An Essay on Criticism Summary & Analysis by Alexander Pope

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Criticism" seeks to lay down rules of good taste in poetry criticism, and in poetry itself. Structured as an essay in rhyming verse, it offers advice to the aspiring critic while satirizing amateurish criticism and poetry. The famous passage beginning "A little learning is a dangerous thing" advises would-be critics to learn their field in depth, warning that the arts demand much longer and more arduous study than beginners expect. The passage can also be read as a warning against shallow learning in general. Published in 1711, when Alexander Pope was just 23, the "Essay" brought its author fame and notoriety while he was still a young poet himself.

- Read the full text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

The Full Text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

1 A little learning is a dangerous thing;

2 Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

3 There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

4 And drinking largely sobers us again.

5 Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

6 In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts,

7 While from the bounded level of our mind,

8 Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

9 But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise

10 New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

11 So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try,

12 Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky;

13 The eternal snows appear already past,

14 And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

15 But those attained, we tremble to survey

16 The growing labours of the lengthened way,

17 The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes,

18 Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Summary

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” themes.

Shallow Learning vs. Deep Understanding

- See where this theme is active in the poem.

Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts, In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts, While from the bounded level of our mind, Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

Lines 11-14

So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try, Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky; The eternal snows appear already past, And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

Lines 15-18

But those attained, we tremble to survey The growing labours of the lengthened way, The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes, Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Symbols

The Mountains/Alps

- See where this symbol appears in the poem.

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- See where this poetic device appears in the poem.

Extended Metaphor

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” vocabulary.

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- A little learning

- Pierian spring

- Bounded level

- Short views

- The lengthened way

- See where this vocabulary word appears in the poem.

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

Rhyme scheme, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” speaker, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” setting, literary and historical context of “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing”, more “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” resources, external resources.

The Poem Aloud — Listen to an audiobook of Pope's "Essay on Criticism" (the "A little learning" passage starts at 12:57).

The Poet's Life — Read a biography of Alexander Pope at the Poetry Foundation.

"Alexander Pope: Rediscovering a Genius" — Watch a BBC documentary on Alexander Pope.

More on Pope's Life — A summary of Pope's life and work at Poets.org.

Pope at the British Library — More resources and articles on the poet.

LitCharts on Other Poems by Alexander Pope

Ode on Solitude

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Nature, Wit, and Invention: Contextualizing An Essay on Criticism

2017, Journal of Narrative and Language Studies

This article contextualizes the eighteenth-century English poet Alexander Pope's An Essay on Criticism (1711) and his other literary essays in order to elicit Pope's contributions to the neoclassical norm. Exploring the aesthetic interchanges between Pope and his predecessors and contemporaries, I endeavor to show how Pope's poetry and prose have tackled the difficult task of unifying antithetical categories of invention and judgment into the Johnsonian " general nature. "

Related Papers

Kocaeli University

Sidre Loğoğlu

Eger Journal of English Studies

Zoltan Cora

The AnaChronisT

János Barcsák

This paper discusses Pope’s Essay on Criticism in terms of Derek Attridge’s theory of creativity. It argues that Pope’s text is fundamentally based on the same commitment to the other that Attridge describes as constitutive of the singularity of literature and hence the 300-year-old Essay is a vital text which communicates itself to the present in significant ways. The success of poetry for Pope depends primarily on an appropriate relation to nature and the first chapter of this paper argues that the way Pope describes this relation is very similar to Attridge’s description of the relation to the other. The three subsequent chapters discuss how Pope’s concept of “expression” continues this theme and describes the pitfalls as well as the success of relating to nature as the other. The last two sections discuss the Essay’s treatment of the rules. It is shown that the way the rules are presented in the Essay reflects Pope’s fundamental ethical commitment no less than his concepts of na...

Comparative Literature: East & West

Zhuyu Jiang

Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature JCSLL

This paper aims to compare the poetic styles and views on human nature of three literary giants in English literature, namely, Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift and Samuel Johnson. As the three men of letters almost lived in the same age and they were all fond of writing on human nature, it will be very interesting to compare their respective styles and views on this issue.

Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies

Philip Smallwood

Nicolle Jordan

Paul Trolander

Susana Funck

Doğaç Kutlu

RELATED PAPERS

Ksenija Ciric

Basrah Journal of Agricultural Sciences

Hussein Faraj

Marcos Morgado

Seed Science and Technology

Chiara Lanzanova

Violence Against Women

wahiba abu-ras

Journal of Chinese Political Science

Pippa Morgan

Kumawula: Jurnal Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat

Ari Dwi Astono

Sveta Cecilija : časopis za sakralnu glazbu

Darko Kristović

Research Journal of Medicinal Plants

Habib GANFON

Food and Nutrition Bulletin

Maria Elena Díaz

Revista Uniabeu

Carlos Alano Soares de Almeida

Xinheng Wang

Bali Medika Jurnal

Journal of Biological Sciences

Abdul Ghaffar

Dr. Abdul Qayyum Rao

Papers Revista De Sociologia

Jordi Pascual

Laura Mononen

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

Tiffany Johnson

Jurnal Pendidikan Geografi

muhammad zainuddin Lubis

Physics Today

Michael Marder

BUTSURI-TANSA(Geophysical Exploration)

Journal of Biological Chemistry

Jean-louis Nahon

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism

Romanian Statistical Review Supplement

Liviu Tudor

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Literary Criticism of Alexander Pope

Literary Criticism of Alexander Pope

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on December 6, 2017 • ( 4 )

An Essay on Criticism , published anonymously by Alexander Pope (1688–1744) in 1711, is perhaps the clearest statement of neoclassical principles in any language. In its broad outlines, it expresses a worldview which synthesizes elements of a Roman Catholic outlook with classical aesthetic principles and with deism. That Pope was born a Roman Catholic affected not only his verse and critical principles but also his life. In the year of his birth occurred the so-called “Glorious Revolution”: England’s Catholic monarch James II was displaced by the Protestant King William III of Orange, and the prevailing anti-Catholic laws constrained many areas of Pope’s life; he could not obtain a university education, hold public or political office, or even reside in London. Pope’s family, in fact, moved to a small farm in Windsor Forest, a neighbourhood occupied by other Catholic families of the gentry, and he later moved with his mother to Twickenham. However, Pope was privately taught and moved in an elite circle of London writers which included the dramatists Wycherley and Congreve, the poet Granville, the critic William Walsh, as well as the writers Addison and Steele, and the deistic politician Bolingbroke. Pope’s personal life was also afflicted by disease: he was a hunchback, only four and a half feet tall, and suffered from tuberculosis. He was in constant need of his maid to dress and care for him. Notwithstanding such social and personal obstacles, Pope produced some of the finest verse ever written. His most renowned publications include several mock-heroic poems such as The Rape of the Lock (1712; 1714), and The Dunciad (1728). His philosophical poem An Essay on Man (1733–1734) was a scathing attack on human arrogance or pride in failing to observe the due limits of human reason, in questioning divine authority and seeking to be self-reliant on the basis of rationality and science. Even An Essay on Criticism is written in verse, following the tradition of Horace’s Ars poetica , and interestingly, much of the philosophical substance of An Essay on Man is already formulated in this earlier poem, in its application to literature and criticism. While An Essay on Man identifies the chief fault of humankind as the original sin of “pride” and espouses an ethic based on an ordered and hierarchical universe, it nonetheless depicts this order in terms of Newtonian mechanism and expresses a broadly deistic vision.

The same contradictions permeate the Essay on Criticism , which effects an eclectic mixture of a Roman Catholic vision premised on the (negative) significance of pride, a humanistic secularism perhaps influenced by Erasmus, a stylistic neoclassicism with roots in the rhetorical tradition from Aristotle, Horace, Longinus, and modern disciples such as Boileau, and a modernity in the wake of figures such as Bacon, Hobbes, and Locke. Some critics have argued that the resulting conglomeration is inharmonious; in fairness to Pope, we might cite one of his portraits of the satirist:

Verse-man or Prose-man, term me which you will, Papist or Protestant, or both between, Like good Erasmus in an honest Mean, In moderation placing all my glory, While Tories call me Whig, and Whigs a Tory. ( Satire II.i)

Clearly, labels can oversimplify: yet it is beyond doubt that, on balance, Pope’s overall vision was conservative and retrospective. He is essentially calling for a return to the past, a return to classical values, and the various secularizing movements that he bemoans are already overwhelming the view of nature, man, and God that he is attempting to redeem.

Indeed, Pope’s poem has been variously called a study and defense of “nature” and of “wit.” The word “nature” is used twenty-one times in the poem; the word “wit” forty-six times. Given the numerous meanings accumulated in the word “nature” as it has passed through various traditions, Pope’s call for a “return to nature” is complex, and he exploits the multiple significance of the term to generate within his poem a comprehensive redefinition of it. Among other things, nature can refer, on a cosmic level, to the providential order of the world and the universe, an order which is hierarchical, in which each entity has its proper assigned place. In An Essay on Man Pope expounds the “Great Chain of Being,” ranging from God and the angels through humans and the lower animals to plants and inanimate objects. Nature can also refer to what is normal, central, and universal in human experience, encompassing the spheres of morality and knowledge, the rules of proper moral conduct as well as the archetypal patterns of human reason.

The word “wit” in Pope’s time also had a variety of meanings: it could refer in general to intelligence and intellectual acuity; it also meant “wit” in the modern sense of cleverness, as expressed for example in the ability to produce a concise and poignant figure of speech or pun; more specifically, it might designate a capacity to discern similarities between different entities and to perceive the hidden relationships underlying the appearances of things. In fact, during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, “wit” was the subject of a broad and heated debate. Various parties contested the right to define it and to invest it with moral significance. A number of writers such as Nicolas Malebranche and Joseph Addison , and philosophers such as John Locke, argued that wit was a negative quality, associated with a corrupting imagination, distortion of truth, profanity, and skepticism, a quality opposed to “judgment,” which was a faculty of clear and truthful insight. Literature generally had come to be associated with wit and had been under attack from the Puritans also, who saw it as morally defective and corrupting. On the other side, writers such as John Dryden and William Wycherley, as well as moralists such as the third earl of Shaftesbury, defended the use and freedom of wit. Pope’s notions of wit were worked out in the context of this debate, and his redefinition of “true” wit in Essay on Criticism was a means not only of upholding the proper uses of wit but also of defending literature itself, wit being a mode of knowing or apprehension unique to literature.1

While much of Pope’s essay bemoans the abyss into which current literary criticism has fallen, he does not by any means denounce the practice of criticism itself. While he cautions that the best poets make the best critics (“Let such teach others who themselves excell,” l. 15), and while he recognizes that some critics are failed poets (l. 105), he points out that both the best poetry and the best criticism are divinely inspired:

Both must alike from Heav’n derive their Light, These born to Judge, as well as those to Write. (ll. 13–14)

By the word “judge,” Pope refers to the critic, drawing on the meaning of the ancient Greek word krites . Pope sees the endeavor of criticism as a noble one, provided it abides by Horace’s advice for the poet:

But you who seek to give and merit Fame, And justly bear a Critick’s noble Name, Be sure your self and your own Reach to know, How far your Genius , Taste , and Learning go; Launch not beyond your Depth . . . (ll. 46–50)

Indeed, Pope suggests in many portions of the Essay that criticism itself is an art and must be governed by the same rules that apply to literature itself. However, there are a number of precepts he advances as specific to criticism. Apart from knowing his own capacities, the critic must be conversant with every aspect of the author whom he is examining, including the author’s

. . . Fable, Subject, Scope in ev’ry Page, Religion, Country, Genius of his Age: Without all these at once before your Eyes, Cavil you may, but never Criticize . (ll. 120–123)

Perhaps ironically, Pope’s advice here seems modern insofar as he calls for a knowledge of all aspects of the author’s work, including not only its subject matter and artistic lineage but also its religious, national, and intellectual contexts. He is less modern in insisting that the critic base his interpretation on the author’s intention: “In ev’ry Work regard the Writer’s End , / Since none can compass more than they Intend ” (ll. 233–234, 255–256).

Pope specifies two further guidelines for the critic. The first is to recognize the overall unity of a work, and thereby to avoid falling into partial assessments based on the author’s use of poetic conceits, ornamented language, and meters, as well as those which are biased toward either archaic or modern styles or based on the reputations of given writers. Finally, a critic needs to possess a moral sensibility, as well as a sense of balance and proportion, as indicated in these lines: “Nor in the Critick let the Man be lost! / Good-Nature and Good-Sense must ever join” (ll. 523–525). In the interests of good nature and good sense, Pope urges the critic to adopt not only habits of self-criticism and integrity (“with pleasure own your Errors past, / And make each Day a Critick on the last,” ll. 570–571), but also modesty and caution. To be truthful is not enough, he warns; truth must be accompanied by “Good Breeding” or else it will lose its effect (ll. 572–576). And mere bookish knowledge will often express itself in showiness, disdain, and an overactive tongue: “ Fools rush in where Angels fear to tread. / Distrustful Sense with modest Caution speaks” (ll. 625–626). Pope ends his advice with this summary of the ideal critic:

But where’s the Man, who Counsel can bestow, Still pleas’d to teach , and yet not proud to know ? Unbiass’d, or by Favour or by Spite ; Not dully prepossest , nor blindly right ; Tho learn’d, well-bred; and tho’ well-bred, sincere; . . . Blest with a Taste exact, yet unconfin’d; A Knowledge both of Books and Humankind ; Gen’rous Converse ; a Soul exempt from Pride ; And Love to Praise , with Reason on his Side? (ll. 631–642)

As we read through this synthesis of the qualities of a good critic, it becomes clear that they are primarily attributes of humanity or moral sensibility rather than aesthetic qualities. Indeed, the only specifically aesthetic quality mentioned here is “taste.” The remaining virtues might be said to have a theological ground, resting on the ability to overcome pride. Pope effectively transposes the language of theology (“soul,” “pride”) to aesthetics. It is the disposition of humility – an aesthetic humility, if you will – which enables the critic to avoid the arrogant parading of his learning, to avoid falling into bias, and to open himself up to a knowledge of humanity. The “reason” to which Pope appeals is not the individualistic and secular “reason” of the Enlightenment philosophers; it is “reason” as understood by Aquinas and many medieval thinkers, reason as a universal archetype in human nature, constrained by a theological framework. Reason in this sense is a corollary of humility: it is humility which allows the critic to rise above egotistical dogmatism and thereby to be rational and impartial, and aware of his own limitations, in his striving after truth. Knowledge itself, then, has a moral basis in good breeding; and underlying good breeding is the still profounder quality of sincerity, which we might understand here as a disposition commensurate with humility: a genuine desire to pursue truth or true judgment, unclouded by personal ambitions and subjective prejudices. Interestingly, the entire summary takes the form not of an assertion but of an extended question, implying that what is proposed here is an ideal type, to which no contemporary critic can answer.

Pope’s specific advice to the critic is grounded on virtues whose application extends far beyond literary criticism, into the realms of morality, theology, and art itself. It is something of an irony that the main part of his Essay on Criticism is devoted not specifically to criticism but to art itself, of which poetry and criticism are regarded as branches. In other words, Pope sees criticism itself as an art. Hence most of the guidance he offers, couched in the language of nature and wit, applies equally to poetry and criticism. Not only this, but there are several passages which suggest that criticism must be a part of the creative process, that poets themselves must possess critical faculties in order to execute their craft in a self-conscious and controlled manner. Hence there is a large overlap between these domains, between the artistic elements within criticism and the critical elements necessary to art. While Pope’s central piece of advice to both poet and critic is to “follow Nature,” his elaboration of this concept enlists the semantic service of both wit and judgment, establishing a close connection – sometimes indeed an identity – between all three terms; wit might be correlated with literature or poetry; and judgment with criticism. Because of the overlapping natures of poetry and criticism, however, both wit and judgment will be required in each of these pursuits.

Before inviting the poet and critic to follow nature, Pope is careful to explain one of the central functions of nature:

Nature to all things fix’d the Limits fit, And wisely curb’d proud Man’s pretending Wit; . . . One Science only will one Genius fit; So vast is Art, so narrow Human Wit . . . (ll. 52–53, 60–61)

Hence, even before he launches into any discussion of aesthetics, Pope designates human wit generally as an instrument of pride, as intrinsically liable to abuse. In the scheme of nature, however, man’s wit is puny and occupies an apportioned place. It is in this context that Pope proclaims his famous maxim:

First follow NATURE, and your Judgment frame By her just Standard, which is still the same: Unerring Nature , still divinely bright, Once clear , unchang’d , and Universal Light, Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart, At once the Source , and End , and Test of Art. (ll. 68–73)

The features attributed to nature include permanence or timelessness and universality. Ultimately, nature is a force which expresses the power of the divine, not in the later Romantic sense of a divine spirit pervading the physical appearances of nature but in the medieval sense of expressing the order, harmony, and beauty of God’s creation. As such, nature provides the eternal and archetypal standard against which art must be measured: the implication in the lines above is not that art imitates nature but that it derives its inspiration, purpose, and aesthetic criteria from nature.

Pope’s view of nature as furnishing the universal archetypes for art leads him to condemn excessive individualism, which he sees as an abuse of wit. Wit is abused when it contravenes sound judgment: “For Wit and Judgment often are at strife, Tho’ meant each other’s Aid, like Man and Wife ” (ll. 80–83). However, Pope does not believe, like many medieval rhetoricians, that poetry is an entirely rational process that can be methodically worked out in advance. In poetry, as in music, he points out, are “ nameless Graces which no Methods teach” (l. 144). Indeed, geniuses can sometimes transgress the boundaries of judgment and their very transgression or license becomes a rule for art:

Great Wits sometimes may gloriously offend , And rise to Faults true Criticks dare not mend ; From vulgar Bounds with brave Disorder part, And snatch a Grace beyond the Reach of Art, Which, without passing thro’ the Judgment , gains The Heart , and all its End at once attains. (ll. 152–157)

If Kant had been a poet, he might have expressed his central aesthetic ideas in this very way. Kant also believed that a genius lays down the rules for art, that those rules cannot be prescribed in advance, and that aesthetic judgment bypasses the conventional concepts of our understanding. Indeed, Kant laid the groundwork for many Romantic aesthetics, and if Pope’s passage above were taken in isolation, it might well be read as a formulation of Romantic aesthetic doctrine. It seems to assert the primacy of wit over judgment, of art over criticism, viewing art as inspired and as transcending the norms of conventional thinking in its direct appeal to the “heart.” The critic’s task here is to recognize the superiority of great wit. While Pope’s passage does indeed in these respects stride beyond many medieval and Renaissance aesthetics, it must of course be read in its own poetic context: he immediately warns contemporary writers not to abuse such a license of wit: “ Moderns , beware! Or if you must offend / Against the Precept , ne’er transgress its End ” (ll. 163–164). In fact, the passage cited above is more than counterbalanced by Pope’s subsequent insistence that modern writers not rely on their own insights. Modern writers should draw on the common store of poetic wisdom, established by the ancients, and acknowledged by “ Universal Praise” (l. 190).

Pope’s exploration of wit aligns it with the central classical virtues, which are themselves equated with nature. His initial definition of true wit identifies it as an expression of nature: “ True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest, / What oft was Thought , but ne’er so well Exprest ” (ll. 297–298). Pope subsequently says that expression is the “ Dress of Thought ,” and that “true expression” throws light on objects without altering them (ll. 315–318). The lines above are a concentrated expression of Pope’s classicism. If wit is the “dress” of nature, it will express nature without altering it. The poet’s task here is twofold: not only to find the expression that will most truly convey nature, but also first to ensure that the substance that he is expressing is indeed a “natural” insight or thought. What the poet must express is a universal truth which we will instantly recognize as such. This classical commitment to the expression of objective and universal truth is echoed a number of times through Pope’s text. For example, he admonishes both poet and critic: “Regard not then if Wit be Old or New , / But blame the False , and value still the True ” (ll. 406–407).

A second classical ideal urged in the passage above is that of organic unity and wholeness. The expression or style, Pope insists, must be suited to the subject matter and meaning: “The Sound must seem an Eccho to the Sense ” (l. 365). Elsewhere in the Essay , Pope stresses the importance, for both poet and critic, of considering a work of art in its totality, with all the parts given their due proportion and place (ll. 173–174). Once again, wit and nature become almost interchangeable in Pope’s text. An essential component underlying such unity and proportion is the classical virtue of moderation. Pope advises both poet and critic to follow the Aristotelian ethical maxim: “Avoid Extreams. ” Those who go to excess in any direction display “ Great Pride , or Little Sense ” (ll. 384–387). And once again, the ability to overcome pride – humility – is implicitly associated with what Pope calls “right Reason” (l. 211).

Indeed, the central passage in the Essay on Criticism , as in the later Essay on Man , views all of the major faults as stemming from pride: Of all the Causes which conspire to blind

Man’s erring Judgment, and misguide the Mind, . . . Is Pride , the never-failing Vice of Fools . (ll. 201–204)

It is pride which leads critics and poets alike to overlook universal truths in favor of subjective whims; pride which causes them to value particular parts instead of the whole; pride which disables them from achieving a harmony of wit and judgment; and pride which underlies their excesses and biases. And, as in the Essay on Man , Pope associates pride with individualism, with excessive reliance on one’s own judgment and failure to observe the laws laid down by nature and by the classical tradition.

Pope’s final strategy in the Essay is to equate the classical literary and critical traditions with nature, and to sketch a redefined outline of literary history from classical times to his own era. Pope insists that the rules of nature were merely discovered, not invented, by the ancients: “Those Rules of old discover’d , not devis’d , / Are Nature still, but Nature Methodiz’d ” (ll. 88–89). He looks back to a time in ancient Greece when criticism admirably performed its function as “the Muse’s Handmaid,” and facilitated a rational admiration of poetry. But criticism later declined from this high status, and those who “cou’d not win the Mistress, woo’d the Maid” (ll. 100–105). Instead of aiding the appreciation of poetry, critics, perhaps in consequence of their own failure to master the poetic art, allowed the art of criticism to degenerate into irrational attacks on poets. Pope’s advice, for both critic and poet, is clear: “Learn hence for Ancient Rules a just Esteem; / To copy Nature is to copy Them ” (ll. 139–140). Before offering his sketch of literary-critical history, Pope laments the passing of the “Golden Age” of letters (l. 478), and portrays the depths to which literature and criticism have sunk in the degenerate times of recent history:

In the fat Age of Pleasure, Wealth, and Ease, Sprung the rank Weed, and thriv’d with large Increase; When Love was all an easie Monarch’s Care; Seldom at Council , never in a War . . . . . . The following Licence of a Foreign Reign Did all the Dregs of bold Socinus drain; Then Unbelieving Priests reform’d the Nation, And taught more Pleasant Methods of Salvation; Where Heav’ns Free Subjects might their Rights dispute, Lest God himself shou’d seem too Absolute . . . . Encourag’d thus, Wit’s Titans brav’d the Skies . . . (ll. 534–537, 544–552)

Pope cites two historical circumstances here. By “easie Monarch” he refers to the reign of Charles II (1660–1685), whose father King Charles I had engaged in a war with the English Parliament, provoked by his excessive authoritarianism. Having lost the war, Charles I was beheaded in 1649, and England was ruled by Parliament, under the leadership of the Puritan Oliver Cromwell. Shortly after Cromwell’s death, a newly elected Parliament, reflecting the nation’s unease with the era of puritanical rule, invited Prince Charles to take the throne of England as Charles II. The new king, as Pope indicates, had a reputation for easy living, lax morality, and laziness. The reigns of Charles II and his brother James II (1685–1688) are known as the period of the Restoration (of the monarchy). Both kings were strongly pro-Catholic and aroused considerable opposition, giving rise to the second historical event to which Pope refers above, the Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689. In 1688 the Protestants Prince William of Orange and his wife Mary (daughter of James II) were secretly invited to occupy the throne of England. Under their rule, which Pope refers to as the “Licence of a Foreign Reign,” a Toleration Act was passed which granted religious freedom to all Christians except Catholics and Unitarians. Also enacted into law was a Bill of Rights which granted English citizens the right to trial by jury and various other rights.

Hence, as far as understanding Pope’s passage is concerned, there were two broad consequences of the Glorious Revolution. First, various impulses of the earlier Protestant Reformation, such as religious individualism and amendment of the doctrines of the Church of England, were reconfirmed. Pope refers to Faustus Socinus (1539 – 1604), who produced unorthodox doctrines denying Christ’s divinity, as being of the same theological tenor as the “Unbelieving Priests,” the Protestants, who reformed the nation. The second, even more significant, consequence of the revolution was the complete triumph of Parliament over the king, the monarchy’s powers being permanently restricted. Protestantism in general had been associated with attempts to oppose absolute government; clearly, Pope’s sympathies did not lie with these movements toward democracy. Significantly, his passage above wittily intertwines these two implications of the Glorious Revolution: he speaks sarcastically of “Heav’ns Free Subjects” disputing their rights not only with temporal power but also with God himself. Such is the social background, in Pope’s estimation, of the modern decline of poetry and criticism: religious and political individualism, the craving for freedom, and the concomitant rejection of authority and tradition, underlie these same vices in the sphere of letters, vices which amount to pride and the contravention of nature.

Pope now furnishes an even broader historical context for these modern ills. He traces the genealogy of “nature,” as embodied in classical authors, to Aristotle. Poets who accepted Aristotle’s rules of poetic composition, he suggests, learned that “Who conquer’d Nature , shou’d preside oe’r Wit ” (l. 652). In other words, the true and false uses of wit must be judged by those who have learned the rules of nature. Likewise, Horace, the next critic in the tradition Pope cites, was “Supream in Judgment, as in Wit” and “his Precepts teach but what his Works inspire” (ll. 657, 660). Other classical critics praised by Pope are Dionysius of Halicarnassus (ca. 30–7 bc) and the Roman authors of the first century Petronius and Quintilian, as well as Longinus, the first-century Greek author of On the Sublime . After these writers, who represent the classical tradition, Pope says, a dark age ensued with the collapse of the western Roman Empire at the hands of the Vandals and Goths, an age governed by “tyranny” and “superstition,” an age where “Much was Believ’d , but little understood ” (ll. 686– 689). What is interesting here is that Pope sees the medieval era as a continuation of the so-called Dark Ages. He refers to the onset of medieval theology as a “ second Deluge” whereby “the Monks finish’d what the Goths begun” (ll. 691–692). Hence, even though he was himself a Catholic and placed great stress on the original sin of pride, Pope seems to reject the traditions of Catholic theology as belonging to an age of superstition and irrational belief. He is writing here as a descendent of Renaissance thinkers who saw themselves as the true heirs of the classical authors and the medieval period as an aberration. What is even more striking is Pope’s subsequent praise of the Renaissance humanist thinker Desiderius Erasmus, who “drove those Holy Vandals off the Stage” (ll. 693–694). Erasmus, like Pope, had a love for the classics grounded on rationality and tolerance. He rejected ecclesiastical Christianity, theological dogmatism, and superstition in favor of a religion of simple and reasonable piety. His writings helped pave the way for the Protestant Reformation, though he himself was skeptical of the bigotry he saw on both Protestant and Catholic sides.

Pope’s implicit allegiance to Erasmus (and in part to contemporary figures such as Bolingbroke) points in the direction of a broad deism which, on the one hand, accommodates the significance of pride in secular rather than theological contexts, and, on the other hand, accommodates reason within its appropriate limits. His historical survey continues with praises of the “Golden Days” of Renaissance artistic accomplishments, and suggests that the arts and criticism thereafter flourished chiefly in Europe, especially in France, which produced the critic and poet Nicolas Boileau. Boileau was a classicist influenced greatly by Horace. Given Boileau’s own impact on Pope’s critical thought, we can see that Pope now begins to set the stage for his own entry into the history of criticism. While he notes that the English, “Fierce for the Liberties of Wit ,” were generally impervious to foreign literary influences, he observes that a handful of English writers were more sound: they sided with “the juster Ancient Cause , / And here restor’d Wit’s Fundamental Laws ” (ll. 721–722). The writers Pope now cites were either known to him or his tutors. He names the earl of Roscommon, who was acquainted with classical wit; William Walsh, his mentor; and finally himself, as offering “humble” tribute to his dead tutor (ll. 725–733). All in all, Pope’s strategy here is remarkable: in retracing the lineage of good criticism, as based on nature and the true use of wit, he traces his own lineage as both poet and critic, thereby both redefining or reaffirming the true critical tradition and marking his own entry into it. Pope presents himself as abiding by and exemplifying the critical virtues he has hitherto commended.

1. Edward Niles Hooker’s “Pope on Wit: The Essay on Criticism ,” in The Seventeenth Century: Studies in the History of English Thought and Literature from Bacon to Pope , R. F. Jones et al. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1951), pp. 225–246.

Share this:

Categories: Literature

Tags: Alexander Pope , An Essay on Criticism , An Essay on Man , Dionysius of Halicarnassus , Faustus Socinus , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Nicolas Malebranche , Poetry , The Dunciad , The Rape of the Lock

Related Articles

- Literary Criticism of Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism of Giovanni Boccaccio – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism of Joseph Addison – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Key Theories of Wimsatt and Beardsley – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

British Literature Wiki

An Essay on Criticism

Alexander Pope wrote An Essay on Criticism shortly after turning 21 years old in 1711. While remaining the speaker within his own poem Pope is able to present his true viewpoints on writing styles both as they are and how he feels they should be. While his poetic essay, written in heroic couplets, may not have obtained the same status as others of his time, it was certainly not because his writing was inferior (Bate). In fact, the broad background and comprehensive coverage within Pope’s work made it it one of the most influential critical essays yet to be written (Bate). It appears that through his writing Pope was reaching out not to the average reader, but instead to those who intend to be writers themselves as he represents himself as a critical perfectionist insisting on particular styles. Overall, his essay appears to best be understood by breaking it into three parts.

The scholar Walter Jackson Bate has explained the structure of the essay in the following way:

I. General qualities needed by the critic (1-200):

1. Awareness of his own limitations (46-67). 2. Knowledge of Nature in its general forms (68-87).

- Nature defined (70-79).

- Need of both wit and judgment to conceive it (80-87).

3. Imitation of the Ancients, and the use of rules (88-200).

- Value of ancient poetry and criticism as models (88-103).

- Censure of slavish imitation and codified rules (104-117).

- Need to study the general aims and qualities of the Ancients (118-140).

- Exceptions to the rules (141-168).

II. Particular laws for the critic (201-559): Digression on the need for humility (201-232):

1. Consider the work as a total unit (233-252). 2. Seek the author’s aim (253-266). 3. Examples of false critics who mistake the part for the whole (267-383).

- The pedant who forgets the end and judges by rules (267-288).

- The critic who judges by imagery and metaphor alone (289-304).

- The rhetorician who judges by the pomp and colour of the diction (305-336).

- Critics who judge by versification only (337-343).

Pope’s digression to exemplify “representative meter” (344-383). 4. Need for tolerance and for aloofness from extremes of fashion and personal mood (384-559).The fashionable critic: the cults, as ends in themselves, of the foreign (398-405), the new (406-423), and the esoteric (424-451).

- Personal subjectivity and its pitfalls (452-559).

III. The ideal character of the critic (560-744):

1. Qualities needed: integrity (562-565), modesty (566-571), tact (572-577), courage (578-583). 2. Their opposites (584-630). 3. Concluding eulogy of ancient critics as models (643-744).

To uncover the deeper meaning of An Essay on Criticism click here

Back to Alexander Pope

Poetry Prof

Read, Teach, Study Poetry

from An Essay on Criticism

Join Alexander Pope on a metaphysical journey of discovery… that will last a lifetime.

“[It is] difficult to know which part to prefer, when all is equally beautiful and noble.” Weekly Miscellany comments on the poetry of Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope spent his childhood in Windsor forest and, from an early age, gained a keen appreciation for nature. Later in his life he lived in a property by the River Thames in London where he cultivated his own garden that he opened for visitors. In today’s poem, written in 1709, we can see this love of the natural world through his shaping of elements of the landscape into an extended metaphor for knowledge. This landscape is vast and mountainous: the Alps , Europe’s largest mountain range are a prominent feature, as are hills, vales , an endless sky and eternal snows . Compared to this vast landscape, people are almost insignificant. Their role in the poem is to act as explorers who set off on a journey of discovery, trying to conquer the highest mountains by ascending to the summit; we tempt the heights of Arts… the towering Alps we try… Finally, despite being almost exhausted by his efforts, the explorer realises that his journey has barely begun; the mountain vista stretches ahead, unbroken, into the distance:

A poem’s central idea, often developed into an extended metaphor, is known as a conceit . Unlocking the first couplet should provide you the key to Pope’s conceit in An Essay on Criticism . Pope begins with a warning that:

The Pierian Spring is an important place in Greek Mythology , the source of a river of knowledge that was associated with the nine ancient Muses, themselves a metaphor for artistic inspiration. In this poem, it’s part of the landscape that functions as an extended metaphor for learning. It might seem strange that Pope begins by giving his readers a warning to taste not the waters of this river. However, it’s important to realise that Pope isn’t saying not to drink from the well of knowledge at all. He tells us to drink deep , emphasising his instruction with both alliterative D and using the imperative tense (where the verb is placed at the beginning of the line or phrase). To Pope’s mind, learning is seductive and intoxicating . Once you set out on the journey of learning, or take even a tiny sip from the wellspring of knowledge, you won’t be able to resist the temptation to learn more. Therefore, he suggests that you either prepare to immerse yourself completely in the Pierian Spring , or don’t drink at all.

Once you’ve discovered the connotations of Pierian Spring , the rest of the poem can be read as a warning (or criticism ) of anyone who is rash enough not to follow Pope’s instruction. Should you venture unprepared into the unknown, you must be clear about your limitations. As a spring is the starting point of a river, so too is it the starting point of Pope’s extended metaphor . From here, the reader sets out on a journey into an imposing mountainous landscape that, while initially appearing it can be ‘climbed’ or conquered, actually keeps expanding into an endless vista. No matter how far the explorer climbs, the top of the mountain never gets any nearer. Heights, lengthening way, increasing prospect and, most telling of all, eternal snows conjure the visual image of the landscape metaphysically stretching out in front of our weary eyes. Individual people are tiny and easily lost in this ever-shifting world. Pope creates a contrast between the boundless landscape and the bounded limits of human perception. At the last, the human explorer is tired by his efforts to conquer these mountains of knowledge – but the poem ends by revealing that he’d barely even gotten started on his journey: Hills peep o’er hills; Alps upon Alps arise .

Before we get too much further into the discussion of Pope’s ‘essay’, it might be helpful to place these lines in context. Despite the way they seem to be a complete poem in themselves, they are actually part of a much longer poem which stretches to three parts and a total of 744 lines! The eighteen-line extract you’ve read constitutes the second verse of Part 2 and it may help you to know that, in the first verse, Pope singled out pride as the characteristic that would eventually lead to the downfall of his explorer. Here are four lines from earlier in the Essay:

In this short sample, you can see the names Pope calls people who rush off on foolhardy adventures without taking the time to properly prepare: blind man , weak head and fools ! Younger readers might not enjoy this interpretation, but Pope finds the overconfidence of young people most problematic, associating youth with a kind of recklessness that, in hindsight, is misplaced.

You may argue that qualities such as fearless and passionate (fired) seem like compliments; but I detect a note of criticism in Pope’s words; he suggests that young people confuse emotion with clear thinking and they are too eager to plunge into the unknown. There’s an emphasis on speed and rashness ( pleased at first; at first sight ) that cannot last, like a novice marathon runner who goes sprinting out of the blocks while older, more wily competitors know to save themselves for the challenges ahead. While the young explorer does encounter some early success (implied by words like mount , more advanced , attained and, more significantly by an image : tread the sky ), the race is longer than the runner thought and inevitably the pace must sag. Later in the poem, positive diction disappears and words like trembling , growing labours , and tired take over as the true scale of the challenge becomes apparent. Sharp-eyed readers will already have noticed that the image of ‘treading the sky’ was in fact a simile : seem to tread the sky. Subtly, Pope’s use of a simile implies that any success the explorer thought he’d achieved wasn’t actually real.

The implication that over-enthusiasm can cloud good judgment can be traced through diction to do with looking and seeing: a t first sight, short views, see, behold, appear, survey, eyes and peep pepper the poem and convey the poet’s belief that, to our detriment, we can be short-sighted and tunnel-visioned. The eighth line of the poem is entirely concerned with this idea: short views we take, nor see the lengths behind paints a picture of a young explorer who only looks in one direction – eyes fixed straight ahead – and so misses the bigger picture.

While the poem is certainly didactic (it’s trying to impart a lesson), Pope’s tone of voice is not too condescending or stand-offish because he includes himself in his criticism as well. Throughout the poem the words us, we and our soften his accusations so there’s never a ‘them-and-us’ divide between young and old. In fact, Pope was only 21 years old when he finished his Essay on Criticism , so use your mind’s ear to imagine him speaking ruefully from experience, rather than as a nagging or pestering adult complaining about ‘young people today.’ The line Fired at first sight by what the Muse imparts is revealing in this regard. Alluding to the nine Muses of Greek mythology , this line personifies poetic inspiration, so in one sense the extended metaphor of trying to conquer an unknowable landscape represents his own experiences of writing poetry. ‘Meta-poems’ (poems about the writing of poems) actually have a name: ars poetica . Pope implies that rushing off on a path of artistic endeavour without realising the true extent of the commitment that entails is a mistake that he himself has made in his own attempts at writing.

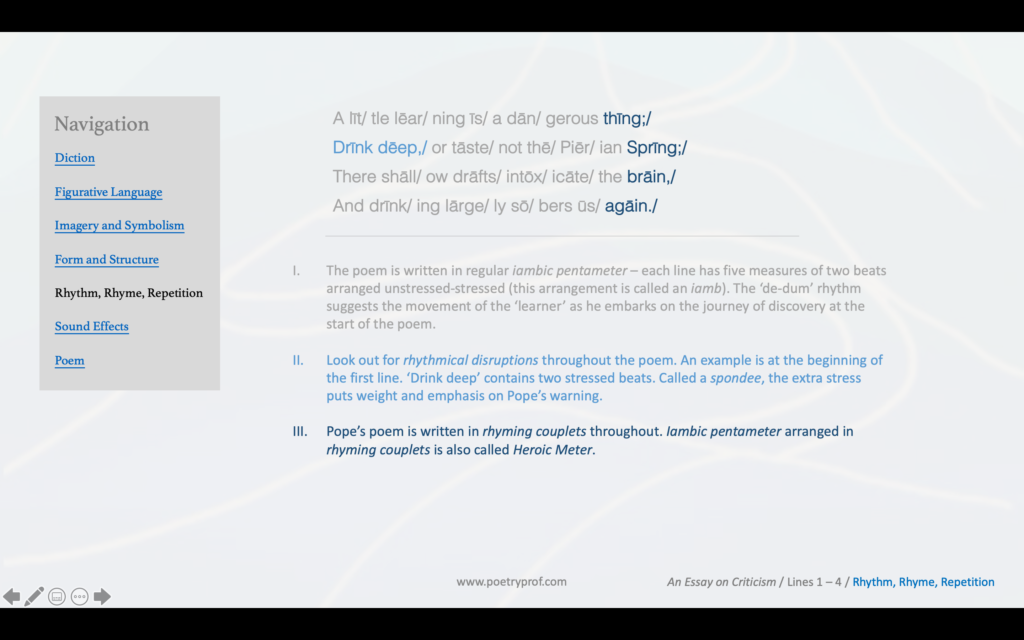

If you’re a student reading this who thinks you might be able to use Pope’s poem as an excuse not to do your homework or give up on your own writing: you shouldn’t be too rash. Pope’s not suggesting we should quit. Instead, he’s warning us that what might seem like a shallow pool is in fact a deep river of knowledge. Once you jump in, the current will sweep you away and there’s no going back. The poem is a criticism of unpreparedness and arrogance rather than an acknowledgement of futility. In fact, an element of form suggests that, for all the faults Pope has pointed out in young people who are too confident in their limited abilities, it is much more praiseworthy to try and fail to conquer the heights than never to try at all. The poem is written in iambic pentameter that is constant and regular as if, no matter how tough the going gets, the young explorer doesn’t give up. Compare these two lines, with iambic accents marked, from the beginning and end of the poem to see how the rhythm is unfailing:

More, the poem is arranged in rhyming couplets (the rhyme scheme is AA, BB, CC and so on). Rhyming couplets written in iambic pentameter are traditionally known by a more dramatic name: heroic couplets . Pope was widely considered to be the master of writing poetry in heroic couplets ; using them here implies that Pope ultimately believes any young person who’s brave – or foolhardy – enough to embark upon the lifelong journey of learning is worthy of praise.

The structure of Pope’s poetical essay matches the message he’s trying to convey – that, once you start learning, you won’t be able to stop. Look carefully at the punctuation marks, in particular his use of full stops . You’ll find the first one at the end of the fourth line, the second after the tenth and the third at the end of the poem (after eighteen lines). In other words, if the poem was arranged in verses, the first verse would be nice and short at only four lines, the second would stretch to six, but the final verse would have doubled in length to eight lines. Expanding sentences represent the conceit – a little learning is a dangerous thing – and match the images of the landscape expanding ( eternal snows , increasing prospect, lengthening way ) as you read further down the poem.

The end of the poem brings Pope’s criticism to its conclusion. We see the young explorer break through the eternal snows , climb above the clouds, and stand triumphantly on the mountain top, proudly surveying his achievements. Only now does he take a moment to look more deliberately at the mountains he’s trying to conquer:

Be alert to two words that might seem insignificant: appear and seem , words that signal the mistake the explorer made; he thought that he had already past the bulk of his journey. Read carefully to punctuation as well, and you’ll see the colon – a longer pause, which creates a caseura – representing the traveler pausing at the moment of his triumph… and it’s here that realisation finally dawns. Despite the difficulty of his climb thus far, the landscape ( increasing prospect ) stretches out endlessly in front of him: Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise . Here, repetition mixes with all that increasing and lengthening diction to create a surreal image of an ever-expanding landscape stretching out ahead. You might also notice P sounds peppering the last two lines of the poem in the words p ee p , Al p s, Al p s, and p ros p ect . Coming from a category of alliteration called plosive , this sound is excellent at conveying a release of negative emotion, as it is formed by pushing air through closed lips. The sound helps us perceive the taste of victory turning to defeat as the weary traveler’s shoulders slump at the prospect of the endless climb still to come.

What does Pope offer as a solution? He already warned us at the start of the poem: drinking largely sobers us again . Suddenly, the importance of the word sober becomes clear. While the idea of heading off on this journey of discovery was intoxicating , firing up those with passion to learn, discover and explore – the reality is very different. That young, over-confident learner/explorer is gone, replaced by a wiser, but more world-weary traveler who can finally see the true scale of the task ahead. By now it’s too late, he’s stuck on the mountain top and there’s only one thing he can do – go onwards!

So drink deep and be prepared to encounter much more than you expected when you set out on your journey.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- from Essay on Man by Alexander Pope

An Essay on Criticism was not the only poetical essay written by Pope. French writer Voltaire so admired Pope’s Essay on Man that he arranged for its translation into French and from there it spread around Europe.

- Marrysong by Dennis Scott

As in Pope’s poem, Scott creates a metaphor of the landscape to represent his marriage. He is an explorer in a strange land – each time the explorer glances up from his map, the landscape has changed and he’s lost again.

- Through the Dark Sod – As Education by Emily Dickinson

Victorians brought many different associations to all kinds of plants and flowers. In this Emily Dickinson poem, the lily represents beauty, purity and rebirth. This link will also take you to a fantastic blog which aims to read and provide comment on all of Emily Dickinson’s poems. So that’s 1 down, and nearly 2000 more to go…

- In the Mountains by Wang Wei

Often spoken of with the same reverence as Li Bai and Du Fu, Wang Wei is a famous imagist poet in China. In these exquisite portrait poems, Wang Wei paints pictures of the impressive landscapes of his mountain home.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying An Essay on Criticism at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs;

- A sample analytical paragraph for essay writing;

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem;

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on analysing diction and explaining lexical fields ;

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap;

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision;

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism ? Do you agree that the poem somewhat singles out young people? Can you relate to Pope’s messages about the temptations of learning? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

An Essay on Criticism

1928 facsimile reprint.

CRITICISM .

In search of Wit these lose their common Sense , And then turn Criticks in their own Defence. Those hate as Rivals all that write; and others But envy Wits , as Eunuchs envy Lovers . All Fools have still an Itching to deride, And fain wou'd be upon the Laughing Side: If Mævius Scribble in Apollo ' s spight, There are, who judge still worse than he can write . Some have at first for Wits , then Poets past, Turn'd Criticks next, and prov'd plain Fools at last; Some neither can for Wits nor Criticks pass, As heavy Mules are neither Horse or Ass . Those half-learn'd Witlings, num'rous in our Isle, As half-form'd Insects on the Banks of Nile ; Unfinish'd Things, one knows not what to call, Their Generation's so equivocal : To tell 'em, wou'd a hundred Tongues require, Or one vain Wit's , that wou'd a hundred tire. But you who seek to give and merit Fame, And justly bear a Critick's noble Name,

Be sure your self and your own Reach to know. How far your Genius, Taste , and Learning go; Launch not beyond your Depth, but be discreet, And mark that Point where Sense and Dulness meet . Nature to all things fix'd the Limits fit, And wisely curb'd proud Man's pretending Wit: As on the Land while here the Ocean gains, In other Parts it leaves wide sandy Plains; Thus in the Soul while Memory prevails, The solid Pow'r of Understanding fails; Where Beams of warm Imagination play, The Memory's soft Figures melt away. One Science only will one Genius fit; So vast is Art, so narrow Human Wit; Not only bounded to peculiar Arts , But oft in those , confin'd to single Parts . Like Kings we lose the Conquests gain'd before, By vain Ambition still to make them more: Each might his sev'ral Province well command, Wou'd all but stoop to what they understand .

First follow Nature , and your Judgment frame By her just Standard, which is still the same: Unerring Nature , still divinely bright, One clear, unchang'd and Universal Light, Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart, At once the Source , and End , and Test of Art . That Art is best which most resembles Her ; Which still presides , yet never does Appear ; In some fair Body thus the sprightly Soul With Spirits feeds, with Vigour fills the whole, Each Motion guides, and ev'ry Nerve sustains; It self unseen , but in th' Effects , remains. There are whom Heav'n has blest with store of Wit, Yet want as much again to manage it; For Wit and Judgment ever are at strife, Tho' meant each other's Aid, like Man and Wife . 'Tis more to guide than spur the Muse's Steed; Restrain his Fury, than provoke his Speed; The winged Courser, like a gen'rous Horse, Shows most true Mettle when you check his Course.

Against the Poets their own Arms they turn'd, Sure to hate most the Men from whom they learn'd. So modern Pothecaries , taught the Art By Doctor's Bills to play the Doctor's Part , Bold in the Practice of mistaken Rules , Prescribe, apply, and call their Masters Fools . Some on the Leaves of ancient Authors prey, Nor Time nor Moths e'er spoil'd so much as they: Some dryly plain, without Invention's Aid, Write dull Receits how Poems may be made: These lost the Sense, their Learning to display, And those explain'd the Meaning quite away. You then whose Judgment the right Course wou'd steer, Know well each Ancient's proper Character , His Fable, Subject, Scope in ev'ry Page, Religion, Country, Genius of his Age : Without all these at once before your Eyes, You may Confound , but never Criticize . Be Homer ' s Works your Study , and Delight , Read them by Day, and meditate by Night,

And tho' the Ancients thus their Rules invade, (As Kings dispense with Laws Themselves have made) Moderns , beware! Or if you must offend Against the Precept , ne'er transgress its End , Let it be seldom , and compell'd by Need , And have, at least, Their Precedent to plead. The Critick else proceeds without Remorse, Seizes your Fame, and puts his Laws in force. I know there are, to whose presumptuous Thoughts Those Freer Beauties , ev'n in Them , seem Faults: Some Figures monstrous and mis-shap'd appear, Consider'd singly , or beheld too near , Which, but proportion'd to their Light , or Place , Due Distance reconciles to Form and Grace. A prudent Chief not always must display His Pow'rs in equal Ranks , and fair Array , But with th' Occasion and the Place comply, Oft hide his Force, nay seem sometimes to Fly . Those are but Stratagems which Errors seem, Nor is it Homer Nods , but We that Dream .

Still green with Bays each ancient Altar stands, Above the reach of Sacrilegious Hands, Secure from Flames , from Envy's fiercer Rage, Destructive War , and all-devouring Age . See, from each Clime the Learn'd their Incense bring; Hear, in all Tongues Triumphant Pæans ring! In Praise so just, let ev'ry Voice be join'd, And fill the Gen'ral Chorus of Mankind ! Hail Bards Triumphant ! born in happier Days ; Immortal Heirs of Universal Praise! Whose Honours with Increase of Ages grow , As Streams roll down, enlarging as they flow! Nations unborn your mighty Names shall sound, And Worlds applaud that must not yet be found ! Oh may some Spark of your Cœlestial Fire The last, the meanest of your Sons inspire, (That with weak Wings, from far, pursues your Flights; Glows while he reads , but trembles as he writes ) To teach vain Wits a Science little known , T' admire Superior Sense, and doubt their own!

OF all the Causes which conspire to blind Man's erring Judgment, and misguide the Mind, What the weak Head with strongest Byass rules, Is Pride , the never-failing Vice of Fools . Whatever Nature has in Worth deny'd, She gives in large Recruits of needful Pride ; For as in Bodies , thus in Souls , we find What wants in Blood and Spirits , swell'd with Wind ; Pride, where Wit fails, steps in to our Defence, And fills up all the mighty Void of Sense ! If once right Reason drives that Cloud away, Truth breaks upon us with resistless Day ; Trust not your self; but your Defects to know, Make use of ev'ry Friend —— and ev'ry Foe . A little Learning is a dang'rous Thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring: There shallow Draughts intoxicate the Brain, And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fir’d with the Charms fair Science does impart, In fearless Youth we tempt the Heights of Art; While from the bounded Level of our Mind, Short Views we take, nor see the Lengths behind , But more advanc'd , survey with strange Surprize New, distant Scenes of endless Science rise! So pleas'd at first, the towring Alps we try, Mount o'er the Vales, and seem to tread the Sky; Th' Eternal Snows appear already past, And the first Clouds and Mountains seem the last: But those attain'd , we tremble to survey The growing Labours of the lengthen'd Way, Th' increasing Prospect tires our wandring Eyes, Hills peep o'er Hills, and Alps on Alps arise! [4] A perfect Judge will read each Work of Wit With the same Spirit that its Author writ , Survey the Whole , nor seek slight Faults to find; Where Nature moves , and Rapture warms the Mind;

Nor lose, for that malignant dull Delight, The gen'rous Pleasure to be charm'd with Wit. But in such Lays as neither ebb , nor flow , Correctly cold , and regularly low , That shunning Faults, one quiet Tenour keep; We cannot blame indeed —— but we may sleep . In Wit, as Nature, what affects our Hearts Is not th' Exactness of peculiar Parts; 'Tis not a Lip , or Eye , we Beauty call, But the joint Force and full Result of all . Thus when we view some well-proportion'd Dome, The World ' s just Wonder, and ev'n thine O Rome !) No single Parts unequally surprize; All comes united to th' admiring Eyes; No monstrous Height, or Breadth, or Length appear; The Whole at once is Bold , and Regular . Whoever thinks a faultless Piece to see, Thinks what ne'er was, nor is, nor e'er shall be. In ev'ry Work regard the Writer's End , Since none can compass more than they Intend ;

All which, exact to Rule were brought about, Were but a Combate in the Lists left out. What! Leave the Combate out ? Exclaims the Knight; Yes, or we must renounce the Stagyrite . Not so by Heav'n (he answers in a Rage) Knights, Squires, and Steeds, must enter on the Stage . The Stage can ne'er so vast a Throng contain. Then build a New, or act it in a Plain . Thus Criticks, of less Judgment than Caprice , Curious , not Knowing , not exact , but nice , Form short Ideas ; and offend in Arts (As most in Manners ) by a Love to Parts . Some to Conceit alone their Taste confine, And glitt'ring Thoughts struck out at ev'ry Line; Pleas'd with a Work where nothing's just or fit; One glaring Chaos and wild Heap of Wit: Poets like Painters, thus, unskill'd to trace The naked Nature and the living Grace , With Gold and Jewels cover ev'ry Part, And hide with Ornaments their Want of Art .

[5] True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest, What oft was Thought , but ne'er so well Exprest , Something , whose Truth convinc'd at Sight we find, That gives us back the Image of our Mind: As Shades more sweetly recommend the Light, So modest Plainness sets off sprightly Wit: For Works may have more Wit than does 'em good, As Bodies perish through Excess of Blood . Others for Language all their Care express, And value Books , as Women Men , for Dress: Their Praise is still —— The Stile is excellent : The Sense , they humbly take upon Content. Words are like Leaves ; and where they most abound, Much Fruit of Sense beneath is rarely found. False Eloquence , like the Prismatic Glass , Its gawdy Colours spreads on ev'ry place ; The Face of Nature was no more Survey, All glares alike , without Distinction gay:

Where-e'er you find the cooling Western Breeze , In the next Line, it whispers thro' the Trees ; If Chrystal Streams with pleasing Murmurs creep , The Reader's threaten'd (not in vain) with Sleep . Then, at the last , and only Couplet fraught With some unmeaning Thing they call a Thought , A needless Alexandrine ends the Song, That like a wounded Snake, drags its slow length along. Leave such to tune their own dull Rhimes, and know What's roundly smooth , or languishingly slow ; And praise the Easie Vigor of a Line, Where Denham ' s Strength, and Waller ' s Sweetness join. 'Tis not enough no Harshness gives Offence, The Sound must seem an Eccho to the Sense . Soft is the Strain when Zephyr gently blows, And the smooth Stream in smoother Numbers flows; But when loud Surges lash the sounding Shore, The hoarse, rough Verse shou'd like the Torrent roar. When Ajax strives, some Rocks' vast Weight to throw, The Line too labours , and the Words move slow ;

Not so, when swift Camilla scours the Plain, Flies o'er th'unbending Corn, and skims along the Main. Hear how [10] Timotheus ' various Lays surprize, And bid Alternate Passions fall and rise! While, at each Change, the Son of Lybian Jove Now burns with Glory, and then melts with Love; Now his fierce Eyes with sparkling Fury glow; Now Sighs steal out, and Tears begin to flow : Persians and Greeks like Turns of Nature found, And the World's Victor stood subdu'd by Sound ! The Pow'r of Musick all our Hearts allow; And what Timotheus was, is Dryden now. Avoid Extreams ; and shun the Fault of such, Who still are pleas'd too little , or too much . At ev'ry Trifle scorn to take Offence, That always shows Great Pride , or Little Sense ; Those Heads as Stomachs are not sure the best Which nauseate all, and nothing can digest.

Yet let not each gay Turn thy Rapture move, For Fools Admire , but Men of Sense Approve ; As things seem large which we thro' Mists descry, Dulness is ever apt to Magnify . Some French Writers, some our own despise; The Ancients only, or the Moderns prize: Thus Wit , like Faith by each Man is apply'd To one small Sect , and All are damn'd beside. Meanly they seek the Blessing to confine, And force that Sun but on a Part to Shine; Which not alone the Southern Wit sublimes, But ripens Spirits in cold Northern Climes ; Which from the first has shone on Ages past , Enlights the present , and shall warm the last: (Tho' each may feel Increases and Decays , And see now clearer and now darker Days ) Regard not then if Wit be Old or New , But blame the False , and value still the True . Some ne'er advance a Judgment of their own, But catch the spreading Notion of the Town;

They reason and conclude by Precedent , And own stale Nonsense which they ne'er invent. Some judge of Author's Names , not Works , and then Nor praise nor damn the Writings , but the Men . Of all this Servile Herd the worst is He That in proud Dulness joins with Quality , A constant Critick at the Great-man's Board, To fetch and carry Nonsense for my Lord. What woful stuff this Madrigal wou'd be, To some starv'd Hackny Sonneteer, or me? But let a Lord once own the happy Lines , How the Wit brightens ! How the Style refines ! Before his sacred Name flies ev'ry Fault, And each exalted Stanza teems with Thought! The Vulgar thus through Imitation err; As oft the Learn'd by being Singular ; So much they scorn the Crowd, that if the Throng By Chance go right, they purposely go wrong; So Schismatics the dull Believers quit, And are but damn'd for having too much Wit .

Some praise at Morning what they blame at Night; But always think the last Opinion right . A Muse by these is like a Mistress us'd, This hour she's idoliz'd , the next abus'd , While their weak Heads, like Towns unfortify'd, 'Twixt Sense and Nonsense daily change their Side. Ask them the Cause; They're wiser still , they say; And still to Morrow's wiser than to Day. We think our Fathers Fools, so wise we grow; Our wiser Sons , no doubt, will think us so. Once School-Divines our zealous Isle o'erspread; Who knew most Sentences was deepest read ; Faith, Gospel, All, seem'd made to be disputed , And none had Sense enough to be Confuted . Scotists and Thomists , now, in Peace remain, Amidst their kindred Cobwebs in Duck-Lane . If Faith it self has diff'rent Dresses worn, What wonder Modes in Wit shou'd take their Turn? Oft, leaving what is Natural and fit, The current Folly proves the ready Wit ,

And Authors think their Reputation safe, Which lives as long as Fools are pleas'd to Laugh . Some valuing those of their own Side , or Mind , Still make themselves the measure of Mankind; Fondly we think we honour Merit then, When we but praise Our selves in Other Men . Parties in Wit attend on those of State , And publick Faction doubles private Hate. Pride, Malice, Folly , against Dryden rose, In various Shapes of Parsons, Criticks, Beaus ; But Sense surviv'd, when merry Jests were past; For rising Merit will buoy up at last. Might he return, and bless once more our Eyes, New Bl —— —s and new M —— —s must arise; Nay shou'd great Homer lift his awful Head, Zoilus again would start up from the Dead. Envy will Merit as its Shade pursue, But like a Shadow, proves the Substance too; For envy'd Wit, like Sol Eclips'd, makes known Th' opposing Body's Grossness, not its own .

When first that Sun too powerful Beams displays, It draws up Vapours which obscure its Rays; But ev'n those Clouds at last adorn its Way, Reflect new Glories, and augment the Day. Be thou the first true Merit to befriend; His Praise is lost, who stays till All commend; Short is the Date, alas, of Modern Rhymes ; And 'tis but just to let 'em live betimes . No longer now that Golden Age appears, When Patriarch-Wits surviv'd a thousand Years , Now Length of Fame (our second Life) is lost, And bare Threescore is all ev'n That can boast: Our Sons their Fathers' failing Language see, And such as Chaucer is, shall Dryden be. So when the faithful Pencil has design'd Some fair Idea of the Master's Mind, Where a new World leaps out at his command, And ready Nature waits upon his Hand; When the ripe Colours soften and unite , And sweetly melt into just Shade and Light,

When mellowing Time does full Perfection give, And each Bold Figure just begins to Live ; The treach'rous Colours the few Years decay, And all the bright Creation fades away! Unhappy Wit , like most mistaken Things, Repays not half that Envy which it brings: In Youth alone its empty Praise we boast, But soon the Short-liv'd Vanity is lost! Like some fair Flow'r the in the Spring does rise, That gaily Blooms, but ev'n in blooming Dies . What is this Wit that does our Cares employ? The Owner's Wife , that other Men enjoy, Then more his Trouble as the more admir'd , Where wanted , scorn'd, and envy'd where acquir'd ; Maintain'd with Pains , but forfeited with Ease ; Sure some to vex , but never all to please ; 'Tis what the Vicious fear , the Virtuous shun ; By Fools 'tis hated , and by Knaves undone! Too much does Wit from Ign'rance undergo, Ah let not Learning too commence its Foe!

Of old , those met Rewards who cou'd excel , And such were Prais'd who but endeavour'd well : Tho' Triumphs were to Gen'rals only due, Crowns were reserv'd to grace the Soldiers too. Now those that reach Parnassus ' lofty Crown, Employ their Pains to spurn some others down; And while Self-Love each jealous Writer rules, Contending Wits becomes the Sport of Fools : But still the Worst with most Regret commend, For each Ill Author is as bad a Friend . To what base Ends, and by what abject Ways , Are Mortals urg'd by Sacred Lust of Praise ? Ah ne'er so dire a Thirst of Glory boast, Nor in the Critick let the Man be lost! Good-Nature and Good-Sense must ever join; To err is Humane ; to Forgive, Divine . But if in Noble Minds some Dregs remain, Not yet purg'd off, of Spleen and sow'r Disdain, Discharge that Rage on more Provoking Crimes, Nor fear a Dearth in these Flagitious Times.

No Pardon vile Obscenity should find, Tho' Wit and Art conspire to move your Mind; But Dulness with Obscenity must prove As Shameful sure as Impotence in Love . In the fat Age of Pleasure, Wealth, and Ease, Sprung the rank Weed, and thriv'd with large Increase; When Love was all an easie Monarch's Care; Seldom at Council , never in a War : Jilts rul'd the State, and Statesmen Farces writ; Nay Wits had Pensions , and young Lords had Wit : The Fair sate panting at a Courtier's Play , And not a Mask went un-improv'd away: The modest Fan was lifted up no more, And Virgins smil'd at what they blush'd before —— The following Licence of a Foreign Reign Did all the Dregs of bold Socinus drain; Then first the Belgian Morals were extoll'd; We their Religion had, and they our Gold: Then Unbelieving Priests reform'd the Nation, And taught more Pleasant Methods of Salvation;

Where Heav'ns Free Subjects might their Rights dispute, Lest God himself shou'd seem too Absolute . Pulpits their Sacred Satire learn'd to spare, And Vice admir'd to find a Flatt'rer there! Encourag'd thus, Witt's Titans brav'd the Skies, And the Press groan'd with Licenc'd Blasphemies —— These Monsters, Criticks! with your Darts engage, Here point your Thunder, and exhaust your Rage! Yet shun their Fault, who, Scandalously nice , Will needs mistake an Author into Vice ; All seems Infected that th' Infected spy, As all looks yellow to the Jaundic'd Eye. Learn then what Morals Criticks ought to show, For 'tis but half a Judge's Task , to Know . 'Tis not enough, Wit, Art, and Learning join; In all you speak, let Truth and Candor shine: That not alone what to your Judgment ' s due, All may allow; but seek your Friendship too.

Be silent always when you doubt your Sense; Speak when you're sure , yet speak with Diffidence ; Some positive persisting Fops we know, Who, if once wrong , will needs be always so ; But you, with Pleasure own your Errors past, And make each Day a Critick on the last. 'Tis not enough your Counsel still be true , Blunt Truths more Mischief than nice Falshoods do; Men must be taught as if you taught them not ; And Things ne'er known propos'd as Things forgot : Without Good Breeding, Truth is not approv'd, That only makes Superior Sense belov'd . Be Niggards of Advice on no Pretence; For the worst Avarice is that of Sense : With mean Complacence ne'er betray your Trust, Nor be so Civil as to prove Unjust ; Fear not the Anger of the Wise to raise; Those best can bear Reproof , who merit Praise .

'Twere well, might Criticks still this Freedom take; But Appius reddens at each Word you speak, And stares, Tremendous ! with a threatning Eye , Like some fierce Tyrant in Old Tapestry ! Fear most to tax an Honourable Fool, Whose Right it is, uncensur'd to be dull; Such without Wit are Poets when they please, As without Learning they can take Degrees . Leave dang'rous Truths to unsuccessful Satyrs , And Flattery to fulsome Dedicators , Whom, when they Praise , the World believes no more, Than when they promise to give Scribling o'er. 'Tis best sometimes your Censure to restrain, And charitably let the Dull be vain : Your Silence there is better than your Spite , For who can rail so long as they can write ? Still humming on, their old dull Course they keep, And lash'd so long, like Tops , are lash'd asleep .

False Steps but help them to renew the Race, As after Stumbling , Jades will mend their Pace. What Crouds of these, impenitently bold, In Sounds and jingling Syllables grown old, Still run on Poets in a raging Vein, Ev'n to the Dregs and Squeezings of the Brain ; Strain out the last, dull droppings of their Sense, And Rhyme with all the Rage of Impotence ! Such shameless Bards we have; and yet 'tis true, There are as mad, abandon'd Criticks too. [11] The Bookful Blockhead, ignorantly read, With Loads of Learned Lumber in his Head, With his own Tongue still edifies his Ears, And always List'ning to Himself appears. All Books he reads, and all he reads assails, From Dryden ' s Fables down to D —— — y ' s Tales .

Tho' Learn'd well-bred; and tho' well-bred, sincere; Modestly bold, and Humanly severe? Who to a Friend his Faults can freely show, And gladly praise the Merit of a Foe ? Blest with a Taste exact, yet unconfin'd; A Knowledge both of Books and Humankind ; Gen'rous Converse ; a Soul exempt from Pride ; And Love to Praise , with Reason on his Side? Such once were Criticks , such the Happy Few , Athens and Rome in better Ages knew. The mighty Stagyrite first left the Shore, Spread all his Sails, and durst the Deeps explore; He steer'd securely, and discover'd far, Led by the Light of the Mæonian Star . Not only Nature did his Laws obey, But Fancy's boundless Empire own'd his Sway. Poets, a Race long unconfin'd and free, Still fond and proud of Savage Liberty ,