer mortality by 2040. 3 10

Clinical presentation/features

Symptoms of pancreatic cancer are mostly non-specific, and generally manifest after the tumor has grown and metastasized. In a multicenter prospective study of 391 patients who were referred for suspicion of pancreatic cancer (119 had pancreatic cancer), the most common initial symptoms were decreased appetite (28%), indigestion (27%), and change in bowel habits (27%). 11 The initial symptoms were similar between the pancreatic cancer group and the non-cancer group, though several subsequent symptoms were associated with pancreatic cancer: jaundice (49% v 12%), fatigue (51% v 26%), decreased appetite (48% v 26%), weight loss (55% v 22%), and change in bowel habits (41% v 16%).

Risk factors

Box 1 summarizes the risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Research is continuing into subtypes and modifiers of familial syndromes.

Factors that increase the risk of pancreatic cancer

Family history.

Up to 10% of all pancreatic cancers are estimated to be familial (meaning that at least two first degree relatives have pancreatic cancer)

Patients who have two first degree relatives with pancreatic cancer have a standardized incidence ratio of 6.4 (lifetime risk 8-12%) 12

Patients who have three first degree relatives with pancreatic cancer have a standardized incidence ratio of 32.0 (lifetime risk 40%) 12

Approximately 20% of these families have a germline mutation that is already reported and known

Germline mutation and hereditary syndrome

LKB1/STK11: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; relative risk 132 13

CDKN2A/p16: familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome; relative risk 13-22 14

PRSS1/CPA1/CTRC/SPINK1: hereditary pancreatitis; relative risk 53-87 15

BRCA1 and BRCA2: hereditary breast ovarian cancer syndrome; relative risk 2 and 10, respectively 16

MLH1/MSH2/MSH6/PMS2: Lynch syndrome; relative risk up to 8.6 17

PALB2/ATM: relative risk unknown

Lifestyle factors

Smoking: current smoker relative risk 1.8; former smoker relative risk 1.2 18

Obesity: five unit increment in body mass index relative risk 1.10 19

Diabetes mellitus * : relative risk 1.94 20

Chronic pancreatitis: relative risk 16.16 21

*Diabetes mellitus is also a symptom of pancreatic cancer; new onset diabetes in older people could be an early sign of pancreatic cancer and can lead to early diagnosis. 22 The association between diabetes and pancreatic cancer is currently undergoing further research. 23

Precancerous lesion

Molecular research has proposed two evolutionary models of pancreatic cancer: the classic “stepwise” model, with gradual accumulation of driver gene mutations, and the novel “punctuated” model, 24 in which driver gene mutation occurs simultaneously by chromosomal rearrangements. The stepwise model is characterized by tumor evolution from a precancerous lesion (low grade or high grade dysplasia) to invasive cancer, and is believed to be the main evolutionary pattern. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are well known precancerous lesions. By contrast to PanIN, which is a microscopic neoplastic lesion, IPMNs can be detected and followed by imaging studies. Consequently, extensive studies have been conducted to evaluate the association between imaging findings and pathological findings of IPMNs. Branch duct IPMNs have been reported to have a low malignant nature (1.0% patient years), 25 but harbor a risk of concomitant pancreatic cancer (0.8%). 26 Main duct IPMNs have been reported to be a high risk factor for pancreatic cancer (odds ratio 5.66). 27

Screening and early detection

Because early stage (ie, stage I, T1N0M0) disease or precancerous lesions are more likely to be curable, the goal of screening or surveillance for pancreatic cancer is to detect lesions of 2 cm or smaller, or patients with high grade dysplasia. 28 Several studies have estimated an interval of several years between a high grade dysplasia lesion (high grade PanIN and IPMN) and invasive cancer, which can give opportunities for early detection and intervention: 2.3-11 years for high grade PanIN, 29 30 and more than three years for high grade IPMN. 31 The International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) consortium has published consensus guidelines about screening for high risk patients who have high risk germline mutations or relatives with pancreatic cancer, or both. 28 A recent prospective cohort study (CAPS5) from the CAPS group including 1461 high risk patients showed positive results of surveillance 25 ; seven of nine patients (77.8%) who developed pancreatic cancer had stage I cancer. However, only three of the eight patients (37.5%) who had IPMNs with worrisome features had high grade dysplasia (five had low grade dysplasia). A multicenter retrospective study (n=2552) of the CAPS consortium showed that 13 of the 28 patients (46.4%) who developed high grade dysplasia or cancer developed the new lesion during the scheduled examination interval. 32 Regarding IPMNs in the general population, a recent retrospective study showed that only 177 of 1439 patients with resected IPMN (12.3%) had high grade dysplasia, and 497 (34.5%) had a diagnosis of invasive cancer. 33 These results suggest that a novel strategy distinct from current guidelines 34 35 is needed for IPMN lesions, and new diagnostic tests are needed to detect tiny tumors.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) 36 recommends avoiding pancreatic cancer screening in asymptomatic adults with average risk, considering the relatively low prevalence (estimated 64 050 new cases in 2023). 36 However, the USPSTF does not discuss screening in patients with risk factors of age and lifestyle, and neither do the consensus guidelines of the CAPS consortium. A risk assessment model including all known risk factors ( box 1 ) could help to identify good candidates for pancreatic cancer screening.

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) is a cell surface tetrasaccharide often elevated in pancreatic cancer, as well as in other cancers and some benign diseases. Historically, CA19-9 has not been used for early detection, owing to its insufficient sensitivity for early stage pancreatic cancer. 37 We also know that 5-10% of the population does not synthesize CA19-9, owing to a deficiency of a fucosyltransferase enzyme. However, a recent large retrospective cohort study showed that CA19-9 levels increase from two years before diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, with a sensitivity of 50% and specificity of 99% within 0-6 months before diagnosis in early stage disease. In addition, in cases with CA19-9 levels below the cut-off value, the combination of LRG1 and TIMP1 could complement CA19-9, leading to the identification of cases missed by CA19-9 alone. 38 Novel tests (ie, cytology 39 and DNA alterations 40 ) using pancreatic juice and cystic fluid have been reported to play a promising role in identifying high grade dysplasia and invasive cancer with high specificity. However, the sensitivity of these tests is low (˂50%). Extensive studies have investigated the role of liquid biopsy in pancreatic cancer: circulating tumor cells, 41 circulating tumor DNA, 42 43 microRNA, 44 exosomes, 45 and methylation signatures of cell free DNA. 46 Although these new biomarkers show promise, many problems remain unsolved with regard to standardization of testing techniques and cut-off values ( table 1 ). However, advances in this field could increase survival drastically.

Summary of novel techniques for diagnosis and early detection of pancreatic cancer

- View inline

Diagnosis and evaluation

The performance of diagnosis tools is summarized in box 2 .

Imaging study and biomarker for diagnosis of pancreatic cancer

CT (computed tomography) is the standard modality; accuracy 89% (95% confidence interval 85 to 93) 47

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) has a similar performance to CT; accuracy 90% (95% confidence interval 86 to 94) 47

PET (positron emission tomography) has a worse performance; accuracy 84% (95% confidence interval 79 to 89) 47

Endoscopic ultrasound has a similar performance to CT; accuracy 89% (95% confidence interval 87 to 92) 47

Endoscopic ultrasound can identify masses that are indeterminate by CT; accuracy 75% (95% confidence interval 67 to 82) 48

CA19-9 is the most widely used and validated biomarker; area under curve 0.83-0.91 49

Imaging study for evaluation

CT (computed tomography) is the standard tool to evaluate the extent of the primary tumor and determine its anatomical resectability. Two meta-analyses showed similar performance of CT (sensitivity 70%, specificity 95%) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) (sensitivity 65%, specificity 95%) in the diagnosis of vascular involvement. 50 51 A meta-analysis showed that endoscopic ultrasound performed similarly to CT in evaluating vascular invasion. 52 A multimodal approach (ie, CT plus MRI plus endoscopic ultrasound) provides a better assessment of resectability. Several studies have attempted to evaluate the response to chemotherapy with imaging studies to determine the course of treatment (ie, proceeding to surgery or continuing chemotherapy). However, the currently used response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) are not sufficient to reassess local response after chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer, especially regarding the involvement of vessels. Distinguishing scar areas with fibrosis that occur with treatment from cancer cell death from viable tumor associated desmoplasia is challenging; both are common in pancreatic cancer. A meta-analysis including six studies with 217 patients showed the difficulty of using CT scans to predict margin negative resection after preoperative treatment; the sensitivity was 81% and specificity was as low as 42%. 53 MRI 54 55 and fluorodeoxyglucose PET (positron emission tomography)/CT or PET/MRI 56 have been reported to be associated with the pathological response to preoperative treatment, though the ability to evaluate the vessel involvement and resectability is unclear. However, it should also be noted that even in the setting of histological response assessment, moderate inter-rater reliability differences have been reported between pathologists. 57

Biomarker for evaluation

CA19-9 has been used to assess response to treatment and predict prognosis. A meta-analysis showed that CA19-9 was associated with the effect of preoperative treatment, and suggested that either normalization of CA19-9 or a decrease of more than 50% from the baseline level are positive predictors of survival. 58 A recent retrospective study analyzing the combination of CT and CA19-9 showed a good predictive performance of survival after chemoradiotherapy. 59 However, the optimal evaluation of response to treatment remains unclear. The ability of liquid biopsy ( table 1 ) to detect minimal residual disease following all planned treatment could identify a new subset of patients who require further treatment, and would lead to a true precision medicine approach, as has been achieved with other cancer types. 60

Cancer cell intrinsic and tumor microenvironment factor

Transcriptional studies have proposed several classifications of pancreatic cancer. A recent bioinformatic study 61 from The Cancer Genome Atlas research network supported the two subgroup model 62 : the basal-like subtype, which has low levels of GATA6 expression, and the classic subtype. In a prospective translational trial, the basal-like subtype was reported to be associated with a poor response to chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX (combined leucovorin calcium (folinic acid), fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) for patients with advanced cancer. 63 However, a more recent study using single cell analysis suggested that pancreatic cancer consists of a mixture of tumor cells with both molecular subtypes, and the composition is plastic and unstable. 64

In addition to the cancer cells themselves, the tumor microenvironment has been identified as being an essential factor associated with tumor progressions and tumor immunity. Pancreatic cancer is notorious for poor tumor cellularity and an abundant, fibrotic extracellular matrix. Although the dense extracellular matrix has been known to impair drug delivery and immune cell migration, it appears to have an essential role in maintaining the tumor microenvironment and supporting the progression of tumor cells. 65 Therefore, the efficacy of controlling the extracellular matrix by targeting its components (ie, collagen, cancer associated fibroblasts, and hyaluronan) and cytokines (ie, transforming growth factor β and sonic hedgehog) has been evaluated.

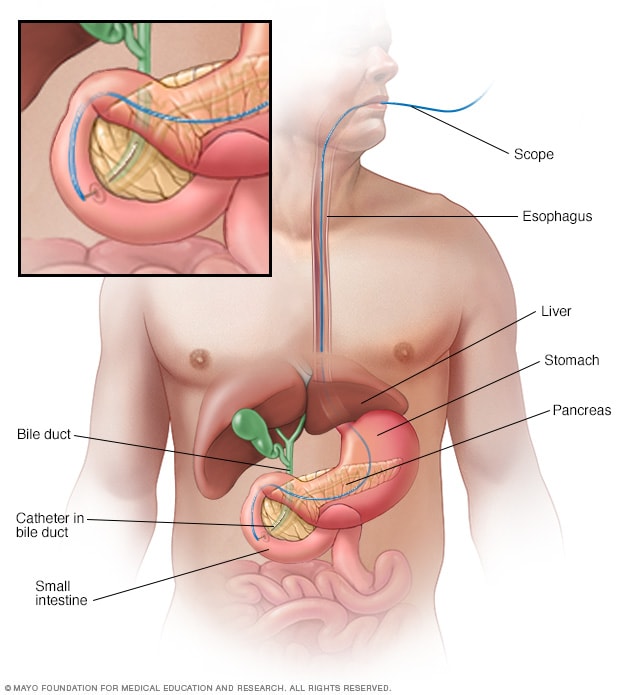

Figure 1 outlines the current management for pancreatic cancer based on the anatomic resectability of the tumor, with the first consensus statement defined in 2009, 66 before the advent of more effective systemic treatments. In primary resectable disease, upfront surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy has been considered the standard of care. By contrast, for borderline resectable and locally advanced diseases, preoperative treatment is generally proposed, because of the high likelihood of micrometastasis and the low likelihood of margin negative resection in these tumors. 67 However, the improvement of medical treatment is challenging this concept; neoadjuvant treatment for resectable diseases is under investigation. At present, the recommendation is that the decision for treatment should be made at a multidisciplinary conference at a high volume center.

Current management for pancreatic cancer. CA19-9=carbohydrate antigen 19-9

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Systemic treatment

The standard drug treatment for systemic treatment is still cytotoxic chemotherapy, and the efficacy of targeted treatment or immunotherapy remains unproven. Table 2 summarizes the clinical trials of medical treatment.

Summary of key studies of medical treatment of pancreatic cancer

Systemic treatment for metastatic disease

Gemcitabine became the standard chemotherapy drug for pancreatic cancer more than 20 years ago. In 1997, gemcitabine showed clinical benefit and marginally improved overall survival compared with fluorouracil (median survival 5.65 v 4.41 months) in a small randomized controlled trial that included 63 patients in each arm. 68 Consequently, several trials were performed investigating combinations with gemcitabine. 69 70 71 However, most studies did not show a significant improvement in overall survival; the combinations tested included fluorouracil, 72 irinotecan, 73 oxaliplatin, 74 75 cisplatin, 76 77 and capecitabine. 78 79 80 Unfortunately, the addition of targeted treatment to gemcitabine based chemotherapy also did not show a survival benefit, with any of tipifarnib, 81 cetuximab, 82 bevacizumab, 83 84 axitinib, 85 and vandetanib. 86 In 2011, a landmark randomized phase 2/3 trial (PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11) defined a new standard chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer. 71 This multicenter trial enrolled 171 patients in each arm and showed a significant improvement in survival, with a median overall survival of 11.1 months in the FOLFIRINOX group, compared with 6.8 months in the gemcitabine group (hazard ratio 0.57; 95% confidence interval 0.45 to 0.73). FOLFIRINOX also had a higher response rate (31.6%) than gemcitabine (9.4%). Subsequently, the MPACT trial, a large randomized phase 3 study, showed another cytotoxic combination option (gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel) for metastatic pancreatic cancer. 87 This study included 861 patients, and showed that gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel improved survival compared with gemcitabine alone (median survival 8.5 v 6.7 months; hazard ratio 0.72; 95% confidence interval 0.62 to 0.83). FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel have formed the cytotoxic “backbones” for multiple clinical trials.

Nanoliposomal irinotecan is a drug encapsulating irinotecan sucrosofate salt payload in tiny pegylated liposomal particles, which theoretically can enhance the exposure of irinotecan to tumor cells. A recent randomized phase 3 trial (NAPOLI-3) enrolled 770 patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer and compared NALIRIFOX (combined liposomal irinotecan, fluorouracil, folinic acid, and oxaliplatin) (n=383) to gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (n=387) as the first line treatment. 88 Preliminary results showed an improved overall survival (median 11.1 v 9.2 months; hazard ratio 0.84; 95% confidence interval 0.71 to 0.99), which was the primary endpoint, and an improved progression free survival (7.4 v 5.6 months; 0.70; 0.59 to 0.84). For Asian populations, S-1 (an oral fluoropyrimidine derivative) is another treatment option, after it showed non-inferiority to gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer in a randomized phase 3 study (GEST). 89

Second line systemic treatment for advanced disease

Second line regimens after gemcitabine based chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer have been studied in several trials. The CONKO-003 randomized phase 3 trial showed that the addition of oxaliplatin to folinic acid and fluorouracil (5FU/LV) significantly improved overall survival (median 5.9 v 3.3 months, hazard ratio 0.66; 95% confidence interval 0.48 to 0.91). 90 By contrast, another randomized phase 3 trial (PANCREOX) found a deleterious effect on survival of oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) over infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin (hazard ratio 1.78; 95% confidence interval 1.08 to 2.93) in the second line setting. 91

A large randomized phase 3 trial (NAPOLI-1) investigated the efficacy of nanoliposomal irinotecan to 5FU/LV for metastatic disease after gemcitabine based treatment. 92 The results showed that nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5FU/LV incrementally improved survival compared with 5FU/LV (6.1 v 4.2 months, hazard ratio 0.67; 95% confidence interval 0.49 to 0.92). Patients who received nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy, however, had similar survival to those who received 5FU/LV (4.9 v 4.2 months, 0.99; 0.77 to 1.28). Further studies on second line regimens after FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel are warranted.

Maintenance systemic treatment for advanced disease

A poly adenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor was investigated as the maintenance treatment in patients who had germline loss-of-function mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, and platinum sensitive advanced disease. A randomized double blind phase 3 trial (POLO) showed no survival benefit of olaparib (n=62) compared with placebo (n=92) (median overall survival 19.0 v 19.2 months; hazard ratio 0.83; 95% confidence interval 0.56 to 1.22), but did show an improvement in progression free survival, which resulted in US Food and Drug Administration approval. 93 94 Another PARP inhibitor, niraparib, combined with an anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) drug, showed a median overall survival of 17.3 months (95% confidence interval 12.8 to 21.9 months) in a phase 1b/2 trial. 95 Maintenance treatment for non-BRCA mutated patients with metastatic diseases following FOLFIRINOX was evaluated in the PANOPTIMOX-PRODIGE 35 phase 2 trial. 96 This study randomly assigned 273 patients to six month FOLFIRINOX (n=91), four month FOLFIRINOX followed by leucovorin/5-FU maintenance (n=92), or a sequential treatment alternating gemcitabine and FOLFIRI.3 every two months (n=90). The results showed a comparable six month progression free survival rate and median progression free survival in the maintenance arm eliminating oxaliplatin (44%, 5.7 months), and the worst survival in the gemcitabine/FOLFIRI approach (34%, 4.5 months) compared with the six month FOLFIRINOX arm (47%, 6.3 months).

Adjuvant systemic treatment

Adjuvant systemic treatment is recommended for all eligible resected patients. The first large randomized phase 3 trial that showed the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy was the ESPAC-1 trial, which assigned resected patients (n=289) to 5-FU/LV versus control. 4 97 Adjuvant chemotherapy prolonged the median overall survival by 4.6 months (hazard ratio 0.71; 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.92). 4 The CONKO-001 randomized phase 3 trial showed that adjuvant gemcitabine (n=179) improved overall survival compared with observation (n=172) (median 22.8 v 20.2 months; hazard ratio 0.76; 95% confidence interval 0.61 to 0.95). 98 When 5FU/LV and gemcitabine were compared head-to-head, no difference in overall survival was found, but gemcitabine had less toxicity in the ESPAC-3 randomized phase 3 trial. 99 Subsequently, multiple trials tried to find a new effective combination treatment with gemcitabine. A randomized phase 3 trial combining erlotinib with gemcitabine was negative, 100 but the addition of capecitabine had a survival benefit over gemcitabine alone (28.0 v 25.5 months; 0.82; 0.68 to 0.98) in the ESPAC-4 phase 3 trial. 101 However, this combination treatment was short lived; FOLFIRINOX drastically changed the survival of patients and became the new standard regimen for adjuvant treatment. The PRODIGE 24/CCTG PA6 phase 3 trial randomly assigned 493 resected patients to receive adjuvant modified (dose reduced) FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX) or gemcitabine for 24 weeks. The mFOLFIRINOX group (n=247) showed a significantly improved median overall survival (53.5 v 35.5 months; 0.68; 0.54 to 0.85). 5 102 By contrast, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel failed to show a survival benefit over gemcitabine alone in a randomized phase 3 trial (APACT). 103 It did not meet the primary endpoint of disease free survival by central review, 103 although overall survival improved marginally in the gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel group (40.5 v 36.2 months; 0.82; 0.680 to 0.996). In Asia, S-1 is the standard regimen, based on the results of a randomized phase 3 trial. 104 The role of adjuvant treatment after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgical resection is still debatable. A recent large retrospective study showed a potential benefit in survival for patients able to receive adjuvant chemotherapy after neoadjuvant and surgery. 105

Neoadjuvant systemic treatment

One of the underpinnings of neoadjuvant treatment is that 36% of patients with pancreatic cancer are unable to receive adjuvant chemotherapy after resection, 106 and surgical resection alone does not achieve long term survival for most patients. The rationale for neoadjuvant treatment is to increase the dose intensity and tolerance of planned systemic treatment before patients are weakened by surgery, and to avoid delayed treatment of micrometastatic disease, which is the main cause of mortality. 107 Two prospective single arm phase 2 studies showed the safety of neoadjuvant gemcitabine plus a platinum based drug. 108 109

The only published phase 3 trial of neoadjuvant systemic treatment (PREOPANC-1) randomly assigned 246 patients with resectable (54.1%) or borderline resectable disease (45.9%) to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (n=119) or upfront surgery (n=127). 110 111 The neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy arm received three cycles of neoadjuvant gemcitabine with 36 Gy radiotherapy in 15 fractions and four cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine, whereas the upfront surgery arm received six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine. Long term results showed a consistent survival benefit of neoadjuvant treatment regardless of the resectability of the primary tumors, for borderline resectable diseases (hazard ratio 0.67; 95% confidence interval 0.45 to 0.99) and resectable diseases (0.79; 0.54 to 1.16). However, the chemotherapy regimen (gemcitabine alone) was outdated. The recent ESPAC-5 phase 2 trial 112 randomly assigned 90 patients with borderline resectable diseases to neoadjuvant treatment (n=56), which included multiagent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and single agent chemoradiotherapy, or upfront surgery (n=33). It showed a better one year overall survival in the neoadjuvant treatment groups compared with the upfront surgery group (76% v 39%; hazard ratio 0.29; 95% confidence interval 0.14 to 0.60), although it did not provide evidence of the optimal regimen owing to the small sample size.

Regarding resectable diseases, one concern of neoadjuvant treatment is the possibility of disease progression during neoadjuvant treatment, which could cause patients to miss the opportunity for surgical resection. Indeed, the role of neoadjuvant treatment for resectable disease is still under investigation. A randomized phase 2 trial (PACT-15) showed that neoadjuvant chemotherapy with the PEFG regimen (cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine) improved overall survival compared with adjuvant gemcitabine and adjuvant PEFG regimen for resectable disease. 113 The Prep-02/JSAP-05 phase 2/3 trial randomly assigned patients with resectable (about 80%) or borderline resectable diseases to one month neoadjuvant gemcitabine plus S-1 (n=182), or upfront surgery (n=180). Both arms received six month S-1 as the adjuvant treatment. 114 The results showed improved overall survival in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy arm (36.7 v 26.6 months; hazard ratio 0.72; 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.94). Conversely, studies of FOLFIRINOX have not shown positive results. 115 116 The SWOG S1505 phase 2 study showed equivalent efficacy of neoadjuvant mFOLFIRINOX versus nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine for three months for resectable disease. 115 The median overall survival in both arms (23.2 and 23.6 months) did not show improvement compared with previous trials of adjuvant treatment.

A recent phase 2 trial (NORPACT-1) randomly assigned 140 patients with resectable diseases to the neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX arm (n=77) or the upfront surgery arm (n=63), and found no survival benefit of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX. However, the results have several problems. While not significant, the median survival was 13.4 months shorter (25.1 v 38.5 months) in the neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX arm, despite the higher rates of node negative (N0) and margin negative (R0) resection in that arm. Given the high resection rate (n=63, 82%) despite the low completion rate of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=40, 52%), and the high rate of adjuvant chemotherapy other than FOLFIRINOX (75%) in the neoadjuvant group, it seems that the neoadjuvant group did not receive sufficient FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy. In addition, whether two months is sufficient for neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX is unclear. Three ongoing large randomized phase 3 trials might provide some insight into the optimal sequence and the number of cycles of FOLFIRINOX; two are recruiting patients (ALLIANCE-A021806 and PREOPANC-3), and one recently opened ( NCT05529940 ). The first two trials plan to enrol more than 300 patients with resectable disease to assess the overall survival of perioperative FOLFIRINOX (eight cycles of neoadjuvant and four cycles of adjuvant) compared with adjuvant FOLFIRINOX (12 cycles). The NCT05529940 trial plans to enrol more than 600 patients and evaluate the two year survival of perioperative FOLFIRINOX (six cycles of neoadjuvant and six cycles of adjuvant) compared with adjuvant FOLFIRINOX (12 cycles).

Systemic treatment for locally advanced disease

After the positive results of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for metastatic disease, several studies have investigated its efficacy in locally advanced diseases. A systematic review that analyzed 315 patients with locally advanced diseases from 11 studies between 1994 and 2015 showed that FOLFIRINOX was associated with a longer median overall survival of 24.2 months (95% confidence interval 21.7 to 26.8 months). 117 The proportion of patients who underwent surgical resection after FOLFIRINOX ranged from 0-43%. A phase 2 study (LAPACT) investigated gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for 106 patients 118 ; the median overall survival was 18.8 months (90% confidence interval 15.0 to 24.0 months). In total, 62 patients (58%) completed induction gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel, and 17 patients (16%) underwent surgical resection. Another randomized phase 2 study (NEOLAP-AIO-PAK-0113) showed high surgical conversion rates of gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (23/64, 35.9%) and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel followed by FOLFIRINOX (29/66, 43.9%). 119 No survival differences were observed between the two arms (hazard ratio 0.86; 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 1.36). These results suggest a new potential treatment strategy for surgical conversion of locally advanced disease, which could achieve longer survival in selected patients.

Surgical treatment

Pancreatectomy, especially pancreaticoduodenectomy, has been considered a high risk surgery. The centralization of pancreatectomy has played an essential role in the improvement of perioperative outcomes. The 90 day mortality is reported to be under 5-10% in experienced high volume centers. 120 121 A recent meta-analysis including 46 retrospective studies (2015-2021) showed a significantly lower postoperative morbidity rate in high volume centers compared with low volume centers (47.1% v 56.2%; odds ratio 0.75; 95% confidence interval 0.65 to 0.88). 121

Surgery for locally advanced and borderline disease

Some experts have pushed for more aggressive operations for patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced diseases with the advent of more effective systemic drugs. Resection after neoadjuvant treatment was reported to have similar short term outcomes compared with upfront resection in a meta-analysis 122 including randomized controlled trials and a subgroup report of a randomized phase 3 trial. 123 However, data on arterial resection and reconstruction are more controversial, and depend on the resected artery and the technical approach; the mortality rates were reported as 5.7% for resection of the superior mesenteric artery, 124 and 1.7% for resection of the celiac axis. 125 More recently, arterial divestment has been proposed as an alternative to arterial resection in selected patients. A retrospective study of a high volume center reported a mortality rate of 7.0% for arterial resections and 2.3% for arterial divestment from 2015 to 2019, although the breakdown of resected arteries was not shown by periods. 126 To be clear, these aggressive procedures should be performed only when long term survival is expected. A previous meta-analysis including 13 studies (2005-2015) with 355 locally advanced tumors showed no significant association between the resection rate after chemotherapy and overall survival. 117 However, large, retrospective studies recently showed that conversion surgery for locally advanced diseases after FOLFIRINOX was associated with improved survival in a selected subgroup. 127 128 Further studies are expected.

Surgery for patients with metastatic disease

Macroscopic distant metastasis is a contraindication to surgical resection in general. However, several studies have reported a potential role of resection in highly selected patients with limited metastatic diseases. A meta-analysis including three retrospective studies (2016-2019) showed a longer overall survival (23-56 months v 11-16 months) in patients with synchronous liver metastasis who underwent resection after chemotherapy (n=44) compared with those who did not (n=166). 129 In another review, lung metastasectomy was associated with a longer survival with a median overall survival after resection ranging from 18.6 to 38.3 months. 130 A large retrospective study suggested that only patients who achieved a complete pathological response of metastasis could derive a survival benefit from resection. 131 Further studies are expected to provide data on patient selection criteria and metastatic sites. A single arm phase 2 study ( NCT04617457 ) and a randomized phase 3 trial ( NCT03398291 ) are recruiting patients with oligometastasis in liver from pancreatic cancer to evaluate the efficacy of resection after chemotherapy.

Minimally invasive surgery

Minimally invasive surgery for pancreatic cancer had until recently been lagging behind that for other cancers. Results of a recent randomized trial 132 (n=656) and a meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials 133 (n=224) showed that laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy was associated with a shorter hospital stay, but a similar postoperative morbidity rate. Box 3 summarizes the studies comparing robotic pancreatoduodenectomy with open or laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy. Notably, all studies on pancreatoduodenectomy to date have included patients with diseases other than pancreatic cancer. Another meta-analysis including 12 randomized or matched studies (n=4346) showed a similar morbidity rate, but a higher margin negative resection rate (odds ratio 1.46) and shorter time to adjuvant treatment, in the laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy group. 139 Most recently, an international randomized trial (DIPLOMA) 140 including 117 patients with resectable pancreatic cancer in the minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy group and 114 patients in the open distal pancreatectomy group showed the non-inferiority of the oncological safety of minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy: a higher margin negative resection rate (73% v 69%) and comparable lymph node yield and intraperitoneal recurrence.

Comparison between robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy and open pancreatoduodenectomy or laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy

Robotic pancreatoduodenectomy ( v open pancreatoduodenectomy ) 134 135 136 | robotic pancreatoduodenectomy ( v laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy ) 135 137 138.

R0 resection: Comparable 135 136 or higher 134 | Comparable 135

Lymph nodes harvested: Comparable 135 136 or more 134 | Comparable 135 or more 137 138

Operating time: Longer 134 135 136 | Comparable 135 137 138

Estimated blood loss: Less 134 135 136 | Comparable 138 or less 135 137

Conversion rate: Not applicable | Lower 137 138

Overall mortality rate: Comparable 134 or lower 136 | Comparable 138

Overall morbidity rate: Comparable 134 135 or lower 136 | Comparable 135 137 138

Surgical site infection: Less 134 135 | Comparable 135 138

Pancreatic fistula: Comparable 134 135 or less 136 | Comparable 135 137 138

Hemorrhage: Comparable 135 | Comparable 135

Delayed gastric emptying: Comparable 134 136 or less 135 | Comparable 135 137 138

Length of stay: Comparable 134 135 or longer 136 | Comparable 135 137 or shorter 138

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is used as a part of local treatment for pancreatic cancer, generally combined with chemotherapy. Since the gold standard for this disease remains surgical resection, 67 the role of radiotherapy has been logically examined in both the adjuvant setting and in locally advanced inoperable patients. The neoadjuvant application of radiotherapy has also been investigated in several studies. In this setting, however, high level evidence comparing the role of radiotherapy in a head-to-head design to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is lacking. The true efficacy of radiotherapy on long term survival remains unclear, especially when combined with modern multiagent systemic treatments and surgical resection. Another concern in many radiotherapy studies is the heterogeneity of the treatment technique and dose used. For example, the techniques have evolved from conventional treatments to intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), more ablative approaches with adaptive planning platforms. Box 4 summarizes the characteristics of radiotherapy by types and doses. Table 3 summarizes the clinical studies of radiotherapy.

Characteristics of radiotherapy for pancreatic cancer by types and doses

3 dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3d-crt).

Using multiple beams shaped to conform to a tumor that is identified its size, shape, and location by 3D imaging (ie, CT, MRI)

Generally used dose:* 45.0-56.0 Gy in 1.75-2.20 Gy fractions

Image guided radiation therapy (IGRT)

An adjunctive technique to adjust the tumor location difference by using 3D imaging (ie, CT, MRI) performed immediately before each radiation treatment

Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)

Possible to adjust the irradiation intensity within a target volume

Possible to deliver a concentrated dose to a tumor and better spare the normal tissue

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT)

Accurately irradiate a tumor with high dose radiation in three dimensions from multiple directions

High local control rate, comparable toxicity 141

Generally used dose:* 30.0-40.0 Gy in 6.00-8.00 Gy fractions

*Based on the ASTRO clinical practice guideline. 142

Summary of key studies of radiotherapy for pancreatic cancer

Adjuvant radiotherapy

In theory, the purpose of adjuvant radiotherapy is to reduce the risk of local recurrence. NCCN guidelines recommend considering adjuvant chemoradiation treatment for patients with positive surgical margins. 67 However, prospective studies that support adjuvant radiotherapy are lacking, regardless of the surgical margin status. The aforementioned large randomized phase 3 trial (ESPAC-1) included 289 resected patients: 51 (17.6%) had positive resection margins. The results showed worse survival in the chemoradiotherapy arm (n=145) than in the non-radiotherapy arm (n=144) (median overall survival 15.9 v 17.9 months; hazard ratio 1.28; 95% confidence interval 0.99 to 1.66). 4 This study has discouraged further studies of adjuvant radiotherapy in Europe. However, the study had two major drawbacks. Firstly, the chemotherapy regimen was different in the chemotherapy arm (fluorouracil/leucovorin) and the chemoradiotherapy arm (fluorouracil). Secondly, the total dose of radiotherapy (20 Gy) did not reach 45 Gy, which represents the treatment dose of conventional, fractionated external beam radiotherapy. 67 Two randomized phase 2 studies investigated adjuvant gemcitabine plus radiotherapy for patients with negative resection margins. The first study administered 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions of radiotherapy, and found a lower local alone recurrence rate (11% v 24%), but did not show a difference in overall survival or disease free survival between the two arms (45 patients each). 143 The other small study (n=38) used a modern SBRT technique (25 Gy in five fractions), but showed no difference in any of the survival endpoints (recurrence free survival, locoregional recurrence free survival, or overall survival), even in the node positive subgroup. 144 An older systematic review included five randomized controlled trials (1985-2005) of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy consisting of fluorouracil based chemotherapy plus conventional radiotherapy, and showed no survival benefit of chemoradiation (pooled hazard ratio 1.09; 95% confidence interval 0.89 to 1.32). 145 The subgroup analysis in this study showed a possible efficacy of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with positive resection margins.

The RTOG0848 trial is a randomized phase 2/3 study that enrolled 322 resected patients. The ongoing phase 3 of this trial assesses the survival benefit of added radiotherapy (50.4 Gy) after six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine based chemotherapy. However, because the standard of care regimen of adjuvant chemotherapy has changed to FOLFIRINOX, the results of this study might have a limited impact on clinical practice. Ultimately, the role of adjuvant radiotherapy is still ambiguous.

Neoadjuvant radiotherapy

One of the primary goals of neoadjuvant radiotherapy is to reduce the rate of positive margin resection, which is a risk factor for local recurrence. Two single arm phase 2 studies showed the tolerability and feasibility of concurrent radiotherapy combined with fluorouracil plus cisplatin 146 (n=41) and gemcitabine (n=41). 147 However, the evidence on the efficacy of neoadjuvant radiotherapy is inconsistent. A meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials (n=189) that investigated chemoradiotherapy (fluorouracil based chemotherapy with a radiotherapy dose of 45-50.4 Gy) did not show any difference in overall survival between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (hazard ratio 0.93; 95% confidence interval 0.69 to 1.25). 148 The aforementioned PREOPANC-1 phase 3 trial, which showed a survival benefit of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for borderline resectable disease, did not evaluate effects with and without radiation. 110 Regarding neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with FOLFIRINOX, a phase 2 trial (n=48) showed that neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX plus chemoradiotherapy in borderline resectable disease showed a high rate of margin negative resection, and prolonged median progression free survival and even median overall survival. 149 By contrast, a randomized phase 2 trial (ALLIANCE-A021501) showed worse survival in the patients with borderline resectable disease who were allocated to the neoadjuvant mFOLFIRINOX plus radiotherapy (SBRT or hypofractionated image guided radiotherapy) arm (n=56) compared with those who allocated to the neoadjuvant mFOLFIRINOX alone arm (n=70) (median overall survival 17.1 v 29.8 months; median event free survival 10.2 v 15.0 months). 150 However, the number of patients was modest, and the dropout rates were high in both the chemotherapy arm (71.4%) and the chemoradiation arm (82.1%). A meta-analysis comprising 15 studies (512 patients) of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX with or without radiotherapy for resectable and borderline resectable disease showed a better rate of margin negative resection in the chemoradiotherapy group (97.6% v 88.0%). 151 No differences were observed in resection rate, overall survival, or pathological outcomes. The PANDAS-PRODIGE 44 study, a randomized phase 2 study, assigned 130 patients with borderline resectable diseases to mFOLFIRINOX or mFOLFIRINOX plus conformal external radiation (50.4 Gy). This ongoing study aims to evaluate the histological negative margin resection rate as the primary endpoint.

Radiation for locally advanced disease

For locally advanced pancreatic cancer, radiation is used as the primary modality for local control and, on rare occasions, to facilitate margin negative resection in select patients who achieve good responses to treatment. 67 Trials for locally advanced diseases have reported various levels of efficacy. A randomized trial assigned 37 patients to receive chemoradiotherapy (gemcitabine, 50.4 Gy) and 34 patients to receive gemcitabine alone. The trial showed improved overall survival in the chemoradiotherapy group (11.1 v 9.2 months). 152 Progression free survival was not different, but the sample size was notably small. The LAP07 trial was a large randomized phase 3 trial that aimed to investigate the survival benefit of adding radiotherapy to chemotherapy (54 Gy plus capecitabine) compared with chemotherapy (gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus erlotinib) after four months of gemcitabine based induction chemotherapy. 153 The results showed no differences in overall (median 15.2 v 16.5 months; hazard ratio 1.03; 95% confidence interval 0.79 to 1.34) or progression free survival (9.9 v 8.4 months; 0.78; 0.61 to 1.01) between the chemoradiotherapy group (n=133) and the chemotherapy group (n=136). An older randomized phase 3 trial (2000-01 FFCD/SFRO) also compared gemcitabine chemotherapy (n=60) to chemoradiotherapy with fluorouracil and cisplatin (60 Gy) (n=59), 154 and showed worse overall survival (median 8.6 v 13.0 months) and progression free survival in the chemoradiotherapy group. 154 The study, however, suffered from major inconsistencies in the proportion of patients who received at least 75% of the planned dose of induction chemotherapy, being only 42.4% in the chemoradiotherapy group compared with 73.3% in the chemotherapy group.

Given that conventional fractionated radiotherapy techniques combined with gemcitabine based chemotherapy have failed to show a significant survival advantage, the focus of research has moved to SBRT and FOLFIRINOX. A meta-analysis of 1147 patients from 21 studies including randomized controlled trials (2002-2014) compared conventional external beam techniques to SBRT. 141 The estimated two year overall survival was higher in the SBRT group (26.9% v 13.7%), with less acute grade 3/4 toxicity (5.6% v 37.7%) and similar late grade 3/4 toxicity (9.0% v 10.1%). A phase 2 trial (LAPC-1) enrolled 50 patients to receive eight cycles of FOLFIRINOX followed by SBRT (40 Gy in five fractions). 155 In total, 39 patients underwent SBRT (78.0%) and seven (14.0%) patients underwent surgical resection; all had negative margins and pathological N0 stage. The overall survival in the resected patients was longer than in the unresected patients (median 24 v 15 months; three year survival rate 43% v 6.5%). A systematic review including 2446 patients from 28 phase 2/3 studies also showed a similar resection rate of 12.1% (95% confidence interval 10.0% to 14.5%). Therefore, this newest chemoradiotherapy approach could give the best chance of curative intent surgery, and achieve long term survival in a highly selected subgroup of patients.

Four phase 2/3 trials are ongoing. The CONKO-007 trial is a large randomized phase 3 trial enrolling 525 patients to evaluate chemoradiotherapy (50.4 Gy with gemcitabine) after induction chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX (n=402) or gemcitabine (n=93) for three months; the primary endpoint was margin negative resection rate. The first results came out in 2022, and showed a higher rate of margin negative resection (resection and circumferential resection margin) (9.0% v 19.6%) in the chemoradiation arm (n=168, 61 underwent surgery) compared with the chemotherapy arm, which was continuing FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine (n=167, 60 underwent surgery). 156 However, the total surgical resection margin negativity rate and survival did not reach statistical significance. The publication is pending. The other three trials are phase 2 trials and are still recruiting patients (SCALOP-2, 157 MASTERPLAN, 158 and GABRINOX-ART 159 ). These studies could provide more data about gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel and SBRT for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. However, we are unable to draw a conclusion without well designed phase 3 trials using the latest technology and chemotherapy regimen.

Supportive care and palliative care

Weight loss is seen in more than half of patients at diagnosis of pancreatic cancer 11 ; as a result, the rates of malnutrition 160 161 (33.7-70.6%) and sarcopenia 162 (up to 74%) are high. Malnutrition and sarcopenia have been reported to be associated with poor outcomes of surgical resection and chemotherapy. 163 Given that the majority of patients suffer from metastatic diseases, palliative care, including pain management and nutrition support, is essential to their quality of life, and even prognosis. Table 4 highlights major studies on these topics.

Summary of studies on supportive/palliative care for pancreatic cancer

Emerging diagnostic tools and treatments

Diagnostic tools.

Fibrosis, both chemoradiotherapy induced and cancer associated, has been reported to be associated with overall survival. An MRI probe targeting chemoradiotherapy induced collagen (type I collagen) can detect this change in fibrosis. 170 Radiolabeled fibroblast activation protein inhibitors (FAPI) can target the expression of fibroblast activation protein in cancer associated fibroblasts, which is abundant in pancreatic cancer. 171 A meta-analysis showed superior performance of FAPI PET over FDG PET/CT/MRI for the determination of tumor, node, metastases (TNM) classification and peritoneal carcinomatosis. 172 A phase 2 trial is recruiting patients to evaluate the efficacy of FAPI PET/CT in patients with locally advanced disease ( NCT05518903 ).

Radiomics using machine learning or deep learning (artificial intelligence) is a new field of research, driven by advances in computer systems. Theoretically, a computer can learn and identify features and differences that a human cannot. A systematic review showed that radiomics models of the primary tumors had good performance in predicting patient prognosis. 173 Further studies with larger sample sizes for training and validating models with risk factors, images, and biomarkers will yield more conclusive results in this regard.

In the era of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, a new question has emerged of how to manage patients who have tumor progression during neoadjuvant treatment. A phase 2 trial ( NCT03322995 ) is recruiting patients (n=125) with resectable and borderline resectable disease to evaluate the efficacy of adaptive modification of neoadjuvant treatment (four months). Based on the results of restaging after four cycles of FOLFIRINOX, a decision will be made to either continue the same regimen, or switch to a gemcitabine based regimen and chemoradiotherapy. For locally advanced pancreatic cancer, the NEOPAN phase 3 trial successfully enrolled 171 patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer to compare the progression free survival of FOLFIRINOX (12 cycles) with gemcitabine (four cycles), with preliminary results expected soon. Few data exist on the comparison of FOLFIRINOX with gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for both localized and advanced cancer. A randomized phase 2 study (PASS-01) is recruiting patients (planned n=150) with metastatic disease to investigate the difference in progression free survival between the two regimens. Moreover, genomic factors and putative biomarkers will be explored using whole genome sequencing and RNA sequencing, and patient derived organoids.

Immunotherapy has been largely ineffective in pancreatic cancer, potentially owing to both tumor cell intrinsic and tumor microenvironment factors. Recent trials have taken a combined approach. CISPD3, a randomized phase 3 trial (n=110), showed an improved objective response rate (50.0% v 23.9%; P=0.010) by adding sintilimab (a monoclonal antibody against programmed cell death protein 1) to FOLFIRINOX for metastatic patients, 174 albeit without superior overall survival and progression free survival. The same group is conducting a phase 3 trial to evaluate the same regimen in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced diseases ( NCT03983057 ). Given the results of basic research in pancreatic cancer showing that the extracellular matrix plays an essential role in the tumor microenvironment and progression, several new agents have been introduced. A phase 2 trial ( NCT03336216 ) combining an immune checkpoint inhibitor with chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine based regimen) and cabiralizumab (a colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor that suppresses the activities of tumor associated macrophages) has been conducted. However, a 2020 press release 175 176 announced that this study missed the primary endpoint of progression free survival.

Pamrevlumab, a recombinant human monoclonal antibody against connective tissue growth factor, has been investigated in a randomized phase 3 trial (LAPIS) combined with FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (up to six cycles) for locally advanced tumors. The study has completed recruitment (n=284) and is continuing to evaluate the primary endpoint of overall survival. Most recently, a phase 1 trial proposed a notable approach to stimulating cancer immunity in pancreatic cancer, with promising results. 177 The study adopted the messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine technique to make a personalized mRNA vaccine encoding five or more neoantigens, which were bioinformatically predicted from the resected primary tumor. This adjuvant treatment consisted of one dose of atezolizumab (anti-PDL1 (programmed death ligand 1) antibody) and eight doses (one week) of mRNA neoantigen vaccines, followed by 12 cycles of mFOLFIRINOX. In total, 16 of 28 resected patients received personalized vaccines, and eight patients responded to the vaccines, with no recurrence among responders after a median follow-up of 18.0 months. Larger studies will help establish whether this is a breakthrough in immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer.

Treatment strategies targeting specific genomic alterations have been explored in various molecularly defined patient subsets. Given the positive results for metastatic cancer in the POLO trial, 93 olaparib is being studied in a randomized phase 2 trial (APOLLO) to evaluate the additional benefit of one year of treatment on recurrence free survival in patients with a pathogenic BRCA1, BRCA2, or PALB2 mutation, who have received at least three months of multi-agent chemotherapy after curative resection. KRAS is an attractive target owing to its high rate of mutation (90%) in pancreatic cancer. 178 Although KRAS G12C mutations are rare (1.6% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cases), the ability to create covalent G12C inhibitors led to FDA approval in non-small cell lung cancer, and promising initial results in PDAC. Sotorasib, a KRAS G12C inhibitor, showed a median progression free survival of four months, and an objective response rate of 21% in metastatic patients with KRAS G12C mutations who received at least two lines of chemotherapy in a phase 1/2 trial. 179 Another KRAS G12C inhibitor, adagrasib, showed a median progression free survival of 6.6 months, and an objective response rate of 50% (5/10 patients), in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer in a phase 1/2 trial (KRYSTAL). 180

By contrast to the low mutation rate in BRCA1 (1.08%), BRCA2 (1.48%), PALB2 (0.54%), and KRAS G12C (1-2%), other KRAS mutations are quite common, and pan-KRAS inhibitors are under investigation. Two phase 1 studies of pan-RAS inhibitors are recruiting patients ( NCT04678648 and NCT05379985 ). Further studies on other KRAS targeting approaches are expected.

Radiotherapy has been suggested to have synergistic effects on local and even distant tumors when combined with immunotherapy. 181 182 A large randomized phase 3 trial showed that chemoradiotherapy followed by durvalumab (PDL1 inhibitor) had significantly longer overall survival than placebo in locally advanced, non-small cell lung cancer. 183 Recently, a phase 2 trial (CheckPAC) assigned 84 patients with refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer to receive SBRT/nivolumab (n=41) or SBRT/nivolumab/ipilimumab (n=43). 184 The SBRT/nivolumab/ipilimumab arm had a higher disease control rate (37.2% v 17.1%). Further studies with an immunotherapy–SBRT backbone are anticipated in locally advanced and metastatic disease settings.

Figure 2 summarizes all the data discussed above, and gives perspective on the future of the management of pancreatic cancer.

Precision medicine for pancreatic cancer. PanIN=pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasm

Several national and international guidelines for the management of pancreatic cancer have been published. Recommendations of those guidelines are proposed considering the evidence and the healthcare system of each country. We reviewed two major guidelines of the US and Europe, and also included the recent 2022 updated Japanese guideline. 6 7 8 All recommendations of these guidelines are made based on the metastatic status and the anatomical resectability of the primary tumors. Regarding treatments for resectable diseases, the NCCN guidelines list neoadjuvant chemotherapy as an option for high risk patients, and the Japan Pancreas Society guidelines recommend neoadjuvant for all patients. The ESMO guidelines recommend only upfront surgery. The NCCN and ESMO guidelines recommend mFOLFIRINOX as the first option of adjuvant chemotherapy, although S-1 monotherapy is recommended by the Japan Pancreas Society guidelines. Conversion surgery for locally advanced disease is an option in the NCCN and Japan Pancreas Society guidelines. No recommendation is made for conversion surgery for metastatic disease in any of the three sets of guidelines. Radiotherapy is listed as an option for non-metastatic diseases in the NCCN guidelines, while the other guidelines do not recommend it for resectable diseases. The NCCN guidelines recommend genetic testing of inherited mutations for all patients with pancreatic cancer, but no clear recommendations are made in the other sets of guidelines.

Conclusions

In the US and Europe, the incidence of pancreatic cancer has been increasing consistently, and this trend is estimated to continue for several decades. Advances in the combination of cytotoxic drugs have resulted in improvements in survival for all stages of the disease, and are changing treatment algorithms. Further investigation into the role of immuno-oncology agents and radiation could help a subset of patients. In addition, extensive efforts need to focus on risk assessment, screening, and early detection.

Research questions

・In patients treated with upfront systemic treatment, what is the optimal duration of systemic treatment and patient selection for surgical resection?

・How can immuno-oncology and targeted treatment be made effective?

・What is the optimal combination and sequence of radiotherapy, and who are the ideal targets?

・What is the specific population that needs routine screening and what is an effective combination of tests to detect precancerous lesions?

Glossary of abbreviations

NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network

ESMO: European Society for Medical Oncology

PanIN: pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia

IPMN: intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

CAPS: International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening

USPSTF: United States Preventive Services Task Force

CA19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9

RECIST: response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

FOLFIRINOX: combined leucovorin calcium (folinic acid), fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin

NALIRIFOX: combined liposomal irinotecan, fluorouracil, folinic acid, and oxaliplatin

mFOLFIRINOX: modified FOLFIRINOX

PEFG regimen: cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine

IMRT: intensity modulated radiation therapy

SBRT: stereotactic body radiation therapy

3D-CRT: 3 dimensional conformal radiation therapy

IGRT: image guided radiation therapy

FAPI: fibroblast activation protein inhibitors

PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

PDL1: programmed death ligand 1

State of the Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason they are written predominantly by US authors.

Competing interests : We have read and understood the BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: MDC receives grants from Haemonetics, and is the primary investigator of a Boston Scientific sponsored study. TS does not have conflicts of interest to declare. SDK receives investigator initiated clinical trial funding from Genentech and AstraZeneca. She also receives preclinical research support from Roche and Amgen. WAM receives institutional clinical trial funding from Genentech, Beigene, Pfizer, NGM, Gossamer, ALX, Exelixis, EDDC/D3, Mirati, RasCal Therapeutics, and CanBAS. He is also a Data and Safety Monitoring Board member of QED, Amgen, and Zymeworks.

Funding: This study is supported by funding sources: R01 DE028529-01 (SDK), R01 DE028282-01 (SDK), 1R01CA284651-01 (SDK), 1P50CA261605-01 (SDK), and the V Foundation Translational Research Award. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Contributors: Authors MDC and TS are joint first authors. The design, literature search, review, and writing of this manuscript was led by MDC and TS, and supported by SDK and WAM. MDC is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

We thank Hiroyuki Ishida for his drawings in figure 2 , and Michael J Kirsch for his assistance in proofreading this manuscript.

Patient involvement: No patients were involved in the writing of this review.

Provenance and peer review: commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Schwartz LM ,

- Bengtsson A ,

- Andersson R ,

- Siegel RL ,

- Miller KD ,

- Neoptolemos JP ,

- Stocken DD ,

- European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer

- Canadian Cancer Trials Group and the Unicancer-GI–PRODIGE Group

- ↵ National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (Version 2.2022)

- Ducreux M ,

- Caramella C ,

- ESMO Guidelines Committee

- Okusaka T ,

- Nakamura M ,

- Yoshida M ,

- Committee for Revision of Clinical Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer of the Japan Pancreas Society

- Wehner MR ,

- Matrisian LM ,

- Walter FM ,

- Mendonça SC ,

- Petersen GM ,

- Giardiello FM ,

- Brensinger JD ,

- Tersmette AC ,

- Frants RR ,

- van Der Velden PA ,

- Rebours V ,

- Boutron-Ruault MC ,

- Deters CA ,

- Snyder CL ,

- Kastrinos F ,

- Mukherjee B ,

- Bosetti C ,

- Greenwood DC ,

- Kirkegård J ,

- Mortensen FV ,

- Cronin-Fenton D

- Pannala R ,

- Early Detection Initiative Consortium

- Chan-Seng-Yue M ,

- Katona BW ,

- Balduzzi A ,

- Marchegiani G ,

- Pollini T ,

- Goggins M ,

- Overbeek KA ,

- International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) consortium

- Yachida S ,

- Gerstung M ,

- Leshchiner I ,

- PCAWG Evolution & Heterogeneity Working Group ,

- PCAWG Consortium

- Niknafs N ,

- Fischer CG ,

- Goggins MG ,

- International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Consortium

- Sandini M ,

- Mihaljevic AL ,

- Fernández-Del Castillo C ,

- Kamisawa T ,

- European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas

- Davidson KW ,

- US Preventive Services Task Force

- Steinberg WM ,

- Gelfand R ,

- Anderson KK ,

- Fahrmann JF ,

- Schmidt CM ,

- Visser IJ ,

- Levink IJM ,

- Peppelenbosch MP ,

- Fuhler GM ,

- Becker TM ,

- Yildirim HC ,

- Aktepe OH ,

- Pietrasz D ,

- Hadden WJ ,

- Laurence JM ,

- Krishna SG ,

- Ugbarugba E ,

- Leeflang MMG ,

- Treadwell JR ,

- Mitchell MD ,

- Teitelbaum U ,

- Erickson B ,

- Evangelista L ,

- Zucchetta P ,

- Moletta L ,

- Janssen BV ,

- van Roessel S ,

- van Dieren S ,

- International Study Group of Pancreatic Pathologists (ISGPP)

- Lahouel K ,

- DYNAMIC Investigators

- Raphael BJ ,

- Hruban RH ,

- Aguirre AJ ,

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address: [email protected] ,

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network

- Moffitt RA ,

- Marayati R ,

- Fischer SE ,

- Denroche RE ,

- Wilson GW ,

- Callery MP ,

- Fishman EK ,

- Talamonti MS ,

- William Traverso L ,

- ↵ National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (Version 2.2022). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf

- Burris HA 3rd . ,

- Andersen J ,

- Goldstein D ,

- National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group

- Milandri C ,

- Desseigne F ,

- Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer ,

- PRODIGE Intergroup

- Berlin JD ,

- Catalano P ,

- Thomas JP ,

- Kugler JW ,

- Haller DG ,

- Benson AB 3rd .

- Rocha Lima CM ,

- Labianca R ,

- Heinemann V ,

- Quietzsch D ,

- Gieseler F ,

- Colucci G ,

- Di Costanzo F ,

- Gruppo Oncologico Italia Meridionale (GOIM) ,

- Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dei Carcinomi dell’Apparato Digerente (GISCAD) ,

- Gruppo Oncologico Italiano di Ricerca Clinica (GOIRC)

- Herrmann R ,

- Ruhstaller T ,

- Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research ,

- Central European Cooperative Oncology Group

- Bernhard J ,

- Dietrich D ,

- Scheithauer W ,

- Cunningham D ,

- Van Cutsem E ,

- van de Velde H ,

- Karasek P ,

- Cascinu S ,

- Berardi R ,

- Italian Group for the Study of Digestive Tract Cancer (GISCAD)

- Vervenne WL ,

- Bennouna J ,

- Kindler HL ,

- Niedzwiecki D ,

- Richel DJ ,

- Middleton G ,

- Palmer DH ,

- Greenhalf W ,

- Von Hoff DD ,

- Wainberg ZA ,

- Macarulla T ,

- Stieler JM ,

- Wang-Gillam A ,

- NAPOLI-1 Study Group

- Williet N ,

- Le Malicot K ,

- PRODIGE 35 Investigators/Collaborators

- Neuhaus P ,

- Hochhaus A ,

- Liersch T ,

- Tempero MA ,

- O’Reilly EM ,

- APACT Investigators

- Fukutomi A ,

- JASPAC 01 Study Group

- Sugawara T ,

- Rodriguez Franco S ,

- Sherman S ,

- Nassour I ,

- Chabot JA ,

- Heinrich S ,

- Pestalozzi BC ,

- Schäfer M ,

- OʼReilly EM ,

- Perelshteyn A ,

- Jarnagin WR ,

- Versteijne E ,

- Groothuis K ,

- Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group

- van Dam JL ,

- Cicconi S ,

- Balzano G ,

- Sohal DPS ,

- Labori KJ ,

- Bratlie SO ,

- Biörserud C ,

- Beumer BR ,

- Philip PA ,

- Portales F ,

- Kunzmann V ,

- Siveke JT ,

- German Pancreatic Cancer Working Group (AIO-PAK) and NEOLAP investigators

- Cameron JL ,

- Coleman J ,

- Ratnayake B ,

- Pendharkar SA ,

- van Dongen JC ,

- Wismans LV ,

- Suurmeijer JA ,

- Bachellier P ,

- Petrucciani N ,

- Belloni E ,

- Klaiber U ,

- Gemenetzis G ,

- De Simoni O ,

- Tonello M ,

- Sakaguchi T ,

- Valente R ,

- Del Chiaro M

- Minimally Invasive Treatment Group in the Pancreatic Disease Branch of China’s International Exchange and Promotion Association for Medicine and Healthcare (MITG-P-CPAM)

- Vissers FL ,

- van Hilst J ,

- International Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Resection Trialists Group

- Da Dong X ,

- Felsenreich DM ,

- Kamarajah SK ,

- Bundred J ,

- Cucchetti A ,

- Bocchino A ,

- Abu Hilal M ,

- Tchelebi LT ,

- Lehrer EJ ,

- Trifiletti DM ,

- Godfrey D ,

- Goodman KA ,

- Van Laethem J-L ,

- Büchler MW ,

- Dervenis C ,

- Pancreatic Cancer Meta-analysis Group

- Scoazec JY ,

- Small W Jr . ,

- Freedman GM ,

- Murphy JE ,

- Janssen QP ,

- Kivits IG ,

- Loehrer PJ Sr . ,

- Cardenes H ,

- van Laethem J-L ,

- LAP07 Trial Group

- Chauffert B ,

- Bonnetain F ,

- Nuyttens JJ ,

- Eskens FALM ,

- Fietkau R ,

- Ghadimi M ,

- Grützmann R ,

- Strauss VY ,

- Virdee PS ,

- Samalin E ,

- Álvaro Sanz E ,

- Garrido Siles M ,

- Rey Fernández L ,

- Villatoro Roldán R ,

- Rueda Domínguez A ,

- Griffin OM ,

- O’Connor D ,

- Ozola Zalite I ,

- Francisco Gonzalez M ,

- Heckler M ,

- Hüttner FJ ,

- Hamauchi S ,

- Abernethy AP ,

- Currow DC ,

- Solheim TS ,

- Laird BJA ,

- Balstad TR ,

- Koulouris AI ,

- Alexandre L ,

- Daeninck PJ ,

- Erstad DJ ,

- Sojoodi M ,

- Taylor MS ,

- Spielman B ,

- Veldhuijzen van Zanten SEM ,

- Pieterman KJ ,

- Wijnhoven BPL ,

- ↵ Columbus G. Nivolumab/cabiralizumab combo misses PFS endpoint in pancreatic cancer. 2020. https://www.onclive.com/view/nivolumabcabiralizumab-combo-misses-pfs-endpoint-in-pancreatic-cancer

- Bendell JC ,

- Soares KC ,

- Strickler JH ,

- George TJ ,

- Bekaii-Saab TS ,

- Sharabi AB ,

- DeWeese TL ,

- Twyman-Saint Victor C ,

- Antonia SJ ,

- Villegas A ,

- PACIFIC Investigators

- Johansen JS ,

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer

- Bile Duct Cancer

- Bladder Cancer

- Brain Cancer

- Breast Cancer

- Cervical Cancer

- Childhood Cancer

- Colorectal Cancer

- Endometrial Cancer

- Esophageal Cancer

- Head and Neck Cancer

- Kidney Cancer

- Liver Cancer