A Step-by-Step Plan for Teaching Argumentative Writing

February 7, 2016

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

Listen to this post as a podcast:

This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

For seven years, I was a writing teacher. Yes, I was certified to teach the full spectrum of English language arts—literature, grammar and usage, speech, drama, and so on—but my absolute favorite, the thing I loved doing the most, was teaching students how to write.

Most of the material on this site is directed at all teachers. I look for and put together resources that would appeal to any teacher who teaches any subject. That practice will continue for as long as I keep this up. But over the next year or so, I plan to also share more of what I know about teaching students to write. Although I know many of the people who visit here are not strictly English language arts teachers, my hope is that these posts will provide tons of value to those who are, and to those who teach all subjects, including writing.

So let’s begin with argumentative writing, or persuasive writing, as many of us used to call it. This overview will be most helpful to those who are new to teaching writing, or teachers who have not gotten good results with the approach you have taken up to now. I don’t claim to have the definitive answer on how to do this, but the method I share here worked pretty well for me, and it might do the same for you. If you are an experienced English language arts teacher, you probably already have a system for teaching this skill that you like. Then again, I’m always interested in how other people do the things I can already do; maybe you’re curious like that, too.

Before I start, I should note that what I describe in this post is a fairly formulaic style of essay writing. It’s not exactly the 5-paragraph essay, but it definitely builds on that model. I strongly believe students should be shown how to move past those kinds of structures into a style of writing that’s more natural and fitting to the task and audience, but I also think they should start with something that’s pretty clearly organized.

So here’s how I teach argumentative essay writing.

Step 1: Watch How It’s Done

One of the most effective ways to improve student writing is to show them mentor texts, examples of excellent writing within the genre students are about to attempt themselves. Ideally, this writing would come from real publications and not be fabricated by me in order to embody the form I’m looking for. Although most experts on writing instruction employ some kind of mentor text study, the person I learned it from best was Katie Wood Ray in her book Study Driven (links to the book: Bookshop.org | Amazon ).

Since I want the writing to be high quality and the subject matter to be high interest, I might choose pieces like Jessica Lahey’s Students Who Lose Recess Are the Ones Who Need it Most and David Bulley’s School Suspensions Don’t Work .

I would have students read these texts, compare them, and find places where the authors used evidence to back up their assertions. I would ask students which author they feel did the best job of influencing the reader, and what suggestions they would make to improve the writing. I would also ask them to notice things like stories, facts and statistics, and other things the authors use to develop their ideas. Later, as students work on their own pieces, I would likely return to these pieces to show students how to execute certain writing moves.

Step 2: Informal Argument, Freestyle

Although many students might need more practice in writing an effective argument, many of them are excellent at arguing in person. To help them make this connection, I would have them do some informal debate on easy, high-interest topics. An activity like This or That (one of the classroom icebreakers I talked about last year) would be perfect here: I read a statement like “Women have the same opportunities in life as men.” Students who agree with the statement move to one side of the room, and those who disagree move to the other side. Then they take turns explaining why they are standing in that position. This ultimately looks a little bit like a debate, as students from either side tend to defend their position to those on the other side.

Every class of students I have ever had, from middle school to college, has loved loved LOVED this activity. It’s so simple, it gets them out of their seats, and for a unit on argument, it’s an easy way to get them thinking about how the art of argument is something they practice all the time.

Step 3: Informal Argument, Not so Freestyle

Once students have argued without the support of any kind of research or text, I would set up a second debate; this time with more structure and more time to research ahead of time. I would pose a different question, supply students with a few articles that would provide ammunition for either side, then give them time to read the articles and find the evidence they need.

Next, we’d have a Philosophical Chairs debate (learn about this in my discussion strategies post), which is very similar to “This or That,” except students use textual evidence to back up their points, and there are a few more rules. Here they are still doing verbal argument, but the experience should make them more likely to appreciate the value of evidence when trying to persuade.

Before leaving this step, I would have students transfer their thoughts from the discussion they just had into something that looks like the opening paragraph of a written argument: A statement of their point of view, plus three reasons to support that point of view. This lays the groundwork for what’s to come.

Step 4: Introduction of the Performance Assessment

Next I would show students their major assignment, the performance assessment that they will work on for the next few weeks. What does this look like? It’s generally a written prompt that describes the task, plus the rubric I will use to score their final product.

Anytime I give students a major writing assignment, I let them see these documents very early on. In my experience, I’ve found that students appreciate having a clear picture of what’s expected of them when beginning a writing assignment. At this time, I also show them a model of a piece of writing that meets the requirements of the assignment. Unlike the mentor texts we read on day 1, this sample would be something teacher-created (or an excellent student model from a previous year) to fit the parameters of the assignment.

Step 5: Building the Base

Before letting students loose to start working on their essays, I make sure they have a solid plan for writing. I would devote at least one more class period to having students consider their topic for the essay, drafting a thesis statement, and planning the main points of their essay in a graphic organizer.

I would also begin writing my own essay on a different topic. This has been my number one strategy for teaching students how to become better writers. Using a document camera or overhead projector, I start from scratch, thinking out loud and scribbling down my thoughts as they come. When students see how messy the process can be, it becomes less intimidating for them. They begin to understand how to take the thoughts that are stirring around in your head and turn them into something that makes sense in writing.

For some students, this early stage might take a few more days, and that’s fine: I would rather spend more time getting it right at the pre-writing stage than have a student go off willy-nilly, draft a full essay, then realize they need to start over. Meanwhile, students who have their plans in order will be allowed to move on to the next step.

Step 6: Writer’s Workshop

The next seven to ten days would be spent in writer’s workshop, where I would start class with a mini-lesson about a particular aspect of craft. I would show them how to choose credible, relevant evidence, how to skillfully weave evidence into an argument, how to consider the needs of an audience, and how to correctly cite sources. Once each mini-lesson was done, I would then give students the rest of the period to work independently on their writing. During this time, I would move around the room, helping students solve problems and offering feedback on whatever part of the piece they are working on. I would encourage students to share their work with peers and give feedback at all stages of the writing process.

If I wanted to make the unit even more student-centered, I would provide the mini-lessons in written or video format and let students work through them at their own pace, without me teaching them. (To learn more about this approach, read this post on self-paced learning ).

As students begin to complete their essays, the mini-lessons would focus more on matters of style and usage. I almost never bother talking about spelling, punctuation, grammar, or usage until students have a draft that’s pretty close to done. Only then do we start fixing the smaller mistakes.

Step 7: Final Assessment

Finally, the finished essays are handed in for a grade. At this point, I’m pretty familiar with each student’s writing and have given them verbal (and sometimes written) feedback throughout the unit; that’s why I make the writer’s workshop phase last so long. I don’t really want students handing in work until they are pretty sure they’ve met the requirements to the best of their ability. I also don’t necessarily see “final copies” as final; if a student hands in an essay that’s still really lacking in some key areas, I will arrange to have that student revise it and resubmit for a higher grade.

So that’s it. If you haven’t had a lot of success teaching students to write persuasively, and if the approach outlined here is different from what you’ve been doing, give it a try. And let’s keep talking: Use the comments section below to share your techniques or ask questions about the most effective ways to teach argumentative writing.

Want this unit ready-made?

If you’re a writing teacher in grades 7-12 and you’d like a classroom-ready unit like the one described above, including mini-lessons, sample essays, and a library of high-interest online articles to use for gathering evidence, take a look at my Argumentative Writing unit. Just click on the image below and you’ll be taken to a page where you can read more and see a detailed preview of what’s included.

What to Read Next

Categories: Instruction , Podcast

Tags: English language arts , Grades 6-8 , Grades 9-12 , teaching strategies

58 Comments

This is useful information. In teaching persuasive speaking/writing I have found Monroe’s Motivated sequence very useful and productive. It is a classic model that immediately gives a solid structure for students.

Thanks for the recommendation, Bill. I will have to look into that! Here’s a link to more information on Monroe’s Motivated sequence, for anyone who wants to learn more: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/MonroeMotivatedSequence.htm

What other sites do you recommend for teacher use on providing effective organizational structure in argumentative writing? As a K-12 Curriculum Director, I find that when teachers connect with and understand the organizational structure, they are more effective in their teaching/delivery.

Hey Jessica, in addition to the steps outlined here, you might want to check out Jenn’s post on graphic organizers . Graphic organizers are a great tool that you can use in any phase of a lesson. Using them as a prewrite can help students visualize the argument and organize their thoughts. There’s a link in that post to the Graphic Organizer Multi-Pack that Jenn has for sale on her Teachers Pay Teachers site, which includes two versions of a graphic organizer you can use specifically for argument organization. Otherwise, if there’s something else you had in mind, let us know and we can help you out. Thanks!

Dear Jennifer Gonzalez,

You are generous with your gift of lighting the path… I hardly ever write (never before) , but I must today… THANK YOU… THANK YOU….THANK YOU… mostly for reading your great teachings… So your valuable teachings will even be easy to benefit all the smart people facing challenge of having to deal with adhd…

I am not a teacher… but forever a student…someone who studied English as 2nd language, with a science degree & adhd…

You truly are making a difference in our World…

Thanks so much, Rita! I know Jenn will appreciate this — I’ll be sure to share with her!

Love it! Its simple and very fruitful . I can feel how dedicated you are! Thanks alot Jen

Great examples of resources that students would find interesting. I enjoyed reading your article. I’ve bookmarked it for future reference. Thanks!

You’re welcome, Sheryl!

Students need to be writing all the time about a broad range of topics, but I love the focus here on argumentative writing because if you choose the model writing texts correctly, you can really get the kids engaged in the process and in how they can use this writing in real-world situations!

I agree, Laura. I think an occasional tight focus on one genre can help them grow leaps and bounds in the skills specific to that type of writing. Later, in less structured situations, they can then call on those skills when that kind of thinking is required.

This is really helpful! I used it today and put the recess article in a Google Doc and had the kids identify anecdotal, statistic, and ‘other’ types of evidence by highlighting them in three different colors. It worked well! Tomorrow we’ll discuss which of the different types of evidence are most convincing and why.

Love that, Shanna! Thanks for sharing that extra layer.

Greetings Ms. Gonzales. I was wondering if you had any ideas to help students develop the cons/against side of their argument within their writing? Please advise. Thanks.

Hi Michael,

Considering audience and counterarguments are an important part of the argumentative writing process. In the Argumentative Writing unit Jenn includes specific mini-lessons that teach kids how, when and where to include opposing views in their writing. In the meantime, here’s a video that might also be helpful.

Hi, Thank you very much for sharing your ideas. I want to share also the ideas in the article ‘Already Experts: Showing Students How Much They Know about Writing and Reading Arguments’ by Angela Petit and Edna Soto…they explain a really nice activity to introduce argumentative writing. I have applied it many times and my students not only love it but also display a very clear pattern as the results in the activity are quite similar every time. I hope you like it.

Lorena Perez

I’d like to thank you you for this excellence resource. It’s a wonderful addition to the informative content that Jennifer has shared.

What do you use for a prize?

I looked at the unit, and it looks and sounds great. The description says there are 4 topics. Can you tell me the topics before I purchase? We start argument in 5th grade, and I want to make sure the topics are different from those they’ve done the last 5 years before purchasing. Thanks!

Hi Carrie! If you go to the product page on TPT and open up the preview, you’ll see the four topics on the 4th page in more detail, but here they are: Social Networking in School (should social media sites be blocked in school?), Cell Phones in Class, Junk Food in School, and Single-Sex Education (i.e., genders separated). Does that help?

I teach 6th grade English in a single gendered (all-girls) class. We just finished an argument piece but I will definitely cycle back your ideas when we revisit argumentation. Thanks for the fabulous resources!

Glad to hear it, Madelyn!

I’m not a writing teacher and honestly haven’t been taught on how to teach writing. I’m a history teacher. I read this and found it helpful but have questions. First I noticed that amount of time dedicated to the task in terms of days. My questions are how long is a class period? I have my students for about 45 minutes. I also saw you mentioned in the part about self-paced learning that mini-lessons could be written or video format. I love these ideas. Any thoughts on how to do this with almost no technology in the room and low readers to non-readers? I’m trying to figure out how to balance teaching a content class while also teaching the common core skills. Thank you for any consideration to my questions.

Hey Jones, To me, a class period is anywhere from 45 minutes to an hour; definitely varies from school to school. As for the question about doing self-paced with very little tech? I think binders with written mini-lessons could work well, as well as a single computer station or tablet hooked up to a class set of videos. Obviously you’d need to be more diligent about rotating students in and out of these stations, but it’s an option at least. You might also give students access to the videos through computers in other locations at school (like the library) and give them passes to watch. The thing about self-paced learning, as you may have seen in the self-paced post , is that if students need extra teacher support (as you might find with low readers or non-readers), they would spend more one-on-one time with the teacher, while the higher-level students would be permitted to move more quickly on their own. Does that help?

My primary goal for next semester is to increase academic discussion and make connections from discussion to writing, so I love how you launch this unit with lessons like Philosophical Chairs. I am curious, however, what is the benefit of the informal argument before the not-so-informal argument? My students often struggle to listen to one another, so I’m wondering if I should start with the more formal, structured version. Or, am I overthinking the management? Thanks so much for input.

Yikes! So sorry your question slipped through, and we’re just now getting to this, Sarah. The main advantage of having kids first engage in informal debate is that it helps them get into an argumentative mindset and begin to appreciate the value of using research to support their claims. If you’ve purchased the unit, you can read more about this in the Overview.

My 6th graders are progressing through their argumentative essay. I’m providing mini lessons along the way that target where most students are in their essay. Your suggestions will be used. I’ve chosen to keep most writing in class and was happy to read that you scheduled a lot of class time for the writing. Students need to feel comfortable knowing that writing is a craft and needs to evolve over time. I think more will get done in class and it is especially important for the struggling writers to have peers and the teacher around while they write. Something that I had students do that they liked was to have them sit in like-topic groups to create a shared document where they curated information that MIGHT be helpful along the way. By the end of the essay, all will use a fantastic add-on called GradeProof which helps to eliminate most of the basic and silly errors that 6th graders make.

Debbi! I LOVE the idea of a shared, curated collection of resources! That is absolutely fantastic! Are you using a Google Doc for this? Other curation tools you might consider are Padlet and Elink .

thanks v much for all this information

Love this! What do you take as grades in the meantime? Throughout this 2 week stretch?

Ideally, you wouldn’t need to take grades at all, waiting until the final paper is done to give one grade. If your school requires more frequent grades, you could assign small point values for getting the incremental steps done: So in Step 3 (when students have to write a paragraph stating their point of view) you could take points for that. During the writer’s workshop phase, you might give points for completion of a rough draft and participation points for peer review (ideally, they’d get some kind of feedback on the quality of feedback they give to one another). Another option would be to just give a small, holistic grade for each week based on the overall integrity of their work–are they staying on task? Making small improvements to their writing each day? Taking advantage of the resources? If students are working diligently through the process, that should be enough. But again, the assessment (grades) should really come from that final written product, and if everyone is doing what they’re supposed to be doing during the workshop phase, most students should have pretty good scores on that final product. Does that help?

Awesome Step 2! Teaching mostly teenagers in Northern Australia I find students’ verbal arguments are much more finely honed than their written work.

To assist with “building the base” I’ve always found sentence starters an essential entry point for struggling students. We have started using the ‘PEARL’ method for analytical and persuasive writing.

If it helps here a free scaffold for the method:

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/FREE-Paragraph-Scaffold-PEEL-to-PEARL-3370676

Thanks again,

Thank you for sharing this additional resource! It’s excellent!

I’ve been scouring the interwebs looking for some real advice on how I can help my struggling 9th grader write better. I can write. Since it comes naturally for me, I have a hard time breaking it down into such tiny steps that he can begin to feel less overwhelmed. I LOVE the pre-writing ideas here. My son is a fabulous arguer. I need to help him use those powers for the good of his writing skills. Do you have a suggestion on what I else I can be using for my homeschooled son? Or what you may have that could work well for home use?

Hi Melinda,

You might be interested in taking a look at Jenn’s Argumentative Writing unit which she mentions at the end of the post . Hope this helps!

Mam it would be good if you could post some steps of different writing and some samples as well so it can be useful for the students.

Hi Aalia! My name is Holly, and I work as a Customer Experience Manager for Cult of Pedagogy. It just so happens that in the near future, Jenn is going to release a narrative writing unit, so keep an eye out for that! As far as samples, the argumentative writing unit has example essays included, and I’m sure the narrative unit will as well. But, to find the examples, you have to purchase the unit from Teachers Pay Teachers.

I just want to say that this helped me tremendously in teaching argument to 8th Graders this past school year, which is a huge concept on their state testing in April. I felt like they were very prepared, and they really enjoyed the verbal part of it, too! I have already implemented these methods into my unit plan for argument for my 11th grade class this year. Thank you so much for posting all of these things! : )

-Josee` Vaughn

I’m so glad to hear it, Josee!!

Love your blog! It is one of the best ones.

I am petrified of writing. I am teaching grade 8 in September and would love some suggestions as I start planning for the year. Thanks!

This is genius! I can’t wait to get started tomorrow teaching argument. It’s always something that I have struggled with, and I’ve been teaching for 18 years. I have a class of 31 students, mostly boys, several with IEPs. The self-paced mini-lessons will help tremendously.

So glad you liked it, Britney!

My students will begin the journey into persuasion and argument next week and your post cemented much of my thinking around how to facilitate the journey towards effective, enthusiastic argumentative writing.

I use your rubrics often to outline task expectations for my students and the feedback from them is how useful breaking every task into steps can be as they are learning new concepts.

Additionally, we made the leap into blogging as a grade at https://mrsdsroadrunners.edublogs.org/2019/01/04/your-future/ It feels much like trying to learn to change a tire while the car is speeding down the highway. Reading your posts over the past years was a factor in embracing the authentic audience. Thank You! Trish

I love reading and listening to your always helpful tips, tricks, and advice! I was wondering if you had any thoughts on creative and engaging ways to have students share their persuasive writing? My 6th students are just finishing up our persuasive writing where we read the book “Oh, Rats” by Albert Marrin and used the information gathered to craft a persuasive piece to either eliminate or protect rats and other than just reading their pieces to one another, I have been trying to think of more creative ways to share. I thought about having a debate but (un)fortunately all my kids are so sweet and are on the same side of the argument – Protect the Rats! Any ideas?

Hi Kiley! Thanks for the positive feedback! So glad to hear that you are finding value in Cult of Pedagogy! Here are a few suggestions that you may be interested in trying with your students:

-A gallery walk: Students could do this virtually if their writing is stored online or hard copies of their writing. Here are some different ways that you could use gallery walks: Enliven Class Discussions With Gallery Walks

-Students could give each other feedback using a tech tool like Flipgrid . You could assign students to small groups or give them accountability partners. In Flipgrid, you could have students sharing back and forth about their writing and their opinions.

I hope this helps!

I love the idea of mentor texts for all of these reading and writing concepts. I saw a great one on Twitter with one text and it demonstrated 5-6 reasons to start a paragraph, all in two pages of a book! Is there a location that would have suggestions/lists of mentor texts for these areas? Paragraphs, sentences, voice, persuasive writing, expository writing, etc. It seems like we could share this info, save each other some work, and curate a great collection of mentor text for English Language Arts teachers. Maybe it already exists?

Hi Maureen,

Here are some great resources that you may find helpful:

Craft Lessons Second Edition: Teaching Writing K-8 Write Like This: Teaching Real-World Writing Through Modeling and Mentor Texts and Mentor Texts, 2nd edition: Teaching Writing Through Children’s Literature, K-6

Thanks so much! I’ll definitely look into these.

I love the steps for planning an argumentative essay writing. When we return from Christmas break, we will begin starting a unit on argumentative writing. I will definitely use the steps. I especially love Step #2. As a 6th grade teacher, my students love to argue. This would set the stage of what argumentative essay involves. Thanks for sharing.

So glad to hear this, Gwen. Thanks for letting us know!

Great orientation, dear Jennifer. The step-by-step carefully planned pedagogical perspectives have surely added in the information repository of many.

Hi Jennifer,

I hope you are well. I apologise for the incorrect spelling in the previous post.

Thank you very much for introducing this effective instruction for teaching argumentative writing. I am the first year PhD student at Newcastle University, UK. My PhD research project aims to investigate teaching argumentative writing to Chinese university students. I am interested in the Argumentative Writing unit you have designed and would like to buy it. I would like to see the preview of this book before deciding to purchase it. I clicked on the image BUT the font of the preview is so small and cannot see the content clearly. I am wondering whether it could be possible for you to email me a detailed preview of what’s included. I would highly appreciate if you could help me with this.

Thank you very much in advance. Looking forward to your reply.

Take care and all the very best, Chang

Hi Chang! Jenn’s Argumentative Writing Unit is actually a teaching unit geared toward grades 7-12 with lessons, activities, etc. If you click here click here to view the actual product, you can click on the green ‘View Preview’ button to see a pretty detailed preview of what’s offered. Once you open the preview, there is the option to zoom in so you can see what the actual pages of the unit are like. I hope this helps!

Great Content!

Another teacher showed me one of your posts, and now I’ve read a dozen of them. With teaching students to argue, have you ever used the “What’s going on in this picture?” https://www.nytimes.com/column/learning-whats-going-on-in-this-picture?module=inline I used it last year and thought it was a non-threatening way to introduce learners to using evidence to be persuasive since there was no text.

I used to do something like this to help kids learn how to make inferences. Hadn’t thought of it from a persuasive standpoint. Interesting.

this is a very interesting topic, thanks!

Hi! I’m a teacher too! I was looking for inspiration and I found your article and thought you might find this online free tool interesting that helps make all students participate meaningfully and engage in a topic. https://www.kialo-edu.com/

This tool is great for student collaboration and to teach argumentative writing in an innovative way. I hope this helps!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Writing curriculum

Argumentative Writing Unit

Writing prompts, lesson plans, webinars, mentor texts and a culminating contest, all to inspire your students to tell us what matters to them.

By The Learning Network

Unit Overview

On our site, we’ve been offering teenagers ways to tell the world what they think for over 20 years. Our student writing prompt forums encourage them to weigh in on current events and issues daily, while our contests have offered an annual outlet since 2014 for formalizing those opinions into evidence-based essays.

In this unit, we’re bringing together all the resources we’ve developed along the way to help students figure out what they want to say, and how to say it effectively.

Here is what this unit offers, but we would love to hear from both teachers and students if there is more we could include. Let us know in the comments, or by writing to [email protected].

Start With Our Prompts for Argumentative Writing

How young is too young to use social media? Should students get mental health days off from school? Is $1 billion too much money for any one person to have?

These are the kinds of questions we ask every day on our site. In 2017 we published a list of 401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing categorized to provoke thinking on aspects of contemporary life from social media to sports, politics, gender issues and school. In 2021, we followed it up with 300 Questions and Images to Inspire Argument Writing , which catalogs all our argument-focused Student Opinion prompts since then, plus our more accessible Picture Prompts.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Teacher Off Duty

Resources to help you teach better and live happier

My Favorite Lesson Plan for Teaching Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning

August 29, 2018 by Jeanne Wolz 2 Comments

Let’s face it. Teaching argumentative writing is hard .

If you’re looking for a full argumentative writing unit plan , I’ve got you covered–>

It’s not that teenagers aren’t good at arguing. Teenagers are very good at arguing. In fact, they may be the people that practice arguing the most.

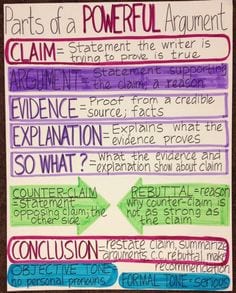

The challenge lies in learning the different parts of a basic argument–the claim, the evidence, and the reasoning–when each of them are such abstract concepts. By understanding what each of them are, we’re able to critique arguments and make our own better. But without a concrete way to talk about them, it’s like gesturing wildly at a class and hoping they’ll catch your drift (maybe that’s half the reason argumentative units are so exhausting…).

What I knew I needed was some sort of analogy, some visual for students that we could keep revisiting each time we reinforced these ideas. I went through several years of thinking about it before I finally came up with something that seemed to work.

I thought some sort of hook analogy might work–maybe a visual with strings and clips to show how reasoning attaches your evidence to your claim. I followed a fantastic Lucy Calkins lesson once where I wrote evidence on pieces of paper and lined them up on the floor, encouraging students to explain how each piece of evidence got me from claim a to claim b (which magically gave me powers to hop along the evidence). This was an effective one-off lesson, but it was difficult to revisit.

And then, one year it came to me. An analogy to revisit over and over again. That analogy was:

Making an argument is like taking your reader on a roller coaster.

Ok, ok, it may not seem like much, but I found there was a lot of value to be squeezed out of this visual.

I wanted to share with you how I use it so that maybe you can get some ideas on how to make these abstract-logic-intensive units a little more concrete, too.

Here’s what I do to introduce it:

Claims, Evidence, and Reasoning Introduction Lesson Plan

Mini-lesson: explain the analogy.

I explain: “In order for your reader to stay with you, you need to strap him into that roller coaster argument properly for the entire time. How do you do that?

Stating your claim is like sitting your reader down on your roller coaster. It’s your first step.

Then, you give evidence. Your evidence is like putting on one strap of the seatbelt.

Your reasoning is like putting on the other strap.

Mentioning your claim at the end of this process is like snapping it all together.

And each part is crucial to keep your reader from falling off your thinking.

What do you think happens if you forget one of these steps?

Yup. You gotta have it all in order for your reader to stay with you.”

Sometimes, as I’m explaining this, I even act it out with a back pack and a chair to make it even more visual. I act out sitting in the chair (for stating your claim), putting on one strap (for introducing evidence), and putting on the other strap (for using reasoning to connect it back to the claim). After introducing the comment, I also like to give an example argument for students as I’m acting it out so they can start identifying each part of the argument.

Work-time: Act it Out as Students Make Arguments

After explaining it, we practice. I like to follow it up with verbal arguments with an activity like philosophical chairs so students can have repeated opportunities to both hear examples of arguments and try them themselves.

As students make their arguments, I continue to act it out. Students talk, and I follow along with the motions.

If they miss a step (which they almost always do in the beginning), I milk it. I yell and fall off the chair and make as dramatic a scene out of it as I can). Afterwards, we talk about what they forgot to do that made me fall off their coaster/argument and die.

And then we try again and repeat!

Extension: Have Students Act it Out for Each Other

After you’ve acted it out a couple times, have the rest of the class act out what they hear.

So as students hear the person speaking state a claim, they all sit down. As the person gives some evidence, they put on a strap, etc. And if they forget a step and finish….well, you may want to warn your neighboring classrooms. This can help students tune into the structure of others’ arguments in addition to helping keep each other accountable.

Twist: Invert the Lesson

I’ve actually begun to move the mini-lesson to the middle of this lesson. I’ve found it helps for students to create their own arguments before we talk about argument structure, because it gives context for talking about Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning. Plus, it honors the knowledge that students already have about making arguments–because they have a lot . So we start Philosophical Chairs, stop 1/3 through, chat about roller coasters, and then continue on. It’s a lot for a 45 minute period, but doable.

Click here if you want my full lesson plan, powerpoint, and handout that I use for introducing this analogy with philosophical chairs–complete with dramatic pictures of cartoon people flying off of roller coasters.. (This lesson actually comes from my argumentative unit, which will be released on TPT in September. If you’d be interested in hearing more about that unit and when it’s available, click here!)

Reinforce it Throughout the Unit

For the rest of the unit, I keep coming back to this analogy. We use it to talk about weak evidence (puny straps made of yarn) and strong evidence (steel bars), as well as the need for reasoning to match the strength of the evidence (uneven straps are awkward). When I give feedback to students, I always put it back in the context of the roller coaster. By the end, the idea is that the lack of a claim, evidence, or reasoning would make anyone in class scream (and for once, not just me!)—or at the very least, that everyone is much more aware of it.

________________

And that’s that! It’s become one of my favorite lessons in the argumentative unit, because no matter how crazy my students look at me the first time we talk about it, we’ve been able to come back to it over and over again during the unit. It’s given us a way to make something visual that always seems incredibly, frustratingly abstract.

Pin this to remember!

In the meantime, let me know in the comments below if you’ve got tips for teaching Claims, Evidence, and Reasoning, or if you were able to try this with your students. It seriously makes my day to hear from you, and I love hearing stories and new ideas!!

Some other resources you may be interested in:

This lesson is actually part of a full unit plan you can find here . One of my all-time favorite units I’ve ever taught, this argumentative unit starts with students identifying an issue they care most about, and then identifying who they can write to to change it. The rest of the 25, CCSS-aligned lessons take them through writing letters that they’ll mail at the end of the unit. Teach students how to argue well while learning to use their voice to make real change. Check it out here!

A few of my Pinterest Boards in particular (or all of them ):

Teaching Writing Pinterest Board

ELA Resources Pinterest Board

Lesson Ideas Pinterest Board

Social Studies Resources Pinterest Board

Share this:

Thank you!!! This is amazing – I really appreciate it!! 🙂

Yay–thanks for your feedback, Tara! I hope your students enjoy!!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Looking for something.

- Resource Shop

- Partnerships

Information

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

New Teacher Corner

New teachers are my favorite teachers..

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Only 100 Left! Get FREE Timeline Posters Sent Right to Your School ✨

Making a Claim: Teaching Students Argument Writing Through Close Reading

We know students in the middle grades can make an argument to throw a pizza party, to get out of[…] Continue Reading

We know students in the middle grades can make an argument to throw a pizza party, to get out of detention or to prove a point. So, why do they find it hard to craft strong arguments from text? The skill of argumentative or persuasive writing is a skill that’s easier said than done.

Close reading naturally lends itself to teaching argumentative writing. To be sure, it’s not the only way to culminate a close-reading lesson, but as students read, reread and break down text, analyzing author’s arguments and crafting their own can come naturally.

Argumentative writing isn’t persuasion, and it’s not about conflict or winning. Instead, it’s about creating a claim and supporting that claim with evidence. For example, in this set of writing samples from Achieve the Core , fifth grade students read an article about homework and wrote an argument in response to the question How much homework is too much? One student wrote the claim: I think that students should have enough homework but still have time for fun. Students in third grade should start having 15 minutes a night and work up to a little over an hour by sixth grade. The student goes on to support her claim with evidence from the article she read. It builds responsibility and gives kids a chance to practice.

Here are four ways to build your students’ ability to write arguments through close reading.

Choose Text Wisely

I don’t think I can say it enough: The most important part of planning close reading is choosing the text . If you want students to be able to create and support an argument, the text has to contain evidence—and lots of it. Look for texts or passages that are worth reading deeply (read: well written with intriguing, worthwhile ideas) and that raise interesting questions that don’t have a right or wrong answer.

PEELS: Help Students Structure Their Arguments

Before students can get creative with their writing, make sure they can structure their arguments. In the PEELS approach, students need to:

- Make a point.

- Support it with evidence (and examples).

- Explain their evidence.

- Link their points.

- Maintain a formal style.

Check out this Teachers Pay Teachers resource (free) for an explanation and graphic organizer to use with students.

Provide Time for Collaboration

When students are allowed to talk about their writing, they craft stronger arguments because they’re provided time to narrow and sharpen their ideas. In his book, Translating Talk Into Text (2014) Thomas McCann outlines two types of conversation that help students prepare to write.

- Exploratory discussions: These small-group discussions provide space for students to find out what others are thinking and explore the range of possibilities. These conversations should happen after students have read closely, with the goal of building an understanding of what ideas or claims are present within a text.

- Drafting discussions: After students have participated in exploratory discussion, drafting discussions are a chance for students to come together as a whole group to share and refine their ideas. Drafting discussions start by sharing arguments that students discussed in the exploratory discussions, then provide time for students to explore the arguments and challenge one another. The goal is for students to end the discussion with a clear focus for their writing.

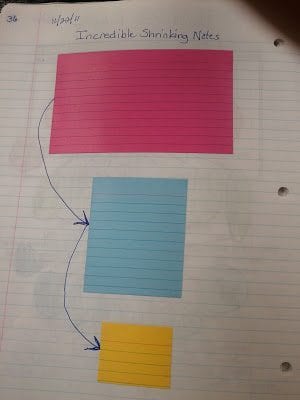

The Incredible Shrinking Argument: Help Students Synthesize

Once students are writing, probably the biggest challenge becomes whittling an argument down to the essentials. To help students do this, have them write their argument on a large sticky note (or in a large text box). Then, have them whittle it twice by revising it and rewriting it on smaller sticky notes (or text boxes) to get the excess ideas or details out. By the time they’re rewriting it on the smallest sticky note (or textbox), they’ll be forced to identify the bones of their argument. (See The Middle School Mouth blog for more on this strategy.)

Samantha Cleaver is an education writer, former special education teacher and avid reader. Her book, Every Reader a Close Reader, is scheduled to be published by Rowman and Littlefield in 2015. Read more at her blog www.cleaveronreading.wordpress.com .

You Might Also Like

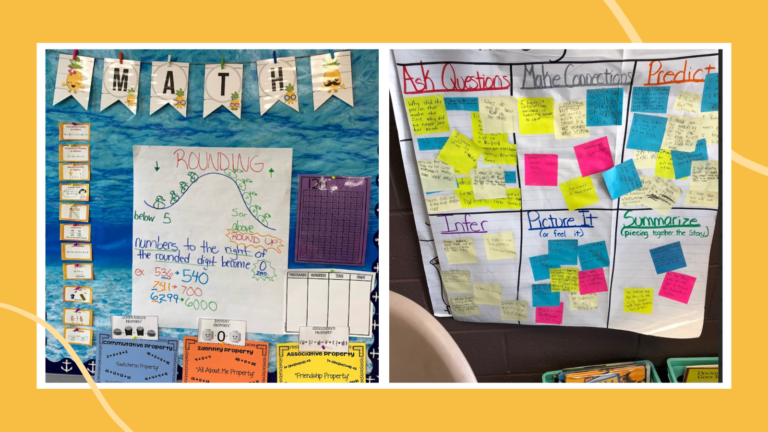

Anchor Charts 101: Why and How To Use Them

It's the chart you make once and use 100 times. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Strategies for Teaching Argument Writing

Three simple ways a ninth-grade teacher scaffolds argument writing for students.

Your content has been saved!

My ninth-grade students love to argue. They enjoy pushing back against authority, sharing their opinions, and having those opinions validated by their classmates. That’s no surprise—it’s invigorating to feel right about a hot-button topic. But through the teaching of argument writing, we can show our students that argumentation isn’t just about convincing someone of your viewpoint—it’s also about researching the issues, gathering evidence, and forming a nuanced claim.

Argument writing is a crucial skill for the real world, no matter what future lies ahead of a student. The Common Core State Standards support the teaching of argument writing , and students in the elementary grades on up who know how to support their claims with evidence will reap long-term benefits.

Argument Writing as Bell Work

One of the ways I teach argument writing is by making it part of our bell work routine, done in addition to our core lessons. This is a useful way to implement argument writing in class because there’s no need to carve out two weeks for a new unit.

Instead, at the bell, I provide students with an article to read that is relevant to our coursework and that expresses a clear opinion on an issue. They fill out the first section of the graphic organizer I’ve included here, which helps them identify the claim, supporting evidence, and hypothetical counterclaims. After three days of reading nonfiction texts from different perspectives, their graphic organizer becomes a useful resource for forming their own claim with supporting evidence in a short piece of writing.

The graphic organizer I use was inspired by the resources on argument writing provided by the National Writing Project through the College, Career, and Community Writers Program . They have resources for elementary and secondary teachers interested in argument writing instruction. I also like to check Kelly Gallagher’s Article of the Week for current nonfiction texts.

Moves of Argument Writing

Another way to practice argument writing is by teaching students to be aware of, and to use effectively, common moves found in argument writing. Joseph Harris’s book Rewriting: How to Do Things With Texts outlines some common moves:

- Illustrating: Using examples, usually from other sources, to explain your point.

- Authorizing: Calling upon the credibility of a source to help support to your argument.

- Borrowing: Using the terminology of other writers to help add legitimacy to a point.

- Extending: Adding commentary to the conversation on the issue at hand.

- Countering: Addressing opposing arguments with valid solutions.

Teaching students to identify these moves in writing is an effective way to improve reading comprehension, especially of nonfiction articles. Furthermore, teaching students to use these moves in their own writing will make for more intentional choices and, subsequently, better writing.

Argument Writing With Templates

Students who purposefully read arguments with the mindset of a writer can be taught to recognize the moves identified above and more. Knowing how to identify when and why authors use certain sentence starters, transitions, and other syntactic strategies can help students learn how to make their own point effectively.

To supplement our students’ knowledge of these syntactic strategies, Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein recommend writing with templates in their book They Say, I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing . Graff and Birkenstein provide copious templates for students to use in specific argument writing scenarios. For example, consider these phrases that appear commonly in argument writing:

- On the one hand...

- On the other hand...

- I agree that...

- This is not to say that...

If you’re wary of having your students write using a template, I once felt the same way. But when I had my students purposefully integrate these words into their writing, I saw a significant improvement in their argument writing. Providing students with phrases like these helps them organize their thoughts in a way that better suits the format of their argument writing.

When we teach students the language of arguing, we are helping them gain traction in the real world. Throughout their lives, they’ll need to convince others to support their goals. In this way, argument writing is one of the most important tools we can teach our students to use.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Jenna Copper

Teaching Secondary English Language Arts

Subscribe to receive freebies, news, & promos directly to your inbox.

5 Strategies to Teach Students How to Identify and Analyze Strong Argument Examples

Before students can write strong persuasive essays, they must be able to identify what makes a powerful argument. Therefore, before diving into an argumentative writing unit, I complete an analyzing arguments unit first. In this unit, students learn how to write strong claims, how to support claims with evidence, how to use counterarguments to strengthen arguments, and how to identify and avoid fallacies. I found the best way to teach these elements is by analyzing argument examples from other writers and speakers.

This type of analysis is consistent with the objectives for the AP English Language and Composition course. In this blog post, I’m going to share five strategies that help students not just identify, but analyze arguments so that they’re primed and ready to write their own strong arguments at the conclusion.

1. Differentiate strong claims from weak claims with small group work

The first step in writing a sound argument is to understand what makes a strong argument. This means that students must understand the elements of a strong claim. To begin, a strong claim includes an arguable stance on a topic and provides reasoning to support that stance. If it’s missing the reasoning component, it’s likely a weak claim. If it’s missing the defendable stance part, it’s likely not a claim at all, but a fact.

Because these can be tricky, students may find that talking through some examples in small groups can be really helpful. This way, I encourage students to apply the above definitions to a variety of example statements. An even better way to practice is to instruct students to rewrite facts or weak claims into strong claims. This gives students practice identifying types of claims and creating their own from ones that are strong enough to become a thesis statement in an essay.

2. Collect substantial, varied, and valid evidence with an evidence scavenger hunt

One of my favorite activities to teach students about using strong evidence to support strong claims is an evidence scavenger hunt. An evidence scavenger hunt teaches students that evidence must be substantial, varied, and valid in order to support a claim. So how does this scavenger hunt work?

First, give students a strong claim. Then, instruct students either individually or with a partner to find a piece of evidence that could support that claim. I give students evidence categories, such as anecdotes, observations, statistics, etc. to encourage them to find varied evidence. Then, I turn on a timer for about 10 minutes and ask students to go around the room, finding evidence from their classmates for each category. You can give bonus points to the students who collect the most in the time frame.

This activity serves as a metaphor for how rigorous evidence collection is. They have to find enough varied evidence to support a claim. It also gives a great opportunity to discuss which evidence most effectively supported the claim. Ultimately, this activity can lead to a discussion about how important it is to connect evidence to claims when writing an argument.

3. Predict counterarguments and make counterclaims with a scenario

One of the most challenging tasks for students is predicting and rebuffing counterclaims. To show sophistication and complexity, some students will try to address counterclaims in their written arguments. The problem? If not approached tactfully, this attempt can end up working against their own arguments. It’s not enough to address or concede a counterargument. Rather, students must counter the counterclaim.

One of my favorite strategies to teach students how to predict and address counterclaims is with a scenario activity. Choosing a scenario that students could encounter in real life makes this more practical and, therefore, easier for them to understand.

Here are some ideas:

- You want to convince your friends that s/he should play ________(a sport)___________ or be involved in ________(an extracurricular activity)________________.

- You want to persuade your friends to go to a haunted house at Halloween.

- You want to assure your parents that they can trust you with a car.

Once you give students the scenario(s). Ask them to predict every counterargument they can

imagine. Then, they should identify which counterargument(s) are the strongest. Finally, give them practice identifying how they could counter the counterargument. This practice sets them up for identifying the strongest counterarguments in their own writing and effectively rebuking those counterarguments.

4. Create visual fallacies

I know this may seem counterintuitive at first, but a great way to teach students to avoid logical fallacies is to have them create fallacies. One of my favorite activities is to instruct students to create their logical fallacy ad campaign. If students go into the assignment, knowing their intention is to deceive or distort with a fallacy, they’re priming themselves to recognize when fallacies unintentionally occur in their own writing or intentionally in the real world.

Even better, if you ask students to create a strong visual argument to go with their logical fallacy, they’ll be able to compare the difference. This type of analysis requires students to put everything that goes into a strong argument to practice making it a great culminating project. Plus, the visual aspect gives students a chance to analyze the impact of visual arguments.

Students can use free design websites, like Canva or Adobe Spark Video , to create their advertisements. The best part is presenting these advertisements to the class. Providing rationale for their decisions shows they understand what makes and breaks a strong argument.

If you’re looking for more activities to teach logical fallacies, including visual notes and quiz, check out my logical fallacies mini-unit .

5. Analyze other strong argument examples with silent discussions

Mentor texts serve as great examples for students to analyze and replicate. The good news is that there are so many options available, you will find great examples to use with students. Then, I love parking the mentor text with a silent discussion activity.

A silent discussion is an activity that requires all of their discussion in written format, either handwriting or typing. This activity encourages students to be focused on their analysis and deliberate about their participation. Give students a written copy of the argument either on a big piece of paper for them to write on or on a digital discussion forum or board. Then, give them a set amount of time to discuss the argument. Ten minutes is a great starting point.

I like to show students examples of how strong arguments are organized. For example, I’ll find examples of an argument that uses comparison and contrast, cause and effect, or definition to organize. Then, I’ll have them analyze how the argument was strengthened by their format. You can use any analysis focus for this activity. The key is to give students an opportunity to read strong arguments.

If you like these strategies, check out my analyzing arguments unit . This unit includes all the above strategies, and many more. Plus, you’ll have all the directions, activities, and rubrics that go with it. If you’re working toward an argument writing unit, my argument writing workbook pairs perfectly to support students from analysis to direct practice.

For more reading:

How to Teach the Argument Essay

How to Teach MLA and APA

Share this:

Uncategorized high school english , reading , teaching reading , teaching writing , writing

You may also like

4 Ways to Add Fun and Games to Your ELA Classroom

How to Teach Your Students to Write Strong Argumentative Essays

Teacher Professional Development for Tomorrow

Get started by downloading my free resources.

FREE WRITING LESSON GUIDE

How to teach argument, informative, and narrative writing

GET ORGANIZED

FREE READING UNIT PLANNER

How to create an engaging reading unit quickly and efficiently

GET PLANNING

FREE DIGITAL ART TUTORIAL

How to create digital art for any text using Google Slides

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Can You Convince Me? Developing Persuasive Writing

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

Persuasive writing is an important skill that can seem intimidating to elementary students. This lesson encourages students to use skills and knowledge they may not realize they already have. A classroom game introduces students to the basic concepts of lobbying for something that is important to them (or that they want) and making persuasive arguments. Students then choose their own persuasive piece to analyze and learn some of the definitions associated with persuasive writing. Once students become aware of the techniques used in oral arguments, they then apply them to independent persuasive writing activities and analyze the work of others to see if it contains effective persuasive techniques.

Featured Resources

| : Students can use this online interactive tool to map out an argument for their persuasive essay. | |

| : This handy PowerPoint presentation helps students master the definition of each strategy used in persuasive writing. | |

| : Students can apply what they know about persuasive writing strategies by evaluating a persuasive piece and indicating whether the author used that strategy, and–if so–explaining how. |

From Theory to Practice

- Students can discover for themselves how much they already know about constructing persuasive arguments by participating in an exercise that is not intimidating.

- Progressing from spoken to written arguments will help students become better readers of persuasive texts.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

Materials and Technology

- Computers with Internet access

- PowerPoint

- LCD projector (optional)

- Chart paper or chalkboard

- Sticky notes

- Persuasive Strategy Presentation

- Persuasion Is All Around You

- Persuasive Strategy Definitions

- Check the Strategies

- Check the Strategy

- Observations and Notes

- Persuasive Writing Assessment

Preparation

| 1. | Prepare for the game students play during Session 1. Divide the class into teams of four or five. Choose a prize for the winning team (e.g., extra time at recess, a chance to be first in the lunch line, a special snack, a certificate you create, or the chance to bring a special book home). If possible, arrange for another teacher or an administrator to come into your class at the end of the game to act as a judge. For Session 3, assign partners and pick a second prize for the group that wins the game. |

| 2. | Make one copy of the sheet for each group and pair of students. (You will use this sheet to record your observations while students are working during Session 1 and presenting during Session 4.) Make one copy of the , , and the for each student. Make enough copies of the sheet so that every student has a checklist for each set of partners that presents (see Session 4). |

| 3. | Make a two-column chart for Session 1. Write at the top of the chart. Write at the top of one column and at the top of the other. |

| 4. | If you do not have classroom computers with Internet access, arrange to spend one session in your school’s computer lab (see Session 3). Bookmark the on your classroom or lab computers, and make sure that it is working properly. |

| 5. | Preview the and bookmark it on your classroom computer. You will be sharing this with students during Session 2 and may want to arrange to use an LCD projector or a computer with a large screen. |

Student Objectives

Students will

- Work in cooperative groups to brainstorm ideas and organize them into a cohesive argument to be presented to the class

- Gain knowledge of the different strategies that are used in effective persuasive writing

- Use a graphic organizer to help them begin organizing their ideas into written form

- Apply what they have learned to write a persuasive piece that expresses their stance and reasoning in a clear, logical sequence

- Develop oral presentation skills by presenting their persuasive writing pieces to the class

- Analyze the work of others to see if it contains effective persuasive techniques

Session 1: The Game of Persuasion

| 1. | Post the chart you created where students can see it (see Preparation, Step 3). Distribute sticky notes, and ask students to write their names on the notes. Call students up to the chart to place their notes in the column that expresses their opinion. |

| 2. | After everyone has had a chance to put their name on the chart, look at the results and discuss how people have different views about various topics and are entitled to their opinions. Give students a chance to share the reasons behind their choices. |

| 3. | Once students have shared, explain that sometimes when you believe in something, you want others to believe in it also and you might try to get them to change their minds. Ask students the following question: “Does anyone know the word for trying to convince someone to change his or her mind about something?” Elicit from students the word . |

| 4. | Explain to students that they are going to play a game that will help them understand how persuasive arguments work. |

| 5. | Follow these rules of the game: While students are working, there should be little interference from you. This is a time for students to discover what they already know about persuasive arguments. Use the handout as you listen in to groups and make notes about their arguments. This will help you see what students know and also provide examples to point out during Session 2 (see Step 4). |

Home/School Connection: Distribute Persuasion Is All Around You . Students are to find an example of a persuasive piece from the newspaper, television, radio, magazine, or billboards around town and be ready to report back to class during Session 2. Provide a selection of magazines or newspapers with advertisements for students who may not have materials at home. For English-language learners (ELLs), it may be helpful to show examples of advertisements and articles in newspapers and magazines.

Session 2: Analysis of an Argument

| 1. | Begin by asking students to share their homework. You can have them share as a class, in their groups from the previous session, or in partners. |

| 2. | After students have shared, explain that they are going to get a chance to examine the arguments that they made during Session 1 to find out what strategies they already know how to use. |

| 3. | Pass out the to each student. Tell students that you are going to explain each definition through a PowerPoint presentation. |

| 4. | Read through each slide in the . Discuss the meaning and how students used those strategies in their arguments during Session 1. Use your observations and notes to help students make connections between their arguments and the persuasive strategies. It is likely your students used many of the strategies, and did not know it. For example, imagine the reward for the winning team was 10 extra minutes of recess. Here is one possible argument: “Our classmate Sarah finally got her cast taken off. She hasn’t been able to play outside for two months. For 60 days she’s had to go sit in the nurse’s office while we all played outside. Don’t you think it would be the greatest feeling for Sarah to have 10 extra minutes of recess the first week of getting her cast off?” This group is trying to appeal to the other students’ emotions. This is an example of . |

| 5. | As you discuss the examples from the previous session, have students write them in the box next to each definition on the Persuasive Strategy Definitions sheet to help them remember each meaning. |

Home/School Connection: Ask students to revisit their persuasive piece from Persuasion Is All Around You . This time they will use Check the Strategies to look for the persuasive strategies that the creator of the piece incorporated. Check for understanding with your ELLs and any special needs students. It may be helpful for them to talk through their persuasive piece with you or a peer before taking it home for homework. Arrange a time for any student who may not have the opportunity to complete assignments outside of school to work with you, a volunteer, or another adult at school on the assignment.

Session 3: Persuasive Writing

| 1. | Divide the class into groups of two or three students. Have each group member talk about the persuasive strategies they found in their piece. |

| 2. | After each group has had time to share with each other, go through each persuasive strategy and ask students to share any examples they found in their persuasive pieces with the whole class. |

| 3. | Explain to students that in this session they will be playing the game they played during Session 1 again; only this time they will be working with a partner to write their argument and there will be a different prize awarded to the winning team. |

| 4. | Share the with students and read through each category. Explain that you will be using this rubric to help evaluate their essays. Reassure students that if they have questions or if part of the rubric is unclear, you will help them during their conference. |

| 5. | Have students get together with the partners you have selected (see Preparation, Step 1). |

| 6. | Get students started on their persuasive writing by introducing them to the interactive . This online graphic organizer is a prewriting exercise that enables students to map out their arguments for a persuasive essay. or stance that they are taking on the issue. Challenge students to use the persuasive strategies discussed during Session 2 in their writing. Remind students to print their maps before exiting as they cannot save their work online. |

| 7. | Have students begin writing their persuasive essays, using their printed Persuasion Maps as a guide. To maintain the spirit of the game, allow students to write their essays with their partner. Partners can either write each paragraph together taking turns being the scribe or each can take responsibility for different paragraphs in the essay. If partners decide to work on different parts of the essay, monitor them closely and help them to write transition sentences from one paragraph to the next. It may take students two sessions to complete their writing. |

| 8. | Meet with partners as they are working on their essays. During conferences you can: |

Session 4: Presenting the Persuasive Writing

| 1. | During this session, partners will present their written argument to the class. Before students present, hand out the sheet. This checklist is the same one they used for homework after Session 2. Direct students to mark off the strategies they hear in each presentation. |

| 2. | Use the sheet to record your observations. |

| 3. | After each set of partners presents, ask the audience to share any persuasive strategies they heard in the argument. |

| 4. | After all partners have presented, have students vote for the argument other than their own that they felt was most convincing. |

| 5. | Tally the votes and award the prize to the winning team. To end this session, ask students to discuss something new they have learned about persuasive arguments and something they want to work on to become better at persuasive arguments. |

- Endangered Species: Persuasive Writing offers a way to integrate science with persuasive writing. Have students pretend that they are reporters and have to convince people to think the way they do. Have them pick issues related to endangered species, use the Persuasion Map as a prewriting exercise, and write essays trying to convince others of their points of view. In addition, the lesson “Persuasive Essay: Environmental Issues” can be adapted for your students as part of this exercise.

- Have students write persuasive arguments for a special class event, such as an educational field trip or an in-class educational movie. Reward the class by arranging for the class event suggested in one of the essays.

Student Assessment / Reflections

- Compare your Observations and Notes from Session 4 and Session 1 to see if students understand the persuasive strategies, use any new persuasive strategies, seem to be overusing a strategy, or need more practice refining the use of a strategy. Offer them guidance and practice as needed.

- Collect both homework assignments and the Check the Strategy sheets and assess how well students understand the different elements of persuasive writing and how they are applied.

- Collect students’ Persuasion Maps and use them and your discussions during conferences to see how well students understand how to use the persuasive strategies and are able to plan their essays. You want to look also at how well they are able to make changes from the map to their finished essays.

- Use the Persuasive Writing Assessment to evaluate the essays students wrote during Session 3.

- Calendar Activities

- Strategy Guides

- Lesson Plans

- Student Interactives

The Persuasion Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to map out their arguments for a persuasive essay or debate.

This interactive tool allows students to create Venn diagrams that contain two or three overlapping circles, enabling them to organize their information logically.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

No doubt, teaching argument writing to middle school students can be tricky. Even the word “argumentative” is off-putting, bringing to mind pointless bickering. But once I came up with argument writing lessons that were both fun and effective, I quickly saw the value in it. And so did my students.

You see, we teachers have an ace up our sleeve. It’s a known fact that from ages 11-14, kids love nothing more than to fire up a good ole battle royale with just about anybody within spitting distance.

Yup. So we’re going to use their powers of contradiction to OUR advantage by showing them how to use our argument writing lessons to power up their real-life persuasion skills. Your students will be knocking each other over in the hall to get to the room first!

I usually plan on taking about three weeks on the entire argument writing workshop. However, there are years when I’ve had to cut it down to two, and that works fine too.

Here are the step-by-step lessons I use to teach argument writing. It might be helpful to teachers who are new to teaching the argument, or to teachers who want to get back to the basics. If it seems formulaic, that’s because it is. In my experience, that’s the best way to get middle school students started.

Prior to Starting the Writer’s Workshop

A couple of weeks prior to starting your unit, assign some quick-write journal topics. I pick one current event topic a day, and I ask students to express their opinion about the topic.

Quick-writes get the kids thinking about what is going on in the world and makes choosing a topic easier later on.

Define Argumentative Writing

I’ll never forget the feeling of panic I had in 7th grade when my teacher told us to start writing an expository essay on snowstorms. How could I write an expository essay if I don’t even know what expository MEANS, I whined to my middle school self.

We can’t assume our students know or remember what argumentative writing is, even if we think they should know. So we have to tell them. Also, define claim and issue while you’re at it.

Establish Purpose

I always tell my students that learning to write an effective argument is key to learning critical thinking skills and is an important part of school AND real-life writing.

We start with a fictional scenario every kid in the history of kids can relate to.

ISSUE : a kid wants to stay up late to go to a party vs. AUDIENCE : the strict mom who likes to say no.

The “party” kid writes his mom a letter that starts with a thesis and a claim: I should be permitted to stay out late to attend the part for several reasons.

By going through this totally relatable scenario using a modified argumentative framework, I’m able to demonstrate the difference between persuasion and argument, the importance of data and factual evidence, and the value of a counterclaim and rebuttal.

Students love to debate whether or not strict mom should allow party kid to attend the party. More importantly, it’s a great way to introduce the art of the argument, because kids can see how they can use the skills to their personal advantage.

Persuasive Writing Differs From Argument Writing

At the middle school level, students need to understand persuasive and argument writing in a concrete way. Therefore, I keep it simple by explaining that both types of writing involve a claim. However, in persuasive writing, the supporting details are based on opinions, feelings, and emotions, while in argument writing the supporting details are based on researching factual evidence.

I give kids a few examples to see if they can tell the difference between argumentation and persuasion before we move on.

Argumentative Essay Terminology

In order to write a complete argumentative essay, students need to be familiar with some key terminology . Some teachers name the parts differently, so I try to give them more than one word if necessary:

- thesis statement

- bridge/warrant

- counterclaim/counterargument*

- turn-back/refutation

*If you follow Common Core Standards, the counterargument is not required for 6th-grade argument writing. All of the teachers in my school teach it anyway, and I’m thankful for that when the kids get to 7th grade.

Organizing the Argumentative Essay

I teach students how to write a step-by-step 5 paragraph argumentative essay consisting of the following:

- Introduction : Includes a lead/hook, background information about the topic, and a thesis statement that includes the claim.

- Body Paragraph #1 : Introduces the first reason that the claim is valid. Supports that reason with facts, examples, and/or data.

- Body Paragraph #2 : The second reason the claim is valid. Supporting evidence as above.

- Counterargument (Body Paragraph #3): Introduction of an opposing claim, then includes a turn-back to take the reader back to the original claim.

- Conclusion : Restates the thesis statement, summarizes the main idea, and contains a strong concluding statement that might be a call to action.

Mentor Texts

If we want students to write a certain way, we should provide high-quality mentor texts that are exact models of what we expect them to write.

I know a lot of teachers will use picture books or editorials that present arguments for this, and I can get behind that. But only if specific exemplary essays are also used, and this is why.

If I want to learn Italian cooking, I’m not going to just watch the Romanos enjoy a holiday feast on Everybody Loves Raymond . I need to slow it down and follow every little step my girl Lidia Bastianich makes.

The same goes for teaching argument writing. If we want students to write 5 paragraph essays, that’s what we should show them.

In fact, don’t just display those mentor texts like a museum piece. Dissect the heck out of those essays. Pull them apart like a Thanksgiving turkey. Disassemble the essay sentence by sentence and have the kids label the parts and reassemble them. This is how they will learn how to structure their own writing.

Also, encourage your detectives to evaluate the evidence. Ask students to make note of how the authors use anecdotes, statistics, and facts. Have them evaluate the evidence and whether or not the writer fully analyzes it and connects it to the claim.