A Letter To My Pregnant Self

TLDR: In this personal essay, a mother reflects on her journey by writing a letter to her past pregnant self to assure her—and other mothers-to-be—about the wonder of motherhood.

Dear Pregnant Self,

You know I am not one for the cheesy stuff—I’m not a very romantic person. I don’t like Hallmark cards. I don’t even like Valentine’s Day.

So you know that I’m not prone to overstatement when I say this:

You are about to meet the love of your life.

That growing bump that you’ve been patting for the past few months, looking at in the mirror, wondering about? That’s the love of your life in there. I know it sounds cheesy, and if I knew any other way to describe it, I would. But sometimes, it turns out, the cheesiest things in the world are also the truest. I know you’ve had other loves in your life, but not like this one. There is nothing more pure and strong than this, there just isn’t. Agape love, the Ancient Greeks called it—a universal, unconditional love that transcends, no matter the circumstances.

I look at my birth photos now and it seems amazing to me that there was ever a time I didn’t know him. Before he was born, I didn’t have any sense of who I thought he might be or my hopes for him, other than that he would be happy. When he was born, I remember looking at him in total amazement, just thinking, “Who are you?”

The not knowing? That’s one of the sweetest parts.

So I’m not going to give you any of this "sleep when the baby sleeps" business. (Although seriously, sleep when the baby sleeps . People aren’t just making this advice up.)

I’m not going to tell you to enjoy every minute, because I know there will be days where you just feel raw and hormonal and weepy and not yourself and neither triumphant nor very joyful.

And I won’t tell you not to worry , either, because that’s simply not possible.

“When will I stop being afraid?” I tearfully asked my mom weeks after his birth, knocked over by this newfound combination of love and terror. “Oh honey,” she said. “You never will.”

Once, several years before I got pregnant or was even thinking about it, I asked a male coworker what it was like to have kids. “It’s like having your heart outside your body, running around in the world,” he said cheerfully. “That sounds so scary,” I said. “Oh, it is,” he said, still smiling. “And absolutely worth it.”

What I will tell you is to have long dinners with your closest friends—friends that have kids, friends that don’t. Friends that are married, friends that aren’t. They’re all going to be so important in this next stage of your life, even though it might take a bit more planning to see them after the baby is born.

If you’re a traveling sort, definitely take a trip. It doesn’t have to be a huge, over-the-top journey, just something fun to tide you over. (Although you can absolutely travel with babies. It just isn’t as convenient.)

But of all the things that keep you up at night as you wonder about this new world of motherhood , don’t worry about not loving him enough. That part will be easier than anything you’ve ever done before. Because like I said, you’re about to meet the love of your life.

Want evidence-based health & wellness advice for fertility, pregnancy, and postpartum delivered to your inbox?

Your privacy is important to us. By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Anna Gannon

Meditation Guide

Anna Gannon is an intuitive meditation and yoga teacher.

Related Articles

Can You Go Down a Waterslide While Pregnant?

Can You Donate Plasma During Pregnancy?

Everything To Know About Prenatal Yoga

8 People You Need in Your Pregnancy Support Crew - article body template

Everything to Know About Prenatal Yoga

These Are the 8 People You Need in Your Pregnancy Support Crew

Is Papaya Safe During Pregnancy? Yes, If You Follow a Few Guidelines

Can You Use a Massage Chair During Pregnancy?

6 Pregnancy Self-Care Tips for Expectant Moms

Get the newsletter.

Evidence-based health and wellness resources for fertility, pregnancy and postpartum.

CONFIDENCE, COMMUNITY, AND JOY

- Skincare Ingredients A-Z

- Skin Concerns

- Hair Removal

- Moisturizers

- Tools and Techniques

- Hair Concerns

- Hair Styling

- Fashion Trends

- What to Wear

- Accessories

- Clothing and Apparel

- Celebrities

- Product and Brand News

- Trends and Innovation

- Amazon Picks

- Gift Guides

- Product Reviews

- Mental Health and Mood

- The Byrdie Team

- Editorial Guidelines

- Editorial Policy

- Terms of Use and Policies

- Privacy Policy

- The Self-Expression Issue Overview Cover Story Arden Cho Has Found Her Light The B Side Get to Know Arden's Glam Team: Hairstylist TerraRose Puncerelli and MUA Sang Jeon

- 25 Products We're Using to Bring Our Favorite Summer Trends to Life

- Is This the End of Hotness as We Know it?

- *If You're Looking for the Next Big Jeans Trend, You Won't Find It

- 15 Matching Sets That'll Carry You Through the Summer Months

- Elevate Your Spring/Summer Look With These Not-So-Basic Denim Skirts

- These Trending Luxury Pieces for Summer Are Actually Worth the Buy

- Praise for the Silly Little Tattoo

- We’re In Our Brow Decorating Era

- The Watercolor Manicure Trend Will Transform Your Nails into a Monet

- The Varsity Trend Is the Retro-Sporty Alternative to Athleisure This Summer

- We're Wearing Highlighter Everywhere But Our Cheeks

- Powder Puffs Are Trending—Here's How to Use Them For Flawless Makeup

- 3 Important Life Lessons My Unexpected Pregnancy Taught Me About Self-Love

- Is This the End of the "Cool Girl" Beauty Brand?

Three Important Life Lessons My Unexpected Pregnancy Taught Me About Self-Love

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/aimee-3-c5d7984be2de4300a8e02aaac71a3cc3.jpg)

I've never trusted myself in life until now. Let me explain.

I'm 28 years old, the oldest child to immigrant parents, and I have had an awesome career thus far. I'm in a loving, long-term relationship with my best friend in the universe. I've traveled, moved, and taken care of myself and others. Still, up until now, I've never fully trusted myself with my decisions or happiness. It took a lot for me to admit that—especially in writing—but it's a realization that has made me proud of myself in my newest life phase as a soon-to-be mom.

I found out I was pregnant in late 2022, which, at the time, hit me like a ton of bricks. The holiday season; end-of-year commitments; and the shocking, life-altering view of a positive pregnancy test staring me in the eyes hit me hard. Morning sickness, fatigue, and loss of appetite also came down on me like an avalanche.

I've always dreamed of a family, and my partner and I would fantasize about what that day would look like when it came. We've had our baby names picked out for years and always joked about which of us would be the buttoned-up parent versus the jokester. Still, nothing could prepare us for the day that the thought we'd stored away in our memory boxes was becoming a reality. I always thought the day I learned I was pregnant would open a dumpster fire of second-guessing and self-doubt. Yes, I've experienced those questionable thoughts since finding out, but they haven't plagued me and consumed my life and brain as anticipated.

As a natural overthinker and people pleaser, I thought I'd be in for a mentally miserable, guilt-ridden pregnancy, fearful of all the possibilities and opinions. Instead, I’ve experienced an extreme sense of calm, and having honest conversations with myself has put me in the best mental state I've been in for a long time. I've looked in the mirror a few times and thought: What is wrong with me? As though this new chapter wouldn't be valid unless it was met with extreme angst.

"A woman may feel calm or nervous during pregnancy for several psychological reasons, including hormonal and circumstantial factors," says licensed psychologist Carolyn Rubenstein, PhD. "Aside from hormones, factors such as a woman's support system, financial situation, and overall health can also affect how a woman feels during pregnancy."

Pregnancy is challenging and looks different for everyone. Still, honoring a few truths of my own have helped me process this significant life change in a valuable way, making the good days great and the bad days feel more manageable. It's shown me the true meaning of giving myself grace and practicing gratitude, and I'm a better person because of it.

Ahead, find the three life-changing lessons I've learned so far that have gotten me the closest to feeling real self-love for the first time in—dare I say—ever?

Meet the Expert

- Carolyn Rubenstein , Ph.D., is a licensed psychologist and wellness consultant based in Boca Raton, Florida.

Transition Is Consistent, and Change Is Temporary

One of the first things I felt when finding out I was pregnant was the incoming of a huge life transition. Everyone tells you how much your life will change, but few people talk about these changes positively and optimistically. I was initially scared, but that changed when a close friend reminded me that most things in life—pregnancy included—are temporary. Bringing a life into the world is a huge deal, met with many emotions, but it isn't the only life transition you'll experience.

I had fears of my body changing, fears of my home being different, and fears of learning new things. Reminding myself that these phases will evolve has helped me work through them. "When faced with major life changes like pregnancy, it's common to feel overwhelmed and anxious about unknowns," Rubenstein says. "However, there are ways to shift your mindset and approach these changes with a more positive outlook." Rubenstein says reframing your thinking to focus on opportunities and growth is a great way to cope with change, which I've found valuable at the most uncertain times thus far.

The positive outweighs my fears when I think of how I've grown as a person in the past few months. I've used moments of uncertainty to better inform and educate my decisions. I've found a voice to advocate for myself in situations where I'd usually retreat, one of the significant self-improvement indicators in my book. This has taught me that I am a work in progress and will continue to be beyond pregnancy and motherhood.

Self-Care Is Critical

Aimee Simeon

In addition to reframing your thoughts, Rubenstein says practicing mindfulness and self-care—whatever that means to you—can help you better navigate significant life transitions. "Prioritizing self-care, such as rest, mindful eating, fitness, and participating in activities that bring you joy, can help you stay grounded and centered during this time," she says.

I've found this step critical in evolving during these past months. One year before getting pregnant, I was diagnosed with PCOS. I was physically and mentally burned out, and my self-esteem and comfort in my body were at an all-time low. Desperate to feel at home in my skin and manage my symptoms, I embarked on a journey to find my "thing" in the wellness world.

I discovered the healing powers of therapy, acupuncture, and movement tapping as a release. What started as a mission to balance my hormones turned into finding a source of joy where I could be with myself and feel happier for it.

Waking up in the morning and dedicating time to my body taught me the power of movement and the value of carving out time to be alone each day to feel more centered. Taking time each day for myself helped me feel less stressed and more connected and attuned to my mental health.

Having a new family member in our household will mean less solo time for the foreseeable future. Still, acknowledging the impact intentional solo time had on me motivates me to make it a nonnegotiable part of my routine instead of one that feels jeopardized when our baby is earthside. I want to show my daughter that her mom knows the importance of resetting and caring for herself so that she can show up for others.

Rubenstein says movement is beneficial, but you aren't limited to just working out. "Take time for yourself and do things you enjoy. This could be reading a book, taking a relaxing bath, or getting a prenatal massage," she says. Pregnancy has reminded me to relish in the moments of "nothing", including a midday nap, my favorite snack, or a weekend spent repotting plants—all things I may have deprived myself of before.

Connecting with myself in these moments that may otherwise feel mundane has increased my feelings of peace and happiness, showing me that comfort lies within when you allow yourself to feel it. Plus, there's nothing like extreme fatigue and nausea to remind you to slow the f down and smell the roses.

Embrace the Positive

I've often wondered if my positivity could be considered toxic or naive, but it's neither. "During pregnancy, the body undergoes significant hormonal changes, including increased levels of estrogen and progesterone, which can impact brain function and emotional regulation," Rubenstein says. "Hormonal changes during pregnancy can cause alterations in brain regions involved in emotional processing, social cognition, and memory. For example, some pregnant women have increased activity in the amygdala, a brain region associated with emotional processing and stress response."

I, by no means, have a perfect life, but practicing gratitude has helped me feel fortunate during this time. I'm grateful to my body for allowing me to be healthy enough to have made it this far. I'm also thankful for my small but mighty support system of friends and family, who are always around to talk or listen as I navigate this new chapter. I realize this is a huge privilege I do not take for granted.

Society has conditioned many of us, especially Black women, to embrace struggle and hustle, but doing so has only made me regularly feel stressed out, unhappy, and physically unwell. Talking myself out of this negative rut has been the ultimate radical act of self-love and one I fully intend to teach my daughter.

Creating life has taught me that, ultimately, life will throw you challenges, but it's genuinely up to us not to let them define who we are. This is a huge realization for me, since I'm someone who would typically let even the slightest mistake send me into a spiral of self-loathing and doubt. Instead, my priorities have shifted to making sure that I am mentally well before anything else, which has improved my life in all areas. Call me crazy or toxically optimistic, but basking in moments of gratitude and appreciating everything going well has put a lot into perspective.

Relinquish Self-Doubt

Before this current chapter in my life, self-reassurance was something I lacked. I questioned my outfit choices, looked to others to validate career moves, and didn't think to make a significant (or minor) life choice without fearing the opinions of my peers and family.

Pregnancy has taught me the most beautiful lesson that I am in control of nothing but myself. I can't control the outcomes of every transition in life, but I can control how I work through them and what I take from each process. I've learned to trust my instincts, listen to my body, and prioritize my mental health in a way that doesn't feel forced because it's the "cool" thing to do.

Instead, it's taught me to relinquish doubt and embrace control by loving myself. It's unlocked a new sense of optimism that will allow me to show up as my best for myself and my family; I'm forever grateful for that transition.

Related Stories

4 Black Women on Moving Cross-Country and Starting New Lives During the Pandemic

"Be the Storm": A Look at What Power Means at Every Age

8 Women Share the Ups and Downs of Living Alone During a Pandemic

I Lived It: Ending My Longterm Relationship During a Global Pandemic

Why Can’t "Smart Girl" and "Beauty Girl" Go Hand in Hand?

Exclusive: Meena Harris Is Changing the World, One T-Shirt at a Time

"I Finally Feel Relief": 11 Healthcare Workers on the Emotional Journey to Vaccination

From ER Nurses to Small Business Owners: 7 Real Stories of Pandemic Trauma

Shay Mitchell Is Pursuing Happiness on Her Terms

Get to Know Shay's BTS Team: Hairstylist Dimitris Giannetos and Stylist Shalev Lavàn

Editors’ Picks: The Best New Beauty Products We Discovered At Home

I Got a Haircut During My Wedding to Connect with My Higher-Self

How I Quit Drinking and Started Listening to My Body

9 Women Open Up About What It's Really Like to Have Anxiety

Why I Let Go of My Perfect Relationship

What People Don't Know About Love After a Toxic Relationship

Understanding what pregnancy feels like if you’ve never had this experience can be difficult. Here, we’ve answered some of your burning questions on this topic, including “What does being pregnant feel like?” and “How does being pregnant make you feel?”

- When to Start

- Due Date Calculator

- Prenatal Care Costs

What Does It Feel Like To Be Pregnant?

Being pregnant is a life-changing experience for many women — but it’s one that’s hard to comprehend if you have never been pregnant before. The idea of growing another human inside of you for nine months is a feeling only certain women can experience and, as much as they try, it’s hard to explain in words exactly what pregnancy is like.

Still, people often ask: What does it feel like to be pregnant? How does it feel to be pregnant, and what can you expect from a pregnancy experience?

These questions tend to come from women who are interested in becoming pregnant or are thinking they might be pregnant, but they can also come from men who are curious about what their wives, spouses, friends and other loved ones go through during this process. While every pregnancy is different, we’ve tried to describe in general terms what it is like to be pregnant below — to help all those who are curious understand this beautiful process in more detail.

Remember, it’s always best to speak with your doctor if you are curious about pregnancy or think you might be pregnant. They can offer the best medical advice for your situation.

What Does It Feel Like to Be Pregnant?

While some of the questions about what pregnancy feels like come from curious outsiders, others ask “What does being pregnant feel like?” for a more serious reason — they think they might be pregnant.

The first symptoms of pregnancy are different for everyone, and so is what being pregnant feels like for each individual. Perhaps you feel nauseous, tired and cranky, or maybe you think your breasts are tenderer than they usually are. Maybe you’ve missed your period this month.

Panic alarms may be going off inside your head, prompting you to ask, “What does it feel like when you get pregnant?”

It’s common to hope you can determine whether you are pregnant simply from side effects , but the most effective way to find out you are pregnant will always be through a pregnancy test. You can pick one up from your local drugstore or go to your doctor to receive a professional blood or urine test.

In the meantime, you may want to identify some of these side effects — how you will feel when you are pregnant. Here are a few early pregnancy symptoms that you may want to look out for during this time:

- Morning sickness, or nausea at any time of the day

- Cramps or headache

- Slight bleeding

- Food aversions or cravings

- Breast tenderness

- Mood swings

- Faintness or dizziness

- Missed period

Sometimes, women wonder what being pregnant feels like because they simply “feel different” and have a hunch they are pregnant. The abovementioned side effects can be due to many things other than pregnancy but, if you are not feeling like yourself or feel like something is “off,” you may be finding out for yourself what pregnancy “feels” like.

If you are experiencing any of these signs and wondering “How do you feel when you’re pregnant?” remember that a pregnancy test is the best way to confirm any possible pregnancy.

What Being Pregnant Feels Like as Your Baby Grows

Once you have your answer to the question, “How do you feel in early pregnancy?” you are probably just as curious to know the answer to this question: “What does it feel like being pregnant as your baby continues to grow?” After all, this is the one of the biggest questions from people curious about the pregnancy process; carrying a living human being inside of you is such a foreign idea to those who haven’t experienced it themselves.

Again, every woman’s pregnancy is unique, and only you will be able to know what it is like to be pregnant in your later trimesters. For many women, the earlier side effects of pregnancy lessen as they enter their second and third trimesters , but that’s not the case for everyone. Sometimes, the side effects of early pregnancy are replaced with more constant side effects that a woman can’t alleviate until her baby is born.

When you carry a child inside of you, your body reacts in certain ways. A lot of your energy is going toward creating this child, and you can’t expect your body to feel the same as it did when you were not pregnant. In addition to the symptoms listed above, you may also feel:

- The constant urge to urinate, a lot

- Fatigue and muscle soreness from carrying an ever-growing child inside of you

- Irritability due to difficulty sleeping and getting comfortable with an expanding stomach

- Mood swings due to changing hormones

- Constipation and other upset stomach

- Heartburn and backache

Don’t forget: All of what you feel during your pregnancy will likely seem trivial compared to the experience of labor and delivery .

Of course, what pregnancy feels like for some women will be easier than for others — but it’s important to be aware of these potential side effects if you are considering becoming pregnant in the near future. Having all the information before you get started will help you have the appropriate expectations for your pregnancy journey and understand that everything you are feeling during this time is normal.

What is it Like to Be Pregnant?

Typically, when you ask women, “What does being pregnant feel like?” they’ll say it is the most beautiful thing they have ever experienced. It’s a powerful feeling, to grow a child from nothing to a tiny human, and many are so happy with the end result that they may gloss over some of the harder parts of pregnancy.

But, before you become pregnant yourself, you need to understand: While many say it’s worth it in the end, pregnancy is very hard , comes with certain risks and possible complications, and should not be seen as anything less than a great commitment of your mind and body.

In addition to the physical challenges of pregnancy, there are a few mental and emotional challenges that many women have to cope with. The hormones of pregnancy can cause extreme mood swings that are often not helped by the stress of pregnancy and preparing to bring a little one into your family. While these mood swings are normal, they can be overwhelming for someone who doesn’t know how it feels to be pregnant.

If you are pregnant, you may feel:

- Stressed at the all the preparations needed for a baby

- Tired from the physical challenges of pregnancy

- Worried about your baby’s future, especially if you did not plan to become pregnant at this time in your life

- Misunderstood by unsupportive partners

- Panicked about how your life is going to change

- Depressed about your situation, whether due to personal circumstances or antenatal depression

While every woman’s experience is different, and it’s difficult to predict exactly what it will be, knowing the answer to the question “How do you feel when you are pregnant?” beforehand can help you better prepare yourself for the challenges and experience awaiting you. Remember, if you find yourself overwhelmed during your pregnancy or worried that you’re not feeling the way you “should,” this is completely normal — and you do have options.

If being pregnant feels like an unexpected, unwanted but unavoidable thing in your life, you always have unplanned pregnancy options such as abortion and adoption. Don’t ever let anyone tell you what you should feel during pregnancy; focus on yourself and your emotions, and don’t be afraid to reach out for support from loved ones and counselors, should you need it.

My Birth Story: Moms Share Their Birth Experiences

What to expect birth stories, jump to your week of pregnancy.

Essay on Pregnancy

Students are often asked to write an essay on Pregnancy in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Pregnancy

What is pregnancy.

Pregnancy is when a baby grows inside a woman’s womb or uterus. It starts when a sperm from a man joins with a woman’s egg. This tiny new life is called an embryo at first, and then a fetus as it gets bigger. A full pregnancy usually lasts about nine months.

Stages of Pregnancy

Pregnancy has three parts called trimesters. Each trimester is about three months long. In the first, the baby’s body is forming. During the second, the baby grows bigger and stronger. In the last trimester, the baby gets ready to be born.

Changes in the Mother

A pregnant woman’s body changes a lot. She may feel tired, have morning sickness, and her belly will grow as the baby does. She needs to eat healthy foods, get checkups, and take care of herself to help her baby grow strong.

The Birth of the Baby

When the baby is ready to be born, the mother will feel labor pains. This is when her body tells her it’s time for the baby to come out. The baby will come out through the birth canal, and the family will welcome a new member.

250 Words Essay on Pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time when a baby grows inside a mother’s womb. It starts when a sperm from the father joins with an egg from the mother. This can happen through a natural process when parents are trying to have a baby, or through medical help if they are having trouble.

Pregnancy lasts about nine months and is divided into three parts, called trimesters. In the first trimester, the baby is just starting to form. The mother might feel tired and sick. The second trimester is often easier. The baby grows bigger, and the mother can feel it move. In the last part, the third trimester, the baby gets ready to be born. The mother’s belly is very big, and she might feel uncomfortable and excited to meet her baby.

Health During Pregnancy

It’s important for the mother to take care of herself and the baby. Eating healthy food, going to the doctor for check-ups, and staying away from bad habits like smoking or drinking alcohol are all very important. These things help the baby grow strong and healthy.

Having the Baby

When the baby is ready to come out, the mother will feel pains called contractions. This is when the baby is pushing to get out of the womb. The mother will go to a hospital or a birthing center where doctors or nurses will help her give birth. After the baby is born, it’s a happy time for the family as they welcome the new member.

Pregnancy is a special time when a new life is being made. It’s full of changes, care, and excitement as families prepare for a new baby.

500 Words Essay on Pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time when a baby grows inside a woman’s womb or uterus. It starts when a sperm from a man joins with an egg from a woman. This is called fertilization. The fertilized egg then attaches to the wall of the uterus. This is the beginning of a nine-month journey, which we divide into three parts called trimesters.

The Three Trimesters

The first trimester is from week one to the end of week 12. During this time, the baby is called an embryo. It’s a critical time because all the baby’s organs start to form. The mother might feel very tired and sick as her body changes.

The second trimester is from week 13 to the end of week 26. The baby is now called a fetus. This is when the mother can feel the baby moving. The baby’s skin is thin and red, and its bones start to harden.

The third trimester is from week 27 until the birth. The baby grows bigger and stronger. It can now blink, dream, and even listen to sounds. The mother’s belly is very big, and she might feel uncomfortable and excited to meet her baby.

Changes in the Mother’s Body

A woman’s body goes through many changes during pregnancy. She might gain weight and feel different emotions. Her belly will grow as the baby grows. She will also visit the doctor often to make sure she and the baby are healthy. These visits are called prenatal care.

Healthy Habits for Pregnancy

It’s important for a mother to take care of herself during pregnancy. Eating healthy foods and staying away from harmful substances like cigarettes and alcohol are very important. Taking vitamins, getting rest, and doing gentle exercises can help keep the mother and baby healthy.

When the baby is ready to be born, the mother will feel contractions. These are like very strong belly aches that come and go. They mean the baby is pushing its way out. Birth usually happens in a hospital, but some choose to have their babies at home. Doctors, nurses, or midwives help the mother during birth.

After the Baby is Born

After the baby is born, it’s a time for joy and celebration. The mother will keep taking care of herself and the baby. The baby will need to eat often and sleep a lot. The mother might feel many emotions and get tired, but it’s important to ask for help if she needs it.

Pregnancy is a special time when a new life is growing. It brings changes and new responsibilities. It’s important for the mother to take good care of herself and get ready for the arrival of her baby. With support from family, friends, and doctors, she can look forward to the birth of her child. When the baby finally arrives, it’s the start of a new adventure for the whole family.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on My Own Philosophy Of Education

- Essay on My Parents My Hero

- Essay on My Parents Sacrifice For Me

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Experiences of pregnancy

When talking about their experiences of pregnancy, most people described it as life-changing, and discussed both its physical and emotional aspects. Some women enjoyed being pregnant and said they ‘didn’t have any problems’. Others found the experience of pregnancy more challenging, whether for physical or emotional reasons or a combination of both. Some men also talked about their emotional experiences during their partner’s pregnancy.

Common changes women talked about were altering their diets, looking and feeling different, craving certain foods, and experiencing fatigue and nausea. Some were surprised about how exhausted they felt. Many women experienced physical pain or discomfort during pregnancy, including sciatica, restless legs syndrome, deep vein thrombosis, headaches, fluid retention, heightened sensitivity to smell and heat, and tender larger breasts. When pregnant with twins, women felt that their changes and discomforts doubled. A few women loved the physical experience of being pregnant and embraced their new shape. Others felt ‘uncomfortable’ and described being unprepared for the physical dimensions of pregnancy.

> Click here to view the transcript

I went to the physio but they couldn’t push it in, they just said, “It’s the position that the baby’s in, there’s nothing you can do about it and try not to move,” [laughs].

Often women struggled to accept they were experiencing a ‘normal’ pregnancy because they felt so bad physically. Several women with more than one child said their second or later pregnancies were harder, particularly due to having to care for other children. Coping with nausea was more difficult when women had older children, experienced a lack of support, or when they had demanding or inflexible jobs. Some partners helped by providing practical support, including Ajay, a migrant father of one, who learned to cook when his wife was unwell during early pregnancy.

I found it immensely difficult on the train of a morning going into town. My GP gave me this recommendation to carry a plastic bag in my handbag so I that I always had something to throw up into if I needed to. It just places this pressure on you that I had never felt before, and I remember feeling like I didn’t want to be pregnant anymore. If this is what being pregnant is like I don’t want it, you can have it back. And my mum said to me, “You know, it’s only six more weeks and then you should feel better”, and the thought of six more weeks felt like a lifetime. The thought of just getting through the day felt like a lifetime.

So it was very draining, just very difficult – and again it placed a strain on the relationship with my husband because on the weekends he’d say, “Do you want to go out, do you want to go to a café, would you like to do this, would you like to do that?” and I said, “I don’t want to do anything, I just want to be at home with a bucket in my tracksuit pants [laughs] doing nothing”, because I just felt rotten. And you inevitably compare yourself to other people and the very early pre-birthing classes that I went to, they were talking about the importance of healthy eating and exercise and other pregnant ladies would say, “I go swimming four times a week”, and “I’m walking and I’m doing this”, and I thought, ‘I’m lucky if I can make to the letterbox and back’.

The physical and emotional aspects of pregnancy were intertwined for many women. Chelsea, a mother of one, described wondering if her nausea was caused by her anxiety or if it was the other way around. Others experienced a sense of disconnection between being pregnant and their day-to-day lives. Loretta described having difficulty focusing in formal work meetings while feeling her baby’s hiccoughs inside her: ‘That’s something I will never forget, just thinking – these two worlds are not matching in any way and I don’t know how they’re ever going to’. A few women mentioned social expectations to be happy, positive and ‘glowing’ during pregnancy.

And I can see that it’s a sacrifice. I’ve got a newfound respect for pregnant women and I will from now on question when they tell you how happy they are whether that is true because that’s the perception I gained before falling pregnant that pregnancy is lovely and exciting and sure, on many levels it is but the physical changes that happen to you and the daily aches you have.

And how sleep gets disturbed to the point that for me going to bed is actually the least pleasant part of the day because I feel breathless and I feel dizzy and I don’t feel comfortable and I can’t sleep.

I feel like nobody told me that, as if they either kept it to themselves, surely I’m not the only one going through these symptoms.

And I feel like the pregnancy affects my productivity. I’m always very goal-oriented person so to come home and not having energy to do what I would have normally done. Or not being able to walk somewhere as fast as I would have liked or as far.

Women talked about how the novelty of the experience of a first pregnancy distracted them from thinking about parenthood. Zara explained how she felt during her first pregnancy: ‘I think the whole time the focus was on the practical matters and I didn’t really give a lot of thought at all to the emotional consequences or realities of what it would mean to become a mother’. As a result, many women described being unprepared for life with a new baby – yet said they were not sure anyone could have prepared them.

A sense of vulnerability and responsibility for their unborn child was described by some women, while others remembered marvelling at having a baby growing inside them. Pregnancy brought emotional ambivalence for women such as Susanne who had always wanted to become a mother, but found pregnancy challenging and felt ‘miserable’.

I felt good for like a week. I’m like, ‘I can totally do this pregnant thing,’ and I just had this feeling, I just had this ridiculous idea that I’d be a bump and I’d be rosy and glowing and I could still walk and I could wear those tops to show off the belly.

I put on 10 kilos within about 30 seconds of being pregnant. I now know that it’s because I developed a form of arthritis which messes with your metabolism, whatever. So I had ongoing health issues throughout the whole thing, but I had no idea. So I couldn’t do any exercise, I could hardly walk, I could definitely not run, and I was emotionally… I’ve really bad psoriasis and the type of arthritis that I get is psoriatic arthritis. So it’s connected to psoriasis. I’d never had it before, never been diagnosed before, but looking back I’ve had it since I was a kid, it just wasn’t that serious. So the flare-ups went sort of undetected in an arthritis context.

The type of psoriasis and arthritis that I get is triggered by an immune system overloaded stress on your body which is exactly what pregnancy is [laughs]. So looking back that started pretty much straightaway, that achiness and, yeah, that beached whale thing.

So it was a really awful pregnancy and I felt really conflicted through the whole thing because this is all I wanted my whole life, and not only is this what I wanted my whole life but I left a heterosexual relationship and a heterosexual identity to be true to myself and I still am managing to have this amazing gift and living my dream and I am hating every single second of it.

A number of people related emotional distress during pregnancy to past experiences of depression and anxiety, or childhood experiences. When pregnant with her second child, Maree was worried about unconsciously repeating the favouritism she thought her parents had shown towards her younger sibling. Others experienced anxiety, stress, or antenatal depression related to the pregnancy itself (see talking points under the theme ‘Perinatal depression and anxiety’).

From my previous experience as a mental health worker, I started to spot warning signs that I needed to have some kind of communication. Because I think that the first step in anything, when you think that there’s something going wrong with your head, because that’s the first thing people spot, the first thing to do is to actually talk to people about it. So we’ve had a very open communication with my partner, and we’ve been able to talk a lot about the way that I’ve been feeling. And I’ve also been quite lucky, that I have quite a tight-knit group of male friends who are actually the partners of – my partner has a mum’s group, so there’s probably six mums who hang out every week with the kids, and they’ve all grown up together.

And the dads have actually got a tight bond now. And without trying to scare the males into having sort of bonding and talking sessions, that’s what we’ve been doing, and it’s been really useful. Because it’s not just me who’s been going through this, there’s been a couple of other guys who are in a similar situation of just stress, panic, fear, all of those sorts of things, coming out into the open. I think it’s the fear of the unknown, and wondering whether you can actually cope with having another child. There’s always an assumption that a guy can cope with everything that’s thrown at him and there’s not so much availability for support networks.

And there’s an assumption that a guy can get through this without any help. And yeah, I don’t feel strong enough to be able to do that. I’ve broken down a number of times. And by that I mean lots of crying and thinking that I can’t do it and I don’t have enough mental strength to get through the situation. But being able to express that has been very, very useful. As I got closer to the time of the birth I was much more excited about the birth.

A number of people experienced significant life events, including losing jobs, relationship breakdowns, family violence, or moving interstate or overseas, including to escape war. These experiences significantly contributed to emotional distress in pregnancy. Melanie described how a difficult relationship with her mother became more complicated after finding out that her mother had lung cancer. Tolai migrated from Afghanistan to Australia during very late pregnancy.

Parents described a range of complications during pregnancy involving the mother’s health, the baby’s health, or both. These included ectopic pregnancy, bleeding, placental problems, ‘incompetent cervix’, gestational diabetes, severe nausea (hyperemesis gravidum), ovarian cysts, high blood pressure and pre-eclampsia. Two people experienced problems with their babies, including supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and gastroschisis.

The emotional impact of these experiences ranged from a sense of inconvenience through to significant distress. Erin described a range of complications including gestational diabetes in her fourth pregnancy and bleeding for over half of her sixth pregnancy due to a hematoma within her uterus.

So they could see that I had a sub-chorionic haematoma, which is like a blood sac next to the gestational sac. That was – it was bigger than the baby at that stage. And they said, “Prepare yourself for the worst, because the bleed could push the foetus out”. And there was nothing they could do really. It is what it is. So I was going on and I was just bleeding all the time and, you know, being pregnant and bleeding does your head. I know what it was like when I was bleeding when I had my fourth child. It was horrendous, you know. You just can’t relax. But, I mean, there was a break there. It wasn’t happening all the time, whereas this was constant bleeding and it was awful.

I couldn’t function. I just felt like I was walking on eggshells all the time. It was like, ‘Can you either just make up your mind, are you going to stay or are you going to go, but don’t have this constant’. Because going to the toilet was doing my head. It was a constant reminder that things were not normal. And there’d be days where all of a sudden it would just be a huge bleed, and I’d think, ‘Oh God, is this it’? You know, it was awful. So I could never relax. I was always just really tense, which is not a good thing to be when you’ve got five other kids to look after as well and life to continue.

Prenatal testing results that fostered fears about a baby’s health were stressful for people. Despite Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) revealing that Sarah M’s baby did not have Down Syndrome, she continued to have ‘morbid thoughts’ about her pregnancy. Loretta’s first child was diagnosed with a genetic condition while she was pregnant with her second, making her anxious about her unborn daughter. Rarer or more serious complications were experienced by some women, sometimes with a risk of stillbirth or a threat to their own health or fertility. These included extremely rare conditions such as placenta percreta. A few women were hospitalised for part of their pregnancies. Surgery for an ectopic pregnancy left Jane, who is now a mother of twins, unable to conceive, leading her and her partner to undergo IVF (which was successful).

So after that I had to heal and it was emotionally difficult, but it was just one more thing. We just kind of kept it aside – so that was pretty horrible. So we kept trying, once I’d recovered. It took a few months, because I was just so lacking in iron, and we started trying again and then just couldn’t, because I’d lost one fallopian tube. So, I really felt violated and brutalised and it was hard. But, you know, we really wanted to have children.

So my mother had said she would help us and she gave us some money so we would be able to afford to do IVF and we did three IUIs, which weren’t successful and even though my husband has this amazingly high, fantastic sperm count, it just didn’t work. So we had to try IVF and we only did two cycles and the first time we had two implanted and it didn’t work and at that point I thought we’ve got to give this all we could do. I’m always on the internet, so I’d known the statistics on how hard it was going to be at my age, because by then I was 41, 42, while we were doing this and anything over 35 can be very difficult. Over 40 you are incredibly lucky.

So I thought we’ve just got to go all out. We can’t keep affording to do this forever. So we found a woman, through a friend of mine, through word of mouth. Found this woman who was a Chinese herbalist and naturopath and I’d read that acupuncture is really good for IVF. So she had me on all these potions and things I had to drink, herbal remedies and, acupuncture quite a lot and – that cost us thousands too. But I think it really made the difference. So three months later, from the first IVF we went again.

Further Information:

Talking Points Experiences of pre-term birth, special care, stillbirth and death of a baby Experiences of conceiving, IVF, surrogacy and adoption Talking Points under the theme ‘Perinatal depression and anxiety’

Other resources

COPE: Expecting a baby

Personal Narrative: My First Experience When I Was Pregnant

How did I find out I was pregnant? The beginning of 2016 I had been talking to this boy named Rodney and we had been getting really serious with other about being in a relationship. April came and my mother did like the fact that I was staying with him; she wanted me to get on birth control because she didn’t want me to have any babies yet. I agreed to the birth control there were many to choose from I was scared of needle so I didn’t do it that way , I took the easy way and got the patch. With the patch you wear it for three weeks and the fourth week you have your period. Later that month Rodney took me to prom and we had so much fun with each other. We were really in a relationship by then, May is here now and I have just turned the Big 18. That means I …show more content…

I felt really bad because we were arguing the night before. After his surgery I had finally made it down there, the doctors told him that he need to walk so as me and him was walking I had told him I thought I was pregnant. He looked at me and said I had a feeling you was pregnant because of the pain you had been feeling and you not having your period. I didn’t think he was gone be happy about it but he was. I still kind of doubted it because of the birth control. We decide that I need to take a pregnancy test so we went to my house and got me sister and her friend and told them. My sister’s friend was a little older than me so I got her to get the test for me. Rodney and I went back to his house and I took the test and waited for the results. It was Positive; I never felt so many emotions at one time before. All I could think was what my mother was going to say, how I was going to tell her. I showed Rodney and he was happy but because I didn’t know what to do all I did was cried. I called and told my sister and they came right over and she was happy but I just

Personal Narrative: My First OB Clinical

This past Thursday was the first OB clinical day and I was assigned the post partum unit. I was paired with Nurse Donna, who was full of information. Originally we had three couplets, with one baby in the nursrey. As the day went on and families were discharged, all our patients had gone home so we gained three other patients from two other nurses so they could go home for the day. I was able to give two moms their TDAP (tetanus, diptheria, and pertusis) vaccines and learned a new trick when it comes to giving intramuscular shots. Donna told me to have the patient hang her arm down by her side and wiggle her fingers. This not only had the patient concentrating on something other than the shot they were about to get, but it helped activate the

Personal Narrative: My Clinical Experience

I had such a great day at clinical yesterday. I was finally able to see a vaginal delivery and that entire process. When I arrived in the morning, the mom had just received Cytotec, to help induce labor and ripen her cervix. She was forty-one weeks and zero. Around ten thirty in the morning, she asked for her epidural to manage her pain. We bolused her with fifteen hundred milliliters of lactated ringers to prevent hypotension. Shane was the certified registered nurse anesthesiologist (CRNA) who administered the epidural. It was very cool watching him administer all the needed pain relief medication before he administered the epidural to make sure that it would be placed in the epidural space in the spine. Then administered a small test dose, waited till a few blood pressures were taken, then administered the remaining about through an epidural pump. After the epidural was administered, I was able to administer her foley catheter. I was so happy that I was finally able to place one. I learned a few tricks from Maura (my nurse) as well. She taught me that it was easier to take the top off of the lubricant syringe and to place the tip of the foley inside of the syringe, that way it will not wiggle around and become unsterile. She also taught me to grab from the bottom of the labia and pull up, that way it ensures that I will have a clear entrance to

Why Adoption Is Wrong?

It was late February in 1998 when I found out I was expecting another child. I was 16 years old. It should have been a happy day it was my daughter’s 1st birthday party and everyone was there. The house was full of family and friends and smelled of chill and cake. Please don’t get me wrong, it was a happy day for the most part until I found out I was pregnant. Scared and not knowing what to do, I kept this what most would call exciting news to myself. You see I was dating a man and he was not a very nice person he was mentally and physically abusive to me most of our relationship and he was the soon to be father. A month or so went by after I told him and we were both somewhat excited him more than I. I was more scared then anything. He managed to get himself into some legal trouble and was sent away for a long time. Where did that leave me? I was scared to death

Personal Narrative: My Experience With My Female Birth

My one true goal in life was always to be a mother. I was thirty years old and had underwent over four surgeries on my female organs. I had finally given up hope that I may ever get pregnant and it not ultimately end in a miscarriage.

Personal Narrative: To The Woman Who Birthed Me

Hey Nandi, just letting you know that you're a really amazing person. Honestly you're a unique person there is no other person I could meet on the planet that could out weight your personality. I've decided that since the day I was born, BAM, mother-child bond. You've always been a strong woman you've done everything from working two jobs, to go our every school events, and handling our family problems. You're extremely happy even in bad situations and your not afraid to show us discipline that has an impact. You're a woman of few words but when you do open your mouth something extraordinary comes out. You fight for us, love us, your kind to all people, help raise strong people by putting reality in front of us since we were little. The most valuable lesson you've taught me so far is, life's going to be extremely difficult at times but you have to be strong, because you are strong, you can fight, and if you go down swinging better make worth your while. Couldn't ask for a better woman in my life.

Personal Narrative: My Prenatal Development

My prenatal development was normal. There were not any concerns or worries about my development. My mom had a fairly normal pregnancy other than preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is a medical condition in women who have not experienced high blood pressure, and developed in during a pregnancy (Preeclampsia and Eclampsia, 2016). High protein levels in urine and swelling of the hands, legs and feet are other symptoms of preeclampsia. My mom had an ultrasound at fourteen weeks. She did not have any other testing like an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. It was unnecessary.

Personal Narrative: The 2nd Trimester Stage Of Development

I decided to discuss the second trimester stage of development because for me, with both of my pregnancies, that is when I started to get really excited about having a baby. There is the whole scare of losing the baby in the first trimester but also that’s when I started to feel the baby move, both times in the 16th week, when the baby, and myself, grew the most (I gained 8 pounds in the 5th month with both pregnancies), and when I got so heavy I had to walk instead of run, it was actually faster from about 18 weeks on. Babycenter.com says that the fetus of 14 weeks of age is the size of a lemon, 3 ½ inches long and weighing 1 ½ ounces, while parents.com says it’s the same weight and length but the size of a peach. At 27 weeks both sites said the babies are at 2+ pounds, 9.25-14 inches long and either the size of a head of cauliflower or a sock monkey (which wasn’t fun to look at when your trying to picture a cute little baby). On page 96 of the textbook in Figure 5.8 it is confirmed that after the 16th week the mother may start to feel the baby move. The fetus is also forming small hairs all over the body, including the scalp, and the lungs are beginning to

Personal Narrative: The Mother Of One

Alexus Casidy is out of her teenage years and now twenty, with a whole life ahead. The name Alexus may be a common but, the story of how it was picked, was not. Her father named her after a nurse at a Psychiatric Hospital, that he said was pretty. Not only did he name her after a nurse but, he chose the spelling of the car, Alexus. She grew up with her two younger siblings in Beloit WI, and I am yet to wonder if her sibling’s names have a comical story behind theirs as well. My peer went to high school at Beloit Memorial, graduating in 2015. Where she was an active cheerleading and softball player, also where she met her boyfriend, of three years, Ryan. Most don’t see that she is a mother, student, girlfriend, and employee; holding many different roles in all statuses. Alexus studies at UW Rock County and is undecided with fulfilling her dreams for becoming a children’s nurse or a teacher. Also, is hard-working employee at the factory Prent Corporation in Janesville, WI as an Inspector Packer. Where the money pays for the house her and her boyfriend own, with their one year old, Brooks.

Personal Narrative: My First Clinical

My first clinical I felt my greatest accomplishment was not being shy and hesitant. The first day we had clinical was the first day that I got the opportunity to float to another floor, I was very nervous at first. Going into a new place for anyone is different at first because you don’t know what to expect. I think what made my experience so great was the endoscopy nurses and doctors, they were some of the nicest and helpful people I’ve met so far. I got a wonderful opportunity to learn next to the doctors doing the procedures and also see other roles of the healthcare team like the nurse anesthesiologist.

Today was the second day of my 6-week placement at Ward 3A-Logan Hospital, I have originally been paired with a demand casual pool RN, however, the said RN is not confident enough to handle me as her student nurse at the time. After the scrum at 7am, and the handover on the 4-bed bay + sides, I politely ask her if I could take one patient as it was one of the instructions of my CF during the orientation on day 1, but I was answered with “I’m not really familiar with the area and I’m from the demand casual pool...” Having sighted my CF at the corridors, I excused myself from the RN and discussed the matter to my CF, and she allowed me to be buddied with a very good EN, informing me that “she is an EN” before letting me to the bay and introducing me to my new buddy EN.

Personal Narrative: My Postpartum Trauma

It was 3 years ago when I was diagnosed with Pectus Excavatum, a condition in which the breastbone sinks into the chest. 1 in every 400 births have it. My condition over the years began to get worse, reducing my ability to participate in sports. The feeling of being exhausted everyday started to hit me as time passed. After finally being diagnosed, my mom took the initiative to schedule my surgery date on June 8,2015. I had asked myself “What if something goes wrong?”, over and over creating this emotion of vulnerability inside me. This feeling that I had never fallen victim to, brought me to a time of reflection. Reflection on the life that I had lived up to that point. The question "What if I don't make it out of this? Is not a common question for someone my age, at least I don't know anyone who has had to ask this of themselves.

Personal Narrative: My Clinical Experiences

This week I had rotation at Genesis and also Cumberland Hall. Genesis was very different that what I expected. When I think of a “rehab” I think of people all sitting around with major withdrawal symptoms, a very strict schedule, multiple one-on-one session, and with no smoke breaks. At Genesis, throughout the day the client was able to do their own thing until the scheduled group session and smoke breaks. I was placed on the male unit and I was very surprise of the self-awareness that I experienced. Just listening men talk and tell their stories brought on a whole new prospective and quickly changed the image of the addict stereotype. While I was there we also established that all the clients was first timers and all fathers, and afterwards I was able to sit and think about how grateful I am to have my father who’s not an addict. I have had the luxury of always having a clean and sober father; which I had taking for granted.

My first clinical was a good experience because I learned a lot. I would say my first day involved experiences that I was expected to learn but also ones I didn’t. I learned that getting up at 5am in the morning really isn’t as bad as you think, once you get your coffee paid of course. As well as the drive from Valpo to St. Mary only talks about 20 mins. As soon as I arrived at the hospital, I expected to learn about what we as student nurse would be doing, as well as that since it was the first day, learn are way around the hospital. I wasn’t to nervous about going to a hospital for clinical, but as Soon as I stepped on the oncology unit I got a little nervous. It hit me that I was no longer just practicing vital and providing base care to

Personal Narrative: Growing Up With A New Baby

It’s August 13, 1975. Mom left the house 2 days ago, and she came back today with a new baby. He doesn’t look like a newborn, he has none of my parents features, and well he looks kind of weird. But, I guess I have really never seen a newborn and I mean the kids at school call me weird so maybe we are exactly the same. I can tell from the start that we are going to be great friends, but I just can’t help it when he cries I get so annoyed. It’s like he is doing it on purpose. Mom and Dad left the house a few minutes after they got home and I didn’t see them for another 5 days. All I heard from them was, “ There is food in the fridge. Should be enough to last you a few days. Take care of this one. Lord knows we don’t need any more trouble than we are already in.” How could they just leave me here with this annoying little brat? lts evident that Mom and Dad don’t care about me or my little brother.

Personal Narrative: My Goal For Clinical Experiences

My goal for clinical experiences is to apply what I have learned throughout my semesters to a clinical setting. I want to become more competent in my skills. I want to be able to look at a patient and identify clues that help me create a focus assessment. I also want to be able to use the patient medication to identify some adverse effects to create a preventative plan of care. My goals are to become more structured with my care plans. I want to make them more patient centered and more focused on initial issues that the patient might have then move it towards preventive methods instead of having my preventative methods first . I also want to become more confident in preparing and starting IV. I know that perfecting starting an IV will come

Related Topics

- Menstrual cycle

Personal Narrative Essay: The Story Of My Pregnancy

This is the story of my pregnancy. The night I found out I was pregnant I got a funny feeling in my stomach, and I wasn’t sure what was going on. I told my mom what was going on, but she was already suspecting I was pregnant and already had a test ready for me to take. I took the test and the results was positive. I cried because I was scared and in shock. I showed my mom and I called my boyfriend Damonte to tell him the news. He was in shock and scared of how his mom was going to react. My mom already agreed to tell his mom. The next day I went to the doctor and she confirmed the test was right. I was indeed pregnant, she said I needed an emergency ultrasound. So, she set that appointment up for the next morning. After my appointment my mom called my boyfriend’s mother to tell her the news because I was scared. I didn’t know how she was going to react. We found out that she already suspected as well and wanted to see me after we got back. So, when we got home my boyfriend’s mother Jendie came and got me from my house. I had previously texted my boyfriend when our moms were on the phone to let him know she wasn’t mad at all and he could relax a little bit. Everyone got their shock of the news and seemed happy that …show more content…

I have a high pain tolerance, so it took all day for me to start feeling my contractions and I eventually needed an epidural. Thirty-six hours later I was fully dilated, and it was time to start pushing. The doctors gave me the option to watch myself give birth and I did so with my mom, my boyfriend, and his mom by my side at 3:35 PM my son was born and fully healthy thank god. My son is five and a half months old now. He is my motivation, a big reason why I’m getting my diploma. I am so happy to be a mom and Damonte is so happy about being a dad. We have fallen more in love with each other

Summary Of The Glass Castle By Jeannette Walls

The next day came and my mom said that he had made it through the night, so I was really happy so I could go see him again! I had a basketball scrimmage that morning in Van Wert though, so I thought that I would be able to go and see him after that. But when I got out of the scrimmage I looked at my phone and my mom had texted me that he had passed. It was one of the toughest days ever. That was really hard for me to get through my head that he wouldn’t be with us anymore.

Book Report On The Glass Castle By Jeannette Walls

She was freaking out, of course, but my dad stayed calm. They talked for awhile and when he got off the phone, he said, “Your mother said I can either bring you home right now or I’m calling the cops!” I told my dad to let her call the cops. He called her back, told her what I said, and they hung up. About ten minutes later, the cops were calling my dad.

Personal Narrative: R Bend's Shoes

Even though I knew that my mom understood that I was in pain, that didn’t stop me from complaining. Once my mom pulled into the parking lot of the emergency room, she faced the next challenge. Getting me out of the booster seat. I know that my mom loves me and was not trying to put me in pain, but boy did that hurt! I cried and cried as she took me into the emergency room.

9/11: A Short Story

We went to the attendance office to pull him out of class and they said they couldn’t because they were outside and my Dad was starting to get mad because my Mom was about to give birth to my little brother any minute and my Dad could not miss it. We finally got him out of class and we flew to the hospital. When we got there we went straight to a room because my dad had to go to my mom because she was having a baby. While we were in the waiting room we watched T.V on a big flat screen T.V. We sat in there for about four hours waiting, it was like watching paint dry it was the longest time of my life. Justin and I were watching some Zeke and Luther and the doctor comes in and says “Do you want to see your baby brother”.

Personal Narrative: My Trip To Six Flags

New Plans One Saturday morning, I woke up at seven in the morning to go to an amusement park called Six Flags. The plans had been made days ago, my two older sisters, my brother, a friend of ours and I would be going to Six Flags and spend the entire day there. As I got up after finally getting my alarm to finally shut up I walked over to the bathroom to take a shower when I realized that the ground was spinning, in my eyes at least, I had a vile taste in the back of my throat. I quickly fell back onto my bed feeling like if I hadn’t

Personal Narrative: Celiac Disease

It was the middle of summer when it happened. I was about 9 years old and my mom and dad had just called me into my mom’s room. I had had a medical procedure about a couple of weeks before hand so I wasn’t surprised when they said it was about the results. They started talking to me about the results when they finally told me the main thing that had showed up.

Monologue The Crucible

I got away with it for awhile but the guilt overran me and I told my mom a day later. She wasn’t mad or disappointed but glad I finally told the truth and sometimes it’s better to tell the truth.

Personal Narrative: Misdiagnose

So, like any other teenage girl, I told my mom. She was worried, so the next day she took me to the doctor. I sat there

Foster Care Narrative

We found out that it, is a boy and he would be born in the fall. Each day got better since we heard the news, but I still couldn’t be with my mom. I was never close to her, I’ve always been a daddy's girl, but going to foster care changed that. I have gotten closer to my mom and now my dad and I can’t talk about what we used to

Summary Of The Pregnancy Project By Gaby Rodriguez

Gaby Rodriguez spent her senior year with a fake pregnant belly on her body. She was told her entire life that she was going to end up just like the rest of her family: pregnant as a teen in high school. Defying all stereotypes, and working hard to disprove them, she used her year-long senior project to change everyone’s minds. The Pregnancy Project by Gaby Rodriguez is a realistic, eye-opening story that all teenagers should read. One of the things that makes it such a good book is the rawness you feel the whole time.

The Pregnancy Project By Gaby Rodriguez

The two novels, “The Pregnancy Project” written by Gaby Rodriguez and the novel “Turning 15 and On The Road to Freedom” both share the same meaning. Both authors of the novels write about taking action. In the short novel, “Turning 15 and On The Road to Freedom”, Lynda Blackmon Lowery helps to the march for the right to vote. Many people took action and sacrificed a lot to help others approve Selma’s voting rights. In the novel of “The Pregnancy Project” Gaby Rodriguez illustrates her Senior Year Project which showed how stereotypical people can be.

Personal Narrative Essay: Becoming A Single Mother

I waited a few weeks the flu like symptoms, sick stomach, sensitive skin, random headaches; finally giving in and went and bought a test. When it came back positive I was in disbelief. I made my appointment at our local pregnancy center to get my confirmation letter. The confirmation letter is required to go visit an actual OBGYN. The appointment was two days before my twentieth birthday, I also had to inform the father of the child I was carrying.

Personal Narrative: The Day I Gave Birth To My Daugther

My mom and sister started running around getting things ready because it was time to head out to the hospital it was bbay time. My contractions werent that bad till i got in thecar ride it was horrible i remeber i almost started crying from the excrutiating pain i was in. I remember getting to the hospital and 2 hours later doctors and nurses where rushing and it was because

Personal Narrative Essay: Becoming A Father In My Life

Becoming a father in my life was the best thing that has ever happened to me. Living for someone else and not just yourself is a special feeling. Knowing that it is your sole duties in life are now to love, provide, teach, mentor, discipline and love some more. I always hear people say “ Im don 't think I 'm ready to be a parent.” and to be honest I do not think anyone is ready to be a parent.

Personal Narrative Essay: Growing Up In My Life

Then 9 months later on February 16, 1999, at 3:10 am my precious son came out of my womb and placed on my chest. It was the most amazing experience ever, but also extremely exhausting thing ever! I was in the hospital for about another week till the doctor told me to go home, funny thing is that I got discharged on my birthday February 21, 1999, which I turned 16. At first, it felt like being a mother was easy, but in reality, it wasn 't because I also had to go to school plus he would always wake me up in the middle of the night, and be in an extreme of exhaustion. I started missing school more and more till I finally dropped out.

More about Personal Narrative Essay: The Story Of My Pregnancy

Related topics.

- English-language films

- Open access

- Published: 10 November 2023

Women’s experiences of social support during pregnancy: a qualitative systematic review

- Mona Al-Mutawtah 1 , 2 ,

- Emma Campbell 1 ,

- Hans-Peter Kubis 1 &

- Mihela Erjavec 1

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 23 , Article number: 782 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5305 Accesses

4 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Social support during pregnancy can alleviate emotional and physical pressures, improving the well-being of mother and child. Understanding women's lived experiences and perceptions of social support during pregnancy is imperative to better support women. This systematic review explores and synthesises the qualitative research on women's experiences of social support during pregnancy.

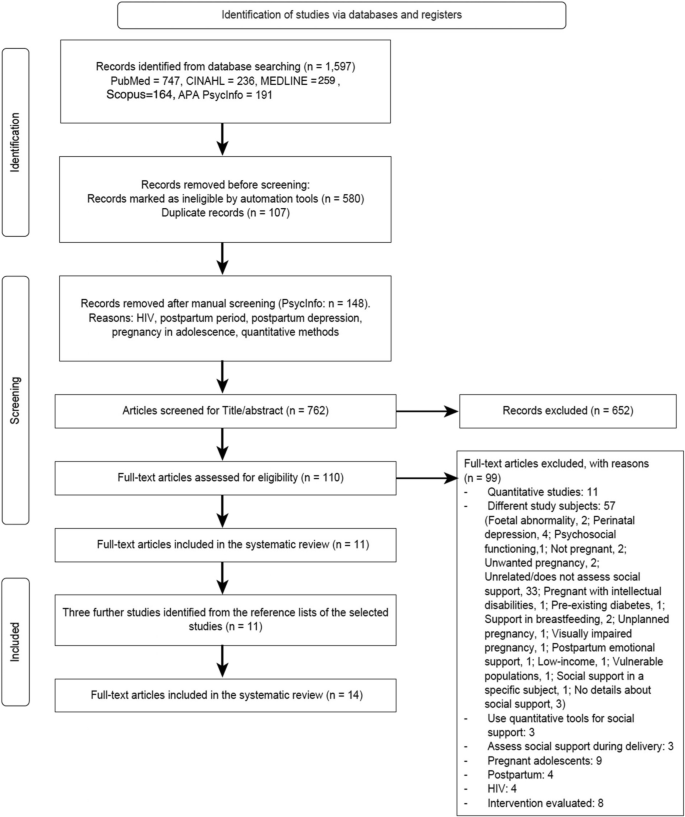

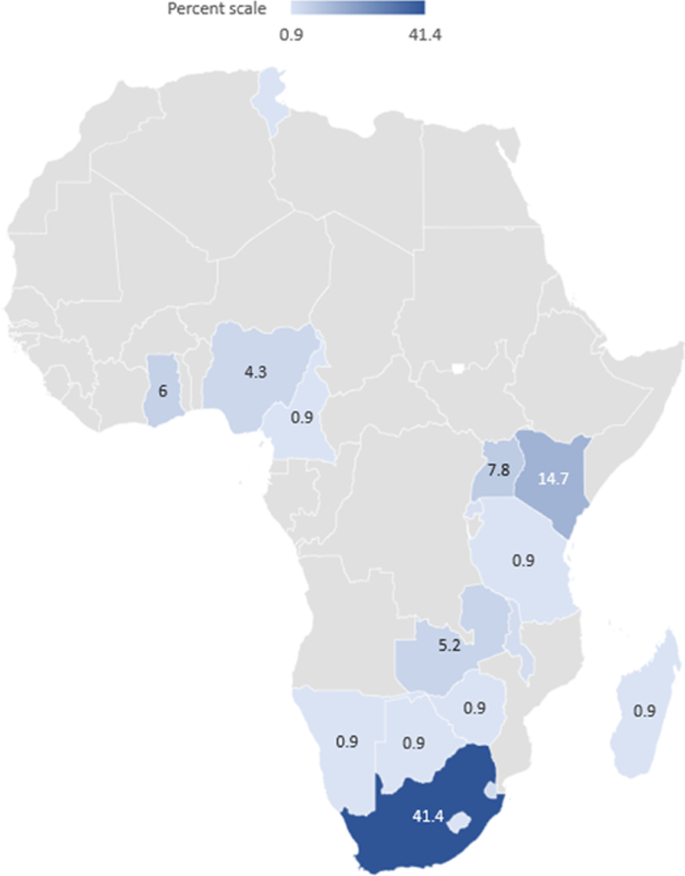

Databases PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo and Scopus were searched with no year limit. Eligible studies included pregnant women or women who were up to one year postpartum and were assessed on their experiences of social support during pregnancy. The data were synthesised using the thematic synthesis approach.

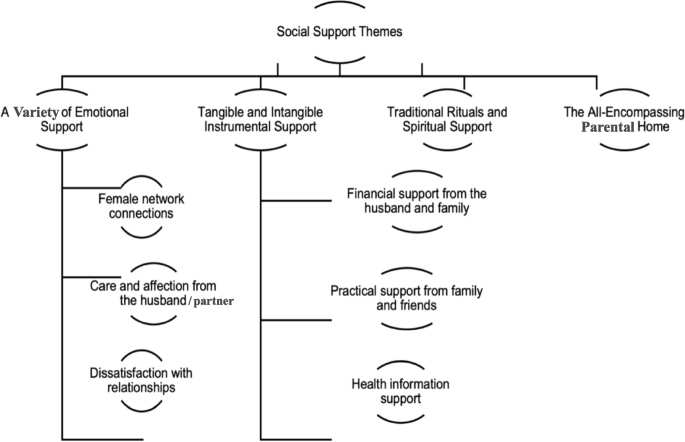

Fourteen studies were included with data from 571 participating women across ten countries; two studies used focus groups, and 12 used interviews to collect their data. Four main themes were developed ('a variety of emotional support', 'tangible and intangible instrumental support', 'traditional rituals and spiritual support', and 'the all-encompassing natal home'), and six sub-themes ('female network connections', 'care and affection from the husband', 'dissatisfaction with relationships', 'financial support from the husband and family', 'practical support from family and friends', 'health information support').

Conclusions

This systematic review sheds light on women’s experiences of social support during pregnancy. The results indicate a broad variety of emotional support experienced and valued by pregnant women from different sources. Additionally, women expressed satisfaction and dissatisfaction with tangible and intangible support forms. It was also highlighted that spirituality played an essential role in reducing stress and offering coping mechanisms for some, whereas spirituality increased stress levels for others.

Peer Review reports

For some women, pregnancy is considered a time of joy, but it also involves many well-being, social, and physical changes (e.g., emotional, physiological, and relational changes). These changes during pregnancy can present many challenges [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. For example, Yin et al. [ 4 ] conducted a systematic review to investigate the prevalence of antenatal depression during pregnancy across several continents. The results showed that the prevalence rates of any antenatal depression were 20.7%, and 15% of pregnant women experienced major antenatal depression, which is higher than general population 14.5% [ 5 ]. Other challenges reported in the existing literature are related to unplanned pregnancy, mood instability, physical health problems, financial problems, and a lack of social support during pregnancy [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, social support during pregnancy reportedly helps to alleviate the pressures of the pregnant women’s emotional and physical changes, and suggests to improve the mother and child’s well-being [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

The conceptualisation of social support

There is a wide range of literature connected to social support from many perspectives and disciplines over many decades of research [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Social support has broadly been outlined as a complex, multi-dimensional concept that can be defined as assistance provided by a person’s social network and involves the provision of emotional and physical support [ 16 , 17 ]. However, from a traditional psychological perspective, Cohen and Wills [ 13 ] describe social support as support from social networks that can influence health through two pathways (direct effects and stress buffering). The direct-effect hypothesis suggests that social support can improve health regardless of whether the environment is stressful or not [ 18 ]. Further, it contributes to a sense of belonging and stability, resulting in improved self-esteem and reduced stress and mental health disorders [ 19 ]. Alternatively, the stress-buffering hypothesis posits that support may buffer against unhealthy reactions and provide the individual with access to additional resources that will enhance their capacity to cope with stressful events in two ways:

Perceived support can prevent a psychological or physiological stress reaction from arising when a potentially stressful event occurs. Consequently, perceived support may increase the perception that individuals can cope with negative events.

Perceived social support can intervene between the event of a stress reaction and the onset of a pathological process by reducing the stress reaction [ 19 , 20 ].

Social support during pregnancy

Kroelinger and Oths [ 21 ] explored the role of social support in wanted and unwanted pregnancies. The results indicated that unwanted pregnancies are strongly influenced by factors such as support from partners, the partner’s stability and status, and their feelings towards pregnancy. Therefore, Kroelinger and Oths highlights the potential role of a partner’s social support during pregnancy and shows how the lack of a partner’s support, particularly their emotional and practical support, can negatively affect women’s experiences by leading them to experience the pregnancy as unwanted. However, although, the relationship between a partner’s social support and whether a pregnancy is desirable seems simple, a person may decide that they want the pregnancy while it progresses based on certain discoveries, experiences, or events that are unrelated to the social support they receive from their partner. For example, parental social support can buffer the negative impacts of an unsupportive partner [ 22 ].

Likewise, Rini et al. [ 23 ] aimed to assess their experiences of the quality and quantity of social support they received from their partners, referred to as social support effectiveness (SSE). It focused on three functional types of social support: practical, emotional, and informational support. Greater SSE from partners predicted less anxiety during the second to third trimesters [ 23 ]. In addition, a recent systematic review of social support during pregnancy sought to investigate the relationship between social support and mental illness during pregnancy. A significant positive correlation between low social support and antenatal depression (14/15 papers), antenatal anxiety (6/8 papers), and self-harm (3/4 papers) was found [ 6 ]. Although these studies stressed that social support directly affects mental health, the pregnant women’s feelings, attitudes, perspectives, and past pregnancy experiences may mediate the relationship between a partner’s social support and the pregnant person’s anxiety [ 24 ]. This aligns with several studies that showed that those who perceive adequate social support during pregnancy are less likely to report stress, distress, or symptoms associated with anxiety and depression [ 25 , 26 , 27 ].

The above evidence demonstrates that social support may influence women’s experiences during pregnancy. However, more recent research has also incorporated contextual and situational factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Since December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected almost all countries and territories and cases of COVID-19 increased exponentially worldwide [ 28 ]. Recent research by Meaney et al. [ 29 ] aimed to assess pregnant women’s perceptions and satisfaction with social support from an online survey conducted with 573 pregnant women during the pandemic from the US, Ireland, and the UK. The authors illustrated that a reduction in perceived social support that resulted from the lack of access to antenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic increased negative feelings such as sadness, anxiety, and loneliness during pregnancy for these women. Although this kind of research can help healthcare providers determine strategies to help women during stressful times, further research is required to identify the types of social support (e.g., emotional, instrumental, etc.) that were most affected by the pandemic.