Psychology Memory Revision Notes

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What do the examiners look for?

- Accurate and detailed knowledge

- Clear, coherent, and focused answers

- Effective use of terminology (use the “technical terms”)

In application questions, examiners look for “effective application to the scenario,” which means that you need to describe the theory and explain the scenario using the theory making the links between the two very clear. If there is more than one individual in the scenario you must mention all of the characters to get to the top band.

Difference between AS and A level answers

The descriptions follow the same criteria; however, you have to use the issues and debates effectively in your answers. “Effectively” means that it needs to be clearly linked and explained in the context of the answer.

Read the model answers to get a clearer idea of what is needed.

The Multi-Store Model

The multistore model of memory was proposed by Atkinson and Shiffrin and is a structural model. They proposed that memory consisted of three stores: sensory register, short-term memory (STM), and long-term memory (LTM). Information passes from store to store in a linear way. Both STM and LTM are unitary stores.

Sensory memory is the information you get from your sense, your eyes, and ears. When attention is paid to something in the environment, it is then converted to short-term memory.

Information from short-term memory is transferred to long-term memory only if that information is rehearsed (i.e., repeated).

Maintenance rehearsal is repetition that keeps information in STM, but eventually, such repetition will create an LTM.

If maintenance rehearsal (repetition) does not occur, then information is forgotten and lost from short-term memory through the processes of displacement or decay.

Each store has its own characteristics in terms of encoding, capacity, and duration .

- Encoding is the way information is changed so that it can be stored in memory. There are three main ways in which information can be encoded (changed): 1. visual (picture), 2. acoustic (sound), and 3. semantic (meaning).

- Capacity concerns how much information can be stored.

- Duration refers to the period of time information can last in-memory stores.

Sensory register

- Duration: ¼ to ½ second

- Capacity: all sensory experience (v. larger capacity)

- Encoding: sense specific (e.g., different stores for each sense)

Short Term Memory

- Duration: 0-18 seconds

- Capacity: 7 +/- 2 items

- Encoding: mainly acoustic

Long Term Memory

- Duration: Unlimited

- Capacity: Unlimited

- Encoding: Mainly semantic (but can be visual and acoustic)

AO2 Scenario Question

The multi-store model of memory has been criticized in many ways. The following example illustrates a possible criticism.

Some students read through their revision notes lots of times before an examination but still, find it difficult to remember the information. However, the same students can remember the information in a celebrity magazine, even though they read it only once.

Explain why this can be used as a criticism of the multi-store model of memory.

“The MSM states that depth of memory trace in LTM is simply a result of the amount of rehearsal that takes place.

The MSM can be criticized for failing to account for how different types of material can result in different depth memory traces even though they’ve both been rehearsed for a similar amount of time.

For example, people may recall information they are interested in (e.g., information in celebrity magazines) more than the material they are not interested in (e.g., revision notes) despite the fact that they have both been rehearsed for a similar amount of time.

Therefore, the MSM’s view of long-term memory can be criticized for failing to take into account that material we may pay more attention to or is more meaningful/interesting to us may cause a deeper memory trace which is recalled more easily.”

One strength of the multistore model is that it gives us a good understanding of the structure and process of the STM. This is good because this allows researchers to expand on this model. This means researchers can do experiments to improve on this model and make it more valid, and they can prove what the stores actually do.

The model is supported by studies of amnesiacs: For example the patient H.M. case study. HM is still alive but has marked problems in long-term memory after brain surgery.

He has remembered little of personal (death of mother and father) or public events (Watergate, Vietnam War) that have occurred over the last 45 years. However, his short-term memory remains intact.

It has now become apparent that both short-term and long-term memory is more complicated than previously thought. For example, the Working Model of Memory proposed by Baddeley and Hitch (1974) showed that short-term memory is more than just one simple unitary store and comprises different components (e.g., central executive, Visuospatial, etc.).

The model suggests rehearsal helps to transfer information into LTM, but this is not essential. Why are we able to recall information which we did not rehearse (e.g., swimming) yet unable to recall information which we have rehearsed (e.g., reading your notes while revising)?

Therefore, the role of rehearsal as a means of transferring from STM to LTM is much less important than Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968) claimed in their model.

Research Study for both STM & LTM

Research studies can either be knowledge or evaluation:

- If you refer to the procedures and findings of a study, this shows knowledge and understanding (AO1).

- If you comment on what the studies show and what it supports and challenges the theory in question, this shows evaluation (AO3).

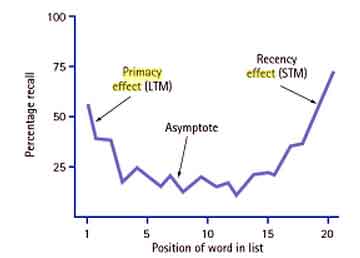

Glanzer and Cunitz showed that when participants are presented with a list of words, they tend to remember the first few and last few words and are more likely to forget those in the middle of the list, i.e., the serial position effect.

This supports the existence of separate LTM and STM stores because they observed a primacy and recency effect.

Words early on in the list were put into long-term memory (primacy effect) because the person has time to rehearse the word, and words from the end went into short-term memory (recency effect).

Other compelling evidence to support this distinction between STM and LTM is the case of KF (Shallice & Warrington, 1970), who had been in a motorcycle crash where he had sustained brain damage. His LTM seemed to be unaffected, but he was only able to recall the last bit of information he had heard in his STM.

Types of Long-Term Memory

One of the earliest and most influential distinctions of long-term memory was proposed by Tulving (1972). He proposed a distinction between episodic, semantic, and procedural memory.

Procedural Memory

Procedural memory is a part of the implicit long-term memory responsible for knowing how to do things, i.e., a memory of motor skills. A part of long-term memory is responsible for knowing how to do things, i.e., the memory of motor skills. It does not involve conscious (i.e., it’s unconscious-automatic) thought and is not declarative.

For example, procedural memory would involve knowledge of how to ride a bicycle.

Semantic Memory

Episodic memory.

Episodic memory is a part of the long-term memory responsible for storing information about events (i.e., episodes) that we have experienced in our lives.

It involves conscious thought and is declarative. An example would be a memory of our 1st day at school.

Cohen and Squire (1980) drew a distinction between declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge . Procedural knowledge involves “knowing how” to do things. It included skills such as “knowing how” to play the piano, ride a bike, tie your shoes, and other motor skills.

It does not involve conscious thought (i.e., it’s unconscious-automatic). For example, we brush our teeth with little or no awareness of the skills involved.

Whereas declarative knowledge involves “knowing that”; for example, London is the capital of England, zebras are animals, your mum’s birthday, etc. Recalling information from declarative memory involves some degree of conscious effort – information is consciously brought to mind and “declared.”

The knowledge that we hold in semantic and episodic memories focuses on “knowing that” something is the case (i.e., declarative). For example, we might have a semantic memory for knowing that Paris is the capital of France, and we might have an episodic memory for knowing that we caught the bus to college today.

Evidence for the distinction between declarative and procedural memory has come from research on patients with amnesia . Typically, amnesic patients have great difficulty in retaining episodic and semantic information following the onset of amnesia.

Their memory for events and knowledge acquired before the onset of the condition tends to remain intact, but they can’t store new episodic or semantic memories. In other words, it appears that their ability to retain declarative information is impaired.

However, their procedural memory appears to be largely unaffected. They can recall skills they have already learned (e.g., riding a bike) and acquire new skills (e.g., learning to drive).

Working Memory Model

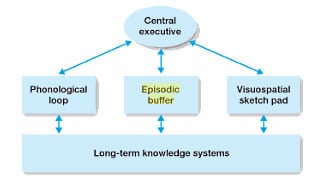

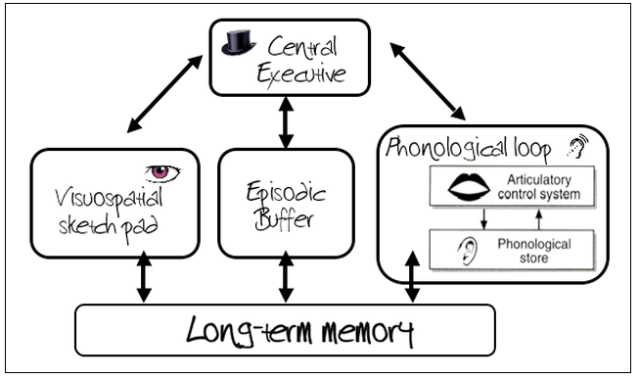

The working memory model (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974) replaced the idea of a unitary STM. It suggests a system involving active processing and short-term storage of information.

Key features include the central executive, the phonological loop, and the visuospatial sketchpad.

The central executive has a supervisory function and acts as a filter, determining which information is attended to.

It can process information in all sensory forms, direct information to other slave systems, and collects responses. It has limited capacity and deals with only one piece of information at a time.

One of the slave systems is the phonological loop which is a temporary storage system for holding auditory information in a speech-based form.

It has two parts: (1) the phonological store (inner ear), which stores words you hear; and (2) the articulatory process (inner voice), which allows maintenance rehearsal (repeating sounds or words to keep them in working memory while they are needed). The phonological loop plays a key role in the development of reading.

The second slave system is the Visuospatial sketchpad (VSS). The VSS is a temporary memory system for holding visual and spatial information. It has two parts: (1) the visual cache (which stores visual data about form and color) and (2) the inner scribe (which records the arrangement of objects in the visual field and rehearses and transfers information in the visual cache to the central executive).

The third slave system is the episodic buffer which acts as a “backup” (temporary) store for information that communicates with both long-term memory and the slave system components of working memory. One of its important functions is to recall material from LTM and integrate it into STM when working memory requires it.

Bryan has been driving for five years. Whilst driving, Bryan can hold conversations or listen to music with little difficulty.

Bob has had four driving lessons. Driving requires so much of Bob’s concentration that, during lessons, he often misses what his driving instructor is telling him. With reference to features of the working memory model, explain the different experiences of Bryan and Bob. (4 marks)

A tricky question – the answer lies in Bryan being able to divide the different components of his STM because he is experienced at driving and doesn’t need to devote all his attention to the task of driving (controlled by the visuospatial sketchpad).

“Because Bryan has been driving for five years it is an ‘automated’ task for him; it makes fewer attentional demands on his central executive, so he is free to perform other tasks (such as talking or listening to music) and thus is able to divide resources between his visuospatial sketch pad (driving) and phonological loop (talking and listening to music).

As Bob is inexperienced at driving, this is not the case for him – his central executive requires all of his attentional capacity for driving and thus cannot divide resources effectively between components of working memory.”

Working memory is supported by dual-task studies. It is easier to do two tasks at the same time if they use different processing systems (verbal and visual) than if they use the same slave system.

For example, participants would find it hard to do two visual tasks at the same time because they would be competing for the same limited resources of the visuospatial sketchpad. However, a visual task and a verbal task would use different components and so could be performed with minimum errors.

The KF Case Study supports the Working Memory Model. KF suffered brain damage from a motorcycle accident that damaged his short-term memory. KF’s impairment was mainly for verbal information – his memory for visual information was largely unaffected.

This shows that there are separate STM components for visual information (VSS) and verbal information (phonological loop). However, evidence from brain-damaged patients may not be reliable because it concerns unique cases with patients who have had traumatic experiences.

One limitation is the fact that little is known about how the central executive works. It is an important part of the model, but its exact role is unclear.

Another limitation is that the model does not explain the link between working memory and LTM.

Research Study for WM

- If you refer to the procedures and findings of a study, this shows knowledge and understanding.

- If you comment on what the studies show and what it supports and challenges the theory in question, this shows evaluation.

Baddeley and Hitch conducted an experiment in which participants were asked to perform two tasks at the same time (dual task technique). A digit span task required them to repeat a list of numbers, and a verbal reasoning task which required them to answer true or false to various questions (e.g., B is followed by A?).

Results : As the number of digits increased in the digit span tasks, participants took longer to answer the reasoning questions, but not much longer – only fractions of a second. And they didn’t make any more errors in the verbal reasoning tasks as the number of digits increased.

Conclusion : The verbal reasoning task made use of the central executive, and the digit span task made use of the phonological loop.

Explanations for Forgetting

Interference.

Interference is an explanation for forgetting from long-term memory – two sets of information become confused.

- Proactive interference (pro=forward) is where old learning prevents the recall of more recent information. When what we already know interferes with what we are currently learning – where old memories disrupt new memories.

- Retroactive interference (retro=backward) is where new learning prevents the recall of previously learned information. In other words, later learning interferes with earlier learning – where new memories disrupt old memories.

Proactive and retroactive Interference is thought to be more likely to occur where the memories are similar, for example: confusing old and new telephone numbers. Chandler (1989) stated that students who study similar subjects at the same time often experience interference. French and Spanish are similar types of material which makes interference more likely.

Semantic memory is more resistant to interference than other types of memory.

Postman (1960) provides evidence to support the interference theory of forgetting. A lab experiment was used, and participants were split into two groups. Both groups had to remember a list of paired words – e.g., cat – tree, jelly – moss, book – tractor.

The experimental group also had to learn another list of words where the second paired word is different – e.g., cat – glass, jelly- time, book – revolver. The control group was not given the second list.

All participants were asked to recall the words on the first list. The recall of the control group was more accurate than that of the experimental group. This suggests that learning items in the second list interfered with participants’ ability to recall the list. This is an example of retroactive interference.

Although proactive and retroactive interference is reliable and robust effects, there are a number of problems with interference theory as an explanation for forgetting.

First, interference theory tells us little about the cognitive processes involved in forgetting. Secondly, the majority of research into the role of interference in forgetting has been carried out in a laboratory using lists of words, a situation that is likely to occur fairly infrequently in everyday life (i.e., low ecological validity). As a result, it may not be possible to generalize from the findings.

Baddeley states that the tasks given to subjects are too close to each other and, in real life; these kinds of events are more spaced out. Nevertheless, recent research has attempted to address this by investigating “real-life” events and has provided support for interference theory. However, there is no doubt that interference plays a role in forgetting, but how much forgetting can be attributed to interference remains unclear.

Retrieval failure

Retrieval failure is where information is available in long-term memory but cannot be recalled because of the absence of appropriate cues.

When we store a new memory, we also store information about the situation and these are known as retrieval cues. When we come into the same situation again, these retrieval cues can trigger the memory of the situation.

Types of cues that have been studied by psychologists include context, state, and organization.

- Context – external cues in the environment, e.g., smell, place, etc. Evidence indicates that retrieval is more likely when the context at encoding matches the context at retrieval.

- State – bodily cues inside of us, e.g., physical, emotional, mood, drunk, etc. The basic idea behind state-dependent retrieval is that memory will be best when a person’s physical or psychological state is similar to encoding and retrieval.

For example, if someone tells you a joke on Saturday night after a few drinks, you”ll be more likely to remember it when you”re in a similar state – at a later date after a few more drinks. Stone cold sober on Monday morning, you”ll be more likely to forget the joke.

- Organization – Recall is improved if the organization gives a structure that provides triggers, e.g., categories.

According to retrieval-failure theory, forgetting occurs when information is available in LTM but is not accessible. Accessibility depends in large part on retrieval cues.

Forgetting is greatest when context and state are very different at encoding and retrieval. In this situation, retrieval cues are absent, and the likely result is cue-dependent forgetting.

Evaluation (AO3)

People tend to remember material better when there is a match between their mood at learning and at retrieval. The effects are stronger when the participants are in a positive mood than when they are in a negative mood. They are also greater when people try to remember events having personal relevance.

A number of experiments have indicated the importance of context-based (i.e., external) cues for retrieval. An interesting experiment conducted by Baddeley indicates the importance of context setting for retrieval.

Baddeley (1975) asked deep-sea divers to memorize a list of words. One group did this on the beach, and the other group underwater. When they were asked to remember the words, half of the beach learners remained on the beach, and the rest had to recall underwater.

Half of the underwater group remained there, and the others had to recall on the beach. The results show that those who had recalled in the same environment (i.e., context) and who had learned recalled 40% more words than those recalling in a different environment. This suggests that the retrieval of information is improved if it occurs in the context in which it was learned.

A study by Goodwin investigated the effect of alcohol on state-dependent (internal) retrieval. They found that when people encoded information when drunk, they were more likely to recall it in the same state.

For example, when they hid money and alcohol when drunk, they were unlikely to find them when sober. However, when they were drunk again, they often discovered the hiding place. Other studies found similar state-dependent effects when participants were given drugs such as marijuana.

The ecological validity of these experiments can be questioned, but their findings are supported by evidence from outside the laboratory. For example, many people say they can’t remember much about their childhood or their school days. But returning to the house in which they spent their childhood or attending a school reunion often provides retrieval cues that trigger a flood of memories.

Eyewitness Testimony

Misleading information.

Loftus and Palmer investigated how misleading information could distort eyewitness testimony accounts.

Procedure : Forty-five American students formed an opportunity sample. This was a laboratory experiment with five conditions, only one of which was experienced by each participant (an independent measures experimental design ).

Participants were shown slides of a car accident involving a number of cars and asked to describe what had happened as if they were eyewitnesses. They were then asked specific questions, including the question, “About how fast were the cars going when they (hit/smashed/collided/bumped/contacted ) each other?”

Findings : The estimated speed was affected by the verb used. The verb implied information about the speed, which systematically affected the participants’ memory of the accident.

Participants who were asked the “smashed” question thought the cars were going faster than those who were asked the “hit” question. The participants in the “smashed” condition reported the highest speeds, followed by “collided,” “bumped,” “hit,” and “contacted” in descending order.

The research lacks mundane realism, as the video clip does not have the same emotional impact as witnessing a real-life accident, and so the research lacks ecological validity.

A further problem with the study was the use of students as participants. Students are not representative of the general population in a number of ways. Importantly they may be less experienced drivers and, therefore, less confident in their ability to estimate speeds. This may have influenced them to be more swayed by the verb in the question.

A strength of the study is it’s easy to replicate (i.e., copy). This is because the method was a laboratory experiment that followed a standardized procedure.

The Yerkes-Dodson effect states that when anxiety is at low and high levels, EWT is less accurate than if anxiety is at a medium level. Recall improves as anxiety increases up to an optimal point and then declines.

When we are in a state of anxiety, we tend to focus on whatever is making us feel anxious or fearful, and we exclude other information about the situation. If a weapon is used to threaten a victim, their attention is likely to focus on it. Consequently, their recall of other information is likely to be poor.

Clifford and Scott (1978) found that people who saw a film of a violent attack remembered fewer of the 40 items of information about the event than a control group who saw a less stressful version. As witnessing a real crime is probably more stressful than taking part in an experiment, memory accuracy may well be even more affected in real life.

However, a study by Yuille and Cutshall (1986) contradicts the importance of stress in influencing eyewitness memory. Twenty-one witnesses observed a shooting incident in Canada outside a gun shop in which one person was killed and a 2nd seriously wounded. The incident took place on a major thoroughfare in the mid-afternoon.

All of the witnesses were interviewed by the investigating police, and 13 witnesses (aged 15-32 yrs) agreed to a research interview 4-5 months after the event. The witnesses were also asked to rate how stressed they had felt at the time of the incident using a 7-point scale. The eyewitness accounts provided in both the police and research interviews were analyzed and compared.

The results of the study showed the witnesses were highly accurate in their accounts, and there was little change in the amount or accuracy of recall after five months. The study also showed that stress levels did not have an effect on memory, contrary to lab findings.

All participants showed high levels of accuracy, indicating that stress had little effect on accuracy. However, very high anxiety was linked to better accuracy. Participants who reported the highest levels of stress were most accurate (about 88% accurate compared to 75% for the less-stressed group).

One strength of this study is that it had high ecological validity compared with lab studies which tend to control variables and use student populations as research participants.

One weakness of this study was that there was an extraneous variable. The witnesses who experienced the highest levels of stress were actually closer to the event (the shooting), and this may have helped with the accuracy of their memory recall.

Reduced accuracy of information may be due to surprise rather than anxiety – Pickel found that identification was least accurate in high surprise conditions rather than high threat conditions – The weapon focus effect may be related to surprise rather than anxiety; therefore, research may lack internal validity.

Real-world application: We can apply the Yerkes-Dodson effect to predict that stressful incidents will lead to witnesses having relatively inaccurate memories as their anxiety levels would be above the optimum – We can avoid an over-reliance on eyewitness testimony that may have been impacted by anxiety.

The Cognitive Interview

The cognitive interview is a police technique for interviewing witnesses to a crime which encourages them to recreate the original context in order to increase the accessibility of stored information.

The cognitive interview involves a number of techniques:

Context Reinstatement

Trying to mentally recreate an image of the situation, including details of the environment, such as the weather conditions, and the individual’s emotional state, including their feelings at the time of the incident. This makes memories accessible and provides emotional and contextual cues.

Recall from a Changed Perspective

Recall in reverse order, report everything.

The interviewer encourages the witness to report all details about the event, even though these details may seem unimportant. Memories are interconnected so that recollection of one item may then cue a whole lot of other memories.

The Enhanced Cognitive Interview

The main additional features are:-

- Encourage the witness to relax and speak slowly.

- Offer comments to help clarify witness statements.

- Adapt questions to suit the understanding of individual witnesses.

One limitation is the cognitive interview is that it’s time-consuming to conduct and takes much longer than a standard police interview. It is also time-consuming to train police officers to use this method. This means that it is unlikely that the “proper” version of the cognitive interview is used.

Another limitation is that some elements of the cognitive interview may be more valuable than others. For example, research has shown that using a combination of “report everything” and “context reinstatement” produced better recall than any of the conditions individually.

A final criticism is that police personnel have to be trained, and this can be expensive and time-consuming.

Geiselman (1985) set out to investigate the effectiveness of the cognitive interview. Participants viewed a film of a violent crime and, after 48 hours, were interviewed by a policeman using one of three methods: the cognitive interview, a standard interview used by the Los Angeles Police, or an interview using hypnosis.

The number of facts accurately recalled and the number of errors made was recorded. The average number of correctly recalled facts for the cognitive interview was 41.2. For hypnosis, it was 38.0, and for the standard interview, it was 29.4.

A-Level Psychology Revision Notes

A-Level Psychology Attachment

Social Influence Revision Notes

Psychopathology Revision Notes

Psychology Approaches Revision for A-level

Research Methods: Definition, Types, & Examples

Issues and Debates in Psychology (A-Level Revision)

Related Articles

A-Level Psychology

A-level Psychology AQA Revision Notes

Aggression Psychology Revision Notes

Relationship Theories Revision Notes

Addiction in Psychology: Revision Notes for A-level Psychology

- Reads Reads 6,257 6,257 6.2K

- Votes Votes 479 479 479

- Parts Parts 15 15 15

- characterstudy

- genshinimpact

- Premessa Sun, Feb 19, 2023

- Capitolo Uno Sun, Feb 19, 2023

- Capitolo Due Mon, Feb 20, 2023

- Capitolo Tre Tue, Feb 21, 2023

- Capitolo Quattro Wed, Feb 22, 2023

- Capitolo Cinque Thu, Feb 23, 2023

- Capitolo Sei Fri, Feb 24, 2023

- Capitolo Sette Fri, Feb 24, 2023

- Capitolo Otto Sat, Feb 25, 2023

- Capitolo Nove Sat, Feb 25, 2023

- Capitolo Dieci Sat, Feb 25, 2023

- Capitolo Undici Sat, Feb 25, 2023

- Capitolo Dodici Sun, Feb 26, 2023

- Capitolo Tredici Sun, Feb 26, 2023

- Note Finali Sun, Feb 26, 2023

Get notified when THE CASE STUDY OF THE SCRIBE, kavetham is updated

If you already have an account, Log in.

gli occhi// kenan yildiz

Perché ho gli occhi molto più cechi del cuore e non sono mai riuscita a vederci amore... rebecca chiesa, sorella di federico chiesa, affronta la sua nuova vita a torino. al suo fianco persone special....

The Working Memory Model, Baddeley And Hitch (1974)

March 5, 2021 - paper 1 introductory topics in psychology | memory.

Description, AO1 The Working Memory Model

Baddeley & Hitch’s (1974) Working Memory Model (WMM) arose out of criticisms aimed at the Multi-Store Model (MSM), particularly the idea that STM was a unitary store to test this Baddeley and Hitch devised the dual-task technique.

Research: D’Esposito et al found using MRI scans the prefrontal cortex was activated when verbal and spatial tasks were preformed simultaneously but not when performed separately, suggesting the brain area indicates the working of the CE.

(4) Episodic buffer:

(1) Point: There is physiological evidence to support the WMM: Evidence: For example, PET (positron emission tomography) scans have shown that different areas of the brain are used whilst undertaking visual and verbal tasks which may correspond to the visuo-spatial sketchpad and phonological loop of WMM. Evaluation: This is positive as it provides objective and scientific support for the view that visual and verbal material is dealt with by separate structures that may even be physically separate, this increases the credibility of the WMM as an accurate representation of memory.

(2) Point: Support for the working memory model comes from the case study of KF. Evidence: For example, KF suffered a motorcycle accident and was left with considerable damage to his memory. His short-term forgetting of auditory information was greater than for visual information, suggesting that his memory damage was restricted to the phonological loop. Evaluation: This is a strength because it demonstrates that it’s possible to damage just part of the short-term memory, which can be accounted for by the WMM, as if all short-term memories were stored in the same place KF’s entire STM would be damaged.

To learn about the alternative model of memory, The Multi-Store Model of memory, click here.

- Main Content

While we've done our best to make the core functionality of this site accessible without JavaScript, it will work better with it enabled. Please consider turning it on!

Archive of Our Own beta

Remember Me

- Forgot password?

- Get an Invitation

scribe’s fanfic library

Become an OTW member by June 30 to vote in the upcoming Board of Directors election !

- Subcollections (0)

- Fandoms (129)

- Works (519)

- Bookmarked Items (115)

- Random Items

scribe’s fanfic library > Fandoms

You can search this page by pressing ctrl F / cmd F and typing in what you are looking for.

All Media Types Anime & Manga Books & Literature Cartoons & Comics & Graphic Novels Celebrities & Real People Movies Music & Bands Other Media Theater TV Shows Video Games

Alphabet Navigation

Alphabetised list of fandoms.

- Addams Family - All Media Types (1)

- Assassination Classroom (1)

- Avatar: The Last Airbender (Cartoon 2005) (3)

- The Avengers (Marvel Movies) (3)

- Baldur's Gate (Video Games) (7)

- Batman - All Media Types (25)

- Batman: Wayne Family Adventures (Webcomic) (1)

- Biohazard | Resident Evil (Gameverse) (2)

- Bloodborne (Video Game) (1)

- 僕のヒーローアカデミア | Boku no Hero Academia | My Hero Academia (Anime & Manga) (7)

- 文豪ストレイドッグス | Bungou Stray Dogs (15)

- Camp Camp (Web Series) (1)

- Castlevania (Cartoon 2017-2021) (6)

- 悪魔城ドラキュラ | Castlevania (Video Games) (1)

- Check Please! (Webcomic) (1)

- Chronicles of Narnia - All Media Types (1)

- Chronicles of Narnia - C. S. Lewis (1)

- Constantine: The Hellblazer (Comics) (2)

- Control (Video Game) (1)

- Corpse Bride (2005) (1)

- Criminal Minds (US TV) (7)

- Critical Role (Web Series) (1)

- D.Gray-man (Anime & Manga) (4)

- Danny Phantom (84)

- DCU (Comics) (3)

- Dear Evan Hansen - Pasek & Paul/Levenson (2)

- Detroit: Become Human (Video Game) (1)

- Doctor Who (1)

- DreamWorks Dragons (Cartoon) (2)

- Durarara!! (7)

- The Eldest Curses Series - Cassandra Clare (1)

- Encanto (2021) (9)

- Fairy Tail (1)

- Father Brown - G. K. Chesterton (1)

- Fran Bow (Video Game) (1)

- Frankenstein - Mary Shelley (1)

- Fullmetal Alchemist - All Media Types (14)

- Fullmetal Alchemist (Anime 2003) (3)

- Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood & Manga (5)

- Game of Thrones (TV) (1)

- Good Omens - Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett (1)

- Good Omens (TV) (2)

- Gravity Falls (19)

- The Great Gatsby - F. Scott Fitzgerald (1)

- Haikyuu!! (8)

- Hannibal (TV) (2)

- Harry Potter - J. K. Rowling (34)

- Hazbin Hotel (Cartoon) (16)

- Helluva Boss (Web Series) (1)

- The Heroes of Olympus - Rick Riordan (1)

- Hetalia: Axis Powers (4)

- How to Train Your Dragon (Movies) (12)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Disney Animated Movies) (1)

- Hyrule Warriors: Age of Calamity (Video Game) (2)

- The Infernal Devices Series - Cassandra Clare (1)

- Inkheart (2008) (1)

- Invader Zim (2)

- Xi You Ji | Journey to the West - Wu Cheng'en (1)

- 西遊 | Journey to the West (Chow Movies 2013 2017) (1)

- Justice League - All Media Types (9)

- Klaus (2019) (1)

- 小林さんちのメイドラゴン | Kobayashi-san Chi no Maid Dragon | Miss Kobayashi's Dragon Maid (6)

- The Legend of Vox Machina (Cartoon) (1)

- The Legend of Zelda & Related Fandoms (5)

- The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild/Tears of the Kingdom (6)

- LEGO Monkie Kid (1)

- Lucifer (TV) (19)

- The Magnus Archives (Podcast) (9)

- Marvel Cinematic Universe (4)

- Megamind (2010) (1)

- Merlin (TV) (18)

- Miraculous Ladybug (83)

- The Mortal Instruments Series - Cassandra Clare (3)

- ナンバカ | Nanbaka (1)

- Natsume Yuujinchou | Natsume's Book of Friends (1)

- ノラガミ | Noragami (Anime & Manga) (1)

- The Old Guard (Movie 2020) (1)

- Over the Garden Wall (Cartoon & Comics) (5)

- The Owl House (Cartoon) (13)

- Pacific Rim (Movies) (1)

- Percy Jackson and the Olympians - Rick Riordan (2)

- Percy Jackson and the Olympians & Related Fandoms - All Media Types (5)

- Pocket Monsters | Pokemon - All Media Types (8)

- Pocket Monsters | Pokemon (Anime) (22)

- Pocket Monsters: Black & White | Pokemon Black and White Versions (1)

- Pocket Monsters: Diamond & Pearl & Platinum | Pokemon Diamond Pearl Platinum Versions (1)

- Pocket Monsters: Gold & Silver & Crystal | Pokemon Gold Silver Crystal Versions (1)

- Pocket Monsters: Red & Green & Blue & Yellow | Pokemon Red Green Blue Yellow Versions (1)

- Pocket Monsters: Ruby & Sapphire & Emerald | Pokemon Ruby Sapphire Emerald Versions (1)

- Pocket Monsters: Sun & Moon | Pokemon Sun & Moon Versions (5)

- Pocket Monsters: Ultra Sun & Ultra Moon | Pokemon Ultra Sun & Ultra Moon Versions (1)

- Pocket Monsters: X & Y | Pokemon X & Y Versions (1)

- Red Hood and the Outlaws (Comics) (1)

- Red Robin (Comics) (1)

- Rick and Morty (2)

- Rise of the Guardians (2012) (3)

- Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (Cartoon 2018) (4)

- 斉木楠雄のΨ難 | Saiki Kusuo no Sai-nan | The Disastrous Life of Saiki K. (2)

- Servamp (Anime & Manga) (1)

- The Shadowhunter Chronicles - All Media Types (10)

- The Shadowhunter Chronicles - Cassandra Clare (4)

- Shadowhunters (TV) (16)

- A Song of Ice and Fire - George R. R. Martin (1)

- A Song of Ice and Fire & Related Fandoms (1)

- South Park (1)

- Spider-Man - All Media Types (1)

- Spider-Man (Tom Holland Movies) (1)

- SPY x FAMILY (Anime) (5)

- SPY x FAMILY (Manga) (5)

- The Starless Sea - Erin Morgenstern (1)

- Supernatural (TV 2005) (3)

- Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy - Cassandra Clare (1)

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles - All Media Types (5)

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (TV 2003) (1)

- Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (TV 2012) (3)

- Tokyo Ghoul (7)

- Total Drama (Cartoon) (1)

- Twilight Series - All Media Types (1)

- Twilight Series - Stephenie Meyer (1)

- The Umbrella Academy (TV) (2)

- ヴァ二タスの手記 - 望月淳 | Vanitas no Carte | The Case Study of Vanitas - Mochizuki Jun (Manga) (3)

- Voltron: Legendary Defender (1)

- Welcome to Night Vale (2)

- White Collar (TV 2009) (1)

- Winternight Series - Katherine Arden (1)

- Young Justice - All Media Types (2)

- Young Justice (Cartoon) (5)

- Yuri!!! on Ice (Anime) (14)

About the Archive

- Diversity Statement

- Terms of Service

- DMCA Policy

- Policy Questions & Abuse Reports

- Technical Support & Feedback

Development

- otwarchive v0.9.370.6

- Known Issues

- GPL-2.0-or-later by the OTW

Case Study: Scribe

- First Online: 21 March 2019

Cite this chapter

- Megan Holstein 2

1204 Accesses

Scribe is an app that solved one very small but very serious problem for some people—copying and pasting between their Macs and iOS devices.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dublin, OH, USA

Megan Holstein

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Megan Holstein

About this chapter

Holstein, M. (2019). Case Study: Scribe. In: iPhone App Design for Entrepreneurs. Apress, Berkeley, CA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-4285-8_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-4285-8_8

Published : 21 March 2019

Publisher Name : Apress, Berkeley, CA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4842-4284-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4842-4285-8

eBook Packages : Professional and Applied Computing Apress Access Books Professional and Applied Computing (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Our Partners

- Annual Letters

- Adult Immunization Equity Initiative

- Colorado Health Innovation Community

- Connected Care Accelerator: Equity Collaborative

- Technology Hub

- Telehealth Improvement Community Fund

- Addiction Treatment Starts Here

- Advancing Behavioral Health Equity in Primary Care

- Amplify Healing Connections

- COVID-19 Test-to-Treat Equity Grant

- Resilient Beginnings

- Completed Programs

- CCI Academy

- Resource Center

- Get Involved

Case Study: Boosting Productivity with Medical Scribes

This case study was prepared by Kristene Cristobal of Cristobal Consulting, contracted evaluator for the Spreading Solutions That Work program.

When patients visit providers, the experience can be hampered by the use of the electronic health record, whether it’s difficult to use, time consuming, or hinders the clinical documentation process .

At the same time, primary care provider burnout is being driven by the demands of documentation, as clinicians spend extra hours each night writing notes instead of spending time with their families. The result in low satisfaction and high turnover .

Medical scribes are a promising way to help providers focus on their interactions with patients and increase joy in work . An estimated one in five practices with an electronic health record (EHR) currently use scribes .

La Clínica , a Federally Qualified Health Center located in the San Francisco Bay Area, has nineteen clinic sites and 140 providers. Like many community health centers, it struggles with a shrinking primary care workforce and an EHR that place a heavy clerical burden on providers, impacting productivity, patient access, and satisfaction.

To address challenges in delayed provider adoption of the EHR and other factors hampering computer use, La Clínica piloted two scribes working with ten providers. They targeted high-performing providers who were at risk for turnover.

Spreading Solutions That Work

In 2017, we selected 16 teams to participate in Spreading Solutions That Work , a year-long program in its fourth cycle. Teams implemented one of five solutions:

- Group Visits

- Medical Scribes

- Patient Portal Optimization

- Telephone Visits

- Texting Solutions

Medical scribes can be nurses, medical assistants, or other non-clinical staff who accompany providers in the patient visit to scribe notes in the electronic health record, enter orders, prepare the after-visit summary, and reinforce the plan with the patient.

Our support included a grant of $15,000, coaching, measurement support, peer group webinars, tools, and other resources. The team also trained at Shasta Community Health Center , which runs Scribe University, one of the few safety net programs of its kind. The three-day training allowed La Clinica to shadow Shasta’s scribe team and covered:

- How to take SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, and plan) notes

- What to include when writing a history of present illness

- Elements of a physical exam

- Practice writing notes

- Preparing clinicians for scribes

- Process for reviewing notes

Designing the Pilot

La Clínica found it important to focus on productivity from the beginning instead of waiting until the end of the pilot phase to evaluate its impact on it. The team approached providers who were already greatly exceeding productivity expectations or who could likely serve a greater number of patients if they worked with a scribe. This approach set out to reward productive providers, monitor productivity throughout implementation, and increase productivity.

The team told the providers, “We know you work hard and we’d like to make your day better and your experience better. We’ll need to see a bump up in productivity and with a well-trained scribe you will be able to see see two patients more per day and get out of the clinic on time.”

The calculation was that increasing provider productivity by two patients per day would offset the cost of hiring the scribe.

Incorporating Medical Scribes into a Successful Team

Tips from Shasta Community Health Center

- Understand there is a steep learning curve, as new scribes may have little medical background or medical experience. They are learning medical terminology, EHR navigation, and clinical workflow.

- The initial training period is approximately one month, but it can take two to three months to establishing a good flow between the provider and the scribe, if the provider can put in the time and give feedback and consistent communication.

- Reviewing notes with scribes is important for learning. Providers should spend 10-15 minutes at the end of a shift letting them know what went well, what they can work on, and how they prefer things to look in the notes.

- Providers should dictate physical exam findings while in the exam room. For example, let scribes know if the cardiovascular exam or respiratory exam is normal.

- Create customized quick saved templates or “my phrases” or “dot phrases” to improve efficiency and accuracy.

- Before entering exam room, talk to your scribe about preventative measures you might order and a brief history of the patient.

- Providers and scribes can set quality goals. For example, make sure every eligible female has their mammogram appointment scheduled that day

Milestones During Implementation

Start-up and planning.

- La Clínica was torn between hiring candidates who were on a pre-professional track, such as medical school applicants, or candidates who were on a MA track. The team thought aspiring health care providers may have quicker uptake, but would not stay in the job very long. On the other hand, there could be challenges in convincing MAs to be scribes, as the skills sets have limited overlap, and MA scribes can be asked to perform MA duties only if there is a MA staffing shortage .

- La Clínica’s medical scribes accompanied providers during each visit, documented information in the EHR during the visit, and completed any further notes after the visit to close the encounter. The provider then reviewed and signed the note.

- It was important for the physician champion to meet monthly with the scribes as well as presenting to executive leadership to bolster their ongoing support for the program.

- The team observed what they dubbed “scribe envy.” When other providers saw how scribes worked, they also wanted to have scribes.

- The team also observed “scribe guilt,” where providers in the pilot felt guilty about getting to work with a scribe. They then sometimes expressed this guilt by encouraging the scribe to work with other providers as well.

Pilot Successes

La Clínica’s medical scribe program improved in all measures but one.

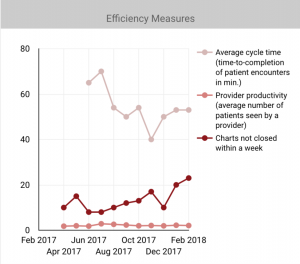

- The average cycle time for patient visits was 65 minutes in June and 70 minutes in July. After the first scribe was hired in July, the average cycle time decreased to 54 minutes in August and 50 minutes in September. The lowest was 40 minutes over the program period.

- The average number of patients seen by all providers in an hour varied, however in the best case, it increased from 1.9 to 2.5 — a 31.6 percent increase in productivity.

- Satisfaction amongst providers was high with 100 percent rating top two scores for overall satisfaction, or top box scoring, a common method for reporting and analyzing scale questions. Between 91 percent and 100 percent of patients rated top two scores for overall satisfaction.

- Despite these positive indicators, the number of charts not closed within a week increased from 10 to 23. La Clínica hypothesized that some providers may be spending a generous amount of time reviewing and appending scribe notes. There is also a chance it was spurious (e.g., due to provider leaves and vacations).

Characteristics of a Successful Scribe

- Skilled at receiving verbal information and rapidly synthesizing it into a clinically relevant format.

- Bilingual scribes are a plus when working in an environment with several different languages.

- Excellent spelling and grammar.

- Excellent listening and typing skills. A suggested minimum of more than 50 words per minute.

- Flexible, adaptable.

Advice for Organizations Considering Implementing Medical Scribes

- Hire scribes who are pre-med or pre-allied health professionals, such as aspiring pharmacy or lab technicians, nutritionists, medical record technicians, or physicians.

- Focus on productivity earlier to help make the case for sustaining the program. Consider focusing on providers who already see a high number of patients, are at risk for burnout, or could likely see more patients if a scribe were handling the documentation.

- Conversely the providers who “likes to spend a lot of time with patients” is unlikely to serve more patients while using a scribe, although they will spend less time documenting.

- Think about who else needs to be involved in rolling out your medical scribes program so that you can strengthen sustainability. This can include a “lead scribe” or your own training and quality control.

- Begin with the end in mind. What drivers and measures will support sustainability or the best business case going forward? For La Clínica, this was productivity, so that they could make a strong case to leadership to sustain the program.

- A clinical champion (CMO) and a senior administrator (COO/CIO) as co-leads .

- A lead MA , who had high levels of buy-in and motivation to implement the program, plus the three scribes, attended the host site training. She is also the rooming MA .

- A teamlet made up of the provider and a scribe. Research shows that clinicians working in stable teamlets with the same MA every day have less burnout than clinicians working with different MAs on different days.

- The first group of five MAs who went to the Shasta Community Health Center training became “superusers.” They worked with the nurses on floor to train the rest of the staff.

- When the second group of MAs went to Shasta Community Health Center for training, they were required to watch a series of videos beforehand. This help set up expectations for the training, as well as being a scribe. The videos eased some anxiety about being able to be a scribe by showing the full scope of the role.

- Building off Shasta’s training documents, the Hill Country team developed its own materials for scribes. This included some shortcuts, such as sharing providers’ templated documentation, or “quick texts,” that could be reproduced by a scribe. For instance, EPIC’s “dot notes” makes typing easy and everything provider would say is already there. An example of a simple “quick text” is “.scribe” which translates to “Portions of this note were scribed by [NAME].” Each of Hill Country’s providers has a set of “quick texts” that they’ve customized and the scribe can upload into their own profile.

- The lead MA/rooming MA and the scribes met monthly to conduct internal peer reviews, looking at notes and charts together, and share learnings.

- At times, a male scribe would need to leave the exam room at a female patient’s request. It wasn’t always possible to find a female scribe.

- Expectations were unclear about the number of visits that would be scribed. Clinicians were surprised to learn that not all of their visits would be scribed. The team also needed to clarify which portions of the visit were to be scribed.

- The team developed a medication order workflow, with provider doing the final approval, since the scribe and provider were not allowed in the medical record at the same time.

- A couple of months after launch, charts were coded faster so the cycle time for billing decreased, providers were leaving work faster and needed less charting catch up time over the weekend, and fewer calls from patients asking about faster referrals and refills.

- The pilot team scribes helped to train the new scribes in the next site for implementation. The pilot clinicians were also available as a resource to the clinicians new to scribes.

- To hire scribes in a more remote area, Hill Country advertised for MA positions, got senior MA applicants, and then asked if they would be willing to also scribe.

- Having a separate rooming MA for every two providers that had scribing MAs made the workload more balanced. The scribing MA can’t also room the patients, take care of their immunizations, wound care, EKGs or other ancillary tasks. They can’t be in two places at once. You must separate these two roles in order for either job to be done successfully.

Building a Business Case for Spread

Hill Country’s medical scribe program produced gains in multiple areas.

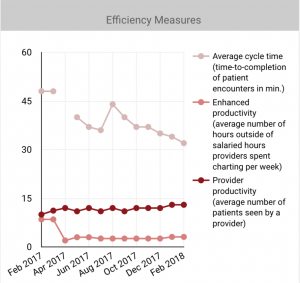

- The average cycle time for patient visits decreased from 48 minutes to 32 minutes — a 33 percent decrease in average cycle time .

- The average number of hours providers spent charting outside of their normal salaried hours decreased from 8.5 hours to 3.1 hours — a 63.5 percent decrease in hours spent charting outside of salaried hours .

- These efficiencies happened while productivity increased from an average of 10 patients seen by a provider in a day to 13 patients seen by a provider in a day — a 30 percent increase in productivity .

Other benefits include:

- Team members going home on time.

- No overtime.

- More timely submission of claims

- Provider satisfaction at 100 percent for the entire program period.

The co-leads are confident this contributes to greater provider retention. They calculated that by adding one additional patient in the morning and one in the afternoon, the additional revenue would be able to pay for the extra rooming MA cost.

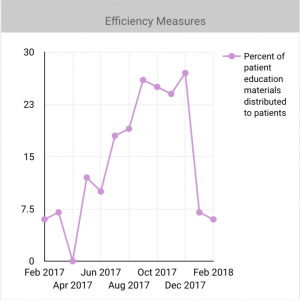

Additional goals included increasing the distribution of educational materials, depression screening, and follow-up plans for patients who screened positive for depression.

- Someone who can type quickly and also multitask. This is especially true for the scribes who are also MAs, as they must still answer questions from the front office, nurses, LVNs, and behavioral health staff.

- Someone who understands the medical process and how the chart works because providers will often simply talk with patients about their condition. The provider may not tell the scribe to type medical advice into the assessment and plan section of the chart.

- Someone who is flexible, but also has time management skills and the assertiveness to be able to tell the provider diplomatically that they need to wrap up the visit or save a particular conversation for another day.

- Take the time to offer one-on-one training to scribes. And set aside time to practice the skills.

- Your scribes will benefit from training guides and materials, both online and offline.

- Develop a train-the-trainer program so you don’t have to pull scribes off the floor each time you implement additional scribes.

- Share providers’ templated documentation, or “quick texts”, that could be reproduced by a scribe.

- The MA can’t be both a MA and a scribe due to time limitations and workloads of each role. You must separate these two roles in order for either job to be done successfully.

- Be clear up front and communicate expectations with providers about the number of their visits that will be scribed and what portion of those visits will be scribed.

Related Resources

Innovation Spotlight: Medical Scribes in the Safety Net

Southeast Health Center in San Francisco looks at the best way to train and manage medical scribes as part of their team.

Medical Scribes: Start-Up Basics 2017

Michaela Boucher and Charles Kitzman of Shasta Community Health Center give an overview of what it takes to implement medical scribes in an organization, the barriers and benefits, and lessons learned…

Medical Scribes: Duties and Workflow 2017

Michaela Boucher from Shasta Community Health Center talks about medical scribe duties and workflow in this webinar.

Medical Scribes: HR and Scribes 2017

Michaela Boucher and Charles Kitzman from Shasta Community Health Center share their experiences and knowledge around hiring scribes, the interviewing process, payment, and career advancement.

Case Study: Medical Scribes Improve Provider Satisfaction in Rural California

To improve retention, recruitment, and provider satisfaction, Hill Country Health and Wellness Center piloted medical scribes.

Table of Contents

Book Translation Case Study: F#ck Content Marketing

How do foreign rights deals happen, what are foreign rights agents looking for, what should you expect from a foreign rights deal, how to translate your book (& reach international markets).

If you want to translate your book into a foreign language, let me be the first to tell you:

Translating a book is not as simple as changing Language A into Language B.

Most Authors don’t realize this. In fact, I often hear Authors asking about what freelancers or services to use when translating their self-published book .

To be fair, I can understand why they ask. It’s natural to think that simply making your book available to new readers would automatically lead to new sales.

But (most of the time) hiring a freelance translator or service won’t get you the results you want.

In this post, I’ll explain the right way to translate your book.

But before I dive into that, here’s a key point you need to know:

Translating a book only leads to sales if you can actually reach foreign readers to let them know about it.

Unfortunately, most Authors can’t.

Think about it from a reader’s perspective. There are millions of books on Amazon. If a Spanish Author translated their book into English tomorrow, what are the odds that you’d even hear about it, let alone buy it?

Without local advertising and promotion , translated books don’t make money in foreign markets. But it can still be worth doing, as long as you know why you’re doing it, and as long as you’re doing it the right way.

There are 3 main reasons why Authors want to translate their books:

- To increase book sales

- To raise their visibility in a foreign market

- For the prestige of being able to say their book has been translated into foreign languages

If you fall into either of the first 2 categories (and maybe even the third), hiring a professional translator and uploading your book into a foreign market on Amazon is not the way to do it.

So, what’s the right way?

Sell your translation rights to a foreign publisher who will translate and release the book in their own local market.

I’ll be honest: that’s not easy, and, for most books, it still won’t lead to a lot of new sales. But it’s the best way to raise your visibility in a foreign market, especially if you care about how your book is received.

To show you why—and how—the foreign rights process really works, I’ll share a case study of one of our own Scribe books that was translated into Vietnamese.

Here’s the U.S. cover of F#ck Content Marketing , by Randy Frisch . Through Scribe’s partnership with a foreign rights agency, we helped Randy sell his foreign rights to a publisher in the Vietnamese market.

But before I get into that process, I want to point out a few key things about this cover.

First of all, notice how much “punch” the prominent F#ck has with a U.S. audience.

That same F#ck accounts for half the title space at the top of the back cover . With just a single-word image, the Author conveys a bold message about content marketing.

That repeated title is followed by several powerful blurbs that prove the Author’s credibility.

Now, look at this:

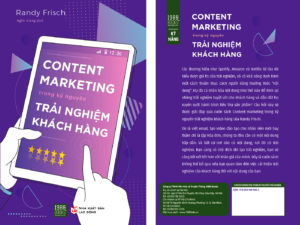

This is the Vietnamese cover, created by the local publishing company that bought the foreign publishing rights.

See what’s missing? Right. That F#ck , so critical to the U.S. cover, isn’t anywhere to be found.

Why? The answer boils down to an essential truth about foreign book rights:

Book translation is not just about translating your book. It’s about releasing it to a foreign market.

When the local publisher released the book in Vietnam, they changed the cover because they know their own market. They know what will or won’t sell—and they know what local readers will find offensive.

The word still made it into the interior translation of the book, but it wasn’t right for the cover . Not in Vietnam.

They also changed the cover’s color scheme, and they chose not to include the blurbs, presumably because the people quoted on the back of the U.S. cover wouldn’t be known to the local Vietnamese audience.

All this is to say: if you want your book to be well received in a foreign market, you need to do more than just translate it. You need to release it in that market, with all the local market knowledge that goes into publishing a book.

So how do you do that? By making a deal with a foreign publishing company that knows the language, the market, and the culture as well as the local rules and regulations.

Here’s the hard truth: It’s virtually impossible to sell translation rights to a foreign publisher on your own.

For one thing, English isn’t their first language, so communication is already difficult. But even if you speak the language well enough to get by, you still need a way to get your foot in the door.

If you want to make a foreign rights deal, you really want a foreign rights agent.

Foreign rights agents specialize in foreign rights deals. They spend a lot of time traveling around the world, learning the ins and outs of foreign publishing markets, and building relationships with foreign publishers.

As a result, most foreign rights deals happen at large, international book fairs, where publishers and agents gather together from around the globe—or, at least, they did.

I’m writing this post in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and no one knows for sure at this particular moment when those book fairs will resume, or what they’ll look like when they do.

But that only makes foreign rights agents more critical than ever. They’ve already forged relationships with foreign rights editors, so they can make those deals happen in an online environment.

Scribe, for example, partners with DropCap, a tech-enabled foreign rights agency with an online platform to complement their broad base of relationships all around the world.

In the modern world, there are plenty of ways to communicate remotely. It’s not the face-to-face meeting that’s key. It’s the underlying relationship.

Like all literary agents, foreign rights agents are looking for books that will sell—because those are the books foreign publishers will want to release in foreign markets.

Obviously, this varies by market. Business book translations tend to do well in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. In the Netherlands, most readers prefer to buy books in English over their own native Dutch.

This is the kind of local market knowledge that makes foreign rights agents so important.

At a higher level, foreign rights agents are always trying to create long-term pipelines for new books that will sell well in local, translated versions.

That’s why they prefer to work with two categories of clients:

- Professional writers who write and sell a lot of books

- Publishing companies that publish a lot of books

Without a publisher or a publishing partner, the process of finding a foreign rights agent for a single book is even harder than finding a domestic rights agent.

But if you happen to have a way to get your book in front of one, here’s what they’re looking for:

- Substantial sales and Amazon reviews in the first week of the book’s domestic release

- Any connections you have to the specific foreign market

- Whether you speak the language to help market the book with interviews, etc.

- Proven media success is the English market

- Any other way you can prove you have an audience

If you meet these criteria and a foreign rights agent is interested, they’ll read your book and see whether they think the content is a good fit for a particular market.

If you’re fortunate enough to attract the attention of a foreign rights agent and a foreign rights publisher, here’s what to expect.

1. At least 18 months to translate & publish your book

Remember, the publisher isn’t just translating your book into their native language. They’re editing , proofreading , creating a new cover, and doing all the things publishers do for any new release.

2. Negotiate over the advance, not the royalties

Foreign royalties are extremely hard to monitor, so don’t waste any leverage negotiating for them. Instead, focus on the advance, and don’t expect to see any money beyond that.

3. The advance probably won’t be very big

Most Authors should expect to see an advance that ranges between about $800 and $5,000.

Why so low? Because the local publisher is investing all the money and doing all the work to translate and distribute the book.

Fortunately, there are a lot of countries out there, so the best path for an author is to get a small advance from a number of different countries.

4. Enjoy the prestige

Foreign rights aren’t something you go after if you want to get a regular check in the mail. What little money you’ll get from the advance is a nice bonus, not a living.

But here’s the thing: most Authors who make money on their nonfiction book don’t make that money through book sales.

Instead, they make money by raising their visibility or by enhancing their credibility, which is the biggest thing foreign publication does for most Authors.

If that’s the only thing you want, and if you don’t care at all how your book is perceived in foreign markets, you can always hire a freelancer for as many new languages and new translations as you want, self-publishing each one to foreign markets on Amazon.

But this will cost you a lot of money, and you won’t have any way of knowing if the translation is any good or how your book will be received.

So, if the translation matters, don’t try to go it alone. You’re better off not translating your book at all than wasting your money and hurting your own reputation. There are much better ways to reach new readers.

If you’re looking for ideas, check out our guide for ways to promote a book .

The Scribe Crew

Read this next.

How To Become A Published Nonfiction Author

The Best Self-Publishing Companies for Nonfiction

How to Write Your Book with A Hybrid Publisher

- Forum Listing

- Marketplace

- Advanced Search

- Amazon Devices

- Kindle Accessories

Scribe Cases

- Add to quote

I ordered my Scribe as a bundle that included the official Amazon case. It's a pretty case, but I am not sure how practical it's going to be in the long run. I was looking for other case options at Amazon and there are surprisingly few reviews for any of them. I'd like to know if you purchased a non-Amazon case for your Scribe. Which one was it? Do you like it? Why or why not? Thanks!

I also got an Amazon case but was browsing the other day. There aren't too many options yet. This was one that I liked well enough to put on a 'shopping' list to think about: MoKo Scribe cover But I'm not yet ready to drop another $35 .... edited to add: just went browsing some more and found this one: CoBak Case for Scribe and this other slightly more expensive by the same maker: CoBak Case for Scribe with hand strap, easel feature

I bought a Fintie book style case but I don't know if they're available in the US. I almost always buy Fintie cases and have been happy with them, especially as they're usually half the price of the Amazon covers. I do like this one though it's weird having cut outs for the charging port on the spine of the 'book' - but I've never really been keen on the notebook style ones that fold open at the top. I'm sticking with this one for a while though I might treat myself to a different one later when there are more options - and reviews.

I’m also looking for a good Scribe case. I bought the Fintie one from Amazon UK (the “library” pattern one) and it arrived today. But I’m not sure… Like Linda mentioned above, it’s really odd having the cut out for the charging cable on the spine. The hole feels “rough”/catching and I don’t like it there. But to be honest I don’t like the charging port on the Scribe being in the middle of the longer side anyway. Would have so much preferred it on the top or bottom, the same goes for the power button. Apart from this I find the case really heavy! I have not weighed it, but guesstimate it to make the Kindle Scribe slightly over twice it‘s weight with the case on it. And it’s not a light device to start with. So this has quite put me off the case... I nearly pre-ordered one of the Amazon cases. But having seen so, so many negative reviews for them now (at least on Amazon UK) I‘m glad I did not pre-order one. Unless someone on here can persuade me otherwise? I’ve only had the Finite case for 2 hours but I’m not sure I will keep it… That leaves me looking for lighter case, non Amazon one, which preferable has the spine along the top to avoid weird side holes on the case. Only question is if one of these exists yet please?

I have not seen any other flip style cases here in the US yet. Any book style case will have a cutout for the charger and power button on that left edge.

I agree with Anso - though in general do I like the Fintie case it is heavier than I expected it to be and it is the feel of the side cut outs as much as the look that's off putting. I'm not paying Amazon case prices though, whatever style they bring out so I'll give it a while for all the other 3rd party makers to get something out and then see if I can find something I like better at a reasonable price.

I ordered the Finite case and also find it heavy. I ordered the Amazon case but had my doubts because of the ratings. I actually like it because it is lighter and I like using as a stand on a desk surface.

Amazon.com: WALNEW Stand Case for Kindle Scribe 10.2 Inch (2022 Released) – Two Hand Straps Premium PU Leather Cover with Auto Sleep/Wake and Pen Holder for Amazon Kindle Scribe Ereader (Hot Pink) : Electronics

Amazon.com: Fintie Slimshell Case for Kindle Scribe 10.2 Inch (2022 Released) - Premium PU Leather Lightweight Book Folio Cover Auto Sleep/Wake with Pen Holder, Library : Electronics

Amazon.com: Fintie Trifold Case for Kindle Scribe (2022 Released) 10.2 Inch - Ultra Lightweight Slim Shell Foldable Stand Cover with Auto Sleep/Wake, Blooming Hibiscus : Electronics

I jumped on the Scribe sale Amazon was having recently, and ordered the bundle with the black fabric case. I was certain I was going to hate the case, given the number of negative reviews, but after using it for a day, I'm actually rather fond of it. First of all, it's extremely lightweight. The fabric texture looks great and gives you a very solid hold on the device when carrying it. The texture makes holding it while reading a bit easier as well. While I wasn't crazy about the idea of a top fold case, for this device it works great -- it properly orients the device for writing (pops up the top a few degrees from flat). The magnets hold the device adequately for purpose. They're nearly as strong as the magnets holding my iPad Pro 12 in its tri-fold case, and as long as I don't try to carry the case by the lid, the Scribe stays put. If I jiggle the open case aggressively, the Scribe will fall out. If I pull on the back of the case, the Scribe will fall out. However if I insert my left index finger into the hinge pocket created when the case is open, while also pinching the Scribe with my thumb (a very natural movement FYI), and then sliding my other right index finger down the gap created on the other side, I can flip the lid with no concerns whatsoever. Exactly how I would flip the cover of a paper reporters notebook. Can you close the case one handed? Probably not, which is likely where people are having issues with the Scribe falling out -- it's just not rigid enough to withstand the torque of the magnetic attachment of the lid and back when you begin to pull them apart. I'm not crazy about the pen loop -- Amazon should have added additional pen magnets along the top edge of the Scribe so that the pen could be held captive by the "hinge" of the case when it's closed, eliminating the need for the loop entirely.

Amazon.com: WALNEW Flip Case for 10.2-inch Kindle Scribe 2022 Released, Two Hand Straps and Vertical Multi-Viewing Stand Cover with Auto Wake/Sleep for 10.2” Amazon Kindle Scribe E-Reader (Navy Blue) : Electronics

Amazon.com: WALNEW Sleeve Case for 10.2-inch Kindle Scribe (2022 Released), Protective Pouch Bag Case Cover with Pen Holder for 10.2” Amazon Kindle Scribe E-Reader (Gray) : Electronics

- ?

- 115.2K members

Top Contributors this Month

Get the Reddit app

Kindle scribe is a game changer paper tablet for people that wanna go paperless but still want to have the feeling of pen n paper!

Scribe Question: Good enough to justify as primarily a reader?

I have plenty of tablets, but I like taking notes by hand, with pens and paper. I’m not looking for a notebook or a note taker.

I‘ve used kindles for a long time, I mostly use the iPhone app and the current Paperwhite. I like both reading experiences, but given my history and style of reading I am beginning to realize that when I want to read with a small device it is almost always my phone. I like my phone as a reading device, so that doesn’t bother me, just background.

I do, however, love e-ink. While I’ve used kindles for a while, one of my all time favorites was the Kindle DX, which I ended up selling because it was competing with my iPad for bag space on trips. I get the feeling that the Scribe would compete with the iPad for bag space too, but I’m more OK with that these days as long as it offers a really stellar reading experience.

99% of my reading on the Kindle is on airplanes, where the battery life beats a phone by a long shot. Personal opinion: how do you think the Scribe would do in that situation?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

AO1 or AO3. Research studies can either be knowledge or evaluation: ... and (2) the inner scribe (which records the arrangement of objects in the visual field and rehearses and transfers information in the visual cache to the central executive). ... The KF Case Study supports the Working Memory Model. KF suffered brain damage from a motorcycle ...

THE CASE STUDY OF THE SCRIBE, kavet... 𝕱𝖆𝖓𝖋𝖎𝖈𝖙𝖎𝖔𝖓 :: 𝖑𝖔𝖓𝖌. : ̗̀ Dove Al Haitham realizza che un'esistenza pacifica non necessariamente dev'essere un'esistenza solitaria. ˚₊· ͟͟͞͞ Questa è solo una traduzione: tutti i crediti vanno a @/Jazer su ao3, che mi ha gentilmente permesso di tradurre ...

(2) Point: Support for the working memory model comes from the case study of KF. Evidence: For example, KF suffered a motorcycle accident and was left with considerable damage to his memory. His short-term forgetting of auditory information was greater than for visual information, suggesting that his memory damage was restricted to the ...

Given the novel technology used in ambient AI scribes, an objective of the implementation was to maintain the quality/accuracy of clinical documentation while also identifying, minimizing, or mitigating potential safety risks introduced by the use of the AI scribe technology. 4, 10 Prior studies of human medical scribes provided a framework for ...

Describe and evaluate the working memory model- Fahmida. AO1 - The working memory model (C, P, V.S, E) AO3 - Dual-task studies 'moving light and letter F' AO3 - Evidence from brain-damaged patients (KF's STM) AO3 - Weakness of case studies of brain-damaged patients AO3 - Central executive is too vague (EVR had poor decision making)

An Archive of Our Own, a project of the Organization for Transformative Works Main Content; Archive of Our Own beta. Log In. User name or email: Password: ... scribe's fanfic library > Fandoms You can search this page by pressing ctrl F / cmd F and typing in what you are looking for.