- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A10 - General

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A13 - Relation of Economics to Social Values

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in A2 - Economic Education and Teaching of Economics

- A20 - General

- A23 - Graduate

- Browse content in A3 - Collective Works

- A31 - Collected Writings of Individuals

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B0 - General

- B00 - General

- Browse content in B1 - History of Economic Thought through 1925

- B10 - General

- B12 - Classical (includes Adam Smith)

- B16 - History of Economic Thought: Quantitative and Mathematical

- Browse content in B2 - History of Economic Thought since 1925

- B22 - Macroeconomics

- B26 - Financial Economics

- B27 - International Trade and Finance

- B29 - Other

- Browse content in B3 - History of Economic Thought: Individuals

- B31 - Individuals

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B40 - General

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in B5 - Current Heterodox Approaches

- B50 - General

- B52 - Institutional; Evolutionary

- B54 - Feminist Economics

- B55 - Social Economics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C02 - Mathematical Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C20 - General

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C45 - Neural Networks and Related Topics

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C54 - Quantitative Policy Modeling

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- C68 - Computable General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C88 - Other Computer Software

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D00 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D45 - Rationing; Licensing

- D47 - Market Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D53 - Financial Markets

- D57 - Input-Output Tables and Analysis

- D58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- D69 - Other

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E00 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- E02 - Institutions and the Macroeconomy

- E03 - Behavioral Macroeconomics

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E10 - General

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- E13 - Neoclassical

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E40 - General

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- E64 - Incomes Policy; Price Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- E66 - General Outlook and Conditions

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F00 - General

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F20 - General

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- F24 - Remittances

- F29 - Other

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- F37 - International Finance Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- F38 - International Financial Policy: Financial Transactions Tax; Capital Controls

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F45 - Macroeconomic Issues of Monetary Unions

- F47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- F59 - Other

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F62 - Macroeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F64 - Environment

- F65 - Finance

- F66 - Labor

- F68 - Policy

- F69 - Other

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G17 - Financial Forecasting and Simulation

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G35 - Payout Policy

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G39 - Other

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G50 - General

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H10 - General

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- H13 - Economics of Eminent Domain; Expropriation; Nationalization

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- H29 - Other

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- H44 - Publicly Provided Goods: Mixed Markets

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H62 - Deficit; Surplus

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- H68 - Forecasts of Budgets, Deficits, and Debt

- H69 - Other

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H73 - Interjurisdictional Differentials and Their Effects

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H84 - Disaster Aid

- H87 - International Fiscal Issues; International Public Goods

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- I19 - Other

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped; Non-Labor Market Discrimination

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J40 - General

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J44 - Professional Labor Markets; Occupational Licensing

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J58 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J60 - General

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J70 - General

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K0 - General

- K00 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K10 - General

- K11 - Property Law

- K12 - Contract Law

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K20 - General

- K21 - Antitrust Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- K29 - Other

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K31 - Labor Law

- K32 - Environmental, Health, and Safety Law

- K33 - International Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- K37 - Immigration Law

- K38 - Human Rights Law: Gender Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- K49 - Other

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L24 - Contracting Out; Joint Ventures; Technology Licensing

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- L38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L40 - General

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- L42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity Discounts

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L50 - General

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- L53 - Enterprise Policy

- L59 - Other

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L65 - Chemicals; Rubber; Drugs; Biotechnology

- Browse content in L7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and Construction

- L71 - Mining, Extraction, and Refining: Hydrocarbon Fuels

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L80 - General

- L81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; e-Commerce

- L86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer Software

- L88 - Government Policy

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L90 - General

- L92 - Railroads and Other Surface Transportation

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M10 - General

- M11 - Production Management

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- M14 - Corporate Culture; Social Responsibility

- M16 - International Business Administration

- M2 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M41 - Accounting

- M42 - Auditing

- M48 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M53 - Training

- M54 - Labor Management

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N13 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N14 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N33 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N34 - Europe: 1913-

- N36 - Latin America; Caribbean

- N37 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N44 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N6 - Manufacturing and Construction

- N60 - General, International, or Comparative

- N64 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N70 - General, International, or Comparative

- Browse content in N9 - Regional and Urban History

- N94 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O21 - Planning Models; Planning Policy

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O35 - Social Innovation

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O42 - Monetary Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O44 - Environment and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- O49 - Other

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O51 - U.S.; Canada

- O52 - Europe

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O55 - Africa

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P0 - General

- P00 - General

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P10 - General

- P12 - Capitalist Enterprises

- P14 - Property Rights

- P16 - Political Economy

- P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P30 - General

- P36 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P46 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- P50 - General

- P51 - Comparative Analysis of Economic Systems

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q00 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Q02 - Commodity Markets

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q11 - Aggregate Supply and Demand Analysis; Prices

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q20 - General

- Q21 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q23 - Forestry

- Q25 - Water

- Q27 - Issues in International Trade

- Q28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q30 - General

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Q34 - Natural Resources and Domestic and International Conflicts

- Q35 - Hydrocarbon Resources

- Q38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q40 - General

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q42 - Alternative Energy Sources

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Q48 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q50 - General

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q55 - Technological Innovation

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R32 - Other Spatial Production and Pricing Analysis

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R40 - General

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- R42 - Government and Private Investment Analysis; Road Maintenance; Transportation Planning

- R48 - Government Pricing and Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R50 - General

- R51 - Finance in Urban and Rural Economies

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- R53 - Public Facility Location Analysis; Public Investment and Capital Stock

- R58 - Regional Development Planning and Policy

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Z18 - Public Policy

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Oxford Review of Economic Policy

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Impact Factor 6.8

5 year Impact Factor 5.8

Economics 26 out of 380

Managing Editor

Christopher Adam

About the journal

The Oxford Review of Economic Policy is a refereed journal which is published quarterly. Each issue concentrates on a current theme in economic policy, with a balance between macro- and microeconomics, and comprises an assessment and a number of articles.

The Economics of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Oxford Review of Economic Policy has commissioned a series of articles in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Each of these articles will be free to access.

The economics of the COVID-19 pandemic: Virtual talks

Join OxREP in a series of virtual talks, running in July 2020, on the economics of the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on economic activity, employment, supply & demand, globalisation, trade, the developing countries, businesses and gender balance.

Find out more

The economics of Brexit: What is at stake?

This Special Issue brings together economic experts to identify the principal questions and possible effects of Brexit on economic policy.

Watch videos with the issue's authors discussing their research or read the full issue online.

Highly cited articles

Explore a collection showcasing some of the most highly cited articles from Oxford Review of Economic Policy .

Explore now

Latest articles

Latest posts on x.

Oxford Review of Economic Policy

What does the Oxford Review of Economic Policy (OxREP) stand for and why should you read it?

Browse all OxREP videos

Cameron Hepburn on Climate change policy after Brexit

Learn more about the implications of the referendum and, eventually, of Brexit for the economics of climate change in the UK, the EU, and beyond.

Read t he article

Thomas Sampson on the post-Brexit trade negotiations

Learn more about the main options for future UK–EU trade relations.

Read the article

Catherine Barnard on Law and Brexit

Learn more about some of the legal issues which will frame the Brexit negotiations.

R ead the article

From the OUPblog

Food and agriculture: shifting landscapes for policy

Where does our food come from? A popular slogan tells us that our food comes from farms: “If you ate today, thank a farmer.” Supermarkets cater to the same idea, labelling every bag of produce with the name of an individual farm…

Read the blog post | Read the article

Field experimenting in economics: Lessons learned for public policy

Do neighbourhoods matter to outcomes? Which classroom interventions improve educational attainment? How should we raise money to provide important and valued public goods?...

Unconventional monetary policy

Central banks in advanced economies typically conduct monetary policy by varying short-term interest rates in order to influence the level of spending and inflation in the economy. One limitation of this conventional approach to monetary policy is the so called lower bound problem…

The good, the bad, the missed opportunities

Popular perceptions of governments’ economic records are often shaped by the specific events that precipitate their downfall. From devaluation crises in the 1960s, through industrial relations in the 1970s, to the debacle of the poll tax in the 1990s…

Recommend to your library

Fill out our simple online form to recommend Oxford Review of Economic Policy to your library.

Recommend now

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

publicationethics.org

Related Titles

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2121

- Print ISSN 0266-903X

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press and Oxford Review of Economic Policy Limited

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- About the New York Fed

- Bank Leadership

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Communities We Serve

- Board of Directors

- Disclosures

- Ethics and Conflicts of Interest

- Annual Financial Statements

- News & Events

- Advisory Groups

- Vendor Information

- Holiday Schedule

At the New York Fed, our mission is to make the U.S. economy stronger and the financial system more stable for all segments of society. We do this by executing monetary policy, providing financial services, supervising banks and conducting research and providing expertise on issues that impact the nation and communities we serve.

Introducing the New York Innovation Center: Delivering a central bank innovation execution

Do you have a request for information and records? Learn how to submit it.

Learn about the history of the New York Fed and central banking in the United States through articles, speeches, photos and video.

- Markets & Policy Implementation

- Reference Rates

- Effective Federal Funds Rate

- Overnight Bank Funding Rate

- Secured Overnight Financing Rate

- SOFR Averages & Index

- Broad General Collateral Rate

- Tri-Party General Collateral Rate

- Desk Operations

- Treasury Securities

- Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Reverse Repos

- Securities Lending

- Central Bank Liquidity Swaps

- System Open Market Account Holdings

- Primary Dealer Statistics

- Historical Transaction Data

- Monetary Policy Implementation

- Agency Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Agency Debt Securities

- Repos & Reverse Repos

- Discount Window

- Treasury Debt Auctions & Buybacks as Fiscal Agent

- INTERNATIONAL MARKET OPERATIONS

- Foreign Exchange

- Foreign Reserves Management

- Central Bank Swap Arrangements

- Statements & Operating Policies

- Survey of Primary Dealers

- Survey of Market Participants

- Annual Reports

- Primary Dealers

- Standing Repo Facility Counterparties

- Reverse Repo Counterparties

- Foreign Exchange Counterparties

- Foreign Reserves Management Counterparties

- Operational Readiness

- Central Bank & International Account Services

- Programs Archive

- Economic Research

- Consumer Expectations & Behavior

- Survey of Consumer Expectations

- Household Debt & Credit Report

- Home Price Changes

- Growth & Inflation

- Equitable Growth Indicators

- Multivariate Core Trend Inflation

- New York Fed DSGE Model

- New York Fed Staff Nowcast

- R-star: Natural Rate of Interest

- Labor Market

- Labor Market for Recent College Graduates

- Financial Stability

- Corporate Bond Market Distress Index

- Outlook-at-Risk

- Treasury Term Premia

- Yield Curve as a Leading Indicator

- Banking Research Data Sets

- Quarterly Trends for Consolidated U.S. Banking Organizations

- Empire State Manufacturing Survey

- Business Leaders Survey

- Supplemental Survey Report

- Regional Employment Trends

- Early Benchmarked Employment Data

- INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY

- Global Economic Indicators

- Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

- Staff Economists

- Visiting Scholars

- Resident Scholars

- PUBLICATIONS

- Liberty Street Economics

- Staff Reports

- Economic Policy Review

- RESEARCH CENTERS

- Applied Macroeconomics & Econometrics Center (AMEC)

- Center for Microeconomic Data (CMD)

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- Financial Institution Supervision

- Regulations

- Reporting Forms

- Correspondence

- Bank Applications

- Community Reinvestment Act Exams

- Frauds and Scams

As part of our core mission, we supervise and regulate financial institutions in the Second District. Our primary objective is to maintain a safe and competitive U.S. and global banking system.

The Governance & Culture Reform hub is designed to foster discussion about corporate governance and the reform of culture and behavior in the financial services industry.

Need to file a report with the New York Fed? Here are all of the forms, instructions and other information related to regulatory and statistical reporting in one spot.

The New York Fed works to protect consumers as well as provides information and resources on how to avoid and report specific scams.

- Financial Services & Infrastructure

- Services For Financial Institutions

- Payment Services

- Payment System Oversight

- International Services, Seminars & Training

- Tri-Party Repo Infrastructure Reform

- Managing Foreign Exchange

- Money Market Funds

- Over-The-Counter Derivatives

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York works to promote sound and well-functioning financial systems and markets through its provision of industry and payment services, advancement of infrastructure reform in key markets and training and educational support to international institutions.

The New York Fed provides a wide range of payment services for financial institutions and the U.S. government.

The New York Fed offers the Central Banking Seminar and several specialized courses for central bankers and financial supervisors.

The New York Fed has been working with tri-party repo market participants to make changes to improve the resiliency of the market to financial stress.

- Community Development & Education

- Household Financial Well-being

- Fed Communities

- Fed Listens

- Fed Small Business

- Workforce Development

- Other Community Development Work

- High School Fed Challenge

- College Fed Challenge

- Teacher Professional Development

- Classroom Visits

- Museum & Learning Center Visits

- Educational Comic Books

- Economist Spotlight Series

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- Economic Education Calendar

We are connecting emerging solutions with funding in three areas—health, household financial stability, and climate—to improve life for underserved communities. Learn more by reading our strategy.

The Economic Inequality & Equitable Growth hub is a collection of research, analysis and convenings to help better understand economic inequality.

- Request a Speaker

- International Seminars & Training

- Governance & Culture Reform

- Data Visualization

- Economic Research Tracker

- Markets Data APIs

- Terms of Use

Monetary Policy, Segmentation, and the Term Structure

We develop a segmented markets model which rationalizes the effects of monetary policy on the term structure of interest rates. When arbitrageurs’ portfolio features positive duration, an unexpected rise in the short rate lowers their wealth and raises term premia. A calibration to the U.S. economy accounts for the transmission of monetary shocks to long rates. We discuss the additional implications of our framework for state-dependence in policy transmission, the volatility and slope of the yield curve, and trends in term premia accompanying trends in the natural rate.

An early version of this paper circulated under the title “Heterogeneity, Monetary Policy, and the Term Premium”. We thank Michael Bauer, Luigi Bocola, Anna Cieslak, James Costain, Vadim Elenev, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Robin Greenwood, Sam Hanson, Ben Hebert, Christian Heyerdahl-Larsen, Sydney Ludvigson, Hanno Lustig, Anil Kashyap, Arvind Krishnamurthy, Matteo Maggiori, Stavros Panageas, Carolin Pflueger, Monika Piazzesi, Walker Ray, Alp Simsek, Eric Swanson, Dimitri Vayanos, Olivier Wang, Wei Xiong, and Motohiro Yogo for discussions. We thank Manav Chaudhary, Lipeng (Robin) Li, and Jihong Song for excellent research assistance. This research has been supported by the National Science Foundation grant SES-2117764. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

- data appendix

- Code to solve model

Conferences

More from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

International Economics and Economic Policy

International Economics and Economic Policy publishes theoretical and empirical research relevant to economic policy, serving as a forum for dialogue between academics and policymakers.

- Focusses on comparative economic policy, international political economy, including international organizations and policy cooperation.

- Covers monetary and real/technological dynamics in open economies as well as globalization and regional integration, trade, international investment and migration.

- Includes topics like internet commerce, and regulation.

- Features contributions from the economic policy community.

This is a transformative journal , you may have access to funding.

- Joscha Beckmann

- Robert Czudaj

Latest issue

Volume 21, Issue 1

Latest articles

Harmonizing renewable energy and economic growth in sub-saharan africa: the transformative potential of ict.

- Jeremiah Msugh Tule

- Peter Francis Offum

- Olufunke Meadows

The dynamic interplay of foreign direct investment and education expenditure on Sub-Saharan Africa income inequality

- Hassan Swedy Lunku

Exploring the dynamics of the balance of payments problems: the case of Afghanistan

- Abdul Hadi Sultani

The effect of remittances on the Indian economy

- Irfan Ahmad Shah

You are uncertain and we are at stress! How does monetary policy uncertainty affect financial stress? The case of the US and G7

- Swarn Rajan

Journal updates

Call for papers: deadline prolongated for collection/special issue on "policy challenges in times of high inflation".

New submission deadline: 31 March 2025

Celebrating our first Impact Factor!

IEEP team mourns the loss of Paul J. J. Welfens

We mourn for Paul J. J. Welfens who passed away on November 11, 2022.

Journal information

- Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) Journal Quality List

- Emerging Sources Citation Index

- Google Scholar

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- Research Papers in Economics (RePEc)

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Springer policies

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Working Papers

Main navigation.

Working paper submission form for Stanford faculty

Site content

- Davis, S., & Samaniego de la Parra, B. (2024). Application Flows . Working Paper.

- Davis, S., Haltiwanger, J., Handley, K., Lipsius, B., Lerner, J., & Miranda, J. (2024). The (Heterogenous) Economic Effects of Private Equity Buyouts . Working Paper.

- Kluender, R., Mahoney, N., Wong, F., & Yin, W. (2024). The Effects of Medical Debt Relief: Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments . Working Paper.

- Pencavel, J. (2024). Accounting for the growth of Real wages of U.S. manufacturing Production workers in the Twentieth century .

- Davis, S. ., & Krolikowski, P. . (2024). Sticky Wages on the Layoff Margin . Working Paper.

- Clayton, C., Maggiori, M., & Schreger, J. (2024). A Framework for Geoeconomics . Working Paper.

- Donkor, K., Goette, L., Müller, M. ., Dimant, E., & Kurschilgen, M. (2023). Identity and Economic Incentives . Working Paper.

- Ferguson, B. ., & Milgrom, P. (2023). Market Design for Surface Water . Working Paper.

- Hoopes, J., Lester, R., Klein, D., & Olbert, M. (2023). Corporate Tax Policy in Developed Countries and Economic Activity in Africa . Working Paper.

- Einav, L., Klopack, B., & Mahoney, N. (2023). Selling Subscriptions . Working Paper.

- Fairlie, R. (2023). The Impacts of COVID-19 on Racial Inequality in Business Earnings .

- Abramitzky, R., Boustan, L. ., Jácome, E. ., Pérez, S., & Torres, J. . (2023). Law-Abiding Immigrants: The Incarceration Gap Between Immigrants and the US-born, 1850–2020 . Working Paper.

- Auclert, A., Monnery, H., Rognlie, M., & Straub, L. (2023). Managing an Energy Shock: Fiscal and Monetary Policy . Working Paper.

- Barrero, J. ., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. . (2023). The Evolution of Working from Home . Working Paper.

- Gottlieb, J., Polyakova, M., Rinz, K., Shiplett, H., & Udalova, V. (2023). Who Values Human Capitalists’ Human Capital? The Earnings and Labor Supply of U.S. Physicians . Working Paper.

- Hurst, E., Kehoe, P., Pastorino, E., & Winberry, T. (2023). The Macroeconomic Dynamics of Labor Market Policies . Working Paper.

- Duggan, M., Dushi, I., Jeong, S., & Li, G. (2023). The Effects of Changes in Social Security’s Delayed Retirement Credit: Evidence from Administrative Data . Working Paper.

- Jha, S., Shayo, M., & Weiss, C. . (2023). Financial Market Exposure Increases Generalized Trust, Particularly Among the Politically Polarized . Working Paper.

- Bursztyn, L., Cappelen, A. ., Tungodden, B., Voena, A., & Yanagizawa-Drott, D. . (2023). How Are Gender Norms Perceived? . Working Paper.

- Jiang, E., Matvos, G., Piskorski, T., & Seru, A. (2023). Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs? . Working Paper.

- Research & Outlook

World Bank Policy Research Working Papers

The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series encourages the exchange of ideas on development and quickly disseminates the findings of research in progress. This series is aimed at showcasing World Bank research—analytic work designed to produce results with wide applicability across countries or sectors. The authors are exclusively World Bank staff and consultants.

Recent Papers by theme

- Infrastructure

Search the Entire Series

You can search the series by author, country, region, title, topic...etc.

Series Hubs

INSIDE THIS SERIES

⇰ Working Papers with Reproducibility Packages

⇰ Working Papers on COVID-19

⇰ Working Papers on Impact Evaluation

⇰ Working Papers funded by KCP

- Development Economics Department

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 15 April 2024

Revealed: the ten research papers that policy documents cite most

- Dalmeet Singh Chawla 0

Dalmeet Singh Chawla is a freelance science journalist based in London.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

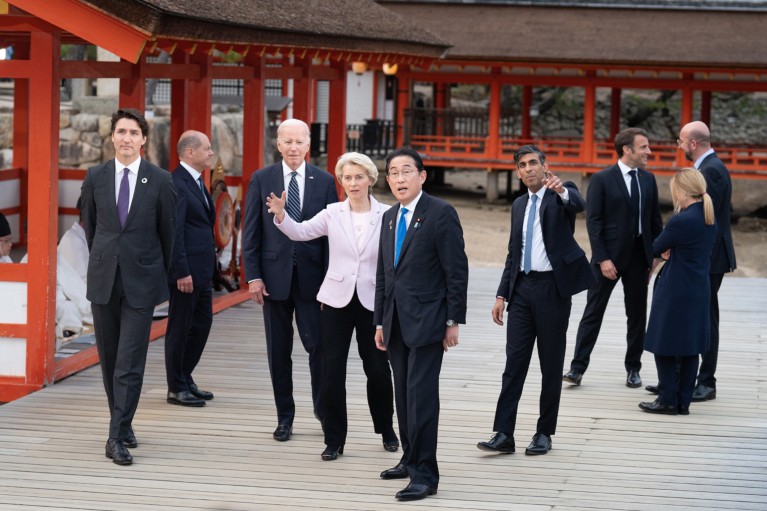

Policymakers often work behind closed doors — but the documents they produce offer clues about the research that influences them. Credit: Stefan Rousseau/Getty

When David Autor co-wrote a paper on how computerization affects job skill demands more than 20 years ago, a journal took 18 months to consider it — only to reject it after review. He went on to submit it to The Quarterly Journal of Economics , which eventually published the work 1 in November 2003.

Autor’s paper is now the third most cited in policy documents worldwide, according to an analysis of data provided exclusively to Nature . It has accumulated around 1,100 citations in policy documents, show figures from the London-based firm Overton (see ‘The most-cited papers in policy’), which maintains a database of more than 12 million policy documents, think-tank papers, white papers and guidelines.

“I thought it was destined to be quite an obscure paper,” recalls Autor, a public-policy scholar and economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “I’m excited that a lot of people are citing it.”

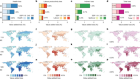

The most-cited papers in policy

Economics papers dominate the top ten papers that policy documents reference most.

Data from Sage Policy Profiles as of 15 April 2024

The top ten most cited papers in policy documents are dominated by economics research. When economics studies are excluded, a 1997 Nature paper 2 about Earth’s ecosystem services and natural capital is second on the list, with more than 900 policy citations. The paper has also garnered more than 32,000 references from other studies, according to Google Scholar. Other highly cited non-economics studies include works on planetary boundaries, sustainable foods and the future of employment (see ‘Most-cited papers — excluding economics research’).

These lists provide insight into the types of research that politicians pay attention to, but policy citations don’t necessarily imply impact or influence, and Overton’s database has a bias towards documents published in English.

Interdisciplinary impact

Overton usually charges a licence fee to access its citation data. But last year, the firm worked with the London-based publisher Sage to release a free web-based tool that allows any researcher to find out how many times policy documents have cited their papers or mention their names. Overton and Sage said they created the tool, called Sage Policy Profiles, to help researchers to demonstrate the impact or influence their work might be having on policy. This can be useful for researchers during promotion or tenure interviews and in grant applications.

Autor thinks his study stands out because his paper was different from what other economists were writing at the time. It suggested that ‘middle-skill’ work, typically done in offices or factories by people who haven’t attended university, was going to be largely automated, leaving workers with either highly skilled jobs or manual work. “It has stood the test of time,” he says, “and it got people to focus on what I think is the right problem.” That topic is just as relevant today, Autor says, especially with the rise of artificial intelligence.

Most-cited papers — excluding economics research

When economics studies are excluded, the research papers that policy documents most commonly reference cover topics including climate change and nutrition.

Walter Willett, an epidemiologist and food scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, thinks that interdisciplinary teams are most likely to gain a lot of policy citations. He co-authored a paper on the list of most cited non-economics studies: a 2019 work 3 that was part of a Lancet commission to investigate how to feed the global population a healthy and environmentally sustainable diet by 2050 and has accumulated more than 600 policy citations.

“I think it had an impact because it was clearly a multidisciplinary effort,” says Willett. The work was co-authored by 37 scientists from 17 countries. The team included researchers from disciplines including food science, health metrics, climate change, ecology and evolution and bioethics. “None of us could have done this on our own. It really did require working with people outside our fields.”

Sverker Sörlin, an environmental historian at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, agrees that papers with a diverse set of authors often attract more policy citations. “It’s the combined effect that is often the key to getting more influence,” he says.

Has your research influenced policy? Use this free tool to check

Sörlin co-authored two papers in the list of top ten non-economics papers. One of those is a 2015 Science paper 4 on planetary boundaries — a concept defining the environmental limits in which humanity can develop and thrive — which has attracted more than 750 policy citations. Sörlin thinks one reason it has been popular is that it’s a sequel to a 2009 Nature paper 5 he co-authored on the same topic, which has been cited by policy documents 575 times.

Although policy citations don’t necessarily imply influence, Willett has seen evidence that his paper is prompting changes in policy. He points to Denmark as an example, noting that the nation is reformatting its dietary guidelines in line with the study’s recommendations. “I certainly can’t say that this document is the only thing that’s changing their guidelines,” he says. But “this gave it the support and credibility that allowed them to go forward”.

Broad brush

Peter Gluckman, who was the chief science adviser to the prime minister of New Zealand between 2009 and 2018, is not surprised by the lists. He expects policymakers to refer to broad-brush papers rather than those reporting on incremental advances in a field.

Gluckman, a paediatrician and biomedical scientist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, notes that it’s important to consider the context in which papers are being cited, because studies reporting controversial findings sometimes attract many citations. He also warns that the list is probably not comprehensive: many policy papers are not easily accessible to tools such as Overton, which uses text mining to compile data, and so will not be included in the database.

The top 100 papers

“The thing that worries me most is the age of the papers that are involved,” Gluckman says. “Does that tell us something about just the way the analysis is done or that relatively few papers get heavily used in policymaking?”

Gluckman says it’s strange that some recent work on climate change, food security, social cohesion and similar areas hasn’t made it to the non-economics list. “Maybe it’s just because they’re not being referred to,” he says, or perhaps that work is cited, in turn, in the broad-scope papers that are most heavily referenced in policy documents.

As for Sage Policy Profiles, Gluckman says it’s always useful to get an idea of which studies are attracting attention from policymakers, but he notes that studies often take years to influence policy. “Yet the average academic is trying to make a claim here and now that their current work is having an impact,” he adds. “So there’s a disconnect there.”

Willett thinks policy citations are probably more important than scholarly citations in other papers. “In the end, we don’t want this to just sit on an academic shelf.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00660-1

Autor, D. H., Levy, F. & Murnane, R. J. Q. J. Econ. 118 , 1279–1333 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Costanza, R. et al. Nature 387 , 253–260 (1997).

Willett, W. et al. Lancet 393 , 447–492 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Steffen, W. et al. Science 347 , 1259855 (2015).

Rockström, J. et al. Nature 461 , 472–475 (2009).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

Use game theory for climate models that really help reach net zero goals

Correspondence 16 APR 24

Female academics need more support — in China as elsewhere

The world needs a COP for water like the one for climate change

Last-mile delivery increases vaccine uptake in Sierra Leone

Article 13 MAR 24

Global supply chains amplify economic costs of future extreme heat risk

How science is helping farmers to find a balance between agriculture and solar farms

Spotlight 19 FEB 24

Postdoctoral Research Associate position at University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

Postdoctoral Research Associate position at University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center The Kamiya Mehla lab at the newly established Departmen...

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

Computational Postdoctoral Fellow with a Strong Background in Bioinformatics

Houston, Texas (US)

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Locum Associate or Senior Editor (Immunology), Nature Communications

The Editor in Immunology at Nature Communications will handle original research papers and work on all aspects of the editorial process.

London, Beijing or Shanghai - Hybrid working model

Springer Nature Ltd

Assistant Professor - Cell Physiology & Molecular Biophysics

Opportunity in the Department of Cell Physiology and Molecular Biophysics (CPMB) at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC)

Lubbock, Texas

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine

Postdoctoral Associate- Curing Brain Tumors

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

How Quickly Do Prices Respond to Monetary Policy?

Download PDF (238 KB)

FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-10 | April 8, 2024

With inflation still above the Federal Reserve’s 2% objective, there is renewed interest in understanding how quickly federal funds rate hikes typically affect inflation. Beyond monetary policy’s well-known lagged effect on the economy overall, new analysis highlights that not all prices respond with the same strength or speed. Results suggest that inflation for the most responsive categories of goods and services has come down substantially from recent highs, likely due in part to more restrictive monetary policy. As a result, the contributions of these categories to overall inflation have fallen.

Monetary policy affects inflation with a lag. This means that, although interest rates react quickly when the Federal Reserve raises the federal funds rate, the effects on inflation are slower and indirect. Higher interest rates increase borrowing costs, slowing investment and overall demand, which ultimately eases the pressure on prices. Understanding the timing and strength of this mechanism is key for policymakers.

Many researchers have estimated the speed and strength of the economy’s response to monetary policy, notably Romer and Romer (2004). The focus is typically a broader measure of inflation, such as headline or core, which reflects an average across many goods and services. However, not all prices of the component goods and services react to monetary policy in the same way. For example, food and energy prices, which are excluded from core but included in headline inflation, often move more in response to global market fluctuations, such as changes in international oil prices, rather than to changes in domestic monetary policy.

In this Economic Letter , we estimate how prices of different goods and services respond to changes in the federal funds rate and use those estimates to build a monetary policy-responsive inflation index. We find substantial variation in how prices react to monetary policy, which suggests that understanding the makeup of overall inflation can provide insights into the transmission of monetary policy to inflation. The extent to which categories that are more responsive to the federal funds rate contribute to inflation affects how much slowing in economic activity is needed to reduce overall inflation. Our analysis indicates that recent ups and downs of inflation have been focused in categories that are most sensitive to monetary policy. Inflation rates for the most sensitive categories—and their contributions to headline inflation—rose from the first half of 2020 through mid-2022, reaching a higher peak than headline inflation, and then began to decline. The inflation rate for this most responsive group of goods and services categories is now close to its pre-2020 rate. Our findings suggest that the Fed’s rate hikes that began in March 2022 are exerting downward pressure on prices and will continue to do so in the near term. Our estimated lags are consistent with the view that the full effects of past policy tightening are still working their way through the economy.

Measuring how prices react to monetary policy

To understand which goods and services are most responsive to monetary policy, we need to determine how their prices react to changes in the federal funds rate, the Federal Reserve’s main policy rate. Because the Federal Reserve adjusts the federal funds rate target in response to macroeconomic developments, including inflation, we use a transformation of the federal funds rate in our estimation. This transformed series, developed by Romer and Romer (2004) and updated by Wieland and Yang (2020), captures the differences between Federal Reserve staff forecasts and the chosen target rate, leaving only policy shocks, or movements in the federal funds rate that are not driven by actual or anticipated changes in economic conditions. We use this series as a so-called instrument for the federal funds rate, such that our results can account for how the federal funds rate itself, rather than its transformation, affects inflation.

We use an approach developed by Jordà (2005) that compares two forecasts—with and without rate shocks—to estimate how the federal funds rate affects price movements over time. Specifically, we estimate the relationship between the federal funds rate and the cumulative percent change in prices, controlling for recent trends in the federal funds rate, inflation, and economic activity. Repeating this estimation over multiple horizons produces a forecast comparison, or impulse response function, that gives us an estimate of the expected percent change in prices following a rate increase. For example, applying this method to the headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index indicates that four years after a 1 percentage point increase in the federal funds rate, overall prices are typically about 2.5% below what they would have been without the rate increase.

Creating a policy-responsive inflation index

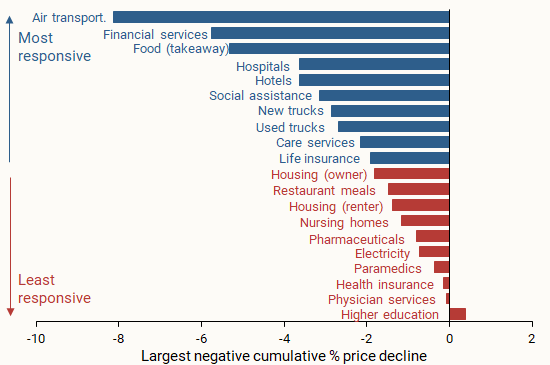

We estimate impulse response functions separately for the 136 goods and services categories that collectively make up headline PCE inflation. Figure 1 shows examples of the largest cumulative percent price declines over a four-year period in response to a 1 percentage point increase in the federal funds rate. The goods and services categories selected as examples account for large shares of total expenditures in headline PCE inflation. We also include one example of the few categories where prices do not decline, higher education, shown as a small positive value.

Figure 1 Reaction to a policy rate increase: Selected PCE categories

The takeaway from Figure 1 is that headline PCE inflation is made up of categories that differ in their responsiveness to increases in the federal funds rate. Some respond more strongly, such as those with larger typical cumulative price declines, while others respond less strongly, such as those with smaller typical price declines. Focusing on the most responsive categories can shed light on how monetary policy has influenced the path of inflation over the post-pandemic period. We use our results to divide the categories into two groups of goods and services. The most responsive group (blue bars) contains goods and services whose largest cumulative percent price decline over a four-year window is in the top 50% of all such declines. The least responsive group (red bars) contains goods and services in the bottom 50%.

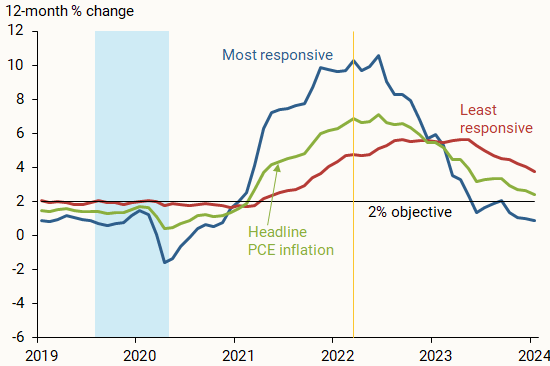

Following the methods in Shapiro (2022), we use these two groups, along with the share of total expenditures for each good or service, to create two new aggregate PCE inflation measures. Figure 2 shows their 12-month percent changes over time. The blue shading marks the period from mid-2019 until early 2020 when the Federal Reserve lowered the federal funds rate. The vertical yellow line marks the start of the most recent tightening cycle in March 2022. Inflation in the most responsive categories (blue line) is more volatile than overall headline PCE inflation (green line) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), and inflation in the least responsive categories is less volatile (red line).

Figure 2 Most and least responsive inflation rates

After the start of the 2020 recession, inflation rates for both categories rose but have since come down from their recent peaks. This pattern is particularly pronounced for the most responsive inflation group, for which inflation peaked at 10.5% in mid-2022 and has fallen to 0.9% as of January 2024; this is just under its average of 1% from 2012, when the Federal Reserve officially adopted a numerical inflation objective, to 2019. Inflation in the least responsive group peaked later, in early 2023, and has fallen only slightly to 3.8% as of January 2024; it remains well above its 2012–2019 average of 1.8%.

How does policy-responsive inflation react to rate increases?

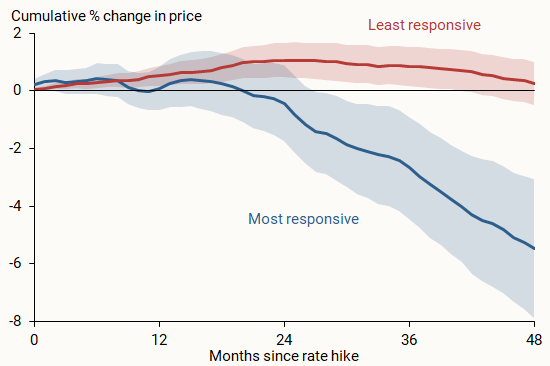

The inflation rates of categories in the most and least responsive groups can move for reasons beyond changes in the federal funds rate, such as global or national macroeconomic developments. To assess the specific role of policy rate increases, we use the methodology described earlier to estimate how the most and least responsive inflation groups tend to react to rate hikes.

The results in Figure 3 suggest that an increase in the federal funds rate typically starts exerting downward pressure on the most responsive prices after about 18 months, when the line showing the impulse response function falls below zero. Month-to-month price changes start falling after a little over a year, depicted when the slope drops below zero and stays negative. This is quicker than the response of overall headline prices from the BEA (not shown), which becomes negative after a little over 24 months and shows month-to-month declines after about 18 months.

Figure 3 Reaction of most and least responsive prices to rate hikes

Because we grouped inflation categories based on the size of their response, there is not necessarily a tie-in to the speed of each categories’ change. However, our results suggest that looking at the most responsive goods and services may also be a useful way of assessing how quickly monetary policy affects inflation.

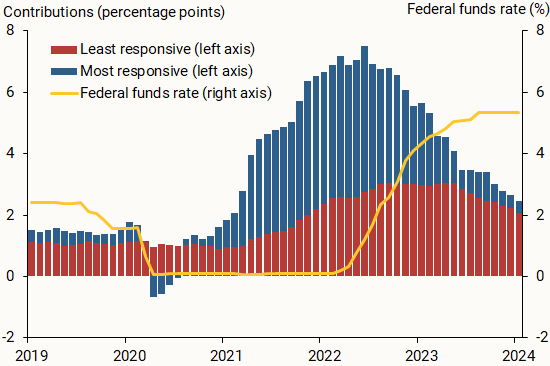

Applying the typical impact timing of the most responsive group of goods and services to the most recent tightening cycle, shown by the federal funds rate line in Figure 4, leads to several conclusions. First, rate cuts from 2019 to early 2020 could have contributed upward price pressures starting in mid- to late 2020 and thus could explain some of the rise in inflation over this period. Second, the tightening cycle that began in March 2022 likely started putting downward pressure on prices in mid-2023 and will continue to do so in the near term. This is consistent with the view that the full effects of monetary policy tightening have yet to be felt. Finally, though inflation for the most responsive categories has been falling since mid-2022, the early part of this decline was likely to have been driven more by changes in prevailing economic conditions than by policy tightening, given estimated policy lags. Some research has considered whether policy lags have shortened (see, for example, Doh and Foerster 2021); however, because inflation began falling mere months after the first rate hike, the drop in inflation may have been too soon to be caused by policy action.

Figure 4 Headline inflation contributions and the federal funds rate

Our findings in this Letter are useful for broadening our understanding of how monetary policy affects inflation. For example, if inflation and the contributions to overall headline inflation are high in a set of categories that are more responsive to monetary policy, as was the case in early 2022, then rate hikes during the most recent tightening cycle are likely to continue to reduce inflation due to policy lags. On the other hand, though inflation in the least responsive categories may come down because of other economic forces, less inflation is currently coming from categories that are most responsive to monetary policy, perhaps limiting policy impacts going forward.

Doh, Taeyoung, and Andrew T. Foerster. 2022. “ Have Lags in Monetary Policy Transmission Shortened? ” FRB Kansas City Economic Bulletin (December 21).

Jordà, Òscar. 2005. “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections.” American Economic Review 95(1), pp. 161–182.

Romer, Christina, and David Romer. 2004. “A New Measure of Monetary Shocks: Derivation and Implications.” American Economic Review 94(4), pp. 1,055–1,084.

Shapiro, Adam. 2022. “ A Simple Framework to Monitor Inflation .” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2020-29.

Wieland, Johannes, and Mu‐Jeung Yang. 2020. “Financial Dampening.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 52(1), pp. 79–113.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to [email protected]

U.S. Department of the Treasury

Economic policy archive, treasury social security issue briefs.

- Issue Brief No. 6: Social Security Reform: Work in Incentives

- Issue Brief No. 5: Social Security Reform: Strategies for Progressive Benefit Adjustments

- Issue Brief No. 4: Social Security Reform: Mechanisms for Achieving True Pre-Funding

- Issue Brief No. 3: Social Security Reform: Benchmarks for Assessing Fairness and Benefit Adequacy

- Issue Brief No. 2: Social Security Reform: A Framework for Analysis

- Issue Brief No. 1: Social Security Reform: The Nature of the Problem

- 2016 Economic Policy Indicators Calendar - monthly (Portrait) (as of 01/04/2016)

- History of the Financial Report of the United States Government

- Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds and The Federal Budget (MAY 2009)

- The Impact of Post-9/11 Visa Policies on Travel to the United States (JUN 2007)

- Fact Sheet on Surveys of Terrorism Risk Insurance Markets (OCT 2003)

- The Jobs & Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act and the Increase in Dividends (JUL 2003)

- Trade, Investment and the Current Account: Imports = Exports + Net Foreign Investment (JAN 2003)

- Do Budget Deficits Raise Interest Rates? (JAN 2003)

- Fiscal Discipline = Spending Restraint (DEC 2002)

- The Effect of Deficits on Prices of Financial Assets: Theory and Evidence (MAR 1984)

Economic Research Papers

The Economic Policy Research Paper Series offers staff an opportunity to disseminate their preliminary research findings in a format intended to generate discussion and critical comments. The goal is to further the staff's knowledge and expertise on a given subject. The working papers are considered works in progress and are subject to revision. The views and opinions expressed in the working papers are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official Treasury positions or policy.

- The Effects of Principal Reduction on HAMP Early Redefault Rates

- Summary of the Effects of Principal Reduction on HAMP Early Redefault Rates

- Is Regulatory Uncertainty a Major Impediment to Job Growth?

- The Returns Paid to Early Social Security Cohorts. James E. Duggan, Robert Gillingham and John S. Greenlees. April 1993

- Possible Alternatives to the Medicare Trustees' Long-Term Projections of Health Spending, by Jason D. Brown and Ralph M. Monaco

- Prefunding Social Security Benefits to Achieve Intergenerational Fairness: Can It be done in the Social Security Trust Fund? by Randall P. Mariger

- Do Social Security Surpluses Pay Down Publicly Held Debt? Evidence from Budget Data

- The Impact of Post-9/11 Visa Policies on Travel to the United States by Brent Neiman and Phillip Swagel

- Mortality and Lifetime Income: Evidence from Social Security Records, by James E. Duggan, Robert Gillingham, and John S. Greenlees

- "Implications of Returns on Treasury Inflation-Indexed Securities for Projections of the Long-Term Real Interest Rate" by James A. Girola

- The Long-Term Real Interest Rate for Social Security by James A. Girola

- Annuity Risk: Volatility and Inflation Exposure in Payments from Immediate Life Annuities

- Social Security and the Public Debt. James E. Duggan. October 1991

- Distributional Effects of Social Security: The Notch Issue Revisited. James E. Duggan, Robert Gillingham and John S. Greenlees. Revised April 1995

- Progressive Returns to Social Security? An Answer from Social Security Records. James E. Duggan , Robert Gillingham and John S. Greenlees. November 1995

- Actuarial Nonequivalence in Early and Delayed Social Security Benefit Claims, by James E. Duggan and Christopher Soares