The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 3: Presenting Qualitative Data

- Presenting qualitative data

- Data visualization

- Research paper writing

- Introduction

What is rigor in qualitative research?

Why is transparent research important, how do you achieve transparency and rigor in research.

- How to publish a research paper

Transparency and rigor in research

Qualitative researchers face particular challenges in convincing their target audience of the value and credibility of their subsequent analysis . Numbers and quantifiable concepts in quantitative studies are relatively easier to understand than their counterparts associated with qualitative methods . Think about how easy it is to make conclusions about the value of items at a store based on their prices, then imagine trying to compare those items based on their design, function, and effectiveness.

The goal of qualitative data analysis is to allow a qualitative researcher and their audience to make determinations about the value and impact of the research. Still, before the audience can reach these determinations, the process of conducting research that produces the qualitative analysis must first be perceived as credible. It is the responsibility of the researcher to persuade their audience that their data collection process and subsequent analysis are rigorous.

Qualitative rigor refers to the meticulousness, consistency, and transparency of the research. It is the application of systematic, disciplined, and stringent methods to ensure the credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability of research findings. In qualitative inquiry, these attributes ensure the research accurately reflects the phenomenon it is intended to represent, that its findings can be used by others, and that its processes and results are open to scrutiny and validation.

Credibility

Credibility refers to the extent to which the results accurately represent the participants' experiences. To achieve credibility, qualitative researchers, especially those conducting research on human research participants, employ a number of strategies to bolster the credibility of the data and the subsequent analysis. Prolonged engagement and persistent observation , for example, involve spending significant time in the field to gain a deep understanding of the research context and to continuously observe the phenomenon under study. Peer debriefing involves discussing the research and findings with knowledgeable peers to assess their validity . Member checking involves sharing the findings with the research participants to confirm that they accurately reflect their experiences. These and other methods ensure an abundantly rich data set from which the researcher describes in vivid detail the phenomenon under study, and which other scholars can audit to challenge the strength of the findings if necessary.

Dependability

Dependability refers to the consistency of the research process such that it is logical and clearly documented. It addresses the potential for others to build on the research through subsequent studies. To achieve dependability, researchers should provide a 'decision trail' detailing all decisions made during the course of the study. This allows others to understand how conclusions were reached and to replicate the study if necessary. Ultimately, the documentation of a researcher's process while collecting and analyzing data provides a clear record not only for other scholars to consider but also for those conducting the study and refining their methods for future research.

Confirmability

Confirmability requires the research findings to be directly linked to the data. While it is important to acknowledge researcher positionality (e.g., through reflexive memos) in social science research, researchers still have a responsibility to make assertions and identify insights rooted in the data for the resulting knowledge to be considered confirmable. By transparently communicating how the data was analyzed and conclusions were reached, researchers can allow their audience to perform a sort of audit of the study. This practice helps remind researchers about the importance of ensuring that there are sufficient connections to the raw data collected from the field and the findings that are presented as consequential developments of theory.

Transferability

Transferability refers to the applicability of the research findings in other contexts or with other participants. While dependability is more relevant to the application of research within its own situated context, transferability is determined by how findings generated in one set of circumstances (e.g., a geographic location or a culture) apply to another set of circumstances. This is essentially a significant challenge since, given the unique focus on context in qualitative research , researchers can't usually claim that their findings are universally applicable. Instead, they provide a rich, detailed description of the context and participants, enabling others to determine if the findings may apply to their own context. As a result, such detail necessitates discussion of transparency in research, which will be discussed later in this section.

Reflexivity

The concept of reflexivity also contributes to rigor in qualitative research. Reflexivity involves the researcher critically reflecting on the research and their own role in it, including how their biases , values, experiences, and presence may influence the research. Any discussion of reflexivity necessitates a recognition that knowledge about the social world is never objective, but always from a particular perspective. Reflexivity begins with an acknowledgment that those who conduct qualitative research do so while perceiving the social world through an analytical lens that is unique and distinct from that of others. As subjectivity is an inevitable circumstance in any research involving humans as sources or instruments of data collection , the researcher is responsible for providing a thick description of the environment in which they are collecting data as well as a detailed description of their own place in the research. Subjectivity can be considered as an asset, whereby researchers acknowledge and indicate how their positionality informed the analysis in ways that were insightful and productive.

Triangulation

Triangulation is another key aspect of rigor, referring to the use of multiple data sources, researchers, or methods to cross-check and validate findings. This can increase the depth and breadth of the research, improve its quality, and decrease the likelihood of researcher bias influencing the findings. Particularly given the complexity and dynamic nature of the social world, one method or one analytical approach will seldom be sufficient in holistically understanding the phenomenon or concept under study. Instead, a researcher benefits from examining the world through multiple methods and multiple analytical approaches, not to garner perfectly consistent results but to gather as much rich detail as possible to strengthen the analysis and subsequent findings.

In qualitative research , rigor is not about seeking a single truth or reality, but rather about being thorough, transparent, and critical in the research to ensure the integrity and value of the study. Rigor can be seen as a commitment to best practices in research, with researchers consistently questioning their methods and findings, checking for alternative interpretations , and remaining open to critique and revision. This commitment to rigor helps ensure that qualitative research provides valid, reliable , and meaningful contributions to our understanding of the complex social world.

Transparently document your research with ATLAS.ti

Choose ATLAS.ti for getting the most out of your data. Download a free trial of our software today.

When you read a story in a newspaper or watch a news report on television, do you ever get the feeling that you may not be receiving all the information or context necessary to understand the overarching messages being conveyed? Perhaps a salesperson is trying to convince you to buy something from them by explaining all the benefits of a product but doesn't tell you how they know these benefits are real. When you're choosing a movie to watch, you might look at a critic's review or a score in an online movie database without actually knowing how that review or score was actually determined.

In all of these situations, it is easier to trust the information presented to you if there is a rigorous analysis process behind that information and if that process is explicitly detailed. The same is true for qualitative research results, making transparency a key element in qualitative research methodologies . Transparency is a fundamental aspect of rigor in qualitative research. It involves the clear, detailed, and explicit documentation of all stages of the research process. This allows other researchers to understand, evaluate, transfer, and build upon the study. The key aspects of transparency in qualitative research include methodological transparency, analytical transparency, and reflexive transparency.

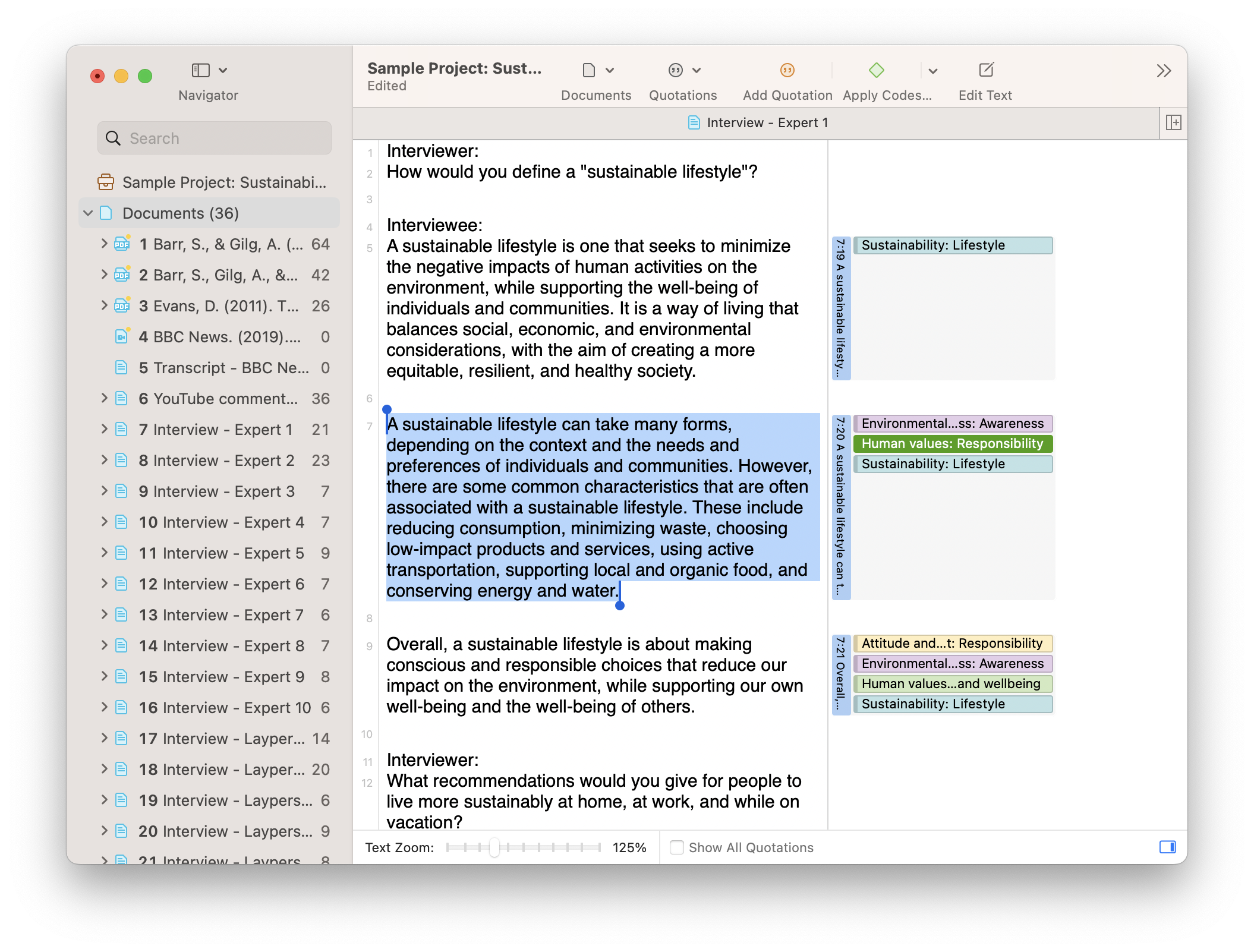

Methodological transparency involves providing a comprehensive description of the research methods and procedures used in the study. This includes detailing the research design, sampling strategy, data collection methods , and ethical considerations . For example, researchers should thoroughly describe how participants were selected, how and where data were collected (e.g., interviews , focus groups , observations ), and how ethical issues such as consent, confidentiality , and potential harm were addressed. They should also clearly articulate the theoretical and conceptual frameworks that guided the study. Methodological transparency allows other researchers to understand how the study was conducted and assess its trustworthiness.

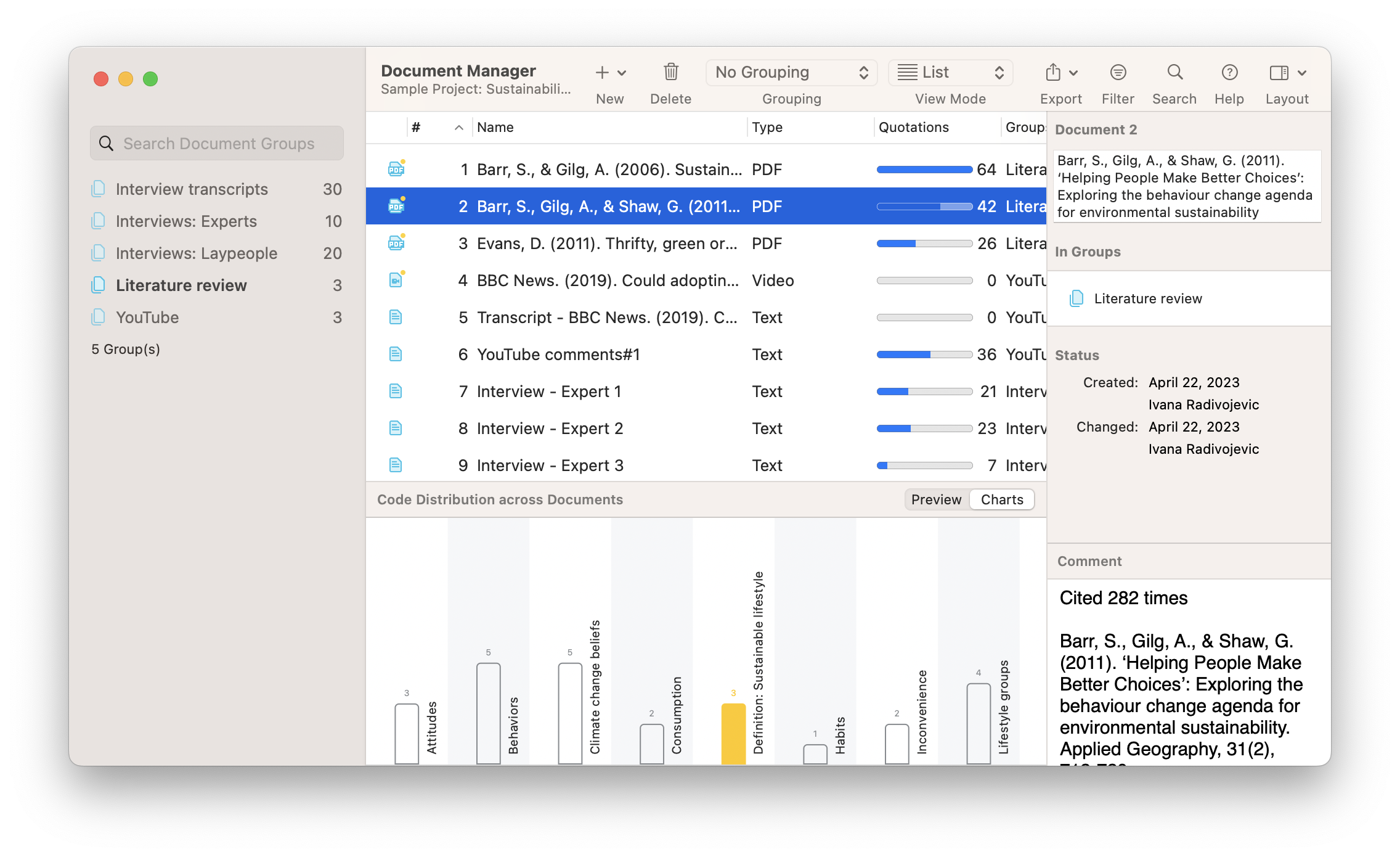

Analytical transparency refers to the clear and detailed documentation of the data analysis process. This involves explaining how the raw data were transformed into findings, including the coding process , theme/category development, and interpretation of results . Researchers should describe the specific analytical strategies they used, such as thematic analysis , grounded theory , or discourse analysis . They should provide evidence to support their findings, such as direct quotes from participants. They may also describe any software they used to assist with analyzing data . Analytical transparency allows other researchers to understand how the findings were derived and assess their credibility and confirmability.

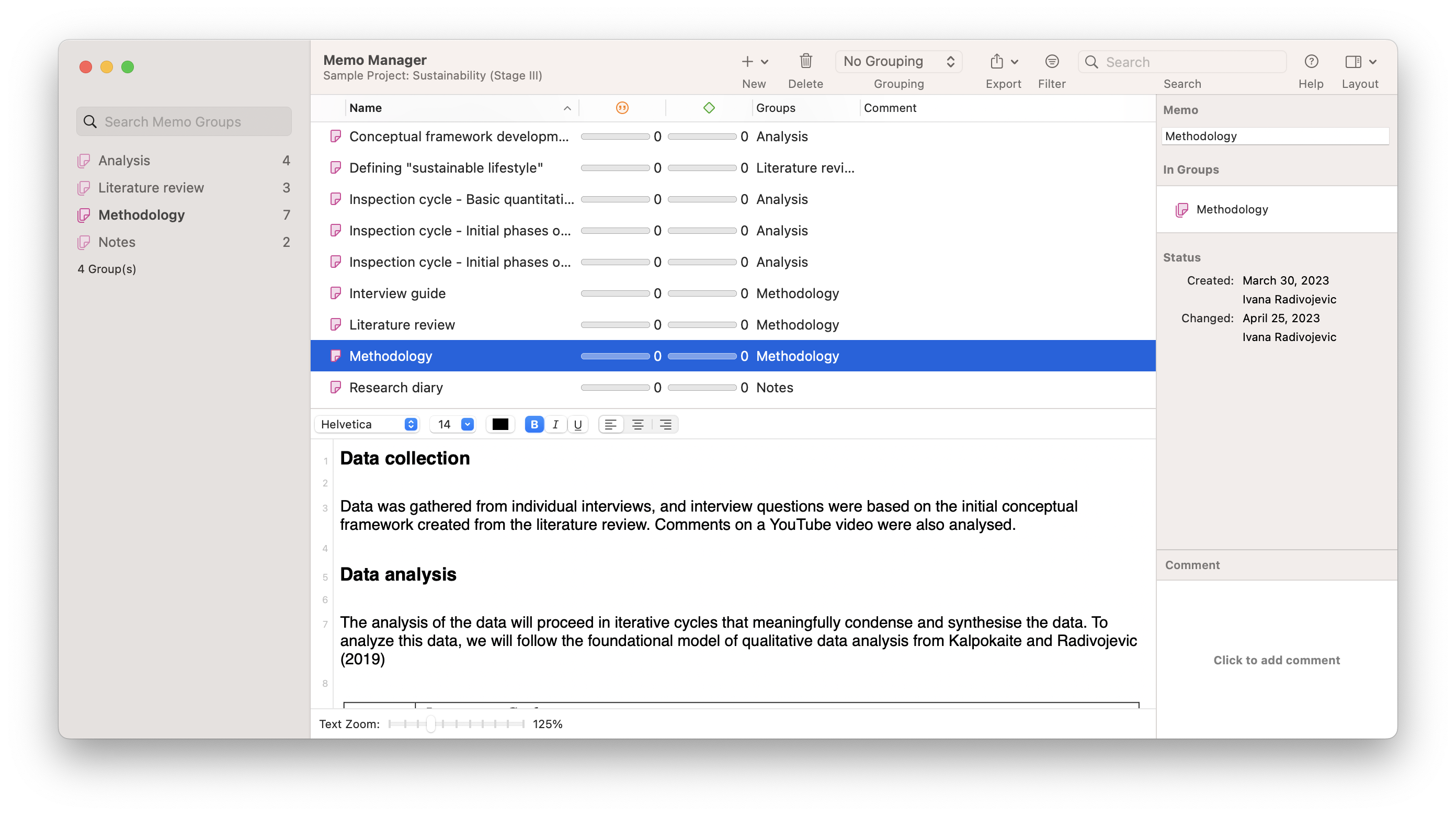

Reflexive transparency involves the researcher reflecting on and disclosing their own role in the research, including their potential biases , assumptions, and influences. This includes recognizing and discussing how the researcher's background, beliefs, and interactions with participants may have shaped the data collection and analysis . Reflexive transparency may be achieved through the use of a reflexivity journal, where the researcher regularly records their thoughts, feelings, and reactions during research. This aspect of transparency ensures that the researcher is open about their subjectivity and allows others to assess the potential impact of the researcher's positionality on the findings.

Transparency in qualitative research is essential for maintaining rigor, trustworthiness, and ethical integrity . By being transparent, researchers allow their work to be scrutinized, critiqued, and improved upon, contributing to the ongoing development and refinement of knowledge in their field.

Rigorous, trustworthy research is research that applies the appropriate research tools to meet the stated objectives of the investigation. For example, to determine if an exploratory investigation was rigorous, the investigator would need to answer a series of methodological questions: Do the data collection tools produce appropriate information for the level of precision required in the analysis ? Do the tools maximize the chance of identifying the full range of what there is to know about the phenomenon? To what degree are the collection techniques likely to generate the appropriate level of detail needed for addressing the research question(s) ? To what degree do the tools maximize the chance of producing data with discernible patterns?

Once the data are collected, to what degree are the analytic techniques likely to ensure the discovery of the full range of relevant and salient themes and topics? To what degree do the analytic strategies maximize the potential for finding relationships among themes and topics? What checks are in place to ensure that the discovery of patterns and models are relevant to the research question? Finally, what standards of evidence are required to ensure readers that results are supported by the data?

The clear challenge is to identify what questions are most important for establishing research rigor (trustworthiness) and to provide examples of how such questions could be answered for those using qualitative data . Clearly, rigorous research must be both transparent and explicit; in other words, researchers need to be able to describe to their colleagues and their audiences what they did (or plan to do) in clear, simple language. Much of the confusion that surrounds qualitative data collection and analysis techniques comes from practitioners who shroud their behaviors in mystery and jargon. For example, clearly describing how themes are identified, how codebooks are built and applied, and how models were induced helps to bring more rigor to qualitative research .

Researchers also must become more familiar with the broad range of methodological techniques available, such as content analysis , grounded theory , and discourse analysis . Cross-fertilization across methodological traditions can also be extremely valuable to generate meaningful understanding rather than attacking all problems with the same type of methodological tool.

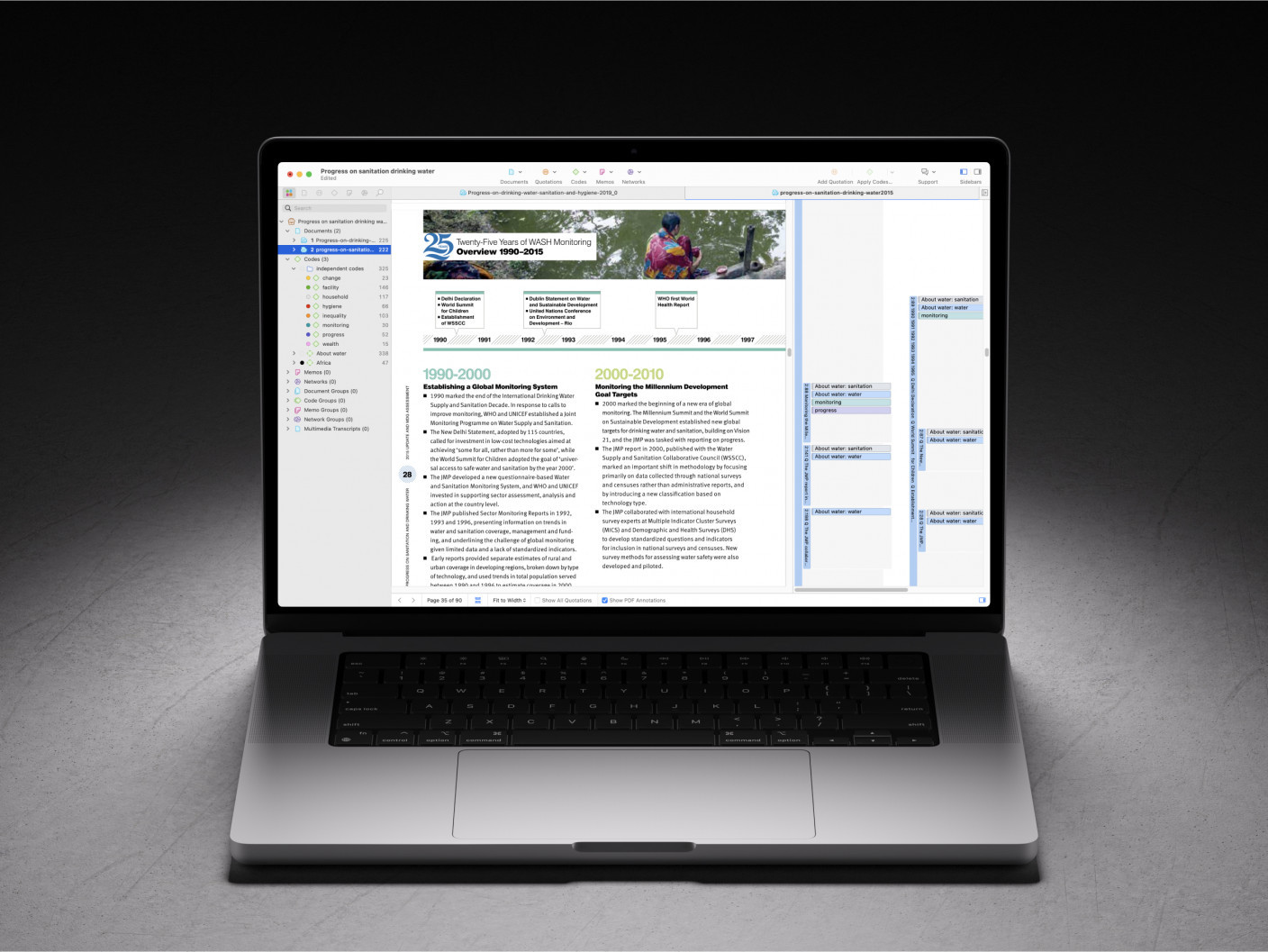

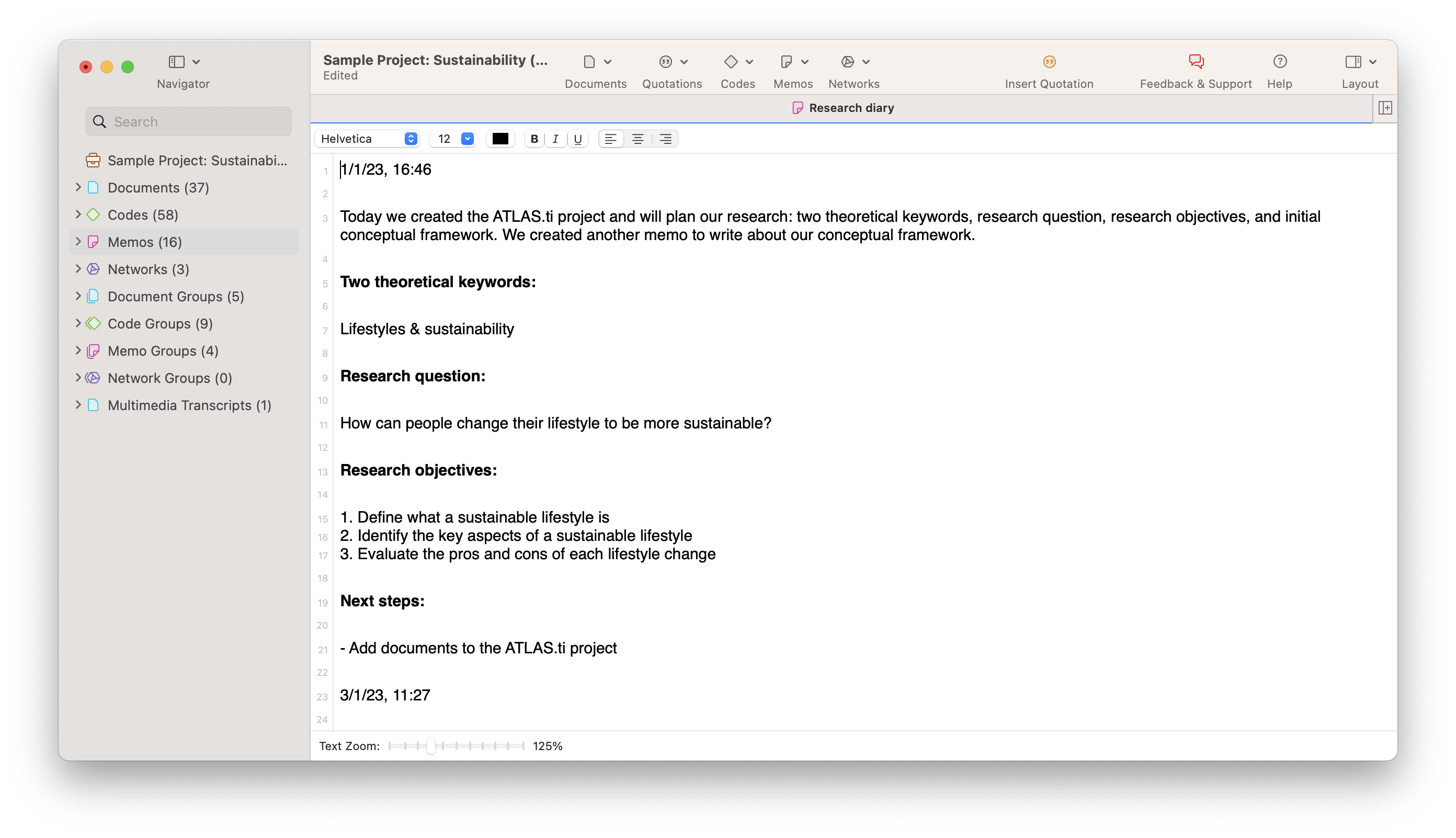

The introduction of methodologically neutral and highly flexible qualitative analysis software like ATLAS.ti can be considered as extremely helpful indeed. It is highly apt to both support interdisciplinary cross-pollination and to bring about a great deal of trust in the presented results. By allowing the researcher to combine both the source material and his/her findings in a structured, interactive platform while producing both quantifiable reports and intuitive visual renderings of their results, ATLAS.ti adds new levels of trustworthiness to qualitative research . Moreover, it permits the researcher to apply multiple approaches to their research, to collaborate across philosophical boundaries, and thus significantly enhance the level of rigor in qualitative research. Dedicated research software like ATLAS.ti helps the researcher to catalog, explore and competently analyze the data generated in a given research project.

Ultimately, transparency and rigor are indispensable elements of any robust research study. Achieving transparency requires a systematic, deliberate, and thoughtful approach. It revolves around clarity in the formulation of research objectives, comprehensiveness in methods, and conscientious reporting of the results. Here are several key strategies for achieving transparency and rigor in research:

Clear research objectives and methods

Transparency begins with the clear and explicit statement of research objectives and questions. Researchers should explain why they are conducting the study, what they hope to learn, and how they plan to achieve their objectives. This involves identifying and articulating the study's theoretical or conceptual framework and delineating the key research questions . Ensuring clarity at this stage sets the groundwork for transparency throughout the rest of the study.

Transparent research includes a comprehensive and detailed account of the research design and methodology. Researchers should describe all stages of their research process, including the selection and recruitment of participants, the data collection methods , the setting of the research, and the timeline. Each step should be explained in enough detail that another researcher could replicate the study. Furthermore, any modifications to the research design or methodology over the course of the study should be clearly documented and justified.

Thorough data documentation and analysis

In the data collection phase, researchers should provide thorough documentation, including original data records such as transcripts , field notes , or images . The specifics of how data was gathered, who was involved, and when and where it took place should be meticulously recorded.

During the data analysis phase , researchers should clearly describe the steps taken to analyze the data, including coding processes , theme identification , and how conclusions were drawn. Researchers should provide evidence to support their findings and interpretations , such as verbatim quotes or detailed examples from the data. They should also describe any analytic software or tools used, including how they were used and why they were chosen.

Reflexivity and acknowledgment of bias

Transparent research involves a process of reflexivity , where researchers critically reflect on their own role in the research process. This includes considering how their own beliefs, values, experiences, and relationships with participants may have influenced the data collection and analysis . Researchers should maintain reflexivity journals to document these reflections, which can then be incorporated into the final research report. Researchers should also explicitly acknowledge potential biases and conflicts of interest that could influence the research. This includes personal, financial, or institutional interests that could affect the conduct or reporting of the research.

Transparent reporting and publishing

Transparency also involves the open sharing of research materials and data, where ethical and legal guidelines permit. This may include providing access to interview guides , survey instruments , data analysis scripts, raw data , and other research materials. Open sharing allows others to scrutinize, transfer, or extend the research, thereby enhancing its transparency and trustworthiness.

Finally, the reporting and publishing phase should adhere to the principles of transparency. Researchers should follow the relevant reporting guidelines for their field. Such guidelines provide a framework for reporting research in a comprehensive, systematic, and transparent manner.

Furthermore, researchers should choose to publish in open-access journals or other accessible formats whenever possible, to ensure the research is publicly accessible. They should also be open to critique and engage in post-publication discussion and debate about their findings.

By adhering to these strategies, researchers can ensure the transparency of their research, enhancing its credibility, trustworthiness, and contribution to their field. Transparency is more than just a good research practice—it's a fundamental ethical obligation to the research community, participants, and wider society.

Rigorous research starts with ATLAS.ti

Click here for a free trial of our powerful and intuitive data analysis software.

MS in Nursing (MSN)

A Guide To Qualitative Rigor In Research

Advances in technology have made quantitative data more accessible than ever before; but in the human-centric discipline of nursing, qualitative research still brings vital learnings to the health care industry. It is sometimes difficult to derive viable insights from qualitative research; but in the article below, the authors identify three criteria for developing acceptable qualitative studies.

Qualitative rigor in research explained

Qualitative rigor. It’s one of those terms you either understand or you don’t. And it seems that many of us fall into the latter of those two categories. From novices to experienced qualitative researchers, qualitative rigor is a concept that can be challenging. However, it also happens to be one of the most critical aspects of qualitative research, so it’s important that we all start getting to grips with what it means.

Rigor, in qualitative terms, is a way to establish trust or confidence in the findings of a research study. It allows the researcher to establish consistency in the methods used over time. It also provides an accurate representation of the population studied. As a nurse, you want to build your practice on the best evidence you can and to do so you need to have confidence in those research findings.

This article will look in more detail at the unique components of qualitative research in relation to qualitative rigor. These are: truth-value (credibility); applicability (transferability); consistency (dependability); and neutrality (confirmability).

Credibility

Credibility allows others to recognize the experiences contained within the study through the interpretation of participants’ experiences. In order to establish credibility, a researcher must review the individual transcripts, looking for similarities within and across all participants.

A study is considered credible when it presents an interpretation of an experience in such a way that people sharing that experience immediately recognize it. Examples of strategies used to establish credibility include:

- Reflexivity

- Member checking (aka informant feedback)

- Peer examination

- Peer debriefing

- Prolonged time spent with participants

- Using the participants’ words in the final report

Transferability

The ability to transfer research findings or methods from one group to another is called transferability in qualitative language, equivalent to external validity. One way of establishing transferability is to provide a dense description of the population studied by describing the demographics and geographic boundaries of the study.

Ways in which transferability can be applied by researchers include:

- Using the same data collection methods with different demographic groups or geographical locations

- Giving a range of experiences on which the reader can build interventions and understanding to decide whether the research is applicable to practice

Dependability

Related to reliability in quantitative terms, dependability occurs when another researcher can follow the decision trail used by the researcher. This trail is achieved by:

- Describing the specific purpose of the study

- Discussing how and why the participants were selected for the study

- Describing how the data was collected and how long collection lasted

- Explaining how the data was reduced or transformed for analysis

- Discussing the interpretation and presentation of the findings

- Explaining the techniques used to determine the credibility of the data

Strategies used to establish dependability include:

- Having peers participate in the analysis process

- Providing a detailed description of the research methods

- Conducting a step-by-step repetition of the study to identify similarities in results or to enhance findings

Confirmability

Confirmability occurs once credibility, transferability and dependability have been established. Qualitative research must be reflective, maintaining a sense of awareness and openness to the study and results. The researcher needs a self-critical attitude, taking into account how his or her preconceptions affect the research.

Techniques researchers use to achieve confirmability include:

- Taking notes regarding personal feelings, biases and insights immediately after an interview

- Following, rather than leading, the direction of interviews by asking for clarifications when needed

Reflective research produces new insights, which lead the reader to trust the credibility of the findings and applicability of the study

Become a Champion of Qualitative Rigor

Clinical Nurse Leaders, or CNLs, work with interdisciplinary teams to improve care for populations of patients. CNLs can impact quality and safety by assessing risks and utilizing research findings to develop quality improvement strategies and evidence-based solutions.

As a student in Queens University of Charlotte’s online Master of Science in Nursing program , you will solidify your skills in research and analysis allowing you to make informed, strategic decisions to drive measurable results for your patients.

Request more information to learn more about how this degree can improve your nursing practice, or call 866-313-2356.

Adapted from: Thomas, E. and Magilvy, J. K. (2011), Qualitative Rigor or Research Validity in Qualitative Research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 16: 151–155. [WWW document]. URL http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00283.x [accessed 2 July 2014]

Recommended Articles

Tips for nurse leaders to maintain moral courage amid ethical dilemmas, relationship between nursing leadership & patient outcomes, day in the life of a clinical nurse leader®, 8 leadership skills nurses need to be successful, the rise of medical errors in hospitals, get started.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 26: Rigour

Darshini Ayton

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the concepts of rigour and trustworthiness in qualitative research.

- Describe strategies for dependability, credibility, confirmability and transferability in qualitative research.

- Define reflexivity and describe types of reflexivity

What is rigour?

In qualitative research, rigour, or trustworthiness, refers to how researchers demonstrate the quality of their research. 1, 2 Rigour is an umbrella term for several strategies and approaches that recognise the influence on qualitative research by multiple realities; for example, of the researcher during data collection and analysis, and of the participant. The research process is shaped by multiple elements, including research skills, the social and research environment and the community setting. 2

Research is considered rigorous or trustworthy when members of the research community are confident in the study’s methods, the data and its interpretation. 3 As mentioned in Chapters 1 and 2, quantitative and qualitative research are founded on different research paradigms and, hence, quality in research cannot be addressed in the same way for both types of research studies. Table 26.1 provides a comparison overview of the approaches of quantitative and qualitative research in ensuring quality in research.

Table 26.1: Comparison of quantitative and qualitative approaches to ensuring quality in research

Below is an overview of the main approaches to rigour in qualitative research. For each of the approaches, examples of how rigour was demonstrated are provided from the author’s PhD thesis.

Approaches to dependability

Dependability requires the researcher to provide an account of changes to the research process and setting. 3 The main approach to dependability is an audit trail.

- Audit trail – the researcher records or takes notes on the conduct of the research and the process of reaching conclusions from the data. The audit trail includes information on the data collection and data analysis, including decision-making and interpretations of the data that influence the study’s results. 8 , 9

The interview questions for this study evolved as the study progressed, and accordingly, the process was iterative. I spent 12 months collecting data, and as my understanding and responsiveness to my participants and to the culture and ethos of the various churches developed, so did my line of questioning. For example, in the early interviews for phase 2, I included questions regarding the qualifications a church leader might look for in hiring someone to undertake health promotion activities. This question was dropped after the first couple of interviews, as it was clear that church leaders did not necessarily view their activities as health promoting and therefore did not perceive the relevance of this question. By ‘being church’, they were health promoting, and therefore activities that were health promoting were not easily separated from other activities that were part of the core mission of the church 10 ( pp93–4)

Approaches to credibility

Credibility requires the researcher to demonstrate the truth or confidence in the findings. The main approaches to credibility include triangulation, prolonged engagement, persistent observation, negative case analysis and member checking. 3

- Triangulation – the assembly of data and interpretations from multiple methods (methods triangulation), researchers (research triangulation), theory (theory triangulation) and data sources (different participant groups). 9 Refer to Chapter 28 for a detailed discussion of this process.

- Prolonged engagement – the requirement for researchers to spend sufficient time with participants and/or within the research context to familiarise them with the research setting, to build trust and rapport with participants and to recognise and correct any misinformation. 9

Prolonged engagement with churches was also achieved through the case study phase as the ten case study churches were involved in more than one phase of data collection. These ten churches were the case studies in which significant time was spent conducting interviews and focus groups, and attending activities and programs. Subsequently, there were many instances where I interacted with the same people on more than one occasion, thereby facilitating the development of interactive and deeper relationships with participants 10 (pp.94–5)

- Persistent observation – the identification of characteristics and elements that are most relevant to the problem or issue under study, and upon which the research will focus in detail. 9

In the following chapters, I present my analysis of the world of churches in which I was immersed as I conducted fieldwork. I describe the processes of church practice and action, and explore how this can be conceptualised into health promotion action 10 (p97)

- Negative case analysis – the process of finding and discussing data that contradicts the study’s main findings. Negative case analysis demonstrates that nuance and granularity in perspectives of both shared and divergent opinions have been examined, enhancing the quality of the interpretation of the data.

Although I did not use negative case selection, the Catholic churches in this study acted as examples of the ‘low engagement’ 10 (p97 )

- Member checking – the presentation of data analysis, interpretations and conclusions of the research to members of the participant groups. This enables participants or people with shared identity with the participants to provide their perspectives on the research. 9

Throughout my candidature – during data collection and analysis, and in the construction of my results chapters – I engaged with a number of Christians, both paid church staff members and volunteers, to test my thoughts and concepts. These people were not participants in the study, but they were embedded in the cultural and social context of churches in Victoria. They were able to challenge and also affirm my thinking and so contributed to a process of member checking 10 (p96)

Approaches to confirmability

Confirmability is demonstrated by grounding the results in the data from participants. 3 This can be achieved through the use of quotes, specifying the number of participants and data sources and providing details of the data collection.

- Quotes from participants are used to demonstrate that the themes are generated from the data. The results section of the thesis chapters commences with a story based on the field notes or recordings, with extensive quotes from participants presented throughout. 10

- The number of participants in the study provides the context for where the data is ‘sourced’ from for the results and interpretation. Table 26.2 is reproduced with permission from the Author’s thesis and details the data sources for the project. This also contributes to establishing how triangulation across data sources and methods was achieved.

- Details of data collection – Table 26.2 provides detailed information about the processes of data collection, including dates and locations but the duration of each research encounter was not specified.

Table 26.2 Data sources for the PhD research project of the Author.

Approaches to transferability.

To enable the transferability of qualitative research, researchers need to provide information about the context and the setting. A key approach for transferability is thick description. 6

- Thick description – detailed explanations and descriptions of the research questions are provided, including about the research setting, contextual factors and changes to the research setting. 9

I chose to include the Catholic Church because it is the largest Christian group in Australia and is an example of a traditional church. The Protestant group were represented through the Uniting, Anglican Baptist and Church of Christ denominations. The Uniting Church denomination is unique to Australia and was formed in 1977 through the merging of the Methodist, Presbyterian and Congregationalist denominations. The Church of Christ denomination was chosen to represent a contemporary less hierarchical denomination in comparison to the other protestant denominations. The last group, the Salvation Army, was chosen because of its high profile in social justice and social welfare, therefore offering different perspectives on the role and activities of the church in health promotion 10 (pp82–3)

What is reflexivity?

Reflexivity is the process in which researchers engage to explore and explain how their subjectivity (or bias) has influenced the research. 12 Researchers engage in reflexive practices to ensure and demonstrate rigour, quality and, ultimately, trustworthiness in their research. 13 The researcher is the instrument of data collection and data analysis, and hence awareness of what has influenced their approach and conduct of the research – and being able to articulate them – is vital in the creation of knowledge. One important element is researcher positionality (see Chapter 27), which acknowledges the characteristics, interests, beliefs and personal experiences of the researcher and how this influences the research process. Table 26.3 outlines different types of reflexivity, with examples from the author’s thesis.

Table 26.3: Types of reflexivity

The quality of qualitative research is measured through the rigour or trustworthiness of the research, demonstrated through a range of strategies in the processes of data collection, analysis, reporting and reflexivity.

- Chowdhury IA. Issue of quality in qualitative research: an overview. Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences . 2015;8(1):142-162. doi:10.12959/issn.1855-0541.IIASS-2015-no1-art09

- Cypress BS. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimens Crit Care Nurs . 2017;36(4):253-263. doi:10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253

- Connelly LM. Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nurs . 2016;25(6):435-6.

- Golafshani N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual Rep . 2003;8(4):597-607. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol8/iss4/6/

- Yilmaz K. Comparison of quantitative and qualitative research traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. Eur J Educ . 2013;48(2):311-325. doi:10.1111/ejed.12014

- Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information 2004;22:63-75. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://content.iospress.com/articles/education-for-information/efi00778

- Varpio L, O’Brien B, Rees CE, Monrouxe L, Ajjawi R, Paradis E. The applicability of generalisability and bias to health professions education’s research. Med Educ . Feb 2021;55(2):167-173. doi:10.1111/medu.14348

- Carcary M. The Research Audit Trail: Methodological guidance for application in practice. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods . 2020;18(2):166-177. doi:10.34190/JBRM.18.2.008

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract . Dec 2018;24(1):120-124. doi:10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

- Ayton D. ‘From places of despair to spaces of hope’ – the local church and health promotion in Victoria . PhD. Monash University; 2013. https://figshare.com/articles/thesis/_From_places_of_despair_to_spaces_of_hope_-_the_local_church_and_health_promotion_in_Victoria/4628308/1

- Hanson A. Negative case analysis. In: Matthes J, ed. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods . John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017. doi: 10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0165

- Olmos-Vega FM. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med Teach . 2023;45(3):241-251. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

- Dodgson JE. Reflexivity in qualitative research. J Hum Lact . 2019;35(2):220-222. doi:10.1177/08903344198309

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Darshini Ayton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Qualitative Research:...

Qualitative Research: Rigour and qualitative research

- Related content

- Peer review

- Nicholas Mays , director of health services research a ,

- Catherine Pope , lecturer in social and behavioural medicine b

- a King's Fund Institute, London W2 4HT

- b Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 6TP

- Correspondence to: Mr Mays.

Various strategies are available within qualitative research to protect against bias and enhance the reliability of findings. This paper gives examples of the principal approaches and summarises them into a methodological checklist to help readers of reports of qualitative projects to assess the quality of the research.

Criticisms of qualitative research

In the health field--with its strong tradition of biomedical research using conventional, quantitative, and often experimental methods--qualitative research is often criticised for lacking scientific rigour. To label an approach “unscientific” is peculiarly damning in an era when scientific knowledge is generally regarded as the highest form of knowing. The most commonly heard criticisms are, firstly, that qualitative research is merely an assembly of anecdote and personal impressions, strongly subject to researcher bias; secondly, it is argued that qualiative research lacks reproducibility--the research is so personal to the researcher that there is no guarantee that a different researcher would not come to radically different conclusions; and, finally, qualitative research is criticised for lacking generalisability. It is said that qualitative methods tend to generate large amounts of detailed information about a small number of settings.

Is qualitative research different?

The pervasive assumption underlying all these criticisms is that quantitative and qualitative approaches are fundamentally different in their ability to ensure the validity and reliability of their findings. This distinction, however, is more one of degree than of type. The problem of the relation of a piece of research to some presumed underlying “truth” applies to the conduct of any form of social research. “One of the greatest methodological fallacies of the last half century in social research is the belief that science is a particular set of techniques; it is, rather, a state of mind, or attitude, and the organisational conditions which allow that attitude to be expressed.” 1 In quantitative data analysis it is possible to generate statistical representations of phenomena which may or may not be fully justified since, just as in qualitative work, they will depend on the judgment and skill of the researcher and the appropriateness to the question answered of the data collected. All research is selective--there is no way that the researcher can in any sense capture the literal truth of events. All research depends on collecting particular sorts of evidence through the prism of particular methods, each of which has its strengths and weaknesses. For example, in a sample survey it is difficult for the researcher to ensure that the questions, categories, and language used in the questionnaire are shared uniformly by respondents and that the replies returned have the same meanings for all respondents. Similarly, research that relies exclusively on observation by a single researcher is limited by definition to the perceptions and introspection of the investigator and by the possibility that the presence of the observer may, in some way that is hard to characterise, have influenced the behaviour and speech that was witnessed. Britten and Fisher summarise the position neatly by pointing out that “there is some truth in the quip that quantitative methods are reliable but not valid and that qualitative methods are valid but not reliable.” 2

Strategies to ensure rigour in qualitative research

As in quantitative research, the basic strategy to ensure rigour in qualitative research is systematic and self conscious research design, data collection, interpretation, and communication. Beyond this, there are two goals that qualitative researchers should seek to achieve: to create an account of method and data which can stand independently so that another trained researcher could analyse the same data in the same way and come to essentially the same conclusions; and to produce a plausible and coherent explanation of the phenomenon under scrutiny. Unfortunately, many qualitative researchers have neglected to give adequate descriptions in their research reports of their assumptions and methods, particularly with regard to data analysis. This has contributed to some of the criticisms of bias from quantitative researchers.

Yet the integrity of qualitative projects can be protected throughout the research process. The remainder of this paper discusses how qualitative researchers attend to issues of validity, reliability, and generalisability.

Much social science is concerned with classifying different “types” of behaviour and distinguishing the “typical” from the “atypical.” In quantitative research this concern with similarity and difference leads to the use of statistical sampling so as to maximise external validity or generalisability. Although statistical sampling methods such as random sampling are relatively uncommon in qualitative investigations, there is no reason in principle why they cannot be used to provide the raw material for a comparative analysis, particularly when the researcher has no compelling a priori reason for a purposive approach. For example, a random sample of practices could be studied in an investigation of how and why teamwork in primary health care is more and less successful in different practices. However, since qualitative data collection is generally more time consuming and expensive than, for example, a quantitative survey, it is not usually practicable to use a probability sample. Furthermore, statistical representativeness is not a prime requirement when the objective is to understand social processes.

An alternative approach, often found in qualitative research and often misunderstood in medical circles, is to use systematic, non-probabilistic sampling. The purpose is not to establish a random or representative sample drawn from a population but rather to identify specific groups of people who either possess characteristics or live in circumstances relevant to the social phenomenon being studied. Informants are identified because they will enable exploration of a particular aspect of behaviour relevant to the research. This approach to sampling allows the researcher deliberately to include a wide range of types of informants and also to select key informants with access to important sources of knowledge.

“Theoretical” sampling is a specific type of non-probability sampling in which the objective of developing theory or explanation guides the process of sampling and data collection. 3 Thus, the analyst makes an initial selection of informants; collects, codes, and analyses the data; and produces a preliminary theoretical explanation before deciding which further data to collect and from whom. Once these data are analysed, refinements are made to the theory, which may in turn guide further sampling and data collection. The relation between sampling and explanation is iterative and theoretically led.

To return to the example of the study of primary care team working, some of the theoretically relevant characteristics of general practices affecting variations in team working might be the range of professions represented in the team, the frequency of opportunities for communication among team members, the local organisation of services, and whether the practice is in an urban, city, or rural area. These factors could be identified from other similar research and within existing social science theories of effective and ineffective team working and would then be used explicitly as sampling categories. Though not statistically representative of general practices, such a sample is theoretically informed and relevant to the research questions. It also minimises the possible bias arising from selecting a sample on the basis of convenience.

ENSURING THE RELIABILITY OF AN ANALYSIS

In many forms of qualitative research the raw data are collected in a relatively unstructured form such as tape recordings or transcripts of conversations. The main ways in which qualitative researchers ensure the retest reliability of their analyses is in maintaining meticulous records of interviews and observations and by documenting the process of analysis in detail. While it is possible to analyse such data singlehandedly and use ways of classifying and categorising the data which emerge from the analysis and remain implicit, more explicit group approaches, which perhaps have more in common with the quantitative social sciences, are increasingly used. The interpretative procedures are often decided on before the analysis. Thus, for example, computer software is available to facilitate the analysis of the content of interview transcripts. 4 A coding frame can be developed to characterise each utterance (for example, in relation to the age, sex, and role of the speaker; the topic; and so on), and transcripts can then be coded by more than one researcher. 5 One of the advantages of audiotaping or videotaping is the opportunity the tapes offer for subsequent analysis by independent observers.

The reliability of the analysis of qualitative data can be enhanced by organising an independent assessment of transcripts by additional skilled qualitative researchers and comparing agreement between the raters. For example, in a study of clinical encounters between cardiologists and their patients which looked at the differential value each derived from the information provided by echocardiography, transcripts of the clinic interviews were analysed for content and structure by the principal researcher and by an independent panel, and the level of agreement was assessed. 6

SAFEGUARDING VALIDITY

Alongside issues of reliability, qualitative researchers give attention to the validity of their findings. “Triangulation” refers to an approach to data collection in which evidence is deliberately sought from a wide range of different, independent sources and often by different means (for instance, comparing oral testimony with written records). This approach was used to good effect in a qualitative study of the effects of the introduction of general management into the NHS. The accounts of doctors, managers, and patient advocates were explored in order to identify patterns of convergence between data sources to see whether power relations had shifted appreciably in favour of professional managers and against the medical profession. 7

The differences in GPs' interviews with parents of handicapped and non-handicapped children have been shown by qualitative methods

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Validation strategies sometimes used in qualitative research are to feed the findings back to the participants to see if they regard the findings as a reasonable account of their experience 8 and to use interviews or focus groups with the same people so that their reactions to the evolving analysis become part of the emerging research data. 9 If used in isolation these techniques assume that fidelity to the participants' commonsense perceptions is the touchstone of validity. In practice, this sort of validation has to be set alongside other evidence of the plausibility of the research account since different groups are likely to have different perspectives on what is happening. 10

A related analytical and presentational issue is concerned with the thoroughness with which the researcher examines “negative” or “deviant” cases--those in which the researcher's explanatory scheme appears weak or is contradicted by the evidence. The researcher should give a fair account of these occasions and try to explain why the data vary. 11 In the same way, if the findings of a single case study diverge from those predicted by a previously stated theory, they can be useful in revising the existing theory in order to increase its reliability and validity.

VALIDITY AND EXPLANATION

It is apparent in qualitative research, particularly in observational studies (see the next paper in this series for more on observational methods), that the researcher can be regarded as a research instrument. 12 Allowing for the inescapable fact that purely objective observation is not possible in social science, how can the reader judge the credibility of the observer's account? One solution is to ask a set of questions: how well does this analysis explain why people behave in the way they do; how comprehensible would this explanation be to a thoughtful participant in the setting; and how well does the explanation it advances cohere with what we already know?

This is a challenging enough test, but the ideal test of a qualitative analysis, particularly one based on observation, is that the account it generates should allow another person to learn the “rules” and language sufficiently well to be able to function in the research setting. In other words, the report should carry sufficient conviction to enable someone else to have the same experience as the original observer and appreciate the truth of the account. 13 Few readers have the time or inclination to go to such lengths, but this provides an ideal against which the quality of a piece of qualitative work can be judged.

The development of “grounded theory” 3 offers another response to this problem of objectivity. Under the strictures of grounded theory, the findings must be rendered through a systematic account of a setting that would be clearly recognisable to the people in the setting (by, for example, recording their words, ideas, and actions) while at the same time being more structured and self consciously explanatory than anything that the participants themselves would produce.

Attending to the context

Some pieces of qualitative research consist of a case study carried out in considerable detail in order to produce a naturalistic account of everyday life. For example, a researcher wishing to observe care in an acute hospital around the clock may not be able to study more than one hospital. Again the issue of generalisability, or what can be learnt from a single case, arises. Here, it is essential to take care to describe the context and particulars of the case study and to flag up for the reader the similarities and differences between the case study and other settings of the same type. A related way of making the best use of case studies is to show how the case study contributes to and fits with a body of social theory and other empirical work. 12 The final paper in this series discusses qualitative case studies in more detail.

COLLECTING DATA DIRECTLY

Another defence against the charge that qualitative research is merely impressionistic is that of separating the evidence from secondhand sources and hearsay from the evidence derived from direct observation of behaviour in situ. It is important to ensure that the observer has had adequate time to become thoroughly familiar with the milieu under scrutiny and that the participants have had the time to become accustomed to having the researcher around. It is also worth asking whether the observer has witnessed a wide enough range of activities in the study site to be able to draw conclusions about typical and atypical forms of behaviour--for example, were observations undertaken at different times? The extent to which the observer has succeeded in establishing an intimate understanding of the research setting is often shown in the way in which the subsequent account shows sensitivity to the specifics of language and its meanings in the setting.

MINIMISING RESEARCHER BIAS IN THE PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

Although it is not normally appropriate to write up qualitative research in the conventional format of the scientific paper, with a rigid distinction between the results and discussion sections of the account, it is important that the presentation of the research allows the reader as far as possible to distinguish the data, the analytic framework used, and the interpretation. 1 In quantitative research these distinctions are conventionally and neatly presented in the methods section, numerical tables, and the accompanying commentary. Qualitative research depends in much larger part on producing a convincing account. 14 In trying to do this it is all too easy to construct a narrative that relies on the reader's trust in the integrity and fairness of the researcher. The equivalent in quantitative research is to present tables of data setting out the statistical relations between operational definitions of variables without giving any idea of how the phenomena they represent present themselves in naturally occurring settings. 1 The need to quantify can lead to imposing arbitrary categories on complex phenomena, just as data extraction in qualitative research can be used selectively to tell a story that is rhetorically convincing but scientifically incomplete.

The problem with presenting qualitative analyses objectively is the sheer volume of data customarily available and the relatively greater difficulty faced by the researcher in summarising qualitative data. It has been suggested that a full transcript of the raw data should be made available to the reader on microfilm or computer disk, 11 although this would be cumbersome. Another partial solution is to present extensive sequences from the original data (say, of conversations), followed by a detailed commentary.

Another option is to combine a qualitative analysis with some quantitative summary of the results. The quantification is used merely to condense the results to make them easily intelligible; the approach to the analysis remains qualitative since naturally occurring events identified on theoretical grounds are being counted. The table shows how Silverman compared the format of the doctor's initial questions to parents in a paediatric cardiology clinic when the child was not handicapped with a smaller number of cases when the child had Down's syndrome. A minimum of interpretation was needed to contrast the two sorts of interview. 15 16

Assessing a piece of qualitative research

This short paper has shown some of the ways in which researchers working in the qualitative tradition have endeavoured to ensure the rigour of their work. It is hoped that this summary will help the prospective reader of reports of qualitative research to identify some of the key questions to ask when trying to assess its quality. A range of helpful checklists has been published to assist readers of quantitative research assess the design 17 and statistical 18 and economic 19 aspects of individual published papers and review articles. 20 Likewise, the contents of this paper have been condensed into a checklist for readers of qualitative studies, covering design, data collection, analysis, and reporting (box). We hope that the checklist will give readers of studies in health and health care research that use qualitative methods the confidence to subject them to critical scrutiny.

Questions to ask of a qualitative study

Overall, did the researcher make explicit in the account the theoretical framework and methods used at every stage of the research?

Was the context clearly described?

Was the sampling strategy clearly described and justified?

Was the sampling strategy theoretically com-prehensive to ensure the generalisability of the conceptual analyses (diverse range of individuals and settings, for example)?

How was the fieldwork undertaken? Was it described in detail?

Could the evidence (fieldwork notes, inter-view transcripts, recordings, documentary analysis, etc) be inspected independently by others; if relevant, could the process of transcription be independently inspected?

Were the procedures for data analysis clearly described and theoretically justified? Did they relate to the original research questions? How were themes and concepts identified from the data?

Was the analysis repeated by more than one researcher to ensure reliability?

Did the investigator make use of quantitative evidence to test qualitative conclusions where appropriate?

Did the investigator give evidence of seeking out observations that might have contradicted or modified the analysis?

Was sufficient of the original evidence pre-sented systematically in the written account to satisfy the sceptical reader of the relation between the interpretation and the evidence (for example, were quotations numbered and sources given)?

Form of doctor's questions to parents at a paediatric cardiology clinic 15

- View inline

Further reading

Hammersley M. Reading ethnographic research. London: Longman, 1990.

- MacDonald I ,

- Britten N ,

- Glaser BG ,

- Krippendorff K

- Pollitt C ,

- Harrison S ,

- Hunter DJ ,

- McKeganey NP ,

- Glassner B ,

- Silverman D

- Fowkes FGR ,

- Gardner MJ ,

- Campbell MJ

- Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics

Ensuring rigour and trustworthiness of qualitative research in clinical pharmacy

- Research Article

- Published: 14 December 2015

- Volume 38 , pages 641–646, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Muhammad Abdul Hadi 1 &

- S. José Closs 2

17k Accesses

107 Citations

Explore all metrics

The use of qualitative research methodology is well established for data generation within healthcare research generally and clinical pharmacy research specifically. In the past, qualitative research methodology has been criticized for lacking rigour, transparency, justification of data collection and analysis methods being used, and hence the integrity of findings. Demonstrating rigour in qualitative studies is essential so that the research findings have the “integrity” to make an impact on practice, policy or both. Unlike other healthcare disciplines, the issue of “quality” of qualitative research has not been discussed much in the clinical pharmacy discipline. The aim of this paper is to highlight the importance of rigour in qualitative research, present different philosophical standpoints on the issue of quality in qualitative research and to discuss briefly strategies to ensure rigour in qualitative research. Finally, a mini review of recent research is presented to illustrate the strategies reported by clinical pharmacy researchers to ensure rigour in their qualitative research studies.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach

The Trustworthiness of Content Analysis

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2005.

Google Scholar

Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:42–5.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Anderson C. Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(8):6 Article 141 .

Article Google Scholar

Rolfe G. Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: quality and the idea of qualitative research. J Appl Nurs. 2006;53:304–10.

Long T, Johnson M. Rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. Clin Eeffect Nurs. 2000;4:30–7.

Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):331–9.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1985.

Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigour in qualitative research revisited. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1993;16:1–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1:13–22.

Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid Based Nurs. 2015;18:34–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–51.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181.

Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2006.

Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Ethnography: principles in practice. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 1995.

Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Edu Inform. 2004;22:63–75.

Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in feminist research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1986;8:27–37.

Nguyen TST. Peer debriefing. The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. 2008. http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/sage-encyc-qualitative-research-methods/n312.xml . Accessed 5 June 2014.

Ogunbayo OJ, Schafheutle EI, Cutts C, Noyce PR. A qualitative study exploring community pharmacists’ awareness of, and contribution to, self-care support in the management of long-term conditions in the United Kingdom. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014 [Published online Feb, 2015].

Shiyanbola OO, Mort JR. Exploring consumer understanding and preferences for pharmacy quality information. Pharm Pract. 2014;12:1–11.

Murphy A, Szumilas M, Rowe D, et al. Pharmacy students’ experiences in provision of community pharmacy mental health services. Can Pharm J. 2014;147:55–65.

Ryder H, Aspden T, Sheridan J. The Hawke’s Bay Condom Card Scheme: a qualitative study of the views of service providers on increased, discreet access for youth to free condoms. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12178 .

Ziaei Z, Hassell K, Schafheutle EI. Internationally trained pharmacists’ perception of their communication proficiency and their views on the impact on patient safety. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2015;11:428–41.

Hasan S, Stewart K, Chapman CB, Hasan MY, Kong DCM. Physicians’ attitudes towards provision of primary care services in community pharmacy in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12157 .

PubMed Google Scholar

Marquis J, Schneider MP, Spencer B, Bugnon O, Pasquier SD. Exploring the implementation of a medication adherence programme by community pharmacists: a qualitative study Int J. Clin Pharm. 2014;36:1014–22.

Swain L, Griffits C, Lisa Pont L, Barclay L. Attitudes of pharmacists to provision of home medicines review for indigenous Australians. Int. J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:1260–7.

Brazinha I, Fernandez-Llimos F. Barriers to the implementation of advanced clinical pharmacy services at Portuguese hospitals Int J. Clin Pharm. 2014;36:1031–8.

Odukoya OK, Stone JA, Chui MA. Barriers and facilitators to recovering from e- prescribing errors in community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2015;55:52–8.

Download references

No funding from any governmental or non-governmental agency was obtained for this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Umm-Al-Qura University, Al-Abdia, Makkah, 13578, Saudi Arabia

Muhammad Abdul Hadi

School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, LS2 9UT, Leeds, UK

S. José Closs

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Muhammad Abdul Hadi .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

None declared.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hadi, M.A., José Closs, S. Ensuring rigour and trustworthiness of qualitative research in clinical pharmacy. Int J Clin Pharm 38 , 641–646 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0237-6

Download citation

Received : 16 August 2015

Accepted : 08 December 2015

Published : 14 December 2015

Issue Date : June 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0237-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Clinical pharmacy

- Qualitative research

- Trustworthiness

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- Expert advice

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Issues in research Previous Next

Rigour in qualitative research: mechanisms for control, kimberley ryan-nicholls associate professor, university of calgary, calgary, canada, department of psychiatric nursing, school of health studies, brandon university, brandon, canada, constance will associate professor, department of nursing, school of health studies, brandon university, brandon, canada.

Qualitative researchers have been criticised for a perceived failure to demonstrate methodological rigour. Kimberley D Ryan-Nicholls and Constance I Will offer cautionary recommendations related to the mechanisms for control of methodological rigour in qualitative inquiry

Qualitative research methods are accepted as congruent with and relevant to the perspective and goals of nursing. There exists, however, continued criticism of the methodological rigour of qualitative work ( Sandelowski 1986 , 2004 , Farmer et al 2006 , Morse 2006a , 2006b ). This now informs how qualitative work is considered with the current emphasis on evidence-based practice ( Grypdonck 2006 , Morse 2006a , 2006b , Sandelowski et al 2006 ). What is the basis of this criticism? How can methodological rigour be demonstrated? Furthermore, what is rigour and what are the key issues for qualitative researchers? This paper attempts to answer these questions.

Nurse Researcher . 16, 3, 70-85. doi: 10.7748/nr2009.04.16.3.70.c6947

qualitative research - methodology - rigour - nursing research

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

01 April 2009 / Vol 16 issue 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Rigour in qualitative research: mechanisms for control

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

- AACP Member Login Submit

Download started.

- PDF [516 KB] PDF [516 KB]

- Figure Viewer

- Download Figures (PPT)

- Add To Online Library Powered By Mendeley

- Add To My Reading List

- Export Citation

- Create Citation Alert

A Review of the Quality Indicators of Rigor in Qualitative Research

- Jessica L. Johnson, PharmD Jessica L. Johnson Correspondence Corresponding Author: Jessica L. Johnson, William Carey University School of Pharmacy, 19640 Hwy 67, Biloxi, MS 39574. Tel: 228-702-1897. Contact Affiliations William Carey University School of Pharmacy, Biloxi, Mississippi Search for articles by this author

- Donna Adkins, PharmD Donna Adkins Affiliations William Carey University School of Pharmacy, Biloxi, Mississippi Search for articles by this author

- Sheila Chauvin, PhD Sheila Chauvin Affiliations Louisiana State University, School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana Search for articles by this author

- qualitative research design

- standards of rigor

- best practices

INTRODUCTION

- Denzin Norman

- Lincoln Y.S.

- Google Scholar

- Anderson C.

- Full Text PDF

- Scopus (584)

- Santiago-Delefosse M.

- Stephen S.L.

- Scopus (85)

- Scopus (32)

- Levinson W.

- Scopus (506)

- Dixon-Woods M.

- Scopus (440)

- Malterud K.

- Midtgarden T.

- Scopus (205)

- Wasserman J.A.

- Wilson K.L.

- Scopus (68)

- Barbour R.S.

- Sale J.E.M.

- Scopus (12)

- Fraser M.W.

- Scopus (37)

- Sandelowski M.

- Scopus (1571)

BEST PRACTICES: STEP-WISE APPROACH

Step 1: identifying a research topic.

- Scopus (288)

- Creswell J.

- Maxwell J.A.

- Glassick C.E.

- Maeroff G.I.

- Scopus (269)

- Scopus (279)

- Ringsted C.

- Scherpbier A.

- Scopus (132)

- Ravitch S.M.

- View Large Image

- Download Hi-res image

- Download (PPT)

- Huberman M.

Step 2: Qualitative Study Design

- Whittemore R.

- Mandle C.L.

- Scopus (987)

- Marshall M.N.

- Scopus (2232)

- Horsfall J.

- Scopus (185)

- O’Reilly M.

- Scopus (1072)

- Burkard A.W.

- Scopus (168)

- Patton M.Q.

- Scopus (364)

- Scopus (4280)

- Johnson R.B.

Step 3: Data Analysis

Step 4: drawing valid conclusions.

- Swanwick T.

- Swanwick T.O.

- O’Brien B.C.

- Harris I.B.

- Beckman T.J.

- Scopus (5009)

Step 5: Reporting Research Results

- Shenton A.K.

- Scopus (4221)

Article info

Publication history, identification.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7120

ScienceDirect

- Download .PPT

Related Articles

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Journal Information

- About Open Access

- Aims & Scope

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Team

- History of AJPE

- Contact Information

- For Authors

- Guide for Authors

- Researcher Academy

- Rights & Permissions

- Submission Process

- Submit Article

- For Reviewers

- Reviewer Instructions

- Reviewer Frequently Asked Questions

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.7 Quantitative Rigour

The extent to which the researchers strive to improve the quality of their study is referred to as rigour. Rigour is accomplished in quantitative research by measuring validity and reliability. 55 These concepts affect the quality of findings and their applicability to broader populations.

Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure. It is the extent to which a study or test accurately measures what it sets out to measure. There are three main types of validity – content, construct and criterion validity.

- Content validity: Content validity examines whether the instrument adequately covers all aspects of the content that it should with respect to the variable under investigation. 56 This type of validity can be assessed through expert judgment and by examining the coverage of items or questions in measure. 56 Face validity is a subset of content validity in which experts are consulted to determine if a measurement tool accurately captures what it is supposed to measure. 56 There are multiple methods for testing content validity – content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR). CVI is calculated as the number of experts giving a rating of “very relevant” for each item divided by the total number of experts. Values range from 0 to 1, with items having a CVI score > 0.79 relevant; between 0.70 and 0.79, the item needs revisions, and if the value is below 0.70, the item is eliminated. 57 CVR varies between 1 and −1; a higher score indicates greater agreement among panel members. CVR is calculated as (Ne – N/2)/(N/2), where Ne is the number of panellists indicating an item as “essential” and N is the total number of panelists. 57 A study by Mousazadeh et al. 2017 investigated the content, face validity and reliability of sociocultural attitude towards appearance questionnaire-3 (SATAQ-3) among female adolescents. 58 To ensure face validity, the questionnaire was given to 25 female adolescents, a psychologist and three nurses, who were required to evaluate the items with respect to problems, ambiguity, relativity, proper terms and grammar, and understandability. For content validity, 15 experts in psychology and nursing were asked to assess the qualitative content validity. To determine the quantitative content validity, the content validity index and content validity ratio were calculated. 58

- Construct validity: A construct is an idea or theoretical concept based on empirical observations that are not directly measurable. An example of a construct could be physical functioning or social anxiety. Thus construct validity determines whether an instrument measures the underlying construct of interest and discriminates it from other related constructs. 55 It is important and expresses the confidence that a particular construct is valid. 55 This type of validity can be assessed using factor analysis or other statistical techniques. For example, Pinar, Rukiye 2005 , evaluated the reliability and construct validity of the SF-36 in Turkish cancer patients. 59 The SF-36 is widely used to measure the quality of life or health status in sick and healthy populations. Principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation confirmed the presence of the seven domains in the SF-36: in the SF-36: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical and emotional problems, mental health, general health perception, bodily pain, social functioning, and vitality. It was concluded that the Turkish version of the SF-36 was a suitable instrument that could be employed in cancer research in Turkey. 59