CSEC ENGLISH A SAMPLE ESSAY 1: ARGUMENTATIVE

Please Report Any Errors using this form .

Thank you for using our website for your CSEC and CAPE past paper solutions. Please note that we are not affiliated with the Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC) in any way. Our solutions are created independently and are intended to supplement your studying and preparation for these exams. We wish you all the best in your academic pursuits.

ENG 102: Persuasive/Argumentative Essay

- About the Persuasive Essay

- Developing Questions

- The Thesis Statement

- Reading Scholarly Sources

- Collecting Scholarly Information

- Research Databases

- MLA Resources

Research Topic Basics

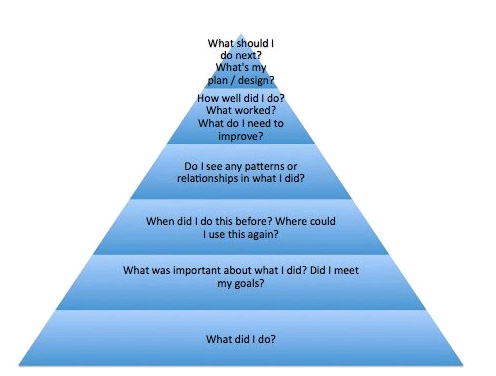

The process of developing your topic into a researchable thesis or question can seem intimidating, but if you give yourself a bit of time at the beginning of the assignment timeline it can be a straightforward process. Think about it in stages:

- Think of a subject that interests you and consider how it might overlap with the assignment prompt; the area of overlap becomes your topic (see below).

- Who, What, When,. Where, Why, How?

- In what way; under what circumstances?

- Apply limiters such as Time/Event, Place, Person/Group, Aspect/Facet

- Which questions best address the assignment prompt?

- Which are most researchable?

- Which ones interest you the most?

- Answer the question with either a defensible position if you are writing a persuasive/argumentative essay or with a clear factual statement if you are writing an expository/informative essay. This is the defensible position that is the core of your thesis..

- Craft a thesis statement thesis statement that contextualizes your position within the broader topic and mentions several factual facets that support your position. See The Thesis Statement tab for more information!

As you learn more about your topic you might find that your thesis statement needs to be tweaked or adjusted; that is OK! We call the early version of the statement a 'working thesis' because we expect that as you learn more about the subject, your understanding will evolve and develop, and your thoughts and opinions might change. Just make sure your instructor approves any adjustments and proceed with your research.

Allow yourself time to develop your topic!

Seminole State Library. (2014, January 29). 5 components of information literacy [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ronp6Iue9w

Research as Inquiry

“ Research is iterative and depends upon asking increasingly complex or new questions whose answers in turn develop additional questions or lines of inquiry in any field.”

Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). (2021, October 13). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education . ACRL Guidelines, Standards, and Frameworks. https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework#inquiry

- << Previous: About the Persuasive Essay

- Next: Developing Questions >>

- Last Updated: Mar 28, 2024 2:37 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gateway.kctcs.edu/ENG102PersuasiveEssay

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write an a+ argumentative essay.

Miscellaneous

You'll no doubt have to write a number of argumentative essays in both high school and college, but what, exactly, is an argumentative essay and how do you write the best one possible? Let's take a look.

A great argumentative essay always combines the same basic elements: approaching an argument from a rational perspective, researching sources, supporting your claims using facts rather than opinion, and articulating your reasoning into the most cogent and reasoned points. Argumentative essays are great building blocks for all sorts of research and rhetoric, so your teachers will expect you to master the technique before long.

But if this sounds daunting, never fear! We'll show how an argumentative essay differs from other kinds of papers, how to research and write them, how to pick an argumentative essay topic, and where to find example essays. So let's get started.

What Is an Argumentative Essay? How Is it Different from Other Kinds of Essays?

There are two basic requirements for any and all essays: to state a claim (a thesis statement) and to support that claim with evidence.

Though every essay is founded on these two ideas, there are several different types of essays, differentiated by the style of the writing, how the writer presents the thesis, and the types of evidence used to support the thesis statement.

Essays can be roughly divided into four different types:

#1: Argumentative #2: Persuasive #3: Expository #4: Analytical

So let's look at each type and what the differences are between them before we focus the rest of our time to argumentative essays.

Argumentative Essay

Argumentative essays are what this article is all about, so let's talk about them first.

An argumentative essay attempts to convince a reader to agree with a particular argument (the writer's thesis statement). The writer takes a firm stand one way or another on a topic and then uses hard evidence to support that stance.

An argumentative essay seeks to prove to the reader that one argument —the writer's argument— is the factually and logically correct one. This means that an argumentative essay must use only evidence-based support to back up a claim , rather than emotional or philosophical reasoning (which is often allowed in other types of essays). Thus, an argumentative essay has a burden of substantiated proof and sources , whereas some other types of essays (namely persuasive essays) do not.

You can write an argumentative essay on any topic, so long as there's room for argument. Generally, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one, so long as you support the argumentative essay with hard evidence.

Example topics of an argumentative essay:

- "Should farmers be allowed to shoot wolves if those wolves injure or kill farm animals?"

- "Should the drinking age be lowered in the United States?"

- "Are alternatives to democracy effective and/or feasible to implement?"

The next three types of essays are not argumentative essays, but you may have written them in school. We're going to cover them so you know what not to do for your argumentative essay.

Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays are similar to argumentative essays, so it can be easy to get them confused. But knowing what makes an argumentative essay different than a persuasive essay can often mean the difference between an excellent grade and an average one.

Persuasive essays seek to persuade a reader to agree with the point of view of the writer, whether that point of view is based on factual evidence or not. The writer has much more flexibility in the evidence they can use, with the ability to use moral, cultural, or opinion-based reasoning as well as factual reasoning to persuade the reader to agree the writer's side of a given issue.

Instead of being forced to use "pure" reason as one would in an argumentative essay, the writer of a persuasive essay can manipulate or appeal to the reader's emotions. So long as the writer attempts to steer the readers into agreeing with the thesis statement, the writer doesn't necessarily need hard evidence in favor of the argument.

Often, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one—the difference is all in the approach and the evidence you present.

Example topics of a persuasive essay:

- "Should children be responsible for their parents' debts?"

- "Should cheating on a test be automatic grounds for expulsion?"

- "How much should sports leagues be held accountable for player injuries and the long-term consequences of those injuries?"

Expository Essay

An expository essay is typically a short essay in which the writer explains an idea, issue, or theme , or discusses the history of a person, place, or idea.

This is typically a fact-forward essay with little argument or opinion one way or the other.

Example topics of an expository essay:

- "The History of the Philadelphia Liberty Bell"

- "The Reasons I Always Wanted to be a Doctor"

- "The Meaning Behind the Colloquialism ‘People in Glass Houses Shouldn't Throw Stones'"

Analytical Essay

An analytical essay seeks to delve into the deeper meaning of a text or work of art, or unpack a complicated idea . These kinds of essays closely interpret a source and look into its meaning by analyzing it at both a macro and micro level.

This type of analysis can be augmented by historical context or other expert or widely-regarded opinions on the subject, but is mainly supported directly through the original source (the piece or art or text being analyzed) .

Example topics of an analytical essay:

- "Victory Gin in Place of Water: The Symbolism Behind Gin as the Only Potable Substance in George Orwell's 1984"

- "Amarna Period Art: The Meaning Behind the Shift from Rigid to Fluid Poses"

- "Adultery During WWII, as Told Through a Series of Letters to and from Soldiers"

There are many different types of essay and, over time, you'll be able to master them all.

A Typical Argumentative Essay Assignment

The average argumentative essay is between three to five pages, and will require at least three or four separate sources with which to back your claims . As for the essay topic , you'll most often be asked to write an argumentative essay in an English class on a "general" topic of your choice, ranging the gamut from science, to history, to literature.

But while the topics of an argumentative essay can span several different fields, the structure of an argumentative essay is always the same: you must support a claim—a claim that can reasonably have multiple sides—using multiple sources and using a standard essay format (which we'll talk about later on).

This is why many argumentative essay topics begin with the word "should," as in:

- "Should all students be required to learn chemistry in high school?"

- "Should children be required to learn a second language?"

- "Should schools or governments be allowed to ban books?"

These topics all have at least two sides of the argument: Yes or no. And you must support the side you choose with evidence as to why your side is the correct one.

But there are also plenty of other ways to frame an argumentative essay as well:

- "Does using social media do more to benefit or harm people?"

- "Does the legal status of artwork or its creators—graffiti and vandalism, pirated media, a creator who's in jail—have an impact on the art itself?"

- "Is or should anyone ever be ‘above the law?'"

Though these are worded differently than the first three, you're still essentially forced to pick between two sides of an issue: yes or no, for or against, benefit or detriment. Though your argument might not fall entirely into one side of the divide or another—for instance, you could claim that social media has positively impacted some aspects of modern life while being a detriment to others—your essay should still support one side of the argument above all. Your final stance would be that overall , social media is beneficial or overall , social media is harmful.

If your argument is one that is mostly text-based or backed by a single source (e.g., "How does Salinger show that Holden Caulfield is an unreliable narrator?" or "Does Gatsby personify the American Dream?"), then it's an analytical essay, rather than an argumentative essay. An argumentative essay will always be focused on more general topics so that you can use multiple sources to back up your claims.

Good Argumentative Essay Topics

So you know the basic idea behind an argumentative essay, but what topic should you write about?

Again, almost always, you'll be asked to write an argumentative essay on a free topic of your choice, or you'll be asked to select between a few given topics . If you're given complete free reign of topics, then it'll be up to you to find an essay topic that no only appeals to you, but that you can turn into an A+ argumentative essay.

What makes a "good" argumentative essay topic depends on both the subject matter and your personal interest —it can be hard to give your best effort on something that bores you to tears! But it can also be near impossible to write an argumentative essay on a topic that has no room for debate.

As we said earlier, a good argumentative essay topic will be one that has the potential to reasonably go in at least two directions—for or against, yes or no, and why . For example, it's pretty hard to write an argumentative essay on whether or not people should be allowed to murder one another—not a whole lot of debate there for most people!—but writing an essay for or against the death penalty has a lot more wiggle room for evidence and argument.

A good topic is also one that can be substantiated through hard evidence and relevant sources . So be sure to pick a topic that other people have studied (or at least studied elements of) so that you can use their data in your argument. For example, if you're arguing that it should be mandatory for all middle school children to play a sport, you might have to apply smaller scientific data points to the larger picture you're trying to justify. There are probably several studies you could cite on the benefits of physical activity and the positive effect structure and teamwork has on young minds, but there's probably no study you could use where a group of scientists put all middle-schoolers in one jurisdiction into a mandatory sports program (since that's probably never happened). So long as your evidence is relevant to your point and you can extrapolate from it to form a larger whole, you can use it as a part of your resource material.

And if you need ideas on where to get started, or just want to see sample argumentative essay topics, then check out these links for hundreds of potential argumentative essay topics.

101 Persuasive (or Argumentative) Essay and Speech Topics

301 Prompts for Argumentative Writing

Top 50 Ideas for Argumentative/Persuasive Essay Writing

[Note: some of these say "persuasive essay topics," but just remember that the same topic can often be used for both a persuasive essay and an argumentative essay; the difference is in your writing style and the evidence you use to support your claims.]

KO! Find that one argumentative essay topic you can absolutely conquer.

Argumentative Essay Format

Argumentative Essays are composed of four main elements:

- A position (your argument)

- Your reasons

- Supporting evidence for those reasons (from reliable sources)

- Counterargument(s) (possible opposing arguments and reasons why those arguments are incorrect)

If you're familiar with essay writing in general, then you're also probably familiar with the five paragraph essay structure . This structure is a simple tool to show how one outlines an essay and breaks it down into its component parts, although it can be expanded into as many paragraphs as you want beyond the core five.

The standard argumentative essay is often 3-5 pages, which will usually mean a lot more than five paragraphs, but your overall structure will look the same as a much shorter essay.

An argumentative essay at its simplest structure will look like:

Paragraph 1: Intro

- Set up the story/problem/issue

- Thesis/claim

Paragraph 2: Support

- Reason #1 claim is correct

- Supporting evidence with sources

Paragraph 3: Support

- Reason #2 claim is correct

Paragraph 4: Counterargument

- Explanation of argument for the other side

- Refutation of opposing argument with supporting evidence

Paragraph 5: Conclusion

- Re-state claim

- Sum up reasons and support of claim from the essay to prove claim is correct

Now let's unpack each of these paragraph types to see how they work (with examples!), what goes into them, and why.

Paragraph 1—Set Up and Claim

Your first task is to introduce the reader to the topic at hand so they'll be prepared for your claim. Give a little background information, set the scene, and give the reader some stakes so that they care about the issue you're going to discuss.

Next, you absolutely must have a position on an argument and make that position clear to the readers. It's not an argumentative essay unless you're arguing for a specific claim, and this claim will be your thesis statement.

Your thesis CANNOT be a mere statement of fact (e.g., "Washington DC is the capital of the United States"). Your thesis must instead be an opinion which can be backed up with evidence and has the potential to be argued against (e.g., "New York should be the capital of the United States").

Paragraphs 2 and 3—Your Evidence

These are your body paragraphs in which you give the reasons why your argument is the best one and back up this reasoning with concrete evidence .

The argument supporting the thesis of an argumentative essay should be one that can be supported by facts and evidence, rather than personal opinion or cultural or religious mores.

For example, if you're arguing that New York should be the new capital of the US, you would have to back up that fact by discussing the factual contrasts between New York and DC in terms of location, population, revenue, and laws. You would then have to talk about the precedents for what makes for a good capital city and why New York fits the bill more than DC does.

Your argument can't simply be that a lot of people think New York is the best city ever and that you agree.

In addition to using concrete evidence, you always want to keep the tone of your essay passionate, but impersonal . Even though you're writing your argument from a single opinion, don't use first person language—"I think," "I feel," "I believe,"—to present your claims. Doing so is repetitive, since by writing the essay you're already telling the audience what you feel, and using first person language weakens your writing voice.

For example,

"I think that Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

"Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

The second statement sounds far stronger and more analytical.

Paragraph 4—Argument for the Other Side and Refutation

Even without a counter argument, you can make a pretty persuasive claim, but a counterargument will round out your essay into one that is much more persuasive and substantial.

By anticipating an argument against your claim and taking the initiative to counter it, you're allowing yourself to get ahead of the game. This way, you show that you've given great thought to all sides of the issue before choosing your position, and you demonstrate in multiple ways how yours is the more reasoned and supported side.

Paragraph 5—Conclusion

This paragraph is where you re-state your argument and summarize why it's the best claim.

Briefly touch on your supporting evidence and voila! A finished argumentative essay.

Your essay should have just as awesome a skeleton as this plesiosaur does. (In other words: a ridiculously awesome skeleton)

Argumentative Essay Example: 5-Paragraph Style

It always helps to have an example to learn from. I've written a full 5-paragraph argumentative essay here. Look at how I state my thesis in paragraph 1, give supporting evidence in paragraphs 2 and 3, address a counterargument in paragraph 4, and conclude in paragraph 5.

Topic: Is it possible to maintain conflicting loyalties?

Paragraph 1

It is almost impossible to go through life without encountering a situation where your loyalties to different people or causes come into conflict with each other. Maybe you have a loving relationship with your sister, but she disagrees with your decision to join the army, or you find yourself torn between your cultural beliefs and your scientific ones. These conflicting loyalties can often be maintained for a time, but as examples from both history and psychological theory illustrate, sooner or later, people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever.

The first two sentences set the scene and give some hypothetical examples and stakes for the reader to care about.

The third sentence finishes off the intro with the thesis statement, making very clear how the author stands on the issue ("people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever." )

Paragraphs 2 and 3

Psychological theory states that human beings are not equipped to maintain conflicting loyalties indefinitely and that attempting to do so leads to a state called "cognitive dissonance." Cognitive dissonance theory is the psychological idea that people undergo tremendous mental stress or anxiety when holding contradictory beliefs, values, or loyalties (Festinger, 1957). Even if human beings initially hold a conflicting loyalty, they will do their best to find a mental equilibrium by making a choice between those loyalties—stay stalwart to a belief system or change their beliefs. One of the earliest formal examples of cognitive dissonance theory comes from Leon Festinger's When Prophesy Fails . Members of an apocalyptic cult are told that the end of the world will occur on a specific date and that they alone will be spared the Earth's destruction. When that day comes and goes with no apocalypse, the cult members face a cognitive dissonance between what they see and what they've been led to believe (Festinger, 1956). Some choose to believe that the cult's beliefs are still correct, but that the Earth was simply spared from destruction by mercy, while others choose to believe that they were lied to and that the cult was fraudulent all along. Both beliefs cannot be correct at the same time, and so the cult members are forced to make their choice.

But even when conflicting loyalties can lead to potentially physical, rather than just mental, consequences, people will always make a choice to fall on one side or other of a dividing line. Take, for instance, Nicolaus Copernicus, a man born and raised in Catholic Poland (and educated in Catholic Italy). Though the Catholic church dictated specific scientific teachings, Copernicus' loyalty to his own observations and scientific evidence won out over his loyalty to his country's government and belief system. When he published his heliocentric model of the solar system--in opposition to the geocentric model that had been widely accepted for hundreds of years (Hannam, 2011)-- Copernicus was making a choice between his loyalties. In an attempt t o maintain his fealty both to the established system and to what he believed, h e sat on his findings for a number of years (Fantoli, 1994). But, ultimately, Copernicus made the choice to side with his beliefs and observations above all and published his work for the world to see (even though, in doing so, he risked both his reputation and personal freedoms).

These two paragraphs provide the reasons why the author supports the main argument and uses substantiated sources to back those reasons.

The paragraph on cognitive dissonance theory gives both broad supporting evidence and more narrow, detailed supporting evidence to show why the thesis statement is correct not just anecdotally but also scientifically and psychologically. First, we see why people in general have a difficult time accepting conflicting loyalties and desires and then how this applies to individuals through the example of the cult members from the Dr. Festinger's research.

The next paragraph continues to use more detailed examples from history to provide further evidence of why the thesis that people cannot indefinitely maintain conflicting loyalties is true.

Paragraph 4

Some will claim that it is possible to maintain conflicting beliefs or loyalties permanently, but this is often more a matter of people deluding themselves and still making a choice for one side or the other, rather than truly maintaining loyalty to both sides equally. For example, Lancelot du Lac typifies a person who claims to maintain a balanced loyalty between to two parties, but his attempt to do so fails (as all attempts to permanently maintain conflicting loyalties must). Lancelot tells himself and others that he is equally devoted to both King Arthur and his court and to being Queen Guinevere's knight (Malory, 2008). But he can neither be in two places at once to protect both the king and queen, nor can he help but let his romantic feelings for the queen to interfere with his duties to the king and the kingdom. Ultimately, he and Queen Guinevere give into their feelings for one another and Lancelot—though he denies it—chooses his loyalty to her over his loyalty to Arthur. This decision plunges the kingdom into a civil war, ages Lancelot prematurely, and ultimately leads to Camelot's ruin (Raabe, 1987). Though Lancelot claimed to have been loyal to both the king and the queen, this loyalty was ultimately in conflict, and he could not maintain it.

Here we have the acknowledgement of a potential counter-argument and the evidence as to why it isn't true.

The argument is that some people (or literary characters) have asserted that they give equal weight to their conflicting loyalties. The refutation is that, though some may claim to be able to maintain conflicting loyalties, they're either lying to others or deceiving themselves. The paragraph shows why this is true by providing an example of this in action.

Paragraph 5

Whether it be through literature or history, time and time again, people demonstrate the challenges of trying to manage conflicting loyalties and the inevitable consequences of doing so. Though belief systems are malleable and will often change over time, it is not possible to maintain two mutually exclusive loyalties or beliefs at once. In the end, people always make a choice, and loyalty for one party or one side of an issue will always trump loyalty to the other.

The concluding paragraph summarizes the essay, touches on the evidence presented, and re-states the thesis statement.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: 8 Steps

Writing the best argumentative essay is all about the preparation, so let's talk steps:

#1: Preliminary Research

If you have the option to pick your own argumentative essay topic (which you most likely will), then choose one or two topics you find the most intriguing or that you have a vested interest in and do some preliminary research on both sides of the debate.

Do an open internet search just to see what the general chatter is on the topic and what the research trends are.

Did your preliminary reading influence you to pick a side or change your side? Without diving into all the scholarly articles at length, do you believe there's enough evidence to support your claim? Have there been scientific studies? Experiments? Does a noted scholar in the field agree with you? If not, you may need to pick another topic or side of the argument to support.

#2: Pick Your Side and Form Your Thesis

Now's the time to pick the side of the argument you feel you can support the best and summarize your main point into your thesis statement.

Your thesis will be the basis of your entire essay, so make sure you know which side you're on, that you've stated it clearly, and that you stick by your argument throughout the entire essay .

#3: Heavy-Duty Research Time

You've taken a gander at what the internet at large has to say on your argument, but now's the time to actually read those sources and take notes.

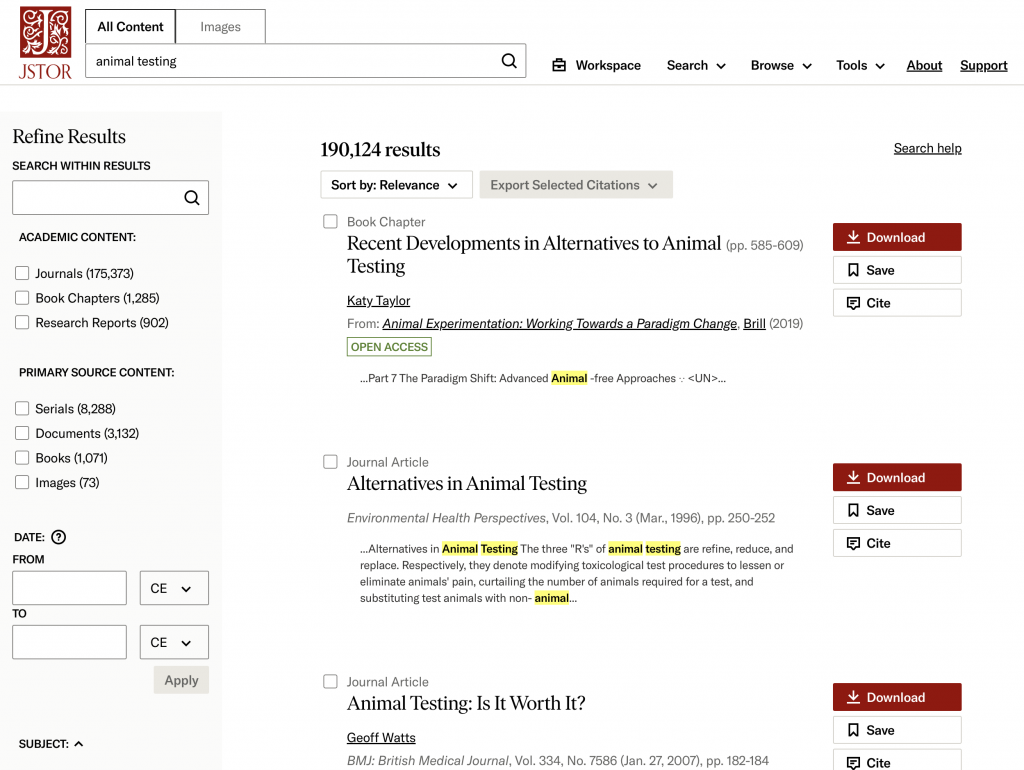

Check scholarly journals online at Google Scholar , the Directory of Open Access Journals , or JStor . You can also search individual university or school libraries and websites to see what kinds of academic articles you can access for free. Keep track of your important quotes and page numbers and put them somewhere that's easy to find later.

And don't forget to check your school or local libraries as well!

#4: Outline

Follow the five-paragraph outline structure from the previous section.

Fill in your topic, your reasons, and your supporting evidence into each of the categories.

Before you begin to flesh out the essay, take a look at what you've got. Is your thesis statement in the first paragraph? Is it clear? Is your argument logical? Does your supporting evidence support your reasoning?

By outlining your essay, you streamline your process and take care of any logic gaps before you dive headfirst into the writing. This will save you a lot of grief later on if you need to change your sources or your structure, so don't get too trigger-happy and skip this step.

Now that you've laid out exactly what you'll need for your essay and where, it's time to fill in all the gaps by writing it out.

Take it one step at a time and expand your ideas into complete sentences and substantiated claims. It may feel daunting to turn an outline into a complete draft, but just remember that you've already laid out all the groundwork; now you're just filling in the gaps.

If you have the time before deadline, give yourself a day or two (or even just an hour!) away from your essay . Looking it over with fresh eyes will allow you to see errors, both minor and major, that you likely would have missed had you tried to edit when it was still raw.

Take a first pass over the entire essay and try your best to ignore any minor spelling or grammar mistakes—you're just looking at the big picture right now. Does it make sense as a whole? Did the essay succeed in making an argument and backing that argument up logically? (Do you feel persuaded?)

If not, go back and make notes so that you can fix it for your final draft.

Once you've made your revisions to the overall structure, mark all your small errors and grammar problems so you can fix them in the next draft.

#7: Final Draft

Use the notes you made on the rough draft and go in and hack and smooth away until you're satisfied with the final result.

A checklist for your final draft:

- Formatting is correct according to your teacher's standards

- No errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation

- Essay is the right length and size for the assignment

- The argument is present, consistent, and concise

- Each reason is supported by relevant evidence

- The essay makes sense overall

#8: Celebrate!

Once you've brought that final draft to a perfect polish and turned in your assignment, you're done! Go you!

Be prepared and ♪ you'll never go hungry again ♪, *cough*, or struggle with your argumentative essay-writing again. (Walt Disney Studios)

Good Examples of Argumentative Essays Online

Theory is all well and good, but examples are key. Just to get you started on what a fully-fleshed out argumentative essay looks like, let's see some examples in action.

Check out these two argumentative essay examples on the use of landmines and freons (and note the excellent use of concrete sources to back up their arguments!).

The Use of Landmines

A Shattered Sky

The Take-Aways: Keys to Writing an Argumentative Essay

At first, writing an argumentative essay may seem like a monstrous hurdle to overcome, but with the proper preparation and understanding, you'll be able to knock yours out of the park.

Remember the differences between a persuasive essay and an argumentative one, make sure your thesis is clear, and double-check that your supporting evidence is both relevant to your point and well-sourced . Pick your topic, do your research, make your outline, and fill in the gaps. Before you know it, you'll have yourself an A+ argumentative essay there, my friend.

What's Next?

Now you know the ins and outs of an argumentative essay, but how comfortable are you writing in other styles? Learn more about the four writing styles and when it makes sense to use each .

Understand how to make an argument, but still having trouble organizing your thoughts? Check out our guide to three popular essay formats and choose which one is right for you.

Ready to make your case, but not sure what to write about? We've created a list of 50 potential argumentative essay topics to spark your imagination.

Courtney scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT in high school and went on to graduate from Stanford University with a degree in Cultural and Social Anthropology. She is passionate about bringing education and the tools to succeed to students from all backgrounds and walks of life, as she believes open education is one of the great societal equalizers. She has years of tutoring experience and writes creative works in her free time.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

English 102: Composition

- Critical Reading

- Annotated Bibliography

- Toulmin - Formal Argument

- Presentation Tools

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Presentation Tools >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2023 4:44 PM

- URL: https://bowiestate.libguides.com/engl_102

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.2: Generating Ideas for an Argument Analysis Paper

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 56613

.jpg?revision=2)

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Media Alternative

Listen to an audio version of this page (4 min, 18 sec):

Here are some questions to consider each in relation to the argument you are analyzing. Unless your teacher specifically asks you to cover all of these questions, you will eventually want to pick and choose what you discuss in your argument analysis essay. (The essay would likely read like a list rather than a cohesive group of connected paragraphs if you did include everything.) However, it will probably help you to consider each of these before you start your rough draft to see what might be most important or interesting to focus on in your analysis.

Analyzing the Ideas

Chapter 2: Reading to Figure out the Argument describes how to map out the core ideas in the argument you are analyzing in order to write a clear summary as part of your analysis. Here are some specific questions to brainstorm on:

- What are the key claims?

- What are the reasons given for each of these key claims?

- Are the reasons ideas that are generally agreed upon, or do any of these reasons need additional support?

- What kind of evidence does the writer provide, and how convincing is it?

- Does the reader make assumptions that should be questioned or supported?

- What limits does the writer place on the key claims?

- Can we imagine exceptions or limits that the writer has not noted?

- What counterarguments, if any, does the writer refer to?

- Does the writer describe any counterarguments fairly?

- Does the writer miss any important counterarguments?

- How does the writer respond to any counterarguments mentioned?

- Are the responses convincing? Why or why not?

- Are there any places where the writer's meaning is unclear?

- Are there any fallacies or problems with the logic ?

Analyzing the Emotional Appeals

Chapter 8: How Arguments Appeal to Emotion describes what to look for. Here are some specific questions:

- How would you describe the tone of the argument? Does the argument change tone at any point, and if so, why?

- How does the argument establish a sense that it is important, urgent, relevant or somehow worth reading?

- Does the argument choose words with particular emotional connotations to further the argument?

- Does the argument use powerful examples to affect readers' emotions?

- Does the argument appeal to readers’ self-interest?

- Does the argument appeal to the readers’ sense of identity?

- Will different groups of readers likely respond to the argument in different ways?

Analyzing Appeals to Trust and Connection

Chapter 9: How Arguments Establish Trust and Connection describes the many ways an argument might do this. Here are some questions to brainstorm on:

- What makes the writer qualified to make the argument?

- Does the writer have credentials or professional training which make them an authority?

- Does the writer point to relevant personal experience?

- How does the writer show goodwill and respect toward readers?

- How does the writer attempt to convince us of their good moral character?

- Does the argument appeal to any particular shared values to establish trust?

- How does the writer try to create the impression that they are reasonable?

- Do they succeed in appearing reasonable?

- How does the argument seem to imagine the relationship between writer and reader?

- Does the writer take a more formal or informal approach to creating trust?

- To what extent does the argument depend on a shared sense of identity for trust?

- Does the argument attempt to undermine trust in an opposing group?

- What point of view ("I," "we," "you," or an impersonal point of view) does the writer use most frequently?

- How does this point of view affect the reader?

- When does the writer switch to a different point of view, and why?

7. Argument/Research

2. argumentative writing.

As we have discussed already, argument requires discussion of two (or more) opposing ideas. It doesn’t mean bashing your opponent because he/she has differing views. A successful argument leads somewhere: there is compromise, agreement, resolution. Today, too often, argument leads no where. Both sides are stagnant and nothing is accomplished. Can you think of any cases where common arguments seem to be going no where?

I like to think that argument can be designed to convince an audience that your side of the issue is the best side. Then, with popular opinion behind you, your argument can gain strength and perhaps convince your opponent to at least consider some kind of compromise (moving toward resolution). Therefore, I like to use traditional argumentative format, an organization technique that has been used for thousands of years (though not so much, anymore, it seems, with the weaknesses in today’s modern argument). I will outline the traditional format below. I suggest you use it in whole or in part to help ensure that you are open-minded yet assertive in your convictions that your side of the argument is the right side.

Introduction

- Exordium: This is the section of your introduction that first grabs your readers’ attention. Think about speeches. How do they often begin? The speaker will often use some kind of joke to attract the listeners before moving into the topic of the speech. Although this doesn’t work well for serious argument (I wouldn’t start an essay on the moral issues of euthanasia with a joke), there are many things you can do in the opening to attract the attention of your reader. Some kind of intriguing story related to the topic (a summary of a specific case on euthanasia), or some personal background showing that you have a vested interest in the topic: you care. This should not be a long section, perhaps one paragraph giving the reader a glimpse into the humanity of the topic and the writer.

- Exposition: You are the expert on this topic (you’ve done the research and experienced the situation). But your reader may not have a strong background. You need to take a moment (or paragraph) to define important issues- give background on what the topic is and why it’s important for the reader. Inform the reader with a brief statement of backgrounds. Again, this should not be overly long- a paragraph, again, will suffice.

- Thesis: A lot of times, separating a thesis from the rest of the opening can emphasize what direction the paper is going in. Whatever the case, you need to identify early what side of the argument you are on: Euthanasia is a process that goes against the moral fibers of society and should not be allowed in a civilized world (your reader clearly identifies with what you are writing about. Make it clear- you support a specific side. If your thesis is “wishy-washy” then your argument will be as well.

- Plan of Proof: You’ve just given an extended introduction (remember, most of your other intros have been one short paragraph). It might be a good idea to have a “transitional” paragraph, leading your reader into the text of your paper. To do this, you could use a plan of proof- how you plan to go about proving what you say is valid. It’s kind of an extended essay map, looking at how the essay is organized. It helps the reader decide (hopefully) that something worthwhile will be included in this essay.

- Confirmation: This is the bulk of your essay. The reasons why you feel you have a strong argument. You need to have about three valid reasons for supporting your argument. Each of those reasons should be a separate paragraph in which you explain why you feel your side is right. For the euthanasia issue, one reason might be a religious connection: as humans, we answer to a higher being. Another might be scientific: where there’s life there’s hope, kinda thing. And a third might be legal: it’s against the law. So each of those reasons would be a separate paragraph, with your thoughts and commentary, borrowed info from professional sources and data supporting what you say.

- Refutation: There is nothing stronger for weakening an opponent’s argument than showing the weaknesses. Look at what your opponent is saying about the argument. What are his/her confirming points? Find weaknesses in logic, truth or validity in those statements and point them out in your essay. Show why you feel the opponent is wrong. Again, don’t just make flat statements. Develop it into a paragraph or two proving that your opponent is wrong in his/her viewpoints. Don’t argue against your opponent- argue against his/her viewpoint. It’s not illegal in this country to disagree. But maybe it’s not a good disagreement.

- Concession: Because your opponent is human and has probably considered his/her argument very thoroughly, chances are you cannot refute everything he/she says. One of the opponent’s views on euthanasia is that patients often suffer during extended phases of terminal illness. It’s pretty hard to refute that. If you try, you are giving your opponent strength. So concede. “Yes, patients do suffer, as my opponent points out. But killing them is not the answer. We need stronger ways to control pain.” This will show that you are open-minded, that you have considered both sides of the argument, that you haven’t just brushed your opponent’s viewpoints aside. This is a strong tool in attracting the undecided reader. Be careful though: if your concession is too strong, perhaps you are on the wrong side of the argument.

- Recapitulation: Perhaps you’ve noticed that this essay is probably going to be somewhat longer than the others. You may also remember that I’ve always tried to avoid using summary in short essays. A conclusion is much stronger, usually. Here, however, you may want to spend some time reviewing the strong points of your argument. If you’ve spent the past few paragraphs refuting your opponent’s points or conceding one or two, then you need to return for a moment and remind your reader of the strong points for your argument in a brief summary.

- Peroration: Finally as for your reader’s support. Chances are, your opponent will not be convinced that easily. But all those folks “on the fence” are dying to make the right choice. Ask them to help you by making the right choice and choosing your side. Writing to their legislators is a big concluding statement. Asking for votes, if in an election, is obvious. Asking for financial support is a biggie. But here, probably just asking your reader to consider your ideas and make the right choice will be sufficient.

You don’t have to use this format verbatim. But please think about being open-minded, considering both sides of the argument, and being assertive in choosing your side. Remember how valuable additional support is in using research. Turn to the Instructions section of this module for information on the argumentative assignment. You can find additional information on argument at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/englishcomp1v2xmaster/

- Authored by : Jeff Meyers. Provided by : Clinton Community College. License : CC BY: Attribution

Privacy Policy

- SAT BootCamp

- SAT MasterClass

- SAT Private Tutoring

- SAT Proctored Practice Test

- ACT Private Tutoring

- Academic Subjects

- College Essay Workshop

- Academic Writing Workshop

- AP English FRQ BootCamp

- 1:1 College Essay Help

- Online Instruction

- Free Resources

12 Essential Steps for Writing an Argumentative Essay (with 10 example essays)

Bonus Material: 10 complete example essays

Writing an essay can often feel like a Herculean task. How do you go from a prompt… to pages of beautifully-written and clearly-supported writing?

This 12-step method is for students who want to write a great essay that makes a clear argument.

In fact, using the strategies from this post, in just 88 minutes, one of our students revised her C+ draft to an A.

If you’re interested in learning how to write awesome argumentative essays and improve your writing grades, this post will teach you exactly how to do it.

First, grab our download so you can follow along with the complete examples.

Then keep reading to see all 12 essential steps to writing a great essay.

Download 10 example essays

Why you need to have a plan

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing is to just dive in haphazardly without a plan.

Writing is a bit like cooking. If you’re making a meal, would you start throwing ingredients at random into a pot? Probably not!

Instead, you’d probably start by thinking about what you want to cook. Then you’d gather the ingredients, and go to the store if you don’t already have them in your kitchen. Then you’d follow a recipe, step by step, to make your meal.

Here’s our 12-step recipe for writing a great argumentative essay:

- Pick a topic

- Choose your research sources

- Read your sources and take notes

- Create a thesis statement

- Choose three main arguments to support your thesis statement —now you have a skeleton outline

- Populate your outline with the research that supports each argument

- Do more research if necessary

- Add your own analysis

- Add transitions and concluding sentences to each paragraph

- Write an introduction and conclusion for your essay

- Add citations and bibliography

Grab our download to see the complete example at every stage, along with 9 great student essays. Then let’s go through the steps together and write an A+ essay!

1. Pick a topic

Sometimes you might be assigned a topic by your instructor, but often you’ll have to come up with your own idea!

If you don’t pick the right topic, you can be setting yourself up for failure.

Be careful that your topic is something that’s actually arguable —it has more than one side. Check out our carefully-vetted list of 99 topic ideas .

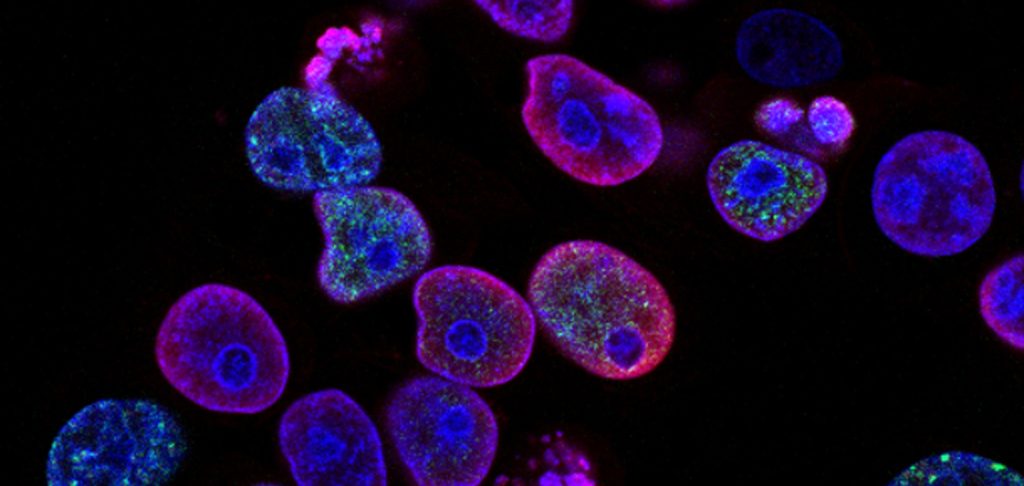

Let’s pick the topic of laboratory animals . Our question is should animals be used for testing and research ?

Download our set of 10 great example essays to jump to the finished version of this essay.

2. Choose your research sources

One of the big differences between the way an academic argumentative essay and the version of the assignment that you may have done in elementary school is that for an academic argumentative essay, we need to support our arguments with evidence .

Where do we get that evidence?

Let’s be honest, we all are likely to start with Google and Wikipedia.

Now, Wikipedia can be a useful starting place if you don’t know very much about a topic, but don’t use Wikipedia as your main source of evidence for your essay.

Instead, look for reputable sources that you can show to your readers as proof of your arguments. It can be helpful to read some sources from either side of your issue.

Look for recently-published sources (within the last 20 years), unless there’s a specific reason to do otherwise.

Good places to look for sources are:

- Books published by academic presses

- Academic journals

- Academic databases like JSTOR and EBSCO

- Nationally-published newspapers and magazines like The New York Times or The Atlantic

- Websites and publications of national institutions like the NIH

- Websites and publications of universities

Some of these sources are typically behind a paywall. This can be frustrating when you’re a middle-school or high-school student.

However, there are often ways to get access to these sources. Librarians (at your school library or local public library) can be fantastic resources, and they can often help you find a copy of the article or book you want to read. In particular, librarians can help you use Interlibrary Loan to order books or journals to your local library!

More and more scientists and other researchers are trying to publish their articles for free online, in order to encourage the free exchange of knowledge. Check out respected open-access platforms like arxiv.org and PLOS ONE .

How do you find these sources?

If you have access to an academic database like JSTOR or EBSCO , that’s a great place to start.

Everyone can use Google Scholar to search for articles. This is a powerful tool and highly recommended!

Of course, if there’s a term you come across that you don’t recognize, you can always just Google it!

How many sources do you need? That depends on the length of your essay and on the assignment. If your instructor doesn’t give you any other guidance, assume that you should have at least three good sources.

For our topic of animal research, here’s a few sources that we could assemble:

Geoff Watts. “Animal Testing: Is It Worth It?” BMJ: British Medical Journal , Jan. 27, 2007, Vol. 334, No. 7586 (Jan. 27, 2007), pp. 182-184.

Kim Bartel Sheehan and Joonghwa Lee. “What’s Cruel About Cruelty Free: An Exploration of Consumers, Moral Heuristics, and Public Policy.” Journal of Animal Ethics , Vol. 4, No. 2 (Fall 2014), pp. 1-15.

Justin Goodman, Alka Chandna and Katherine Roe. “Trends in animal use at US research facilities.” Journal of Medical Ethics , July 2015, Vol. 41, No. 7 (July 2015), pp. 567-569.

Katy Taylor. “Recent Developments in Alternatives to Animal Testing.” In Animal Experimentation: Working Towards a Paradigm Change . Brill 2019.

Thomas Hartung. “Research and Testing Without Animals: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Heading?” In Animal Experimentation: Working Towards a Paradigm Change . Brill 2019.

Bonus: download 10 example essays now .

3. Read your sources and take notes

Once you have a nice pile of sources, it’s time to read them!

As we read, we want to take notes that will be useful to us later as we write our essay.

We want to be careful to keep the source’s ideas separate from our own ideas . Come up with a system to clearly mark the difference as you’re taking notes: use different colors, or use little arrows to represent the ideas that are yours and not the source’s ideas.

We can use this structure to keep notes in an organized way:

Download a template for these research notes here .

For our topic of animal research, our notes might look something like this:

Grab our download to read the rest of the notes and see more examples of how to do thoughtful research!

4. Create a thesis

What major themes did you find in your reading? What did you find most interesting or convincing?

Now is the point when you need to pick a side on your topic, if you haven’t already done so. Now that you’ve read more about the issue, what do you think? Write down your position on the issue:

Animal testing is necessary but should be reduced.

Next, it’s time to add more detail to your thesis. What reasons do you have to support that position? Add those to your sentence.

Animal testing is necessary but should be reduced by eliminating testing for cosmetics, ensuring that any testing is scientifically sound, and replacing animal models with other methods as much as possible.

Add qualifiers to refine your position. Are there situations in which your position would not apply? Or are there other conditions that need to be met?

For our topic of animal research, our final thesis statement (with lead-in) might look something like this:

The argument: Animal testing and research should not be abolished, as doing so would upend important medical research and substance testing. However, scientific advances mean that in many situations animal testing can be replaced by other methods that not only avoid the ethical problems of animal testing, but also are less costly and more accurate. Governments and other regulatory bodies should further regulate animal testing to outlaw testing for cosmetics and other recreational products, ensure that the tests conducted are both necessary and scientifically rigorous, and encourage the replacement of animal use with other methods whenever possible.

The highlighted bit at the end is the thesis statement, but the lead-in is useful to help us set up the argument—and having it there already will make writing our introduction easier!

The thesis statement is the single most important sentence of your essay. Without a strong thesis, there’s no chance of writing a great essay. Read more about it here .

See how nine real students wrote great thesis statements in 9 example essays now.

5. Create three supporting arguments

Think of three good arguments why your position is true. We’re going to make each one into a body paragraph of your essay.

For now, write them out as 1–2 sentences. These will be topic sentences for each body paragraph.

For our essay about animal testing, it might look like this:

Supporting argument #1: For ethical reasons, animal testing should not be allowed for cosmetics and recreational products.

Supporting argument #2: The tests that are conducted with animals should be both necessary (for the greater good) and scientifically rigorous—which isn’t always the case currently. This should be regulated by governments and institutions.

Supporting argument #3: Governments and institutions should do more to encourage the replacement of animal testing with other methods.

Optional: Find a counterargument and respond to it

Think of a potential counterargument to your position. Consider writing a fourth paragraph anticipating this counterargument, or find a way to include it in your other body paragraphs.

For our essay, that might be:

Possible counterargument: Animal testing is unethical and should not be used in any circumstances.

Response to the counterargument: Animal testing is deeply entrenched in many research projects and medical procedures. Abruptly ceasing animal testing would upend the scientific and medical communities. But there are many ways that animal testing could be reduced.

With these three arguments, a counterargument, and a thesis, we now have a skeleton outline! See each step of this essay in full in our handy download .

6. Start populating your outline with the evidence you found in your research

Look through your research. What did you find that would support each of your three arguments?

Copy and paste those quotes or paraphrases into the outline. Make sure that each one is annotated so that you know which source it came from!

Ideally you already started thinking about these sources when you were doing your research—that’s the ideas in the rightmost column of our research template. Use this stuff too!

A good rule of thumb would be to use at least three pieces of evidence per body paragraph.

Think about in what order it would make most sense to present your points. Rearrange your quotes accordingly! As you reorder them, feel free to start adding short sentences indicating the flow of ideas .

For our essay about animal testing, part of our populated outline might look something like:

Argument #1: For ethical reasons, animal testing should not be allowed for cosmetics and recreational products.

Lots of animals are used for testing and research.

In the US, about 22 million animals were used annually in the early 1990s, mostly rodents (BMJ 1993, 1020).

But there are ethical problems with using animals in laboratory settings. Opinions about the divide between humans and animals might be shifting.

McIsaac refers to “the essential moral dilemma: how to balance the welfare of humans with the welfare of other species” (Hubel, McIsaac 29).

The fundamental legal texts used to justify animal use in biomedical research were created after WWII, and drew a clear line between experiments on animals and on humans. The Nuremburg Code states that “the experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation and a knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study that the anticipated results will justify the performance of the experiment” (Ferrari, 197). The 1964 Declaration of the World Medical Association on the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (known as the Helsinki Declaration) states that “Medical research involving human subjects must conform to generally accepted scientific principles, be based on a thorough knowledge of the scientific literature, other relevant sources of information, and adequate laboratory and, as appropriate, animal experimentation. The welfare of animals used for research must be respected” (Ferrari, 197).

→ Context? The Nuremberg Code is a set of ethical research principles, developed in 1947 in the wake of Nazi atrocities during WWII, specifically the inhumane and often fatal experimentation on human subjects without consent.

“Since the 1970s, the animal-rights movement has challenged the use of animals in modern Western society by rejecting the idea of dominion of human beings over nature and animals and stressing the intrinsic value and rights of individual animals” (van Roten, 539, referencing works by Singer, Clark, Regan, and Jasper and Nelkin).

“The old (animal) model simply does not fully meet the needs of scientific and economic progress; it fails in cost, speed, level of detail of understanding, and human relevance. On top of this, animal experimentation lacks acceptance by an ethically evolving society” (Hartung, 682).

Knight’s article summarizes negative impacts on laboratory animals—invasive procedures, stress, pain, and death (Knight, 333). These aren’t very widely or clearly reported (Knight, 333). → Reading about these definitely produces an emotional reaction—they sound bad.

Given this context, it makes sense to ban animal testing in situations where it’s just for recreational products like cosmetics.

Fortunately, animal testing for cosmetics is less common than we might think.

A Gallup poll published in 1990 found that 14% of people thought that the most frequent reason for using animals to test cosmetics for safety—but figures from the UK Home Office in 1991 found that less than 1% of animals were used for tests for cosmetics and toiletries (BMJ 1993, 1019). → So in the early 1990s there was a big difference between what people thought was happening and what actually was happening!

But it still happens, and there are very few regulations of it (apart from in the EU).

Because there are many definitions of the phrase “cruelty-free,” many companies “can (and do) use the term when the product or its ingredients were indeed tested on animals” (Sheehan and Lee, 1).

The authors compare “cruelty-free” to the term “fair trade.” There is an independent inspection and certification group (Flo-Cert) that reviews products labeled as “fair trade,” but there’s no analogous process for “cruelty-free” (Sheehan and Lee, 2). → So anyone can just put that label on a product? Apparently, apart from in the European Union. That seems really easy to abuse for marketing purposes.

Companies can also hire outside firms to test products and ingredients on animals (Sheehan and Lee, 3).

Animal testing for recreational, non-medical purposes should be banned, like it is in the EU.

Download the full example outline here .

7. Do more research if necessary

Occasionally you might realize that there’s a hole in your research, and you don’t have enough evidence to support one of your points.

In this situation, either change your argument to fit the evidence that you do have, or do a bit more research to fill the hole!

For example, looking at our outline for argument #1 for our essay on animal testing, it’s clear that this paragraph is missing a small but crucial bit of evidence—a reference to this specific ban on animal testing for cosmetics in Europe. Time for a bit more research!

A visit to the official website of the European Commission yields a copy of the law, which we can add to our populated outline:

“The cosmetics directive provides the regulatory framework for the phasing out of animal testing for cosmetics purposes. Specifically, it establishes (1) a testing ban – prohibition to test finished cosmetic products and cosmetic ingredients on animals, and (2) a marketing ban – prohibition to market finished cosmetic products and ingredients in the EU which were tested on animals. The same provisions are contained in the cosmetics regulation , which replaced the cosmetics directive as of 11 July 2013. The testing ban on finished cosmetic products applies since 11 September 2004. The testing ban on ingredients or combination of ingredients applies since 11 March 2009. The marketing ban applies since 11 March 2009 for all human health effects with the exception of repeated-dose toxicity, reproductive toxicity, and toxicokinetics. For these specific health effects, the marketing ban applies since 11 March 2013, irrespective of the availability of alternative non-animal tests.” (website of the European Commission, “Ban on animal testing”)

Alright, now this supporting argument has the necessary ingredients!

You don’t need to use all of the evidence that you found in your research. In fact, you probably won’t use all of it!

This part of the writing process requires you to think critically about your arguments and what evidence is relevant to your points .

8. Add your own analysis and synthesis of these points

Once you’ve organized your evidence and decided what you want to use for your essay, now you get to start adding your own analysis!

You may have already started synthesizing and evaluating your sources when you were doing your research (the stuff on the right-hand side of our template). This gives you a great starting place!

For each piece of evidence, follow this formula:

- Context and transitions: introduce your piece of evidence and any relevant background info and signal the logical flow of ideas

- Reproduce the paraphrase or direct quote (with citation )

- Explanation : explain what the quote/paraphrase means in your own words

- Analysis : analyze how this piece of evidence proves your thesis

- Relate it back to the thesis: don’t forget to relate this point back to your overarching thesis!

If you follow this fool-proof formula as you write, you will create clear, well-evidenced arguments.

As you get more experienced, you might stray a bit from the formula—but a good essay will always intermix evidence with explanation and analysis, and will always contain signposts back to the thesis throughout.

For our essay about animal testing, our first body paragraph might look like:

Every year, millions of animals—mostly rodents—are used for testing and research (BMJ 1993, 1020) . This testing poses an ethical dilemma: “how to balance the welfare of humans with the welfare of other species” (Hubel, McIsaac 29) . Many of the fundamental legal tests that are used to justify animal use in biomedical research were created in wake of the horrors of World War II, when the Nazi regime engaged in terrible experimentation on their human prisoners. In response to these atrocities, philosophers and lawmakers drew a clear line between experimenting on humans without consent and experimenting on (non-human) animals. For example, the 1947 Nuremberg Code stated that “the experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation and a knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study that the anticipated results will justify the performance of the experiment” (Ferrari, 197) . Created two years after the war, the code established a set of ethical research principles to demarcate ethical differences between animals and humans, clarifying differences between Nazi atrocities and more everyday research practices. However, in the following decades, the animal-rights movement has challenged the philosophical boundaries between humans and animals and questioned humanity’s right to exert dominion over animals (van Roten, 539, referencing works by Singer, Clark, Regan, and Jasper and Nelkin) . These concerns are not without justification, as animals used in laboratories are subject to invasive procedures, stress, pain, and death (Knight, 333) . Indeed, reading detailed descriptions of this research can be difficult to stomach . In light of this, while some animal testing that contributes to vital medical research and ultimately saves millions of lives may be ethically justified, animal testing that is purely for recreational purposes like cosmetics cannot be ethically justified . Fortunately, animal testing for cosmetics is less common than we might think . In 1990, a poll found that 14% of people in the UK thought that the most frequent reason for using animals to test cosmetics for safety—but actual figures were less than 1% (BMJ 1993, 1019) . Unfortunately, animal testing for cosmetics is not subject to very much regulation . In particular, companies can use the phrase “cruelty-free” to mean just about anything, and many companies “can (and do) use the term when the product or its ingredients were indeed tested on animals” (Sheehan and Lee, 1) . Unlike the term “fair trade,” which has an independent inspection and certification group (Flo-Cert) that reviews products using the label, there’s no analogous process for “cruelty-free” (Sheehan and Lee, 2) . Without regulation, the term is regularly abused by marketers . Companies can also hire outside firms to test products and ingredients on animals and thereby pass the blame (Sheehan and Lee, 3) . Consumers trying to avoid products tested on animals are frequently tricked . Greater regulation of terms would help, but the only way to end this kind of deceit will be to ban animal testing for recreational, non-medical purposes . The European Union is the only governmental body yet to accomplish this . In a series of regulations, the EU first banned testing finished cosmetic products (2004), then testing ingredients or marketing products which were tested on animals (2009); exceptions for specific health effects ended in 2013 (website of the European Commission, “Ban on animal testing”) . The result is that the EU bans testing cosmetic ingredients or finished cosmetic products on animals, as well as marketing any cosmetic ingredients and products which were tested on animals elsewhere (Regulation 1223/2009/EU, known as the “Cosmetics Regulation”) . The rest of the world should follow this example and ban animal testing on cosmetic ingredients and products, which do not contribute significantly to the greater good and therefore cannot outweigh the cost to animal lives .

Edit down the quotes/paraphrases as you go. In many cases, you might copy out a great long quote from a source…but only end up using a few words of it as a direct quote, or you might only paraphrase it!

There were several good quotes in our previous step that just didn’t end up fitting here. That’s fine!

Take a look at the words and phrases highlighted in red. Notice how sometimes a single word can help to provide necessary context and create a logical transition for a new idea. Don’t forget the transitions! These words and phrases are essential to good writing.

The end of the paragraph should very clearly tie back to the thesis statement.

As you write, consider your audience

If it’s not specified in your assignment prompt, it’s always appropriate to ask your instructor who the intended audience of your essay or paper might be. (Your instructor will usually be impressed by this question!)

If you don’t get any specific guidance, imagine that your audience is the typical readership of a newspaper like the New York Times —people who are generally educated, but who don’t have any specialized knowledge of the specific subject, especially if it’s more technical.

That means that you should explain any words or phrases that aren’t everyday terminology!

Equally important, you don’t want to leave logical leaps for your readers to make. Connect all of the dots for them!

See the other body paragraphs of this essay, along with 9 student essays, here .

9. Add paragraph transitions and concluding sentences to each body paragraph

By now you should have at least three strong body paragraphs, each one with 3–5 pieces of evidence plus your own analysis and synthesis of the evidence.

Each paragraph has a main topic sentence, which we wrote back when we made the outline. This is a good time to check that the topic sentences still match what the rest of the paragraph says!

Think about how these arguments relate to each other. What is the most logical order for them? Re-order your paragraphs if necessary.

Then add a few sentences at the end of each paragraph and/or the beginning of the next paragraph to connect these ideas. This step is often the difference between an okay essay and a really great one!

You want your essay to have a great flow. We didn’t worry about this at the beginning of our writing, but now is the time to start improving the flow of ideas!

10. The final additions: write an introduction and a conclusion

Follow this formula to write a great introduction:

- It begins with some kind of “hook”: this can be an anecdote, quote, statistic, provocative statement, question, etc.

(Pro tip: don’t use phrases like “throughout history,” “since the dawn of humankind,” etc. It’s good to think broadly, but you don’t have to make generalizations for all of history.)

- It gives some background information that is relevant to understand the ethical dilemma or debate

- It has a lead-up to the thesis

- At the end of the introduction, the thesis is clearly stated

This makes a smooth funnel that starts more broadly and smoothly zeroes in on the specific argument.

Your conclusion is kind of like your introduction, but in reverse. It starts with your thesis and ends a little more broadly.

For the conclusion, try and summarize your entire argument without being redundant. Start by restating your thesis but with slightly different wording . Then summarize each of your main points.

If you can, it’s nice to point to the larger significance of the issue. What are the potential consequences of this issue? What are some future directions for it to go in? What remains to be explored?

See how nine students wrote introductions in different styles here .

11. Add citations and bibliography

Check what bibliographic style your instructor wants you to use. If this isn’t clearly stated, it’s a good question to ask them!

Typically the instructions will say something like “Chicago style,” “APA,” etc., or they’ll give you their own rules.

These rules will dictate how exactly you’ll write your citations in the body of your essay (either in parentheses after the quote/paraphrase or else with a footnote or endnote) and how you’ll write your “works cited” with the full bibliographic information at the end.

Follow these rules! The most important thing is to be consistent and clear.

Pro tip: if you’re struggling with this step, your librarians can often help! They’re literally pros at this. 🙂

Now you have a complete draft!

Read it from beginning to end. Does it make sense? Are there any orphan quotes or paraphrases that aren’t clearly explained? Are there any abrupt changes of topic? Fix it!

Are there any problems with grammar or spelling ? Fix them!

Edit for clarity.

Ideally, you’ll finish your draft at least a few days before it’s due to be submitted. Give it a break for a day or two, and then come back to it. Things to be revised are more likely to jump out after a little break!

Try reading your essay out loud. Are there any sentences that don’t sound quite right? Rewrite them!

Double-check your thesis statement. This is the make-or-break moment of your essay, and without a clear thesis it’s pretty impossible for an essay to be a great one. Is it:

- Arguable: it’s not just the facts—someone could disagree with this position

- Narrow & specific: don’t pick a position that’s so broad you could never back it up

- Complex: show that you are thinking deeply—one way to do this is to consider objections/qualifiers in your thesis

Try giving your essay to a friend or family member to read. Sometimes (if you’re lucky) your instructors will offer to read a draft if you turn it in early. What feedback do they have? Edit accordingly!

See the result of this process with 10 example essays now .

You’re done!

You did it! Feel proud of yourself 🙂

We regularly help students work through all of these steps to write great academic essays in our Academic Writing Workshop or our one-on-one writing tutoring . We’re happy to chat more about what’s challenging for you and provide you customized guidance to help you write better papers and improve your grades on writing assignments!

Want to see what this looks like when it’s all pulled together? We compiled nine examples of great student essays, plus all of the steps used to create this model essay, in this handy resource. Download it here !

Emily graduated summa cum laude from Princeton University and holds an MA from the University of Notre Dame. She was a National Merit Scholar and has won numerous academic prizes and fellowships. A veteran of the publishing industry, she has helped professors at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton revise their books and articles. Over the last decade, Emily has successfully mentored hundreds of students in all aspects of the college admissions process, including the SAT, ACT, and college application essay.

Privacy Preference Center

Privacy preferences.

English 102 - Argumentative Essay