Navigation Menu

Search code, repositories, users, issues, pull requests..., provide feedback.

We read every piece of feedback, and take your input very seriously.

Saved searches

Use saved searches to filter your results more quickly.

To see all available qualifiers, see our documentation .

- Notifications You must be signed in to change notification settings

Coursera Quantitative Methods Assignments (2016)

rkiyengar/coursera-quant-methods

Folders and files.

| Name | Name | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 Commits | ||||

Repository files navigation

Coursera_quantitative_methods.

This repo contains files related to the Quantitative Methods course on Coursera.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.79(8); 2015 Oct 25

Assessment of a Revised Method for Evaluating Peer-graded Assignments in a Skills-based Course Sequence

Objective. To evaluate the modified peer-grading process incorporated into the SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) note sessions in a skills-based pharmacy course sequence.

Design. Students assessed a de-identified peer’s SOAP note in a faculty-led peer-grading session followed by an optional grade challenge opportunity. Using paired t tests, final session grades (peer-graded with challenge opportunity) were compared with the retrospective faculty-assigned grades. Additionally, students responded to a survey using 4-point Likert scale and open-answer items to assess their perceptions of the process.

Assessment. No significant difference was found between mean scores assigned by faculty members vs those made by student peers after participation in 3 SOAP note sessions, which included a SOAP note-writing workshop, a peer-grading workshop, and a grade challenge opportunity. The survey data indicated that students generally were satisfied with the process.

Conclusion. This study provides insight into the peer-grading process used to evaluate SOAP notes. The findings support the continued use of this assessment format in a skills-based course.

INTRODUCTION

The formulation and documentation of patient care plans is a skill central to the provision of patient-centered care, supported by the Center for Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) 2013 Educational Outcomes. 1 To teach and evaluate this skill, Midwestern University College of Pharmacy – Glendale (MWU-CPG) incorporated a series of active-learning experiences relevant to pharmacy practice using the “subjective, objective, assessment, plan” (SOAP) written documentation format. Supplementing each SOAP note-writing workshop, students assessed and scored an anonymous peer’s written SOAP assignment using a faculty-developed rubric in a required faculty-led workshop, followed by a self-reflection opportunity.

This assessment method was designed to meet the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Draft Standards 2016 recommendation that schools and colleges should “utilize teaching/learning methods that facilitate achievement of learning outcomes, actively engage learners, promote self-directed learning, and foster collaborative learning”. 2 In addition, this method helps address Domain 4 of the CAPE 2013 Outcomes, which focuses on educating future pharmacists to be self-aware by providing a structured opportunity to develop the skills of peer- and self-assessment. 1

Peer assessment not only serves as a grading procedure, but a method to practice self-evaluation skills. Peer assessment is a valuable form of assessment in higher education for a variety of assignments, and students generally perceive it as beneficial. 3 Peer assessment is used in pharmacy education for student case presentations, laboratory courses, medication management assignments, patient interviews, and advanced practice experiences. 4-9

A proposed benefit of the peer assessment strategy is providing an enhanced learning environment for students in which a high order of thinking is utilized and guided by evaluation. Other benefits include self-reflection, peer interaction, and a decreased faculty workload. 4 Finally, peer assessment can help to foster higher levels of responsibility among students by requiring them to be fair and accurate with the feedback and evaluations they make of their peers. 3 Limitations identified in previous research include a lack of student understanding of the purpose of the peer-grading session, lack of student experience in grading, and lack of confidentiality. In these studies, peer grades were generally higher than faculty grades for the assignments. 4-9

A previous study comparing student and faculty scores for 3 peer-graded assignments at the college resulted in the students assigning significantly lower scores than faculty members to student peers, which was inconsistent with other research. 10 One goal of using peer grading was to replace the need for traditional faculty SOAP note grading, so several changes were made to improve the consistency of faculty and peer-assigned scores. A standardized format, titled the Comprehensive Medication Management Plan (CMMP), was adopted for guiding SOAP-note writing, which detailed the expectations for each section and served as the basis for the grading checklists used in the peer-grading sessions. This approach attempted to provide the students clear and consistent expectations among different faculty members when formulating their written SOAP note.

Additionally, a “challenge” opportunity was implemented to allow each student the chance to self-evaluate their peer-graded note prior to the final grade assignment and submit a grade challenge if appropriate. 10 Outcomes of a “challenge” strategy, including the accuracy of final grades after this opportunity, has not been formally evaluated in the literature. The intent of these changes was to improve the scoring process so the peer-assigned scores would be similar to those assigned by a faculty grader, thus validating the peer-grading process used for the SOAP notes sessions as a stand-alone assessment.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the modified peer-grading process incorporated into the SOAP note sessions. The specific aims were to compare the final recorded student grade (given after the SOAP note session and “challenge” opportunity) with a retrospective traditional faculty-assigned grade, and to gather the student’s perceptions about the process.

Professional Skills Development (PSD) is a required 8-quarter, workshop-based course sequence in a 3-year didactic curriculum (PSD 1-8). In the second year of the sequence in 2012-2013, there are 3 SOAP note sessions. Each session consists of 3 parts: a writing workshop, a peer-grading workshop, and a challenge opportunity that build on the foundational knowledge taught in the therapeutic course sequence (PSD 5, 6, and 8). The final score received after the 3 sessions is considered a summative assessment of this knowledge.

This study involved a single cohort of students completing the second year of their PSD sequence. All students enrolled in PSD were required to participate in the 3 SOAP note sessions. The case content for each session corresponded to the material taught by the subject matter expert in the concurrent therapeutics course during each of the 3 quarters (hyperlipidemia, psychiatry, and cardiovascular). The subject matter expert also designed the case and grading checklist, led the peer-grading workshop, was present at the challenge opportunity, and graded the challenge submissions.

Organization of Sessions

For each SOAP note writing workshop, students were given a template prior to writing their SOAP note, which included a list of medical problems students were required to address for the patient case. Given the subjective and objective data, students were asked to individually write the assessment and plan for the patient. The first SOAP note-writing workshop was completed outside of class and submitted via Safe Assign, a program found in the Blackboard learning system (Blackboard Inc., Washington, DC), to check for plagiarism. The other 2 SOAP note-writing workshops were completed within a 2-hour time block in the university’s testing center. The subject matter expert was not present at the writing workshop. To aid in developing their assessment and plan, students were given a CMMP grid ( Appendix I ). Completion of the CMMP was optional during the SOAP note-writing workshops, although highly encouraged, as the grading checklists for each note were based on the same categories.

Peer-grading workshops occurred during class time within one week of completing the writing workshop. Each of the 3 peer-grading workshops were held in 2 sections (2 hours each) on the same day to accommodate one-half of the class at a time. This ensured that students who wrote the SOAP notes being evaluated were not present in that particular section of the peer-grading workshop. In an effort to hold the students accountable for attending the session, for grading the SOAP note to the best of their ability, and for providing quality feedback to their peers, students wrote their names on the cover sheet of the evaluation form. The course coordinator kept track of who graded each SOAP note, but students and the subject matter expert were blinded throughout the entire process. The grading checklist was distributed first, prior to the cases to be graded. The subject matter expert directed the students to review the grading checklist point by point. This was an opportunity for students to reflect on what they had individually written on their own note and ask questions for clarification, prior to being held responsible for grading a peer’s note. Peer notes then were distributed, and students were given approximately 20 minutes to read through their assigned note and grade based off of the supplied grading checklist. Once students had completed grading, they again reviewed the rubric. At this time, students could request whether an alternative written response not included within the grading checklist be considered for points by the subject matter expert facilitating the session. Once the grading was complete, students were instructed to provide anonymous constructive written feedback to their peers.

A 1-hour challenge opportunity was offered within 24 hours after each peer-grading workshop for students to review their peer-graded note and to challenge their peer-assigned grade. Only students who attended the challenge opportunity had the ability to submit a challenge form. If students wanted to proceed with a challenge, they completed a preprinted form specifying which point(s) they wanted to challenge and providing justification for each. The subject matter expert was present at the challenge opportunity to answer additional student questions regarding the case or their responses. After the challenge opportunity, the subject matter expert reviewed the challenge forms and addressed only the inaccuracies noted by the student. However, the subject matter expert reserved the right to regrade the assignment if necessary. Grade challenges were not accepted after this session was completed.

Evaluation of Sessions

To evaluate the scores assigned during each of the 3 SOAP note sessions, the subject matter expert retrospectively graded each assignment using the standard grading checklist used in the peer-grading workshop which modeled the traditional grading method used at the college. This traditional method did not include a peer-grading workshop or challenge opportunity and resulted only in a scored rubric with written comments. The subject matter expert was blinded to the student names and all results of the peer-grading workshop and/or challenge opportunity.

The final session grades (peer-graded with challenge opportunity) were compared to the retrospective faculty-assigned grades for each session. Evaluations were made using paired t tests with a p value of ≤0.05 being considered significant. An anonymous survey was also administered to all students enrolled in the final quarter of the PSD course sequence. The survey was voluntarily completed during a course period after the last of the three SOAP note sessions. The survey assessed the students’ opinions of the SOAP note sessions utilizing 4-point Likert scale statements, multiple-choice questions, and open-ended questions. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze the findings of the survey. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Midwestern University.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Scores for 453 peer-graded assignments (151 for session 1, 152 for session 2, and 150 for session 3) were analyzed. No difference was found between the mean scores for final recorded grades and retrospective faculty assigned grades ( Table 1 ). Differences between the mean scores for each of the 3 individual sessions were 0.8, 0.9, and 1.3, respectively. A subgroup analysis was performed to compare the final recorded grades and the retrospective faculty-assigned grades based on participation in the challenge opportunity ( Table 2 ).

Final Recorded Grades Using Peer-Grading Method vs Retrospective, Traditional Faculty Grades for 3 Sessions

Final Recorded Grades Using Peer-Grading Method vs Retrospective, Traditional Faculty Grades for 3 Sessions Based on Participation in the Challenge Opportunity

We found that for all 3 sessions combined, 158 students (35%) challenged their peer-graded SOAP note for faculty review (93% of which resulted in a score change), 243 (54%) reviewed their peer-graded note but did not challenge for faculty review, and 52 (11%) did not review their assignment. No difference was found if the student reviewed their submission and either opted to challenge or not to challenge. However, there was a significantly lower score assigned for students who did not review their assignments in the challenge opportunity.

One hundred twenty students (80%) participated in the survey assessing their perspectives on the SOAP note sessions. ( Table 3 ) Responses from 2 surveys were not included because the respondents did not meet the criteria of having attended at least two challenge opportunities. Regarding the SOAP note-writing workshop and subsequent peer-grading workshop, the majority of students either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the CMMP helped them structure their SOAP notes (89%), the instructions for participating in the sessions were clear (96%), the grading checklists were easy to follow (95%), the peer grading sessions enhanced learning (70%), and faculty guidance during the peer-grading workshops allowed them to effectively grade a peer’s note (90%). Regarding the challenge opportunity, the majority of students either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the challenge opportunity allowed them to self-reflect on their work (73%), that the challenge sessions are necessary to receive a fair score on peer-graded assignments (89%), and that faculty members awarded points fairly after the grade challenge opportunity (77%). The lowest score was in response to whether peer-provided comments were constructive and useful in improving SOAP note skills. However, 54% of the students“agreed” or “strongly” agreed with this statement as well.

Students’ Opinions Regarding SOAP Note Sessions in the Professional Skills Development Course Sequence

The open-ended questions asked what the students liked most and least about the SOAP note sessions and suggestions for improvement. ( Table 4 ) Students most commonly stated that their learning was enhanced by exposure to the various ways their peers approached the case. Other commonly reported responses included enhancement of disease state knowledge through immediate faculty feedback, fairness in grading, and improvement of general SOAP note-writing skills.

Student Comments Regarding Peer Grading Process in the Professional Skills Development Course Sequence

The majority of the responses regarding what students liked least included the process taking too long or classmates asking too many questions. Other common responses included inconsistency in points awarded by peer graders, rubrics being too strict, and reviewing the rubric prior to starting taking too much time or being too repetitive. The most frequent responses for how to improve the process included structuring the sessions to take less time and/or limiting the number of questions asked by other students. Other suggestions included revising the rubrics to be less stringent, holding the graders accountable for inaccuracy in grading, and allowing the notes to be typed instead of handwritten.

The revised peer-grading process for SOAP note sessions in the PSD course sequence resulted in the same overall score when compared to traditional faculty grading. This contrasts to a previous study, which showed higher traditional faculty-assigned scores than student peer-assigned scores. 8 This result strengthens our confidence in the use of the process in place of traditional faculty grading. The most likely contributor to this result was the institution of the challenge opportunity; allowing students to self-assess their work, review peer comments, and submit a challenge form if inaccuracies were noted. In the subgroup analysis, we noted a difference in the final recorded grade vs the traditional faculty-assigned grades for those students who did not participate in the challenge session.

The use of the CMMP document was another possible contributor to the equalized scores, since it served as a structure by which all grading checklists were formatted. This may have streamlined the grading process by improving the clarity of the grading checklists used in the peer grading sessions.

Advantages and disadvantages of the peer-grading process from student and faculty perspectives were noted. Student noted that learning from their peers’ approach to the case, obtaining immediate faculty feedback that enhanced disease state knowledge, and fair grading were advantages. From the faculty perspective, an advantage to this process was the reduced faculty grading workload. Scoring student-submitted challenge forms (n=158) took a total of approximately 3 hours for the subject matter experts to complete. In contrast, scoring each submission separately (n=453) for the purposes of this research approximated 10 minutes per submission.

This process is not without disadvantages. Some students said the peer-grading workshop took too long because other students asked too many questions even though the workshop was limited to 2 hours and was conducted during normal course time. Some also indicated an inconsistency among peer graders and may have viewed the challenge as an opportunity to double-check their peers rather than an opportunity for self-reflection. Finally, some students indicated a lack of constructive feedback from peers despite receiving examples from instructors of appropriate vs inappropriate feedback. One disadvantage from a faculty perspective was the negative connotation implied by the terms “peer-grading” and “challenge opportunity.” Despite an formal orientation on the benefits of peer and self-assessment, some students perceived this process as a way for faculty members to decrease their workload and transfer the burden to students.

There are several limitations to this research. The 3 SOAP note sessions were each designed, conducted, and graded by 3 different subject matter experts and focused on a wide array of therapeutic topics. Given this, the students’ perceptions about the process could be influenced by the therapeutic topic or faculty member. Additionally, the SOAP note sessions were conducted in the fall, winter, and summer quarters, while the survey was administered at the end of the final session, possibly reflecting the students’ opinions of the most recent session. Finally, this study is reflective of a specific cohort of pharmacy students enrolled in a workshop-based course sequence that may not be applicable to other schools or other disciplines.

The SOAP note sessions in PSD have continued with subsequent student cohorts, without the use of traditional faculty grading. Several adjustments have been instituted based on the findings of this study. For example, in addition to the formal orientation, a more formal method for providing peer feedback has been instituted. After the peer-grading workshop, students are asked to state 3 things the author did well and 3 areas for improvement. Additionally, the procedure during the peer-grading workshop has been streamlined to allow students to grade peers’ submissions at the beginning of each session in pencil, eliminating the initial faculty review of the rubric with the class. Once all individual grading is complete, the subject matter expert reviews the rubric and entertains student questions and feedback. This change was based on feedback that students found it redundant to review the rubric twice and that it lengthened the overall session time. Finally, the description and name of this process has changed from “peer grading” to “peer assessment” to further convey the positive academic intent of the process. In addition, the term “challenge” opportunity was changed to “self-reflection and review workshop” to promote the individual benefits of participating in the process.

This study provides insight into the peer-grading process used in the PSD course sequence at the college. Our findings indicated no difference between grades assigned to students using the peer-grading process and traditional faculty grades for all 3 sessions. Additionally, students perceived that the process was beneficial to their learning, supporting the continued use of this assessment format in our curriculum. We feel the process has the potential to be successfully used in other professional programs as well.

Appendix 1.

Comprehensive Medication Management Plan (CMMP)

Task Assignment of Peer Grading in MOOCs

- Conference paper

- First Online: 22 March 2017

- Cite this conference paper

- Yong Han 17 ,

- Wenjun Wu 17 &

- Yanjun Pu 17

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Computer Science ((LNISA,volume 10179))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications

1653 Accesses

1 Citations

In a massive online course with hundreds of thousands of students, it is unfeasible to provide an accurate and fast evaluation for each submission. Currently the researchers have proposed the algorithms called peer grading for the richly-structured assignments. These algorithms can deliver fairly accurate evaluations through aggregation of peer grading results, but not improve the effectiveness of allocating submissions. Allocating submissions to peers is an important step before the process of peer grading. In this paper, being inspired from the Longest Processing Time (LPT) algorithm that is often used in the parallel system, we propose a Modified Longest Processing Time (MLPT), which can improve the allocation efficiency. The dataset used in this paper consists of two parts, one part is collected from our MOOCs platform, and the other one is manually generated as the simulation dataset. We have shown the experimental results to validate the effectiveness of MLPT based on the two type datasets.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Benchmarking Partial Credit Grading Algorithms for Proof Blocks Problems

A Peer Grading Tool for MOOCs on Programming

Multi-criteria Fuzzy Ordinal Peer Assessment for MOOCs

Fonteles, A.S., Bouveret, S., Gensel, J.: Heuristics for task recommendation in spatiotemporal crowdsourcing systems. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing and Multimedia, pp. 1–5. ACM (2015)

Google Scholar

Cheng, J., Teevan, J., Bernstein, M.S.: Measuring crowdsourcing effort with error-time curves. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1365–1374. ACM (2015)

Qiu, C., Squicciarini, A.C., Carminati, B., et al.: CrowdSelect: increasing accuracy of crowdsourcing tasks through behavior prediction and user selection. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, pp. 539–548. ACM (2016)

Howe, J.: The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired Mag. 14 (6), 1–4 (2006)

Wiki for Multiprocessor Scheduling Information. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiprocessor_scheduling

Piech, C., Huang, J., Chen, Z., et al.: Tuned models of peer assessment in MOOCs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1307.2579 (2013)

Coffman, Jr. E.G., Sethi, R.: A generalized bound on LPT sequencing. In: Proceedings of the 1976 ACM SIGMETRICS Conference on Computer Performance Modeling Measurement and Evaluation, pp. 306–310. ACM (1976)

Alfarrarjeh, A., Emrich, T., Shahabi, C.: Scalable spatial crowdsourcing: a study of distributed algorithms. In: 2015 16th IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management, vol. 1, pp. 134–144. IEEE (2015)

Baneres, D., Caballé, S., Clarisó, R.: Towards a learning analytics support for intelligent tutoring systems on MOOC platforms. In: 2016 10th International Conference on Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS), pp. 103–110. IEEE (2016)

Gonzalez, T., Ibarra, O.H., Sahni, S.: Bounds for LPT schedules on uniform processors. SIAM J. Comput. 6 (1), 155–166 (1977)

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Mi, F., Yeung, D.Y.: Probabilistic graphical models for boosting cardinal and ordinal peer grading in MOOCs. In: AAAI, pp. 454–460 (2015)

Massabò, I., Paletta, G., Ruiz-Torres, A.J.: A note on longest processing time algorithms for the two uniform parallel machine makespan minimization problem. J. Sched. 19 (2), 207–211 (2016)

Gardner, K., Zbarsky, S., Harchol-Balter, M., et al.: The power of d choices for redundancy. ACM SIGMETRICS Perform. Eval. Rev. 44 (1), 409–410 (2016)

Article Google Scholar

Feier, M.C., Lemnaru, C., Potolea, R.: Solving NP-complete problems on the CUDA architecture using genetic algorithms. In: International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Computing, ISPDC 2011, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, pp. 278–281. DBLP, July 2011

Ul, Hassan U., Curry, E.: Efficient task assignment for spatial crowdsourcing. Expert Syst. Appl: Int. J. 58 (C), 36–56 (2016)

Jung, H.J., Lease, M.: Crowdsourced task routing via matrix factorization. Eprint Arxiv (2013)

Karger, D.R., Oh, S., Shah, D.: Budget-optimal crowdsourcing using low-rank matrix approximations. In: 2011 49th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton), pp. 284–291. IEEE (2011)

Yan, Y., Fung, G.M., Rosales, R., et al.: Active learning from crowds. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2011), pp. 1161–1168 (2011)

Tong, Y., She, J., Ding, B., et al.: Online minimum matching in real-time spatial data: experiments and analysis. Proc. VLDB Endow. (PVLDB) 9 (12), 1053–1064 (2016)

Tong, Y., She, J., Ding, B., et al.: Online mobile micro-task allocation in spatial crowdsourcing. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE 2016), pp. 49–60 (2016)

Tong, Y., She, J., Meng, R.: Bottleneck-aware arrangement over event-based social networks: the max-min approach. World Wide Web J. 19 (6), 1151–1177 (2016)

She, J., Tong, Y., Chen, L., et al.: Conflict-aware event-participant arrangement and its variant for online setting. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. (TKDE) 28 (9), 2281–2295 (2016)

She, J., Tong, Y., Chen, L., et al.: Conflict-aware event-participant arrangement. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE 2015), pp. 735–746 (2015)

Download references

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant from State Key Laboratory of Software Development Environment (Funding No. SKLSDE-2015ZX-03) and NSFC (Grant No. 61532004).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

State Key Laboratory of Software Development Environment, School of Computer Science, Beihang University, Beijing, China

Yong Han, Wenjun Wu & Yanjun Pu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yong Han .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology , Melbourne, Australia

Zhifeng Bao

Northwestern University , Evanston, Illinois, USA

Goce Trajcevski

University of New South Wales , Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Lijun Chang

The University of Queensland , Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Han, Y., Wu, W., Pu, Y. (2017). Task Assignment of Peer Grading in MOOCs. In: Bao, Z., Trajcevski, G., Chang, L., Hua, W. (eds) Database Systems for Advanced Applications. DASFAA 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10179. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55705-2_28

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55705-2_28

Published : 22 March 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-55704-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-55705-2

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The act of grading someone else's paper [a.k.a., student peer grading, peer assessment; peer evaluation; self-regulated learning] is a cooperative learning technique that refers to activities conducted either inside or outside of the classroom whereby students review, evaluate, and, in some cases, actually recommend grades on the quality of their peer's work. Peer grading is usually guided by a rubric developed by the instructor. A rubric is a performance-based assessment tool that uses specific criteria as a basis for evaluation. An effective rubric makes grading more clear, consistent, and equitable.

Newton, Fred B. and Steven C. Ender. Students Helping Students: A Guide for Peer Educators on College Campuses . 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010; Ramon-Casas, Marta et al. “The Different Impact of a Structured Peer-Assessment Task in Relation to University Undergraduates’ Initial Writing Skills.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (2019): 653-663.

Benefits of Peer Grading

Professors assign students to grade the work of their classmates because studies in educational research suggest that the act of grading someone else's paper increases positive learning outcomes for student s. Professors use peer grading as a way for students to practice recognizing quality research, with the hope that this will carry over to their own work, and as an aid for improving group performance or determining individual effort on team projects. Grading someone else's paper can also enhance learning outcomes by empowering students to take ownership over the selection of criteria used to evaluate the work of peers [the rubric]. Finally, professors may assign peer grading as a way to engage students in the act of seeing themselves as members of a community of researchers.

Other potential benefits include:

- Increasing the amount of feedback students receive about their work;

- Providing the instructor with an opportunity to verify student’s understanding, or lack of understanding, of key concepts or other course content;

- Encouraging students to be actively involved with, and to take responsibility for, their own learning;

- Providing an opportunity for reinforcing essential skills that can be used in professional life, including an ability to effectively assess the work of others and to become comfortable with having one's own work evaluated by others, and facilitating key skills, such as, self-reflection, time management, team skills building;

- Fostering a more in-depth and comprehensive process for understanding and analyzing a research problem through repetition and reinforcement of key criteria essential to learning a task;

- Providing motivation for improvement in course assignments and a more comprehensive perspective on learning; and,

- Can assist in deepening the student’s own perception of their learning style and ways of knowing [at a higher cognitive level, this is known as reflexivity, or, the process of understanding one's own contribution to the construction of meaning throughout the research process].

Boud, David, Ruth Chen, and Jane Sampson. "Peer Learning and Assessment." Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 24 (1999): 413-426; Huisman, Bart et al. “The Impact of Formative Peer Feedback on Higher Education Students’ Academic Writing: A Meta-Analysis.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (September 2019): 863-880; Dochy, Filip et al. "The Use of Self-, Peer, and Co-Assessment in Higher Education: A Review." Studies in Higher Education 24 (1999): 331-350; Falchikov, Nancy. Improving Assessment through Student Involvement: Practical Solutions for Aiding Learning in Higher and Further Education . New York: Routledge/Falmer, 2005; Huisman, Bart, Nadira Saab, Jan van Driel, and Paul van den Broek. “Peer Feedback on Academic Writing: Undergraduate Students’ Peer Feedback Role, Peer Feedback Perceptions and Essay Performance.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (2018): 955-968; Ryan, Mary Elizabeth, editor. Teaching Reflective Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Approach using Pedagogic Patterns . New York: Springer, 2014; Sadler, Philip M. and Eddie Good. "The Impact of Self- and Peer-Grading on Student Learning." Educational Assessment 11 (2006): 1-31;Topping, Keith J. “Peer Assessment.” Theory Into Practice 48 (2009): 20-27; Rachael Hains-Wesson. Peer and Self Assessment. Deakin Learning Futures, Deakin University, Australia.

How to Approach Peer Grading Assignments

I. Best Practices

Best practices in peer assessment vary depending on the type of assignment or project you are evaluating and the type of course you are taking. A good quality experience also depends on having a clear and accurate rubric that effectively presents the proper criteria and standards for the assessment. The process can be intimidating, but know that everyone probably feels the same way you do when first informed you will be evaluating the work of others--cautious and uncomfortable!

Given this, if not stated, the following questions should be answered by your professor before beginning:

- Exactly who [which students] will be evaluated and by whom?

- What does the evaluation include? What parts are not to be evaluated?

- At what point during a group project or the assignment will the evaluation be done?

- What learning outcomes are expected from this exercise?

- How will their peers’ evaluation affect everyone's grades?

- What form of feedback will you receive regarding how you evaluated your peers?

II. What to Consider

When informed that you will be assessing the work of others, consider the following:

- Carefully read the rubric given to you by the professor . If he/she hasn't distributed a rubric, be sure to clarify what guidelines or rules you are to follow and specifically what parts of the assignment or group project are to be evaluated. If you are asked to help develop a rubric, ask to see examples. The design and content of assessment rubrics can vary considerably and it is important to know what your professor is looking for.

- Consider how your assessment should be reported . Is it simply a rating [i.e., rate 1-5 the quality of work], are points given for each item graded [i.e., 0-20 points], are you expected to write a brief synopsis of your assessment, or is it any combination of these approaches? If you are asked to write an evaluation, be concise and avoid subjective or overly-broad modifiers. Whenever possible, cite specific examples of either good work or work you believe does not meet the standard outlined in the rubric.

- Clarify how you will receive feedback from your professor regarding how effectively you assessed the work of your peers . Take advantage of receiving this feedback to discuss how the rubric could be improved or whether the process of completing the assignment or group project was enhanced using peer grading methods.

III. General Evaluative Elements of a Rubric

In the social and behavioral sciences, the elements of a rubric used to evaluate a writing assignment depend upon the content and purpose of the assignment. Rubrics are often presented in print or online as a grid with evaluative statements about what constitutes an effective, somewhat effective, or ineffective element of the content.

Here are the general types of assessment that your professor may ask you to examine or that you may want to consider if you are asked to help develop the rubric.

Grammar and Usage

The writing is free of misspellings. Words are capitalized correctly. There is proper verb tense agreement. The sentences are punctuated correctly and there are no sentence fragments or run-on sentences. Acronyms are spelled out when first used. The paper is neat, legible, and presented in an appropriate format. If there are any non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, tables, pictures, etc.], assess whether they are labeled correctly and described in the text to help support an understanding the overall purpose of the paper.

Focus and Organization

The paper is structured logically. The research problem and supporting questions or hypotheses are clearly articulated and systematically addressed. Content is presented in an effective order that supports understanding of the main ideas or critical events. The narrative flow possesses overall unity and coherence and it is appropriately developed by means of description, example, illustration, or definition that effectively defines the scope of what is being investigated. Conclusions or recommended actions reflect astute connections to more than one perspective or point of view.

Elaboration and Style

The introduction engages your attention. Descriptions of ideas, concepts, events, and people are clearly related to the research problem. There is appropriate use of technical or specialized terminology required to make the content clear. Where needed, descriptions of cause and effect outcomes, compare and contrast, and classification and division of findings are effectively presented. Arguments, recommendations, best practices, or lessons learned are supported by the evidence gathered and presented. Limitations are acknowledged and described. Sources are selected from a variety of scholarly and creative sources that provide valid support for studying the problem. All sources are properly cited using a standard writing style.

Hodgsona, Yvonne, Robyn Benson, and Charlotte Brack. “Student Conceptions of Peer-Assisted Learning.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 39 (2015): 579-597; Getting Feedback. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Gueldenzoph, Lisa E. and Gary L. May. “Collaborative Peer Evaluation: Best Practices for Group Member Assessments.” Business and Professional Communication Quarterly 65 (March 2002): 9-20; Huisman, Bart et al. “Peer Feedback on College Students' Writing: Exploring the Relation between Students' Ability Match, Feedback Quality and Essay Performance.” Higher Education Research and Development 36 (2017): 1433-1447; Lladó, Anna Planas et al. “Student Perceptions of Peer Assessment: An Interdisciplinary Study.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (2014): 592-610; Froyd, Jeffrey. Peer Assessment and Peer Evaluation. The Foundation Coalition; Newton, Fred B. and Steven C. Ender. Students Helping Students: A Guide for Peer Educators on College Campuses . 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010; Liu, Ngar-Fun and David Carless. “Peer Feedback: The Learning Element of Peer Assessment.” Teaching in Higher Education 11 (2006): 279-290; Peer Assessment Resource Document . Montreal, Quebec: Teaching and Learning Services, McGill University, 2017; Peer Review. Psychology Writing Center. Department of Psychology. University of Washington; Revision: Peer Editing--Serving As a Reader. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Peer Review. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Suñola, Joan Josep et al. “Peer and Self-Assessment Applied to Oral Presentations from a Multidisciplinary Perspective.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (2016): 622-637; Writer's Choice: Grammar and Composition. Writing Assessment and Evaluation Rubrics . New York: Glencoe-McGraw-Hill, n.d.

Assessment Tip

Pay Close Attention to the Guiding Questions

Most forms of peer assessment include a set of open-ended questions that ask you to focus on aspects of the assignment that you can respond specifically to as an evaluator. These questions may ask you to summarize and critique parts of the paper or assess [or list, outline, or paraphrase] particular elements of the other student's paper as opposed to answering basic closed-ended questions that elicit only a yes/no response or making subjective judgements about the overall quality of the paper. Examples of guiding questions could include:

- What do you think is the research problem of the paper? Paraphrase it.

- What do you think is the strongest evidence for the author's position? Why?

- What are the key takeaways from the study?

Peer Assessment Resource Document . Montreal, Quebec: Teaching and Learning Services, McGill University, 2017; Iglesias Pérez, M. C., J. Vidal-Puga, and M. R. Pino Juste. "The Role of Self and Peer Assessment in Higher Education." Studies in Higher Education 47 (2020): 1-10.

- << Previous: Using Visual Aids

- Next: How to Manage Group Projects >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Designing Research Assignments: Assignment Guidelines

- Student Research Needs

- Assignment Guidelines

- Assignment Ideas

- Scaffolding Research Assignments

- BEAM Method

Where Students Struggle

Students struggle with starting assignments and defining a topic. When it comes to writing, the PIL study indicates that students:

- Use patchwork writing as a result of snipping from online sources

- Need to learn to focus on specific question rather than summarizing broad topics

- Need support in developing arguments

- Need support in how to integrate and cite sources

- Unintentional plagiarism from students other cultures

Assignment guidelines often do not offer students with guidance on conducting research ( Head, A. J. & Einsenberg, M. B. 2010 ). As a result, many student apply the same strategies they used in high school, and focus on length requirements rather than content.

Attribution

Portions of the content on this page were modified from Hunter College Libraries' Faculty Guide and Modesto Junior College Library & Learning Center's Designing Research Assignments guide .

Assignment Pitfalls

Research Topics: Under-Specification

When students are asked to choose any topic they are interested in, they often feel overwhelmed and uncertain, and have trouble developing a researchable topic. Instead of focusing on locating good sources and integrating them into their writing, students often get hung up on selecting and developing a topic.

Research Topics: Over-Specification

Asking students to research an extremely narrow topic will lead to frustration in locating useful resources or sometimes any resources at all. Check to see that library resources are available before selecting a topic.

Research Topics: A Better Option

Provide students with a pre-selected list of manageable, researchable topics related to the theme of the class. Have students select a topic from this list and work with them on developing good research questions at the outset. Have them come to library instruction sessions with their topic chosen and initial research questions in mind.

| "Don't use the internet." This is very confusing for students because most journals and magazines are available on the Internet and the library provides access to thousands of scholarly eBooks that are online. Students often express concern that they are not allowed to use academic journal articles found through the library's databases, because they are accessed through the internet. In addition, many substantive news and other content is either born digital or available both online and in print. |

Instead: Consider a less general prohibition against using material found on the open Internet, leaving the possibility of using library resources and subscription databases. Place greater emphasis on evaluating sources - no matter where they're found - to ensure they're credible. |

| "Don't use Wikipedia." Absent context, students may just use another Internet resource that's potentially even less useful. | Instead: Talk about the cycle of information and how different types of published information is produced and for what purposes. Explain that relying on Wikipedia for information is not academic research. Provide situations where Wikipedia be helpful to get students to shift from black/white good/bad thinking towards a more critical approach. Expect students to evaluate all of their sources using a process such as the test. |

| "Use only scholarly resources." Many students are unfamiliar with scholarly materials and don't understand what they are or how they should use them effectively. This guideline may also result in students trying to find definitions and background information in narrowly focused scholarly articles. | Instead: Discuss with the class why they should or should not use particular sources or types of sources in the context of an established framework such as the . Have them search for a variety of sources and show them to you to see if they're acceptable. Discuss the benefits and drawbacks of particular sources for answering various research questions. Consider the importance of context when deciding what types of sources you want students to use. Are students allowed to pick topics where more popular sources might be acceptable? How can students be encouraged to use and integrate a variety of credible sources? |

Assignment Design Tips

Clear assignment guidelines and examples of good student work can help to reduce student confusion and anxiety.

| Describe Approach | Synthesis, analysis, argument, evaluation? Include a research journal? Explain what you want students to do. |

|---|---|

| Provide Context | State how the assignment relates to course material. Consider both "big picture" and "information-finding" context. |

| Set Outcomes | Describe learning outcomes including those for information literacy and writing skill development. |

| Scaffold the Process | Split assignments into tasks and give feedback at each stage, focusing both on where the student did well and on areas for improvement. See the page for ideas. |

| Offer Research Strategies | Discuss research strategies including the specific search tools you want students to use, and appropriate web resources. Offer students suggestions for a good starting point. |

| Provide Sources Checklist | Specify useful types of resources. Provide clarity on differences between types of sources ("web" vs "online" resources). Recommend tools to identify new vocabulary and terminology. Discuss scholarly vs. popular sources and specify which and how many students should use. Let students know what types of sources you do want them to use. Is Wikipedia acceptable? |

| Set Citation Style | Name the citation style you want students to use and give a link to the corresponding library citation guide if available, or to another trusted guide. |

| Share Assessment | How is the assignment and the research process going to be assessed? Rubrics are helpful especially when they are reviewed when the assignment is given so students understand expectations and how they will be graded. Share examples of assignments that meet or exceed assignment expectations. |

| Describe Writing and Research Services | Let your students know how they can get additional help: |

- << Previous: Student Research Needs

- Next: Assignment Ideas >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://columbiacollege-ca.libguides.com/designing_assignments

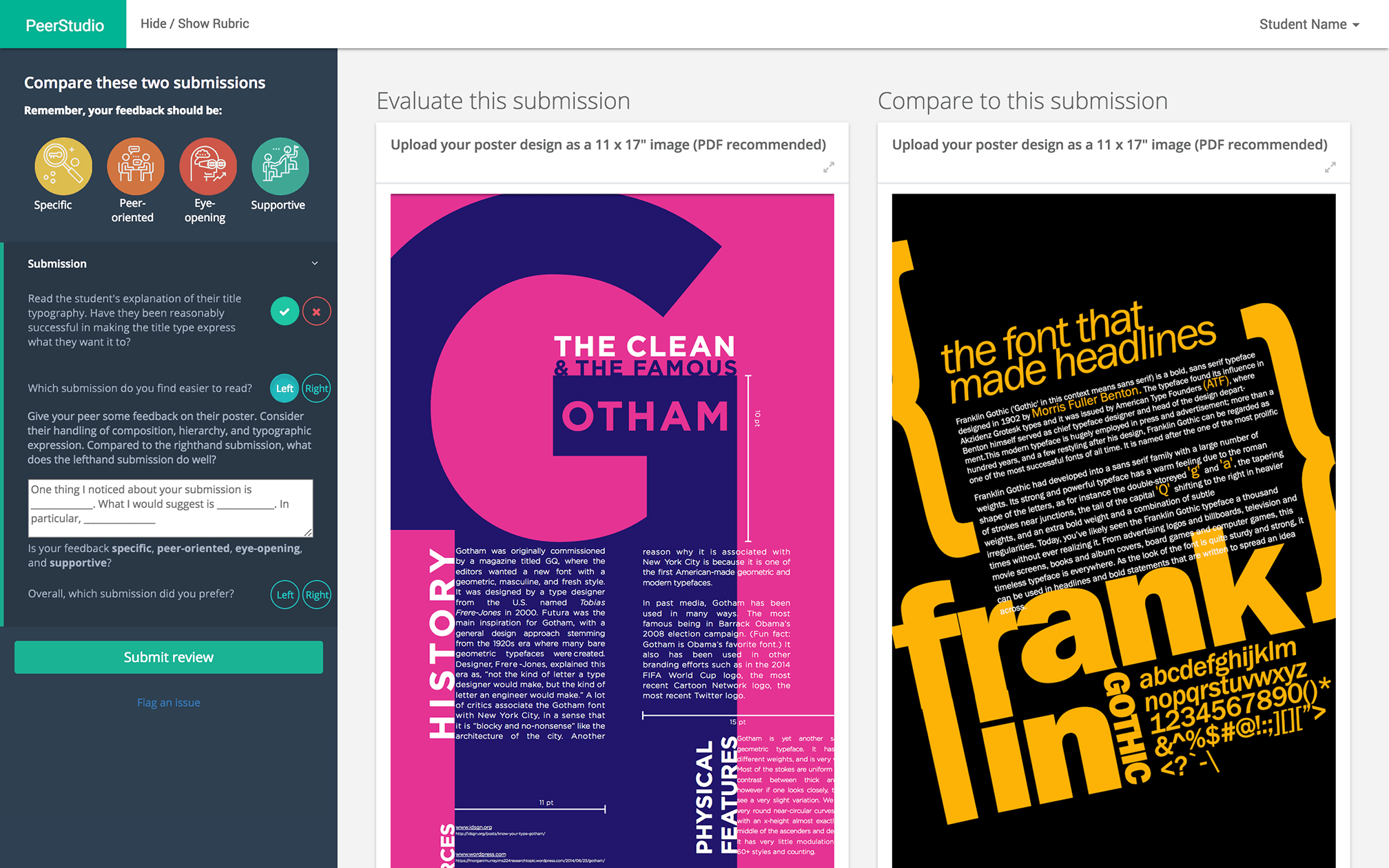

Better learning through peer feedback

PeerStudio makes peer feedback easier for instructors to manage, and students to learn from. It automates away the tedious aspects of peer reviewing, and learners use a comparison-based interface that helps them see work as instructors see it.

More than 39500 learners in dozens of universities use PeerStudio to learn design, writing, psychology, and more.

Used by happy instructors and students at

Research-based, comparative peer review

Comparative peer reviewing allows students to see what instructors see

PeerStudio leverages the theory of contrasting cases: comparing similar artifacts helps people see deeper, subtler distinctions between them. Think of wine tasting. It's much easier to notice the flavors when you compare one wine to another.

How PeerStudio uses comparisons

When students review in PeerStudio, they use a rubric that instructors specify. In addition to the rubric, PeerStudio finds a comparison submission within the pool of submissions from their classmates. While reviewing, students compare the target submission to this comparison submission using the provided rubric.

AI-backed, always improving

PeerStudio uses an artifical-intelligence backend to find just the right comparison for each learner and submission. (Among other features, we use learners' history of reviewing, and that of their classmates to identify optimal comparison submissions.) This backend is always learning, with accuracy improving even within the same assignment.

Guided reviewing

Learners often want to review well, but don't know how. We both help students learn how to review through interactive guides, and automatically detect poor reviewing.

How PeerStudio creates a better classroom

Inspire students, inspire students with peer work.

Most students in college today see so little of the amazing work their classmates do. PeerStudio creates an opportunity to see inspiring work and get more feedback on it. Instructors also tell us that their students enjoy writing, designing and completing assignments for a real audience, and how the benefits of peer reviewing spill over into clearer presentations and more insightful questions in class.

CLOUD-BASED

Work as your students do.

PeerStudio is cloud-based, so it is available from any computer, and allows students to view most common assignment materials without any additional software: PDFs, videos (including auto-embedding Youtube), formatted text (bold, italics, tables,...) are all supported. And because it's backed up every night, your students (and you!) never have to worry about losing work.

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT

Automated assignment of reviewers.

With traditional peer feedback tools, instructors have more, not less, work. You not only need to write the assignment and the rubric, but also assign students to review each other, make sure they do it on time, re-assign students who miss the deadline and so on.

PeerStudio automates it all. It uses an AI-backed to assign reviewers to submissions, automatically deals with balancing out reviewer load, and more. It even sends email reminders to students who haven't submitted their work or reviewed others.

REMAIN IN CONTROL

Grant deadline-extensions, keep an eye on review quality, and more.

PeerStudio automates the busywork, but you remain in control. On your dashboard, you can grant one-time exceptions, track who's late, even read individual reviews. Many instructors also use their dashboard to find examples of excellent work to show in class, or to recognize excellent peer feedback.

We can help you implement peer reviewing correctly and set up PeerStudio in your class. To get started, schedule a time to chat with us.

What our instructors say

PeerStudio has helped teach everything from design, English, music, and more.

Ready to get started?

We're also happy to help you think through introducing peer reviewing in your classroom, regardless of whether you use PeerStudio. Get in touch with us at [email protected] .

- Toggle navigation

Writing Across the Curriculum

Supporting writing in and across the disciplines at City Tech

Using Research on Peer Review to Strengthen Assignment Design

We at WAC talk a lot about peer review as a strategy for scaffolding assignments and getting students thinking about writing. And for good reason. Peer review supports the research and learning process where knowledge is developed in stages through combining exploration, production, and reflection. Beyond these more commonly discussed aspects, peer review used strategically has other benefits for course design, supporting students, and making class logistics easier for instructors. In this post, we’ll have a look at some of the recent research on peer review that speaks to its usefulness.

One major barrier to great final papers is last minute work. Scaffolding assignments aids in preventing this. How can peer review support this? A number of studies have found that courses tend to have peer review sessions scheduled around a week prior to the final assignment deadline (Baker 2016, 181). In these studies, students focused on copy editing feedback in the form of grammatical points and spelling errors (ibid). The real benefit of peer review, however, comes in the form of development of student ideas. Earlier review sessions allow students time to deal with the content of each other’s arguments. Feedback recipients also can take time to think about feedback and implement it more thoughtfully. Schedule peer review sessions earlier in the semester (and have this be part of their grade). In addition to increasing the chances of higher quality work, this also makes students less likely to plagiarize since they have more time to prepare and work with sources. Foregrounding the role of peer review by scheduling it early in the semester as a graded component will also socialize students into the importance of peer review. Rather than seeing it as a final requirement after the bulk of the work is done, it can be a significant component to building a paper.

Emphasizing peer review as crucial in the process can also happen through assistance in giving feedback. While students may have done peer reviews before, the truth is they rarely get explicit instruction in how to go about this. The thought of giving negative comments to fellow classmates can be intimidating. And, students often are not sure what to focus on for feedback. Models for feedback delivery can assist with this. For example, peer review can include a handout with prompts for students to use. Incorporating this as an official feedback form gives students guidelines for thinking about their classmates’ work. Prompts can include:

- This paper is about _______________________

- The biggest strength of this paper is __________________________________

- You should most focus on ________________________ in order to support your thesis.

- You might think about (xyz theory, writer, etc.)

- I’m not sure I understand (how z supports y, x is connected to z, etc.) Can you explain this more?

- I was really interested in your point about ______________________________

These types of prompts help students understand supportive ways to frame comments. This also helps to guide them in what to focus on. If you want to go further with this, you can use these or similar prompts when working with assigned course texts. Doing this as part of a class discussion helps students become active readers and think of what points in a piece of writing warrant feedback. Along these lines, there may be a positive correlation between deliberation (as opposed to argumentation) around a topic and learning outcomes (Klein 2016, 228). Argumentation puts students in a position to defend ideas whereas deliberation invites more open-ended discussion. To this end, getting students to think of peer review as active engagement with a text’s ideas (as opposed to criticism) can foster deliberation. The prompts above can help with this.

What sort of feedback has results? How can we give our students specific models so that peers have usable feedback? A study of peer review in an ESL class offers clues. In a 2017 study of digital peer review sessions for ESL students, researchers classified types of feedback into a number of categories describing content and qualities (Leijen). They found that two types of feedback were most likely to lead to revisions: alteration and recurring (ibid, 44). Feedback classified as alteration offered specific guidance on points in the text. For example: “Evidence A doesn’t seem to connect to your main point. Maybe add an explanatory paragraph to clarify.” This is in contrast to more global feedback such as “Evidence doesn’t support main idea well.” Recurring feedback was the same advice given by multiple reviewers. This study provides valuable information for helping students design feedback for peers. Giving them examples of specific and direct feedback and having multiple reviewers can make feedback more productive for students.

All of this we have discussed so far relates to the inherently social nature of writing. Klein (2016) notes that more recent theories of writing characterize it as created within various kinds of contexts and by multiple contributors (329-330). Indeed, writing is never truly a solitary affair. Feedback, ideas from the world around us, course lectures and readings, and many other things all come together to create written work. Peer review is a way to build on the multi-voiced nature of writing to help students succeed.

Baker, Kimberly M. 2016. “Peer Review as a Strategy for Improving Students’ Writing Process.” Active Learning in Higher Education 17(3): 179-192.

Klein, Perry D. 2016. “Trends in Research on Writing as a Learning Activity.” Journal of Writing Research 7(3): 311-350.

Leijen, D.A.J. 2017. “A Novel Approach to Examine the Impact of Web-based Peer Review on the Revisions of L2 Writers.” Computers and Composition 43: 35-54.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The OpenLab at City Tech: A place to learn, work, and share

The OpenLab is an open-source, digital platform designed to support teaching and learning at City Tech (New York City College of Technology), and to promote student and faculty engagement in the intellectual and social life of the college community.

New York City College of Technology | City University of New York

Accessibility

Our goal is to make the OpenLab accessible for all users.

Learn more about accessibility on the OpenLab

Creative Commons

- - Attribution

- - NonCommercial

- - ShareAlike

© New York City College of Technology | City University of New York

International Journal of Higher Education

Journal Metrics

Citations (May 2023): 17235

h-index (May 2023): 60

i10-index (May 2023): 319

h5-index (May 2023): 33

h5-median (May 2023): 46

- Other Journals

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

- Announcements

- Recruitment

- Editorial Board

- Ethical Guidelines

- GOOGLE SCHOLAR CITATIONS

- Publication Policies

Effective Use of Peer Assessment in a Graduate Level Writing Assignment: A Case Study

At the undergraduate level, considerable evidence exists to support the use of peer assessment, but there is less research at the graduate level. In the present study, we investigated student perception of the peer assessment experience and the ability of graduate students to provide feedback that is comparable to the instructor and that is consistent between assessors on a written assignment. We observed that students were very supportive of the activity, and that negative concerns related to inconsistent peer evaluations were not supported by the quantitative findings, since the average grade of the student reviews was not significantly different from the instructor grade, although student reviewer reliability was not high. Students showed a significant grade improvement following revision subsequent to peer assessment, with lower graded papers showing the greatest improvement; greater grade change was also associated with an increased number of comments for which a clear revision activity could be taken. Design of the graduate peer assessment activity included several characteristics that have been previously shown to support positive findings, such as training, use of a clear assignment rubric, promotion of a trusting environment, use of peer and instructor grading, provision of directive and non-directive feedback, recruitment of positive comments, and use of more than one peer assessor. This study therefore builds on previous work and suggests that use of a carefully designed peer assessment activity, which includes clear direction regarding actionable comments, may provide students with useful feedback that improves their performance on a writing assignment.

- There are currently no refbacks.

International Journal of Higher Education ISSN 1927-6044 (Print) ISSN 1927-6052 (Online) Email: [email protected]

Copyright © Sciedu Press

To make sure that you can receive messages from us, please add the 'Sciedupress.com' domain to your e-mail 'safe list'. If you do not receive e-mail in your 'inbox', check your 'bulk mail' or 'junk mail' folders.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Coursera Quantitative Methods Assignments (2016). Contribute to rkiyengar/coursera-quant-methods development by creating an account on GitHub.

PA assignments can be graded in different ways: The instructor grades students' feedback, either for quality or simply for completion. Peers grade each other's work. A combination of instructor and peer grading is used. Peers submit a grade which the instructor can override.

A previous study comparing student and faculty scores for 3 peer-graded assignments at the college resulted in the students assigning significantly lower scores than faculty members to student peers, which was inconsistent with other research. 10 One goal of using peer grading was to replace the need for traditional faculty SOAP note grading ...

Exercise 1: Improve an assignment. Brainstorm in your breakout group choose one or more way to improve the assignment: Identify the hidden skills or knowledge explicit by creating learning outcomes or objectives. Devise an activity that gives students practice with required skills. Clarify the instructions.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the peer-grading process utilized for three SOAP note assignments for pharmacy students enrolled in a skills-based course sequence entitled Professional ...

1. Introduction. After years of extensive research within higher education, peer assessment has established itself as a reliable and efficient practice in rating and providing formative and summative feedback for open-ended assignments Huisman et al. (2018) Zong et al. (2021). Opposed to close-ended assignments that commonly have a single correct answer, open-ended assignments may have ...

In this section, we present the overview of the entire peer grading framework and introduce the design of grading task assignment in detail. Figure 2 illustrates the basic framework of our peer grading process. It consists of three major components: the student performance evaluation model, the peer grading task allocator and the score aggregation model.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

Peer assessment is understood to be an arrangement with students assessing the quality of their. fellow students' writings and giving feedback to each other. This multiple-case study of seven ...

The peer reviews and reflections were graded using a rubric which included providing peer feedback on substantive writing issues (for example, plagiarism, missing important information, incorrectly paraphrasing information, not following assignment instruction) and reflections that were directly connected to the theory, article content, and ...

Describe learning outcomes including those for information literacy and writing skill development. Scaffold the Process. Split assignments into tasks and give feedback at each stage, focusing both on where the student did well and on areas for improvement. See the Scaffolding Research Assignments page for ideas.

forum in myCourses for peer feedback. The purpose of the peer feedback assignment is for you to reflect on and make informed decisions about how to build and support your own arguments through critical assessment of the quality of supp. rt peers provide for their arguments.The instructor has plac.

Moreover, Todd and Hudson (2007), while studying the efficacy of a peer evaluation assignment in a public relations course, reported This peer-evaluation assignment encouraged students to think ...

1. Introduction. In higher education settings, there are increasing calls to shift away from traditional summative assessment practices, such end of term written tests, to explore methods of assessing learning in alternative ways (Darling-Hammond, 2014).A review of assessment practices by Pereira et al. (2016) concluded that "research over the period indicates benefits for students' learning ...

PeerStudio is an online tool that makes it easier to use peer review and grading in the classroom, and helps students learn better by reviewing each others' essays, assignments, and design projects. Research-based, and classroom proven. ... More than 39500 learners in dozens of universities use PeerStudio to learn design, writing, psychology ...

Peer review supports the research and learning process where knowledge is developed in stages through combining exploration, production, and reflection. Beyond these more commonly discussed aspects, peer review used strategically has other benefits for course design, supporting students, and making class logistics easier for instructors.

Design of the graduate peer assessment activity included several characteristics that have been previously shown to support positive findings, such as training, use of a clear assignment rubric, promotion of a trusting environment, use of peer and instructor grading, provision of directive and non-directive feedback, recruitment of positive ...

Also, face-to-face peer editing improves the quality of revised. written work (Crossman and Kite, 2012). What these studies indicate is that peer review improves written communication, both strengths and weaknesses of writing produce. positive effects, and revised work improves; therefore, so did students' writing.

The potential of web-based peer assessment platforms to aid in instruction and learning has been well documented in literature. Evidence proposed that the use of web-based peer assessment is ...

The main goals of the peer review should be: i) to improve the oral and written communication skills of the students and ii) to increase the probability of the projects successful implementation. It should be a collaborative process between the instructor, the peer reviewers and the project team. If the project team believes the review will ...

everything you need to complete coursera assignments is covered in this video.. i hope you all like it.!Also check out this : https://youtu.be/JnG6W7S7yU4?si...