45 Research Problem Examples & Inspiration

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

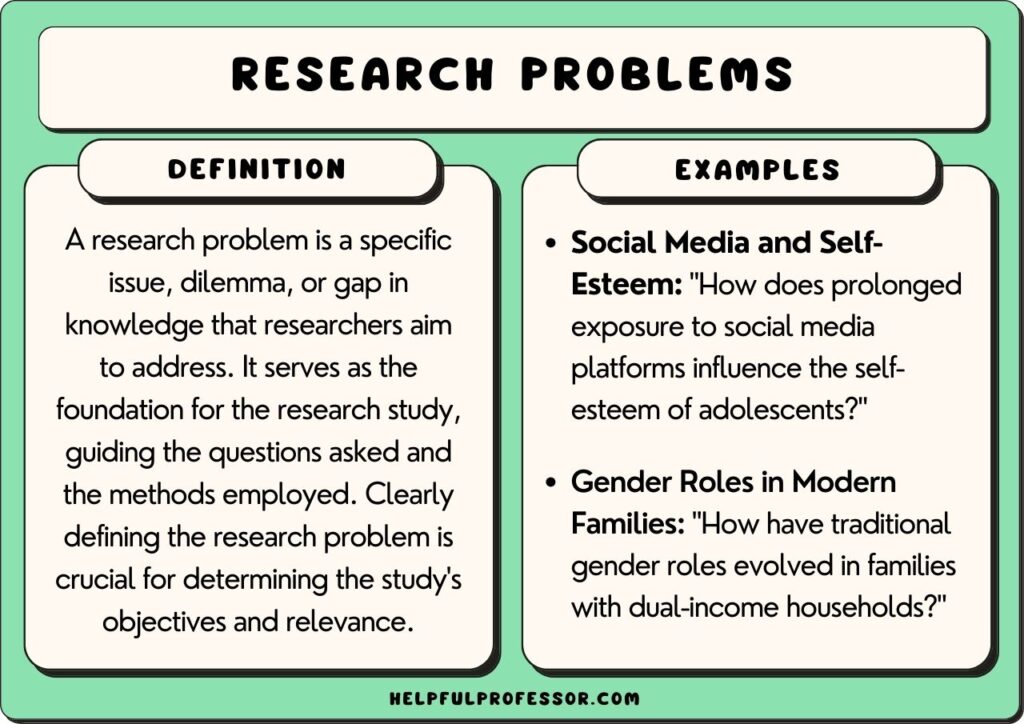

A research problem is an issue of concern that is the catalyst for your research. It demonstrates why the research problem needs to take place in the first place.

Generally, you will write your research problem as a clear, concise, and focused statement that identifies an issue or gap in current knowledge that requires investigation.

The problem will likely also guide the direction and purpose of a study. Depending on the problem, you will identify a suitable methodology that will help address the problem and bring solutions to light.

Research Problem Examples

In the following examples, I’ll present some problems worth addressing, and some suggested theoretical frameworks and research methodologies that might fit with the study. Note, however, that these aren’t the only ways to approach the problems. Keep an open mind and consult with your dissertation supervisor!

Psychology Problems

1. Social Media and Self-Esteem: “How does prolonged exposure to social media platforms influence the self-esteem of adolescents?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Comparison Theory

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking adolescents’ social media usage and self-esteem measures over time, combined with qualitative interviews.

2. Sleep and Cognitive Performance: “How does sleep quality and duration impact cognitive performance in adults?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Psychology

- Methodology : Experimental design with controlled sleep conditions, followed by cognitive tests. Participant sleep patterns can also be monitored using actigraphy.

3. Childhood Trauma and Adult Relationships: “How does unresolved childhood trauma influence attachment styles and relationship dynamics in adulthood?

- Theoretical Framework : Attachment Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of attachment styles with qualitative in-depth interviews exploring past trauma and current relationship dynamics.

4. Mindfulness and Stress Reduction: “How effective is mindfulness meditation in reducing perceived stress and physiological markers of stress in working professionals?”

- Theoretical Framework : Humanist Psychology

- Methodology : Randomized controlled trial comparing a group practicing mindfulness meditation to a control group, measuring both self-reported stress and physiological markers (e.g., cortisol levels).

5. Implicit Bias and Decision Making: “To what extent do implicit biases influence decision-making processes in hiring practices?

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design using Implicit Association Tests (IAT) to measure implicit biases, followed by simulated hiring tasks to observe decision-making behaviors.

6. Emotional Regulation and Academic Performance: “How does the ability to regulate emotions impact academic performance in college students?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Theory of Emotion

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys measuring emotional regulation strategies, combined with academic performance metrics (e.g., GPA).

7. Nature Exposure and Mental Well-being: “Does regular exposure to natural environments improve mental well-being and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression?”

- Theoretical Framework : Biophilia Hypothesis

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing mental health measures of individuals with regular nature exposure to those without, possibly using ecological momentary assessment for real-time data collection.

8. Video Games and Cognitive Skills: “How do action video games influence cognitive skills such as attention, spatial reasoning, and problem-solving?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Load Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design with pre- and post-tests, comparing cognitive skills of participants before and after a period of action video game play.

9. Parenting Styles and Child Resilience: “How do different parenting styles influence the development of resilience in children facing adversities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Baumrind’s Parenting Styles Inventory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of resilience and parenting styles with qualitative interviews exploring children’s experiences and perceptions.

10. Memory and Aging: “How does the aging process impact episodic memory , and what strategies can mitigate age-related memory decline?

- Theoretical Framework : Information Processing Theory

- Methodology : Cross-sectional study comparing episodic memory performance across different age groups, combined with interventions like memory training or mnemonic strategies to assess potential improvements.

Education Problems

11. Equity and Access : “How do socioeconomic factors influence students’ access to quality education, and what interventions can bridge the gap?

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Pedagogy

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative data on student outcomes with qualitative interviews and focus groups with students, parents, and educators.

12. Digital Divide : How does the lack of access to technology and the internet affect remote learning outcomes, and how can this divide be addressed?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Construction of Technology Theory

- Methodology : Survey research to gather data on access to technology, followed by case studies in selected areas.

13. Teacher Efficacy : “What factors contribute to teacher self-efficacy, and how does it impact student achievement?”

- Theoretical Framework : Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys to measure teacher self-efficacy, combined with qualitative interviews to explore factors affecting it.

14. Curriculum Relevance : “How can curricula be made more relevant to diverse student populations, incorporating cultural and local contexts?”

- Theoretical Framework : Sociocultural Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of curricula, combined with focus groups with students and teachers.

15. Special Education : “What are the most effective instructional strategies for students with specific learning disabilities?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional strategies, with pre- and post-tests to measure student achievement.

16. Dropout Rates : “What factors contribute to high school dropout rates, and what interventions can help retain students?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking students over time, combined with interviews with dropouts.

17. Bilingual Education : “How does bilingual education impact cognitive development and academic achievement?

- Methodology : Comparative study of students in bilingual vs. monolingual programs, using standardized tests and qualitative interviews.

18. Classroom Management: “What reward strategies are most effective in managing diverse classrooms and promoting a positive learning environment?

- Theoretical Framework : Behaviorism (e.g., Skinner’s Operant Conditioning)

- Methodology : Observational research in classrooms , combined with teacher interviews.

19. Standardized Testing : “How do standardized tests affect student motivation, learning, and curriculum design?”

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative analysis of test scores and student outcomes, combined with qualitative interviews with educators and students.

20. STEM Education : “What methods can be employed to increase interest and proficiency in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields among underrepresented student groups?”

- Theoretical Framework : Constructivist Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional methods, with pre- and post-tests.

21. Social-Emotional Learning : “How can social-emotional learning be effectively integrated into the curriculum, and what are its impacts on student well-being and academic outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of student well-being with qualitative interviews.

22. Parental Involvement : “How does parental involvement influence student achievement, and what strategies can schools use to increase it?”

- Theoretical Framework : Reggio Emilia’s Model (Community Engagement Focus)

- Methodology : Survey research with parents and teachers, combined with case studies in selected schools.

23. Early Childhood Education : “What are the long-term impacts of quality early childhood education on academic and life outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing students with and without early childhood education, combined with observational research.

24. Teacher Training and Professional Development : “How can teacher training programs be improved to address the evolving needs of the 21st-century classroom?”

- Theoretical Framework : Adult Learning Theory (Andragogy)

- Methodology : Pre- and post-assessments of teacher competencies, combined with focus groups.

25. Educational Technology : “How can technology be effectively integrated into the classroom to enhance learning, and what are the potential drawbacks or challenges?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing classrooms with and without specific technologies, combined with teacher and student interviews.

Sociology Problems

26. Urbanization and Social Ties: “How does rapid urbanization impact the strength and nature of social ties in communities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Structural Functionalism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on social ties with qualitative interviews in urbanizing areas.

27. Gender Roles in Modern Families: “How have traditional gender roles evolved in families with dual-income households?”

- Theoretical Framework : Gender Schema Theory

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with dual-income families, combined with historical data analysis.

28. Social Media and Collective Behavior: “How does social media influence collective behaviors and the formation of social movements?”

- Theoretical Framework : Emergent Norm Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of social media platforms, combined with quantitative surveys on participation in social movements.

29. Education and Social Mobility: “To what extent does access to quality education influence social mobility in socioeconomically diverse settings?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking educational access and subsequent socioeconomic status, combined with qualitative interviews.

30. Religion and Social Cohesion: “How do religious beliefs and practices contribute to social cohesion in multicultural societies?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys on religious beliefs and perceptions of social cohesion, combined with ethnographic studies.

31. Consumer Culture and Identity Formation: “How does consumer culture influence individual identity formation and personal values?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Identity Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining content analysis of advertising with qualitative interviews on identity and values.

32. Migration and Cultural Assimilation: “How do migrants negotiate cultural assimilation and preservation of their original cultural identities in their host countries?”

- Theoretical Framework : Post-Structuralism

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with migrants, combined with observational studies in multicultural communities.

33. Social Networks and Mental Health: “How do social networks, both online and offline, impact mental health and well-being?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Network Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social network characteristics and mental health metrics, combined with qualitative interviews.

34. Crime, Deviance, and Social Control: “How do societal norms and values shape definitions of crime and deviance, and how are these definitions enforced?”

- Theoretical Framework : Labeling Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of legal documents and media, combined with ethnographic studies in diverse communities.

35. Technology and Social Interaction: “How has the proliferation of digital technology influenced face-to-face social interactions and community building?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Determinism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on technology use with qualitative observations of social interactions in various settings.

Nursing Problems

36. Patient Communication and Recovery: “How does effective nurse-patient communication influence patient recovery rates and overall satisfaction with care?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing patient satisfaction and recovery metrics, combined with observational studies on nurse-patient interactions.

37. Stress Management in Nursing: “What are the primary sources of occupational stress for nurses, and how can they be effectively managed to prevent burnout?”

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of stress and burnout with qualitative interviews exploring personal experiences and coping mechanisms.

38. Hand Hygiene Compliance: “How effective are different interventions in improving hand hygiene compliance among nursing staff, and what are the barriers to consistent hand hygiene?”

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing hand hygiene rates before and after specific interventions, combined with focus groups to understand barriers.

39. Nurse-Patient Ratios and Patient Outcomes: “How do nurse-patient ratios impact patient outcomes, including recovery rates, complications, and hospital readmissions?”

- Methodology : Quantitative study analyzing patient outcomes in relation to staffing levels, possibly using retrospective chart reviews.

40. Continuing Education and Clinical Competence: “How does regular continuing education influence clinical competence and confidence among nurses?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking nurses’ clinical skills and confidence over time as they engage in continuing education, combined with patient outcome measures to assess potential impacts on care quality.

Communication Studies Problems

41. Media Representation and Public Perception: “How does media representation of minority groups influence public perceptions and biases?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cultivation Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of media representations combined with quantitative surveys assessing public perceptions and attitudes.

42. Digital Communication and Relationship Building: “How has the rise of digital communication platforms impacted the way individuals build and maintain personal relationships?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Penetration Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on digital communication habits with qualitative interviews exploring personal relationship dynamics.

43. Crisis Communication Effectiveness: “What strategies are most effective in managing public relations during organizational crises, and how do they influence public trust?”

- Theoretical Framework : Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

- Methodology : Case study analysis of past organizational crises, assessing communication strategies used and subsequent public trust metrics.

44. Nonverbal Cues in Virtual Communication: “How do nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and gestures, influence message interpretation in virtual communication platforms?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Semiotics

- Methodology : Experimental design using video conferencing tools, analyzing participants’ interpretations of messages with varying nonverbal cues.

45. Influence of Social Media on Political Engagement: “How does exposure to political content on social media platforms influence individuals’ political engagement and activism?”

- Theoretical Framework : Uses and Gratifications Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social media habits and political engagement levels, combined with content analysis of political posts on popular platforms.

Before you Go: Tips and Tricks for Writing a Research Problem

This is an incredibly stressful time for research students. The research problem is going to lock you into a specific line of inquiry for the rest of your studies.

So, here’s what I tend to suggest to my students:

- Start with something you find intellectually stimulating – Too many students choose projects because they think it hasn’t been studies or they’ve found a research gap. Don’t over-estimate the importance of finding a research gap. There are gaps in every line of inquiry. For now, just find a topic you think you can really sink your teeth into and will enjoy learning about.

- Take 5 ideas to your supervisor – Approach your research supervisor, professor, lecturer, TA, our course leader with 5 research problem ideas and run each by them. The supervisor will have valuable insights that you didn’t consider that will help you narrow-down and refine your problem even more.

- Trust your supervisor – The supervisor-student relationship is often very strained and stressful. While of course this is your project, your supervisor knows the internal politics and conventions of academic research. The depth of knowledge about how to navigate academia and get you out the other end with your degree is invaluable. Don’t underestimate their advice.

I’ve got a full article on all my tips and tricks for doing research projects right here – I recommend reading it:

- 9 Tips on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 101 Class Group Name Ideas (for School Students)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Research Problem

Definition:

Research problem is a specific and well-defined issue or question that a researcher seeks to investigate through research. It is the starting point of any research project, as it sets the direction, scope, and purpose of the study.

Types of Research Problems

Types of Research Problems are as follows:

Descriptive problems

These problems involve describing or documenting a particular phenomenon, event, or situation. For example, a researcher might investigate the demographics of a particular population, such as their age, gender, income, and education.

Exploratory problems

These problems are designed to explore a particular topic or issue in depth, often with the goal of generating new ideas or hypotheses. For example, a researcher might explore the factors that contribute to job satisfaction among employees in a particular industry.

Explanatory Problems

These problems seek to explain why a particular phenomenon or event occurs, and they typically involve testing hypotheses or theories. For example, a researcher might investigate the relationship between exercise and mental health, with the goal of determining whether exercise has a causal effect on mental health.

Predictive Problems

These problems involve making predictions or forecasts about future events or trends. For example, a researcher might investigate the factors that predict future success in a particular field or industry.

Evaluative Problems

These problems involve assessing the effectiveness of a particular intervention, program, or policy. For example, a researcher might evaluate the impact of a new teaching method on student learning outcomes.

How to Define a Research Problem

Defining a research problem involves identifying a specific question or issue that a researcher seeks to address through a research study. Here are the steps to follow when defining a research problem:

- Identify a broad research topic : Start by identifying a broad topic that you are interested in researching. This could be based on your personal interests, observations, or gaps in the existing literature.

- Conduct a literature review : Once you have identified a broad topic, conduct a thorough literature review to identify the current state of knowledge in the field. This will help you identify gaps or inconsistencies in the existing research that can be addressed through your study.

- Refine the research question: Based on the gaps or inconsistencies identified in the literature review, refine your research question to a specific, clear, and well-defined problem statement. Your research question should be feasible, relevant, and important to the field of study.

- Develop a hypothesis: Based on the research question, develop a hypothesis that states the expected relationship between variables.

- Define the scope and limitations: Clearly define the scope and limitations of your research problem. This will help you focus your study and ensure that your research objectives are achievable.

- Get feedback: Get feedback from your advisor or colleagues to ensure that your research problem is clear, feasible, and relevant to the field of study.

Components of a Research Problem

The components of a research problem typically include the following:

- Topic : The general subject or area of interest that the research will explore.

- Research Question : A clear and specific question that the research seeks to answer or investigate.

- Objective : A statement that describes the purpose of the research, what it aims to achieve, and the expected outcomes.

- Hypothesis : An educated guess or prediction about the relationship between variables, which is tested during the research.

- Variables : The factors or elements that are being studied, measured, or manipulated in the research.

- Methodology : The overall approach and methods that will be used to conduct the research.

- Scope and Limitations : A description of the boundaries and parameters of the research, including what will be included and excluded, and any potential constraints or limitations.

- Significance: A statement that explains the potential value or impact of the research, its contribution to the field of study, and how it will add to the existing knowledge.

Research Problem Examples

Following are some Research Problem Examples:

Research Problem Examples in Psychology are as follows:

- Exploring the impact of social media on adolescent mental health.

- Investigating the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating anxiety disorders.

- Studying the impact of prenatal stress on child development outcomes.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to addiction and relapse in substance abuse treatment.

- Examining the impact of personality traits on romantic relationships.

Research Problem Examples in Sociology are as follows:

- Investigating the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes in marginalized communities.

- Studying the impact of globalization on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of gentrification in urban neighborhoods.

- Investigating the impact of family structure on social mobility and economic outcomes.

- Examining the effects of social capital on community development and resilience.

Research Problem Examples in Economics are as follows:

- Studying the effects of trade policies on economic growth and development.

- Analyzing the impact of automation and artificial intelligence on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Investigating the factors that contribute to economic inequality and poverty.

- Examining the impact of fiscal and monetary policies on inflation and economic stability.

- Studying the relationship between education and economic outcomes, such as income and employment.

Political Science

Research Problem Examples in Political Science are as follows:

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of political polarization and partisan behavior.

- Investigating the impact of social movements on political change and policymaking.

- Studying the role of media and communication in shaping public opinion and political discourse.

- Examining the effectiveness of electoral systems in promoting democratic governance and representation.

- Investigating the impact of international organizations and agreements on global governance and security.

Environmental Science

Research Problem Examples in Environmental Science are as follows:

- Studying the impact of air pollution on human health and well-being.

- Investigating the effects of deforestation on climate change and biodiversity loss.

- Analyzing the impact of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and food webs.

- Studying the relationship between urban development and ecological resilience.

- Examining the effectiveness of environmental policies and regulations in promoting sustainability and conservation.

Research Problem Examples in Education are as follows:

- Investigating the impact of teacher training and professional development on student learning outcomes.

- Studying the effectiveness of technology-enhanced learning in promoting student engagement and achievement.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to achievement gaps and educational inequality.

- Examining the impact of parental involvement on student motivation and achievement.

- Studying the effectiveness of alternative educational models, such as homeschooling and online learning.

Research Problem Examples in History are as follows:

- Analyzing the social and economic factors that contributed to the rise and fall of ancient civilizations.

- Investigating the impact of colonialism on indigenous societies and cultures.

- Studying the role of religion in shaping political and social movements throughout history.

- Analyzing the impact of the Industrial Revolution on economic and social structures.

- Examining the causes and consequences of global conflicts, such as World War I and II.

Research Problem Examples in Business are as follows:

- Studying the impact of corporate social responsibility on brand reputation and consumer behavior.

- Investigating the effectiveness of leadership development programs in improving organizational performance and employee satisfaction.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful entrepreneurship and small business development.

- Examining the impact of mergers and acquisitions on market competition and consumer welfare.

- Studying the effectiveness of marketing strategies and advertising campaigns in promoting brand awareness and sales.

Research Problem Example for Students

An Example of a Research Problem for Students could be:

“How does social media usage affect the academic performance of high school students?”

This research problem is specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular area of interest, which is the impact of social media on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on social media usage and academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because it addresses a current and important issue that affects high school students.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use various methods, such as surveys, interviews, and statistical analysis of academic records. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between social media usage and academic performance, which could help educators and parents develop effective strategies for managing social media use among students.

Another example of a research problem for students:

“Does participation in extracurricular activities impact the academic performance of middle school students?”

This research problem is also specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular type of activity, extracurricular activities, and its impact on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on students’ participation in extracurricular activities and their academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because extracurricular activities are an essential part of the middle school experience, and their impact on academic performance is a topic of interest to educators and parents.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use surveys, interviews, and academic records analysis. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between extracurricular activities and academic performance, which could help educators and parents make informed decisions about the types of activities that are most beneficial for middle school students.

Applications of Research Problem

Applications of Research Problem are as follows:

- Academic research: Research problems are used to guide academic research in various fields, including social sciences, natural sciences, humanities, and engineering. Researchers use research problems to identify gaps in knowledge, address theoretical or practical problems, and explore new areas of study.

- Business research : Research problems are used to guide business research, including market research, consumer behavior research, and organizational research. Researchers use research problems to identify business challenges, explore opportunities, and develop strategies for business growth and success.

- Healthcare research : Research problems are used to guide healthcare research, including medical research, clinical research, and health services research. Researchers use research problems to identify healthcare challenges, develop new treatments and interventions, and improve healthcare delivery and outcomes.

- Public policy research : Research problems are used to guide public policy research, including policy analysis, program evaluation, and policy development. Researchers use research problems to identify social issues, assess the effectiveness of existing policies and programs, and develop new policies and programs to address societal challenges.

- Environmental research : Research problems are used to guide environmental research, including environmental science, ecology, and environmental management. Researchers use research problems to identify environmental challenges, assess the impact of human activities on the environment, and develop sustainable solutions to protect the environment.

Purpose of Research Problems

The purpose of research problems is to identify an area of study that requires further investigation and to formulate a clear, concise and specific research question. A research problem defines the specific issue or problem that needs to be addressed and serves as the foundation for the research project.

Identifying a research problem is important because it helps to establish the direction of the research and sets the stage for the research design, methods, and analysis. It also ensures that the research is relevant and contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the field.

A well-formulated research problem should:

- Clearly define the specific issue or problem that needs to be investigated

- Be specific and narrow enough to be manageable in terms of time, resources, and scope

- Be relevant to the field of study and contribute to the existing body of knowledge

- Be feasible and realistic in terms of available data, resources, and research methods

- Be interesting and intellectually stimulating for the researcher and potential readers or audiences.

Characteristics of Research Problem

The characteristics of a research problem refer to the specific features that a problem must possess to qualify as a suitable research topic. Some of the key characteristics of a research problem are:

- Clarity : A research problem should be clearly defined and stated in a way that it is easily understood by the researcher and other readers. The problem should be specific, unambiguous, and easy to comprehend.

- Relevance : A research problem should be relevant to the field of study, and it should contribute to the existing body of knowledge. The problem should address a gap in knowledge, a theoretical or practical problem, or a real-world issue that requires further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem should be feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It should be realistic and practical to conduct the study within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem should be novel or original in some way. It should represent a new or innovative perspective on an existing problem, or it should explore a new area of study or apply an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem should be important or significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It should have the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Manageability : A research problem should be manageable in terms of its scope and complexity. It should be specific enough to be investigated within the available time and resources, and it should be broad enough to provide meaningful results.

Advantages of Research Problem

The advantages of a well-defined research problem are as follows:

- Focus : A research problem provides a clear and focused direction for the research study. It ensures that the study stays on track and does not deviate from the research question.

- Clarity : A research problem provides clarity and specificity to the research question. It ensures that the research is not too broad or too narrow and that the research objectives are clearly defined.

- Relevance : A research problem ensures that the research study is relevant to the field of study and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. It addresses gaps in knowledge, theoretical or practical problems, or real-world issues that require further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem ensures that the research study is feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It ensures that the research is realistic and practical to conduct within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem ensures that the research study is original and innovative. It represents a new or unique perspective on an existing problem, explores a new area of study, or applies an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem ensures that the research study is important and significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It has the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Rigor : A research problem ensures that the research study is rigorous and follows established research methods and practices. It ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic, objective, and unbiased manner.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Research Approach – Types Methods and Examples

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and...

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Issues surrounding researching in schools

There are tens of thousands of schools in the United Kingdom, which means that observational research which focuses on just one, or a handful of schools will be unrepresentative. This is also a problem with any of the popular documentary programmes which focus on just one school – they are very interesting as they focus on the stories of the school, and some (but only some) of the pupils and teachers, but they are never going to be representative of all schools!

There are a lot of official statistics available on schools, much of it freely available on the DFES website – information on results, attendance, exclusions are all available, as are the latest OFSTED reports, so using a mixture of secondary qualitative and quantitative data may be a good choice for researchers given that schools are ‘data rich’ institutions.

A researcher could also use official statistics to easily select a sample of schools which represent all the regions in the UK, different OFSTED grades, and/ or different school types.

However, official statistics on education can be misleading – exam results may not reflect the underlying ethos of a school, or show us the difficulties a particular school faces, and schools can manipulate their data to an extent – for example, they can reduce their exclusion statistics by ‘off-rolling pupils’ – getting parents to agree to withdraw them before they exclude them.

Schools are potentially very convenient places to conduct research – because the law requires pupils to attend and teachers/ managers need to attend to keep their jobs, you can be reasonably certain that most people you want to research are going to be in attendance! You have a captive audience!

However, school gatekeepers (i.e. head teachers) may be reluctant to allow researchers into schools: they may see research as disruptive, fearing it may interfere with their duty to educate students.

Schools are also highly organised, ‘busy’ institutions – researchers may find it difficult to find the time to ask questions of pupils and teachers during the day, meaning interviews could be a problem, limiting the researcher to less representative observational research.

The researcher will also need to ensure they blend-in, otherwise they may be seen as an outsider by teachers and students alike, which would not be conducive to getting respondents to open up and provide valid information.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

- Our Mission

The 10 Most Significant Education Studies of 2020

We reviewed hundreds of educational studies in 2020 and then highlighted 10 of the most significant—covering topics from virtual learning to the reading wars and the decline of standardized tests.

In the month of March of 2020, the year suddenly became a whirlwind. With a pandemic disrupting life across the entire globe, teachers scrambled to transform their physical classrooms into virtual—or even hybrid—ones, and researchers slowly began to collect insights into what works, and what doesn’t, in online learning environments around the world.

Meanwhile, neuroscientists made a convincing case for keeping handwriting in schools, and after the closure of several coal-fired power plants in Chicago, researchers reported a drop in pediatric emergency room visits and fewer absences in schools, reminding us that questions of educational equity do not begin and end at the schoolhouse door.

1. To Teach Vocabulary, Let Kids Be Thespians

When students are learning a new language, ask them to act out vocabulary words. It’s fun to unleash a child’s inner thespian, of course, but a 2020 study concluded that it also nearly doubles their ability to remember the words months later.

Researchers asked 8-year-old students to listen to words in another language and then use their hands and bodies to mimic the words—spreading their arms and pretending to fly, for example, when learning the German word flugzeug , which means “airplane.” After two months, these young actors were a remarkable 73 percent more likely to remember the new words than students who had listened without accompanying gestures. Researchers discovered similar, if slightly less dramatic, results when students looked at pictures while listening to the corresponding vocabulary.

It’s a simple reminder that if you want students to remember something, encourage them to learn it in a variety of ways—by drawing it , acting it out, or pairing it with relevant images , for example.

2. Neuroscientists Defend the Value of Teaching Handwriting—Again

For most kids, typing just doesn’t cut it. In 2012, brain scans of preliterate children revealed crucial reading circuitry flickering to life when kids hand-printed letters and then tried to read them. The effect largely disappeared when the letters were typed or traced.

More recently, in 2020, a team of researchers studied older children—seventh graders—while they handwrote, drew, and typed words, and concluded that handwriting and drawing produced telltale neural tracings indicative of deeper learning.

“Whenever self-generated movements are included as a learning strategy, more of the brain gets stimulated,” the researchers explain, before echoing the 2012 study: “It also appears that the movements related to keyboard typing do not activate these networks the same way that drawing and handwriting do.”

It would be a mistake to replace typing with handwriting, though. All kids need to develop digital skills, and there’s evidence that technology helps children with dyslexia to overcome obstacles like note taking or illegible handwriting, ultimately freeing them to “use their time for all the things in which they are gifted,” says the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity.

3. The ACT Test Just Got a Negative Score (Face Palm)

A 2020 study found that ACT test scores, which are often a key factor in college admissions, showed a weak—or even negative —relationship when it came to predicting how successful students would be in college. “There is little evidence that students will have more college success if they work to improve their ACT score,” the researchers explain, and students with very high ACT scores—but indifferent high school grades—often flamed out in college, overmatched by the rigors of a university’s academic schedule.

Just last year, the SAT—cousin to the ACT—had a similarly dubious public showing. In a major 2019 study of nearly 50,000 students led by researcher Brian Galla, and including Angela Duckworth, researchers found that high school grades were stronger predictors of four-year-college graduation than SAT scores.

The reason? Four-year high school grades, the researchers asserted, are a better indicator of crucial skills like perseverance, time management, and the ability to avoid distractions. It’s most likely those skills, in the end, that keep kids in college.

4. A Rubric Reduces Racial Grading Bias

A simple step might help undercut the pernicious effect of grading bias, a new study found: Articulate your standards clearly before you begin grading, and refer to the standards regularly during the assessment process.

In 2020, more than 1,500 teachers were recruited and asked to grade a writing sample from a fictional second-grade student. All of the sample stories were identical—but in one set, the student mentions a family member named Dashawn, while the other set references a sibling named Connor.

Teachers were 13 percent more likely to give the Connor papers a passing grade, revealing the invisible advantages that many students unknowingly benefit from. When grading criteria are vague, implicit stereotypes can insidiously “fill in the blanks,” explains the study’s author. But when teachers have an explicit set of criteria to evaluate the writing—asking whether the student “provides a well-elaborated recount of an event,” for example—the difference in grades is nearly eliminated.

5. What Do Coal-Fired Power Plants Have to Do With Learning? Plenty

When three coal-fired plants closed in the Chicago area, student absences in nearby schools dropped by 7 percent, a change largely driven by fewer emergency room visits for asthma-related problems. The stunning finding, published in a 2020 study from Duke and Penn State, underscores the role that often-overlooked environmental factors—like air quality, neighborhood crime, and noise pollution—have in keeping our children healthy and ready to learn.

At scale, the opportunity cost is staggering: About 2.3 million children in the United States still attend a public elementary or middle school located within 10 kilometers of a coal-fired plant.

The study builds on a growing body of research that reminds us that questions of educational equity do not begin and end at the schoolhouse door. What we call an achievement gap is often an equity gap, one that “takes root in the earliest years of children’s lives,” according to a 2017 study . We won’t have equal opportunity in our schools, the researchers admonish, until we are diligent about confronting inequality in our cities, our neighborhoods—and ultimately our own backyards.

6. Students Who Generate Good Questions Are Better Learners

Some of the most popular study strategies—highlighting passages, rereading notes, and underlining key sentences—are also among the least effective. A 2020 study highlighted a powerful alternative: Get students to generate questions about their learning, and gradually press them to ask more probing questions.

In the study, students who studied a topic and then generated their own questions scored an average of 14 percentage points higher on a test than students who used passive strategies like studying their notes and rereading classroom material. Creating questions, the researchers found, not only encouraged students to think more deeply about the topic but also strengthened their ability to remember what they were studying.

There are many engaging ways to have students create highly productive questions : When creating a test, you can ask students to submit their own questions, or you can use the Jeopardy! game as a platform for student-created questions.

7. Did a 2020 Study Just End the ‘Reading Wars’?

One of the most widely used reading programs was dealt a severe blow when a panel of reading experts concluded that it “would be unlikely to lead to literacy success for all of America’s public schoolchildren.”

In the 2020 study , the experts found that the controversial program—called “Units of Study” and developed over the course of four decades by Lucy Calkins at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project—failed to explicitly and systematically teach young readers how to decode and encode written words, and was thus “in direct opposition to an enormous body of settled research.”

The study sounded the death knell for practices that de-emphasize phonics in favor of having children use multiple sources of information—like story events or illustrations—to predict the meaning of unfamiliar words, an approach often associated with “balanced literacy.” In an internal memo obtained by publisher APM, Calkins seemed to concede the point, writing that “aspects of balanced literacy need some ‘rebalancing.’”

8. A Secret to High-Performing Virtual Classrooms

In 2020, a team at Georgia State University compiled a report on virtual learning best practices. While evidence in the field is "sparse" and "inconsistent," the report noted that logistical issues like accessing materials—and not content-specific problems like failures of comprehension—were often among the most significant obstacles to online learning. It wasn’t that students didn’t understand photosynthesis in a virtual setting, in other words—it was that they didn’t find (or simply didn't access) the lesson on photosynthesis at all.

That basic insight echoed a 2019 study that highlighted the crucial need to organize virtual classrooms even more intentionally than physical ones. Remote teachers should use a single, dedicated hub for important documents like assignments; simplify communications and reminders by using one channel like email or text; and reduce visual clutter like hard-to-read fonts and unnecessary decorations throughout their virtual spaces.

Because the tools are new to everyone, regular feedback on topics like accessibility and ease of use is crucial. Teachers should post simple surveys asking questions like “Have you encountered any technical issues?” and “Can you easily locate your assignments?” to ensure that students experience a smooth-running virtual learning space.

9. Love to Learn Languages? Surprisingly, Coding May Be Right for You

Learning how to code more closely resembles learning a language such as Chinese or Spanish than learning math, a 2020 study found—upending the conventional wisdom about what makes a good programmer.

In the study, young adults with no programming experience were asked to learn Python, a popular programming language; they then took a series of tests assessing their problem-solving, math, and language skills. The researchers discovered that mathematical skill accounted for only 2 percent of a person’s ability to learn how to code, while language skills were almost nine times more predictive, accounting for 17 percent of learning ability.

That’s an important insight because all too often, programming classes require that students pass advanced math courses—a hurdle that needlessly excludes students with untapped promise, the researchers claim.

10. Researchers Cast Doubt on Reading Tasks Like ‘Finding the Main Idea’

“Content is comprehension,” declared a 2020 Fordham Institute study , sounding a note of defiance as it staked out a position in the ongoing debate over the teaching of intrinsic reading skills versus the teaching of content knowledge.

While elementary students spend an enormous amount of time working on skills like “finding the main idea” and “summarizing”—tasks born of the belief that reading is a discrete and trainable ability that transfers seamlessly across content areas—these young readers aren’t experiencing “the additional reading gains that well-intentioned educators hoped for,” the study concluded.

So what works? The researchers looked at data from more than 18,000 K–5 students, focusing on the time spent in subject areas like math, social studies, and ELA, and found that “social studies is the only subject with a clear, positive, and statistically significant effect on reading improvement.” In effect, exposing kids to rich content in civics, history, and law appeared to teach reading more effectively than our current methods of teaching reading. Perhaps defiance is no longer needed: Fordham’s conclusions are rapidly becoming conventional wisdom—and they extend beyond the limited claim of reading social studies texts. According to Natalie Wexler, the author of the well-received 2019 book The Knowledge Gap , content knowledge and reading are intertwined. “Students with more [background] knowledge have a better chance of understanding whatever text they encounter. They’re able to retrieve more information about the topic from long-term memory, leaving more space in working memory for comprehension,” she recently told Edutopia .

Schools and Health: Our Nation's Investment (1997)

Chapter: 6 challenges in school health research and evaluation, 6 challenges in school health research and evaluation, overview of research and evaluation.

One of the primary arguments for establishing comprehensive school health programs (CSHPs) has been that they will improve students' academic performance and therefore improve the employability and productivity of our future adult citizens. Another argument relates to public health impact—since one-third of the Healthy People 2000 objectives can be directly attained or significantly influenced through the schools, CSHPs are seen as a means to reduce not only morbidity and mortality but also health care expenditures. It is likely that the future of CSHPs will be determined by the degree to which they are able to demonstrate a significant impact on educational and/or health outcomes.

Evaluation of any health promotion program poses numerous challenges such as measurement validity, respondent bias, attrition, and statistical power. The situation is even more challenging for CSHPs, for several reasons. First, these programs comprise multiple, interactive components, such as classroom, family, and community interventions, each employing multiple intervention strategies. Therefore, it is often difficult to determine which intervention components and specific messages, activities, and services are responsible for observed treatment effects. Second, given the broad scope of CSHPs, it is difficult to determine what the realistic outcomes should be, and measuring these outcomes in school-age children (be it the actual behavior or precursors such as communication skills) is often problematic, especially when outcomes have to do

with such sensitive matters as drug use or sexual behavior. Finally, though some aspects of a CSHP (e.g., classroom curricula) can be replicated, many aspects of the CSHP (e.g., staffing patterns, local norms, and community resources) differ across schools, cities, states, and regions. Consequently, the results of even the most rigorous evaluations may not be generalizable to other settings.

This chapter examines these and other issues related to the evaluation of CSHPs. First, general principles of research and evaluation, as applied to school health programs, are reviewed. Then the challenges and difficulties associated with research and evaluation of comprehensive, multi-component programs are examined. Finally, the difficulties and uncertainties related to research and evaluation of even a single, relatively well-defined component of comprehensive programs—the health education component—are be considered. The committee felt that it was appropriate to focus on health education in this chapter, because of the relative maturity of research in this area. Specific aspects of health education research have been chosen that highlight challenges in evaluating school-based interventions, as well as in interpreting ambiguous, if not conflicting, results relevant to other components of the comprehensive program. Discussion of the research and evaluation of other components of CSHPs—health services, nutrition or foodservices, physical education, and so forth—is found in the general discussion of these components in earlier chapters.

Types of School Health Research

Research and evaluation of comprehensive school health programs can be divided into three categories: basic research, outcome evaluation, and process evaluation.

Basic Research

An ultimate goal of CSHPs is to influence behavior. Basic research in CSHPs involves inquiry into the fundamental determinants of behavior as well as mechanisms of behavior change. Basic research includes examination of factors thought to influence health behavior—such as peer norms, self-efficacy, legal factors, health knowledge, and parental attitudes—as well as specific behavior change strategies. Basic research often employs epidemiologic strategies, such as cross-sectional or longitudinal analyses, as well as pilot intervention studies designed to isolate specific behavior change strategies, although often on a smaller scale than full outcome trials. A primary function of basic behavioral research is to in-

form the development of interventions, whose effects can then be tested in outcome evaluation trials.

Outcome Evaluation

Outcome evaluation includes empirical examination of the impact of interventions on targeted outcomes. Possible outcomes (or dependent variables) include health knowledge, attitudes, skills, behaviors, biologic measures, morbidity, mortality, and cost-effectiveness. Interventions (or independent variables) include specific health education curricula, teaching strategies, organizational change, environmental change, or health service delivery models. This type of evaluation in its most basic form resembles the randomized clinical trial with experimental and control groups, along with the requisite null hypothesis assumptions and concern for internal and external validity. Outcome evaluation can further be divided into three stages: efficacy, effectiveness, and implementation effectiveness trials (Flay, 1986).

Efficacy . Efficacy testing involves the evaluation of an intervention under ideal, controlled implementation conditions. During this stage, for example, teachers may be paid to ensure that they implement a health curriculum, or other motivational strategies may be used to ensure fidelity. The goal of efficacy testing is to determine the potential effect of an intervention, with less concern for feasibility or replicability. In drug study parlance, during this stage of research efforts are made to ensure that the ''drug" is taken so that biologic effects, or lack thereof, can be attributed to the drug rather than to degree of compliance.

Effectiveness . In effectiveness trials, interventions are implemented under real-world circumstances with the associated variations in implementation and participant exposure. Effectiveness trials help determine if interventions can reliably be used under real-world conditions and the extent to which effects observed under efficacy conditions are reproduced in natural settings. Some programs, despite being efficacious, may not be effective if they are difficult to implement or are not accepted by staff or students. Effectiveness research is of particular concern because the results of efficacy testing and, to a lesser extent, of effectiveness trials may not always be generalizable to the real world.

Implementation Effectiveness . In implementation effectiveness trials, variations in implementation methods are manipulated experimentally and outcomes are measured (Flay, 1986). For example, the outcomes can be compared when a CSHP is implemented with or without a school

coordinator or when a health education program is implemented by peers rather than adults.

Process Evaluation

Once an intervention has demonstrated adequate evidence for efficacy and effectiveness, it can be assumed that replications of the intervention will yield effects similar to those observed in prior outcomes research trials. The validity of this assumption is enhanced when multiple effectiveness trials have been successfully conducted under varying conditions and the intervention is delivered with fidelity in a setting and with a target population similar to those used in the initial testing.

It is at this point that process evaluation becomes the desired level of assessment. The goal of process evaluation is not to determine the basic impact of an intervention but rather to determine whether a proven intervention was properly implemented, and what factors may have contributed to the intervention's success or failure at the particular site. Implementation and/or participant exposure can be used as proxies for formal outcome evaluation. Key process evaluation strategies include implementation monitoring (e.g., teacher observation), quality assurance, and assessing consumer reactions (e.g., student, teacher, and parent response to the program).

Evaluation at this level may include some elements of outcome evaluation. Desired outcomes are often stated as objectives to be achieved by the program, which can be evaluated pre- and post-intervention, and may include a comparison group or references to normative data. Random selection and assignment of participants are typically not employed, however, and the level of rigor used to collect and analyze data is often less stringent than in formal outcome evaluation. This type of evaluation is sometimes referred to as program evaluation.

Although program evaluation can include rigorous design and analyses, in many real world program evaluations the assessment is often secondary to the intervention. Such interventions often do not bother with randomized design, control groups, or complex statistics. The evaluation is adapted to the intervention, rather than the inverse. For example, pragmatic issues, more than experimental design, often determine sample size and which sites are assigned to treatment or comparison conditions. In basic research and outcome evaluation on the other hand, evaluation is the principal reason that the intervention is being conducted; pragmatic issues often yield to methodologic concerns, and evaluation procedures largely are determined prior to initiating intervention activities.

Linking Outcome and Process Evaluations

Although outcome and process evaluation are described above as being sequential, the two often are conducted concurrently by linking process data to outcome data in order to determine causal pathways. One application of linking process and outcome data is the dose–response analysis—measuring the relationship between intervention dose and level of outcomes. For example, student behavioral outcomes can be examined relative to levels of teachers' curriculum implementation in a health education study or to students' level of clinic usage in a health services study. A positive dose–response relationship is seen as evidence for construct validity—that is, observed outcomes are attributed to the intervention rather than to other influences. Numerous health education studies have established a dose–response relationship between curriculum exposure and student outcomes (Connell et al., 1985; Parcel et al., 1991; Resnicow et al., 1992; Rohrbach et al., 1993; Taggart et al., 1990). Less is known about dose–response in other components of CSHPs.

Who Conducts the Research?

The various types of school health research are conducted by a diverse group of professionals. Basic research and outcome evaluation are typically conducted by doctoral-level professionals from university and freestanding research centers, often with funding from the federal government (though such studies also are supported by private foundations or corporations). Evaluating CSHPs at the level of basic research or outcome evaluation is largely beyond the fiscal and professional capacity of most local and even state education agencies. Process evaluation, on the other hand, can be conducted by local education agencies, perhaps in partnership with local public health agencies. Many models of CSHPs include an evaluation component, and it is important to delineate what type of evaluation schools and education agencies should reasonably be expected to conduct on the local level.

Although carried out by research professionals, basic research and outcome evaluation should not be abstract academic pursuits that are an end in themselves. Greater interaction is needed between researchers and those who actually implement programs. It would be desirable to stimulate and support research and evaluation alliances among colleges of education, schools of public health, and college of medicine. Bringing together the expertise from all three sectors in school health research and evaluation centers may enhance the understanding and interaction between these sectors and produce research and evaluation methods that can address cross-sector issues more accurately. This also will lead to

developing programs that can be disseminated more easily and to reducing the number of researchers working in isolation.

Uses for Research and Evaluation

Basic research, outcome evaluation, and process evaluation are also conducted for different audiences and intentions. The first two are largely intended to build scientific knowledge and are generally published in the peer-reviewed literature. The latter generally is used to demonstrate feasibility of an intervention, as well as to document the facts that program implementation objectives were met and funds were properly spent. Such reports are typically requested by or intended for state education agencies, local education agencies, or funding sources that may have sponsored the local project. Local program evaluations of pilot programs also are used to justify expanding dissemination efforts.

All three types of evaluation can contribute to the development and dissemination of comprehensive school health programs, although it is important that they be applied in their proper sequence. Process evaluation studies are inappropriate for demonstrating intervention efficacy or measuring cost-effectiveness, just as basic research approaches may go beyond what is necessary for local program evaluation. To merit dissemination, programs should first undergo formal experimental efficacy and effectiveness testing; lower standards may result in adoption of suboptimal programs and ultimately impair the credibility of school health programs among their educational and public health constituencies (Ennett et al., 1994).

METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGES

Although traditional experimental studies using control or comparison groups are appropriate for testing individual program components and specific intervention strategies, this may not be the case for the overall CSHP, which is a complex entity and varies from site to site. In a recent discussion of methods to evaluate such complex systems as CSHPs, Shaw (1995) proposed that the use of the classic experimental design to conduct outcome evaluations may be outmoded and inadequate for several reasons. First, the randomized clinical trial, with its tightly controlled and defined independent and dependent variables, cannot measure and capture large-scale, rapidly changing systems. Traditional experimental design ignores the need for timely formative descriptive data, maintains the artificial roles of the researcher as external expert and the subject as passive recipient of a defined treatment, and fails to recognize the complex nature of multifaceted programs that vary according to community needs.

Furthermore, there may be ethical dilemmas in randomly assigning students to treatment versus control groups when children's health and well-being are at stake.

It will be difficult—and possibly not feasible—to conduct traditional randomized trials on entire comprehensive programs. However, interventions associated with individual program components should be developed and tested by using rigorous methods that involve experimental and control groups, with the requisite concern for internal and external validity. In this section, some of the methodological challenges of demonstrating program impacts are examined.

Challenges in Assessing Validity

A goal of studying CSHPs at the level of efficacy testing is to measure the extent to which programs produce the desired outcomes (internal validity)—that is, to determine whether there is a causal relationship between the independent variable (CSHP) and defined outcomes such as knowledge, health practices, or health status.

Defining the Independent Variable

The first measurement challenge is the difficulty in defining the independent variable (the CSHP) or "treatment." Knapp (1995) has described this dilemma: "The 'independent variable' is elusive. It can be many different kinds of things, even within the same intervention; far from being a fixed treatment, as assessed by many research designs, the target of study is more often a menu of possibilities."

Ironically, the most successful programs—which are, in fact, comprehensive, multifaceted, interdisciplinary and well integrated into the community—may be the most difficult to define and segregate into components readily identifiable as the independent variable. It may be impossible, for example, to separate effects of the school from those of the community (Perry et al., 1992). This poses an important assessment dilemma. While it is vital that comprehensive programs be evaluated as a whole (Lopez and Weiss, 1994), it is unlikely that any individual program could be replicated in its entirety in a different community with its varying infrastructure, needs, and values. Thus, internal validity—the extent to which the effectiveness of the entire program is being accurately measured—may be high, but external validity—the extent to which the findings can be generalized and replicated beyond a single setting—is sacrificed.

Because of limited resources, one might wish to prioritize individual program components based on their relative efficacy. However, the over-

all effect of comprehensive programs may well be more than or different from the sum of its parts. Using a factorial design to examine the effects of individual components or combinations of components would require an unwieldy number of experimental conditions and large sample size. Thus, the independent variables in a CSHP not only may be difficult to define and measure, but it is unlikely that a consensus of what should comprise the intervention can or even should be reached.

Defining the Dependent Variable

In similar ways, defining the appropriate, feasible, and measurable outcomes (dependent variables) of a CSHP is equally challenging. Is it necessary to use change in health-related behaviors, such as smoking or drug use, to measure effectiveness of health education programs, or is the acquisition of knowledge and skills sufficient? If behavior change outside the school is required to declare effectiveness, this would seem to represent an educational double standard. For example, the quality and effectiveness of mathematics education are measured by determining mathematics knowledge and skills, using some sort of school-based assessment, not by determining whether the student actually balances a checkbook or accurately fills out an income tax form as an adult. Likewise, the quality of instruction in literature or political science is measured by the acquisition of knowledge, not by whether the student writes novels, reads poetry, votes, or becomes a contributing citizen.

Similarly, should appropriate outcomes for school health services be improved health status, behaviors, and long-term health outcomes, or is simply access to and utilization of services a sufficient end point? Is a reduction in absenteeism a proxy for improved health status and a reasonable indicator of health outcomes? Dependent variables used to measure effectiveness of school-linked health services have included linking students with no prior care to health services, decreased use of the emergency room for primary care, identification of previously unidentified health problems, access to and utilization of services by students and families, perceptions and health knowledge of students and their parents, decreasing involvement in risk behaviors, and health status indicators (Glick et al., 1995; Kisker et al., 1994; Lewin-VHI and Institute of Health Policy Studies, 1995). Some of these measures simply determine whether school services provide access and utilization, whereas other measures look for a change in health status and behavior. However, if improved health status and behaviors are declared to be the expectation for school health services, does this hold the school to higher standards than those of other health care providers?

The committee points out that, although influencing health behavior

and health status are ultimate goals of CSHPs, such end points involve personal decisionmaking beyond the control of the school. Other factors—family, peers, community, and the media—exert tremendous influence on students, and schools should not bear total responsibility for students' health behavior and health status. Schools should be held accountable for conveying health knowledge, providing a health-promoting environment, and ensuring access to high-quality services; these are the reasonable outcomes for judging the merit of a CSHP. 1 Other outcomes—improved attendance, better cardiovascular fitness, less drug abuse, or fewer teen pregnancies, for example—may also be considered, but the committee believes that such measures must be interpreted with caution, since they are influenced by personal decisionmaking and factors beyond the control of the school. In particular, null or negative outcomes for these measures should not necessarily lead to declaring the CSHP a failure; rather, they may imply that other sources of influence on children and young people oppose and outweigh the influence of the CSHP.

Other Issues

In addition to the above difficulties, all of the potential biases and challenges inherent in any research also apply. Serious threats to validity in measuring effects of CSHP include:

the Hawthorne effect—positive outcomes simply due to being part of an investigation, regardless of the nature of the intervention;

self-reporting biases—responding with answers that are thought to be "correct" and socially desirable;

Type III error—incorrectly concluding that an intervention is not effective, when in fact ineffectiveness is due to the incorrect implementation of the intervention.

ensuring even and consistent distribution of the intervention;

sorting out effects of confounding and extraneous variables;

isolating effective ingredients of multifaceted programs;

control groups that are not comparable;

differential and selective attrition in longitudinal studies;

inadequate reliability and validity of measurement tools; and

vague or inadequate conceptualization of study variables.

|

| This view is consistent with earlier discussion in this chapter that for the local school, the desired level of evaluation is process evaluation. If the school is providing health curricula and health services that have been shown through basic research and outcome evaluation to produce positive health outcomes, the committee suggests that the crucial question at the school level should be whether the interventions are implemented properly. |

Another problem in drawing conclusions from reported research is "reporting bias"—the fact that only positive findings tend to be reported in the literature while studies with negative or inconclusive results are not often published. It is also important to remember that results that are statistically significant may not always have educational and public health significance.

Challenges Related to Feasibility

The kinds of large-scale research studies necessary to assess long-term outcomes of CSHPs are extremely costly and require extensive coordination. Since such programs are usually implemented for entire schools, communities, regions, or states, a majority of the children who participate are at relatively low risk for a number of outcomes of potential relevance. In addition, often only small to moderate outcome effects are sought. Hence, sample size needs are large, particularly when the unit of measurement is the school or the community rather than the individual.

Once efficacy and effectiveness have been demonstrated, the problem of developing a feasible program evaluation plan is compounded by the lack of evaluation expertise at the local or regional level and the inadequate or incompatible information systems for collecting, analyzing, and disseminating information. Local planners often need assistance in selecting and implementing evaluation strategies and in identifying means to make existing data more useful. For school health education, there are numerous guidelines and evaluation manuals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Health and Human Service's Center for Substance Abuse Prevention at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Educational Development Center, to help states develop an evaluation plan. The national evaluation plan for the Healthy Schools, Healthy Communities Program provides helpful information for the evaluation of school health services (Lewin-VHI and Institute of Health Policy Studies, 1995). This plan is facilitated by a standardized data collection system and marks the first time that health education and health services will be systematically analyzed with a management information system that records different types of health education interventions, utilization of health services, and outcomes.

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH EDUCATION RESEARCH

Health education is one of the essential components of CSHPs. As

described in earlier chapters, health instruction has taken place in schools for many years, and the field is reasonably well defined and developed compared to some of the other aspects of a CSHP. Health education research has been an active field, but considerable knowledge gaps exist and research findings are often ambiguous, unexpected, or sometimes seemingly contradictory. This section focuses on some of the challenges and unresolved questions in classroom health education and suggests issues that merit further study.

Effects of Comprehensive Health Education