Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

The Definitions of Sharing Economy: A Systematic Literature Review

- Author & abstract

- 4 References

- Most related

- Related works & more

Corrections

(Kaposvár University, Hungary)

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher, references listed on ideas.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Theoretical dilemmas, conceptual review and perspectives disclosure of the sharing economy: a qualitative analysis

- Review Paper

- Published: 26 October 2020

- Volume 15 , pages 1849–1883, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Manuel Sánchez-Pérez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3709-3389 1 ,

- Nuria Rueda-López ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5719-7620 1 ,

- María Belén Marín-Carrillo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6784-0560 1 &

- Eduardo Terán-Yépez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1260-2477 1

4657 Accesses

11 Citations

Explore all metrics

The sharing economy (SE) has become a prominent theme in a broad variety of research domains in the last decade. With conceptions from an increasing range of theoretical perspectives, SE literature is disperse and disconnected, with a great proliferation of definitions and related terms which hinder organized and harmonious research. This study carries out a systematic literature review from 1978 to September 2020, uncovering 50 definitions as units of analysis. The authors, through a qualitative–interpretative analysis, review definitions, identify perspectives, and critically assess their conceptual nature on an evolutionary basis. Findings show that despite the SE has been extending its routes and approaches, it is far from a stock of conceptual grounds. The paper makes three contributions. First, we portray SE within a common evolutionary framework by developing it as a life cycle model. Second, we clarify the definitional and terminological jungle. And third, we suggest a new definition that can enrich the discussion.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Sharing Economy in Europe: From Idea to Reality

The state and critical assessment of the sharing economy in europe.

Availability Cascades and the Sharing Economy: A Critique of Sharing Economy Narratives

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sharing economy research faces an uncontrolled emergence of related terms and definitions, due to its rise to the forefront of entrepreneurship, innovation, technology and management (Bouncken et al. 2020 ; Bouncken and Reuschl 2018 ; Muñoz and Cohen 2017 ). This has triggered a proliferation of contributions, continuously expanding its nature and scope. This growth is not without controversy, in part because of the diversity of approaches and definitions (Filser et al. 2020 ; Hossain 2020 ; Paik et al. 2019 ), in part because of its profound economic, social, legal and political implications (Codagnone and Martens 2016 ), in addition to the limited empirical contributions (Laurenti et al. 2019 ), which have led to contradiction, confusion, and complexity surrounding its identity. Therefore, this study aims to contribute to determining the nature and scope of the SE through examining the conceptual evolution, by organizing definitions and terms, identifying perspectives, and providing an evolutionary framework to facilitate theory development and guide future research.

Beyond the interest to study the SE at an institutional level (European Commission 2017 , 2018 ; U.S. Department of the Treasury 2019), the economic and social relevance of the increasingly employed activities encompassed within the SE is unquestionable. To mention some examples, 26% of U.S. Internet users participated in SE services and these figures are predicted to rise to 41% in 2021 (eMarketer 2019 ). Further, the number of active “peer-to-peer” or sharing platforms in the Europe Union in 2017 was around 500, of which at least 4% were considered to be extremely significant, as they received more than 100,000 visits a day, generating revenues of more than $4,000 million and facilitating transactions of more than $25,000 million (European Commission 2017 ).

At the academic level, the growing relevance of the SE is undeniable, and this is reflected from various points of view. In the Web of Science (WoS) database alone, about 1,400 articles and reviews addressing SE-related topics can be found until 15 September 2020, of which more than 87% have been published since 2017. These articles have been published in more than 390 journals, which also shows the growing demand for journals that are open to publishing work in this area. Moreover, these publications relate to very diverse research domains, such as business, management, tourism and hospitality, environmental sciences, computer science, economics, and to a lesser extent to areas such as legal sciences, urban planning and development, and sociology.

But what has been happening with the SE? After the first and occasional contribution on the SE at the end of the 1970s (Felson and Spaeth 1978 ), there followed a period of lack of interest in this concept, which then rose to the very cutting edge of management in the late 2000s, 2010s and has continued rising until today, linked not only to the proliferation of companies and SE activities but also as a social phenomenon (Botsman and Rogers 2010 ). Thus, on the positive side, from 2010 onwards, there has been an explosion of research work, continuing to this day, which has increased the understanding of various consumer, business and government behaviors around the practices, production, and consumption derived from SE-businesses (Eckhardt et al. 2019 ; Hossain 2020 ). Despite this outburst, scholars have not fully agreed upon either a definition of the sharing economy or a framework to guide further research, and we continue to miss the ‘big’ picture. The problem seems to be that extant previous theoretical analyses of the SE have focused on analyzing transversal issues common to many SE activities, such as for example, examining the role of digital platforms (Sutherland and Jarrahi 2018 ), assessing the competitive effects (Zervas et al. 2017 ), or identifying the sustainability basis of the concept (Curtis and Lehner 2019 ). Thus, under the concept sharing economy, we find disconnected literature which prompts a floating state of the SE conceptual framework. Thus, although bibliometric (e.g. Filser et al. 2020 ; Kraus et al. 2020 ; Laurenti et al. 2019 ) and systematic (e.g. Curtis and Lehner 2019 ; Hossain 2020 ) review studies have been carried out in recent years that had helped to study the nature and scope of the SE, these works have focused mainly on studying this field from a quantitative exploration of published papers features, or on general analysis of extant literature in this field. As a step further, due to the fuzziness about the SE concept, present work aims to bring light on its conceptual underpinnings and evolution as scientific field based on a systematic literature review and qualitative analysis.

In this regard, this paper follows the call for context-specific research to understand what and how to study (Petigrew 2005 ), reviewing existing contributions and definitions (Sweeney et al. 2019 ). Thus, it is necessary to conduct a selected literature review that “summarizes the primary research, but each also goes further, providing readers with a strong organizational framework and careful analysis” (Cropanzano 2009 : p. 2009), providing a construct clarification to extant theory, and being a “unique opportunity for developing novel and engaging theoretical ideas and constructs, based on informed understandings of past research” (Post et al. 2020 : pp. 370–371).

Under this premise, several reasons support this study. Firstly, at an epistemological level we should consider whether we are facing the emergence of a new area of study. As Starbuck ( 2009 : p. 108) points out, “the social and behavioral sciences contain a myriad of conceptual and methodological fad sequences”. Beyond the constant search for novel topics, mass production of research, the search for generalizations, or disagreement on the validity of applicable theories and methods (Starbuck 2009 ), the diversity of approaches and disciplines applicable to a topic drives the approach to new questions and the incorporation of new methods and theories (Abrahamson 2009 ). The SE is not exempt from debates about its nature and functioning that may undermine it as an area of study or categorize it as just as a fad. Questions arise such as whether it is based on sharing versus exchange or giving (Belk 2010 ), whether a new consumer paradigm (Prothero et al. 2011 ), whether it generates competitive rivalry or not (Lamberton and Rose 2012 ), whether it is an opportunity for entrepreneurship (Bouncken et al. 2020 ; Cohen and Kietzmann 2014 ), whether it empowers innovation (Bouncken et al. 2020 ), whether it develops in bilateral or multilateral markets (Codagnone and Martens 2016 ), whether it is a new form of lobbying (Codagnone et al. 2016 ), or rather a manifestation of neoliberal capitalism (Martin 2016 ), whether it is prior to or a consequence of the Internet (Frenken and Schor 2017 ), whether it is an essentially technological concept (Puschmann and Alt 2016 ), whether it is a new business model (Kumar et al. 2018 ) and if yes, what exactly entails a sharing economy business model (Ritter and Schanz 2019 ), whether if SE businesses disrupt prevailing institutions (Zvolska et al. 2019 ), whether if customers are energetically looking for the social aspects of SE platforms as they go beyond the classic B2C offerings (Clauss et al. 2019 ), whether it allows to sell authentic experiences (Bucher et al. 2018 ), if it affects other existing activities (Zervas et al. 2017 ), if it requires legal changes (European Commission 2018 ; Smorto 2018 ), if trust is a requirement for implementation (Hawlitschek et al. 2018 ), if service providers are suppliers or employees (Hagiu and Wright 2019 ), or even if it should be considered as a path to sustainability (Curtis and Lehner 2019 ).

Secondly, it is a multidisciplinary area of study to which contributions have been made from many different areas, both academic (e.g., Laurenti et al. 2019 ) and professional (e.g., Deloitte 2016 ), institutional or legal (Smorto 2018 ), which has elicited a rich concept but, simultaneously, fragmented, diffuse, with terminological confusions (Curtis and Lehner 2019 ) and with an unanalyzed definitional dilemma (Hossain 2020 ). For the sake of theory development, the lacking of consensus requires a work of “tidying up” of definitions and concepts (Hirsch and Levin 1999 ).

Thirdly, from the theory development, the concept of SE traces a life-cycle in the process of consolidation with an intense variety and conceptual heterogeneity that is necessary to put in order (Hirsch and Levin 1999 ). Because of its relative novelty and broad scope, it can be considered an 'umbrella' concept (Belk 2014 ; Perren and Kozinets 2018 ), although future empirical evidence should provide specific validations.

Finally, the lack of consensus on the activities covered and the agents involved in the SE becomes an uphill climb to arrive at a shared definition. There are two reasons for this (Herbert and Collin-Lachaud 2017 ). First, the practices described within the SE “extremely varied, flourishing, constantly changing and subject to the fad effect” (p. 4). The second relates to the actors themselves: “Out of pragmatism, they do not impose specific criteria or boundaries on the transactions of the collaborative economy” (p. 4).

Therefore, our paper seeks to address these multiple disconnections by providing an integrated and novel conceptual framework that sheds light on potential theoretical development. With this aim, this study is carried out in three steps. First, a replicable process of identifying relevant SE definitions is conducted through a systematic literature review. Then, following the prior discussion of the terminology and definition proliferations, an interpretative analysis for disclosing underlying perspectives is carried out, contributing to the literature with an evolutionary framework of SE approaches. Finally, an SE definition is proposed, as well as a set of guidelines for future research avenues.

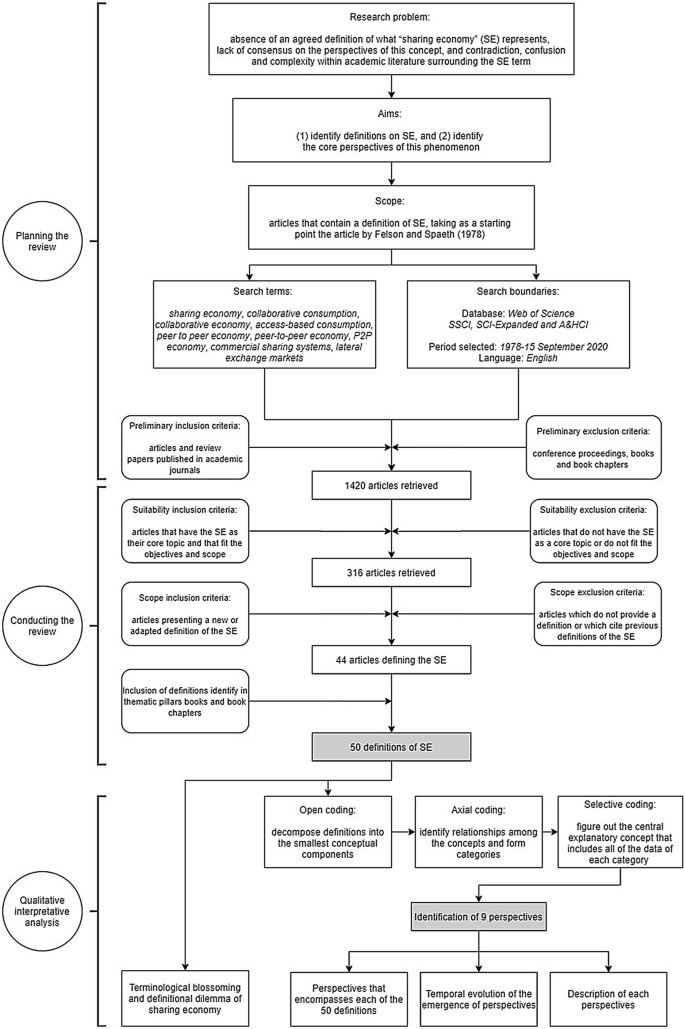

To find all the definitions that have been applied to the SE, a systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted. This approach enables any relevant studies to be selected and evaluated, ensuring a structured, rigorous and replicable literature review, as well as obtaining a more objective overview of the search results and eliminating any bias (Cropanzano 2009 ; Post et al. 2020 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ). This is one of the main differences of this methodology with respect to a traditional narrative review. To conduct the SLR, we based on Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) stages (see Fig. 1 ).

Analytical process implemented

2.1 Planning the review

Once identified the need for a review of the term “sharing economy” due to the great contradiction, confusion, and complexity surrounding it in the academic literature and its identity (Curtis and Lehner 2019 ; Hossain 2020 ), we state the research problem and the objectives, define the scope and establish a review protocol for our study considering the guidelines that will ensure the quality of the review (Snyder 2019 ; Sweeney et al. 2019 ). Accordingly, as search boundaries, the Web of Science Core Collection was chosen as database for this research, since it is recognized as the most important and longest standing database of academic papers (Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016 ; Vogel and Güttel 2012 ). The search period was limited to manuscripts published in English between 1978 and 15 September 2020, since it was in 1978 when the first article relating to SE appeared (cf. Felson and Spaeth 1978 ).

Following the review protocol, a keyword search template was developed to account for all possible SE-related terms. Thus, as suggested by previous articles (e.g., Curtis and Lehner 2019 ; Keathley-Herring et al. 2016 ), a scoping study was developed to select the search terms that would be used for the database search. Using the term “sharing economy” as a search query, the twenty most cited articles in the WoS database were analyzed to conduct our scoping. By examining these studies, the scoping study allowed us to detect seven related terms (sharing economy, collaborative consumption, collaborative economy, peer to peer economy, access-based consumption, commercial sharing systems, and lateral exchange markets), which were utilized to carry out the subsequent search.

Furthermore, as preliminary inclusion criteria, we filtered for articles and review papers published in academic journals due to their validated knowledge (Podsakoff et al. 2005 ), and therefore we excluded conference proceedings, books and book chapters due to the lack of clarity in the peer review processes and more restricted accessibility (Jones et al. 2011 ). However, considering the novelty and breadth of areas linked to the SE, those books that are thematic pillars of the field were checked along with this search (Dahlander and Gann 2010 ).

2.2 Conducting the review

The database search results returned 1420 articles (see Table 1 ).

From this point, the research followed 2 stages to ensure the purification of the database. In the first stage, title, abstract, and keywords were revised to determine their suitability for inclusion, taking into account the objectives and scope of this research. Articles that had the SE as their core topic and that fitted the objectives and scope met the criteria for inclusion for suitability, while articles that did not have the SE as a central theme or did not fit the objectives and scope, were excluded on grounds of unsuitability (Snyder 2019 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ). This stage ended with the exclusion of 1,104 articles, and the inclusion of 316 articles. Then, during the second phase, the full text of each of the articles considered relevant was examined to identify those articles that had a definition of the sharing economy, thus all articles that did not offer a definition or that used previously established definitions were excluded (scope inclusion/exclusion criteria). For this step, a predatory reading approach was taken, focusing on the main parts of each article where definitions in this area could be found (Curtis and Lehner 2019 ). As a result, a total of 44 articles that defined SE were obtained. Additionally, it was decided to include 6 definitions manually. These were found in thematic pillar books and were added as the definitions have been frequently cited in articles of great impact (Dahlander and Gann 2010 ). Therefore, our final sample included 50 documents that defined the SE.

2.3 Qualitative analysis

From this point, our unit of analysis comprised 50 definitions of the SE. Building on principles of thematic analysis, which is an interpretive synthesizing approach that enables a flexible and useful research approach to examine qualitative data (Braun and Clarke 2006 ) and that facilitates an improvement in the quality of literature reviews (Tranfield et al. 2003 ), we inductively identify, analyze and report patterns from the data, where our “data” are the definitions and the recognized patterns are the perspectives. Following the guidelines of Jones et al. ( 2011 ), the perspectives were not extracted from decontextualized information as is commonly done but rather we inducted and interpreted perspectives from our holistic understanding of each definition. The legitimacy for this approach is based on the entangled nature, relative youth, and rapid development of the vocabulary used in this scientific area. Furthermore, in thematic analysis patterns (in our case approaches) could be identified either at a semantic or at a latent level (Boyatzis 1998 ). At the semantic level, patterns are identified in the explicit and superficial meaning of the data, without looking beyond what is written, while in the latent approach the analyst goes beyond the semantic content of the data, and discovers the underlying ideas, presumptions, and concepts that are theorized to form the semantic content (Braun and Clarke 2006 ). In this way, we were able to identify both semantic and latent perspectives in the definitions of SE.

The thematic analysis was divided into 3 steps, namely open, axial, and selective coding (Gallicano 2013 ). During open coding, academics should read through the data several times and then begin to create tentative labels for pieces of data that summarize what they have seen (without the bias of existing theory and limiting their focus to the meaning that emerges from the data) (Corbin and Strauss 2015 ). Thus, we carefully examined all 50 definitions, decomposed them into the smallest conceptual components, and converted data into concepts. This first approximation resulted in a great number of finely grained concepts. Several sessions were needed to refine and group any similar concepts into the same category to reduce the number of units that should be further examined. Axial coding consists of identifying relationships from among the concepts of each category, i.e. to categorize findings and look for commonalities and differences. Thus, during this phase, we first ascertained the dominant concepts of each category and rearranged the data set to form an ontological organization of the domain (Jones et al. 2011 ). Redundant concepts were eliminated and the most representative concepts were selected. Then, as suggested by Corbin and Strauss ( 2015 ) we verified the internal cohesion, consistency, and differentiation of each dominant and dependent concept.

Finally, in the selective coding, researchers had to figure out the core concept that includes all of the data of each category and selectively code any data that relates to the key concept identified. Thus, in this step we examined all concepts of each category to determine the central explanatory concept; therefore, we refined categories by condensing or expanding their focus (Corbin and Strauss 2015 ). Iteration continued until we arrived at key categories with internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity. Key categories are understood as core components of a phenomenon (Kenny and Fourie 2015 ) and thus could be described as the perspectives under which a construct has been studied.

2.4 Organization of results

The systematic literature review ended with the identification of 50 SE definitions, and thematic analysis resulted in the discovery of 9 perspectives; these are economic efficiency , government of exchanges , technological , business model , consumer culture , environmental sustainability , social orientation , value creation, and production system . The collection of definitions has allowed us to examine the terminological blossoming, definitional dilemma, that is to say, to unmask the appearance of new similar terms and the development of these definitions. For its part, the identification of 9 perspectives allowed us to analyze how many of them are present in each of the definitions covered, to graph and examine the appearance of each perspective over time, and to establish a description of each one of them.

3 Conceptual contend: towards a life-cycle model of the SE

3.1 a terminological blossoming.

The SE concept has elicited a wide range of related terminology, energized by its use in diverse disciplines, and boosted by its rapid proliferation across industries. The SE concept was first coined and defined by Felson and Spaeth ( 1978 ) under the term ‘collaborative consumption’ which reflected the social origin of the concept and, in fact, this was the only recognized conception for 30 years. With renewed interest in this subject, and with a similar conception Benkler ( 2004 ) introduced and then Belk ( 2007 ) extended the term ‘sharing’. Subsequently, new approaches with an explicit extension of the scope of this field were introduced, generating, in turn, different terminologies. Therefore, ‘The mesh’ emerged as a term to account for a new logic of business (Gansky 2010 ), and other terms such as ‘access-based consumption’ (Bardhi and Eckhardt 2012 ) and ‘commercial sharing systems’ (Lamberton and Rose 2012 ) flourished with a sales and marketing orientation. Moreover, although the term ‘sharing economy’ appears in the literature on solidarity and economic geography (Gold 2004 ), Heinrichs ( 2013 ) applies the term ‘sharing economy’ in the context of sustainable exchanges. Additionally, the term ‘collaborative economy’ is introduced by Botsman ( 2014 ), while Schor and Fitzmaurice ( 2015 ) and Tussyadiah and Pesonen ( 2016 ) focus their definitions on the term ‘peer economy’, also ‘P2P economy’, or ‘economy of equals’.

However, the proliferation of terminology does not end here but has manifested itself with other nearby terms that have declined in frequency, such as ‘on-demand services’ or ‘services on demand’ (Benkler 2004 ), ‘on-demand economy’ (Cockayne 2016 ; Sundararajan 2017 ), ‘gig economy’ (Martin 2016 ), ‘temporary economy’ (Sundararajan 2013 ), ‘platform economy’ (Kenney and Zysman 2016 ), ‘crowdfunding’ (Belleflamme et al. 2014 ) or ‘gift economy’ (Cheal 1988 ). Other focused terms used are ‘microtask’, ‘microwork’, ‘micro-tasking’, or ‘micro-working’ (Sutherland and Jarrahi 2018 ). Besides, recently, the set of activities involving the SE has become generalized in economic terms as ‘lateral exchange markets’ (Perren and Kozinets 2018 ).

All this terminological flowering is a reflection of the SE becoming an umbrella term (Acquier et al. 2017 ; Ryu et al. 2019 ), and being confirmed as the most widespread term (Table 1 ).

3.2 A definitional dilemma

The conceptual history of the SE concept took off after the publication of an American Behavioral Scientist article by Felson and Spaeth ( 1978 ). They define collaborative consumption as “those events in which one or more persons consume economic goods or services in the process of engaging in joint activities with one or more others” (Felson and Spaeth 1978 : p. 614). Thus, the concept has its main roots in the human ecological theory of community structure and therefore has a strong social perspective. It is not until almost three decades later that Benkler ( 2004 ) takes it up again and redefines this concept, although maintaining the social perspective of it. Hereon, several additional attempts to define, characterize, or describe SE have been made during the last fifteen years. Thus, our systematic literature review allowed us to identify up to a total of 50 unique definitions of SE (see summary in Appendix ). This great diversity of definitions comes from many different perspectives, which also indicates an absence of an agreed definition of what SE represents.

To assess how these definitions have been adopted by academics, the citation count is analyzed. For the case of definitions published in WoS journals, the most relevant definitions are those contained in the works of Belk ( 2014 ), Hamari et al. ( 2016 ), and Bardhi and Eckhardt ( 2012 ). Moreover, the work of Frenken and Schor ( 2017 ), despite being relatively recent, receives a not insignificant number of citations. On the other side, from definitions contained in books, the most cited according to Google Scholar are Botsman and Rogers ( 2010 ), and Lessig ( 2008 ). The dilemma arises because the various definitions are different in nature, so opting for one or other of them implies unbalancing the ‘umbrella’ nature of the SE concept. Then, the concept can become conceptually asymmetrical, and therefore has brought with it the consequent loss of scope. So much so that an outstanding feature of the literature is that many works use the concept of the SE without explicitly defining it. However, while choosing one or the other supposes narrowing the meaning, this could ultimately formulate more specific problems.

It is undeniable that the conceptualizations of social science phenomena must possess a balance between generality, simplicity, and precision (Weick 1979 ). Undoubtedly, certain definitions have been relevant for the theoretical development of the SE by incorporating new routes to its understanding. However, by focusing mainly on particular perspectives, but leaving aside others, these definitions have gained in simplicity but sacrificed precision. Thus, most tend to be unspecific and at the same time too general. What is clear is that the most modern definitions cover more and more views, which brings us closer to a more precise definition, but while these definitions are promising, the SE remains confused and disconnected.

3.3 Perspectives contend: a life-cycle model of the SE

The multifaceted nature of the SE leads us to apply an interpretative synthesis approach (Braun and Clarke 2006 ) to the above set of definitions. Thus, 9 perspectives of the SE are uncovered in an inductive manner (Jones et al. 2011 ). Interpretation is carried out at semantic and latent levels (Boyatzis 1998 ). These nine routes are represented as distinctive characteristics within the definitions (Kenny and Fourie 2015 ) (see Table 2 ).

The perspectives are described as follows.

Economic efficiency : use of underutilized goods and services in the most rational way possible to avoid idle capacities.

Exchange governance : way in which the good or service is accessed (e.g. peer-to-peer) and the transaction is regulated (such as enhancing consumer rights, reducing information asymmetries, reinforcing trust in the other party, and reducing transaction costs).

Technological: an activity that is carried out through the intermediation of a technological platform, such as web 3.0.

Business model : generation of income for the person who cedes the use of the good or service and, therefore, a for-profit modality, unlike other modalities that are free.

Consumer culture : motivation that explains the consumption of a good or service only when it is needed, without this implying access to the property.

Environmental sustainability : more sustainable consumption practices as opposed to purely market-based exchanges, taking advantage of idle capacities and/or facilitating access to the property.

Social orientation : systems of social exchange rather than allocation through markets where there are a non-pecuniary motivation and social purpose.

Value creation : generation of some physical or non-monetary utility for the individual who demands the good or service (such as meeting people, having fun, saving time, consuming on-demand or for convenience and comfort).

Production system : production generation or a different mode of production.

The disruption of new perspectives has generated inflection points along with the concept life. Using an evolutionary framework (Hirsch and Levin 1999 ), and focusing on a semantic level, we develop a particularly distinctive evolution of the SE’s life through four different stages (see Fig. 2 ).

An evolutionary framework of SE perspectives (number of definitions)

The Inception period (1978–2008). The SE appears on the scene from a sociological perspective as a justification for events where people consume goods or services together/in a group (Felson and Spaeth 1978 ). However, despite the inception of the SE as an area of study in the late 1970s, this phenomenon did not attract any attention until almost three decades later, when Benkler ( 2004 ) takes up this idea by reopening the door for this phenomenon. The concept began to evolve, when Belk ( 2007 ) and Lessig ( 2008 ) explicitly highlight the perspective of consumer culture, by enhancing the non-proprietary access to these joint events. Thus, in a first period, although extensive in time, but scarce in terms of the number of contributions, the SE showed a clear and narrow focus on social orientation and consumer culture.

The Transition period (2009–2012). In the late 2000s and amid the global economic crisis, however, the concept of SE began to be investigated more seriously and its transition began. The foundation of companies like Airbnb (August 2008), Uber (March 2009) or the transformation of companies such as Couchsurfing to a for-profit entity (May 2011) brings with it the expansion of the perspectives of the SE, which it extends its range of essential routes to economic efficiency, new business models and the governance of exchanges (Botsman and Rogers 2010 ; Bardhi and Eckhardt 2012 ). Thus, Botsman and Rogers ( 2010 ) highlight how the SE helps to address the underutilization of assets and, therefore, their idle capacity. Bardhi and Eckardt ( 2012 ), stress the non-transfer of ownership, while Lamberton and Rose ( 2012 ) add the rivalry of consumers for limited choice, and Bardhi and Eckhardt ( 2012 ) and Lamberton and Rose ( 2012 ) are the first to introduce aspects related to the transaction itself and the governance of exchanges. Thus, the approaches that appeared in this period represented a promising advance in research on the SE, by suggesting a broader theoretical framework.

The Acceptance Excitement period (2013–2018). After this transition, the SE begins a period of acceptance that results in excitement to investigate this phenomenon from various perspectives and this ultimately leads to this area receiving 21 definitions in just 6 years. This period involves the acceptance of the five perspectives already established in the two previous periods (cf. Aloni 2016 ; Frenken and Schor 2017 ; Perren and Kozinets 2018 ), but also continues to nurture the concept of SE with two new perspectives. To such an extent the multiple perspectives of the concept can be appreciated in the definition provided by Schor and Fitzmaurice ( 2015 ), which includes the most common ones up to that moment, such as consumer culture, governance of exchanges, social orientation, and economic efficiency, in addition to the business model perspective, which is somewhat less common. However, with the arrival of web 3.0. in the early 2010s, the emergence of smartphones, mobile applications, the Internet of things, and big data which it brought with it and the rapid adoption of these by SE businesses (for example, Uber launched its mobile app in late 2011 and Airbnb in late 2012), almost immediately brought the inclusion of technology (digital platforms) as an essential feature of the SE definitions (cf. Hamari et al. 2016 ; Heinrichs 2013 ). Likewise, Tussyadiah and Pesonen ( 2016 ) add for the first time production systems as a new perspective of the SE, which, however, still lacks development. While several perspectives were accentuated during this period, the addition of new ones and the great emergence of definitions resulted in a large but disconnected multifaceted area.

The Maturity Challenge period (2019 to date). Finally, starting in 2019 and once the period of acceptance excitement has ended, a period of maturity challenge begins, where new essential perspectives appear that reflect new analysis trends and that expand the range of the SE, as is the case of environmental sustainability and value creation. Thus, Curtis and Lehner ( 2019 ) introduce in their definition the shared practices that promote sustainable consumption in the face of growing concern about sustainability and environmental impact. On the other hand, Dellaert ( 2019 ) write from the value creation perspective to denote the non-monetary demands that consumers expect to receive when using SE goods or services (e.g., meeting people or having fun). Eckhardt et al. ( 2019 ), without adding any new perspectives, reflect the importance of previous perspectives such as consumer culture and the technological aspect surrounding the SE. The most significant changes in this period are consolidation of SE as business model, the concern for the sustainability, the relevance of the social orientation and the takeoff of the value creations and production system perspectives.

And finally, in this process of challenging the maturity of the concept, Akhmedova et al. ( 2020 ), Curtis and Mont ( 2020 ) and Zmyślony et al. ( 2020 ) propose the broadest and most ambitious definitions that this area has received, incorporating seven out 9 existing perspectives. Despite these theoretical efforts, the field still possesses great complexities, contradictions, and confusion, therefore it is undoubtedly time for a period of maturity challenge, where the SE is delineated, and the doors are opened to more organized research that starts from a strong theoretical framework.

The 9 approaches differ in the number of times they have been used to define the SE, varying from the most common perspectives such as technological, consumer culture, and government of exchanges, occurring in 37, 36, and 36 definitions respectively, to those that have a huge discontinuity, such as value creation, the production system, and environmental sustainability, occurring in 4, 8, and 10 definitions, respectively. The other three perspectives, which are less commonly used, are the business model (29 occurrences), economic efficiency (25 occurrences), and social orientation (21 occurrences). Not a single definition includes more than seven perspectives (cf. Akhmedova et al. 2020 ; Curtis and Mont 2020 or Zmyślony et al. 2020 ), which shows the existence of not complete definitions for the SE.

4 Discussion and conclusions

SE is an umbrella concept, of which 50 different definitions have been identified through a systematic literature review. These have been associated with various root terms (access-based consumption, collaborative economy, commercial sharing systems, sharing economy, collaborative consumption, peer to peer economy, and lateral exchange markets). Considering the fuzziness of the term, the terminology analysis reveals there is a dominant root term, namely, sharing economy , and three followers, specifically collaborative consumption , collaborative economy , and access-based consumption . Thus, it could be argued that there exists a denotative neologism with the term sharing economy , for its use as Jack of all trades. From a linguistic point of view, this use is justified, because it is the term mostly used in media, social networks, and even by the Internet platforms to refer to themselves (e.g., Airbnb calls itself a ‘home-sharing service’). This, in turn, has led to it being the most widely used term in academia (see Table 1 ) when referring to collaborative practices. Thus, one would have to ask whether the term SE is used more for popularity than for precision and consequently if there exist terms that are more accurate but less popular for each specific activity that involves collaborative practices. In this regard, we propose that a term such as collaborative economy is more appropriate when referring to the economic efficiency of the term, access-based consumption better captures the consumer’s perspective, collaborative consumption could be more accurate to refer to the social nature of the concept, lateral market exchanges gathers the technological framework of such exchanges, commercial sharing systems is more precise when referring to the governance of exchanges present in the sharing economy, and peer-to-peer focus more on the open nature of actors.

In a second step, a qualitative interpretative analysis of the definitions has shown the multifaceted nature of the SE, with fragmented insights from different fields. As a result of this analysis, and as a contribution to the literature, an evolutionary life framework of SE approaches through four different stages is proposed. The disclosed approaches are economic efficiency , government of exchanges , technological , business model , consumer culture , environmental sustainability , social orientation , value creation, and production system . The analysis has not been limited to identifying perspectives, but also semantic and latent layers have been stated. The proposed evolutionary life framework shows how these approaches have appeared throughout the academic and professional life of the SE. It explains how in the first incipient period (1978–2008) the SE was born from a sociological point of view, going through a period of transition (2009–2012) with the arrival of the world economic crisis and the emergence of new business models (e.g., Airbnb or Uber), extending its focus in a period of excitement of acceptance (2013–2018) with the arrival of the technological irruption and with the growing research on this phenomenon from various scientific areas, until reaching the current state (2019 to date) of challenge of maturity, a period in which it is necessary to focus on particular concerns of the SE.

The study also reveals the existence of a conceptual dilemma, in which specific positions can contribute to gaining depth in the area of study, but at the cost of sacrificing generality and precision. Therefore, findings evidence the need for a more balanced definition (Weick 1979 ). As a consequence, a new definition of SE is proposed by including a comprehensive view of its nature.

The SE is understood as business, production, and consumption sustainable practices as value creation systems, which are based on temporary use of underutilized assets, for free or for a fee, usually supported by digital platforms and peer communities .

Thus, in response to Acquier’s ( 2017 ) statement that academics will probably never agree on a definition of the SE since it is seen as an umbrella construct and is essentially controversial, this definition indeed encompasses its rich nature. In this way, we intend to contribute to the literature with a definition that can be used by academics regardless of their research position.

Several discussion matters, research gaps, and future research lines emanate from this work. From a conceptual point of view, the SE concept has been evolving over the years, since although it was born with an initial conception based mainly on social orientation, the most outstanding approaches have been as consumer culture, technological, and government of exchanges. Thus, this concept has been expanding its dimensionality, incorporating, in addition to the previous perspectives, an orientation towards the business model, sustainability, and economic efficiency. So much so, that the SE can be considered a vision of the organization of exchanges, alternative production system, and consumption articulated on various interpretations. This in turn suggests a paradigmatic configuration on a set of metaphors or perspectives, which leads to the consideration that the SE can be seen as a paradigm in the economy (Arndt 1985 ). In this sense, it would be desirable to investigate what is the trend of the SE in that square framework formed by the economic, social, sustainable, and technological aspects of the SE. Consequently, it would be relevant to examine towards which direction the SE is oriented, even more so given the crisis currently caused by the COVID-19. In this context, several SE-companies (e.g. Airbnb) have already suffered a strong economic impact (BBC News 2020 ) and the future of SE companies is, therefore, being questioned. In this sense, the debate on policy-making about whether this type of company should be supported and promoted at an institutional level due to its sustainability and social benefits takes on special relevance (Codagnone and Martens 2016 ).

Furthermore, as one of the main contributions of this study is the disclosure of approaches and the identification of the existence of these approaches in each definition both in a semantic and latent way, this research can be a gateway for SE operationalization. In this way, as the SE is a growing area of research, the theoretical contribution of this study opens the doors to academics from a wide range of research areas to new perspectives to guide their research on SE. It is important to build a conceptual framework that explains the development of SE-businesses from the components identified in the literature. Thus, further research derived from this work evidences the need to empirically corroborate and contrast in practice the perspectives proposed in this study, thereby empirically testing a neglected area. Above all, the research needs to focus on specific problems of the SE. e.g., the governance of SE companies, the image these companies have, and the problems and conflicts regarding legal issues. Likewise, since SE businesses are mainly linked to services (Bardhi and Eckhardt 2012 ; Hossain 2020 ), it would be relevant to delve more deeply into its applicability and viability in the production of goods.

Finally, from a practical point of view, this article offers individual consumers, service providers, regulatory authorities, companies in traditional sectors and SE companies, a holistic introduction to the essential qualities of collaborative business.

This study is not exempt from some limitations. First, it only uses articles from academic journals indexed in the Web of Science database, leaving out other databases (e.g., Scopus) as well as grey literature. Secondly, as in any review work, the parameters for inclusion and exclusion of articles influence the results. Thirdly, for the identification of perspectives an interpretative qualitative approach was used, therefore as mentioned above it would be of interest to obtain empirical contributions that corroborate the proposals included in this research.

Abrahamson E (2009) Necessary conditions for the study of fads and fashions in science. Scand J Manag 25:235–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2009.03.005

Article Google Scholar

Acquier A, Daudigeos T, Pinkse J (2017) Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: an organizing framework. Technol Forecast Soc Change 125:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.006

Akhmedova A, Mas-Machuca M, Marimon F (2020) Value co-creation in the sharing economy: the role of quality of service provided by peer. J Clean Prod 266:121736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121736

Aloni E (2016) Pluralizing the sharing economy. Wash Law Rev 91:1397

Google Scholar

Arndt J (1985) On making marketing science more scientific: role of orientations, paradigms, metaphors, and puzzle solving. J Mark 49:11–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298504900302

Arvidsson A (2018) Value and virtue in the sharing economy. Sociol Rev 66:289–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118758531

Bardhi F, Eckhardt GM (2012) Access-based consumption: the case of car sharing. J Consum Res 39:881–898. https://doi.org/10.1086/666376

Barnes SJ, Mattsson J (2016) Understanding current and future issues in collaborative consumption: a four-stage Delphi study. Technol Forecast Soc Change 104:200–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.01.006

BBC News (2020) Air bnb cuts 25% of staff amid travel downturn. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52553001 . Accessed 27 May 2020

Belk R (2007) Why not share rather than own? Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 611:126–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206298483

Belk R (2010) Sharing. J Consum Res 36:715–734. https://doi.org/10.1086/612649

Belk R (2014) You are what you can access: sharing and collaborative consumption online. J Bus Res 67:1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

Belleflamme P, Lambert T, Schwienbacher A (2014) Crowdfunding: tapping the right crowd. J Bus Ventur 29:585–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.003

Benkler Y (2004) Sharing nicely: on shareable goods and the emergence of sharing as a modality of economic production. Yale Law J 114:273

Berg L, Slettemeås D, Kjørstad I, Rosenberg TG (2020) Trust and the don’t-want-to-complain bias in peer-to-peer platform markets. Int J Consum Stud 44:220–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12561

Botsman R (2014) Sharing’s not just for start-ups. Harv Bus Rev 92:23–25

Botsman R, Rogers R (2010) What’s mine is yours: the rise of collaborative consumption. Harper Collins, New York

Bouncken R, Ratzmann M, Barwinski R, Kraus S (2020) Coworking spaces: empowerment for entrepreneurship and innovation in the digital and sharing economy. J Bus Res 114:102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.033

Bouncken RB, Reuschl AJ (2018) Coworking-spaces: how a phenomenon of the sharing economy builds a novel trend for the workplace and for entrepreneurship. Rev Manag Sci 12:317–334

Boyatzis RE (1998) Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bucher E, Fieseler C, Fleck M, Lutz C (2018) Authenticity and the sharing economy. Acad Manag Discov 4:294–313. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2016.0161

Cheal D (1988) The gift economy. Routledge, London

Clauss T, Harengel P, Hock M (2019) The perception of value of platform-based business models in the sharing economy: determining the drivers of user loyalty. Rev Manag Sci 13:605–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0313-0

Cockayne DG (2016) Sharing and neoliberal discourse: the economic function of sharing in the digital on-demand economy. Geoforum 77:73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.10.005

Codagnone C, Biagi F, Abadie F (2016) The passions and the interests: unpacking the ‘sharing economy. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC101279/jrc101279.pdf

Codagnone C, Martens B (2016). Scoping the sharing economy: origins, definitions, impact and regulatory issues. Institute for prospective technological studies digital economy working paper

Cohen B, Kietzmann J (2014) Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organ Environ 27(3):279–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026614546199

Corbin J, Strauss A (2015) Basics of qualitative research. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Cropanzano R (2009) Writing nonempirical articles for journal of management: general thoughts and suggestions. J Manag 35:1304–1311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309344118

Curtis SK, Lehner M (2019) Defining the sharing economy for sustainability. Sustainability 11:567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030567

Curtis SK, Mont O (2020) Sharing economy business models for sustainability. J Clean Prod 266:121519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121519

Dahlander L, Gann DM (2010) How open is innovation? Res Policy 39:699–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.013

Davlembayeva D, Papagiannidis S, Alamanos E (2019) Mapping the economics, social and technological attributes of the sharing economy. Inf Technol People 33:841–872. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-02-2018-0085

Dellaert BGC (2019) The consumer production journey: marketing to consumers as co-producers in the sharing economy. J Acad Mark Sci 47:238–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-018-0607-4

Deloitte (2016) The rise of the sharing economy impact on the transportation space. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/consumer-business/us-cb-the-rise-the-sharing-economy.pdf . Accessed 22 March 2020

Eckhardt GM, Houston MB, Jiang B et al (2019) Marketing in the sharing economy. J Mark 83:5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919861929

eMarketer (2019) US sharing economy users, 2017–2022. Retrieved from eMarketer database. https://www.emarketer.com/chart/229768/us-sharing-economy-users-2017-2022-millions . Accessed 16 March 2020

European Commission (2016) Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions: a European agenda for the collaborative economy. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9911-2016-INIT/en/pdf . Accessed 25 March 2020

European Commission (2017) Exploratory study of consumer issues in peer-to-peer platform markets. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/document.cfm?doc_id=45245 . Accessed 15 March 2020.

European Commission (2018) Study to monitor the business and regulatory environment affecting the collaborative economy in the EU. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/79bee7ad-6d22-11e8-9483-01aa75ed71a1 . Accessed 14 March 2020

Fahmy H (2020) Is the sharing economy causing a regime switch in consumption? J Appl Econ 23:281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/15140326.2020.1750121

Felson M, Spaeth JL (1978) Community structure and collaborative consumption: a routine activity approach. Am Behav Sci 21:614–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276427802100411

Fielbaum A, Tirachini A (2020) The sharing economy and the job market: the case of ride-hailing drivers in Chile. Transportation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-020-10127-7

Filser M, Tiberius V, Kraus S, Spitzer J, Kailer N, Bouncken RB (2020) Sharing economy: A bibliometric analysis of the state of research. Int J Entreprenurial Ventur. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2020.10031491

Frenken K, Schor J (2017) Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environ Innov Soc Transit 23:3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.01.003

Gallicano TD (2013) Relationship management with the Millennial generation of public relations agency employees. Public Relat Rev 39:222–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.03.001

Gansky L (2010) The mesh: why the future of business is sharing. Penguin, New York

Gao P, Li J (2020) Understanding sustainable business model: a framework and a case study of the bike-sharing industry. J Clean Prod 267:122229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122229

Gerwe O, Silva R (2020) Clarifying the sharing economy: conceptualization, typology, antecedents, and effects. Acad Manag Perspect 34:65–96. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0010

Gold L (2004) The sharing economy: solidarity networks transforming globalisation. Ashgate, Aldershot

Govindan K, Shankar KM, Kannan D (2020) Achieving sustainable development goals through identifying and analyzing barriers to industrial sharing economy: a framework development. Int J Prod Econ 227:107575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.107575

Guyader H, Piscicelli L (2019) Business model diversification in the sharing economy: the case of gomore. J Clean Prod 215:1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.114

Habibi MR, Davidson A, Laroche M (2017) What managers should know about the sharing economy. Bus Horiz 60:113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.09.007

Hagiu A, Wright J (2019) The status of workers and platforms in the sharing economy. J Econ Manag Strat 28:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12299

Hamari J, Sjöklint M, Ukkonen A (2016) The sharing economy: why people participate in collaborative consumption. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 67:2047–2059. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23552

Hawlitschek F, Notheisen B, Teubner T (2018) The limits of trust-free systems: a literature review on blockchain technology and trust in the sharing economy. Electron Commer Res Appl 29:50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2018.03.005

Hazée S, Zwienenberg TJ, Van Vaerenbergh Y, Faseur T, Vandenberghe A, Keutgens O (2020) Why customers and peer service providers do not participate in collaborative consumption. J Serv Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/josm-11-2018-0357

Heinrichs H (2013) Sharing economy: a potential new pathway to sustainability. GAIA 22:228–231

Herbert M, Collin-Lachaud I (2017) Collaborative practices and consumerist habitus: an analysis of the transformative mechanisms of collaborative consumption. Rech Appl Mark 32:40–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/2051570716678736

Hirsch PM, Levin DZ (1999) Umbrella advocates versus validity police: a life-cycle model. Organ Sci 10:199–212. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.2.199

Hossain M (2020) Sharing economy: a comprehensive literature review. Int J Hosp Manag 87:102470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102470

Huang SL, Kuo SY (2020) Understanding why people share in the sharing economy. Online Inf Rev 44:805–825. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-03-2017-0073

Jones MV, Coviello N, Tang YK (2011) International entrepreneurship research (1989–2009): a domain ontology and thematic analysis. J Bus Ventur 26:632–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.04.001

Kathan W, Matzler K, Veider V (2016) The sharing economy: your business model’s friend or foe? Bus Horiz 59:663–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.06.006

Keathley-Herring H, Van Aken E, Gonzalez-Aleu F et al (2016) Assessing the maturity of a research area: bibliometric review and proposed framework. Scientometrics 109:927–951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2096-x

Kenney M, Zysman J (2016) The rise of the platform economy. Issues Sci Technol 32:61–69

Kenny M, Fourie R (2015) Contrasting classic, straussian, and constructivist grounded theory: methodological and philosophical conflicts. Qual Report 20:1270–1289

Kim B, Kim D (2020) Attracted to or locked in? Explaining consumer loyalty toward Airbnb. Sustainability 12:2814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072814

Kraus S, Li H, Kang Q, Westhead P, Tiberius V (2020) The sharing economy: a bibliometric analysis of the state-of-the-art. Int J Entrepreneurial Behav Res (ahead-of-print)

Kumar V, Lahiri A, Dogan OB (2018) A strategic framework for a profitable business model in the sharing economy. Ind Mark Manag 69:147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.08.021

Lamberton CP, Rose RL (2012) When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. J Mark 76:109–125. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.10.0368

Laurenti R, Singh J, Cotrim JM et al (2019) Characterizing the sharing economy state of the research: a systematic map. Sustainability 11:5729. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205729

Lee SH (2020) New measuring stick on sharing accommodation: guest-perceived benefits and risks. Int J Hosp Manag 87:102471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102471

Lessig L (2008) Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. Penguin Press, New York

Book Google Scholar

Martin CJ (2016) The sharing economy: a pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecol Econ 121:149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.027

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A (2016) The journal coverage of web of science and scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106:213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Muñoz P, Cohen B (2017) Mapping out the sharing economy: a configurational approach to sharing business modeling. Technol Forecast Soc Change 125:21–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.035

Paik Y, Kang S, Seamans R (2019) Entrepreneurship, innovation, and political competition: how the public sector helps the sharing economy create value. Strateg Manag J 40:503–532. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2937

Perren R, Kozinets RV (2018) Lateral exchange markets: how social platforms operate in a networked economy. J Mark 82:20–36. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.14.0250

Pettigrew AM (2005) The character and significance of management research on the public services. Acad Manag J 48:973–977. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.19573101

Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Bachrach DG, Podsakoff NP (2005) The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strateg Manag J 26:473–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.454

Post C, Sarala R, Gatrell C, Prescott JE (2020) Advancing theory with review articles. J Manag Stud 57:351–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12549

Prothero A, Dobscha S, Freund J, Kilbourne WE, Luchs MG, Ozanne LK, Thøgersen J (2011) Sustainable consumption: opportunities for consumer research and public policy. J Public Policy Mark 30:31–38. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.30.1.31

Puschmann T, Alt R (2016) Sharing economy. Bus Inf Syst Eng 58:93–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-015-0420-2

Ritter M, Schanz H (2019) The sharing economy: a comprehensive business model framework. J Clean Prod 213:320–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.154

Ryu H, Basu M, Saito O (2019) What and how are we sharing? a systematic review of the sharing paradigm and practices. Sustain Sci 14:515–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0638-2

Sanasi S, Ghezzi A, Cavallo A, Rangone A (2020) Making sense of the sharing economy: a business model innovation perspective. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 32:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2020.1719058

Schor J, Fitzmaurice C (2015) Collaborating and connecting: the emergence of the sharing economy. In: Reisch L, Thogersen J (eds) Handbook of research on sustainable consumption. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 410–425

Shaheen SA, Chan ND, Gaynor T (2016) Casual carpooling in the San Francisco Bay Area: understanding user characteristics, behaviors, and motivations. Transp Policy 51:165–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.01.003

Smorto G (2018) Protecting the weaker parties in the platform economy. In: Davidson NM, Finck M, Infranca J (eds) The Cambridge handbook of the law of the sharing economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 431–446

Snyder H (2019) Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 104:333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Starbuck WH (2009) Cognitive reactions to rare events: perceptions, uncertainty, and learning. Organ Sci 20:925–937. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0440

Stephany A (2015) The business of sharing: making it in the new sharing economy. Springer, Berlin

Sundararajan A (2013) From zipcar to the sharing economy. Harvard business review, 1. https://hbr.org/2013/01/from-zipcar-to-the-sharing-eco . Accessed 12 April 2020

Sundararajan A (2017) The sharing economy: the end of employment and the rise of crowd-based capitalism. MIT Press, Cambridge

Sutherland W, Jarrahi MH (2018) The sharing economy and digital platforms: a review and research agenda. Int J Inf Manage 43:328–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.07.004

Sweeney A, Clarke N, Higgs M (2019) Shared leadership in commercial organizations: a systematic review of definitions, theoretical frameworks and organizational outcomes. Int J Manag Rev 21:115–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12181

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management Knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14:207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

Tussyadiah IP, Pesonen J (2016) Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. J Travel Res 55:1022–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515608505

U.S. department of the treasure (2019) The sharing economy and impact on the tax gap. https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/files/prompt-payment/July-December2019FR.pdf . Accessed 15 March 2020

Vogel R, Güttel WH (2012) The dynamic capability view in strategic management: a bibliometric review. Int J Manag Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12000

Wang X, Wang W, Chai Y, Wang Y, Zhang N (2019) E-book adoption behaviors through an online sharing platform: a multi-relational network perspective. Inf Technol People 33:1011–1035. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-10-2018-0482

Weick KE (1979) The social psychology of organizing. McGraw Hill, New York

Wu J, Si S, Yan H (2020) Reducing poverty through the shared economy: creating inclusive entrepreneurship around institutional voids in China. Asian Bus Manag. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-020-00113-3

Yu C, Xu X, Yu S, Sang Z, Yang C, Jiang X (2020) Shared manufacturing in the sharing economy: concept, definition and service operations. Comput Ind Eng 146:106602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2020.106602

Zervas G, Proserpio D, Byers JW (2017) The rise of the sharing economy: estimating the impact of airbnb on the hotel industry. J Mark Res 54:687–705. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0204

Zmyślony P, Leszczyński G, Waligóra A, Alejziak W (2020) The sharing economy and sustainability of Urban destinations in the (over) tourism context: the social capital theory perspective. Sustainability 12:2310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062310

Zvolska L, Voytenko-Palgan Y, Mont O (2019) How do sharing organisations create and disrupt institutions? Towards a framework for institutional work in the sharing economy. J Clean Prod 219:667–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.057

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics and Business, CIMEDES Research Center, University of Almeria, Carretera de Sacramento, s/n, 04120, Almeria, Spain

Manuel Sánchez-Pérez, Nuria Rueda-López, María Belén Marín-Carrillo & Eduardo Terán-Yépez

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Manuel Sánchez-Pérez .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See Table 3

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Sánchez-Pérez, M., Rueda-López, N., Marín-Carrillo, M.B. et al. Theoretical dilemmas, conceptual review and perspectives disclosure of the sharing economy: a qualitative analysis. Rev Manag Sci 15 , 1849–1883 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00418-9

Download citation

Received : 17 June 2020

Accepted : 21 October 2020

Published : 26 October 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00418-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sharing economy

- Systematic literature review

- Qualitative interpretative analysis

- Theory development

- Umbrella concept

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.7(10); 2021 Oct

A decade of systematic literature review on Airbnb: the sharing economy from a multiple stakeholder perspective

Associated data.

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Airbnb, which launched its business in 2009, has experienced explosive growth by creating value through the sharing economy business model. The Airbnb business model helps property owners exploit underutilized assets. However, along with its rapid growth, controversies have arisen among many stakeholders, especially the traditional hotel industry, communities, and policymakers. This study reviews academic articles to pinpoint the factors involved in the relationships among Airbnb and its multiple stakeholders. The aim is to identify the benefits, drawbacks, and issues surrounding Airbnb. The analysis is based on the perspectives of six Airbnb stakeholders: guests, hosts, employees, communities, competitors, and policymakers. A variety of scholarly journals indexed in the Scopus database were reviewed, with 282 included in the final analysis. The analysis will be useful for academics, practitioners, and policymakers alike, as it summarizes the Airbnb relevant actors, identifies key factors that influence stakeholder behavior, and assesses the power and level of influence of each stakeholder. Ultimately, the study points to potential directions for future research on Airbnb.

Airbnb; literature review; stakeholder; guest; host; employee; community; competitor; policymaker.

1. Introduction

Within a few years of its inception in 2009, Airbnb had become one of the most successful sharing economy platforms. Roelofsen and Minca (2018) report that as of 2017, Airbnb had attracted 100 million hosts and guests worldwide, earning $100 million that year. The company has developed its business model based on a compelling value proposition. It integrates economic benefits for travelers and residents of tourist areas via a trusted marketplace that enables the platform to scale up and leverage its assets through network utilization ( Cheng and Foley, 2018 ; Leoni, 2020 ; Oskam and Boswijk, 2016 ).

Airbnb offers many benefits to its stakeholders. For customers, Airbnb accommodation is typically cheaper than traditional accommodation like a hotel ( Guttentag, 2015 ; Gyódi, 2019 ; Varma et al., 2016 ). In addition, Airbnb offers local authenticity ( Bucher et al., 2018 ), giving customers the opportunity to live like locals in a listed apartment, house, or private room ( Gurran and Phibbs, 2017 ; Lin et al., 2019 ; Paulauskaite et al., 2017 ). For property owners, Airbnb enables them to maximize the utilization of their underutilized assets ( Ferreri and Sanyal, 2018 ; Oskam and Boswijk, 2016 ). For other stakeholders, such as the community, Airbnb increases community economic and business opportunities ( Gurran and Phibbs, 2017 ; Petruzzi et al., 2020 ).

Despite the advantages that Airbnb offers, some have been on the receiving end of the negative externalities that Airbnb's growth has brought about. For example, one hotel in Texas experienced a revenue loss for every increase in Airbnb property listings ( Dogru et al., 2019 ; Varma et al., 2016 ; Zervas et al., 2017 ). Tourist sites have also been subjected to negative externalities based on the increased concentration of tourists in particular spots, which invites environmental problems such as water scarcity, waste management, and carbon emission issues ( Cheng et al., 2020a , Cheng et al., 2020 ; Martín et al., 2018 ). The problems created by Airbnb as a shared economy accommodation have also generated challenges for the government as a regulator because Airbnb's disruption of the accommodation industry has changed the tourism landscape, creating taxation problems and discrimination problems, among others ( Guttentag, 2015 ; Interian, 2016 ; Ključnikov et al., 2018 ). Many conceptual and empirical studies have discussed these issues from the stakeholders' perspective that include the guests ( Pinottti and Moretti, 2018 ; Sthapit and Björk, 2019 ), hosts ( Ert et al., 2016 ), competitors ( Forgacs and Dimanche, 2016 ; Ginindza and Tichaawa, 2019 ; Horodnic et al., 2016 ), communities ( Midgett et al., 2017 ; Roelofsen and Minca, 2018 ), and the government ( Ključnikov et al., 2018 ; Schäfer and Braun, 2016 ).

To date, there are several literature reviews that discuss peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation in general ( Belarmino and Koh, 2020 ; Dolnicar, 2019 , 2020 ; Prayag and Ozanne, 2018 ; Sainaghi, 2020 ) and four literature reviews that address Airbnb specifically ( Dann et al., 2019 ; Guttentag, 2019 ; Medina-Hernandez et al., 2020 ; Ozdemir and Turker, 2019 ).

Our study uses a literature review approach as well. However, unlike the study of Dann et al. (2019) —which discusses the motives of hosts and guests, the role of trust and reputation, price calculation, and legal aspects—our study is based on stakeholder theory. We structure our study around this theory as it brings an ethical aspect to management decision making ( Goodpaster, 1991 ). The ethical issue is relevant as ethics is a theme that remains underexplored in the research related to the sharing economy ( Andreu et al., 2020 ).

Based on stakeholder theory, as suggested by Reed et al. (2009) , our study is framed around three questions: (1) who are the stakeholders of Airbnb? (2) what are their interests/concerns? and (3) how much power and influence does each stakeholder have? We expect our results to generate knowledge about the relevant Airbnb actors and to provide a comprehensive understanding of the Airbnb phenomenon, identifying key factors that influence the behavior of its stakeholders, assessing the influence and level of impact of each stakeholder, and exploring the research based on the perspective of Airbnb. As a business entity, Airbnb can use the information to improve stakeholder decision making that incorporates ethical considerations. Further, the study can offer insights to government when considering the feasibility of future policy directions.

2. Literature review

2.1. the sharing economy of airbnb.

The sharing economy is sometimes called the “collaborative economy” ( Calo and Rosenblat, 2017 ). The term refers to online network-based activities that provide temporary access to a good to facilitate more efficient use of physical assets. It depends on trust and the capability of operating at a near-zero marginal cost ( Frenken et al., 2015 ; Hawlitschek et al., 2018 ; Ranjbari et al., 2018 ; Uzunca and Borlenghi, 2019 ). Gerwe and Silva (2020) generalize the definition of the sharing economy to be a socioeconomic system that allows peers to grant temporary access to underutilized physical and human assets via an online platform. This socioeconomic system definition captures that the sharing economy can cover both fee-based and non-fee-based transactions ( Gerwe and Silva, 2020 ). The sharing economy offers both advantages and disadvantages to its stakeholders. As a platform, it provides greater flexibility, fair compensation, match-making, an extended reach, trust building, and collectivity in the sharing and collaborative exchange among actors ( Hawlitschek et al., 2018 ; Sutherland and Jarrahi, 2018 ). Some scholars also see the sharing economy as a wealth redistribution method ( Rifkin, 2014 ) with some benefits for society. Despite being acknowledged as an innovation that decentralizes and disrupts the existing socio-technical and economic regimes, the sharing economy may be accused of being a "neoliberal system on steroids" as well ( Martin, 2016 ; Murillo et al., 2017 ).

In the hospitality industry, Servas International pioneered the concept of the sharing economy in 1994, followed by CouchSurfing in 2003, and Airbnb in August 2008 ( Gerwe and Silva, 2020 ; Johnson and Neuhofer, 2017 ). Couchsurfing represents a non-fee-based transaction, while Airbnb represents a fee-based transaction in the sharing economy ( Gerwe and Silva, 2020 ). However, among these three shared accommodation platforms, Airbnb has been the most successful, as it offers a more distinctive service quality and a more local experience than traditional accommodations do ( Mody et al., 2017 ; Varma et al., 2016 ).

Since its inception more than a decade ago, Airbnb has experienced explosive growth. As of April 2019, Airbnb was available in more than 1,000 cities across the world and was expected to have served more than 500 million guests ( Airbnb, 2019a ). Airbnb has also gained public trust, reflected in the 250 million reviews it has received from both guests and hosts as of 2019 ( Airbnb, 2019a ). In 2018, Airbnb had a market valuation of nearly $31 billion, $2.6 billion in profit, and $93 million in revenue ( Bloomberg, 2019 ).

2.2. Stakeholder analysis

Donaldson and Preston (1995 , p. 67) define stakeholders as “persons or groups with legitimate interests in procedural and substantive aspects of corporate activity. Stakeholders are recognized by their interests in the corporation, whether the corporation has any related functional interest in them.” According to these authors, a group is qualified as a stakeholder if it has a legitimate interest in an aspect of the organization's activities. Such groups can consist of customers, employees, investors, suppliers, communities, governments, trade associations, and political groups. Thus, stakeholders are those who have the power to affect organizational performance and/or have a stake in the organization's performance ( Reed et al., 2009 ). Without the support of stakeholders, a company could not exist.

Stakeholder theory addresses business ethics, morals, and values when managing stakeholders involved with a project or organization ( Freeman et al., 2004 ). The theory is beneficial for any platform-based business in managing synergies and cooperation among its stakeholders to capture value and maintain business sustainability ( Laczko et al., 2019 ). However, it is worth noting that given the different stakeholder interests in a business, it is inescapable that conflicts will arise among them ( Harrison and Wicks, 2013 ). By analyzing how each stakeholder is positively and/or negatively impacted by the organization, the organization can gain alignment among all stakeholder goals and address conflicts early on to create better value for the range of its constituents ( Freeman et al., 2012 ).

2.3. Literature review on Airbnb

A literature review is a comprehensive summary and critical analysis of existing relevant academic and non-academic literature on the topic under review, conducted as objectively as possible ( Cronin et al., 2008 ; Linde and Willich, 2003 ; Rowley and Slack, 2004 ). Scholars conduct literature reviews to encapsulate the research, critically assess the contributions, and clarify any alternative views in the studies ( Rowe, 2014 ).

In the context of Airbnb, there are four review articles that discuss the platform specifically ( Dann et al., 2019 ; Guttentag, 2019 ; Medina-Hernandez et al., 2020 ; Ozdemir and Turker, 2019 ). The review by Dann et al. (2019) , discusses the motives of both hosts and guests, the role of trust and reputation, Airbnb price calculations, the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry and housing market, and legal and regulatory aspects surrounding Airbnb. The review by Ozdemir and Turker (2019) discusses Airbnb from the perspectives of academics and journalists. Their article discusses legal, social, and economic issues, as well as public relations and publicity, benefits, impacts on destinations, hotel competition, the nature of the sharing economy, technology, consumer behavior, sustainability, corporate social responsibility (CSR), safety and security, growth, politics, and insurance. The intention of the review by Medina-Hernandez et al. (2020) on Airbnb is to illustrate the scarcity of research on P2P accommodation platforms other than Airbnb. Our literature review of Airbnb differs from the four previous reviews through our application of stakeholder theory to our analysis of the Airbnb phenomenon and its embedded ethical perspective. As discussed earlier, the sharing economy, including Airbnb, offers both benefits and drawbacks to its stakeholder since its been successfully reframed by regime actors as an economic opportunity ( Martin, 2016 ). Therefore, stakeholder theory, which introduces ethical issues into management decision making ( Goodpaster, 1991 ), is useful in evaluating whether ethically, Airbnb has been treating its stakeholders interests as equally important and deserving of joint “maximization.”

3. Research method