CRITICAL THINKING AND THE NURSING PROCESS

Oct 09, 2014

600 likes | 1.13k Views

CRITICAL THINKING AND THE NURSING PROCESS. NRS 101 Unit III Session 3. Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment. How do we make decisions? How do nurses make decisions about patient care? What do we rely on to help us in decision making?. Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment.

Share Presentation

- critical thinking

- decision making

- step process

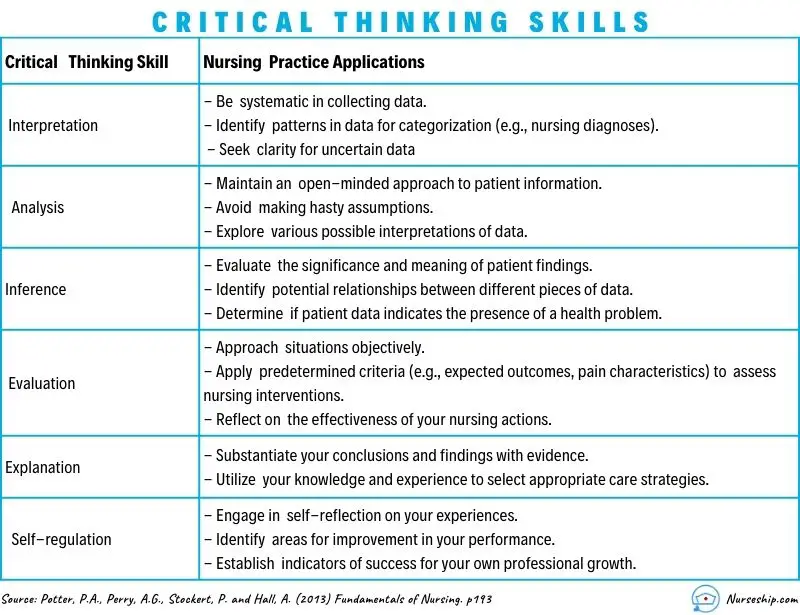

- critical thinking skills

- clinical decision making skills

Presentation Transcript

CRITICAL THINKING AND THE NURSING PROCESS NRS 101 Unit III Session 3

Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment • How do we make decisions? • How do nurses make decisions about patient care? • What do we rely on to help us in decision making?

Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment • Not a linear step by step process • Process acquired through hard work, commitment, and an active curiosity toward learning • Decision making is the skill that separates the professional nurse from technical or ancillary staff

Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment • Good problem solving skills • Not always a clear textbook answer • Nurse must learn to question, look at alternatives

How do nurse's accomplish this? • Learns to be flexible in clinical decision making • Reflect on past experiences and previous knowledge • Listen to others point of view • Identify the nature of the problem • Select the best solution for improving client’s health

Definition of Critical Thinking • Cognitive process during which an individual reviews data and considers potential explanations and outcomes before forming an opinion or making a decision • “Critical thinking in nursing practice is a discipline specific, reflective reasoning process that guides the nurse in generating, implementing, and evaluating approaches for dealing with client care and professional concerns.” NLN 2000

Critical Thinking in Nursing • Purposeful, outcome-directed • Essential to safe, competent, skillful nursing practice • Based on principles of nursing process and the scientific method • Requires specific knowledge, skills, and experience • New nurses must question

Critical Thinking in Nursing • Guided by professional standards and ethic codes • Requires strategies that maximize potential and compensate for problems • Constantly reevaluating, self-correcting, and striving to improve

Formula for Critical Thinking • Start Thinking • Why Ask Why • Ask the Right Questions • Are you an expert?

Aspects of Critical Thinking • Reflection • Language • Intuition

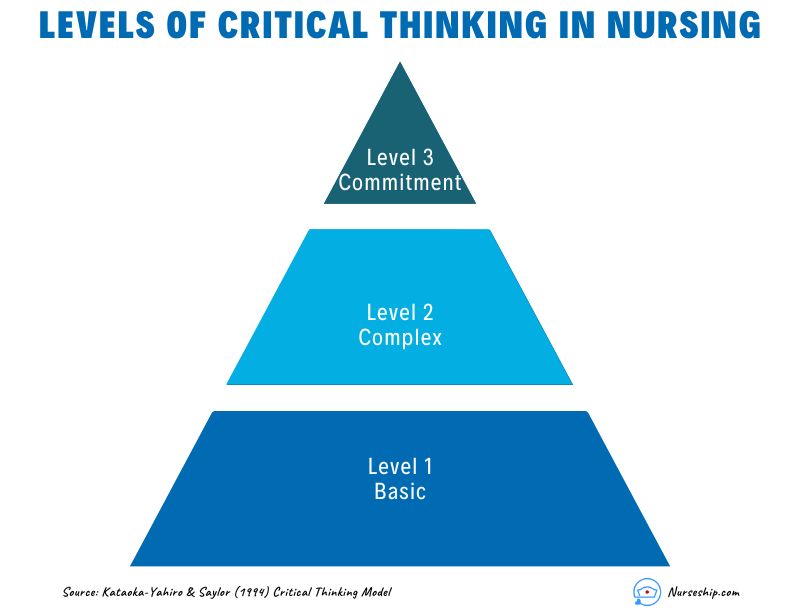

Levels of Critical Thinking • Basic • Complex • Commitment

Critical Thinking Competencies • Scientific method • Problem Solving • Decision Making • Diagnostic Reasoning and Inferences • Clinical Decision Making • Nursing Process

Developing Critical Thinking Attitudes/Skills Not easy Not “either or” Self-assessment Tolerating dissonance and ambiguity Seeking situations where good thinking practiced Creating environments that support critical thinking

Nursing Process • Systematic approach that is used by all nurses to gather data, critically examine and analyze the data, identify client responses, design outcomes, take appropriate action, then evaluate the effectiveness of action • Involves the use of critical thinking skills • Common language for nurses to “think through” clinical problems

Nursing Process

Thinking and Learning • Lifelong process • Flexible, open process • Learn to think and to ANTICIPATE • What, why, how questions • Look beyond the obvious • Reflect on past experience • New knowledge challenges the traditional way

Components Of Critical Thinking • Scientific Knowledge Base • Experience • Competencies • Attitudes • Standards

Attitudes That Foster Critical Thinking • Independence • Fair-mindedness • Insight into ethnocentricity • Intellectual humility • Intellectual courage to challenge status quo • Integrity • Preserverance • Confidence • Curiosity

Professional Standards • Ethical criteria for Nursing judgment- Code of Ethics • Criteria for evaluation- Standards of care • Standards of professional responsibility that nurses strive to achieve are cited in Nurse Practice Acts, TJC guidelines, institutional policy and procedure, ANA Standards of Nursing Practice

Critical Thinking Synthesis • Reasoning process by which individuals reflect on and analyze their own thoughts, actions, & decisions and those of others • Not a step by step process

Nursing Process • Traditional critical thinking competency • 5 Step circular, ongoing process • Continuous until clients health is improved, restored or maintained • Must involve assessment and changes in condition

When using the Nursing Process • Identify health care needs • Determine Priorities • Establish goals & expected outcomes • Provide appropriate interventions • Evaluate effectiveness

Nursing Process • Assessment • Diagnosis • Planning • Implementation • Evaluation

Assessment • Systemically collects, verifies, analyzes and communicates data • Two step process- Collection and Verification of data & Analysis of data • Establishes a data base about client needs, health problems, responses, related experiences, health practices, values. lifestyle, & expectations

Critical Thinking and Assessment Process • Brings knowledge from biological, physical, & social sciences as basis for the nurse to ask relevant questions. Need knowledge of communication skills • Prior clinical experience contributes to assessment skills • Apply Standards of Practice • Personal Attitudes

Assessment Data • Subjective Data • Objective Data • Sources of Data • Methods of Data Collection-Interview • Interview initiates nurse-client relationship • Use open-ended questions • Nursing health history

Nursing Diagnosis • Statement that describes the client’s actual or potential response to a health problem • Focuses on client-centered problems • First introduced in the 1950’s • NANDA established in 1982 • Step of the nursing process that allows nurse to individualize care

Planning for Nursing Care • Client-centered goals and expected outcomes are established • Priorities are set relating to unmet needs • Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a useful method for setting priorities • Priorities are classifies as high, intermediate, or low

Purpose of Goals and Outcomes • Provides direction for individualized nursing interventions • Sets standards of determining the effectiveness of interventions • Indicates anticipated client behavior or response to nursing care • End point of nursing care

Goals of Care • Goal: Guideposts to the selection of nursing interventions and criteria in the evaluation of interventions • What you want to achieve with your patient and in what time frame • Short term vs. Long term • Outcome Of Care: What was actually achieved, was goal met or not met

Nursing Interventions • Interventions are selected after goals and outcomes are determined • Actions designed to assist client in moving from the present level of health to that which is described in the goal and measured with outcome criteria • Utilizes critical thinking by applying attitudes and standards and synthesizing data

Types of Interventions • Nurse-Initiated • Physician-Initiated • Collaborative Interventions

Selection Of Intervention • Using clinical decision making skills, the nurse deliberates 6 factors: • Diagnosis, expected outcomes, research base, feasibility, acceptability to client, competency of nurse

Nursing Care Plans • Written guidelines for client care • Organized so nurse can quickly identify nursing actions to be delivered • Coordinates resources for care • Enhances the continuity of care • Organizes information for change of shift report

Nursing Care Plans vs Concept Maps NCP Concept/Mind Map

Implementation of Nursing Interventions • Describes a category of nursing behaviors in which the actions necessary for achieving the goals and outcomes are initiated and completed • Action taken by nurse

Types of Nursing Interventions • Standing Orders: Document containing orders for the use of routine therapies, monitoring guidelines, and/or diagnostic procedure for specific condition • Protocols: Written plan specifying the procedures to be followed during care of a client with a select clinical condition or situation (Pneumonia, MI, CVA)

Implementation Process involves: • Reassessing the client • Reviewing and revising the existing care plan • Organizing resources and care delivery (equipment, personnel, environment)

Evaluation • Step of the nursing process that measures the client’s response to nursing actions and the client’s progress toward achieving goals • Data collected on an on-going basis • Supports the basis of the usefulness and effectiveness of nursing practice • Involves measurement of Quality of Care

Evaluation of Goal Achievement • Measures and Sources: Assessment skills and techniques • As goals are evaluated, adjustments of the care plan are made • If the goal was met, that part of the care plan is discontinued • Redefines priorities

- More by User

Critical Thinking in Nursing

Critical Thinking. Problem Solving. Clinical Reasoning. Priority Setting. Decision Making. Critical Thinking in Nursing. Lipe, S. K. & Beasley, S., (2004). Critical Thinking in Nursing: A cognitive skills workbook. Lippincott. Philadelphia, PA. OBJECTIVES.

789 views • 25 slides

Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment

Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment. NPN 105 Joyce Smith RN, BSN. What is Critical Thinking?. It is something you do every day It is a life skill you learned as you developed into adulthood It is not a difficult task It is the way you make decisions in your daily life

2.15k views • 12 slides

Critical Thinking in the Nursing Process

Critical Thinking in the Nursing Process. The Nursing Care Plan. Nursing Process. Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention/Rationale Evaluation. Assessment. Subjective Data Objective Data. Nursing Diagnosis. Data Analysis Problem Identification Label-NANDA. PES. P- Problem

870 views • 9 slides

Critical Thinking in Engineering Process

Enhancing Thinking Skills in Science Context Lesson 6. Critical Thinking in Engineering Process. Introduction to the different types of bridges. beam bridge suspension bridge arch bridge . Why are there different types of bridges? .

751 views • 39 slides

Chapter 8: Critical Thinking, the Nursing Process, and Clinical Judgment

Chapter 8: Critical Thinking, the Nursing Process, and Clinical Judgment. Bonnie M. Wivell, MS, RN, CNS. Defining Critical Thinking. Facione and others (1990) Purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference

2.13k views • 30 slides

Critical Thinking in Nursing. Sheryl Abelew MSN RN. Chapter 4. Priority Setting. Priority Setting. Important step in the critical thinking process Includes effective time management

2.11k views • 64 slides

195 views • 0 slides

CRITICAL THINKING in Nursing Practice: chapter 14

CRITICAL THINKING in Nursing Practice: chapter 14. “…active, organized, cognitive process used to carefully examine one’s thinking and the thinking of others.” Involves use of MIND Form conclusions Make decisions Draw inferences reflect. BEGIN WITH:. Questions:

399 views • 12 slides

Critical Thinking And The Nursing Process

Critical Thinking And The Nursing Process. Dr. Belal Hijji, RN, PhD December 5, 2010. Learning Outcomes. At the end of this lecture, students will be able to:

474 views • 16 slides

The Critical Thinking Process

The Critical Thinking Process. Analysis : Breaking a subject down into its parts in order to better understand that subject. i.e. Asking the following questions when reading an essay: Who is the narrator? What is the topic of the essay? Where does it take place? When does it take place?

361 views • 6 slides

Critical Thinking in Nursing Education

Critical Thinking in Nursing Education. CT in Introductory Courses. Defined in HEAL 1000 CT used in Dosage Calculations Course Students are taught how to begin thinking using the Nursing Process. Critical thinking and the Nursing Process Assessment Diagnosis Planning Implementation

376 views • 7 slides

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice. CRITICAL THINKING. Critical thinking is an active, organized, cognitive process used to carefully examine one’s thinking and the thinking of others (Pg. 216) Recognize that an issue exists Analyzing information about the issue Evaluating information

1.06k views • 62 slides

Critical Thinking in The Nursing Process

Critical Thinking in The Nursing Process. Separating the Professional from the Technical. Aspects of Critical Thinking. “the active, organized, cognitive process used to examine one’s own thinking and the thinking of others”

1.34k views • 41 slides

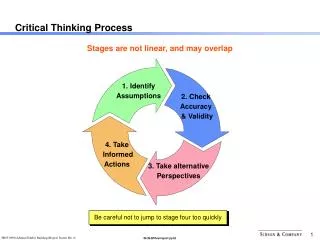

Critical Thinking Process

Critical Thinking Process. Stages are not linear, and may overlap. 1. Identify Assumptions. 2. Check Accuracy & Validity. 4. Take Informed Actions. 3. Take alternative Perspectives. Be careful not to jump to stage four too quickly. Types of Assumptions. Paradigmatic.

191 views • 3 slides

Critical Thinking and Nursing Practice

Chapter 10 Dr. Wajed Hatamleh. Critical Thinking and Nursing Practice. Learning Outcomes. Describe the significance of developing critical-thinking abilities in order to practice safe, effective, and professional nursing care.

318 views • 23 slides

CRITICAL THINKING AND THE NURSING PROCESS. Entry Into Professional Nursing NRS 101. Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment. How do we make decisions? How do nurses make decisions about patient care? What do we rely on to help us in decision making?. Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment.

537 views • 47 slides

Critical thinking about critical thinking

Critical thinking about critical thinking. Paula Owens and John Hopkin. Workshop description Based on two practical activities, this workshop will explore what critical thinking means in the context of geography, apply it to some examples and consider how to apply it in the classroom

980 views • 28 slides

CRITICAL THINKING AND THE NURSING PROCESS. Summer 2009 Donna M. Penn RN, MSN, CNE. Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment. How do we make decisions? How do nurses make decisions about patient care? What do we rely on to help us in decision making?. Critical Thinking and Nursing Judgment.

582 views • 51 slides

CRITICAL THINKING in Nursing Practice:

CRITICAL THINKING in Nursing Practice:. “…active, organized, cognitive process used to carefully examine one’s thinking and the thinking of others.” Involves use of MIND Form conclusions Make decisions Draw inferences reflect. Critical Thinking and Nursing.

504 views • 33 slides

CRITICAL THINKING in Nursing Practice

CRITICAL THINKING in Nursing Practice. CRITICAL THINKING in Nursing Practice. “…active, organized, cognitive process used to carefully examine one’s thinking and the thinking of others.” Involves use of MIND Form conclusions Make decisions Draw inferences reflect.

756 views • 59 slides

ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

Critical Thinking in Nursing: Tips to Develop the Skill

4 min read • February, 09 2024

Critical thinking in nursing helps caregivers make decisions that lead to optimal patient care. In school, educators and clinical instructors introduced you to critical-thinking examples in nursing. These educators encouraged using learning tools for assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Nurturing these invaluable skills continues once you begin practicing. Critical thinking is essential to providing quality patient care and should continue to grow throughout your nursing career until it becomes second nature.

What Is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing involves identifying a problem, determining the best solution, and implementing an effective method to resolve the issue using clinical decision-making skills.

Reflection comes next. Carefully consider whether your actions led to the right solution or if there may have been a better course of action.

Remember, there's no one-size-fits-all treatment method — you must determine what's best for each patient.

How Is Critical Thinking Important for Nurses?

As a patient's primary contact, a nurse is typically the first to notice changes in their status. One example of critical thinking in nursing is interpreting these changes with an open mind. Make impartial decisions based on evidence rather than opinions. By applying critical-thinking skills to anticipate and understand your patients' needs, you can positively impact their quality of care and outcomes.

Elements of Critical Thinking in Nursing

To assess situations and make informed decisions, nurses must integrate these specific elements into their practice:

- Clinical judgment. Prioritize a patient's care needs and make adjustments as changes occur. Gather the necessary information and determine what nursing intervention is needed. Keep in mind that there may be multiple options. Use your critical-thinking skills to interpret and understand the importance of test results and the patient’s clinical presentation, including their vital signs. Then prioritize interventions and anticipate potential complications.

- Patient safety. Recognize deviations from the norm and take action to prevent harm to the patient. Suppose you don't think a change in a patient's medication is appropriate for their treatment. Before giving the medication, question the physician's rationale for the modification to avoid a potential error.

- Communication and collaboration. Ask relevant questions and actively listen to others while avoiding judgment. Promoting a collaborative environment may lead to improved patient outcomes and interdisciplinary communication.

- Problem-solving skills. Practicing your problem-solving skills can improve your critical-thinking skills. Analyze the problem, consider alternate solutions, and implement the most appropriate one. Besides assessing patient conditions, you can apply these skills to other challenges, such as staffing issues .

How to Develop and Apply Critical-Thinking Skills in Nursing

Critical-thinking skills develop as you gain experience and advance in your career. The ability to predict and respond to nursing challenges increases as you expand your knowledge and encounter real-life patient care scenarios outside of what you learned from a textbook.

Here are five ways to nurture your critical-thinking skills:

- Be a lifelong learner. Continuous learning through educational courses and professional development lets you stay current with evidence-based practice . That knowledge helps you make informed decisions in stressful moments.

- Practice reflection. Allow time each day to reflect on successes and areas for improvement. This self-awareness can help identify your strengths, weaknesses, and personal biases to guide your decision-making.

- Open your mind. Don't assume you're right. Ask for opinions and consider the viewpoints of other nurses, mentors , and interdisciplinary team members.

- Use critical-thinking tools. Structure your thinking by incorporating nursing process steps or a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) to organize information, evaluate options, and identify underlying issues.

- Be curious. Challenge assumptions by asking questions to ensure current care methods are valid, relevant, and supported by evidence-based practice .

Critical thinking in nursing is invaluable for safe, effective, patient-centered care. You can successfully navigate challenges in the ever-changing health care environment by continually developing and applying these skills.

Images sourced from Getty Images

Related Resources

Item(s) added to cart

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Critical thinking, the nursing process, and clinical judgment

CHAPTER 8 Critical thinking, the nursing process, and clinical judgment Learning outcomes After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Define critical thinking. • Describe the importance of critical thinking in nursing. • Contrast the characteristics of “novice thinking” with those of “expert thinking.” • Explain the purpose and phases of the nursing process. • Differentiate between nursing orders and medical orders. • Explain the differences between independent, interdependent, and dependent nursing actions. • Describe evaluation and its importance in the nursing process. • Define clinical judgment in nursing practice and explain how it is developed. • Devise a personal plan to use in developing sound clinical judgment. To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Black/professional . Almost every encounter a nurse has with a patient is an opportunity for the nurse to assist the patient to a higher level of wellness or comfort. A nurse’s ability to think critically about a patient’s particular needs and how best to meet them will determine the extent to which a patient benefits from the nurse’s care. A nurse’s ability to use a reliable cognitive approach is crucial in determining a patient’s priorities for care and in making sound clinical decisions in addressing those priorities. This chapter explores several important and interdependent aspects of thinking and decision making in nursing: critical thinking, the nursing process, and clinical judgment. Chapter opening photo from istockphoto.com . Defining critical thinking Defining “critical thinking” is a complex task that requires an understanding of how people think through problems. Educators and philosophers struggled with definitions of critical thinking for several decades. Two decades ago, the American Philosophical Association published an expert consensus statement ( Box 8-1 ) describing critical thinking and attributes of the ideal critical thinker. This expert statement, still widely used, was the culmination of 3 years of work by Facione and others who synthesized the work of numerous persons who had defined critical thinking. More recently, Facione (2006) noted that giving a definition of critical thinking that can be memorized by the learner is actually antithetical to critical thinking! This means that the very definition of critical thinking does not lend itself to simplistic thinking and memorization. BOX 8-1 EXPERT CONSENSUS STATEMENT REGARDING CRITICAL THINKING AND THE IDEAL CRITICAL THINKER We understand critical thinking (CT) to be purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. CT is essential as a tool of inquiry. As such, CT is a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one’s personal and civic life. While not synonymous with good thinking, CT is a pervasive and self-rectifying human phenomenon. The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, open-minded, flexible, fair-minded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results that are as precise as the subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit. Thus educating good critical thinkers means working toward this ideal. It combines developing CT skills with nurturing those dispositions that consistently yield useful insights and that are the basis of a rational and democratic society. From American Philosophical Association : Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction, The Delphi report: Research findings and recommendations prepared for the committee on pre-college philosophy, 1990, ERIC Document Reproduction Services, pp. 315–423. The Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework is grounded in this definition of critical thinking: “Critical thinking is that mode of thinking—about any subject, content, or problem—in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them.” Paul and Elder, 2012 Paul and Elder (2012) go on to describe a “well-cultivated critical thinker” as one who does the following: • Raises questions and problems and formulates them clearly and precisely • Gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas for interpretation • Arrives at conclusions and solutions that are well-reasoned and tests them against relevant standards • Is open-minded and recognizes alternative ways of seeing problems, and has the ability to assess the assumptions, implications, and consequences of alternative views of problems • Communicates effectively with others as solutions to complex problems are formulated We live in a “new knowledge economy” driven by information and technology that changes quickly. Analyzing and integrating information across an increasing number of sources of knowledge requires that you have flexible intellectual skills. Being a good critical thinker makes you more adaptable in this new economy of knowledge ( Lau and Chan, 2012). An excellent website on critical thinking can be found at http://philosophy.hku.hk/think/ (OpenCourseWare on critical thinking, logic, and creativity). So what does this have to do with nursing? The answer is very simple: excellent critical thinking skills are required for you to make good clinical judgments. You will be responsible and accountable for your own decisions as a professional nurse. The development of critical thinking skills is crucial as you provide nursing care for patients with increasingly complex conditions. Critical thinking skills provide you with a powerful means of determining patient needs, interpreting physician orders, and intervening appropriately. Box 8-2 presents an example of the importance of critical thinking in the provision of safe care. BOX 8-2 USING CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS TO IMPROVE A PATIENT’S CARE Ms. George has recently undergone bariatric surgery after many attempts to lose weight over the years have failed. She is to be discharged home on postoperative day 2, as per the usual protocol. Although she describes herself as “not feeling well at all,” the physician writes the order for discharge and you, as the nurse who does postoperative discharge planning for the surgery practice, prepare Ms. George to go home with her new dietary guidelines and encouragement for her successful weight loss. You note that Ms. George does not seem as comfortable or pleased with her surgery as most patients with whom you have worked in the past. Ms. George has to wait 3 hours for her husband to drive her home, and you note that she continues to lie on the bed passively, and her lethargy is increasing. You take her vital signs and note that her temperature is 37.8° C and her pulse is 115. You listen to her chest and note that it is difficult to appreciate breath sounds due to the patient’s body habitus. Ms. George points to an area just below her left breast where she notes pain with inspiration. You call her physician to report your findings; she responds that Ms. George’s pain is “not unusual” with her type of bariatric surgery and that her slightly increased temperature is “most likely” related to her being somewhat dehydrated. She instructs you to have Ms. George force fluids to the extent that she can tolerate it, and to take mild pain medication for postoperative pain. You ask her to consider delaying her discharge home, but she refuses. You give Ms. George acetaminophen as ordered, but her pain on inspiration continues. Her temperature remains at 37.8° C, and her pulse is 120. You measure her O 2 saturation with a pulse oximeter, and it is 91%. Her respirations are 26 and somewhat shallow. Her surgeon does not respond to your page, so you call the nursing supervisor, explaining to him that you are concerned with Ms. George’s impending discharge. Although you are wary of the surgeon’s reaction, you call the hospitalist (a physician who sees inpatients in the absence of their attending physician), who orders a chest x-ray study. Ms. George has evidence of a consolidation in her left lower lobe, which turns out to be a pulmonary abscess. She is treated on intravenous antibiotics for 5 days, and the abscess eventually has to be aspirated and drained. Your critical thinking skills and willingness to advocate for your patient prevented an even worse postoperative course. You recognized that Ms. George’s lethargy was unusual, and the location and timing of her pain was of concern. You also realized that although her temperature appeared to be stable, she had been given a pain medicine (acetaminophen) that also reduces fever, so in fact, a temperature increase may have been masked by the antipyretic properties of the acetaminophen. You demonstrated excellent clinical judgment in measuring her O 2 saturation. Furthermore, you sought support through the nursing “chain of command” when you engaged the nursing supervisor, who supported you in contacting the hospitalist. The specific, detailed information that you were able to provide the hospitalist allowed him to follow a logical diagnostic path, determining that Ms. George did indeed have a significant postoperative complication. Two days later, Ms. George reports that she is “feeling much better” and is walking in the hallways several times a day. Critical thinking in nursing You may be wondering at this point, “How am I ever going to learn how to make connections among all of the data I have about a patient?” This is a common response for a nursing student who is just learning some of the most basic psychomotor skills in preparation for practice. You need to understand that, just like learning to give injections safely and maintaining a sterile field properly, you can learn to think critically. This involves paying attention to how you think and making thinking itself a focus of concern. A nurse who is exercising critical thinking asks the following questions: “What assumptions have I made about this patient?” “How do I know my assumptions are accurate?” “Do I need any additional information?” and “How might I look at this situation differently?” Nurses just beginning to pay attention to their thinking processes may ask these questions after nurse–patient interactions have ended. This is known as reflective thinking. Reflective thinking is an active process valuable in learning and changing behaviors, perspectives, or practices. Nurses can also learn to examine their thinking processes during an interaction as they learn to “think on their feet.” This is a characteristic of expert nurses. As you move from novice to expert, your ability to think critically will improve with practice. In Chapter 6 you read about Dr. Patricia Benner (1984, 1996), who studied the differences in expertise of nurses at different stages in their careers, from novice to expert. So it is with critical thinking: novices think differently from experts. Box 8-3 summarizes the differences in novice and expert thinking. BOX 8-3 NOVICE THINKING COMPARED WITH EXPERT THINKING Novice nurses • Tend to organize knowledge as separate facts. Must rely heavily on resources (e.g., texts, notes, preceptors). Lack knowledge gained from actually doing (e.g., listening to breath sounds). • Focus so much on actions that they may not fully assess before acting • Need and follow clear-cut rules • Are often hampered by unawareness of resources • May be hindered by anxiety and lack of self-confidence • Tend to rely on step-by-step procedures and follow standards and policies rigidly • Tend to focus more on performing procedures correctly than on the patient’s response to the procedure • Have limited knowledge of suspected problems; therefore they question and collect data more superficially or in a less focused way than more experienced nurses • Learn more readily when matched with a supportive, knowledgeable preceptor or mentor Expert nurses • Tend to store knowledge in a highly organized and structured manner, making recall of information easier. Have a large storehouse of experiential knowledge (e.g., what abnormal breath sounds sound like, what subtle changes look like). • Assess and consider different options for intervening before acting • Know which rules are flexible and when it is appropriate to bend the rules • Are aware of resources and how to use them • Are usually more self-confident, less anxious, and therefore more focused than less experienced nurses • Know when it is safe to skip steps or do two steps together. Are able to focus on both the parts (the procedures) and the whole (the patient response). • Are comfortable with rethinking a procedure if patient needs require modification of the procedure • Have a better idea of suspected problems, allowing them to question more deeply and collect more relevant and in-depth data • Analyze standards and policies, looking for ways to improve them • Are challenged by novices’ questions, clarifying their own thinking when teaching novices From Alfaro-LeFevre R: Critical Thinking in Nursing: A Practical Approach, ed. 2, Philadelphia, 1999, Saunders. Reprinted with permission. Critical thinking is a complex, purposeful, disciplined process that has specific characteristics that make it different from run-of-the-mill problem solving. Critical thinking in nursing is undergirded by the standards and ethics of the profession. Consciously developed to improve patient outcomes, critical thinking by the nurse is driven by the needs of the patient and family. Nurses who think critically are engaged in a process of constant evaluation, redirection, improvement, and increased efficiency. Be aware that critical thinking involves far more than stating your opinion. You must be able to describe how you came to a conclusion and support your conclusions with explicit data and rationales. Becoming an excellent critical thinker is significantly related to increased years of work experience and to higher education level; moreover, nurses with critical thinking abilities tend to be more competent in their practice than nurses with less well-developed critical thinking skills ( Chang , Chang, Kuo et al., 2011). Box 8-4 summarizes these characteristics and offers an opportunity for you to evaluate your progress as a critical thinker. BOX 8-4 SELF-ASSESSMENT: CRITICAL THINKING Directions: Listed below are 15 characteristics of critical thinkers. Mark a plus sign (+) next to those you now possess, mark IP (in progress) next to those you have partially mastered, and mark a zero (0) next to those you have not yet mastered. When you are finished, make a plan for developing the areas that need improvement. Share it with at least one person, and report on progress weekly. Characteristics of critical thinkers: How do you measure up? ______ Inquisitive/curious/seeks truth ______ Self-informed/finds own answers ______ Analytic/confident in own reasoning skills ______ Open-minded ______ Flexible ______ Fair-minded ______ Honest about personal biases/self-aware ______ Prudent/exercises sound judgment ______ Willing to revise judgment when new evidence warrants ______ Clear about issues ______ Orderly in complex matters/organized approach to problems ______ Diligent in seeking information ______ Persistent ______ Reasonable ______ Focused on inquiry An excellent continuing education (CE) self-study module designed to improve your ability to think critically can be found online ( www.nurse.com/ce/CE168-60/Improving-Your-Ability-to-Think-Critically ). Continuing one’s education through lifelong learning is an excellent way to maintain and enhance your critical thinking skills. The website www.nurse.com has more than 500 CE opportunities available online and may be helpful to you as you seek to increase your knowledge base and improve your clinical judgment. Being intentional about improving your critical thinking skills ensures that you bring your best effort to the bedside in providing care for your patients. The nursing process: An intellectual standard Critical thinking requires systematic and disciplined use of universal intellectual standards ( Paul and Elder, 2012). In the practice of nursing, the nursing process represents a universal intellectual standard by which problems are addressed and solved. The nursing process is a method of critical thinking focused on solving patient problems in professional practice. The nursing process is “a conceptual framework that enables the student or the practicing nurse to think systematically and process pertinent information about the patient” ( Huckabay , 2009, p. 72). Humans are involved in problem solving on a daily basis. Suppose your favorite band is performing in a nearby city the night before your big exam in pathophysiology. Your exam counts 35% of your final grade. But you have wanted to see this band since you were 15, and you do not know when you will have another chance. You are faced with weighing a number of factors that will influence your decision about whether to go see the band: your grade going into the exam; how late you will be out the night before the exam; how far you will have to drive to see the band; and how much study time you will have to prepare for the exam in advance. You are really conflicted about this, so you decide to let another factor determine what you will do: the cost of the ticket. When you learn that the only seats available are near the back of the venue and cost $105.00 each, you decide to stay home, get a good night’s sleep before the big exam, and make a 98%. You then realize that with such a good grade on this exam, you will have much less pressure when studying for the final exam at the end of the semester. You have identified a problem (not a particularly serious one, but one with personal significance!), considered various factors related to the problem, identified possible actions, selected the best alternative, evaluated the success of the alternative selected, and made adjustments to the solution based on the evaluation. This is the same general process nurses use in solving patient problems through the nursing process. For individuals outside the profession, nursing is commonly and simplistically defined in terms of tasks nurses perform. Many students get frustrated with activities and courses in nursing school that are not focused on these tasks, believing themselves that the tasks of nursing are nursing. Even within the profession, the intellectual basis of nursing practice was not articulated until the 1960s, when nursing educators and leaders began to identify and name the components of nursing’s intellectual processes. This marked the beginning of the nursing process. In the 1970s and 1980s, debate about the use of the term “diagnosis” began. Until then, diagnosis was considered to be within the scope of practice of physicians only. Although nurses were not educated or licensed to diagnose medical conditions in patients, nurses recognized that there were human responses amenable to independent nursing intervention. A nursing diagnosis, then, is “a clinical judgment about individual, family or community responses to actual or potential health problems or life processes which provide the basis for selection of nursing interventions to achieve outcomes for which the nurse has accountability” (NANDA-I, 2012). These responses could be identified (diagnosed) through the careful application of specific defining characteristics. In 1973, the National Group for the Classification of Nursing Diagnosis published its first list of nursing diagnoses. This organization, which recently celebrated its 40th year, is now known as NANDA International (NANDA-I; NANDA is the acronym for North American Nursing Diagnosis Association). Its mission is to “facilitate the development, refinement, dissemination and use of standardized nursing diagnostic terminology” with the goal to “improve the health care of all people” (NANDA-I, 2012). In 2011, NANDA-I published its 2012–2014 edition of Nursing Diagnoses: Definitions and Classifications. Currently, NANDA-I has more than 200 diagnoses approved for clinical testing and has recently added 16 new diagnoses and 8 revised diagnoses. Diagnoses are also retired if it becomes evident that their usefulness is limited or outdated, such as the former diagnosis “disturbed thought processes.” Here is a simple example of how an approved nursing diagnosis may be used: Two days after a surgery for a large but benign abdominal mass, Mr. Stevens has not yet been able to tolerate solid food and has diminished bowel sounds. His abdomen is somewhat distended. Your diagnosis is that Mr. Stevens has dysfunctional gastrointestinal motility. This diagnosis is based on NANDA-I’s taxonomy because you have determined that the risk factors and physical signs and symptoms associated with this diagnosis apply to him. A more detailed discussion of nursing diagnosis is located in the next section of this chapter. The nursing process as a method of clinical problem solving is taught in schools of nursing across the United States, and many states refer to it in their nurse practice acts. The nursing process has sometimes been the subject of criticism among nurses. In recent years, some nursing leaders have questioned the use of the nursing process, describing it as linear, rigid, and mechanistic. They believe that the nursing process contributes to linear thinking and stymies critical thinking. They are concerned that the nursing process format, and rigid faculty adherence to it, encourages students to copy from published sources when writing care plans, thus inhibiting the development of a holistic, creative approach to patient care ( Mueller , Johnston, and Bligh, 2002). Certainly the nursing process can be taught, learned, and used in a rigid, mechanistic, and linear manner. Ideally the nursing process is used as a creative approach to thinking and decision making in nursing. Because the nursing process is an integral aspect of nursing education, practice, standards, and practice acts nationwide, learning to use it as a mechanism for critical thinking and as a dynamic and creative approach to patient care is a worthwhile endeavor. Despite reservations among some nurses about its use, the nursing process remains the cornerstone of nursing standards, legal definitions, and practice and, as such, should be well understood by every nurse. Phases of the nursing process Like many frameworks for thinking through problems, the nursing process is a series of organized steps, the purpose of which is to impose some discipline and critical thinking on the provision of excellent care. Identifying specific steps makes the process clear and concrete but can cause nurses to use them rigidly. Keep in mind that this is a process, that progression through the process may not be linear, and that it is a tool to use, not a road map to follow rigidly. More creative use of the nursing process may occur by expert nurses who have a greater repertoire of interventions from which to select. For example, if a newly hospitalized patient is experiencing a great deal of pain, a novice nurse might proceed by asking family members to leave so that he or she can provide a quiet environment in which the patient may rest. An expert nurse would realize that the family may be a source of distraction from the pain or may be a source of comfort in ways that the nurse may not be able to provide. The expert nurse, in addition to assessing the patient, is willing to consider alternative explanations and interventions, enhancing the possibility that the patient’s pain will be relieved. Phase 1: Assessment Assessment is the initial phase or operation in the nursing process. During this phase, information or data about the individual patient, family, or community are gathered. Data may include physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, spiritual, and environmental information. The patient’s available financial or material resources also need to be assessed and recorded in a standard format; each institution usually has a slightly different method of recording assessment data. Types of data Nurses obtain two types of data about and from patients: subjective and objective. Subjective data are obtained from patients as they describe their needs, feelings, strengths, and perceptions of the problem. Subjective data are often referred to as symptoms. Examples of subjective data are statements such as, “I am in pain” and “I don’t have much energy.” The only source for these data is the patient. Subjective data should include physical, psychosocial, and spiritual information. Subjective data can be very private. Nurses must be sensitive to the patient’s need for confidence in the nurse’s trustworthiness. Objective data are the other types of data that the nurse will collect through observation, examination, or consultation with other health care providers. These data are measurable, such as pulse rate and blood pressure, and include observable patient behaviors. Objective data are often called signs. An example of objective data that a nurse might gather includes the observation that the patient, who is lying in bed, is diaphoretic, pale, and tachypneic, clutching his hands to his chest. Objective data and subjective data usually are congruent; that is, they usually are in agreement. In the situation just mentioned, if the patient told the nurse, “I feel like a rock is crushing my chest,” the subjective data would substantiate the nurse’s observations (objective data) that the patient is having chest pain. Occasionally, subjective and objective data are in conflict. A stark example of incongruent subjective and objective data well-known to labor and delivery nurses is when a pregnant woman in labor describes ongoing fetal activity (subjective data); however, there are no fetal heart tones (objective data), and the infant is stillborn. Incongruent objective and subjective data require further careful assessment to ascertain the patient’s situation more completely and accurately. Sometimes incongruent data reveal something about the patient’s concerns and fears. To get a clearer picture of the patient’s situation, the nurse should use the best communication skills he or she possesses to increase the patient’s trust, which will result in more openness.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- The education of nurses: On the leading edge of transformation

- Becoming a nurse: Defining nursing and socialization into professional practice

- Illness, culture, and caring: Impact on patients, families, and nurses

- Health care in the United States

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008 Apr.

Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses.

Chapter 6 clinical reasoning, decisionmaking, and action: thinking critically and clinically.

Patricia Benner ; Ronda G. Hughes ; Molly Sutphen .

Affiliations

This chapter examines multiple thinking strategies that are needed for high-quality clinical practice. Clinical reasoning and judgment are examined in relation to other modes of thinking used by clinical nurses in providing quality health care to patients that avoids adverse events and patient harm. The clinician’s ability to provide safe, high-quality care can be dependent upon their ability to reason, think, and judge, which can be limited by lack of experience. The expert performance of nurses is dependent upon continual learning and evaluation of performance.

- Critical Thinking

Nursing education has emphasized critical thinking as an essential nursing skill for more than 50 years. 1 The definitions of critical thinking have evolved over the years. There are several key definitions for critical thinking to consider. The American Philosophical Association (APA) defined critical thinking as purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that uses cognitive tools such as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, and explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations on which judgment is based. 2 A more expansive general definition of critical thinking is

. . . in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. Every clinician must develop rigorous habits of critical thinking, but they cannot escape completely the situatedness and structures of the clinical traditions and practices in which they must make decisions and act quickly in specific clinical situations. 3

There are three key definitions for nursing, which differ slightly. Bittner and Tobin defined critical thinking as being “influenced by knowledge and experience, using strategies such as reflective thinking as a part of learning to identify the issues and opportunities, and holistically synthesize the information in nursing practice” 4 (p. 268). Scheffer and Rubenfeld 5 expanded on the APA definition for nurses through a consensus process, resulting in the following definition:

Critical thinking in nursing is an essential component of professional accountability and quality nursing care. Critical thinkers in nursing exhibit these habits of the mind: confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, openmindedness, perseverance, and reflection. Critical thinkers in nursing practice the cognitive skills of analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting, and transforming knowledge 6 (Scheffer & Rubenfeld, p. 357).

The National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission (NLNAC) defined critical thinking as:

the deliberate nonlinear process of collecting, interpreting, analyzing, drawing conclusions about, presenting, and evaluating information that is both factually and belief based. This is demonstrated in nursing by clinical judgment, which includes ethical, diagnostic, and therapeutic dimensions and research 7 (p. 8).

These concepts are furthered by the American Association of Colleges of Nurses’ definition of critical thinking in their Essentials of Baccalaureate Nursing :

Critical thinking underlies independent and interdependent decision making. Critical thinking includes questioning, analysis, synthesis, interpretation, inference, inductive and deductive reasoning, intuition, application, and creativity 8 (p. 9).

Course work or ethical experiences should provide the graduate with the knowledge and skills to:

- Use nursing and other appropriate theories and models, and an appropriate ethical framework;

- Apply research-based knowledge from nursing and the sciences as the basis for practice;

- Use clinical judgment and decision-making skills;

- Engage in self-reflective and collegial dialogue about professional practice;

- Evaluate nursing care outcomes through the acquisition of data and the questioning of inconsistencies, allowing for the revision of actions and goals;

- Engage in creative problem solving 8 (p. 10).

Taken together, these definitions of critical thinking set forth the scope and key elements of thought processes involved in providing clinical care. Exactly how critical thinking is defined will influence how it is taught and to what standard of care nurses will be held accountable.

Professional and regulatory bodies in nursing education have required that critical thinking be central to all nursing curricula, but they have not adequately distinguished critical reflection from ethical, clinical, or even creative thinking for decisionmaking or actions required by the clinician. Other essential modes of thought such as clinical reasoning, evaluation of evidence, creative thinking, or the application of well-established standards of practice—all distinct from critical reflection—have been subsumed under the rubric of critical thinking. In the nursing education literature, clinical reasoning and judgment are often conflated with critical thinking. The accrediting bodies and nursing scholars have included decisionmaking and action-oriented, practical, ethical, and clinical reasoning in the rubric of critical reflection and thinking. One might say that this harmless semantic confusion is corrected by actual practices, except that students need to understand the distinctions between critical reflection and clinical reasoning, and they need to learn to discern when each is better suited, just as students need to also engage in applying standards, evidence-based practices, and creative thinking.

The growing body of research, patient acuity, and complexity of care demand higher-order thinking skills. Critical thinking involves the application of knowledge and experience to identify patient problems and to direct clinical judgments and actions that result in positive patient outcomes. These skills can be cultivated by educators who display the virtues of critical thinking, including independence of thought, intellectual curiosity, courage, humility, empathy, integrity, perseverance, and fair-mindedness. 9

The process of critical thinking is stimulated by integrating the essential knowledge, experiences, and clinical reasoning that support professional practice. The emerging paradigm for clinical thinking and cognition is that it is social and dialogical rather than monological and individual. 10–12 Clinicians pool their wisdom and multiple perspectives, yet some clinical knowledge can be demonstrated only in the situation (e.g., how to suction an extremely fragile patient whose oxygen saturations sink too low). Early warnings of problematic situations are made possible by clinicians comparing their observations to that of other providers. Clinicians form practice communities that create styles of practice, including ways of doing things, communication styles and mechanisms, and shared expectations about performance and expertise of team members.

By holding up critical thinking as a large umbrella for different modes of thinking, students can easily misconstrue the logic and purposes of different modes of thinking. Clinicians and scientists alike need multiple thinking strategies, such as critical thinking, clinical judgment, diagnostic reasoning, deliberative rationality, scientific reasoning, dialogue, argument, creative thinking, and so on. In particular, clinicians need forethought and an ongoing grasp of a patient’s health status and care needs trajectory, which requires an assessment of their own clarity and understanding of the situation at hand, critical reflection, critical reasoning, and clinical judgment.

Critical Reflection, Critical Reasoning, and Judgment

Critical reflection requires that the thinker examine the underlying assumptions and radically question or doubt the validity of arguments, assertions, and even facts of the case. Critical reflective skills are essential for clinicians; however, these skills are not sufficient for the clinician who must decide how to act in particular situations and avoid patient injury. For example, in everyday practice, clinicians cannot afford to critically reflect on the well-established tenets of “normal” or “typical” human circulatory systems when trying to figure out a particular patient’s alterations from that typical, well-grounded understanding that has existed since Harvey’s work in 1628. 13 Yet critical reflection can generate new scientifically based ideas. For example, there is a lack of adequate research on the differences between women’s and men’s circulatory systems and the typical pathophysiology related to heart attacks. Available research is based upon multiple, taken-for-granted starting points about the general nature of the circulatory system. As such, critical reflection may not provide what is needed for a clinician to act in a situation. This idea can be considered reasonable since critical reflective thinking is not sufficient for good clinical reasoning and judgment. The clinician’s development of skillful critical reflection depends upon being taught what to pay attention to, and thus gaining a sense of salience that informs the powers of perceptual grasp. The powers of noticing or perceptual grasp depend upon noticing what is salient and the capacity to respond to the situation.

Critical reflection is a crucial professional skill, but it is not the only reasoning skill or logic clinicians require. The ability to think critically uses reflection, induction, deduction, analysis, challenging assumptions, and evaluation of data and information to guide decisionmaking. 9 , 14 , 15 Critical reasoning is a process whereby knowledge and experience are applied in considering multiple possibilities to achieve the desired goals, 16 while considering the patient’s situation. 14 It is a process where both inductive and deductive cognitive skills are used. 17 Sometimes clinical reasoning is presented as a form of evaluating scientific knowledge, sometimes even as a form of scientific reasoning. Critical thinking is inherent in making sound clinical reasoning. 18

An essential point of tension and confusion exists in practice traditions such as nursing and medicine when clinical reasoning and critical reflection become entangled, because the clinician must have some established bases that are not questioned when engaging in clinical decisions and actions, such as standing orders. The clinician must act in the particular situation and time with the best clinical and scientific knowledge available. The clinician cannot afford to indulge in either ritualistic unexamined knowledge or diagnostic or therapeutic nihilism caused by radical doubt, as in critical reflection, because they must find an intelligent and effective way to think and act in particular clinical situations. Critical reflection skills are essential to assist practitioners to rethink outmoded or even wrong-headed approaches to health care, health promotion, and prevention of illness and complications, especially when new evidence is available. Breakdowns in practice, high failure rates in particular therapies, new diseases, new scientific discoveries, and societal changes call for critical reflection about past assumptions and no-longer-tenable beliefs.

Clinical reasoning stands out as a situated, practice-based form of reasoning that requires a background of scientific and technological research-based knowledge about general cases, more so than any particular instance. It also requires practical ability to discern the relevance of the evidence behind general scientific and technical knowledge and how it applies to a particular patient. In dong so, the clinician considers the patient’s particular clinical trajectory, their concerns and preferences, and their particular vulnerabilities (e.g., having multiple comorbidities) and sensitivities to care interventions (e.g., known drug allergies, other conflicting comorbid conditions, incompatible therapies, and past responses to therapies) when forming clinical decisions or conclusions.

Situated in a practice setting, clinical reasoning occurs within social relationships or situations involving patient, family, community, and a team of health care providers. The expert clinician situates themselves within a nexus of relationships, with concerns that are bounded by the situation. Expert clinical reasoning is socially engaged with the relationships and concerns of those who are affected by the caregiving situation, and when certain circumstances are present, the adverse event. Halpern 19 has called excellent clinical ethical reasoning “emotional reasoning” in that the clinicians have emotional access to the patient/family concerns and their understanding of the particular care needs. Expert clinicians also seek an optimal perceptual grasp, one based on understanding and as undistorted as possible, based on an attuned emotional engagement and expert clinical knowledge. 19 , 20

Clergy educators 21 and nursing and medical educators have begun to recognize the wisdom of broadening their narrow vision of rationality beyond simple rational calculation (exemplified by cost-benefit analysis) to reconsider the need for character development—including emotional engagement, perception, habits of thought, and skill acquisition—as essential to the development of expert clinical reasoning, judgment, and action. 10 , 22–24 Practitioners of engineering, law, medicine, and nursing, like the clergy, have to develop a place to stand in their discipline’s tradition of knowledge and science in order to recognize and evaluate salient evidence in the moment. Diagnostic confusion and disciplinary nihilism are both threats to the clinician’s ability to act in particular situations. However, the practice and practitioners will not be self-improving and vital if they cannot engage in critical reflection on what is not of value, what is outmoded, and what does not work. As evidence evolves and expands, so too must clinical thought.

Clinical judgment requires clinical reasoning across time about the particular, and because of the relevance of this immediate historical unfolding, clinical reasoning can be very different from the scientific reasoning used to formulate, conduct, and assess clinical experiments. While scientific reasoning is also socially embedded in a nexus of social relationships and concerns, the goal of detached, critical objectivity used to conduct scientific experiments minimizes the interactive influence of the research on the experiment once it has begun. Scientific research in the natural and clinical sciences typically uses formal criteria to develop “yes” and “no” judgments at prespecified times. The scientist is always situated in past and immediate scientific history, preferring to evaluate static and predetermined points in time (e.g., snapshot reasoning), in contrast to a clinician who must always reason about transitions over time. 25 , 26

Techne and Phronesis

Distinctions between the mere scientific making of things and practice was first explored by Aristotle as distinctions between techne and phronesis. 27 Learning to be a good practitioner requires developing the requisite moral imagination for good practice. If, for example, patients exercise their rights and refuse treatments, practitioners are required to have the moral imagination to understand the probable basis for the patient’s refusal. For example, was the refusal based upon catastrophic thinking, unrealistic fears, misunderstanding, or even clinical depression?

Techne, as defined by Aristotle, encompasses the notion of formation of character and habitus 28 as embodied beings. In Aristotle’s terms, techne refers to the making of things or producing outcomes. 11 Joseph Dunne defines techne as “the activity of producing outcomes,” and it “is governed by a means-ends rationality where the maker or producer governs the thing or outcomes produced or made through gaining mastery over the means of producing the outcomes, to the point of being able to separate means and ends” 11 (p. 54). While some aspects of medical and nursing practice fall into the category of techne, much of nursing and medical practice falls outside means-ends rationality and must be governed by concern for doing good or what is best for the patient in particular circumstances, where being in a relationship and discerning particular human concerns at stake guide action.

Phronesis, in contrast to techne, includes reasoning about the particular, across time, through changes or transitions in the patient’s and/or the clinician’s understanding. As noted by Dunne, phronesis is “characterized at least as much by a perceptiveness with regard to concrete particulars as by a knowledge of universal principles” 11 (p. 273). This type of practical reasoning often takes the form of puzzle solving or the evaluation of immediate past “hot” history of the patient’s situation. Such a particular clinical situation is necessarily particular, even though many commonalities and similarities with other disease syndromes can be recognized through signs and symptoms and laboratory tests. 11 , 29 , 30 Pointing to knowledge embedded in a practice makes no claim for infallibility or “correctness.” Individual practitioners can be mistaken in their judgments because practices such as medicine and nursing are inherently underdetermined. 31

While phronetic knowledge must remain open to correction and improvement, real events, and consequences, it cannot consistently transcend the institutional setting’s capacities and supports for good practice. Phronesis is also dependent on ongoing experiential learning of the practitioner, where knowledge is refined, corrected, or refuted. The Western tradition, with the notable exception of Aristotle, valued knowledge that could be made universal and devalued practical know-how and experiential learning. Descartes codified this preference for formal logic and rational calculation.

Aristotle recognized that when knowledge is underdetermined, changeable, and particular, it cannot be turned into the universal or standardized. It must be perceived, discerned, and judged, all of which require experiential learning. In nursing and medicine, perceptual acuity in physical assessment and clinical judgment (i.e., reasoning across time about changes in the particular patient or the clinician’s understanding of the patient’s condition) fall into the Greek Aristotelian category of phronesis. Dewey 32 sought to rescue knowledge gained by practical activity in the world. He identified three flaws in the understanding of experience in Greek philosophy: (1) empirical knowing is the opposite of experience with science; (2) practice is reduced to techne or the application of rational thought or technique; and (3) action and skilled know-how are considered temporary and capricious as compared to reason, which the Greeks considered as ultimate reality.

In practice, nursing and medicine require both techne and phronesis. The clinician standardizes and routinizes what can be standardized and routinized, as exemplified by standardized blood pressure measurements, diagnoses, and even charting about the patient’s condition and treatment. 27 Procedural and scientific knowledge can often be formalized and standardized (e.g., practice guidelines), or at least made explicit and certain in practice, except for the necessary timing and adjustments made for particular patients. 11 , 22

Rational calculations available to techne—population trends and statistics, algorithms—are created as decision support structures and can improve accuracy when used as a stance of inquiry in making clinical judgments about particular patients. Aggregated evidence from clinical trials and ongoing working knowledge of pathophysiology, biochemistry, and genomics are essential. In addition, the skills of phronesis (clinical judgment that reasons across time, taking into account the transitions of the particular patient/family/community and transitions in the clinician’s understanding of the clinical situation) will be required for nursing, medicine, or any helping profession.

Thinking Critically

Being able to think critically enables nurses to meet the needs of patients within their context and considering their preferences; meet the needs of patients within the context of uncertainty; consider alternatives, resulting in higher-quality care; 33 and think reflectively, rather than simply accepting statements and performing tasks without significant understanding and evaluation. 34 Skillful practitioners can think critically because they have the following cognitive skills: information seeking, discriminating, analyzing, transforming knowledge, predicating, applying standards, and logical reasoning. 5 One’s ability to think critically can be affected by age, length of education (e.g., an associate vs. a baccalaureate decree in nursing), and completion of philosophy or logic subjects. 35–37 The skillful practitioner can think critically because of having the following characteristics: motivation, perseverance, fair-mindedness, and deliberate and careful attention to thinking. 5 , 9

Thinking critically implies that one has a knowledge base from which to reason and the ability to analyze and evaluate evidence. 38 Knowledge can be manifest by the logic and rational implications of decisionmaking. Clinical decisionmaking is particularly influenced by interpersonal relationships with colleagues, 39 patient conditions, availability of resources, 40 knowledge, and experience. 41 Of these, experience has been shown to enhance nurses’ abilities to make quick decisions 42 and fewer decision errors, 43 support the identification of salient cues, and foster the recognition and action on patterns of information. 44 , 45

Clinicians must develop the character and relational skills that enable them to perceive and understand their patient’s needs and concerns. This requires accurate interpretation of patient data that is relevant to the specific patient and situation. In nursing, this formation of moral agency focuses on learning to be responsible in particular ways demanded by the practice, and to pay attention and intelligently discern changes in patients’ concerns and/or clinical condition that require action on the part of the nurse or other health care workers to avert potential compromises to quality care.

Formation of the clinician’s character, skills, and habits are developed in schools and particular practice communities within a larger practice tradition. As Dunne notes,

A practice is not just a surface on which one can display instant virtuosity. It grounds one in a tradition that has been formed through an elaborate development and that exists at any juncture only in the dispositions (slowly and perhaps painfully acquired) of its recognized practitioners. The question may of course be asked whether there are any such practices in the contemporary world, whether the wholesale encroachment of Technique has not obliterated them—and whether this is not the whole point of MacIntyre’s recipe of withdrawal, as well as of the post-modern story of dispossession 11 (p. 378).

Clearly Dunne is engaging in critical reflection about the conditions for developing character, skills, and habits for skillful and ethical comportment of practitioners, as well as to act as moral agents for patients so that they and their families receive safe, effective, and compassionate care.

Professional socialization or professional values, while necessary, do not adequately address character and skill formation that transform the way the practitioner exists in his or her world, what the practitioner is capable of noticing and responding to, based upon well-established patterns of emotional responses, skills, dispositions to act, and the skills to respond, decide, and act. 46 The need for character and skill formation of the clinician is what makes a practice stand out from a mere technical, repetitious manufacturing process. 11 , 30 , 47

In nursing and medicine, many have questioned whether current health care institutions are designed to promote or hinder enlightened, compassionate practice, or whether they have deteriorated into commercial institutional models that focus primarily on efficiency and profit. MacIntyre points out the links between the ongoing development and improvement of practice traditions and the institutions that house them:

Lack of justice, lack of truthfulness, lack of courage, lack of the relevant intellectual virtues—these corrupt traditions, just as they do those institutions and practices which derive their life from the traditions of which they are the contemporary embodiments. To recognize this is of course also to recognize the existence of an additional virtue, one whose importance is perhaps most obvious when it is least present, the virtue of having an adequate sense of the traditions to which one belongs or which confront one. This virtue is not to be confused with any form of conservative antiquarianism; I am not praising those who choose the conventional conservative role of laudator temporis acti. It is rather the case that an adequate sense of tradition manifests itself in a grasp of those future possibilities which the past has made available to the present. Living traditions, just because they continue a not-yet-completed narrative, confront a future whose determinate and determinable character, so far as it possesses any, derives from the past 30 (p. 207).

It would be impossible to capture all the situated and distributed knowledge outside of actual practice situations and particular patients. Simulations are powerful as teaching tools to enable nurses’ ability to think critically because they give students the opportunity to practice in a simplified environment. However, students can be limited in their inability to convey underdetermined situations where much of the information is based on perceptions of many aspects of the patient and changes that have occurred over time. Simulations cannot have the sub-cultures formed in practice settings that set the social mood of trust, distrust, competency, limited resources, or other forms of situated possibilities.

One of the hallmark studies in nursing providing keen insight into understanding the influence of experience was a qualitative study of adult, pediatric, and neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, where the nurses were clustered into advanced beginner, intermediate, and expert level of practice categories. The advanced beginner (having up to 6 months of work experience) used procedures and protocols to determine which clinical actions were needed. When confronted with a complex patient situation, the advanced beginner felt their practice was unsafe because of a knowledge deficit or because of a knowledge application confusion. The transition from advanced beginners to competent practitioners began when they first had experience with actual clinical situations and could benefit from the knowledge gained from the mistakes of their colleagues. Competent nurses continuously questioned what they saw and heard, feeling an obligation to know more about clinical situations. In doing do, they moved from only using care plans and following the physicians’ orders to analyzing and interpreting patient situations. Beyond that, the proficient nurse acknowledged the changing relevance of clinical situations requiring action beyond what was planned or anticipated. The proficient nurse learned to acknowledge the changing needs of patient care and situation, and could organize interventions “by the situation as it unfolds rather than by preset goals 48 (p. 24). Both competent and proficient nurses (that is, intermediate level of practice) had at least two years of ICU experience. 48 Finally, the expert nurse had a more fully developed grasp of a clinical situation, a sense of confidence in what is known about the situation, and could differentiate the precise clinical problem in little time. 48

Expertise is acquired through professional experience and is indicative of a nurse who has moved beyond mere proficiency. As Gadamer 29 points out, experience involves a turning around of preconceived notions, preunderstandings, and extends or adds nuances to understanding. Dewey 49 notes that experience requires a prepared “creature” and an enriched environment. The opportunity to reflect and narrate one’s experiential learning can clarify, extend, or even refute experiential learning.

Experiential learning requires time and nurturing, but time alone does not ensure experiential learning. Aristotle linked experiential learning to the development of character and moral sensitivities of a person learning a practice. 50 New nurses/new graduates have limited work experience and must experience continuing learning until they have reached an acceptable level of performance. 51 After that, further improvements are not predictable, and years of experience are an inadequate predictor of expertise. 52

The most effective knower and developer of practical knowledge creates an ongoing dialogue and connection between lessons of the day and experiential learning over time. Gadamer, in a late life interview, highlighted the open-endedness and ongoing nature of experiential learning in the following interview response:

Being experienced does not mean that one now knows something once and for all and becomes rigid in this knowledge; rather, one becomes more open to new experiences. A person who is experienced is undogmatic. Experience has the effect of freeing one to be open to new experience … In our experience we bring nothing to a close; we are constantly learning new things from our experience … this I call the interminability of all experience 32 (p. 403).