PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED J. Edgar Hoover’s 50-Year Career of Blackmail, Entrapment, and Taking Down Communist Spies

The Encyclopedia: One Book’s Quest to Hold the Sum of All Knowledge PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED

The Atomic Bomb: Arguments in Support Of The Decision

Note: This section is intended as an objective overview of the decision to use the atomic bomb for new students of the issue. For the other side of the issue, go here.

Argument #1: The Atomic Bomb Saved American Lives

The main argument in support of the decision to use the atomic bomb is that it saved American lives which would otherwise have been lost in two D-Day-style land invasions of the main islands of the Japanese homeland. The first, against the Southern island of Kyushu, had been scheduled for November 1 (Operation Torch). The second, against the main island of Honshu would take place in the spring of 1946 (Operation Coronet). The two operations combined were codenamed Operation Downfall. There is no doubt that a land invasion would have incurred extremely high casualties, for a variety of reasons. For one, Field Marshall Hisaichi Terauchi had ordered that all 100,000 Allied prisoners of war be executed if the Americans invaded. Second, it was apparent to the Japanese as much as to the Americans that there were few good landing sites, and that Japanese forces would be concentrated there. Third, there was real concern in Washington that the Japanese had made a determination to fight literally to the death. The Japanese saw suicide as an honorable alternative to surrender. The term they used was gyokusai, or, “shattering of the jewel.” It was the same rationale for their use of the so-called banzai charges employed early in the war. In his 1944 “emergency declaration,” Prime Minister Hideki Tojo had called for “100 million gyokusai,” and that the entire Japanese population be prepared to die.

For American military commanders, determining the strength of Japanese forces and anticipating the level of civilian resistance were the keys to preparing casualty projections. Numerous studies were conducted, with widely varying results. Some of the studies estimated American casualties for just the first 30 days of Operation Torch. Such a study done by General MacArthur’s staff in June estimated 23,000 US casualties.

U.S. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall thought the Americans would suffer 31,000 casualties in the first 30 days, while Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations, put them between 31,000 and 41,000. Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Chester Nimitz, whose staff conducted their own study, estimated 49,000 U.S casualties in the first 30 days, including 5,000 at sea from Kamikaze attacks.

Studies estimating total U.S. casualties were equally varied and no less grim. One by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in April 1945 resulted in an estimate of 1,200,000 casualties, with 267,000 fatalities. Admiral Leahy, Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief, estimated 268,000 casualties (35%). Former President Herbert Hoover sent a memorandum to President Truman and Secretary of War Stimson, with “conservative” estimates of 500,000 to 1,000,000 fatalities. A study done for Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s staff by William Shockley estimated the costs at 1.7 to 4 million American casualties, including 400,000-800,000 fatalities.

General Douglas MacArthur had been chosen to command US invasion forces for Operation Downfall, and his staff conducted their own study. In June their prediction was American casualties of 105,000 after 120 days of combat. Mid-July intelligence estimates placed the number of Japanese soldiers in the main islands at under 2,000,000, but that number increased sharply in the weeks that followed as more units were repatriated from Asia for the final homeland defense. By late July, MacArthur’s Chief of Intelligence, General Charles Willoughby, revised the estimate and predicted American casualties on Kyushu alone (Operation Torch) would be 500,000, or ten times what they had been on Okinawa.

All of the military planners based their casualty estimates on the ongoing conduct of the war and the evolving tactics employed by the Japanese. In the first major land combat at Guadalcanal, the Japanese had employed night-time banzai charges—direct frontal assaults against entrenched machine gun positions. This tactic had worked well against enemy forces in their Asian campaigns, but against the Marines, the Japanese lost about 2,500 troops and killed only 80 Marines.

At Tarawa in May 1943, The Japanese modified their tactics and put up a fierce resistance to the Marine amphibious landings. Once the battered Marines made it ashore, the 4,500 well-supplied and well-prepared Japanese defenders fought almost to the last man. Only 17 Japanese soldiers were alive at the end of the battle.

On Saipan in July 1944, the Japanese again put up fanatical resistance, even though a decisive U.S. Navy victory over the Japanese fleet had ended any hope of their resupply. U.S. forces had to burnthen out of holes, caves, and bunkers with flamethrowers. Japanese forces staged multiple banzai attacks. At the end of the battle the Japanese staged a final banzai that included wounded men, some of them on crutches. Marines were forced to mow them down. Meanwhile, on the north end of the island a thousand civilians threw committed suicide by jumping from the cliff to the rocks below after being promised an honorable afterlife by Emperor Hirohito, and after being threatened with death by the Japanese army. In the fall of 1944, Marines landed on the small island of Peleliu, just east of the Philippines, for what was supposed to be a four-day mission. The battle lasted two months. At Peleliu, the Japanese unveiled a new defense strategy. Colonel Kunio Nakagawa, the Japanese commander, constructed a system of heavily fortified bunkers, caves, and underground positions, and waited for the Marines to attack them, and they replaced the fruitless banzai attacks with coordinated counterattacks. Much of the island was solid volcanic rock, making the digging of foxholes with the standard-issue entrenching tool impossible. When the Marines sought cover and concealment, the terrain’s jagged, sharp edges cut up their uniforms, bodies, and equipment. The plan was to make Peleliu a bloody war of attrition, and it worked well. The fight for Umurbrogol Mountain is considered by many to be the most difficult fight that the U.S. military encountered in the entire Second World War. At Peleliu, U.S. forces suffered 50% casualties, including 1,794 killed. Japanese losses were 10,695 killed and only 202 captured. After securing the Philippines and delivering yet another shattering blow to the Japanese navy, the Americans landed next on Iwo Jima in February 1945, where the main mission was to secure three Japanese airfields. U.S. Marines again faced an enemy well entrenched in a vast network of bunkers, hidden artillery, and miles of underground tunnels. American casualties on Iwo Jima were 6,822 killed or missing and 19,217 wounded. Japanese casualties were about 18,000 killed or missing, and only 216 captured. Meanwhile, another method of Japanese resistance was emerging. With the Japanese navy neutralized, the Japanese resorted to suicide missions designed to turn piloted aircraft into guided bombs. A kamikaze air attack on ships anchored at sea on February 21 sunk an escort carrier and did severe damage to the fleet carrier Saratoga. It was a harbinger of things to come.

After Iwo Jima, only the island of Okinawa stood between U.S. forces and Japan. Once secured, Okinawa would be used as a staging area for Operation Torch. Situated less than 400 miles from Kyushu, the island had been Japanese territory since 1868, and it was home to several hundred thousand Japanese civilians. The Battle of Okinawa was fought from April 1 – June 22, 1945. Five U.S. Army divisions, three Marine divisions, and dozens of Navy vessels participated in the 82-day battle. The Japanese stepped up their use of kamikaze attacks, this time sending them at U.S. ships in waves. Seven major kamikaze attacks took place involving 1,500 planes. They took a devastating toll—both physically and psychologically. The U.S. Navy’s dead, at 4,907, exceeded its wounded, primarily because of the kamikaze.

On land, U.S. forces again faced heavily fortified and well-constructed defenses. The Japanese extracted heavy American casualties at one line of defense, and then as the Americans began to gain the upper hand, fell back to another series of fortifications. Japanese defenders and civilians fought to the death (even women with spears) or committed suicide rather than be captured. The civilians had been told the Americans would go on a rampage of killing and raping. About 95,000 Japanese soldiers were killed, and possibly as many as 150,000 civilians died, or 25% of the civilian population. And the fierce resistance took a heavy toll on the Americans; 12,513 were killed on Okinawa, and another 38,916 were wounded.

The increased level of Japanese resistance on Okinawa was of particular significance to military planners, especially the resistance of civilians. This was a concern for the American troops as well. In the Ken Burns documentary The War (2007), a veteran Marine pilot of the Okinawa campaign relates his thoughts at the time about invading the home islands:

By then, our sense of the strangeness of the Japanese opposition had become stronger. And I could imagine every farmer with his pitchfork coming at my guts; every pretty girl with a hand grenade strapped to her bottom, or something; that everyone would be an enemy.

Although the estimates of American casualties in Operation Downfall vary widely, no one doubts that they would have been significant. A sobering indicator of the government’s expectations is that 500,000 Purple Heart medals (awarded for combat-related wounds) were manufactured in preparation for Operation Downfall.

Argument #1.1: The Atomic Bomb Saved Japanese Lives

A concurrent, though ironic argument supporting the use of the Atomic bomb is that because of the expected Japanese resistance to an invasion of the home island, its use actually saved Japanese lives. Military planners included Japanese casualties in their estimates. The study done for Secretary of War Stimson predicted five to ten million Japanese fatalities. There is support for the bomb even among some Japanese. In 1983, at the annual observance of Hiroshima’s destruction, an aging Japanese professor recalled that at war’s end, due to the extreme food rationing, he had weighed less than 90 pounds and could scarcely climb a flight of stairs. “I couldn’t have survived another month,” he said. “If the military had its way, we would have fought until all 80 million Japanese were dead. Only the atomic bomb saved me. Not me alone, but many Japanese, ironically speaking, were saved by the atomic bomb.”

Argument #1.2: It Was Necessary to Shorten the War

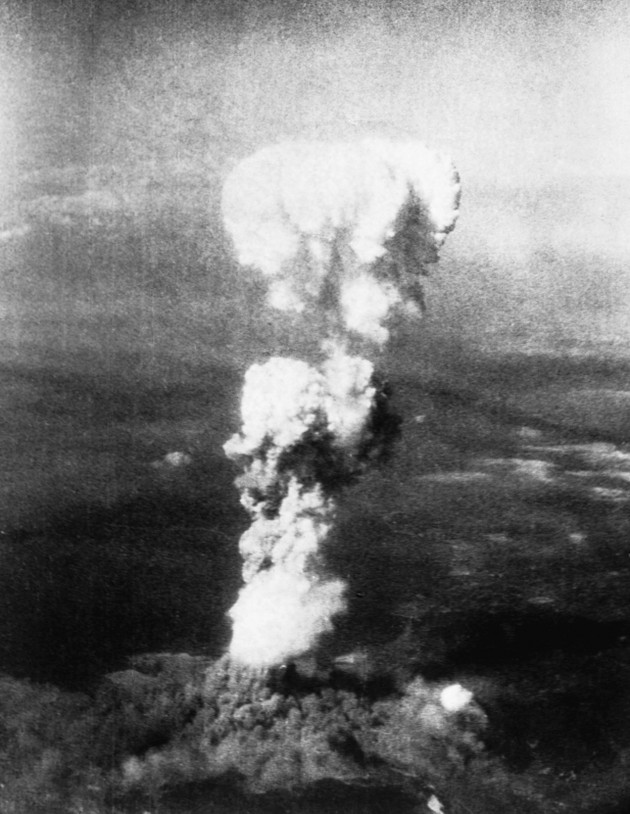

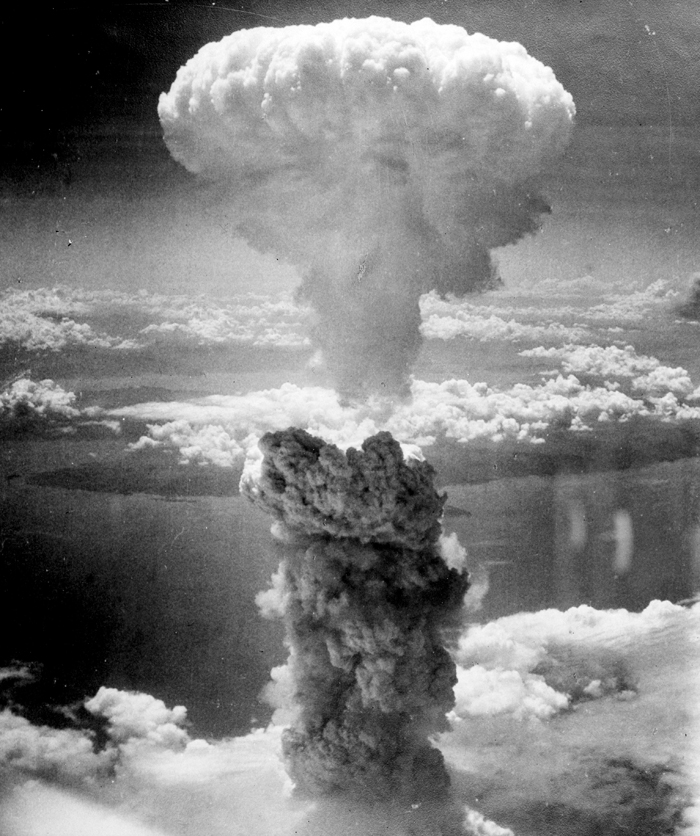

Another concurrent argument supporting the use of the Atomic bomb is that it achieved its primary objective of shortening the war. The bombs were dropped on August 6 and 9. The next day, the Japanese requested a halting of the war. On August 14 Emperor Hirohito announced to the Japanese people that they would surrender, and the United States celebrated V-J Day (Victory over Japan). Military planners had wanted the Pacific war finished no later than a year after the fall of Nazi Germany. The rationale was the belief that in a democracy, there is only so much that can reasonably be asked of its citizen soldiers (and of the voting public).

As Army Chief of Staff George Marshall later put it, “a democracy cannot fight a Seven Years’ war.” By the summer of 1945 the American military was exhausted, and the sheer number of troops needed for Operation Downfall meant that not only would the troops in the Pacific have to make one more landing, but even many of those troops whose valor and sacrifice had brought an end to the Nazi Third Reich were to be sent Pacific. In his 2006 memoir, former 101st Airborne battalion commander Richard Winters reflected on the state of his men as they played baseball in the summer of 1945 in occupied Austria (Winters became something of a celebrity after his portrayal in the extremely popular 2001 HBO series Band of Brothers):

During the baseball games when the men were stripped to their waists, or wearing only shorts, the sight of all those battle scars made me conscious of the fact that other than a handful of men in the battalion who had survived all four campaigns, only a few were lucky enough to be without at least one scar. Some men had two, three, even four scars on their chests, backs, arms, or legs. Keep in mind that…I was looking only at the men who were not seriously wounded.

Supporters of the bomb wonder if it was reasonable to ask even more sacrifice of these men. Since these veterans are the men whose lives (or wholeness) were, by this argument, saved by the bomb, it is relevant to survey their thoughts on the matter, as written in various war memoirs going back to the 1950s. The record is mixed. For example, despite Winters’ observation above, he seemed to have reservations about the bomb: “Three days later, on August 14, Japan surrendered. Apparently the atomic bomb carried as much punch as a regiment of paratroopers. It seemed inhumane for our national leaders to employ either weapon on the human race.”

His opinion is not shared by other members of Easy Company, some of whom published their own memoirs after the interest generated by Band of Brothers. William “Wild Bill” Guarnere expressed a very blunt opinion about the bomb in 2007:

We were on garrison duty in France for about a month, and in August, we got great news: we weren’t going to the Pacific. The U.S. dropped a bomb on Hiroshima, the Japanese surrendered, and the war was over. We were so relieved. It was the greatest thing that could have happened. Somebody once said to me that the bomb was the worst thing that ever happened, that the U.S. could have found other ways. I said, “Yeah, like what? Me and all my buddies jumping in Tokyo, and the Allied forces going in, and all of us getting killed? Millions more Allied soldiers getting killed?” When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor were they concerned about how many lives they took? We should have dropped eighteen bombs as far as I’m concerned. The Japanese should have stayed out of it if they didn’t want bombs dropped. The end of the war was good news to us. We knew we were going home soon.

Those soldiers with extensive combat experience in the Pacific theater and with first-hand knowledge of Japanese resistance also express conflicting thoughts about the bomb. All of them write of the relief and joy they felt upon first hearing the news. William Manchester, in Goodbye, Darkness: a Memoir of the Pacific War, wrote, “You think of the lives which would have been lost in an invasion of Japan’s home islands—a staggering number of American lives but millions more of Japanese—and you thank God for the atomic bomb.”

But in preparation for writing his 1980 memoir, when Manchester visited Tinian, the small Pacific island from which the Hiroshima mission was launched, he reflected on the “global angst” that Tinian represents. He writes that while the battle to take Tinian itself was relatively easy, “the aftermath was ominous.” It was also from Tinian that napalm was dropped on Japanese cities, which Manchester describes as “one of thecruelest instruments of war.” Manchester continues:

This is where the nuclear shadow first appeared. I feel forlorn, alienated, wholly without empathy for the men who did what they did. This was not my war…Standing there, notebook in hand; you are shrouded in absolute, inexpressible loneliness.

Two other Pacific memoirs, both published decades ago, resurged in popularity in 2010, owing to their authors’ portrayal in another HBO mini-series, The Pacific (2010). Eugene Sledge published his combat memoir in 1981. He describes the moment when they first heard about the atom bomb, having just survived the Okinawa campaign:

We received the news with quiet disbelief coupled with an indescribable sense of relief. We thought the Japanese would never surrender. Many refused to believe it. Sitting around in stunned silence, we remembered our dead. So many dead. So many maimed. So many bright futures consigned to the ashes of the past. So many dreams lost in the madness that had engulfed us. Except for a few widely scattered shouts of joy, the survivors sat hollow-eyed and silent, trying to comprehend a world without war.

Robert Leckie, like Manchester, seems to have had conflicting feelings about the bomb in his 1957 memoir Helmet for my Pillow. When the bomb was dropped, Leckie was recovering from wounds suffered on Peleliu:

Suddenly, secretly, covertly–I rejoiced. For as I lay there in that hospital, I had faced the bleak prospect of returning to the Pacific and the war and the law of averages. But now, I knew the Japanese would have to lay down their arms. The war was over. I had survived. Like a man wielding a submachine gun to defend himself against an unarmed boy, I had survived. So I rejoiced.

But just a paragraph later, Leckie reflects writes:

The suffering of those who lived, the immolation [death by burning] of those who died–that must now be placed in the scales of God’s justice that began to tip so awkwardly against us when the mushroom rose over the world…Dear Father, forgive us for that awful cloud.

Argument #1.3: Only the Bomb Convinced the Emperor to Intervene

A third concurrent argument defending the bomb is the observation that even after the first two bombs were dropped, and the Russians had declared war, the Japanese still almost did not surrender. The Japanese cabinet convened in emergency session on August 7. Military authorities refused to concede that the Hiroshima bomb was atomic in nature and refused to consider surrender. The following day, Emperor Hirohito privately expressed to Prime Minister Togo his determination that the war should end and the cabinet was convened again on August 9. At this point Prime Minister Suzuki was in agreement, but a unanimous decision was required and three of the military chiefs still refused to admit defeat.

Some in the leadership argued that there was no way the Americans could have refined enough fissionable material to produce more than one bomb. But then the bombing of Nagasaki had demonstrated otherwise, and a lie told by a downed American pilot convinced War Minister Korechika Anami that the Americans had as many as a hundred bombs. (The official scientific report confirming the bomb was atomic arrived at Imperial Headquarters on the 10th). Even so, hours of meetings and debates lasting well into the early morning hours of the 10th still resulted in a 3-3 deadlock. Prime Minister Suzuki then took the unprecedented step of asking Emperor Hirohito, who never spoke at cabinet meetings, to break the deadlock. Hirohito responded:

I have given serious thought to the situation prevailing at home and abroad and have concluded that continuing the war can only mean destruction for the nation and prolongation of bloodshed and cruelty in the world. I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer.

In his 1947 article published in Harper’s, former Secretary of War Stimson expressed his opinion that only the atomic bomb convinced the emperor to step in: “All the evidence I have seen indicates that the controlling factor in the final Japanese decision to accept our terms of surrender was the atomic bomb.”

Emperor Hirohito agreed that Japan should accept the Potsdam Declaration (the terms of surrender proposed by the Americans, discussed below), and then recorded a message on phonograph to the Japanese people.

Japanese hard-liners attempted to suppress this recording, and late on the evening of the 14th, attempted a coup against the Emperor, presumably to save him from himself. The coup failed, but the fanaticism required to make such an attempt is further evidence to bomb supporters that, without the bomb, Japan would never have surrendered. In the end, the military leaders accepted surrender partly because of the Emperor’s intervention, and partly because the atomic bomb helped them “save face” by rationalizing that they had not been defeated by because of a lack of spiritual power or strategic decisions, but by science. In other words, the Japanese military hadn’t lost the war, Japanese science did.

Atomic Bomb Argument 2: The Decision was made by a Committee of Shared Responsibility

Supporters of President Truman’s decision to use atomic weapons point out that the President did not act unilaterally, but rather was supported by a committee of shared responsibility. The Interim Committee, created in May 1945, was primarily tasked with providing advice to the President on all matters pertaining to nuclear energy. Most of its work focused on the role of the bomb after the war. But the committee did consider the question of its use against Japan.

Secretary of War Henry Stimson chaired the committee. Truman’s personal representative was James F. Byrnes, former U.S. Senator and Truman’s pick to be Secretary of State. The committee sought the advice of four physicists from the Manhattan Project, including Enrico Fermi and J. Robert Oppenheimer. The scientific panel wrote, “We see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.” The final recommendation to the President was arrived at on June 1 and is described in the committee meeting log:

Mr. Byrnes recommended, and the Committee agreed, that the Secretary of War should be advised that, while recognizing that the final selection of the target was essentially a military decision, the present view of the Committee was that the bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible; that it be used on a war plant surrounded by workers’ homes; and that it be used without prior warning.

On June 21, the committee reaffirmed its recommendation with the following wording:

…that the weapon be used against Japan at the earliest opportunity, that it be used without warning, and that it be used on a dual target, namely, a military installation or war plant surrounded by or adjacent to homes or other buildings most susceptible to damage.

Supporters of Truman’s decision thus argue that the President, in dropping the bomb, was simply following the recommendation of the most experienced military, political, and scientific minds in the nation, and to do otherwise would have been grossly negligent.

Atomic Bomb Argument #3: The Japanese Were Given Fair Warning (Potsdam Declaration & Leaflets)

Supporters of Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb point out that Japan had been given ample opportunity to surrender. On July 26, with the knowledge that the Los Alamos test had been successful, President Truman and the Allies issued a final ultimatum to Japan, known as the Potsdam Declaration (Truman was in Potsdam, Germany at the time). Although it had been decided by Prime Minster Churchill and President Roosevelt back at the Casablanca Conference that the Allies would accept only unconditional surrender from the Axis, the Potsdam Declaration does lay out some terms of surrender. The government responsible for the war would be dismantled, there would be a military occupation of Japan, and the nation would be reduced in size to pre-war borders. The military, after being disarmed, would be permitted to return home to lead peaceful lives. Assurance was given that the allies had no desire to enslave or destroy the Japanese people, but there would be war crimes trials. Peaceful industries would be allowed to produce goods, and basic freedoms of speech, religion, and thought would be introduced. The document concluded with an ultimatum: “We call upon the Government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all the Japanese armed forces…the alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.” To bomb supporters, the Potsdam Declaration was m5ore than fair in its surrender terms and in its warning of what would happen should those terms be rejected. The Japanese did not respond to the declaration. Additionally, bomb supporters argue that Japanese civilians were warned in advance through millions of leaflets dropped on Japanese cities by U.S. warplanes. In the months preceding the atomic bombings, some 63 million leaflets were dropped on 35 cities target for destruction by U.S. air forces. The Japanese people generally regarded the information on these leaflets as truthful, but anyone caught in possession of one was subject to arrest by the government. Some of the leaflets mentioned the terms of surrender offered in the Potsdam Declaration and urged the civilians to convince Japanese government to accept them—an unrealistic expectation to say the least.

Generally, the leaflets warned that the city was considered a target and urged the civilian populations to evacuate. However, no leaflets specifically warning about a new destructive weapon were dropped until after Hiroshima, and it’s also not clear where U.S. officials thought the entire urban population of 35 Japanese cities could viably relocate to even if they did read and heed the warnings.

Argument 4: The atom bomb was in retaliation for Japanese barbarism

Although it is perhaps not the most civilized of arguments, Americans with an “eye for an eye” philosophy of justice argue that the atomic bomb was payback for the undeniably brutal, barbaric, criminal conduct of the Japanese Army. Pumped up with their own version of master race theories, the Japanese military committed atrocities throughout Asia and the Pacific. They raped women, forced others to become sexual slaves, murdered civilians, and tortured and executed prisoners. Most famously, in a six-week period following the Japanese capture of the Chinese city of Nanjing, Japanese soldiers (and some civilians) went on a rampage. They murdered several hundred thousand unarmed civilians, and raped between 20,000-80,000 men, women and children.

With regards to Japanese conduct specific to Americans, there is the obvious “back-stabbing” aspect of the “surprise” attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. That the Japanese government was still engaged in good faith diplomatic negotiations with the State Department at the very moment the attack was underway is a singular instance of barbaric behavior that bomb supporters point to as just cause for using the atom bomb. President Truman said as much when he made his August 6 radio broadcast to the nation about Hiroshima: “The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold.”

The infamous “Bataan Death March” provides further rationale for supporters of this argument. Despite having a presence in the Philippines since 1898 and a long-standingstrategic plan for a theoretical war with Japan, the Americans were caught unprepared for the Japanese invasion of the main island of Luzon. After retreating to the rugged Bataan peninsula and holding out for months, it became evident that America had no recourse but to abandon them to their fate. After General MacArthur removed his command to Australia under the cover of darkness, 78,000 American and Filipino troops surrendered to the Japanese, the largest surrender in American history.

Despite promises from Japanese commanders, the American prisoners were treated inhumanely. They were force-marched back up the peninsula toward trains and a POW camp beyond. Along the way they were beaten, deprived of food & water, tortured, buried alive, and executed. The episode became known at The Bataan Death March. Thousands perished along the way. And when the survivors reached their destination, Camp O’Donnell, many thousands more died from disease, starvation, and forced labor. Perhaps fueled by humiliation and a sense of helplessness, few events of WWII aroused such fury in Americans as did the Bataan Death March. To what extent it may have been a factor in President Truman’s decision is unknown, but it is frequently cited, along with Pearl Harbor, as justification for the payback given out at Hiroshima and Nagasaki to those who started the war. The remaining two arguments in support of the bomb are based on consideration of the unfortunate predicament facing President Truman as the man who inherited both the White House and years of war policy from the late President Roosevelt.

Argument 5: The Manhattan Project Expense Required Use of the Bomb

The Manhattan Project had been initiated by Roosevelt back in 1939, five years before Truman was asked to be on the Democratic ticket. By the time Roosevelt died in April 1945, almost 2 billion dollars of taxpayer money had been spent on the project. The Manhattan Project was the most expensive government project in history at that time. The President’s Chief of Staff, Admiral Leahy, said, “I know FDR would have used it in a minute to prove that he had not wasted $2 billion.” Bomb supporters argue that the pressure to honor the legacy of FDR, who had been in office for so long that many Americans could hardly remember anyone else ever being president, was surely enormous. The political consequences of such a waste of expenditures, once the public found out, would have been disastrous for the Democrats for decades to come. (The counter-argument, of course, is that fear of losing an election is no justification for using such a weapon).

Argument 6: Truman Inherited the War Policy of Bombing Cities

Likewise, the decision to intentionally target civilians, however morally questionable and distasteful, had begun under President Roosevelt, and it was not something that President Truman could realistically be expected to roll back. Precedents for bombing civilians began as early as 1932, when Japanese planes bombed Chapei, the Chinese sector of Shanghai. Italian forces bombed civilians as part of their conquest of Ethiopia in 1935-1936. Germany had first bombed civilians as part of an incursion into the Spanish Civil War. At the outbreak of WWII in September 1939, President Roosevelt was troubled by the prospect of what seemed likely to be Axis strategy, and on the day of the German invasion of Poland, he wrote to the governments of France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Great Britain. Roosevelt said that these precedents for attacking civilians from the air, “has sickened the hearts of every civilized man and woman, and has profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity.” He went on to describe such actions as “inhuman barbarism,” and appealed to the war-makers not to target civilian populations. But Germany bombed cities in Poland in 1939, destroyed the Dutch city of Rotterdam in 1940, and infamously “blitzed” London, Coventry, and other British cities in the summer and fall of the 1940. The British retaliated by bombing German cities. Allied war leaders rationalized that to win the war, it was necessary to cripple the enemy’s capacity to make war. Since cities contained factories that produced war materials, and since civilians worked in factories, the population of cities (including the “workers’ dwellings” surrounding those factories) were legitimate military targets.

Despite Roosevelt’s “appeal” in 1939, he and the nation had long crossed that moral line by war’s end. This fact perhaps reveals the psychological effects of killing on all of the war’s participants, and says something about the moral atmosphere in which President Truman found himself upon the President’s death. On February 13, 1945, 1,300 U.S. and British heavy bombers firebombed the German city of Dresden, the center of German art and culture, creating a firestorm that destroyed 15 square miles and killed 25,000 civilians. Meanwhile, still five weeks before Truman took office; American bombers dropped 2,000 tons of napalm on Tokyo, creating a firestorm with hurricane-force winds. Flight crews flying high over the 16 square miles of devastation reported smelling burning fleshbelow. Approximately 125,000 Japanese civilians died in that raid. By the time the atomic bomb was ready, similar attacks had been launched on the Japanese cities of Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. Quickly running out of targets, the B-29 bombers went back over Tokyo and killed another 80,000 civilians. Atomic Bomb supporters argue that, although this destruction is distasteful by post-war sensibilities, it had become the norm long before President Truman took office, and the atomic bomb was just one more weapon in the arsenal to be employed under this policy. To expect the new president, who had to make decisions under enormous pressure, to roll back this policy—to roll back the social norm—was simply not realistic.

Sources Used and Recommended

This article is part of our larger educational resource on World War Two. For a comprehensive list of World War 2 facts, including the primary actors in the war, causes, a comprehensive timeline, and bibliography, click here.

Cite This Article

- How Much Can One Individual Alter History? More and Less...

- Why Did Hitler Hate Jews? We Have Some Answers

- Reasons Against Dropping the Atomic Bomb

- Is Russia Communist Today? Find Out Here!

- Phonetic Alphabet: How Soldiers Communicated

- How Many Americans Died in WW2? Here Is A Breakdown

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II

A Collection of Primary Sources

Updated National Security Archive Posting Marks 75th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombings of Japan and the End of World War II

Extensive Compilation of Primary Source Documents Explores Manhattan Project, Eisenhower’s Early Misgivings about First Nuclear Use, Curtis LeMay and the Firebombing of Tokyo, Debates over Japanese Surrender Terms, Atomic Targeting Decisions, and Lagging Awareness of Radiation Effects

Washington, D.C., August 4, 2020 – To mark the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the National Security Archive is updating and reposting one of its most popular e-books of the past 25 years.

While U.S. leaders hailed the bombings at the time and for many years afterwards for bringing the Pacific war to an end and saving untold thousands of American lives, that interpretation has since been seriously challenged. Moreover, ethical questions have shrouded the bombings which caused terrible human losses and in succeeding decades fed a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union and now Russia and others.

Three-quarters of a century on, Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain emblematic of the dangers and human costs of warfare, specifically the use of nuclear weapons. Since these issues will be subjects of hot debate for many more years, the Archive has once again refreshed its compilation of declassified U.S. government documents and translated Japanese records that first appeared on these pages in 2005.

* * * * *

Introduction

By William Burr

The 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 is an occasion for sober reflection. In Japan and elsewhere around the world, each anniversary is observed with great solemnity. The bombings were the first time that nuclear weapons had been detonated in combat operations. They caused terrible human losses and destruction at the time and more deaths and sickness in the years ahead from the radiation effects. And the U.S. bombings hastened the Soviet Union’s atomic bomb project and have fed a big-power nuclear arms race to this day. Thankfully, nuclear weapons have not been exploded in war since 1945, perhaps owing to the taboo against their use shaped by the dropping of the bombs on Japan.

Along with the ethical issues involved in the use of atomic and other mass casualty weapons, why the bombs were dropped in the first place has been the subject of sometimes heated debate. As with all events in human history, interpretations vary and readings of primary sources can lead to different conclusions. Thus, the extent to which the bombings contributed to the end of World War II or the beginning of the Cold War remain live issues. A significant contested question is whether, under the weight of a U.S. blockade and massive conventional bombing, the Japanese were ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped. Also still debated is the impact of the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria, compared to the atomic bombings, on the Japanese decision to surrender. Counterfactual issues are also disputed, for example whether there were alternatives to the atomic bombings, or would the Japanese have surrendered had a demonstration of the bomb been used to produced shock and awe. Moreover, the role of an invasion of Japan in U.S. planning remains a matter of debate, with some arguing that the bombings spared many thousands of American lives that otherwise would have been lost in an invasion.

Those and other questions will be subjects of discussion well into the indefinite future. Interested readers will continue to absorb the fascinating historical literature on the subject. Some will want to read declassified primary sources so they can further develop their own thinking about the issues. Toward that end, in 2005, at the time of the 60th anniversary of the bombings, staff at the National Security Archive compiled and scanned a significant number of declassified U.S. government documents to make them more widely available. The documents cover multiple aspects of the bombings and their context. Also included, to give a wider perspective, were translations of Japanese documents not widely available before. Since 2005, the collection has been updated. This latest iteration of the collection includes corrections, a few minor revisions, and updated footnotes to take into account recently published secondary literature.

2015 Update

August 4, 2015 – A few months after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, General Dwight D. Eisenhower commented during a social occasion “how he had hoped that the war might have ended without our having to use the atomic bomb.” This virtually unknown evidence from the diary of Robert P. Meiklejohn, an assistant to Ambassador W. Averell Harriman, published for the first time today by the National Security Archive, confirms that the future President Eisenhower had early misgivings about the first use of atomic weapons by the United States. General George C. Marshall is the only high-level official whose contemporaneous (pre-Hiroshima) doubts about using the weapons against cities are on record.

On the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the National Security Archive updates its 2005 publication of the most comprehensive on-line collection of declassified U.S. government documents on the first use of the atomic bomb and the end of the war in the Pacific. This update presents previously unpublished material and translations of difficult-to-find records. Included are documents on the early stages of the U.S. atomic bomb project, Army Air Force General Curtis LeMay’s report on the firebombing of Tokyo (March 1945), Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s requests for modification of unconditional surrender terms, Soviet documents relating to the events, excerpts from the Robert P. Meiklejohn diaries mentioned above, and selections from the diaries of Walter J. Brown, special assistant to Secretary of State James Byrnes.

The original 2005 posting included a wide range of material, including formerly top secret "Magic" summaries of intercepted Japanese communications and the first-ever full translations from the Japanese of accounts of high level meetings and discussions in Tokyo leading to the Emperor’s decision to surrender. Also documented are U.S. decisions to target Japanese cities, pre-Hiroshima petitions by scientists questioning the military use of the A-bomb, proposals for demonstrating the effects of the bomb, debates over whether to modify unconditional surrender terms, reports from the bombing missions of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and belated top-level awareness of the radiation effects of atomic weapons.

The documents can help readers to make up their own minds about long-standing controversies such as whether the first use of atomic weapons was justified, whether President Harry S. Truman had alternatives to atomic attacks for ending the war, and what the impact of the Soviet declaration of war on Japan was. Since the 1960s, when the declassification of important sources began, historians have engaged in vigorous debate over the bomb and the end of World War II. Drawing on sources at the National Archives and the Library of Congress as well as Japanese materials, this electronic briefing book includes key documents that historians of the events have relied upon to present their findings and advance their interpretations.

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II: A Collection of Primary Sources

Seventy years ago this month, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and the Japanese government surrendered to the United States and its allies. The nuclear age had truly begun with the first military use of atomic weapons. With the material that follows, the National Security Archive publishes the most comprehensive on-line collection to date of declassified U.S. government documents on the atomic bomb and the end of the war in the Pacific. Besides material from the files of the Manhattan Project, this collection includes formerly “Top Secret Ultra” summaries and translations of Japanese diplomatic cable traffic intercepted under the “Magic” program. Moreover, the collection includes for the first time translations from Japanese sources of high level meetings and discussions in Tokyo, including the conferences when Emperor Hirohito authorized the final decision to surrender. [1]

Ever since the atomic bombs were exploded over Japanese cities, historians, social scientists, journalists, World War II veterans, and ordinary citizens have engaged in intense controversy about the events of August 1945. John Hersey’s Hiroshima , first published in the New Yorker in 1946 encouraged unsettled readers to question the bombings while church groups and some commentators, most prominently Norman Cousins, explicitly criticized them. Former Secretary of War Henry Stimson found the criticisms troubling and published an influential justification for the attacks in Harper’s . [2] During the 1960s the availability of primary sources made historical research and writing possible and the debate became more vigorous. Historians Herbert Feis and Gar Alperovitz raised searching questions about the first use of nuclear weapons and their broader political and diplomatic implications. The controversy, especially the arguments made by Alperovitz and others about “atomic diplomacy” quickly became caught up in heated debates over Cold War “revisionism.” The controversy simmered over the years with major contributions by Martin Sherwin and Barton J. Bernstein but it became explosive during the mid-1990s when curators at the National Air and Space Museum met the wrath of the Air Force Association over a proposed historical exhibit on the Enola Gay. [3] The NASM exhibit was drastically scaled-down but historians and journalist continued to engage in the debate. Alperovitz, Bernstein, and Sherwin made new contributions as did other historians, social scientists, and journalists including Richard B. Frank, Herbert Bix, Sadao Asada, Kai Bird, Robert James Maddox, Sean Malloy, Robert P. Newman, Robert S. Norris, Tsuyoshi Hagesawa, and J. Samuel Walker. [4]

The continued controversy has revolved around the following, among other, questions:

- were the atomic strikes necessary primarily to avert an invasion of Japan in November 1945?

- Did Truman authorize the use of atomic bombs for diplomatic-political reasons-- to intimidate the Soviets--or was his major goal to force Japan to surrender and bring the war to an early end?

- If ending the war quickly was the most important motivation of Truman and his advisers to what extent did they see an “atomic diplomacy” capability as a “bonus”?

- To what extent did subsequent justification for the atomic bomb exaggerate or misuse wartime estimates for U.S. casualties stemming from an invasion of Japan?

- Were there alternatives to the use of the weapons? If there were, what were they and how plausible are they in retrospect? Why were alternatives not pursued?

- How did the U.S. government plan to use the bombs? What concepts did war planners use to select targets? To what extent were senior officials interested in looking at alternatives to urban targets? How familiar was President Truman with the concepts that led target planners chose major cities as targets?

- What did senior officials know about the effects of atomic bombs before they were first used. How much did top officials know about the radiation effects of the weapons?

- Did President Truman make a decision, in a robust sense, to use the bomb or did he inherit a decision that had already been made?

- Were the Japanese ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped? To what extent had Emperor Hirohito prolonged the war unnecessarily by not seizing opportunities for surrender?

- If the United States had been more flexible about the demand for “unconditional surrender” by explicitly or implicitly guaranteeing a constitutional monarchy would Japan have surrendered earlier than it did?

- How decisive was the atomic bombings to the Japanese decision to surrender?

- Was the bombing of Nagasaki unnecessary? To the extent that the atomic bombing was critically important to the Japanese decision to surrender would it have been enough to destroy one city?

- Would the Soviet declaration of war have been enough to compel Tokyo to admit defeat?

- Was the dropping of the atomic bombs morally justifiable?

This compilation will not attempt to answer these questions or use primary sources to stake out positions on any of them. Nor is it an attempt to substitute for the extraordinary rich literature on the atomic bombings and the end of World War II. Nor does it include any of the interviews, documents prepared after the events, and post-World War II correspondence, etc. that participants in the debate have brought to bear in framing their arguments. Originally this collection did not include documents on the origins and development of the Manhattan Project, although this updated posting includes some significant records for context. By providing access to a broad range of U.S. and Japanese documents, mainly from the spring and summer of 1945, interested readers can see for themselves the crucial source material that scholars have used to shape narrative accounts of the historical developments and to frame their arguments about the questions that have provoked controversy over the years. To help readers who are less familiar with the debates, commentary on some of the documents will point out, although far from comprehensively, some of the ways in which they have been interpreted. With direct access to the documents, readers may develop their own answers to the questions raised above. The documents may even provoke new questions.

Contributors to the historical controversy have deployed the documents selected here to support their arguments about the first use of nuclear weapons and the end of World War II. The editor has closely reviewed the footnotes and endnotes in a variety of articles and books and selected documents cited by participants on the various sides of the controversy. [5] While the editor has a point of view on the issues, to the greatest extent possible he has tried to not let that influence document selection, e.g., by selectively withholding or including documents that may buttress one point of view or the other. The task of compilation involved consultation of primary sources at the National Archives, mainly in Manhattan Project files held in the records of the Army Corps of Engineers, Record Group 77, but also in the archival records of the National Security Agency. Private collections were also important, such as the Henry L. Stimson Papers held at Yale University (although available on microfilm, for example, at the Library of Congress) and the papers of W. Averell Harriman at the Library of Congress. To a great extent the documents selected for this compilation have been declassified for years, even decades; the most recent declassifications were in the 1990s.

The U.S. documents cited here will be familiar to many knowledgeable readers on the Hiroshima-Nagasaki controversy and the history of the Manhattan Project. To provide a fuller picture of the transition from U.S.-Japanese antagonism to reconciliation, the editor has done what could be done within time and resource constraints to present information on the activities and points of view of Japanese policymakers and diplomats. This includes a number of formerly top secret summaries of intercepted Japanese diplomatic communications, which enable interested readers to form their own judgments about the direction of Japanese diplomacy in the weeks before the atomic bombings. Moreover, to shed light on the considerations that induced Japan’s surrender, this briefing book includes new translations of Japanese primary sources on crucial events, including accounts of the conferences on August 9 and 14, where Emperor Hirohito made decisions to accept Allied terms of surrender.

[ Editor’s Note: Originally prepared in July 2005 this posting has been updated, with new documents, changes in organization, and other editorial changes. As noted, some documents relating to the origins of the Manhattan Project have been included in addition to entries from the Robert P. Meiklejohn diaries and translations of a few Soviet documents, among other items. Moreover, recent significant contributions to the scholarly literature have been taken into account.]

I. Background on the U.S. Atomic Project

Documents 1A-C: Report of the Uranium Committee

1A . Arthur H. Compton, National Academy of Sciences Committee on Atomic Fission, to Frank Jewett, President, National Academy of Sciences, 17 May 1941, Secret

1B . Report to the President of the National Academy of Sciences by the Academy Committee on Uranium, 6 November 1941, Secret

1C . Vannevar Bush, Director, Office of Scientific Research and Development, to President Roosevelt, 27 November 1941, Secret

Source: National Archives, Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Record Group 227 (hereinafter RG 227), Bush-Conant papers microfilm collection, Roll 1, Target 2, Folder 1, "S-1 Historical File, Section A (1940-1941)."

This set of documents concerns the work of the Uranium Committee of the National Academy of Sciences, an exploratory project that was the lead-up to the actual production effort undertaken by the Manhattan Project. The initial report, May 1941, showed how leading American scientists grappled with the potential of nuclear energy for military purposes. At the outset, three possibilities were envisioned: radiological warfare, a power source for submarines and ships, and explosives. To produce material for any of those purposes required a capability to separate uranium isotopes in order to produce fissionable U-235. Also necessary for those capabilities was the production of a nuclear chain reaction. At the time of the first report, various methods for producing a chain reaction were envisioned and money was being budgeted to try them out.

Later that year, the Uranium Committee completed its report and OSRD Chairman Vannevar Bush reported the findings to President Roosevelt: As Bush emphasized, the U.S. findings were more conservative than those in the British MAUD report: the bomb would be somewhat “less effective,” would take longer to produce, and at a higher cost. One of the report’s key findings was that a fission bomb of superlatively destructive power will result from bringing quickly together a sufficient mass of element U235.” That was a certainty, “as sure as any untried prediction based upon theory and experiment can be.” The critically important task was to develop ways and means to separate highly enriched uranium from uranium-238. To get production going, Bush wanted to establish a “carefully chosen engineering group to study plans for possible production.” This was the basis of the Top Policy Group, or the S-1 Committee, which Bush and James B. Conant quickly established. [6]

In its discussion of the effects of an atomic weapon, the committee considered both blast and radiological damage. With respect to the latter, “It is possible that the destructive effects on life caused by the intense radioactivity of the products of the explosion may be as important as those of the explosion itself.” This insight was overlooked when top officials of the Manhattan Project considered the targeting of Japan during 1945. [7]

Documents 2A-B: Going Ahead with the Bomb

2A : Vannevar Bush to President Roosevelt, 9 March 1942, with memo from Roosevelt attached, 11 March 1942, Secret

2B : Vannevar Bush to President Roosevelt, 16 December 1942, Secret (report not attached)

Sources: 2A: RG 227, Bush-Conant papers microfilm collection, Roll 1, Target 2, Folder 1, "S-1 Historical File, Section II (1941-1942): 2B: Bush-Conant papers, S-1 Historical File, Reports to and Conferences with the President (1942-1944)

The Manhattan Project never had an official charter establishing it and defining its mission, but these two documents are the functional equivalent of a charter, in terms of presidential approvals for the mission, not to mention for a huge budget. In a progress report, Bush told President Roosevelt that the bomb project was on a pilot plant basis, but not yet at the production stage. By the summer, once “production plants” would be at work, he proposed that the War Department take over the project. In reply, Roosevelt wrote a short memo endorsing Bush’s ideas as long as absolute secrecy could be maintained. According to Robert S. Norris, this was “the fateful decision” to turn over the atomic project to military control. [8]

Some months later, with the Manhattan Project already underway and under the direction of General Leslie Grove, Bush outlined to Roosevelt the effort necessary to produce six fission bombs. With the goal of having enough fissile material by the first half of 1945 to produce the bombs, Bush was worried that the Germans might get there first. Thus, he wanted Roosevelt’s instructions as to whether the project should be “vigorously pushed throughout.” Unlike the pilot plant proposal described above, Bush described a real production order for the bomb, at an estimated cost of a “serious figure”: $400 million, which was an optimistic projection given the eventual cost of $1.9 billion. To keep the secret, Bush wanted to avoid a “ruinous” appropriations request to Congress and asked Roosevelt to ask Congress for the necessary discretionary funds. Initialed by President Roosevelt (“VB OK FDR”), this may have been the closest that he came to a formal approval of the Manhattan Project.

Document 3 : Memorandum by Leslie R. Grove, “Policy Meeting, 5/5/43,” Top Secret

Source: National Archives, Record Group 77, Records of the Army Corps of Engineers (hereinafter RG 77), Manhattan Engineering District (MED), Minutes of the Military Policy Meeting (5 May 1943), Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 3, Target 6, Folder 23, “Military Policy Committee, Minutes of Meetings”

Before the Manhattan Project had produced any weapons, senior U.S. government officials had Japanese targets in mind. Besides discussing programmatic matters (e.g., status of gaseous diffusion plants, heavy water production for reactors, and staffing at Las Alamos), the participants agreed that the first use could be Japanese naval forces concentrated at Truk Harbor, an atoll in the Caroline Islands. If there was a misfire the weapon would be difficult for the Japanese to recover, which would not be the case if Tokyo was targeted. Targeting Germany was rejected because the Germans were considered more likely to “secure knowledge” from a defective weapon than the Japanese. That is, the United States could possibly be in danger if the Nazis acquired more knowledge about how to build a bomb. [9]

Document 4 : Memo from General Groves to the Chief of Staff [Marshall], “Atomic Fission Bombs – Present Status and Expected Progress,” 7 August 1944, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: RG 77, Correspondence ("Top Secret") of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, file 25M

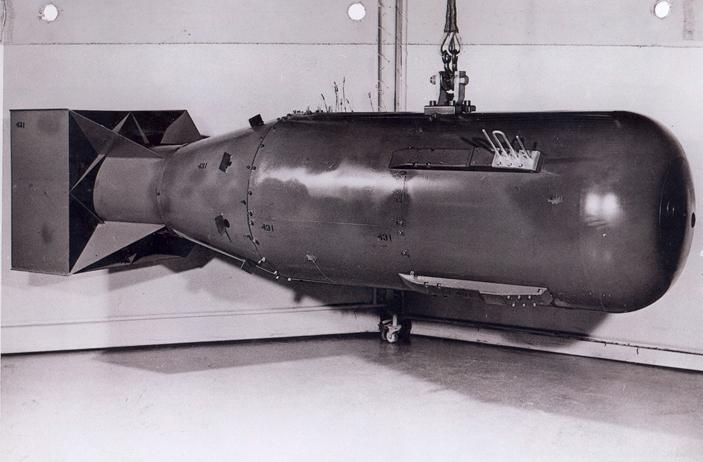

This memorandum from General Groves to General Marshall captured how far the Manhattan Project had come in less than two years since Bush’s December 1942 report to President Roosevelt . Groves did not mention this but around the time he wrote this the Manhattan Project had working at its far-flung installations over 125,000 people ; taking into account high labor turnover some 485,000 people worked on the project (1 out of every 250 people in the country at that time). What these people were laboring to construct, directly or indirectly, were two types of weapons—a gun-type weapon using U-235 and an implosion weapon using plutonium (although the possibility of U-235 was also under consideration). As the scientists had learned, a gun-type weapon based on plutonium was “impossible” because that element had an “unexpected property”: spontaneous neutron emissions would cause the weapon to “fizzle.” [10] For both the gun-type and the implosion weapons, a production schedule had been established and both would be available during 1945. The discussion of weapons effects centered on blast damage models; radiation and other effects were overlooked.

Document 5 : Memorandum from Vannevar Bush and James B. Conant, Office of Scientific Research and Development, to Secretary of War, September 30, 1944, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, Harrison-Bundy Files (H-B Files), folder 69 (copy from microfilm)

While Groves worried about the engineering and production problems, key War Department advisers were becoming troubled over the diplomatic and political implications of these enormously powerful weapons and the dangers of a global nuclear arms race. Concerned that President Roosevelt had an overly “cavalier” belief about the possibility of maintaining a post-war Anglo-American atomic monopoly, Bush and Conant recognized the limits of secrecy and wanted to disabuse senior officials of the notion that an atomic monopoly was possible. To suggest alternatives, they drafted this memorandum about the importance of the international exchange of information and international inspection to stem dangerous nuclear competition. [11]

Documents 6A-D: President Truman Learns the Secret:

6A : Memorandum for the Secretary of War from General L. R. Groves, “Atomic Fission Bombs,” April 23, 1945

6B : Memorandum discussed with the President, April 25, 1945

6C : [Untitled memorandum by General L.R. Groves, April 25, 1945

6D : Diary Entry, April 25, 1945

Sources: A: RG 77, Commanding General’s file no. 24, tab D; B: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress); C: Source: Record Group 200, Papers of General Leslie R. Groves, Correspondence 1941-1970, box 3, “F”; D: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Soon after he was sworn in as president following President Roosevelt’s death, Harry Truman learned about the top secret Manhattan Project from a briefing from Secretary of War Stimson and Manhattan Project chief General Groves, who went through the “back door” to escape the watchful press. Stimson, who later wrote up the meeting in his diary, also prepared a discussion paper, which raised broader policy issues associated with the imminent possession of “the most terrible weapon ever known in human history.” In a background report prepared for the meeting, Groves provided a detailed overview of the bomb project from the raw materials to processing nuclear fuel to assembling the weapons to plans for using them, which were starting to crystallize.

With respect to the point about assembling the weapons, the first gun-type weapon “should be ready about 1 August 1945” while an implosion weapon would also be available that month. “The target is and was always expected to be Japan.” The question whether Truman “inherited assumptions” from the Roosevelt administration that that the bomb would be used has been a controversial one. Alperovitz and Sherwin have argued that Truman made “a real decision” to use the bomb on Japan by choosing “between various forms of diplomacy and warfare.” In contrast, Bernstein found that Truman “never questioned [the] assumption” that the bomb would and should be used. Norris also noted that “Truman’s `decision’ was a decision not to override previous plans to use the bomb.” [12]

II. Targeting Japan

Document 7 : Commander F. L. Ashworth to Major General L.R. Groves, “The Base of Operations of the 509 th Composite Group,” February 24, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5g

The force of B-29 nuclear delivery vehicles that was being readied for first nuclear use—the Army Air Force’s 509 th Composite Group—required an operational base in the Western Pacific. In late February 1945, months before atomic bombs were ready for use, the high command selected Tinian, an island in the Northern Marianas Islands, for that base.

Document 8 : Headquarters XXI Bomber Command, “Tactical Mission Report, Mission No. 40 Flown 10 March 1945,”n.d., Secret

Source: Library of Congress, Curtis LeMay Papers, Box B-36

As part of the war with Japan, the Army Air Force waged a campaign to destroy major industrial centers with incendiary bombs. This document is General Curtis LeMay’s report on the firebombing of Tokyo--“the most destructive air raid in history”--which burned down over 16 square miles of the city, killed up to 100,000 civilians (the official figure was 83,793), injured more than 40,000, and made over 1 million homeless. [13] According to the “Foreword,” the purpose of the raid, which dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs, was to destroy industrial and strategic targets “ not to bomb indiscriminately civilian populations.” Air Force planners, however, did not distinguish civilian workers from the industrial and strategic structures that they were trying to destroy.

The killing of workers in the urban-industrial sector was one of the explicit goals of the air campaign against Japanese cities. According to a Joint Chiefs of Staff report on Japanese target systems, expected results from the bombing campaign included: “The absorption of man-hours in repair and relief; the dislocation of labor by casualty; the interruption of public services necessary to production, and above all the destruction of factories engaged in war industry.” While Stimson would later raise questions about the bombing of Japanese cities, he was largely disengaged from the details (as he was with atomic targeting). [14]

Firebombing raids on other cities followed Tokyo, including Osaka, Kobe, Yokahama, and Nagoya, but with fewer casualties (many civilians had fled the cities). For some historians, the urban fire-bombing strategy facilitated atomic targeting by creating a “new moral context,” in which earlier proscriptions against intentional targeting of civilians had eroded. [15]

Document 9 : Notes on Initial Meeting of Target Committee, May 2, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5d (copy from microfilm)

On 27 April, military officers and nuclear scientists met to discuss bombing techniques, criteria for target selection, and overall mission requirements. The discussion of “available targets” included Hiroshima, the “largest untouched target not on the 21 st Bomber Command priority list.” But other targets were under consideration, including Yawata (northern Kyushu), Yokohama, and Tokyo (even though it was practically “rubble.”) The problem was that the Air Force had a policy of “laying waste” to Japan’s cities which created tension with the objective of reserving some urban targets for nuclear destruction. [16]

Document 10 : Memorandum from J. R. Oppenheimer to Brigadier General Farrell, May 11, 1945

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5g (copy from microfilm)

As director of Los Alamos Laboratory, Oppenheimer’s priority was producing a deliverable bomb, but not so much the effects of the weapon on the people at the target. In keeping with General Groves’ emphasis on compartmentalization, the Manhattan Project experts on the effects of radiation on human biology were at the MetLab and other offices and had no interaction with the production and targeting units. In this short memorandum to Groves’ deputy, General Farrell, Oppenheimer explained the need for precautions because of the radiological dangers of a nuclear detonation. The initial radiation from the detonation would be fatal within a radius of about 6/10ths of a mile and “injurious” within a radius of a mile. The point was to keep the bombing mission crew safe; concern about radiation effects had no impact on targeting decisions. [17]

Document 11 : Memorandum from Major J. A. Derry and Dr. N.F. Ramsey to General L.R. Groves, “Summary of Target Committee Meetings on 10 and 11 May 1945,” May 12, 1945, Top Secret

Scientists and officers held further discussion of bombing mission requirements, including height of detonation, weather, radiation effects (Oppenheimer’s memo), plans for possible mission abort, and the various aspects of target selection, including priority cities (“a large urban area of more than three miles diameter”) and psychological dimension. As for target cities, the committee agreed that the following should be exempt from Army Air Force bombing so they would be available for nuclear targeting: Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura Arsenal. Japan’s cultural capital, Kyoto, would not stay on the list. Pressure from Secretary of War Stimson had already taken Kyoto off the list of targets for incendiary bombings and he would successfully object to the atomic bombing of that city. [18]

Document 12 : Stimson Diary Entries, May 14 and 15, 1945

Source: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

On May 14 and 15, Stimson had several conversations involving S-1 (the atomic bomb); during a talk with Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, he estimated that possession of the bomb gave Washington a tremendous advantage—“held all the cards,” a “royal straight flush”-- in dealing with Moscow on post-war problems: “They can’t get along without our help and industries and we have coming into action a weapon which will be unique.” The next day a discussion of divergences with Moscow over the Far East made Stimson wonder whether the atomic bomb would be ready when Truman met with Stalin in July. If it was, he believed that the bomb would be the “master card” in U.S. diplomacy. This and other entries from the Stimson diary (as well as the entry from the Davies diary that follows) are important to arguments developed by Gar Alperovitz and Barton J. Bernstein, among others, although with significantly different emphases, that in light of controversies with the Soviet Union over Eastern Europe and other areas, top officials in the Truman administration believed that possessing the atomic bomb would provide them with significant leverage for inducing Moscow’s acquiescence in U.S. objectives. [19]

Document 13 : Davies Diary entry for May 21, 1945

Source: Joseph E. Davies Papers, Library of Congress, box 17, 21 May 1945

While officials at the Pentagon continued to look closely at the problem of atomic targets, President Truman, like Stimson, was thinking about the diplomatic implications of the bomb. During a conversation with Joseph E. Davies, a prominent Washington lawyer and former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Truman said that he wanted to delay talks with Stalin and Churchill until July when the first atomic device had been tested. Alperovitz treated this entry as evidence in support of the atomic diplomacy argument, but other historians, ranging from Robert Maddox to Gabriel Kolko, have denied that the timing of the Potsdam conference had anything to do with the goal of using the bomb to intimidate the Soviets. [20]

Document 14 : Letter, O. C. Brewster to President Truman, 24 May 1945, with note from Stimson to Marshall, 30 May 1945, attached, secret

Source: Harrison-Bundy Files relating to the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1108 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), File 77: "Interim Committee - International Control."

In what Stimson called the “letter of an honest man,” Oswald C. Brewster sent President Truman a profound analysis of the danger and unfeasibility of a U.S. atomic monopoly. [21] An engineer for the Kellex Corporation, which was involved in the gas diffusion project to enrich uranium, Brewster recognized that the objective was fissile material for a weapon. That goal, he feared, raised terrifying prospects with implications for the “inevitable destruction of our present day civilization.” Once the U.S. had used the bomb in combat other great powers would not tolerate a monopoly by any nation and the sole possessor would be “be the most hated and feared nation on earth.” Even the U.S.’s closest allies would want the bomb because “how could they know where our friendship might be five, ten, or twenty years hence.” Nuclear proliferation and arms races would be certain unless the U.S. worked toward international supervision and inspection of nuclear plants.

Brewster suggested that Japan could be used as a “target” for a “demonstration” of the bomb, which he did not further define. His implicit preference, however, was for non-use; he wrote that it would be better to take U.S. casualties in “conquering Japan” than “to bring upon the world the tragedy of unrestrained competitive production of this material.”

Document 15 : Minutes of Third Target Committee Meeting – Washington, May 28, 1945, Top Secret

More updates on training missions, target selection, and conditions required for successful detonation over the target. The target would be a city--either Hiroshima, Kyoto (still on the list), or Niigata--but specific “aiming points” would not be specified at that time nor would industrial “pin point” targets because they were likely to be on the “fringes” a city. The bomb would be dropped in the city’s center. “Pumpkins” referred to bright orange, pumpkin-shaped high explosive bombs—shaped like the “Fat Man” implosion weapon--used for bombing run test missions.

Document 16 : General Lauris Norstad to Commanding General, XXI Bomber Command, “509 th Composite Group; Special Functions,” May 29, 1945, Top Secret

The 509 th Composite Group’s cover story for its secret mission was the preparation of “Pumpkins” for use in battle. In this memorandum, Norstad reviewed the complex requirements for preparing B-29s and their crew for successful nuclear strikes.

Document 17 : Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, “Memorandum of Conversation with General Marshal May 29, 1945 – 11:45 p.m.,” Top Secret

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson (“Safe File”), July 1940-September 1945, box 12, S-1

Tacitly dissenting from the Targeting Committee’s recommendations, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall argued for initial nuclear use against a clear-cut military target such as a “large naval installation.” If that did not work, manufacturing areas could be targeted, but only after warning their inhabitants. Marshall noted the “opprobrium which might follow from an ill considered employment of such force.” This document has played a role in arguments developed by Barton J. Bernstein that figures such as Marshall and Stimson were “caught between an older morality that opposed the intentional killing of non-combatants and a newer one that stressed virtually total war.” [22]

Document 18 : “Notes of the Interim Committee Meeting Thursday, 31 May 1945, 10:00 A.M. to 1:15 P.M. – 2:15 P.M. to 4:15 P.M., ” n.d., Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100 (copy from microfilm)

With Secretary of War Stimson presiding, members of the committee heard reports on a variety of Manhattan Project issues, including the stages of development of the atomic project, problems of secrecy, the possibility of informing the Soviet Union, cooperation with “like-minded” powers, the military impact of the bomb on Japan, and the problem of “undesirable scientists.” Interested in producing the “greatest psychological effect,” the Committee members agreed that the “most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.” Exactly how the mass deaths of civilians would persuade Japanese rulers to surrender was not discussed. Bernstein has argued that this target choice represented an uneasy endorsement of “terror bombing”--the target was not exclusively military or civilian; nevertheless, worker’s housing would include non-combatant men, women, and children. [23] It is possible that Truman was informed of such discussions and their conclusions, although he clung to a belief that the prospective targets were strictly military.

Document 19 : General George A. Lincoln to General Hull, June 4, 1945, enclosing draft, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 165, Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, American-British-Canadian Top Secret Correspondence, Box 504, “ABC 387 Japan (15 Feb. 45)

George A. Lincoln, chief of the Strategy and Policy Group at U.S. Army’s Operations Department, commented on a memorandum by former President Herbert Hoover that Stimson had passed on for analysis. Hoover proposed a compromise solution with Japan that would allow Tokyo to retain part of its empire in East Asia (including Korea and Japan) as a way to head off Soviet influence in the region. While Lincoln believed that the proposed peace teams were militarily acceptable he doubted that they were workable or that they could check Soviet “expansion” which he saw as an inescapable result of World War II. As to how the war with Japan would end, he saw it as “unpredictable,” but speculated that “it will take Russian entry into the war, combined with a landing, or imminent threat of a landing, on Japan proper by us, to convince them of the hopelessness of their situation.” Lincoln derided Hoover’s casualty estimate of 500,000. J. Samuel Walker has cited this document to make the point that “contrary to revisionist assertions, American policymakers in the summer of 1945 were far from certain that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria would be enough in itself to force a Japanese surrender.” [24]

Document 20 : Memorandum from R. Gordon Arneson, Interim Committee Secretary, to Mr. Harrison, June 6, 1945, Top Secret

In a memorandum to George Harrison, Stimson’s special assistant on Manhattan Project matters, Arneson noted actions taken at the recent Interim Committee meetings, including target criterion and an attack “without prior warning.”

Document 21 : Memorandum of Conference with the President, June 6, 1945, Top Secret

Source: Henry Stimson Papers, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Stimson and Truman began this meeting by discussing how they should handle a conflict with French President DeGaulle over the movement by French forces into Italian territory. (Truman finally cut off military aid to France to compel the French to pull back). [25] As evident from the discussion, Stimson strongly disliked de Gaulle whom he regarded as “psychopathic.” The conversation soon turned to the atomic bomb, with some discussion about plans to inform the Soviets but only after a successful test. Both agreed that the possibility of a nuclear “partnership” with Moscow would depend on “quid pro quos”: “the settlement of the Polish, Rumanian, Yugoslavian, and Manchurian problems.”

At the end, Stimson shared his doubts about targeting cities and killing civilians through area bombing because of its impact on the U.S.’s reputation as well as on the problem of finding targets for the atomic bomb. Barton Bernstein has also pointed to this as additional evidence of the influence on Stimson of an “an older morality.” While concerned about the U.S.’s reputation, Stimson did not want the Air Force to bomb Japanese cities so thoroughly that the “new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength,” a comment that made Truman laugh. The discussion of “area bombing” may have reminded him that Japanese civilians remained at risk from U.S. bombing operations.

III. Debates on Alternatives to First Use and Unconditional Surrender

Document 22 : Memorandum from Arthur B. Compton to the Secretary of War, enclosing “Memorandum on `Political and Social Problems,’ from Members of the `Metallurgical Laboratory’ of the University of Chicago,” June 12, 1945, Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 76 (copy from microfilm)