- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Voltaire: A Very Short Introduction

Author webpage

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Voltaire (1694–1778), best remembered as the author of Candide , is one of the central actors of the European Enlightenment. Voltaire: A Very Short Introduction explores Voltaire’s remarkable career, his most important works, and demonstrates how his thinking is pivotal to our notion and understanding of the Enlightenment. It examines the nature of Voltaire’s literary celebrity, demonstrating the extent to which his work was reactive and practical, and therefore made sense within the broader context of the debates to which he responded. It concludes by looking not only at Voltaire’s impact in literature and philosophy, but also at his influence on French political values and modern French politics.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

Blog article

- Voltaire and the one-liner

External resource

- In the OUP print catalogue

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Candide, Voltaire : fiche de lecture

Tu passes le bac de français ? CLIQUE ICI et deviens membre de commentairecompose.fr ! Tu accèderas gratuitement à tout le contenu du site et à mes meilleures astuces en vidéo.

Publiée en 1759, Candide est une œuvre emblématique du siècle des Lumière .

Elle délivre un message puissant sur la recherche du bonheur dans un monde imparfait tout en proposant une critique sociale et philosophique du XVIIIème siècle.

Candide : analyse en vidéo

Qui est Voltaire ?

François-Marie Arouet , plus connu sous le nom de Voltaire (1694-1778), fut l’un des plus éminents écrivains et philosophes du siècle des Lumières en France.

Célèbre pour son esprit incisif, son engagement en faveur de la tolérance et son combat contre l’obscurantisme , Voltaire fut un auteur prolifique qui s’est exprimé dans de nombreux genre s : théâtre, contes et essais philosophiques, poésie, articles d’Encyclopédie…

Son esprit critique et son engagement pour la liberté ont contribué à diffuser l’esprit des Lumières dans l’ensemble de la société européenne.

Analyses d’extraits de Candide :

- Candide, chapitre 1

- Candide, chapitre 3

- Candide, chapitre 6

- Candide, chapitre 18

- Candide, chapitre 19

- Candide, chapitre 30

Comment résumer Candide de Voltaire ?

Candide vit paisiblement au château du Baron de Thunder-ten-Tronckh en Westphalie où il reçoit des leçons du philosophe Pangloss , qui prêche l’optimisme en déclarant que tout est pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles .

Cependant, après un baiser échangé avec Cunégonde , la fille du Baron, Candide est chassé du château.

Il entreprend alors un voyage initiatique à travers le monde qui va lui permettre peu à peu de s’affranchir de l’enseignement philosophique qu’il a reçu de son maître Pangloss. Enrôlé dans les troupes bulgares au chapitre III, Candide assiste ainsi à la brutalité de la guerre lors d’une « boucherie héroïque ».

Il fuit vers Lisbonne où il est confronté à un terrible tremblement de terre et à l’ intolérance religieuse . Condamné lors d’un autodafé , il parvient à échapper à ses persécuteurs et tue l’amant de Cunégonde pour s’échapper en Espagne.

Accompagné de son valet Cacambo, de Cunégonde et d’une vieille servante, il embarque pour le Paraguay .

Au chapitre XVI, la troupe de jeunes gens est capturée par les Oreillons , une tribu sauvage et féroce, et manque de justesse d’être mangée. Aux chapitres XVII et XVIII, ils arrivent au fameux Eldorado , un lieu merveilleux , caractérisé par une abondance de richesses matérielles, une organisation sociale égalitaire et une absence de fanatisme religieux. Les jeunes gens décident pourtant de poursuivre leur chemin.

Candide embarque alors pour l’Europe et fait la rencontre de Martin , un philosophe pessimiste , qui partage son point de vue sombre sur la nature humaine.

Leur voyage les mène à Bordeaux, puis à Paris, où Candide frôle la mort en raison des soins médicaux peu fiables .

Ils longent les côtes d’Angleterre sans y accoster car Candide s’indigne de voir l’ exécution d’un officier anglais .

Finalement, ils atteignent Venise et rencontrent Pococurante , un riche noble vénitien désillusionné et blasé , ainsi que six rois détronés. Ils partent ensuite pour Constantinople , où Candide retrouve Cunégonde enlaidie .

Ils s’installent tous dans une métairie , et se tournent vers une vie plus simple et équilibrée, orientée vers le travail concret. Le chapitre XXX se conclut ainsi :

« Pangloss disait quelquefois à Candide : Tous les événements sont enchaînés dans le meilleur des mondes possibles ; car enfin si vous n’aviez pas été chassé d’un beau château à grands coups de pied dans le derrière pour l’amour de mademoiselle Cunégonde, si vous n’aviez pas été mis à l’Inquisition, si vous n’aviez pas couru l’Amérique à pied, si vous n’aviez pas donné un bon coup d’épée au baron, si vous n’aviez pas perdu tous vos moutons du bon pays d’Eldorado, vous ne mangeriez pas ici des cédrats confits et des pistaches.– Cela est bien dit, répondit Candide, mais il faut cultiver notre jardin. » Candide , chapitre XXX

Clique ici pour lire le résumé de Candide chapitre par chapitre.

Qui sont les personnages principaux dans Candide ?

Personnage principal du conte, Candide est un jeune homme naïf et optimiste , ayant été élevé dans l’idée que « tout est au mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles » par son précepteur, Pangloss .

Au fil du récit, Candide est confronté à de nombreuses épreuves et découvre la dure réalité du monde. Son voyage initiatique lui permet de développer sa compréhension du mal, de la souffrance et de la nature humaine . Il incarne la quête du bonheur et de la vérité .

Le précepteur de Candide, Pangloss, est un philosophe optimiste qui enseigne que « tout est pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles « , et ce en dépit des malheurs et catastrophes auxquels il est confronté. Pangloss incarne l’ optimisme naïf et la confiance aveugle, malgré les preuves évidentes du mal et de la souffrance dans le monde.

C’est un personnage qui n’évolue pas au cours du récit, contrairement à Candide qui s’affranchit de ses préjugés.

Cunégonde, dont Candide est amoureux , est la fille du baron du château de Thunder-ten-Tronckh .

Au début du récit, c’est une jeune femme séduisante et désirable que Candide va tout faire pour retrouver, malgré les multiples épreuves et déceptions qu’il rencontre.

Lorsqu’ils se retrouvent à la fin du conte, Cunégonde n’a pas été épargnée par les souffrances de la vie. Enlevée, violée, maltraitée, elle s’est enlaidie . Elle incarne donc la confrontation avec la réalité brutale du monde .

Martin est un philosophe pessimiste que Candide rencontre lors de ses voyages en Europe.

Contrairement à Pangloss, Martin considère que le monde est fondamentalement mauvais . Pour lui, la souffrance et l’injustice sont inévitables. Il représente donc une voix discordante face à l’optimisme naïf de Pangloss.

Le baron de Thunder-ten-Tronckh

Le baron est le père de Cunégonde et le propriétaire du château où Candide vit au début de l’histoire. Il chasse Candide du château en raison de son amour pour Cunégonde.

Le baron représente l’ arrogance et la rigidité sociale de l’aristocratie de l’époque, mettant en évidence les inégalités et les injustices du système féodal.

Cacambo est le valet fidèle de Candide qui l’accompagne tout au long de ses aventures.

Il incarne la loyauté, l’ingéniosité et la fidélité envers son maître. Il représente également la voix de la raison face à l’optimisme naïf de Candide, l’aidant à prendre des décisions judicieuses au cours de leur périple (par exemple, il sauve Candide des Oreillons dans le chapitre XVI)

Quels sont les thèmes importants dans Candide ?

La critique de l’optimisme.

Candide ou l’Optimisme s’inscrit dans un débat important au XVIIIème siècle qui oppose Voltaire et le philosophe allemand Leibniz .

Leibniz considère que le monde est guidé par le principe de « raison suffisante » dans une « harmonie parfaite préétablie » par Dieu. Ainsi « tout est pour le mieux » puisque tout est organisé par une intelligence supérieure, celle de Dieu.

Pour Voltaire, cet optimisme philosophique défie la raison et l’observation.

Il décide alors d’écrire un conte philosophique avec deux personnages types, le professeur Pangloss (clairement l’ incarnation de Leibniz ) et Candide un personnage naïf, vierge de tout préjugés qui va mettre à l’épreuve les théories optimistes de son maître .

C’est ainsi que Candide va connaître la guerre (chapitre III), la superstition et l’injustice (chapitre VII), la captivité (chapitre XVI), l’ennui (chapitre XVIII), la maladie (XXIV), le scepticisme et la vanité des sciences (Chapitre XXV), et la déception de retrouver Cunégonde enlaidie.

Ce tour du monde de la tragédie humaine a vocation à déconstruire l’optimisme naïf de Candide qui adoptera à la fin du conte une a utre philosophie, plus pragmatique : « il faut cultiver notre jardin » .

Le tour du monde de Candide est l’occasion pour Voltaire de montrer que le mal est universel et qu’il est partout . Le conte explore différentes manifestations du mal :

– Le mal dans la société : « Candide » critique la société européenne du XVIIIe siècle en mettant en évidence les inégalités sociales, la corruption et les abus de pouvoir . Les guerres injustes , l’intolérance religieuse , l’exploitation des paysans et l’arrogance des élites aristocratiques dessinent une société gangrénée par le mal.

– Mais le mal est également naturel : tout au long du récit, Candide et ses compagnons sont confrontés à des désastres naturels tel le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne. L’épisode de la tribu sauvage des Oreillons montre aussi qu’à l’état de nature, les hommes ne sont pas naturellement bons.

– La souffrance de l’expérience humaine : Les personnages de « Candide » sont soumis à d’innombrables souffrances et tragédies personnelles tout au long du roman : maladies, perte d’un être cher, tromperie du conjoint, etc.

Tout en dépeignant un monde marqué par l’injustice et la souffrance, Voltaire ne se contente toutefois pas de critiquer passivement le mal. Le philosophe soulève la question du libre arbitre et de la responsabilité humaine face au mal .

La recherche du bonheur réside ainsi dans l’acceptation des réalités, dans l’action pragmatiqu e et le partage des valeurs humaines fondamentales telles que la tolérance, la compassion et la solidarité.

La quête du bonheur

Le bonheur est un thème fondamental au XVIIIème siècle. Avec Candide , Voltaire remet en cause certaines visions du bonheur en vogue au XVIIIème siècle :Il montre que le bonheur ne réside pas dans un état de nature comme le prétend Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Ainsi, le chapitre XVI sur les Oreillons souligne que le bon sauvage n’est qu’un mythe . C’est parce qu’ils sont civilisés que Candide et Cacambo ont la vie sauve.

– Ensuite, Voltaire suggère que le bonheur ne réside pas non plus dans les sociétés politiques . Il déconstruit ainsi le mythe d’ Eldorado et du nouveau monde, lieu à l’organisation politique parfaite, qui ne parvient pas à faire rester Candide.

– L’auteur montre aussi que le bonheur ne réside pas dans le voyage . En effet, le périple de Candide ne correspond qu’à une succession de fuites au cours desquelles le personnage principal apprend la déception et la mélancolie.

– Le bonheur ne réside pas non plus dans les possessions matérielles . Ainsi, Pococurante, seigneur désillusionné et blasé, possède une immense collection d’œuvres d’art et de livres, ainsi que tout ce qu’il désire, mais demeure insatisfait de tout.

– Le bonheur se trouve finalement dans une sorte de bien être minimal épicurien où il convient de cultiver son jardin.

Le voyage est un thème central dans Candide.

Il joue tout d’abord un rôle narratif puisque chaque déplacement des personnages d’un continent à l’autre donne lieu à des rencontres, des aventures et des épreuves qui mettent en lumière les incohérences et les absurdités du monde. Le voyage est également la métaphore de la quête existentielle de Candide.

Au fur et à mesure de ses aventures, Candide est confronté à des événements tragiques et à des dilemmes moraux qui le conduisent à remettre en question les idées préconçues qu’il a reçues de son précepteur, Pangloss, et à adopter une approche plus réaliste et pragmatique face aux difficultés de la vie. La voyage de Candide, qui est circulaire, peut aussi être analysé comme une métaphore de l’Encyclopédie . L’encyclopédie est en effet un ambitieux ouvrage en cours de rédaction lors de la publication de Candide et qui a pour but de faire un tour du monde des connaissances .

Candide peut être considéré comme la métaphore de l’esprit encyclopédique qui fait le tour du monde, l’expérimente pour en tirer des leçons de sagesse.

Quelles sont les caractéristiques de l’écriture de Voltaire dans Candide ?

L’écriture de Voltaire est d’une richesse inouïe dans ce conte.

L’exotisme des récits de voyage du XVIIIème siècle

Tout d’abord, Voltaire a recours à l’exotisme , qui permet aux lecteurs de s’évader et de trouver des charmes pittoresques à cette aventure.

Le passage par Eldorado est par exemple très attendu par les lecteurs de l’époque, abreuvés aux récits de voyages depuis la fin du XVIIème .

Un rythme enlevé

Ensuite, Voltaire crée une narration dynamique, enlevée où il se passe toujours quelque chose. Les péripéties sont nombreuses. Voltaire multiplie les personnages, les sépare et les rassemble à la fin.

En ce sens, Candide a beaucoup de points communs avec les comédies théâtrales , comme celles de Molière : le nom des personnages, les types caricaturaux qui rappellent des personnages de théâtre comique, la multiplication des personnages, des séparations et des retrouvailles.

Des registres variés

Voltaire utilise aussi le registre tragique pour montrer son indignation face à la guerre notamment au chapitre III.

Le style pathétique et le réalisme froid pour décrire les cadavres ensanglantés provoquent terreur et pitié.

L’ironie

Mais le trait saillant de l’écriture de Candide est sans conteste l’ironie qui dénonce les injustices et suscite la réflexion du lecteur tout en le divertissant avec un récit humoristique et plein d’esprit. Par exemple, lorsque Pangloss affirme que « tout est au mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles » malgré les terribles épreuves que les personnages endurent, Voltaire utilise l’ ironie pour montrer le décalage entre la vision optimiste de Pangloss et la réalité de la souffrance vécue par les personnages. Ou au chapitre III, lorsque Voltaire qualifie la guerre de « boucherie héroïque », il contredit un terme épique (« héroïque ») en le juxtaposant à un terme décrivant la cruelle réalité (« boucherie »).

Tu étudies Candide ? Tu seras aussi intéressé(e) par :

♦ Quiz sur Candide ♦ Zadig : analyse [Fiche de lecture] ♦ L’ingénu : analyse [fiche de lecture] ♦ Article « guerre », Voltaire (commentaire) ♦ Traité sur la Tolérance, « Prière à dieu » : analyse ♦ De l’horrible danger de la lecture : analyse ♦ Le conte philosophique [vidéo] ♦ Article « Torture », Voltaire : analyse ♦ Micromégas, chapitre 2 (commentaire) ♦ Le Mondain, Voltaire : analyse ♦ Femmes, soyez soumises à vos maris : analyse

Les 3 vidéos préférées des élèves :

- La technique INCONTOURNABLE pour faire décoller tes notes en commentaire [vidéo]

- Quel sujet choisir au bac de français ? [vidéo]

- Comment trouver un plan de dissertation ? [vidéo]

Tu entres en Première ?

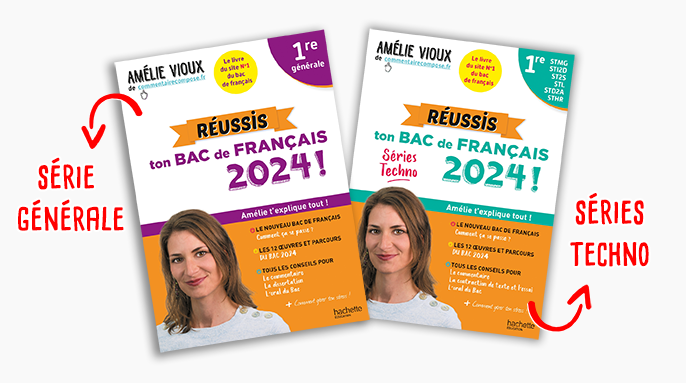

Commande ton livre 2024 en cliquant ici ⇓.

Qui suis-je ?

Amélie Vioux

Je suis professeur particulier spécialisée dans la préparation du bac de français (2nde et 1re).

Sur mon site, tu trouveras des analyses, cours et conseils simples, directs, et facilement applicables pour augmenter tes notes en 2-3 semaines.

Je crée des formations en ligne sur commentairecompose.fr depuis 12 ans.

Tu peux également retrouver mes conseils dans mon livre Réussis ton bac de français 2024 aux éditions Hachette.

J'ai également publié une version de ce livre pour les séries technologiques ici.

Laisse un commentaire ! X

Merci de laisser un commentaire ! Pour des raisons pédagogiques et pour m'aider à mieux comprendre ton message, il est important de soigner la rédaction de ton commentaire. Vérifie notamment l'orthographe, la syntaxe, les accents, la ponctuation, les majuscules ! Les commentaires qui ne sont pas soignés ne sont pas publiés.

Site internet

English 287: Great Books

There is also a much briefer study guide to this work. It is designed to highlight certain central questions that moderately experienced reader would be inclined to frame and pursue in the course of reading the tale. The guide you are reading now, though, is designed for readers who want to explore things a bit more deeply.

Here are some things to pay attention to as you review Candide . (Incidentally, don't overlook the notes that are provided beginning on p. 91 of our text [Dover Thrift Edition]. These are often essential for clarifying points that readers today would have no way of knowing on their own.)

For an introduction to Voltaire, check out one of the following:

- Voltaire: Author and Philosopher at LucidCafé . (This is more compact.)

- The biographical sketch at Malaspina Great Books . (This is more comprehensive.)

Another resource: there's also the SparkNotes Study Guide to Candide .

It would be useful to have a look now at the opening item in that study guide, on the social and cultural context within which Candide was created.

The title page

The title page is unfortunately absent in our edition. But you can take a look at what it looked like in the original edition of 1759 here . It says: "Candide or Optimism. Translated from the German of Dr. Ralph." Two facts bear noting:

(1) The title is an alternative doublet: it is named after the story's main character and, equally, by what is its (supposedly) real subject, "optimism," which in that day referred to what came to be called more specifically "philosophical optimism." This doctrine stems from the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who in 1710 published a treatise called Essais de Théodicée . It found acceptance in certain circles all over Europe, for example in English, where it became the subject of Alexander Pope's famous poem Essay on Man (1732-44).

Leibniz argued that the world we are in, despite all the suffering and criminality that attaches to it, is "the best of all possible worlds." This proposition is the central thesis of a larger argument -- from certain premises (that Voltaire regarded as false) and giving rise to certain further implications that Voltaire found politically and morally objectionable. Voltaire uses this phrase as a convenient shorthand for the entire argument and the outlook on natural and moral evil that it supports. You might find it interesting, eventually, to check out an abstract of the central argument of the Theodicy (as Leibnitz' treatise has come to be referred to, in abbreviated form): a shorter one or a somewhat more extensive one .

E Although philosophical optimism was also denounced by orthodox Christian thinkers -- who regarded it as a heresy, on the grounds that it implicitly denied Original Sin (see the end of Chapter 5) -- you should be thinking about how the particular lines along which Voltaire ridicules philosophical optimism in Candide led the clergy and the pious to recognize it as corrosive to traditional Christianity as well.

In fact, it makes sense regard the book's overt holding out of "[philosophical] optimism" as its target as a fairly transparent disguise for an attack on the Christian key axioms of original sin and divine providence & intervention as an explanation for natural events and human history. Certainly it was regarded as such by the religious authorities.

(2) Hence it is easy to understand why Voltaire never in his life publicly acknowledged that this little story (destined to become his most famous work) was his. Instead, the book came to the public as having been written by some learned German no one had ever heard of, and translated by who knows whom, but probably some hack hired by the French publisher (who also was nowhere specified).

Of course Voltaire's close friends were in the know, and it wasn't long before it was an open secret in intellectual circles in Europe that Candide was the child of the famous Voltaire. But Voltaire himself always modestly disavowed the work in public. In fact, behind the scenes he went to some lengths to further obscure its authorship. [When you've finished reading the story, you might find it fun to return here and check out the letter he wrote (also under a pseudonym) to the editors of the Journal encyclopédique shortly after the first edition appeared. (Note the date with which he endowed this letter from "Herr Demad.")]

To appreciate Voltaire's caution, it is necessary to have some knowledge of the methods and powers of the Inquisition .

The story begins in Germany, which Voltaire treats as a backwater of barbaric aristocrats with ridiculous pretensions to culture. Though the

How does Voltaire design the opening chapter to be recognized as a parody of the Biblical story of the Fall? (In case we missed this on first reading, the opening lines of Chapter 2 remind us to rethink the opening chapter in these terms.)

What elements parallel the Biblical story of Paradise and the Fall of Adam of Eve from it? It would be a good idea to briefly review the details of Genesis 2:4-3:24 .

What, though, are the differences that make for humor here?

Why would Voltaire be doing this?

Chapters 2 & 3

What attitude towards princes and established religions does Voltaire invite in his treatment of the war between the Abares and the Bulgarians?

Amsterdam / Lisbon (Chapters 3 - 9)

What reaction does Candide get to his plea for alms from several serious-minded citizens of Amsterdam?

What do you figure Voltaire might be getting at here?

What are we to make of the behavior of the orator upon charity Candide encounters in Amsterdam?

James the Anabaptist

What are we supposed to notice about the Anabaptist James (who appears in Chapters 3-5)? [If you are reading a different translation, you may find this character bearing the name "Jacques." One is the English, the other the French version of Hebrew name Jacob .]

What are his key actions in the several episodes in which we see him? How does he contrast with the Batavian sailor? with Pangloss? (later: with Martin?) What do you think is Voltaire's point in including him in the story?

When Candide meets up with his old tutor Pangloss, the latter is in a pitiable condition. (Footnote 4 is of help here in catching on to the humor.)

How does he explain the cause of his woes in the light of his principles of philosophical optimism? (What does this have to do with what his name connotes? [See Footnote 1.]) What are we to think of his explanation?

The Lisbon Earthquake. On Sunday, the first of November, 1755, around 11 o'clock in the morning Lisbon (the capital of Portugal) was struck by a horrendous earthquake. Buildings were leveled all over the city. Death was massive, particularly because much of the population was at the moment attending church, and was buried in the rubble of their collapse. News of the disaster spread rapidly all over Europe.

What trauma can you imagine this event posed for both orthodox Christian theology and philosophical optimism? (What features are in common between the two outlooks, that you infer that Voltaire is hostile to?) Have a look at a letter Voltaire wrote on hearing of the Lisbon earthquake .

- In Chapter 5, Pangloss gets into a discussion of theological issues with a "a familiar of [informant for] the Inquisition."

It's worth having a look at a brief description of this practice .

What assumptions about the causes of the earthquake can we infer must have motivated the recommendation of the faculty of the University of Coimbra?

What does Voltaire think of the mentality of the faculty? Can you put your finger on where exactly this opinion is most directly indicated?

How does Candide come to be reunited with Cunegonde?

What are the chief episodes in her story of her experiences since the "Fall"? What points is Voltaire making about military honor and religious authorities? What stress is this story designed to put upon the assumptions of philosophical optimism? How are these implications emphasized by the sorts of happenings Voltaire has invented as the facts of the Old Woman who has become Cunegonde's valet companion?

Why does Candide have to skidaddle from Lisbon?

What kind of advice does he get from the Old Woman? E How does her use of Reason differ from that of Pangloss, who is absent?

Spain (Avecenna, Cádiz) / Atlantic voyage to Argentina (Chapters 10 - 13)

How does Cunegonde lose her jewels?

What do you think Voltaire's point here is?

What qualities of mind does the Old Woman exhibit in this emergency?

What opportunity does Candide seize when the party arrives at Cádiz?

What kind of reasoning do the travelers engage in during the voyage from Cádiz to Argentina and Paraguay (Chapter 10)?

What are the main themes of the history of the Old Woman (Chapters 11 and 12)?

What does this catalogue of disasters have to do with the overall theme of Candide ? What attitude does the Old Woman adopt towards what has happened to her? What counsel does she give her companions on the basis of her experience? What does Candide (Chapter 13) think the old woman's history means for the theories of Pangloss?

Southern South America (Chapters 13 - 16)

Buenos Aires

What kind of fellow is the Governor of Buenos Aires?

What is Voltaire's point in giving him the name that he does?

What is the Old Woman's advice to Cunegonde?

What kind of a fellow is Cacambo? (As you continue to get acquainted with him, try to find words to formulate the traits that seem to stand out with him.)

How is he similar to the Old Woman? How is he different? What advice does he give his master Candide?

The "Jesuit kingdom" in Paraguay

What are the outstanding features of the "Jesuit kingdom" Candide and Cacambo visit in Paraguay (Chapters 14-15)?

Why is Voltaire so hostile to this community? (If you have seen the film The Mission , you will be struck by the divergence of evaluations!) Whom does Candide meet there, to his great surprise? Why does the encounter end as it does? What advice does Cacambo give his master? (How does his presence of mind here contrast with that of "the young philosopher"?)

An unknown country without a beaten path | a beautiful meadow

In the third paragraph of Chapter 16 we read of Candide that "[w]hile he was thus lamenting his fate, he went on eating." What is Voltaire nudging us to notice here?

- Does this remind you of a point of view we've heard expressed earlier in the story?

- Does it come up elsewhere later on as well?

What mistake does Candide make in rescuing the girls from the monkeys that are chasing them?

What do you think might be Voltaire's the point in devising this episode?

The country of the Oreillons

How is it that the pair doesn't end up on a spit, and being eaten by the Oreillons (the "Big-Ears")?

What's the fun Voltaire is having with the idea of "natural reason" -- the quality of intellect common (because "native," in-born) to the species?

El Dorado (Chapters 17 - 18)

How do the despairing pair get there?

What mistakes of interpretation do they make during their first encounters with the natives?

in the village schoolyard in the first house in the village (a hostel) What assumptions are these mistakes meant to throw into relief? Why does Voltaire want the reader to reflect on these?

What is Candide's comment on these initial discoveries (i.e., at the end of Chapter 17)?

What are the important points of the history of El Dorado that are conveyed by the old sage (retired from Court, and now living in the village C & C have stumbled into)?

- "Contentment" and "containment" are etymological cousins. (Check this out in a decent-sized desk dictionary.)

- What do you detect as the fundamental assumptions behind such a decision?

- How might we connect these assumptions with the economic and domestic political facts of the kingdom the visitors find so striking (up to now and later on during their visit)?

What is striking about the religion of El Dorado , as explained by the old wise man? (Note how certain key facts are pointed up by having the old man be surprised by Candide's questions.)

There are at least 5 points that you'd want to take stock of. What key features of prevailing European religion (i.e., Catholic and Protestant Christianity) get highlighted here? How are these connected with differences over the interpretation of divine providence in respect of how God wills that sinners be reconciled to Him (i.e., how "justification" is accomplished)? the effects of Original Sin on human nature (i.e., on the in-born character of all individuals)? how God decides to act personally within human history (i.e., miracles, divine interventions) how God chooses to make his will known to human beings (i.e., what constitutes ultimate authority for discovering God's will)

What is Voltaire's getting at in his overall portrait of religion in El Dorado?

- Here you may want to consult what WH has to say on the subject of deism [p. 404-405].

- Or check out one or more of the pages referenced in our glossary page on deism .

Both philosophical optimism and Voltaire's renunciation of theodicy could be regarded as forms of deism, under these definitions. How so? What, though, are their essential points of difference?

What does Candide's reflection on this part of his conversation with the retired elder have to say about philosophical optimism?

- How might the accusation of "provinciality" apply not just to Pangloss but to Leibniz?

What is striking about the political order that holds in El Dorado , as the Candide discovers in his visit to the capital?

What is striking about the reception Candide and Cacambo receive from the King of El Dorado? What is this meant to get us to question concerning European monarchs? Why are the latter the way they are? What "necessities" drive them to it? What would be necessary for them to cease thinking of these as necessary?

What underlying differences do these differences evidently stem from? (Voltaire is here prompting the reader to do some reflecting. Take up the challenge.)

Note that Voltaire does not seem to suppose that natural reason would lead men to form a democracy. Why do you think that is?

At the same time, how does his conception of rational monarchy differ from what prevails in Europe, where one is constantly confronted with all sorts of policies justified in the name of "reasons of state."

Why does Candide resolve to leave El Dorado?

- There are two factors, one more profound for assessing the social facts that are taken for granted as natural in Europe. Can you locate each?

- Why can't Candide be content to remain in El Dorado?

[general issues to be thinking through concerning the El Dorado episode]

If Voltaire thinks that reason is a property of the human race as a species, how do you think he would account for the fact that what passes for "reasonable" and "required by reason" differs so strikingly in Europe from what it is in El Dorado?

- How is this clear?

- Why do you think Voltaire rejects this key teaching of Christianity? (That is: with what other beliefs that you infer he holds is the belief in original sin inconsistent?)

But if Voltaire is going to reject this as an explanation for why reason does not seem to be prevailing in Europe, what explanation do you think he will be inclined to favor?

What is the focus of intellectual life in El Dorado?

- How does Voltaire's estimation of the value of astronomy and other sciences differ from that of Jonathan Swift? Why do you think that is?

What essential features of European civilization are absent from El Dorado?

- What does this tell us about El Dorado and Europe? (Try to penetrate to the assumptions in virtue of which each set of institutions or the lack of them seems "natural" and "necessary" or "only sensible" to the people of the respective societies.)

The visit to El Dorado sits approximately in the middle of Voltaire's tale. Could this be telling us something?

Northern South America / Atlantic voyage back to Europe (Chapters 19 - 21)

From El Dorado to Dutch Surinam

What point is Voltaire making in the encounter Cacambo and Candide have with the negro they find on the way in to Dutch Surinam?

- What theological issues get raised in the course of this meeting?

- How does what the negro says here

- On reflection, what do you notice about Candide's reaction if you ask what James the Anabaptist would have done, in Candide's shoes?

Dutch Surinam / departure from it

What kind of a person is Mynheer Vandurdendur? ("Mynheer," by the way, is a term of address, meaning "my lord" or "mister").

(We've encountered him twice, right: he's the owner of the Negro C & C met on the way into town, and he's the owner of the ship )

How does Candide come to take on the company of Martin?

How does Martin define his own philosophical perspective?

What exactly does he mean by describing himself as a "Manichean"? It would be worth memorizing his definition, so that you can bring it to mind when you see Martin interpreting things that he and Candide witness from now until the end of the story.

You might also want to have a look at a comprehensive discussion of Manicheism. Try one of these (say, a shorter and a longer one):

- definition by Austin Cline

- more extensive discussion from Britannica.com

- brief discussion at nationmaster.com

- article in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- How do Pangloss and Martin (as "philosophers") contrast with Cacambo and the Old Woman, in the use they make of their faculty of Reason?

- What assumptions to Pangloss and Martin nevertheless seem to share? As you read further in the story, keep thinking about this question.

- How does Martin's outlook evidently differ from that of the inhabitants of El Dorado? (Stay open to the possibility that there might be more than one way.) As you read further in the story, keep thinking about this question.

- What accounts for the difference between the interpretations that Candide and Martin make?

- Check out (in increasing order of informativeness) this or this or this or this .

- What do you think Voltaire's opinion would be of the Socinians?

[a key concept in the story]

This would be a good time to stop to consider the concept (or concepts) of prudence, and to start collecting and organizing our thoughts about its role in Candide .

- definition at Hyperdictionary or ( same ) at die.net or ( same ) at selfknowledge.com

- definition at WordReference.com

- entry at Thesaurus.com indicating terms with related but distinct meanings

- also interesting: definition of the prudent man rule at investorwords.com

The etymology of the term "prudence" involves an interesting relationship with the term "providence." How are these related, but importantly different, in today's usage? Why would a successful business man need to be competent in the virtues of prudence?

What behaviors indicate that Candide and Cunegonde are somewhat lacking in prudence?

What in particular about their backgrounds may help account for this?

In what respects is James the Anabaptist an example of a prudence?

In what respects is he not?

In what respects are Pangloss and Martin (as Candide's philosophical sidekicks) not concerned with prudence?

How are Cacambo and the Old Woman, as valets (and hence, in the narrative, sidekicks) to Candide and Cunegonde, outstanding in prudence?

How does Mynheer Vandurdendur acquaint us with a different dimension or (alternatively) a different sort of "prudence" from the one we associate with Cacambo and the Old Woman? How about the Batavian sailor we meet just before and during the Lisbon earthquake (in Chapter 5). Does he qualify as "prudent"? Is prudence the same thing as "competent selfishness"? Or are there restraints on the kind of selfishness that is consistent with "true prudence"? (What could be the force of the qualifier "true" in such a phrase, if we're not going to use it as a weasel-word to obscure the fact that we're just being arbitrary?)

Summing up: what do you think Voltaire thinks about the virtue of prudence?

Are there virtues that are more important than prudence, in Voltaire's view? If so, what might these be, and where (how) do you see the story indicating this?

Does Voltaire suggest that there is an important distinction to be made between a "broader" and a "narrower" understanding of "prudence"?

If so, what would this difference consist in? Can you formulate it? What, in your view, does the story provide that prompts us to frame such a distinction?

You'll want to return to this set of questions after you've finished the novella. What in particular does the final chapter have to "say" on this subject?

Drawing near to the coast of France

Chapter 21 is worth at least a cursory look.

- What are Martin's views concerning France and Paris? How do they compare with Candide's? (Notice how certain themes here re-surface in the concluding chapter of the story.)

Consider Candide's speculative questions in natural and moral philosophy, and Martin's replies to them. What do we learn about each character's inclinations from the questions and answers concerning

- whether the earth might originally have been a sea

- the purpose of the creation of the world

- the surprisingness of the love of the Oreillon women for the monkeys

- whether men have always been evil

- free will [? - this one gets truncated by their arrival at Bordeaux: here's a device we see variations upon throughout. What do you think Candide was getting ready to ask about free will? Why do you think Voltaire picked this topic to engineer the "practical interruption" upon on this occasion?]

France: Bordeaux, Paris (Chapter 22)

Candide and Martin encounter a scholar at the dinner hosted by the Marchiness of Parolignac. What is Voltaire up to in designing this conversation?

What is the hoax played by the Abbé? How do the pair escape?

England: Portsmouth (Chapter 23)

How does Martin's view of England compare to his view of France?

- What is the point of the episode in which Candide and Martin witness the execution of Admiral Byng (Chapter 23)?

Why is Candide inconsolably depressed upon their arrival in Venice? (Would one expect consolation out of Martin?!?)

What do we learn from the stories (Chapter 24) of

- Paquette (on the life of a prostitute) and

- Friar Giroflée (on religious faith)?

The visit to Senator Pococurante (Chapter 25) is an important episode.

Poco = Italian: "little" | curante = Italian: "caring"

How is his name fitting?

- How does his life stand with respect to the subject of "the cares of" life or "cares in" life?

- with respect to "caring for" life?

Recall Pococurante later on when you encounter the Old Turk. How do they exhibit different sorts of "indifference," with radically different sorts of implications for happiness?

How is one wise, the other foolish?

How does the theme of indifference arise in the picture the Dervish conveys through his little capsule parable of "his highness" (the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire) and the mice on board the ship?

What do Candide and Martin learn at the dinner with the 6 strangers at the public inn in Venice (Chapter 26)?

Who turns up, in what circumstances? What is familiar, in the tale we've become acquainted with, about the kind of story behind this surprise reappearance?

What is Martin's view of the sufferings of the 6? (Cf. Chapter 27, p. 78.) Who has the most convincing case - Martin or Candide?

Voyage to Constantinople (Chapters 27 - 29)

How does everyone in the little society come to be all gathered together at the end?

Cacambo? (Ch. 26-27) Pangloss? (Ch. 27-28) the Baron? (Ch. 27-28) Cunegonde & the Old Woman? (Ch. 29) Paquette and the Friar? (Ch. 30, p. 85)

What are the themes of the Baron's story?

What are the themes of Pangloss' story? What are we to think of the explanation he gives of his refusal to recant?

What surprise is in store for Candide with Cunegonde?

What is the Baron's response to Candide's response to Cunegonde's demand, and Candide's response to the Baron? [How does this ring a bell with the behavior of the Baron's aunt, in the rumor back in Chapter 1 (end of ¶1)?] What do Candide and his advisors finally decide to do with the Baron? This proves satisfying to all. How so? What larger issues does Voltaire seem to be getting at here?

Candide's farm outside of Constantinople (Chapter 30)

The great reversal occurs in the highly compact, and radiantly significant concluding chapter.

I. The little farm's miserable beginning (pp. 84-5)?

What question does the Old Woman pose that stumps them all?

[In the light of how things eventually turn out, what is the diagnosis of the root of the problem?]

What is the effect on their philosophical reflections of the arrival of Paquette and Friar Giroflée?

II. The visit to the Dervish.

How does the Dervish's initial reply undercut the assumption of Pangloss's opening question?

How does the sequel explain the rationale of the rejection of that apparently eminently sensible assumption?

Spell out the allegorical significance of the mini-parable contained in the one-sentence rhetorical question with which the Dervish replies to Candide's follow-up.

What is the significance of the Sultan's attitude towards the mice in the hold of the ship? (What is the Sultan presumably concerned about?)

How is this a radical rejection of a fundamental postulate of the Judeo-Christian picture of the meaning of history? (Where did we find that picture articulated?)

Now turn the perspective around: what do we notice if we ask what the attitude is of the mice towards the Sultan? (What are they presumably concerned about? Is this appropriate - sensical - under the circumstances?)

What is the implicit advice in this parable for mankind?

What would Luther think of this? Calvin? the participants in the Council of Trent? Pope Urban VIII? Swift? (even Pelagius?)

How does Pangloss' reply indicate that he hasn't heard what the Dervish has been saying?

How does the Dervish's answer to Pangloss' question speak to what is (wrong with) Pangloss? (Remember what his name means: pan = "all," gloss = "tongue," and derivatively "word.") [Here we have to do with a brilliant translation (by the 18th-century English novelist Tobias Smollet). Actually, the original French reads not "Hold your tongue" but simply "Shut up" (" Tais-toi "). Indirectly, the same irony is at work -- but far more indirectly than in Smollet's translation.]

What is "Pangloss" about Pangloss' final protest?

How does the Dervish's final gesture, in response to Pangloss' exasperation, execute his advice from his own side?

III. The news from Constantinople:

How is this a translation (application) to the secular plane of precisely the categories at stake in the conversation with the Dervish, on a cosmic plane?

What is "Pangloss" about Pangloss' response? How has he still not heard the Dervish's lesson? (You should notice some similarity here between the sources of comedy with Pangloss and part of the fun Molière has with Madame Pernelle in the opening scene of Tartuffe .)

IV. The visit with the Old Turk and his household:

How is the Old Turk implicitly acting, with respect to the political powers that be, in accordance with the Dervish's advice to the little group of inquirers?

What is the secret of the happiness of their household?

Do you see any connections with the conditions of "contentment" (in the "containment" of one's desires) that we were led to consider in connection with the El Dorado episode?

How does what the Old Turk say clarify the predicament of Pococurante?

V. The "new order" at the little farm:

Can you see how what the group accomplishes is a kind of "mutualist commune"?

What is the attitude here towards the idea of "private property"?

Is this necessarily a "drop-out" attitude towards the world? Or could one's "garden" include (say) a much larger social unit?

Keep in mind that Voltaire was very active in the campaign for political justice and against religious fanaticism in France.

The irrepressible Pangloss

How does the philosopher's last remark remind you of his reply to Candide's question about whether the Devil is the origin of syphilis (back in Chapter 4)?

General questions in light of the concluding chapter

Can you see how this ending amounts to an endorsement of a humble version of the Baconian project ? Can you see how one might describe Voltaire's position as a kind of secular and non-ascetic Pelagianism ? What would it mean to qualify the term "Pelagian" with the term "secular"? What changes would be indicated by adding the term "non-ascetic"?

How does Voltaire imply that the attempt to interpret natural and historical events in theological terms is a waste of time?

- Where do we see "providential explanation" of phenomena of nature? Where do we get hints about how Voltaire evaluates this form of explanation?

- Where do we see "providential explanation" of facts (imagined, since this is after all a work of fiction) of human history? Where do we get hints about Voltaire's views on the usefulness of this approach to understanding what happens in human affairs?

- What does Voltaire seem to regard as a sufficient guide to human conduct? What do people need to consult in order to know how to behave, in general terms? How does Voltaire indicate this?

How does the final chapter develop further our thinking on the topic of prudence ?

Some other short works by Voltaire, bearing on themes important in Candide

In 1734 -- twenty-five years before Candide -- Voltaire published Lettres philosophiques [or Philosophical Letters ], in which he offered to the French his reflections on British institutions and intellectual culture. Two of these are especially pertinent here, revealing as they do Voltaire's admiration for two towering figures of the 17th-Century scientific revolution, the philosopher of science Francis Bacon (1561-1626) and the mathematician-physicist Isaac Newton (1642-1727). Both laid the foundations for a movement away from revealed religion as a foundation of natural science. And Bacon pointed the way towards a focus on improvement, over generations, of the conditions of earthly existence. Francis Bacon [In 1620, Bacon published his Novum Organum ( New Method ). In it he argued that progress in natural science would be necessary for progress in controlling nature for the improvement of the human condition, and that such progress in knowledge of the hidden laws of the operation of nature would require a new method of inquiry. Ancient authority (whether secular, like the writings of Aristotle, or religious, like the traditions of the pronouncements of the Church, or the interpretation of Holy Scripture) would have to be set aside in favor of careful reasoning on the basis of systematic observation of natural phenomena through the senses. This visionary programme -- which we can call for short the Baconian project -- is a major step in the process of secularization that has marked Western society since the 16th Century. Extended from natural philosophy to moral philosophy -- in today's terms, from the natural sciences to the social sciences and to ethics and political philosophy -- it pointed towards education and legislation, rather than divine grace and purifying self-castigation, as the techniques by which the evils of social existence could be effectively addressed, and to utilitarian or "universal rationalist" ethics, rather than scriptural citation and interpretation, as the arbiter of rational social policy. For these reasons, Bacon's view of where society and individuals should invest human effort and other resources remains controversial today, especially for persons of fundamentalist outlook, whether Hindu, Muslim, Jewish, or Christian.]

- Isaac Newton

[In 1787, the 24-year-old Newton published his Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica ( The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy ), in which he generalized Galileo's studies of terrestrial acceleration into his famous 3 laws of motion, and used these, together with the law of gravity, to explain Kepler's revised version of the Copernican astronomical hypothesis, which accurately explained in turn the observed motions of the heavenly bodies. From ancient times, the Ptolemaic picture of the structure of the cosmos had been integrated with Aristotle's physics. With Newton's book, the credibility of Aristotelian-Ptolemaic system collapsed. But because in the late middle ages the traditional Christian picture of history had been integrated with the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic synthesis, this picture of man's relation to God (based on centuries of interpretation of Scripture) came under serious strain as well.]

Fifteen years after the initial publication of Candide , Voltaire was still vigorously at work flogging philosophical optimism. When you've finished reading the tale, you might want to have a look at his article "All is well" in the Philosophical Dictionary , initially published (also anonymously) in 1764, and continuously supplemented in later editions.

Here are two additional articles from the Philosophical Dictionary, which (as you can see) was not confined to the essay form: