How to write a whole research paper in a week

Writing up a full research article in a single week? Maybe you think that’s impossible. Yet I have done it repeatedly, and so have students in my courses. This is an exceptionally joyful (even if demanding) experience: being so productive just feels great! You are not wasting any time, and a paper produced in one go is typically coherent and nice to read. Even if you are a slow writer, you can write a whole paper in a single week — if you follow my strategy. Read below about what you need to prepare and how to approach this project.

I wrote my first scientific research article in 7 days. It started as a desperate effort to stop my procrastination and “just do it”. But I was surprised what a positive experience it was: focused and efficient, I was making daily progress, feeling motivated and content. Finally, the fruits of my hard work were gaining shape — and they did it so quickly!

I realized it was highly effective to write up a paper like this: writing for the whole day, every day until the first draft was finished. My writing project was firmly present in my mind — I didn’t lose time catching up with what I have written in the last session. Since I was not doing anything else, my wandering mind settled in very fast, and I was getting into a routine. The daily progress was clearly visible and motivated me to continue. And the result was a coherent paper that was easy to revise.

Meanwhile, this paper-a-week approach is my favorite. That’s how I write my papers, and that’s what I teach to students. In on-site courses young scientists draft a whole paper in 5 days, writing one major section per day. At the beginning of the week, many participants have doubts. But at the end of the week, they are all excited to see how much they managed to write in just a single week.

If you would also like to try out this approach, then read on about the necessary preparations, the optimal setting, and a productive writing strategy.

If you would like to get support during the preparation, drafting and revising of your research article, check out my online course Write Up Your Paper .

Prepare well

- First, think about your audience and pick a suitable journal . This is an important step because the audience and journal determine the content & style of your paper. As a reference, pick two recent papers on a similar topic published in your target journal.

- Create a storyline for your paper. What is the main message you want to convey, and how are you going to present your results?

- Put together all the results that you need to present your story convincingly: collect the necessary data, finish analyses, and create figures and tables.

- Select and read the relevant background literature as well as studies you want to compare your work with. As you read, note down any point that comes to your mind as something to be mentioned in the Introduction or Discussion section.

- Draft a preliminary Abstract : it will help you keep the direction and not get distracted by secondary ideas as you write the individual sections.

Depending on how complete your results already are, you might need 2-4 weeks to finish all these preparations. To help you keep an overview, I created a checklist with detailed steps that you need to take before you attempt to write up your paper in a week. Subscribe to our Newsletter and get your copy of the checklist.

Reserve a whole week for writing

Now, writing a paper in a single week is a serious business. You can’t do it if you don’t focus solely on the writing and create good writing conditions. Therefore, I recommend the following settings:

- Find a place where you can write without distractions. I have written my first paper over the Easter holidays when there was nobody in the office. You might choose to write at home or in a library. Though if possible, the best is to go for a retreat: removing yourself from your everyday settings immensely helps focus on the writing.

- Cancel (all) social obligations for the week. While it’s crucial to relax in the evening, you want to avoid disturbances associated with social events. Anything that makes your thoughts drift away from your work because it requires planning, exchanging of messages with others, or simply because it’s too exciting is better left for some other week. On the other hand, a quiet meeting with a good friend over a glass of wine or beer might be just the perfect way to unwind and rest after a productive, yet exhausting day of writing.

- Get support from the partner, family or friends — if possible. It’s best when you don’t need to run errands, cook and clean during this week. If you live alone, you can probably easily arrange yourself for undisturbed work. If you live with other people, ask them for consideration and support.

What I described above are the *ideal* conditions for undisturbed writing. But don’t give up if you can’t create such conditions for yourself. Work with what is possible — maybe it will take you 7-8 instead of 5-6 days but that’s still a great result, right?

Do you need to revise & polish your manuscript or thesis but don’t know where to begin?

Get your Revision Checklist

Click here for an efficient step-by-step revision of your scientific texts.

Maybe you think that you can never ever draft a research article in a single week. Because you write so slowly, producing only few paragraphs per day. Well — I agree that if you don’t optimize your writing strategy, it would be hard to impossible to write up a whole paper in a week.

- Separate the processes of writing and revising. That’s the most important principle. Resist the urge to revise as you write the first draft. Moreover, don’t interrupt your writing to look up missing information. Work with placeholders instead. This allows you to get into the state of flow and proceed much faster than you can imagine.

- Start your writing day with 10 minutes of freewriting . Write without stopping about anything that comes to your mind. This helps you to warm up for writing, clear your head of any unrelated thoughts, and get into the mood of writing without editing.

- Take regular power breaks. I recommend to follow the Pomodoro technique : write for 25 minutes and then take a 5-minute break. After 3-4 such sessions take a longer break of 0.5-1 hour. During the breaks get up, walk a bit, stretch, look around, and breathe deeply. These breaks help you sustain high focus and productivity throughout the whole day.

- Eat and sleep well. What you are doing is similar to a professional athlete. So take care of your brain and body, and they will serve you well.

- Reward yourself. Every day celebrate the progress you have made. You have full right to be proud of you!

Write the individual sections in a reasonable order

If you have written a research paper before, you have probably realized that starting with the Introduction and finishing with the Discussion is not the ideal order in which to tackle the individual sections. Instead, I recommend the following procedure:

- Start with the Methods section. This is the easiest section to write, so it’s great as a warm-up, to get into writing without the need to think (and procrastinate ;)) too much. Look at your figures and tables: what methods did you use to create them? Then describe your methods, one after another.

- Results section: Writing the Methods section refreshes your memory about the research you have done. So writing the Results section next should not be too hard: Take one display object (figure or table) after another, and describe the results they contain. While you do so, you will come across points that need to be discussed in the Discussion section. Note them down so you don’t forget them.

- Introduction : When your results are fresh in your mind, you are in a great position to write the Introduction — because the Introduction should contain selected information that gives the reader context for your research project and allows them to understand your results and their implications.

- Discussion : When you have taken notes while writing the Results section, the Discussion section should be quite easy to draft. Don’t worry too early about the order in which you want to discuss the individual points. Write one paragraph for each point , and then see how you can logically arrange them.

- Abstract and title : On the last day, revise the preliminary Abstract or write a new one. You could also take a break of a few days before tackling the Abstract, to gain clarity and distance. Generate multiple titles (I recommend 6-10), so that you and your co-authors can choose the most appropriate one.

Just do it!

Once you have written the whole draft, let it sit for a week or two, and then revise it. Follow my tips for efficient revising and get your revision checklist that will guide you step-by-step through the whole process.

Now I am curious about your experience: Have you ever written up an academic article quickly? How did you do it? Please, share with us your tips & strategies!

Do you need to revise & polish your manuscript or thesis but don’t know where to begin? Is your text a mess and you don't know how to improve it?

Click here for an efficient step-by-step revision of your scientific texts. You will be guided through each step with concrete tips for execution.

7 thoughts on “ How to write a whole research paper in a week ”

Thank for your guide and suggestion. It gives to me very precious ways how to write a article. Now I am writing a article related to Buddhist studies. Thank you so much.

You are welcome!

excellent! it helped me a lot! wish you all best

Hi Parham, I’m happy to hear that!

I have never written any paper before. As I am from very old school.

But my writing skill is actually very good. Your help is definitely going to help me as this has inspired me alot. Will let you know, once done. I really like the outline that you have given. Basically you have made it so easy for me .

Hope fully will be in touch with you soon.

Thanks and ki d Regards, Shehla

Dear Shehla, that sounds great! I’m looking forward to hearing about your paper!

Comments are closed.

Diese Webseite verwendet Cookies, um Ihnen ein besseres Nutzererlebnis zu bieten. Wenn Sie die Seite weiternutzen, stimmen Sie der Cookie-Nutzung zu.

How to Write a Research Paper in a Day: Step-by-Step Guide

Julie Peterson

As all other students, you put a lot of effort into studying and writing homework assignments. You do your best to complete every single project on time. Unfortunately, that’s not always possible.

Research papers are long-term assignments. Your professors advise you to start early, and you try to do that. However, you have to think about tests and other assignments. Plus, you can’t stay in the library forever when you should also work on your social life.

Sooner or later, every student ends up in the same situation: the deadline is too close and the research paper is nowhere near finished. There are two usual reasons that lead to that scenario:

1) You forgot all about this project. You were too occupied with studying and classes. You didn’t set a reminder on your calendar, and your teacher just reminded you that the deadline is tomorrow .

2) You kept procrastinating. The topic seemed simple enough, so you thought you had enough time. The day before the deadline, you’re facing the harsh reality: a research paper is more complex than it seems.

1. First Thing’s First: Calm Down!

What’s the first thing you do when you realize you have very little time to complete a whole research paper? Panic! It’s the usual reaction. You start saying to yourself:

- “There’s no way I can do this!”

- “It’s just impossible.”

- “Oh my God, what am I gonna do?”

That’s the wrong approach to have. Panic will block you from achieving your full potential. The first thing you need to do is relax . You forgot about that paper. Now, you’re left with a tight deadline. That’s okay. You still have time and you can still do something about it.

Close your eyes. Take a deep breath. Then, repeat to yourself:

- “I can do this. I will research and write whole day. I’ll get it done by tomorrow.”

That positive self-talk will prepare your mind for the challenge that follows. Eat something nice, make yourself some coffee and get to work. If necessary, take a 20-minute power nap before you proceed with the following steps.

2. Use the Pomodoro Technique

When you have to stay focused on a challenging task, it’s important to have a system. The Pomodoro Technique is a pretty effective method that helps you do more work in less time. It’s based on a simple principle:

- You work for 25 minutes straight, with no distractions.

- After the work session, you take a 5-minute break.

It sounds pretty simple, but it works. Twenty five minutes doesn’t seem like a long time. Your mind can stay focused on the task at hand without much effort. After the short break, you’ll be able to get back to work.

If you start writing the paper without such system, the task will seem overwhelming. With the Pomodoro Technique, you’re giving yourself small steps towards the ultimate goal.

You can use a browser extension like Strict Workflow to keep track of your working and resting session. It’s great because it blocks your access to distracting websites during the working session. When you give yourself a break of 5 minutes, you can check what’s new on Twitter.

3. Start With Brainstorming

Before you get to work, you’ll need to get an idea. How do you want this paper to look like? Go through a brief brainstorming stage, so you’ll form an outline to guide you to the process of research and writing.

- Your teacher gave you a prompt for the research paper. Focus on it. What ideas do you get?

- Make a list of a few possible topics. The brainstorming stage doesn’t need much thinking. You just write whatever comes to your mind.

- Now, do a preliminary research on those topics. It shouldn’t take much time. Give 5 minutes to each idea you have. What topic gives you the greatest foundation for research? That’s what you should focus on.

- First, form your thesis statement. It’s something you will prove throughout the research paper. The preliminary research provided you with enough resources. Keep in mind that professors don’t like broad thesis statement. If, for example, the prompt was related to World War 2, you’ll have to narrow it down. You can opt for a specific event during the war, or even explore the Italian uniforms. Whatever it is, you need to make it very specific.

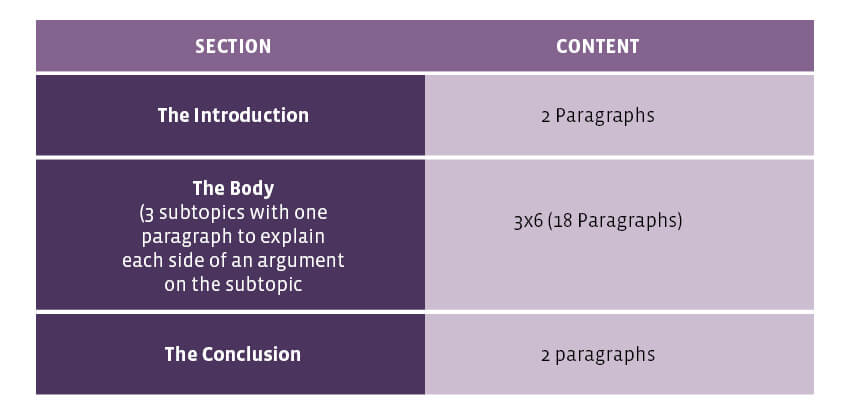

- Think of at least 3-4 subtopics. When you focus on the main topic, what questions do you have? You’ll want to answer those questions through the subtopics. That will be the body of your research paper.

- Finally, the outline should include a conclusion, which will sum up the claims and connect the loose ends.

4. Now, Onto the Research!

Here is an important piece of advice: don’t research as you write. When you’re working on a serious research paper, you need to explore many resources that will help you get ideas and form opinions. This should be a separate stage. Since you have only one day to write this paper, you can give yourself 2 hours for the research. Here are few tips to consider:

- Use Google Scholar instead of the usual Google search engine. It gives you access to high-quality scientific and academic sources. Only authoritative sources will make the paper look serious and well-researched.

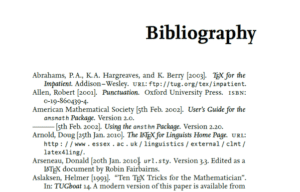

- Keep track of all online sources you collect. You will need to reference them. Otherwise, you’ll be guilty of plagiarism. You can create a private Pinterest board, where you’ll collect all materials you plan to use. As for the referencing, you can use a free citation generator , which will save you a lot of time.

- Take notes! You can’t expect to remember everything you read and all ideas you get during this stage. If necessary, update the outline and make it more detailed.

5. Write It!

Finally, you’ve come down to the writing part. You might want to take a break before this stage. Have another cup of coffee and an energizing meal.

- Again: relax! You have an outline with good ideas. You have enough resources to work with. At this stage, you should just bring everything together, and that won’t take more than 4 hours.

- You don’t have to start with the introduction. Many students find it easier to write the thesis and develop the arguments first. Then, it’s easier to explain what the paper is about in the introductory part.

- Don’t think much about the style and grammar at first. This is your first draft, which will go through changes later on. Focus on expressing your ideas in a logical way.

- Support your arguments with quotes from the resources you have. They will add strength to the claims.

- Use simple, clear language. Don’t try to make a good impression by writing endless sentences and using words you just found in the dictionary. You don’t need complex style to show you know what you’re writing about.

- Don’t leave the references last. Cite the sources as you go!

- Keep up with the Pomodoro method while you write. If you feel exhausted and you need a longer break, take a power nap and you’ll continue later.

6. Don’t Forget the Editing

You’re almost done, but it’s not time to celebrate just yet. When you finish writing the research paper, it’s important to take a break. You must be hungry, so get something to eat. Try not to think about the paper for at least one hour. When you go back to it, the mistakes will be more obvious.

SEE: Top 6 Editing Tools for College Students

- Get rid of sentences and paragraphs that are not directly related to the thesis statement and subtopics.

- Add more information when you notice gaps in the logical flow.

- Pay attention to the citations. You have to format them in accordance with the required referencing style.

- Proofread! Once you’re done fixing the major aspects of the paper, you can do the last reading. At this point, focus on the grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

Now, you can congratulate yourself. You made it! You wrote an entire research paper in a single day. It’s not smart to procrastinate until the last day. However, it’s not impossible to write a paper in such a short timeframe. Now, have a good sleep. You deserve it.

FREE 6-month trial

Then, enjoy Amazon Prime at half the price – 50% off!

TUN AI – Your Education Assistant

I’m here to help you with scholarships, college search, online classes, financial aid, choosing majors, college admissions and study tips!

TUN Helps Students!

Resource content.

Resources for Students

School Search

Scholarships

Scholarship Search

Start a Scholarship

High School

Copyright, 2024 – TUN, Inc

Student Tools

Free Online Courses

Student Discounts

Back to School

Internships

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Write a Paper in Two Days: A Timeline

Last week, Yuem wrote about keeping track of his progress on his senior thesis —a project with distant deadlines. As an underclassman, I usually face shorter-term deadlines for class essays and problem sets, and these require a similar, but condensed approach.

This post has real-life inspiration. Next Thursday, I have a paper due for my philosophy class on Nietzsche. Weekdays are busy with problem sets and assignments. I do not expect myself to start consolidating material for the paper till this weekend, which leaves me plenty of time to plan an effective essay.

Here’s the schedule I successfully used last time, when I was looking at parts of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra and the Gay Science. Granted, the whole process I’m proposing is longer than just two days, but I promise if you use the pre-writing steps I suggest, you’ll be able to do the actual writing in a much shorter period of time!

5 Days before Due Date: Finish the core readings!

I spent about half of my weekend finishing the readings for the class that I had not been able to finish in time for lecture. Surprisingly few people realize how helpful this is. In a paper-based class, certain prompts will lend themselves to specific readings. You can write a decent paper–maybe even get a “good grade”– by reading only what is absolutely necessary for a paper, but it will fall far short of your potential. You are surrounded by world-class facilities and faculty–don’t waste your time on something sub-par. The best part about writing a paper is finding unexpected connections, after all.

4 Days before Due Date: Summarize the readings.

After I finished reading and highlighting parts of the books, I sat down with a notebook and wrote down the gist of each section using what I had previously marked in the books. I used to do this as I read, but found it to take a long time to finish the process. Now, I read in whatever small bursts of time I have, and revisit my books to quickly take notes in one go using what I have highlighted. Now, I had a short summary of the assigned works in front of me as a map of what to reference.

3 Days before Due Date: Finalize essay topic and write an outline.

I narrowed my essay topics down to two, and drafted points I had in mind for each one. I did some outside research as well, and chose the topic I felt better prepared with. I started to construct an outline by selecting relevant quotes (using my summary of notes) and finally had a blocked version of evidence for different points in the paper. At this point, I started to work around the pieces of evidence I had written down and formulate logical arguments and transitions.

2 Days before Due Date: Talk to my professor, revise outline, and start writing!

By this point, I realized what crucial questions I had for my professor. I ran through some of the main points I was going to make in the paper and discovered that a few of them were faulty. I adapted accordingly and started to write!

Writing an eight page paper in two days was surprisingly easy with a well-developed outline. Do yourself a favor and spend the bulk of your time in the “planning” stage of an essay: reading, summarizing, outlining, and discussing ideas with classmates and professors. The actual writing process will be a matter of a few hours spent at your computer transferring thoughts from outline to paper in a format that flows well. Have a friend or two help you edit your paper, and you will emerge feeling rewarded.

— Vidushi Sharma, Humanities Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Peer Recognized

Make a name in academia

How to Write a Research Paper: the LEAP approach (+cheat sheet)

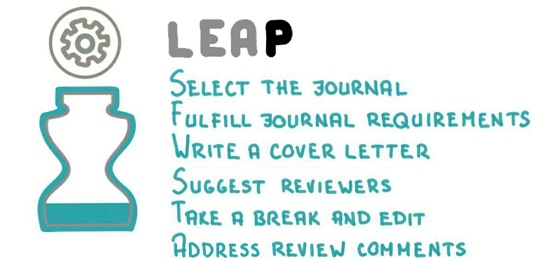

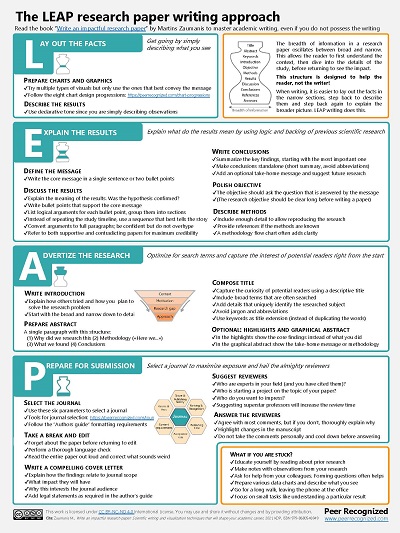

In this article I will show you how to write a research paper using the four LEAP writing steps. The LEAP academic writing approach is a step-by-step method for turning research results into a published paper .

The LEAP writing approach has been the cornerstone of the 70 + research papers that I have authored and the 3700+ citations these paper have accumulated within 9 years since the completion of my PhD. I hope the LEAP approach will help you just as much as it has helped me to make an real, tangible impact with my research.

What is the LEAP research paper writing approach?

I designed the LEAP writing approach not only for merely writing the papers. My goal with the writing system was to show young scientists how to first think about research results and then how to efficiently write each section of the research paper.

In other words, you will see how to write a research paper by first analyzing the results and then building a logical, persuasive arguments. In this way, instead of being afraid of writing research paper, you will be able to rely on the paper writing process to help you with what is the most demanding task in getting published – thinking.

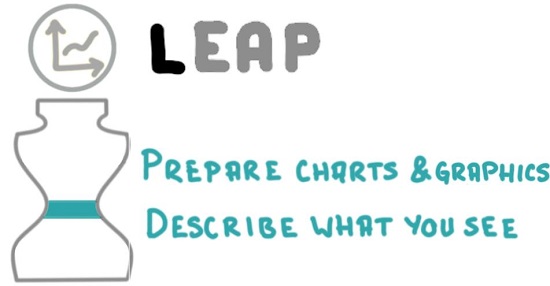

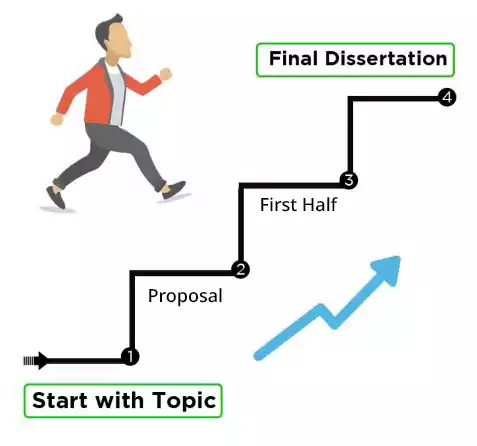

The four research paper writing steps according to the LEAP approach:

I will show each of these steps in detail. And you will be able to download the LEAP cheat sheet for using with every paper you write.

But before I tell you how to efficiently write a research paper, I want to show you what is the problem with the way scientists typically write a research paper and why the LEAP approach is more efficient.

How scientists typically write a research paper (and why it isn’t efficient)

Writing a research paper can be tough, especially for a young scientist. Your reasoning needs to be persuasive and thorough enough to convince readers of your arguments. The description has to be derived from research evidence, from prior art, and from your own judgment. This is a tough feat to accomplish.

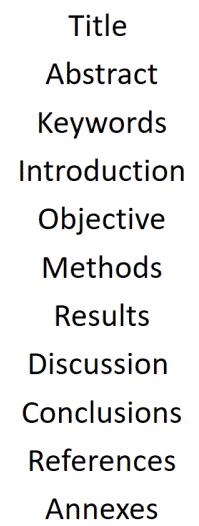

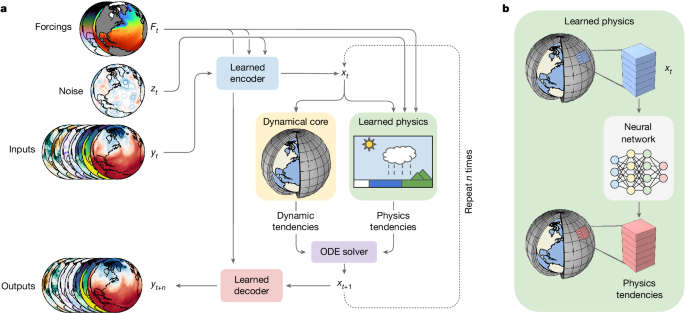

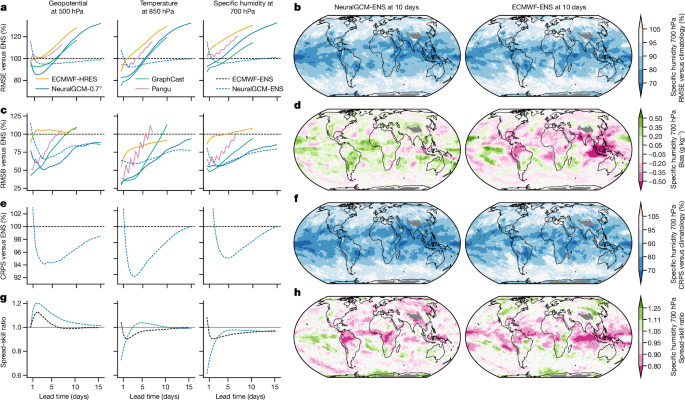

The figure below shows the sequence of the different parts of a typical research paper. Depending on the scientific journal, some sections might be merged or nonexistent, but the general outline of a research paper will remain very similar.

Here is the problem: Most people make the mistake of writing in this same sequence.

While the structure of scientific articles is designed to help the reader follow the research, it does little to help the scientist write the paper. This is because the layout of research articles starts with the broad (introduction) and narrows down to the specifics (results). See in the figure below how the research paper is structured in terms of the breath of information that each section entails.

How to write a research paper according to the LEAP approach

For a scientist, it is much easier to start writing a research paper with laying out the facts in the narrow sections (i.e. results), step back to describe them (i.e. write the discussion), and step back again to explain the broader picture in the introduction.

For example, it might feel intimidating to start writing a research paper by explaining your research’s global significance in the introduction, while it is easy to plot the figures in the results. When plotting the results, there is not much room for wiggle: the results are what they are.

Starting to write a research papers from the results is also more fun because you finally get to see and understand the complete picture of the research that you have worked on.

Most importantly, following the LEAP approach will help you first make sense of the results yourself and then clearly communicate them to the readers. That is because the sequence of writing allows you to slowly understand the meaning of the results and then develop arguments for presenting to your readers.

I have personally been able to write and submit a research article in three short days using this method.

Step 1: Lay Out the Facts

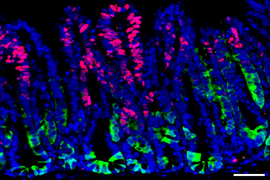

You have worked long hours on a research project that has produced results and are no doubt curious to determine what they exactly mean. There is no better way to do this than by preparing figures, graphics and tables. This is what the first LEAP step is focused on – diving into the results.

How to p repare charts and tables for a research paper

Your first task is to try out different ways of visually demonstrating the research results. In many fields, the central items of a journal paper will be charts that are based on the data generated during research. In other fields, these might be conceptual diagrams, microscopy images, schematics and a number of other types of scientific graphics which should visually communicate the research study and its results to the readers. If you have reasonably small number of data points, data tables might be useful as well.

Tips for preparing charts and tables

- Try multiple chart types but in the finished paper only use the one that best conveys the message you want to present to the readers

- Follow the eight chart design progressions for selecting and refining a data chart for your paper: https://peerrecognized.com/chart-progressions

- Prepare scientific graphics and visualizations for your paper using the scientific graphic design cheat sheet: https://peerrecognized.com/tools-for-creating-scientific-illustrations/

How to describe the results of your research

Now that you have your data charts, graphics and tables laid out in front of you – describe what you see in them. Seek to answer the question: What have I found? Your statements should progress in a logical sequence and be backed by the visual information. Since, at this point, you are simply explaining what everyone should be able to see for themselves, you can use a declarative tone: The figure X demonstrates that…

Tips for describing the research results :

- Answer the question: “ What have I found? “

- Use declarative tone since you are simply describing observations

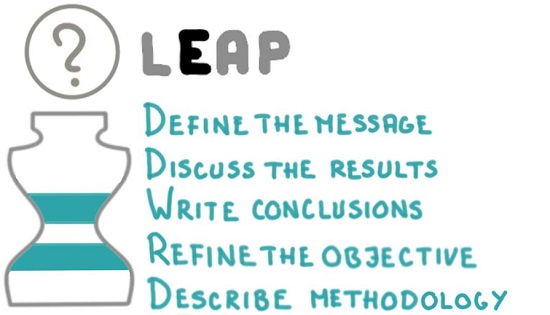

Step 2: Explain the results

The core aspect of your research paper is not actually the results; it is the explanation of their meaning. In the second LEAP step, you will do some heavy lifting by guiding the readers through the results using logic backed by previous scientific research.

How to define the Message of a research paper

To define the central message of your research paper, imagine how you would explain your research to a colleague in 20 seconds . If you succeed in effectively communicating your paper’s message, a reader should be able to recount your findings in a similarly concise way even a year after reading it. This clarity will increase the chances that someone uses the knowledge you generated, which in turn raises the likelihood of citations to your research paper.

Tips for defining the paper’s central message :

- Write the paper’s core message in a single sentence or two bullet points

- Write the core message in the header of the research paper manuscript

How to write the Discussion section of a research paper

In the discussion section you have to demonstrate why your research paper is worthy of publishing. In other words, you must now answer the all-important So what? question . How well you do so will ultimately define the success of your research paper.

Here are three steps to get started with writing the discussion section:

- Write bullet points of the things that convey the central message of the research article (these may evolve into subheadings later on).

- Make a list with the arguments or observations that support each idea.

- Finally, expand on each point to make full sentences and paragraphs.

Tips for writing the discussion section:

- What is the meaning of the results?

- Was the hypothesis confirmed?

- Write bullet points that support the core message

- List logical arguments for each bullet point, group them into sections

- Instead of repeating research timeline, use a presentation sequence that best supports your logic

- Convert arguments to full paragraphs; be confident but do not overhype

- Refer to both supportive and contradicting research papers for maximum credibility

How to write the Conclusions of a research paper

Since some readers might just skim through your research paper and turn directly to the conclusions, it is a good idea to make conclusion a standalone piece. In the first few sentences of the conclusions, briefly summarize the methodology and try to avoid using abbreviations (if you do, explain what they mean).

After this introduction, summarize the findings from the discussion section. Either paragraph style or bullet-point style conclusions can be used. I prefer the bullet-point style because it clearly separates the different conclusions and provides an easy-to-digest overview for the casual browser. It also forces me to be more succinct.

Tips for writing the conclusion section :

- Summarize the key findings, starting with the most important one

- Make conclusions standalone (short summary, avoid abbreviations)

- Add an optional take-home message and suggest future research in the last paragraph

How to refine the Objective of a research paper

The objective is a short, clear statement defining the paper’s research goals. It can be included either in the final paragraph of the introduction, or as a separate subsection after the introduction. Avoid writing long paragraphs with in-depth reasoning, references, and explanation of methodology since these belong in other sections. The paper’s objective can often be written in a single crisp sentence.

Tips for writing the objective section :

- The objective should ask the question that is answered by the central message of the research paper

- The research objective should be clear long before writing a paper. At this point, you are simply refining it to make sure it is addressed in the body of the paper.

How to write the Methodology section of your research paper

When writing the methodology section, aim for a depth of explanation that will allow readers to reproduce the study . This means that if you are using a novel method, you will have to describe it thoroughly. If, on the other hand, you applied a standardized method, or used an approach from another paper, it will be enough to briefly describe it with reference to the detailed original source.

Remember to also detail the research population, mention how you ensured representative sampling, and elaborate on what statistical methods you used to analyze the results.

Tips for writing the methodology section :

- Include enough detail to allow reproducing the research

- Provide references if the methods are known

- Create a methodology flow chart to add clarity

- Describe the research population, sampling methodology, statistical methods for result analysis

- Describe what methodology, test methods, materials, and sample groups were used in the research.

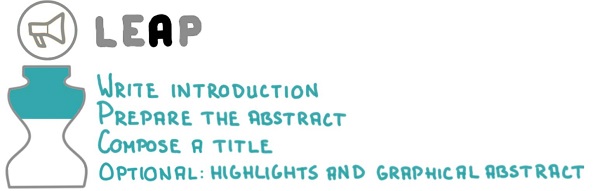

Step 3: Advertize the research

Step 3 of the LEAP writing approach is designed to entice the casual browser into reading your research paper. This advertising can be done with an informative title, an intriguing abstract, as well as a thorough explanation of the underlying need for doing the research within the introduction.

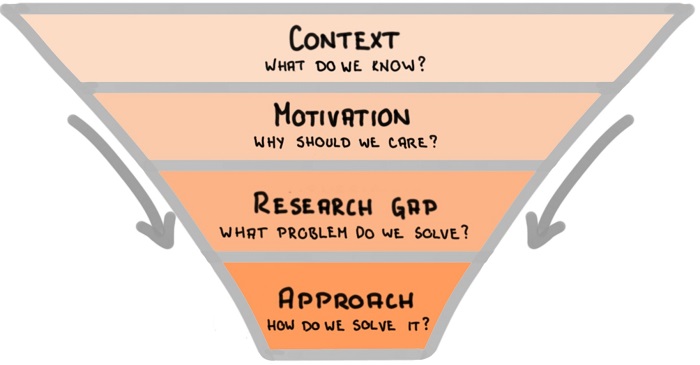

How to write the Introduction of a research paper

The introduction section should leave no doubt in the mind of the reader that what you are doing is important and that this work could push scientific knowledge forward. To do this convincingly, you will need to have a good knowledge of what is state-of-the-art in your field. You also need be able to see the bigger picture in order to demonstrate the potential impacts of your research work.

Think of the introduction as a funnel, going from wide to narrow, as shown in the figure below:

- Start with a brief context to explain what do we already know,

- Follow with the motivation for the research study and explain why should we care about it,

- Explain the research gap you are going to bridge within this research paper,

- Describe the approach you will take to solve the problem.

Tips for writing the introduction section :

- Follow the Context – Motivation – Research gap – Approach funnel for writing the introduction

- Explain how others tried and how you plan to solve the research problem

- Do a thorough literature review before writing the introduction

- Start writing the introduction by using your own words, then add references from the literature

How to prepare the Abstract of a research paper

The abstract acts as your paper’s elevator pitch and is therefore best written only after the main text is finished. In this one short paragraph you must convince someone to take on the time-consuming task of reading your whole research article. So, make the paper easy to read, intriguing, and self-explanatory; avoid jargon and abbreviations.

How to structure the abstract of a research paper:

- The abstract is a single paragraph that follows this structure:

- Problem: why did we research this

- Methodology: typically starts with the words “Here we…” that signal the start of own contribution.

- Results: what we found from the research.

- Conclusions: show why are the findings important

How to compose a research paper Title

The title is the ultimate summary of a research paper. It must therefore entice someone looking for information to click on a link to it and continue reading the article. A title is also used for indexing purposes in scientific databases, so a representative and optimized title will play large role in determining if your research paper appears in search results at all.

Tips for coming up with a research paper title:

- Capture curiosity of potential readers using a clear and descriptive title

- Include broad terms that are often searched

- Add details that uniquely identify the researched subject of your research paper

- Avoid jargon and abbreviations

- Use keywords as title extension (instead of duplicating the words) to increase the chance of appearing in search results

How to prepare Highlights and Graphical Abstract

Highlights are three to five short bullet-point style statements that convey the core findings of the research paper. Notice that the focus is on the findings, not on the process of getting there.

A graphical abstract placed next to the textual abstract visually summarizes the entire research paper in a single, easy-to-follow figure. I show how to create a graphical abstract in my book Research Data Visualization and Scientific Graphics.

Tips for preparing highlights and graphical abstract:

- In highlights show core findings of the research paper (instead of what you did in the study).

- In graphical abstract show take-home message or methodology of the research paper. Learn more about creating a graphical abstract in this article.

Step 4: Prepare for submission

Sometimes it seems that nuclear fusion will stop on the star closest to us (read: the sun will stop to shine) before a submitted manuscript is published in a scientific journal. The publication process routinely takes a long time, and after submitting the manuscript you have very little control over what happens. To increase the chances of a quick publication, you must do your homework before submitting the manuscript. In the fourth LEAP step, you make sure that your research paper is published in the most appropriate journal as quickly and painlessly as possible.

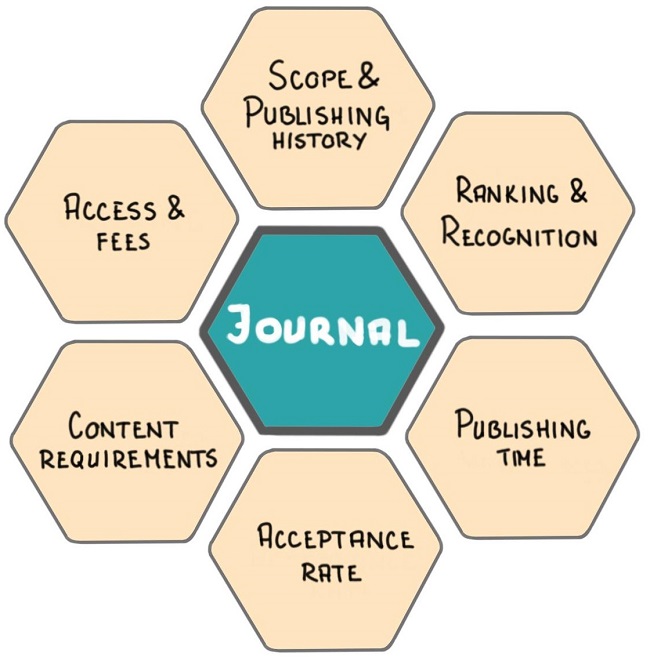

How to select a scientific Journal for your research paper

The best way to find a journal for your research paper is it to review which journals you used while preparing your manuscript. This source listing should provide some assurance that your own research paper, once published, will be among similar articles and, thus, among your field’s trusted sources.

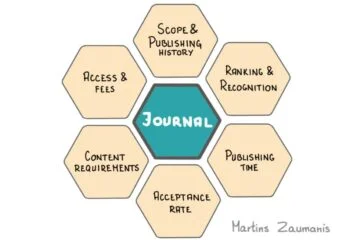

After this initial selection of hand-full of scientific journals, consider the following six parameters for selecting the most appropriate journal for your research paper (read this article to review each step in detail):

- Scope and publishing history

- Ranking and Recognition

- Publishing time

- Acceptance rate

- Content requirements

- Access and Fees

How to select a journal for your research paper:

- Use the six parameters to select the most appropriate scientific journal for your research paper

- Use the following tools for journal selection: https://peerrecognized.com/journals

- Follow the journal’s “Authors guide” formatting requirements

How to Edit you manuscript

No one can write a finished research paper on their first attempt. Before submitting, make sure to take a break from your work for a couple of days, or even weeks. Try not to think about the manuscript during this time. Once it has faded from your memory, it is time to return and edit. The pause will allow you to read the manuscript from a fresh perspective and make edits as necessary.

I have summarized the most useful research paper editing tools in this article.

Tips for editing a research paper:

- Take time away from the research paper to forget about it; then returning to edit,

- Start by editing the content: structure, headings, paragraphs, logic, figures

- Continue by editing the grammar and language; perform a thorough language check using academic writing tools

- Read the entire paper out loud and correct what sounds weird

How to write a compelling Cover Letter for your paper

Begin the cover letter by stating the paper’s title and the type of paper you are submitting (review paper, research paper, short communication). Next, concisely explain why your study was performed, what was done, and what the key findings are. State why the results are important and what impact they might have in the field. Make sure you mention how your approach and findings relate to the scope of the journal in order to show why the article would be of interest to the journal’s readers.

I wrote a separate article that explains what to include in a cover letter here. You can also download a cover letter template from the article.

Tips for writing a cover letter:

- Explain how the findings of your research relate to journal’s scope

- Tell what impact the research results will have

- Show why the research paper will interest the journal’s audience

- Add any legal statements as required in journal’s guide for authors

How to Answer the Reviewers

Reviewers will often ask for new experiments, extended discussion, additional details on the experimental setup, and so forth. In principle, your primary winning tactic will be to agree with the reviewers and follow their suggestions whenever possible. After all, you must earn their blessing in order to get your paper published.

Be sure to answer each review query and stick to the point. In the response to the reviewers document write exactly where in the paper you have made any changes. In the paper itself, highlight the changes using a different color. This way the reviewers are less likely to re-read the entire article and suggest new edits.

In cases when you don’t agree with the reviewers, it makes sense to answer more thoroughly. Reviewers are scientifically minded people and so, with enough logical and supported argument, they will eventually be willing to see things your way.

Tips for answering the reviewers:

- Agree with most review comments, but if you don’t, thoroughly explain why

- Highlight changes in the manuscript

- Do not take the comments personally and cool down before answering

The LEAP research paper writing cheat sheet

Imagine that you are back in grad school and preparing to take an exam on the topic: “How to write a research paper”. As an exemplary student, you would, most naturally, create a cheat sheet summarizing the subject… Well, I did it for you.

This one-page summary of the LEAP research paper writing technique will remind you of the key research paper writing steps. Print it out and stick it to a wall in your office so that you can review it whenever you are writing a new research paper.

Now that we have gone through the four LEAP research paper writing steps, I hope you have a good idea of how to write a research paper. It can be an enjoyable process and once you get the hang of it, the four LEAP writing steps should even help you think about and interpret the research results. This process should enable you to write a well-structured, concise, and compelling research paper.

Have fund with writing your next research paper. I hope it will turn out great!

Learn writing papers that get cited

The LEAP writing approach is a blueprint for writing research papers. But to be efficient and write papers that get cited, you need more than that.

My name is Martins Zaumanis and in my interactive course Research Paper Writing Masterclass I will show you how to visualize your research results, frame a message that convinces your readers, and write each section of the paper. Step-by-step.

And of course – you will learn to respond the infamous Reviewer No.2.

Hey! My name is Martins Zaumanis and I am a materials scientist in Switzerland ( Google Scholar ). As the first person in my family with a PhD, I have first-hand experience of the challenges starting scientists face in academia. With this blog, I want to help young researchers succeed in academia. I call the blog “Peer Recognized”, because peer recognition is what lifts academic careers and pushes science forward.

Besides this blog, I have written the Peer Recognized book series and created the Peer Recognized Academy offering interactive online courses.

Related articles:

One comment

- Pingback: Research Paper Outline with Key Sentence Skeleton (+Paper Template)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I want to join the Peer Recognized newsletter!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Copyright © 2024 Martins Zaumanis

Contacts: [email protected]

Privacy Policy

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

Can you help me with a full paper template for this Abstract:

Background: Energy and sports drinks have gained popularity among diverse demographic groups, including adolescents, athletes, workers, and college students. While often used interchangeably, these beverages serve distinct purposes, with energy drinks aiming to boost energy and cognitive performance, and sports drinks designed to prevent dehydration and replenish electrolytes and carbohydrates lost during physical exertion.

Objective: To assess the nutritional quality of energy and sports drinks in Egypt.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study assessed the nutrient contents, including energy, sugar, electrolytes, vitamins, and caffeine, of sports and energy drinks available in major supermarkets in Cairo, Alexandria, and Giza, Egypt. Data collection involved photographing all relevant product labels and recording nutritional information. Descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests were employed to analyze and compare the nutritional values of energy and sports drinks.

Results: The study analyzed 38 sports drinks and 42 energy drinks. Sports drinks were significantly more expensive than energy drinks, with higher net content and elevated magnesium, potassium, and vitamin C. Energy drinks contained higher concentrations of caffeine, sugars, and vitamins B2, B3, and B6.

Conclusion: Significant nutritional differences exist between sports and energy drinks, reflecting their intended uses. However, these beverages’ high sugar content and calorie loads raise health concerns. Proper labeling, public awareness, and responsible marketing are essential to guide safe consumption practices in Egypt.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Home > Blog > Tips for Online Students > Tips for Students > Hacks How to Write a 10 and 20 page Paper in One Night

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Hacks How to Write a 10 and 20 page Paper in One Night

Updated: June 19, 2024

Published: April 19, 2020

It’s the night before a big paper is due. For whatever reason, you find yourself needing to write an entire research paper in a very short amount of time. While procrastination isn’t ideal, extenuating circumstances may have caused your timeline to get pushed back. So, here you are, looking for how to write a 10-page paper or how to write a 20-page paper in one night.

It goes without saying the best way to write a paper is to give yourself enough time to outline, draft, and edit. Yet, it’s still possible to write in less time. Take heed of these best tips and tricks to organize your thoughts and get your thesis on paper as fast as possible.

Photo by Adolfo Félix on Unsplash

How to prepare before you write, 1. create a schedule to maximize your time.

You’ve likely already spent time panicking. Once you calm yourself of the anxiety of having to finish a 10- or 20-page paper in one night, organize your plan of attack. First, you should designate an area free of distractions so that you can focus. Aside from a few breaks and snacks, it’s best to set up a comfortable place to write. Give yourself some time to outline and find/cite research . Once you know how you’re going to approach the subject, then you can start drafting.

2. Determine your Main Topic

If you’ve been given a prompt, then your topic is clear. However, sometimes you have the freedom to choose what your research will be about. In this case, it’s smartest to choose a topic that you are already knowledgeable about. That way, you will save yourself key time that would have otherwise been spent on research. If you don’t feel strongly about any particular topic, then at least try to pick one that has a lot of information available.

3. Perform Research

Start looking up sources to cite that support your thesis, or main argument. As you research, be sure to take notes. One of the best ways to do this is to use a word processor like Google Docs or Microsoft Word to copy and paste URLs. For each source, it would be best to copy/paste one main sentence that covers its point.

Then, you can write brief notes in your own words that summarize what you have read from that source. While you are performing research, you can start to put together an outline, or the flow of how you will present your ideas broken down by topic and argument.

4. Outline 3-5 subtopics

Once you’ve chosen your topic, then try to pull 3-5 subtopics from it. Each sub-topic should be juicy enough to be able to write a lot about it. The subtopics are your supporting paragraphs which fill the body of the research paper. They should basically be mini essays within themselves.

Writing in One Night

Writing a long research paper in one night isn’t ideal, but it is doable. Some of the best ways to get it done is to follow these 5 tips:

1. Plan and Outline

Take those few extra moments to plan and outline your paper. While it may feel like a waste of valuable time, it is going to help you stay on track. When you have an outline and you get to the middle of your paper, you won’t feel lost as to how to continue. An outline will be useful to you like a map is on a journey.

2. Use Specialized Search

Take advantage of search tools that are designed for scholars. For example, a few of these include: Google Scholar and Elsevier .

3. Leverage Tools

There are citation management tools that will help you find sources for your topic. Mendeley is just one of them. You can type parts of your paper into the tool and find quotes of value. Be sure to cite everything you use to avoid plagiarism .

4. Proofread and Edit

Once you complete writing 10 to 20 pages, you may feel like throwing in the towel and going to sleep for a few hours. However, it is crucial to power through and proofread your paper. If you have anyone available who can read your paper over, that would be best because it’s hard to catch mistakes when you’ve been looking at the same thing for so long. But, if no one is available, try to read your paper back to yourself out loud. This way, you may be able to catch typos better.

5. Check Formatting

Every research paper needs to adhere to a particular format guideline. Whether it’s APA, MLA, or another standard formatting practice, be sure to double check that your layout adheres to the guidelines.

Photo by Christin Hume on Unsplash

When to start writing.

If you have yet to find yourself trying to write a paper at the last minute and all the notes above are scaring you out of procrastination, then that’s a good start! Perhaps you were recently assigned a research paper. In this case, the best way to tackle the project is to do the following:

Start Early

Get started right away. Even if it means just performing early research or writing an outline, starting early is going to save you from having to write a paper in one night down the line. When you start early, you benefit greatly because you can: leverage peers for ideas, take the necessary time to edit and rewrite, and you lower your risk of picking a topic with too little information and having to change topics at the last minute.

Writing in Stages

Starting early also affords you the opportunity to write in stages. You can think of writing as a cycle when you write in stages. First, you can create your outline. Then, you can write the introduction, edit it, and rewrite anything you may need to before moving on to the next piece (or the first body paragraph, in this case).

Use a Timeline

Create a timeline for your writing in stages. If you start four weeks in advance, for example, you have time to do all of the following:

- Fully understand the assignment and ask any questions

- Start to read and document sources

- Create notecards and cite books for sources

- Write a summary of what you’ve discovered so far that will be used in some of your paper

- Create 3-5 subtopics and outline points you want to explore

- Look for more sources on your subtopics

- Start writing summaries on each subtopic

- Write some analysis of your findings

- Start to piece together the research paper based on your notes and outline (almost like completing a puzzle)

- Edit and proofread / ask for feedback

The Writing Process

The actual writing process is a little different for everyone, but this is a general overview for how to write a 20-page paper, or one that is shorter.

- Start with a Thesis: Your thesis is one sentence that clearly and concisely explains what you are going to prove with research.

- Include a Menu Sentence: At the end of your introduction, you will briefly outline your subtopics in what is often referred to as a “menu sentence.” This allows the reader to understand what they can expect to learn about as they continue to read your paper.

- Create a Detailed Introduction: Your introduction should be detailed enough so that someone with little to no knowledge about your subject matter can understand what the paper is about.

- Keep References: Be sure to write your references as you go along so that you basically can create your bibliography in the process of writing. Again, this is where a tool like Mendeley may be useful.

- Write First: Write first and edit later. You want to get all your ideas down on the page before you start judging or editing the writing.

- Save Often: Create the draft on a cloud platform that is automatically saved (i.e. Google Docs in case your computer crashes) or email the work to yourself as you go.

The Breakdown of a 10-Page Paper

Sources to Consider Using

When writing your research paper and finding sources, it’s best to use a mix of sources. This may include:

- Internet: The Internet is filled with limitless possibilities. When you use the Internet, it’s best to find credible and trustworthy sources to avoid using fake news as a source. That’s why tools like Google Scholar can be so helpful.

- Textbooks: It’s more likely than not that you’ll be able to use your class textbook as a source for the research you are conducting.

- Books: Additionally, other books outside of those you read within your class will prove useful in any research paper.

Final Steps: Editing and Formatting

Once you’ve written all your ideas on the page, it’s time to edit. It cannot be stressed enough that editing is pivotal before submission. This is especially true if you’ve been writing under immense pressure.

Writing a 10- or 20-page research paper in one night is not easy, so there are bound to be mistakes and typos. The best way to catch these mistakes is to follow these tips:

- Take a break before you edit so you can come back to the page with somewhat fresh eyes and a clearer head

- Read it out loud to edit and catch mistakes because sometimes your brain will override typos or missing words to make sense of what it is reading

- If possible, ask someone else to look it over

- Consider using footnotes or block quotes

- Format according to how your university asks – MLA or APA, etc.

The Bottom Line

Life throws curveballs your way without warning. Whether you are holding yourself accountable for procrastinating or something out of your control came up, you may find yourself needing to write a big research paper in one night. It’s not the best-case scenario, but with the right tools and tricks up your sleeve, you can surely get it done!

In this article

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone. Read More

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

How to Write a Research Paper | A Beginner's Guide

A research paper is a piece of academic writing that provides analysis, interpretation, and argument based on in-depth independent research.

Research papers are similar to academic essays , but they are usually longer and more detailed assignments, designed to assess not only your writing skills but also your skills in scholarly research. Writing a research paper requires you to demonstrate a strong knowledge of your topic, engage with a variety of sources, and make an original contribution to the debate.

This step-by-step guide takes you through the entire writing process, from understanding your assignment to proofreading your final draft.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Understand the assignment, choose a research paper topic, conduct preliminary research, develop a thesis statement, create a research paper outline, write a first draft of the research paper, write the introduction, write a compelling body of text, write the conclusion, the second draft, the revision process, research paper checklist, free lecture slides.

Completing a research paper successfully means accomplishing the specific tasks set out for you. Before you start, make sure you thoroughly understanding the assignment task sheet:

- Read it carefully, looking for anything confusing you might need to clarify with your professor.

- Identify the assignment goal, deadline, length specifications, formatting, and submission method.

- Make a bulleted list of the key points, then go back and cross completed items off as you’re writing.

Carefully consider your timeframe and word limit: be realistic, and plan enough time to research, write, and edit.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

There are many ways to generate an idea for a research paper, from brainstorming with pen and paper to talking it through with a fellow student or professor.

You can try free writing, which involves taking a broad topic and writing continuously for two or three minutes to identify absolutely anything relevant that could be interesting.

You can also gain inspiration from other research. The discussion or recommendations sections of research papers often include ideas for other specific topics that require further examination.

Once you have a broad subject area, narrow it down to choose a topic that interests you, m eets the criteria of your assignment, and i s possible to research. Aim for ideas that are both original and specific:

- A paper following the chronology of World War II would not be original or specific enough.

- A paper on the experience of Danish citizens living close to the German border during World War II would be specific and could be original enough.

Note any discussions that seem important to the topic, and try to find an issue that you can focus your paper around. Use a variety of sources , including journals, books, and reliable websites, to ensure you do not miss anything glaring.

Do not only verify the ideas you have in mind, but look for sources that contradict your point of view.

- Is there anything people seem to overlook in the sources you research?

- Are there any heated debates you can address?

- Do you have a unique take on your topic?

- Have there been some recent developments that build on the extant research?

In this stage, you might find it helpful to formulate some research questions to help guide you. To write research questions, try to finish the following sentence: “I want to know how/what/why…”

A thesis statement is a statement of your central argument — it establishes the purpose and position of your paper. If you started with a research question, the thesis statement should answer it. It should also show what evidence and reasoning you’ll use to support that answer.

The thesis statement should be concise, contentious, and coherent. That means it should briefly summarize your argument in a sentence or two, make a claim that requires further evidence or analysis, and make a coherent point that relates to every part of the paper.

You will probably revise and refine the thesis statement as you do more research, but it can serve as a guide throughout the writing process. Every paragraph should aim to support and develop this central claim.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

A research paper outline is essentially a list of the key topics, arguments, and evidence you want to include, divided into sections with headings so that you know roughly what the paper will look like before you start writing.

A structure outline can help make the writing process much more efficient, so it’s worth dedicating some time to create one.

Your first draft won’t be perfect — you can polish later on. Your priorities at this stage are as follows:

- Maintaining forward momentum — write now, perfect later.

- Paying attention to clear organization and logical ordering of paragraphs and sentences, which will help when you come to the second draft.

- Expressing your ideas as clearly as possible, so you know what you were trying to say when you come back to the text.

You do not need to start by writing the introduction. Begin where it feels most natural for you — some prefer to finish the most difficult sections first, while others choose to start with the easiest part. If you created an outline, use it as a map while you work.

Do not delete large sections of text. If you begin to dislike something you have written or find it doesn’t quite fit, move it to a different document, but don’t lose it completely — you never know if it might come in useful later.

Paragraph structure

Paragraphs are the basic building blocks of research papers. Each one should focus on a single claim or idea that helps to establish the overall argument or purpose of the paper.

Example paragraph

George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” has had an enduring impact on thought about the relationship between politics and language. This impact is particularly obvious in light of the various critical review articles that have recently referenced the essay. For example, consider Mark Falcoff’s 2009 article in The National Review Online, “The Perversion of Language; or, Orwell Revisited,” in which he analyzes several common words (“activist,” “civil-rights leader,” “diversity,” and more). Falcoff’s close analysis of the ambiguity built into political language intentionally mirrors Orwell’s own point-by-point analysis of the political language of his day. Even 63 years after its publication, Orwell’s essay is emulated by contemporary thinkers.

Citing sources

It’s also important to keep track of citations at this stage to avoid accidental plagiarism . Each time you use a source, make sure to take note of where the information came from.

You can use our free citation generators to automatically create citations and save your reference list as you go.

APA Citation Generator MLA Citation Generator