- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

The History of the Case Study at Harvard Business School

- 28 Feb 2017

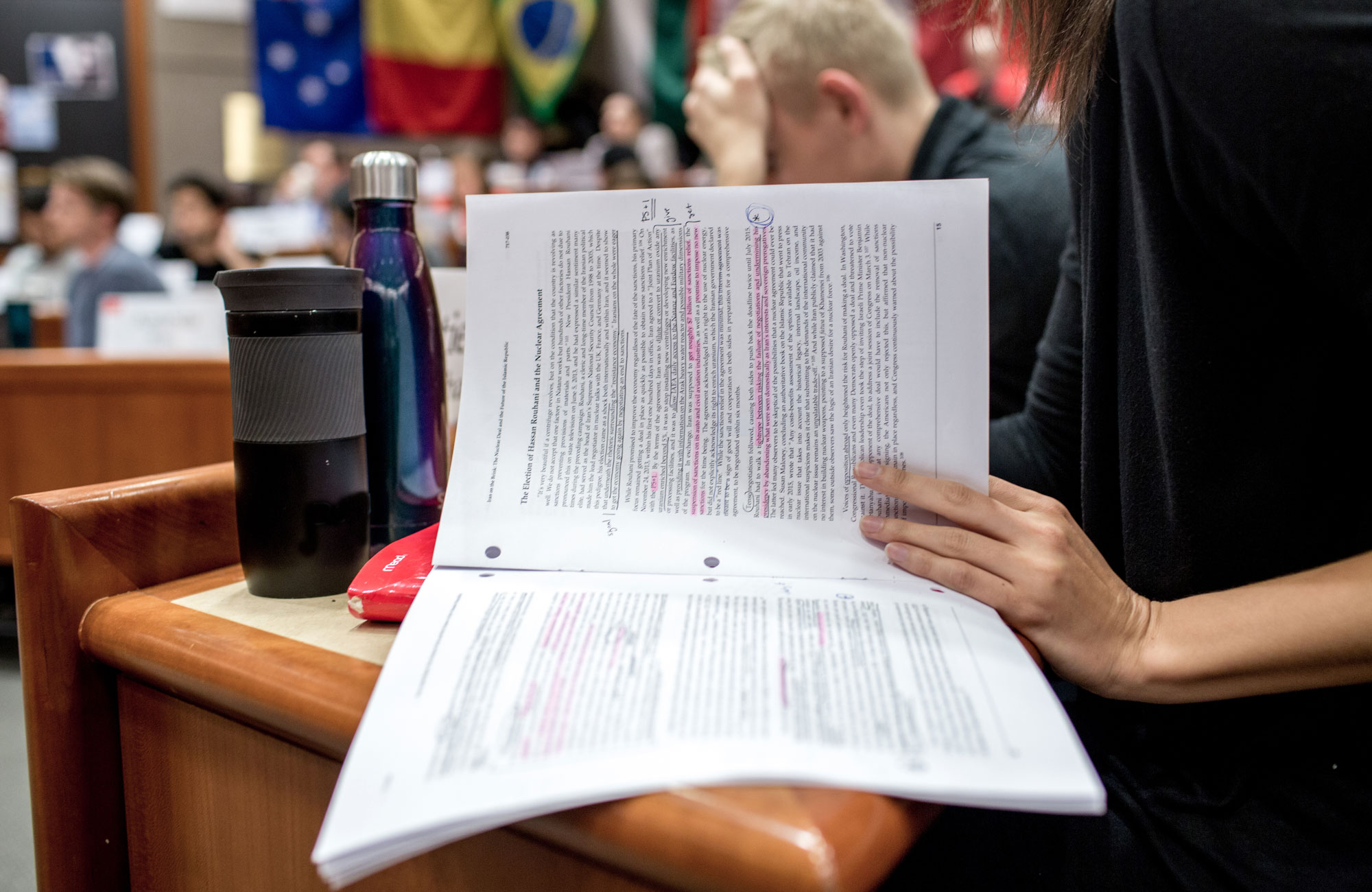

Many first-time HBS Online participants are surprised to learn that, often, the professor is not at the center of their learning experience. Instead of long faculty lectures, the HBS Online learning model centers on smaller, more digestible pieces of content that require participants to interact with each other, test concepts, and learn from real-world examples.

Often, the professor fades into the background and lets the focus shift to interviews with executives, industry leaders, and small business owners. Some students might be left thinking, "Wait, where did that professor go? Why am I learning about a grocery store in Harvard Square?"

In the words of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy , “Don’t panic.” These interviews, or cases, feature leaders at companies of all sizes and provide valuable examples of business concepts in action. This case study method forms the backbone of the Harvard Business School curriculum.

Back in the 1920s, HBS professors decided to develop and experiment with innovative and unique business instruction methods. As the first school in the world to design a signature, distinctive program in business, later to be called the MBA, there was a need for a teaching method that would benefit this novel approach.

HBS professors selected and took a few pages to summarize recent events, momentous challenges, strategic planning, and important decisions undertaken by major companies and organizations. The idea was, and remains to this day, that through direct contact with a real-world case, students will think independently about those facts, discuss and compare their perspectives and findings with their peers, and eventually discover a new concept on their own.

Central to the case method is the idea that students are not provided the "answer" or resolution to the problem at hand. Instead, just like a board member, CEO, or manager, the student is forced to analyze a situation and find solutions without full knowledge of all methods and facts. Without excluding more traditional aspects, such as interaction with professors and textbooks, the case method provides the student with the opportunity to think and act like managers.

Since 1924, the case method has been the most widely applied and successful teaching instrument to come out of HBS, and it is used today in almost all MBA and Executive Education courses there, as well as in hundreds of other top business schools around the world. The application of the case method is so extensive that HBS students will often choose to rely on cases, instead of textbooks or other material, for their research. Large corporations use the case method as well to approach their own challenges, while competing universities create their own versions for their students.

This is what the case method does—it puts students straight into the game, and ensures they acquire not just skills and abstract knowledge, but also a solid understanding of the outside world.

About the Author

Exploring the Relevance and Efficacy of the Case Method 100 Years Later

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Perspectives

I t’s 1921. At the General Shoe Company, employees in the company’s manufacturing plant are routinely stopping work up to 45 minutes before quitting time. It’s not for lack of business—the company has more orders than it can fill. So what, then, is the issue?

After summarizing this situation, General Shoe Company —the first published business case, one page in length—concludes with two questions for the reader:

What factors should be developed in the investigation on the part of management?

What are the general policies in accordance with which these conditions should be remedied?[1]

In other words, what’s going on here, and what should managers do to fix it?

“It’s kind of like a detective story. Something has gone deeply wrong in this factory, and your job as chief executive is to figure out whodunnit—but even before that, figure out what you’re going to ask and of whom.” Jan Rivkin, Harvard Business School professor

Jan Rivkin: It's kind of like a detective story. Something has gone deeply wrong in this factory. And your job as chief executive is to figure out eventually whodunnit—but even before that, to figure out what you're going to ask of whom.

Narrator: In the plant of the General Shoe Company, it has come to the attention of the chief executive that many of the piece workers throughout the plant are in the habit of discontinuing their work three quarters of an hour before closing time. The condition has become acute at the present time because the company has more orders than it can fill.

Rivkin: The first Harvard Business School case study was the General Shoe Company , published in 1921. It was the end of the Progressive era, so a time of deep unrest when the country was struggling with industrialization, urbanization, government corruption, and immigration. And large industrial concerns, particularly in, for instance, railroads or steel, had taken over entire industries. And the idea of management as a profession was very new.

The school was a nascent enterprise. It was 13 years old. No one really knew how to teach business, we didn't know what we would teach or how we'd do it. Well, there were some very specialized courses. You could major in the lumber industry. You could take a course in railroad accounting.

In 1912, the dean of the school, Edwin Gay, took aside Melvin Copeland, who was an early hero of the school, and told him that for one section of a course called commercial organization—what became marketing—he should teach it by discussion and not by lecture. The real turning point was when Wallace Donham was appointed dean in 1919. He believed in his heart this thing called the case method was the way to go for the school. And he did a couple things. He got Melvin Copeland to stop writing a book on marketing and instead collect a set of problems in marketing. And very quickly, Copeland gathered a whole book of often one paragraph long problems from which he'd teach. The second thing is the dean deployed the Bureau of Business Research to hire men to write cases. And the first one was General Shoe by the field agent Clinton Biddle.

So, we don't know for sure why the shoe industry was chosen. But I have a couple theories. First, it's worth remembering that Boston and Massachusetts were kind of the Silicon Valley of shoe making in the late 1800s and the early 1900s. And HBS was really very much a local enterprise at that time. The first graduating class had individuals, three quarters of whom were from Massachusetts. The second possible reason is that HBS faculty were surprisingly familiar with the shoe industry at the time. It turns out that the very first research study done by Harvard Business School under the Bureau of Business Research was an investigation to understand the structure of the shoe retailing industry. I think HBS faculty and students would have felt quite at home with the General Shoe Company.

Narrator: There is general unrest among working men because of the cost of living, which has increased 95 percent since 1914. Wages have not been correspondingly increased. The rule of the shop is that all piece workers are to remain at work until 10 minutes before quitting time. A whistle is blown at this time, and the employees are allowed to leave their work to wash up. The foremen report difficulty in enforcing this rule. It is observed by about 30 percent of the employees who did not wash up before going out. Others take 45 minutes or less from their working time.

Rivkin: It's really deeply wonderfully ambiguous why the workers are leaving their positions early. It could be, as the workers say, because otherwise they'd wind up getting stuck in the washrooms and can't leave on time. It could be that they're upset that their wages are not keeping up with inflation, and this is their protest. It could be that the foremen aren't conveying the message to the workers to stay on the job. It could be that the piece workers are working so hard that they're exhausted before the shift ends. It could be the line is not balanced so that some stations are out of raw material before the workday ends, so they might as well take off. It's a detective story.

What should you, the chief executive, do? The students would come up with a long list of things they might do. But gradually they'd realize, or I would ask them, do you actually have the information you need in order to make a decision on what to do? Acting on the wrong root cause would cause you problems. For me, the important thing in this case is that you can tackle an ambiguous situation and reverse engineer from the options available to you what questions you need to ask as a general manager to learn enough to be able to take reasonable action.

We are here now nearly a century after the General Shoe Company case was first published. And you have to ask, is the case method still relevant? There are new technologies, new methods—but I think the fundamentals of the case method are still very sound. The experiences that engage students, the experiences that force them to think critically, to sort out important from unimportant facts, to think for themselves, consider alternatives, listen to others, explain their views to others, make a decision—those experiences will continue to deliver powerful learning.

What I love about General Shoe is it allows students to practice a core skill of general managers. How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it? That skill, the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry, to choose a course of action, that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.

Source: “Celebrating General Shoe Company, the Inaugural HBS Case,” Harvard Business School, April 12, 2019, https://www.hbs.edu/about/video.aspx?v=1_0486ljh3 .

Cases have changed considerably since General Shoe Company was published. Today, most are much longer than one page. Most include a variety of data and exhibits that are derived from extensive field and secondary research. Many have teaching notes and other supplementary materials such as spreadsheets and data sets. Some contain audio, video, or even virtual reality components.

THE CENTENNIAL OF THE BUSINESS CASE: A 5-PART SERIES

Part 1: Exploring the Relevance and Efficacy of the Case Method 100 Years Later

Part 2: The Heart of the Case Method

Part 3: The Art of the Case Method

Part 4: Tales from the Trenches

Part 5: The Future of the Case Method

THE SERIES TRANSLATED

Access free PDFs of this five-part article series, translated into each of the following languages:

汉语 (Mandarin)

日本語 (Japanese)

Español (Spanish)

Français (French)

Português (Portuguese)

Yet, as we approach the centennial of General Shoe Company , there are also important commonalities between cases from 1921 and 2021. Then as now, most cases describe an actual decision-making situation that managers have faced. Then as now, most cases place the reader in the proverbial shoes of these managers and ask them to use the information provided in the case to decide what they and their company should do. And then, as now, cases do not provide “the answer” to the challenge at hand—they rely on ensuing discussion and knowledge-sharing among students for the learning to unfold.

Where It All Began

The authors of the earliest business cases drew inspiration from the use of edited cases of court decisions to teach law students. Yet, these authors also argued that business education required materials and teaching methods different from those used in law schools. They believed that, unlike law, business had no “practices and precedents”[2] upon which students could always rely. Like case authors today, they thus wanted to develop materials that would help students learn to define and solve ill-defined managerial problems under time constraints, uncertainty, and ever-changing conditions.

Business Cases in 2021

Today, about 15 million business cases are sold annually to students. Over 50 business schools worldwide now have case collections. Thousands of new cases are written and released every year. These data suggest that even as cases have and will continue to change, the case method has enduring appeal and influence.

Where We Go from Here

In this centennial series, we will highlight how the case method can transform both students and faculty. To do so, we will examine what case-method teaching entails and hear directly from numerous faculty who will share their own personal stories and perspectives of teaching cases. In addition, we will consider potential future directions for cases and the implications of this evolution for the case method.

Finally, we want you to tell us about your experiences with cases . What about case teaching or writing has been rewarding? What’s been difficult? What have your favorite cases been and why? We want to incorporate your insights into our future coverage of cases. We look forward to hearing from you.

[1] Clinton Biddle, General Shoe Company. Boston: Harvard Business School, 1921.

[2] Wallace B. Donham, “Business Teaching by the Case System,” The American Economic Review 12 (March 1922): 53–65.

Explore all 5 parts of our series celebrating 100 years of the business case.

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Exhibition Home

- Business Education & The Case Method

- The General Shoe Company, 1921

- Case Writing & Industry

- Expansion of the Case Method

- The Case Method Classroom

- Teaching & The Case Method

- Impact on Research & Curriculum

- Global Reach

- Research Resources

- From the Director

- Site Credits

- Visit & Contact Us

- Special Collections

- Baker Library

- Case Method

Research Resources: History of the Case Method at HBS

Compiled by the HBS Archives, this guide provides links to key sources on the history of teaching with the case method at Harvard Business School and its expansion to business schools around the globe.

Published resources are available online or at Baker Library, HBS and other Harvard Libraries.

- Case Method 100 Years: Timeline, News Articles, Videos

Case Method 100 Years

Visit the Case Method 100 Years website to see video interviews with faculty and alumni, news articles, and an illustrated timeline of 100 years of the case method at HBS.

Case Method Centennial Celebration: General Shoe Company (April 20, 2022)

At the Case Method Centennial Celebration, Professor Jan Rivkin taught the School's first case to staff, faculty, and students, with opening remarks from Dean Datar.

“ Exploring the Relevance and Efficacy of the Case Method 100 Years Later ,” Harvard Business Publishing, April 13, 2021.

This is the first in a five-part series celebrating the centennial of the first case. The other four parts are linked on the page.

The HBS Case Method Defined (January 20, 2021)

Take a Seat in the Harvard MBA Case Classroom (May 28, 2020)

“ Discover the Case Method ,” MBA Voices (May 8, 2019)

In this video, students discuss their experiences learning via the case method.

Celebrating the General Shoe Company, the Inaugural HBS Case (April 12, 2019)

In this video, Professor Jan Rivkin discusses the first case and the history of the case method.

Inside the Case Method (April 10, 2009)

- Core Works on the Case Method

Andrews, Kenneth R., ed., The Case Method of Teaching Human Relations and Administration: An Interim Statement . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951.

This book is a collection of chapters by HBS faculty and staff, with sections on Teaching and Learning, Training in Industry, and Research Problems in Human Relations.

Christensen, C. Roland, et al., Education for Judgment. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press, 1991.

Resources -- The Christensen Center for Teaching and Learning

The Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning maintains its own list of resources for faculty and students.

Copeland, Melvin T., And Mark an Era: The Story of the Harvard Business School . Boston: Little Brown, 1958.

This is a history of Harvard Business School, written by Melvin T. Copeland, professor and Director of the Division of Research, who was instrumental in the early development of the case method and who authored the first published book of cases, Marketing Problems .

Donham, Wallace B., Dean’s Report, “ Graduate School of Business Administration ,” Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College, 1919-1920, Official Register of Harvard University , vol. xviii, no. 7, March 3, 1921, pp. 111-135.

On pages 119-121 of this report from Dean Donham to Abbott Lawrence Lowell, Harvard University’s twenty-second president, Donham discusses the challenges of gathering cases for business education, as compared to the field of law.

Donham, Wallace B., Dean’s Report, “ Graduate School of Business Administration ,” Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College, 1922-1923, Official Register of Harvard University , vol. xxi, no. 6, February 29, 1924, pp. 107-138.

On pages 117-122 of this report from Dean Donham to Harvard University President A. Lawrence Lowell, Donham describes efforts to increase the collection and distribution of cases.

Donham, Wallace B., Dean’s Report, “ Graduate School of Business Administration ,” Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College, 1941-1942, Official Register of Harvard University , vol. xli, no. 23, September 26, 1944, pp. 257-291.

This is Dean Donham’s final report to James B. Conant, Harvard University’s twenty-third president, in which he reflects on the evolution of the school and the case method during his tenure as Dean.

Foster, Esty and Philip B. Hoppin, “ The Harvard Business School 1908-1936 ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. XII, no. 4, July 1936, pp. 266-278.

This is a history of the school through 1936, which covers the introduction and use of the case method, among other topics.

Garvin, David, “ Making the Case: Professional Education for the World of Practice ,” Harvard Magazine , September-October 2003.

McNair, Malcolm P., ed., The Case Method at the Harvard Business School: papers by present and past members of the faculty and staff . Boston: McGraw-Hill Book Co.,1954.

This book includes a few cases, some reflections from recent graduates, and chapters on pedagogy and research. A review and the table of contents was printed in the HBS Bulletin in Spring 1954.

- Researching, Writing, and Distributing Cases

Culliton, James W., “Writing Business Cases,” in McNair, Malcolm P., ed. , The Case Method at the Harvard Business School: papers by present and past members of the faculty and staff . Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1954.

Culliton, James W., Handbook on Case Writing . Makati, Rizal, Philippines: Asian Institute of Management, 1973.

Copeland, Melvin T., And Mark an Era: The Story of the Harvard Business School . Boston: Little Brown, 1958, pp. 227-238 .

This section of And Mark an Era describes the formation of the Bureau of Business Research and the methods of case collection.

David, Donald K., Dean’s Report, “ Graduate School of Business Administration ,” Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College, 1953-1954, Official Register of Harvard University , vol. lii, October 31, 1955, no. 28, pp. 621-651.

On pages 636-641 of this report from Dean David to Harvard University President Nathan Pusey, David describes the creation of the Office of Case Development and efforts to distribute cases more widely.

Fayerweather, John, “The Work of the Case Writer,” in McNair, Malcolm P., ed., The Case Method at the Harvard Business School: papers by present and past members of the faculty and staff . Boston: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1954.

“ How Cases Get That Way ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. 30, no. 3, Autumn 1954, pp. 34-35.

This is a description of how cases were written for the Written Analysis of Cases course, which had been introduced a few years earlier and ran until the early 1970s.

Lawrence, Paul R., “The Preparation of Case Material,” in Andrews, Kenneth R., ed., The Case Method of Teaching Human Relations and Administration: An Interim Statement . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951.

McNair, Malcolm P., “The Collection of Cases,” in Fraser, Cecil E., ed., The Case Method of Instruction: a Related Series of Articles . Boston: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1931.

“ McNair on Cases ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. 47, no. 4, July-August 1971, pp. 10-13.

This piece is a collection of remarks by Professor Malcolm McNair on the art of writing cases.

- Teaching with the Case Method

Bailey, Joseph C., “A Classroom Evaluation of the Case Method.” Harvard Educational Review , Summer, 1951.

Barnes, Louis B., et al., T eaching and the Case Method : Text, Cases, and Readings . 3rd ed. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press, 1994.

Berrien, F. K., "Instructor's Appendix," in Comments and Cases on Human Relations , New York: Harper Brothers, 1952.

Cabot, Philip, “The Case System,” Ex Libris , vol. iii, no. 1, January 1928.

Christensen, C. Roland, Teaching by the Case Method: Past Accomplishments, Future Developments . Boston: Division of Research, Harvard Business School, 1981.

Copeland, Melvin T., “ The Expansion of the Case Method of Instruction ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. xviii, no. 3, Summer 1942, pp. 225-227.

This article is an overview of the first 20 years of case collection and instruction.

Copeland, Melvin T., And Mark an Era: The Story of the Harvard Business School , Boston: Little Brown, 1958, pp. 254-272 .

In this chapter of And Mark an Era , Copeland recounts the introduction of the case method and describes its pedagogy.

Culliton, James W., “The Question that Has Not Been Asked Cannot Be Answered,” Education for Professional Responsibility , Pittsburgh: Carnegie Press, 1948, pp. 85-93.

David, Donald K., “Methods of Teaching Business in Schools of Business,” The Ronald Forum, Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Meeting of the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Business , 1925.

Donham, Wallace B., “ Business Teaching by the Case System ,” The American Economic Review , vol. 12, no. 1, March 1922, pp. 53-65.

In this article, Donham compares the pedagogy of business and law through the lens of the case method and describes the use of cases in the classroom.

Fraser, Cecil E., ed. The Case Method of Instruction: a Related Series of Articles . Boston: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1931.

This volume includes some chapters on the case method in general, as well as chapters on the case method in specific fields of business, such as marketing and finance. The chapters are authored by HBS faculty, including Donham, Doriot, and McNair. A brief review was published in the HBS Bulletin .

Parsons, Floyd W., “Harvard Teaching Business the Way it Teaches Law,” World’s Work , June 1923.

Schaub, L. F., “ The Case System of Instruction in Business Management ,” Harvard Graduates’ Magazine , June 1910, pp. 641-644.

This is one of the earliest published descriptions of the case method at HBS. Lincoln Schaub would later be Assistant Dean and briefly Acting Dean after the departure of Dean Gay.

Taeusch, C. F., “ The Logic of the Case Method ,” The Journal of Philosophy , vol. 25, no. 10, 1928, pp. 253-263.

This article is focused primarily on the study of law, but examines the case method as a means of teaching good judgement and ethics. In this same year, Taeusch joined the HBS faculty to teach the first full course on business ethics, using the case method.

Turner, Glen, “Teaching Business by the Case Method,” California Journal of Secondary Education , October 1938, p. 338-349.

- Learning with the Case Method

“ The Alumni Forum: The Business School’s Factor Sheet ” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. xvi, no. 2, February 1940, pp. 119-124.

This article summarizes the results of a survey of alumni, and includes many quotes from former students on the pros and cons of the case method.

Carson, W. Waller, Jr., “Development of a Student Under the Case Method,” in McNair, Malcolm P., ed. The Case Method at the Harvard Business School: papers by present and past members of the faculty and staff . Boston: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1954.

“ Case Method of Instruction ,” Course Catalog, Official Register of Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration , vol. lii, no. 10, May 31, 1955, pp. 27-28.

This segment describes the role of cases in the curriculum in 1955.

“ General Statement ,” Course Catalog, Official Register of Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration , vol. xxii, no. 5, February 20, 1924, pp. 10-29.

Pages 16-18 briefly describe the role of cases in the curriculum in 1924.

Gragg, Charles I., “Because Wisdom Can’t be Told,” in Andrews, Kenneth R., ed., The Case Method of Teaching Human Relations and Administration: An Interim Statement . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951.

In this chapter, Gragg describes the impact of the case method on the student experience.

Donham, Wallace B., Dean’s Report, “ Graduate School of Business Administration ,” Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College, 1938-39, Official Register of Harvard University , vol. xxxvii, no. 12, March 30, 1940, pp. 265-283.

In this report to President Conant, Donham describes the role that case collection and distribution, increasingly to other schools of business, plays in the financial health of the school.

Hunt, Pearson, “ Exporting the Case Method ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. 31, no. 1, Spring 1955, pp. 5-10.

This is an abridged printing of a talk that Hunt gave on the use of the case method at European schools of business.

Tagiuri, Renato, “The Foreign Student and the Case Method in Business Administration: Some Remarks Concerning the Learning Process,” The Journal of Social Psychology , vol. 53, no. 1, 1961, pp. 105-111.

Professor Tagiuri taught and represented HBS at business schools in Europe and Central America. In this article he describes his experience teaching to a non-American audience.

Tosdal, Harry, “ The Case Method in Teaching Business Executives ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. vi, no. 4, April 1, 1930, pp. 152-154.

This article describes the early stages of executive education at HBS, and the adaptation of the case method to students who are already experienced businessmen.

Campbell, Scott, “ Teaching by the Case Method ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. 60, no. 6, December 1984, pp. 88-95.

This article describes a symposium for educators who teach by the case method. Participants represented 24 states and six countries.

- Innovation in Cases

Blanding, Michael, “ The Tulsa Massacre: Is Racial Justice Possible 100 Years Later? ,” HBS Working Knowledge , March 2, 2021.

This article describes the context and innovation of the interactive multimedia case, “ The Tulsa Massacre and the Call for Reparations ,” which was made available to the public.

Gibson, George W., “ Cases on Film ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. 31, no. 3, Autumn 1955, pp. 34-35.

In this article, the director of the audio-visual department announces the introduction of filmed cases.

“ While the Cat’s Away: A Case in Pictures ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. 33, no. 2, Summer 1957, pp. 15-18.

This Bulletin article shows a sample of images from one of the early cases on film.

“ Where Do We Go From Here? HBS Marks its Fiftieth Year by Re-examining its Mission in a New Society ,” Harvard Business School Bulletin , vol. 34, no. 2, April 1958, pp. 4-16.

This Bulletin article includes a reflection on improvements to the case method and a look forward at possible changes.

- HBS Archival Collections

Bureau of Business Research records

The Bureau of Business Research was formed in 1911 and was responsible for all research conducted at the school, including the writing of cases, until the formation of the Office of Case Development in 1953.

Bureau of Business Research instructions to agents on standard practice

These instructions, issued under the guidance of Malcolm P. McNair, were intended to standardize the case writing process.

C. Roland Christensen papers

Christensen was a leader in case method pedagogy; the Christensen Center for Teaching and Learning is named in his honor. His papers include case writing materials and research for his books on the subject.

Dean’s Office Correspondence Files (Edwin F. Gay, Dean)

Gay was the first Dean of HBS, from 1908 to 1919. Although the case method was not fully implemented until after his tenure, he oversaw the early discussions of pedagogy and the use of the law school as a model.

Dean’s Office Correspondence Files (Wallace B. Donham, Dean)

Donham was Dean of HBS from 1919 to 1942, during which time he oversaw the formalization and expansion of the case method.

Kenneth Andrews papers

Andrews published extensively on the case method and his papers include the research materials for his book, The Case Method of Teaching Human Relations and Administration , included above.

Melvin Thomas Copeland papers

Copeland was the author of the first published book of cases, Marketing Problems , and was the Director of the Bureau of Business Research from 1916 to 1926.

Malcolm P. McNair papers

McNair was the Assistant Director of the Bureau of Business Research from 1922-1929 and Managing Director from 1929-1933. He wrote many articles about the case method and edited a collection of papers on the case method by HBS faculty and staff (included above in the first section of this guide).

Office of the Dean subject files

Spanning from 1908 to 1955, this collection documents the activities of the Office of the Dean, including case collection, distribution, and teaching.

Wallace Brett Donham cases and teaching files

This is a collection of cases that Dean Donham compiled, edited, and taught. It also includes some of Donham's lecture notes.

Visit HBS History to learn more about the HBS Archives and how to access collections.

- > Master in Management (MiM)

- > Master in Research in Management (MRM)

- > PhD in Management

- > Executive MBA

- > Global Executive MBA

- Programs for Individuals

- Programs for Organizations

- > Artificial Intelligence for Executives

- > Foundations of Scaling

- > Sustainability & ESG

- CHOOSE YOUR MBA

- IESE PORTFOLIO

- PROGRAM FINDER

- > Faculty Directory

- > Academic Departments

- > Initiatives

- > Competitive Projects

- > Academic Events

- > Behavioral Lab

- > Limitless Learning

- > Learning Methodologies

- > The Case Method

- > IESE Insight: Research-Based Ideas

- > IESE Business School Insight Magazine

- > StandOut: Career Inspiration

- > Professors' Blogs

- > Alumni Learning Program

- > IESE Publishing

- SEARCH PUBLICATIONS

- IESE NEWSLETTERS

- > Our Mission, Vision and Values

- > Our History

- > Our Governance

- > Our Alliances

- > Our Impact

- > Diversity at IESE

- > Sustainability at IESE

- > Accreditations

- > Annual Report

- > Roadmap for 2023-25

- > Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- > Barcelona

- > São Paulo

- > Security & Campus Access

- > Loans and Scholarships

- > Chaplaincy

- > IESE Shop

- > Jobs @IESE

- > Compliance Channel

- > Contact Us

- GIVING TO IESE

- WORK WITH US

The Case Study method: 100 years young

On its 100th anniversary, the discussion-based learning method keeps evolving

Case study discussions can also take place in a variety of different contexts, whether studied in person, in hybrid formats or through our virtual classroom.

May 3, 2021

This year commemorates the 100 th anniversary of the first written case study, produced by Harvard Business School back in April 1921. IESE joins in the celebration because it’s one of the academic institutions that has helped spearhead the use of the case method outside the U.S. , educating more than 60,000 professionals with this methodology and producing around 6,200 original cases through more than 60 years of history.

But what is the case study method exactly, and why is it still relevant now?

The main reason the case method is still relevant today is that it works. It’s a dynamic, practical way to study, which puts students in the shoes of senior executives, allowing them to practice solving real-life business problems and making strategic decisions.

It is also an example of a learning methodology based on the exchange of ideas and debate. At IESE, we recognize that the best way to learn is through interacting with others, and having your perspectives and assumptions challenged and stretched . The case study is one example of how we do this, alongside a variety of other discussion-based learning methodologies , such as business simulations, coaching or experiential learning.

For the case method, this means that passively sitting in a lecture room doesn’t cut it. Instead, all participants are required to discuss and reflect on the issues at hand. Here, the professor acts more as a facilitator, guiding the conversation and teasing out the various ethical and business implications of each case. The discussions also draw upon the diverse industry experiences, cultural backgrounds and mindsets of each individual in class, further enriching the learning process.

New content and formats, same impact

Throughout the last 100 years, the case method has been able to adapt with the times by constantly evolving . Indeed, in the last three years, 200 new cases have been written by IESE professors on the most pressing issues happening now. An example of this is the case of how Barcelona-based Vall d’Hebron University Hospital managed the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Our cases also have a distinct international perspective, reflecting the diversity of the school, faculty and students. While many assume most case studies just focus on big North American companies, at IESE our cases cover not only big name companies like YouTube and Spotify but also companies in emerging countries and young startups. We also have one of the largest collections in the world of Spanish-language cases.

Having a diverse set of cases to study – and a diverse student body to discuss them with – is the key to encouraging those lively and enriching debates that are so crucial to broadening participants’ perspectives.

In addition to content, nowadays cases are available in a variety of formats , such as audio cases that allow participants to listen to a case as they would a podcast, and simulations, among others.

Case study discussions can also take place in a variety of different contexts, whether studied in person, in hybrid formats or through our virtual classroom. This reflects the fact that today’s managers require educational solutions that allow for flexibility , but that also guarantee interaction with others and personalized follow-up.

IESE has one of the largest collections of Spanish-language cases in the world. The full catalog is available in the IESE Publishing online store, which also distributes the cases of 15 leading universities. Here, we present some of the more recent challenges from cases that we have produced .

“At IESE, our focus is on delivering the best learning experience possible, regardless of the format or context. As technologies advance, the case method also continues to evolve. Yet the essence of how executives learn best – and the value that comes from sharing knowledge and exchanging viewpoints with a diverse set of peers – remains the same,” said Prof. Julia Prats .

- case method

Related stories

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Case Study Research Method in Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. Typically, data is gathered from various sources using several methods (e.g., observations & interviews).

The case study research method originated in clinical medicine (the case history, i.e., the patient’s personal history). In psychology, case studies are often confined to the study of a particular individual.

The information is mainly biographical and relates to events in the individual’s past (i.e., retrospective), as well as to significant events that are currently occurring in his or her everyday life.

The case study is not a research method, but researchers select methods of data collection and analysis that will generate material suitable for case studies.

Freud (1909a, 1909b) conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

This makes it clear that the case study is a method that should only be used by a psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist, i.e., someone with a professional qualification.

There is an ethical issue of competence. Only someone qualified to diagnose and treat a person can conduct a formal case study relating to atypical (i.e., abnormal) behavior or atypical development.

Famous Case Studies

- Anna O – One of the most famous case studies, documenting psychoanalyst Josef Breuer’s treatment of “Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) for hysteria in the late 1800s using early psychoanalytic theory.

- Little Hans – A child psychoanalysis case study published by Sigmund Freud in 1909 analyzing his five-year-old patient Herbert Graf’s house phobia as related to the Oedipus complex.

- Bruce/Brenda – Gender identity case of the boy (Bruce) whose botched circumcision led psychologist John Money to advise gender reassignment and raise him as a girl (Brenda) in the 1960s.

- Genie Wiley – Linguistics/psychological development case of the victim of extreme isolation abuse who was studied in 1970s California for effects of early language deprivation on acquiring speech later in life.

- Phineas Gage – One of the most famous neuropsychology case studies analyzes personality changes in railroad worker Phineas Gage after an 1848 brain injury involving a tamping iron piercing his skull.

Clinical Case Studies

- Studying the effectiveness of psychotherapy approaches with an individual patient

- Assessing and treating mental illnesses like depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD

- Neuropsychological cases investigating brain injuries or disorders

Child Psychology Case Studies

- Studying psychological development from birth through adolescence

- Cases of learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD

- Effects of trauma, abuse, deprivation on development

Types of Case Studies

- Explanatory case studies : Used to explore causation in order to find underlying principles. Helpful for doing qualitative analysis to explain presumed causal links.

- Exploratory case studies : Used to explore situations where an intervention being evaluated has no clear set of outcomes. It helps define questions and hypotheses for future research.

- Descriptive case studies : Describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. It is helpful for illustrating certain topics within an evaluation.

- Multiple-case studies : Used to explore differences between cases and replicate findings across cases. Helpful for comparing and contrasting specific cases.

- Intrinsic : Used to gain a better understanding of a particular case. Helpful for capturing the complexity of a single case.

- Collective : Used to explore a general phenomenon using multiple case studies. Helpful for jointly studying a group of cases in order to inquire into the phenomenon.

Where Do You Find Data for a Case Study?

There are several places to find data for a case study. The key is to gather data from multiple sources to get a complete picture of the case and corroborate facts or findings through triangulation of evidence. Most of this information is likely qualitative (i.e., verbal description rather than measurement), but the psychologist might also collect numerical data.

1. Primary sources

- Interviews – Interviewing key people related to the case to get their perspectives and insights. The interview is an extremely effective procedure for obtaining information about an individual, and it may be used to collect comments from the person’s friends, parents, employer, workmates, and others who have a good knowledge of the person, as well as to obtain facts from the person him or herself.

- Observations – Observing behaviors, interactions, processes, etc., related to the case as they unfold in real-time.

- Documents & Records – Reviewing private documents, diaries, public records, correspondence, meeting minutes, etc., relevant to the case.

2. Secondary sources

- News/Media – News coverage of events related to the case study.

- Academic articles – Journal articles, dissertations etc. that discuss the case.

- Government reports – Official data and records related to the case context.

- Books/films – Books, documentaries or films discussing the case.

3. Archival records

Searching historical archives, museum collections and databases to find relevant documents, visual/audio records related to the case history and context.

Public archives like newspapers, organizational records, photographic collections could all include potentially relevant pieces of information to shed light on attitudes, cultural perspectives, common practices and historical contexts related to psychology.

4. Organizational records

Organizational records offer the advantage of often having large datasets collected over time that can reveal or confirm psychological insights.

Of course, privacy and ethical concerns regarding confidential data must be navigated carefully.

However, with proper protocols, organizational records can provide invaluable context and empirical depth to qualitative case studies exploring the intersection of psychology and organizations.

- Organizational/industrial psychology research : Organizational records like employee surveys, turnover/retention data, policies, incident reports etc. may provide insight into topics like job satisfaction, workplace culture and dynamics, leadership issues, employee behaviors etc.

- Clinical psychology : Therapists/hospitals may grant access to anonymized medical records to study aspects like assessments, diagnoses, treatment plans etc. This could shed light on clinical practices.

- School psychology : Studies could utilize anonymized student records like test scores, grades, disciplinary issues, and counseling referrals to study child development, learning barriers, effectiveness of support programs, and more.

How do I Write a Case Study in Psychology?

Follow specified case study guidelines provided by a journal or your psychology tutor. General components of clinical case studies include: background, symptoms, assessments, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Interpreting the information means the researcher decides what to include or leave out. A good case study should always clarify which information is the factual description and which is an inference or the researcher’s opinion.

1. Introduction

- Provide background on the case context and why it is of interest, presenting background information like demographics, relevant history, and presenting problem.

- Compare briefly to similar published cases if applicable. Clearly state the focus/importance of the case.

2. Case Presentation

- Describe the presenting problem in detail, including symptoms, duration,and impact on daily life.

- Include client demographics like age and gender, information about social relationships, and mental health history.

- Describe all physical, emotional, and/or sensory symptoms reported by the client.

- Use patient quotes to describe the initial complaint verbatim. Follow with full-sentence summaries of relevant history details gathered, including key components that led to a working diagnosis.

- Summarize clinical exam results, namely orthopedic/neurological tests, imaging, lab tests, etc. Note actual results rather than subjective conclusions. Provide images if clearly reproducible/anonymized.

- Clearly state the working diagnosis or clinical impression before transitioning to management.

3. Management and Outcome

- Indicate the total duration of care and number of treatments given over what timeframe. Use specific names/descriptions for any therapies/interventions applied.

- Present the results of the intervention,including any quantitative or qualitative data collected.

- For outcomes, utilize visual analog scales for pain, medication usage logs, etc., if possible. Include patient self-reports of improvement/worsening of symptoms. Note the reason for discharge/end of care.

4. Discussion

- Analyze the case, exploring contributing factors, limitations of the study, and connections to existing research.