14 important environmental impacts of tourism + explanations + examples

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

The environmental impacts of tourism have gained increasing attention in recent years.

With the rise in sustainable tourism and an increased number of initiatives for being environmentally friendly, tourists and stakeholders alike are now recognising the importance of environmental management in the tourism industry.

In this post, I will explain why the environmental impacts of tourism are an important consideration and what the commonly noted positive and negative environmental impacts of tourism are.

Why the environment is so important to tourism

Positive environmental impacts of tourism, water resources, land degradation , local resources , air pollution and noise , solid waste and littering , aesthetic pollution, construction activities and infrastructure development, deforestation and intensified or unsustainable use of land , marina development, coral reefs, anchoring and other marine activities , alteration of ecosystems by tourist activities , environmental impacts of tourism: conclusion, environmental impacts of tourism reading list.

The quality of the environment, both natural and man-made, is essential to tourism. However, tourism’s relationship with the environment is complex and many activities can have adverse environmental effects if careful tourism planning and management is not undertaken.

It is ironic really, that tourism often destroys the very things that it relies on!

Many of the negative environmental impacts that result from tourism are linked with the construction of general infrastructure such as roads and airports, and of tourism facilities, including resorts, hotels, restaurants, shops, golf courses and marinas. The negative impacts of tourism development can gradually destroy the environmental resources on which it depends.

It’s not ALL negative, however!

Tourism has the potential to create beneficial effects on the environment by contributing to environmental protection and conservation. It is a way to raise awareness of environmental values and it can serve as a tool to finance protection of natural areas and increase their economic importance.

In this article I have outlined exactly how we can both protect and destroy the environment through tourism. I have also created a new YouTube video on the environmental impacts of tourism, you can see this below. (by the way- you can help me to be able to keep content like this free for everyone to access by subscribing to my YouTube channel! And don’t forget to leave me a comment to say hi too!).

Although there are not as many (far from it!) positive environmental impacts of tourism as there are negative, it is important to note that tourism CAN help preserve the environment!

The most commonly noted positive environmental impact of tourism is raised awareness. Many destinations promote ecotourism and sustainable tourism and this can help to educate people about the environmental impacts of tourism. Destinations such as Costa Rica and The Gambia have fantastic ecotourism initiatives that promote environmentally-friendly activities and resources. There are also many national parks, game reserves and conservation areas around the world that help to promote positive environmental impacts of tourism.

Positive environmental impacts can also be induced through the NEED for the environment. Tourism can often not succeed without the environment due the fact that it relies on it (after all we can’t go on a beach holiday without a beach or go skiing without a mountain, can we?).

In many destinations they have organised operations for tasks such as cleaning the beach in order to keep the destination aesthetically pleasant and thus keep the tourists happy. Some destinations have taken this further and put restrictions in place for the number of tourists that can visit at one time.

Not too long ago the island of Borocay in the Philippines was closed to tourists to allow time for it to recover from the negative environmental impacts that had resulted from large-scale tourism in recent years. Whilst inconvenient for tourists who had planned to travel here, this is a positive example of tourism environmental management and we are beginning to see more examples such as this around the world.

Negative environmental impacts of tourism

Negative environmental impacts of tourism occur when the level of visitor use is greater than the environment’s ability to cope with this use.

Uncontrolled conventional tourism poses potential threats to many natural areas around the world. It can put enormous pressure on an area and lead to impacts such as: soil erosion , increased pollution, discharges into the sea, natural habitat loss, increased pressure on endangered species and heightened vulnerability to forest fires. It often puts a strain on water resources, and it can force local populations to compete for the use of critical resources.

I will explain each of these negative environmental impacts of tourism below.

Depletion of natural resources

Tourism development can put pressure on natural resources when it increases consumption in areas where resources are already scarce. Some of the most common noted examples include using up water resources, land degradation and the depletion of other local resources.

The tourism industry generally overuses water resources for hotels, swimming pools, golf courses and personal use of water by tourists. This can result in water shortages and degradation of water supplies, as well as generating a greater volume of waste water.

In drier regions, like the Mediterranean, the issue of water scarcity is of particular concern. Because of the hot climate and the tendency for tourists to consume more water when on holiday than they do at home, the amount used can run up to 440 litres a day. This is almost double what the inhabitants of an average Spanish city use.

Golf course maintenance can also deplete fresh water resources.

In recent years golf tourism has increased in popularity and the number of golf courses has grown rapidly.

Golf courses require an enormous amount of water every day and this can result in water scarcity. Furthermore, golf resorts are more and more often situated in or near protected areas or areas where resources are limited, exacerbating their impacts.

An average golf course in a tropical country such as Thailand needs 1500kg of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides per year and uses as much water as 60,000 rural villagers.

Important land resources include fertile soil, forests , wetlands and wildlife. Unfortunately, tourism often contributes to the degradation of said resources. Increased construction of tourism facilities has increased the pressure on these resources and on scenic landscapes.

Animals are often displaced when their homes are destroyed or when they are disturbed by noise. This may result in increased animals deaths, for example road-kill deaths. It may also contribute to changes in behaviour.

Animals may become a nuisance, by entering areas that they wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) usually go into, such as people’s homes. It may also contribute towards aggressive behaviour when animals try to protect their young or savage for food that has become scarce as a result of tourism development.

Picturesque landscapes are often destroyed by tourism. Whilst many destinations nowadays have limits and restrictions on what development can occur and in what style, many do not impose any such rules. High rise hotels and buildings which are not in character with the surrounding architecture or landscape contribute to a lack of atheistic appeal.

Forests often suffer negative impacts of tourism in the form of deforestation caused by fuel wood collection and land clearing. For example, one trekking tourist in Nepal can use four to five kilograms of wood a day!

There are also many cases of erosion, whereby tourists may trek the same path or ski the same slope so frequently that it erodes the natural landscape. Sites such as Machu Pichu have been forced to introduce restrictions on tourist numbers to limit the damage caused.

Tourism can create great pressure on local resources like energy, food, and other raw materials that may already be in short supply. Greater extraction and transport of these resources exacerbates the physical impacts associated with their exploitation.

Because of the seasonal character of the industry, many destinations have ten times more inhabitants in the high season as in the low season.

A high demand is placed upon these resources to meet the high expectations tourists often have (proper heating, hot water, etc.). This can put significant pressure on the local resources and infrastructure, often resulting in the local people going without in order to feed the tourism industry.

Tourism can cause the same forms of pollution as any other industry: Air emissions; noise pollution; solid waste and littering; sewage; oil and chemicals. The tourism industry also contributes to forms of architectural/visual pollution.

Transport by air, road, and rail is continuously increasing in response to the rising number of tourists and their greater mobility. In fact, tourism accounts for more than 60% of all air travel.

One study estimated that a single transatlantic return flight emits almost half the CO2 emissions produced by all other sources (lighting, heating, car use, etc.) consumed by an average person yearly- that’s a pretty shocking statistic!

I remember asking my class to calculate their carbon footprint one lesson only to be very embarrassed that my emissions were A LOT higher than theirs due to the amount of flights I took each year compared to them. Point proven I guess….

Anyway, air pollution from tourist transportation has impacts on a global level, especially from CO2 emissions related to transportation energy use. This can contribute to severe local air pollution . It also contributes towards climate change.

Fortunately, technological advancements in aviation are seeing more environmentally friendly aircraft and fuels being used worldwide, although the problem is far from being cured. If you really want to help save the environment, the answer is to seek alternative methods of transportation and avoid flying.

You can also look at ways to offset your carbon footprint .

Noise pollution can also be a concern.

Noise pollution from aircraft, cars, buses, (+ snowmobiles and jet skis etc etc) can cause annoyance, stress, and even hearing loss for humans. It also causes distress to wildlife and can cause animals to alter their natural activity patterns. Having taught at a university near London Heathrow for several years, this was always a topic of interest to my students and made a popular choice of dissertation topic .

In areas with high concentrations of tourist activities and appealing natural attractions, waste disposal is a serious problem, contributing significantly to the environmental impacts of tourism.

Improper waste disposal can be a major despoiler of the natural environment. Rivers, scenic areas, and roadsides are areas that are commonly found littered with waste, ranging from plastic bottles to sewage.

Cruise tourism in the Caribbean, for example, is a major contributor to this negative environmental impact of tourism. Cruise ships are estimated to produce more than 70,000 tons of waste each year.

The Wider Caribbean Region, stretching from Florida to French Guiana, receives 63,000 port calls from ships each year, and they generate 82,000 tons of rubbish. About 77% of all ship waste comes from cruise vessels. On average, passengers on a cruise ship each account for 3.5 kilograms of rubbish daily – compared with the 0.8 kilograms each generated by the less well-endowed folk on shore.

Whilst it is generally an unwritten rule that you do not throw rubbish into the sea, this is difficult to enforce in the open ocean . In the past cruise ships would simply dump their waste while out at sea. Nowadays, fortunately, this is less commonly the case, however I am sure that there are still exceptions.

Solid waste and littering can degrade the physical appearance of the water and shoreline and cause the death of marine animals. Just take a look at the image below. This is a picture taken of the insides of a dead bird. Bird often mistake floating plastic for fish and eat it. They can not digest plastic so once their stomachs become full they starve to death. This is all but one sad example of the environmental impacts of tourism.

Mountain areas also commonly suffer at the hands of the tourism industry. In mountain regions, trekking tourists generate a great deal of waste. Tourists on expedition frequently leave behind their rubbish, oxygen cylinders and even camping equipment. I have heard many stories of this and I also witnessed it first hand when I climbed Mount Kilimanjaro .

The construction of hotels, recreation and other facilities often leads to increased sewage pollution.

Unfortunately, many destinations, particularly in the developing world, do not have strict law enrichments on sewage disposal. As a result, wastewater has polluted seas and lakes surrounding tourist attractions around the world. This damages the flora and fauna in the area and can cause serious damage to coral reefs.

Sewage pollution threatens the health of humans and animals.

I’ll never forget the time that I went on a school trip to climb Snowdonia in Wales. The water running down the streams was so clear and perfect that some of my friends had suggested we drink some. What’s purer than mountain fresh water right from the mountain, right?

A few minutes later we saw a huge pile of (human??) feaces in the water upstream!!

Often tourism fails to integrate its structures with the natural features and indigenous architecture of the destination. Large, dominating resorts of disparate design can look out of place in any natural environment and may clash with the indigenous structural design.

A lack of land-use planning and building regulations in many destinations has facilitated sprawling developments along coastlines, valleys and scenic routes. The sprawl includes tourism facilities themselves and supporting infrastructure such as roads, employee housing, parking, service areas, and waste disposal. This can make a tourist destination less appealing and can contribute to a loss of appeal.

Physical impacts of tourism development

Whilst the tourism industry itself has a number of negative environmental impacts. There are also a number of physical impacts that arise from the development of the tourism industry. This includes the construction of buildings, marinas, roads etc.

The development of tourism facilities can involve sand mining, beach and sand dune erosion and loss of wildlife habitats.

The tourist often will not see these side effects of tourism development, but they can have devastating consequences for the surrounding environment. Animals may displaced from their habitats and the noise from construction may upset them.

I remember reading a while ago (although I can’t seem to find where now) that in order to develop the resort of Kotu in The Gambia, a huge section of the coastline was demolished in order to be able to use the sand for building purposes. This would inevitably have had severe consequences for the wildlife living in the area.

Construction of ski resort accommodation and facilities frequently requires clearing forested land.

Land may also be cleared to obtain materials used to build tourism sites, such as wood.

I’ll never forget the site when I flew over the Amazon Rainforest only to see huge areas of forest cleared. That was a sad reality to see.

Likewise, coastal wetlands are often drained due to lack of more suitable sites. Areas that would be home to a wide array of flora and fauna are turned into hotels, car parks and swimming pools.

The building of marinas and ports can also contribute to the negative environmental impacts of tourism.

Development of marinas and breakwaters can cause changes in currents and coastlines.

These changes can have vast impacts ranging from changes in temperatures to erosion spots to the wider ecosystem.

Coral reefs are especially fragile marine ecosystems. They suffer worldwide from reef-based tourism developments and from tourist activity.

Evidence suggests a variety of impacts to coral result from shoreline development. Increased sediments in the water can affect growth. Trampling by tourists can damage or even kill coral. Ship groundings can scrape the bottom of the sea bed and kill the coral. Pollution from sewage can have adverse effects.

All of these factors contribute to a decline and reduction in the size of coral reefs worldwide. This then has a wider impact on the global marine life and ecosystem, as many animals rely on the coral for as their habitat and food source.

Physical impacts from tourist activities

The last point worth mentioning when discussing the environmental impacts of tourism is the way in which physical impacts can occur as a result of tourist activities.

This includes tramping, anchoring, cruising and diving. The more this occurs, the more damage that is caused. Natural, this is worse in areas with mass tourism and overtourism .

Tourists using the same trail over and over again trample the vegetation and soil, eventually causing damage that can lead to loss of biodiversity and other impacts.

Such damage can be even more extensive when visitors frequently stray off established trails. This is evidenced in Machu Pichu as well as other well known destinations and attractions, as I discussed earlier in this post.

In marine areas many tourist activities occur in or around fragile ecosystems.

Anchoring, scuba diving, yachting and cruising are some of the activities that can cause direct degradation of marine ecosystems such as coral reefs. As I said previously, this can have a significant knock on effect on the surrounding ecosystem.

Habitats can be degraded by tourism leisure activities.

For example, wildlife viewing can bring about stress for the animals and alter their natural behaviour when tourists come too close.

As I have articulated throughout this post, there are a range of environmental impacts that result from tourism. Whilst some are good, the majority unfortunately are bad. The answer to many of these problems boils down to careful tourism planning and management and the adoption of sustainable tourism principles.

Did you find this article helpful? Take a look at my posts on the social impacts of tourism and the economic impacts of tourism too! Oh, and follow me on social media !

If you are studying the environmental impacts of tourism or if you are interested in learning more about the environmental impacts of tourism, I have compiled a short reading list for you below.

- The 3 types of travel and tourism organisations

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 50 fascinating facts about the travel and tourism industry

Liked this article? Click to share!

Environmental Impacts of Tourism Research Paper

Introduction, the relevance of the problem, current situation, future outcomes, possible solutions, works cited.

The sphere of tourism is reliant on the environment of the sites in which the visitors are interested. Therefore, the preservation of these territories is crucial to preserving their profitability and public appeal. Nevertheless, the growing tourist industry has been examined by scholars and found to be extremely damaging to plants, animals, and people of the visited regions. Throughout history, popular tourist activities have been disturbing the wildlife and affecting communities that cannot resist the pressure from businesses. The idea that tourism helps countries and cities to improve their economy also weakens people’s arguments against increasing the sphere of traveling and sightseeing.

One can provide innumerable examples of tourist activities disturbing the environment. Some of these influences are local, while others often reach a global scale. Wilson and Verlis, for example, explore the southern Great Barrier Reef – a place where thousands of tourists travel every year to look at one of the world’s wonders (239). However, what these people leave behind them damages the reef – marine debris near this and similar attractions lead to the depletion of wildlife and destruction of coral reefs.

As a result, the source of fascination (and, thus, profit) disappears as more tourists enter the region. The problem of pollution is not confined to such landmarks as the described coral reef. The effects are similar – people who enter new territories often exhibit behavior that produces waste, pollutes the air and the water, and changes wildlife’s natural order. Companies do not prevent this behavior and even contribute to it by expanding the tourism industry and virtually rebuilding environments to suit their need for profit.

Looking at the issues and results of tourism, the question of nature preservation arises. It is vital to determine what changes in policy and people’s knowledge about the environment have to be introduced in order to stop the industry from destroying what is left from sites affected by tourism. Moreover, one should also examine how these improvements can be implemented to provide successful results. Stefănica and Butnaru explore the beliefs of modern tourists towards environmental preservation, noting that most of these people can and should be taught about the dangers of naïve and neglectful tourist behavior (595).

Nonetheless, they also find that individual actions are infective – companies that enforce new regulations and operate in the industry should also adopt systems to preserve nature. The problem of environmental destruction is directly and indirectly influenced by tourists and companies that promote the tourist industry. A variety of solutions that incorporate social responsibility and public awareness should be complemented with policy restrictions in order to save the environment and protect the planet from consequences that are dangerous to all people.

The issue of tourism being a source of environmental pollution and destruction is a topic that requires consideration right now. The industry of invasive tourism continues to grow – people are becoming more and more interested in traveling to the parts of nature that were previously untouched by humans or developed civilizations. This desire leads to multiple effects, most of which are detrimental to the environment and its inhabitants. Furthermore, as people discover new ways of traveling or exploring new areas, the industry requires additional resources to accommodate the growing rate of tourists. This ever increasing ability to engage new regions and communities in tourism further enhances the impact of destructive behaviors.

It is especially visible in the luxury segment of traveling where people are provided with extensive resources and are called to enjoy various activities which cause increased waste production or significant setting’s change. In this case, cruise tourism can be used as an example of a luxurious traveling vehicle being used without any with limited efforts of environmental sustainability (Lamers et al. 430). This and other ways of traveling do not contribute to wildlife preservation.

Another side of the problem is concerned with the businesses’ contemporary measures to save the environment while retaining the attractiveness of tourist sights. Some modern tools do not provide any actual protection to nature, becoming a way to promote specific areas instead. This issue is explored by Klein and Dodds who find that Blue Flag beach certification, although being introduced as a way to award sustainable beaches, does not operate as such (43).

As a contrast, the companies that compete for this certification perceive this project as a strategic step towards making their beaches more attractive to tourists. Thus, the problem of tourism affecting the environment is pressing – the industry grows while the modern ways of preservation are not working or being implemented efficiently.

Tourism had been popular among many communities for centuries since it is in line with people’s curiosity and desire to explore new territories and cultures. As Mowforth and Munt note, the western economic growth and prosperity resulted in these societies becoming interested in exploring new lands for profit (174).

In turn, the countries that were less fortunate in gaining independence or developing strong economics became the targets of tourism, especially if they also had a rich history and culture or nature. Another type of attraction that appeared with time is the territories that are not inhabited by humans or developed cultures. These range from areas with wildlife to regions with communities that are removed from the contemporary understanding of advanced civilizations.

The Eurocentric vision implored other countries to assimilate and mimic the dominant cultures at the risk of becoming entirely dependent on them. In regards to tourism, many communities have embraced the place of the tourism industry in their life and allowed businesses to affect their environments. The territories which did not have a governmental structure to protect or regulate the area were also utilized for industry expansion. Lamers et al. provide an example of Antarctica as a destination that became popular after the 1960s and was changed as a result of interventions (436). The emissions of greenhouse gasses increased greatly, endangering the climate of the region and significantly affecting its wildlife.

Moreover, water pollution also impacted the marine life forms of the area. Thus, the national governments had to develop the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) to limit tourism by introducing a ban on heavy marine fuel and other guidelines. Only such level of regulation was effective in limiting the effect of tourism on Antarctica, although this solution is only temporary.

Currently, all regions of the world are affected by tourism. The mentioned above example of Antarctica is one of many locations where people’s curiosity coupled with a disregard for environmental preservation has led to devastating results. Returning to the case of Wilson and Verlis, one may see that the marine pollution levels are extremely high in all oceans. The authors have recovered many samples of debris from beaches and waters in the Great Barrier Reef region, with more than four items being accumulated every day in some areas (Wilson and Verlis 241).

The most common type of waste was plastic – a material that cannot rot or disintegrate, thus becoming a permanent part of the environment. In fact, 68 to 92 percent of all debris was made out of plastic materials, thus putting animals and plants at risk of death or contamination (Wilson and Verlis 242). This example demonstrates how damaging the current tourism industry is to the environment.

Another place that is endangered by tourism is the Maldives. This region and other similar groups of small islands often become a destination for many tourist groups. Here, the problem of environmental destruction is closely tied to the territories’ reliance on tourism as an economic resource. Kapmeier and Gonçalves state that Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as the Maldives are faced with an issue of finding a balance between the financial value of tourism and its environmental burden (175). The tropical paradise” of the Maldives constitutes a number of small islands with an extremely fragile ecosystem full of animals unique to the region.

The introduction of tourists after the 1970s changed the culture and the wildlife as well. First, more buildings started appearing on the islands to accommodate the arriving visitors. Thus, the construction began altering the landscape of the Maldives. As more and more tourists discovered the Maldives, the country was able to build additional hotels and introduce new methods of transportation such as seaplanes and boats (Kapmeier and Gonçalves 178). These developments, while stabilizing the growth of the local economy, also contributed to the islands’ pollution.

Similarly to the Great Barrier Reef, the waters of the Maldives have become filled with debris, and the country also suffers from increased waste generation. Kapmeier and Gonçalves estimate that the local population produces around 120 tons of waste every day, while each tourist generates an additional 3.5kg per day (180). This calculation implies that 1 million tourists can stay for eight days and add 33,600 tons of solid waste to the total number (Kapmeier and Gonçalves 180).

The additional amount of garbage is substantial leading to the country losing ways of garbage disposal that were effective before. As a result, locals leave waste outside or burn it, polluting the water, soil, and air with items that are often non-biodegradable.

Again, plastic constituted a large portion of all items examined by the scholars, but almost a half of all solid waste was food, and 90% of such products were discarded into the sea (Kapmeier and Gonçalves 181). Thus, it becomes clear that many resorts cannot handle the number of tourists that arrive each year. While the expansion of tourist zones leads to the creation of new housing and service opportunities, the majority of all visitors try to enter into popular areas, placing more pressure on historically and environmentally essential regions.

Although such types of waste as food and some plastics can be recycled, the actual situation shows that they are either burned or thrown into the ocean (Kapmeier and Gonçalves 182). Tourism does not assist countries in creating new paths for non-harmful disposal, and the islands face pressure to clear out the trash utilizing unethical methods.

The discussed above problem of cruise tourism is highlighted as one of the issues that are more tied to the mode of transportation rather than a particular destination point. Carić and Mackelworth argue that, during each cruise trip, the environment suffers outcomes of three types of pollution – transportation, docking, and activities on the board of the ship (350). First of all, people consume water and food during their stay on the vehicle, being usually more wasteful than they would be on land since resources have to be stored on the ship.

Second, the movement of the boat requires fuel, leading to air pollution with emission gasses and water pollution with oil spills and other products of the working engine. Finally, as the ship arrives at some territories, tourists may leave waste on land as well as disturb the soil, animals, or plants. Therefore, apart from targeting particular nations and regions, tourism introduces global risks through promoting transportation dangerous to the environment.

The current state of tourism and its continuous expansion may lead to a myriad of negative consequences. The pollution of water and air can significantly alter flora and fauna of the planet, causing the elimination of whole species. Furthermore, some animals adapt to humans’ presence and change their behavior and eating habits. Carić and Mackelworth find that the disposal of plastics into the ocean results in the death of sea turtles that get caught in debris (353).

Some mammals ingest granules of plastic and die from poisoning. This can also affect human health – if a person consumes an animal ingested with plastic, the former can succumb to intoxication as well. Thus, tourism can impact human health indirectly through animals in addition to exposing numbers of tourists to polluted air, food, and water.

The indigenous people living in or near popular traveling destinations also suffer from the outcomes of tourism. Their economy becomes dependent on the industry as it is happening in the Maldives. Otherwise, they are impacted by pollution and waste accumulating in the area. They are also more likely to introduce new habits into their cultural system under the influence of arriving individuals. As one can see, tourism does not have an exclusively positive effect on impoverished nations or those people who lack technological advancement. Tourism creates settings that are challenged by consumerism and unethical behavior of people who enter the region for a short period of time but leave a considerable imprint.

One separate action cannot solve the problem of unethical tourism since the industry is large and it attracts millions of people every year. Countries, companies, and individuals need to make a conscious effort to change their policies and beliefs in order to start lowering the impact of traveling on the environment. First of all, it should be remarked that the improvement of waste disposal is not an effective strategy by itself.

Kapmeier and Gonçalves argue that by introducing a new system of waste management, the Maldives and similar locations will make their area more appealing to tourists (172). As a result, such countries will only encounter the challenge of increasing waste accumulation and pressure from companies to accommodate more people. The authors suggest that legal policies curbing tourism demand may be a practical addition to better waste control.

The legal restrictions are difficult to discuss on the international level since many countries depend on tourism as a source of profit. States should base their ideologies on environmentally-friendly policies that will protect peoples and species without closing the borders to people. Perhaps, a limitation on tourist capacity and the decrease in luxury or wasteful practices is necessary to lower the pressure on the environment. Another option is the introduction and development of ecotourism – a set of mindful practices that are focused on the reduction of harm to nature.

Gavrilović and Maksimović discuss green innovations that may improve the influence of the tourism industry. They note that “greening” the sector requires efforts from businesses which should be motivated by maintaining their place and profitability by restoring and managing the environment to attract customers. The scholars highlight the adverse outcomes of pollution and point out that by damaging the ecosystems, the companies may lose their auditory and economic stability as well (Gavrilović and Maksimović 41). Environmental awareness can create a cycle that will be beneficial to customers, firms, and nature.

The role of individual understanding of tourism’s impact is also vital to preserving nature. Chiu et al. argue that ecotourism can become a popular way of traveling, especially if people understand its purpose (327). This approach is focused on enjoying natural resources and choosing activities that do not adversely impact the environment. For example, such people control their waste, engage in recycling and cleaning (trash sorting, use of organic materials), do not enter protected areas, and try not to interfere with local flora and fauna.

The problem with raising awareness and changing people’s behaviors may lie in the fact that modern tourism is more focused on luxury and experiences than on thinking about the future of these territories. The introduction of ecotourism should start with education about the harms of unethical behavior. Moreover, individuals should understand the ecotourism can make them feel content with themselves and make a good impression on others, further changing the system of tourism.

Each contributing factor, including tourist actions, governmental policies, and businesses operations can positively influence the state of ecotourism and benefit the environment. Stefănica and Butnaru offer a number of changes such as the use of transportation which produces less waste than others and an effort to lower energy and water consumption as well as waste production (600). Moreover, tourists and firms should participate in recycling and proper disposal, while preserving flora and fauna. Some may even contribute to the restoration of the environment – people can plant trees, use renewable energy sources, clean water, and collect waste. Finally, on the state level, nations should discuss the possibility of adding taxes for environmental protection that would be used for innovative ways of managing the tourism industry.

Tourism is an activity that allows people to see the world and learn about other cultures and the environment. However, tourists and involved companies often exhibit behavior that damages the planet and leads to its destruction. It is especially visible in regions where tourism is a part of the national economy – people, animals, and plants suffer from extensive use of resources and waste brought and left by visitors.

Countries dependent on other nations and corporate needs for profit cannot adequately deal with the abundance of incoming products that harm flora and fauna. Plastic and other materials pollute the soil and the ocean, causing the disappearance of whole species and changing the behaviors of animals. There exists no sole answer to the problem of unethical tourism. Instead, individuals, companies, and governments should cooperate to develop a set of green policies that will raise awareness and allow people to take action to preserve the planet’s environment.

Carić, Hrvoje, and Peter Mackelworth. “Cruise Tourism Environmental Impacts–The Perspective from the Adriatic Sea.” Ocean & Coastal Management , vol.102, 2014, pp. 350-363.

Chiu, Yen-Ting Helena, et al. “Environmentally Responsible Behavior in Ecotourism: Antecedents and Implications.” Tourism Management , vol. 40, 2014, pp. 321-329.

Gavrilović, Zvjezdana, and Mirjana Maksimović. “Green Innovations in the Tourism Sector.” Strategic Management , vol. 23, no. 1, 2018, pp. 36-42.

Kapmeier, Florian, and Paulo Gonçalves. “Wasted Paradise? Policies for Small Island States to Manage Tourism-Driven Growth While Controlling Waste Generation: The Case of the Maldives.” System Dynamics Review , vol. 34, no. 1-2, 2018, pp. 172-221.

Klein, Laura, and Rachel Dodds. “Blue Flag Beach Certification: An Environmental Management Tool or Tourism Promotional Tool?” Tourism Recreation Research , vol. 43, no. 1, 2018, pp. 39-51.

Lamers, Machiel, et al. “The Environmental Challenges of Cruise Tourism.” The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability , edited by Daniel Scott et al., Routledge, 2015, pp. 430-439.

Mowforth, Martin, and Ian Munt. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World . 4th ed., Routledge, 2016.

Stefănica, Mirela, and Gina Ionela Butnaru. “Research on Tourists’ Perception of the Relationship Between Tourism and Environment.” Procedia Economics and Finance , vol. 20, 2015, pp. 595-600.

Wilson, Scott P., and Krista M. Verlis. “The Ugly Face of Tourism: Marine Debris Pollution Linked to Visitation in the Southern Great Barrier Reef, Australia.” Marine Pollution Bulletin , vol. 117, no. 1-2, 2017, pp. 239-246.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 14). Environmental Impacts of Tourism. https://ivypanda.com/essays/environmental-impacts-of-tourism/

"Environmental Impacts of Tourism." IvyPanda , 14 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/environmental-impacts-of-tourism/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Environmental Impacts of Tourism'. 14 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Environmental Impacts of Tourism." July 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/environmental-impacts-of-tourism/.

1. IvyPanda . "Environmental Impacts of Tourism." July 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/environmental-impacts-of-tourism/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Environmental Impacts of Tourism." July 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/environmental-impacts-of-tourism/.

- Tourism in Maldives and Seychelles

- A Company Analysis of Maldives Post Limited

- Country Analysis: The Maldives and Sri Lanka

- Educational Technology in Mmall State Countries: The Maldives

- Trends in Ecotourism

- Types of Tourism and Ecotourism in Peru

- Advantages and Setbacks of Political Movements

- Ecotourism Industry Organization

- Ecology of Coral Reefs Review

- Importance of Coral Reefs

- Communication and Philosophy Ideas in Tourism

- What Will the Tourist Be Doing in 2030?

- Tourism in Australia and Sustainability

- Cultural Differences in Tourism: Chinese and Western Tourists

- Travel Biases in China

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 07 May 2018

The carbon footprint of global tourism

- Manfred Lenzen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0828-5288 1 ,

- Ya-Yen Sun 2 , 3 ,

- Futu Faturay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5636-1794 1 , 4 ,

- Yuan-Peng Ting 2 ,

- Arne Geschke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9193-5829 1 &

- Arunima Malik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4630-9869 1 , 5

Nature Climate Change volume 8 , pages 522–528 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

800 Citations

3345 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Attribution

- Climate-change impacts

An Author Correction to this article was published on 23 May 2018

This article has been updated

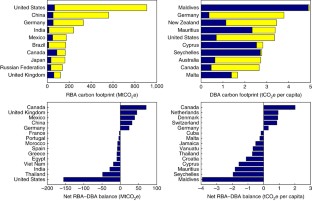

Tourism contributes significantly to global gross domestic product, and is forecast to grow at an annual 4%, thus outpacing many other economic sectors. However, global carbon emissions related to tourism are currently not well quantified. Here, we quantify tourism-related global carbon flows between 160 countries, and their carbon footprints under origin and destination accounting perspectives. We find that, between 2009 and 2013, tourism’s global carbon footprint has increased from 3.9 to 4.5 GtCO 2 e, four times more than previously estimated, accounting for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Transport, shopping and food are significant contributors. The majority of this footprint is exerted by and in high-income countries. The rapid increase in tourism demand is effectively outstripping the decarbonization of tourism-related technology. We project that, due to its high carbon intensity and continuing growth, tourism will constitute a growing part of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Studying tourism development and its impact on carbon emissions

Xiaochun Zhao, Taiwei Li & Xin Duan

Environmental and welfare gains via urban transport policy portfolios across 120 cities

Charlotte Liotta, Vincent Viguié & Felix Creutzig

Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions

Mengyu Li, Nanfei Jia, … David Raubenheimer

Change history

23 may 2018.

In the version of this Article originally published, in the penultimate paragraph of the section “Gas species and supply chains”, in the sentence “In this assessment, the contribution of air travel emissions amounts to 20% (0.9 GtCO2e) of tourism’s global carbon footprint...” the values should have read “12% (0.55 GtCO2e)”; this error has now been corrected, and Supplementary Table 9 has been amended to clarify this change.

Travel & Tourism: Economic Impact 2017 (World Travel & Tourism Council, 2017); https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/regions-2017/world2017.pdf

UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2016 Edition (World Tourism Organization, 2016); http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284418145

Gössling, S. Global environmental consequences of tourism. Glob. Environ. Change 12 , 283–302 (2002).

Google Scholar

Scott, D., Gössling, S. & Hall, C. M. International tourism and climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 3 , 213–232 (2012).

Puig, R. et al. Inventory analysis and carbon footprint of coastland-hotel services: a Spanish case study. Sci. Total Environ. 595 , 244–254 (2017).

CAS Google Scholar

El Hanandeh, A. Quantifying the carbon footprint of religious tourism: the case of Hajj. J. Clean. Prod. 52 , 53–60 (2013).

Pereira, R. P. T., Ribeiro, G. M. & Filimonau, V. The carbon footprint appraisal of local visitor travel in Brazil: a case of the Rio de Janeiro–São Paulo itinerary. J. Clean. Prod. 141 , 256–266 (2017).

Munday, M., Turner, K. & Jones, C. Accounting for the carbon associated with regional tourism consumption. Tour. Manag. 36 , 35–44 (2013).

Sun, Y.-Y. A framework to account for the tourism carbon footprint at island destinations. Tour. Manage. 45 , 16–27 (2014).

Cadarso, M. Á., Gómez, N., López, L. A. & Tobarra, M. A. Calculating tourism ’ s carbon footprint: measuring the impact of investments. J. Clean. Prod. 111 , 529–537 (2016).

Cadarso, M.-Á., Gómez, N., López, L.-A., TobarraM.-Á. & Zafrilla, J.-E. Quantifying Spanish tourism ’ s carbon footprint: the contributions of residents and visitors: a longitudinal study. J. Sustain. Tour. 23 , 922–946 (2015).

Becken, S. & Patterson, M. Measuring national carbon dioxide emissions from tourism as a key step towards achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 14 , 323–338 (2006).

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., Spurr, R. & Hoque, S. Estimating the carbon footprint of Australian tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 18 , 355–376 (2010).

Sharp, H., Grundius, J. & Heinonen, J. Carbon footprint of inbound tourism to Iceland: a consumption-based life-cycle assessment including direct and indirect emissions. Sustainability 8 , 1147 (2016).

Luo, F., Becken, S. & Zhong, Y. Changing travel patterns in China and ‘carbon footprint’ implications for a domestic tourist destination. Tour. Manag. 65 , 1–13 (2018).

Climate Change and Tourism—Responding to Global Challenges (World Tourist Organisation, United Nations Environment Programme, World Meteorological Organisation, 2008); http://sdt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/climate2008.pdf

Peeters, P. & Dubois, G. Tourism travel under climate change mitigation constraints. J. Transp. Geogr. 18 , 447–457 (2010).

Gössling, S. & Peeters, P. Assessing tourism ’ s global environmental impact 1900–2050. J. Sustain. Tour. 23 , 639–659 (2015).

Kander, A., Jiborn, M., Moran, D. D. & Wiedmann, T. O. National greenhouse-gas accounting for effective climate policy on international trade. Nat. Clim. Change 5 , 431–435 (2015).

ICAO Environmental Report 2016—Aviation and Climate Change (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2016).

Lee, D. S. et al. Transport impacts on atmosphere and climate: aviation. Atmos. Environ. 44 , 4678–4734 (2010).

Perch-Nielsen, S., Sesartic, A. & Stucki, M. The greenhouse gas intensity of the tourism sector: the case of Switzerland. Environ. Sci. Policy 13 , 131–140 (2010).

Peters, G., Minx, J., Weber, C. & Edenhofer, O. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108 , 8903–8908 (2011).

Malik, A., Lan, J. & Lenzen, M. Trends in global greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 to 2010. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 , 4722–4730 (2016).

GDP Per Capita, Current Prices (International Monetary Fund, 2017); http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

Annual Energy Outlook 2017 With Projections to 2050 (US Energy Information Administration, 2017); https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/0383(2017).pdf

OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050 (OECD Environment Directorate, PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 2011); https://www.oecd.org/env/cc/49082173.pdf

Wier, M., Lenzen, M., Munksgaard, J. & Smed, S. Effects of household consumption patterns on CO 2 requirements. Econ. Syst. Res. 13 , 259–274 (2001).

Lenzen, M. et al. A comparative multivariate analysis of household energy requirements in Australia, Brazil, Denmark, India and Japan. Energy 31 , 181–207 (2006).

Lenzen, M., Dey, C. & Foran, B. Energy requirements of Sydney households. Ecol. Econ. 49 , 375–399 (2004).

Garin-Munoz, T. & Amaral, T. P. An econometric model for international tourism flows to Spain. Appl. Econ. Lett. 7 , 525–529 (2000).

Lim, C., Min, J. C. H. & McAleer, M. Modelling income effects on long and short haul international travel from Japan. Tour. Manage. 29 , 1099–1109 (2008).

Song, H. & Wong, K. K. Tourism demand modeling: a time-varying parameter approach. J. Travel Res. 42 , 57–64 (2003).

Cohen, C. A. M. J., Lenzen, M. & Schaeffer, R. Energy requirements of households in Brazil. Energy Policy 55 , 555–562 (2005).

Mishra, S. S. & Bansal, V. Role of source–destination proximity in international inbound tourist arrival: empirical evidences from India. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 22 , 540–553 (2017).

Wong, I. A., Fong, L. H. N. & LawR. A longitudinal multilevel model of tourist outbound travel behavior and the dual-cycle model. J. Travel Res. 55 , 957–970 (2016).

Dubois, G. & Ceron, J. P. Tourism/leisure greenhouse gas emissions forecasts for 2050: factors for change in France. J. Sustain. Tour. 14 , 172–191 (2006).

Filimonau, V., Dickinson, J. & Robbins, D. The carbon impact of short-haul tourism: a case study of UK travel to southern France using life cycle analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 64 , 628–638 (2014).

Gössling, S., Scott, D. & Hall, C. M. Inter-market variability in CO 2 emission-intensities in tourism: implications for destination marketing and carbon management. Tour. Manage. 46 , 203–212 (2015).

Gössling, S. et al. The eco-efficiency of tourism. Ecol. Econ. 54 , 417–434 (2005).

Hatfield-Dodds, S. et al. Australia is ‘free to choose’ economic growth and falling environmental pressures. Nature 527 , 49–53 (2015).

Lenzen, M., Malik, A. & Foran, B. How challenging is decoupling for Australia?. J. Clean. Prod. 139 , 796–798 (2016).

Gössling., S. Sustainable tourism development in developing countries: some aspects of energy use. J. Sustain. Tour. 8 , 410–425 (2000).

Székely, T. Hungary plans ‘major touristic developments’ to double income from foreign tourism. Hungary Today (13 February 2017); http://hungarytoday.hu/news/hungary-plans-several-major-touristic-developments-double-income-foreign-tourism-45636

Nepal unveils plans to double tourist arrival. Nepal24Hours (12 December 2012); http://www.nepal24hours.com/nepal-unveils-plans-to-double-tourist-arrival

Murai, S. Japan doubles overseas tourist target for 2020. Japan Times (30 March 2016); https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/03/30/national/japan-doubles-overseas-tourist-target-2020/#.Wh_XplWWapo

McElroy, J. L. Small island tourist economies across the life cycle. Asia. Pac. Viewp. 47 , 61–77 (2006).

Lenzen, M. Sustainable island businesses: a case study of Norfolk Island. J. Clean. Prod. 16 , 2018–2035 (2008).

de Bruijn, K., Dirven, R., Eijgelaar, E. & Peeters, P. Travelling Large in 2013: The Carbon Footprint of Dutch Holidaymakers in 2013 and the Development Since 2002 (NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences, 2014).

Sun, Y. -Y. Decomposition of tourism greenhouse gas emissions: revealing the dynamics between tourism economic growth, technological efficiency, and carbon emissions. Tour. Manage. 55 , 326–336 (2016).

Wilkinson, P. F. Island tourism: sustainable perspectives. Ann. Tour. Res. 39 , 505–506 (2012).

Tourism Statistics (World Tourism Organization, 2017); http://www.e-unwto.org/loi/unwtotfb

Lenzen, M., Kanemoto, K., Moran, D. & Geschke, A. Mapping the structure of the world economy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 , 8374–8381 (2012).

Lenzen, M., Moran, D., Kanemoto, K. & Geschke, A. Building EORA: a global multi-region input–output database at high country and sector resolution. Econ. Syst. Res. 25 , 20–49 (2013).

Leontief, W. W. & Strout, A. A. in Structural Interdependence and Economic Development (ed. Barna, T.) 119–149 (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1963).

Oita, A. et al. Substantial nitrogen pollution embedded in international trade. Nat. Geosci. 9 , 111–115 (2016).

Feng, K., Davis, S. J., Sun, L. & Hubacek, K. Drivers of the US CO 2 emissions 1997–2013. Nat. Commun. 6 , 7714 (2015).

Steinberger, J. K., Roberts, J. T., Peters, G. P. & Baiocchi, G. Pathways of human development and carbon emissions embodied in trade. Nat. Clim. Change 2 , 81–85 (2012).

Lenzen, M. et al. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature 486 , 109–112 (2012).

Lin, J. et al. Global climate forcing of aerosols embodied in international trade. Nat. Geosci. 9 , 790 (2016).

Dalin, C., Wada, Y., Kastner, T. & Puma, M. J. Groundwater depletion embedded in international food trade. Nature 543 , 700 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. Transboundary health impacts of transported global air pollution and international trade. Nature 543 , 705 (2017).

Travel & Tourism: Economic Impact Research Methodology (World Travel & Tourism Council, Oxford Economics, 2017); https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/2017-documents/2017_methodology-final.pdf

Leontief, W. Input–Output Economics (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1966).

Dixon, R. Inter-industry transactions and input–output analysis. Aust. Econ. Rev. 3 , 327–336 (1996).

Munksgaard, J. & Pedersen, K. A. CO 2 accounts for open economies: producer or consumer responsibility? Energy Policy 29 , 327–334 (2001).

Kanemoto, K. & Murray, J. in The Sustainability Practitioner’s Guide to Input–Output Analysis (eds Murray, J. & Wood, R.) 167–178 (Common Ground, Champaign, 2010).

Kanemoto, K., Lenzen, M., Peters, G. P., Moran, D. & Geschke, A. Frameworks for comparing emissions associated with production, consumption and International trade. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 , 172–179 (2012).

Waugh, F. V. Inversion of the Leontief matrix by power series. Econometrica 18 , 142–154 (1950).

Lenzen, M. et al. The Global MRIO Lab—charting the world economy. Econ. Syst. Res. 29 , 158–186 (2017).

Systems of National Accounts (International Monetary Fund, Commission of the European Communities-Euro-Stat, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, World Bank, United Nations, 1993).

TSA Data Around the World: Worldwide Summary (World Tourism Organization, 2010).

Tourism Statistics 2009–2013 (World Tourism Organization, 2009–2013).

Chasapopoulos, P., den Butter, F. A. & Mihaylov, E. Demand for tourism in Greece: a panel data analysis using the gravity model. Int. J. Tour. Policy 5 , 173–191 (2014).

Morley, C., Rosselló, J. & Santana-Gallego, M. Gravity models for tourism demand: theory and use. Ann. Tour. Res. 48 , 1–10 (2014).

Lloyd, S. M. & Ries, R. Characterizing, propagating, and analyzing uncertainty in life-cycle assessment: a survey of quantitative approaches. J. Indust. Ecol. 11 , 161–179 (2007).

Imbeault-Tétreault, H., Jolliet, O., Deschênes, L. & Rosenbaum, R. K. Analytical propagation of uncertainty in life cycle assessment using matrix formulation. J. Indust. Ecol. 17 , 485–492 (2013).

Lenzen, M. Aggregation versus disaggregation in input-output analysis of the environment. Econ. Syst. Res 23 , 73–89 (2011).

Bullard, C. W. & Sebald, A. V. Effects of parametric uncertainty and technological change on input-output models. Rev. Econ. Stat. 59 , 75–81 (1977).

Bullard, C. W. & Sebald, A. V. Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis of input-output models. Rev. Econ. Stat. 70 , 708–712 (1988).

Nansai, K., Tohno, S. & Kasahara, M. Uncertainty of the embodied CO2 emission intensity and reliability of life cycle inventory analysis by input-output approach (in Japanese). Energy Resour . 22 , (2001).

Yoshida, Y. et al. Reliability of LCI considering the uncertainties of energy consumptions in input-output analyses. Appl. Energy 73 , 71–82 (2002).

Lenzen, M., Wood, R. & Wiedmann, T. Uncertainty analysis for multi-region input-output models — a case study of the UK’s carbon footprint. Econ. Syst. Res 22 , 43–63 (2010).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Australian Research Council through its Discovery Projects DP0985522 and DP130101293, the National eResearch Collaboration Tools and Resources project (NeCTAR) through its Industrial Ecology Virtual Laboratory, and the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (no. 105-2410-H-006-055-MY3). The authors thank S. Juraszek for expertly managing the Global IELab’s advanced computation requirements, and C. Jarabak for help with collecting data.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

ISA, School of Physics A28, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Manfred Lenzen, Futu Faturay, Arne Geschke & Arunima Malik

Department of Transportation & Communication Management Science, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City, Taiwan, Republic of China

Ya-Yen Sun & Yuan-Peng Ting

UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Fiscal Policy Agency, Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

Futu Faturay

Sydney Business School, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Arunima Malik

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Y.-Y.S. and M.L. conceived and designed the experiments. M.L., Y.-Y.S., F.F., Y.-P.T., A.G. and A.M. performed the experiments. F.F., Y.-P.T., M.L. and Y.-Y.S. analysed the data. Y.-P.T., A.G., Y.-Y.S. and M.L. contributed materials/analysis tools. M.L., Y.-Y.S. and A.M. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Arunima Malik .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Notes, Supplementary Data, Supplementary Results, Supplementary Figures 1–13, Supplementary Tables 1–14, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lenzen, M., Sun, YY., Faturay, F. et al. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Clim Change 8 , 522–528 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Download citation

Received : 05 December 2017

Accepted : 20 March 2018

Published : 07 May 2018

Issue Date : June 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Assessment of low-carbon tourism development from multi-aspect analysis: a case study of the yellow river basin, china.

- Xiaopeng Si

Scientific Reports (2024)

Advancing towards carbon-neutral events

- Danyang Cheng

Nature Climate Change (2024)

“Long COVID” and Its Impact on The Environment: Emerging Concerns and Perspectives

- Shilpa Patial

- Pankaj Raizada

Environmental Management (2024)

Assessing the socio-economic impacts of tourism packages: a methodological proposition

- Cristina Casals Miralles

- Mercè Boy Roura

- Joan Colón Jordà

The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment (2024)

Green finance, renewable energy, and inbound tourism: a case study of 30 provinces in China

- Lingrou Zhu

- Yunfeng Shang

- Fangbin Qian

Economic Change and Restructuring (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

What Is Sustainable Tourism and Why Is It Important?

Sustainable management and socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental impacts are the four pillars of sustainable tourism

- Chapman University

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/HaleyMast-2035b42e12d14d4abd433e014e63276c.jpg)

- Harvard University Extension School

- Sustainable Fashion

- Art & Media

What Makes Tourism Sustainable?

The role of tourists, types of sustainable tourism.

Sustainable tourism considers its current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts by addressing the needs of its ecological surroundings and the local communities. This is achieved by protecting natural environments and wildlife when developing and managing tourism activities, providing only authentic experiences for tourists that don’t appropriate or misrepresent local heritage and culture, or creating direct socioeconomic benefits for local communities through training and employment.

As people begin to pay more attention to sustainability and the direct and indirect effects of their actions, travel destinations and organizations are following suit. For example, the New Zealand Tourism Sustainability Commitment is aiming to see every New Zealand tourism business committed to sustainability by 2025, while the island country of Palau has required visitors to sign an eco pledge upon entry since 2017.

Tourism industries are considered successfully sustainable when they can meet the needs of travelers while having a low impact on natural resources and generating long-term employment for locals. By creating positive experiences for local people, travelers, and the industry itself, properly managed sustainable tourism can meet the needs of the present without compromising the future.

What Is Sustainability?

At its core, sustainability focuses on balance — maintaining our environmental, social, and economic benefits without using up the resources that future generations will need to thrive. In the past, sustainability ideals tended to lean towards business, though more modern definitions of sustainability highlight finding ways to avoid depleting natural resources in order to keep an ecological balance and maintain the quality of environmental and human societies.

Since tourism impacts and is impacted by a wide range of different activities and industries, all sectors and stakeholders (tourists, governments, host communities, tourism businesses) need to collaborate on sustainable tourism in order for it to be successful.

The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) , which is the United Nations agency responsible for the promotion of sustainable tourism, and the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) , the global standard for sustainable travel and tourism, have similar opinions on what makes tourism sustainable. By their account, sustainable tourism should make the best use of environmental resources while helping to conserve natural heritage and biodiversity, respect the socio-culture of local host communities, and contribute to intercultural understanding. Economically, it should also ensure viable long-term operations that will provide benefits to all stakeholders, whether that includes stable employment to locals, social services, or contributions to poverty alleviation.

The GSTC has developed a series of criteria to create a common language about sustainable travel and tourism. These criteria are used to distinguish sustainable destinations and organizations, but can also help create sustainable policies for businesses and government agencies. Arranged in four pillars, the global baseline standards include sustainable management, socioeconomic impact, cultural impacts, and environmental impacts.

Travel Tip:

The GSTC is an excellent resource for travelers who want to find sustainably managed destinations and accommodations and learn how to become a more sustainable traveler in general.

Environment

Protecting natural environments is the bedrock of sustainable tourism. Data released by the World Tourism Organization estimates that tourism-based CO2 emissions are forecast to increase 25% by 2030. In 2016, tourism transport-related emissions contributed to 5% of all man-made emissions, while transport-related emissions from long-haul international travel were expected to grow 45% by 2030.

The environmental ramifications of tourism don’t end with carbon emissions, either. Unsustainably managed tourism can create waste problems, lead to land loss or soil erosion, increase natural habitat loss, and put pressure on endangered species . More often than not, the resources in these places are already scarce, and sadly, the negative effects can contribute to the destruction of the very environment on which the industry depends.

Industries and destinations that want to be sustainable must do their part to conserve resources, reduce pollution, and conserve biodiversity and important ecosystems. In order to achieve this, proper resource management and management of waste and emissions is important. In Bali, for example, tourism consumes 65% of local water resources, while in Zanzibar, tourists use 15 times as much water per night as local residents.

Another factor to environmentally focused sustainable tourism comes in the form of purchasing: Does the tour operator, hotel, or restaurant favor locally sourced suppliers and products? How do they manage their food waste and dispose of goods? Something as simple as offering paper straws instead of plastic ones can make a huge dent in an organization’s harmful pollutant footprint.

Recently, there has been an uptick in companies that promote carbon offsetting . The idea behind carbon offsetting is to compensate for generated greenhouse gas emissions by canceling out emissions somewhere else. Much like the idea that reducing or reusing should be considered first before recycling , carbon offsetting shouldn’t be the primary goal. Sustainable tourism industries always work towards reducing emissions first and offset what they can’t.

Properly managed sustainable tourism also has the power to provide alternatives to need-based professions and behaviors like poaching . Often, and especially in underdeveloped countries, residents turn to environmentally harmful practices due to poverty and other social issues. At Periyar Tiger Reserve in India, for example, an unregulated increase in tourists made it more difficult to control poaching in the area. In response, an eco development program aimed at providing employment for locals turned 85 former poachers into reserve gamekeepers. Under supervision of the reserve’s management staff, the group of gamekeepers have developed a series of tourism packages and are now protecting land instead of exploiting it. They’ve found that jobs in responsible wildlife tourism are more rewarding and lucrative than illegal work.

Flying nonstop and spending more time in a single destination can help save CO2, since planes use more fuel the more times they take off.

Local Culture and Residents

One of the most important and overlooked aspects of sustainable tourism is contributing to protecting, preserving, and enhancing local sites and traditions. These include areas of historical, archaeological, or cultural significance, but also "intangible heritage," such as ceremonial dance or traditional art techniques.

In cases where a site is being used as a tourist attraction, it is important that the tourism doesn’t impede access to local residents. For example, some tourist organizations create local programs that offer residents the chance to visit tourism sites with cultural value in their own countries. A program called “Children in the Wilderness” run by Wilderness Safaris educates children in rural Africa about the importance of wildlife conservation and valuable leadership development tools. Vacations booked through travel site Responsible Travel contribute to the company’s “Trip for a Trip” program, which organizes day trips for disadvantaged youth who live near popular tourist destinations but have never had the opportunity to visit.

Sustainable tourism bodies work alongside communities to incorporate various local cultural expressions as part of a traveler’s experiences and ensure that they are appropriately represented. They collaborate with locals and seek their input on culturally appropriate interpretation of sites, and train guides to give visitors a valuable (and correct) impression of the site. The key is to inspire travelers to want to protect the area because they understand its significance.

Bhutan, a small landlocked country in South Asia, has enforced a system of all-inclusive tax for international visitors since 1997 ($200 per day in the off season and $250 per day in the high season). This way, the government is able to restrict the tourism market to local entrepreneurs exclusively and restrict tourism to specific regions, ensuring that the country’s most precious natural resources won’t be exploited.

Incorporating volunteer work into your vacation is an amazing way to learn more about the local culture and help contribute to your host community at the same time. You can also book a trip that is focused primarily on volunteer work through a locally run charity or non profit (just be sure that the job isn’t taking employment opportunities away from residents).

It's not difficult to make a business case for sustainable tourism, especially if one looks at a destination as a product. Think of protecting a destination, cultural landmark, or ecosystem as an investment. By keeping the environment healthy and the locals happy, sustainable tourism will maximize the efficiency of business resources. This is especially true in places where locals are more likely to voice their concerns if they feel like the industry is treating visitors better than residents.

Not only does reducing reliance on natural resources help save money in the long run, studies have shown that modern travelers are likely to participate in environmentally friendly tourism. In 2019, Booking.com found that 73% of travelers preferred an eco-sustainable hotel over a traditional one and 72% of travelers believed that people need to make sustainable travel choices for the sake of future generations.

Always be mindful of where your souvenirs are coming from and whether or not the money is going directly towards the local economy. For example, opt for handcrafted souvenirs made by local artisans.

Growth in the travel and tourism sectors alone has outpaced the overall global economy growth for nine years in a row. Prior to the pandemic, travel and tourism accounted for an $9.6 trillion contribution to the global GDP and 333 million jobs (or one in four new jobs around the world).

Sustainable travel dollars help support employees, who in turn pay taxes that contribute to their local economy. If those employees are not paid a fair wage or aren’t treated fairly, the traveler is unknowingly supporting damaging or unsustainable practices that do nothing to contribute to the future of the community. Similarly, if a hotel doesn’t take into account its ecological footprint, it may be building infrastructure on animal nesting grounds or contributing to excessive pollution. The same goes for attractions, since sustainably managed spots (like nature preserves) often put profits towards conservation and research.

Costa Rica was able to turn a severe deforestation crisis in the 1980s into a diversified tourism-based economy by designating 25.56% of land protected as either a national park, wildlife refuge, or reserve.

While traveling, think of how you would want your home country or home town to be treated by visitors.

Are You a Sustainable Traveler?

Sustainable travelers understand that their actions create an ecological and social footprint on the places they visit. Be mindful of the destinations , accommodations, and activities you choose, and choose destinations that are closer to home or extend your length of stay to save resources. Consider switching to more environmentally friendly modes of transportation such as bicycles, trains, or walking while on vacation. Look into supporting locally run tour operations or local family-owned businesses rather than large international chains. Don’t engage in activities that harm wildlife, such as elephant riding or tiger petting , and opt instead for a wildlife sanctuary (or better yet, attend a beach clean up or plan an hour or two of some volunteer work that interests you). Leave natural areas as you found them by taking out what you carry in, not littering, and respecting the local residents and their traditions.

Most of us travel to experience the world. New cultures, new traditions, new sights and smells and tastes are what makes traveling so rewarding. It is our responsibility as travelers to ensure that these destinations are protected not only for the sake of the communities who rely upon them, but for a future generation of travelers.

Sustainable tourism has many different layers, most of which oppose the more traditional forms of mass tourism that are more likely to lead to environmental damage, loss of culture, pollution, negative economic impacts, and overtourism.

Ecotourism highlights responsible travel to natural areas that focus on environmental conservation. A sustainable tourism body supports and contributes to biodiversity conservation by managing its own property responsibly and respecting or enhancing nearby natural protected areas (or areas of high biological value). Most of the time, this looks like a financial compensation to conservation management, but it can also include making sure that tours, attractions, and infrastructure don’t disturb natural ecosystems.

On the same page, wildlife interactions with free roaming wildlife should be non-invasive and managed responsibly to avoid negative impacts to the animals. As a traveler, prioritize visits to accredited rescue and rehabilitation centers that focus on treating, rehoming, or releasing animals back into the wild, such as the Jaguar Rescue Center in Costa Rica.

Soft Tourism

Soft tourism may highlight local experiences, local languages, or encourage longer time spent in individual areas. This is opposed to hard tourism featuring short duration of visits, travel without respecting culture, taking lots of selfies , and generally feeling a sense of superiority as a tourist.

Many World Heritage Sites, for example, pay special attention to protection, preservation, and sustainability by promoting soft tourism. Peru’s famed Machu Picchu was previously known as one of the world’s worst victims of overtourism , or a place of interest that has experienced negative effects (such as traffic or litter) from excessive numbers of tourists. The attraction has taken steps to control damages in recent years, requiring hikers to hire local guides on the Inca Trail, specifying dates and time on visitor tickets to negate overcrowding, and banning all single use plastics from the site.

Traveling during a destination’s shoulder season , the period between the peak and low seasons, typically combines good weather and low prices without the large crowds. This allows better opportunities to immerse yourself in a new place without contributing to overtourism, but also provides the local economy with income during a normally slow season.

Rural Tourism

Rural tourism applies to tourism that takes place in non-urbanized areas such as national parks, forests, nature reserves, and mountain areas. This can mean anything from camping and glamping to hiking and WOOFing. Rural tourism is a great way to practice sustainable tourism, since it usually requires less use of natural resources.

Community Tourism

Community-based tourism involves tourism where local residents invite travelers to visit their own communities. It sometimes includes overnight stays and often takes place in rural or underdeveloped countries. This type of tourism fosters connection and enables tourists to gain an in-depth knowledge of local habitats, wildlife, and traditional cultures — all while providing direct economic benefits to the host communities. Ecuador is a world leader in community tourism, offering unique accommodation options like the Sani Lodge run by the local Kichwa indigenous community, which offers responsible cultural experiences in the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest.

" Transport-related CO 2 Emissions of the Tourism Sector – Modelling Results ." World Tourism Organization and International Transport Forum , 2019, doi:10.18111/9789284416660

" 45 Arrivals Every Second ." The World Counts.

Becken, Susanne. " Water Equity- Contrasting Tourism Water Use With That of the Local Community ." Water Resources and Industry , vol. 7-8, 2014, pp. 9-22, doi:10.1016/j.wri.2014.09.002

Kutty, Govindan M., and T.K. Raghavan Nair. " Periyar Tiger Reserve: Poachers Turned Gamekeepers ." Food and Agriculture Organization.

" GSTC Destination Criteria ." Global Sustainable Tourism Council.

Rinzin, Chhewang, et al. " Ecotourism as a Mechanism for Sustainable Development: the Case of Bhutan ." Environmental Sciences , vol. 4, no. 2, 2007, pp. 109-125, doi:10.1080/15693430701365420

" Booking.com Reveals Key Findings From Its 2019 Sustainable Travel Report ." Booking.com.

" Economic Impact Reports ." World Travel and Tourism Council .

- Regenerative Travel: What It Is and How It's Outperforming Sustainable Tourism