An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

- v.112(46); 2015 Nov 17

Settling the debate on birth order and personality

Rodica ioana damian.

a Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, 77204;

Brent W. Roberts

b Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, IL, 61820

Author contributions: R.I.D. and B.W.R. wrote the paper.

Birth order is one of the most pervasive human experiences, which is universally thought to determine how intelligent, nice, responsible, sociable, emotionally stable, and open to new experiences we are ( 1 ). The debate over the effects of birth order on personality has spawned continuous interest for more than 100 y, both from the general public and from scientists. And yet, despite a consistent stream of research, results remained inconclusive and controversial. In the last year, two definitive papers have emerged to show that birth order has little or no substantive effect on personality. In the first paper, a huge sample was used to test the relation between birth order and personality in a between-family design, and the average effect was equal to a correlation of 0.02 ( 2 ). Now, in PNAS, Rohrer, Egloff, and Schmukle ( 3 ) investigate the link between birth order and personality in three large samples from Great Britain, the United States, and Germany, using both between- and within-family designs. The results show that birth order has null effects on personality across the board, with the exception of intelligence and self-reported intellect, where firstborns have slightly higher scores. When combined, the two studies provide definitive evidence that birth order has little or no substantive relation to personality trait development and a minuscule relation to the development of intelligence.

In the wake of these findings, one may ask why previous findings were inconclusive. To address this question, it is essential to understand the current state of research on birth order and personality, as well as the vital methodological contributions of the Rohrer et al. report ( 3 ).

Why Were Previous Studies of Birth Order Inconclusive?

Over the past two decades, hundreds of studies have produced widely ranging estimates of the effects of birth order on personality traits, falling anywhere between a correlation of 0.40 ( 1 ) and 0 ( 4 ). One possible explanation for these inconsistent findings is the pervasive use of underpowered study designs using nonrepresentative population samples. Regarding the link between birth order and intelligence, the results are much more consistent, possibly because of the large representative samples used ( 5 , 6 ). The Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) study addresses the power issues by using three large representative samples from three different countries. This is notable, because only one previous study ( 2 ) had tested the effect of birth order on

Scientific evidence strongly suggests that birth order has little or no substantive relation to personality trait development and a minuscule relation to the development of intelligence.

personality in a large representative sample (in a between-family context). The Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) study replicates the latter findings, and extends them significantly by investigating cross-national patterns and by being the first study to ever explore within-family effects simultaneously with between-family effects in large representative samples. This study also replicates results on birth order and intelligence that have been previously found in large samples in both between- and within-family designs.

A second reason for the lack of consensus has to do with changing standards on what would be deemed the optimal method for testing birth-order effects on personality. Recently, some have argued that between-family designs were inadequate and that only within-family comparisons were up to the task of testing and revealing the role of birth order on personality. A between-family study design compares the personality traits and intelligence of a cross-section of unrelated people who have different birth ranks. In contrast, a within-family design compares the personality traits and intelligence of first- and laterborn siblings from the same family. Between-family designs have been criticized primarily for not being able to adequately control for between-family differences in sibship size, genetic differences, and specific family practices ( 7 ). Ignoring these sources of variance is likely to produce biased estimates of birth-order effects. For example, sibship size, which represents the total number of siblings present in the family, is an important confound because firstborns (vs. laterborns) are more likely to be “found” in low sibships. Because wealthier more educated parents tend to have fewer children, firstborns tend to be overrepresented among families of a high socioeconomic status, the latter being related to personality and intelligence ( 8 ). Thus, any serious attempt at testing the effects of birth order on personality in a between-family design should statistically control for sibship size, which the study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) does.

The second criticism brought to between-family designs is that they do not reflect the within-family dynamics put forward by the evolutionary niche-finding model, whereby each child is trying to find a niche that has not yet been filled, to receive maximum investment from the parents ( 9 ). The study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) also addresses this issue by supplementing their between-family design with a within-family design (using a subsample of siblings from the same datasets).

Although within-family designs of birth order may be considered superior to between-family designs because they can adequately control for some confounding factors and because they reflect the within-family dynamics put forward by the evolutionary model ( 7 ), they also pose some problems. First, within-family designs, as they are currently used, tend to introduce a perfect age confound ( 10 ). Specifically, studies so far have tested all siblings at the same time, which means the firstborn was always older than the laterborns at the time of assessment. Given what we know about personality development and maturation ( 11 ), it is very possible that the firstborn only appears to be more conscientious, for example, because of being older. The study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) is the first study to date to ever address this issue when employing a within-family design by using age-adjusted t -scores.

The second criticism brought to within-family studies of birth order and personality is that they may suffer from demand effects or social stereotypes that may inflate the correlations ( 12 ). This problem is enhanced by the fact that the existing within-family research on birth order and personality has been limited by its use of a single rater from each family ( 4 ). Specifically, the single rater compares oneself against one’s siblings, thus increasing the likelihood of perceiving a contrast. The study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) addresses this issue by using independent self-reports collected from each sibling. This is only the second study to ever use independent ratings in the within-family context, and the first to do so while using large representative samples.

Finally, Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) tested the robustness of their findings by conducting additional analyses. One important finding was that the results did not differ by gender, which is relevant because previous theories proposed that stronger effects may emerge among pairs of male siblings ( 13 ). Another important finding is that limiting the data to an age gap between siblings no larger than 5 y also did not change the results. This is important because previous theory ( 1 ) suggested that large age gaps make the effects disappear because there is no sibling competition within the family, but that strong effects should appear for age gaps smaller than 5 y. Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) did not find support for this idea, and their study is unique in its ability to test this hypothesis in a large sample.

In sum, by using large representative samples from three different countries, by assessing personality traits and intelligence in the same study, by using both between- and within-family designs, by using independent self-reports of personality in the within-family context, by taking into account important confounds (such as sibship size in the between-family context and age in the within-family context), and by testing the robustness of the findings in multiple additional analyses, this is the most methodologically sound birth order study to date ( 3 ). When combined with the prior study by Damian and Roberts ( 2 ), which was the largest test of birth order and personality relations, the conclusion is inescapable. Birth order is not an important factor for personality development.

Why Has Birth Order Persisted and Why Might it Still Persist as a Zombie Theory?

If science is truly self-correcting, we feel that the Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) study, when combined with the Damian and Roberts ( 2 ) study, should be the standard against which any new studies on birth order and personality are considered. The largest, most methodologically sophisticated studies in existence show little or no functional relation between birth order and personality. Newer data will have to provide evidence for much larger effects in equally large samples to counter the weight of the evidence.

We are not optimistic that opinions on the effect of birth order will change quickly for a variety of reasons. First, change in science happens slowly. It may take a few years for researchers to digest these findings. Second, some researchers will point out that some of the effects, though quite small in size, were still statistically significant. Although technically correct, this position fails theoretically because the idea of a birth-order effect on personality has always been proposed under the assumption that it could be seen within any given family. We know from past research that it is difficult for observers to detect personality differences that are smaller than one standard deviation in size ( 14 ). The largest birth-order effects we could find were on the order of a 10th of a standard deviation, with the average effect being equivalent to a 25th of a standard deviation. Even if the difference turns out to be statistically significant, it fails to reach a level that parents, relatives, siblings, or friends could notice. In that way, birth-order theory fails despite the statistically significant effects demonstrated in these large studies.

Third, and possibly most interestingly, birth order is an idea that will probably never go away entirely because of its perfect confounding with age. This means that almost everyone has direct experience in which they see older children, who are firstborn, acting and behaving differently than younger children, who are laterborn. Because people are susceptible to weighing anecdotal information more heavily than data-driven findings ( 15 ), there will always be a tendency to think that birth-order effects exist because they will be confused with age differences. The interesting aspect of this perfect confound is that this is one circumstance where personal experience will be wrong and the truth can only be discovered through good scientific reasoning and investigation. The problem in this case is that data-driven findings are seldom as compelling as personal experience.

In conclusion, scientific evidence strongly suggests that birth order has little or no substantive relation to personality trait development and a minuscule relation to the development of intelligence. We commend Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) for conducting the most thorough and methodologically sophisticated examination of the relation between birth order and personality to date. We hope, that the cumulative evidence on birth order and personality is now compelling enough that the idea does not simply become undead ( 16 ), but is clearly laid to rest as a viable explanation for the fascinating differences we see across people and siblings in the typical ways in which they feel, think, and behave.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 14224 .

The Reporter

New Evidence on the Impacts of Birth Order

What determines a child's success? We know that family matters — children from higher socioeconomic status families do better in school, get more education, and earn more.

However, even beyond that, there is substantial variation in success across children within families. This has led researchers to study factors that relate to within-family differences in children's outcomes. One that has attracted much interest is the role played by birth order, which varies systematically within families and is exogenously determined.

While economists have been interested in understanding human capital development for many decades, compelling economic research on birth order is more recent and has largely resulted from improved availability of data. Early work on birth order was hindered by the stringent data requirements necessary to convincingly identify the effects of birth order. Most importantly, one needs information on both family size and birth order. As there is only a third-born child in a family with at least three children, comparing third-borns to firstborns across families of different sizes will conflate the birth order effect with a family size effect, so one needs to be able to control for family size. Additionally, it is beneficial to have information on multiple children from the same family so that birth order effects can be estimated from within-family differences in child outcomes; otherwise, birth order effects will be conflated with other effects that vary systematically with birth order, such as cohort effects. Large Scandinavian register datasets that became available to researchers beginning in the late 1990s have enabled birth order research, as they contain population data on both family structure and a variety of child outcomes. Here, I describe my research with a number of coauthors, using these data to explore the effects of birth order on outcomes including human capital accumulation, earnings, development of cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and health.

Birth Order and Economic Success

Almost a half-century ago, economists including Gary Becker, H. Gregg Lewis, and Nigel Tomes created models of quality-quantity trade-offs in child-rearing and used these models to explore the role of family in children's success. They sought to explain an observed negative correlation between family income and family size: if child quality is a normal good, as income rises the family demands higher-quality children at the cost of lower family size. 1

However, this was a difficult model to test, as characteristics other than family income and child quality vary with family size. The introduction of natural experiments, combined with newly available large administrative datasets from Scandinavia, made testing such a model possible.

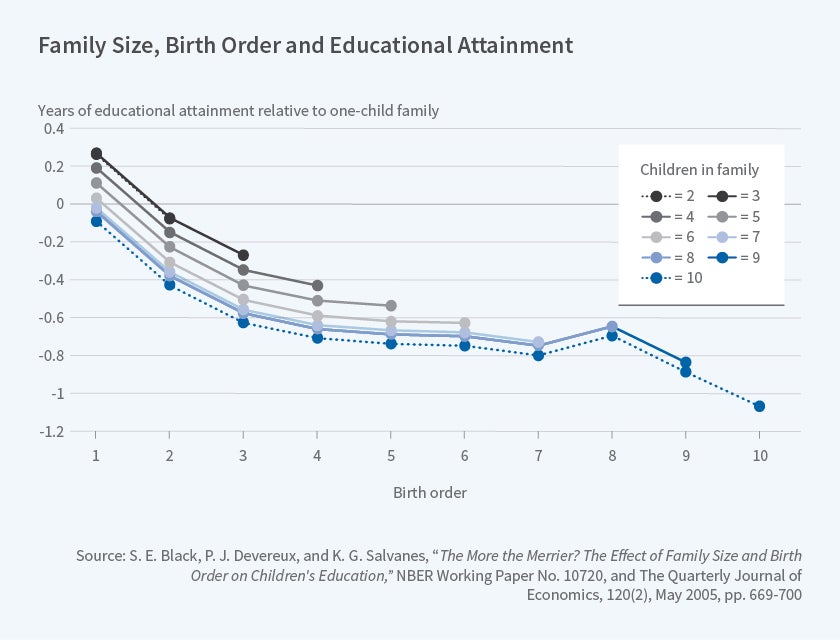

In my earliest work on the topic, Paul Devereux, Kjell Salvanes, and I took advantage of the Norwegian administrative dataset and set out to better understand this theoretical quantity-quality tradeoff. 2 It became clear that child "quality" was not a constant within a family — children within families were quite different, despite the model assumptions to the contrary. Indeed, we found that birth order could explain a large fraction of the family size differential in children's educational outcomes. Average educational attainment was lower in larger families largely because later-born children had lower average education, rather than because firstborns had lower education in large families than in small families. We found that firstborns had higher educational attainment than second-borns who in turn did better than third-borns, and so on. These results were robust to a variety of specifications; most importantly, we could compare outcomes of children within the same families.

To give a sense of the magnitude of these effects: The difference in educational attainment between the first child and the fifth child in a five-child family is roughly equal to the difference between the educational attainment of blacks and whites calculated from the 2000 Census. We augmented the education results by examining earnings, whether full-time employed, and whether one had a child as a teenager as additional outcome variables, and found strong evidence for birth order effects, particularly for women. Later-born women have lower earnings (whether employed full-time or not), are less likely to work full-time, and are more likely to have their first child as teenagers. In contrast, while later-born men have lower full-time earnings, they are not less likely to work full-time [Figure 1].

Birth Order and Cognitive Skills

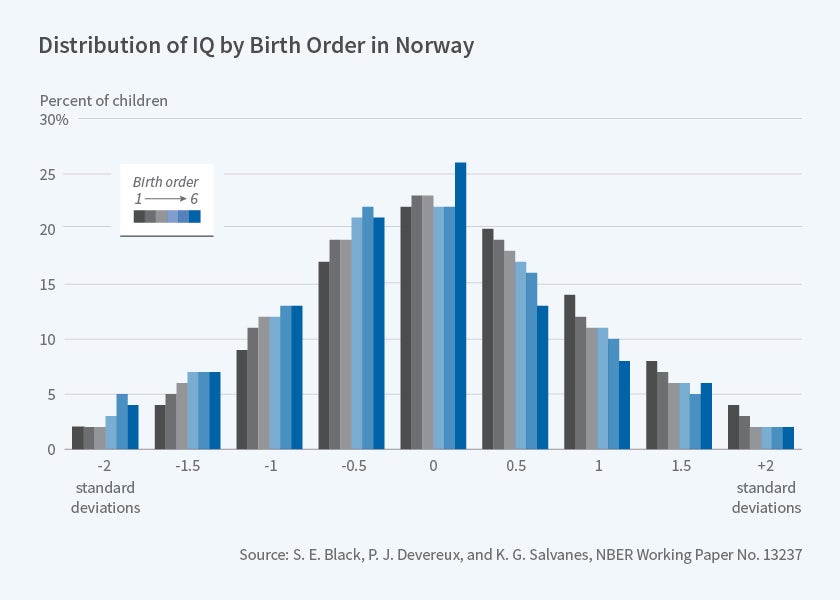

One possible explanation for these differences is that cognitive ability varies systematically by birth order. In subsequent work, Devereux, Salvanes, and I examined the effect of birth order on IQ scores. 3

The psychology literature has long debated the role of birth order in determining children's IQs; this debate was seemingly resolved when, in 2000, J. L. Rodgers et al. published a paper in American Psychologist entitled "Resolving the Debate Over Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence" that referred to the apparent relationship between birth order and IQ as a "methodological illusion." 4 However, this work was limited due to the absence of large representative datasets necessary to identify these effects. We again used population register data from Norway to estimate this relationship.

To measure IQ, we used the outcomes of standardized cognitive tests administered to Norwegian men between the age of 18 and 20 when they enlist in the military. Consistent with our earlier findings on educational attainment but in contrast to the previous work in the literature, we found strong birth order effects on IQ that are present when we look within families. Later-born children have lower IQs, on average, and these differences are quite large. For example, the difference between firstborn and second-born average IQ is on the order of one-fifth of a standard deviation, or about three IQ points. This translates into approximately a 2 percent difference in annual earnings in adulthood.

The Effect of Birth Order on Non-Cognitive Skills

Personality is another factor that is posited to vary by birth order, a proposition that has been particularly difficult to assess in a compelling way due to the paucity of large datasets containing information on individual personality. In recent work on the topic, Erik Gronqvist, Bjorn Ockert, and I use Swedish administrative datasets to examine this issue. 5

In the economics literature, personality traits are often referred to as non-cognitive abilities and denote traits that can be distinguished from intelligence. 6 To measure "personality" (or non-cognitive skills), we use the outcome of a standardized psychological evaluation, conducted by a certified psychologist, that is performed on all Swedish men between the ages of 18 and 20 when they enlist in the military, and which is strongly related to success in the labor market. An individual is given a higher score if he is considered to be emotionally stable, persistent, socially outgoing, willing to assume responsibility, and able to take initiative. Similar to the results for cognitive skills, we find evidence of consistently lower scores in this measure for later-born children. Third-born children have non-cognitive abilities that are 0.2 standard deviations below firstborn children. Interestingly, boys with older brothers suffer almost twice as much in terms of these personality characteristics as boys with older sisters.

Importantly, we also demonstrate that these personality differences translate into differences in occupation choice by birth order. Firstborn children are significantly more likely to be employed and to work as top managers, while later-born children are more likely to be self-employed. More generally, firstborn children are more likely to be in occupations requiring sociability, leadership ability, conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability, extraversion, and openness.

The Effect of Birth Order on Health

Finally, how do these differences translate into later health? In more recent work, Devereux, Salvanes, and I analyze the effect of birth order on health. 7 There is a sizable body of literature about the relationship between birth order and adult health; individual studies have typically examined only one or a small number of health outcomes and, in many cases, have used relatively small samples. Again, we use large nationally representative data from Norway to identify the relationship between birth order and health when individuals are in their 40s, where health is measured along a number of dimensions, including medical indicators, health behaviors, and overall life satisfaction.

The effects of birth order on health are less straightforward than other outcomes we have examined, as firstborns do better on some dimensions and worse on others. We find that the probability of having high blood pressure declines with birth order, and the largest gap is between first- and second-borns. Second-borns are about 3 percent less likely to have high blood pressure than firstborns; fifth-borns are about 7 percent less likely to have high blood pressure than firstborns. Given that 24 percent of this population has high blood pressure, this is quite a large difference. Firstborns are also more likely to be overweight and obese. Compared with second-borns, firstborns are 4 percent more likely to be overweight and 2 percent more likely to be obese. The equivalent differences between fifth-borns and firstborns are 10 percent and 5 percent. For context, 47 percent of the population is overweight and 10 percent is obese. Once again, the magnitudes are quite large.

However, later-borns are less likely to consider themselves to be in good health, and measures of mental health generally decline with birth order. Later-born children also exhibit worse health behaviors. The number of cigarettes smoked daily increases monotonically with birth order, suggesting that the higher prevalence of smoking by later-borns found among U.S. adolescents by Laura M. Argys et al. 8 may persist throughout adulthood and, hence, have important effects on health outcomes.

Possible Mechanisms

Why are adult outcomes likely to be affected by birth order? A host of potential explanations has been proposed across several academic disciplines.

A number of biological factors may explain birth order effects. These relate to changes in the womb environment or maternal immune system that occur over successive births. Beyond biology, parents could have other influences. Childhood inputs, especially in the first years of life, are considered crucial for skill formation. 9 Firstborn children have the full attention of parents, but as families grow the family environment is diluted and parental resources become scarcer. 10 In contrast, parents are more experienced and tend to have higher incomes when raising later-born children. In addition, for a given amount of resources, parents may treat firstborn children differently than second- or later-born children. Parents may use more strict parenting practices toward the firstborn, so as to gain a reputation for "toughness" necessary to induce good behavior among later-borns. 11

There are also theories that suggest that interactions among siblings can shape birth order effects. For example, based on evolutionary psychology, Frank J. Sulloway suggests that firstborns have an advantage in following the status quo, while later-borns — by having incentives to engage in investments aimed at differentiating themselves — become more sociable and unconventional in order to attract parental resources. 12

In each of these papers, we attempted to identify potential mechanisms for the patterns we observed. However, it is here we see the limitations of these large administrative datasets, as for the most part, we lack necessary detailed information on biological factors and on household dynamics when the children are young. However, we do have some evidence on the role of biological factors. Later-born children tend to have better birth outcomes as measured by factors such as birth weight. In our Swedish data, we took advantage of the fact that some children's biological birth order is different from their environmental birth order, due to the death of an older sibling or because their parent gave up a child for adoption. When we examine this subsample, we find that the birth order effect on occupational choice is entirely driven by the environmental birth order, again suggesting that biological factors may not be central.

Also in our Swedish study, we found that firstborn teenagers are more likely to read books, spend more time on homework, and spend less time watching TV or playing video games. Parents spend less time discussing school work with later-born children, suggesting there may be differences in parental time investments. Using Norwegian data, we found that smoking early in pregnancy is more prevalent for first pregnancies than for later ones. However, women are more likely to quit smoking during their first pregnancy than during later ones, and firstborns are more likely to be breastfed. These findings suggest that early investments may systematically benefit firstborns and help explain their generally better outcomes.

In the past two decades, with the increased accessibility of administrative datasets on large swaths of the population, economists and other researchers have been better able to identify the role of birth order in the outcomes of children. There is strong evidence of substantial differences by birth order across a range of outcomes. While I have described several of my own papers on the topic, a number of other researchers have also taken advantage of newly available datasets in Florida and Denmark to examine the role of birth order on other important outcomes, specifically juvenile delinquency and later criminal behavior. 13 Consistent with the work discussed here, later-born children experience higher rates of delinquency and criminal behavior; this is at least partly attributable to time investments of parents.

Researchers

More from nber.

G. Becker, "An Economic Analysis of Fertility," in Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries , New York, Columbia University Press, 1960, pp. 209-40; G. Becker and H. Lewis, "Interaction Between Quantity and Quality of Children," in Economics of the Family: Marriage, Children, and Human Capital , 1974, pp. 81-90; G. Becker and N. Tomes, "Child Endowments, and the Quantity and Quality of Children," NBER Working Paper 123 , February 1976.

S. Black, P. Devereux, and K. Salvanes, "The More the Merrier? The Effect of Family Composition on Children's Education" NBER Working Paper 10720 , September 2004, and Quarterly Journal of Economics , 120(2), 2005, pp. 669-700.

S. Black, P. Devereux, and K. Salvanes, "Older and Wiser? Birth Order and the IQ of Young Men," NBER Working Paper 13237 , July 2007, and CESifo Economic Studies , Oxford University Press, vol. 57(1), pages 103-20, March 2011.

J. Rodgers, H. Cleveland, E. van den Oord, and D. Rowe, "Resolving the Debate Over Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence," American Psychologist , 55(6), 2000, pp. 599-612.

S. Black, E. Gronqvist, and B. Ockert, "Born to Lead? The Effect of Birth Order on Non-Cognitive Abilities," NBER Working Paper 23393 , May 2017.

L. Borghans, A. Duckworth, J. Heckman, and B. ter Weel, "The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits," Journal of Human Resources , 43, 2008, pp. 972-1059.

S. Black, P. Devereux, K. Salvanes, "Healthy (?), Wealthy, and Wise: Birth Order and Adult Health, NBER Working Paper 21337 , July 2015.

L. Argys, D. Rees, S. Averett, and B. Witoonchart, "Birth Order and Risky Adolescent Behavior," Economic Inquiry , 44(2), 2006, pp. 215-33.

F. Cunha and J. Heckman, "The Technology of Skill Formation," NBER Working Paper 12840 , January 2007.

R. Zajonc and G. Markus, "Birth Order and Intellectual Development," Psychological Review , 82(1), 1975, pp. 74-88; R. Zajonc, "Family Configuration and Intelligence," Science , 192(4236), 1976, pp. 227-36; J. Price, "Parent-Child Quality Time: Does Birth Order Matter?" in Journal of Human Resources , 43(1), 2008, pp. 240-65; J.Lehmann, A. Nuevo-Chiquero, and M. Vidal-Fernandez, "The Early Origins of Birth Order Differences in Children's Outcomes and Parental Behavior," forthcoming in Journal of Human Resources .

V. Hotz and J. Pantano, "Strategic Parenting, Birth Order, and School Performance," NBER Working Paper 19542 , October 2013, and Journal of Population Economics , 28(4), 2015, pp. 911-936. ↩

F. Sulloway, Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives , New York, Pantheon Books, 1996.

S. Breining, J. Doyle, D. Figlio, K. Karbownik, J. Roth, "Birth Order and Delinquency: Evidence from Denmark and Florida," NBER Working Paper 23038 , January 2017.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Does Birth Order Shape Your Personality?

Beware the stereotypes

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Yolanda Renteria, LPC, is a licensed therapist, somatic practitioner, national certified counselor, adjunct faculty professor, speaker specializing in the treatment of trauma and intergenerational trauma.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YolandaRenteria_1000x1000_tight_crop-a646e61dbc3846718c632fa4f5f9c7e1.jpg)

Verywell Mind / Getty Images

What Is Adler’s Birth Order Theory?

First-born child, middle child.

- Impact on Relationships

Debunking Myths and Limitations

Birth order refers to the order a child is born in relation to their siblings, such as whether they are first-born, middle-born, or last-born. You’ve probably heard people joke about how the eldest child is the bossy one, the middle child is the peace-maker, and the youngest child is the irresponsible rebel—but is there any truth to these stereotypes?

Psychologists often look at how birth order can affect development, behavior patterns, and personality characteristics, and there is some evidence that birth order might play a role in certain aspects of personality .

At a Glance

Researchers often explore how birth order, including the differences in parental expectations and sibling dynamics, can affect development and character. According to some researchers, firstborns, middle children, youngest-children, and only child-children often exhibit distinctive characteristics that are strongly influenced by how birth order shapes parental and sibling behaviors.

Early in the 20th century, the Austrian psychiatrist Alfred Adler introduced the idea that birth order could impact development and personality. Adler, the founder of individual psychology, was heavily influenced by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud .

Key points of Adler's birth order theory were that firstborns were more likely to develop a strong sense of responsibility, middleborns a desire for attention, and lastborns a sense of adventure and rebellion.

Adler also notably introduced the concept of the " family constellation ." This idea emphasizes the dynamics that form between family members and how these interactions play a part in shaping individual development.

Adler's birth order theory suggests that firstborns get more attention and time from their parents. New parents are still learning about child-rearing, which means that they may be more rule-oriented, strict, cautious, and sometimes even neurotic .

They are often described as responsible leaders with Type A personalities , a phenomenon sometimes referred to as " oldest-child syndrome ."

"Older siblings, regardless of gender, often feel more deprived or envious since they have experienced having another child divert attention away from them at some point in their lives. They tend to be more success-oriented,” explains San Francisco therapist Dr. Avigail Lev.

Firstborn children are often described as:

- High-achieving (or sometimes even over-achieving )

- Structured and organized

- Responsible

All this extra attention firstborns enjoy changes abruptly when younger siblings come along. When you become an older sibling, you suddenly have to share your parent's attention. You may feel that your parents have higher expectations for you and look to you to set an example for your younger siblings.

Consider the experiences of the oldest siblings, who are frequently tasked with caring for younger siblings. Because they are often expected to help fill the role of caregivers, they may be more nurturing, responsible, and motivated to excel.

Such traits are affected not only by birth order but also by how your position in the family affects your parent's expectations and your relationship with your younger siblings.

Research has found that firstborn kids tend to have more advanced cognitive development , which may also confer advantages when it comes to school readiness skills. However, it's important to remember that being the oldest child can also come with challenges, including carrying the weight of expectations and the burden of taking a caregiver role within the family.

Adler suggested that middle children tend to become the family’s peacemaker since they often have to mediate conflicts between older and younger siblings. Because they tend to be overshadowed by their eldest siblings, middle children may seek social attention outside of the family.

In families with three children, the youngest male sibling is likely to be more passive or easy-going.

Middleborns are often described as:

- Independent

- Peacemakers

- People pleasers

- Attention-seeking

- Competitive

While they tend to be adaptable and independent, they can also have a rebellious streak that tends to emerge when they want to stand apart from their siblings.

" Middle child syndrome " is a term often used to describe the negative effects of being a middle child. Because middle kids are sometimes overlooked, they may engage in people-pleasing behaviors as adults as a way to garner attention and favor in their lives.

While research is limited, some studies have shown that middle kids are less likely to feel close to their mothers and are more likely to have problems with delinquency.

Some research suggests that middle children may be more sensitive to rejection . As a middle child, you may feel like you didn't get as much attention and were constantly in competition with your siblings. You may struggle with feelings of insecurity, fear of rejection, and poor self-confidence .

Lastborns, often referred to as the "babies" of the family, are often seen as spoiled and pampered compared to their older siblings. Because parents are more experienced at this point (and much busier), they often take a more laissez-faire approach to parenting .

Last-born children are sometimes described as:

- Free-spirited

- Manipulative

- Self-centered

- Risk-taking

Adler's theory suggests that the youngest children tend to be outgoing, sociable, and charming. While they often have more freedom to explore, they also often feel overshadowed by their elder siblings, referred to as " youngest child syndrome ."

Because parents are sometimes less strict and disciplined with last-borns, these kids may have fewer self-regulation skills.

"If the youngest of many children is female, she tends to be more coddled or cared for, leading to a greater reliance on others compared to her older siblings, especially in larger families," Lev suggests.

Only children are unique in that they never have to share their parents' attention and resources with a sibling. It can be very much like being a firstborn in many ways. These kids may be doted on by their caregivers, but never have younger siblings to interact with, which may have an impact on development.

Only children are often described as:

- Perfectionistic

- High-achieving

- Imaginative

- Self-reliant

Because they interact with adults so much, only children often seem very mature for their age. If you're an only child, you may feel more comfortable being alone and enjoy spending time in solitude pursuing you own creative ideas. You may like having control and, because of your parents' high expectations, have strong perfectionist tendencies .

How Birth Order Influences Relationships

Birth order may affect relationships in a wide variety of ways. For example, it may impact how you form connections with other people. It can also affect how you behave within these relationships.

Dr. Lev suggests that the effects of birth order can differ depending on gender.

"For instance, in a family with two female siblings, the younger one often appears more confident and empowered, while the older one is more achievement-focused and insecure," she explains.

She also suggests that there is often a notable rivalry between same-sex siblings versus that of mixed-gender siblings. Again, this effect can vary depending on gender. Where an older sister might be less secure and the younger sister more secure, the opposite is often true when it comes to older and younger brothers.

"This could be because older sisters often assume a motherly role, while older brothers might take on more of a bully role. As a result, younger brothers are generally more insecure, whereas younger sisters tend to be more confident than their older siblings," she explains.

Some other potential effects include:

Communication

Birth order can affect how you communicate with others, which can have a powerful impact on relationship dynamics.

- Firstborns and only children are often seen as more direct, which others can sometimes interpret as bossy or controlling.

- Middle children may be less confrontational and more likely to look for solutions that will accommodate everyone.

- Lastborns, on the other hand, may rely more on their sense of humor and charm to guide their social interactions.

Relationship Roles

Birth order may also influence the roles that you take on in a relationship.

- Firstborns, for example, may be more likely to take on a caregiver role. This can be nurturing and supportive, but it can sometimes make partners feel like they are being "parented."

- Middle children are more likely to be flexible and take a more easygoing approach.

- Lastborns may be more carefree and less rigid.

Expectations

What we expect from relationships can sometimes also be influenced by birth order.

- Firstborns often have high expectations of themselves and others, sometimes leading to criticism when people fall short.

- Middle children are more prone to seek balance in relationships and want to make sure that everyone is treated fairly and contributing equally.

- Lastborns may place the burden of responsibility on their partner's shoulders while they take a more laissez-faire approach.

"Generally, older siblings are more likely to be in the scapegoat role, while the youngest siblings often have a more idealized view of the family," Lev explains.

Other Factors Play a Role

How birth order influences interpersonal relationships can also be influenced by other factors. Some of these include personality differences, parenting styles , the parents' relationship with one another, and even the birth order of the parents themselves.

While birth order theory holds a popular position in culture, much of the available evidence suggests that it likely only has a minimal impact on developmental outcomes. In other words, birth order is only one of many factors that affect how we grow and learn.

While some research suggests that there are some small personality differences between the oldest and youngest siblings, researchers have concluded that there are no significant differences in personality or cognitive abilities based on birth order.

Birth order doesn't exist in a vacuum. Genetics, socioeconomic status, family resources, health factors, parenting styles, and other environmental variables influence child development. Other family factors, such as age spacing between siblings, sibling gender, and the number of kids in a family, can also moderate the effects of birth order.

Adler’s birth order theory suggests that the order in which you are born into your family can have a lasting impact on your behavior, emotions, and relationships with other people. While there is some support indicating that birth order can affect people in small ways, keep in mind that it is just one part of the developmental puzzle.

Family dynamics are complex, which means that your relationships with both your parents and siblings are influenced by factors like genetics, environment, child temperament, and socioeconomic status.

In other words, there may be some truth to the idea that firstborns get more attention (and responsibility), that middleborns get less attention (and more independence), and that lastborns get more freedom (and less discipline). But the specific dynamics in your family might hinge more on things like resources and parenting styles than on whether you arrived first, middle, or last.

Individual aspects of your own personality are shaped by many things, but you may find it helpful to reflect on your own experiences in your family and consider the influence that birth order might have had.

Damian RI, Roberts BW. Settling the debate on birth order and personality . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 2015;112(46):14119-14120. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519064112

Luo R, Song L, Chiu I. A closer look at the birth order effect on early cognitive and school readiness development in diverse contexts . Frontiers in Psychology . 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.871837

Salmon CA, Daly M. Birth order and familial sentiment . Evolution and Human Behavior . 1998;19(5):299-312. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(98)00022-1

Cundiff PR. Ordered delinquency: the "effects" of birth order on delinquency . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 2013;39(8):1017-1029. doi:10.1177/0146167213488215

Çabuker ND, Batık HESBÇMV. Does psychological birth order predict identity perceptions of individuals in emerging adulthood? International Online Journal of Educational Sciences. 2020;12(5):164–176.

Damian RI, Roberts BW. The associations of birth order with personality and intelligence in a representative sample of U.S. high school students . Journal of Research in Personality . 2015;58:96-105. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2015.05.005

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Does Birth Order Really Determine Personality? Here’s What the Research Says

O ne Friday afternoon at a party, I’m sitting next to a mother of two. Her baby is only a couple of weeks old. They’d taken a long time, she tells me, to come up with a name for their second child. After all, they’d already used their favorite name: it had gone to their first.

On the scale of a human life, it’s small-fry, but as a metaphor I find it significant. I think of the proverbs we have around second times—second choice, second place, second fiddle, eternal second. I think of Buzz Aldrin, always in the shadow of the one who went before him, out there on the moon. I think of my sister and my son: both second children.

I was the first child in our family. I was also fearful of failure, neurotic, a perfectionist, ambitious—undoubtedly to the point of being unbearable. My sister didn’t study as hard and went out more, worked at every trendy bar in town and spent many an afternoon in front of the TV.

I’d long attributed the differences in our characters to the different positions we held in our family. It seemed to me, all things considered, better to be the firstborn: you had to work harder to expand the boundaries your parents set for you, had a greater sense of responsibility, more persistence, and emerged, in the end, more self-confident.

That theory worked in my favor, but during my second pregnancy, I started to feel sorry for my son. Through no fault of his own, he’d missed out on the enviable position of firstborn. It took that sense of pity for me to realize that I could try to uncover the basis of my ideas about the personality traits of first and second children—and whether there was anything to them.

It was 1874, and Francis Galton , an intellectual all-rounder and a half cousin of Charles Darwin, published English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture . In his book, he profiled 180 prominent scientists, and in the course of his research Galton noticed something peculiar: among his subjects, firstborns were overrepresented.

Galton’s observation was the first in a long line of scientific and pseudoscientific publications on the birth-order effect. The greater chance of success for firstborns, in Galton’s view, was because of their upbringing, an explanation that fitted in with the mores of the Victorian era: eldest sons had a greater chance of having their education paid for by their parents, parents gave their eldest sons more attention as well as responsibility, and in families of limited financial resources, parents might care just a little bit better for their firstborns.

Read more: I Raised Two CEOs and a Doctor. These Are My Secrets to Parenting Successful Children

The distribution system at the foundation of this is called primogeniture: the right of the eldest son (or less frequently, the eldest daughter) as heir. Among Portuguese nobility in the 15th and 16th centuries, for example, second- and later-born sons were sent to the front as soldiers more often than firstborn sons. Second and subsequent daughters were more likely than eldest daughters to end up in the convent. In Venice in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was generally the eldest brother who was permitted to marry, after which younger brothers would live with him and his family, dependent and subservient.

Apart from a few royal families, primogeniture is no longer the norm in Western countries. Somewhere in the course of the last century, most residents of industrialized countries became convinced that love, attention, time and inheritance should be divided equally and fairly among our offspring.

That’s what my partner and I strive to achieve: equal treatment of our two children. But we can’t get around the fact that first, second and subsequent children have slightly different starting points. The question is what consequences that has, exactly – and how insurmountable they are.

At the start of the 20th century, Alfred Adler, Freud’s erstwhile follower, the one who believed that the arrival of a younger sibling meant the dethronement of the firstborn, introduced the birth-order effect into the domain of personality psychology. According to Adler, the eldest identifies most with the adults in his environment and therefore develops both a greater sense of responsibility and more neuroses. The youngest has the greatest chance of being spoiled and is also, often, more creative. All children in the middle—Adler was a middle child—are emotionally more stable and independent: they’re the peacemakers, used to sharing from the start.

After Galton and Adler, the idea that family position affects personality has been subjected to many a scientific test. These tests generated factoids that undoubtedly still fly across the table at Christmas dinners: that firstborn children are overrepresented as Nobel Prize winners, composers of classical music, and, funnily enough, “prominent psychologists.” Subsequent children, on the other hand, were more likely to have supported the Protestant Reformation and the French Revolution.

There are so many assumptions, there’s so much research, and still there are very few hard conclusions to be drawn.

A friend, the eldest of four, presses into my hands a book that her mother claims to have been all the rage during the 1990s. The title is Brothers and Sisters: The Order of Birth in the Family , and it was written in the mid-20th century by the Viennese pediatrician and anthroposophist Karl König.

What strikes me from the very first pages is the certainty with which König characterizes first, second and third children. For example, he quotes a study that found firstborns to be “more likely to be serious, sensitive,” “conscientious,” and “good” and—this is my favorite—“fond of books.” Later on, these firstborns can become “shy, even fearful,” or they become “self-reliant, independent.” A second child, by contrast, is “placid, easy-going, friendly [and] cheerful”—unless they are “stubborn, rebellious, independent (or apparently so)” and “able to take a lot of punishment.” These typologies most resemble horoscopes, in the sense that it can’t be very hard to recognize yourself – or your children – at least partially in any of them.

By now, studies looking into the birth-order effect number in the thousands. There’s no shortage of popular publications either: titles such as Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives and Birth Order Blues: How Parents Can Help Their Children Meet the Challenges of Birth Order have helped spread the idea that your place in the family determines who you are.

In 2003, two U.S. and two Polish psychologists asked hundreds of participants what they knew about birth order. The majority of respondents were convinced that those born earlier had a greater chance of a prestigious career than those born later, and that those different career opportunities had to do with their specific birth-order-related character traits.

In sum, a century after the possible existence of the birth-order effect was first proposed, it had become common knowledge. That knowledge is now so common, in fact, that it lends itself to satire: “Study Shows Eldest Children Are Intolerable Wankers,” a headline on a Dutch satirical news website quipped in 2018.

Read more: I Was Constantly Arguing With My Child. Then I Learned the “TEAM” Method of Calmer Parenting

There is, however, plenty of criticism of birth-order theories and the associated empirical research. It’s not at all straightforward, critics point out, to know what you’re measuring when you try to unravel the factors that shape an individual human life. It’s also very hard to exclude all the “noise,” as physicists in a laboratory would be able to do more easily. This means that traits we might attribute to a person’s birth order may in fact have more to do with, say, socioeconomic status, the size or ethnicity of the family, or the values of a particular culture.

In the early 1990s, a group of political scientists observed with barely concealed exasperation that birth order had been “linked to a truly staggering range of behaviors.” They tried to debunk the myth that even a person’s political preferences were determined by their position in the family by reviewing studies that addressed, among other things, whether firstborns had “an uncommon tendency to enter into political careers,” were more conservative than those born later, and were more likely to hold political office. Their meta-analysis failed to find consistent patterns—but did find myriad methodological flaws.

There are so many assumptions, there’s so much research, and still there are very few hard conclusions to be drawn, although I suppose the latter is often the case, in the social sciences. They tend to provide more nuance rather than painting things in black and white— and rightly so.

Still, I’d like to know if there’s a counterargument to be made, in response to the certainty with which a friend remarks that second children are always “much more chill” than first children. Or to the way a family member takes it for granted that our son, independent and sociable as he is, is a “typical second child.”

Most Popular from TIME

The end of 2015 saw the publication of two studies in which the methodological shortcomings of previous birth-order research (unrepresentative sample sets, incorrect inferences) were largely obviated. In one of these studies, two U.S. psychologists analyzed data about the personality traits and family position of 377,000 secondary-school pupils in the United States. They did find associations between birth order and personality, but besides being so tiny as to be “statistically significant but meaningless,” as one of the researchers formulated it, they also partially ran counter to those predicted by the prevailing theories. For instance, firstborn children in this data set might be a little more cautious, but they were also less neurotic than later-born children.

The other study looked for associations between personality and birth order in data from the United States, Britain and Germany for a total of more than 20,000 people, comparing children from different families as well as siblings from the same family and correcting for factors such as family size and age. Here, the researchers found no relationship between a person’s place in the family and any personality trait whatsoever.

Other recent studies, conducted mostly by economists, do find an association between birth order and IQ: on average, firstborns score slightly higher on IQ-tests – they also tend to get more schooling. This may be due, researchers speculate, to the fact that parents are able to devote more undivided time and attention to their firstborns when they are very small. It’s an effect that has less to do with innate characteristics and more with parental treatment.

For me, it feels as if my children have been given a little extra wiggle room, a more level playing field. Whoever my son is or will become, his personality has not, or in any case not only, been determined by the coincidental fact of his having arrived second. My relief is conditional, of course—science has a tendency to change its mind.

Even so, the authors of one of those 2015 studies cherish little hope of ridding the world of the belief that birth order determines personality. After all, they wrote in an accompanying piece, it takes forever for academic insights to trickle down to the general public. And we tend to be swayed less by scientific results than by our own personal experiences.

My second child is quicker to anger, I once told another mother in a parenting course. But hadn’t my daughter been just as irascible when she was my son’s age?

One of the reasons belief in the birth-order effect is so persistent, they suggest, is because it’s so easily confused with age. Pretty much everyone can see with their own eyes that older children behave differently from younger children. And there’s a good chance that a first child, when compared with a second child, will appear more cautious and anxious. It’s just that this difference probably has more to do with age than with birth order.

My second child is quicker to anger, I once told another mother in a parenting course. But hadn’t my daughter been just as irascible when she was my son’s age? I’d described my son, who was almost 2 years old at the time, as more emotionally stable. Perhaps what I’d meant is that I can easily discern his emotions: they’re still so close to the surface. He sulks when something doesn’t go his way, bows his head and looks askance when he’s doing something he knows he shouldn’t, throws everything within reach on the floor when he’s angry. When he’s excited, he wags—it doesn’t matter that he lacks a tail. His sister’s feelings have already grown more subtle and complex, and the way they’re expressed has become hard to read, for her own 5-year old self as well as for me.

That difference in age might also be the reason that children from the same family are often assigned specific roles, a Dutch developmental psychologist tells me when I present her with the hypothesis of the two U.S. researchers. That way, even if there are no fixed differences in personality , we might still impose differences in behavior . Parents tell the eldest to be responsible, and the youngest to listen to the eldest. The behavior that follows from this is an expression of that role, not of a person’s character.

I think of the way we tried to prepare my daughter for the arrival of her little brother. How we told her that soon there would be someone who couldn’t do anything at all. She’d be able to explain everything to him, we’d said, because she already knew so much. The prospect had appealed to her. Little did we know we were talking her into a stereotype-perpetuating role.

Of course, all the circumstances in which a child comes into the world—whether they’re born male or female, in war or peace, into relative poverty or exorbitant wealth—end up making a person who they are. But the birth-order effect seems to particularly enthuse and preoccupy us.

Perhaps because it’s so concrete: it’s rather more fun and more satisfying to attribute a baby’s generous smile to the fact that he’s a second child than to a vague interplay of personality and environment, expectations and discernment.

And perhaps that’s also what makes it so tempting to attribute the effect to ourselves. It absolves us for a moment of the responsibility for who we are and the duty to turn ourselves into who we want to become: my being neurotic isn’t my fault, it’s just because I’m the eldest.

My son began to dole out little smiles when he was barely 4 weeks old. They were not just twitches or reflexes, I knew for sure, but outright attempts at contact. He began smiling earlier than his sister had, and this made sense to me: he was the second child, and so the more sociable one, just like my own sister.

It didn’t occur to me in that moment that my interpretation of his smile was founded on stories we’d been passing on for generations. It’s only now that I’m beginning to understand that those stories have a history. And that, without us really realizing it, they might shape our children’s present as well as their future.

Excerpted from Second Thoughts: On Having and Being a Second Child by Lynn Berger. Published by Henry Holt and Company, April 20th 2021. Copyright © 2020 by Lynn Berger English translation copyright © 2020 Anna Asbury. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Birth Order

Introduction, general overviews.

- Parental Investment

- Sibling Niche Theory

- Methodological Issues and Research Design

- Politics and the Life Sciences Controversy: Agendas and Methodology

- Birth Order Stereotypes

- Personality

- Family Dynamics

- Friendship and Cooperation

- Sexual/Romantic Relationships

- Sexual Orientation and the Fraternal Birth Order Effect

- Intelligence

- Challenges to Confluence Theory of Intelligence

- Theory of Mind/Cognitive Skills

- The Workplace

- Religion and Politics

- Risk-Taking

- Consumer Behavior

- Mental and Physical Health

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Personality Psychology

- Twin Studies

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Remote Work

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Birth Order by Catherine Salmon LAST REVIEWED: 28 May 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 29 October 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0103

Birth order, defined as an individual’s rank by age among siblings, has long been of interest to psychologists as well as lay-people. Much of the fascination has focused on the possible role of birth order in shaping personality and behavior. Many decades ago, Alfred Adler, a contemporary of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, suggested that personality traits are related to a person’s ordinal position within the family. He claimed that firstborns, once the sole focus of parental attention and resources, would be resentful when attention shifted upon the birth of the next child, and that this would result in neuroticism and possible substance abuse. In his view, lastborns would be spoiled and emotionally immature, while middle children would be the most stable, as they never experienced dethronement or being spoiled. Adler’s work led to an explosion of birth order studies examining the relationships between birth order and pretty much any topic one can think of, from personality traits to psychiatric disorders, intelligence, creativity, and sexual orientation. Not all of the research employed controls for other relevant factors, a number of hard-hitting critiques of the field were made, and the number of studies being done waned. Currently, the common view is that genetic differences account for a substantial portion (around 40 percent) of the variance in personality, for example, but that a similar amount of variance (around 35 percent) is due to non-shared environment, while the remainder is due to shared environment and measurement error. Birth order is one part of the non-shared environment. Siblings may grow up in the same family, but they do not all experience that family environment in the same way. Recently, researchers have suggested that birth order shapes strategies for dealing with the family environment, some of which may manifest themselves in settings outside the family domain. The first section of this article introduces general overviews or reviews of the birth order literature as well as some general theoretical perspectives and aspects of the debate over the important of birth order effects. The remaining sections examine the research in various areas where birth order has been well studied.

A wide variety of articles and books provide insight into the theoretical perspectives on birth order as well as reviewing portions of the field. Birth order research touches on many somewhat specialized areas of psychology; for example, cognition, child and lifespan development, social, and personality psychology, and reviews typically focus on just one specific aspect, most frequently personality. Research can be largely atheoretical or may come from an Adlerian perspective or a Darwinian one. There are a number of books and reviews that challenge the impact of birth order, including Harris 1998 , and just as many that argue for strong effects, such as Sulloway 1996 and Sulloway 2010 . Those interested in mastering the birth order literature have a lot of reading ahead of them; thousands of articles have been published. But the articles and books included here will acquaint the reader with the major debates within the field and will highlight the most consistent of findings (and the least). The narrative review of Schooler 1972 provides evidence that the impact of birth order is overstated, while Ernst and Angst 1983 is a well known review of the birth order literature from the 1940s to 1980 that suggests that birth order does not influence personality. Many of the studies it references later became part of Sulloway’s meta-analysis. Plomin, et al. 2001 revisits the role of non-shared environment in answering the question of why siblings are so different from each other with a behavioral genetics influence. Eckstein 2000 and Eckstein, et al. 2010 are influenced by the Adlerian perspective and focus mainly on studies that providence evidence for birth order differences in personality traits.

Eckstein, D. 2000. Empirical studies indicating significant birth-order related personality differences. Journal of Individual Psychology 56:481–494.

A review of studies, largely published between 1960 and 1999, that provides support for birth order differences in personality. Includes studies that relate to traits of firstborns, middleborns, lastborns, and only children. Shows the range of study topics from conformity to narcissism. Illustrates greater research focus on firstborns historically.

Eckstein, D., K. J. Aycock, M. A. Sperber, et al. 2010. A review of 200 birth-order studies: Lifestyle characteristics . Journal of Individual Psychology 66:408–434.

Gives Adlerian perspective and reviews Sulloway and his critics. Provides tables of characteristics by birth order (first/middle/last/only) and the statistically significant related studies from 1960–2010. Does not address non-significant study results, but an otherwise comprehensive reference.

Ernst, C., and J. Angst. 1983. Birth order: Its influence on personality . New York: Springer.

Extensive review of birth order literature from 1946 to 1980. Concludes that effects are the result of poor research design, in particular failure to control for family size and socioeconomic status. Suggests that effects are found more often in studies that fail to control and are not found in ones with proper controls. The meta-analysis of Sulloway 1996 was a statistical counter to this paper.

Harris, J. R. 1998. The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do . New York: Free Press.

Argues that genes and peers shape personality more than parents (and by extension birth order) do and that, while parental love and attention are not distributed evenly and siblings do compete, these experiences do not translate into their relationships with non-kin. Focuses more on peers and socialization.

Plomin, R., K. Asbury, P. G. Dip, and J. Dunn. 2001. Why are children in the same family so different? Non-shared environment a decade later. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46:225–233.

Behavioral genetics approach considers what aspects make up non-shared environment for siblings (parental favoritism, peers, interaction between genetics and environment). Plomin is one of first to highlight this question. Calls for more research and for consideration of role of chance. Available online for purchase or by subscription.

Schooler, C. 1972. Birth order effects: Not here, not now. Psychological Bulletin 78:161–175.

DOI: 10.1037/h0033026

Early narrative review of the literature on “normal” and psychiatric populations. Raises family size issues. No discussion of issues involved with using self-report of parental treatment of offspring. Studies are largely confined to comparing firstborns to lastborns or laterborns (everyone but firstborns), which is another issue not discussed (see Methodological Issues and Research Design ). Available online for purchase or by subscription.

Sulloway, F. J. 1996. Born to rebel: Birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives . New York: Pantheon.

Makes solid case for Darwinian theoretical approach to birth order focusing on differential parental investment and sibling competition. Documents personality differences and how they play out in terms of revolutions in science, religion, and politics. Highlights the rebellious role of the laterborn child.

Sulloway, F. J. 2010. Why siblings are like Darwin’s finches: Birth order, sibling competition, and adaptive divergence within the family. In The Evolution of Personality and Individual Differences . Edited by D. M. Buss and P. H. Hawley, 86–119. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195372090.001.0001

Darwinian approach to birth order, personality divergence among siblings due to differential parental investment and sibling conflict. Focus on sibling niche picking and that sibling divergence is an adaptive strategy. Covers wide range of studies in review.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abnormal Psychology

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Authoritarian Personality

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Birth Order

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Critical Thinking

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forensic Psychology

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- Heuristics and Biases

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making