JMP ® Education

Getting started, jmp ® : a case study approach to data exploration.

This course is designed as the first step for those who want to use JMP to explore, manage, and analyze data. It is recommended as a prerequisite for many of our other courses.

The course begins with an introduction to the JMP interface with its key tools and features, followed by two case studies that present common data issues that students encounter. Each case study demonstrates the elements of a typical workflow for data exploration. This course will help you prepare to use JMP in more advanced courses covering statistical analysis and modeling, design of experiments and quality control, or the JMP Scripting Language.

Duration: 2 half-day sessions ( Feb. 6-9 four two-hour sessions )

Registration Fee: $200 US

- Prerequisites

- Course Outline

Learn how to:

- Import data into JMP.

- Explore the data with graphs and tables.

- Identify and correct data problems.

- Create new columns with formulas.

- Save and share graphical and numerical reports.

No previous JMP knowledge or statistical knowledge is required. Before attending this course, you should be familiar with a macOS or Microsoft Windows operating system.

Introduction

- Introduction to JMP.

- Exploring data.

Process Change Case Study

- Importing data.

- Creating new columns.

- Presenting and sharing results.

Process Monitoring Case Study

- Generating and saving results.

Manufacturing Case Study (Self-Study)

- Creating new tables and columns.

Course Dates

This course is not available at this time. Please check back at a later date.

Don’t see a course you want listed on the dates that you need? Contact us at [email protected] .

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

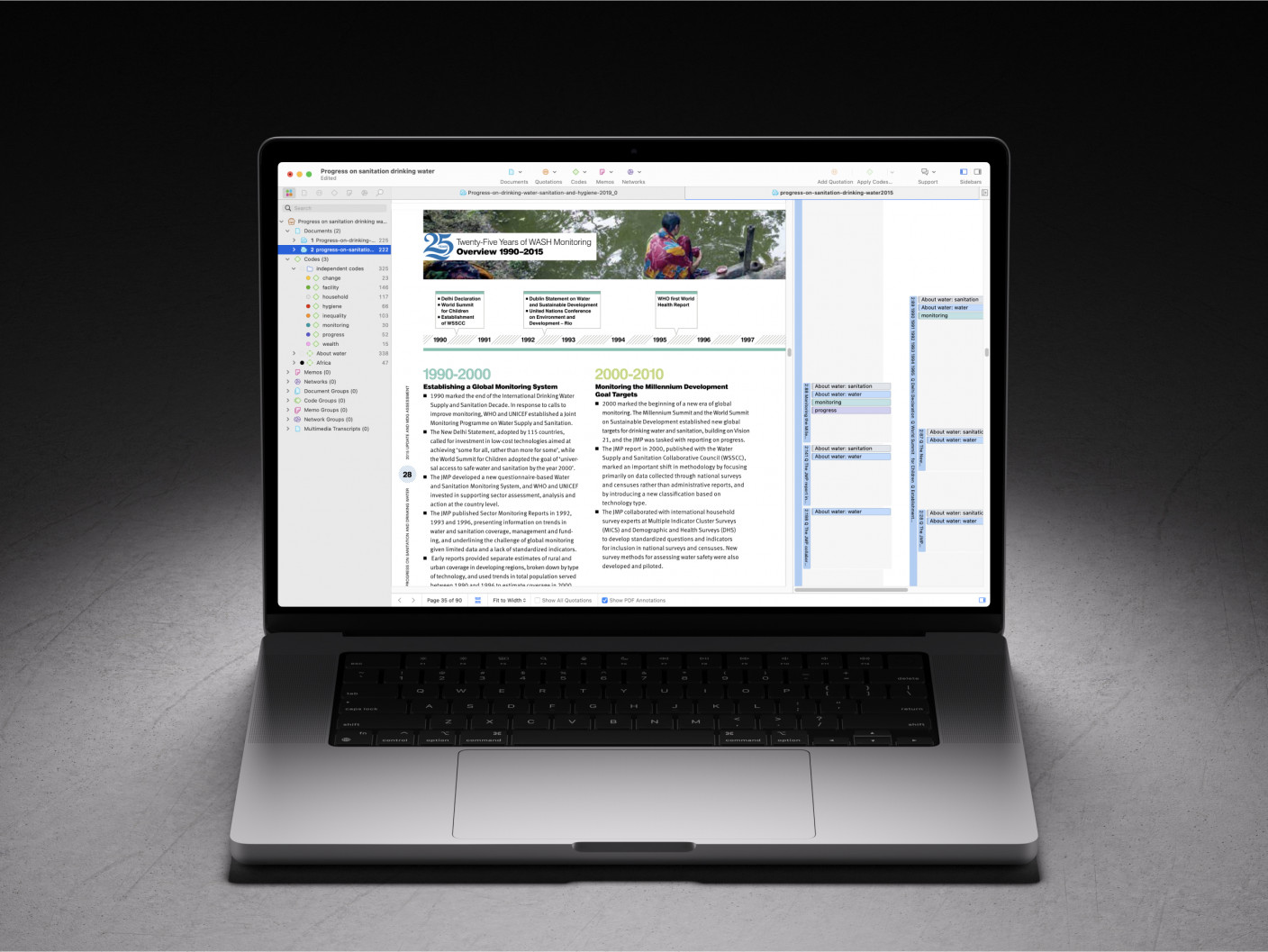

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

22 Case Study Research: In-Depth Understanding in Context

Helen Simons, School of Education, University of Southampton

- Published: 01 July 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter explores case study as a major approach to research and evaluation. After first noting various contexts in which case studies are commonly used, the chapter focuses on case study research directly Strengths and potential problematic issues are outlined and then key phases of the process. The chapter emphasizes how important it is to design the case, to collect and interpret data in ways that highlight the qualitative, to have an ethical practice that values multiple perspectives and political interests, and to report creatively to facilitate use in policy making and practice. Finally, it explores how to generalize from the single case. Concluding questions center on the need to think more imaginatively about design and the range of methods and forms of reporting requiredto persuade audiences to value qualitative ways of knowing in case study research.

Introduction

This chapter explores case study as a major approach to research and evaluation using primarily qualitative methods, as well as documentary sources, contemporaneous or historical. However, this is not the only way in which case study can be conceived. No one has a monopoly on the term. While sharing a focus on the singular in a particular context, case study has a wide variety of uses, not all associated with research. A case study, in common parlance, documents a particular situation or event in detail in a specific sociopolitical context. The particular can be a person, a classroom, an institution, a program, or a policy. Below I identify different ways in which case study is used before focusing on qualitative case study research in particular. However, first I wish to indicate how I came to advocate and practice this form of research. Origins, context, and opportunity often shape the research processes we endorse. It is helpful for the reader, I think, to know how I came to the perspective I hold.

The Beginnings

I first came to appreciate and enjoy the virtues of case study research when I entered the field of curriculum evaluation and research in the 1970s. The dominant research paradigm for educational research at that time was experimental or quasi- experimental, cost-benefit, or systems analysis, and the dominant curriculum model was aims and objectives ( House, 1993 ). The field was dominated, in effect, by a psychometric view of research in which quantitative methods were preeminent. But the innovative projects we were asked to evaluate (predominantly, but not exclusively, in the humanities) were not amenable to such methodologies. The projects were challenging to the status quo of institutions, involved people interpreting the policy and programs, were implemented differently in different contexts and regions, and had many unexpected effects.

We had no choice but to seek other ways to evaluate these complex programs, and case study was the methodology we found ourselves exploring, in order to understand how the projects were being implemented, why they had positive effects in some regions of the country and not others, and what the outcomes meant in different sociopolitical and cultural contexts. What better way to do this than to talk with people to see how they interpreted the “new” curriculum; to watch how teachers and students put it into practice; to document transactions, outcomes, and unexpected consequences; and to interpret all in the specific context of the case ( Simons, 1971 , 1987 , pp. 55–89). From this point on and in further studies, case study in educational research and evaluation came to be a major methodology for understanding complex educational and social programs. It also extended to other practice professions, such as nursing, health, and social care ( Zucker, 2001 ; Greenhalgh & Worrall, 1997 ; Shaw & Gould, 2001 ). For further details of the evolution of the case study approach and qualitative methodologies in evaluation, see House, 1993 , pp. 2–3; Greene, 2000 ; Simons, 2009 , pp. 14–18; Simons & McCormack, 2007 , pp. 292–311).

This was not exactly the beginning of case study, of course. It has a long history in many disciplines ( Simons, 1980; Ragin, 1992; Gomm, Hammersley, & Foster, 2004 ; Platt, 2007 ), many aspects of which form part of case study practice to this day. But its evolution in the context just described was a major move in the contemporary evolution of the logic of evaluative inquiry ( House, 1980 ). It also coincided with movement toward the qualitative in other disciplines, such as sociology and psychology. This was all part of what Denzin & Lincoln (1994) termed “a quiet methodological revolution” (p. ix) in qualitative inquiry that had been evolving over the course of forty years.

There is a further reason why I continue to advocate and practice case study research and evaluation to this day and that is my personal predilection for trying to understand and represent complexity, for puzzling through the ambiguities that exist in many contexts and programs and for presenting and negotiating different values and interests in fair and just ways.

Put more simply, I like interacting with people, listening to their stories, trials and tribulations—giving them a voice in understanding the contexts and projects with which they are involved, and finding ways to share these with a range of audiences. In other words, the move toward case study methodology described here suited my preference for how I learn.

Concepts and Purposes of Case Study

Before exploring case study as it has come to be established in educational research and evaluation over the past forty years, I wish to acknowledge other uses of case study. More often than not, these relate to purpose, and appropriately so in their different contexts, but many do not have a research intention. For a study to count as research, it would need to be a systematic investigation generating evidence that leads to “new” knowledge that is made public and open to scrutiny. There are many ways to conduct research stemming from different traditions and disciplines, but they all, in different ways, involve these characteristics.

Everyday Usage: Stories We Tell

The most common of these uses of case study is the everyday reference to a person, an anecdote or story illustrative of a particular incident, event, or experience of that person. It is often a short, reported account commonly seen in journalism but also in books exploring a phenomenon, such as recovery from serious accidents or tragedies, where the author chooses to illustrate the story or argument with a “lived” example. This is sometimes written by the author and sometimes by the person whose tale it is. “Let me share with you a story,” is a phrase frequently heard

The spirit behind this common usage and its power to connect can be seen in a report by Tim Adams of the London Olympics opening ceremony’s dramatization by Danny Boyle.

It was the point when we suddenly collectively wised up to the idea that what we are about to receive over the next two weeks was not only about “legacy collateral” and “targeted deliverables,” not about G4S failings and traffic lanes and branding opportunities, but about the second-by-second possibilities of human endeavour and spirit and communality, enacted in multiple places and all at the same time. Stories in other words. ( Adams, 2012 )

This was a collective story, of course, not an individual one, but it does convey some of the major characteristics of case study—that richness of detail, time, place, multiple happenings and experiences—that are also manifest in case study research, although carefully evidenced in the latter instance. We can see from this common usage how people have come to associate case study with story. I return to this thread in the reporting section.

Professions Individual Cases

In professional settings, in health and social care, case studies, often called case histories , are used to accurately record a person’s health or social care history and his or her current symptoms, experience, and treatment. These case histories include facts but also judgments and observations about the person’s reaction to situations or medication. Usually these are confidential. Not dissimilar is the detailed documentation of a case in law, often termed a case precedent when referred to in a court case to support an argument being made. However in law there is a difference in that such case precedents are publicly documented.

Case Studies in Teaching

Exemplars of practice.

In education, but also in health and social care training contexts, case studies have long been used as exemplars of practice. These are brief descriptions with some detail of a person or project’s experience in an area of practice. Though frequently reported accounts, they are based on a person’s experience and sometimes on previous research.

Case scenarios

Management studies are a further context in which case studies are often used. Here, the case is more like a scenario outlining a particular problem situation for the management student to resolve. These scenarios may be based on research but frequently are hypothetical situations used to raise issues for discussion and resolution. What distinguishes these case scenarios and the case exemplars in education from case study research is the intention to use them for teaching purposes.

Country Case Studies

Then there are case studies of programs, projects, and even countries, as in international development, where a whole-country study might be termed a case study or, in the context of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), where an exploration is conducted of the state of the art of a subject, such as education or environmental science in one or several countries. This may be a contemporaneous study and/or what transpired in a program over a period of time. Such studies often do have a research base but frequently are reported accounts that do not detail the design, methodology, and analysis of the case, as a research case study would do, or report in ways that give readers a vicarious experience of what it was like to be there. Such case studies tend to be more knowledge and information-focused than experiential.

Case Study as History

Closer to a research context is case study as history—what transpired at a certain time in a certain place. This is likely to be supported by documentary evidence but not primary data gathering unless it is an oral history. In education, in the late 1970s, Stenhouse (1978) experimented with a case study archive. Using contemporaneous data gathering, primarily through interviewing, he envisaged this database, which he termed a “case record,” forming an archive from which different individuals,, at some later date, could write a “case study.” This approach uses case study as a documentary source to begin to generate a history of education, as the subtitle of Stenhouse’s 1978 paper indicates “Towards a contemporary history of education.”

Case Study Research

From here on, my focus is on case study research per se, adopting for this purpose the following definition:

Case study is an in-depth exploration from multiple perspectives of the complexity and uniqueness of a particular project, policy, institution or system in a “real-life” context. It is research based, inclusive of different methods and is evidence-led. ( Simons, 2009 , p. 21).

For further related definitions of case study, see Stake (1995) , Merriam (1998), and Chadderton & Torrance (2011) . And for definitions from a slightly different perspective, see Yin (2004) and Thomas (2011a) .

Not Defined by Method or Perspective

The inclusion of different methods in the definition quoted above definition signals that case study research is not defined by methodology or method. What defines case study is its singularity and the concept and boundary of the case. It is theoretically possible to conduct a case study using primarily quantitative data if this is the best way of providing evidence to inform the issues the case is exploring. It is equally possible to conduct case study that is mainly qualitative, to engage people with the experience of the case or to provide a rich portrayal of an event, project, or program.

Or one can design the case using mixed methods. This increases the options for learning from different ways of knowing and is sometimes preferred by stakeholders who believe it provides a firmer basis for informing policy. This is not necessarily the case but is beyond the scope of this chapter to explore. For further discussion of the complexities of mixing methods and the virtue of using qualitative methods and case study in a mixed method design, see Greene (2007) .

Case study research may also be conducted from different standpoints—realist, interpretivist, or constructivist, for example. My perspective falls within a constructivist, interpretivist framework. What interests me is how I and those in the case perceive and interpret what we find and how we construct or co-construct understandings of the case. This not only suits my predilection for how I see the world, but also my preferred phenomenological approach to interviewing and curiosity about people and how they act in social and professional life.

Qualitative Case Study Research

Qualitative case study research shares many characteristics with other forms of qualitative research, such as narrative, oral history, life history, ethnography, in-depth interview, and observational studies that utilize qualitative methods. However, its focus, purpose, and origins, in educational research at least, are a little different.

The focus is clearly the study of the singular. The purpose is to portray an in-depth view of the quality and complexity of social/educational programs or policies as they are implemented in specific sociopolitical contexts. What makes it qualitative is its emphasis on subjective ways of knowing, particularly the experiential, practical, and presentational rather than the propositional ( Heron, 1992 , 1999 ) to comprehend and communicate what transpired in the case.

Characteristic Features and Advantages

Case study research is not method dependent, as noted earlier, nor is it constrained by resources or time. Although it can be conducted over several years, which provides an opportunity to explore the process of change and explain how and why things happened, it can equally be carried out contemporaneously in a few days, weeks, or months. This flexibility is extremely useful in many contexts, particularly when a change in policy or unforeseen issues in the field require modifying the design.

Flexibility extends to reporting. The case can be written up in different lengths and forms to meet different audience needs and to maximize use (see the section on Reporting). Using the natural language of participants and familiar methods (like interview, observation, oral history) also enables participants to engage in the research process, thereby contributing significantly to the generation of knowledge of the case. As I have indicated elsewhere ( Simons, 2009 ), “This is both a political and epistemological point. It signals a potential shift in the power base of who controls knowledge and recognizes the importance of co-constructing perceived reality through the relationships and joint understandings we create in the field” (p. 23).

Possible Disadvantages

If one is an advocate, identifying advantages of a research approach is easier than pointing out its disadvantages, something detractors are quite keen to do anyway! But no approach is perfect, and here are some of the issues that often trouble people about case study research. The “sample of one” is an obvious issue that worries those convinced that only large samples can constitute valid research and especially if this is to inform policy. Understanding complexity in depth may not be a sufficient counterargument, and I suspect there is little point in trying to persuade otherwise For frequently, this perception is one of epistemological and methodological, if not ideological, preference.

However, there are some genuine concerns that many case researchers face: the difficulty of processing a mass of data; of “telling the truth” in contexts where people may be identifiable; personal involvement, when the researcher is the main instrument of data gathering; and writing reports that are data-based, yet readable in style and length. But one issue that concerns advocates and nonadvocates alike is how inferences are drawn from the single case.

Answers to some of these issues are covered in the sections that follow. Whether they convince may again be a question of preference. However, it is worth noting here that I do not think we should seek to justify these concerns in terms identified by other methodologies. Many of them are intrinsic to the nature and strength of qualitative case study research.

Subjectivity, for instance, both of participants and researcher is inevitable, as it is in many other qualitative methodologies. This is often the basis on which we act. Rather than see this as bias or something to counter, it is an intelligence that is essential to understanding and interpreting the experience of participants and stakeholders. Such subjectivity needs to be disciplined, of course, through procedures that examine both the validity of individuals’ representations of “their truth”, and demonstrate how the researcher took a reflexive approach to monitoring how his or her own values and predilections may have unduly influenced the data.

Types of Case Study

There are numerous types of case study, too many to categorize, I think, as there are overlaps between them. However, attempts have been made to do this and, for those who value typologies, I refer them to Bassey (1999) and, for a more extended typology, to Thomas (2011b) . A slightly different approach is taken by Gomm, Hammersley, and Foster (2004) in annotating the different emphases in major texts on case study. What I prefer to do here is to highlight a few familiar types to focus the discussion that follows on the practice of case study research.

Stake (1995) offers a threefold distinction that is helpful when it comes to practice, he says, because it influences the methods we choose to gather data (p. 4). He distinguishes between an intrinsic case study , one that is studied to learn about the particular case itself and an instrumental case study , in which we choose a case to gain insight into a particular issue (i.e., the case is instrumental to understanding something else; p. 3). The collective case study is what its name suggests: an extension of the instrumental to several cases.

Theory-led or theory-generated case study is similarly self-explanatory, the first starting from a specific theory that is tested through the case; the second constructing a theory through interpretation of data generated in the case. In other words, one ends rather than begins with a theory. In qualitative case study research, this is the more familiar route. The theory of the case becomes the argument or story you will tell.

Evaluation case study requires a slightly longer description as this is my context of practice, one which has influenced the way I conduct case study and what I choose to emphasize in this chapter. An evaluation case study has three essential features: to determine the value of the case, to include and balance different interests and values, and to report findings to a range of stakeholders in ways that they can use. The reasons for this may be found in the interlude that follows, which offers a brief characterization of the social and ethical practice of evaluation and why qualitative methods are so important in this practice.

Interlude: Social and Ethical Practice of Evaluation

Evaluation is a social practice that documents, portrays, and seeks to understand the value of a particular project, program, or policy. This can be determined by different evaluation methodologies, of course. But the value of qualitative case study is that it is possible to discern this value without decontextualizing the data. While the focus of the case is usually a project, program, policy, or some unit within, studies of key individuals, what I term case profiles , may be embedded within the overall case. In some instances, these profiles, or even shorter cameos of individuals, may be quite prominent. For it is through the perceptions, interpretations, and interactions of people that we learn how policies and programs are enacted ( Kushner, 2000 , p. 12). The program is still the main focus of analysis, but, in exploring how individuals play out their different roles in the program, we get closer to the actual experience and meaning of the program in practice.

Case study evaluation is often commissioned from an external source (government department or other agency) keen to know the worth of publicly funded programs and policies to inform future decision making. It needs to be responsive to issues or questions identified by stakeholders, who often have different values and interests in the expected outcomes and appreciate different perspectives of the program in action. The context also is often highly politicized, and interests can conflict. The task of the evaluator in such situations becomes one of including and balancing all interests and values in the program fairly and justly.

This is an inherently political process and requires an ethical practice that offers participants some protection over the personal data they give as part of the research and agreed audiences access to the findings, presented in ways they can understand. Negotiating what information becomes public can be quite difficult in singular settings where people are identifiable and intricate or problematic transactions have been documented. The consequences that ensue from making knowledge public that hitherto was private may be considerable for those in the case. It may also be difficult to portray some of the contextual detail that would enhance understanding for readers.

The ethical stance that underpins the case study research and evaluation I conduct stems from a theory of ethics that emphasizes the centrality of relationships in the specific context and the consequences for individuals, while remaining aware of the research imperative to publicly report. It is essentially an independent democratic process based on the concepts of fairness and justice, in which confidentiality, negotiation, and accessibility are key principles ( MacDonald, 1976 ; Simons, 2009 , pp. 96–111; and Simons 2010 ). The principles are translated into specific procedures to guide the collection, validation, and dissemination of data in the field. These include:

engaging participants and stakeholders in identifying issues to explore and sometimes also in interpreting the data;

documenting how different people interpret and value the program;

negotiating what data becomes public respecting both the individual’s “right to privacy” and the public’s “right to know”;

offering participants opportunities to check how their data are used in the context of reporting;

reporting in language and forms accessible to a wide range of audiences;

disseminating to audiences within and beyond the case.

For further discussion of the ethics of democratic case study evaluation and examples of their use in practice, see Simons (2000 , 2006 , 2009 , chapter 6, 2010 ).

Designing Case Study Research

Design issues in case study sometimes take second place to those of data gathering, the more exciting task perhaps in starting research. However, it is critical to consider the design at the outset, even if changes are required in practice due to the reality of what is encountered in the field. In this sense, the design of case study is emergent, rather than preordinate, shaped and reshaped as understanding of the significance of foreshadowed issues emerges and more are discovered.

Before entering the field, there are a myriad of planning issues to think about related to stakeholders, participants, and audiences. These include whose values matter, whether to engage them in data gathering and interpretation, the style of reporting appropriate for each, and the ethical guidelines that will underpin data collection and reporting. However, here I emphasize only three: the broad focus of the study, what the case is a case of, and framing questions/issues. These are steps often ignored in an enthusiasm to gather data, resulting in a case study that claims to be research but lacks the basic principles required for generation of valid, public knowledge.

Conceptualize the Topic

First, it is important that the topic of the research is conceptualized in a way that it can be researched (i.e., it is not too wide). This seems an obvious point to make, but failure to think through precisely what it is about your research topic you wish to investigate will have a knock-on effect on the framing of the case, data gathering, and interpretation and may lead, in some instances, to not gathering or analyzing data that actually informs the topic. Further conceptualization or reconceptualization may be necessary as the study proceeds, but it is critical to have a clear focus at the outset.

What Constitutes the Case

Second, I think it is important to decide what would constitute the case (i.e., what it is a case of) and where the boundaries of this lie. This often proves more difficult than first appears. And sometimes, partly because of the semifluid nature of the way the case evolves, it is only possible to finally establish what the case is a case of at the end. Nevertheless, it is useful to identify what the case and its boundaries are at the outset to help focus data collection while maintaining an awareness that these may shift. This is emergent design in action.

In deciding the boundary of the case, there are several factors to bear in mind. Is it bounded by an institution or a unit within an institution, by people within an institution, by region, or by project, program or policy,? If we take a school as an example, the case could be comprised of the principal, teachers, and students, or the boundary could be extended to the cleaners, the caretaker, the receptionist, people who often know a great deal about the subnorms and culture of the institution.

If the case is a policy or particular parameter of a policy, the considerations may be slightly different. People will still be paramount—those who generated the policy and those who implemented it—but there is likely also to be a political culture surrounding the policy that had an influence on the way the policy evolved. Would this be part of the case?

Whatever boundary is chosen, this may change in the course of conducting the study when issues arise that can only be understood by going to another level. What transpires in a classroom, for example, if this is the case, is often partly dependent on the support of the school leadership and culture of the institution and this, in turn, to some extent is dependent on what resources are allocated from the local education administration. Much like a series of Russian dolls, one context inside the other.

Unit of analysis

Thinking about what would constitute the unit of analysis— a classroom, an institution, a program, a region—may help in setting the boundaries of the case, and it will certainly help when it comes to analysis. But this is a slightly different issue from deciding what the case is a case of. Taking a health example, the case may be palliative care support, but the unit of analysis the palliative care ward or wards. If you took the palliative care ward as the unit of analysis this would be as much about how palliative care was exercised in this or that ward than issues about palliative care support in general. In other words, you would need to have specific information and context about how this ward was structured and managed to understand how palliative care was conducted in this particular ward. Here, as in the school example above, you would need to consider which of the many people who populate the ward form part of the case—nurses, interns, or doctors only, or does it extend to patients, cleaners, nurse aides, and medical students?

Framing Questions and Issues